Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

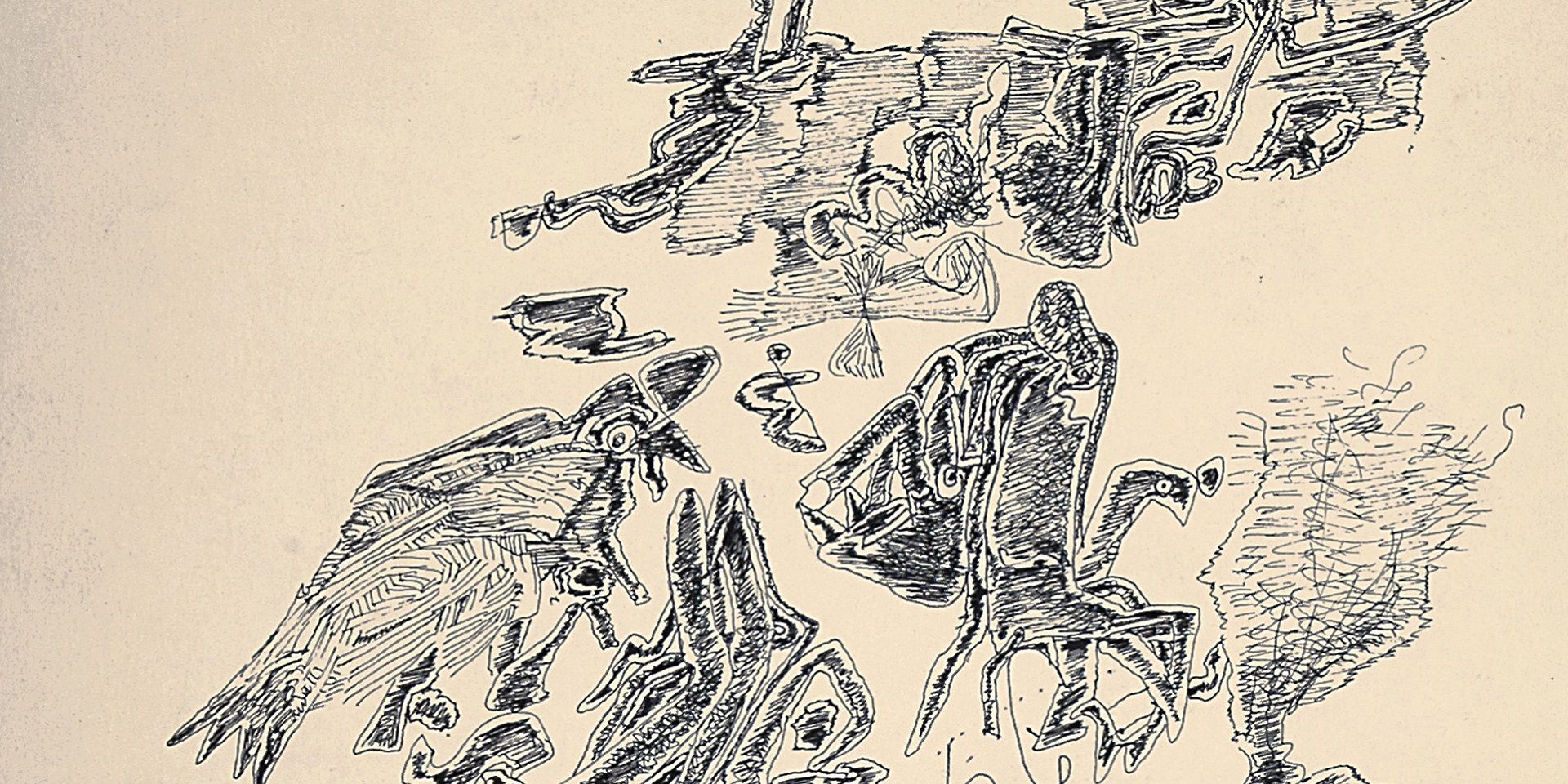

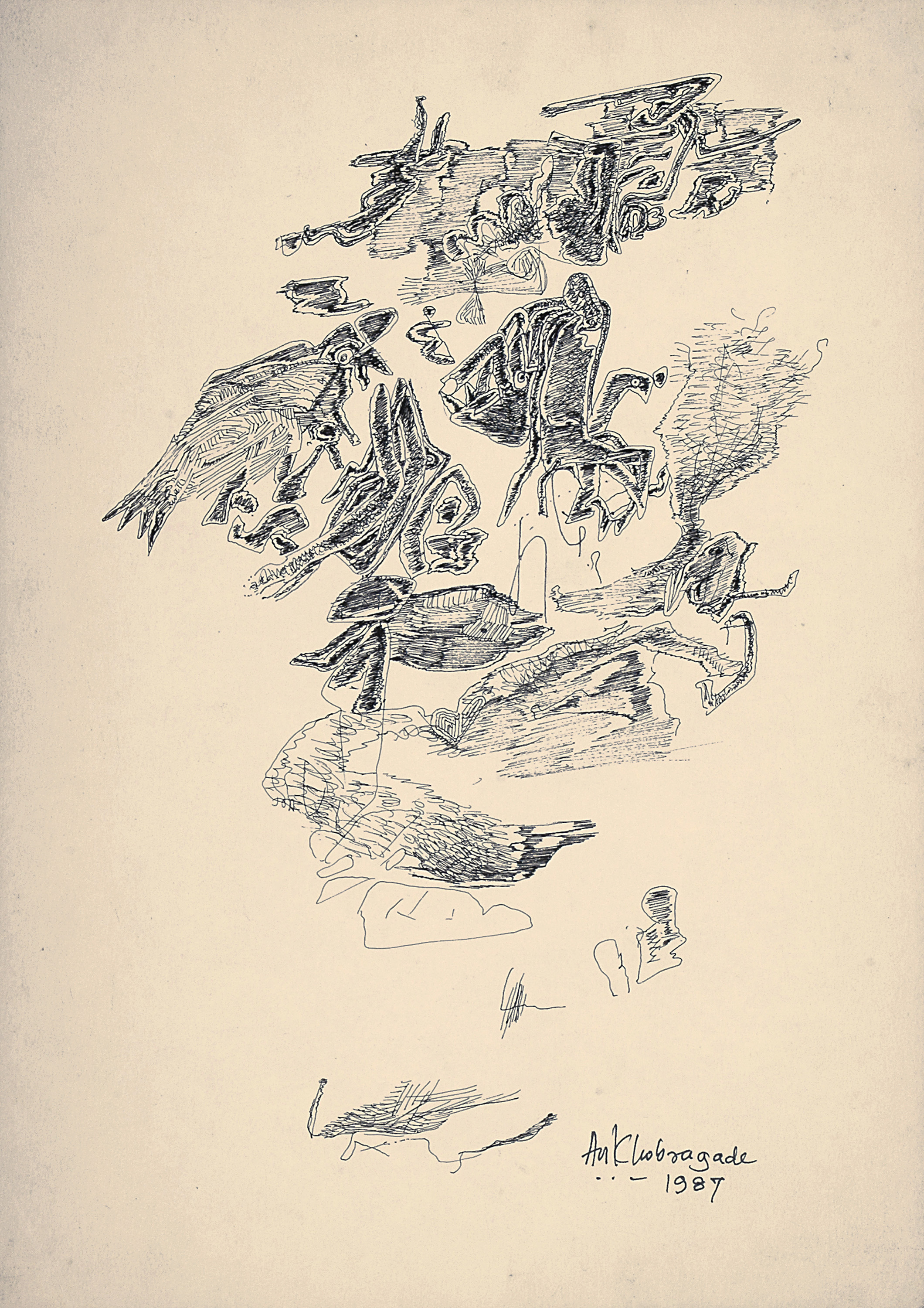

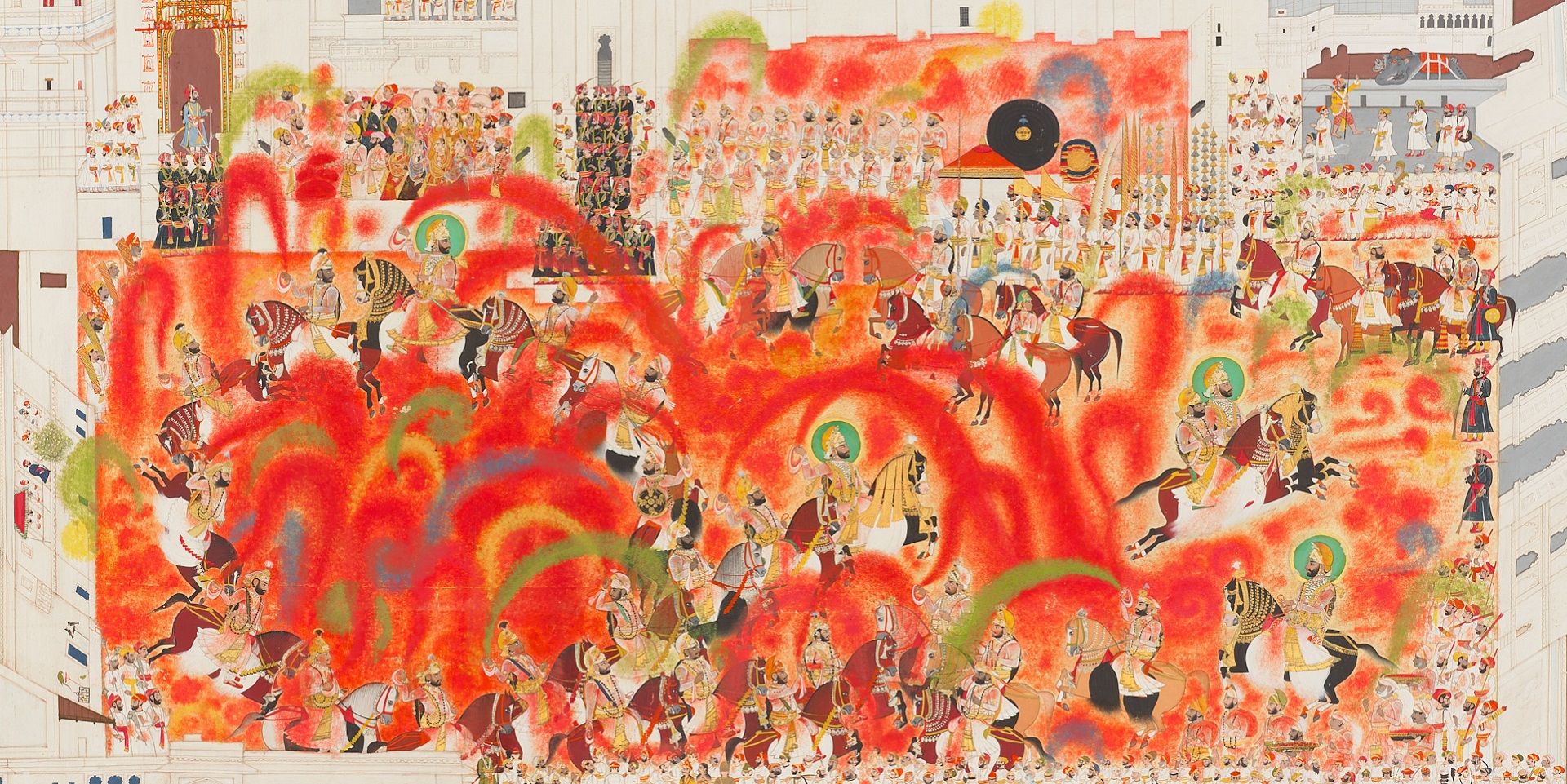

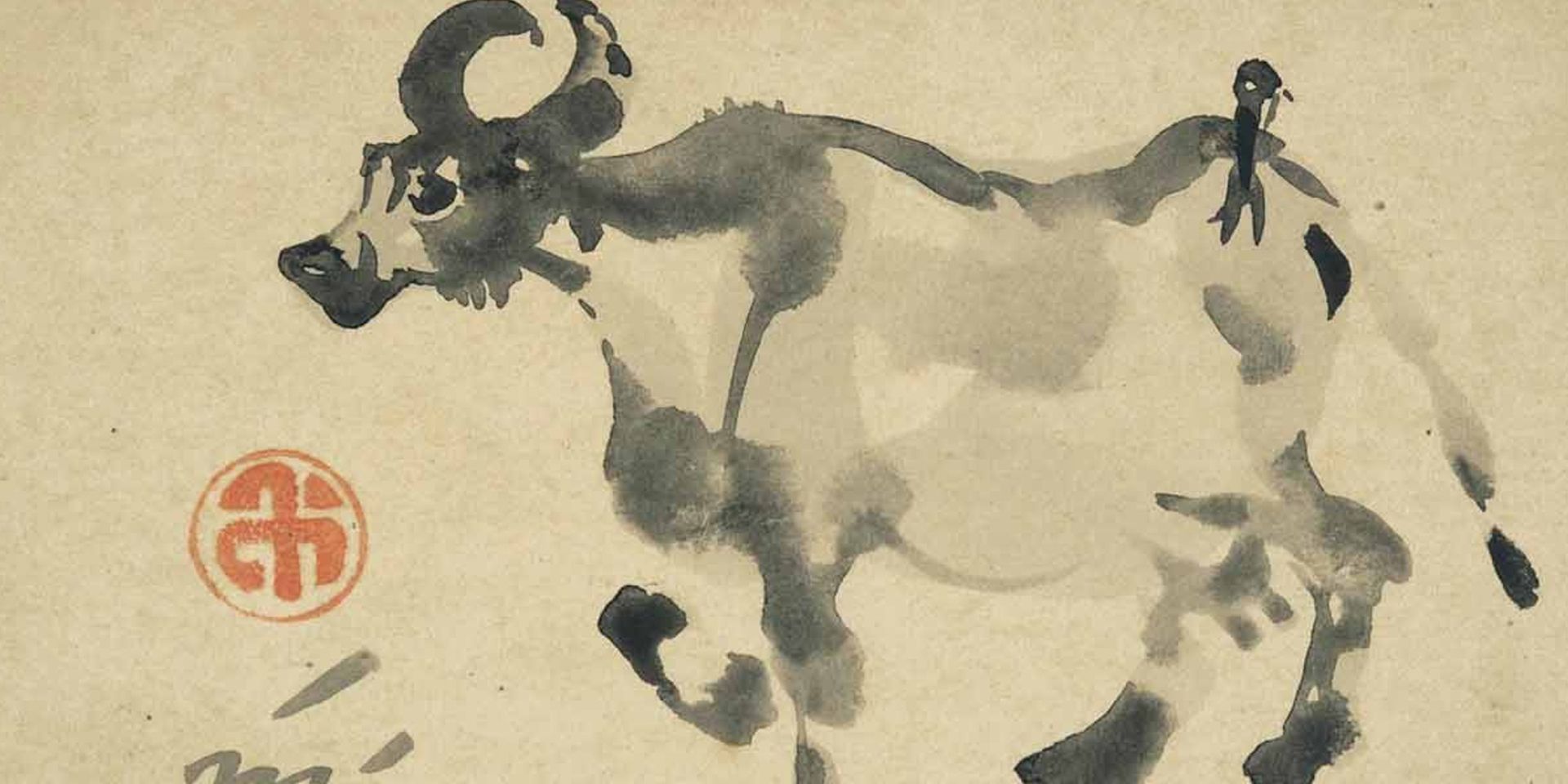

Ambadas, Untitled (detail), Ink on paper, 11.7 x 8.2 in.,1987. Collection: DAG

A well-known poet and essayist, Prayag Shukla is also one the foremost writers on art in Hindi. He has authored monographs on artists like J. Swaminathan, M. F. Husain and Ambadas, expanding upon these artists’ relationships with local institutions and contexts of art-making in India since the 1960s.

As a close observer of the art scene in northern India, he has also written catalogue texts for members of Group 1890. He spoke to the editors of the DAG Journal about the environment of art writing in Hindi and his long relationship with the artist Ambadas.

Q. Most Indian modern artists have kept up a stream of writing as a critical and even poetic and creative supplement to their art making—from Abanindranath Tagore to Benode Behari Mukherjee in Bengali, Prabhakar Barwe in Marathi, Bhupen Khakhar in Gujarati, and Ram Kumar in Hindi, among many others. How do you see this relationship evolving over the twentieth century between art and writing as critical practices in Indian language spheres?

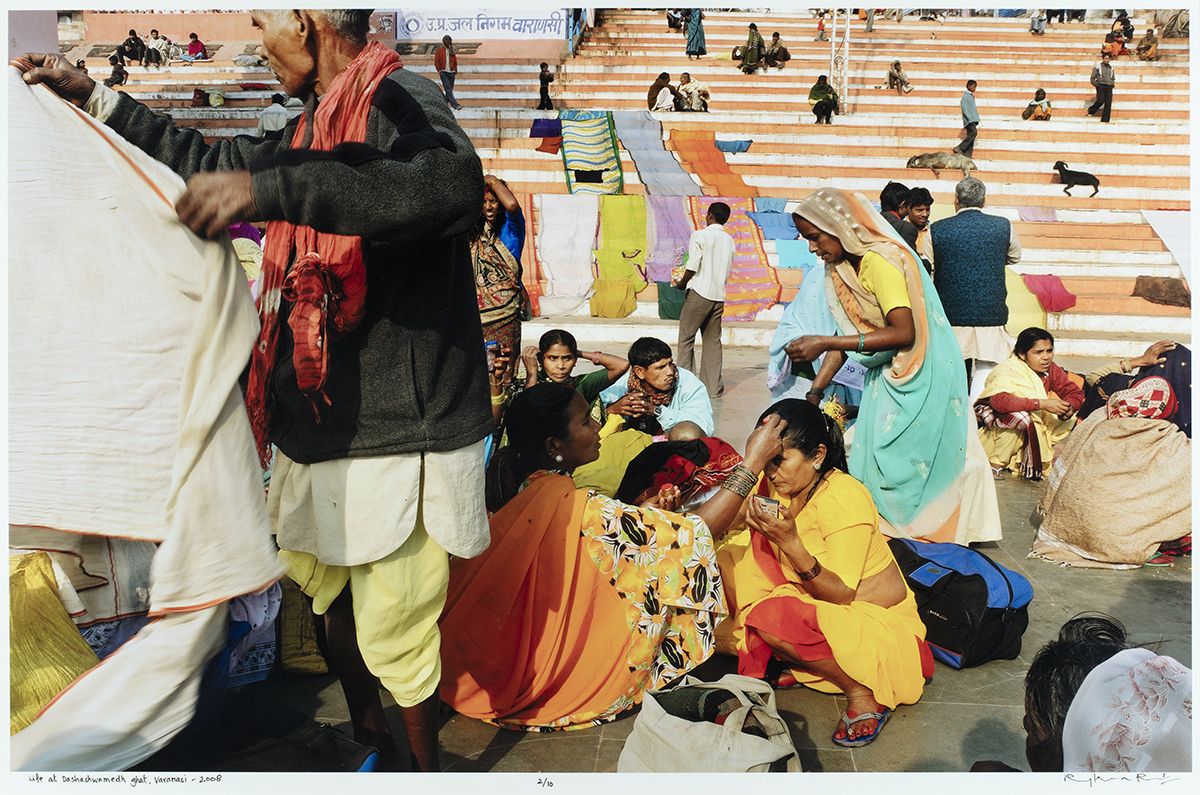

Prayag Shukla: Yes, I am quite interested in this because I think that Indian languages must have something on art writing, but it has not been to our satisfaction so far. Some writers and critics have been writing in Hindi for a long time, but the kind of writing we would require at the moment about modern and contemporary art has not been much. Otherwise, it started with writers and institution builders like Rai Krishnadasa, who built the Bharat Kala Bhavan (in Varanasi), and also collected a lot of books which are quite valuable. And then his son, Ananda Krishna continued the work. There have been many others also, like Dr. Gopi Chandra, Vashudev Saran Agrawal—these are names to remember, and their writing also is quite important and significant.

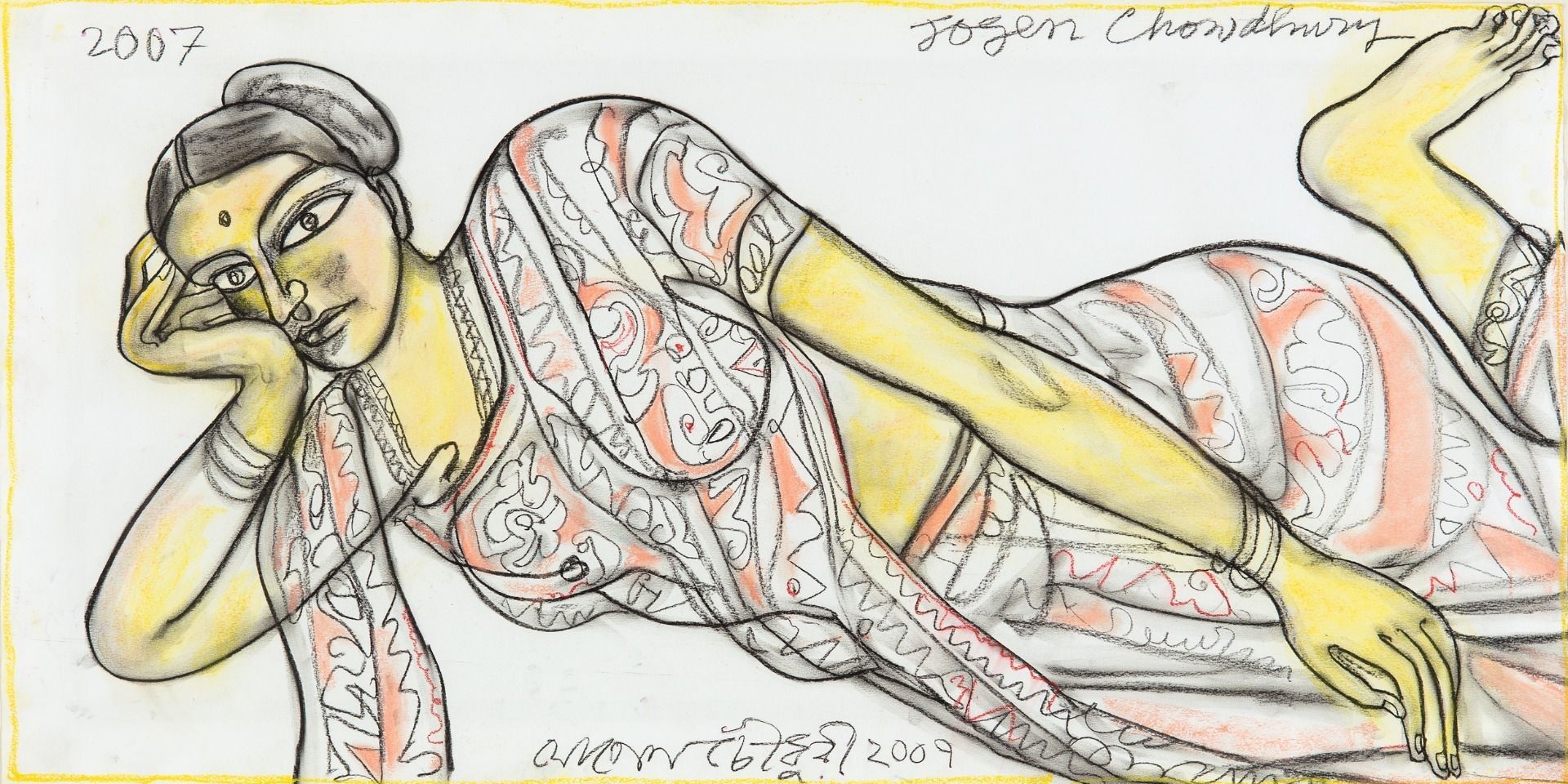

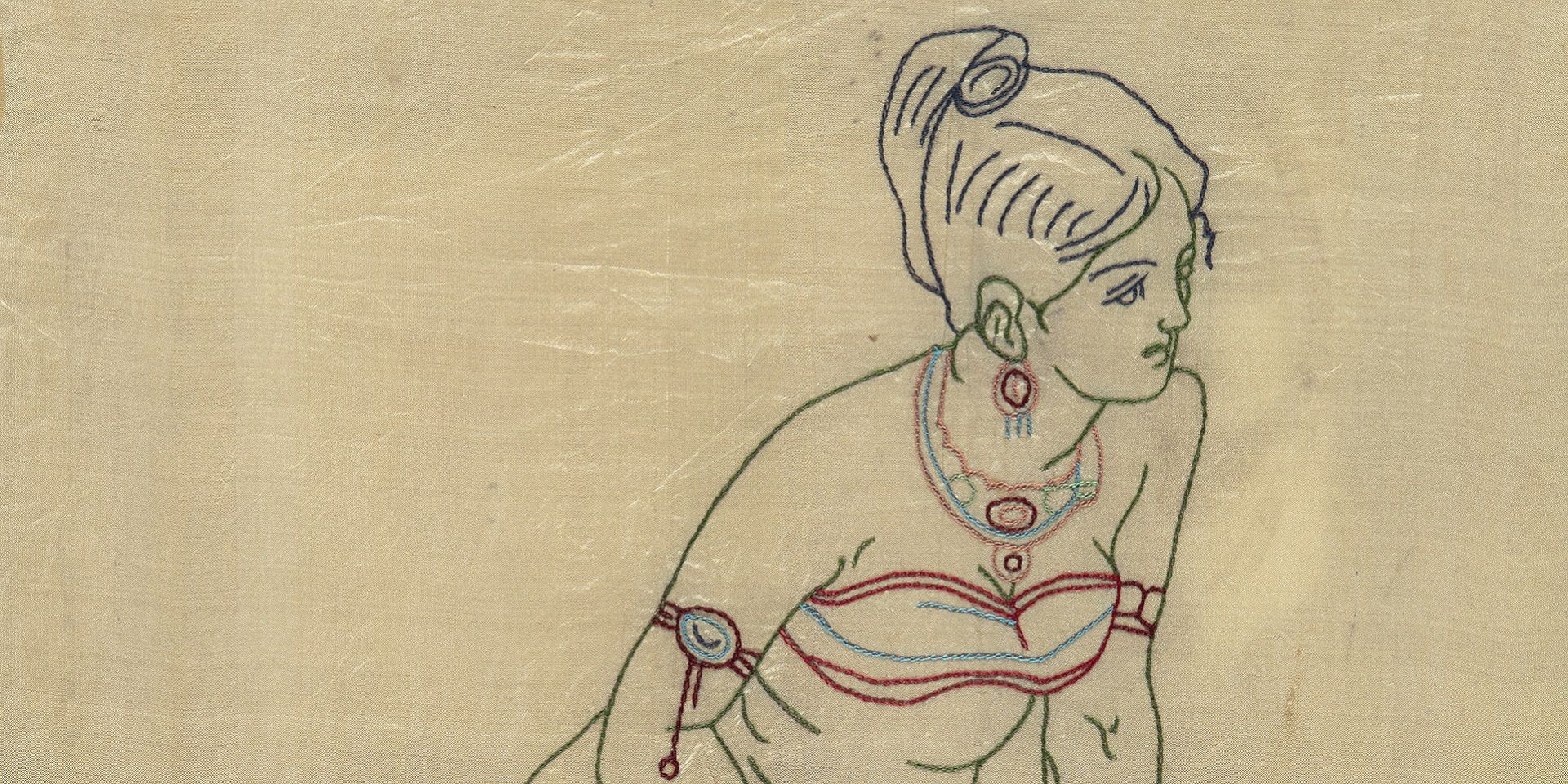

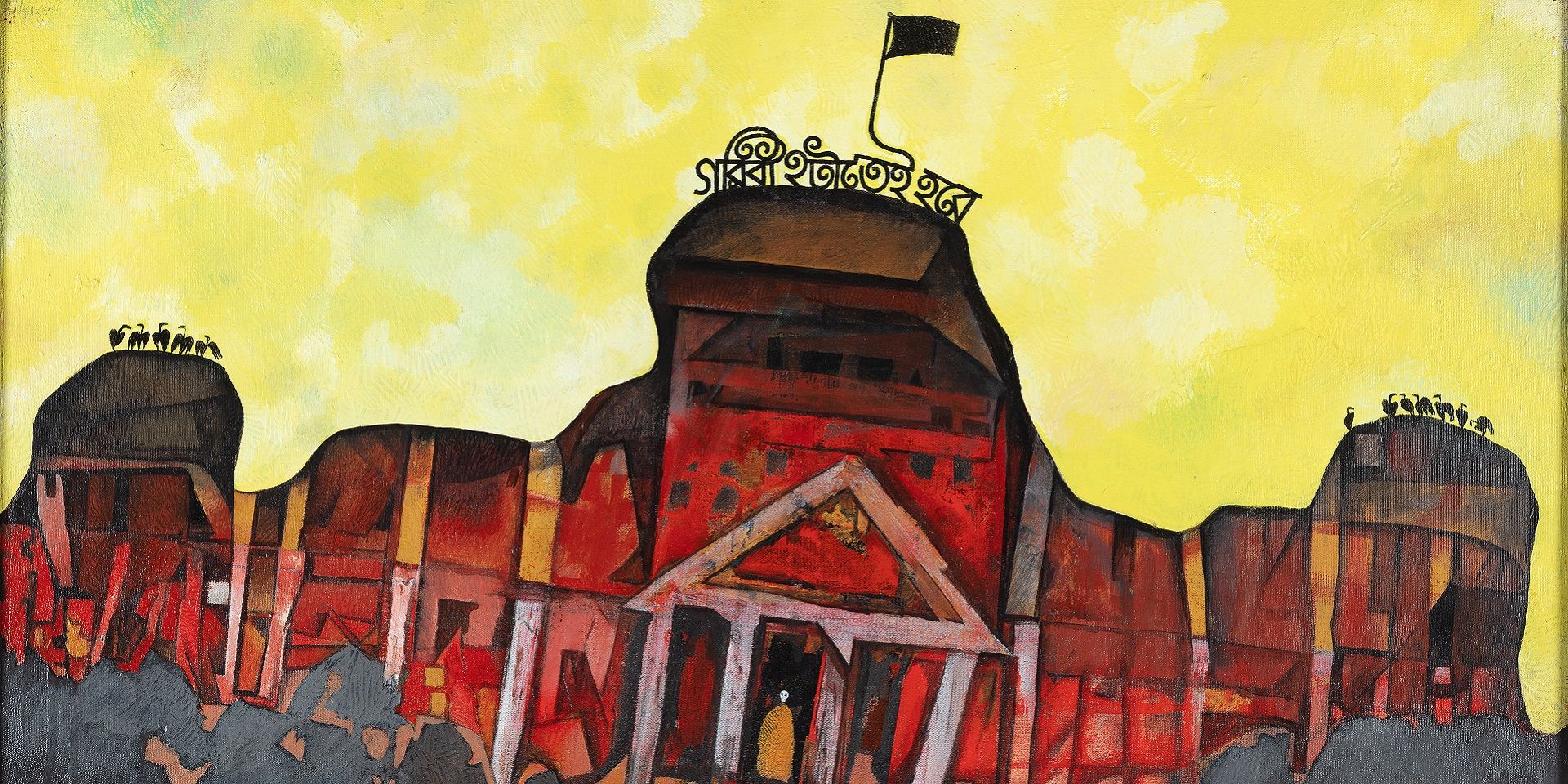

Ram Kumar, Untitled, Ink on paper, 20.7 x 27.7 in., 1965. Collection: DAG

But again, I will repeat that when we come to the contemporary and modern times, there has not been much writing on art in Hindi. Sachchidananda Hirananda Vatsyayan (known as ‘Agyeya’) wrote some articles. In fact, he once wrote in a weekly on the Bengal school of art showing his general interest in the arts. And I feel fortunate that I started my career with him, because he was the editor of Dinaman, a significant weekly published by the Times of India Group and I worked there for twenty-seven years. But ten years of writing for Dinaman every week changed my life also.

Before me, the Hindi poet Shrikant Verma used to write, and so did Manohar Shyam Joshi, who was also interested in films and theatre. He was the kind of person who wrote on perhaps each and every subject in Dinaman.

So they were there, but once Vatsyayan ji asked me to write this column, I wrote it for 10 years. From late 1960s to 70s we covered many stories on contemporary and modern art, focusing on artists like Tyeb Mehta, (F. N.) Souza, V. S. Gaitonde and Ram Kumar. In fact, I once asked Ram Kumar to write for Dinaman and he did. But he wrote mostly travelogues relating to art, from Paris, and once from Portugal, I believe, and other places. So that has been the situation and then my friend, much younger to me, Vinod Bhardwaj, started writing and making films on artists as well. So in bits and pieces, there has been some activity, but not enough since Hindi is spoken in different states and has got a very large audience but to feed this audience, we have very little, even today.

|

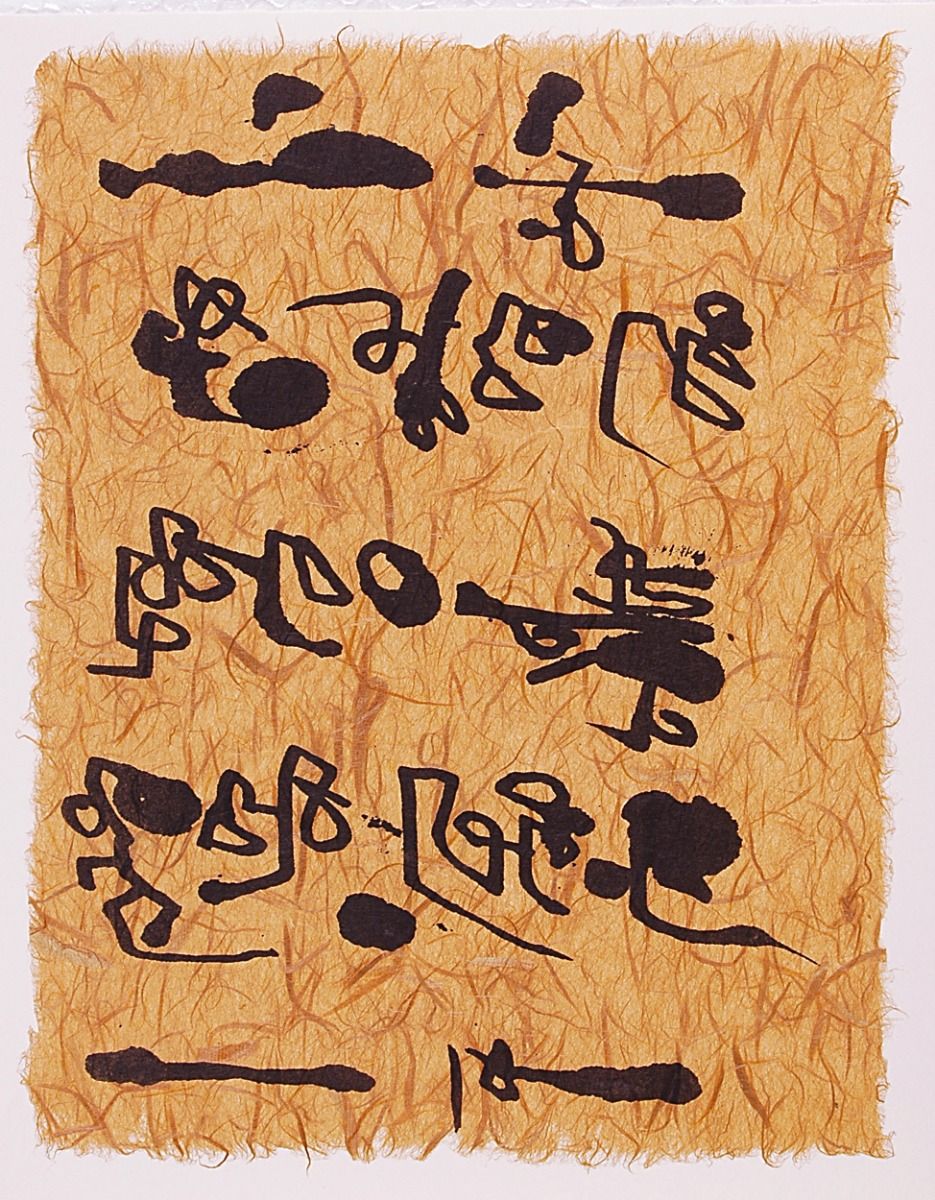

V. S. Gaitonde, Untitled, 11.5 x 9.0 in., Serigraph on handmade paper pasted on handmade paper. Collection: DAG |

To give you an example, about a year ago, I published a book on (M. F.) Husain—a small book—but someone told me that this book on Husain is the first one in Hindi. I was quite surprised to hear that and so was my publisher. But then he inquired, and we found that it is true. I have also written a book on Ramkumar recently, since there was no book on his art. And then slowly, I have started writing small books (on artists). I have written about Ambadas in a book called Apratim Ambadas (The Incomparable Ambadas)—it was published recently—and a book on Manjit Bawa. So slowly, gradually, we are increasing our efforts.

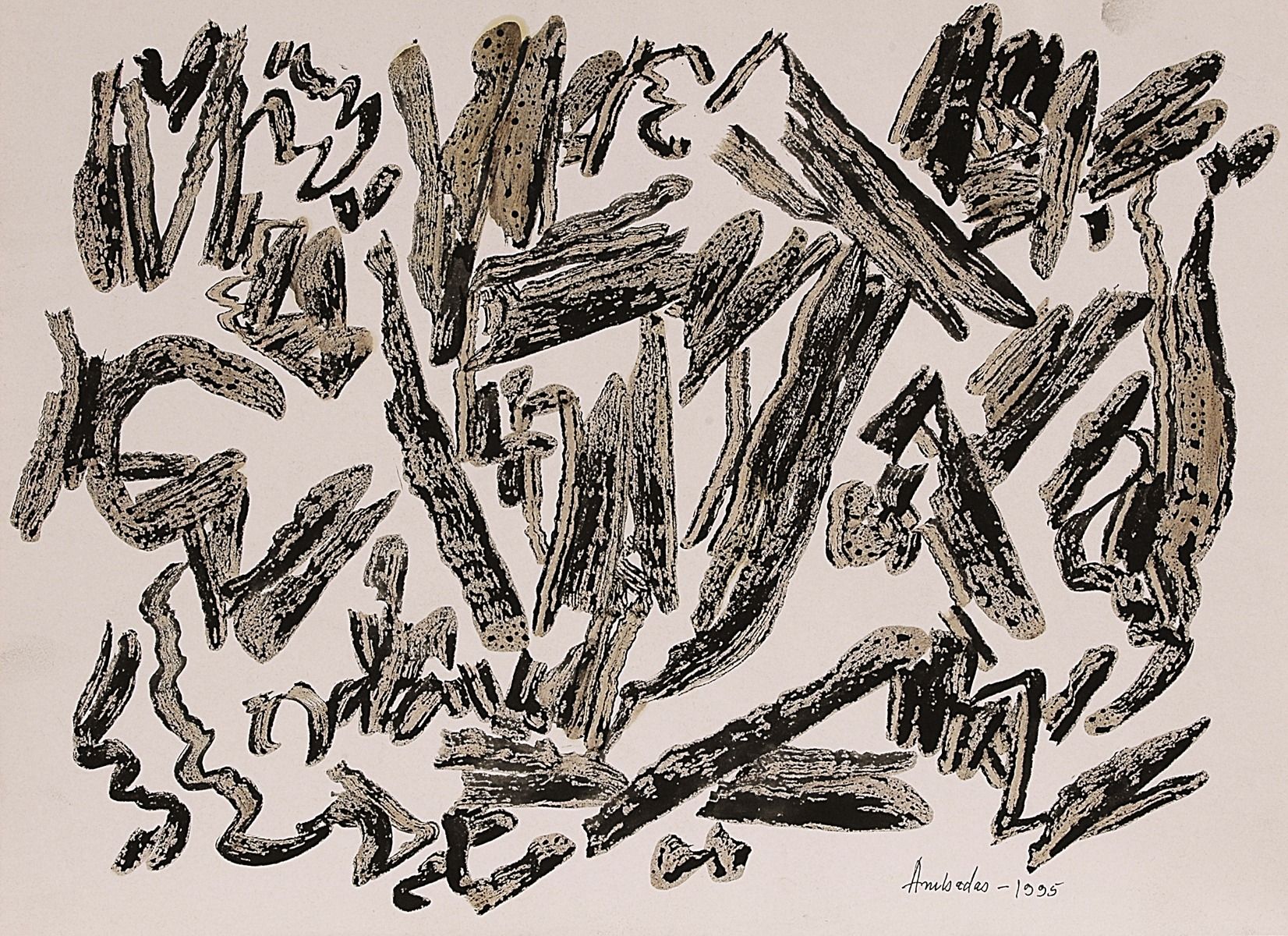

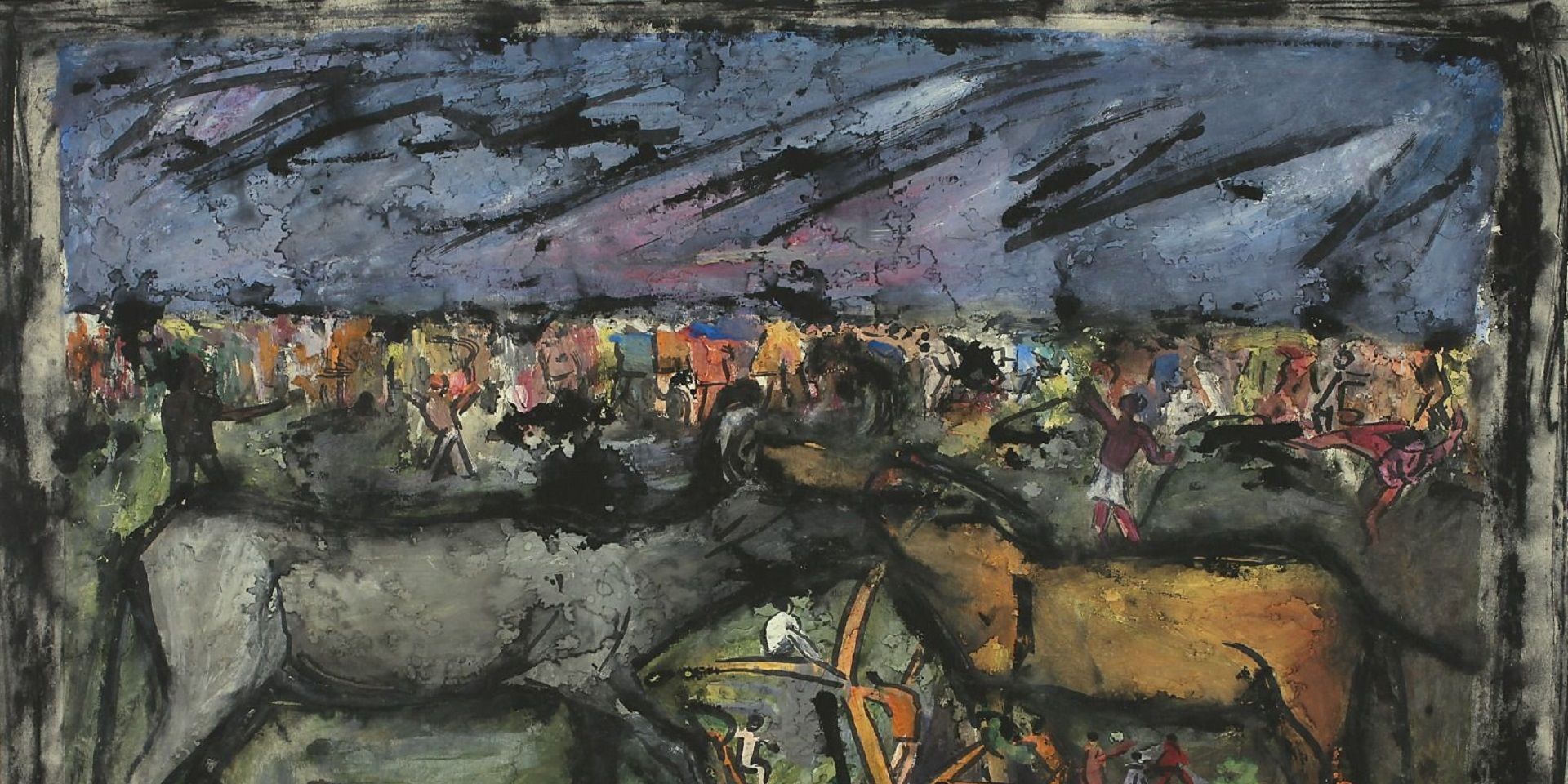

Ambadas, Untitled, Oil and ink on paper, 11.7 x 16.0 in., 1995. Collection: DAG

Q. Talking about writing and the relationship it has to modernist practices in painting, how do we look at artists like Ambadas, who rejects explication and figuration, and emphasizes physical acts and gestures in painting. He appears to be pushing beyond language in his works, and you have quoted him as describing his works as ‘wordless scripts’. And a script implies a language, right? So how do we appreciate his art within the terms of this language that he is trying to innovate?

Prayag: Ambadas was a kind of artist (for whom) no one knows how it happens, what chemistry goes into it and how they are made. But when I met him for the first time I could see that in his persona there was something of a pure soul, and he was a very creative person. And I came to know him rather intimately over the course of time. I would often find him talking about art in a very different manner. And he believed that art should arrive like an organic thing. No effort should be made there, because then that would be ‘art’, not creation. In fact, only the creative act is important. And that is what he did. For him painting was an iterative act and very different from someone like Jackson Pollock, because Pollock approached his work with some thought, and some anticipation of results.

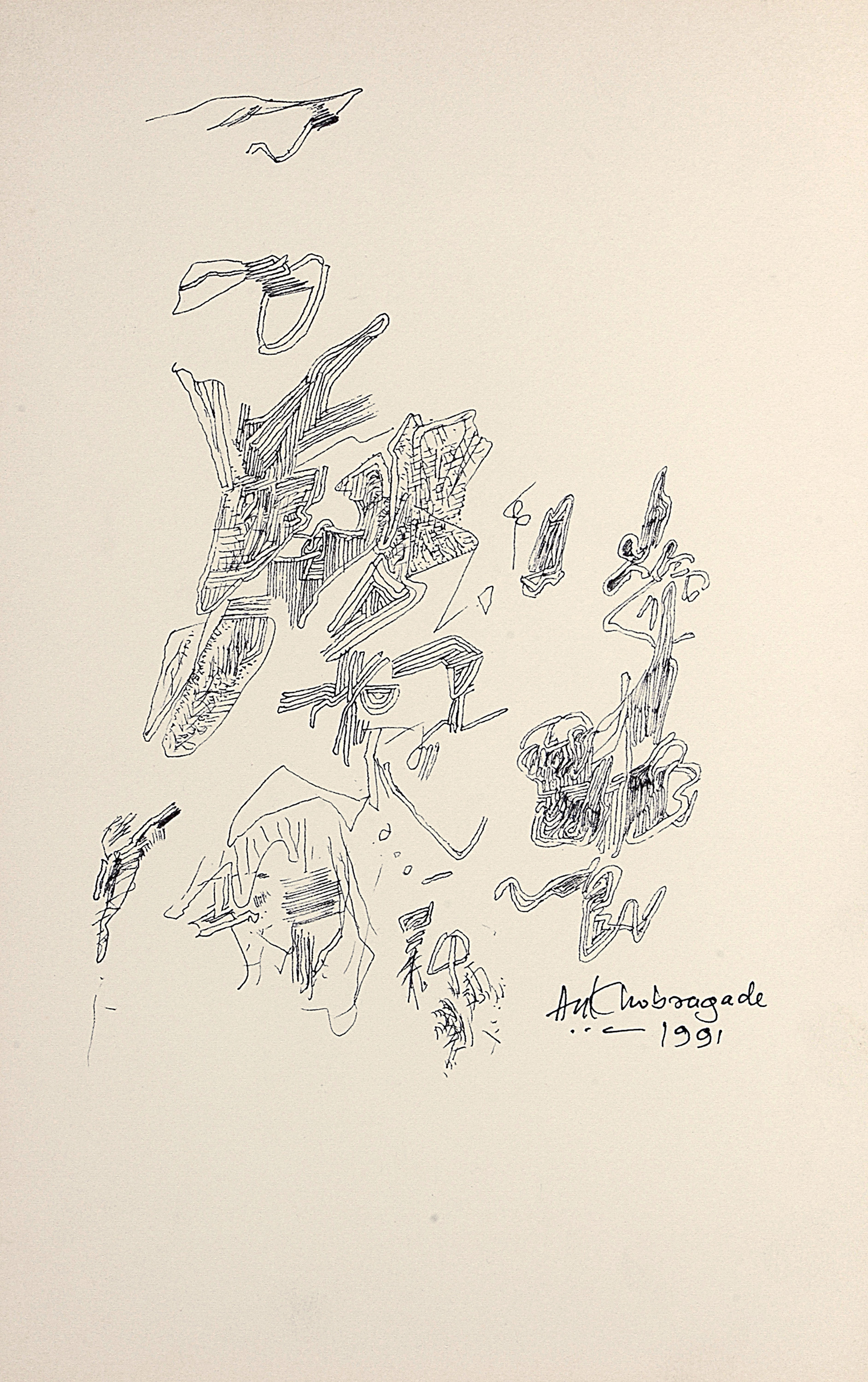

But Ambadas was very much a painter. We know he believed in just the act of painting, the act of doing something as painting. He once said a very unusual thing, which is quite important, when someone saw figures in his drawings, some animal figures, and some other figures. So when he was asked how that happened—because he was supposed to be an abstract artist—he responded by saying that no one should stop midway for these considerations. What is happening on the canvas or paper, you should take it as it comes. So, if we look at his art from this point of view, he was not only an abstract artist, but he was also an artist who believed in forms, who believed in images as they would emerge. He said once that he also thought about his art: ‘it is not that I don't think about my art, but I think only when I have finished,’ which I thought was quite beautifully put.

‘When the painting or drawing is in front of me—my own painting or drawing—only then I start thinking about how it happened, what it is saying.’ So he's not against interpretation, or against the act of decoding his paintings or drawings, or interpreting it in some way.

Q. I think a lot of people have also tried to describe his forms as drawing from the language of calligraphy, which occupies this position between writing and image-making. How do you see this relationship between text and image in Ambadas? As you put it really well just now, he begins to think about his process after making a work of art, so do you think he is drawing inspiration from any other artists around him?

Prayag: He must have been, because no artist, even one of the stature of Ambadas, can escape influence. And I think all of them in Group 1890, because he was a member of that group, influenced each other. And in this group, all of them liked Paul Klee in one way or another and talked at length about his works. Ambadas, was a very close friend of J. Swaminathan, and he held him in great regard and respect, and had a bond with him.

J. Swaminathan, Untitled, Oil on canvas, 11.2 x 15.2 in. Collection: DAG

They would talk frequently, at times endlessly, and as Swami himself has said, they would fight at times on some issues and refuse to agree with each other. I have been witness to such discussions also, because I've been very close to Swaminathan too. I have written his biography very recently for the Raza Foundation and I have learned many things from him. I have spent most of my time with the members of this group–such as Swaminathan and Jeram Patel, about whom I have also written. I have written the text for about six of his catalogues, along with Swami and Ambadas.

So spending time with them has been an education for me. I have learned many things from them, especially Ambadas, because he would talk in a manner which was quite warm, quite peaceful. At times, he was very strong in his convictions and at times, very softly, he would put something about himself or what he was thinking.

I would like to give one example from the time I visited him in 2009 in Oslo (Norway). My younger daughter—who has since passed away in 2020 due to cancer—was in Norway then, in a city called Trondheim where she was working. And she asked me, ‘Would you like to meet Ambadas ji?’ She also knew him from childhood, because Ambadas would come to our house whenever he would visit from Norway, or even earlier when he was still living in New Delhi. So I said, of course, and we both went to Oslo and went the very first evening. We went to his house and had tea. And then his wife Hege started complaining, saying, ‘Look, here is your daughter, she has come only a few years ago and how fluently she speaks Norwegian and Ambadas has not learned a single word of Norwegian.’

|

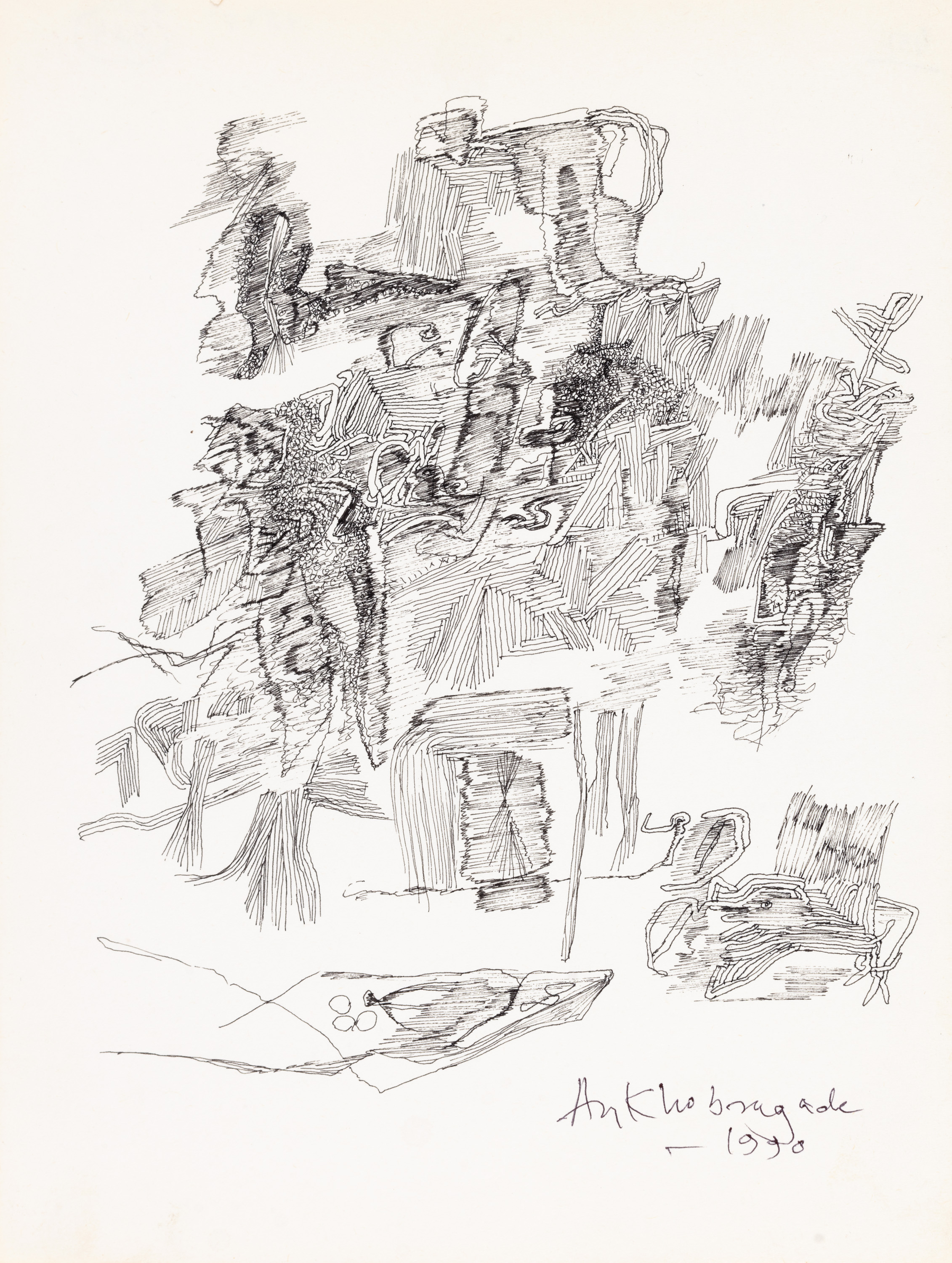

Ambadas, Untitled, Ink on paper, 9.2 X 7.0 in., 1990. Collection: DAG |

(Hearing this) Ambadas ji walked slowly towards me and said something like ‘Prayag ji, main to bhasha ko hi hatana chaahta raha hoon’ (Prayag ji, I have always sought to transcend language itself). It was a very significant statement and I could understand that what it meant was, ‘I have wanted to work without thinking in language. That language should not come between me and my work.’

I told Hege that look something very significant has been said right now. We can see the relationship of an artist with language, but it can also be a kind of relationship where you don't want any language at all.

He was making his strokes, not always intentionally, and it so happened that his strokes started to look like calligraphy. So that is another thing that one can say, that he wanted to create his own script knowingly or unknowingly. But without words. It was just his script, which has of course meaning and you have to interpret it—according to the colours, forms and images.

There is another thing I would like to emphasize about all these artists, including Ambadas.

Once Swaminathan, in his magazine Contra, wrote a beautiful piece about the image and there he says any painting or work of art is about itself. It does not represent anyone else or anything else.

If you see things from that point of view, you will realize that each and every work of art has its own reality. The whole thing changes our perception of art. And Swami said one more thing, that if the image is strong, if the image is real, then we would go by that image only.

|

Ambadas, Untitled, Ink on paper, 10.7 X 7.0 in., 1991. Collection: DAG |

Q. I want to ask about his relationship with Swaminathan and Bharat Bhavan. What do you think Ambadas was trying to do, or what do you think he got from his time when he was working at the Bharat Bhavan—was he interested in folk forms or, was he trying to do something that was personal?

Prayag: Ambadas went for a residency at Bharat Bhavan. Swami was about to leave Bharat Bhavan then and he wanted Ambadas to leave too, because he was worried for him. He was worried that what was happening at Bharat Bhavan at the time would perhaps not be comfortable for Ambadas, because a lot of discussions and writings in newspapers were going on against Bharat Bhavan then.

But Ambadas refused to leave, saying that he will stay there and do his work. He did not want to participate in the politics that was going on around him there. He was simply there as an artist who worked by himself.

It also takes some courage to get settled in a foreign country when you are more than forty-years old and start your life again as a person and as an artist. So he was quite fearless in this sense.

He led a life that took him to many places, including Burma (now Myanmar), that he spoke about, and would often take up odd jobs to support himself.

So finally it was good that he met with Swaminathan and some others and got settled in Delhi for a few years and he started working. I would say that it is was a fortunate moment in our contemporary art. Because if you take away the art of Ambadas from this period, you will find a great void. I see it that way also, whenever I think about his works.

|

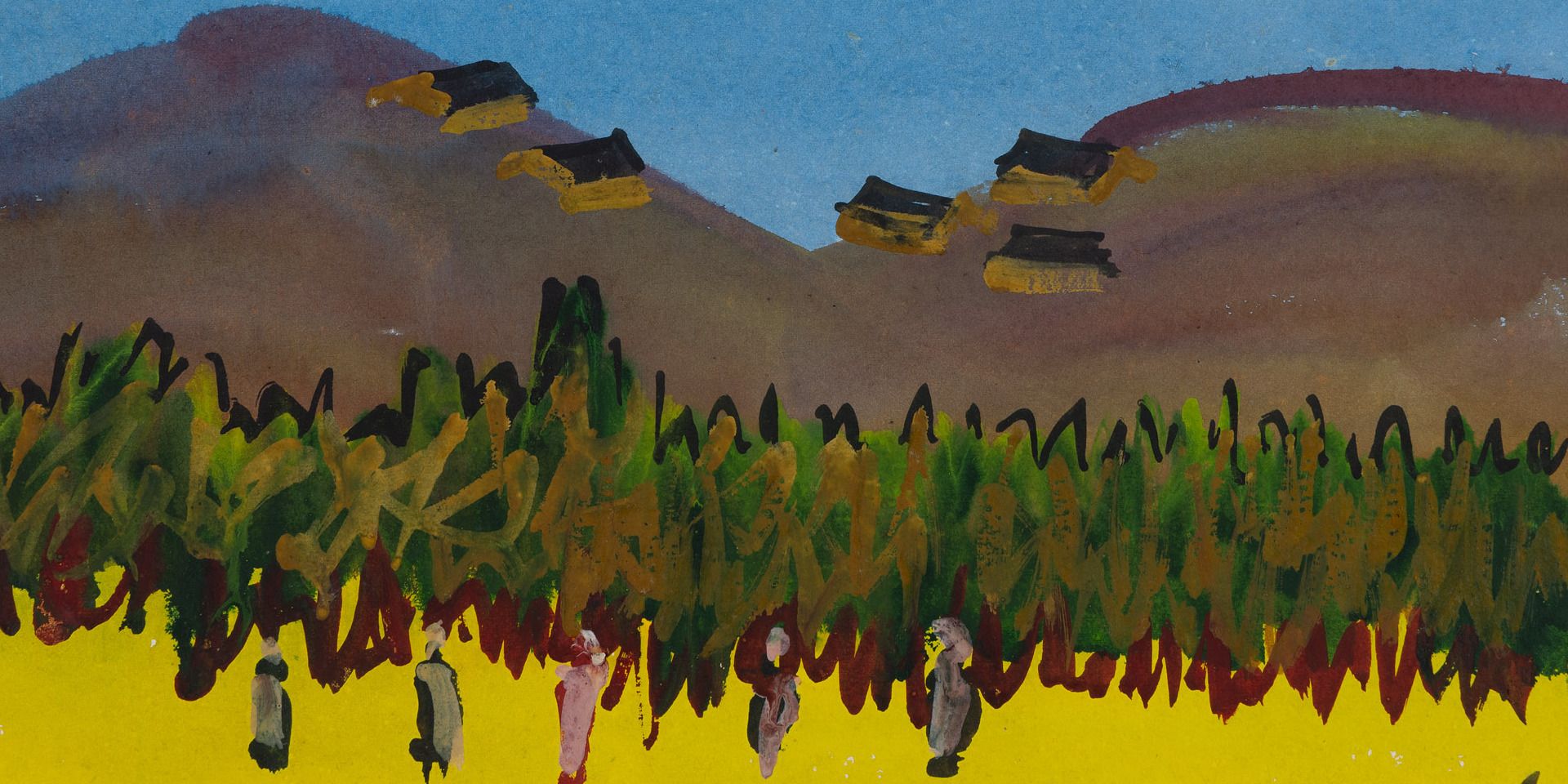

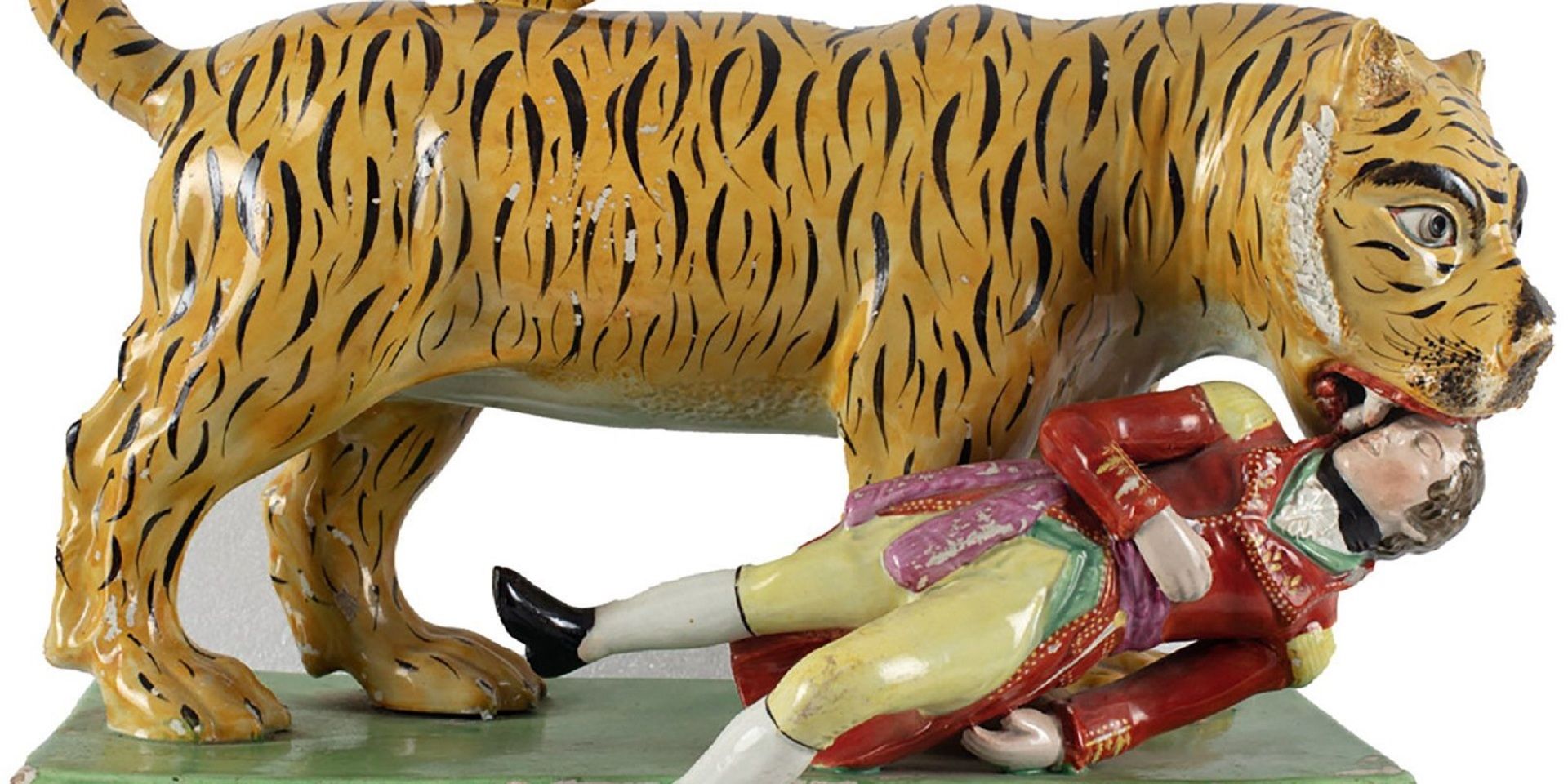

J. Swaminathan, Miniature Painting, Oil on canvas, 11.2 x 15.5 in. Collection: DAG |

In the early 1960s Clement Greenberg, a well-known American art critic, came to Delhi and he met Ambadas. He was very surprised to see his work, because the Europeans and the Americans, even today, think that abstract art was their invention solely. But he could not see any sign of such western influences on Ambadas’ abstract art. So he invited Ambadas to the U. S. A. Ambadas went to New York and stayed there for a while and met many artists there.

He was thus exposed to the Western art world as well as the Indian art world. He would also draw from Indian philosophy, because he was a voracious reader. We would talk about Kabir, he would talk about other philosophers, poets and writers. And when I saw his library in his house in Oslo, I was not surprised, because his wife still has those books. And then in 2012 I had gone with my wife Jyoti to Ambadas’ house because Hege insisted that we must stay with her. So we stayed there for three days. And every day I would look at the books (he collected) and take some out to see what he was reading. There was a range of books on different subjects, especially philosophy, which he was very much interested in. Western and Indian both.

So he was a well-read man, but he did not want to impose his knowledge on his art. He would just let it happen, and that happening shows a lot about his creativity.

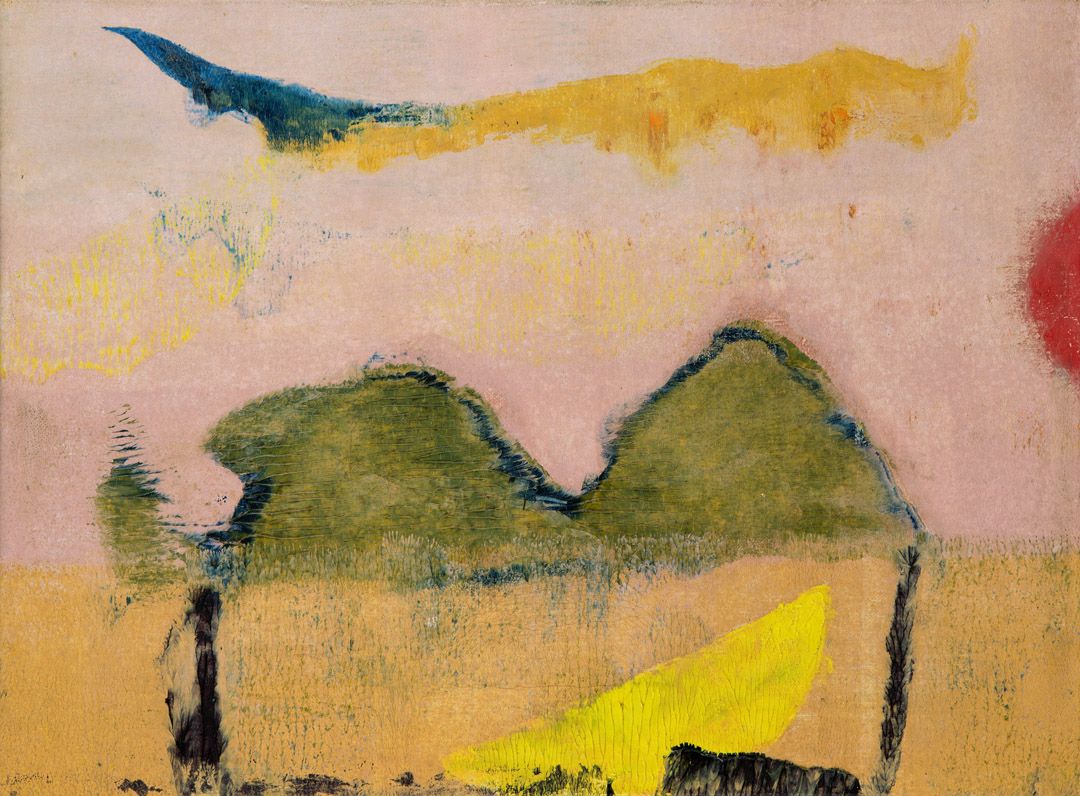

It is not that anyone could take a brush and start painting on the floor, expecting some great work to emerge. When an artist like Ambadas starts working, then one can see that whatever he had inside him was coming out. There was a lot of skill on display too, because Ambadas was a trained artist. He was a student of the J. J. School of Art and was taught by Shankar Palshikar. S. H. Raza, Gaitonde, Prabhakar Kolte and many others were students of Palshikar. Many of our most significant modern artists were students of Palshikar. So his contribution must be recognized. I also have a great respect for him because I have read about him and heard about him, and I've seen his works too. Ambadas would tell me many times that he held him in high regard, even if he had some differences with him, like a student inevitably does with their teacher.

Prabhakar Kolte, Untitled, Acrylic on mount board, 12.0 x 12.0 in., 1986. Collection: DAG

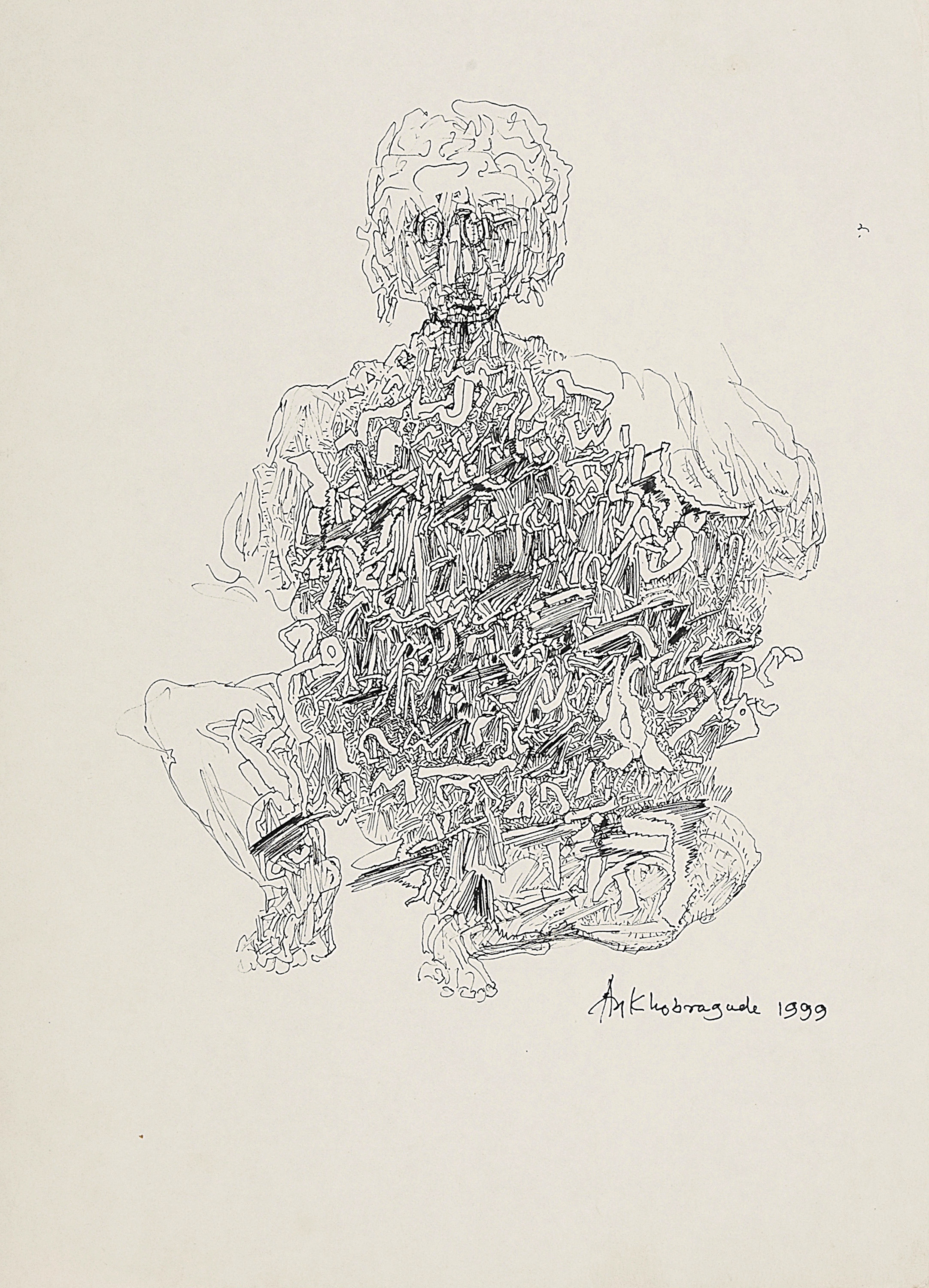

Q. Earlier, you were talking about his drawings where there are some suggestions of figuration, with quasi-animal shapes, etc. Would you want to talk a little bit about his drawing practice and what kind of relationship it had to his paintings? Here I have a quote by him on drawing, where he says, ‘I use the micro tip pen and at other times the felt pen, when I wish to pull some lines or rub my hand over it for a deliberate, smudged effect. For me, drawing is a rather conscious act and is more about building up like in sculpture.’ So how do you see this practice, which he himself compares to the act of sculpting. And how do you think he decides when to finish a drawing or painting?

Prayag: I can't really say with any authority, but what I imagine is that any artist, when they work in a different medium, whether drawing, printmaking or sculpting, are looking to create something other than what they usually do.

Swaminathan's drawings are so different from his usual works, so that no one would believe that it is the same Swaminathan working in ink like this. Swaminathan, who is known as a painter of mountains, birds, and who's influenced by colours, especially Indian colours, and by miniatures, to a certain extent.

|

Ambadas, Untitled, 11.5 X 8.3 in., 1999. Collection: DAG |

But it happens when mediums change and materials change. In the case of Ambadas also that is what happened. But we had some of his drawings in this show recently put up at I. I. C., and the drawings were mostly borrowed from Akhilesh, the painter.

Each and every drawing was done in materials that were different from what Ambadas would probably choose for his painting. The colours were different, the medium was different. And in his painting it never happens that a figure emerges, whereas in these drawings many visitors have noted the presence of figurative forms.

I personally believe that there is no such thing as an abstract painting, or even figurative painting; these are simply categories for our understanding of different forms. Otherwise when there are forms, colours and lines, how can it be abstract?

Once I wrote that during harvest, when the farmer is harvesting and sowing seeds, then, as you know in India they use a plough, hal. The same happens in Ambadas’ paintings, in his strokes the same kind of formations are formed. He's sowing something. He's sowing seeds. So maybe there are many ways of interpretation and that is the beauty of art, because no artwork has just one meaning.

When people ask about the meaning of a work, I always wonder what they want to know, and when they say that there is one meaning, I think to myself why someone would paint, when they could simply write it down and say, ‘I want to say this’. So the meaning entails a search. And I'm not surprised that many critics have written on him, including Richard Bartholomew, Keshav Malik, Santo Datta and Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni. Whenever we write on him, there are, of course, certain things which are common, which is bound to happen, but then you would find that each and every critic has something different to say too.

And not only about Ambadas, but about all these artists.

|

Ambadas, Untitled, Ink on paper, 11.7 X 8.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Finally, how many times did you visit Ambadas, and when was the first time you met him? Was it in India or was it in Norway?

Prayag: I met Ambadas in India for the first time in the mid-1960s at the Indian Coffee House, with common friends like the poet Kamlesh, who was a dear friend to Ambadas. So I started visiting him in Delhi and he also come to our house.

But my first visit to him in Oslo was in 2009 and the second was in 2012 when he was not there anymore, and Hege took us to where he was buried, and there was no stone or plaque as such to mark it. But there were some flowers there. So I told Hege, ‘Please let it be like this, only put the name of Ambadas, or that Ambadas is lying here’. I don't know what has happened after that, but another beautiful thing happened during my visit. When we were living in Ambadas’ house and Hege was taking her car to drop us at the railway station (from where one has to take the train to the airport), suddenly my wife Jyoti said in Hindi, ‘acha Ambadas ji, chalte hain,’ (‘Okay, Ambadas ji, we are going now’) believing that Ambadas was still there. Hege was taking the car out from the parking lot when she heard this, and she could understand it and was very touched. And then I said that yes, for us Ambadas is here and he is sleeping, he's living. Living in my wife’s thoughts and memories. That is how we regard him. We love him and we believe that he’s there.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025