CAAM Diaries: Anwesha Sengupta on the Politics of Waiting

CAAM Diaries: Anwesha Sengupta on the Politics of Waiting

CAAM Diaries: Anwesha Sengupta on the Politics of Waiting

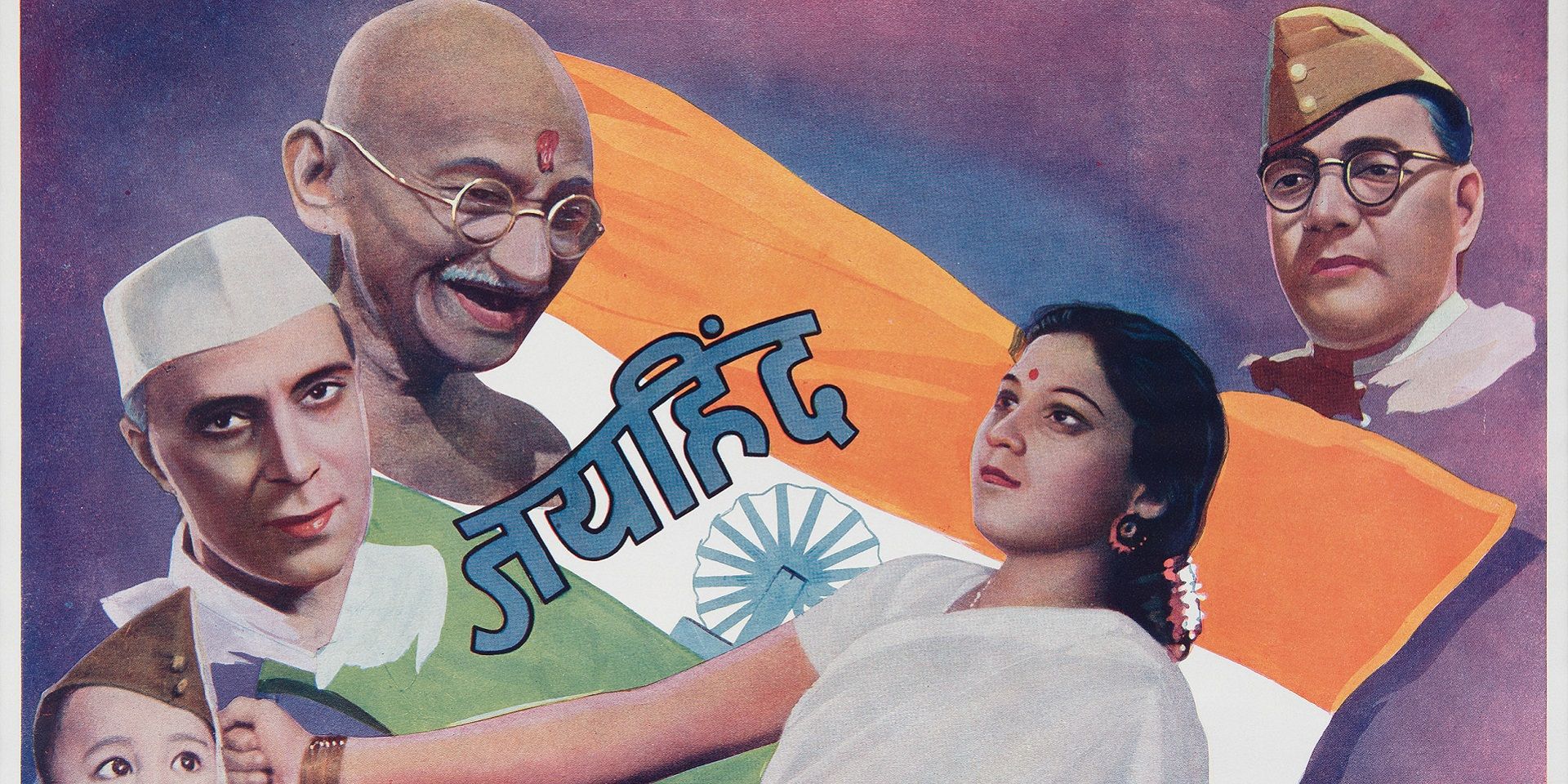

In India, state-imposed politics of waiting operates as a mechanism of bureaucratic control that disproportionately burdens poorer citizens and refugees. Ethnographic research shows that low-income groups, including informal workers, endure prolonged bureaucratic delays for essential documents and welfare entitlements, reinforcing hierarchical citizenship and exclusionary state power.

Waiting becomes a ‘technology of governance,’ where temporal delay itself shapes access to rights and recognition, and produces differentiated forms of citizenhood. For refugees and undocumented migrants, the absence of legal recognition in India compounds precarious waiting, leaving them in limbo without clear status, work opportunities or social protection. Academics argue that this politics of waiting is not merely administrative delay but reflects structural power: it delays justice, diminishes agency, and reinforces social inequalities, making time itself a site of exclusion and struggle. Historicising this insidious exercise in denial of rights, historian Anwesha Sengupta reflects on the impact of this bureaucratic machinery of negligence on refugees who had migrated to Bengal from the 1940s onwards. This narrative was presented, discussed and explored at the iconic venue of the Sealdah station’s waiting rooms during the fifth edition of 'The City as a Museum, Kolkata' in 2025.

Negotiating Agency and Victimhood: Partition Refugees at Sealdah Station

February 5 of 1958 was an unusually busy day at Sealdah Station. Several hundred refugees from East Pakistan who were then squatting at the station, had high profile visitors from the mid-morning. Leaders of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP), including a member of the assembly, came to meet them. So did Jogendranath Mandal, the most prominent face of Dalit politics in twentieth century Bengal. In the evening came the representatives of the United Central Refugee Council (U. C. R. C.) – the Communist Party of India dominated refugee organisation. All of them had the same intention – to mobilise the platform refugees for one rally or the other. Mandal used caste as the rallying cry. Though most of the refugees were Dalits, their response to Mandal was lukewarm. Only a handful of them joined the rally he was recruiting for. On the other hand, U. C. R. C. leaders emphasized on the need for the Sealdah squatters to identify themselves as refugees, without highlighting their caste or other identities. But the specific grievances of the Sealdah refugees had not been highlighted enough by the U. C. R. C. on previous occasions, the squatters complained.

|

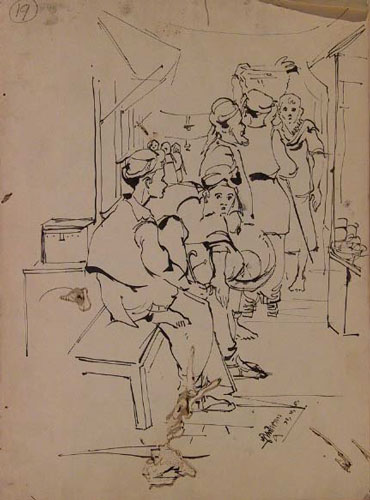

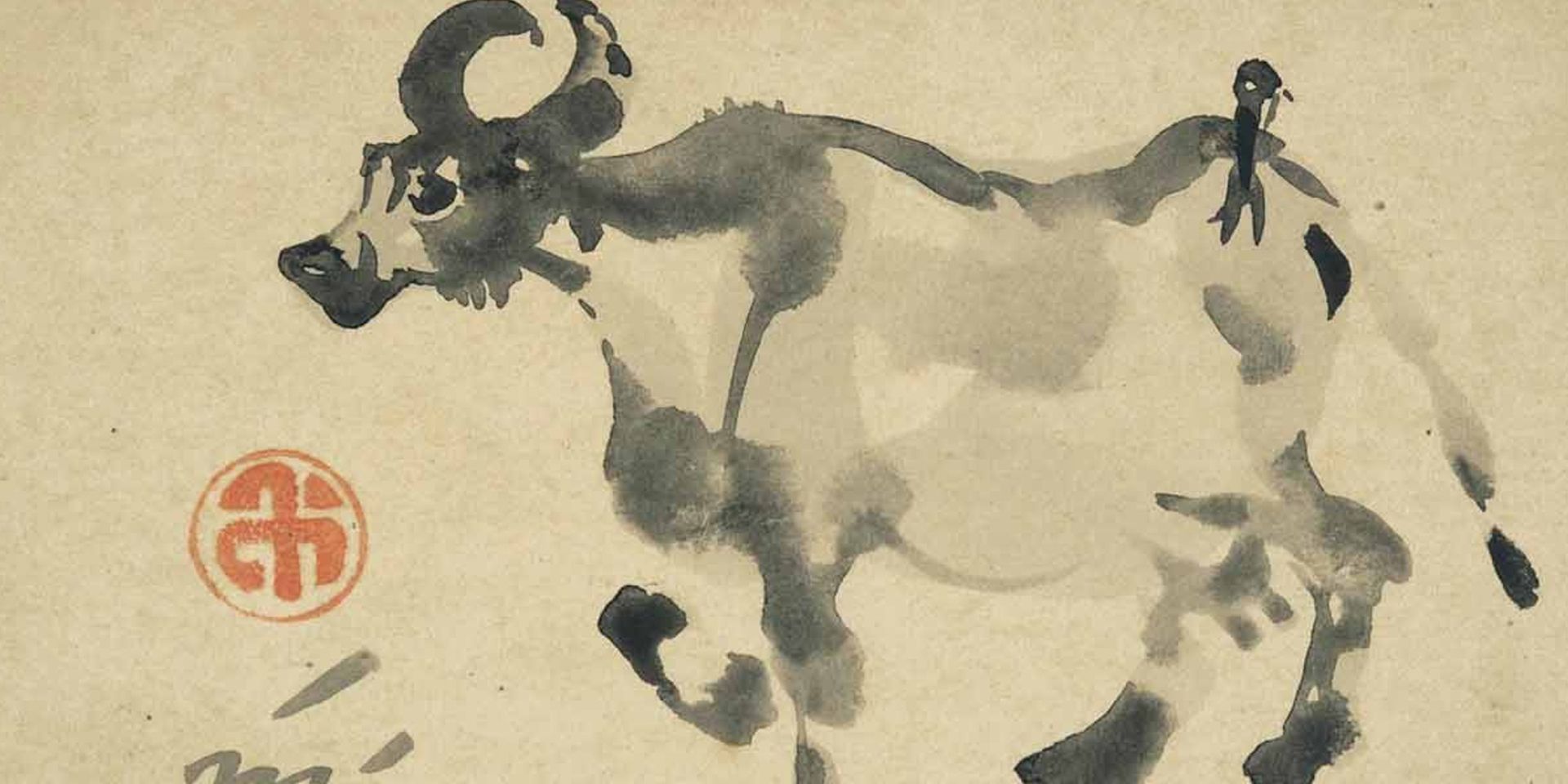

Satish Sinha, A Refugee Camp in South Calcutta, 1946, Ink on paper laid on box board, 10.5 x 15.0 in. Collection: DAG |

The refugees at the station were restless and angry. They had been waiting at Sealdah for rehabilitation for quite some time. And staying at a crowded, busy, public space like Sealdah was an extremely harsh experience. The week before had witnessed scuffles between the platform-refugees and the police - resulting into serious injuries on both sides, as the latter were trying to rescue the relief officer, gheraoed by some four-hundred refugees demanding rehabilitation. In this volatile atmosphere, these refugees seemed to trust none. When they were approached by the political leaders and the organisations critical of the government’s rehabilitation policies for protest marches, they expressed their scepticism.

|

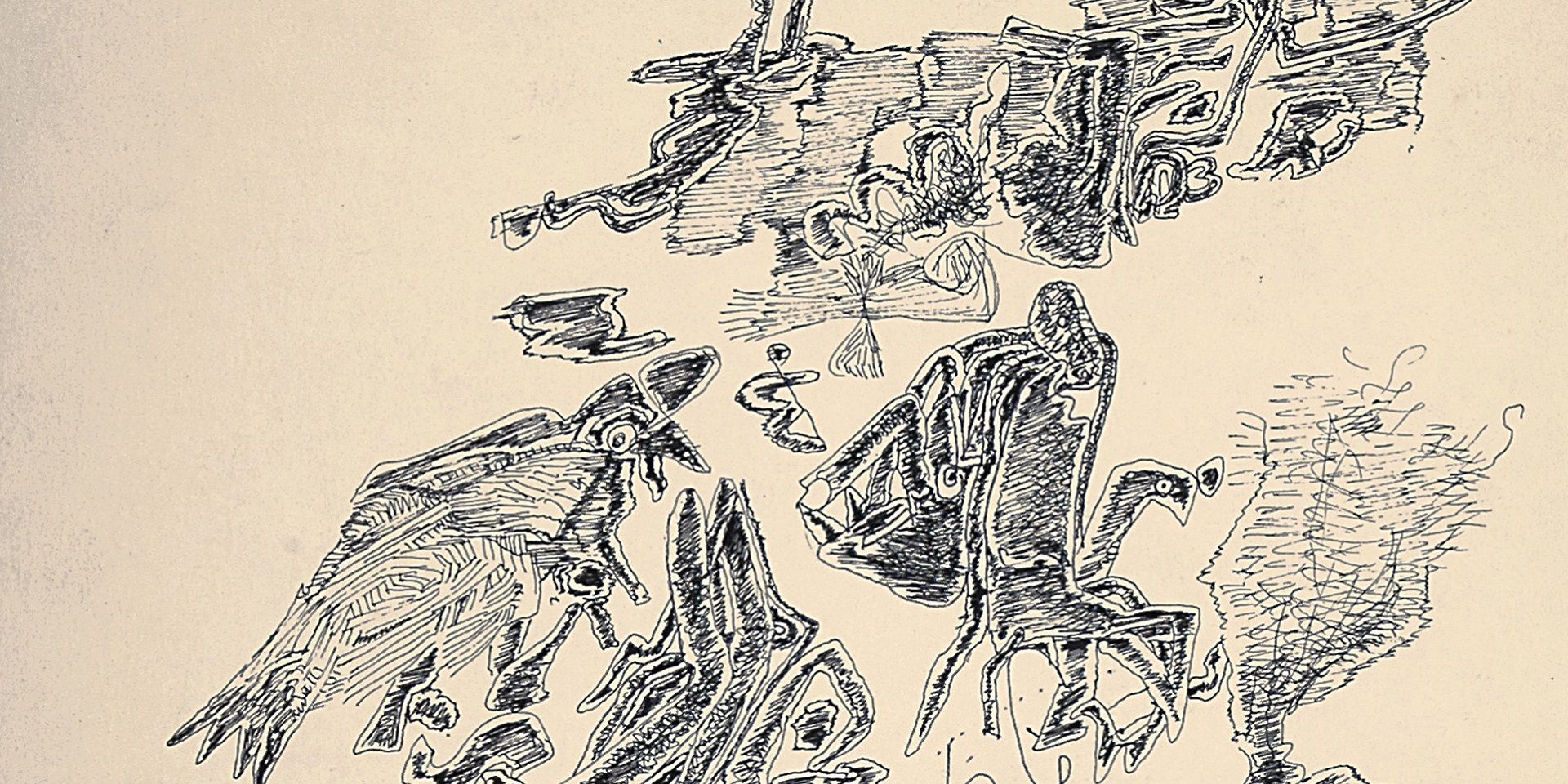

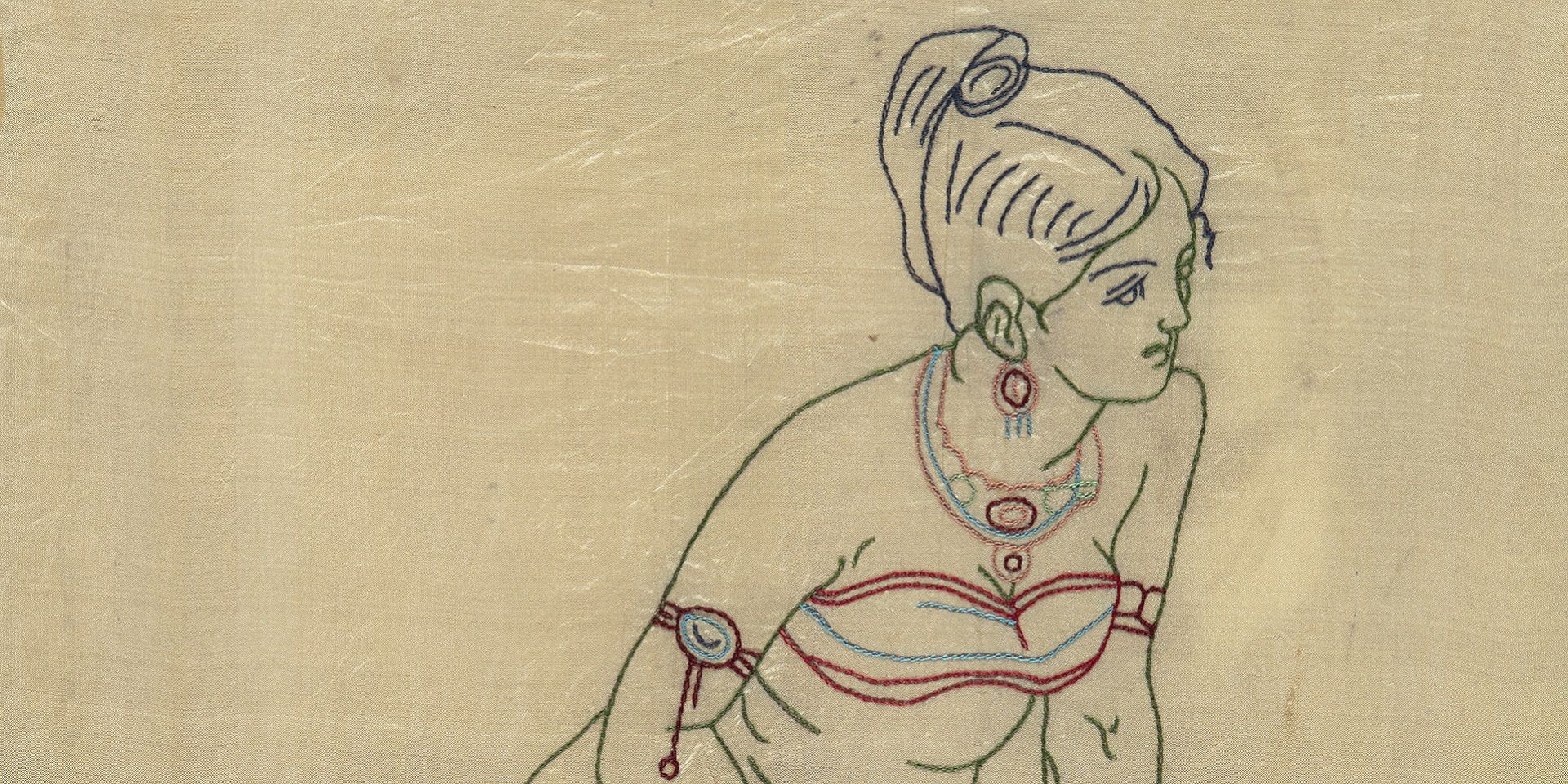

Sunil Das, Sketch Book, 1956, Ink, sketch pen and graphite on paper 29.7 x 10.7 x 0.2 in. Collection: DAG |

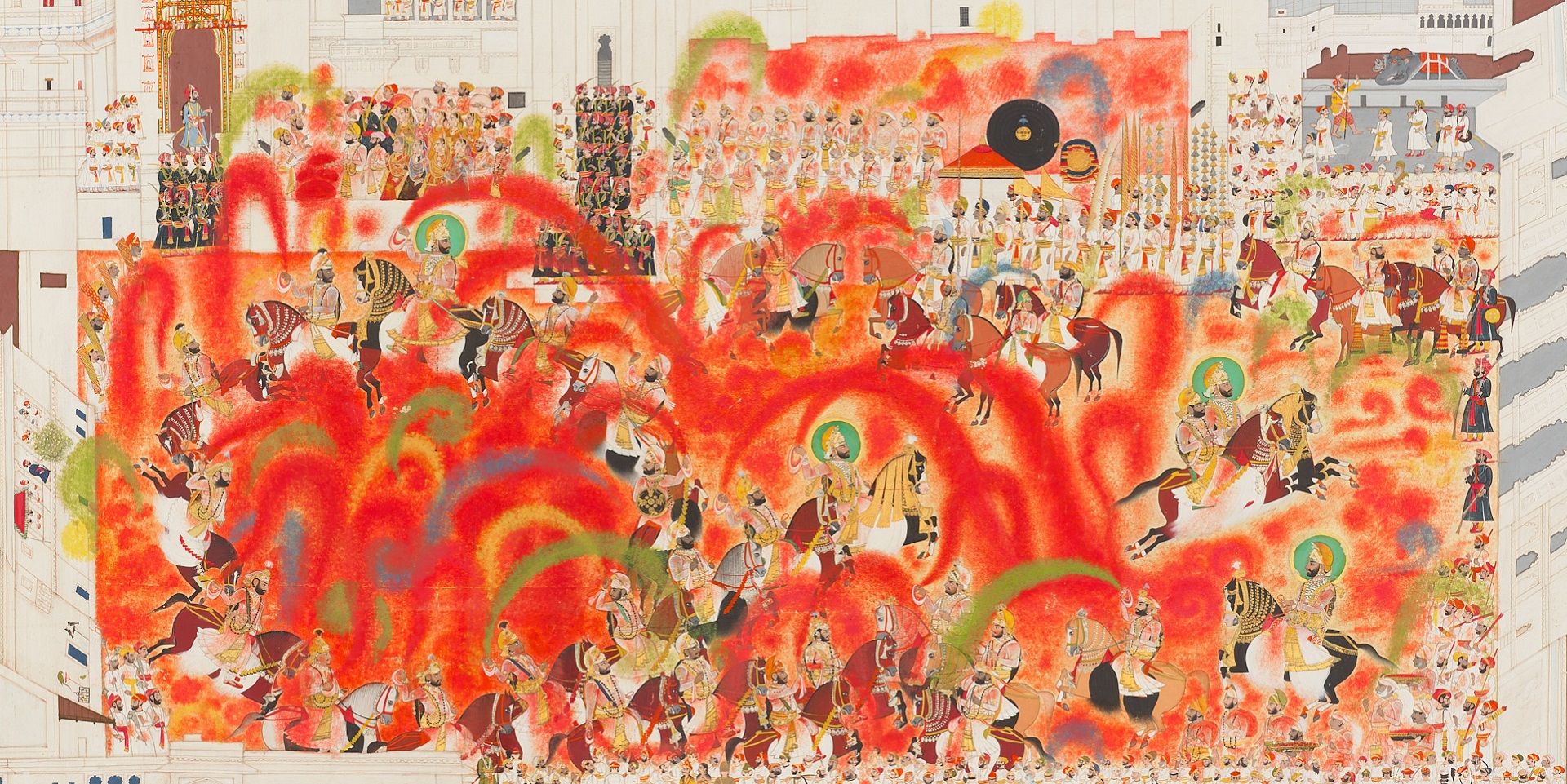

Indeed, the times were confusing. In 1957, the ambitious project of Dandakaranya Development was initiated with an estimated budget of Rs. 1 billion. The West Bengal government had by then declared that they had reached the ‘saturation point’ and could rehabilitate no more refugees. Now, the plan was to shift the refugees from the platforms and the relief camps to Dandakaranya (comprising portions of Orissa and Chhattisgarh) where they would be working as cultivators and labourers for the improvement of the region. This was not the first initiative to relocate the refugees outside West Bengal. Known as the policy of dispersal, it had begun on an experimental basis in 1949 when two hundred refugee families were sent off to Andaman for the development of the islands. Since then, thousands of families from East Bengal were sent across the country as the chief minister of West Bengal kept reminding the center that rehabilitating this displaced population was a national responsibility, not a provincial one. The dispersal policy had two declared objectives: supplying labour force for the national development and the rehabilitation of the Bengali refugees. Indeed, the times were confusing. In 1957, the ambitious project of Dandakaranya Development was initiated with an estimated budget of Rs. 1 billion. The West Bengal government had by then declared that they had reached the ‘saturation point’ and could rehabilitate no more refugees. Now, the plan was to shift the refugees from the platforms and the relief camps to Dandakaranya (comprising portions of Orissa and Chhattisgarh) where they would be working as cultivators and labourers for the improvement of the region. This was not the first initiative to relocate the refugees outside West Bengal. Known as the policy of dispersal, it had begun on an experimental basis in 1949 when two hundred refugee families were sent off to Andaman for the development of the islands. Since then, thousands of families from East Bengal were sent across the country as the chief minister of West Bengal kept reminding the center that rehabilitating this displaced population was a national responsibility, not a provincial one. The dispersal policy had two declared objectives: supplying labour force for the national development and the rehabilitation of the Bengali refugees.

|

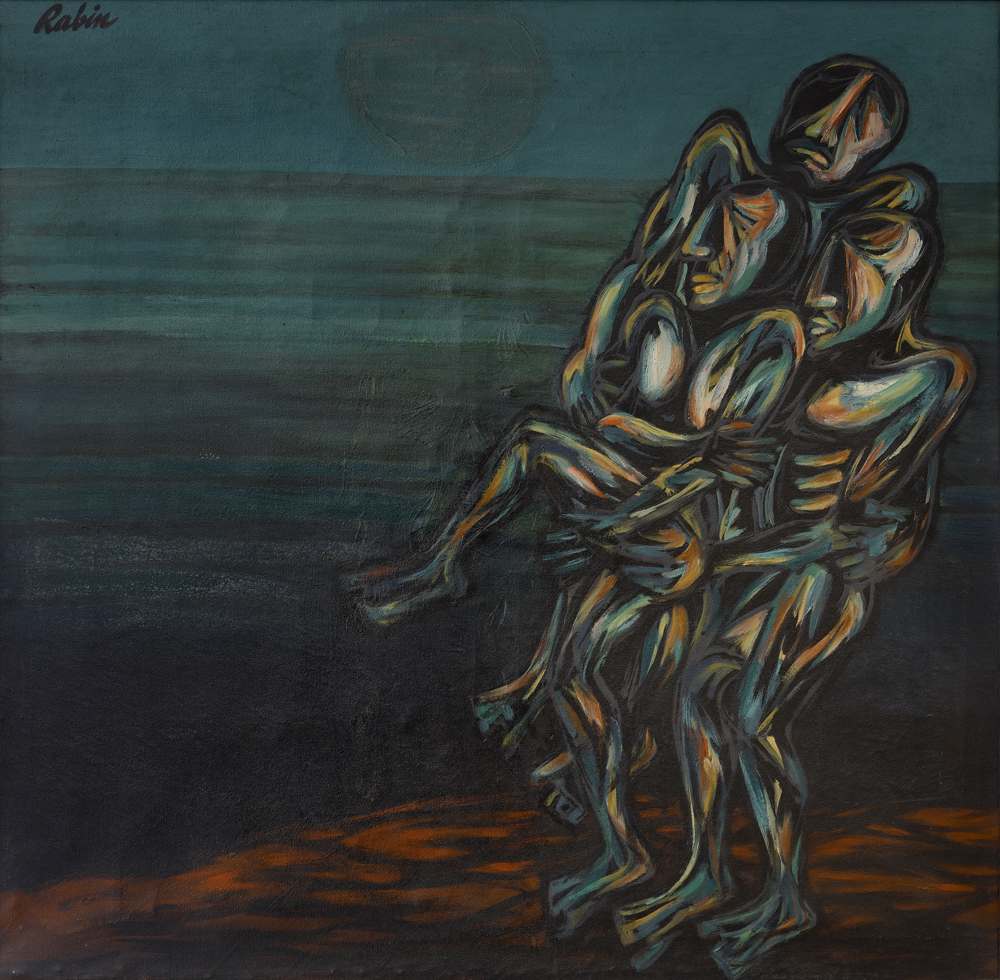

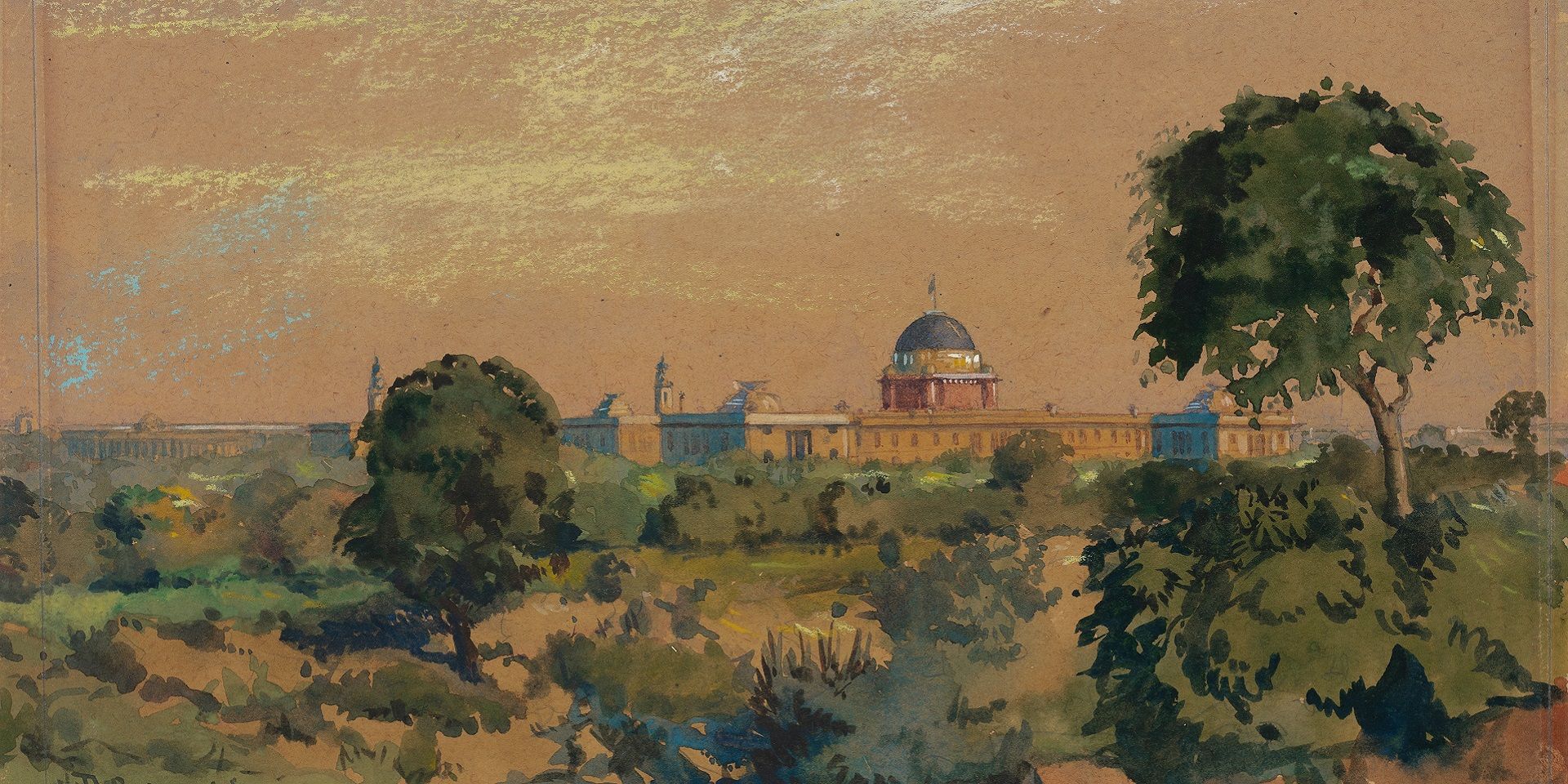

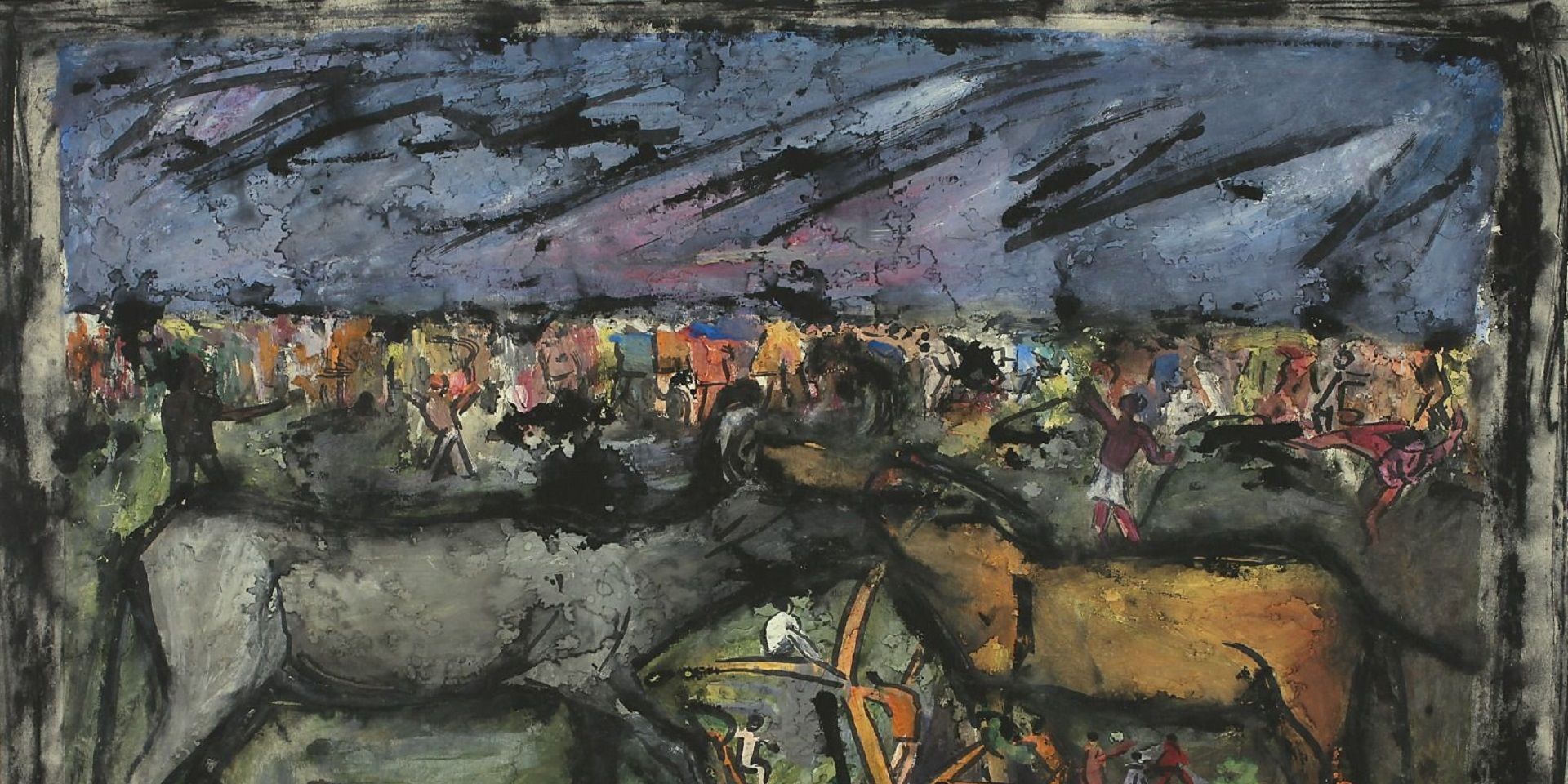

Sunil Das, Sketch Book, Ink, charcoal, conte and graphite on paper, 10.7 x 29.7 x 0.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Before the commencement of Dandakaranya project, the two major recipients of the Bengali refugees were Bihar and Orissa. Unfortunately, many who were sent to these states, returned to West Bengal, and often ended up again at the busy railway platforms of Calcutta. The high rate of desertion of the refugees from the camps and colonies of Bihar and Orissa, and the horror stories they brought with them, made the Sealdah residents skeptical about Dandakaranya. Arid land, harsh climate, water scarcity, lack of medical and educational facilities, hostile locals, absence of alternative livelihood options were cited as the reasons for the returns of the refugees from these provinces to West Bengal. Even platforms of Sealdah and Howrah were better, many of them opined. At least, they gave access to Calcutta where the refugees could find odd jobs to fend themselves, and could wait for better alternatives. As they learnt about the condition of the refugees in Bihar, Orissa and elsewhere, the platform refugees of 1957-58 knew that Dandakaranya would not be different. Hence, they wanted rehabilitation within West Bengal. Rather than going to Dandakaranya, they preferred to wait at Sealdah like the returnees for better opportunities in Calcutta and West Bengal. Waiting, for them, was not necessarily an expression of helplessness or powerlessness. Rather, through waiting and rejecting what the government had to offer them, they exercised agency.U. C. R. C. also supported their demands saying that with proper planning and land reform, enough land could be freed to rehabilitate all the refugees within the state. The government, however, kept pushing for Dandakaranya since its commencement.

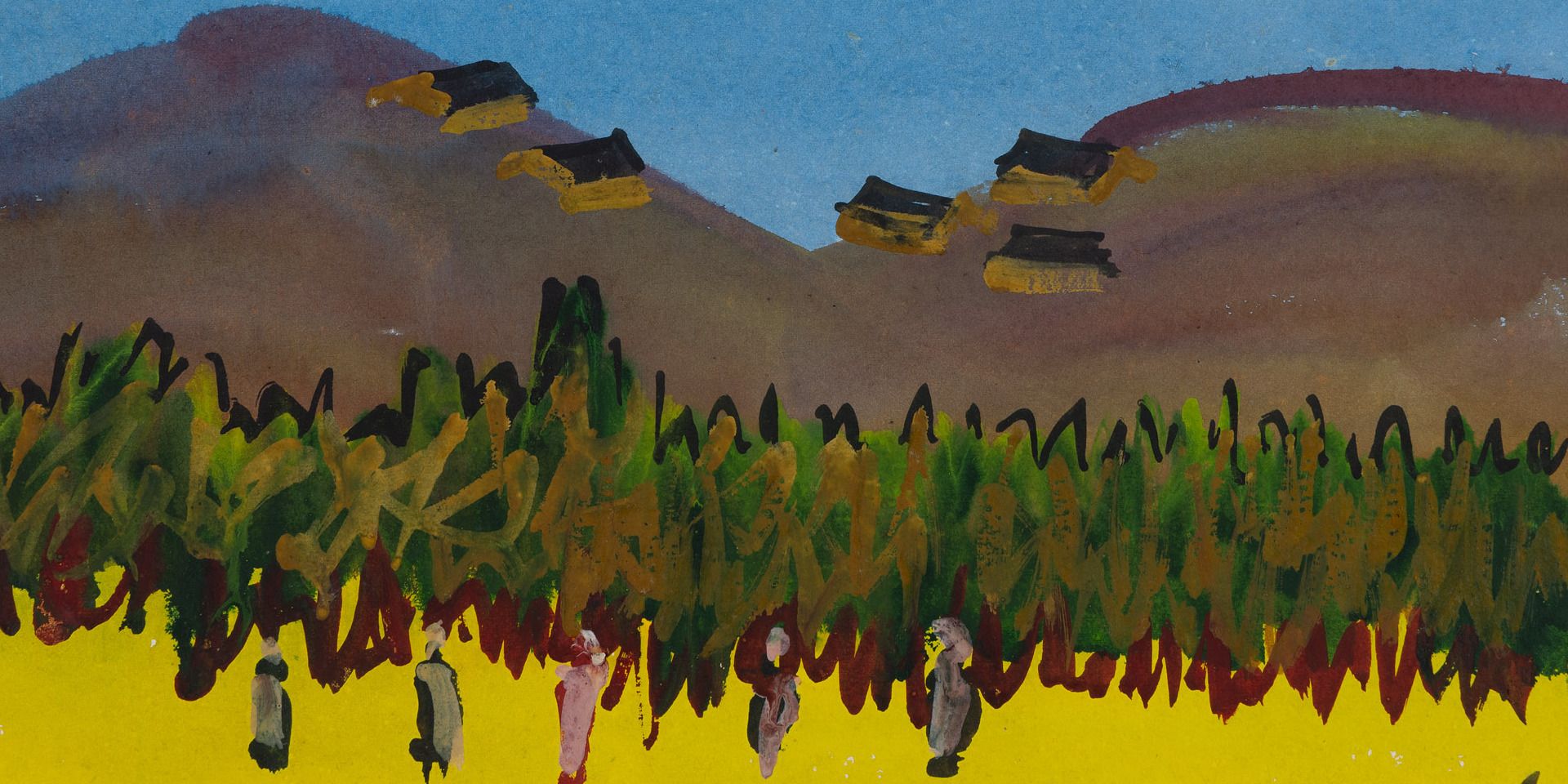

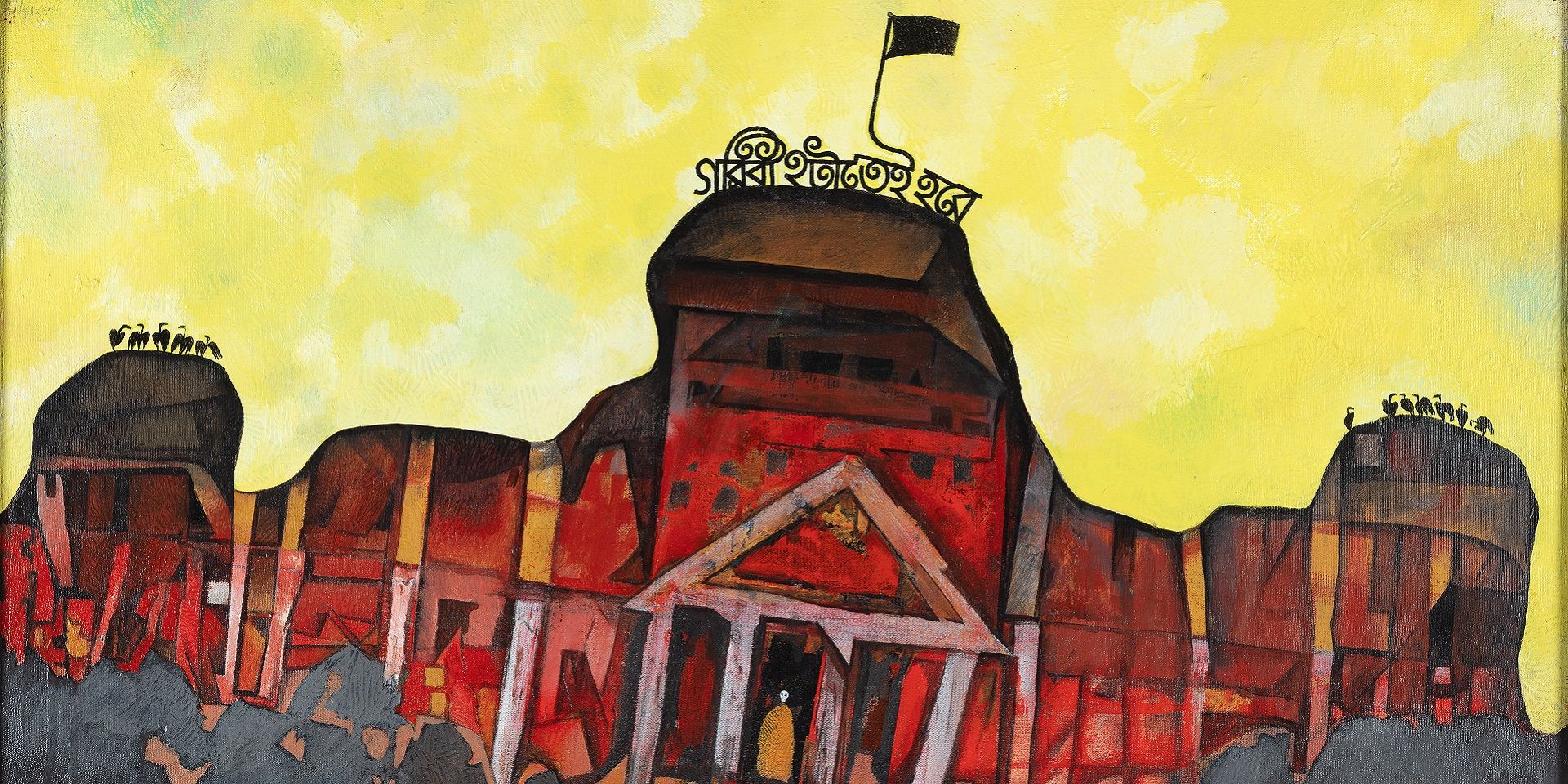

Rabin Mondal, Journey Towards Border, 1980-81, Oil on canvas, 42.0 x 43.0 in. Collection: DAG

The U. C. R. C., however, was not beyond criticism. The squatter colonies that had sprung up along the southern and northern edges of Calcutta in the early years after partition formed the major support base of this organization. The residents of these colonies had very different profile from those who were staying at the platforms. Colony-refugees were bhadralok—high caste, educated, often with white-collar jobs, and most definitely early migrants. At Sealdah, the refugees who squatted for long, were almost always Dalits, who had been cultivators or artisans in East Pakistan, and had been slow to leave East Pakistan for various reasons. They had no space in the bhadralok colonies. The leaders of the U. C. R. C., often coming from bhadralok refugee families themselves, though voiced their disapproval against government’s policy of dispersal, the needs of the colonies remained their priorities. Not surprisingly, the platform-refugees remained tentative in their support for this organisation; neither did they rally behind some other leaders or political parties.

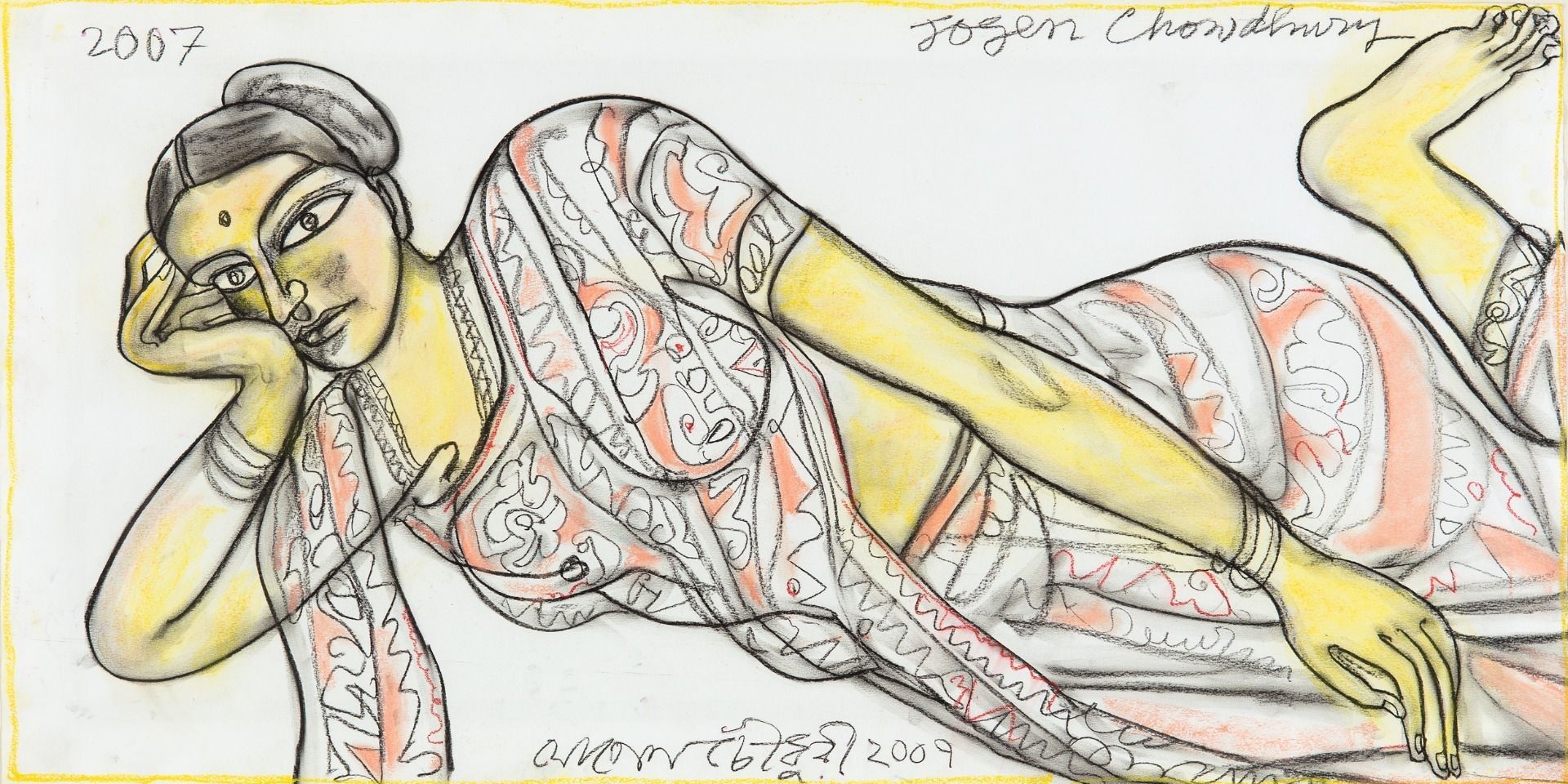

The platforms of Sealdah remained crowded with refugees till the middle of the 1960s, as can be seen in various documentary sketches and works by artists like Jogen Chowdhury, Sunil Das and Satish Sinha. Others, like Ganesh Haloi, also lived briefly on a railway platform (at Howrah), after being displaced from East Pakistan. Their numbers, obviously, fluctuated. Sometimes the station housed a few hundreds of them, and then there were phases when thousands jostled together. None of these squatting refugees saw Sealdah as their permanent residence. Meant to facilitate movements of passengers and goods, and logistically adequate to support few hours of waiting, Sealdah was not meant to become the home of the refugees. Being at Sealdah, however, empowered the refugees in a unique way—it provided them with the ability to obstruct. Modern mode of governing the city, as various urban scholars have shown, is to facilitate movements. Obstruction, thus, can be seen as resistance. And that made the refugees of the platform powerful political subjects. They obstructed the functioning of a railway station. And, there was always the threat that they would come out of the station premises and obstruct the city itself. On the other hand, the liminality of Sealdah as a space (like all railway stations—it shares an inside/outside relation with the city), also helped in allowing the refugees to put-up their resistance for almost two decades. While it impacted the urban life, it was outside the city itself and did not obstruct the movements within the city per se. While the opposition tried to bring the Sealdah refugees within the city, their lukewarm response to such efforts perhaps emboldened their right to wait and allowed them to bargain for better rehabilitation measures.

|

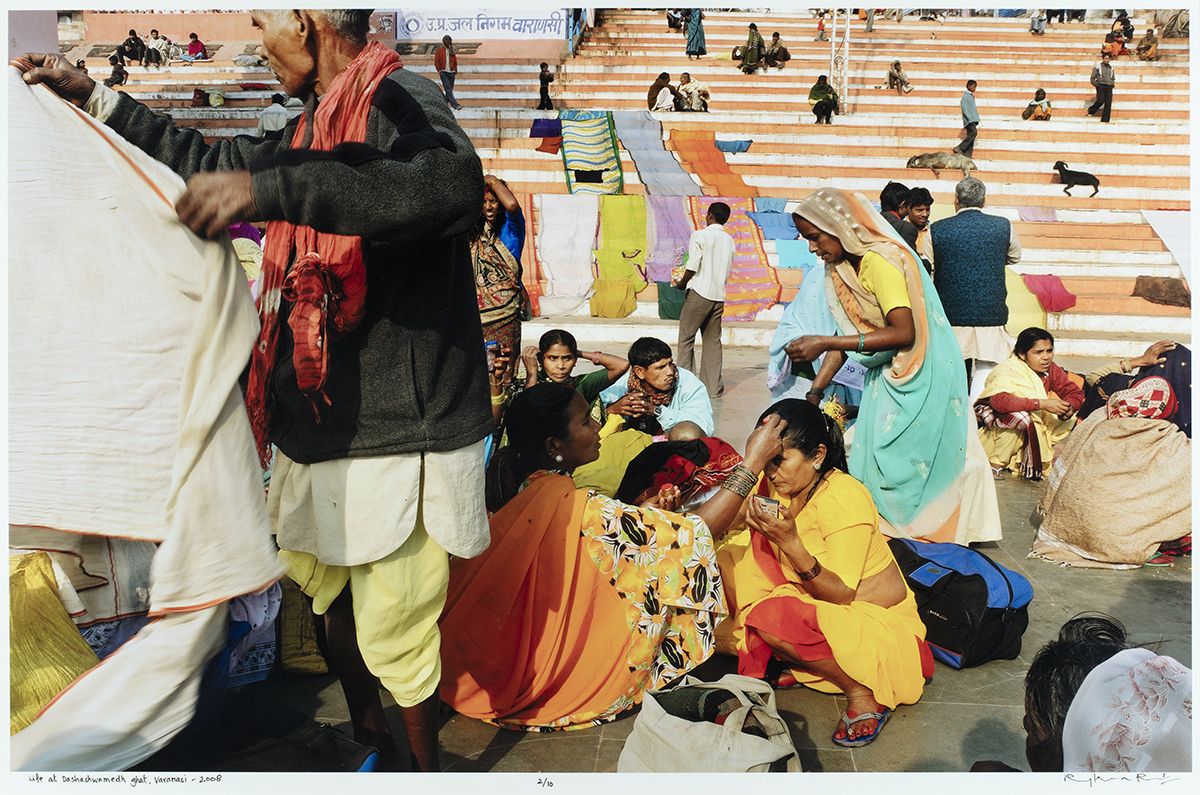

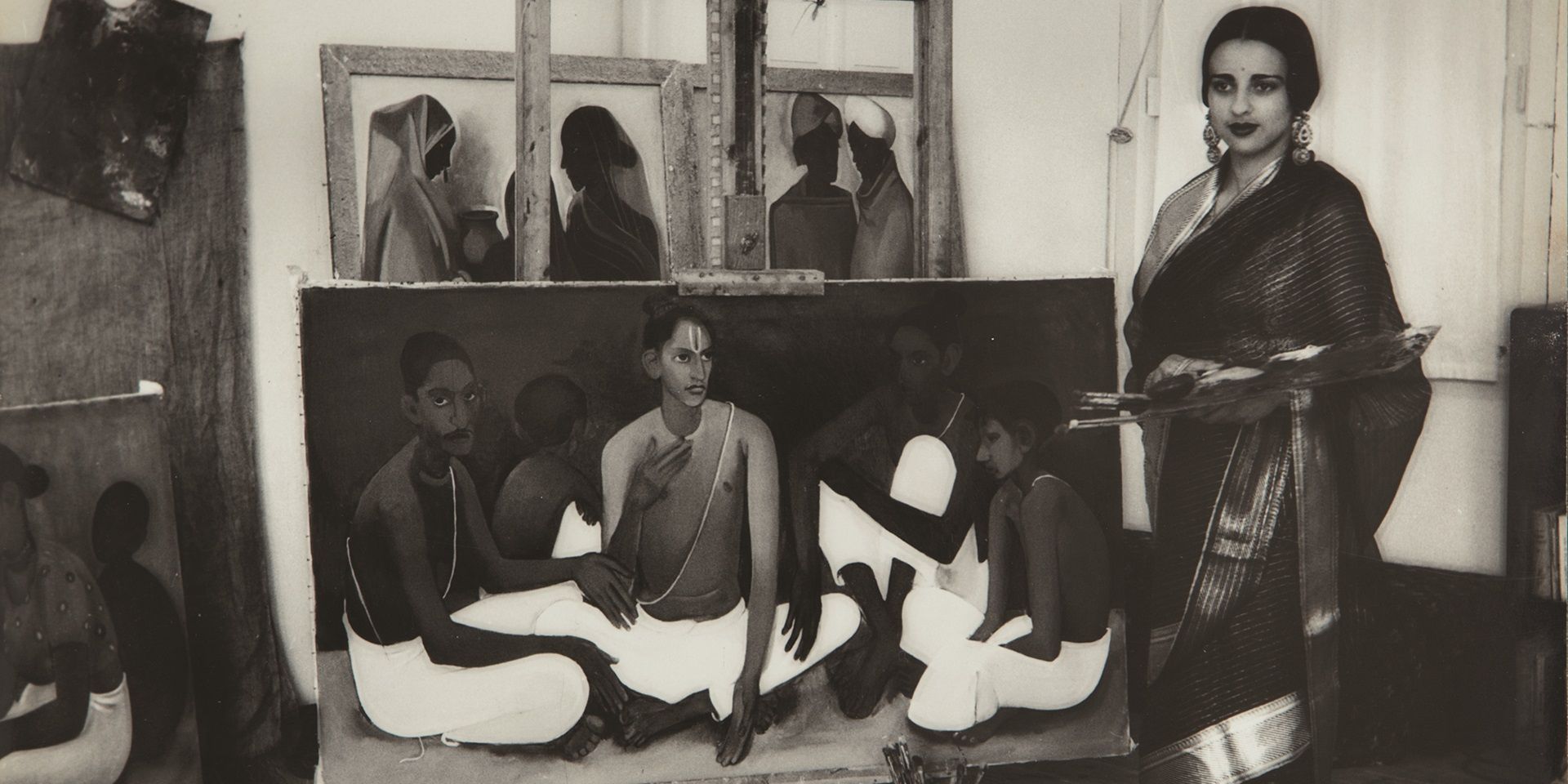

Historian Anwesha Sengupta discusses the politics of waiting at Sealdah, for 'The City as a Museum, Kolkata', 2025. Image courtesy: DAG Museums |

References:

a. ‘Copy of Secret Report No. Nil dated 6.2.58 from R.I.O Sealdah’, Sudha Roy (Bolshevik Party of India), F. No -67/39; Part III, IB Records, West Bengal State Archives

b. Jugantar, February 2, 1958.

c. Anwesha Sengupta, ‘Bengal Partition Refugees at Sealdah Station, 1950-1960’, South Asia Research, 42:1, 1-16.

d. Anwesha Sengupta, "They must have to go therefore, elsewhere": Mapping the Many Displacements of Bengali Hindu Refugees from East Pakistan, 1947 to 1960. Public Argument – 2, January 2017. PublicArgumentsSeries2.pdf

e. Creig Jeffrey ‘Guest Editorial’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26: 954–8.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025