Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

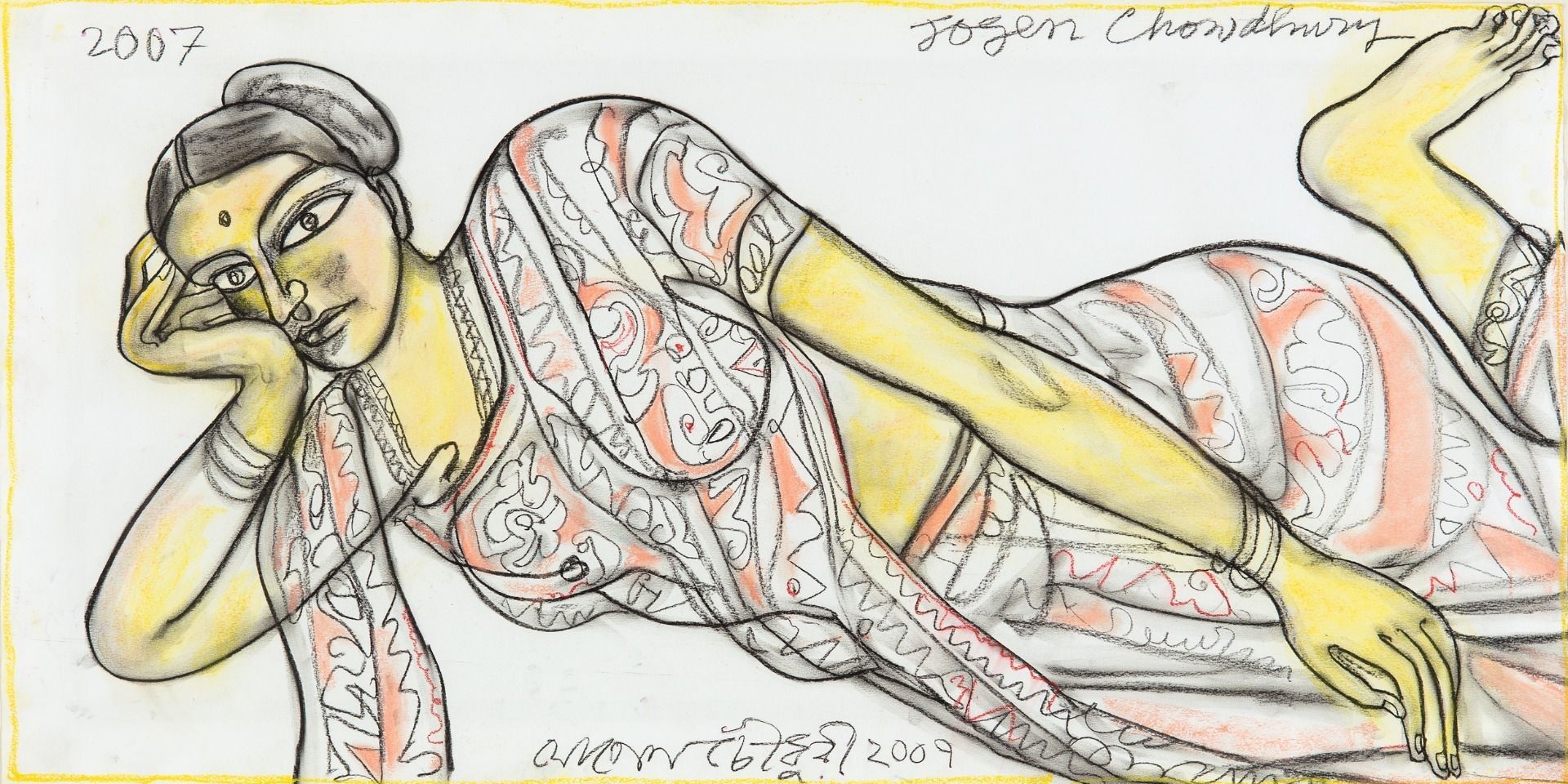

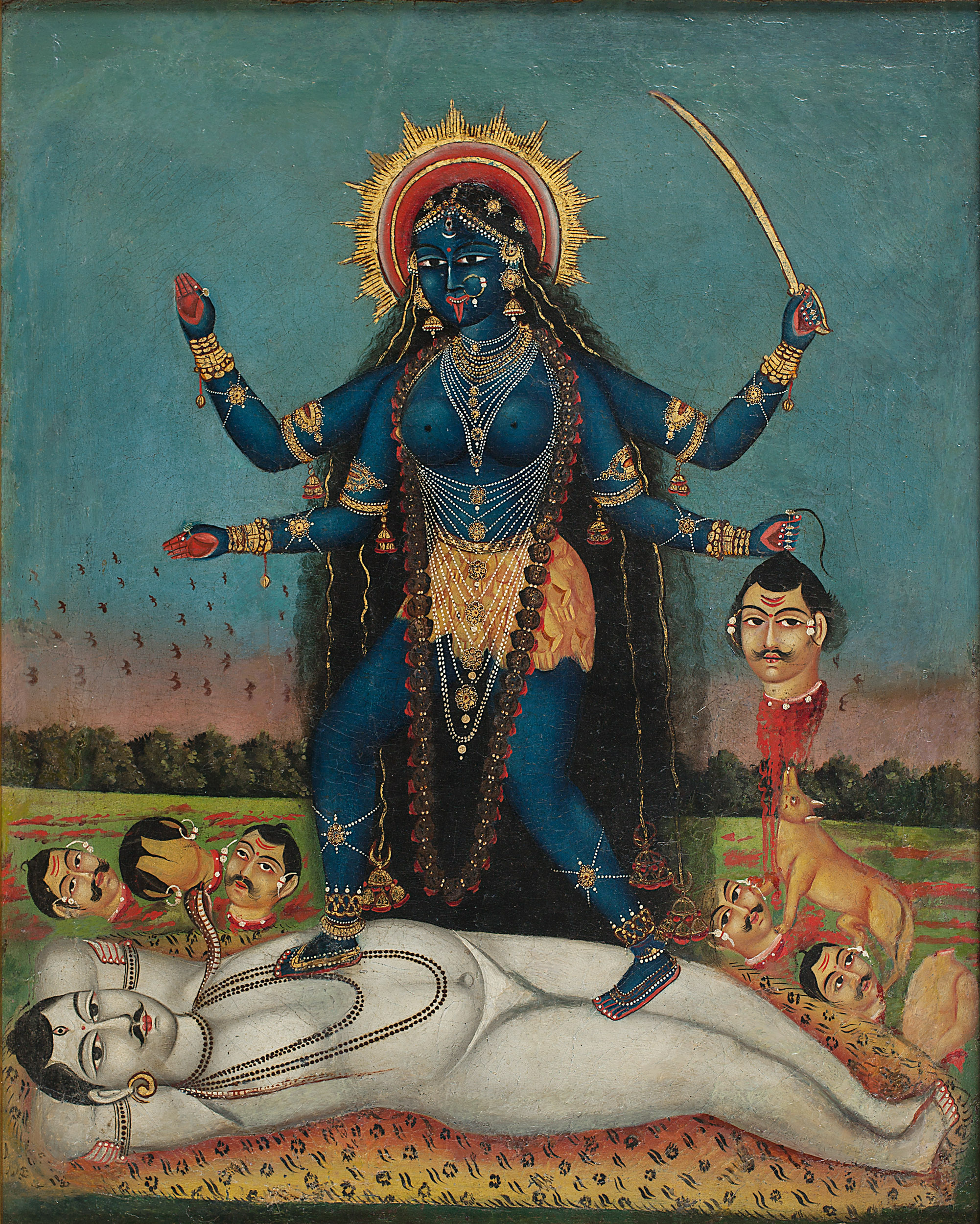

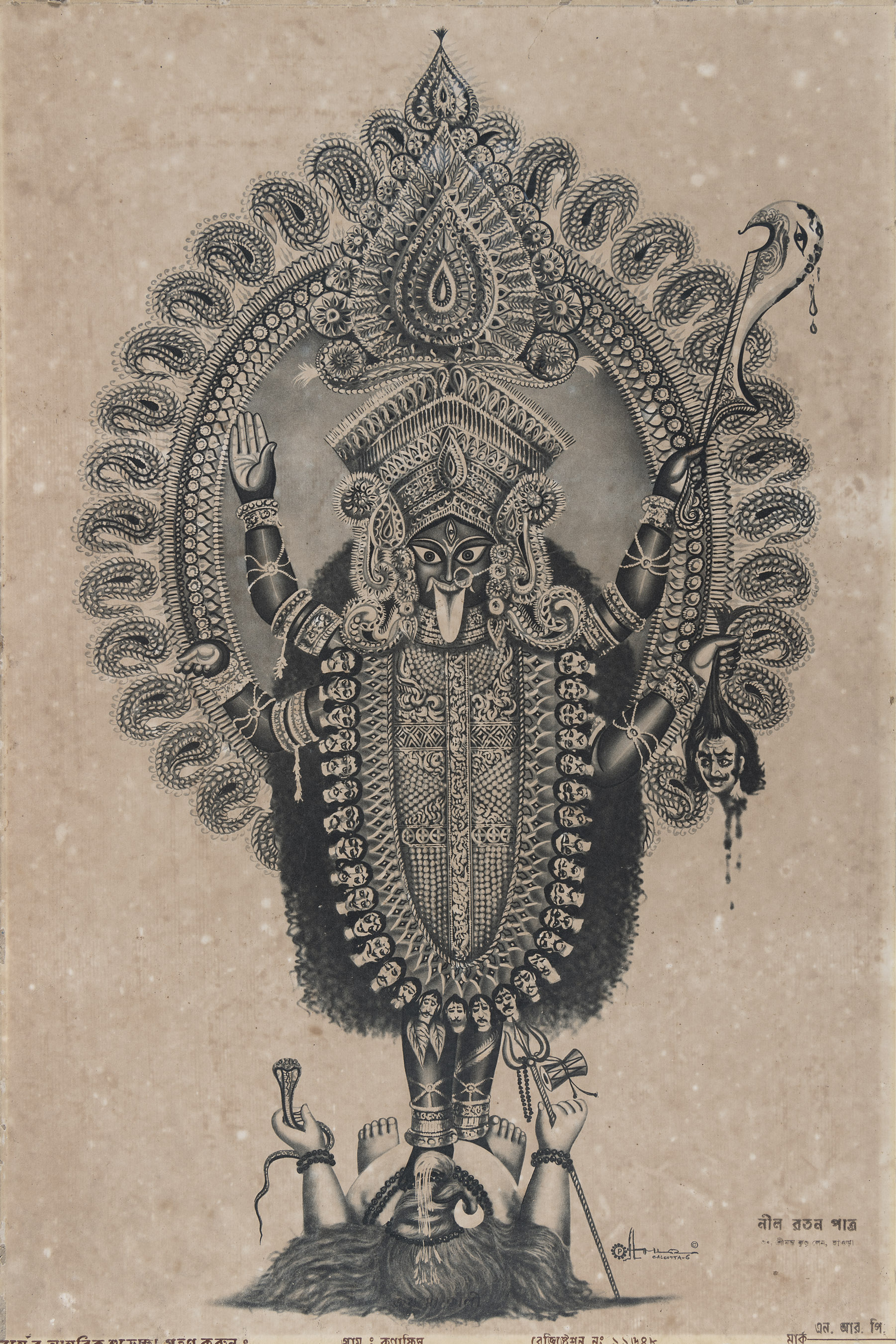

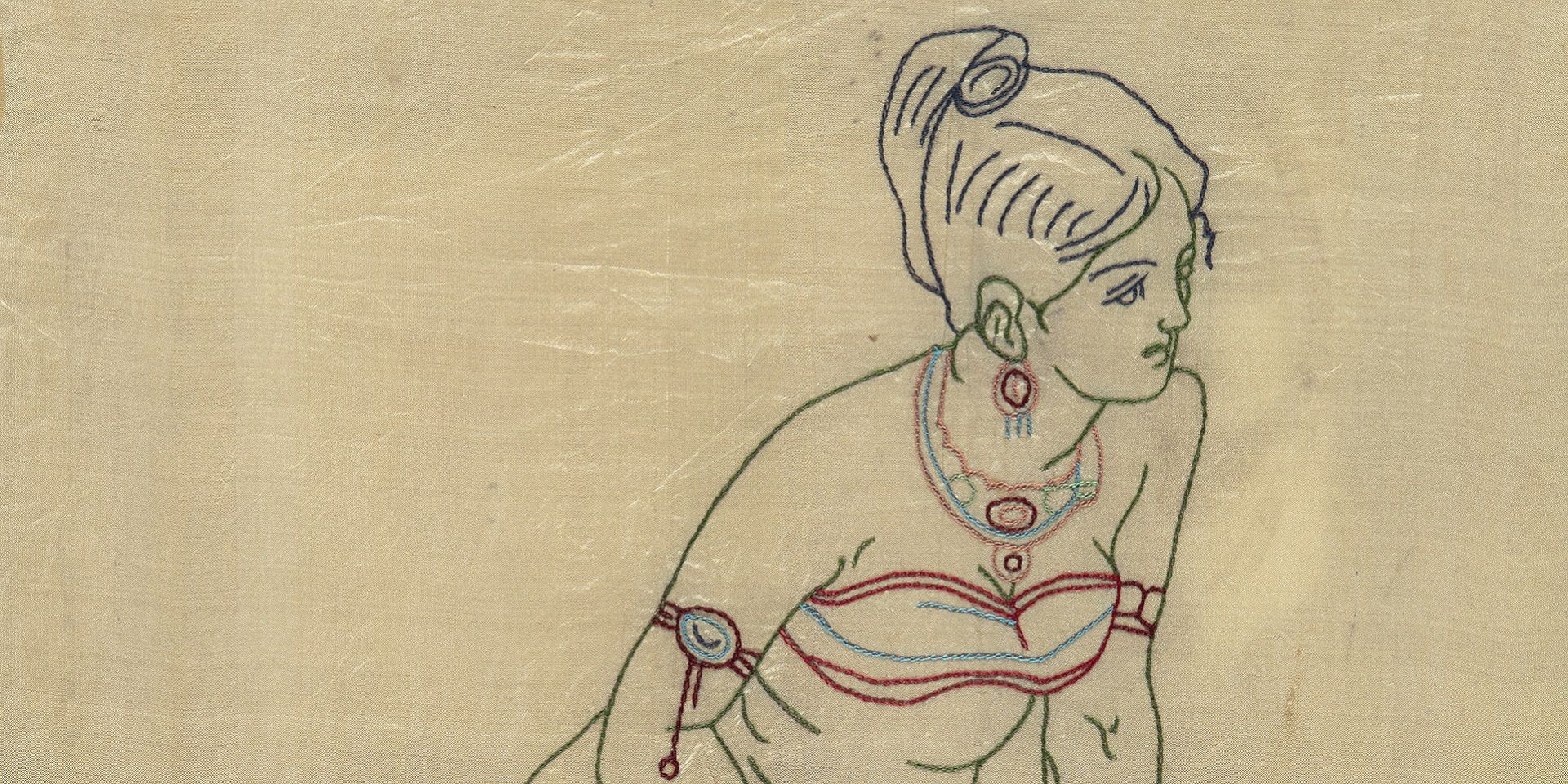

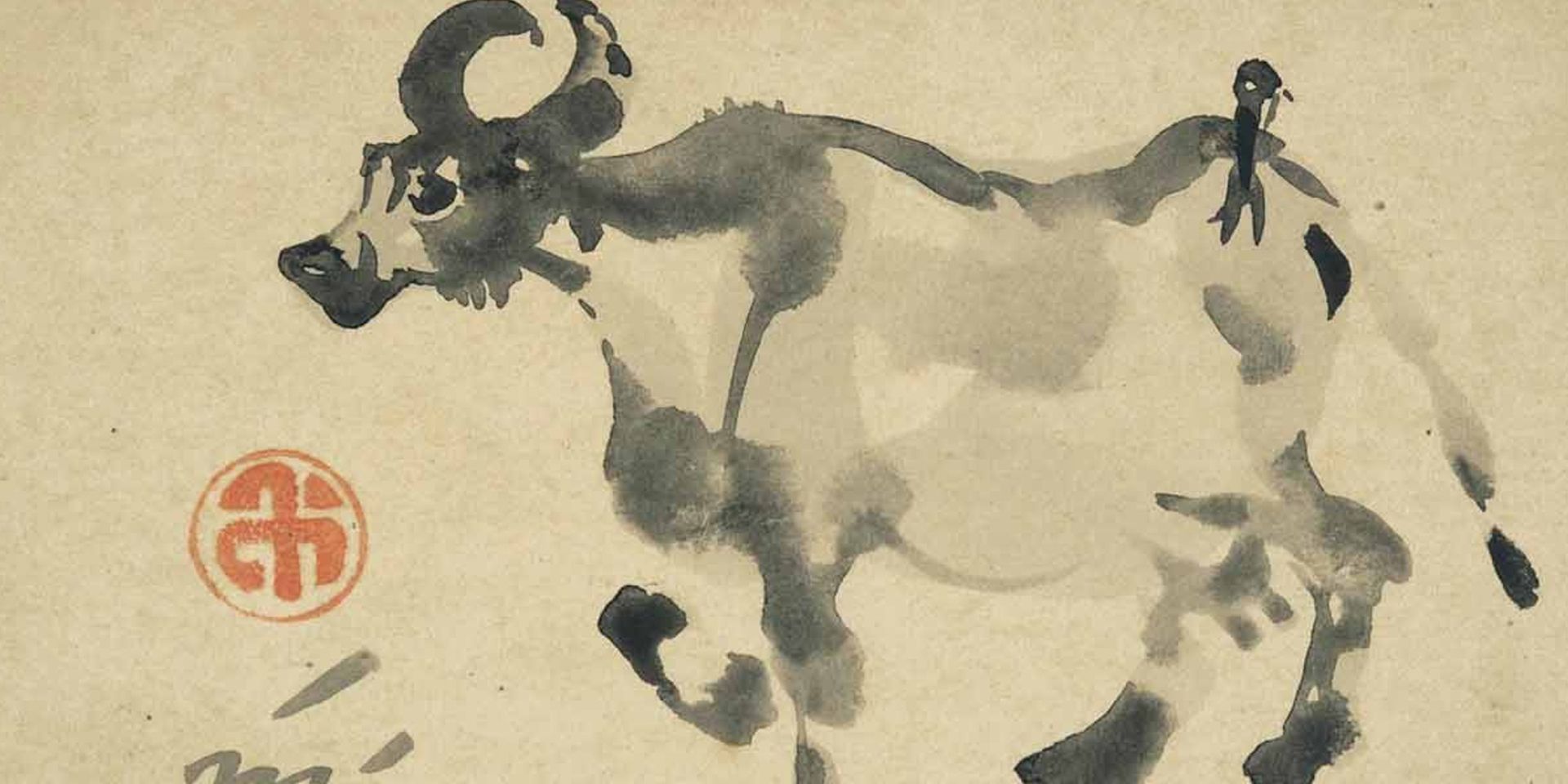

Unidentified Artist (Early Bengal School), Dakshinakali (detail), Oil highlighted with gold pigment on canvas, middle to late 19th century, 20.0 × 16.0 in. Collection: DAG

Rachel F. McDermott is a professor at Columbia University’s Department of Religion and one of the leading scholars of Goddess Kali and the shakta tradition in Bengal.

Her anthology Singing to the Goddess is a collection of Bengali lyrics written by poets and singers from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries in English translation. McDermott's lucid introduction places these works in their historical context and shows how images of Kali and Uma have evolved over time. The book provides a unique insight into the Bengali tradition of goddess worship (Shaktism) and the lively translations of these lyrics evoke the passion and devotion of the followers of Kali and Uma. The agonistic vision preferred by poets in their writings about Kali was offered up for a more public-facing performance during the political upheavals unleashed by the Swadeshi—and subsequently, the nationalist—movement in Bengal and India, leading poets like Mahendranath Bhattacharya to compose pointed lyrics like these:

Come, brothers, everyone together:

with wreaths around our necks

let us worship Mother India

offering fruits

of our deeds for the country's improvement.

Risk even your life

for our home-grown goods.

Brothers, sons of the Mother all—

the white merchants shall weep

through our Movement.

Everything that once was India's own

is theirs; the plunder's complete;

eating, lying down, getting dressed—

in all

we humbly fall at their feet.

Develop distaste for those ‘pantaloons’ and ‘coats’;

instead wear the dhutis made here.

As for ‘cigarettes,’ ‘enamel basins’ for washing,

abandon them; don't hold them dear.

Now that they've split up Bengal,

the gloom of our error is past.

Curzon's conspiracy has made us aware;

reject foreign products; hold fast!

Let us all dress in Indian clothes,

singing ‘Victory to the Mother’

at last.

|

Unidentified Artist (Early Bengal School), Dakshinakali, Oil highlighted with gold pigment on canvas, middle to late 19th century, 20.0 × 16.0 in. Collection: DAG |

On the occasion of DAG’s historic exhibition Kali: Reverence and Rebellion, she spoke to the editor of the DAG Journal about her anthology.

Q. You have written about ‘the dramatic shift Kālī worship in this region (Bengal) underwent in the sixteenth century whereby her Tantric aspects were sublimated into aspects more acceptable to a householder audience’. What were the primary contexts that facilitated this move? Can you tell us a little bit about the changing landscape of patrons and institutional patronage that enable Sakta poets and the tradition of writing devotional poetry to the goddess Kali?

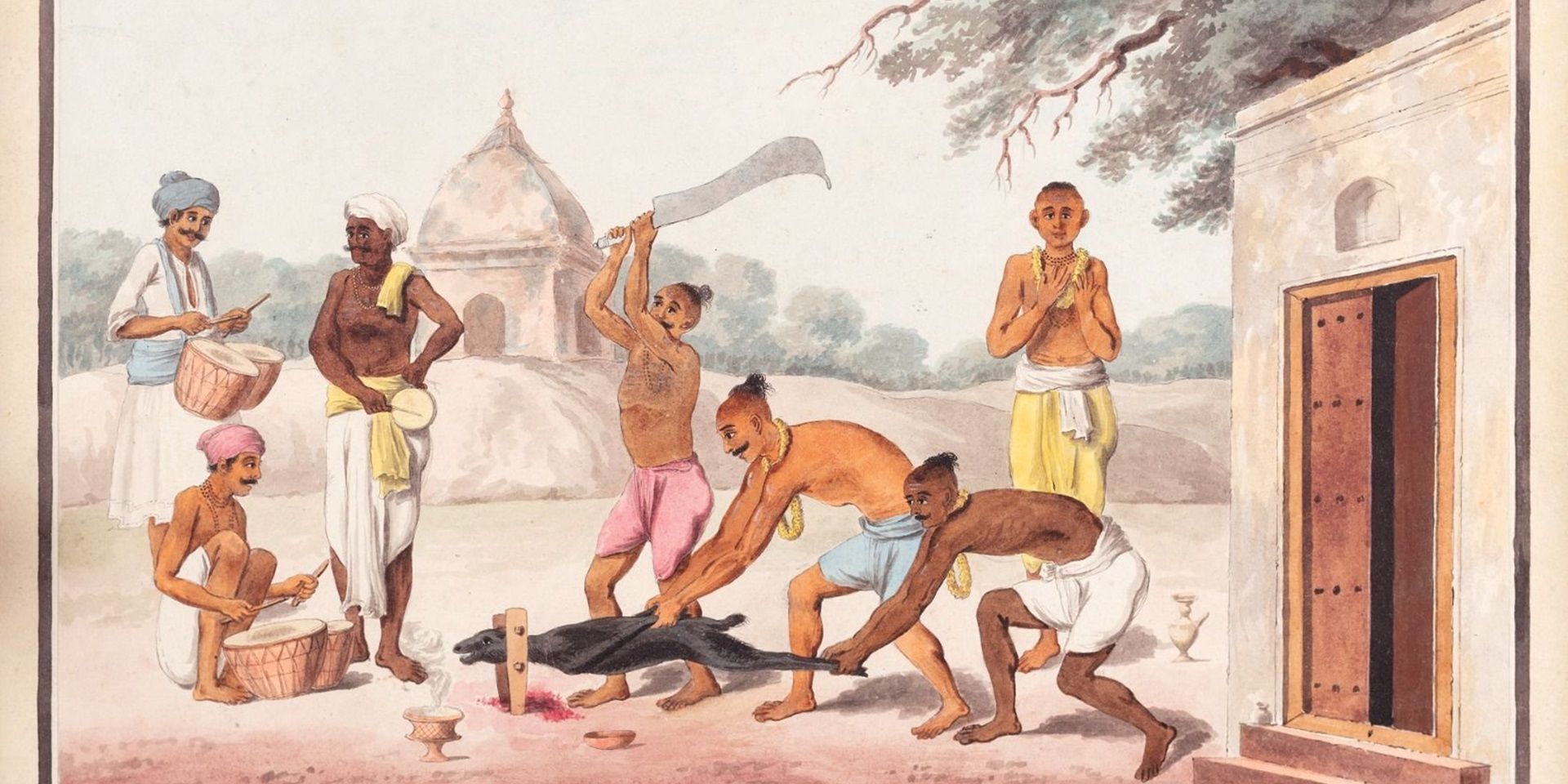

Rachel McDermott: To the best of our understanding, the transformation of the landscape can be attributed, at least in part, to the Mughal Era and the establishment of Bengal as a Subah, an administrative district, under Mughal rule. This settlement process involved collaboration with local landed aristocratic families, many of whom relocated to the region and became influential landowners. A significant number of these families, having migrated from other areas, assumed positions of wealth and prominence. They often took on the role of patrons, supporting artists and literary figures while establishing local courts.

It appears that the early Shakta poets and patrons of the expanding Kali worship were individuals seeking to align the deity they endorsed with their own aspirations for power and influence. In contrast, figures like Krishna, with his idyllic and otherworldly persona, did not resonate as well with those seeking to assert territorial or political claims. Raja Krishnachandra Roy of Nadia, for example, actively promoted goddess worship in the 18th Century, aligning himself with a growing trend to enlist the support of goddesses in bolstering political regimes.

It is important to recognise that this doesn't negate genuine religious beliefs, but rather emphasizes the interconnectedness of the development of Kali worship with its historical and social context.

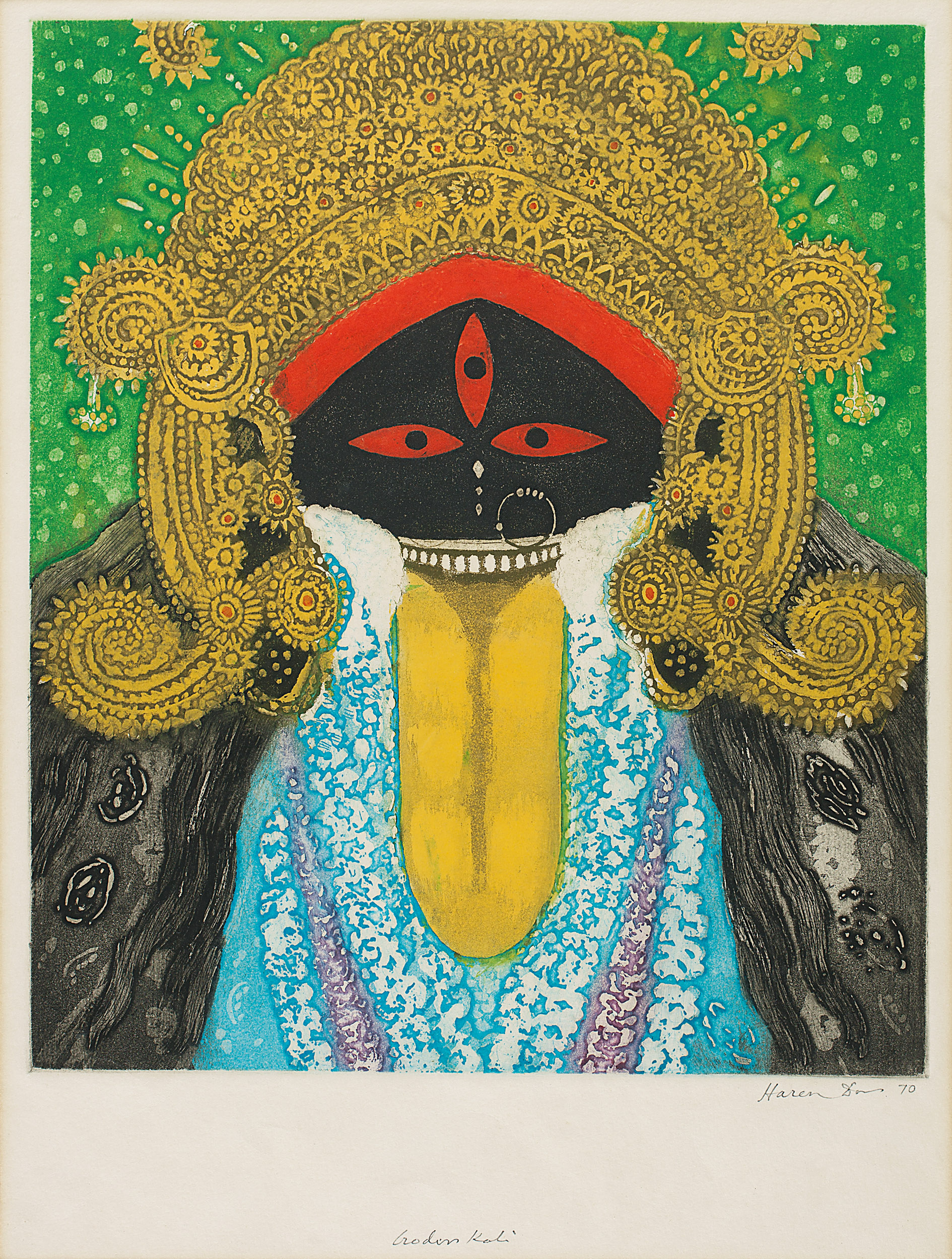

Haren Das, Goddess Kali, Coloured etching on paper. Collection: DAG

Q. How did Kali become appropriated as a nationalist, anti-colonial symbol by poets? How is her occupation of the Bharat Mata symbol/icon different from the other secular and devotional goddesses who were moulded to take on that role?

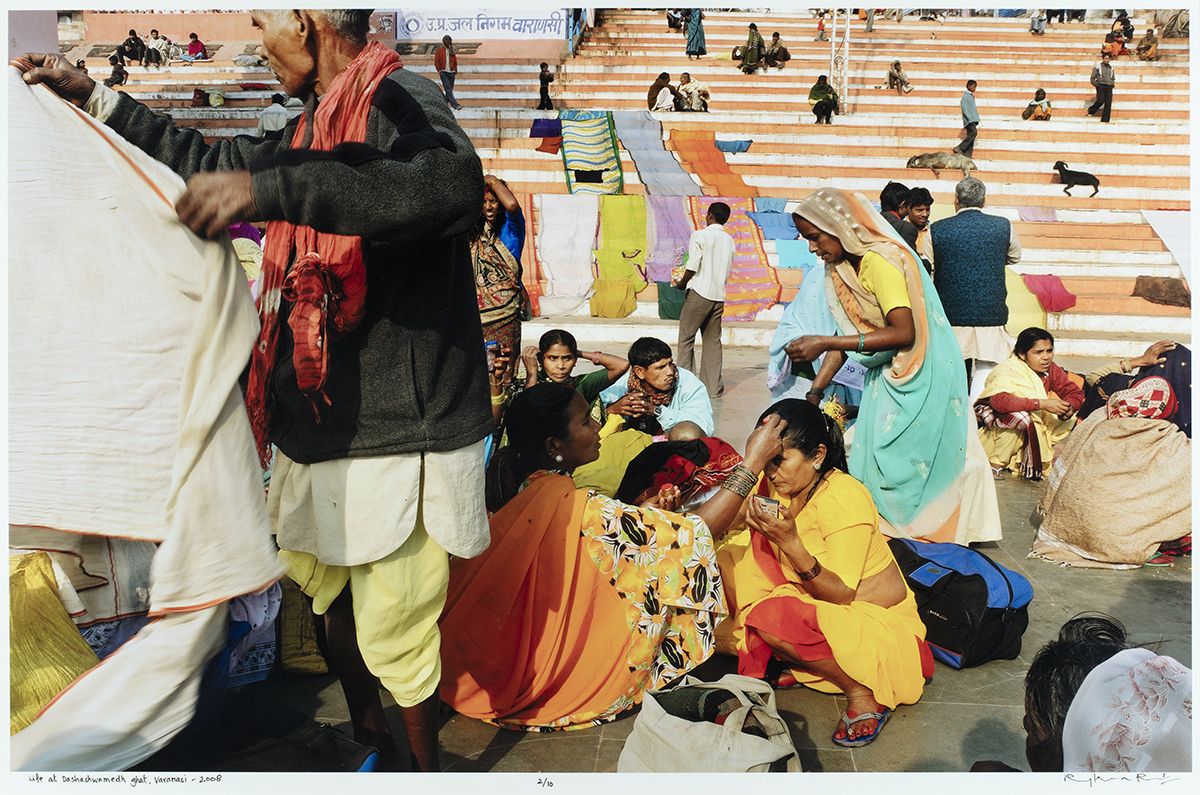

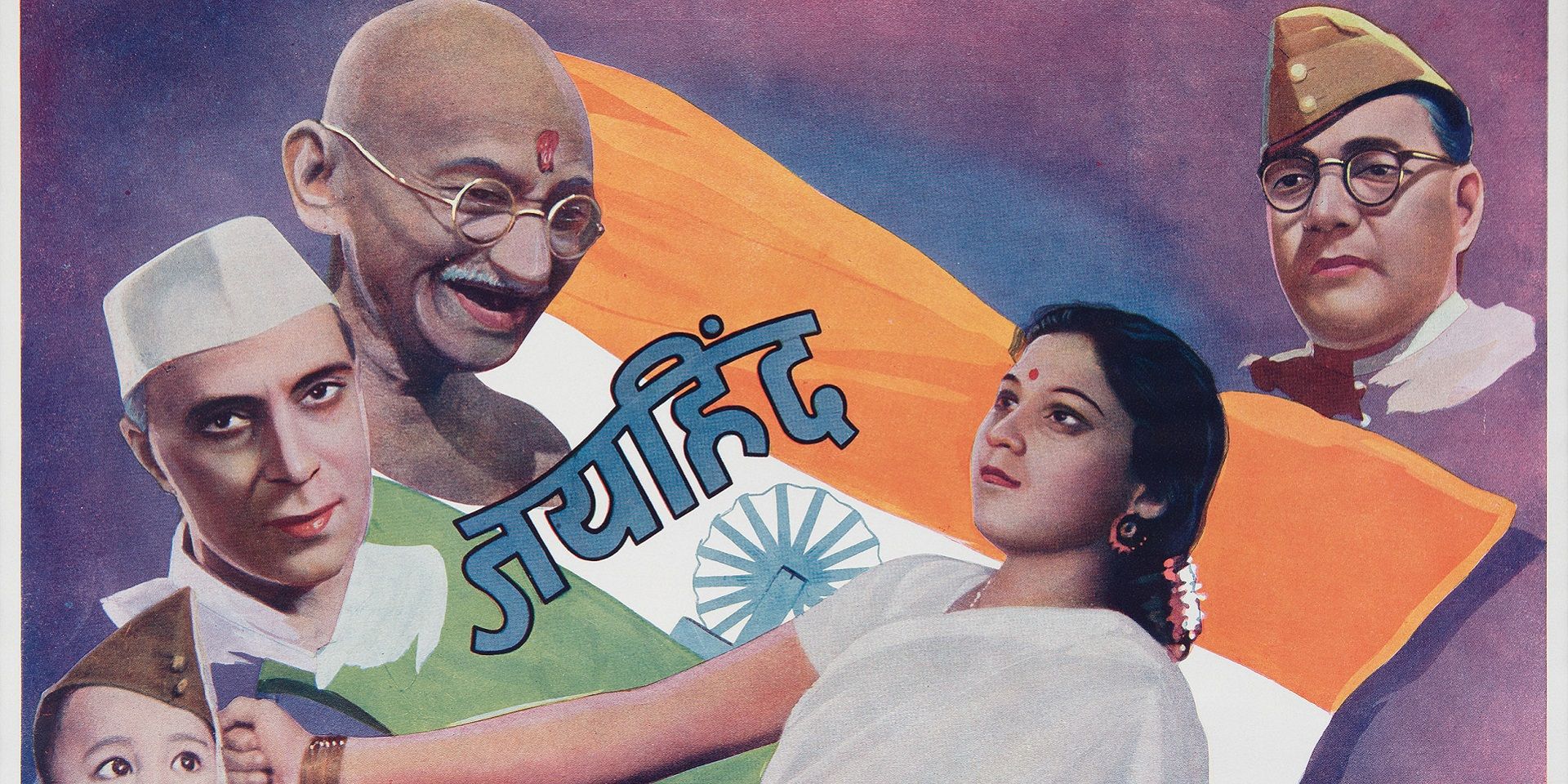

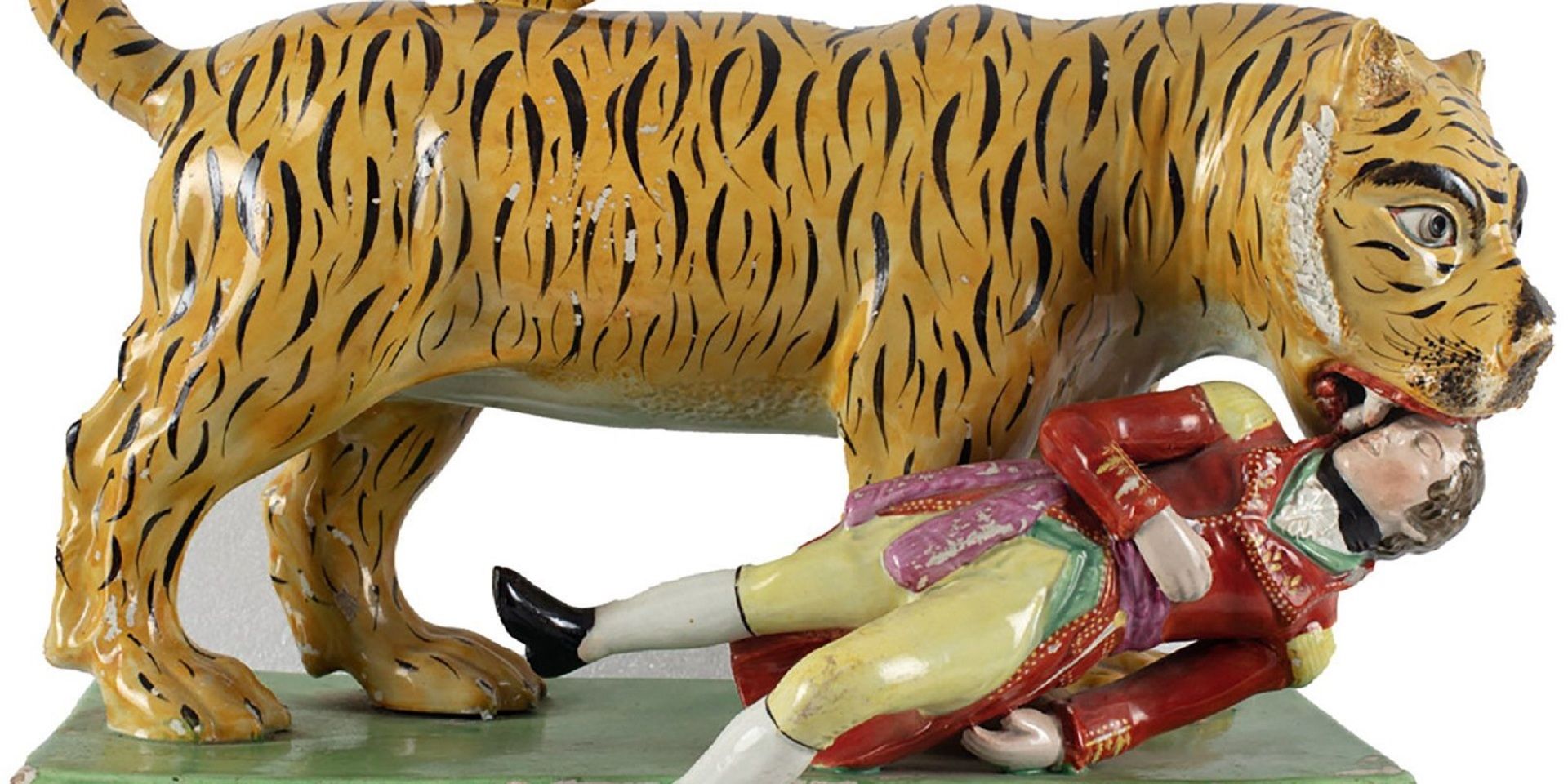

Rachel: Following the 1905 period, particularly after the first partition of Bengal, Kali became a prominent symbol employed by nationalists. The call for offering white goats and Ashuras to Kali gained significant attention, which was championed by groups like Jugantor, known for their nationalist stance and more radical methods, including bomb-throwing.

However, it's crucial to note that this utilisation of Kali wasn't universal. Figures like (Rabindranath) Tagore, for instance, showed little interest in employing Kali in this manner. Tagore's renowned play Bishorjon (Sacrifice) notably displayed an anti-Kali orientation. Kali's role as a nationalist symbol thrived in the early twentieth century, posing an intriguing question about its relevance in contemporary times.

Kali holds a unique place in the hearts of Bengalis, a sentiment not as pronounced in North India unless influenced by Bengali cultural exports. Unlike the widely recognised Bharat Mata figure seen on posters across India, Kali's representation differs. In Bankim Chandra's (novel) Anandamath (The Abbey of Bliss), she is depicted as a symbol of ravaged India. When nationalists called for offerings to Kali, they viewed her as both a vengeful figure and a victorious yet victimised motherland, visually embodying the impact of British oppression.

Today, when Hindu nationalists express intentions to replace figures like Durga or Kali with Ram in Bengal, it represents a departure from the historical context. The imagery associated with these goddesses carries a different connotation, contrasting with the earlier perception of Kali as a symbol of both vengeance and victimhood during the struggle against British colonialism.

|

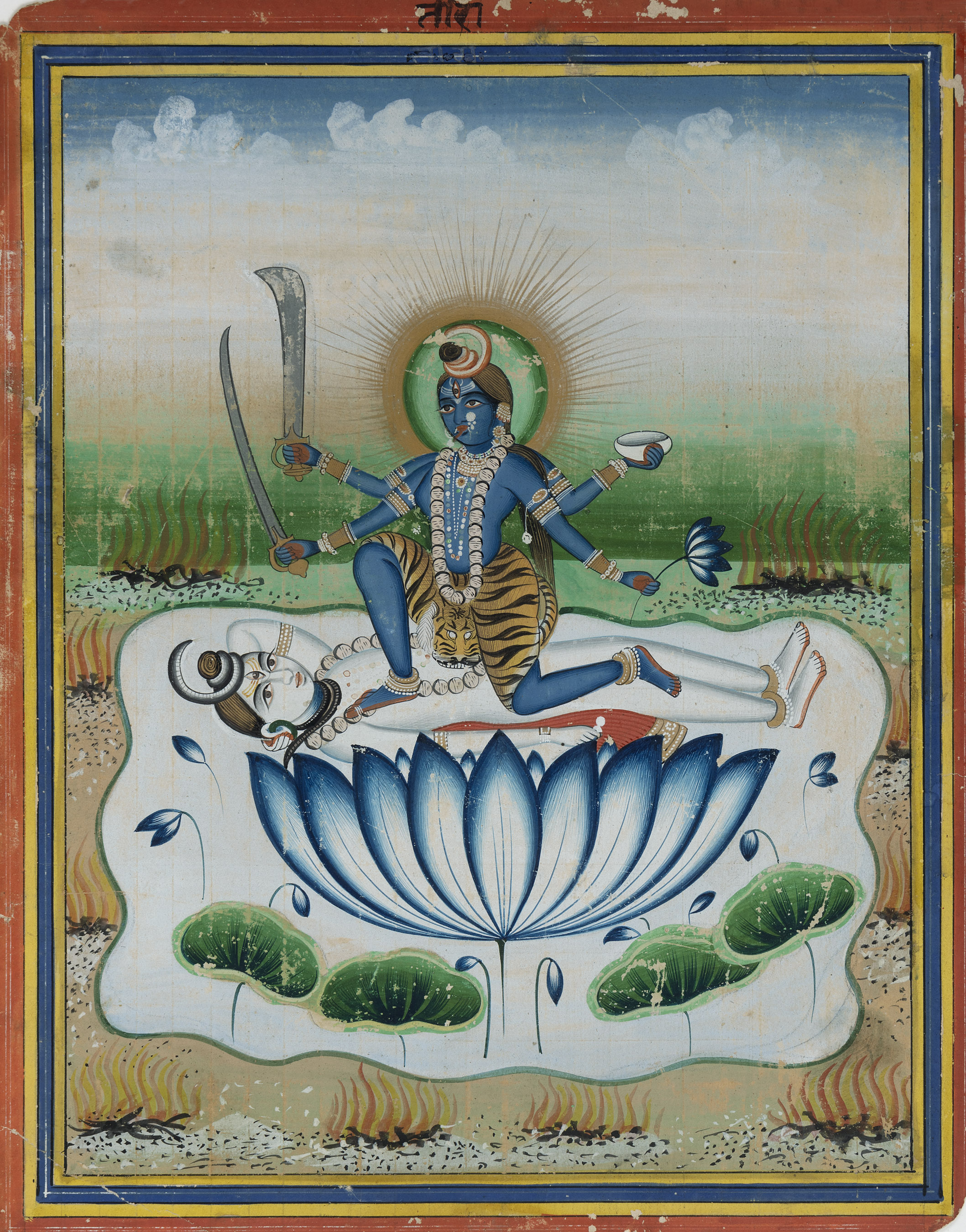

Unidentified Artist (Miniature Painting), Tara, Natural pigment highlighted with gold and silver pigment on paper, 10.0 × 8.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. What was the relationship between personal performances of belief or devotionalism and the writing of devotional poetry to Kali? Did most poets encourage spiritual practices through their work, or were they primarily concerned with a literary public?

Rachel: It’s very difficult to tell what is inside of a person. Consider, for instance, the debate surrounding Kazi Nazrul Islam. Some think that he was merely a skilled practitioner of the Shakta Padabali genre, questioning whether his expressions were driven by genuine affection for the Goddess. As you are aware, this remains disputed. There are those who assert that his devotion to the Goddess was purely a manifestation of literary prowess and dexterity, and reject the notion that he harboured a personal love for the deity.

Several of the eighteenth-century Shakta poets, including figures like Ramprasad (Sen), remain somewhat enigmatic. While the poetry of Ramprasad undeniably radiates a profound sense of love and devotion (bhakti), the lack of autobiographical writings or concrete details makes it challenging to extract (this information) from the haze of hagiography and precisely discern their personal sentiments. Personally, I suspect that one cannot write poems of such beauty and inspiration, if there weren’t something there—inside.

|

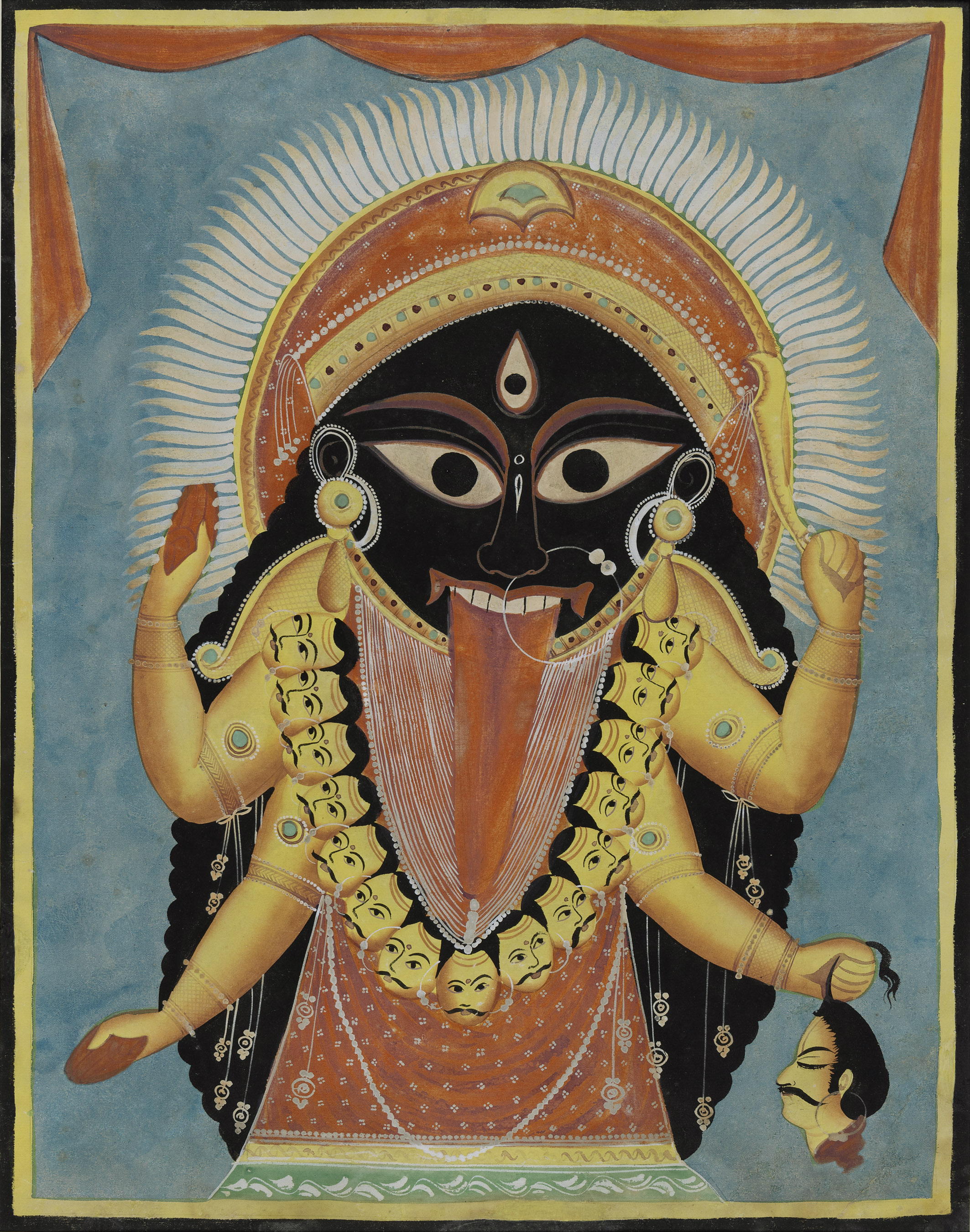

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat), Dakshinakali, Watercolour and gouache on paper, late 19th century, 19.5 × 15.5 in. Collection: DAG |

On bhonita:

The tradition of bhonita—adding one's name at the end of a poem—has been a longstanding practice in Bhakti poetry. This approach involves entering into the narrative of the poem, offering commentary, and thereby personalising the poetic expression. However, in my research on Ramprasad, a significant phenomenon emerges wherein individuals adopt the name Ramprasad, incorporate it into their self-written poems, and add them to the collective body of work. This practice allows people to step into the persona of the renowned poet. Yet, when it comes to establishing ‘facts’ regarding whether a specific poem was truly authored by Ramprasad or another poet, particularly those introduced into the literature at a later stage, the distinction becomes murky. Notably, with figures like Ramprasad or Kamalakanta (Bhattacharya), the early poems provide a clear insight into the themes and language employed. However, encountering someone added to the same name a century later yields a distinct emotional tone and impact, making it challenging to assert authenticity.

Q. How did the practices of visualising the interior landscape, with an aim towards activating the cakras through kundalini yoga, inform poets and artists in their depictions? Have you come across any evidence that the modern, twentieth century Kali or sakta poets, were influenced by the popular bazaar art imagery of Kali that was being printed by the bat-tala presses or by the patuas of Kalighat, and were perhaps responding to those?

Rachel: I conducted extensive research for a companion book titled Mother of my Heart, Daughter of my Dreams, where I looked into the historical use of Tantric imagery within the Shakta poetry tradition. I discovered a gradual decline in the utilisation of Tantric imagery over time. Notably, poets like Ramprasad and Kamalakanta prominently incorporated this imagery into their works. However, even with these poets, it remains unclear to what extent this usage reflected a personal spiritual practice that found expression in their poetry.

When discussing the emergence of Kali from the Tantric world, particularly in response to your earlier question, it seems that this connection is precisely where it originated. In Tantras, Kali served as an internal image for worship within a Tantric framework, specifically associated with the raising of the Kundalini. Early depictions of Kali reflected a static image, unlike the dynamic representations seen in contemporary Kali Puja, with her in action, standing on Shiva, or humanized. Instead, these early representations resembled an icon within the heart—with her gaze set straight.

|

Unidentified Artist, Jai Maa Kali, Mechanical reproduction on paper pasted on cardboard, 23.7 × 15.7 in. Collection: DAG |

The earliest Shakta poetry explored elements of Kundalini Yoga within the body, emphasising the presence of the Goddess. However, over time, these references faded away. In today's Shakta poetry, it is unlikely to find such references, given the diminishing popularity of the associated practices. Yet, in the early twentieth century, a manuscript by Kamalakanta called Shadhokoronjon came to scholarly attention, explicitly detailing the Kundalini-raising process. This manuscript was based on a Tantric text called the Shat-Chakra-Nirupana, and my translation of the text revealed a point-for-point correspondence with Kamalakanta's poem. This connection underscores the clear influence of Tantric practice on early poets.

However, the lingering presence of these practices in contemporary times remains uncertain. Privacy surrounding spiritual practices makes it difficult for us to definitively know the current status of such traditions. And we also know that there are a lot of Tantrikas who are not poets, but are Kali worshippers and practice Tantra. So, just because it is not in the poems, doesn’t mean it’s not in the public, somehow.

|

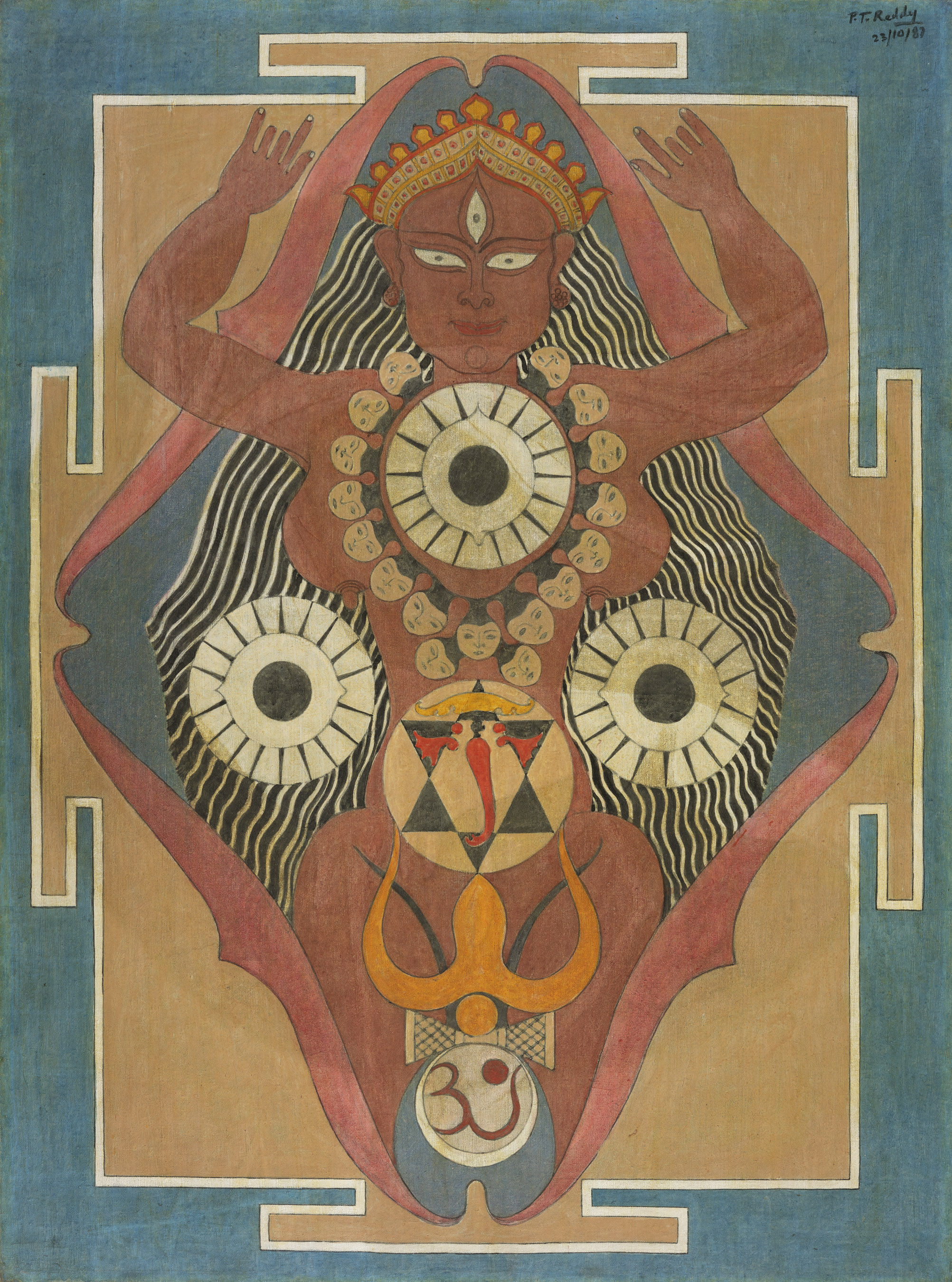

P. T. Reddy, Birth of Ganesha, Acrylic on canvas, 1987, 48.0 × 36.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Your anthology includes female poets who were largely overlooked in earlier collections (most notably the Shakta padabali as compiled by Amarendranath Ray). How do you see the value of their contribution to this genre? With some poets like Ma Basanti Chakrabarti suggesting a more domesticated/ domesticable form of the goddess, would you suggest that it departed from the tradition of highlighting her radical, political-temporal investments?

Rachel: I don’t have enough evidence regarding female poets to talk about any discernible trends. Despite extensive searching, I found very few, and apart from Ma Basanti Chakrabarti, the others I encountered were not particularly noteworthy. However, I included them in my anthology nonetheless. Ma Basanti Chakrabarti's poems, as you noted, do not align with the expectation of a bold, nationalist portrayal of Kali. Instead, the goddess in her poetry appears more domesticated. Many of my students, especially those in the United States, express disappointment in her work, because they were hoping for a different perspective from a female poet. It's important to note that I don't have access to her complete body of poetry, and my knowledge is based on the limited poems I came across, often through audio formats like cassettes and CDs.

This raises an intriguing, yet underexplored question: does the Goddess hold different meanings for women compared to men? However, considering the diverse range of perspectives within both genders, it becomes challenging to make generalisations. In the case of Ma Basanti Chakrabarti, it appears that the Goddess has been portrayed in a domesticated and sweetened manner, addressing Shiva as ‘Daddy’ or ‘Baba’.

The disappointment expressed by my students highlights the diverse expectations and interpretations surrounding the portrayal of the Goddess in poetry. One aspect of Bengali Shakta poetry, which I find both charming and endearing, is the presence of critique, engagement, and a certain petulance, termed as obhimaan. There's a whimsical quality in the expressions, questioning whether it wouldn't be better if the divine figure didn't look a certain way or did not stand on Daddy's chest like that. It involves a dynamic interaction. Ramprasad, in a more poignant manner, would express sentiments like, ‘You invited me to stand on a ladder, and then you pulled it away. What kind of justice is this? Why have you provided sustenance to others and not to me?’ This form of critique towards the divine is less prevalent in Vaishnav poetry, setting apart the Shakta tradition with its candid examination and questioning of God's actions.

Madhvi Parekh, Kali on Mahishasur, Acrylic on canvas, 2005, 18.0 × 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

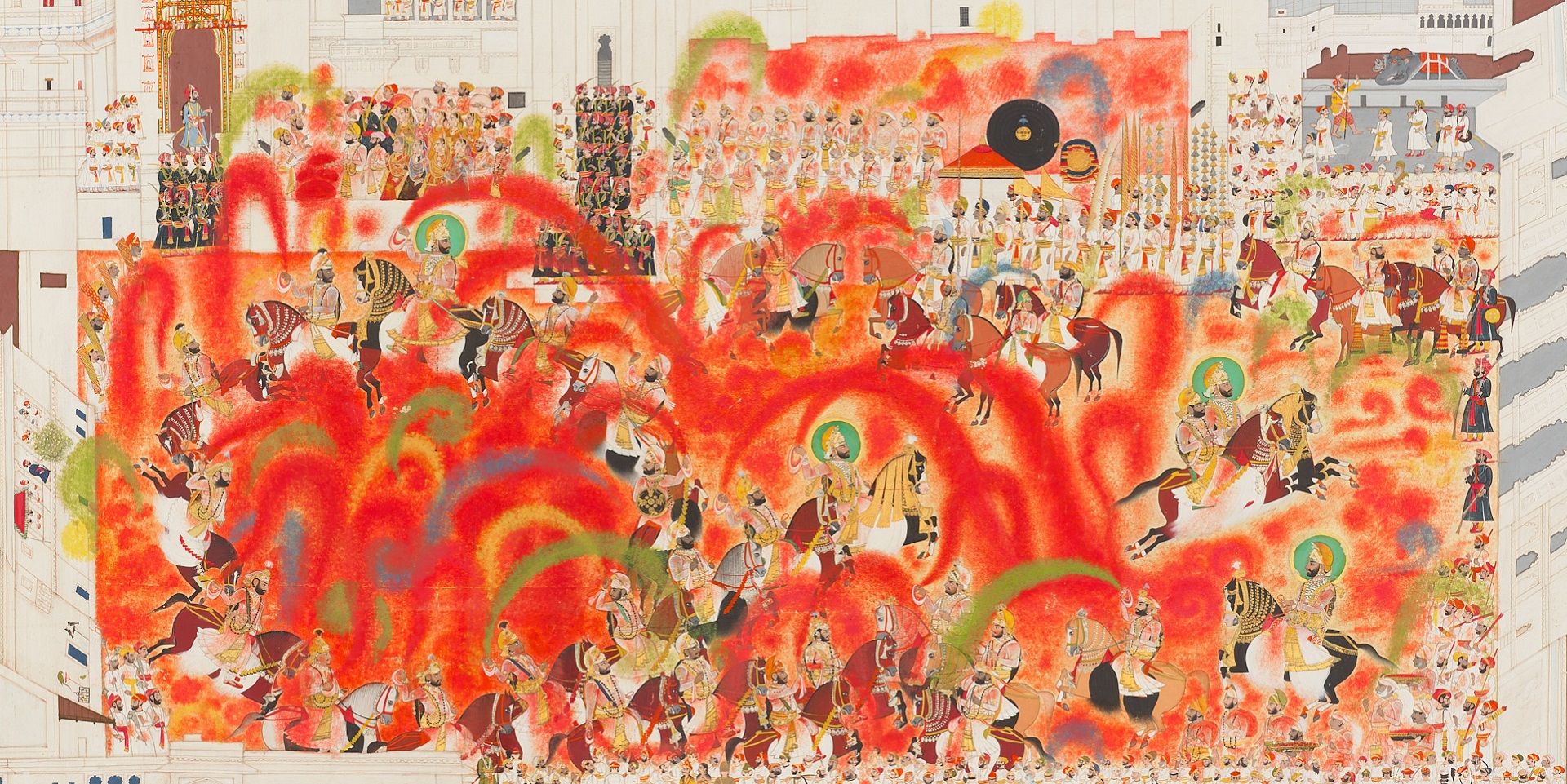

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

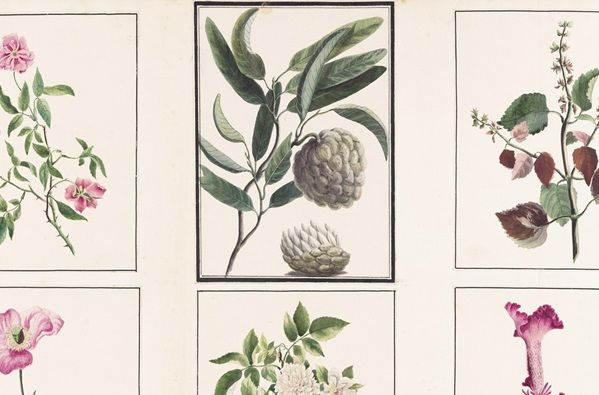

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025