Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

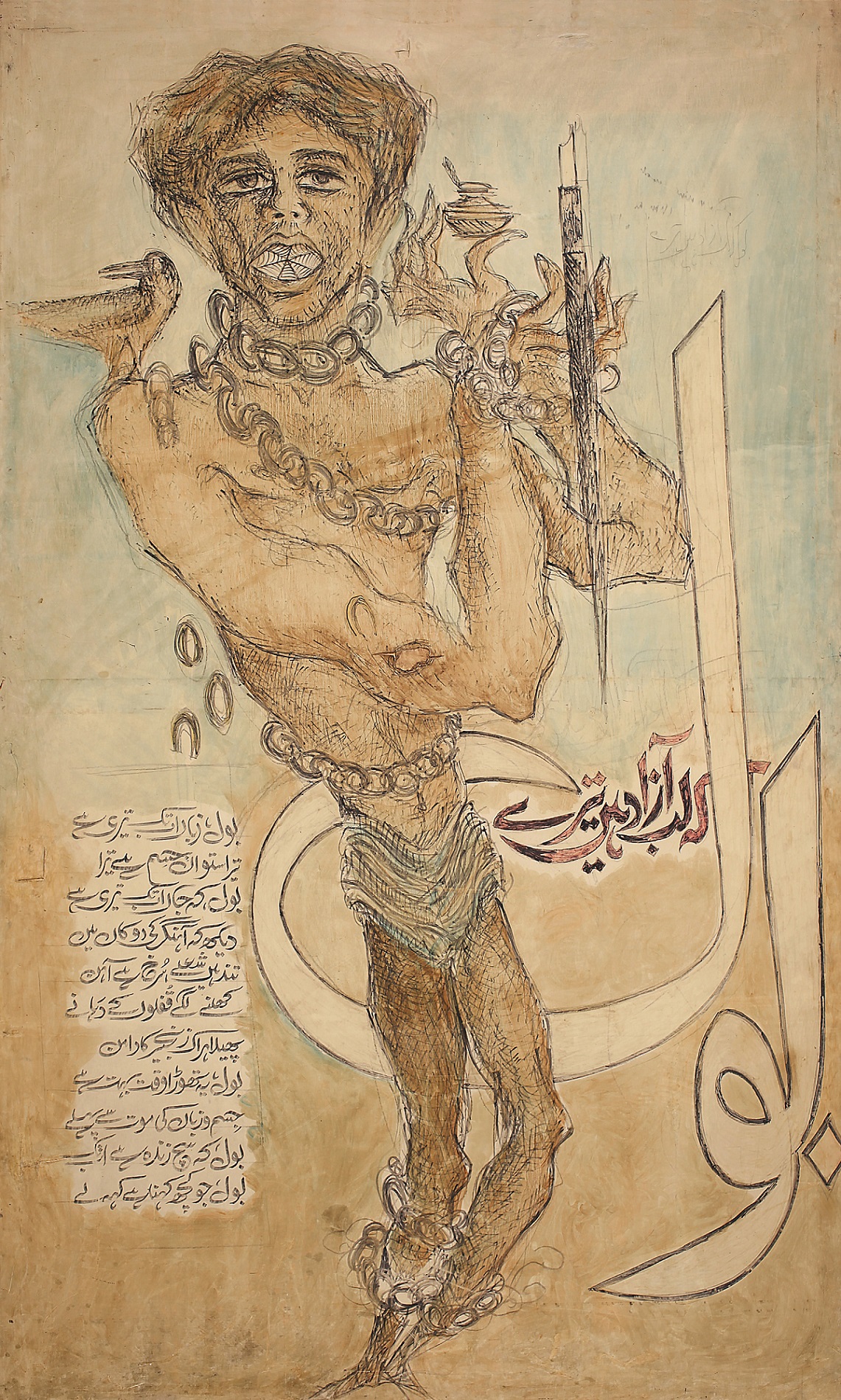

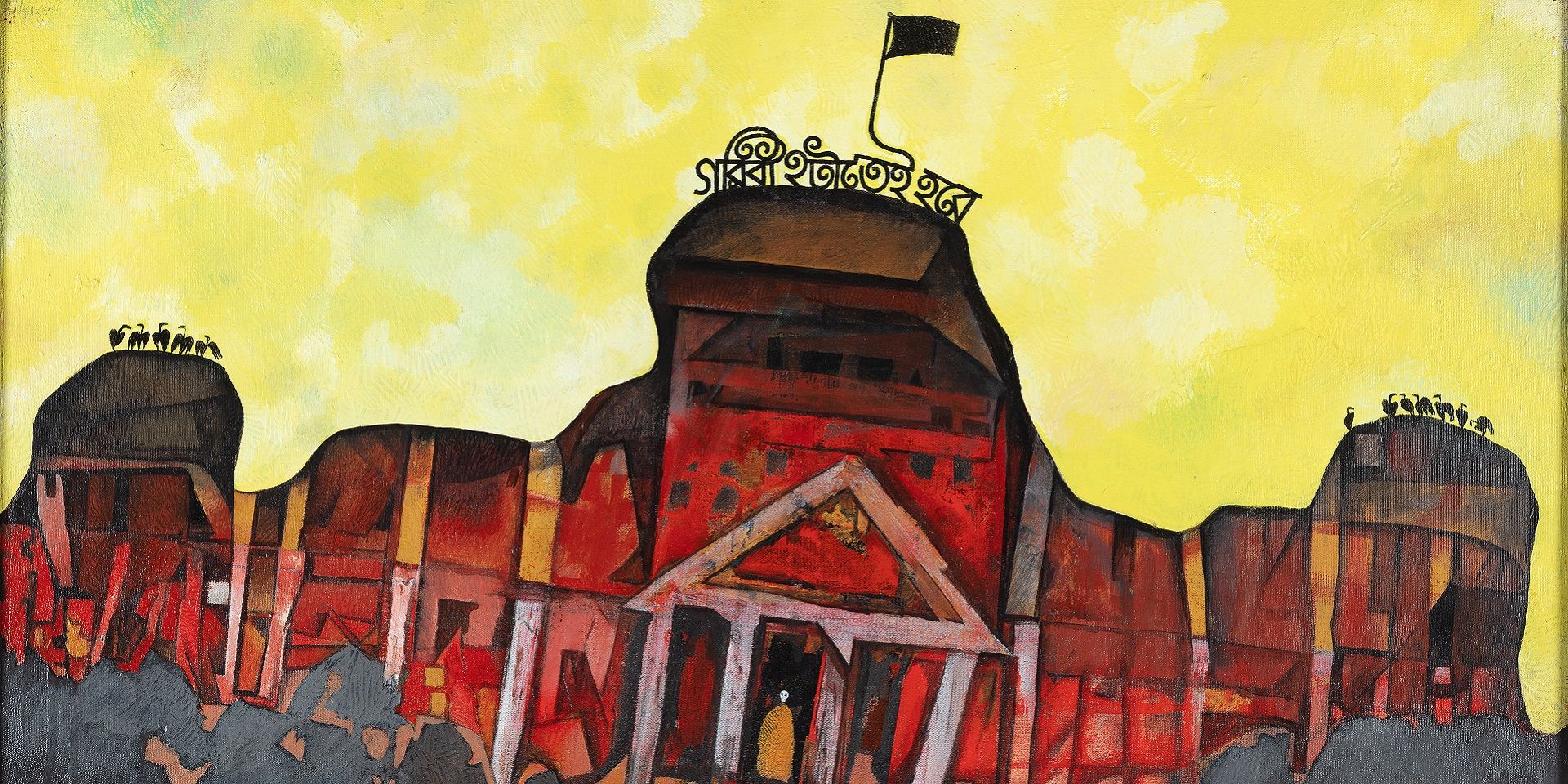

Sadequain, Untitled (Bol Ke Lab Azaad Hain Tere) (detail), Oil, marker and charcoal on Rexene, 78.0 x 47.7 in., 1976. Collection: DAG

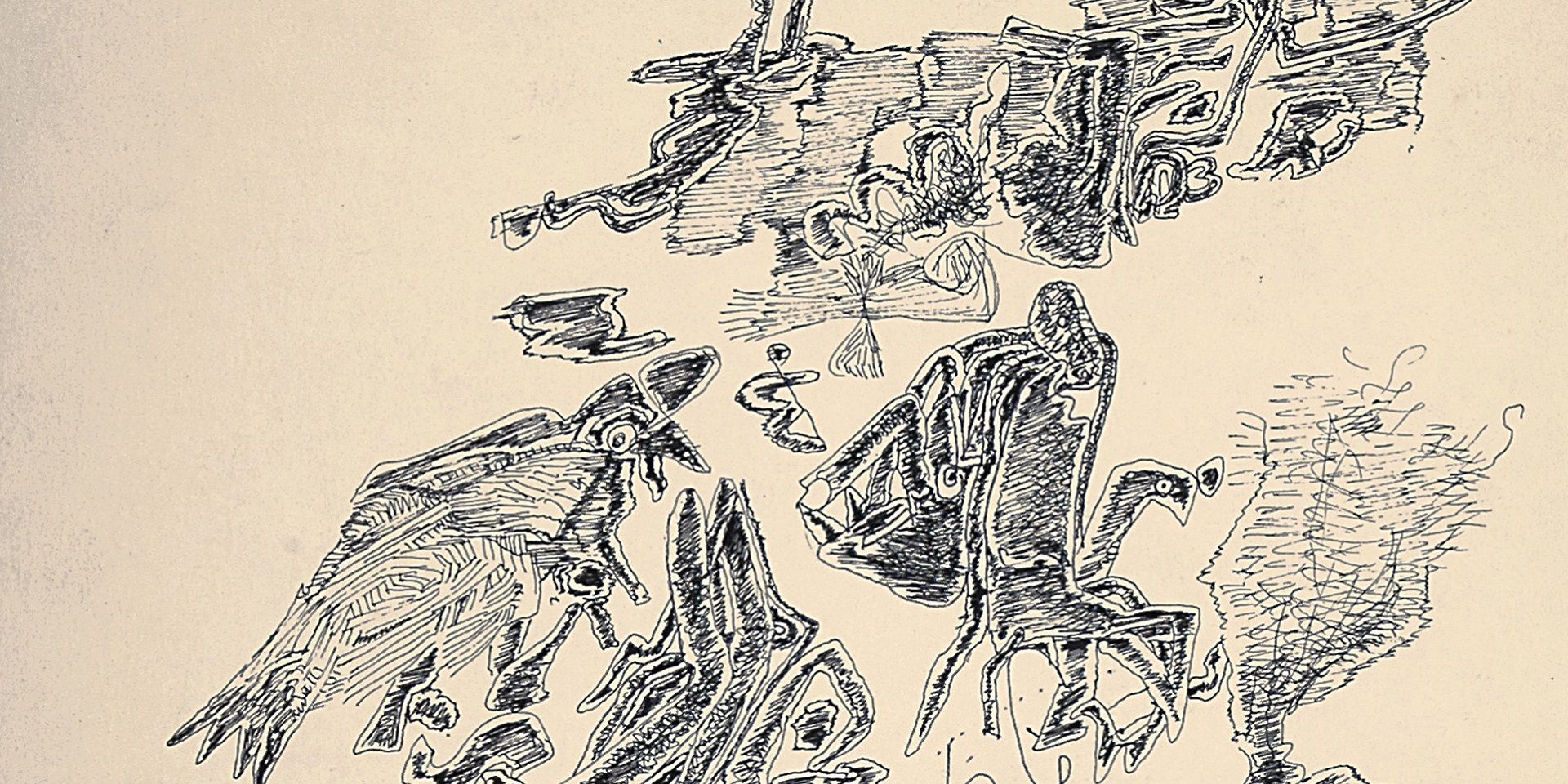

The intriguing choice of Sadequain’s pen and ink drawing ‘A Headless Figure Paints’ for the symposium poster and the cover of the recently published book How Secular is Art? is rather telling. The steady gaze of the decapitated double heads amidst hands poised in readiness to create, seem to readily usher the reader, confronted with the titular question, into fractured imaginaries of violence, threatened identities and the relentless urge towards meaning-making.

This collection of essays, co-edited by eminent scholars of art history, Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Vazira Zamindar, navigate the fraught religio-political contexts of South Asia to bring into relief the fragility and amorphous nature of a contested term like the ‘secular’. Although Prof. Guha-Thakurta reminds us that the volume is not wholly representative of South Asia, How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History, and Religion in South Asia successfully brings together some of the most articulate and erudite voices in the field to examine India's claim to secularity vis-à-vis other constitutionally non-secular nations like Pakistan and Bangladesh, which also have a long history of secular contestations. Writing about the secular’s shadowy career in the subcontinent, the editors say that

‘The question of ‘how secular is art’ stands inevitably sutured with the question of how secular are the modern nation-states of the subcontinent that emerged as core and breakaway entities across a changing political map, and how secular are their modern professional and institutional structures. The rhetorical question of ‘how’ in the book’s title can be extended, as the essays suggest, to the questions of ‘when’, ‘where’, and ‘to what extent’ can art be a safe habitus of the secular, and the secular ‘function as a guard and guardian of a domain called art’?’ (pp. 9, ‘Introduction’)

The immediacy of the questions raised in the book never ceases to resonate with the present conditions of life in the subcontinent, hurtling from one crisis to another. One of the co-editors of the volume, Prof. Guha-Thakurta, spoke at length to DAG about the relevance, and the limits, of the secular in the world of South Asian art today. What follows is the first part of the rich discussion that took place.

|

Sadequain, Untitled (Bol Ke Lab Azaad Hain Tere), Oil, marker and charcoal on Rexene, 78.0 x 47.7 in., 1976. Collection: DAG |

Q: In the backdrop of the events you describe in the introduction, like the Shaheen Bagh protests, how do we see the role of the artist-as-citizen in South Asian states today? Even as many artistic voices are predictably suppressed, there is a spate of exhibitions and shows hosted by public art institutions that display propagandistic works by artists who have forged otherwise secular credentials through their practice. Can art historians simply rely on the artist’s critical vision in mediating in their relationship with art, state and society today?

Tapati Guha-Thakurta: The conference out of which the book emerged precedes the huge spurt of protests against the C. A. A.[Citizenship (Amendment) Act] that took place across different parts of India in 2019. The point where we start the book, the protest site of Shaheen Bagh, erupted in the news as Vazira and I were planning this book from the conference held in Fall 2018 at the Cogut Institute for the Humanities in Brown University. A year later, as we were discussing how we could continue the rich discussions initiated at the conference, a set of new compelling political stakes began unfolding around us during that extraordinary winter of protest of 2019-2020.

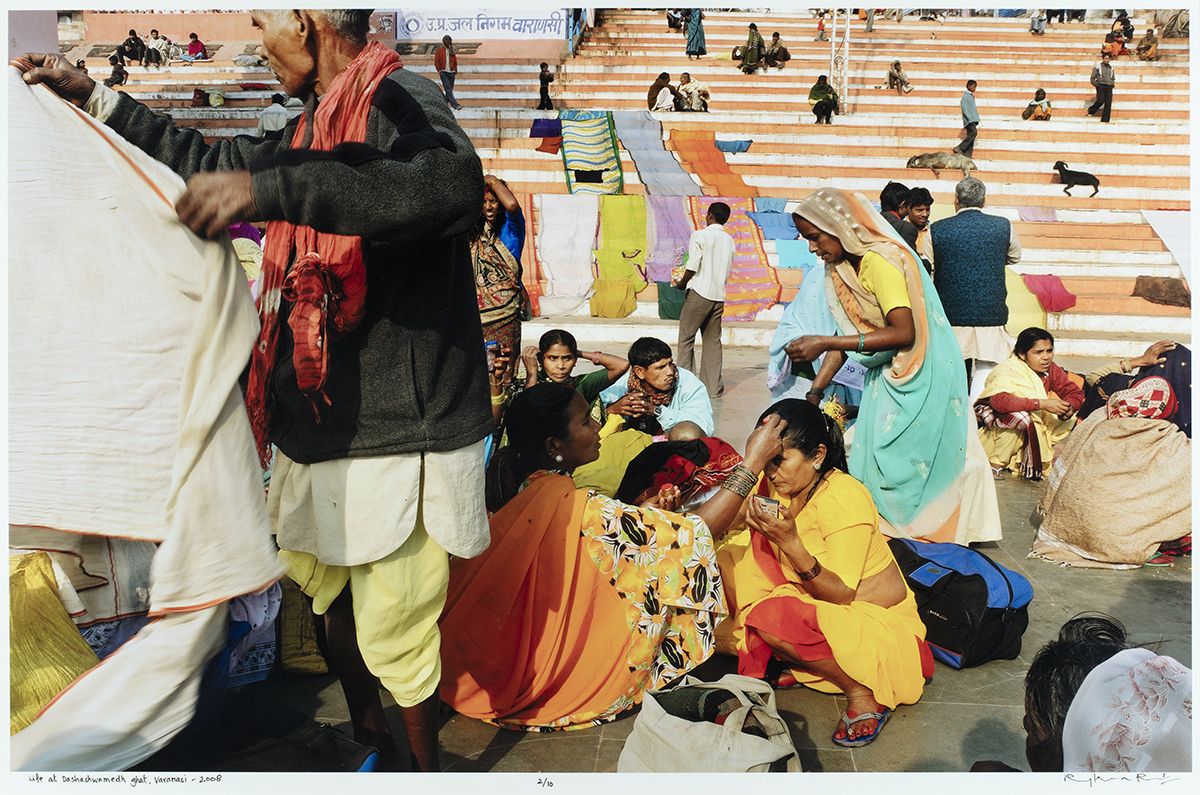

Mural at the Shaheen Bagh protest, New Delhi. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

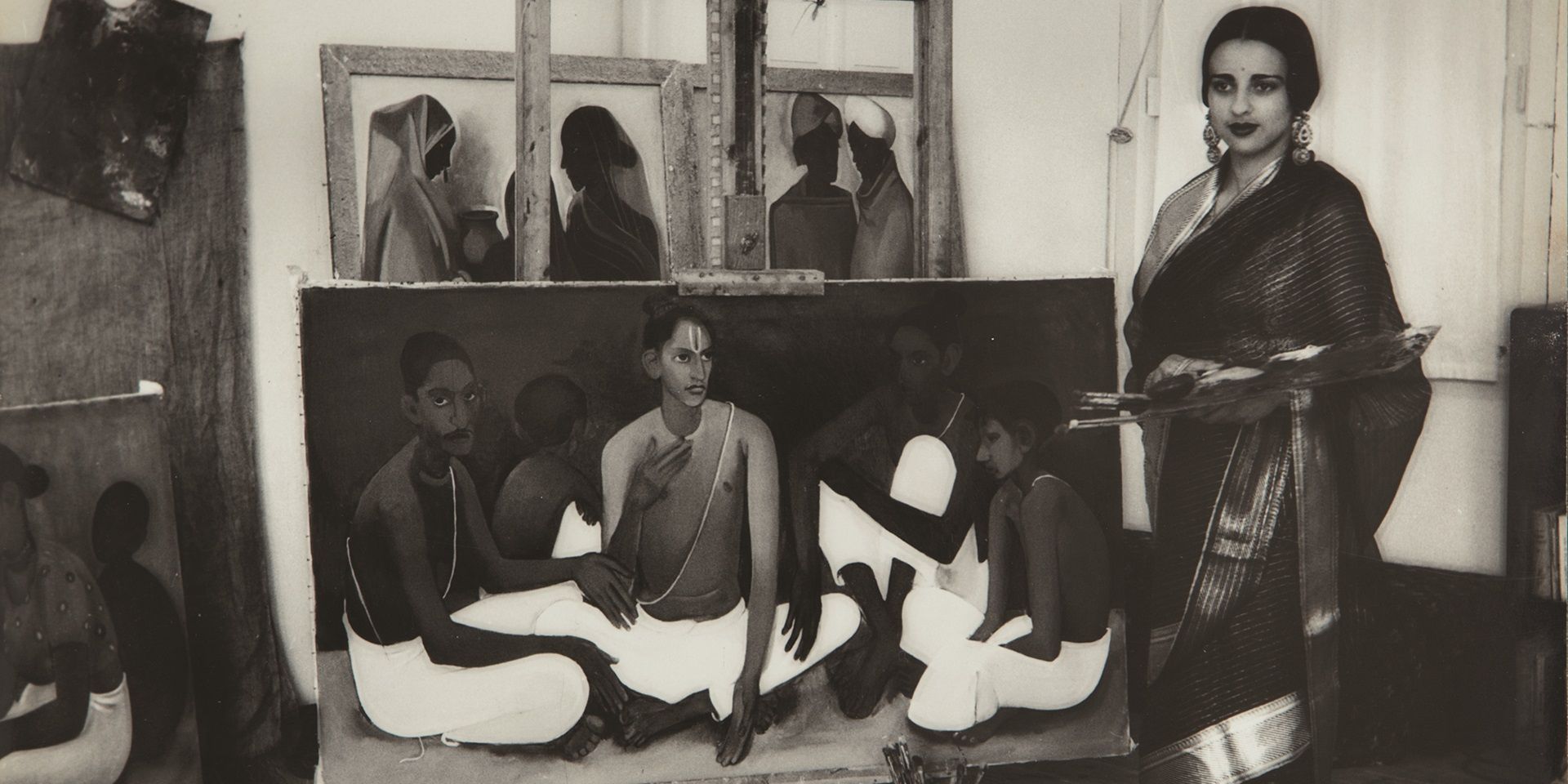

The artist as secular-citizen is, of course, an older formulation…something that Geeta Kapur talks about in her landmark essay, “Secular Artist, Citizen Artist”. When she makes the argument about the secular artist, it is from a vantage position of modern and contemporary art. One of the positions that we were trying to complicate was the readily-given equation between the artist as a modern citizen-subject, and secularism as a larger cultural and political ethos. It would seem that the worlds of modern and contemporary art were, by definition, premised on an institutional and professional world that is innately ‘secular’. That is a position that the art world has resolutely held on to, especially when artists have come under severe attack—M. F. Husain being the best case. What needed to be confronted was how easily the art world’s defense floundered, making artists pay the price, disabling a star artist like Husain from ever returning to India. It has long been assumed that even if religious themes were to enter the repertoire of modern and contemporary art (as they regularly have), the artists remained ensconced in a safe, secular habitus of the art world. But the secular as a guard and guardian of the sphere of modern art has repeatedly come under threat across the national borders of South Asia, with Sadequain in Pakistan, with Husain in India, and with many others. The presumed secularity of art has been constantly thrown into question, particularly with the rise of the Hindu majoritarian government in India.

|

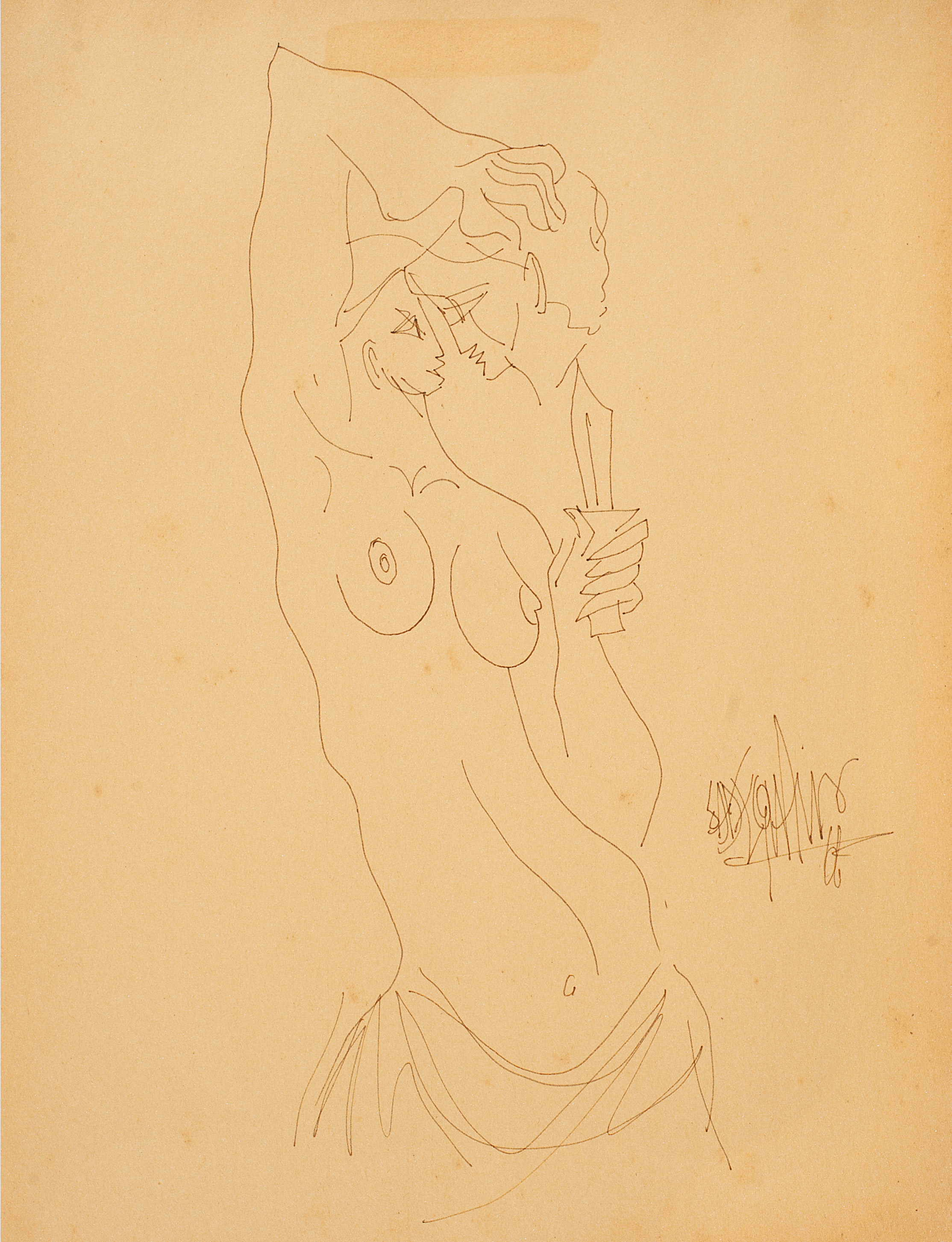

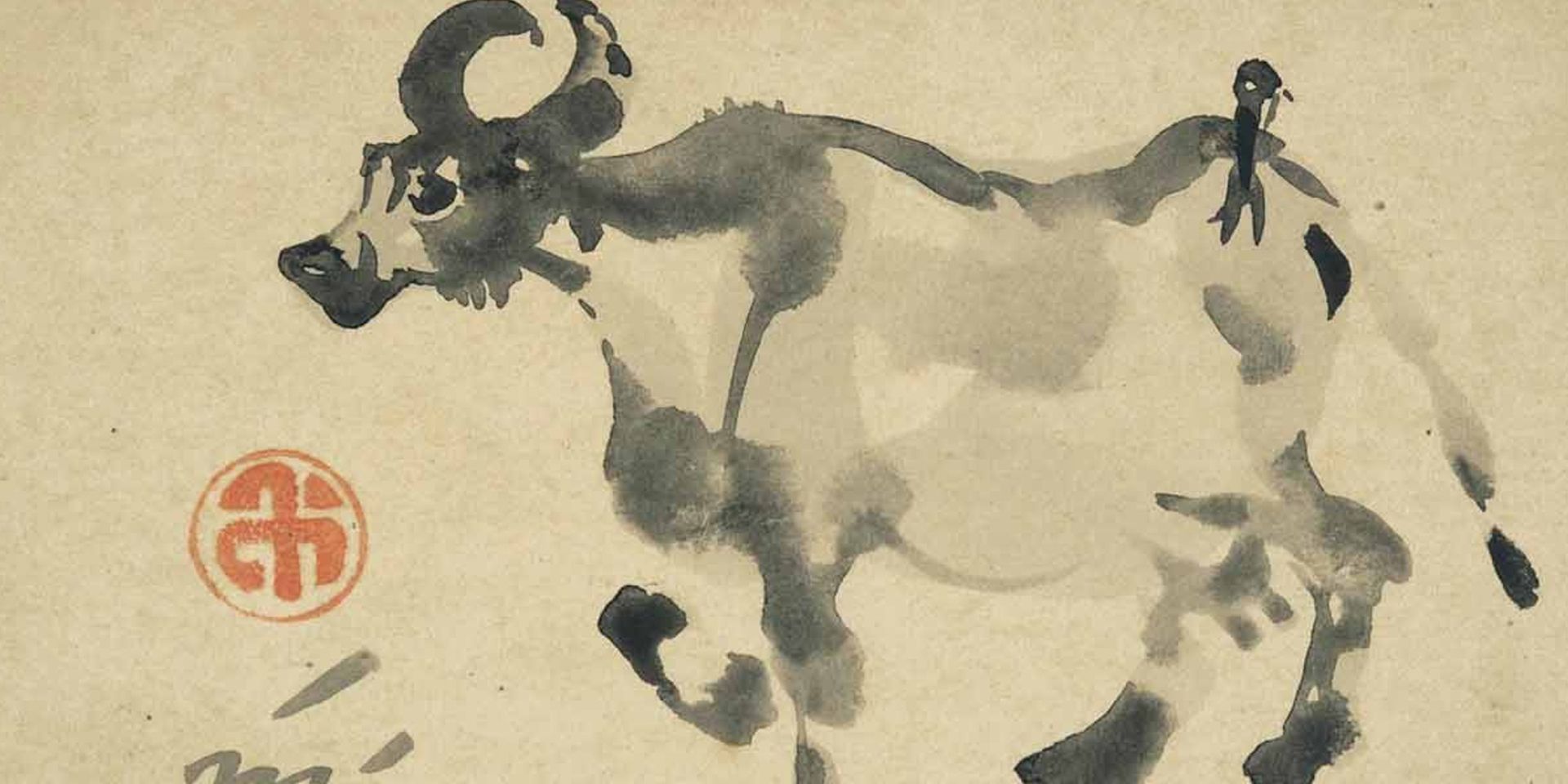

Sadequain, Untitled. Collection: DAG |

That was one premise that we felt needed critical interrogation. Another was the assumption that it is only a political Hindu right that is complicating the story and that, outside this majoritarian political compulsion, artists are by definition secular. If this is so, then we need to ask—why did the art world lose the battle and so easily forfeit its secular grounds? Why is the art world today so ready to jump into a 'Mann ki Baat' exhibition? The question is not just about state patronage of artists but also about their personal beliefs and the nature of their professional space. Therefore, a discussion of the constraints and contradictions of that space of the profession and practice of contemporary art does fill up a large section of the book, especially in Karin Zitzewitz’s and Zehra Jumabhoy’s essays.

|

Sambandar, India, Tamil Nadu, Chola period, bronze. Displayed at Linden Museum, Stuttgart, Germany. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Q: How would you describe the ways in which the art historical discipline has sought to question the binary between a religious icon/image and an art object?

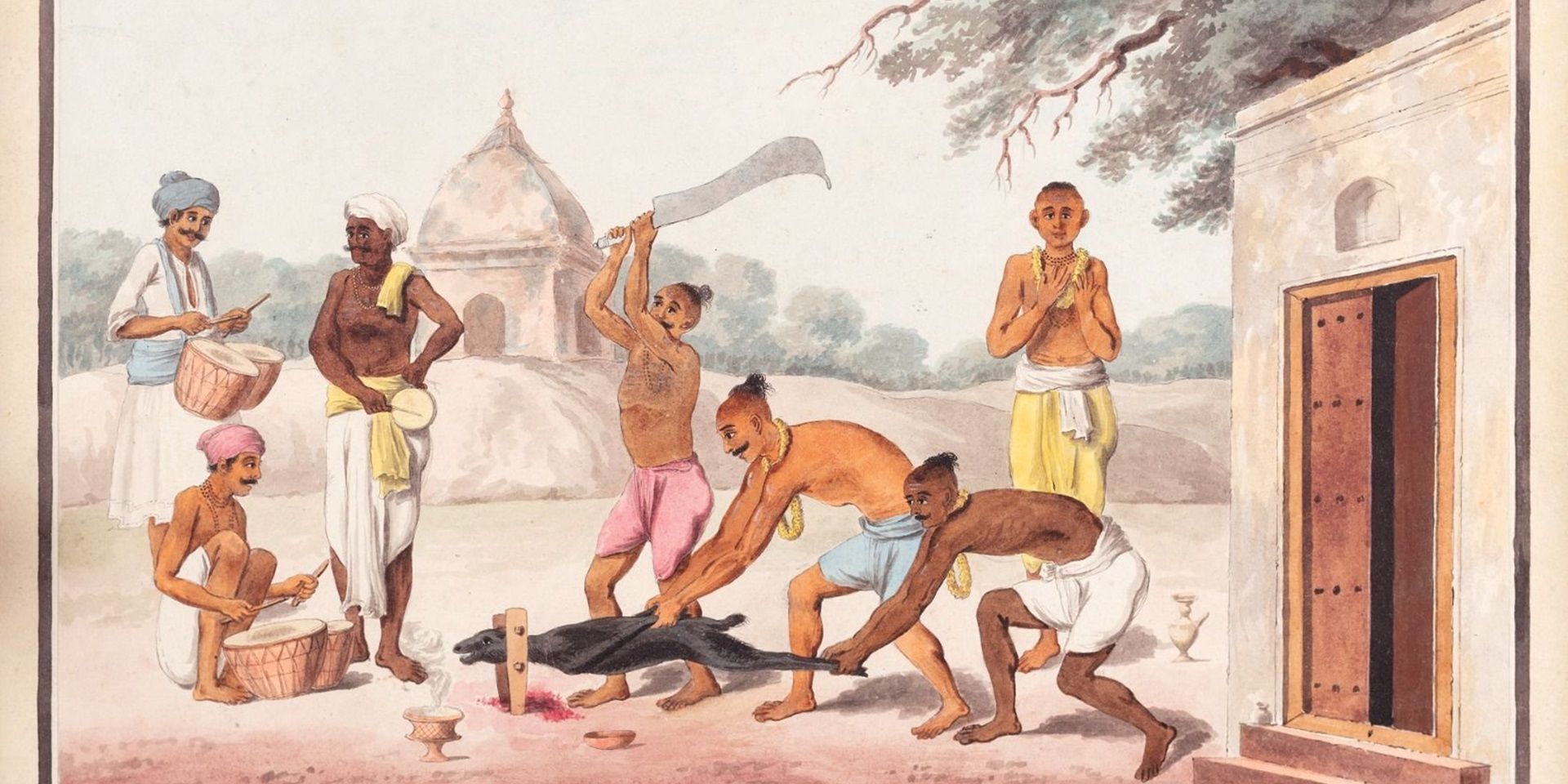

Tapati Guha-Thakurta: The book addresses the fraught place of the secular within the larger discipline of art history, particularly South Asian art history, where the great traditions of architecture, sculpture and painting were all once part of a religious dispensation. So, whether it be sculpture, temple architecture, or even various kinds of manuscript painting, religion played a definite role. While Mughal art was seen to be secular, or pre-secular, a lot of people still consider that this school, along with the other great schools of Indian art, emerged from essentially religious traditions. The essence of the discipline of South Asian art history lay in the way it understood its objects through the lens of religiosity. Can you really appreciate a Chola bronze without going into the iconography or the text, or appreciate temple sculpture without understanding the context behind its forms and uses? The main challenge lay in setting apart its disciplinary tools from religious studies and repurposing the religious object into a subject of aesthetic and art-historical analysis.

|

The Didarganj Yakshi, now at the Bihar Museum in Patna, was displayed as ‘Goddess Holding a Fly Whisk’ at the 1985 The Sculpture of India exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons. |

|

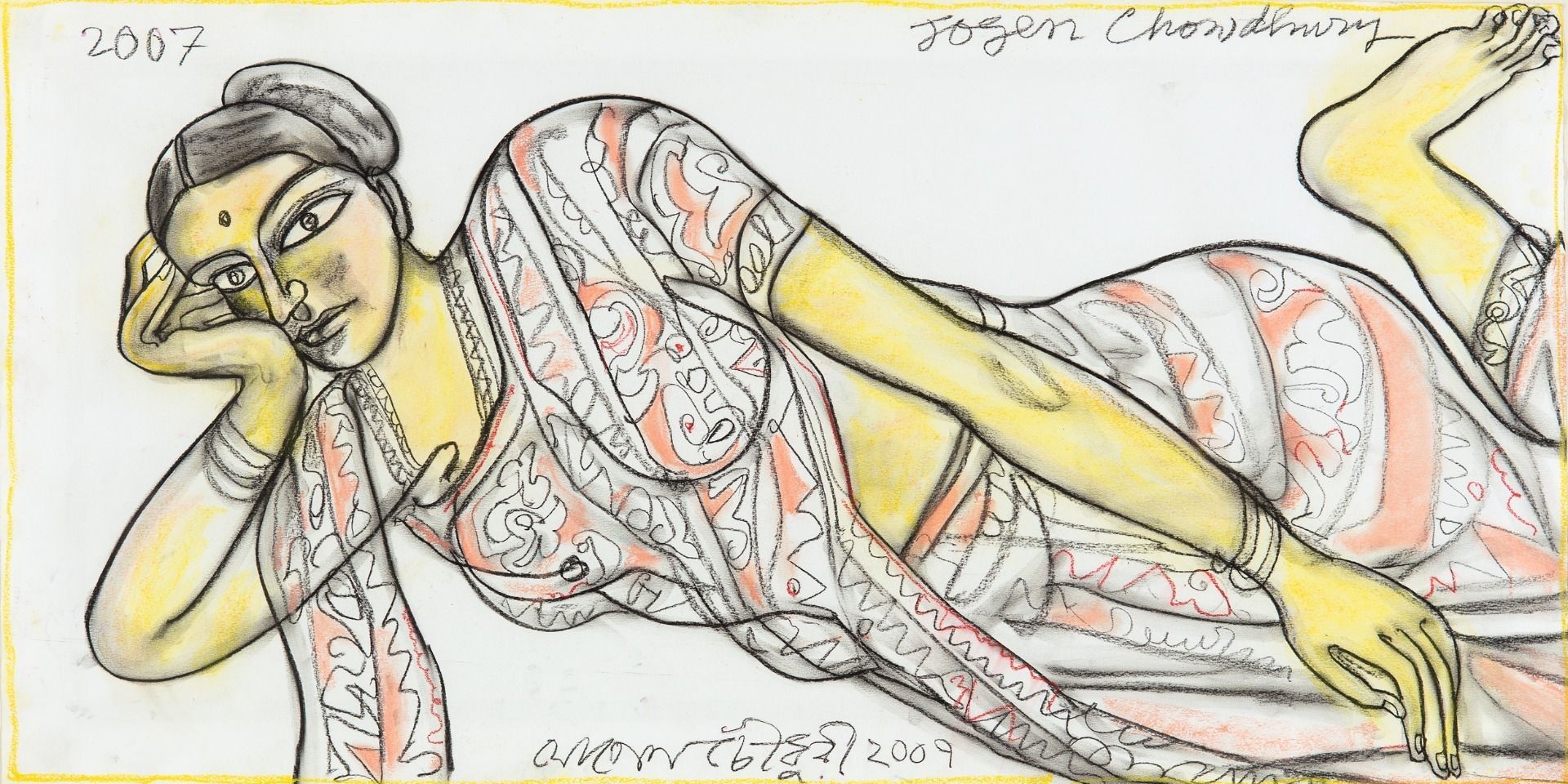

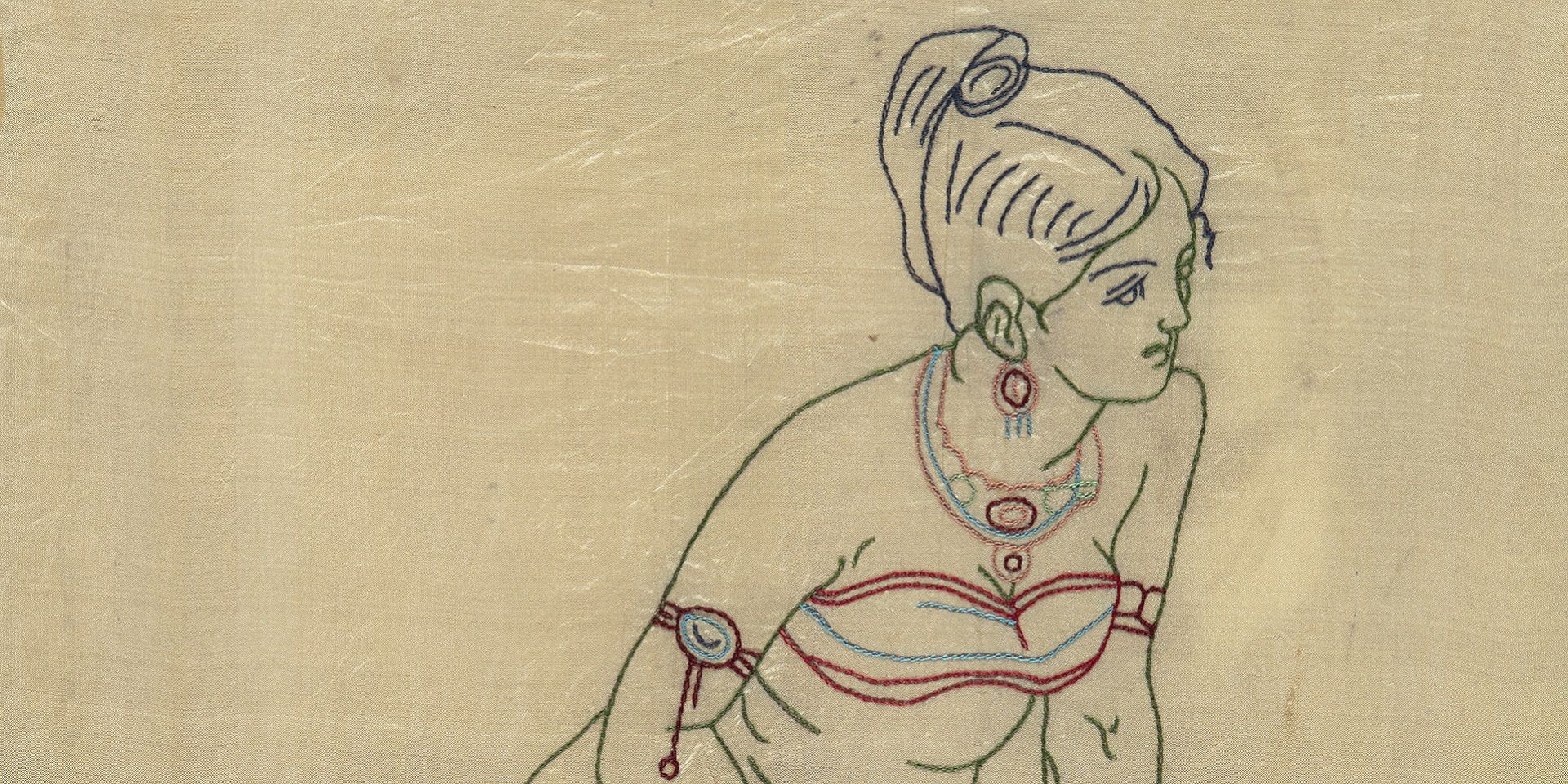

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, watercolour on cardboard. Collection: DAG |

Once you begin to complicate this disciplinary divide, and also the divide between the West and South Asia, to say that even Western art history essentially has Christian art at its core, you introduce a much-needed complexity to a seemingly secularized narrative. I take my cue here from Hans Belting’s fantastic book, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, that takes off from the late Renaissance period, before which art was conflated with various functions and powers of the ‘image’. So, the question that we might ask ourselves is: when was India’s ‘era of art’? Does India have such a defined historical period when once-religious, ritual or ceremonial objects become ‘art’? This was the other aspect of the secular that we wished to engage with. Where is the locus of the secular within the discipline of Indian art history? How do we understand the ways in which Indian painting, sculpture, architecture and crafts have continuously negotiated the divide between not just fine arts and decorative arts, but also between the religious and the secular. It is in these two areas, within the discipline of South Asian art history and the profession of South Asian contemporary art, that the place of the ‘secular’ and its polyvalence has been opened up for repeated interrogation by the authors and editors of this book. Together we look as closely into the modern conception of the secular as into the modern epistemology of art as it is made to encompass a series of past products, cultures and contexts.

It is also important to think about the place of the secular in countries which do not have the conception built into their constitutions. For instance, how was secularism imagined within the modern art worlds of Pakistan and Bangladesh? The guarantee of the secular is as much at threat in these countries, as it is in an India governed by a politically religious majoritarian group. In the looming shadow of the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act, which has thrown asunder the constitutional mandate of secular nationhood, the questions of art practice and art history writing need to be addressed anew.

|

Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, Chromolithograph on paper. Collection: DAG |

Q. How did you and your co-editor, Vazira Zamindar, frame your approach to these broad questions of the secular—a complex term with its own history of use in the subcontinent—intervening into the sphere of art practice today?

Tapati Guha-Thakurta: To respond to this, I will read out two sections from the Introduction which might be interesting. One looks at the Shaheen Bagh protest site and its public art.

’In one of the murals of Shaheen Bagh, the demand is captured by the depiction of the Constitution as a tangible object in the form of a large book that is held up to the people in the hands of the hijab-wearing Muslim woman, where she might be expected to carry the Quran. It becomes an article of secular faith. If secularity and faith could be regarded not as far apart as we presume, then perhaps it is in this mutating domain of critique and conviction that our inquiry can begin on the secular solidarities of art, in situ with the mural at Shaheen Bagh, and more broadly, the South Asian image worlds.’ (p. 4, 'Introduction')

Let me move from this section largely written by Vazira to this next section by me:

’Tried and tested ad infinitum, ‘the secular’ may seem a rather tired term today. Yet, in its very tiredness, it has left a lengthening shadow that refuses to go away and keeps drawing us into its trail. From a different place of conviction, Talal Asad once noted, it is precisely ‘because the secular is so much a part of our modern life, [that] it is not easy to grasp it directly. I think it is best pursued through its shadows, as it were.’

I hope that the book addresses the context of the present as much as the context in which the conference emerged. But I think 2019-20 gave a different twist to the book, and the introduction did emerge in the shadow of this newly re-inscribed landscape of Hindutva that was being physically inscribed through replanted temples, as Kavita Singh’s essay demonstrates. The rebuilding of the Ram temple at the site of the demolished Babri Masjid in Ayodhya has, in fact, strengthened such a practice and narrative of reclaiming Muslim religious sites as 'originally Hindu'. So, as we were finishing the essays, the question of finding shivlings inside mosques, in the Gyanvapi Mosque in Varanasi and the Shahi Idgah in Mathura, were being discussed, with the courts continuously allowing such investigations to proceed. Thus, it seems that the threatened historical monument, especially the Islamic monument, remains as vulnerable as the Muslim citizen and the Muslim historical past in India.

|

Abanindranath Tagore, Ganesh Janani (detail), 13.3 x 8.0 in., 1908. Image courtesy: Indian Museum and Wikimedia Commons |

Q. Zehra Jumabhoy’s essay, ‘Making Place for People? Geeta Kapur, Secular Nationalism and ‘Indian’ Art’, argues that in today’s sociopolitical milieu, older practices such as the Sufi-Bhakti valorization of national-sacred-secular art is an inadequate critical tool. How do you think art practice can be vigilant in drawing upon the historical past, especially on syncretic modes of thought and existence, without unwittingly succumbing to the trappings of a ‘soft’ religious-nationalist narrative?

Tapati Guha-Thakurta: Let me first pose a simple question: what place does religious devotion or religious iconography have in contemporary art? We know that, while artists may well have been divided on the issue, religious iconography continued to play a powerful role in both market-produced varieties of Indian art and in the modernist and more contemporary schools of art. Religious iconography is such a rich part of everyday Indian visual worlds, and there are so many ways modern artists have embraced and played with this inheritance of iconography in high and popular cultures. For a long time, there was a reluctance in certain circles to address the integral place of religion, devotion, affect, belief, faith in everyday worlds, that both upper-class professionals and other social groups inhabit. I think that is a huge lacuna in coming to terms with questions like—Can I be religious and still essentially be a secular person? Must the secular necessarily be devoid of devotion and affect? How do artists and art historians work across the porous borders of the religious and the secular, or equally the non-religious and the non-secular?

|

Chhatrapati Dutta, In the Calcutta Alleys, Acrylic on glass (reverse painting), 23.5 x 17.5 in., 1989. Collection: DAG |

|

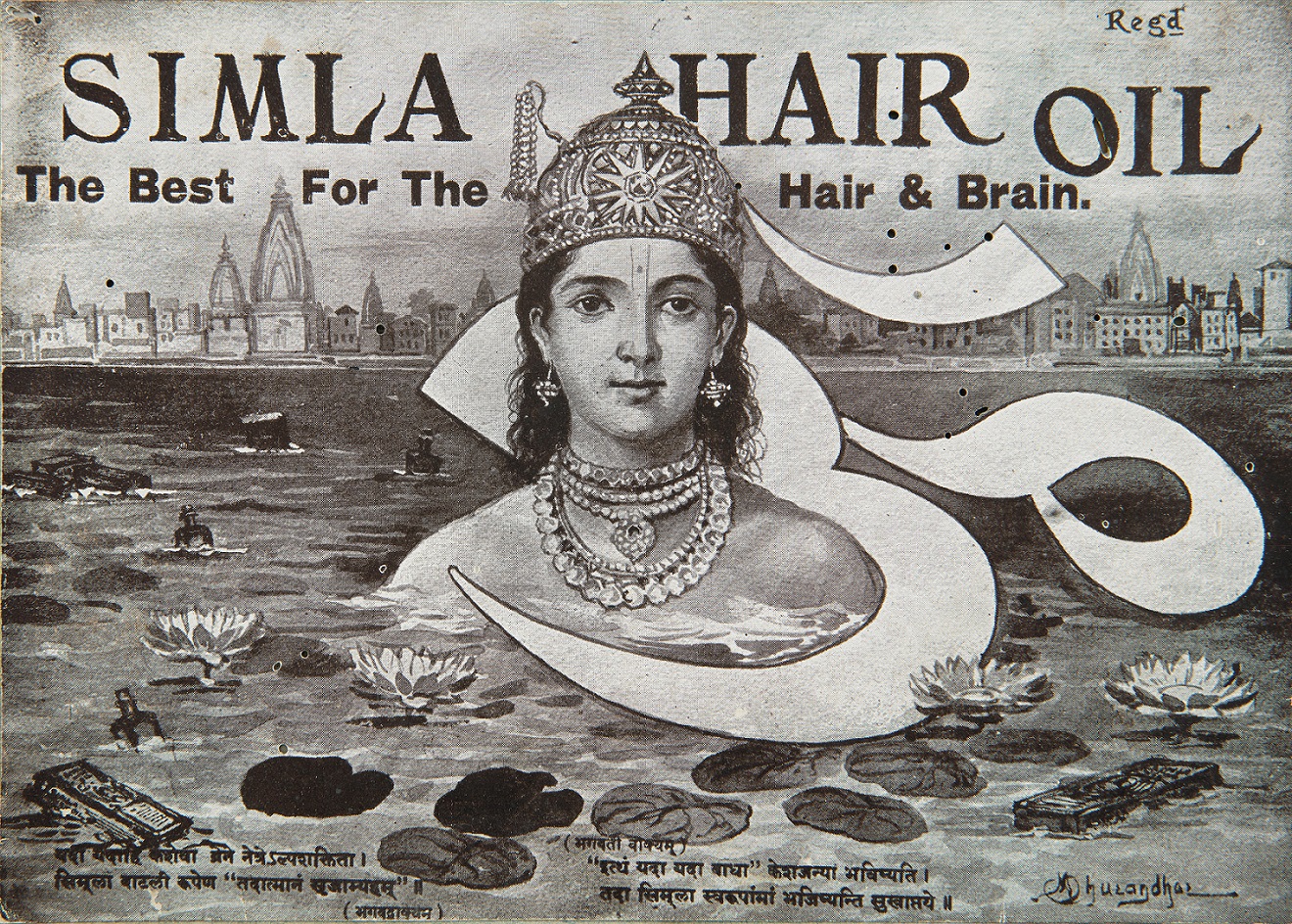

M. V. Dhurandhar, Untitled. Collection: DAG |

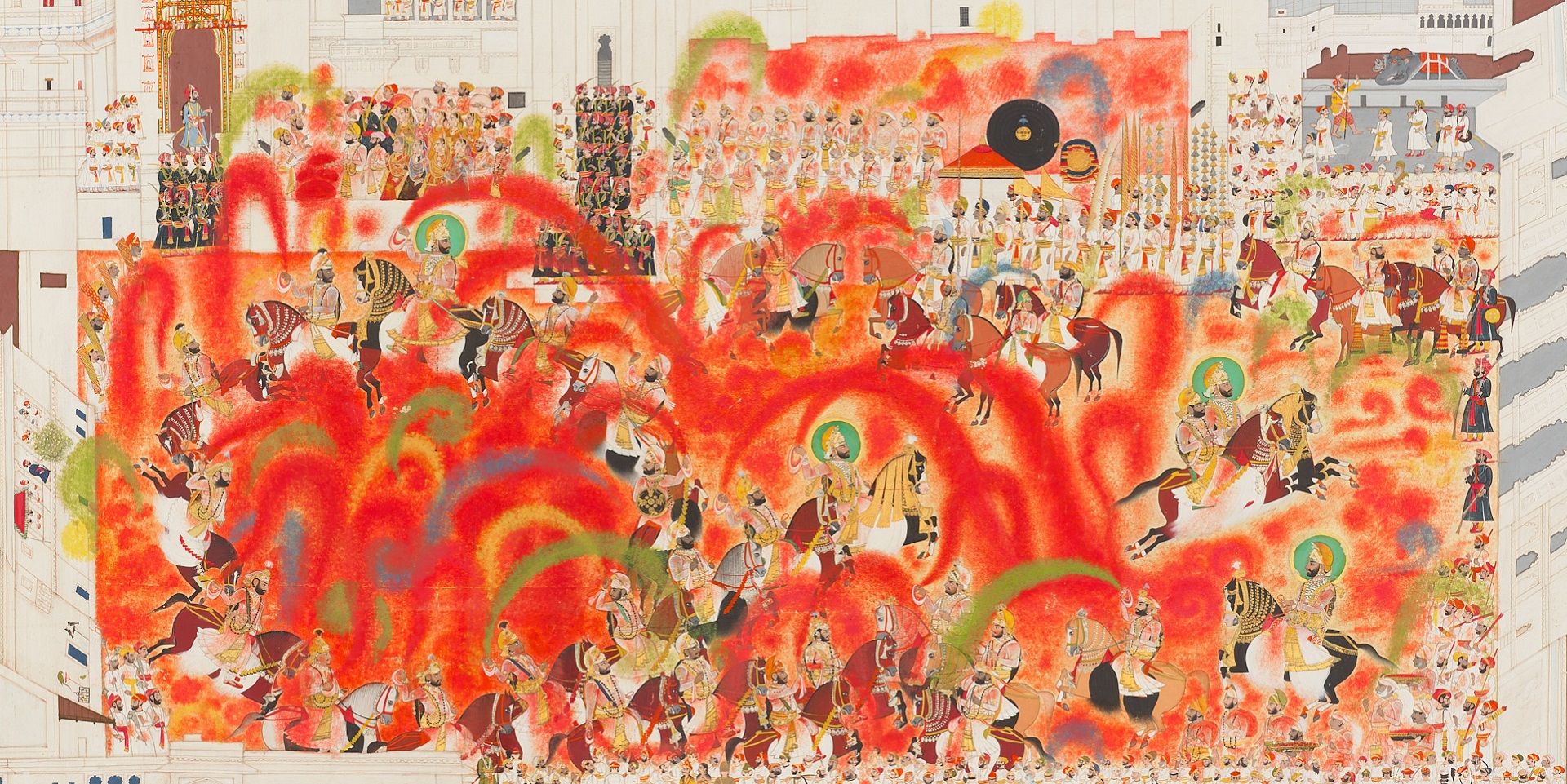

These were some of the questions waiting to be grappled with, even as we realized that there were no easy answers. A lot of the early history of modern Indian art has instances of the religious freely entering its domain and transforming it. Raja Ravi Varma’s works were the ones that most promiscuously crossed these borders. The moment his paintings of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and those of Lakshmi and Saraswati, moved from palace halls to become popular prints, Ravi Varma forfeited his status as an artist, in a way that the Bengal School artists never did. Nandalal Bose, for instance, often drew and painted Kali and Abanindranath painted the figure of Ganesh-Janani. The Bengal School’s work was full of religious iconography which was being reclaimed as tradition rather than as religion. We can continue to think about how far religious iconographies have animated modern and contemporary art, and how securely these were accommodated within the secular dispensations of art. The lines determining when and how a work journeys from an artistic to a devotional sphere or vice versa are always slipping and turning.

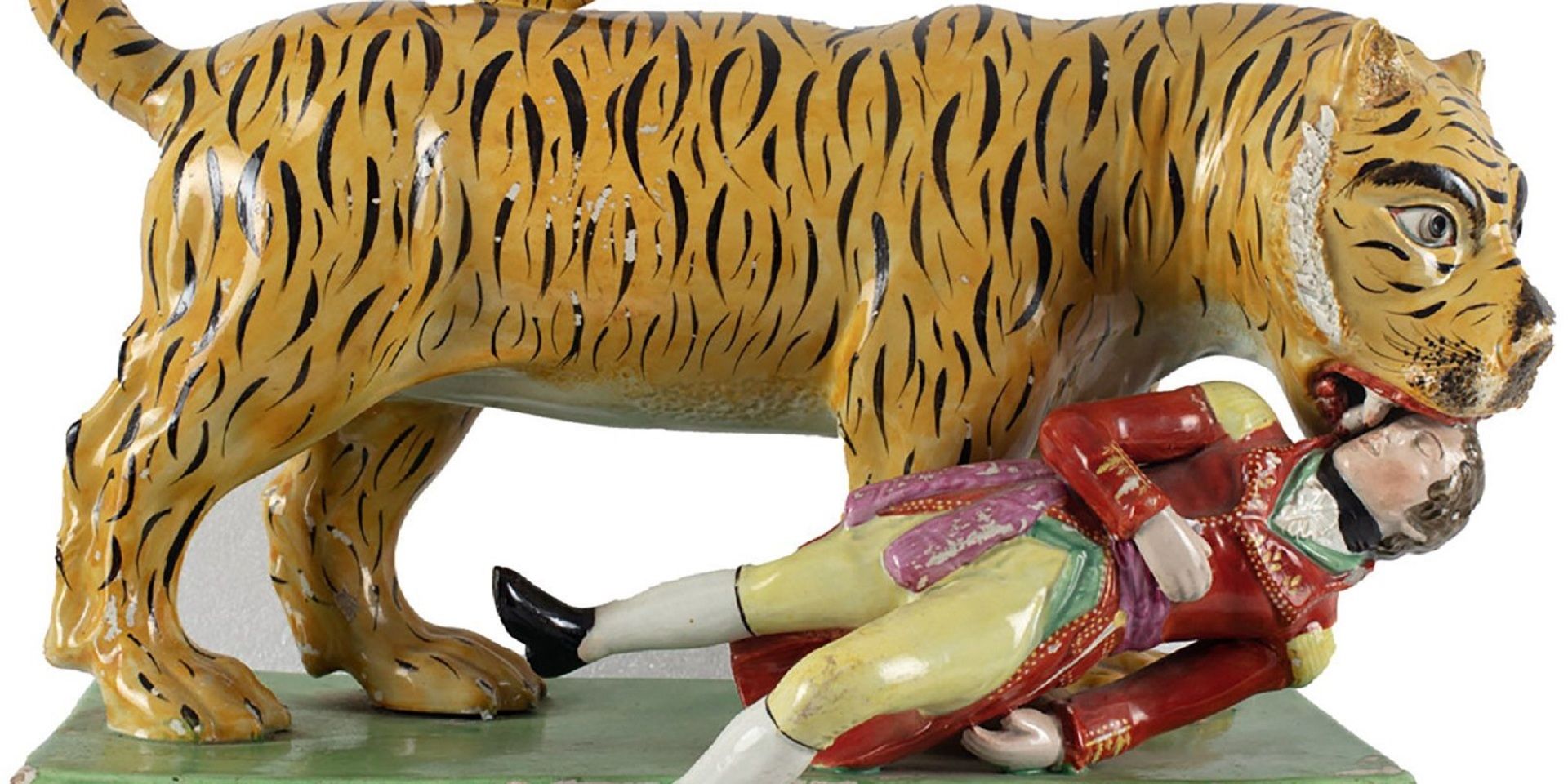

Much of the debate regarding Husain was hinged on what he had said: if you were to take iconography as a cultural possession which all artists can access, then ‘India’s 5000-year-old culture’ was his inheritance as a Muslim. To name an artist, a modern artist, as ‘Hindu’ or ‘Muslim’, was itself seen to be an impropriety. Think of the way K.G. Subramanyan takes the image of Durga and uses it as a playful icon, irreverently, like he does with Hanuman and Shiva. There is so much of that in our popular tradition. That is why it is so interesting that ultimately the gods are not just humanized, but also become part of the foibles and vanities of contemporary life. Think of Durga in advertising. In some ways, there existed a space where the right to be impertinent, the right to be playful and subversive with your gods could be exercised. Those are still the terms in which Indian religious iconography continues to claim a very powerful space in art as in popular visual culture.

|

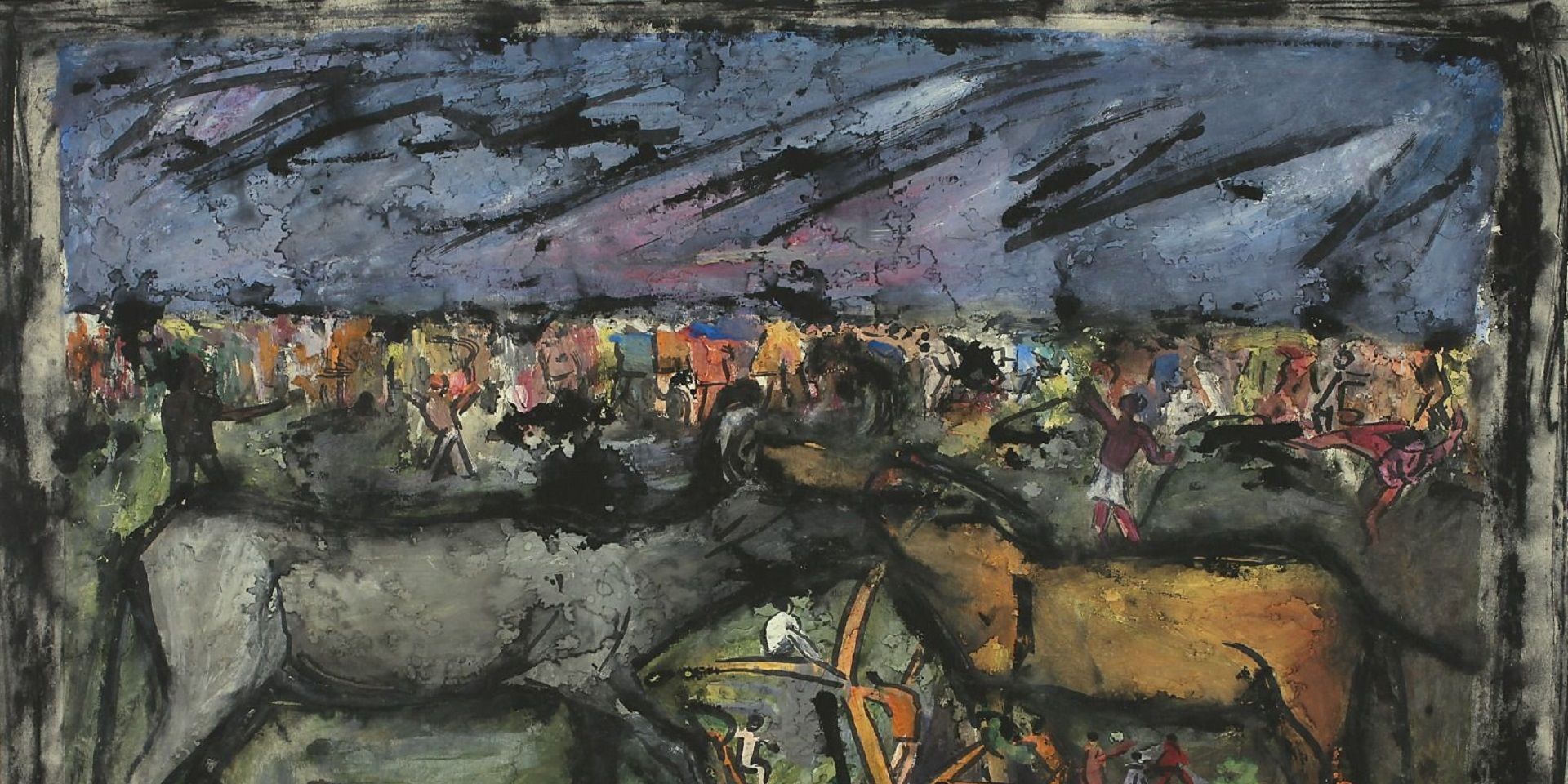

M. F. Husain, Yudha, Oil on canvas, 48.0 x 48.0 in., 1971. Collection: DAG |

To now come more directly to your question about Zehra Jumabhoy's article. She is referring to Nalini Malani’s works in particular, where figures like Kabir become very important. There were several like her trying to reclaim figures who did not belong to the religious orthodoxy, or who broke religious boundaries. Lots of artists and intellectuals feel that the best way to address cultural difference is to talk about how the cultures of accommodation (especially of different faiths) affect our understanding, and that, in some sense, there was a culture of living together which needs to be highlighted. Zehra is questioning how these tropes of mixing and cohabitation become a comfortable zone, where we move outside the hard boundaries of religious establishments and recover places of shared beliefs and imagery across religious divides. Here, certain syncretic interfaith traditions of art, literature and music, exemplified by figures like Kabir or the mystic sects like the Bauls, come to be celebrated by intellectuals. Zehra places under scrutiny these modernist interventions and their strategies of political and cultural mediations. The question is then: what happens when we address orthodoxy in its own terms?

Working in the field of South Asian art as an Indian-Muslim curator, Zehra argues that that this zone of a safe secular habitus has today slipped away. In Karin [Zitzewitz]’s work on Rummana Hussain, the artist is seen intervening as a ‘secular’ figure, rather than as a hijab-wearing Muslim woman. However, I feel that had Rummana been alive today, she might well have worn the hijab as a mode of solidarity and identity. Can we too now reinsert our positions as critic, artist and art historians in a changing political context and reconceptualise Rummana’s art and identity?

Zehra’s critique is aimed at Geeta Kapur, who was in such a canonical position in terms of having defined the avant-garde, the secular, and the political as a mandate. Zehra is asking what happens when that mandate has floundered, and yet artists are still working, still pushing against various political guards. What becomes of the once-secure place of comfort and religious co-habitation? Of course, her aim is not to say that it is time to bring the Ulemas back, but to say that there needs to be an acknowledgement of the limits of ‘Indian’ secularism.

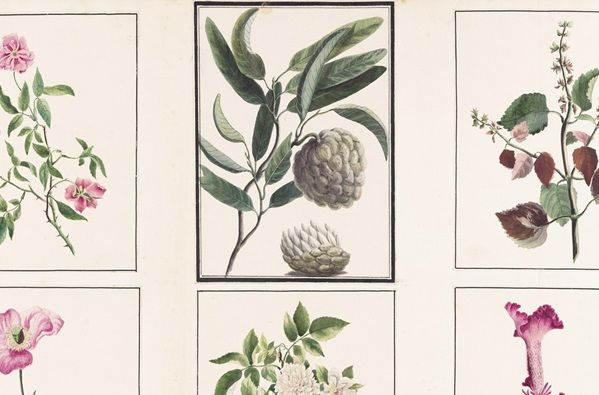

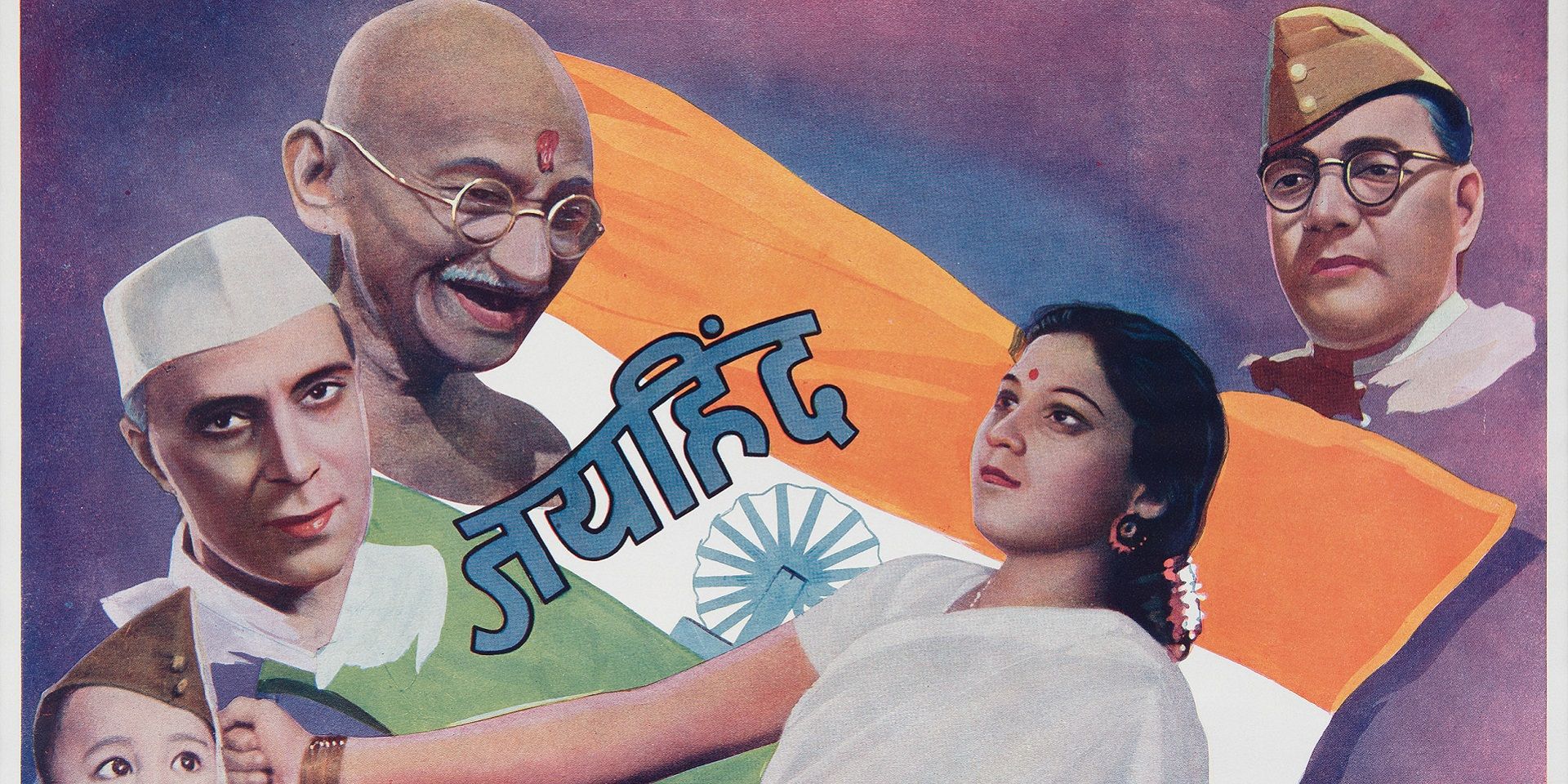

Various litho and oleo, Untitled, offset print on paper. Collection: DAG

On a different trajectory, Kajri Jain's essay confronts head-on the disciplinary divides between art history, religious studies and visual culture, in order to address the charge of the religious image. If something is popular and religious, we are comfortable putting it within the category of ‘visual culture’. While engaging with the devotional life of such images, Kajri, as an art historian, is also deeply invested in employing the tools of the discipline in looking closely at the forms and aesthetics of bazaar prints, which are ephemeral objects of worship. She is not just trying to read these popular images in anthropological terms; she is also trying to examine the disturbance that these images bring within the cloistered walls of art history. Kajri’s larger formulation is to ask what happens when we bring the question of religion, devotion and belief back into art history? And alternately, what happens when we bring the question of art, aesthetics, discipline and profession into works and worlds that we consider as belonging to popular faith? In her view, the overall questions that we are asking in these essays have a relevance not just for art history in South Asia, but for the discipline at large, and for the place of the contemporary across the globe.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

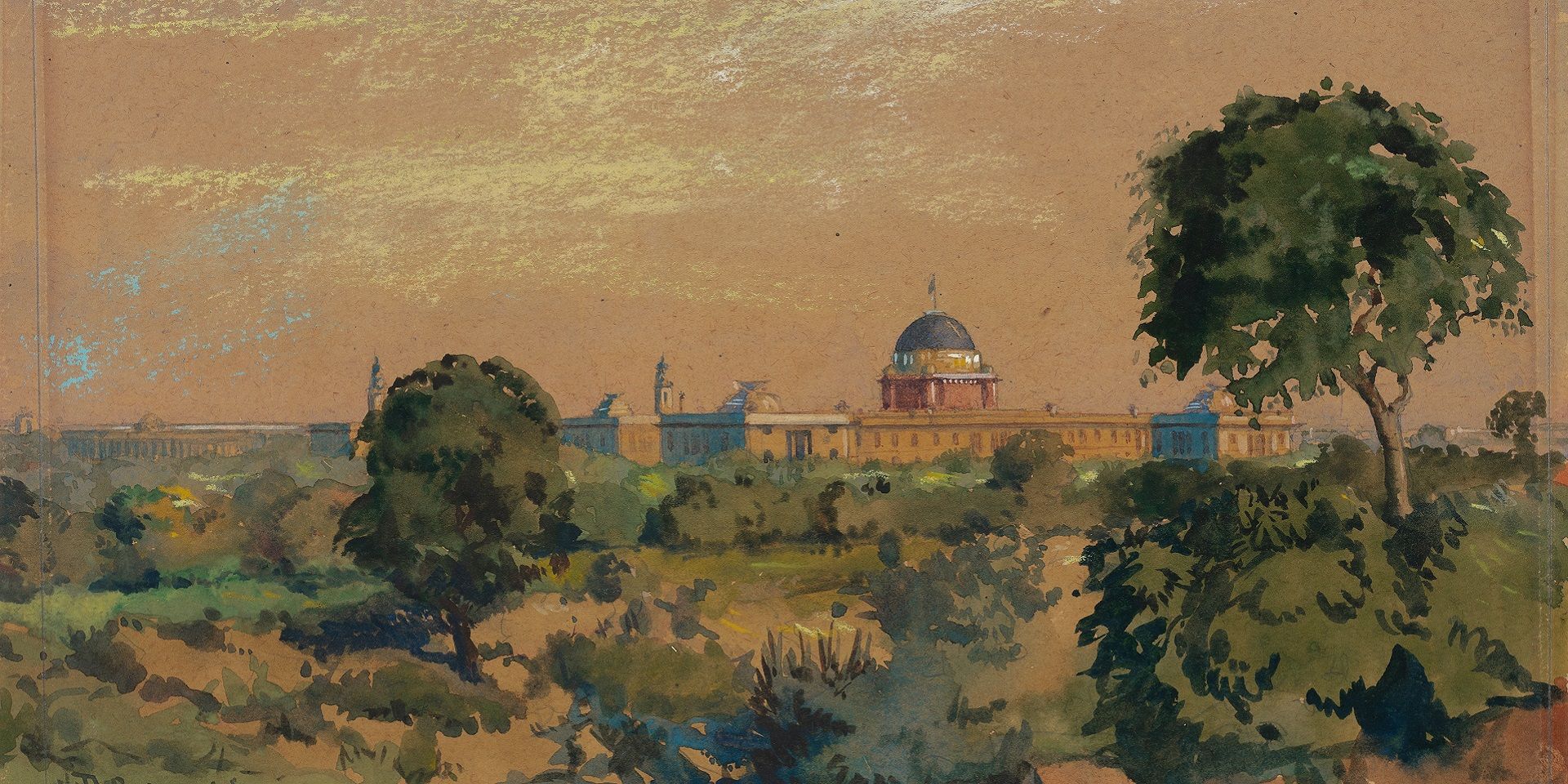

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025