Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

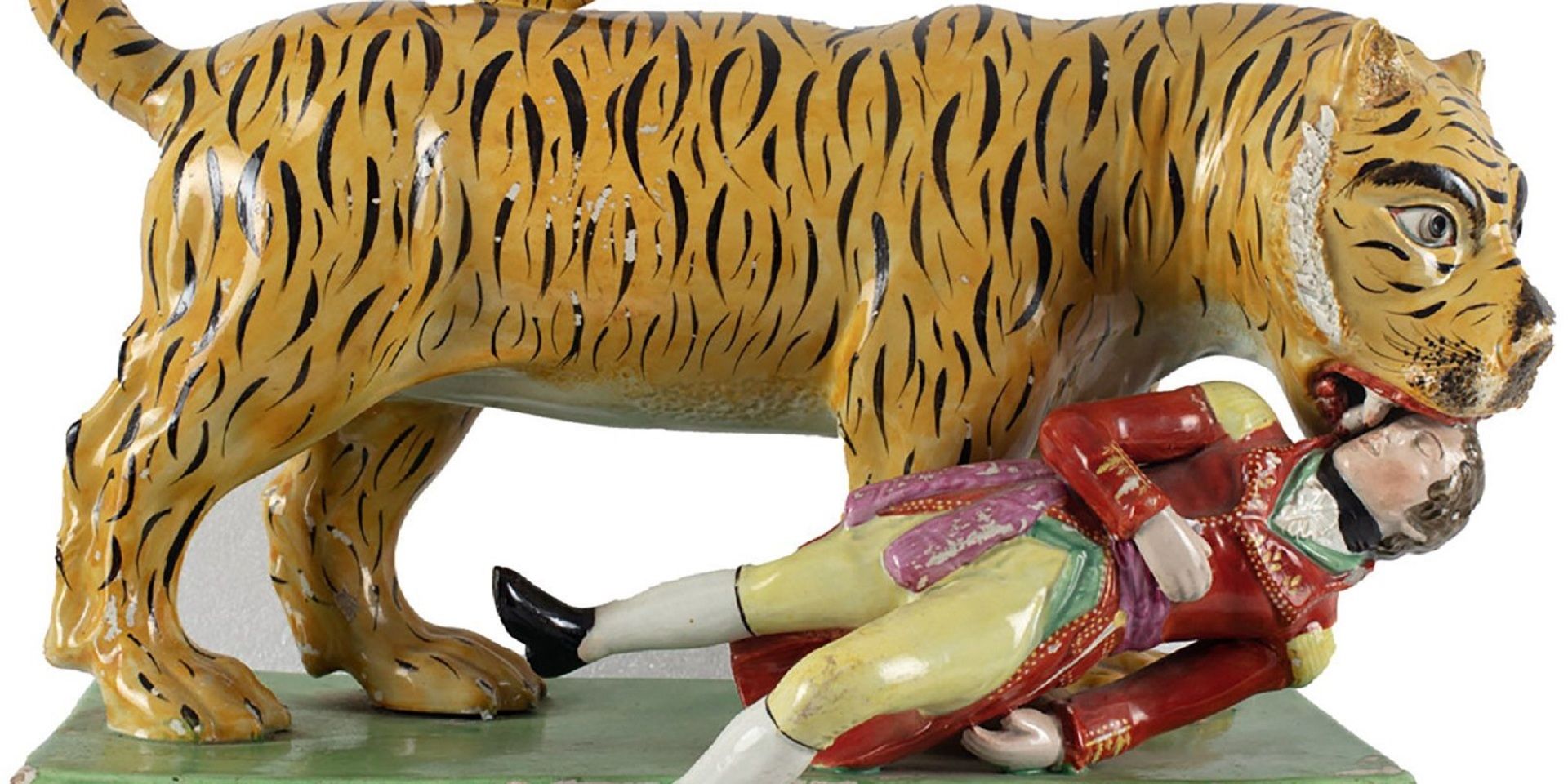

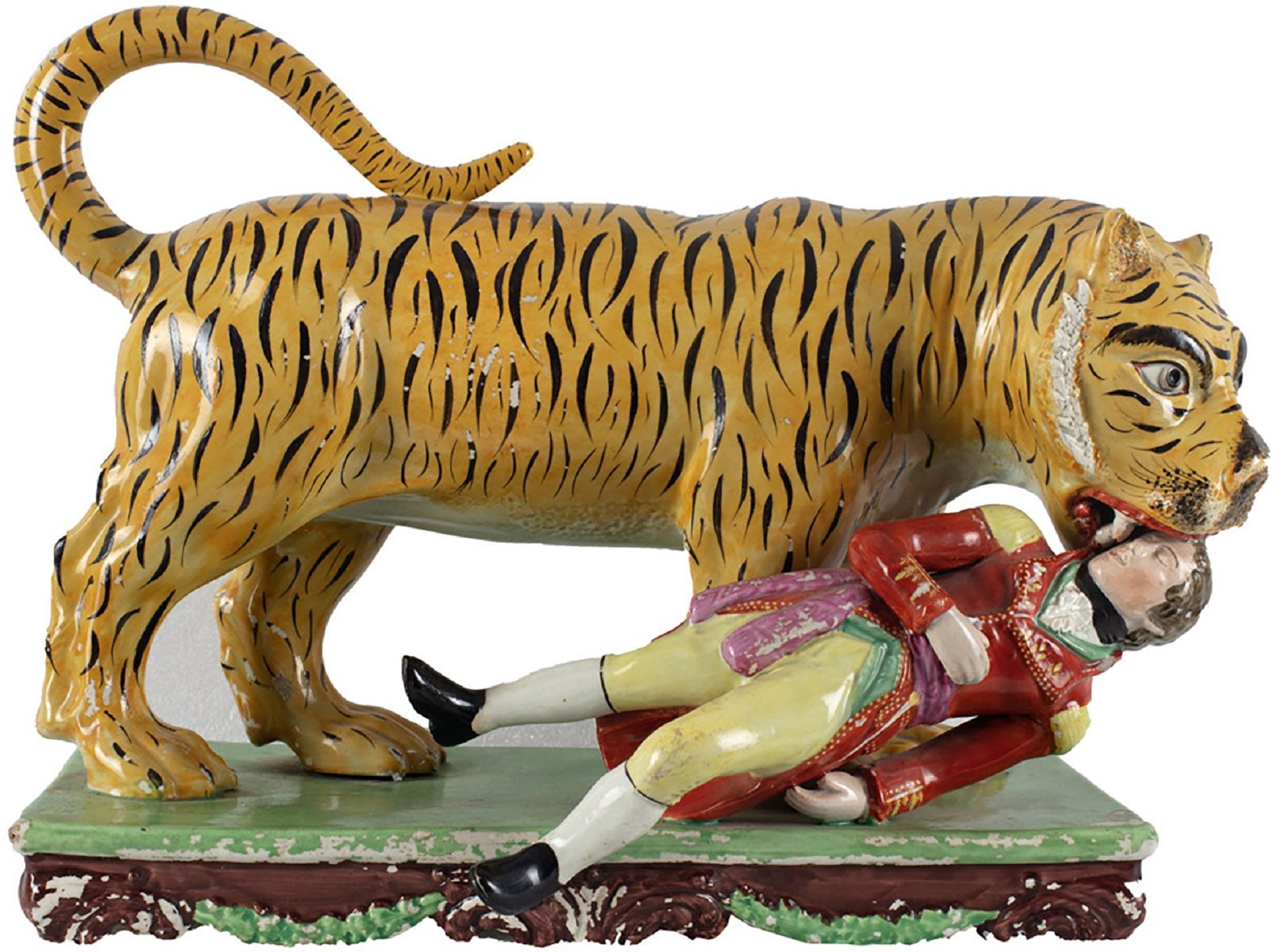

Obadiah Sherratt, The Death of Munrow (detail), c. 1815, Glazed ceramic, 10.0 x 14.0 x 6.2 in. Collection: DAG

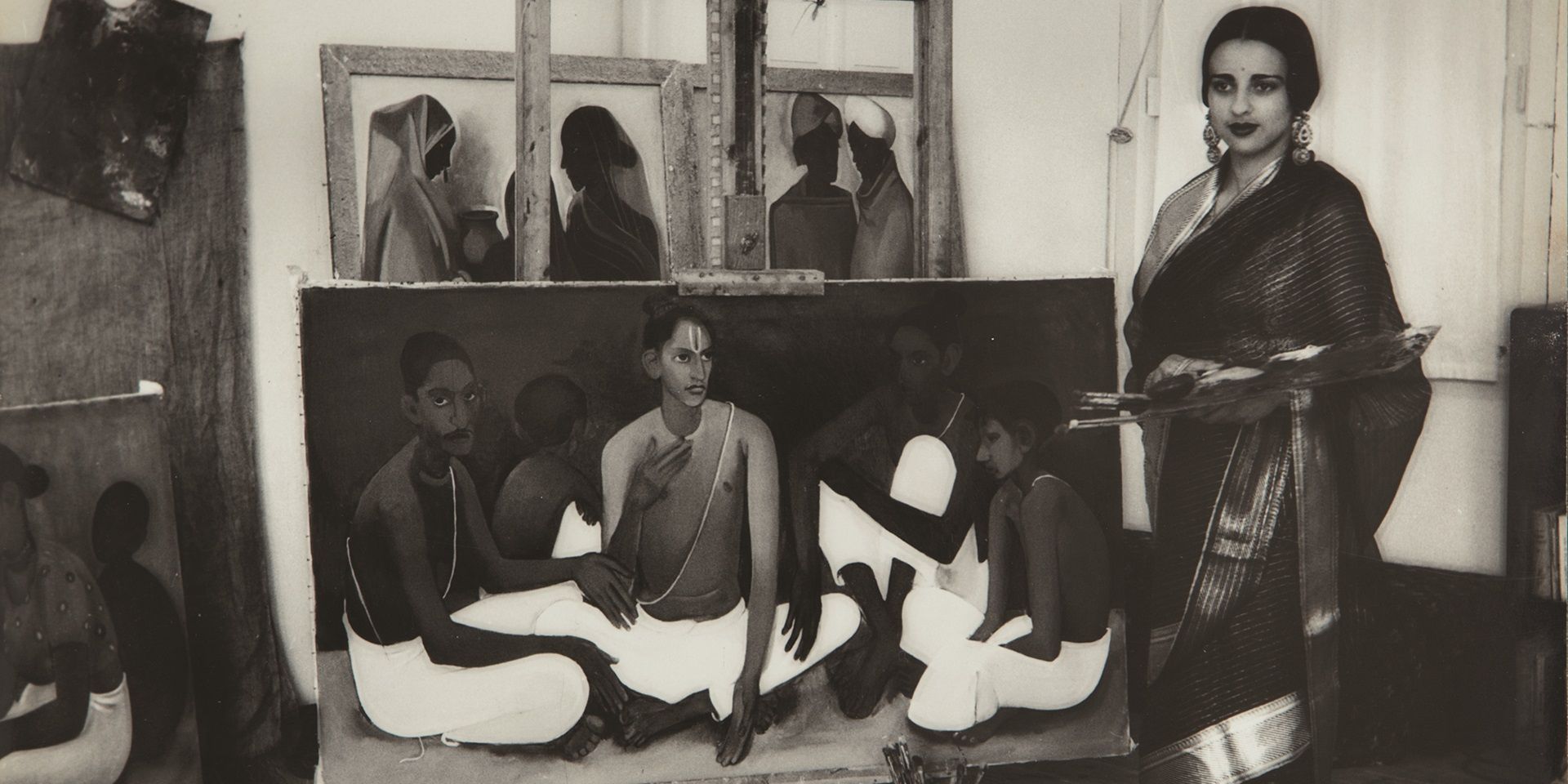

Dr. Sudeshna Guha is a Professor in the Department of History and Archaeology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Shiv Nadar University, Delhi-NCR. Her book, A History of India in 75 Objects, offers a unique exploration of Indian history through carefully selected artefacts.

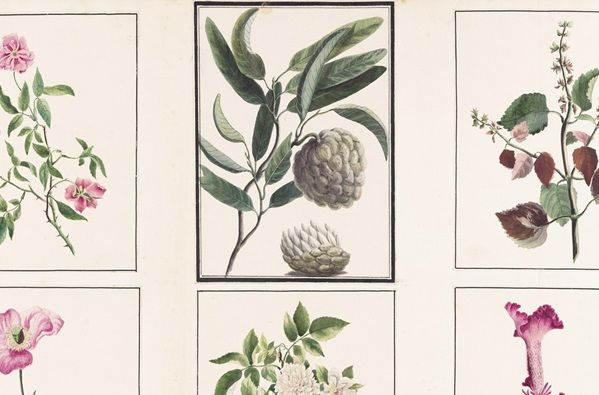

Each object serves as a window into different periods and facets of India's complex cultural and historical tapestry. The book delves into the life histories of these objects, ranging from the ancient to the modern, including prints, monuments, paintings, sculptures like the Yakshi of Didarganj, objects like the trademark Indian car the Ambassador, the E.V.M. Machine, ‘Tipu’s Tiger’, a photograph by Deen Dayal, film posters and many other things; to illuminate key historical events, societal changes, and cultural dynamics across India's diverse regions. Through detailed descriptions and historical context, Dr. Guha showcases how these objects provide insights into the complexities of India's past and its interconnectedness with global history. What follows is an edited version of the interview she gave to the DAG Journal.

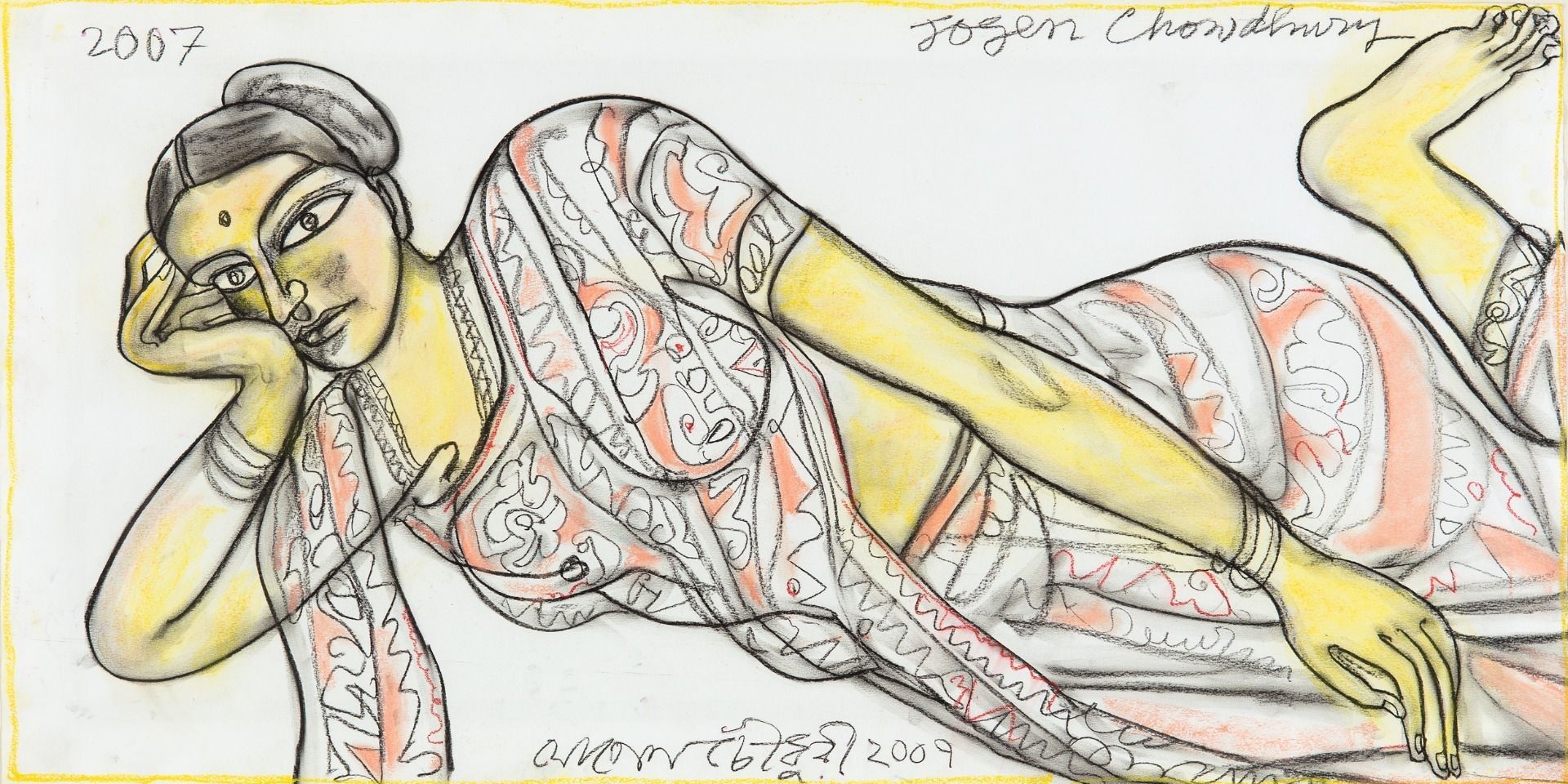

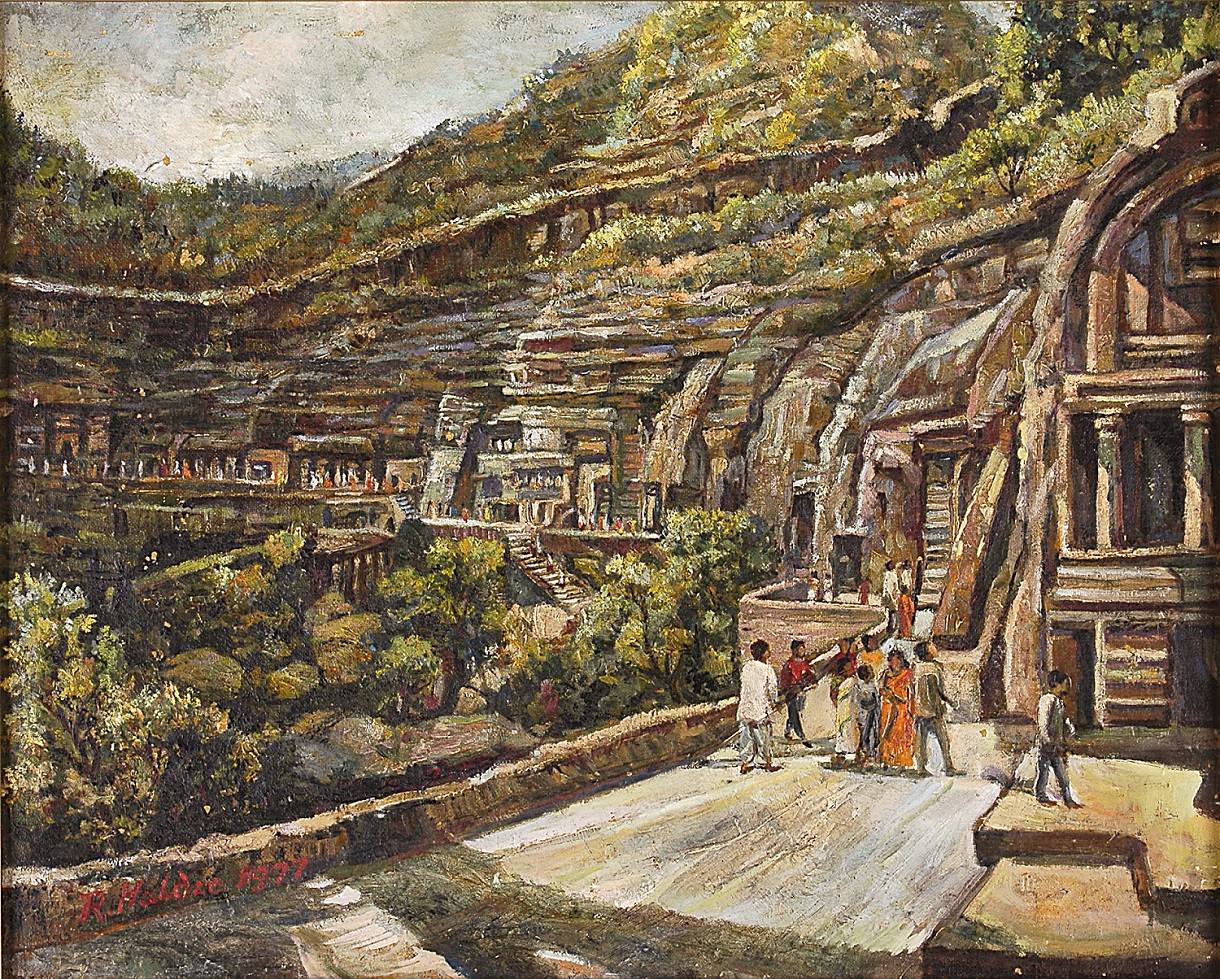

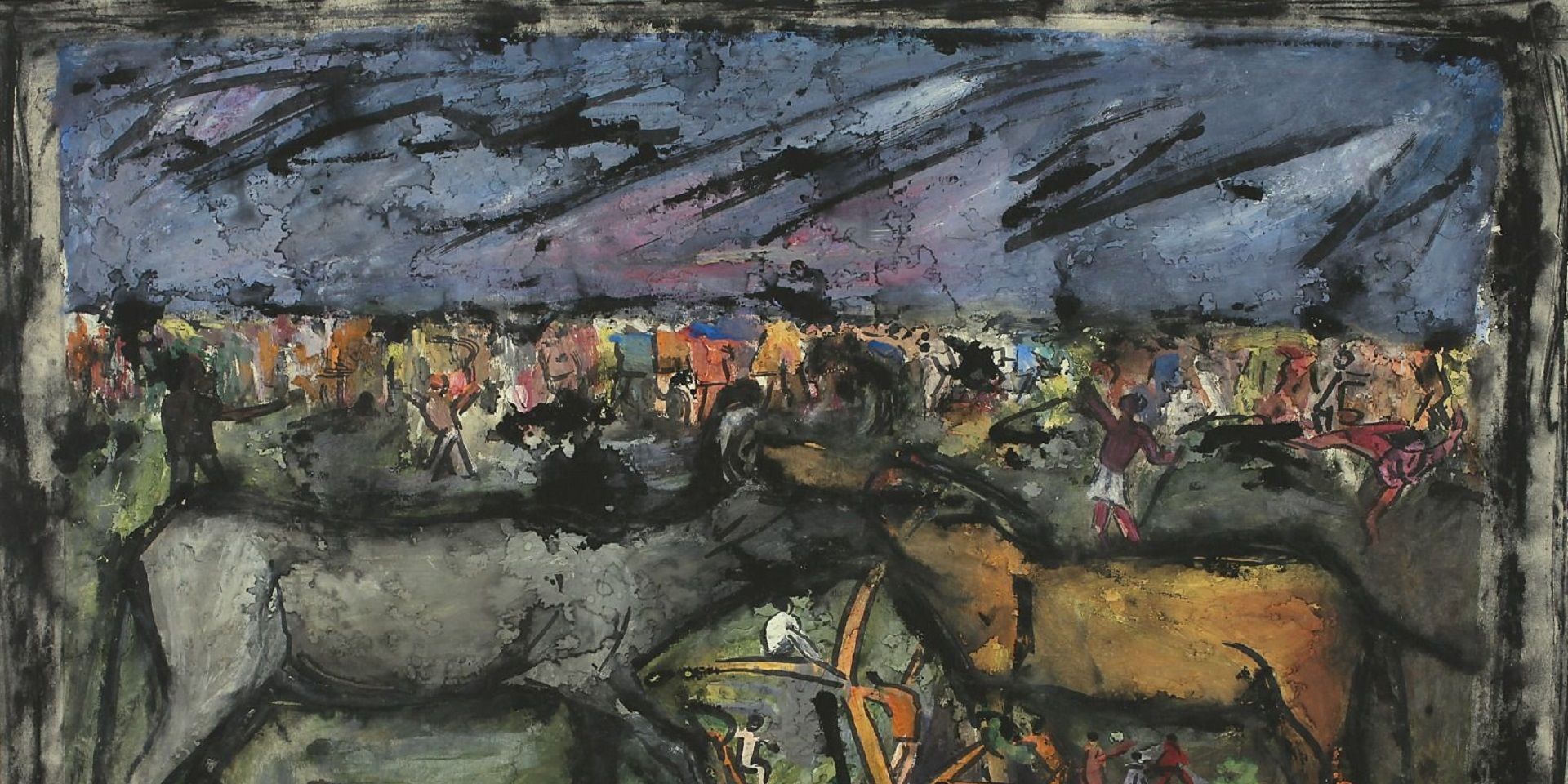

Rabin Halder, Ajanta, 1977, Oil on canvas, 16.0 x 20.0 in. Collection: DAG

Q. What role do museums play in academic research, especially in the field of cultural history, today? Is it a resource that is frequently used or considered a valuable academic archive by academics in your experience?

Sudeshna Guha: Museums have played a crucial role in the development of various disciplines. For instance, disciplines like prehistoric archaeology and social anthropology emerge from museums and their collections. Early field researchers contributed significantly to their disciplines by collecting and organising artefacts, which formed the basis for understanding the world around them. Thus, museums have historically been integral to the formation of academic disciplines.

While the natural sciences have laboratories, museums have served as analogous spaces for the social sciences. Historians, though late to recognise museums as educational institutions, have increasingly acknowledged their importance. Museums excel in activities crucial to disciplinary thinking, such as classification, sorting, and exhibiting. These practices are not mere tasks but fundamental methodologies that shape evidence formation across disciplines.

|

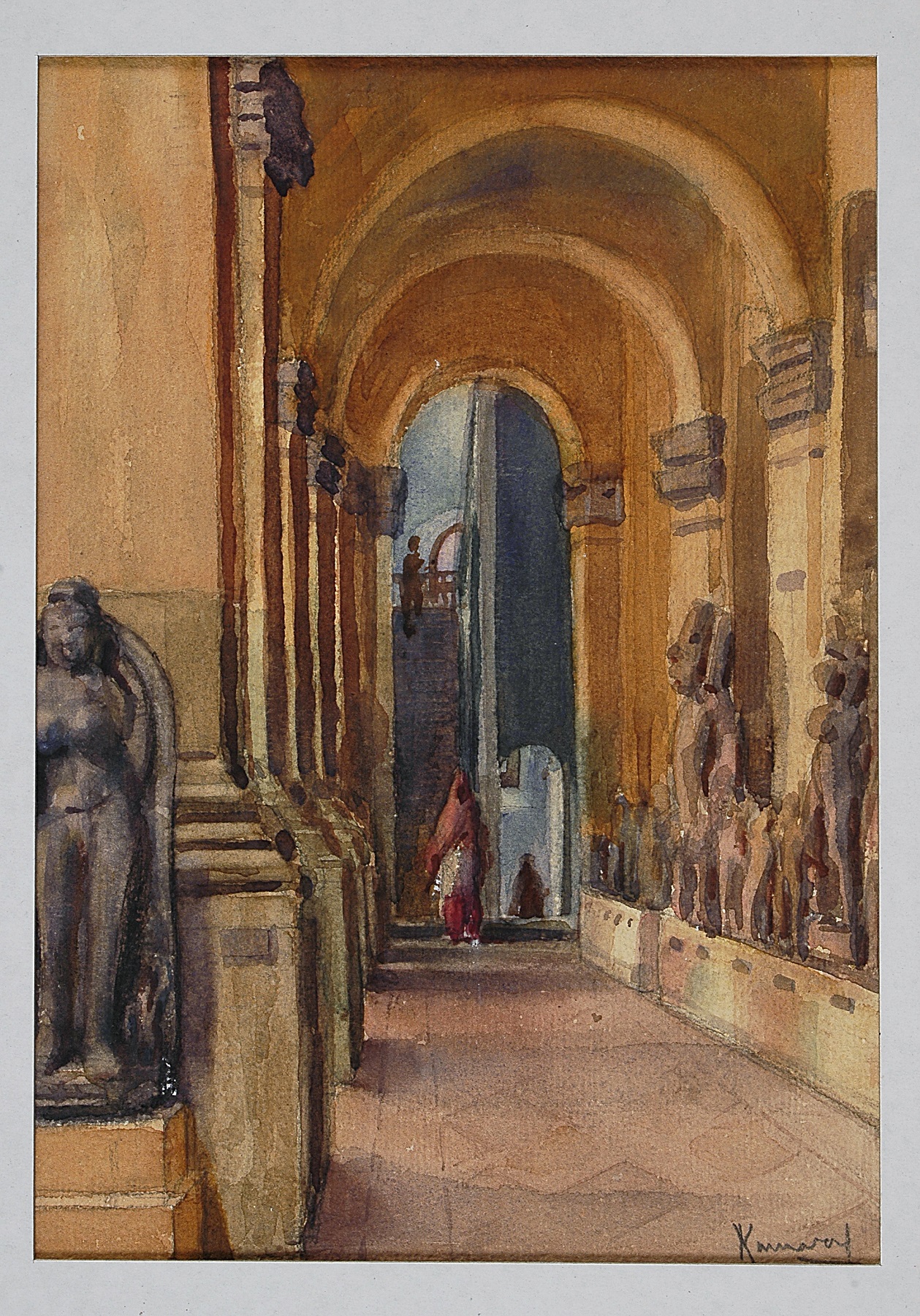

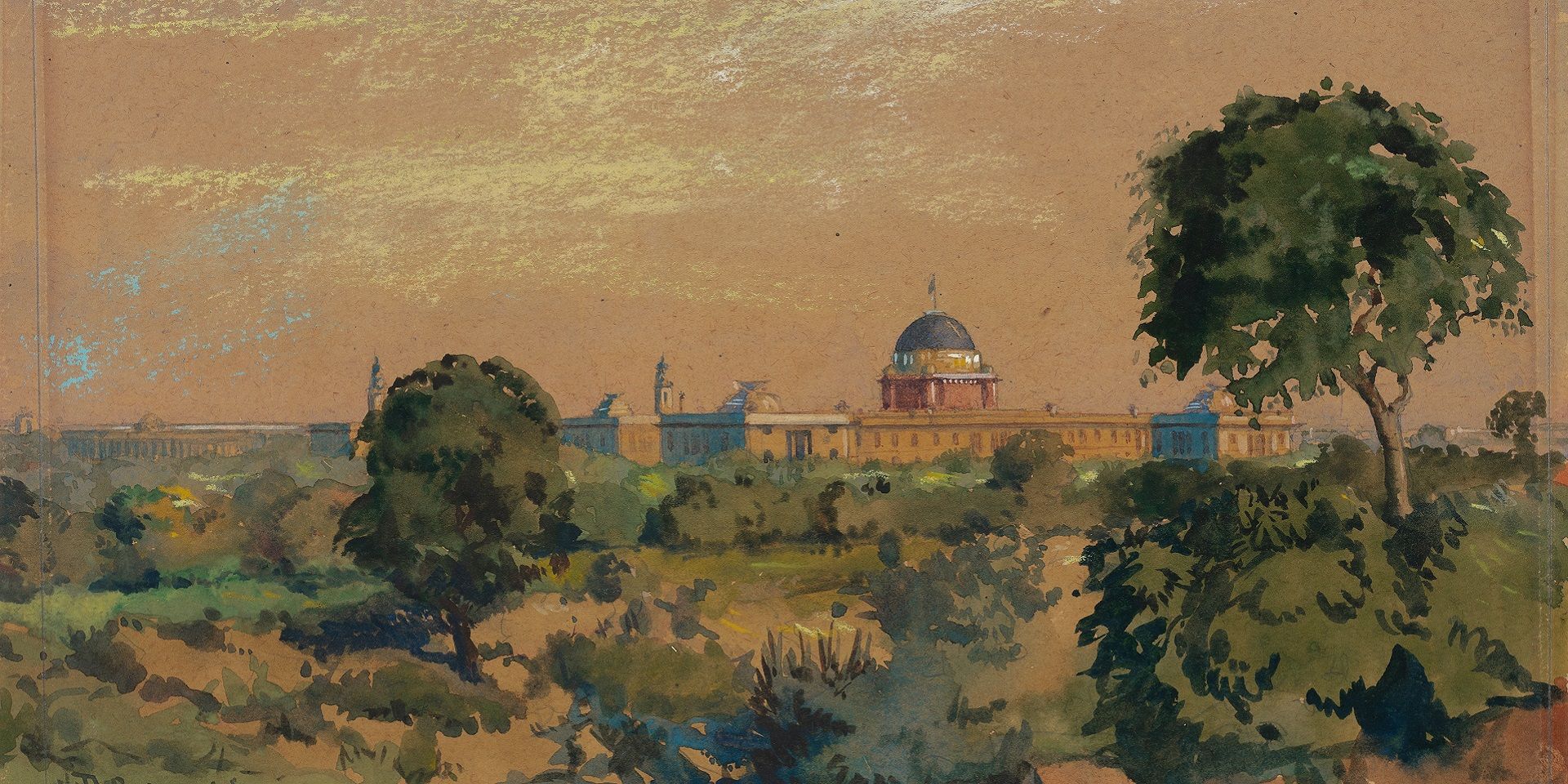

Kanwal Krishna, Calcutta Museum, 1935, Watercolour on paper, 9.5 x 6.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Collections management within museums is particularly valuable. It encompasses histories of collecting practices, the meticulous process of selecting, categorising, and preserving artefacts. This process extends beyond preserving heritage or culture; it is foundational to methodological frameworks. Museums provide vital insights into how these methods evolve, are applied, and can be critically examined.

Moreover, the history of museums themselves reveals insights into broader societal changes. The proliferation of museums today reflects contemporary needs and priorities, including issues of heritage preservation and cultural diplomacy. Museums offer perspectives on colonial histories and regional identities. For instance, the establishment of state museums in India parallels state formation, reflecting local histories and aspirations. Museums also contribute to political discourse and educational outreach. By examining museums' roles in collections management and their impact on societal narratives, we gain a deeper understanding of how nations construct and interrogate their identities through material culture.

Q. In your chapter on copies of the frescoes at Ajanta–you remark on the value of photographic reproductions and models of the Ajanta caves that can give us a detailed view of these murals and artworks. But besides the purpose of simply documenting these works, copies of the Ajanta murals fed into academic art school coursework and went on to rejuvenate figurative aspects of modern Indian art as artists from Bombay, Calcutta and beyond made it a part of their academic ritual to visit and copy these frescoes. You also write how ‘all the early paintings of the murals are now valued as antiquities that promise new enquiries into the collecting, archiving, and displays of Ajanta in the modern world.’ Even visiting Japanese-Buddhist artists would copy these for their work. What wider role do you think these copies play in visualising Ajanta?

Sudeshna: The distinction between 'copies' and 'originals' has long been central to traditional art history and archaeology. Archeologists identify 'fakes' and authenticate the original. Interestingly, they seldom question the distinction themselves.

|

M. V. Dhurandhar, Ajanta, Ink on paper, 7.5 X 5.5 in. Collection: DAG |

In archaeological circles, a fake is often labelled a 'hoax'. During our days as students of archaeology, we would playfully place modern artifacts in excavation sites to see if others could tell their true age. While fakes and copies are frequently discussed, their role in expanding access to the originals is notable. Consider the Ajanta caves as an example: many have seen copies of the paintings without visiting the site itself. Much scholarship on classical Indian art relies on studies of copies rather than direct observations of the originals, which raises important questions about how copies contribute to our understanding of histories of art.

Today, visiting the original site of the Ajanta Caves presents challenges due to (ongoing) conservation efforts. Having worked in Ajanta Cave number 17 during my student days, I discovered that sometimes copies offer a clearer view of the original. They have aided in visualising the paintings within the Ajanta Caves. The term ‘Ajanta’ is colloquially used for the caves, though the village of Ajintha (also known as Ajanta or Ajantha today) is not where they are located—it’s a few kilometers away. The original name of these caves remains unknown, as does the identity of their creators.

Lala Deen Dayal, Ajanta caves, c. 1888, Silver albumen print on paper, 7.7 X 10.5 in. Collection: DAG

The circulation of copies has advertised the existence of these cultural artefacts beyond their original locations. This process not only involves their creation but also their dissemination. The selective copying of certain artefacts over others reflects historical choices in what is remembered and recalled. A notable example are the two copies of the Eastern Torana (gateway) of Sanchi, which is exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The original plaster cast by Henry Hardy Cole was made in 1871; subsequently, multiple copies were made, and the Berlin copy is one of them, which is now exhibited at the Asian Arts Museum in the Humboldt Forum. A stone copy of the Torana made from this plaster cast is prominently placed within the outer precincts of the Humboldt Forum, as a secular architectural piece; a bridge between the East and West. Strikingly, the label of the nineteenth century plaster cast of the Easter Torana in the Asian Art Museum does not acknowledge its identity as a copy. It omits to mention this as a plaster cast.

Sanchi Gateway, of stone copied from the nineteenth century plaster cast, at Humboldt Forum. Photographer: Sudeshna Guha

Copies gain meaning when infused with their historical narratives, such as those seen in replicas of the Ajanta paintings or souvenirs imbued with a sense of the past. These copies bridge the past and present, offering nuanced insights into cultural heritage and its interpretations. I believe that the distinction between copies and originals takes away the rich histories of the copies, which encapsulate diverse narratives of their own creation. Copies are examples of ongoing histories. My appreciation for them deepened through my work with photograph collections, especially of the archaeological. In archaeology, duplicate prints are usually discarded and the original 'preserved'. However, each photograph of a parent negative would be seen differently if it was exhibited or shown differently.

Lala Deen Dayal, Sanchi Stupa, Silver albumen print mounted on card, c. 1880, Print size: 8.2 x 10.5 in. Collection: DAG

For instance, a childhood photograph of myself holds personal value within my family. Yet, the same photograph displayed in an international exhibition on the 'races of India' would acquire a different meaning, and when placed in a textile museum, may be used for exhibiting historical attire. Photographs, particularly those of people, carry powerful narratives of race and ethnicity formation. Their interpretation varies across different contexts and uses, influencing how they are perceived and valued. I owe my understanding of their significance to scholars like Christopher Pinney and Elizabeth Edwards, visual anthropologists whose work with photographs has profoundly influenced me as an archaeologist. Historians, in contrast, often overlook this aspect. While some delve into an object's life history, the true value lies in recognising that objects continue to accumulate layers of meaning over time.

|

Plaster cast of the Eastern Torana, late nineteenth century. Asian Arts Museum, Berlin, Humboldt forum. Image courtesy: Sudeshna Guha |

Q. There are some objects discussed in your book that are still-standing iconic monuments or structures in India today. One of the most intriguing ones is the number of Jantar Mantar complexes—especially the ones in Delhi and Jaipur, that also make a striking visual impact. How do these structures offer us a chance to ‘correct’ some prevalent ideas about their supposed antiquity, and include an account of the wide-ranging global influences that shaped them? And what do they say about how British colonial officers saw the impact of Indian or ‘Hindu’ Science?

Sudeshna: These Jantar Mantars have been extensively studied. One notable study by Simon Schaffer frames them within the context of the Asiatic enlightenment and challenges the simplistic narrative of a singular European enlightenment.

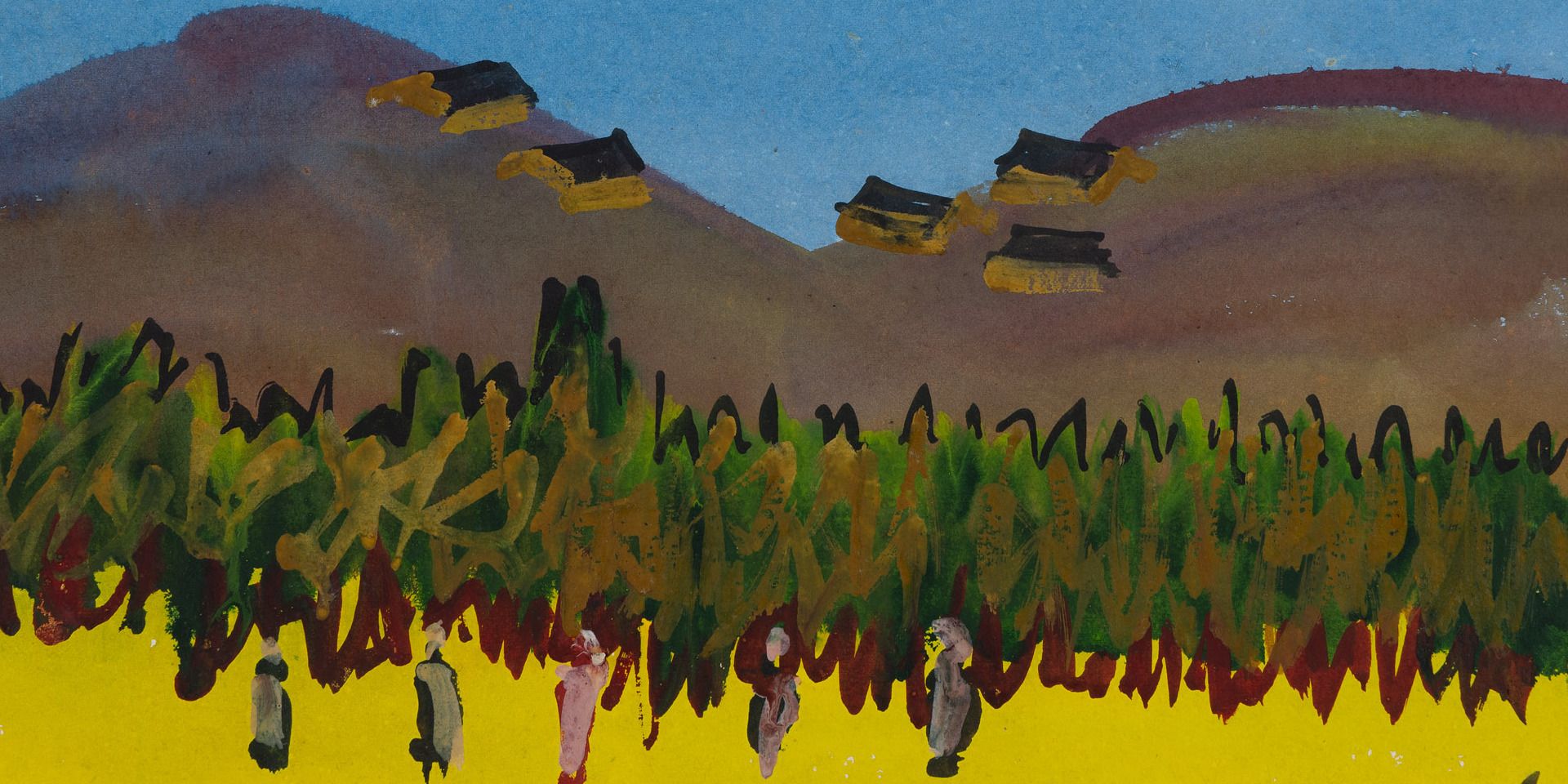

Thomas and William Daniell, Jai Singh's observatory, Delhi, 1790, Watercolour and graphite on paper pasted on paper, 20.5 x 44.0 in. Collection: DAG

The colonial narrative, while often reiterated, has become somewhat clichéd, especially given India's independence over seventy-five years ago. What's more intriguing is the role these monumental astronomical instruments of stone played in the advancement of science within networks facilitated by colonialism and the East India Company in the early eighteenth century. The essay in my book focuses on the Jantar Mantar in Jaipur. Standing next to the Hawa Mahal, it remains a visible testament to its builders' astronomical prowess. The Jantar Mantars encapsulate diverse histories. They show Jai Singh’s knowledge of astronomy, his homage to his patron, the Mughal ruler, Mohammad Shah and the contributions of the Portuguese, French, and British scholars whom he courted for the building of these instruments. Catherine Asher's insights on Jai Singh’s visions of his capital, Jaipur, further enriches this narrative. These histories highlight the inter-connectedness of knowledge production across cultures, challenge simplistic classifications of the indigenous and foreign, and emphasise the dynamic nature of intellectual traditions.

The Jantar Mantars provoke us to consider how we classify and interpret. They also remind us that the politics of knowledge in our world today is complex and urge us to interrogate our assumptions and embrace the diversity of human intellectual achievements.

|

Unidentified Photographer, Kuwat-Ul-Islam Delhi (Quwwat-Ul-Islam and Iron Pillar), Silver gelatin print on paper mounted on card, 8.3 x 11.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Writing about another fascinating, if rather sensationalist, object, ‘Tipu’s Tiger’, you discuss the role political anxieties can play in rooting prejudice and shaping the facts of history. How did the object play into stereotypical fears of ‘oriental despotism’ and what are some of the ways in which objects like these can be re-assessed or exhibited in our time when some of those fears and anxieties have been transferred onto a different environment? DAG’s own exhibition on Tipu Sultan, for instance, carried similar models of tigers–suggesting their widespread prevalence as toys at the time, as you suggest. How can the over-inscribed colonial narrative be scrubbed clean–and is that even desirable now?

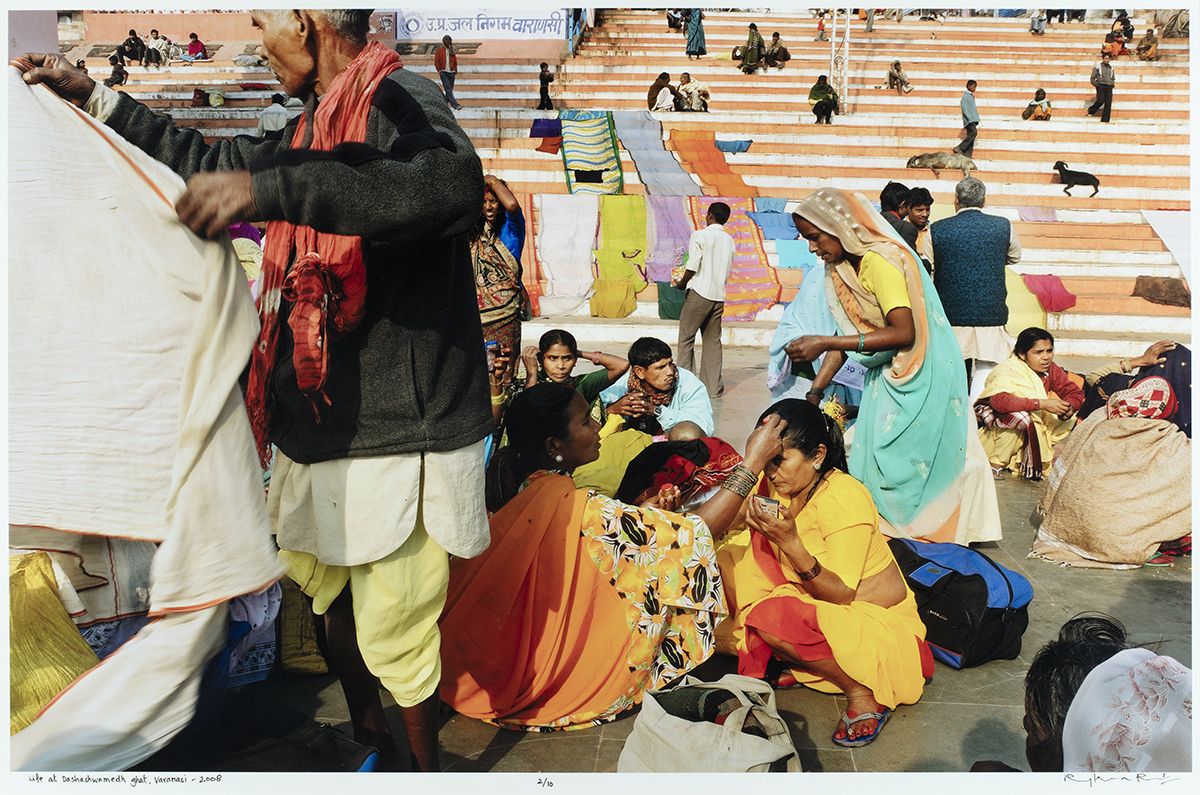

Sudeshna: ‘Tipu's Tiger’ resides in the V & A (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). It’s a well-known artefact with a lesser-known story in India. The tiger was looted—it is a wooden effigy that survived because it lacked the valuable stones and jewels that were melted down.

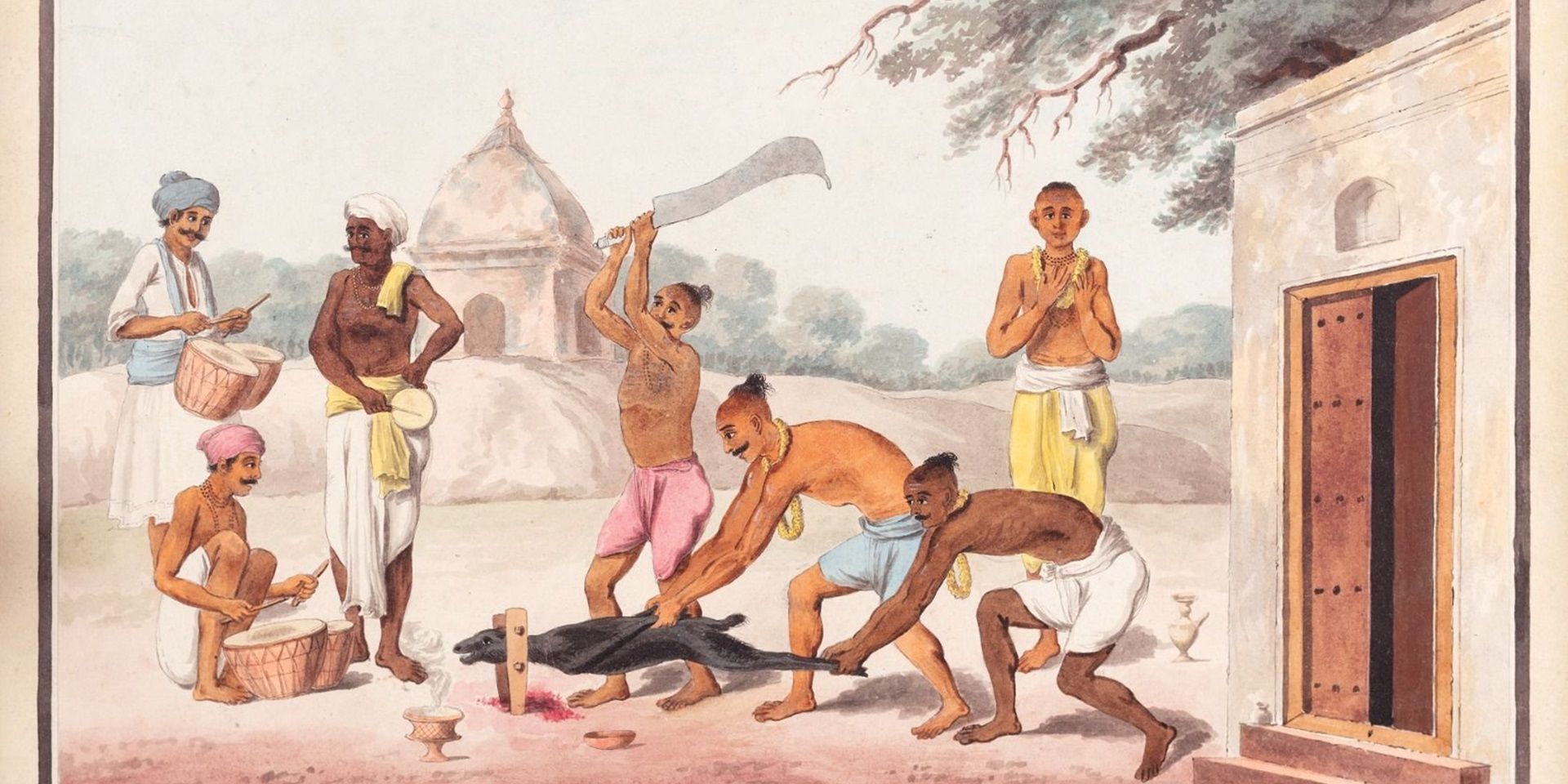

Obadiah Sherratt, The Death of Munrow, c. 1815, Glazed ceramic, 10.0 x 14.0 x 6.2 in. Collection: DAG

Tipu Sultan, then a powerful ruler in South India, fell to the British. This event marked a significant moment in British colonial history in India. The narrative around Tipu’s defeat became an important aspect of the British histories of India. Yet, despite the prominence of the narratives, much remains unknown about Tipu’s fall.

The V & A presents ‘Tipu's Tiger’ with a critical perspective on colonial history. In India, however, Tipu's legacy is often recalled along religious lines, despite the prodigious scholarship of his rule and ‘Tipu’s Tiger' by historians like Kate Brittlebank, Sadiya Qureshi, and Susan Strong. While exhibitions in the U. K. often critically examine colonial histories, exhibitions in India often perpetuate the ‘us vs. them’ dichotomies—a point underscored by DAG's insightful exhibition on Tipu Sultan (Tipu Sultan: Image and Distance).

Until we address the complexities of history, efforts of decolonisation risk perpetuating some of the colonial perspectives.

|

Anonymous, Crouching Tiger, c. 1800, Painted wood, 11.0 x 29.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. Gaganendranath Tagore’s cartoon of Jatashur has also been considered as a unique view into the anti-caste politics of many Bengal artists. Considering the many controversies caricatural depictions have fostered in the caste-bound imagination of Indian society, how can images like these offer a potential for subversion today?

Sudeshna: There's a significant genre of political cartoons that constitute a literary genre of the ‘visual-verbal’, and my book considers three of them: Jatashur, Munnu and Bhimayana. These works have evolved beyond mere political commentary to become important literary genres in their own right. A prime example is Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, which captivated readers globally and marked the emergence of a broader collection of political cartoons. These works serve as powerful commentaries on contemporary issues; Gaganendranath Tagore's album of caricature, Adbhut Lok (The Absurd Realm), in which the Jatashur appears, critically examines the fabric of Bengal society during the early twentieth century, making it a notable example of this tradition.

Jatashur, Munnu and Bhimayana are objects in their own right, embodying the power of visual storytelling and social critique. And then you start asking questions like: who reads these works today? What impact do they have once people have read them? How are they utilised in contemporary contexts?

These questions open up new and important historical enquiries. It's easy to discuss power and agency superficially, but it would be valuable to understand their actual effects, especially among young readers who increasingly read such books. This genre holds considerable influence, with Jatashur standing as an early pioneer. Visual literature like these offer insights into historical contexts, enabling us to connect local narratives with global movements, rebellions, and protests. They challenge and contribute to the ongoing discourse on nationalist histories, reflecting broader transnational themes and interrogations of societal norms prevalent during their times.

|

Gaganendranath Tagore, Confusion of Ideas, Lithograph on paper. Collection: DAG |

In countries like India, where access to education and books remains limited for many, these visual forms transcend literacy barriers. Whether on walls or through graffiti, they open doors to broader political dialogues rooted in visual histories.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

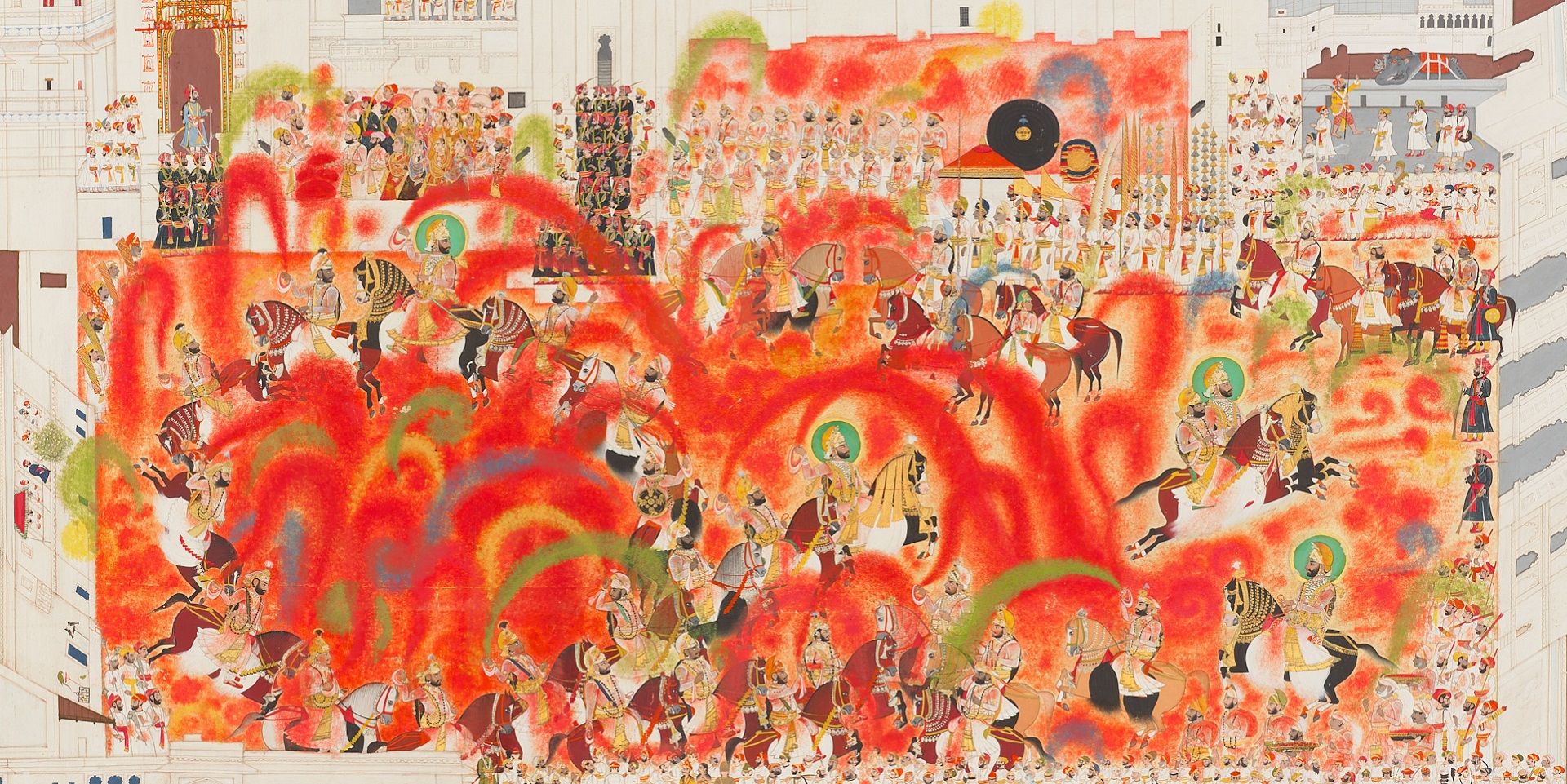

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

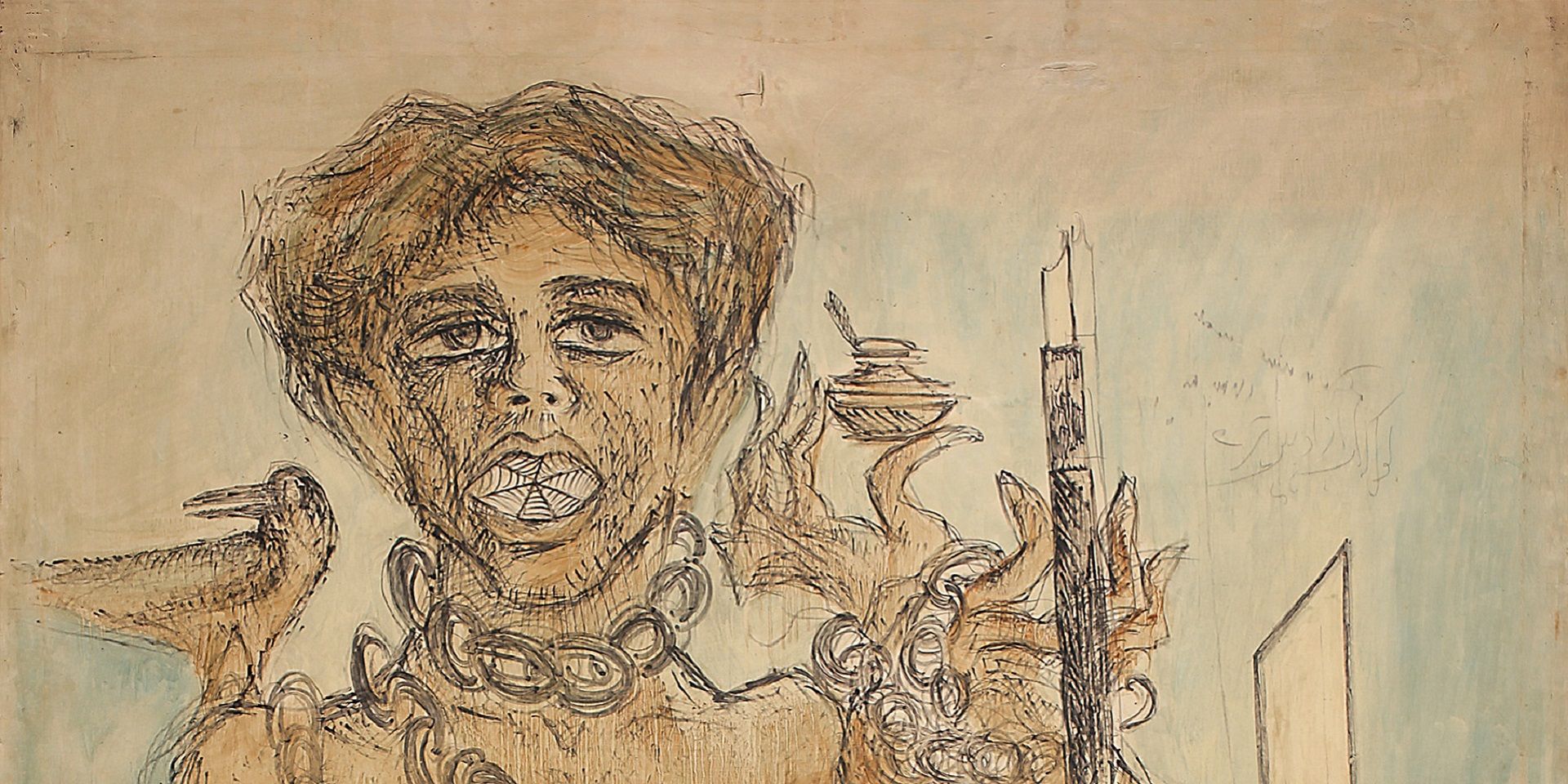

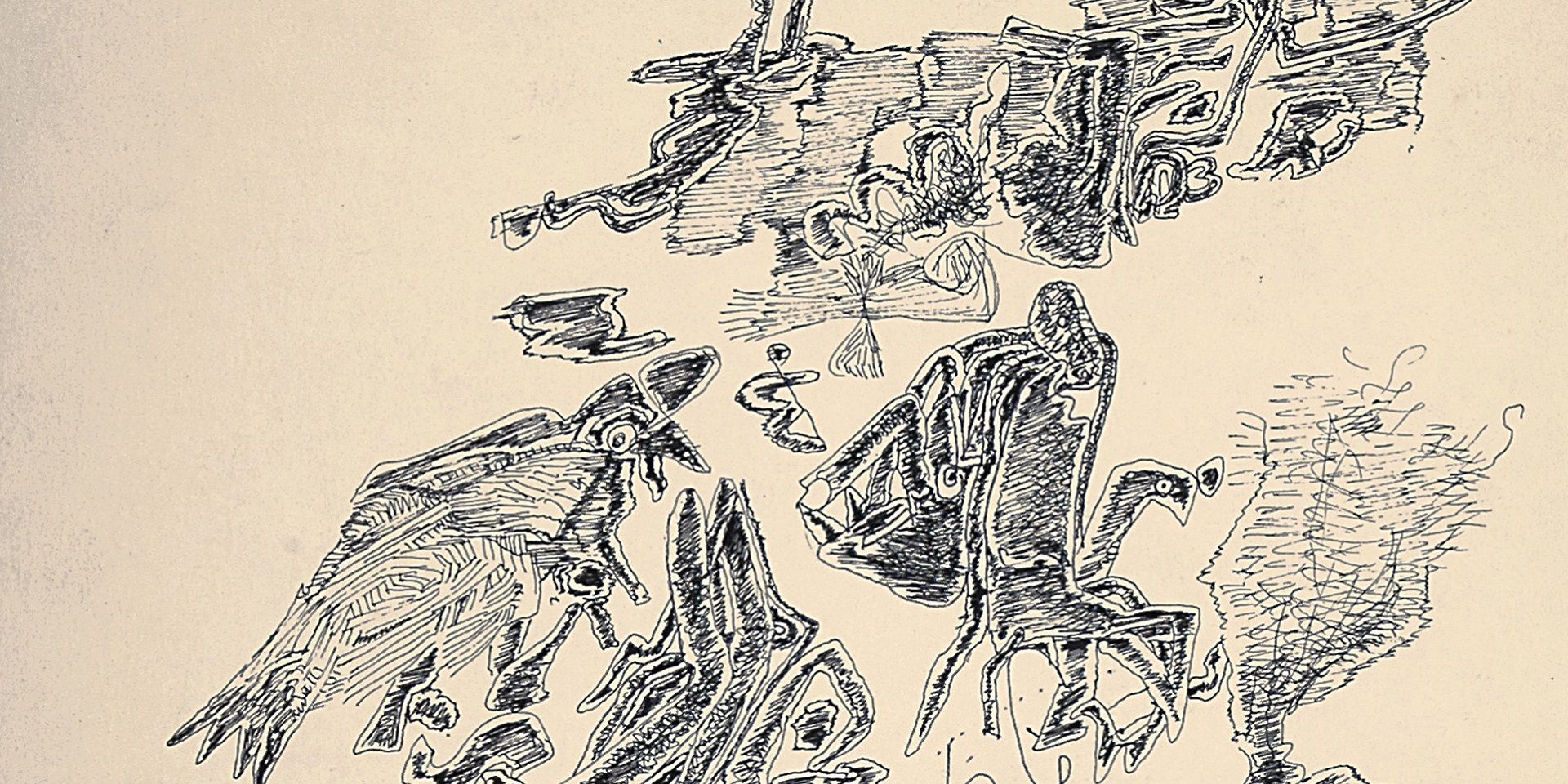

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

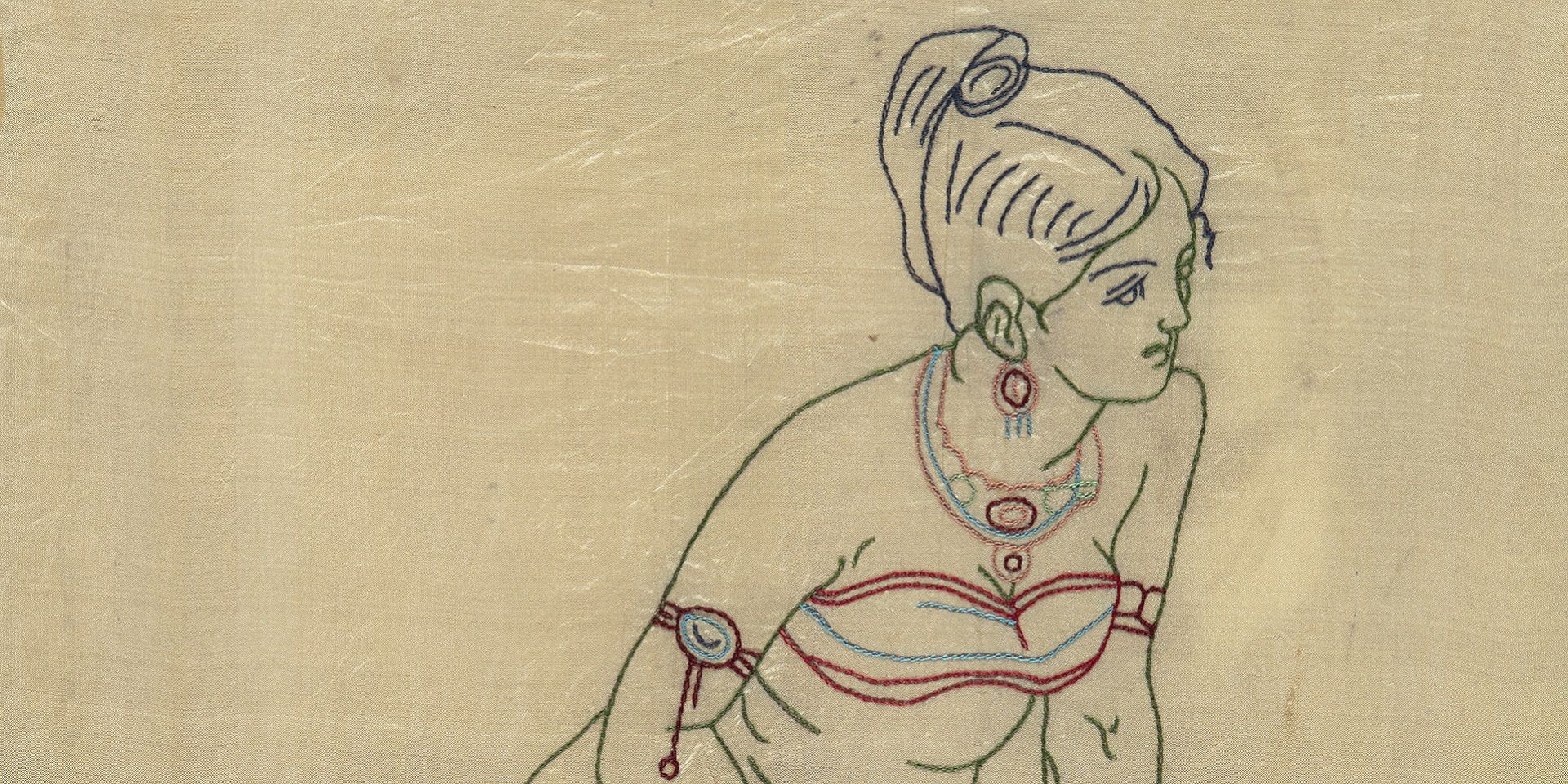

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025