Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

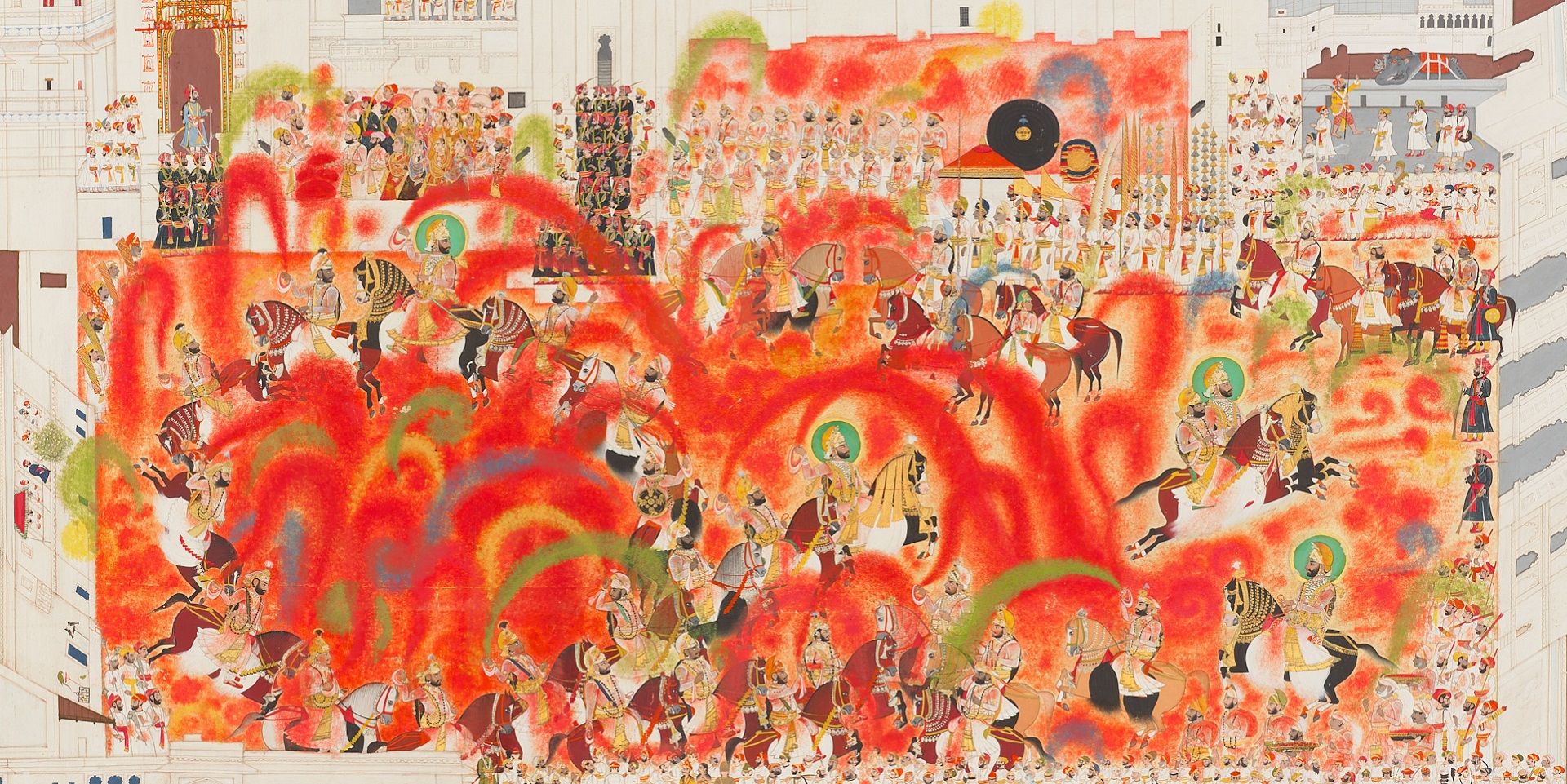

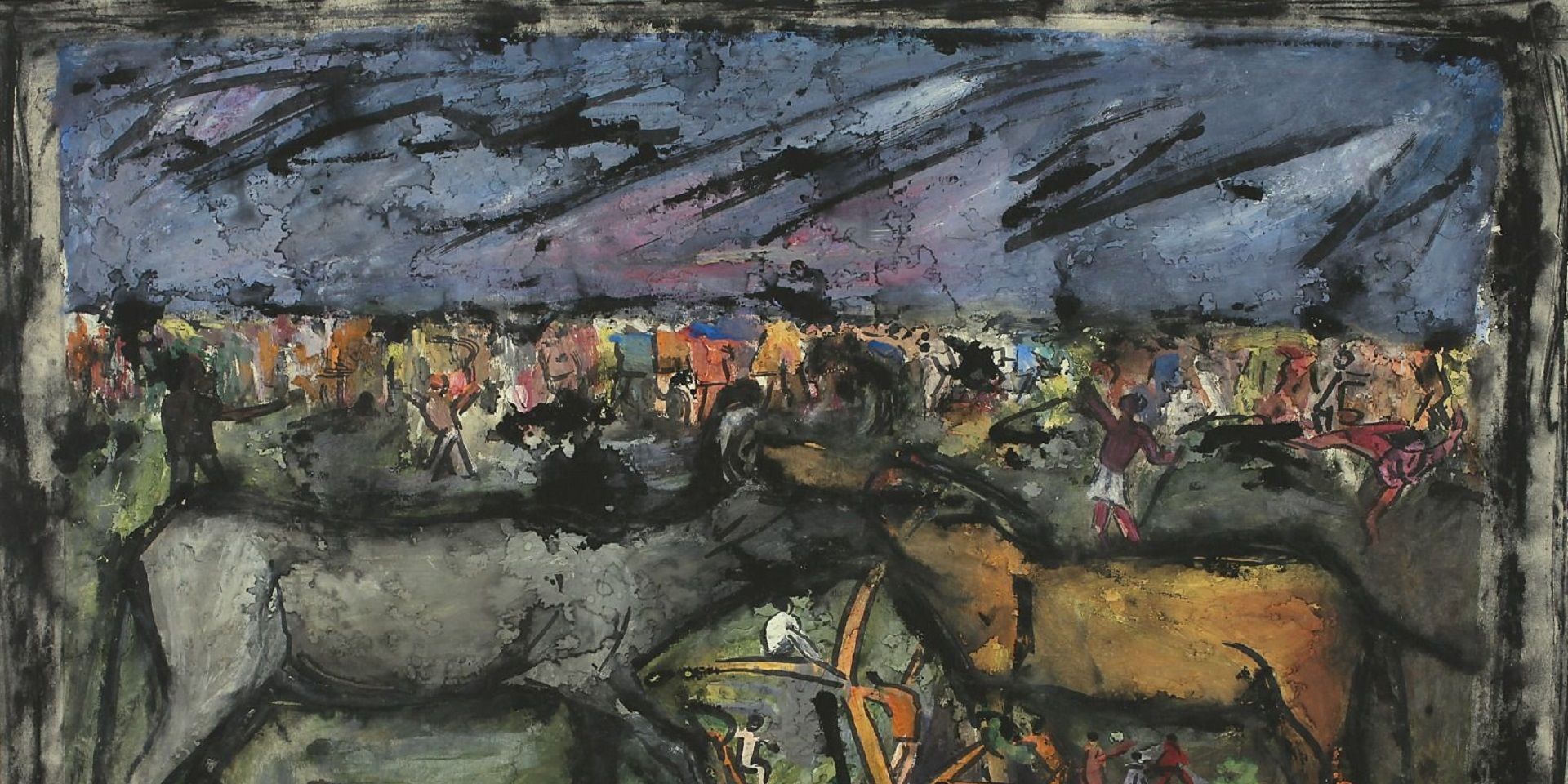

Maharana Swarup Singh and courtiers playing Holi at the City Palace(detail). Attributed to Tara, ca. 1851 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper Sheet, 92.2 × 125.5 cm Image, 86.1 × 117.7 cm. Credit: The City Palace Museum and M. M. C. F. (Udaipur)

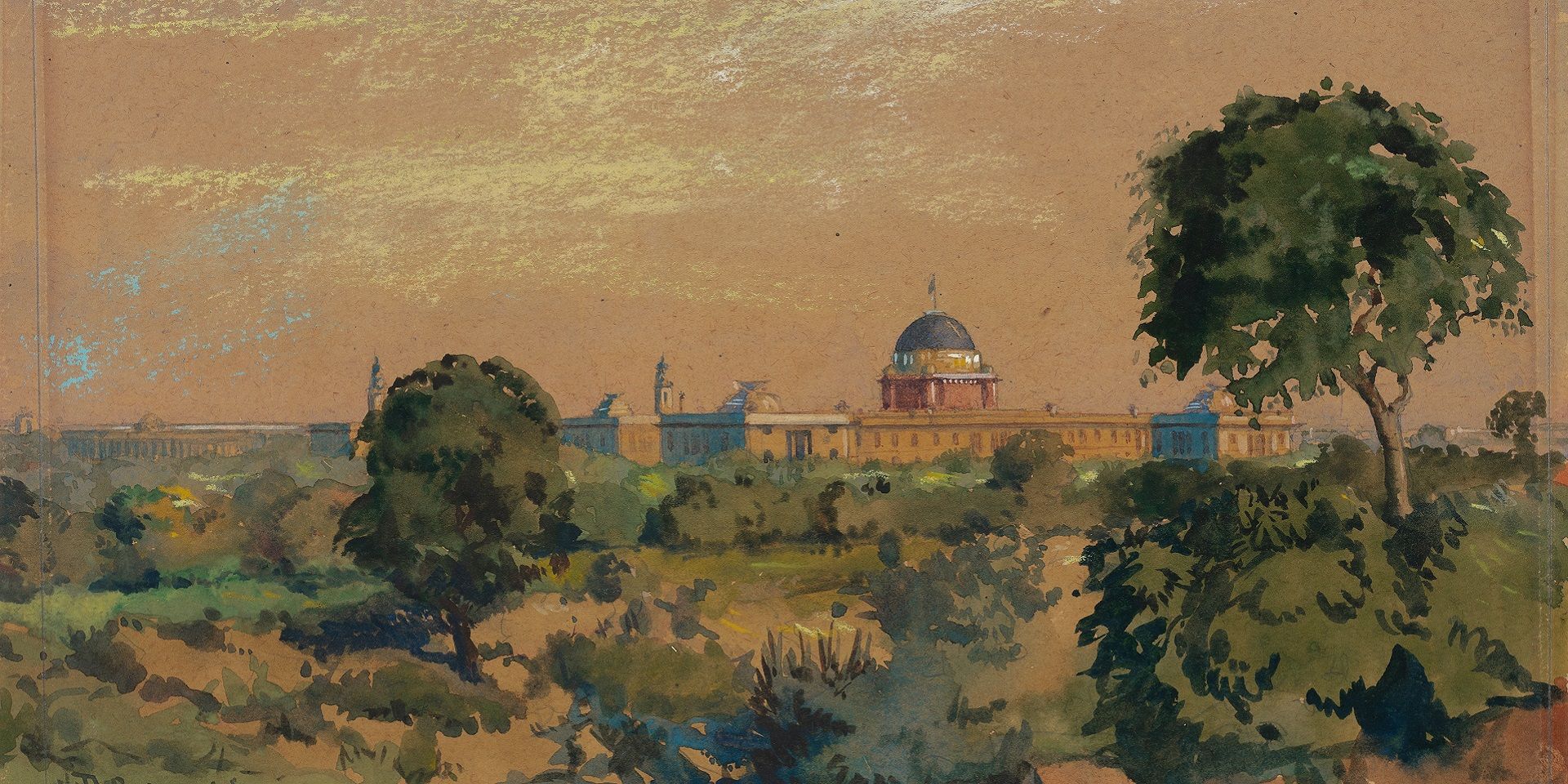

As part of the Smithsonian Museum’s centenary celebrations for the National Museum of Asian Art, a series of exhibitons and programmes have been curated to reflect on the museum’s collections of art and photography from Asia. A painting exhibition has been co-curated by Debra Diamond and Dipti Khera, featuring works from the royal court of Udaipur, titled ‘A Splendid Land: Paintings from Royal Udaipur’.

The exhibition attempts to show that ‘around 1700, artists in Udaipur (a court in northwest India) began creating immersive paintings that express the moods (bhava) of the city’s palaces, lakes, and mountains. These large works and their emphasis on lived experience constituted a new direction in Indian painting’. How does this lived-experience and an emphasis on sensorial mapping of landscapes translate for an ordinary museum goer across the world today? Diamond spoke to DAG explaining how art was used as a gateway to the senses with this show. What follows is an edited excerpt from the conversation.

Q: The show originated with a graduate course taught at New York University by you and Dipti Khera, who is an associate professor in the Department of Art History there. Could you tell us more about how it fed into the curation and making of ‘A Splendid Land’, especially the thematic of reception?

Debra Diamond: Dipti and I were working on this exhibition for almost ten years. I have always been interested in Udaipur painting—with Hindu or, Indian court painting being my specialty—and I was really excited by Dipti’s work on bhav and reception, because we know very little about the reception of the visual arts in India historically, unlike the aesthetic reception of plays, poetry or music, which we have more accounts of.

So in the case of Udaipur, there were two things that were going on. One was that we knew a lot about reception because of Dipti's work and the fact that these were meant to engender bhav (meaning, feeling or emotion) and that it was revolutionary in the sense that instead of conveying the bhav of idealized or abstract emotion, which were usually symbolized by heroines in the epics, in these works it was about evoking the emotion, the memory, the mood, the ambience and the sensorial experience of being at a particular place, which could be a local place, on a particular day over a certain number of hours with very particular friends or allies or lovers. So that was really different. And then we also have these remarkable shifts in scale with these huge paintings, which are immersive and experiential, along with smaller paintings that can be held in our hands. So then I was really excited with the possibilities: if these paintings were made to be immersive and experiential, as a curator I thought that they could be exhibited in new ways too. So we did that.

Each room (in the show) is devoted to a particular mood, which is typically a particular place, like the lake palaces or the countryside around Udaipur. Each group of painting is devoted to a particular mood, which is enhanced by the brilliant soundscape (designed by the filmmaker Amit Dutta).

So immediately, even if people don't know India and nobody has lived in the eighteenth century, as soon as you walk into a room, it's like, OK, I'm somewhere, I can feel it. People can engage emotionally as well as visually, aesthetically or intellectually with the work. That was the premise behind the show and that's why we were interested in doing it, and Dipti and I both love to work with students. We split the course into two halves and in the first half they learned about Indian painting and aesthetics and the broader global history of emotions, while the other half was a museum practicum, with speakers and designers conducting workshops with them. So this a process of learning how to speak to broader publics and lots of graduate students right now are interested in the potential of public humanities. So each one did a longer web project which is on our website, and then they distilled that into their labels, which are seventy-five words each and focus on sensorial readings of the works in the exhibition.

Visitors interacting with the painted works on display, accompanied by music designed by Amit Dutta. Credit: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Q. The show was also made possible through various partnerships, such as with the City Palace Museum in Udaipur and the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation. How did the process of choosing works and the partners’ roles evolve? How many works are there in the show in total?

Debra: Well, we have two venues, and the paintings have to rotate so the number is sort of fudgy because about forty paintings are shown in both venues. And then there's sixty-three in ours and there might be sixty in Cleveland, but altogether there's about eighty paintings.

Sixty-three sounds like a small number of works, but the big ones are so huge. I mean, just to look at the opening painting, which depicts sunrise at Udaipur—it is five-feet across and has hundreds of figures, different kinds of animals and there's just so much in it to look at.

The City Palace were our collaborative partner, so they were the biggest lender to the exhibition. We negotiated with them and chose the paintings together, then our head of conservation and our painting conservator went there on several trips and gave ideas and suggestions for how they could create their painting conservation laboratory because they didn't have such a facility before and now they have a world class painting lab, with three full time employees. The first thing they did was conservation work for the paintings in this exhibition.

And this week (the last week of April, that is) the people from the City Palace are here again for more meetings. Because what we were looking for is not a one-time engagement where we borrow the paintings, we show them in America, then we return them; instead, we wanted to create a long-lasting, reciprocal relationship that will also include the exchange of personnel.

Shambhu, Maharana Ari Singh II at worship in the City Palace, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, sheet: 67 × 53 cm. Image courtesy: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Q: The scale of many of the works on display are massive and intricately detailed. How were these works seen or received? Were they mostly seen in private, in the form of albums, or were they displayed publicly?

Debra: I think one of the big challenges for Dipti and me is that there's still a lot of Orientalist constructs about Rajput painting floating around in India, as well as in the United States, suggesting that the rulers of these Hindu courts were decadent despots, their painters were copyists, they weren't creative, they couldn't do naturalism (etc.). I found a couple of things from the scholarship I saw floating around. One was that all of these paintings were understood as fantasy landscapes or they were all understood as portraits, which they are not. Secondly, there were arguments that Indian artists prior to the British didn't represent cities at all and the British had to teach it to them; and Indian artists or Indian courts did not create the conditions in which people could have friendships.

So we wanted to create an exhibition that would subtly shift the focus of these arguments, because when we went and looked at those big paintings, we found a series of details that countered these prejudices and told us much about reception. Artists in the royal atelier produced these paintings—we have their names inscribed on the back.

The paintings were given to the King as nazr, as a gift. And then they were laid, we think, on a low table, on a white cloth. And then the king and some courtiers, who were his relatives and brothers and cousins and uncles, would sit around, and they would look at it and they would collectively remember the event that was depicted. ‘Oh, this was when we all went to the Sarbat Vilas Rose Garden for the Rose Festival’, or ‘we listened to this musician’ or ‘we saw those dancers’, or ‘we went hunting’: they're using these pictures to remember.

And in the hunt scenes they're often remembering the heroism of someone who's not the king. It could be one of the Thakurs, one of the noblemen. And while they are sitting around there remembering these things a scribe writes it up on the back. So the audience for these, apparently, was limited to people at the court. Unless, you know, paintings were given as gifts to allies and to courtiers, or later to the British and Portuguese. And the paintings that were given as gifts seem to have been smaller.

But what I can imagine is that when people sat around and talked about it, you would get all those qualities of gold flickering, because you'd be moving around. And knowing this court and the room in which they would have been viewing them, they were also probably listening to music and smelling flowers at the same time too.

We have these rare written references, some from the Mughal court and others from archives in Udaipur, of how they were looked at, so we can reconstruct some of that process today.

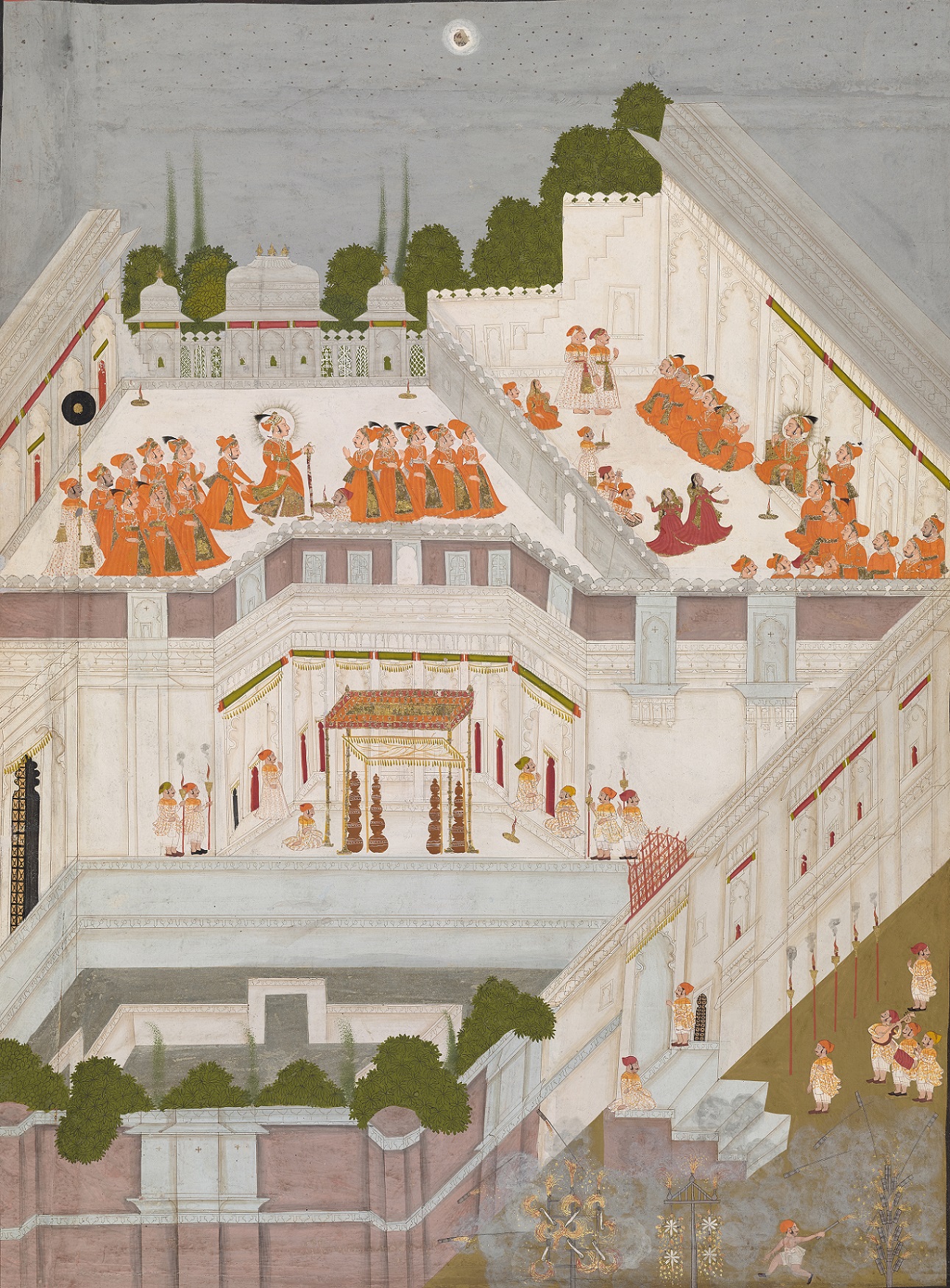

Bhima and Kesu Ram, Maharana Ari Singh II at a moonlight gathering, 1764, Opaque watercolor with gold and silver on paper, Sheet: 67 × 51 cm. Image courtesy: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Q: Some of the arguments that you also make through the show is about how these works tend to foreground the environment, the animals, birds, climatic forces, as active agents in these narratives; but there are these contradictions about how they are cared for, since they are being hunted regularly for sport or food. There is a general discourse of awareness about the environment that comes across though—why do you think this is happening in Rajasthani (or, Udaipur) painting around this time?

Debra: Let's split the environment question if I may, into two. So one is water, including water infrastructure and its impact on the climate. We have put a big emphasis on that in the exhibition and in programmes and talks. Some of the poorest, semi-arid areas were dependent on annual monsoon and water harvesting. And India was underpopulated until the 18th and the 19th centuries. So what did they do? All of those lakes, that whole lake system, is entirely artificial.

There's one perennial river in that region around Udaipur. So you have this vast and complex infrastructure of water harvesting in those giant tanks which are connected by canals and sluices and all sorts of different wells. Every single painting in the exhibition has water in it. There are landscapes without sky (something that is unimaginable in western landscapes), but there's always water, and often their water infrastructure is lovingly depicted. There's a painting that has sixteen wells of different types including a dam and a sluice. The paintings are often dated quite precisely, so we know that this happened in a certain week in August in the year 1767, for instance. And now, according to climate scientists who came to our December 9th, 10th symposium, these constitute an archival document about the monsoon that year.

So those paintings are always acknowledging water or celebrating water, celebrating water harvesting or conveying the moods and the memories and the sensorial experience of the monsoon, which, in Udaipur was a beloved event.

The sense of self and pride that Udaipur kings had was connected to this massive undertaking of water harvesting. And I thought that will really relate with our audiences.

Today, no matter where they're from, everybody knows about climate change and the Smithsonian as an institution understands it to be the existential threat of our time. So we were connecting into that in order to make people understand something about India and their early accomplishments. It also works to counter those Orientalist canards about despotic and incapable Rajput kings who needed the civilizational lessons of the British.

About the animals—well, of course they're hunting and they're eating them. Boar hunting is especially important. ‘Predatory care’ is the phrase I learned from Indian scholars to understand this relationship better. They did not hunt animals into extinction. They maintained a balance, especially when it came to animals that had multiple uses in transport or warfare, like the elephant.

They also made sure that the forests weren’t hurt. They purchased their elephants at the age of twenty from the tribal communities. They named them and they loved them, so that there's a whole science of elephants all over India by then.

We also know that they created these things called bir, which were like protected landscapes. They wouldn't let villagers or cows touch these fields. And they would put bird seed in them so there’s places for birds. We would think of them today as a bird sanctuary. But of course they're doing that so they can hunt them and eat them eventually.

And it's only when there's a famine, a drought, a bad monsoon, drought, a famine that they take the protection away and let you know villagers and cows go in there. So there always modes of attempting to maintain balance.

Visitors taking a closer look at the details of an Udaipur painting. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Q. There is also the context of a fast-changing political scenario in north India at the time. In colonial cities like Calcutta or Madras, new forms of painting for the East India Company were being innovated, while artists from erstwhile Mughal ateliers were moving to smaller princely courts skirting the colonial territories—so goes the narrative. With these paintings that still have such busy surfaces, instead of a resolved, singular perspective, how are these technological changes and new market demands being adopted?

Debra: Yes, we do have a master narrative of Indian painting. One gets the sense that by the 1800s ‘company painting’ has taken over as a dominant aesthetic. But that's just the way that our history is written as if there's a single march towards something; instead of looking at how art develops in all sorts of local environments.

So I do actually think that art history, which was first written by the British to a great extent, tends to privilege this moment of company painting.

In Udaipur, what we see from 1700 onwards, even earlier really, from the 17th century onwards, is that artists are looking at lots of different things: such as western Indian painting, court painting from Rajasthan and Mughal imperial painting, among others, from which they are pulling out different elements and styles that appeal to them. And they're just put together so creatively (and humorously) by different artists in different moments, because they would be saying to themselves that they want to paint the mood of the city palace on this night in a different way than someone else who painted it.

So there's always a lot of different styles going on. In one painting there's different vantage points and perspectives, and different modes of conveying narrative time; sometimes it's conceptual and sometimes it's perceptual.

So when the British come in, and more European art comes in during the 1800s, and then photography arrives, they represent just another set of styles in their toolbox. In one of the paintings in the show, made by Shiv Lal over 7 years, roughly in 1870, we see a vanishing point being employed; the artist's brother was a court photographer, and Shiv Lal has painted photographs as well as this paining. So you see him using that one-point perspective to tell the story.

It locates you in the middle of the canal and you feel so wet, it's delicious. There's a city scene we have of the Shitala Mata Temple festival and there's a photographer, with his camera, in the middle of the painting!

These works do not look like company painting usually. They're not doing the single figure against a white background type of thing. But they're incorporating those kinds of elements as things come into the court. Photography makes a big impact on many painters who saw it practiced around them.

Maharana Swarup Singh and courtiers playing Holi at the City Palace. Attributed to Tara, c. 1851 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper Sheet, 92.2 × 125.5 cm Image, 86.1 × 117.7 cm. Credit: The City Palace Museum and M. M. C. F. (Udaipur)

Q: Now, about the busy surfaces of these works—how did you go about interpreting the actions being carried out or depicted? Many of them unravel in a non-linear manner, the chronology is often dispersed across the whole surface instead of leading from one point to another. Were there any inscriptions to go by?

Debra: This was so interesting to me because it took a long time to figure out how to read these paintings. But we do often have quite long inscriptions on the back. And we do know that they represent specific events or journeys. So one thing that we did was when we had a landscape, with rivers and mountains, we would put them together with what we could see on Google Earth with some GIS mapping and all of a sudden everything changed really! We could see where the artist would have stood on a hill to depict a scene, and we know that the artists were also map makers, and that they had access to maps, or they did architectural plans and had access to those plans.

So they're pulling in not only imagery that comes out of maps or architectural plans, but also that kind of knowledge. This is the way you know the world, and this is the way you map it. And I’m talking about Indian maps, not European ones. Indian maps may not look factual or realistic to us in the modern world because we're used to a certain kind of map, but they were using those maps and they knew how to navigate the world. It's just that they used a different mixture of planned views and elevation views.

So in any given landscape, if you see the little (figure of the) King moving around—like in a hunting scene—everything is geographically and cartographically plotted. The King will always be coming from the direction of the City Palace. He's moving through this landscape. Even the course of the rivers—you could lay it on top of Google Earth today, and it'll be an exact match.

So what they do is by mixing the planned view, the overhead drone view of a field, with a river, and elevation views of the mountains: this is the way the landscape works, this is the way the river goes, this is the view of the mountains when you come in. They mix these together and create something akin to a stage set.

Whether it's architecture or landscape, it’s very exact. If you know those places, you could chart the story. It means the king entered this valley coming from the direction of Udaipur, and then his friend Thakur Sardar Singhji came and met him here. And together they went to this place. And remember the court who's looking at it, they knew those places well. They knew what it was like to walk into this courtyard of the City Palace or to look out of that window and see that part of the city. So they're kind of hyper realistic. It's just that they aren't visualized in the way that you and I were taught to read realism. Because we were all taught to some extent that the Renaissance one-point perspective is the best and most accurate way to see the world.

|

Prince Amar Singh II walking in the rain, attributed to the Stipple Master, c. 1690, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 34.4 × 21.3 cm. Image courtesy: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase and partial gift made in 2012 from the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection — Charles Lang Freer Endowment. |

Q: One of the most attractive features of the show is this emphasis on sensorial mapping, and activating an affective interest in these landscapes. In a certain sense this makes it easier or more universal for audiences who want to enter the world of the painting, but bhav is a fairly complicated Sanskrit philosophical concept, so all these emotions, these senses are also very culturally embodied. They're located in space and place. Do you think this balance of the hyperlocal and the universal is creating new ways of knowing these works as well?

Debra: For visitors, in theory, you could hang up paintings from any part of the world, or any part of India or any moment and say I'm going to hang them by affect. I'm going to try and engender emotional responses in my audiences. But the reason we can do it for Udaipur is because their inscriptions show that they were trying to do this in the first place. So it's historically grounded in a way that it wouldn't be if I were picking paintings from the Imperial Mughal courts or from Jodhpur. And then in terms of visitors, when they're in the monsoon room and I'm going to pick here a mythic visitor—who has never been to India—so they go in the monsoon room. And what they're learning about is the climate, the love of the monsoon, that there are cultural ideas about natural resources that are distinctive to local cultures.

So they're learning all of these things and they can hear the rain falling so they can remember that feeling of wetness on a hot day. They can engage with what they know, and yet their mind is being expanded in a new way. And yes, they can understand what's happening in those paintings. So all of a sudden you can see they are celebrating the rain, right? They're talking about this as a prosperous kingdom—so that's I think what's happening for visitors. They’re being made to re-configure their own attitudes to the landscape and climate that surrounds them.

Once we looked at that, they made us look at the paintings differently. If you look at earlier art historical writing on Udaipur painting, they are all understood as portraits. But when you don't think about them as a portrait of the king, you will realize that this is a scene with twenty members of the court and they're hunting and look, it's not the king killing the elephant, but one of his friends. I use the word ‘friends’ because sometimes they were actually friends, and the painting is celebrating the accomplishment of someone other than the king at court. That’s important because the paintings were made during a changing political environment after the Mughal Empire became weak, when you needed to create bonds of loyalty and affinity among members of the court and allies. So we see that happening in these paintings, and it opens up a new way, perhaps even a more realistic way, of understanding what was happening in those courts, without relying on the testimony of colonial authorities like Colonel Tod.

Sunrise in Udaipur, c. 1722–23 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper Sheet, 82.3 × 152.4 cm. Credit: The City Palace Museum - Udaipur, Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation (MMCF), Udaipur

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

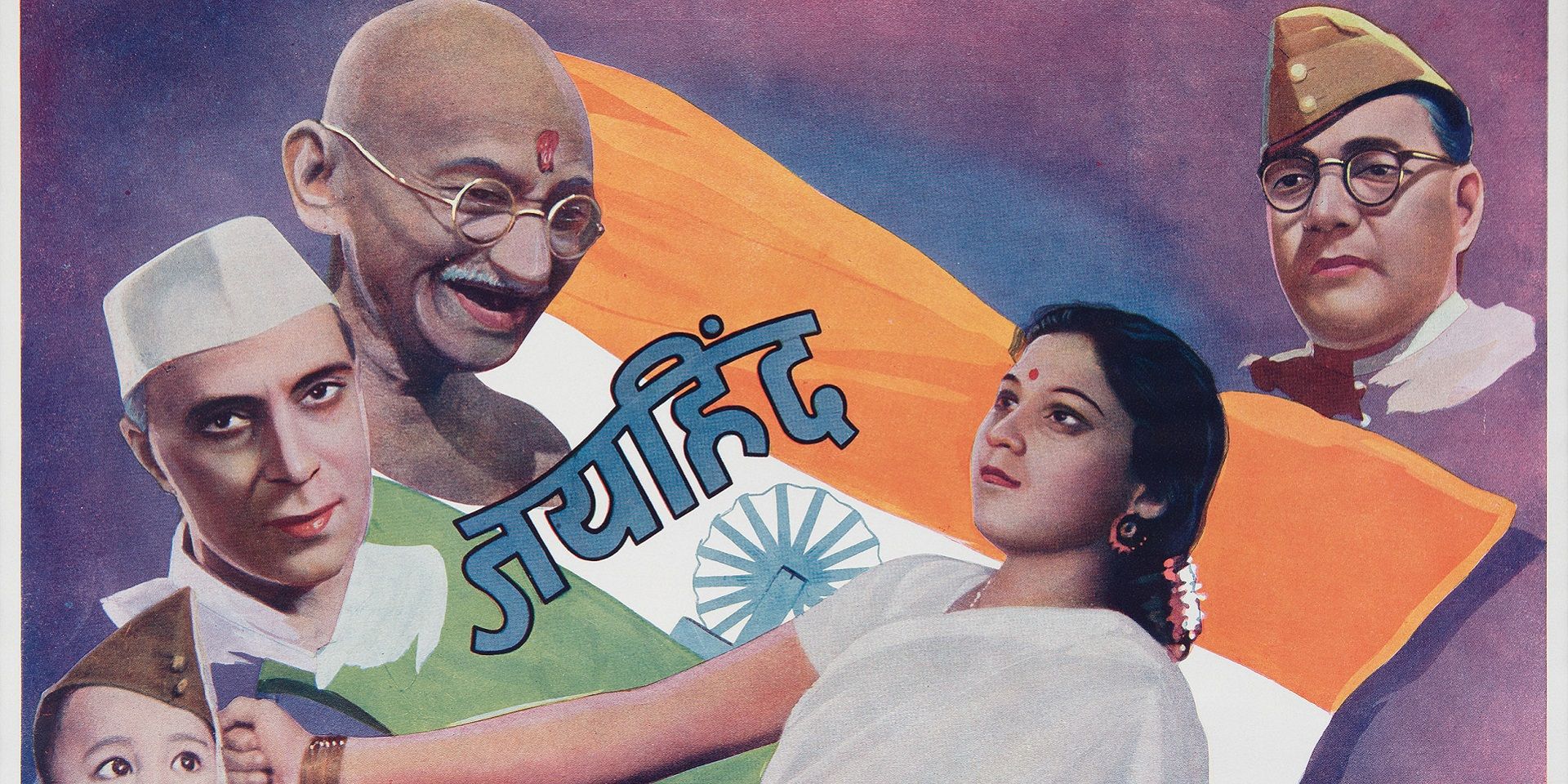

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

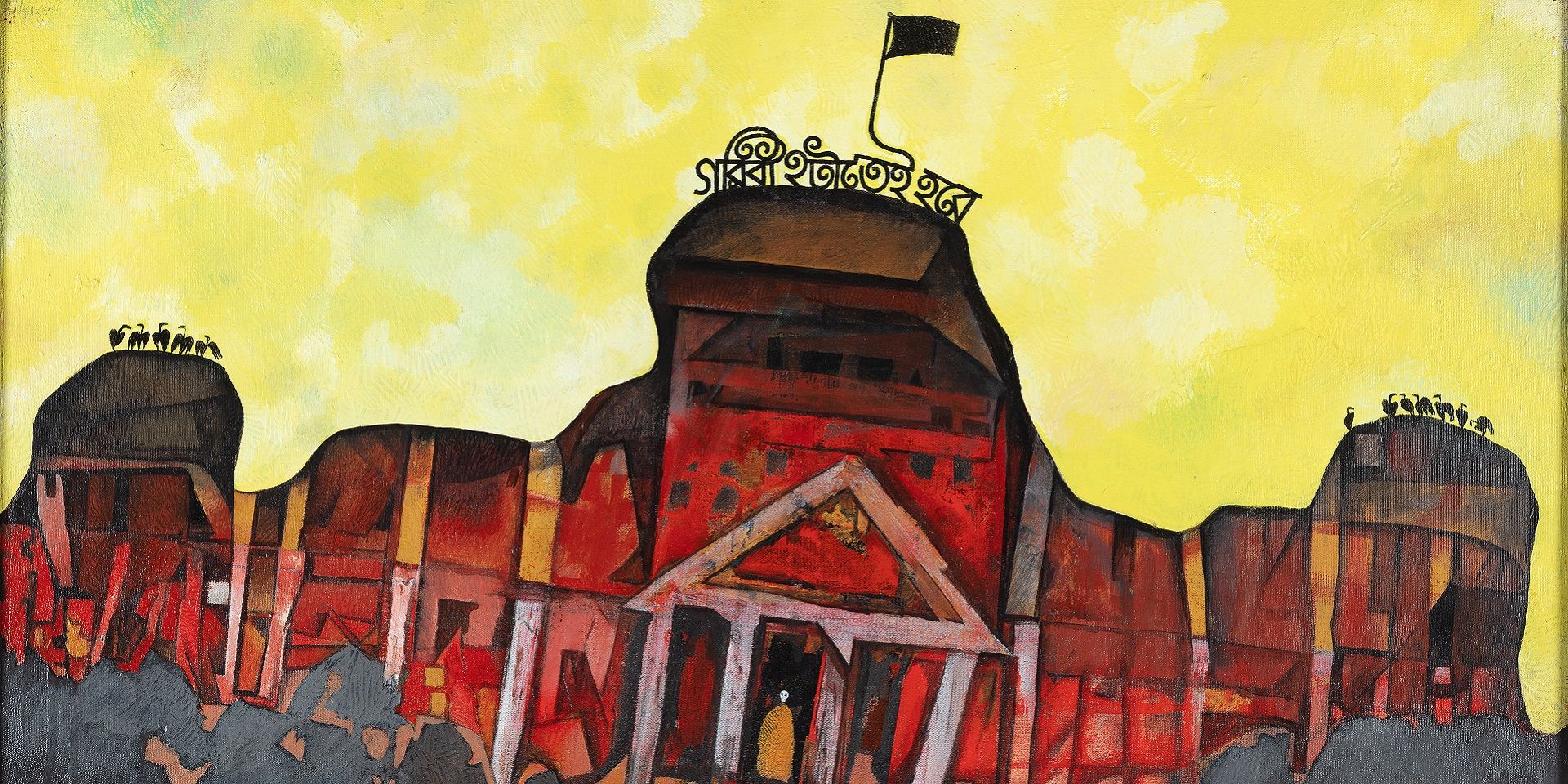

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

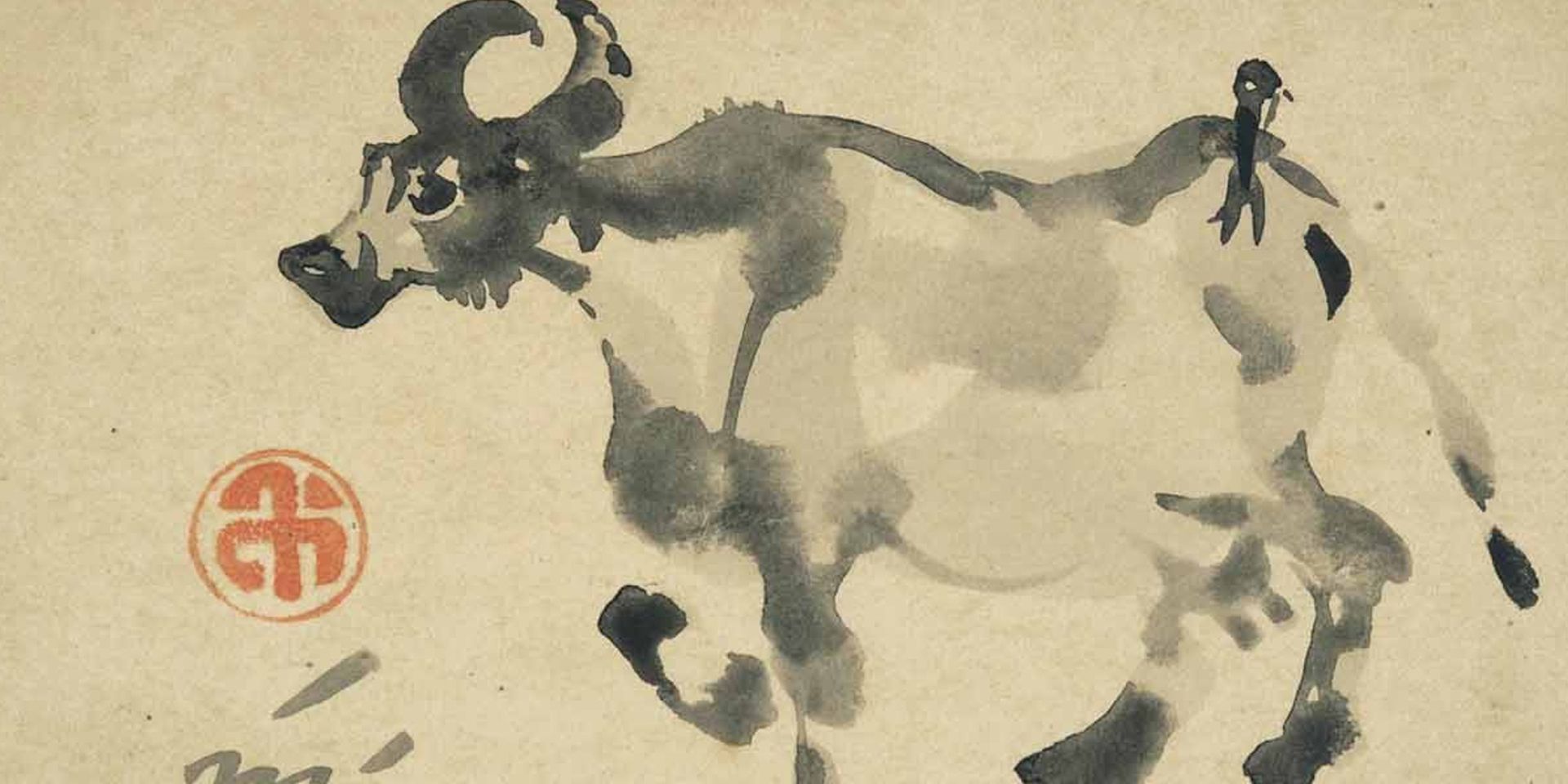

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025