Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

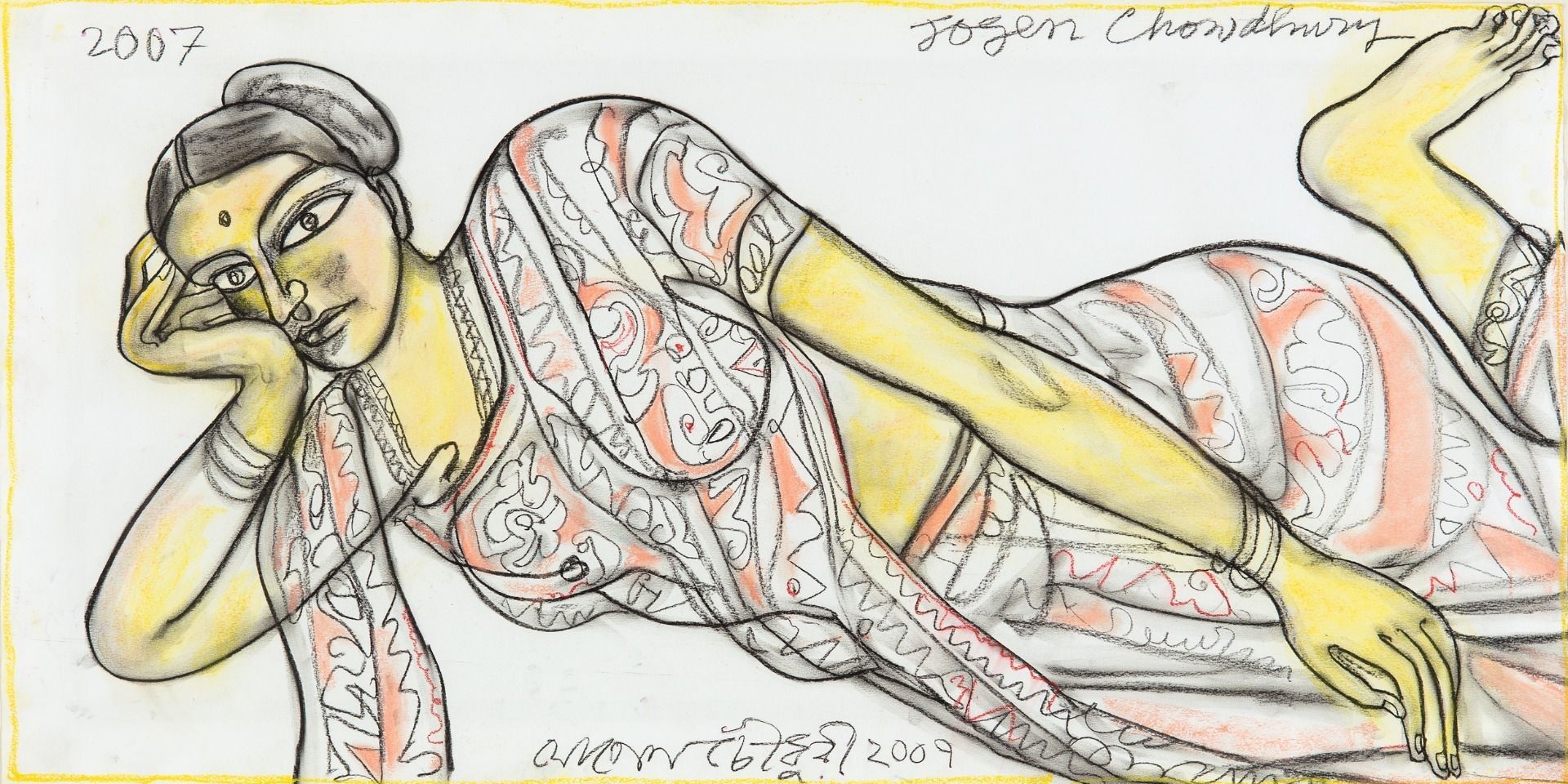

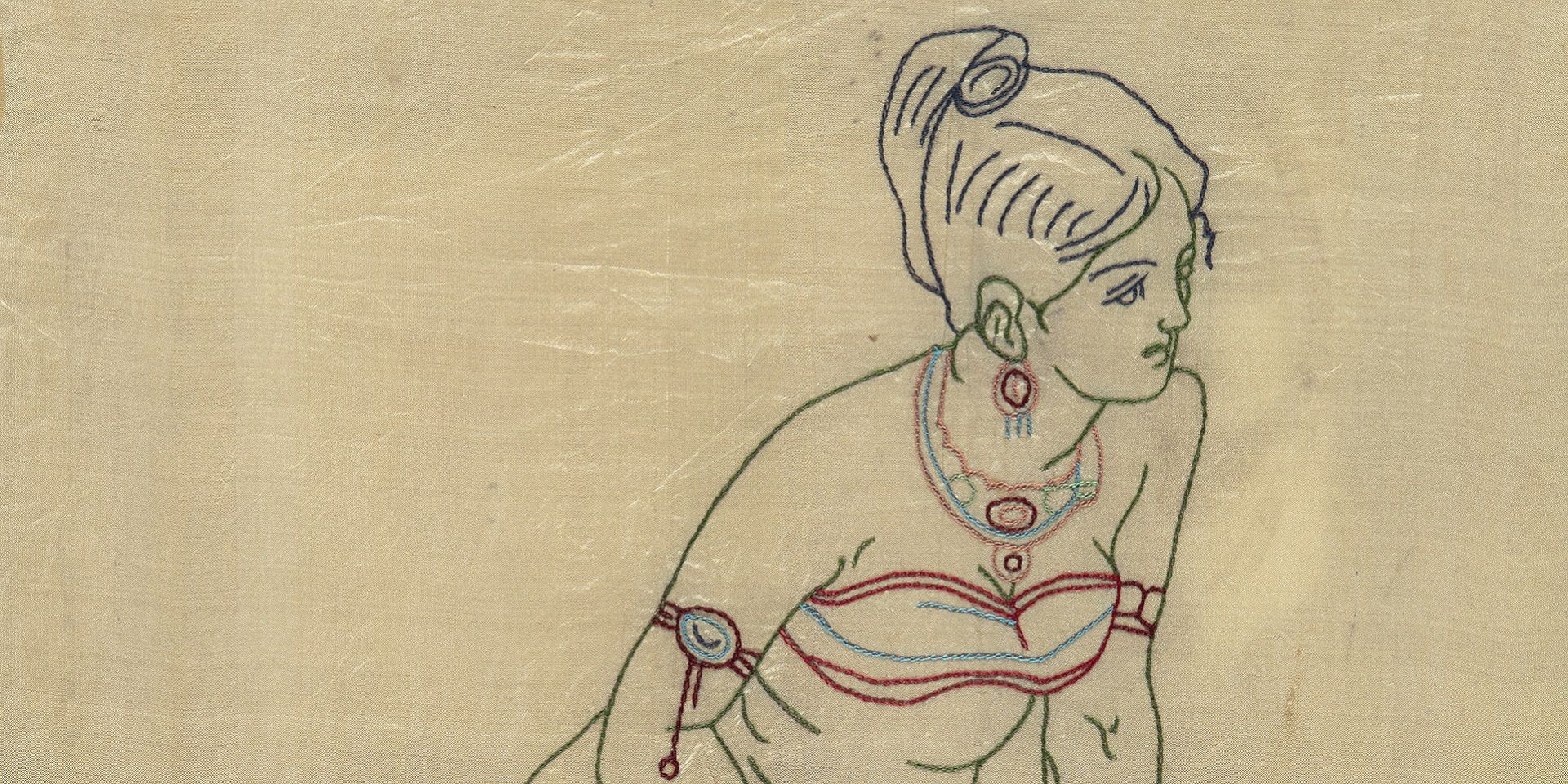

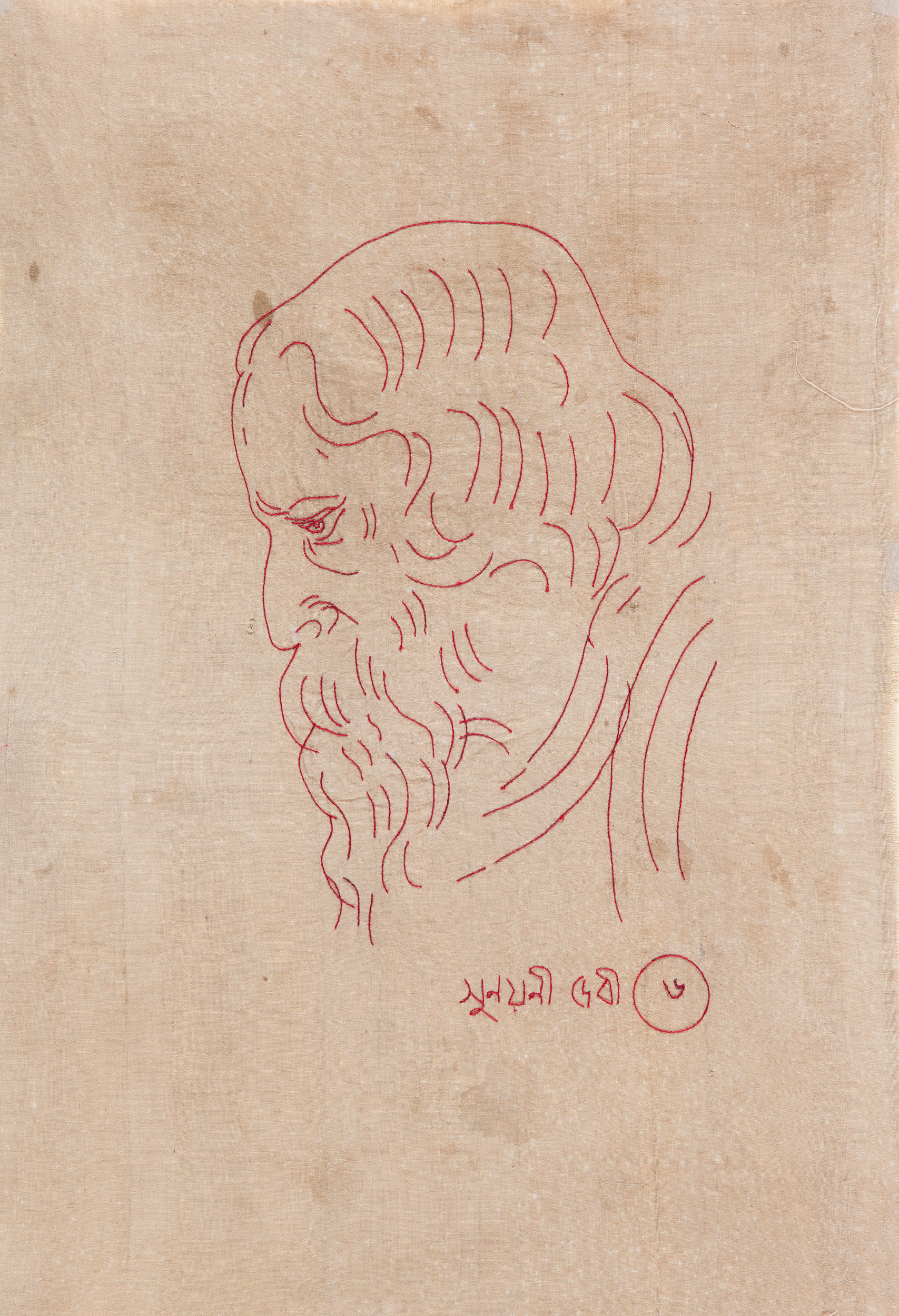

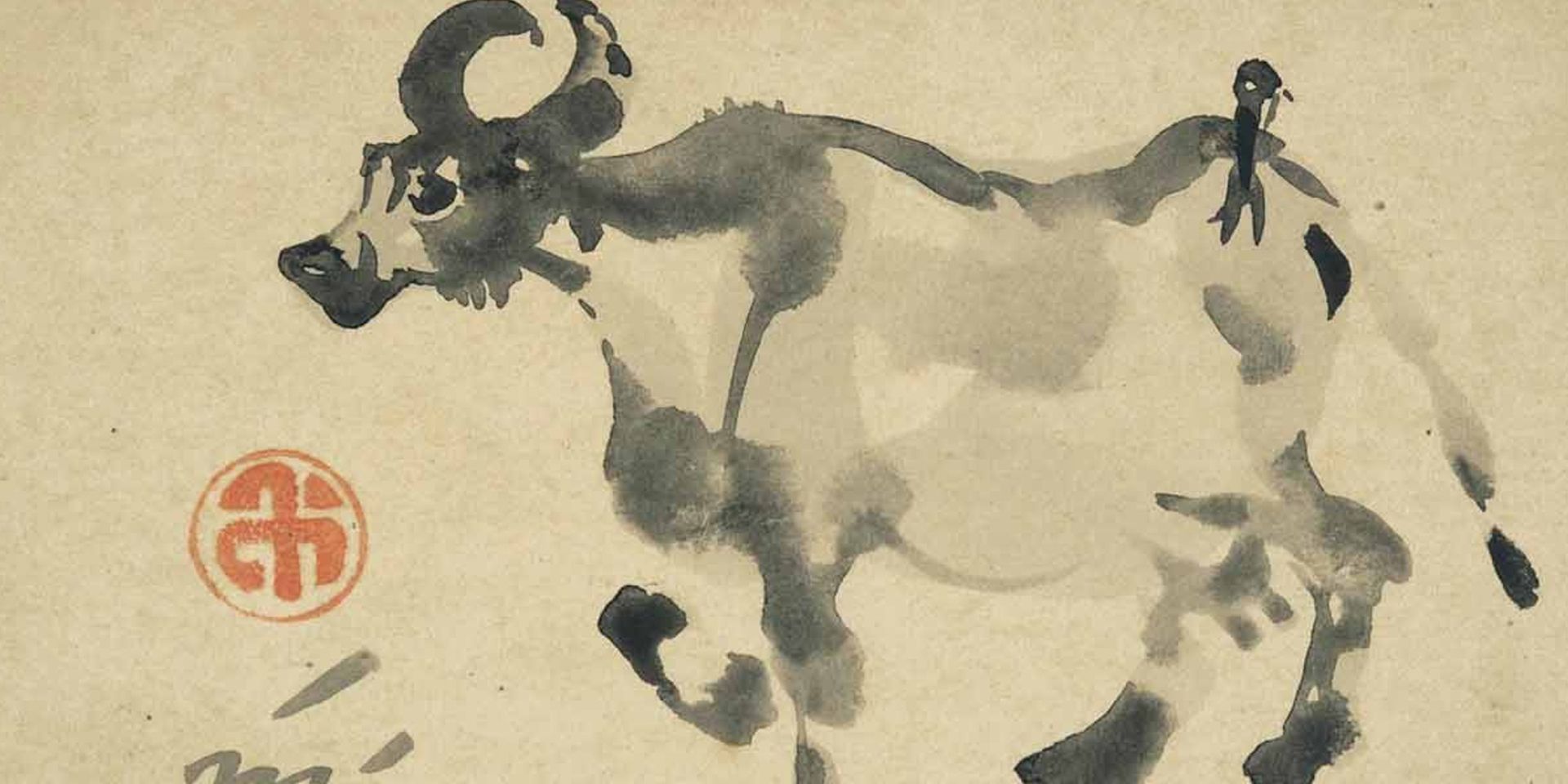

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, Embroidered silk laid on mount board. Collection: DAG

Dr. Soma Sen has spent many years chronicling the lives of artists who chose to stay away from the glamour of limelight and fame, while also researching and teaching as a professor of chemistry at Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College in Kolkata.

Dr. Soma Sen has spent many years chronicling the lives of artists who chose to stay away from the glamour of limelight and fame, while also researching and teaching as a professor of chemistry at Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College in Kolkata. Her purview has largely been the artistic and cultural landscape of Santiniketan and Kolkata (Calcutta) in the earlier half of the twentieth century—especially those decades which had witnessed a rich churning of creativity and the evolution of modern ‘Indian’ art in Bengal. By digging into the recesses of archival sources and collections held in old libraries, Sen continues to salvage forgotten aspects of the lives of both well-known or little-known artists, therefore addressing existing gaps in various popular narratives about art practice and art education in Bengal during these early years.

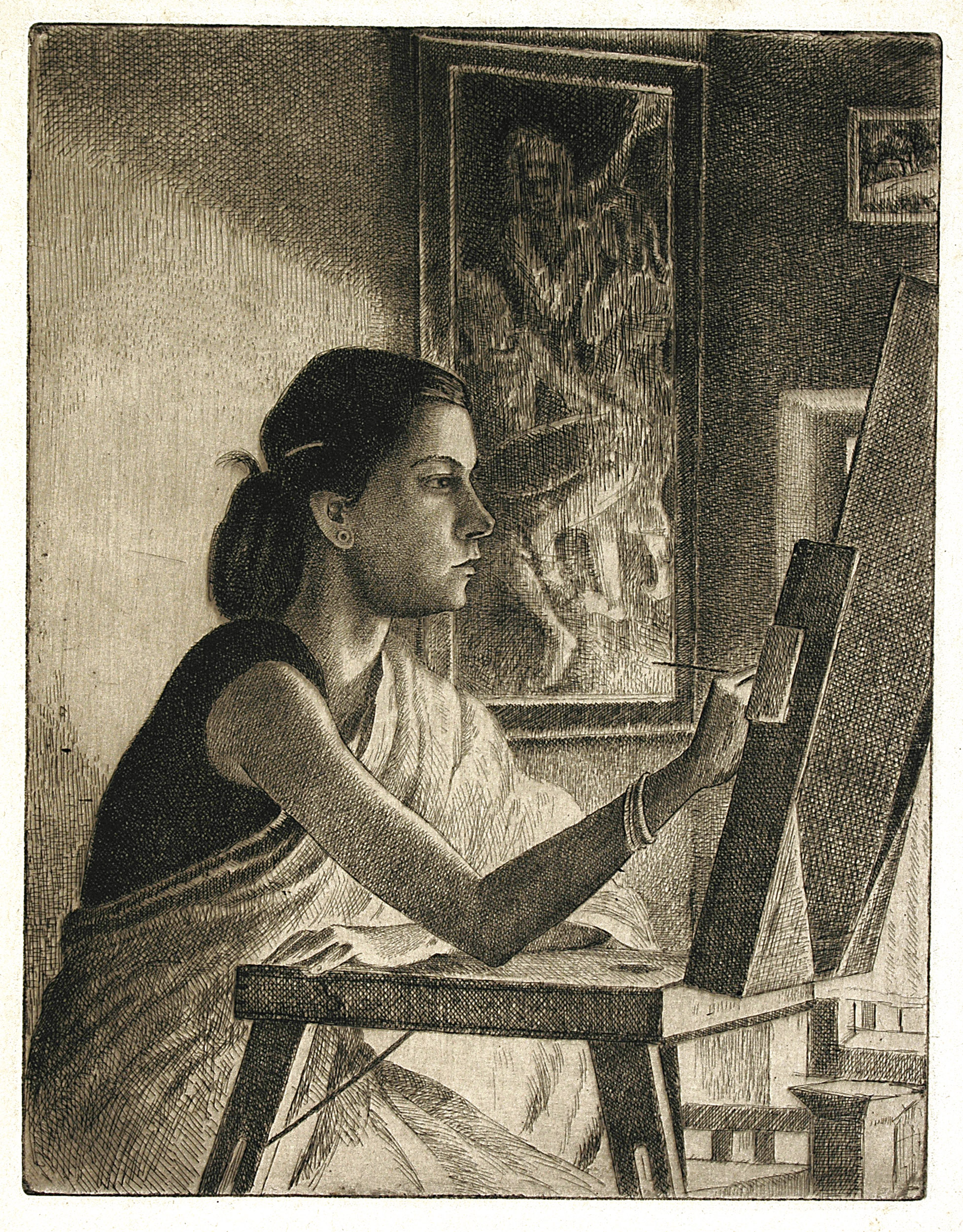

Sen’s book Abanindra Parampara (The Abanindranath Lineage), published by Signet Press in 2022, gives us a rare glimpse into the multi-faceted lives of some of the early pupils of the pioneering master of the Bengal School, Abanindranath Tagore. The book brings to the fore the practice and career of several overlooked artists belonging to the lineage of Abanindranath, such as Prosanto Roy, who were developing a distinct style of their own while inculcating the early innovations in the repertoire of neo-Bengal art. More recently, Sen has written on the lives and artistic endeavours of women since the early days of women’s education in colonial Bengal.

|

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, Embroidered silk laid on mount board. Collection: DAG |

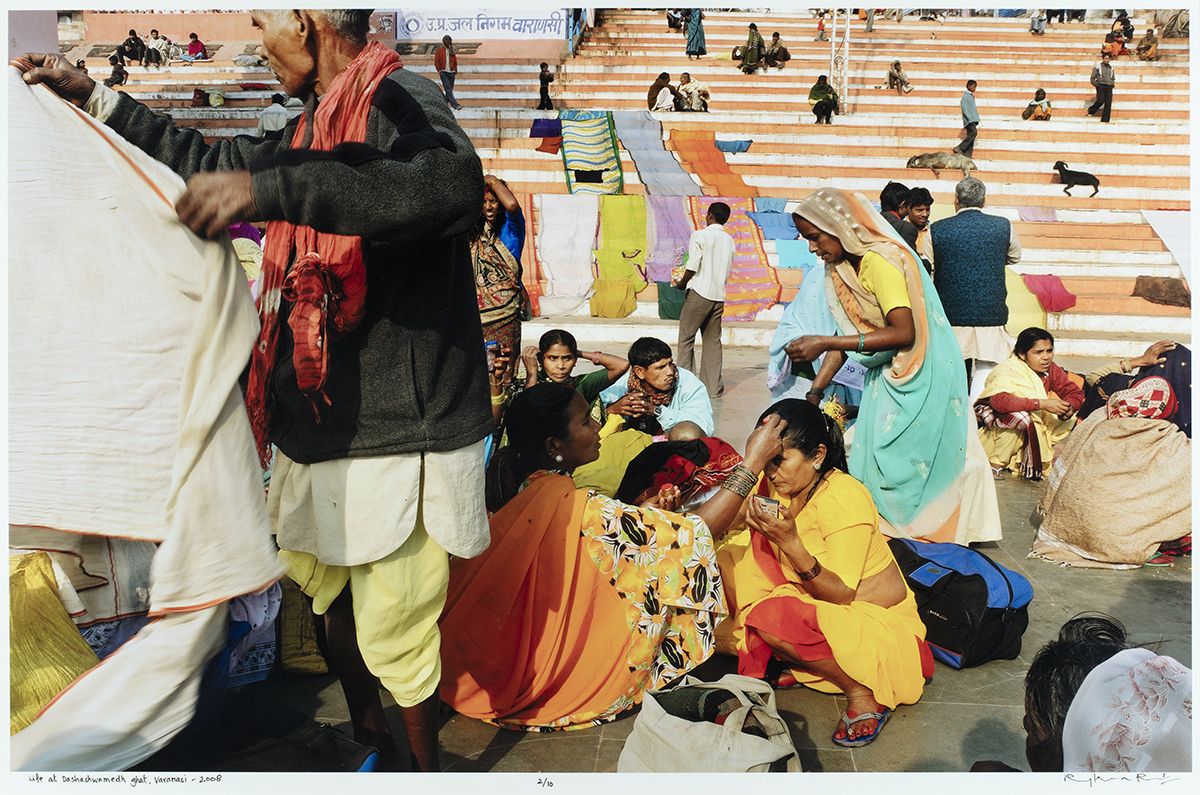

Although it is only in the 1940s that a large number were women were allowed within the hallowed halls of government art colleges across the country, and we witness the emergence of a few professional women artists on the cusp of independence, certain historical forces enabled a handful of women to access art education in Bengal during the early decades of the twentieth century too. While opening up new avenues in thinking about the socio-cultural milieu and limitations of the pedagogic framework within which these women attempted to carve out their own space, her writing also makes one re-engage with the pitfalls of a category like ‘woman artist’ and the gendered discourse of art history. She spoke to us about her areas of interest and what follows is an edited and translated version of the conversation.

|

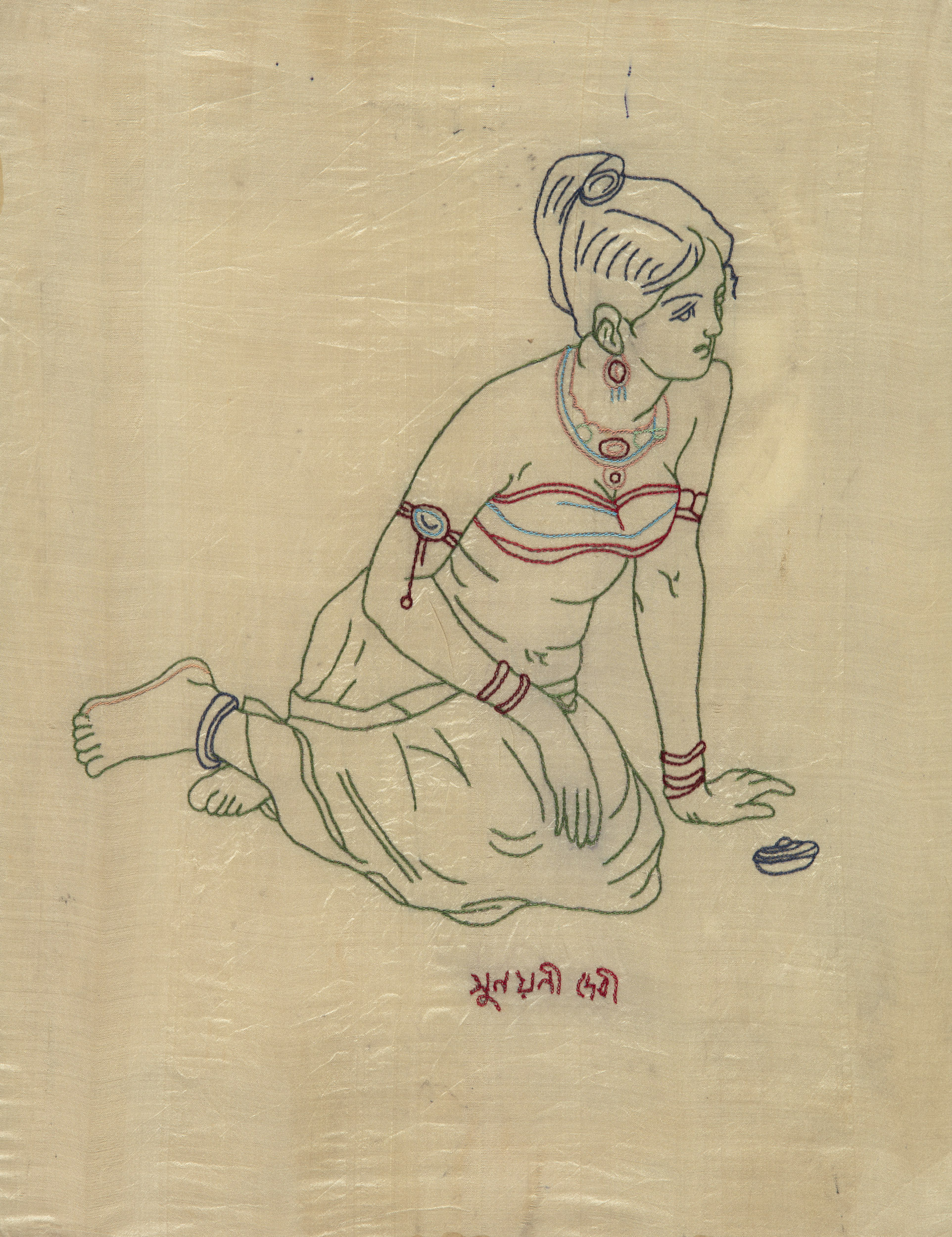

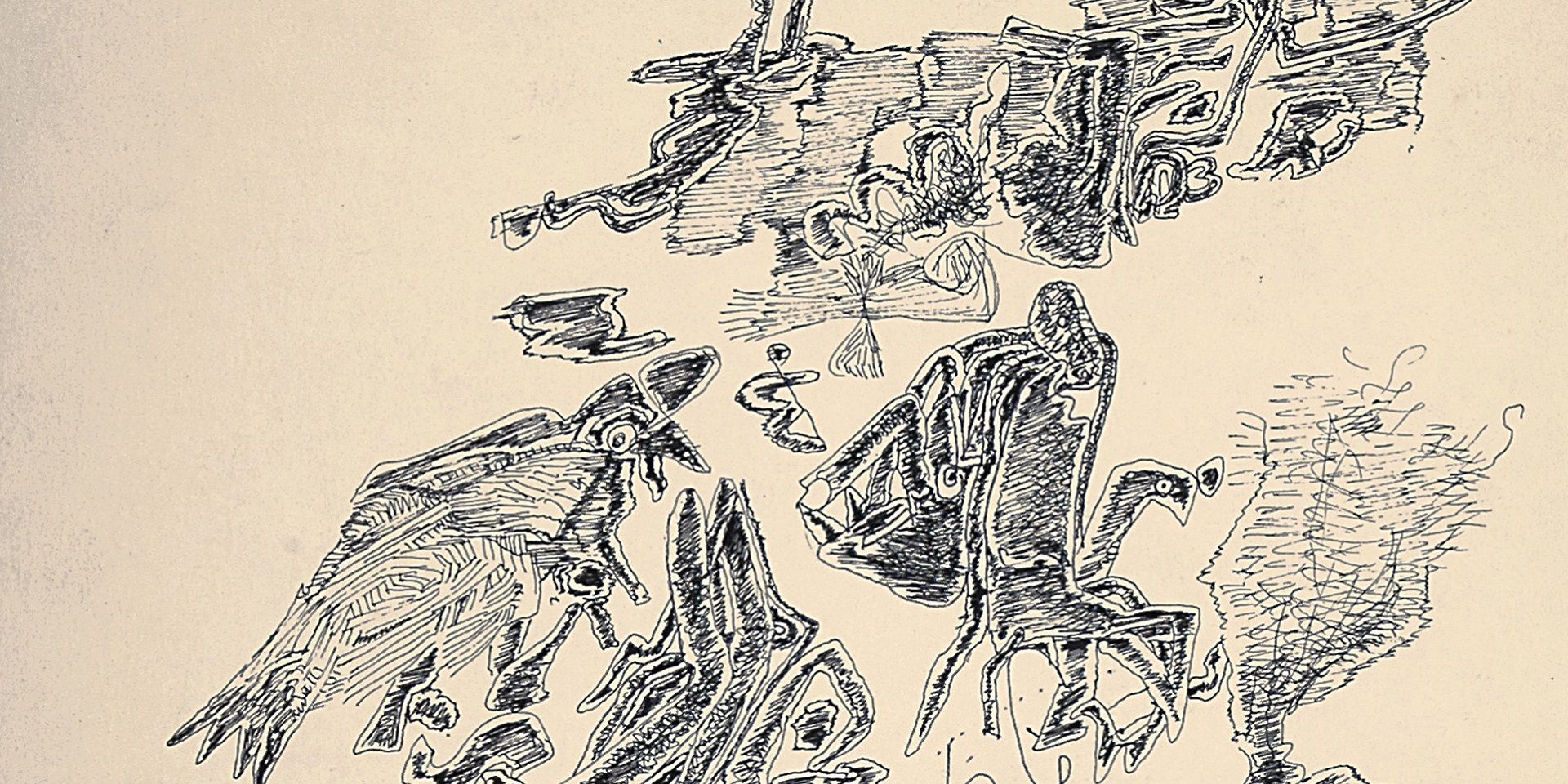

Ramendranath Chakravorty, Untitled, Etching on paper. Collection: DAG |

Q: The absence of any women artists in your recounting of the artistic lineage of Abanindranath Tagore in the book Abanindra Parampara is of course telling. Would you like to tell us about the initial sparks that set you off on your journey to find more about women artists?

Soma Sen: The first woman artist, most of whose works I had the opportunity to see up close, was Chitranibha Chowdhury. Her daughter, Chitralekha, had given me a portrait of Abanindranath Tagore by the artist to include in my book Abanindra Parampara (The Abanindranath Lineage). By this serendipitious turn of events I was able to use a work by one of the first women students of Nandalal Bose at Kala Bhavan who was not only illustrating covers for Des magazine, but was also working in other mediums and styles like oil, tempera, alpona and embroidery. Other than this she was also part of the early team of artists working on the construction of Kalo Bari (Black House) and the relief work illustrating its façade in Santiniketan. Despite leaving behind a significant body of work, Chitranibha the artist remains relatively unknown and therefore marginalised in the art-historical canon of early Santiniketan artists. Moreover, alongside Sukumari Devi, she became one of the first women art educators at Kala Bhavan when she took up Rabindranath’s offer to join as a Professor of Art. A lot of these women artists, Chitranibha included, have left reminiscenses of Rabindranath, and I was drawn to these anecdotes and reminiscences. We had organised an exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in 2014, and at around the same time Chitranibha’s recollections of Rabindranath were published as ‘Rabindrasmriti’. Her memoirs offer us a homely, intimate portrait of the world-famous bard.

|

Mukul Dey, Abanindranath Tagore, 9.5 x 7.5 in., 1937. Collection: DAG |

|

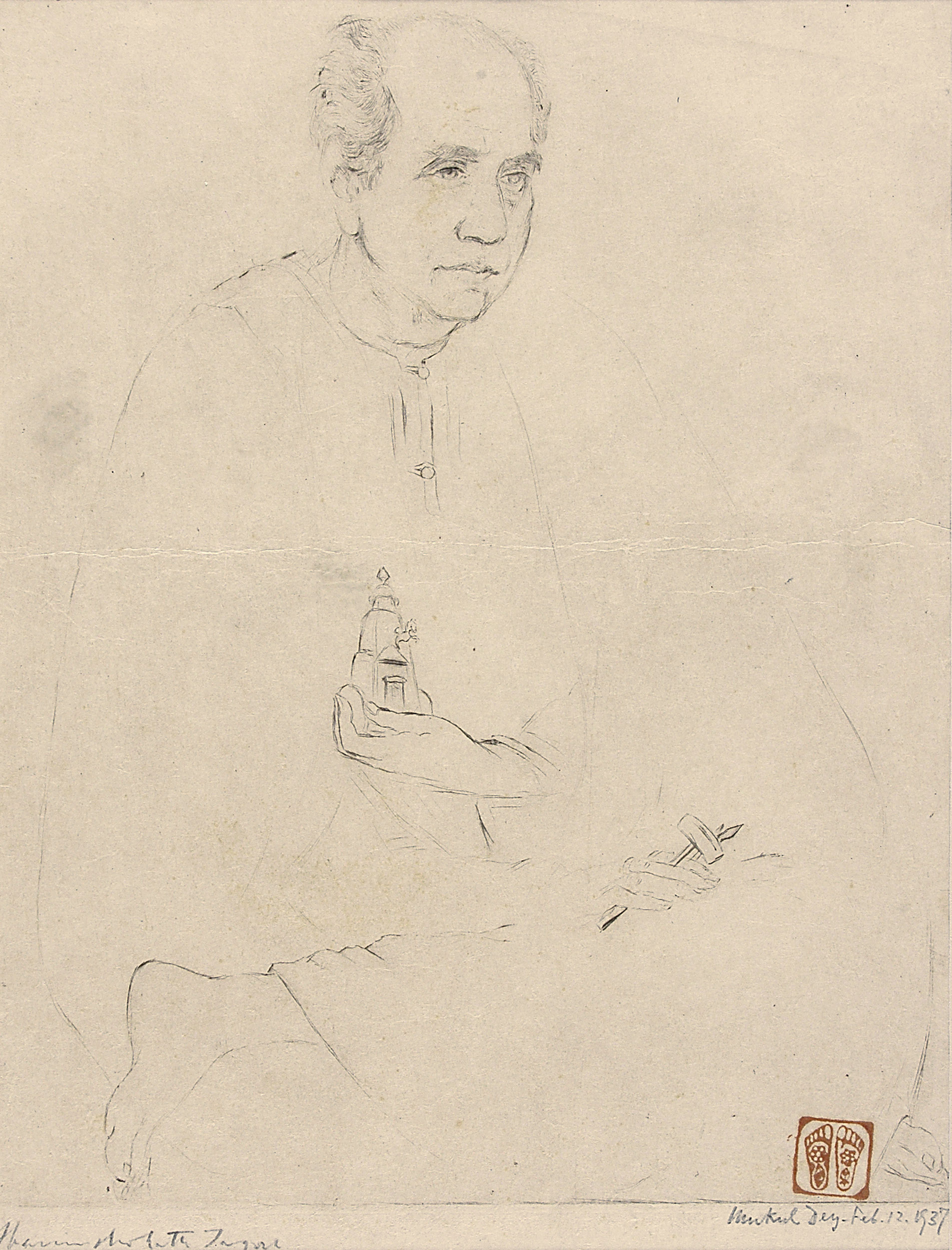

Sunayani Devi, Rabindranath Tagore, Embroidered on cotton fabric, 20.5 x 13.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Chitranibha was the student of Nandalal Bose. Nandalal had passed out from the Government College of Art and Craft and had worked at various creative ventures, none too financially viable. Abanindranath had asked him to teach at the Bicitra Studio for a salary of sixty rupees at the time, and here he went on to teach some women mostly from the Tagore household and other upper-class families like Rama, Ena, Parul, Shanta and Pratima Devi, the two daughters of Sir Nilratan Sircar, and some others. The Bicitra Studio had emerged as an early platform for art education in Calcutta.

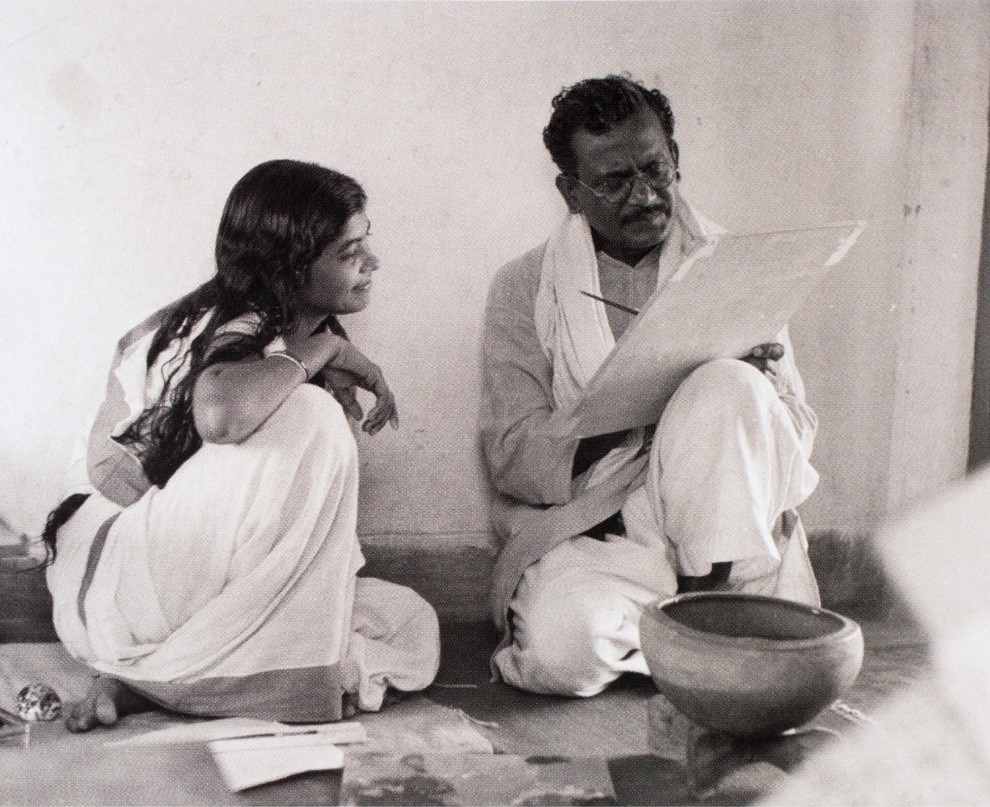

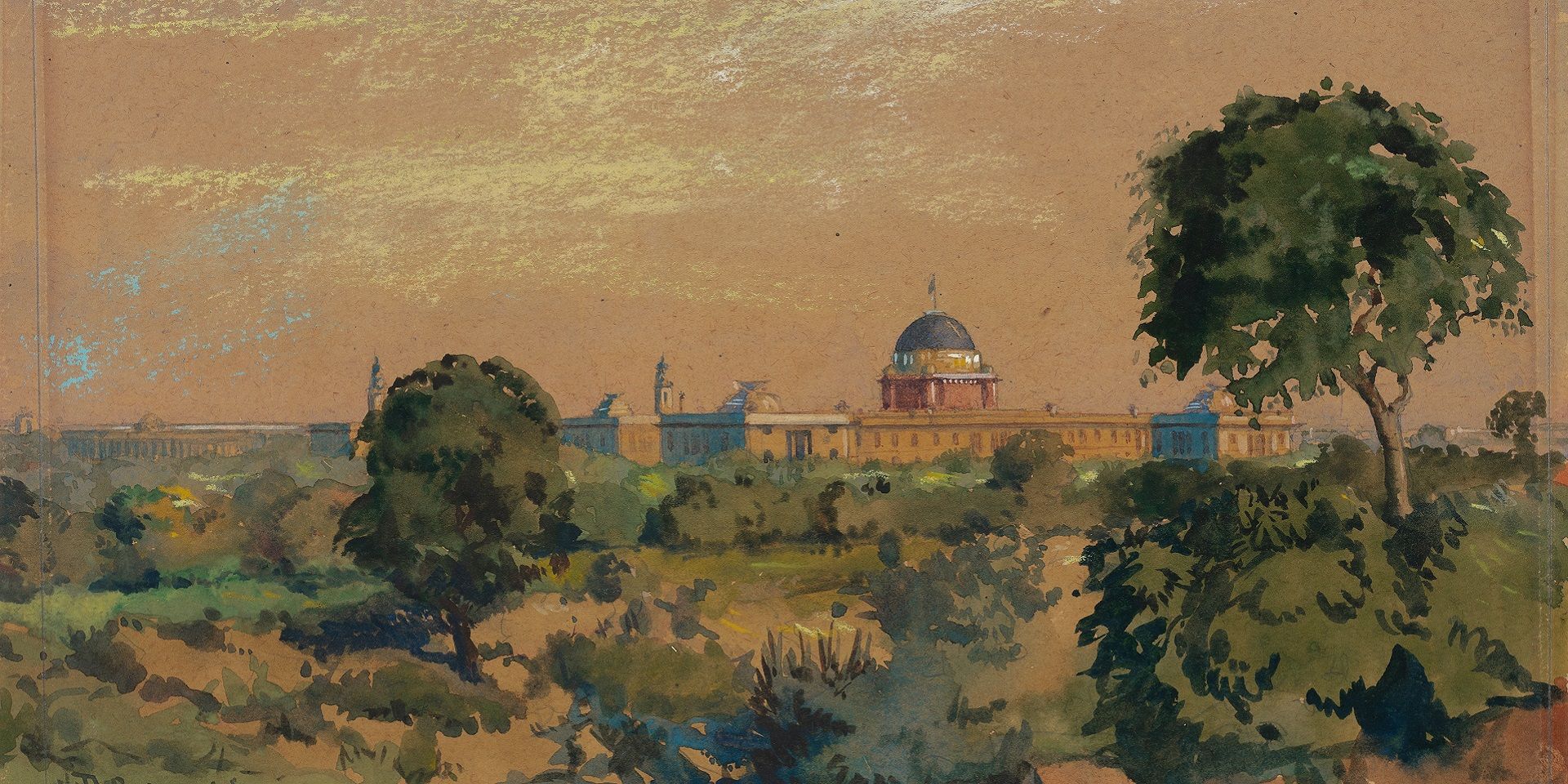

Nandalal Bose teaching a student at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan. Collection: DAG

Q: There was undoubtedly a gradual gentrification, as art was being recognised as a somewhat acceptable profession in some circles in Bengal at around the turn of the century. Do you think that this notion of relative respectability and the emergence of the professional ‘artist’ affected the sale of artworks during these early years?

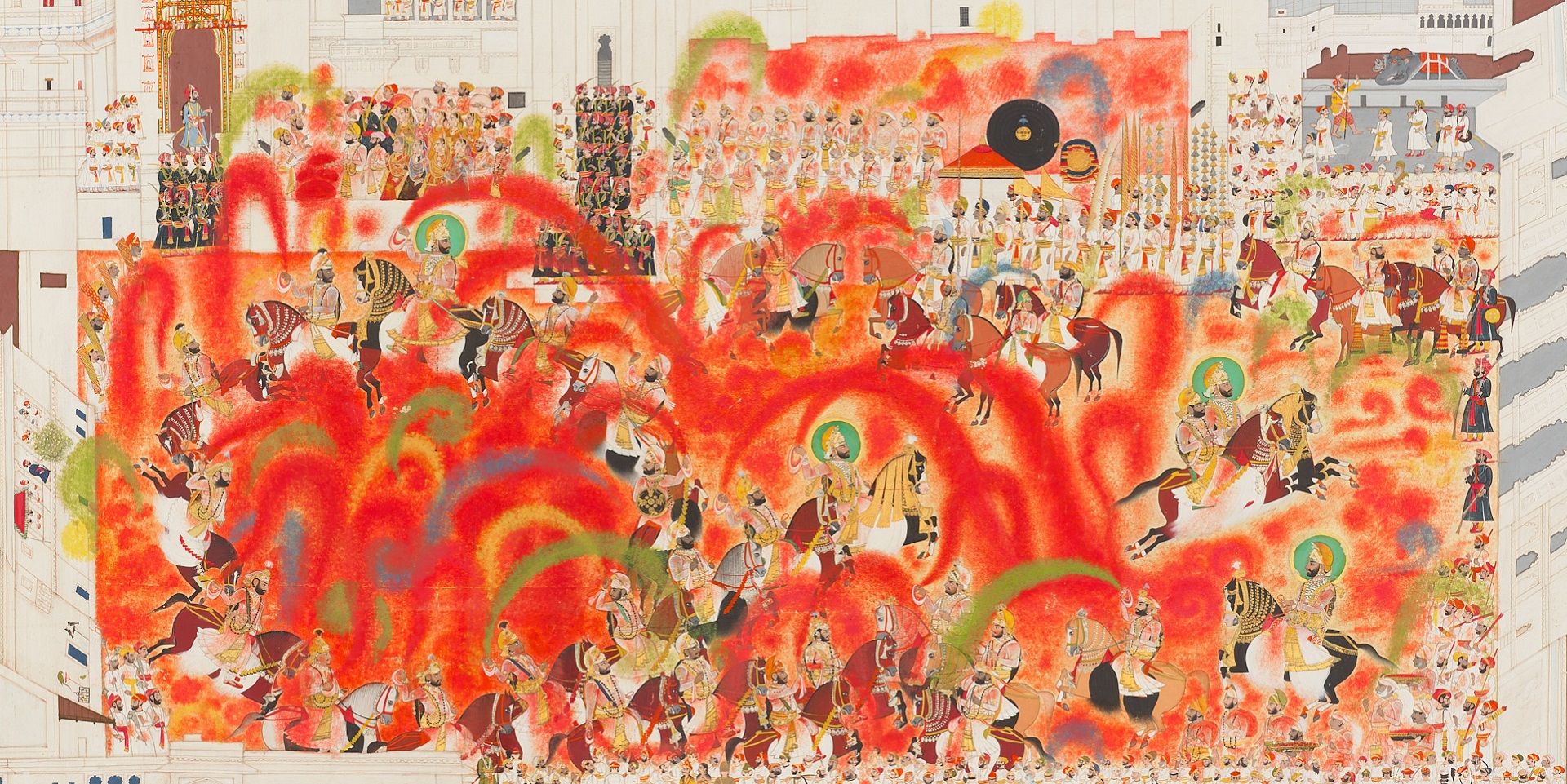

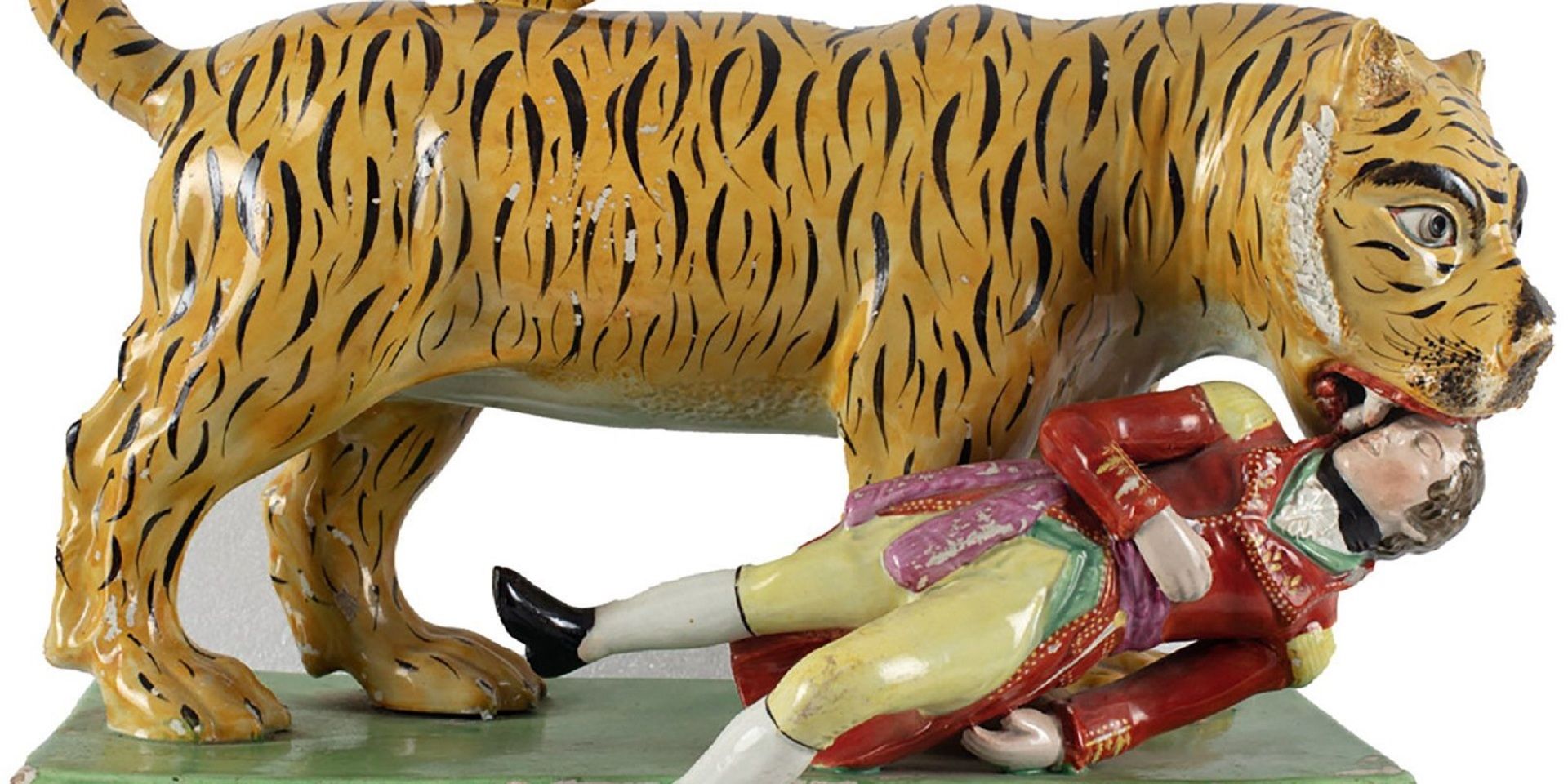

Sen: Hardly. As for being practising artists, women were not significantly a part of any sort of professional world at this time, let alone pursuing art. I mean, in a scenario where due to the absence of a proper network in place men had a hard time selling their work, one can only imagine how difficult it would have been for women. There were a few white patrons, mostly Englishmen, who did pay good money for some of the artworks. An instance of paintings selling for decent prices would be the Bauhaus Exhibition in 1922 where paintings were sold for two hundred, three, four or even five hundred rupees. Some works by Sunayani Devi and Pratima Devi were also exhibited as part of a pathbreaking artistic collaboration between the Bauhaus artists and the Indian Society of Oriental Art.

From the information we get from books on the period, it seems that quite a few of Girindramohini Dasi’s artworks sold at the Hindu Mela (fair), and that she had even received some commissioned work. As a well-known poet, Girindramohini was often invited to deliver lectures in public gatherings. Artist and writer Shanta Devi writes in her memoirs, Purbasmriti, that instead of idling her time away at such gatherings, Girindramohini would sketch. She was from an affluent family, which, had supported her in her pursuits. Girindramohini used to co-edit the journal Jahnavi along with Sri Naliniranjan Pandit for a few years, and we can see many of her paintings and sketches reproduced in the magazine pages. She used to design the covers of her books herself, and also illustrated the pages. I have seen a few of her works in copies of Jahnavi held by libraries, although most of them are now damaged or torn.

|

Sunayani Devi, Milkmaid, Gouache on paper, 15.5 x 12.7 in., c. 1920s. Collection: DAG |

Q. Like Girindramohini and later Hashirashi Devi, many of these women are indeed remembered today as important contributors to Bengali literature, rather than as artists. Would you say that the relative acceptability and financial viability of the writer’s profession around this time led these women to prioritise writing over pursuing art?

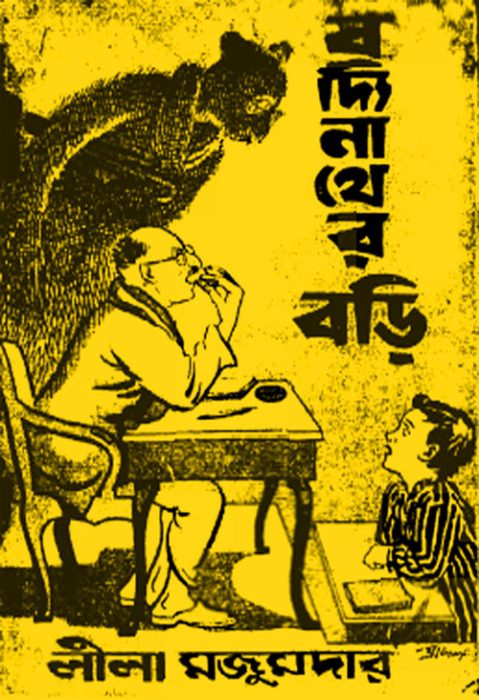

Sen: Apart from the rare instance of Girindramohini, there seems to be no other woman artist in Bengal from the early decades of the twentieth century for whom art proved to be a source of financial sustenance. We have the example of Leela Mazumder, but then again we primarily remember her as a gifted writer. Yet she was quite a prolific artist who had been sketching and drawing while she was at school. Her first publication, Boddi Nather Bori (Baidyanath's Pill), was published along with playful illustrations made by the author herself. She would often make line sketches, mainly in Chinese ink, while also using colour for other works. One might of course say that having been born in the Ray family of the U. Ray and Sons fame, Leela Mazumdar was able to nurture her artistic leanings more succesfully than perhaps other talented women of her times. The story goes that once while visiting Darjeeling with her family, the writer-artist expressed a desire to sketch the hills while the others were out enjoying all that the town had to offer.

|

Cover of Leela Mazumdar's Boddi Nather Bori (Baidyanath's Pill). Image source: Public Domain |

However, unlike what we know of Girindramohini Dasi, Sukhalata Rao, another member of the Ray family, did not really pursue her art practice in a major way. Like others in the family, she had also been trained by her father Upendrakishore Roychowdhury to paint, and would later dabble in mediums like Chinese ink and oils. Many of her works have been published in contemporary journals like Prabasi, Modern Review, Sandesh, Supravat, etc., and in the well-known Chatterjee's Picture Album published by the veteran publisher-editor Ramananda Chatterjee. Some of her more well-known works were reproduced in the pages of various Bengali and English books that she had written. As most of us are aware, a network of high-brow jounals in circulation in Bengal around that time played a significant role in the dissemination of artworks and shaping a conscious art public.

|

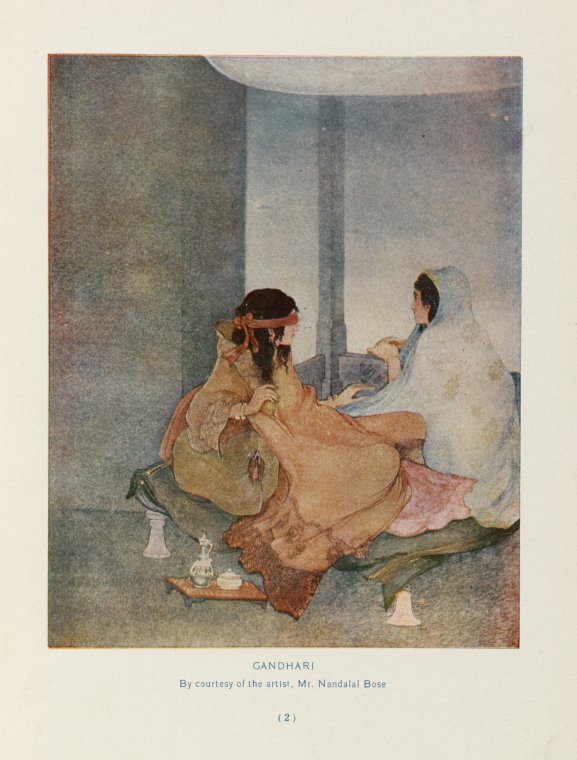

Nandalal Bose's work Gandhari, as it appeared on the pages of The Modern Review/ Chatterjee's Picture Albums and printed at U. Ray and Sons. Image source: Public Domain |

Q: With the advent of women students at Kala Bhavan we witness an atmosphere of co-education gradually taking root in Santiniketan during the 1920s. Around this time the appointment of the self-taught artist Sukumari Devi as a teacher of design (alpona and embroidery), is possibly one of the first instances of a woman art educator associated with a public forum. What role would you say women art educators had in the formalisation of liminal art forms like floor painting or alpona, and in subsequently paving the way for more women interested in pursuing art to train for a career?

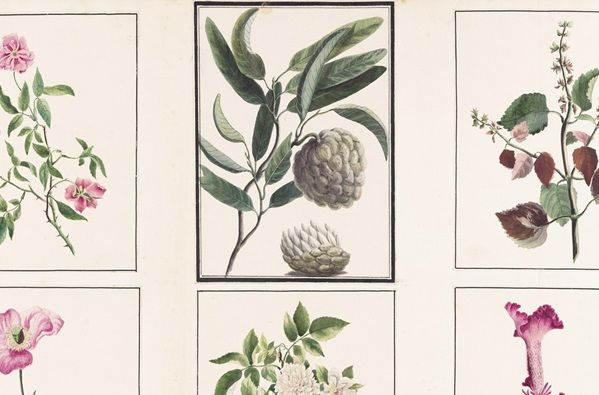

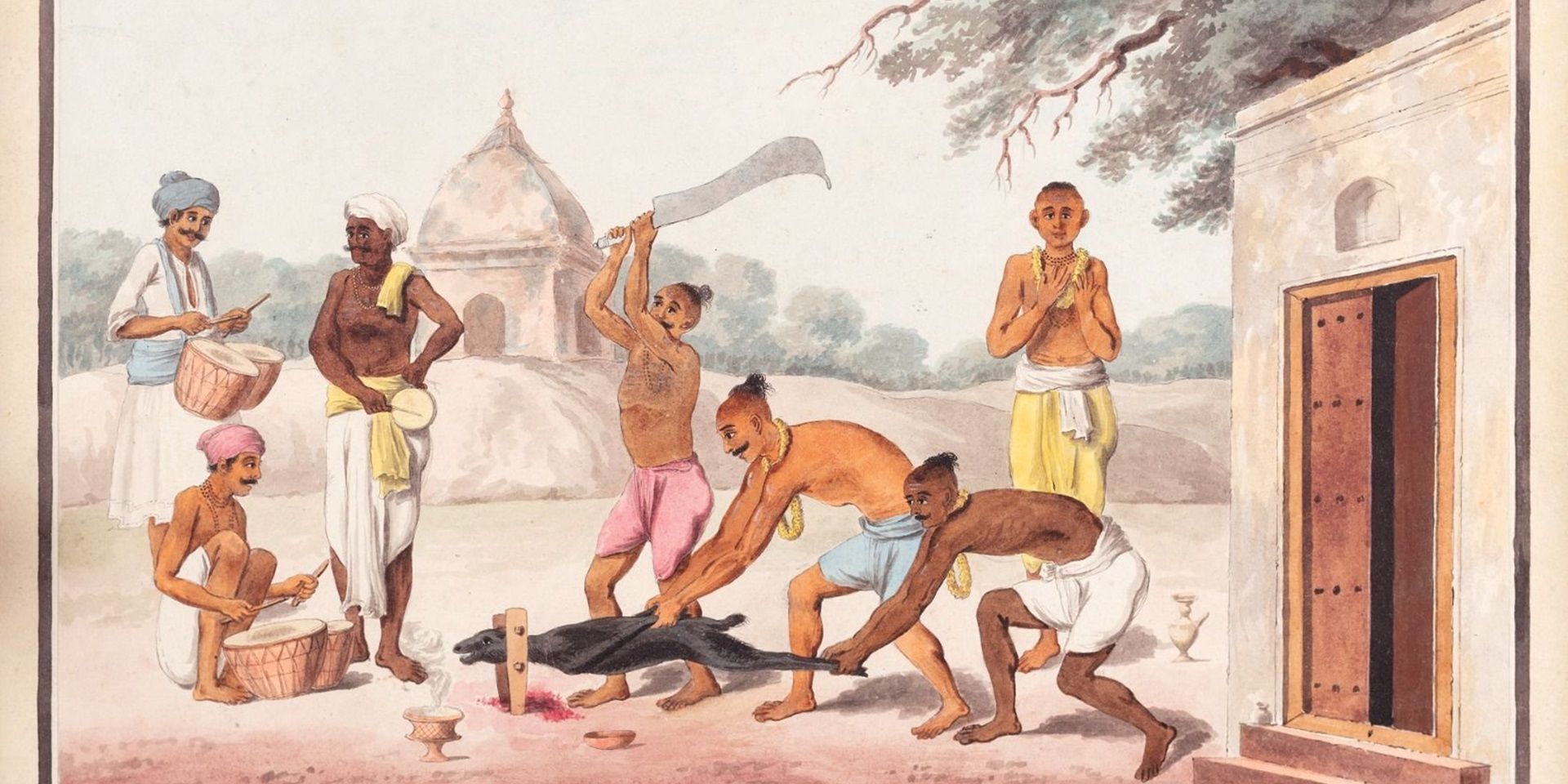

Sen: Natural dyes and pigments derived from the earth like yellow ochre have been used for ages to decorate walls and during rituals and festivities in the humblest of households in the rural areas of Bengal and elsewhere. When Rabindranath appointed Sukumari Devi as a teacher at Kala Bhavan in 1924, alpona and embroidery, socially considered to be pursuits more suited to women, were formally made a part of the curriculum as distinctive art forms alongside other ‘fine’ art techniques. While staying at the nichu bangla bari (low bungalow) with Dwijendranath Tagore’s daughter-in-law Hemlata Devi, Sukumari Devi had woven an exquisite shawl for Dinendranath Tagore. Rabindranath, on seeing the work, immediately realised the artistic prowess of the person behind the work of art and upon finding out about Sukumari Devi, he brought her to Kala Bhavan. She would train under the tutelage of Nandalal while also teaching design. Alpona had mostly remained an informal artistic practice to be pursued and taught within domestic confines by women. Mukul Dey and Rani Chanda’s mother Purnashashi Devi was an expert alpona artist and used to make beautiful stone moulds. As was wont in those days, this repertoire of decorative art had passed down quite informally from mother to daughter, and Rani Chanda, like Chitranibha, became adept at the art of alpona-making from a young age.

|

Students at Santiniketan working on an alpona design. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Some time after the arrival of Sukumari Devi at Kala Bhavana, Anukana Khastagir came for a year, followed closely by Indusudha Ghosh. Three years later, Anukana returned to continue her training under Nandalal after completing her undergraduate degree, then came Chitranibha, Rani Chanda, and eventually Nandalal’s daughters Gauri Bhanja and, later, Jamuna Sen, who also enrolled at Kala Bhavan . Gauri Bhanja would later assume the role of a pedagogue of ‘oriental’ design at the crafts section, and Jamuna Sen was also instrumental in initiating and reviving groups which trained women of Santiniketan in mastering batik, weaving, embroidery, etc. If we check the records at Visva-Bharati, it seems that women had started joining art courses as students from 1922.

|

Jamuna Sen working on an alpona design. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Abanindranath Tagore's portrait of Jamuna Bose (later, Sen) at age 14. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Kironbala Sen, another early student of Sukumari Debi, Asit K. Haldar and later, Nandalal, was a talented sculptor. In her memoirs, Amita Sen sketches an endearing image of the atmosphere of mutual appreciation and encouragemnet at Kala Bhavan in its early days. She recounts that once Kironbala had sculpted a figure of a mother carrying a child on her hip, and Abanindranath was so taken with the work that he had it cast in bronze.

|

Asit Kumar Haldar, Abokash, Watercolour on cardboard, 18.0 x 12.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Around this time Rabindranath decided to send some students, mostly women, to nearby villages and localities around Visva-Bharati to impart basic education to interested parties. The idea was to foster a spirit of kinship between the original inhabiants of the area and the members of Tagore’s institute. Women were taught improved methods of caring for animals, pregnant mothers, children, and basic hygiene among other things. In the Mukul Dey archives at Santiniketan, we find many such images of Visva-Bharati women riding out in bullock carts to meet the Santhal families. Creating these links between art, craft and everyday life was an organic aspect of pedagogy at Tagore’s world school, which would in turn inspire others to build upon the model in various ways. In this context it is worth mentioning that Indusudha Ghosh would teach briefly at Sriniketan (the production centre of leathercraft, weaving, pottery), on Nandalal Bose’s recommendation, before joining Baghbazar Nivedita School as an art educator. She was also the only woman to be a founding member of Karu Sangha (the artists’ cooperative) set up by Mastermoshai (Nandalal Bose) in 1929-30 along with a few of his students like Prabhatmohan Bandyopadhyay and Benode Behari, to promote the production and sale of various forms of craftwork.

A pen and ink wash work by Jamuna Sen. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Q: We observe some rare instances of self-portraiture by these early women artists of Bengal, like Sunayani Debi and Pratima Debi, in a bold assertion of selfhood in a society where most women were assumed to be facilitators rather than creators. In what ways do you think these Santiniketan artists were able to bring a fresh perspective in depicting themselves and the inner lives of women by occasionally going beyond the cliched imaginaries of mythical and classical themes they were encouraged to draw inspiration from?

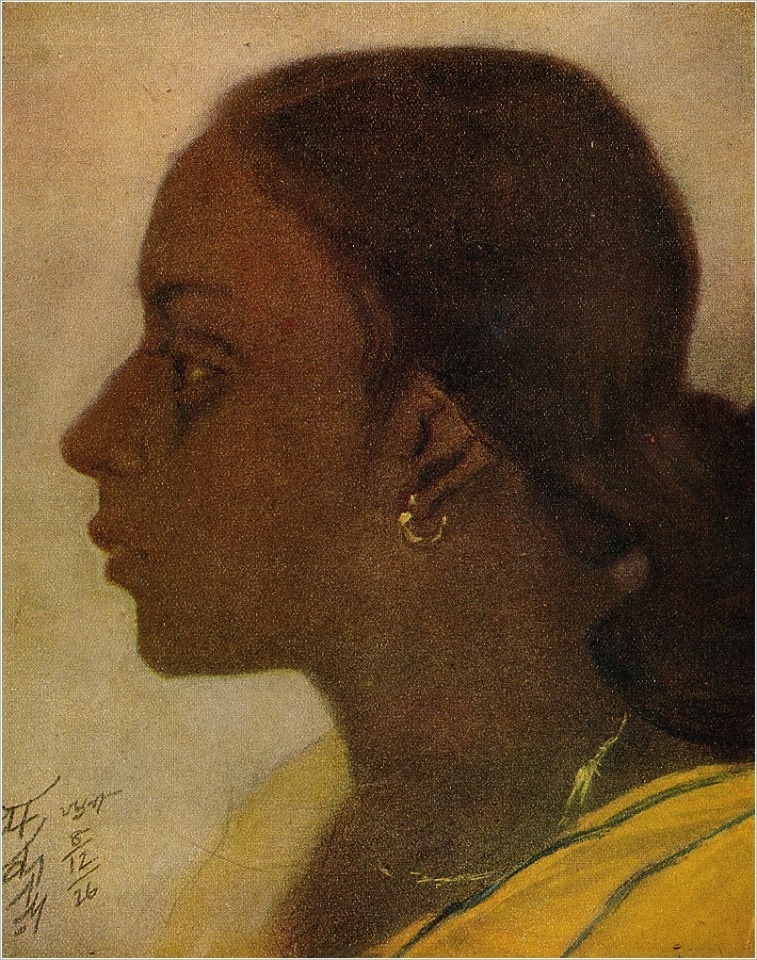

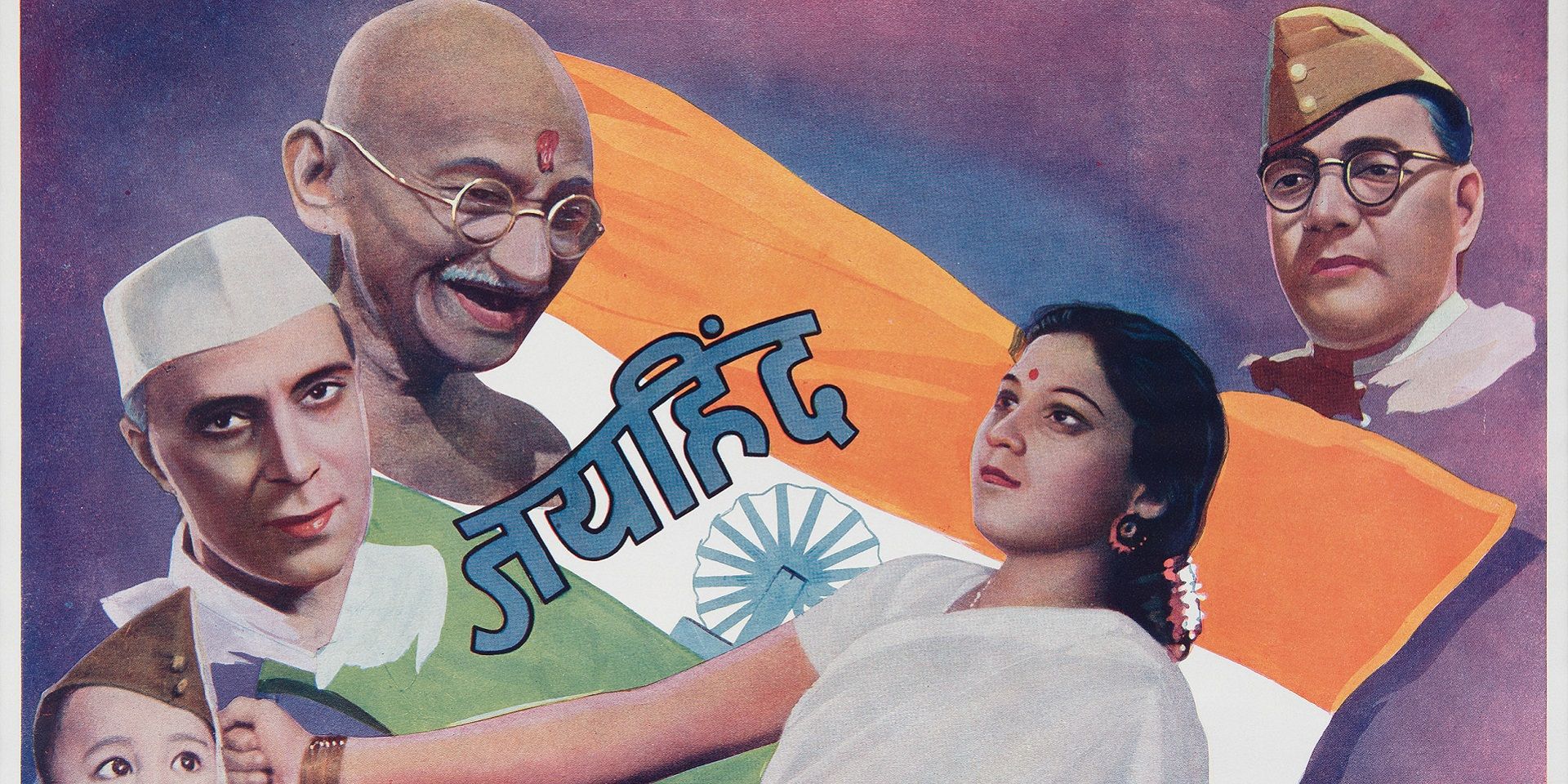

Sen: The very act of self-portraiture by artists like Sunayani Debi and Pratima Debi in a way break with tradition especially since during those early decades, women from upper/middle class families were mostly encouraged to remain housebound. Presenting a vision of oneself to the world was quite a modern assertion of identity as an individual artist beyond the confines of the gendered private sphere. However given the social limitations, these portraits were conventionally different from Amrita Sher-Gil’s bold defiance of norms by painting herself in the nude. Interestingly, Sunayani Devi, another early ‘primitivist’ alongside Sher-Gil (according to Partha Mitter’s reading of the development of modern art in India), also painted the portraits of women in purdah like Begum Meher Bano Khanam, the daughter of Sir Khwaja Ahsanullah, the third nawab of Dhaka.

|

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, Watercolour, ink and graphite on paper, 10.2 x 8.0 in., c. 1920s. Collection: DAG |

Artists like Chitranibha, Shanta Devi, Rani Chanda, have often creatively explored subjects like the everyday lives of women, and their unique perspectives have at times imparted a sort of interiority to the portrayal that resonates deeply with us today in going beyond traditional or mythical and romantic stereotypes. In one of her paintings Chitranibha imagines the life of a young housebound bride, gazing wistfully at the children playing in the grounds nearby. The writings and artworks of Sampurna Devi, an amateur artist and sister of the well-known writer Ashapurna Devi, are shot through with the silent revolt of a woman struggling under the chokehold of social expectations. Artists like Shanta Devi, whose works were in circulation to an extent, were able to pursue their passions while navigating the demands of a gendered private sphere precisely because of familial support and patronage. Although Sampurna and Ashapurna’s father, Harendranath Gupta was a Government Art School trained artist, it does not seem likely that he had taken much interest in imparting any sort of artistic knowledge to his daughters. Some of Sampurna’s works have survived the ravages of time and familial opposition, and the titles and themes she chose for each of her canvases speak to a sort of confessional mode of creation that we have witnessed in so many early women artists and poets across countries and ages.

|

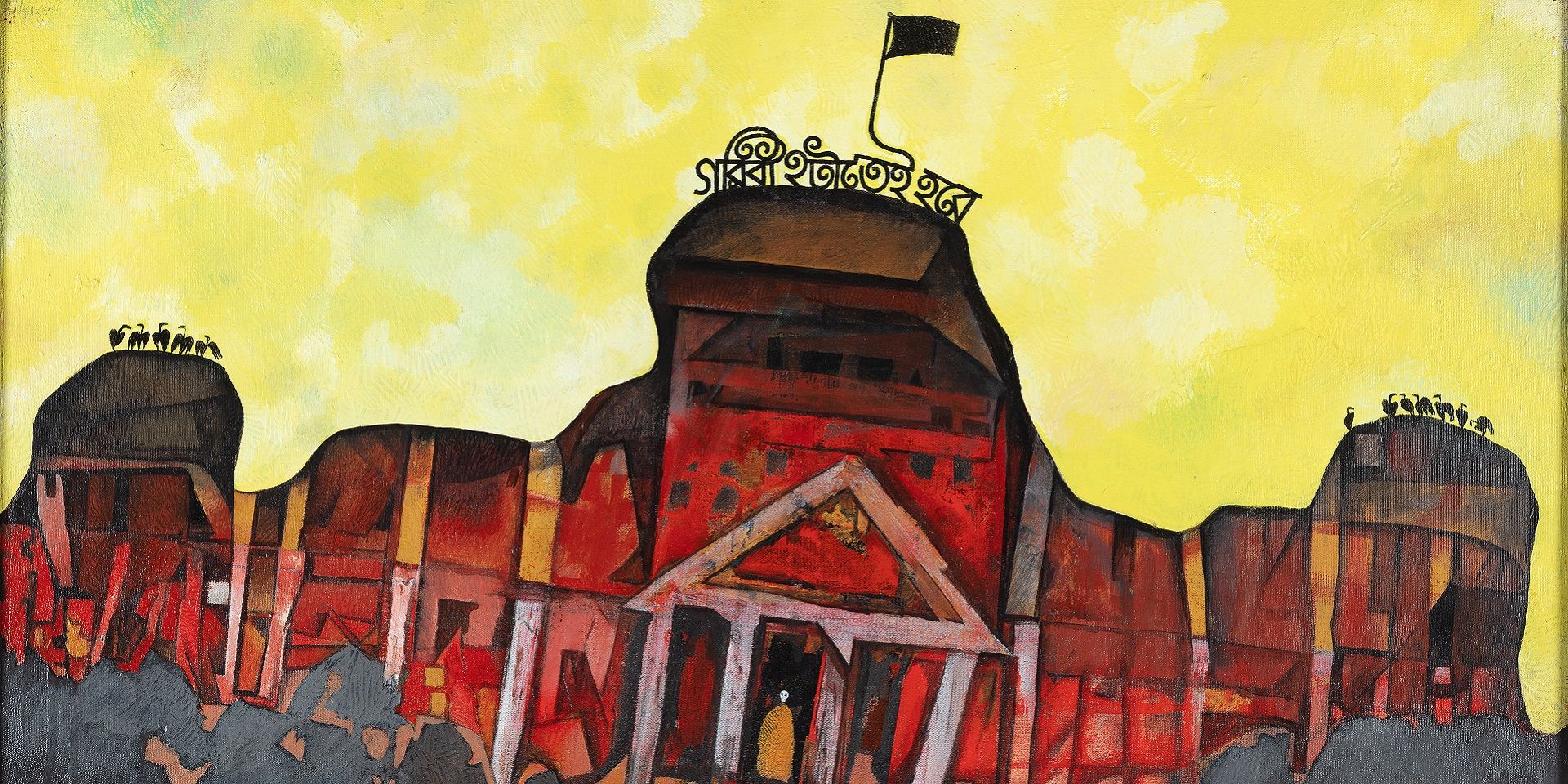

Rani Dey, Untitled, Woodcut on newsprint paper, 8.5 x 6.0 in., 1938. Collection: DAG |

Q. Some of the artists you discuss in Abanindra Parampara, like Kshitindranath Majumder, Samarendranath Gupta, Asit Kumar Haldar, Prosanto Roy, who later spread out to various art schools in Lahore, Lucknow, Jaipur, Madras, etc., often tutored women at home. What role do you think these networks of tutelage played in extending the reach of art education beyond institutional walls?

Sen: As we know, during the 1920s formal art education was not available to women at government art colleges, which were the major sites of colonial art instruction. It is only much later that women like Maitreyi Bandopadhyay, Karuna Saha, Uma Siddhant, etc., get enrolled in the Government College of Art and Craft in Calcutta, and women students gradully begin to join the newly openend art departments at other institutes. Among the first students of Abanindranath, Nandalal Bose had the opportunity to train the early batches of women students at Santiniketan. There exist numerous memoirs by his students, like Anukana Khastagir, Chitranibha, Rani Chanda, among others, who write about his spontaneous methods of teaching and warm personality.

Asit Kumar Halder informally guided and encouraged his daughter Atasi to pursue art, but she was largely self-taught and learnt by observing her father.

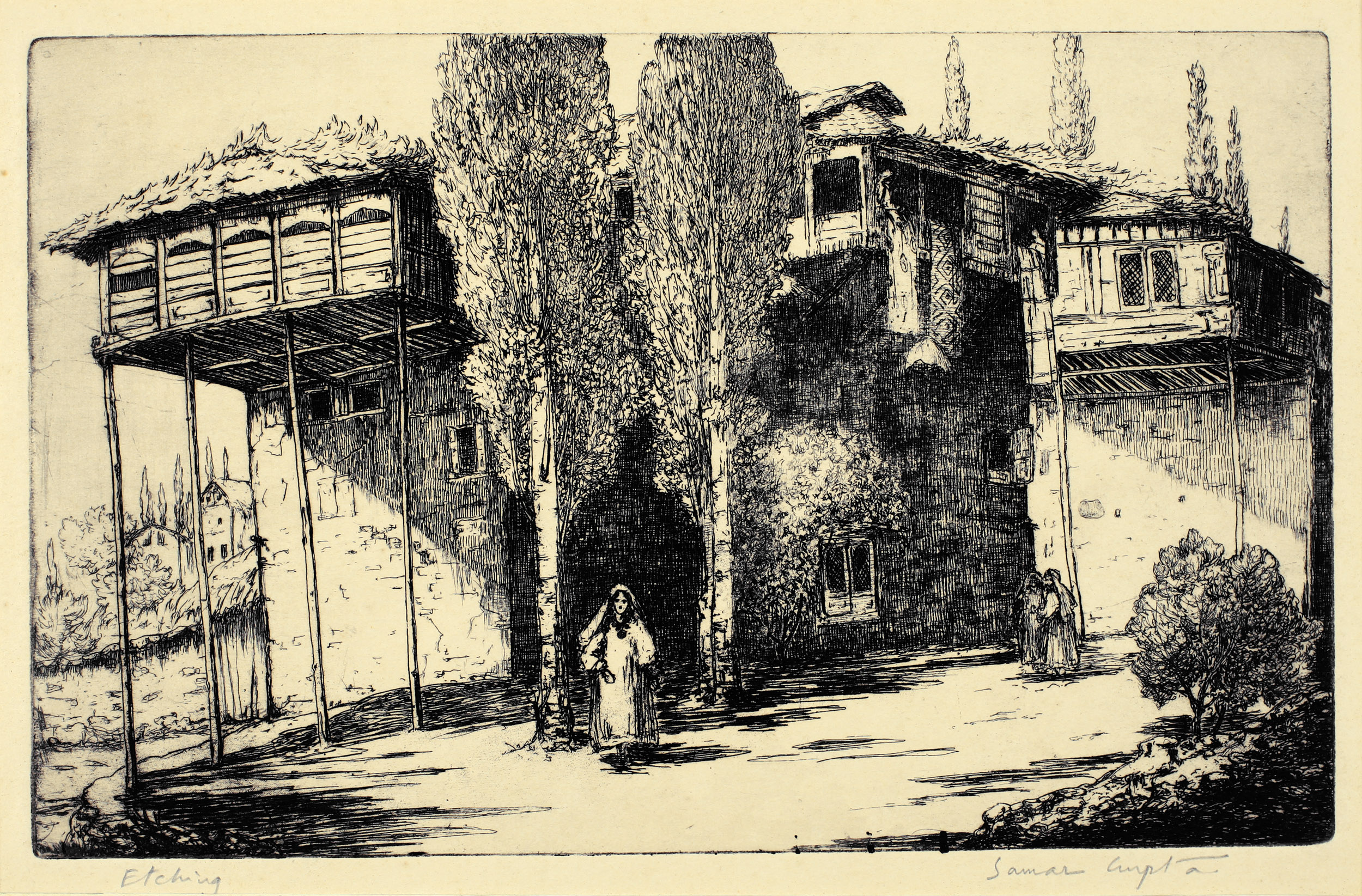

Atasi Halder (Barua) did not study Fine Arts but went on to do distinctive work professionally, what artists call ‘ajura’ work. During the 1950s, when her works on the life of Buddha were gaining increasing popularity, Atasi received a commission to make a series of sketches on the life of the twenty-third Tirthankara, Parshvanath, for Calcutta’s Digambar Jain temple. Besides following her father and other Bengal School artists in developing her style, Atasi also made caricaturish works in the vein of Kalighat patuas, like one which features two women fighting in the kitchen and pulling each other by the hair while the bloodied dismembered fish lies flopped on the floor! Another of Abanindranath’s pupils, K. Venkatappa also taught Lokasunadari Raman, Sir C. V. Raman’s wife. While he was at Lahore, Samarendranath Gupta, taught Shareefa Hamida Ali, the daughter of the great connnoiseur of the arts Nawab Hamid Ali Khan of Rampur.

|

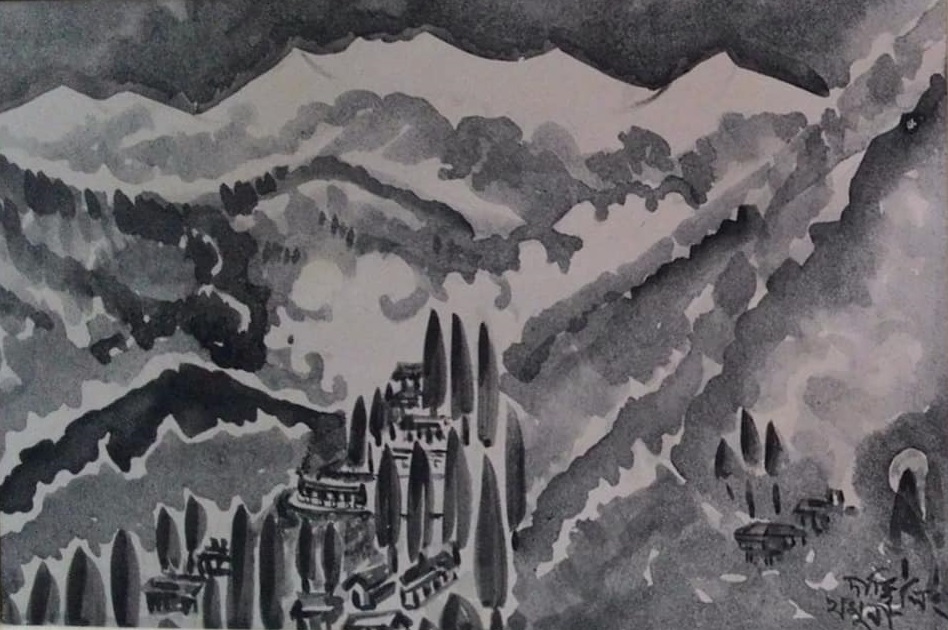

Samarendranath Gupta, Untitled, 6.7 x 10.7 in. Collection: DAG |

An artist who preferred practising in private, Prosanto Roy was very well-known for his mastery of the wash technique and many students of Kala-Bhavan would just gather around him to observe while he painted. Very often, he would just tear up and cast away a painting that was not to his liking, and students would fight over collecting these discarded pieces during these informal impromptu sessions. Many of these works have been collected by Kala Bhavan students like Monimala Dev Burman, Jahanara Begum, Deepa Ray, and others.

Prosanto Roy, Mukti joddha, Watercolour on paper, 11.0 x 5.0 in. Collection: DAG

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025