Capturing Lost Time: A Conversation with Raghu Rai

Capturing Lost Time: A Conversation with Raghu Rai

Capturing Lost Time: A Conversation with Raghu Rai

To engage with Raghu Rai is to encounter photography not merely as a visual practice but as an ethical and philosophical position. Over the course of more than five decades, Rai has articulated a consistent understanding of photography as a mode of witnessing—one grounded in intuition, responsibility, and sustained attention to lived reality.

On the occasion of winning a major arts prize, the iconic photographer was briefly in conversation with the editor of the DAG Journal, where he drew together his reflections on vision, truth, and the role of the photographer, while situating his ideas within broader debates on documentary practice.

Raghu Rai, At Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, 2002, 20.0 x 30.0 in. Collection: DAG

Rai has repeatedly rejected the idea of photography as a purely technical or aesthetic pursuit. Instead, he frames it as a way of being present in the world. His often-quoted assertion that photography is his ‘religion’ is not rhetorical excess but an epistemological claim: photography, for Rai, is a discipline of awareness, as he still maintains. The photographer must cultivate receptivity rather than control, intuition rather than calculation. In this sense, Rai’s practice aligns with phenomenological approaches to visual perception, privileging embodied experience over premeditated design.

Central to Rai’s philosophy is the rejection of excessive cognition at the moment of image-making. He says that ‘thinking interferes’ with seeing, suggesting that intellectualisation disrupts the immediacy required for meaningful photographic engagement. This position does not imply an absence of thought, but rather a temporal distinction: reflection occurs before and after the photograph, not during its making. The act itself demands responsiveness. Here, Rai implicitly critiques formulaic documentary practices that prioritise predetermined narratives over emergent realities.

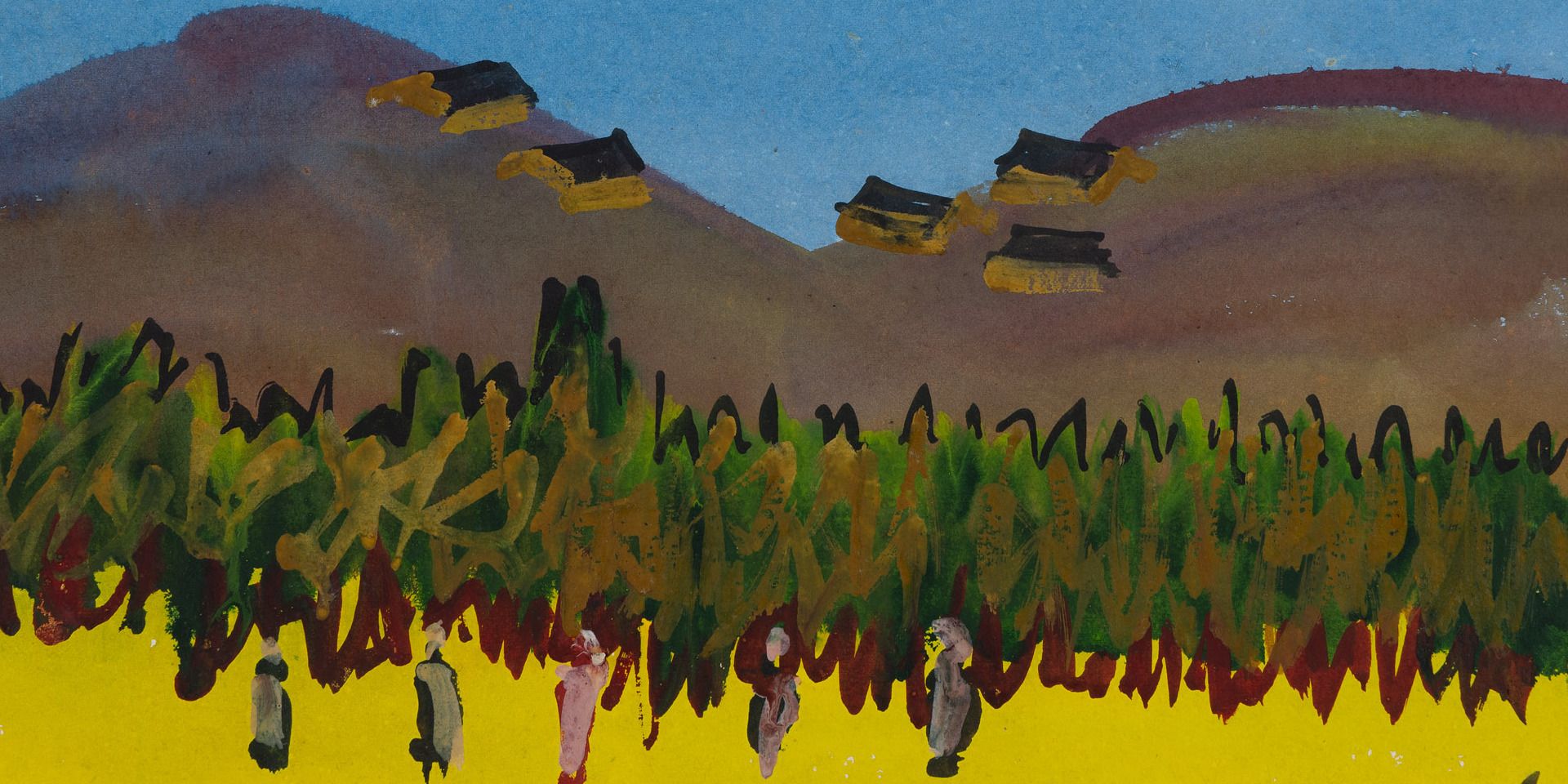

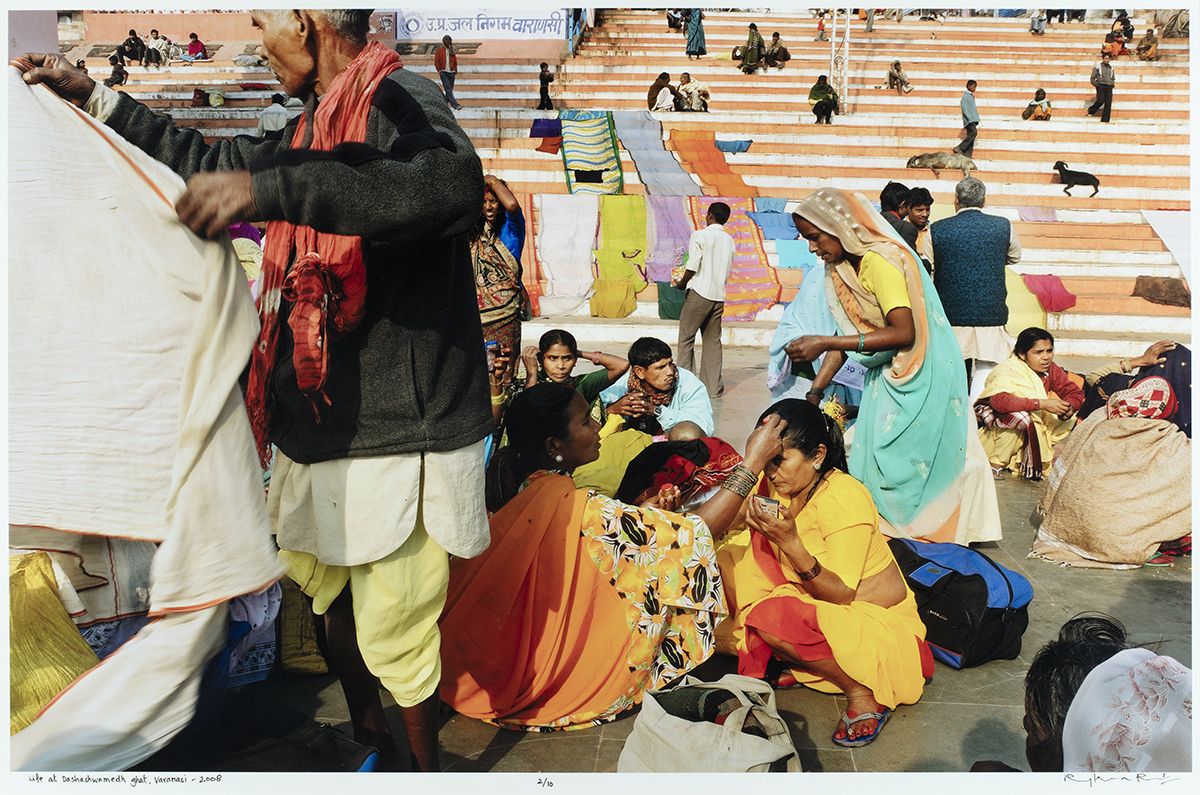

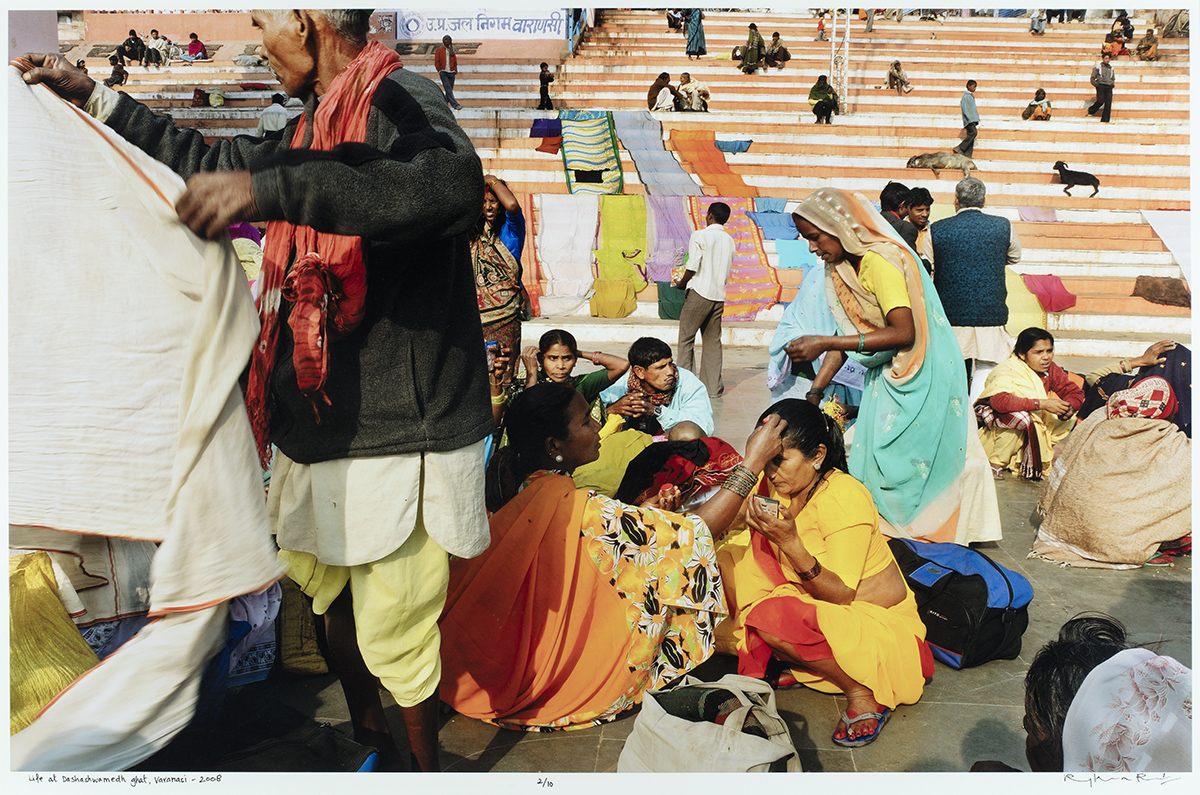

Raghu Rai, Life at Dashashwamedh Ghat, Varanasi, 2008, Inkjet print on archival paper 20.0 x 30.0 in. Collection: DAG

This commitment to responsiveness becomes particularly significant in contexts of crisis and trauma. Rai’s documentation of the Bhopal gas disaster exemplifies his approach to ethical witnessing. He has maintained that sentimentality is a liability in such circumstances; emotional identification, if unchecked, risks obscuring clarity. Instead, Rai advocates for a form of disciplined empathy—one that acknowledges suffering without aestheticising it. The photographer’s role, in his view, is not to console but to testify. This position places Rai within a lineage of documentary practitioners who emphasise accountability over affect.

At the same time, Rai resists the notion that documentary photography must be austere or detached. His images often display compositional grace, careful attention to spatial relationships, and a sensitivity to light that borders on the lyrical. Rather than seeing this as a contradiction, Rai insists that aesthetic awareness enhances, rather than diminishes, documentary truth. Form and content are mutually reinforcing; visual coherence allows the photograph to sustain attention and invite contemplation.

Rai’s engagement with spiritual figures such as Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama further illuminates his understanding of photographic ethics. He emphasises restraint, invisibility, and respect for the subject’s interiority. Photography, in such contexts, becomes a negotiation between presence and withdrawal. The camera must not dominate the encounter. This approach challenges extractive models of image-making and suggests an alternative framework grounded in relational ethics.

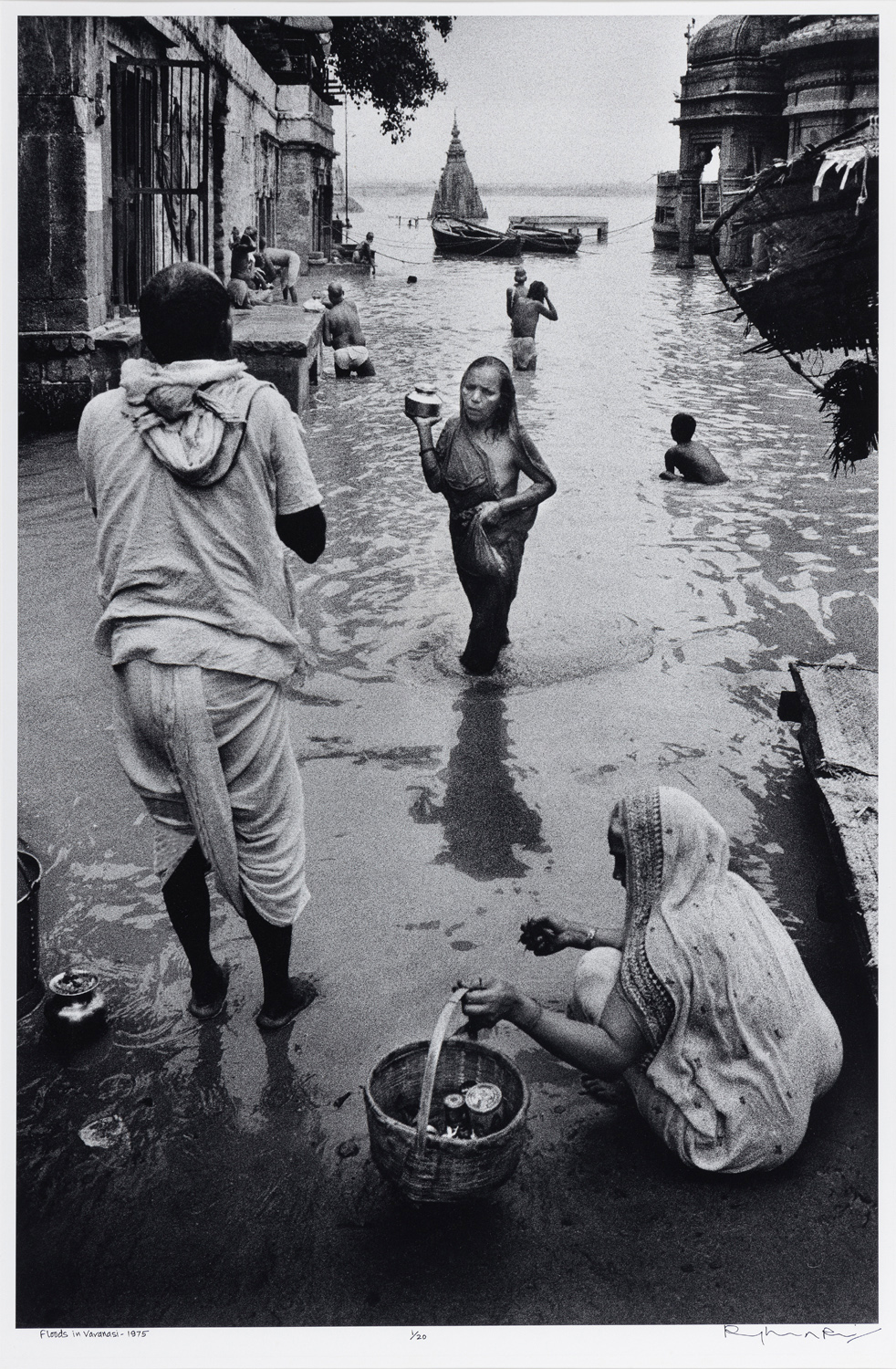

Raghu Rai, Floods in Varanasi, 1975, Inkjet print on archival paper , 29.7 x 19.7 in. Collection: DAG

India occupies a central position in Rai’s work, though he consistently resists claims of representational totality. Rather than attempting to photograph ‘India’, or its sacred placed like Varansai, as abstract entities, Rai focuses on fragments, moments, and lived textures. He has described India as inherently complex and layered, requiring patience rather than spectacle. This insistence on partiality aligns with contemporary critiques of nationalist and touristic visual narratives, positioning Rai’s work as an ongoing inquiry rather than a definitive statement.

In reflecting on technological change, Rai distinguishes between accessibility and depth. While digital tools and mobile cameras have democratised image production, he argues that they have not necessarily cultivated visual literacy. Technical proficiency, in his assessment, is insufficient without awareness of space, context, and intention. The proliferation of images risks flattening meaning unless accompanied by disciplined seeing. This critique echoes broader academic concerns about visual saturation and the erosion of contemplative engagement in contemporary media culture.

Rai’s distinction between photography that merely informs and photography that endures is particularly instructive. For him, a lasting image is one that continues to pose questions rather than resolve them. Such photographs resist closure and invite repeated viewing. This understanding situates photography as a dialogic medium, capable of sustaining interpretive openness over time. His own projects on nature—trees, clouds, rain—emerged not as conceptual assignments but as attentional discoveries, reinforcing his belief that significance often reveals itself indirectly.

Institutional recognition, including his association with Magnum Photos, occupies a marginal place in Rai’s self-understanding. He acknowledges the value of exposure to other photographic traditions but insists that comparison dissolves at the moment of practice. Each photograph, he suggests, exists in a singular temporal and ethical space. This emphasis on the irreducibility of the moment underscores his resistance to canonisation and stylistic branding.

Raghu Rai, A Faithful in Varanasi, 2008, Inkjet print on archival paper , 20.0 x 30.0 in. Collection: DAG

Despite his extensive body of work, Rai consistently frames his practice as unfinished. He has described himself as increasingly ‘hungry’—a metaphor that signals not dissatisfaction but sustained curiosity. Photography, rather than providing answers, has intensified his engagement with the world. This orientation toward perpetual inquiry may be his most enduring contribution.

Ultimately, Rai defines his dharma as the pursuit of truth—not as an abstract ideal, but as a situated, contingent practice. Truth, for him, is not manufactured or imposed; it is encountered through attentiveness, humility, and ethical commitment. In articulating photography as a form of responsibility, Rai positions the photographer not as an authorial voice but as a conduit through which reality briefly becomes visible.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

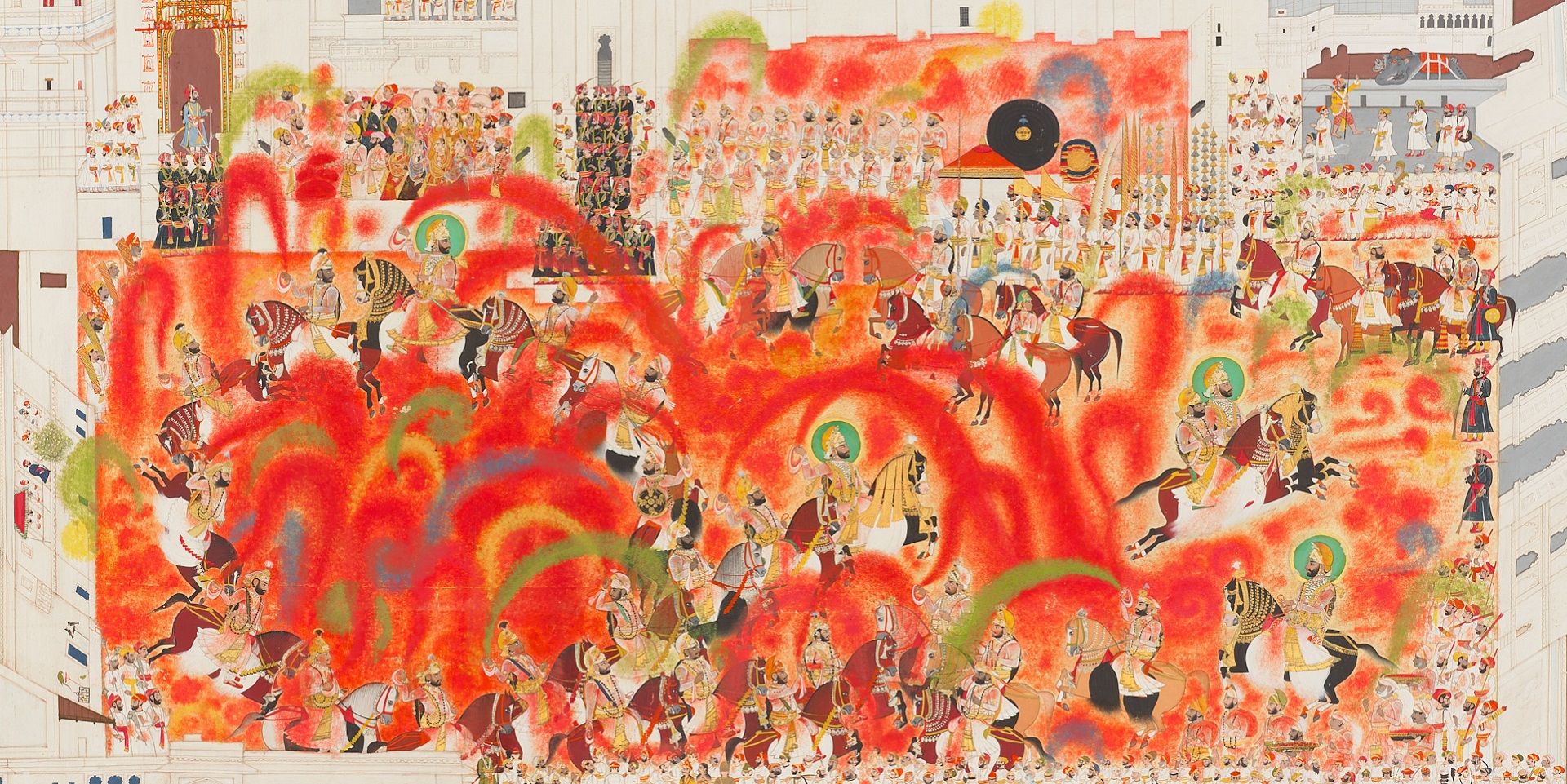

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

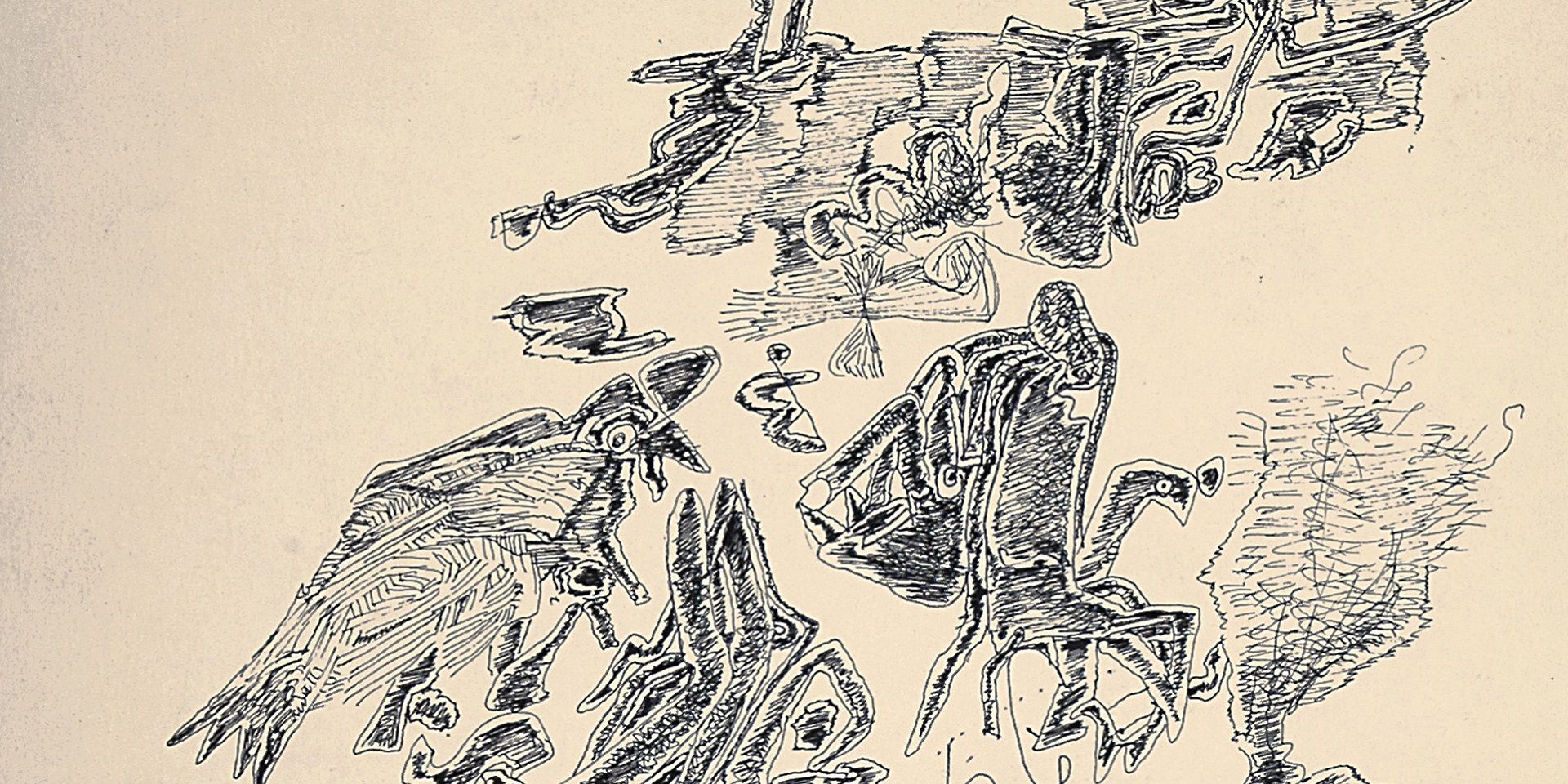

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

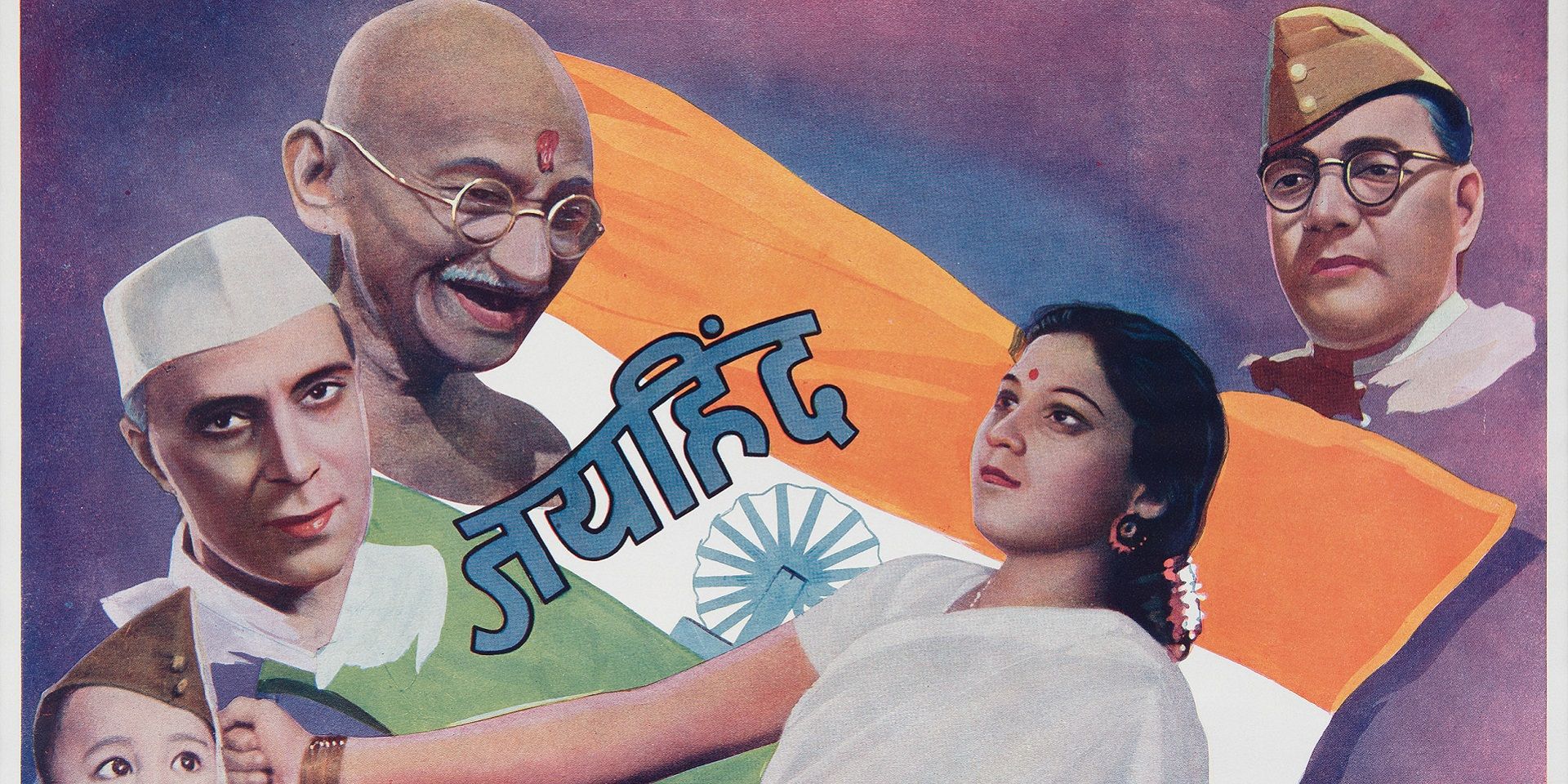

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

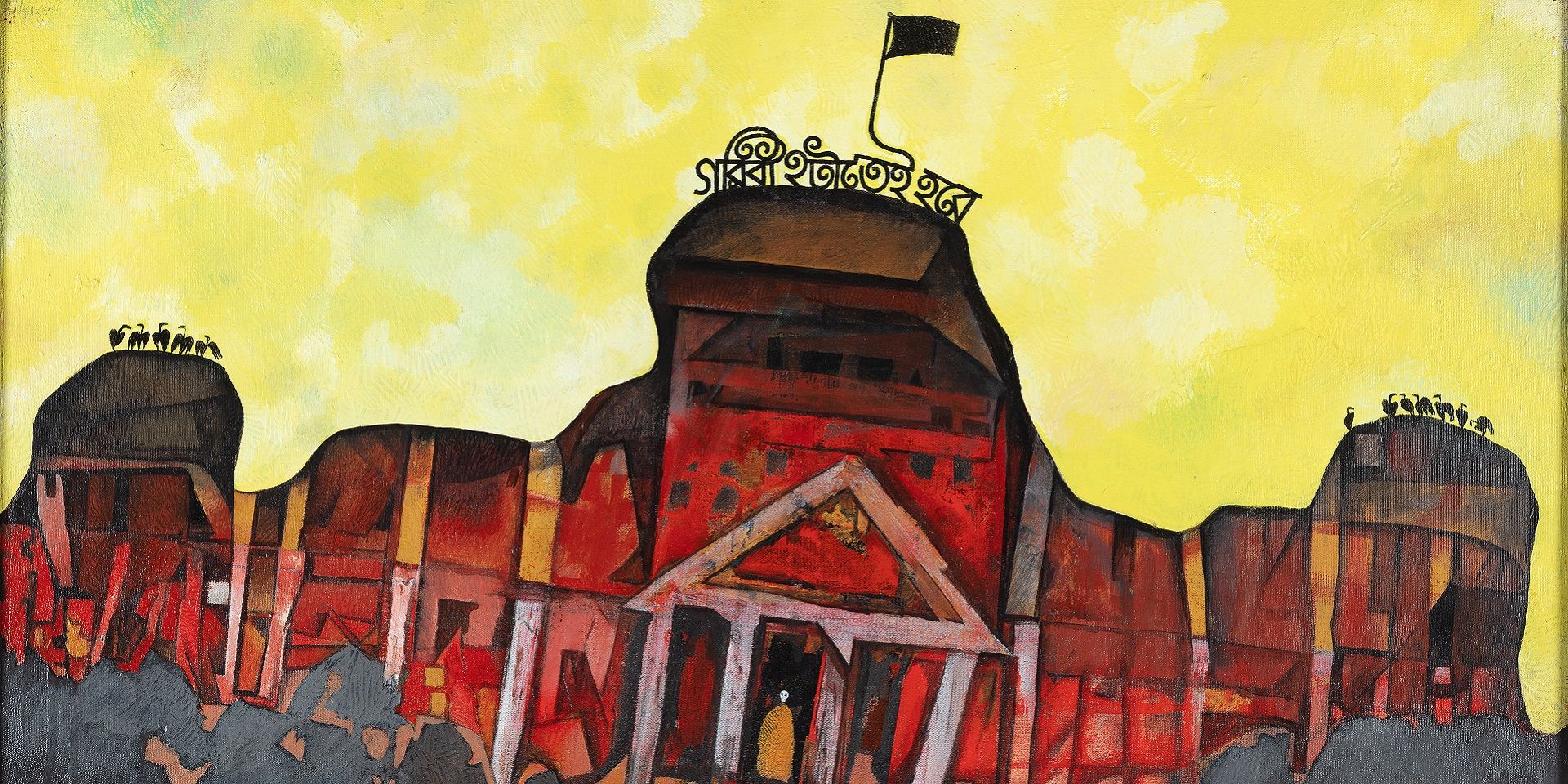

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025