Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

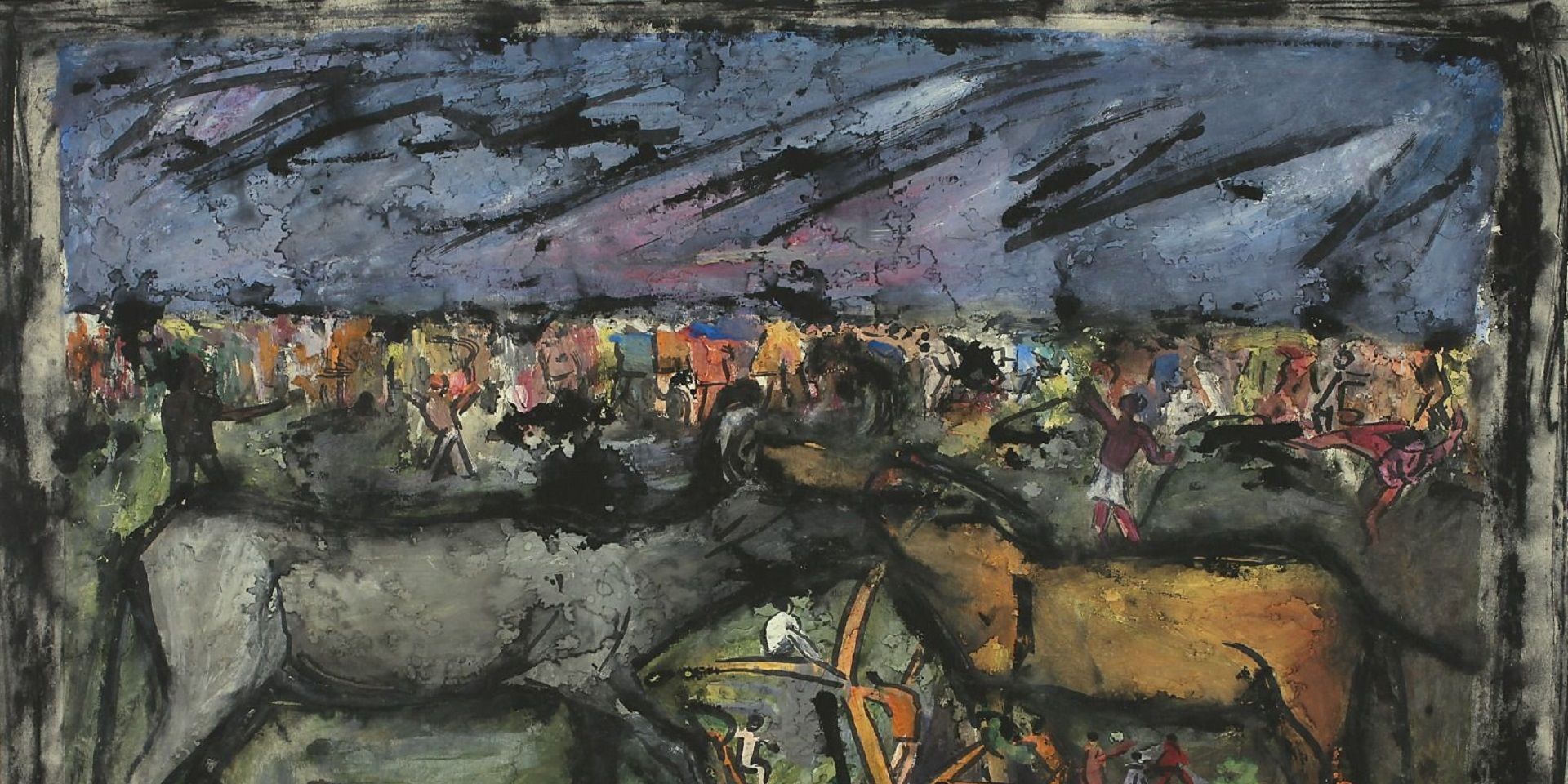

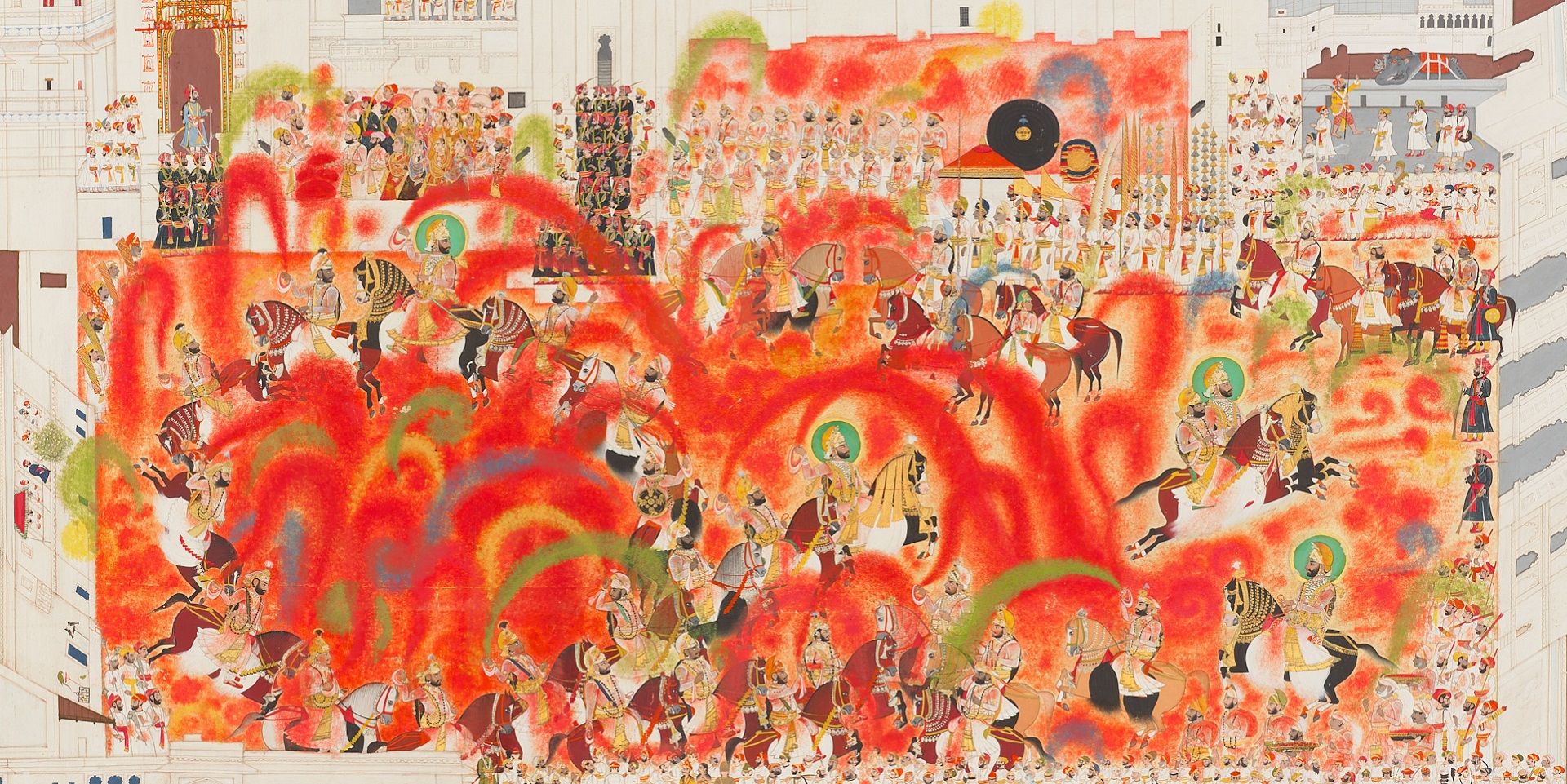

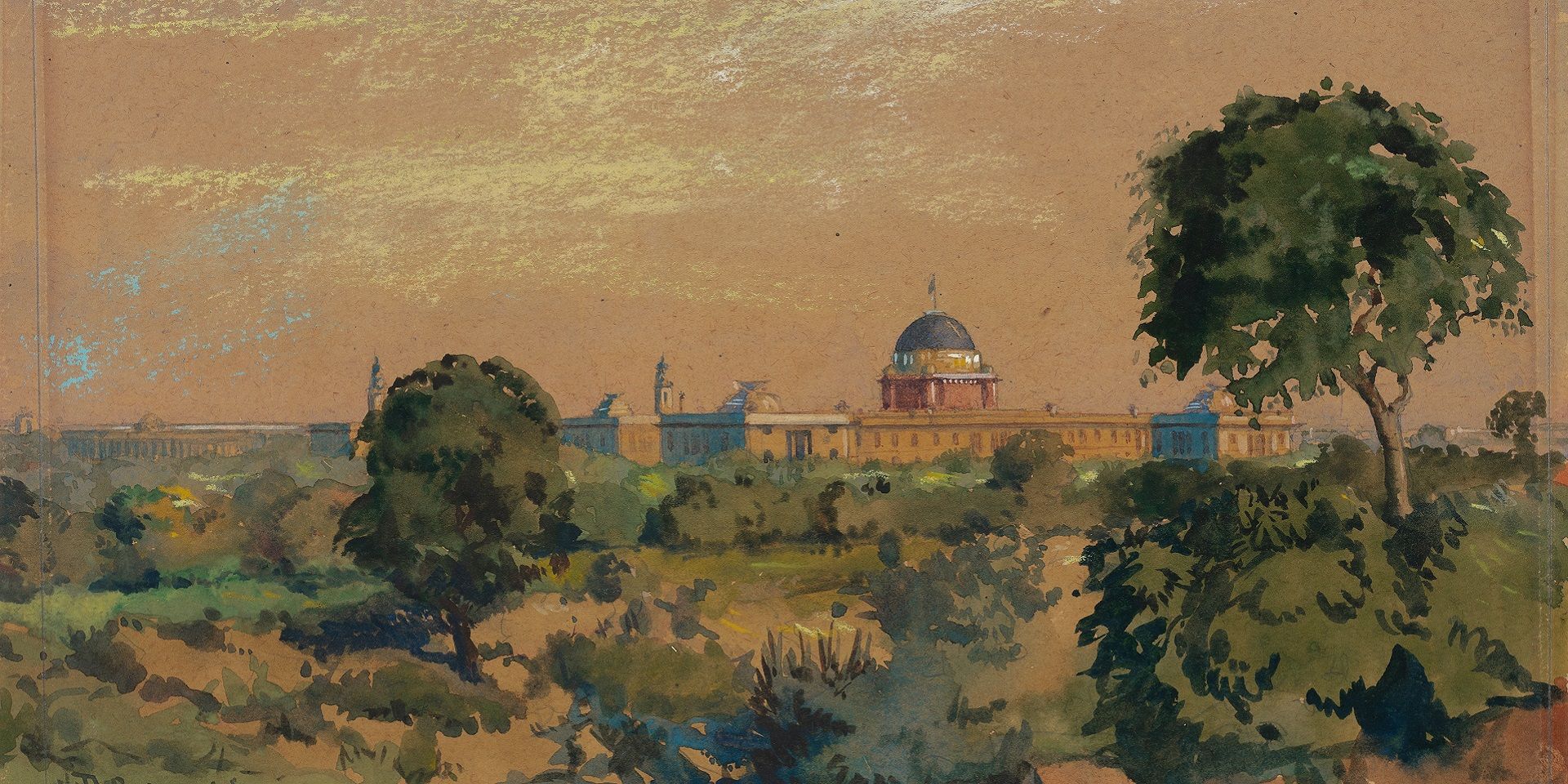

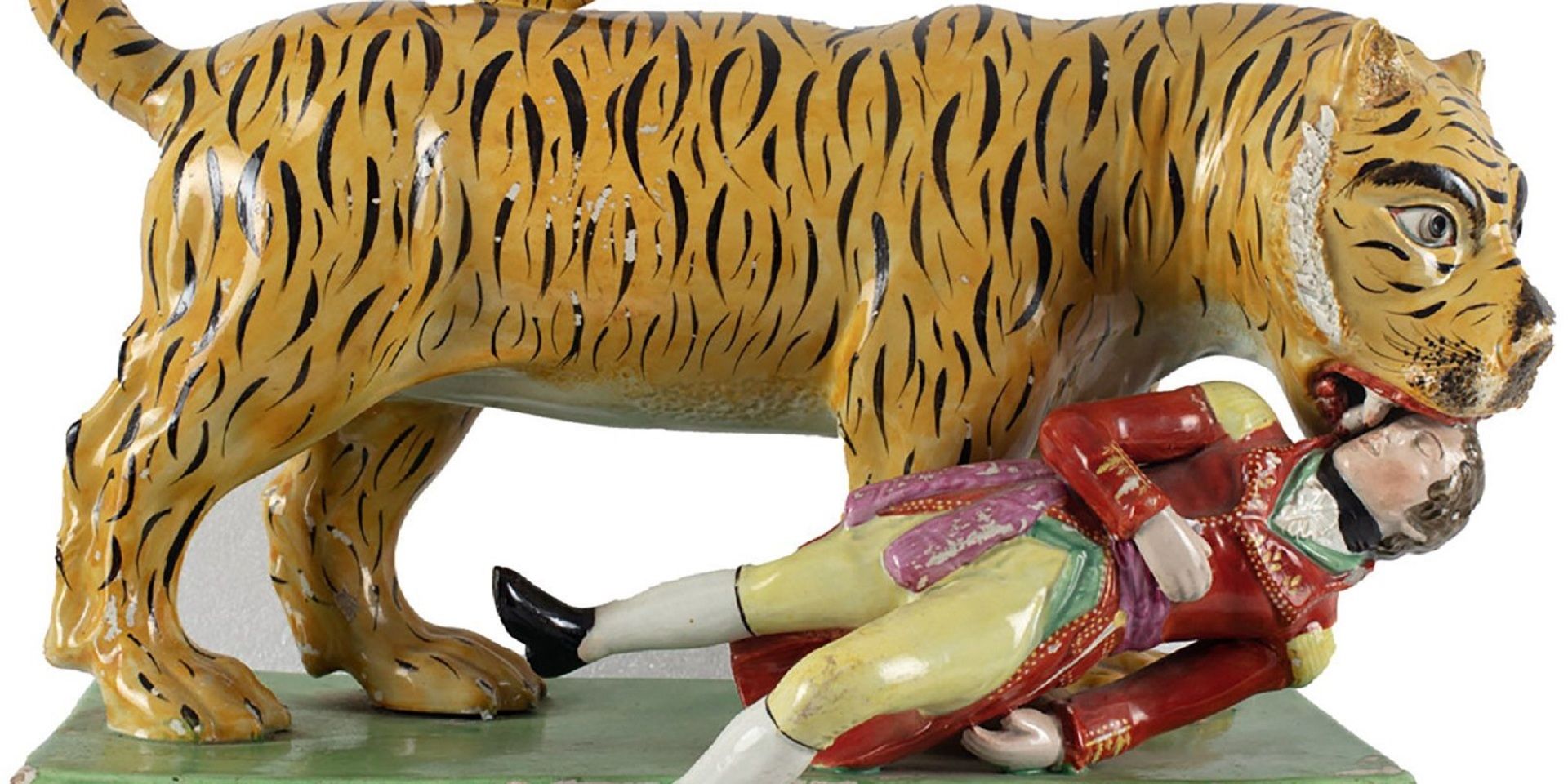

K. H. Ara, Untitled (detail), Watercolour and gouache on paper c. 1960s, 14.0 x 18.5 in. Collection: DAG

Reema Desai Gehi's book The Catalyst: Rudolf von Leyden and India’s Artistic Awakening explores the life of one of the most influential champions of Indian modern art, especially those belonging to Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group. She spoke to the editor of the DAG Journal on her own journey, prodded partially by the artist Krishen Khanna, into the world of European émigrés like von Leyden, who transformed our reception of and expectations from modern Indian artists in the post-independence era.

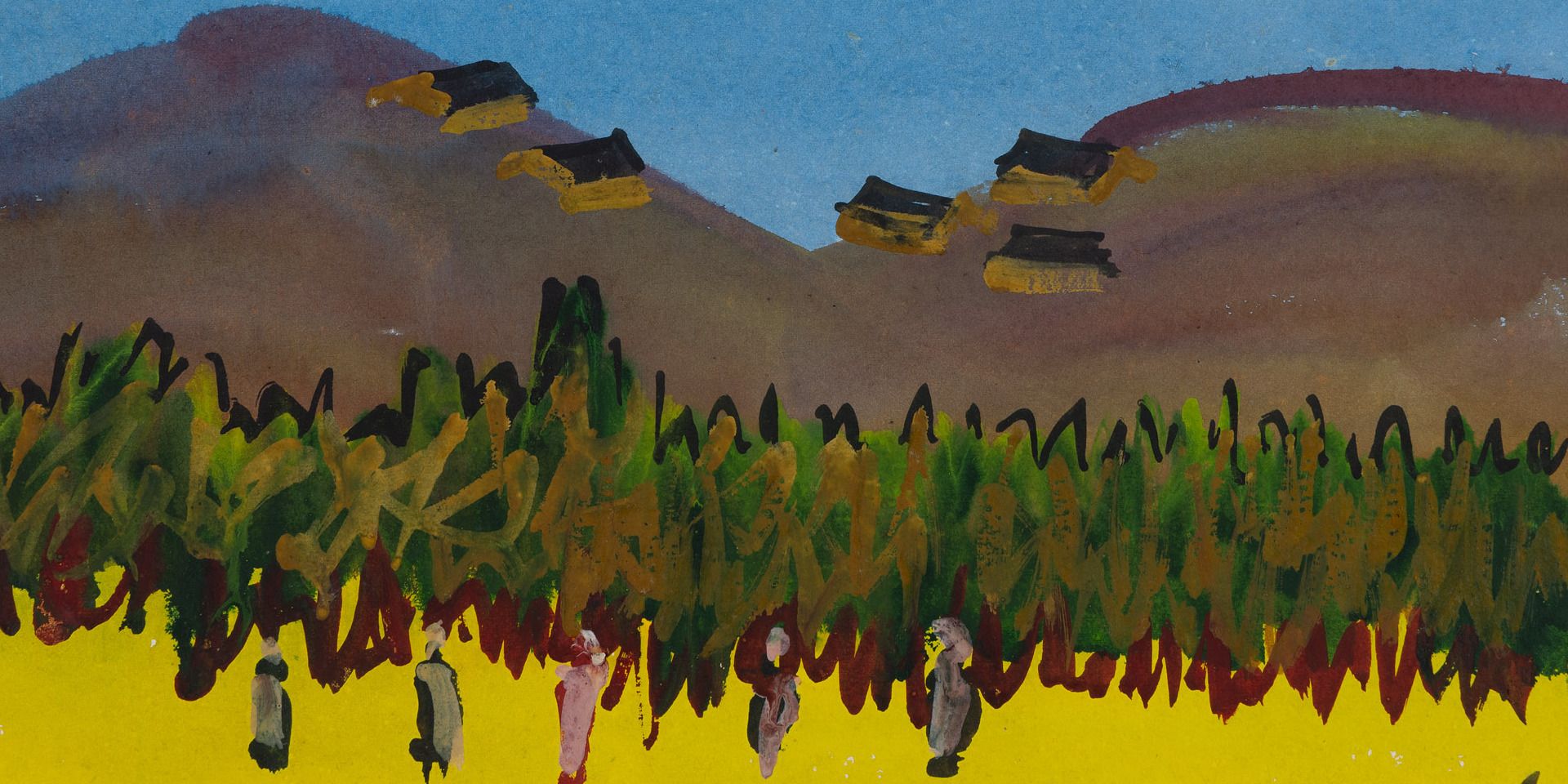

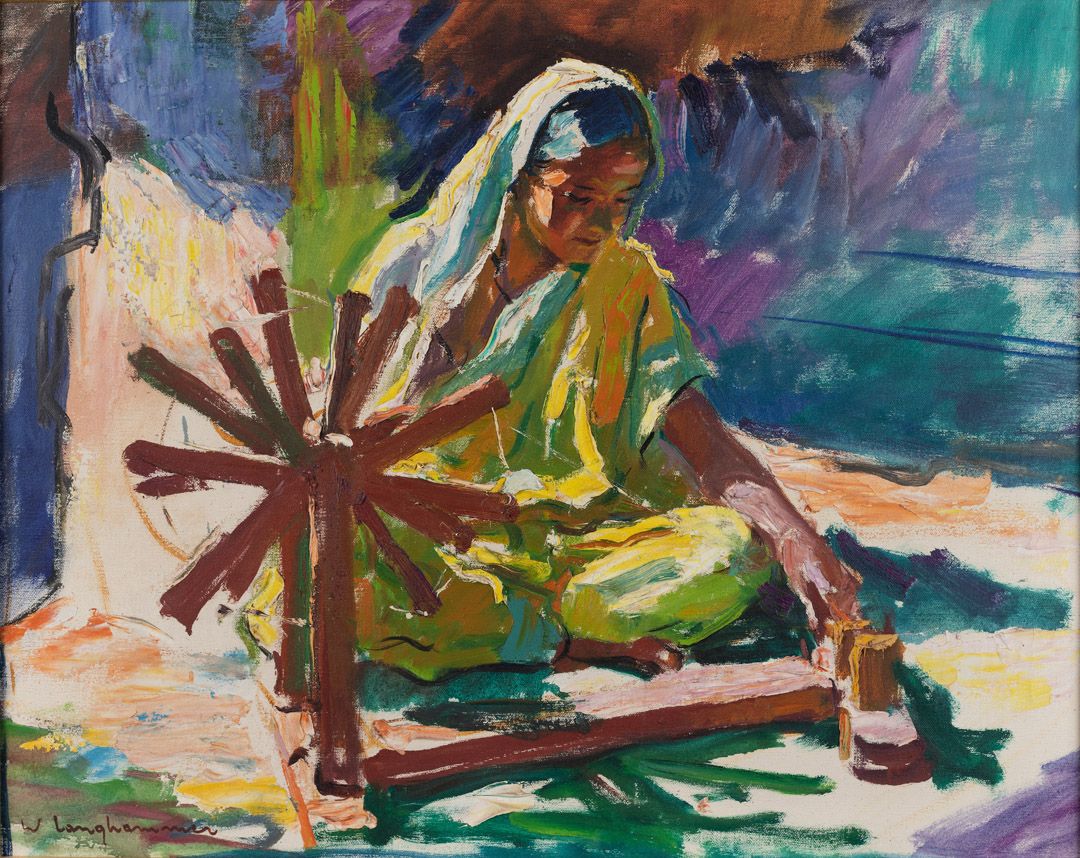

Walter Langhammer, Untitled, Oil on hardboard, 8.7 x 17.7 in. Collection: DAG

Q. What was the context that enabled European émigrés like Rudolf von Leyden, Walter Langhammer and others to become a part of Bombay’s artistic community in the 1940s? Why did they choose to move to Bombay?

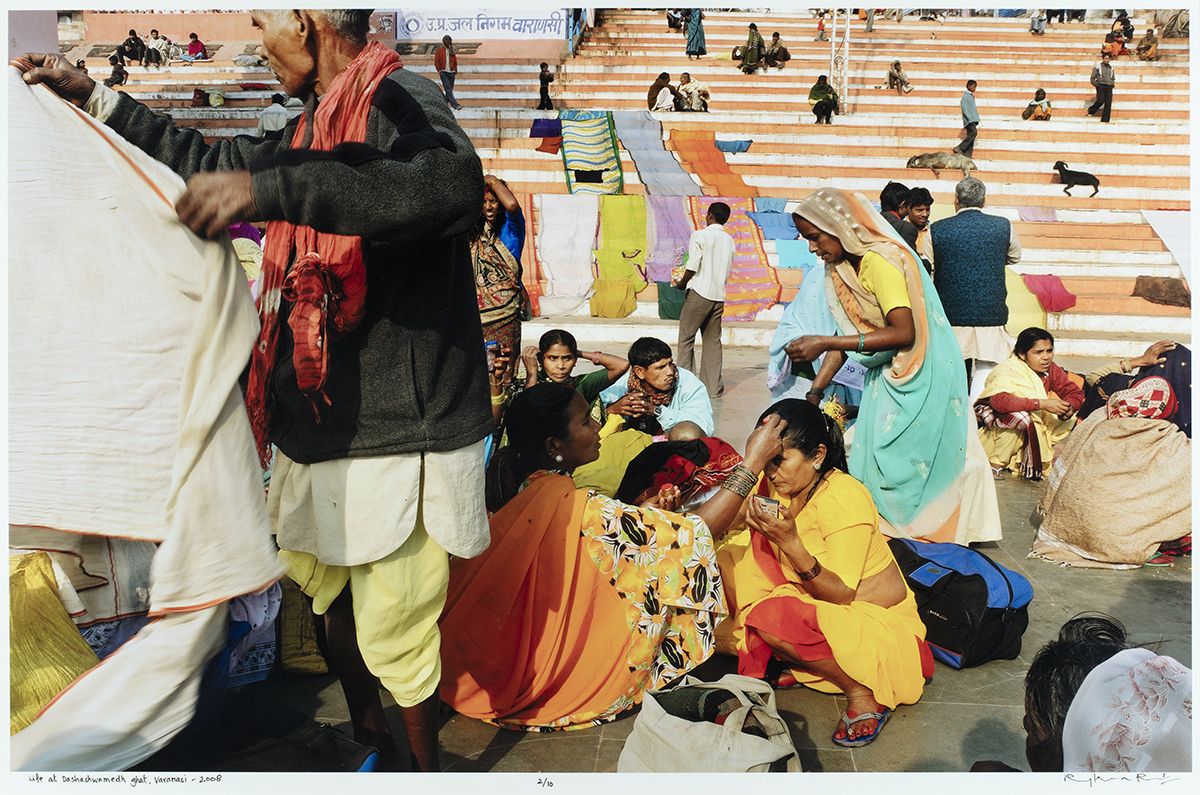

Reema Desai: Rudi arrived in Bombay because his brother Albrecht had preceded him by six years. He had come to establish a European company named IG Farben in 1927. Meanwhile, Rudi, who was 25 years old in 1933, had Jewish heritage. He held Communist sympathies as well. Given the perilous conditions for individuals like him in Germany during 1933, Rudi's life was at risk. Seeking refuge, he sought the guidance of his family, who advised him to spend six months with his brother until the situation stabilised back home. However, what was initially intended as a brief visit extended into a 35-year journey, initially by choice but ultimately by fate.

Langhammer moved to India owing to Austria's annexation in 1938. His connection to India stemmed from having a Parsi student named Siloo Vakil. This is mentioned in Jerry Pinto's book Citizen Gallery as well. Langhammer's wife, Kathe, being Jewish, compounded the perilous situation they faced in Austria. Urged by Siloo, they made the decision to move to Bombay, where she had already secured a job for him as the art director of The Times of India.

Emmanuel Schlesinger was on his way to Shanghai, when he thought of stopping over at Bombay. My reading suggests that it was his long-standing fascination with India, particularly Bombay, that led him to pause there. Eventually, he opted to extend his stay. For Langhammer and von Leyden, Bombay was their intended destination, whereas for some others it was more a matter of chance.

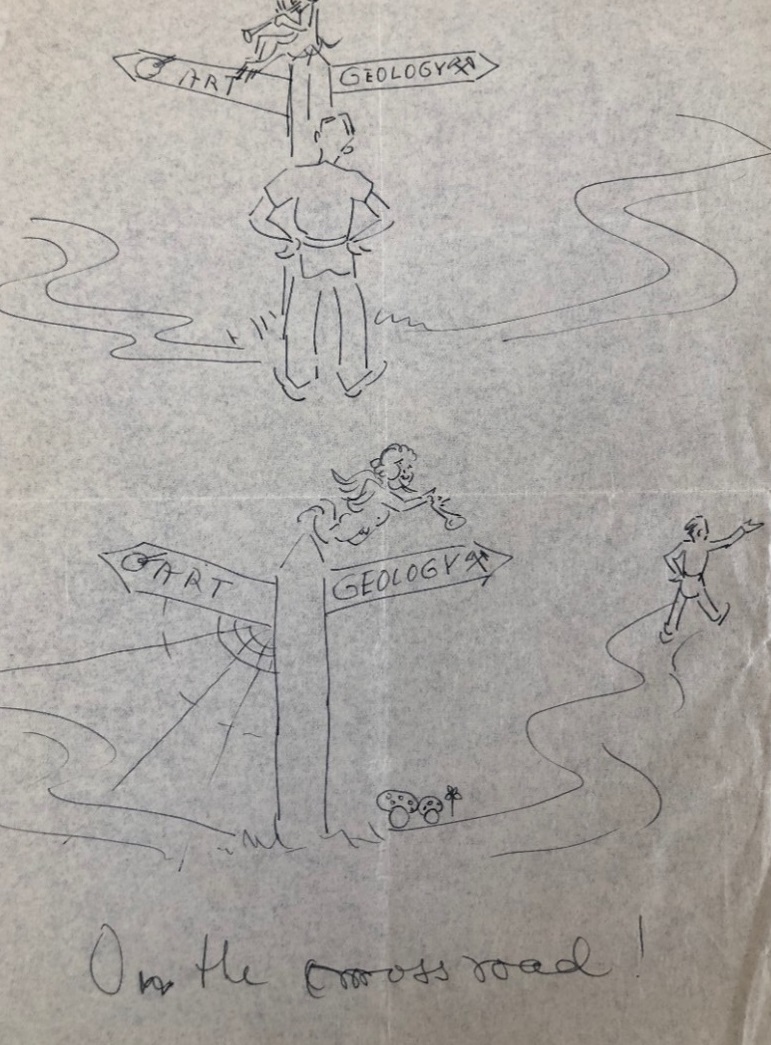

Q. Rudi started off as a trained geologist, but ultimately turned to making sketches and writing art criticism. You captured his period of doubt/ soul-searching very well, with the help of a sketch that he made showing himself at a crossroads in his life. How do you see this period of uncertainty in his life informing his choices? What impact did it have on his personality?

Reema: Imagine you're 25, having invested a solid decade studying a subject, ultimately earning a Ph.D. Naturally, you would expect to pursue a career aligned with your expertise, right? Yet, life had different plans. Landing in Bombay, the prospect of finding work as a geologist seemed bleak. Attempts to secure a job in South Africa, as hinted in his letters, proved futile. Relying solely on his brother's generosity wasn't sustainable. So, he tapped into his modest talent in art, making drawings, designing menus, greeting cards, and advertisements. He later established a small studio, formalising his artistic endeavours. As uncertainty loomed back home, he chose to stay on. Then, as if fate had intended it, he attended an art show, from which he returned brimming with enthusiasm. His impromptu review caught the attention of Simon Pereira from The Evening News of India. Taken by his passion, Simon offered him a reviewing opportunity. It wasn't so much that he found art; rather, art found him. Thus began a journey where seemingly disparate pieces fell into place, something one can only realise in hindsight. After all, life's puzzles often make sense only in retrospect, not as they unfold.

|

Sketch by Rudolf von Leyden, portraying his life at a crossroads. Image courtesy: Reema Desai Gehi |

Looking back, he came to understand why he opted for Bombay instead of Berlin as his home. Similarly, he also saw why he chose art over geology as his career, perhaps. Art remained an integral part of him, enduring even beyond his formal tenure as an art critic for The Times of India. Despite ascending to prominent roles at Voltas—initially Volkart Brothers—he remained engaged with the artistic community, assuming the mantle of a leading authority on ganjifa cards worldwide. For Rudi, art was a constant presence, woven into the fabric of his being.

|

Mughal ganjifa playing cards. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

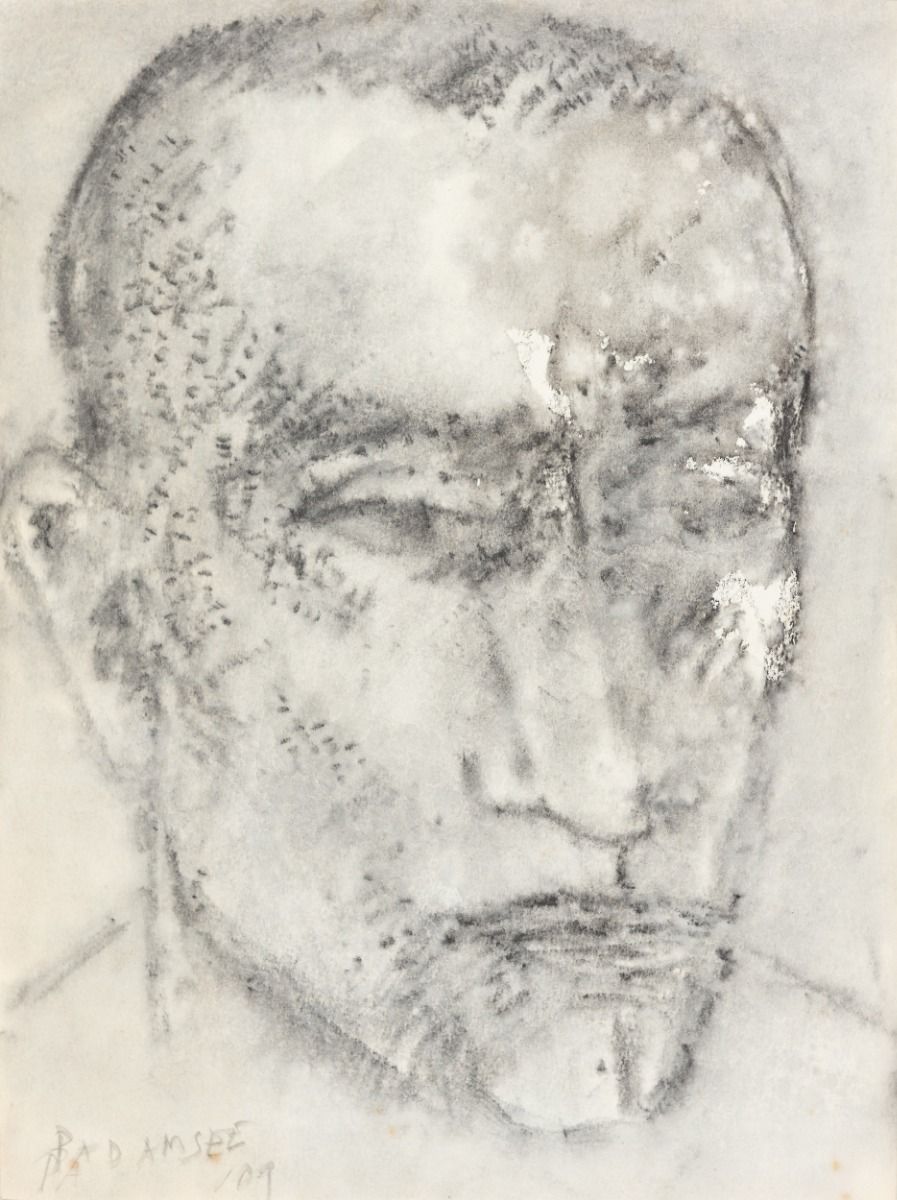

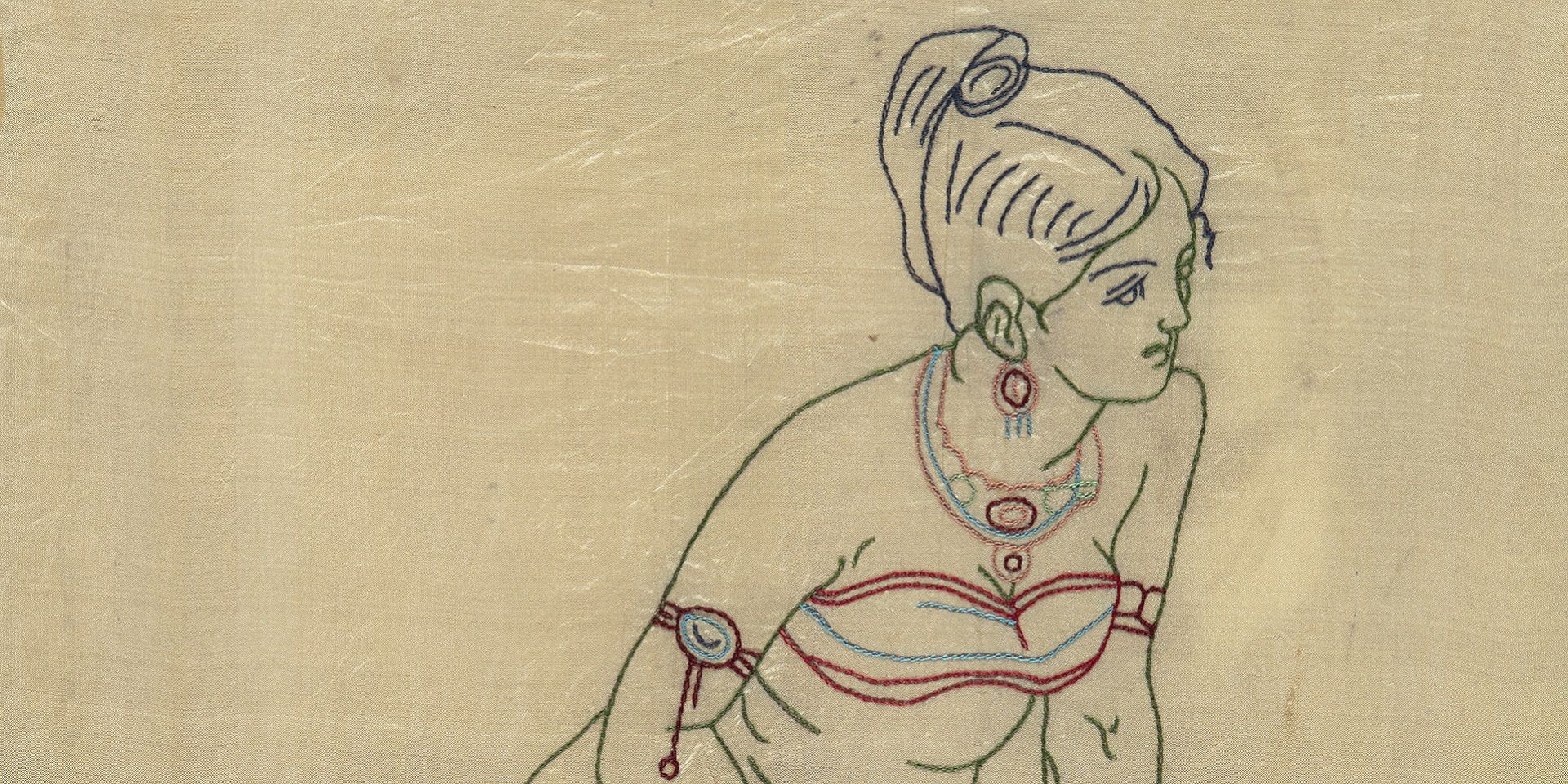

Q. He had complex lifelong relationships with artists like K. H. Ara, S. H. Raza and Krishen Khanna, among many others of course. How do you see the dynamic of power shifting between himself and his Indian artist friends whom he also promoted through is writings and endorsements? Akbar Padamsee is another artist he helped early in his career with a case of censorship. What were his ideological convictions that led him to support these artists?

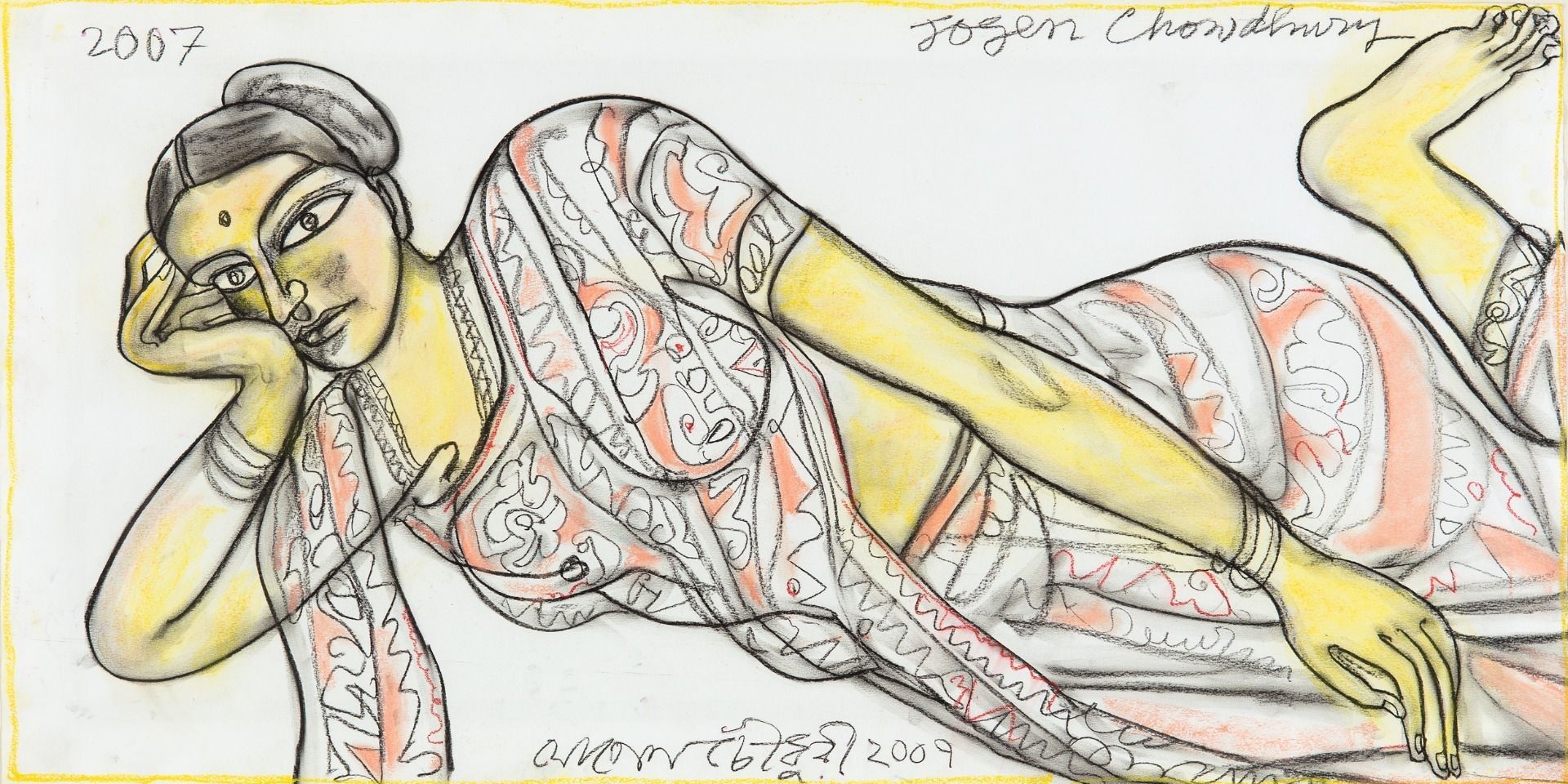

Reema: I believe it was a blend of instinct and ideology that guided Rudi's actions. Each relationship he formed, like the one he did with Ara, was unique. It's unclear whether Rudi was primarily touched by Ara's artistry or his challenging circumstances. While there's little documentation on this, accounts from individuals like Katy Soonawala, Eleonore Chowdhury-Haberl, and Marie-Louise von Leyden, Rudi's niece whom I spoke with in 2018, shed light on his motivations. Regardless of what initially moved him, it's evident that Rudi was determined to elevate Ara from his struggles. He envisioned a life for Ara beyond washing cars, aspiring for him to thrive as an artist. This unwavering support forged a deep bond between them, leaving Ara forever grateful to Rudi.

|

K. H. Ara, Untitled, Watercolour and gouache on paper c. 1960s, 14.0 x 18.5 in. Collection: DAG |

The dynamic between Rudi and Ara was distinct. As Krishen Khanna put it beautifully in one of our interviews: while Ara seemed to maintain a certain distance from Rudi, the latter remained consistently open and welcoming. Even as Ara's stature grew, with successful exhibitions and travels such as his trip to Europe in 1962, Rudi remained ‘Rudi sahab’ to him, a testament to their enduring relationship.

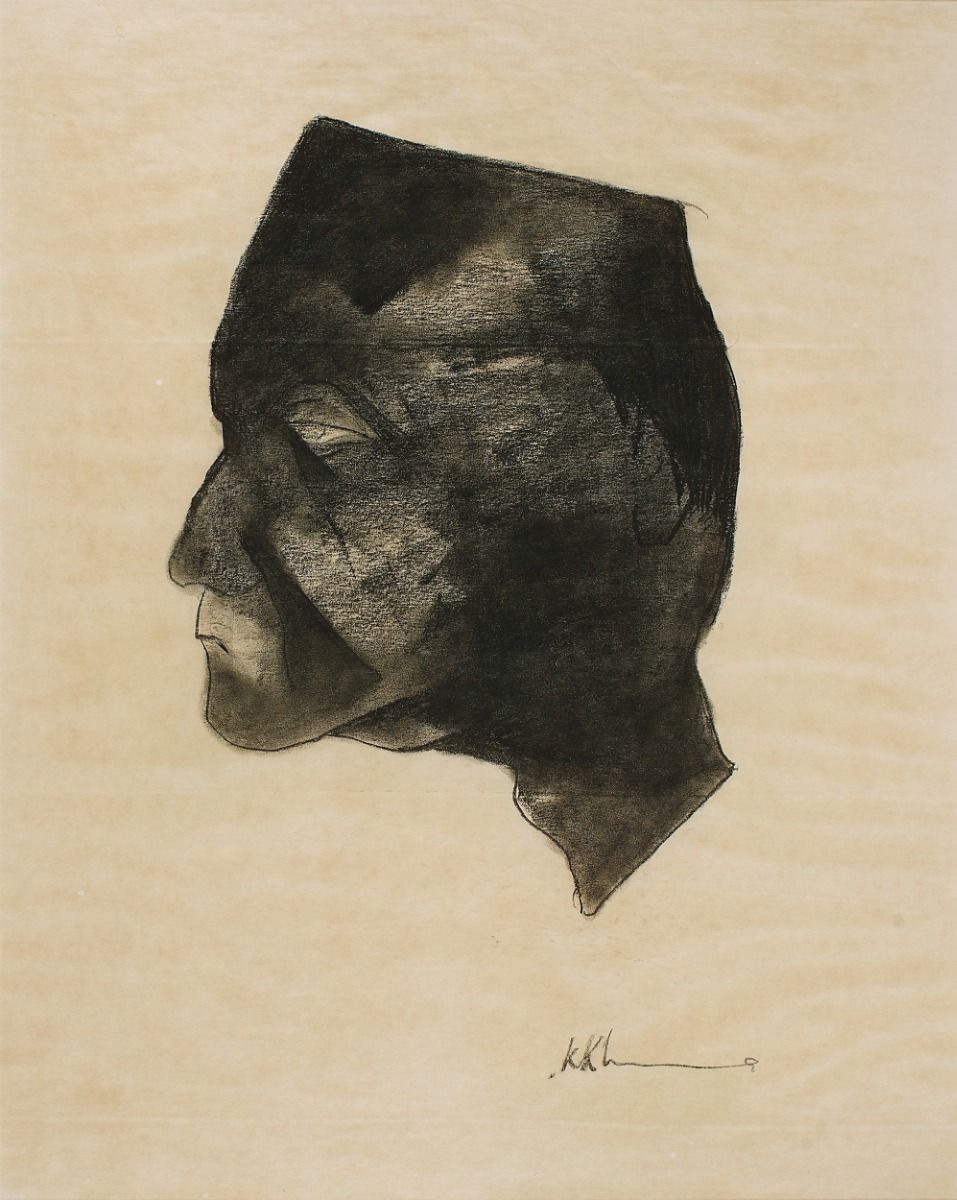

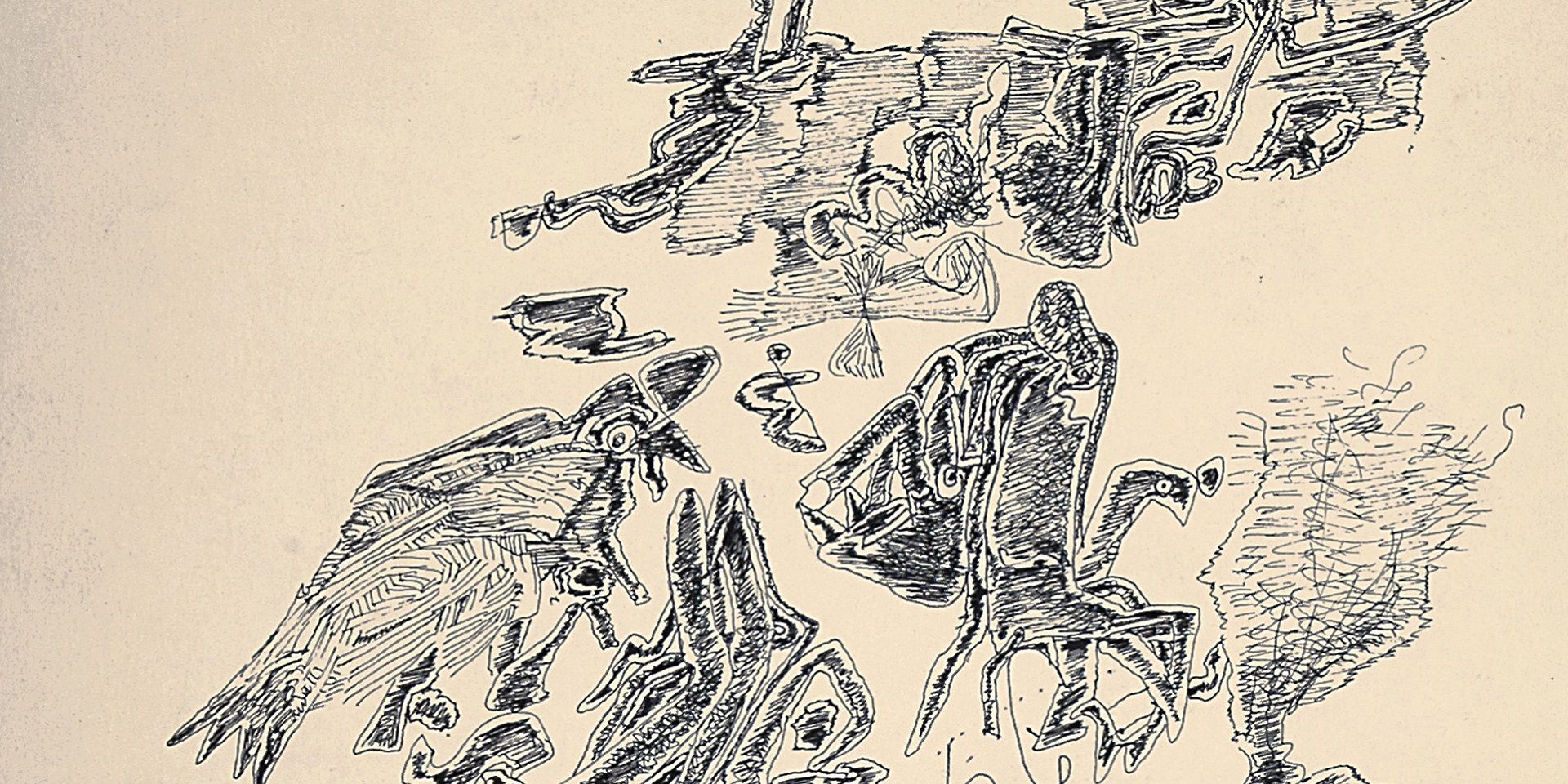

Raza also felt indebted to Rudi, yet their paths diverged when Rudi returned to Vienna after 35 years in Bombay, while Raza moved to France. Despite the physical distance, Raza and Rudi maintained a familial bond, marked by significant time spent reconnecting. On the other hand, Krishen Khanna, who was educated in England and possessed a strong command over the English language, held his own ground in his friendship with Rudi. Khanna's eloquence, knowledge of poetry, and philosophical depth placed him on an equal footing with Rudi, devoid of any perceived indebtedness. However, it's essential to contextualise their relationships within the era in which they lived. Post-independent India grappled with various complexes, wherein validation from a European figure like Rudi carried significant weight, particularly for individuals from humble backgrounds. This isn't to imply racism but rather a recognition of the lingering influence of colonialism. Even today, there's a subconscious inclination to seek validation from Western voices, a phenomenon that was at a height during the 1940s when British authority prevailed.

|

Krishen Khanna, Untitled, Charcoal on paper, 29.2 x 23.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Rudi was a collector of antiquities, and ganjifa cards famously, as well as modern art, especially from India. How do these different objects of collection inform his understanding of Indian art and why do you think his friends were skeptical about these collections?

Reema: When you're displaced and find a new place to call home, there's an inherent drive to delve deeper into its essence I think. Unlike when we view our birthplace, where familiarity can breed complacency, the adopted home spurs a continual quest for understanding. It's also a matter of time. As one spends more time in a city they've come to adopt, there's a gradual acceptance that it is indeed home, albeit as a foreigner. The process of making it truly one's own involves immersing oneself in its culture and people, gradually assimilating into its fabric.

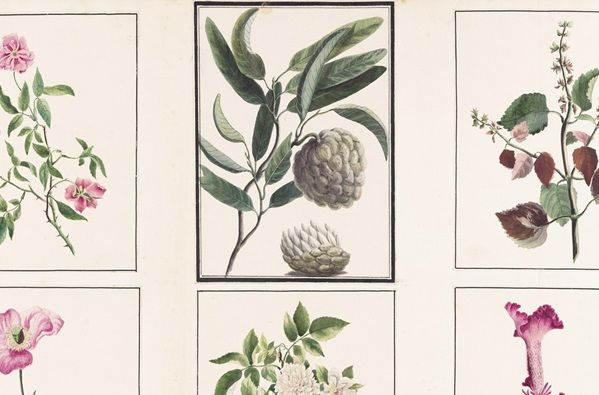

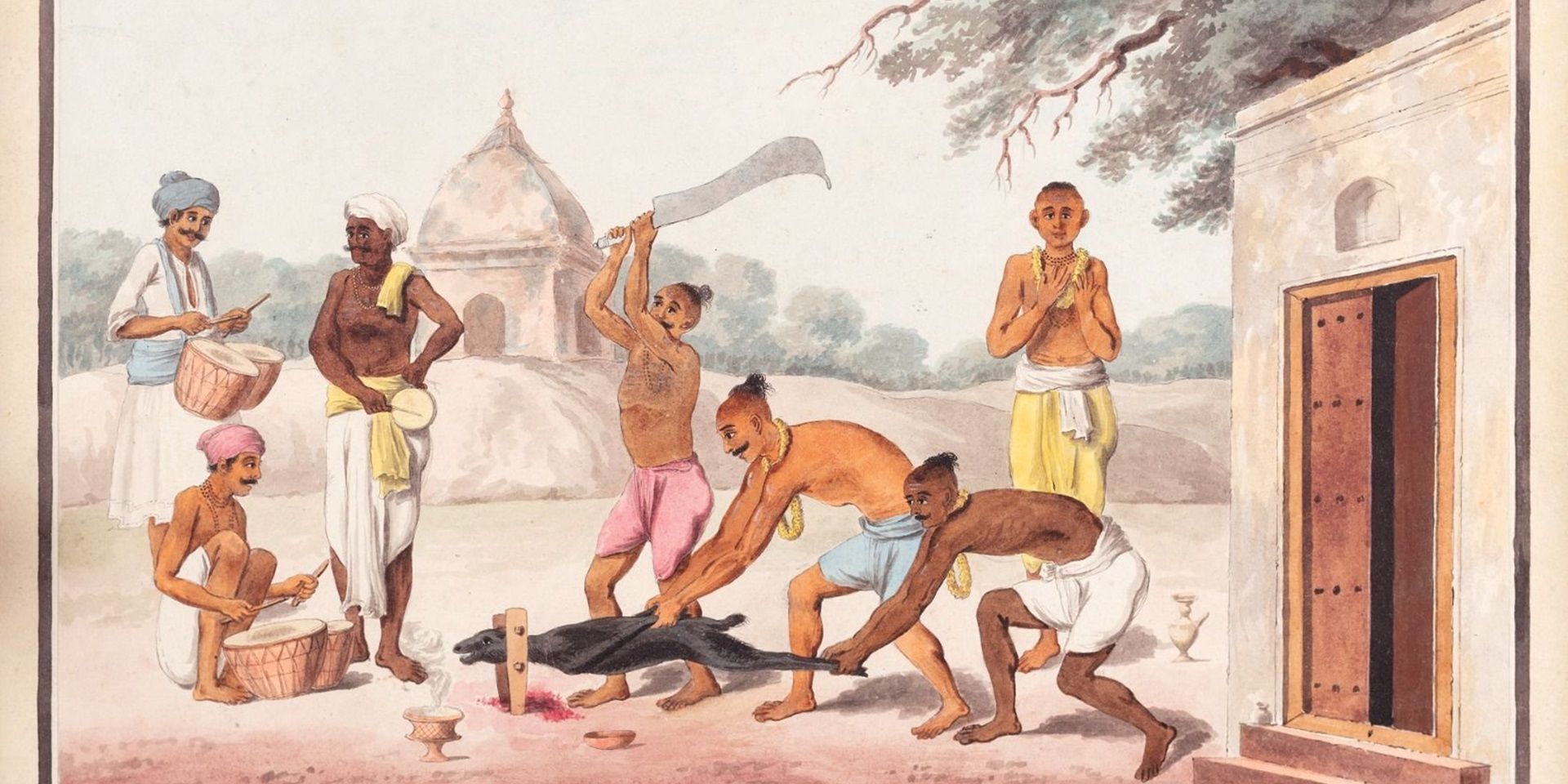

This fascination with carrying a piece of India wherever one goes isn't unique to Rudi; it's a sentiment shared by many foreigners who've made India their adopted home. As for Rudi's particular interest in Ganjifa cards, it remains somewhat enigmatic. Drawn to their aesthetic allure, he embarked on a deep exploration of these circular playing cards. Intricately designed and captivating in their beauty, I had the privilege of viewing them at the Deutsches Spielkartenmuseum, the German Playing Card Museum in Leinfelden-Echterdingen, where Rudi donated and sold much of his collection. What began as a mere fascination evolved into a lifelong pursuit, a testament to the enduring allure of these exquisite cards.

|

Akbar Padamsee, Untitled, Charcoal and ink on paper, 2009, 14.2 x 10.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Rudi wrote about creating ‘a common platform for envisaging a world history of art’. How far do you think he was successful in transforming Indian taste for a more assimilated global modernist style that followed international influences? Do you see that as one of his major aims – to also globalize the taste for Indian art?

Reema: You know, Krishen Khanna made a point that sticks with me: even though we might want to believe our art was purely Indian Modernism, it was still seen through European eyes. This was back before Google, when people like Langhammer and Leyden, both foreigners, were plugged into European art scenes. They had access to all the literature, knew what (Henri) Matisse and (Pablo) Picasso were up to. They shared this knowledge, showing Indian artists catalogues and works from Europe. So, when you spot a hint of Matisse in Ara's work, it's still distinctly Ara's style. It's not far-fetched to think this European influence came from Langhammer or Leyden. Langhammer, being a teacher, exposed artists like Raza to European works too. But he stressed that artists should always reflect their own surroundings. Rudi was firm on that point.

|

Walter Langhammer, Untitled (PORTRAIT OF A WOMAN AT A SPINNING WHEEL), Oil on Canvas, 22.7 x 28.0 in. Collection: DAG |

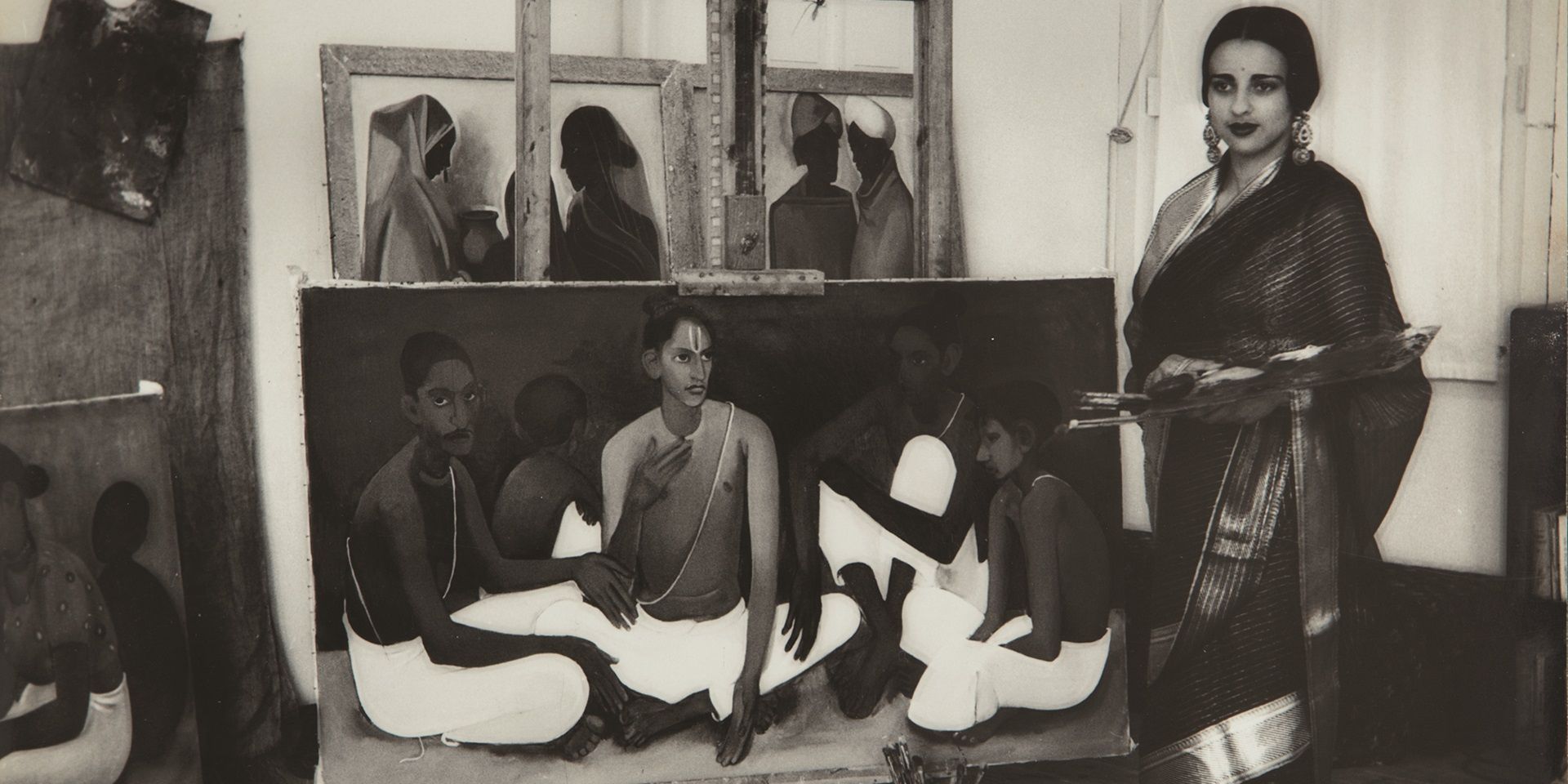

Q. How did you come to be interested in the world of these European exiles who influenced the trajectory of Indian art? And how did you decide to write it?

Reema: Yes, I’ve written about this in the Preface. But just to give you some context, back in 2016 when Raza passed away, I visited Krishen Khanna's home. Dr. Saryu Doshi had penned a brilliant piece for the paper I worked for, Mumbai Mirror, a widely-read city paper. However, we, as a Bombay-based publication, felt the need to honour Raza's legacy as well. His life epitomised the quintessential Bombay narrative. Coming from Madhya Pradesh, he made a mark as an artist in Bombay, establishing the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group, of which he was a founding and last surviving member. So, I met with Krishen Khanna, who shared several anecdotes. Towards the end of our conversation, he asked me about what Times was doing with the writings of his friend, Rudi von Leyden.

|

S. H. Raza, Untitled, Acrylic on paper, 1978, 24.7 x 18.7 in. Collection: DAG |

I stared at him quizzically, admitting I was possibly drawing a blank. ‘Probably nothing,’ I responded. But he suggested that I take a look at it since I was already there. Intrigued, I went into the archives on the second floor. Thankfully, everything had been digitised. As I sifted through, I stumbled upon a trove of articles by Rudi von Leyden. His writing was pointed, persuasive, refreshingly devoid of jargon, communicated in simple, coherent English—an oasis in itself. Recognising this as a rich vein of art history, I embarked on the journey of compiling a book. Serendipitous encounters followed: meeting his family members, his third partner, Udi, and individuals in Bombay like Gerson Da Cunha, Alyque Padamsee, Mithoo Coorlawala, and Katy Soonawalla. I pieced together his life while looking through archives such as the Asia Art Archive, Chemould Archives, Tata Central Archives, The Times of India Archives, and the Raza Foundation archives. Interviews, letters, diary notes, and archival material, along with conversations with individuals like Gulammohammed Sheikh and Jyotindra Jain, formed the bulk of my research, which went into the creation of this book.

I chose to write in accessible language because, although I have extensively written about art, I have spent over a decade writing for mainstream media houses. Over time, I kept hearing from colleagues and friends outside the art world about the issue of gatekeeping. They asked why there's so much exclusivity. Their feedback struck a chord with me. I realised that whether it's art or legal jargon, when you break it down, you open up the industry to a wider audience. So, I didn't want this book to be confined to art enthusiasts only. I approached it more as a social history book. For me, the stories of old Bombay were just as vital as Rudi's, Ara's, or Raza's lives. Learning about Rudi's sister starting the hockey team at Bombay Gymkhana was as fascinating to me as Rudi discovering Ara. To make this world captivating to readers, I had to keep the language accessible. That's just the way I write, and it's the only way I know how to do it.

K. H. Ara, Untitled (Banganga), Gouache and watercolour on paper, 1929, 12.5 x 20.0 in. Collection: DAG

Reema Desai Gehi is an arts writer and editor based in Mumbai. She has contributed her writings towards various publications such as the Mumbai Mirror, India Today and Hindustan Times, covering stories on art and culture. She has recently joined Art India, as its editor.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

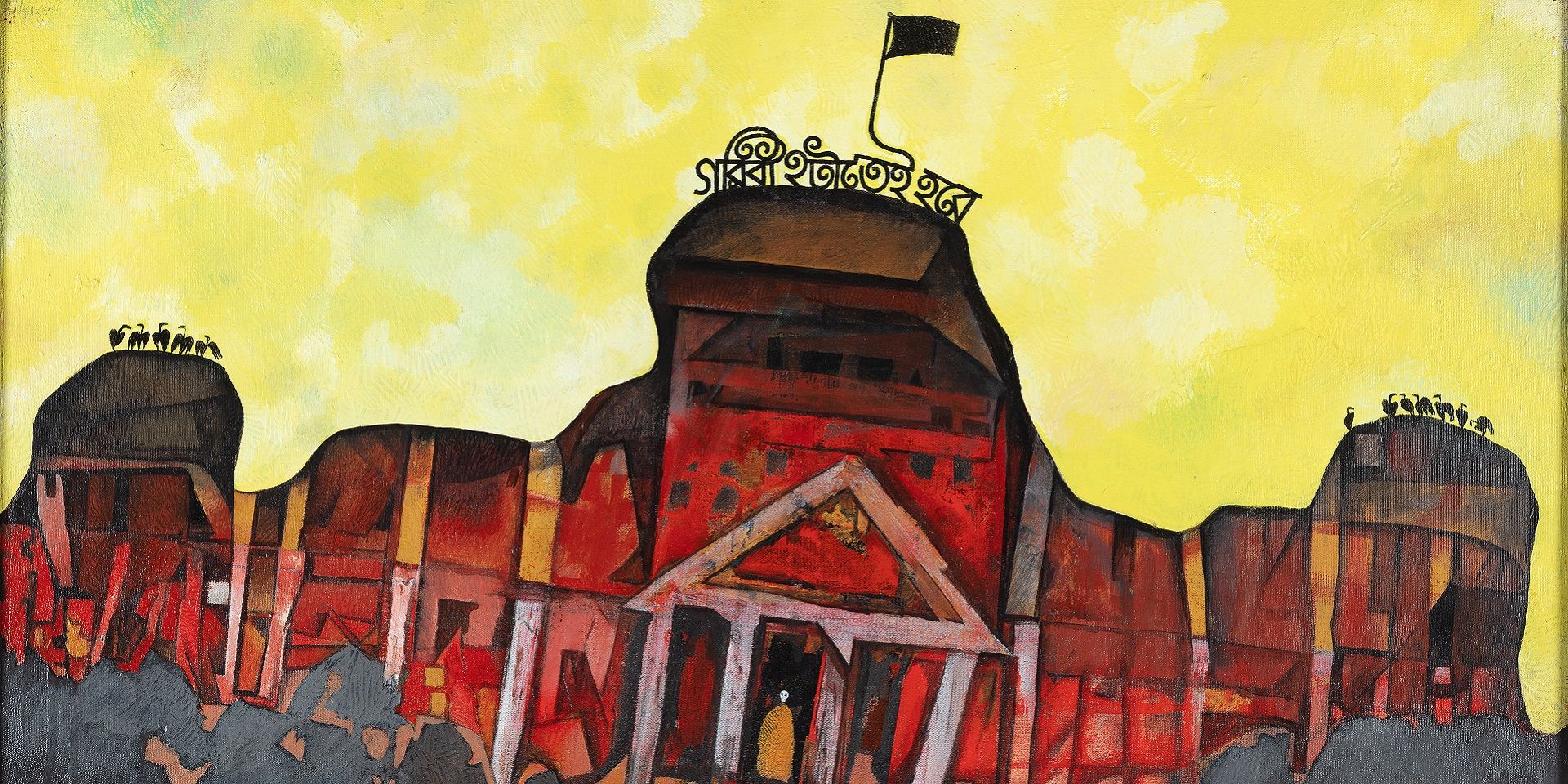

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

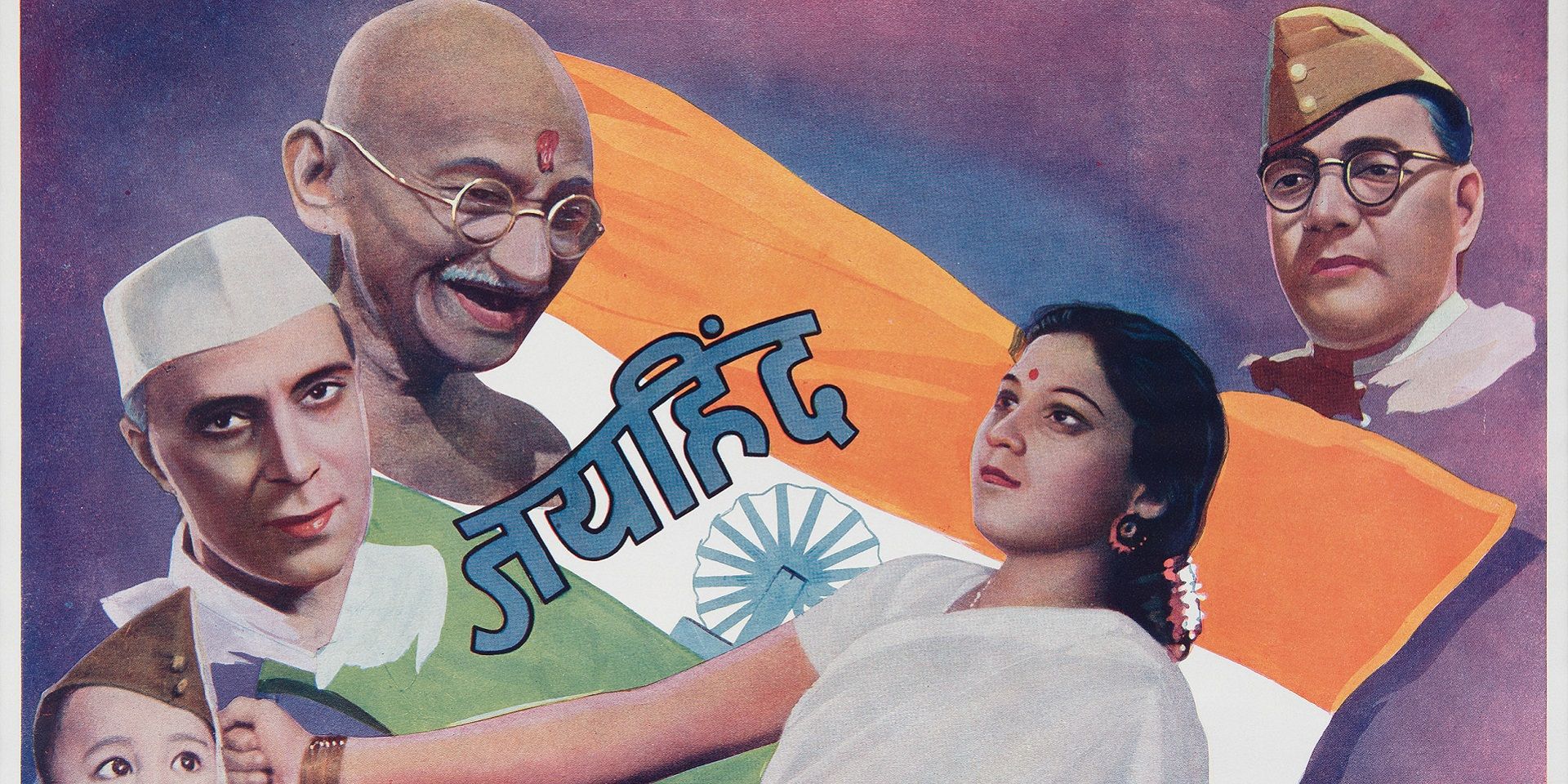

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

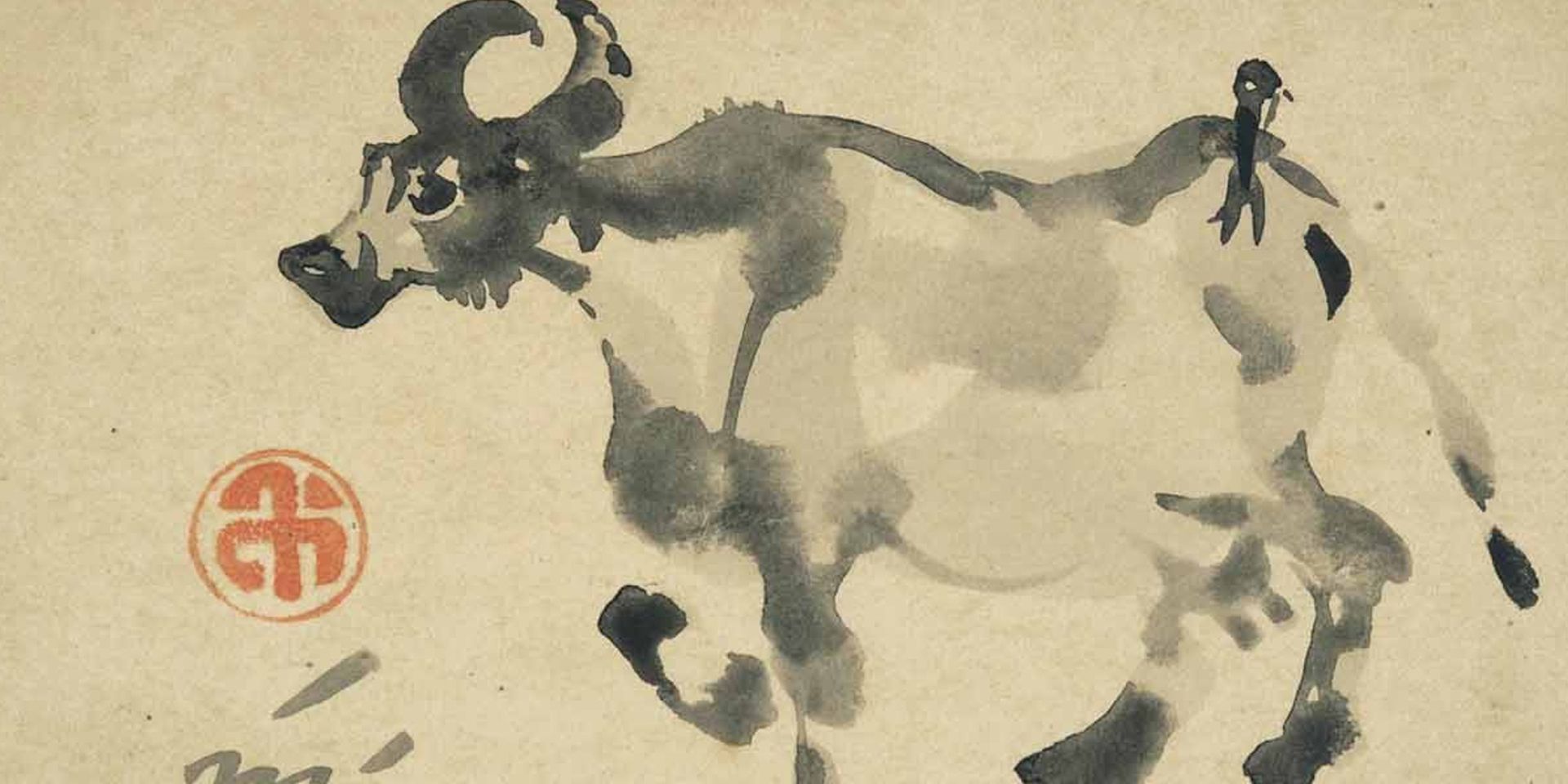

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025