Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

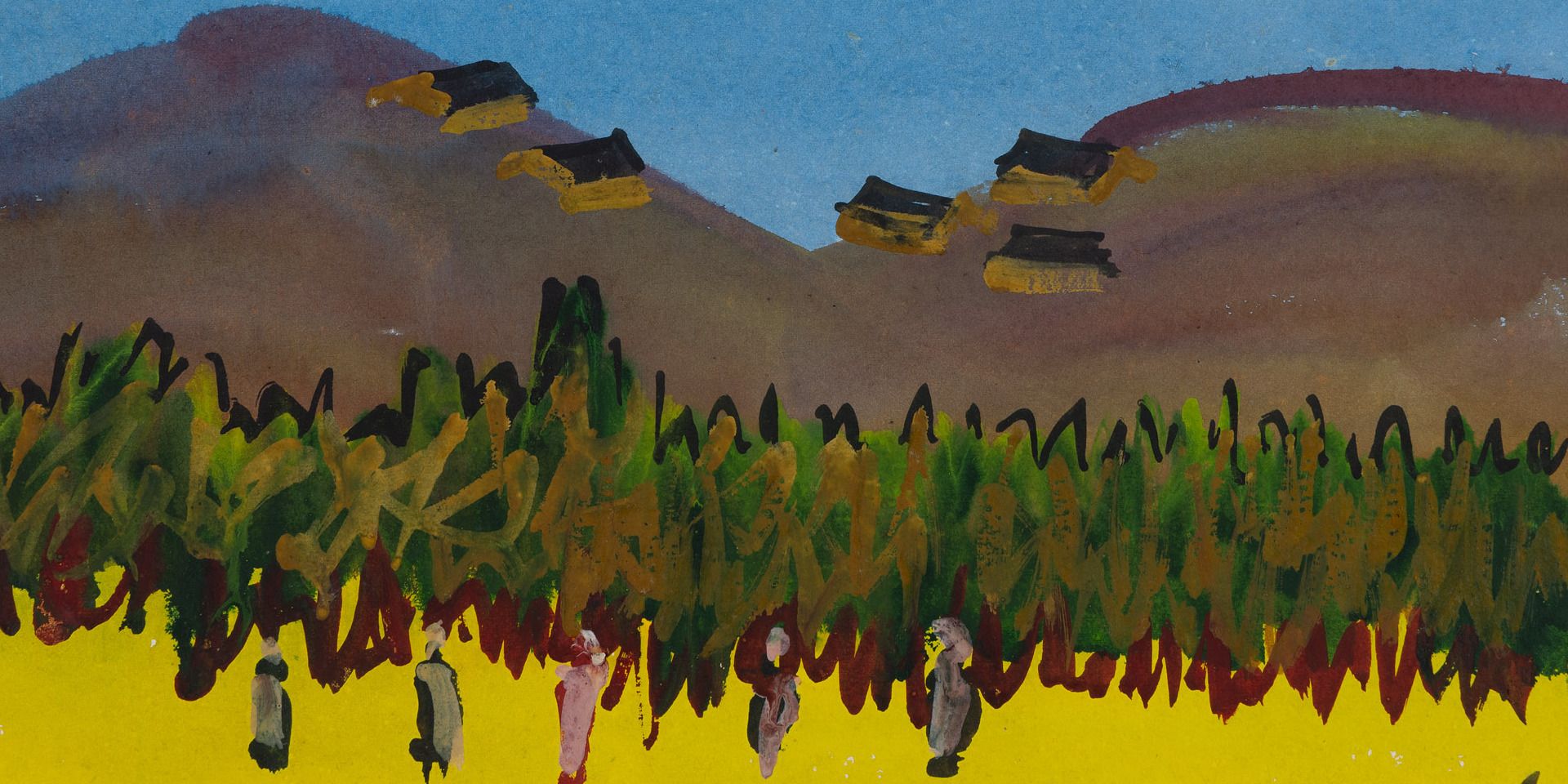

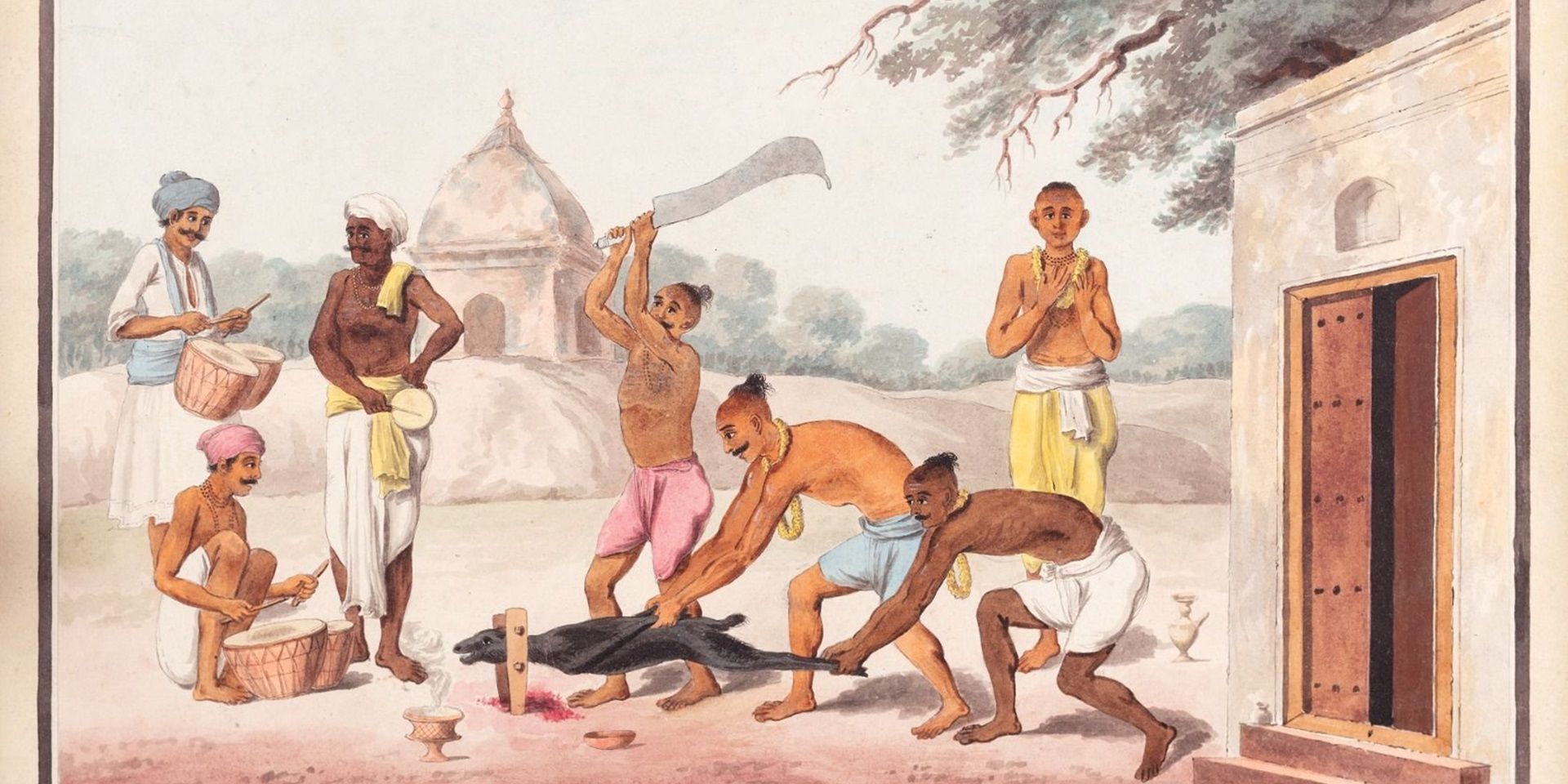

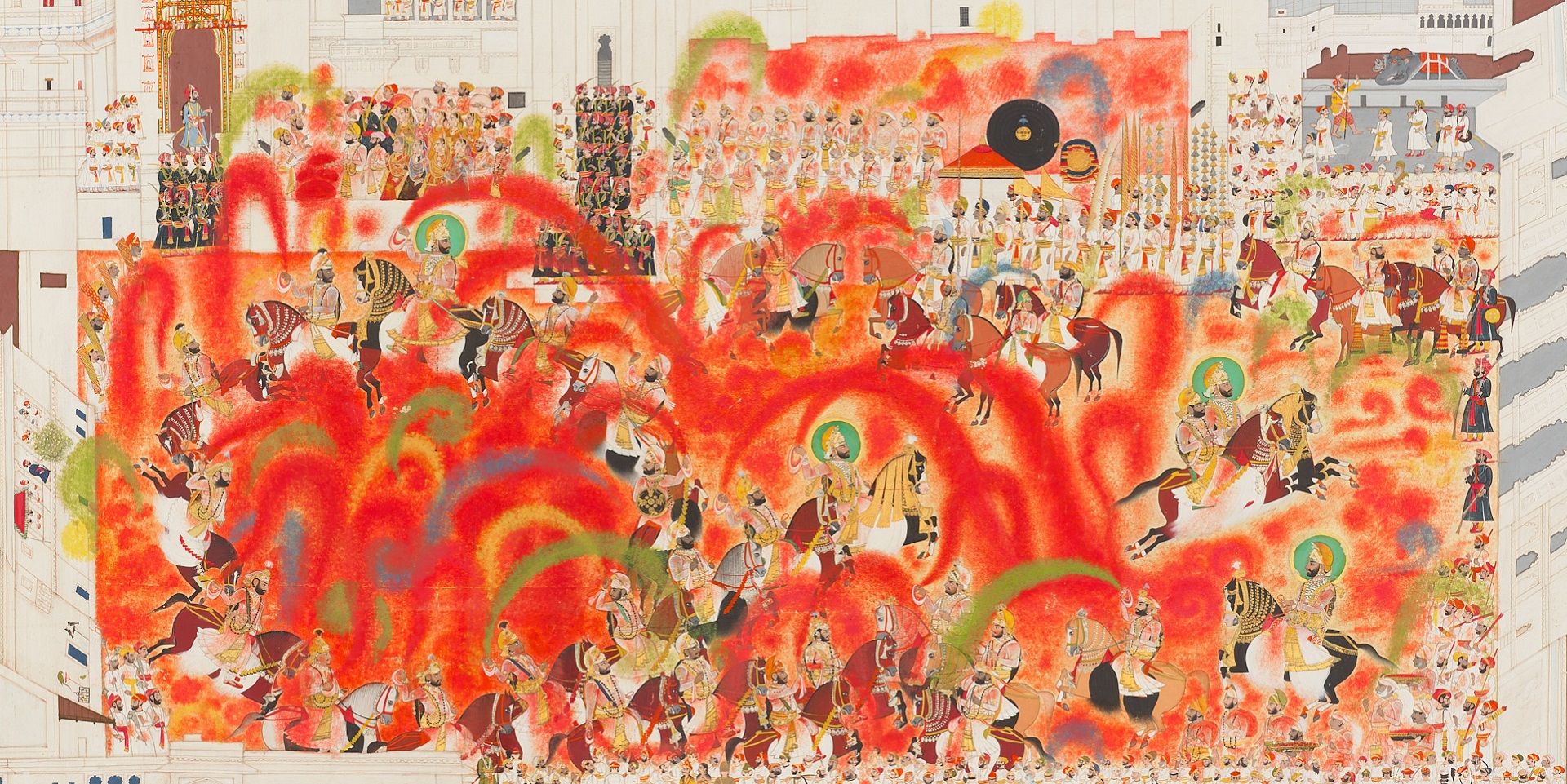

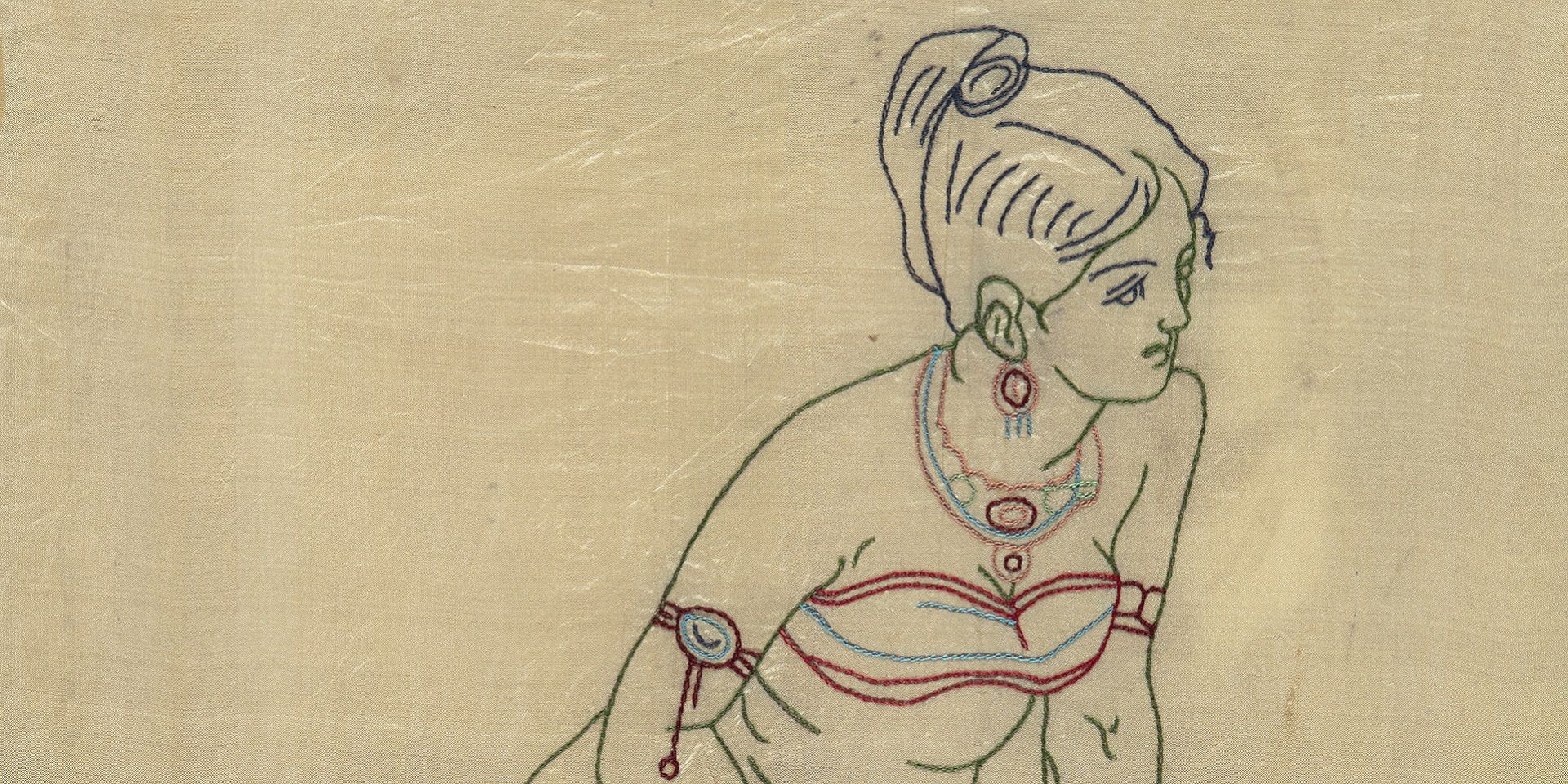

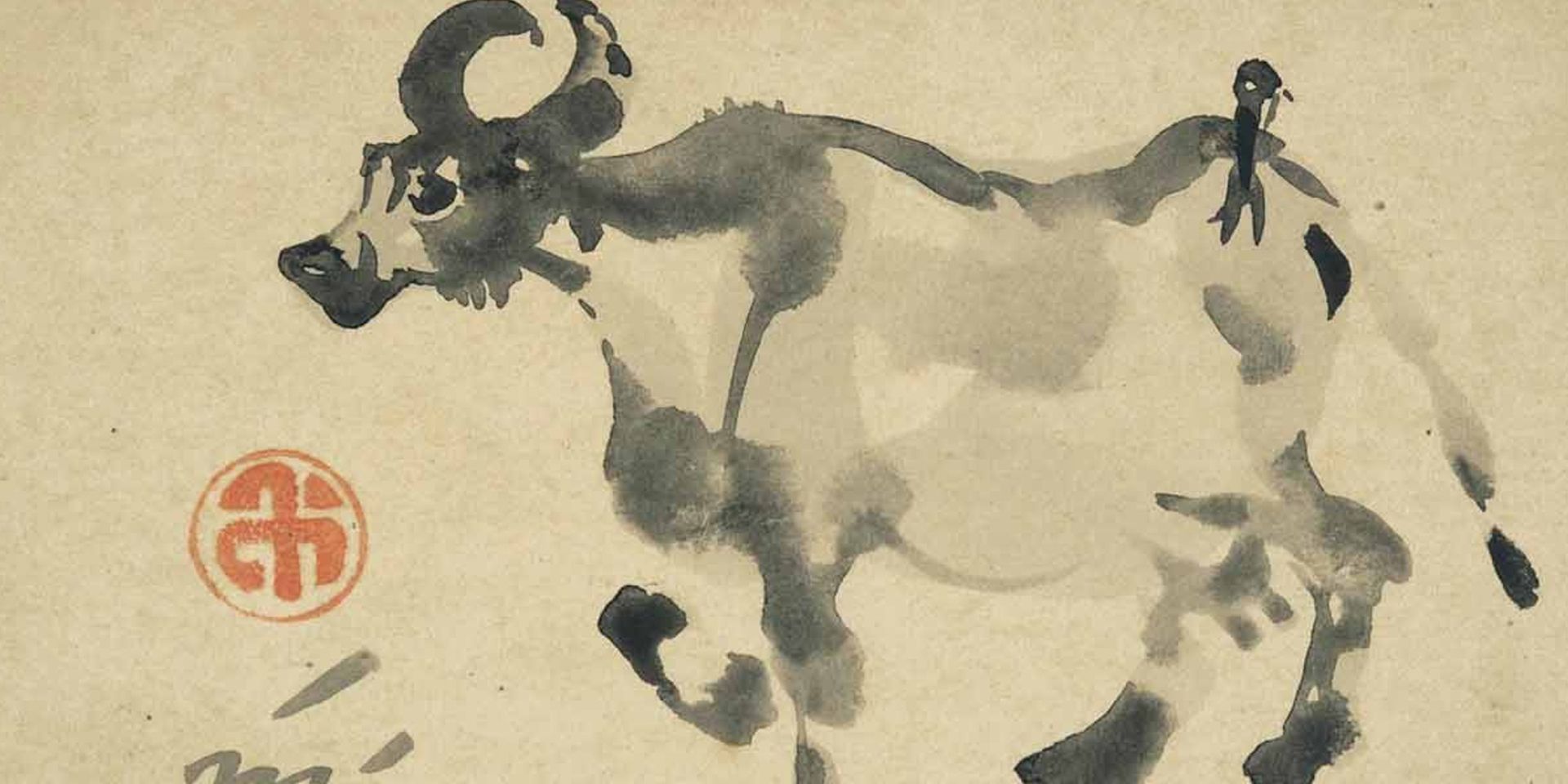

Murshidabad Artist (Company School), Fete des Hindous appellée Kales Pojas [Hindu Festival called Kali Puja] (detail), Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, early 19th century. Collection: DAG

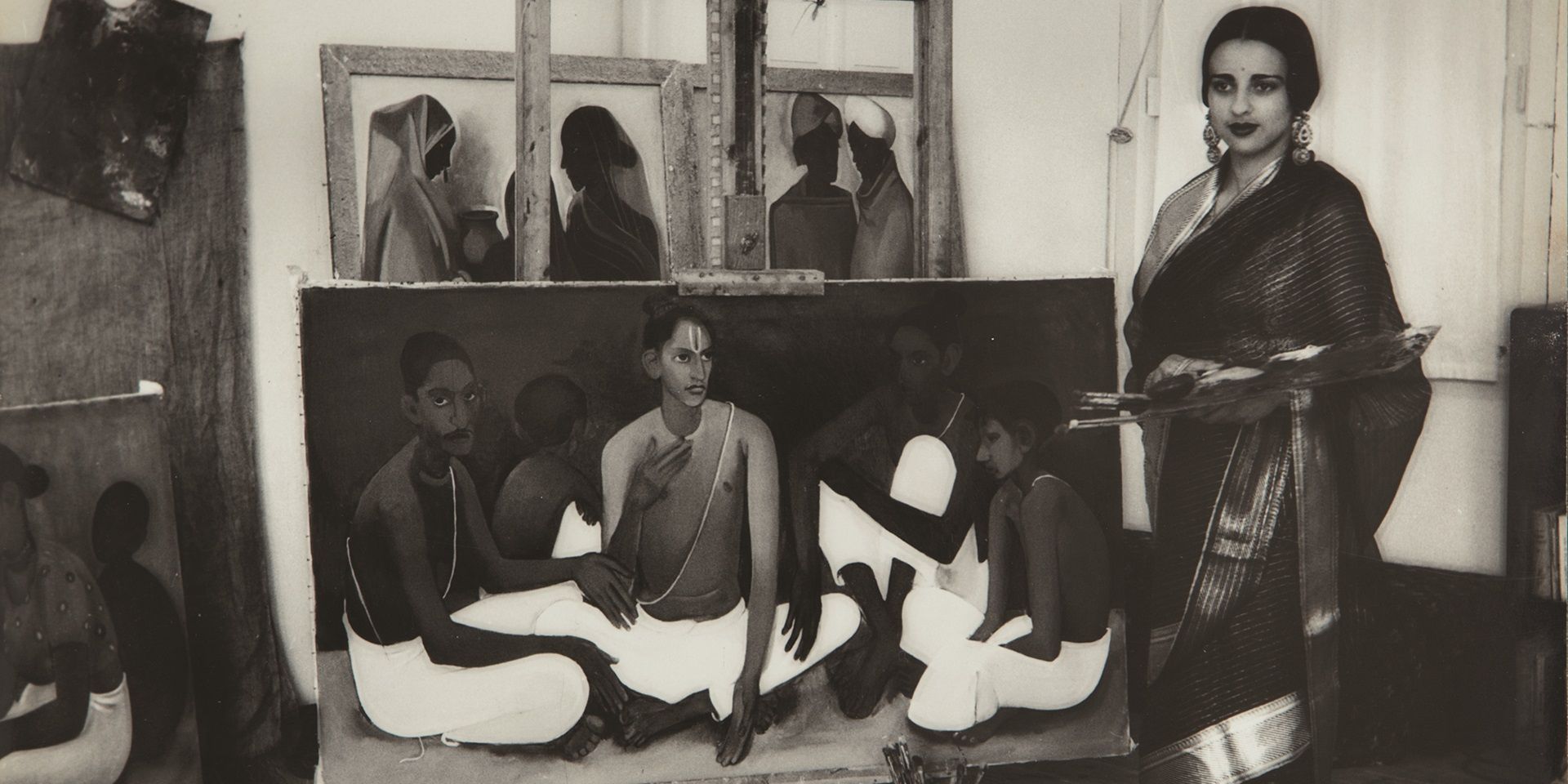

Holly Shaffer is an art historian, and the Robert Gale Noyes Assistant Professor of Humanities at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. Her research focuses on the artistic and visual cultures of South Asia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in relation to British colonialism and global trade networks.

Her work examines the intersections of art, empire, and materiality, with an emphasis on cross-cultural exchange and the role of artists—both Indian and European—working under colonial patronage. Shaffer is particularly known for her scholarship on Company painting, pigment and paper technologies, and the complex visual languages that emerged from colonial encounters. Her current projects explore how art shaped, and was shaped by, the structures of empire, leading to her publication Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760-1910, her article, co-authored with Yuthika Sharma, “To Fill ‘a Gap in Indian History’: An Archival Reckoning with the Term Company Painting” in Archives of Asian Art, and the upcoming exhibition Painters, Ports and Profits: Artists and the East India Company, co-curated with Laurel Peterson at the Yale Center for British Art (or, the Y. C. B. A.).

She spoke to the editors of DAG on the history of ‘Company’ painting and the role of political and social transformations in the production of the style, on the occasion of DAG’s own landmark exhibition, A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings, c. 1790-1835.

|

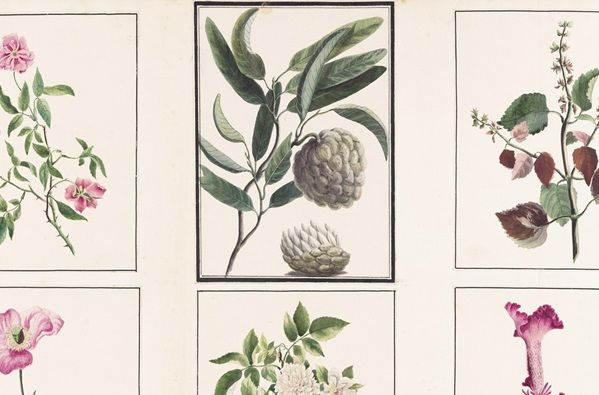

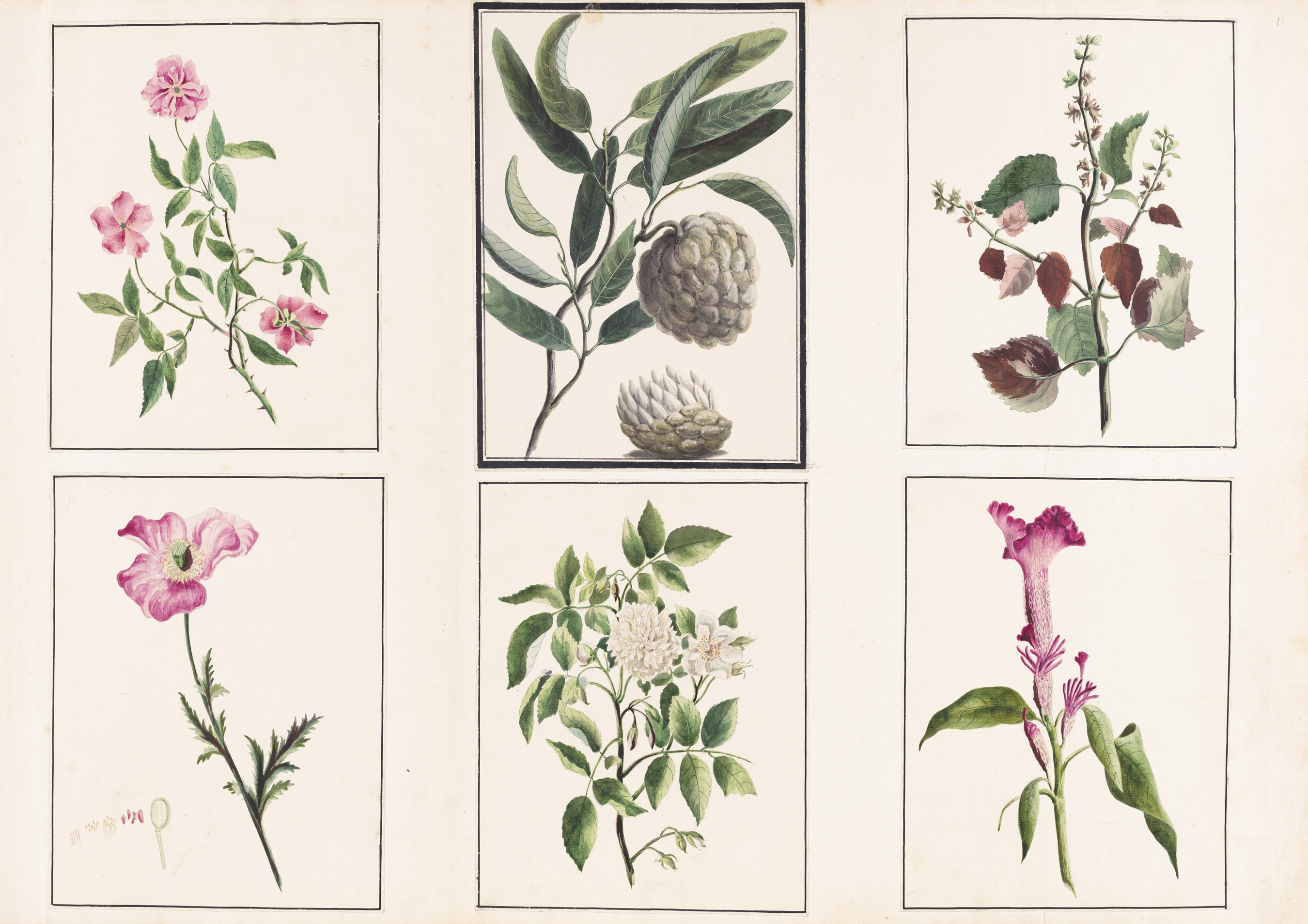

Malabar or Madras Artist (Company School), Wild Jackfruit (Artocarpus hirsutus), c. 1807, Watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG |

Q. Can you discuss the history of the term ‘Company painting’, which is sometimes focused on the corporate identity of their patrons, at other times the identities of the artists or the geographical spread of their operation – do any of these definitions speak to a point about stylistic unity or affinities?

Holly Shaffer: Yes, I think it's a really fascinating debate. In the article I co-wrote with Yuthika Sharma, we explore the deep and complex history of the term Company painting; and it uncovers some unexpected aspects of that history. The term itself has a long trajectory. Originally derived from the Persian word phirangi, meaning ‘foreigner’s art’, it later evolved into Company kalam or Company shaili—terms used to describe a style or school of painting associated with colonial-era patronage. In English, it eventually became known as Company painting. What is really intriguing is how this term was shaped by a variety of actors over time.

For instance, figures like Ishwari Prasad—an artist working both for patrons in Patna like P. C. Manuk and within institutions like the Government School of Art in Calcutta (now, Kolkata) under E. B. Havell and Abanindranath Tagore—played a role in shaping what we now call Company painting. Art historians such as Rai Krishna Das in Banaras were also deeply involved in this dialogue. And there were others—early twentieth-century writers and scholars—who were trying to pin down what exactly this style was and how it might provide a link between Mughal and modern art.

The terms kalam (pen) or shaili (style, or school) mattered especially in the early to mid-twentieth century when art history, as a Western discipline, began emphasising categorisation—distinguishing styles, hands, schools. This had a lot to do with market interests: auction houses, dealers, museums, and libraries wanted clear taxonomies for cataloguing and valuation purposes. This drive to define styles has a history in India, in which archivists in the seventeenth, eighteenth, or nineteenth centuries labelled certain styles according to colour and shade, like nim kalam (half-toned), or by city, such as Dilli kalam (Delhi style). But the desire to add onto this tradition to classify a wide range of arts by style or school was largely a twentieth-century phenomenon. Another important dimension we explore in the article is how the meaning of the term Company painting shifted after independence and partition. In the early twentieth century, it was largely understood as a style—artists could work in the Company style but also engage in other visual languages. They were not limited to one idiom. We know this from the work of artists like Jairam Das in Patna, among others, who clearly operated in multiple modes. It is very possible there’s more material we’ve lost that could further demonstrate this flexibility.

Unidentified (Patna School) artist, Holi being played in the courtyard, c. 1795. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The collector and art historian Mildred Archer had an important role in the history of the term Company painting. When she returned to England from India and became the Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Library, she effectively reshaped the term. You can trace the transformation across her publications. Her first book, Patna Painting, was published in 1947—a very symbolic year—and was clearly indebted to her dialogues with Ishwari Prasad, P. C. Manuk, and other scholars in India. From there, her scope widened: the term Company painting began to encompass not just the British East India Company but other trading companies, and expanded geographically to include Southeast Asia and beyond.

Archer’s cataloguing also started to emphasise ethnicity, which is something I am still trying to grapple with. Her framing—and the dominant framing among many early twentieth-century scholars—defined Company painting as works by Indian artists serving Company patrons or a broader market. But I do not think the clientele was limited to the Company. It was also regional. There was a thriving, mixed-market context that was situated in regional courts and markets, moving beyond colonial patronage, as many excellent scholars explore in their work.

This is something that the exciting upcoming exhibition, Painters, Ports and Profits: Artists and the East India Company, 1760–1830, that I am co-curating with Laurel Peterson at the Yale Center for British Art is trying to address. It aims to balance the macro, large-scale history of an exceedingly powerful company that also became a colonial state with that of the smaller-scale, micro histories of specific artists, patrons, and a thriving market for art. These histories are also connected to papers, pigments, and techniques; for the Y. C. B. A. show we have worked closely with paper and paintings conservators and scientists to understand how these works were made, in particular how artists experimented with new materials and often adapted their methods to work for new clienteles and a popular market. I think much of what we call Company art could also be understood as commercial art. And that is what makes the term ‘Company’ so complex and interesting. It reflects not only colonial institutions but also broader market forces—and that tension is something worth exploring further.

|

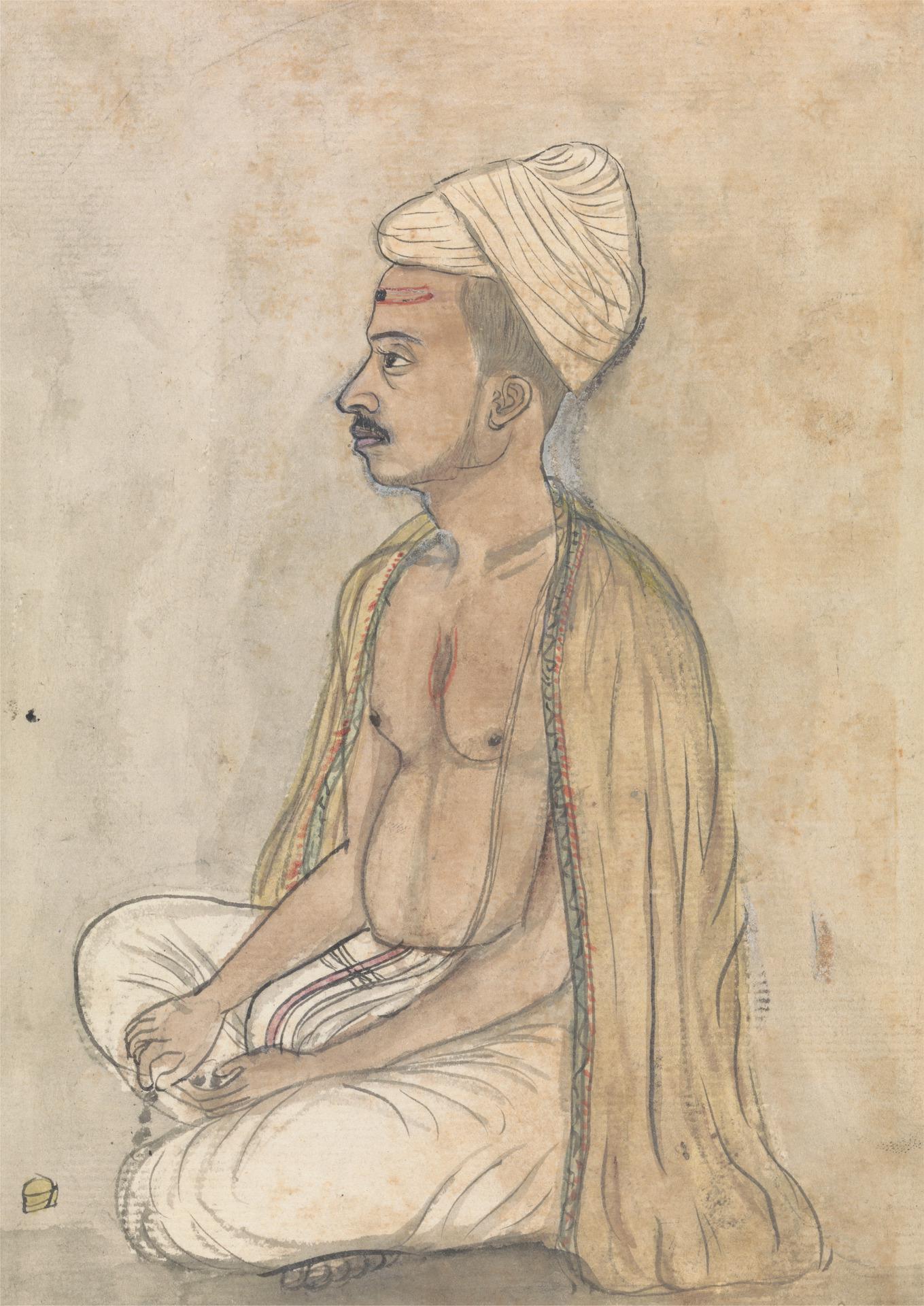

Gangaram Chintaman Tambat, Man with a Yellow Shawl Sitting Crosslegged, Watercolour, gouache, and graphite with pen and black ink on medium, slightly textured, cream laid paper, 8.8 x 5.9 in. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons and Yale Centre for British Art |

Q. Could you expand on this idea of the mixed-market context that conditioned the emergence of these works?

Holly: There have been thriving forms of popular and commercially-driven art from the very beginning—probably for as long as art has been made. In India, there has always been a popular market: bazaar art, devotional images, and countless forms of visual culture created for everyday audiences, not elite patrons. One reason I believe this so strongly is through my and Yuthika’s work on Ishwari Prasad. He was trained by his mother, Sona Kumari, who was herself trained by her father, Shiva Lal. This lineage shows that women were active participants in artistic workshops—a fact that might seem obvious but is under-documented, especially since women and popular artists often did not sign their works. In the British Library, the surviving works attributed to Sona Kumari are devotional pictures. These are part of a much older tradition, one we also see later with chromolithographs, but that began long before.

In regions like Western India, devotional pictures were sold in and around temples—as icons, souvenirs, or objects of worship. And artists who made these kinds of images later expanded their practice to accommodate other subjects, including those appealing to company agents or tourists. This fluidity speaks to a commercial, market-oriented logic—a point Tapati Guha-Thakurta articulated brilliantly in The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art. She drew a critical link between Company painting and forms like Kalighat painting and Bat-tala prints. Her insight is essential. It reminds us that Company painting needs to be understood not only through the lens of colonial patronage but also through the commercial art market.

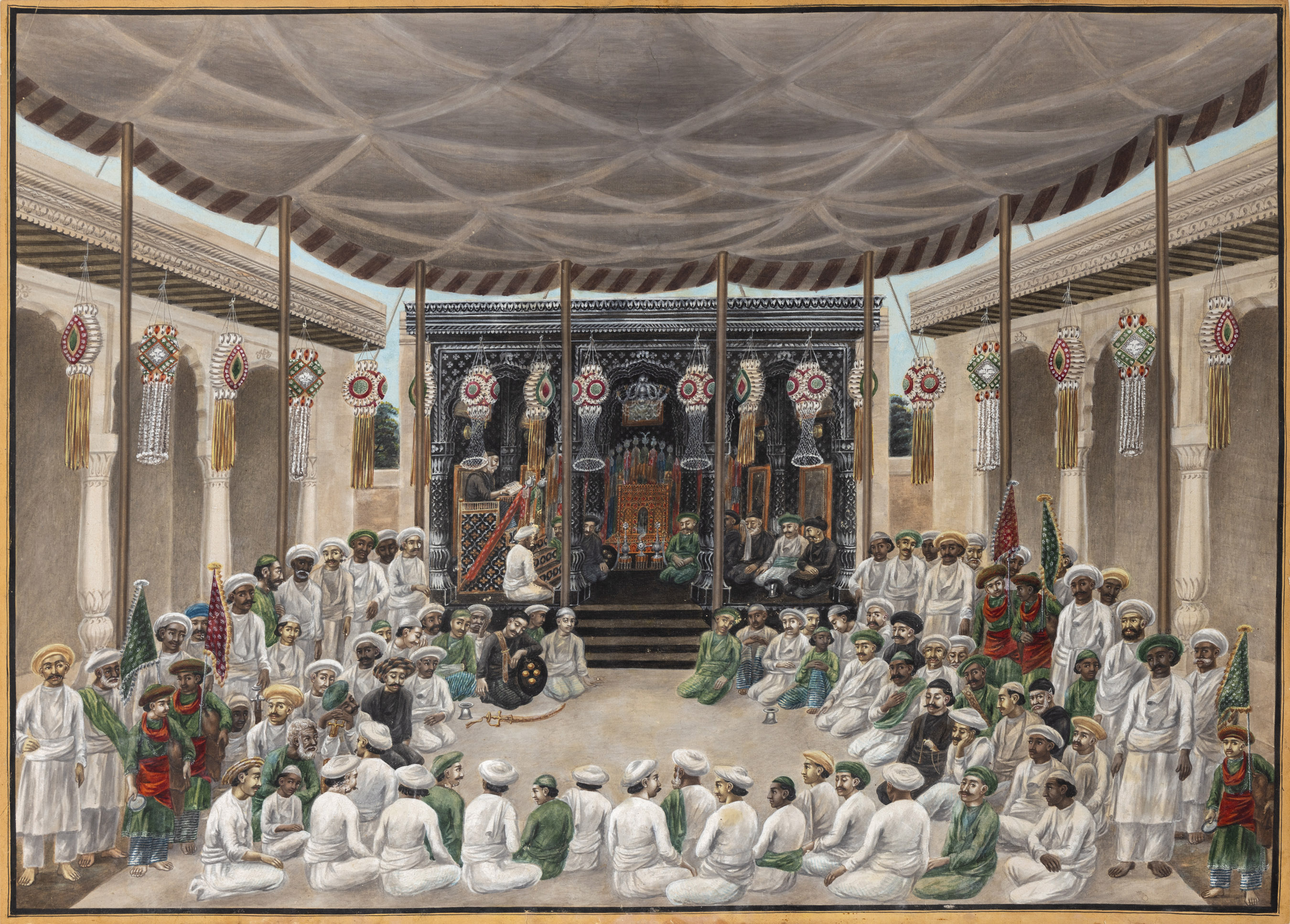

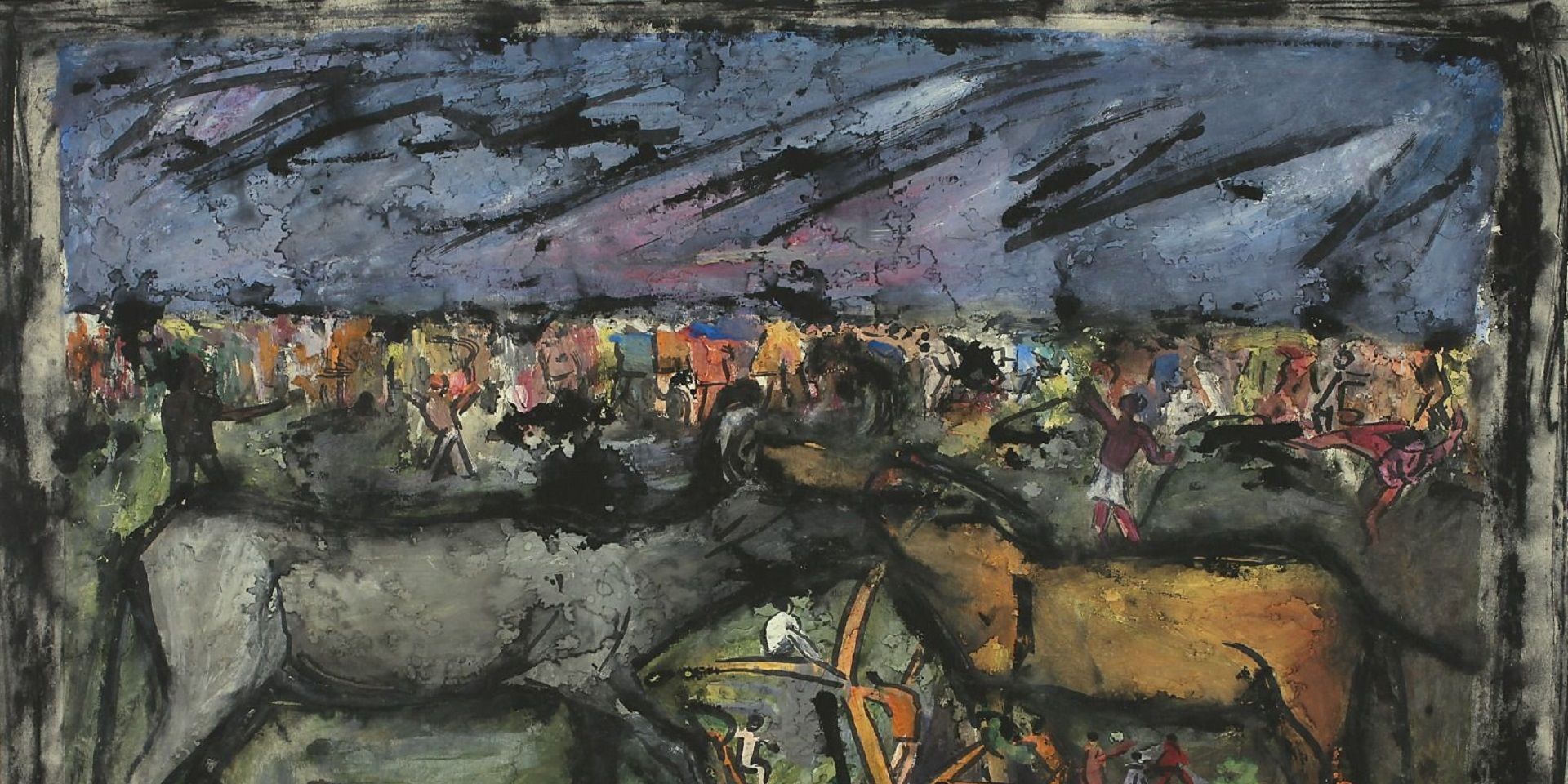

Sewak Ram, Prayers and Recitations at the Muharram Festival, c. 1820-1830, Opaque watercolour on paper, 17.0 × 23.2 in. Collection: DAG

That shift—from court-based, elite patronage to broader market production—is, to me, one of the most significant transformations in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century South Asian art. While courtly patronage certainly persisted, such as with the Nawabs of Awadh or Bengal—something beautifully documented in Kavita Singh’s work on Banaras and the Ramcharitmanas—many artists were displaced from imperial workshops following the decline of the Mughal Empire. These artists, highly skilled and trained in elite traditions, now had to adapt. At the same time, there were also artists trained in popular forms—sculptors, illustrators, painters—who needed new forms of patronage and began working for a commercial clientele.

This transformation reflects a broader shift into a corporate, market-oriented world—a world we are still living in today. And in many ways, that is where the significance of Company painting also lies. I am starting to think of the term differently now—not necessarily as a fixed category but as a historically contingent one. It describes works produced at a specific moment, in response to a changing world: a new economy, a new audience, and new patrons that has resonance now.

On the stylistic features of ‘Company’ painting:

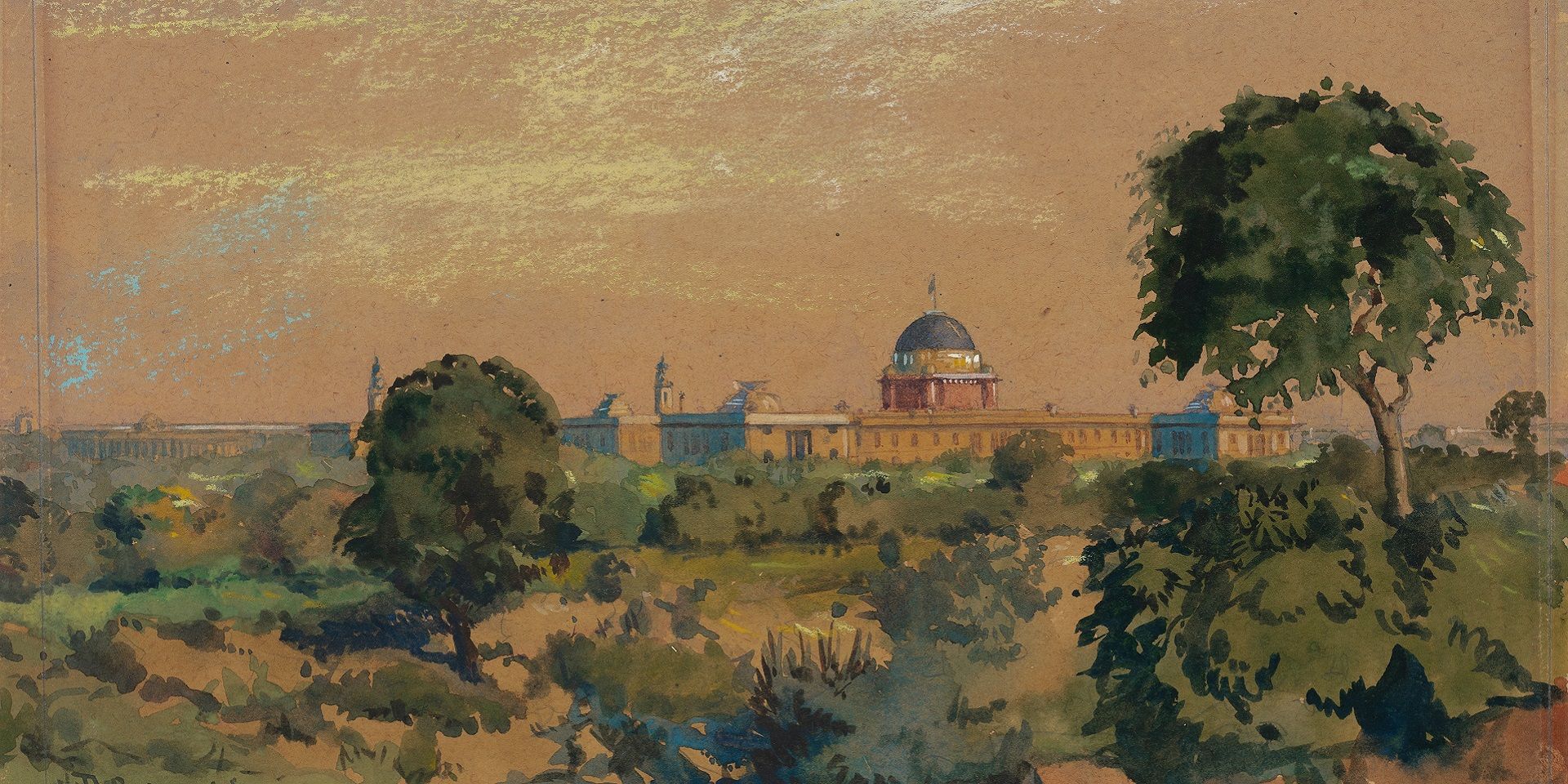

I believe there are stylistic features that make Company painting recognisable—which is one reason the term has endured. The most identifiable visual mode is the scientific, natural history style of illustration—in which a plant or animal is displayed in high detail against a blank background, which was initially used to document flora and fauna and then expanded to depict people, animals, architecture, and transport. But there are others as well—like the picturesque aesthetic—identifiable by the use of perspective and framing devices, like asymmetrical trees around a subject as well as a muted watercolour palette—that speak to the hybridity of this art. Despite the stylistic diversity, these works are often visibly coherent, partly because the market demanded certain formal qualities like perspective and tonal shadows, and certain subjects like plants and animals, manners and customs, landscape and architecture, and portraiture.

Unidentified Artist (Company School), Common Birdwing (Troides Helena), c. 1827, Opaque watercolour on paper, 8.7 x 7.2 in. Collection: DAG

That said, I also very much appreciate critiques that ask: why is the term defined primarily through patronage rather than through the artists themselves? In William Dalrymple’s remarkable Forgotten Masters exhibition, and Henry Noltie’s excellent contributions to it in particular, they push back against this convention of emphasising the elite patron rather than the maker. It is an issue of hierarchy in art history, and an historical attention to elite and courtly arts—though art history has been shifting away from this elitism toward the social history of art, and more recently toward the ephemeral and even absent in art, for many decades. But it still contributes to why we have struggled to develop terminology for a popular or market-driven art.

Terms like ‘bazaar art’ or ‘popular art’ do not fully capture it, as Kajri Jain has wonderfully explored. Lately, I have been using the phrase market-oriented art—not as a fixed category but as an attempt to describe a unifying condition: art made for a public, for a wider audience. It is the art I love most, honestly. While I deeply admire elite, refined courtly painting, I find myself drawn to art made by and for the people. It holds emotional and cultural resonance in a different way.

On the historical background for ‘Company’ painting and its locations:

Founded in 1600, the East India Company was established as a joint-stock trading enterprise with a royal charter granting merchants in England exclusive rights to trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. Although not formally operating in the Atlantic, its commercial influence extended globally, with access to trading posts in the Americas and the Caribbean as well as in Africa beside the Company’s primary settlements in Asia. Driven by shareholder profit rather than ethical governance, the Company’s focus shifted over time from trade to territorial control. By the mid-eighteenth century the Company had evolved into a colonial power, operating both as a commercial enterprise and a sovereign authority. This dual identity had lasting consequences for the regions it controlled and is critical to understanding Company painting as well. Much of what we now define under that label was created during the period when the Company functioned not just as a commercial entity but as a ruling authority. And the art reflects that: it was deeply tied to the colonial agenda of collecting knowledge—about India’s natural resources, its crafts, its people—ultimately in service of expanding and optimising trade and revenue. The Company introduced a different intensity of a for-profit motive from the usual investments made by Indian rulers until then. Its singular goal was revenue—measured in dividends to investors, not in public good. And the consequences of that model were devastating, both then and in the long-term.

|

Murshidabad Artist (Company School), Cockscomb (Celosia Cristata), Corn Poppy (Papaver Rhoeas), Silk Cotton Tree (Bombax Ceiba), Tuberose (Agave Amica, Syn. Polianthes), Maulsari, Bakul (Mimusops Elengi) and Dwarf Copperweed (Alternanthera Sessilis), c. 1795, Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 19.0 × 28.2 in. Collection: DAG |

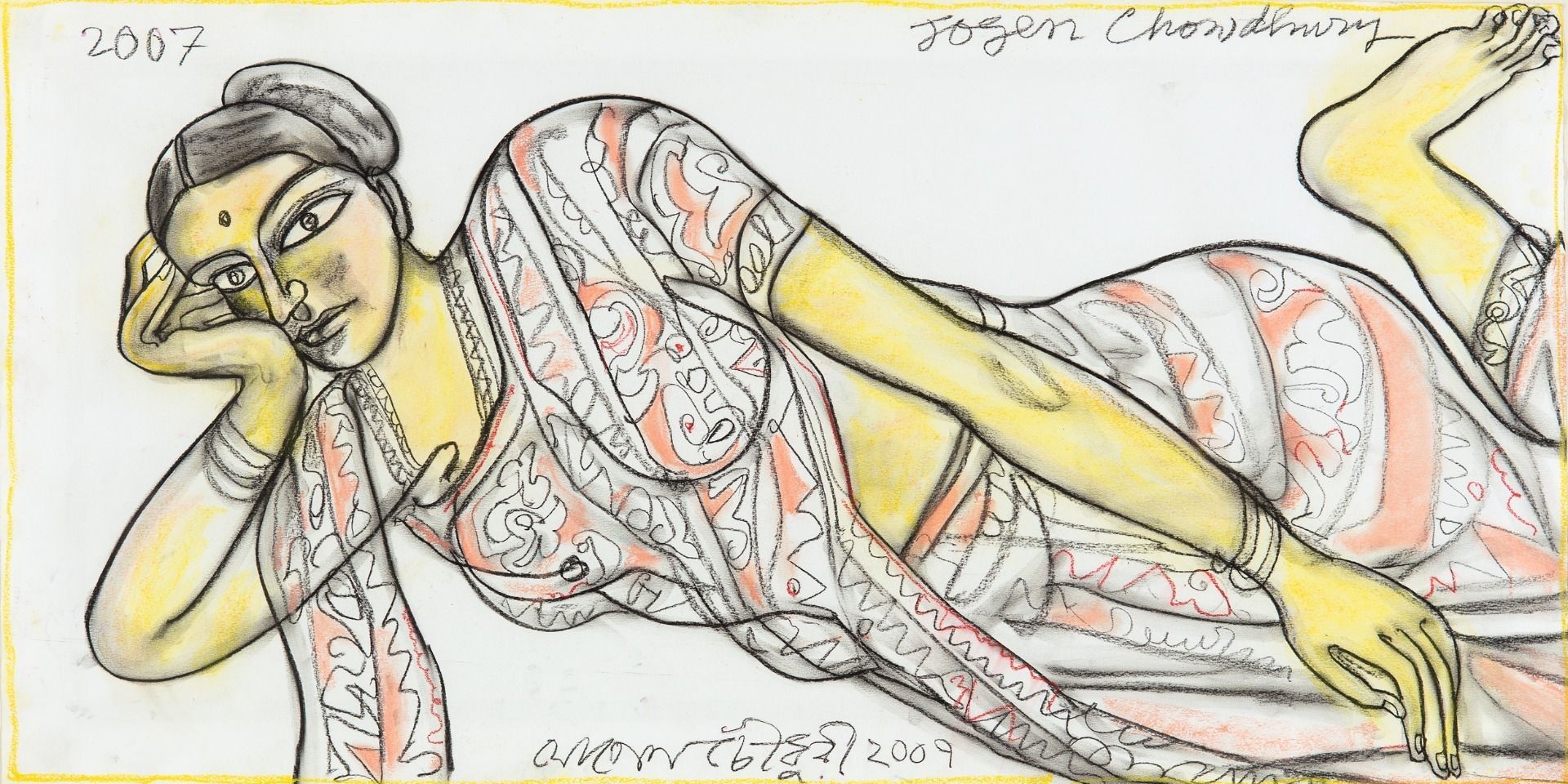

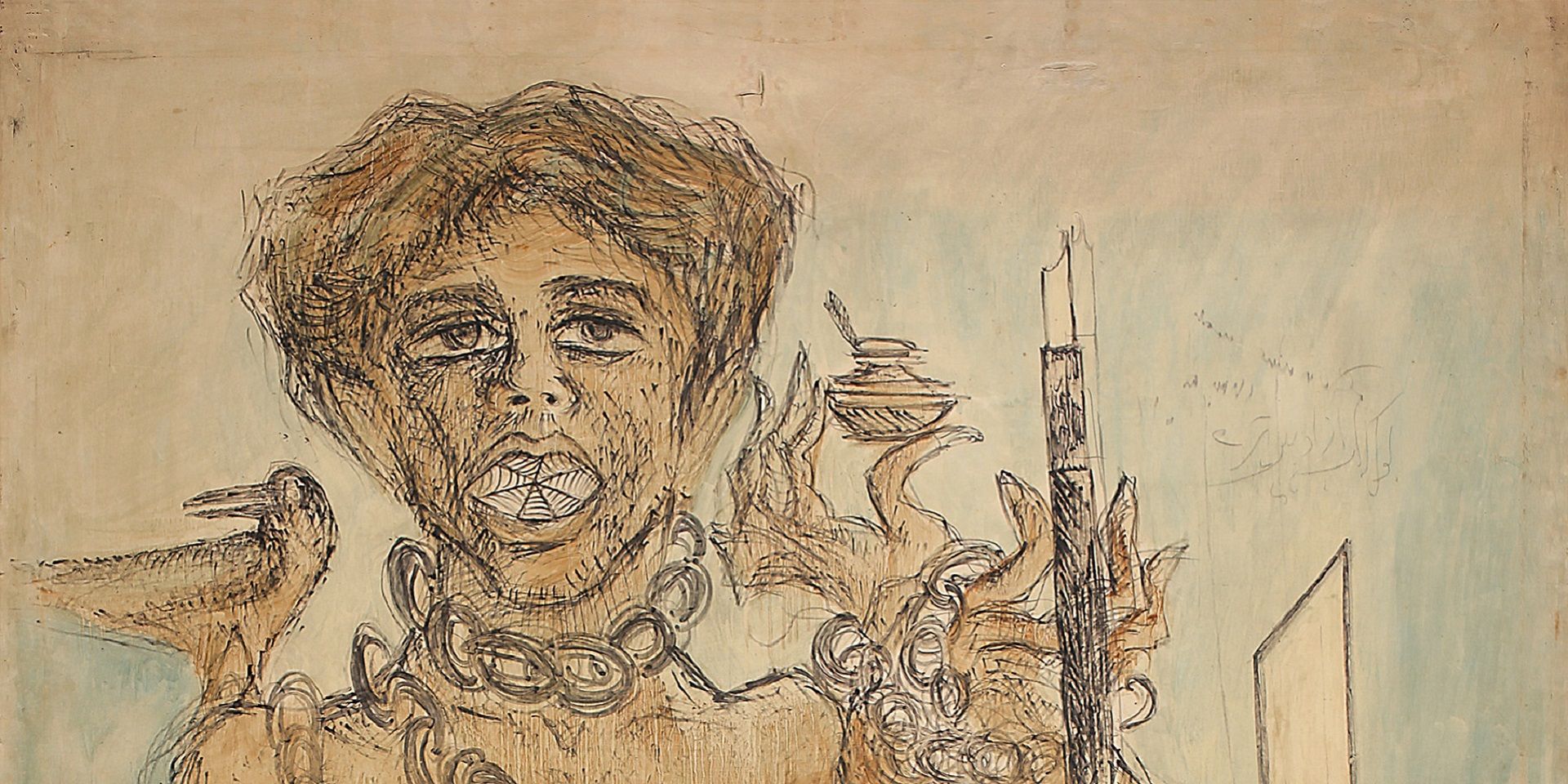

That is why I think the word company in ‘Company painting’ matters. It signals not just a patron or a period, but a particular system: a colonial state that operated simultaneously as a for-profit enterprise. That is a historically specific formation with legacies that continue into our present. And in this context, I'm interested in how we might expand the term Company painting—rather than discarding it, to rethink its scope. Traditionally, it has been used to refer to works made by Indian artists for Company patrons. And while my work is driven by the ingenuity and skill of these artists, I think there is a risk in defining the category solely through ethnicity. The term itself—Company painting—does not include a racial or national marker. And rightly so because many kinds of artists worked under the Company’s patronage. There were Indian artists from diverse training backgrounds—Mughal, regional, popular, devotional. Sculptors, painters, illustrators—artists who often shifted mediums and subjects to adapt to new patronage. Gangaram Tambat, for example, is a personal favourite of mine because of how flexible and inventive his practice was.

But there were also British artists working for the Company: Royal Academy-trained painters, military draftsmen, amateur women artists. And there were Southeast Asian, Malacca Strait, and Chinese artists producing work within the Company’s orbit, and surely others. Many of these artists were in direct or indirect contact—through physical interaction or through the circulation of artworks and visual styles.

The exhibition Painters, Ports, and Profits at the Y. C. B. A. foregrounds the complex networks of artistic exchange that developed under the British East India Company and beyond. While many works featured were made by Indian and British artists from varying backgrounds in India, the show also explores works made by artists in China and the Malacca Strait as well as the connections between India and China. China Trade painting—a tradition shaped by Chinese artists working for foreign clients—serves as a useful parallel to Company painting, though key differences exist. Notably, while the British East India Company was just one of many trading entities in China and never a colonial power there, in India it exercised direct colonial rule. Company painting in South Asia is deeply embedded in colonial systems of knowledge, resource extraction, and visual classification. The opium trade exemplifies this: colonial control over India enabled them to systematize the production and sale of opium to dominate trade with China and led to the addiction of millions of people, and, of course, the Opium Wars. The exhibition aims to think about Company painting as a dynamic style that was shaped by power, profit, and cross-cultural exchange.

|

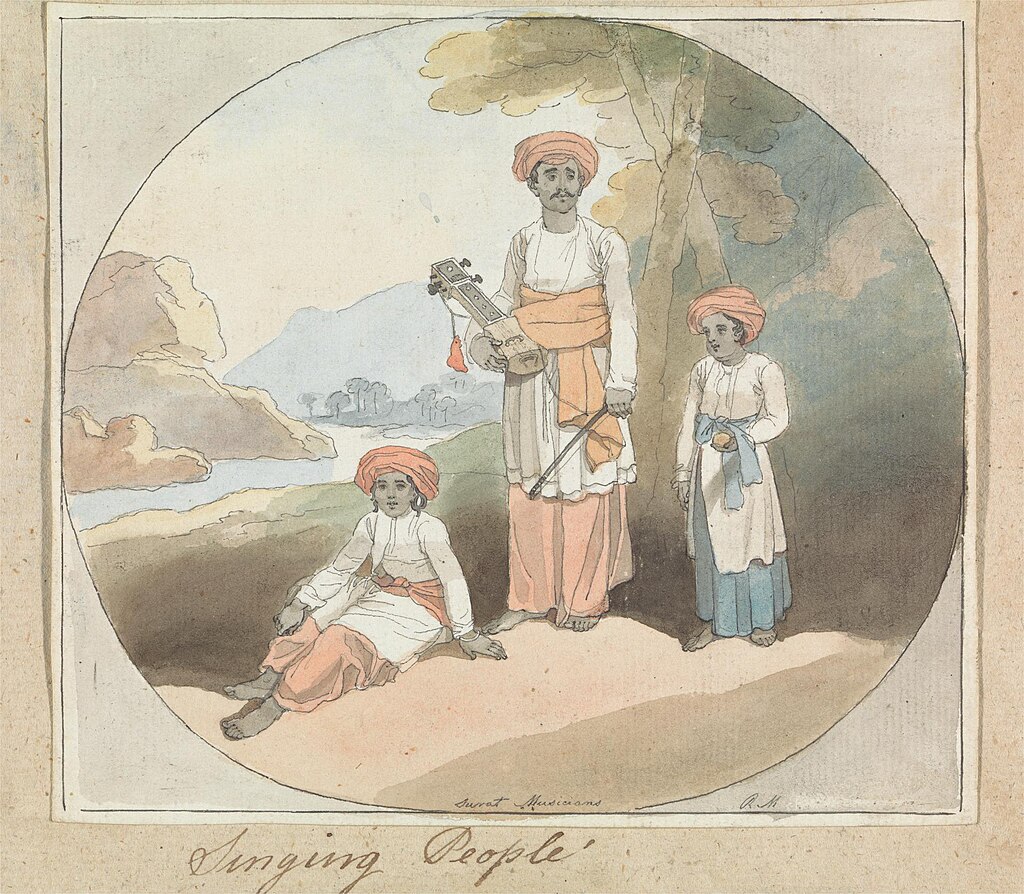

Robert Mabon, Surat Musicians. Image courtesy: Yale Centre for British Art and Wikimedia Commons |

This is the first of a two-part conversation with Holly Shaffer. The second part will be published on 1 July, 2025

’Conversations with Friends’ is a series where we speak with inspirational figures from the art world who are working behind the scenes

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025