Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

Detail from the caves of Bhimbetka. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Have you ever wondered about the names of lost artists from the past? Who painted the caves at Bhimbetka? How were the intricate rock-cut caves of Ajanta and Ellora constructed, painted and had their interiors decorated with some of the most significant works of art in our cultural heritage? What did the Buddha look like? What is the mystery of the unique pigment called Indian Yellow? Were there any women artists in the Mughal ateliers? How do art heists take place—and what does it have to do with our knowledge of the various histories of art?

|

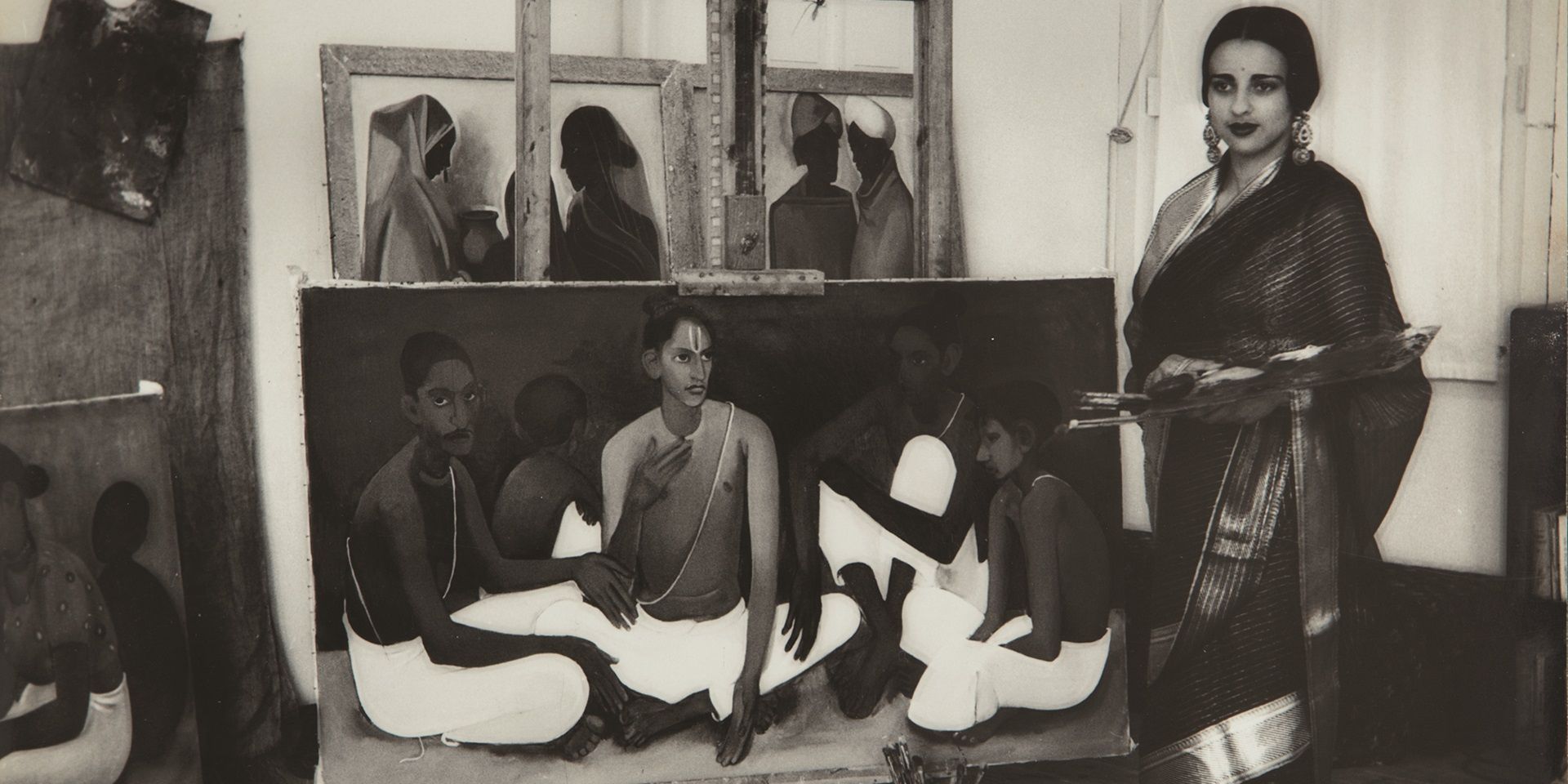

Mamta Nainy, author of 10 Indian Art Mysteries That Have Never Been Solved |

Mamta Nainy’s 10 Indian Art Mysteries That Have Never Been Solved is a children’s book on art history. And uniquely enough, it tries to approach the vast and rich history of Indian art through the lens of curiosity, instead of certainty. Weaving into her text the various loose threads of unanswerable questions from the past, the book seeks to encourage children to seek their own methods for finding the answers to the questions posed in the book. Grounded in historical research, often citing primary or secondary sources from scholarly work, the book maintains a sprightly approach to some of the oldest questions in Indian art. Each chapter leaves readers with new questions and activities to perform, making the knowledge of art history an embodied practice too. She spoke to DAG, discussing the book and the ways in which our complex art history—produced as much by rational historiography as fevered mythical imaginations—can be made accessible to children today.

Why did you choose the format of unsolved mysteries to explore these 10 topics in art history?

Mamta: In my imagination, all great works of art are like time machines. They condense memories and moments, ideas and inspirations, scenes and sequences, and preserve them. And just how it takes time to create a work of art, it also takes time—and a fair bit of reflection—to ‘read’ it; to tease out its purpose, meaning and context from the sometimes-knottier strands of human history. This, to me, is immensely exciting. So, when I decided to write a book on Indian art history for children, I wanted the narrative to lead young readers to engage with art not just with appreciation but also with enquiry—to think about a work of art beyond its appearance, bringing to light its hidden history, its cultural context and even its evolving condition. The format of presenting stories from Indian art history as unsolved mysteries, I felt, could give me that scope and opportunity to draw upon the readers’ curiosity and egg them on to play detectives, follow the trail of clues and come to their own conclusions. I started putting these stories together which, over the course of time, shape-shifted, assumed new forms and then came together as this book.

|

Gandharan Buddha statue. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Sripuranthan Natarajan Idol. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

How did you arrive at this list?

Mamta: With great difficulty! To choose just ten stories from the wealth of stories in Indian art was a daunting task. But I believe art history is not about dusty dates, arcane concepts or obscure schools and movements—it is the visual side of history which can be extremely exciting to explore. And so, the attempt was to include stories that capture this excitement. I started with bits of interesting mysteries I wanted to use in the book and a master list of the major artistic epochs I wanted to cover. The chapters—each starting with an intriguing question—were then developed around these. I was clear that I wanted to include stories that range timelines, and locations, with just enough information about each to give a reader unfamiliar with the work and/or its history a starting point for the revelations to come.

|

Detail from a painting in the Ajanta Caves. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Many of the stories involve recovering missing voices in art history that have nonetheless left intriguing traces, through asking questions about their absence. How did you balance your narratives between the lack of verifiable information and creating enough curiosity through a careful presentation of the missing pieces?

Mamta: I think history can never be the whole picture—it is always from the point of view of the person writing it. It is mediated by those who record history and there are chances that they might have overlooked (or have skewed views of) certain groups or individuals due to their gender, ethnicity, or social standing. Having said that, history is also a discipline and a true historian needs to overcome subjectivities to interpret history in the correct perspective; to identify pertinent sources and evaluate evidence to arrive at a largely objective picture of the past.

A historian has an obligation to get things right about the past but even so, history is an interpretation, an expression, not a definitive truth at all—and, through the stories in the book, I want to draw the attention of young readers to the possibility of multiple histories rather than a single revelatory sort of history.

|

Kailasnath Temple at Ellora, Aurangabad. Wikimedia Commons |

The real thrust of the book is on observation, reflection and discovery, so I approached the narrative with that one thing that’s implicit to the word ‘history’ – the old-fashioned ‘curiosity’. Since the stories in the book travel across timelines, many of the sources, especially in the case of ancient art history, were unreliable. But I found that the key to tackle the issue at hand was to present it as is and to explore that very fertile ground between what these different sources claim and the reasons why they might be making this claim. Many books for younger readers skip the citation of sources but I wanted to be true to my best understanding and therefore, included footnotes and attributions based on my primary sources such as inscriptions, official records, archives, oral histories, manuscripts, paintings, etc. The idea was to not manipulate readers’ responses but leave it to them to decide and come up with their own conclusions.

|

Pithora Wall painting at the Crafts Museum, New Delhi. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

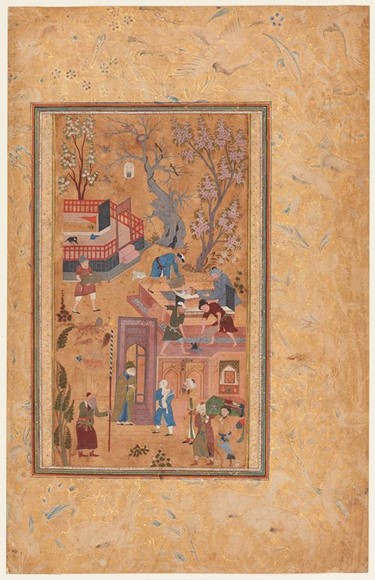

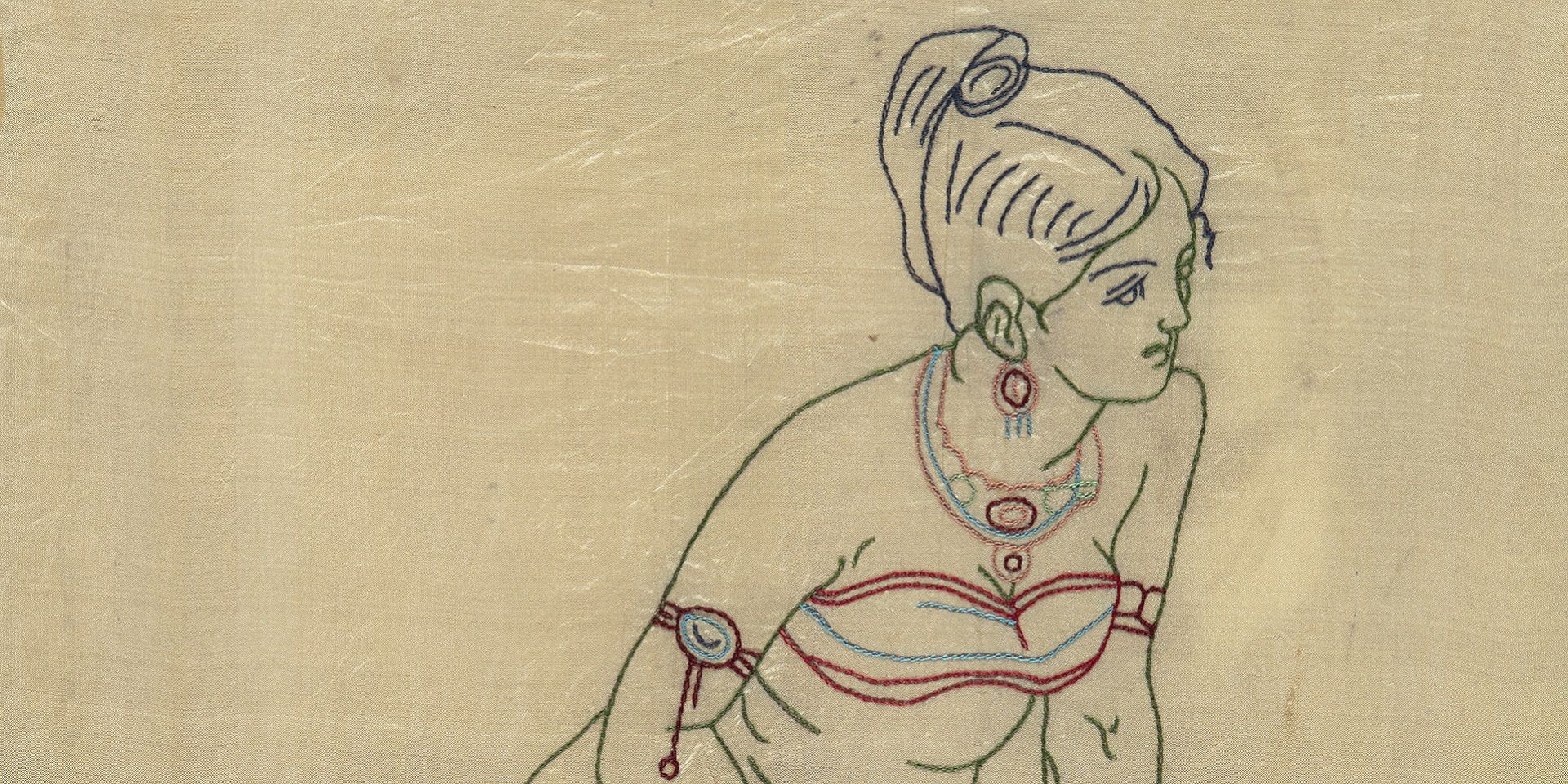

Artist (painter attributed) Sahifa Banu, The Son Who Mourned His Father, c. 1620, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 22.3 cm x 12.2 cm. Image Courtesy: The Aga Khan Museum |

You have written several art books before this aimed towards children. Are there any methods to keep in mind while writing accessible books on art for children, focusing on activating their interests in these histories?

Mamta: What writing for children demands from me is a balanced view of ‘seeing’ – to not shy away from taking an honest look at how things are but also show young readers what is worth our attention and awe. I don’t know how successful I am in doing that but that’s what the attempt is, at least. I think it’s also important to give children a more comprehensive and inclusive idea of art; to help them see the history of art as a continuum while also showing them how any art form or idea changes and evolves over time. This, I think, can liberate the thought process of children and foster creativity and ingenuity in them, thereby encouraging young people to think up ideas, explore them visually and bring their own dreams, imaginations and stories to life!

|

Radha (Bani Thani), Kishangarh, ca. 1750, National Museum New Delhi. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

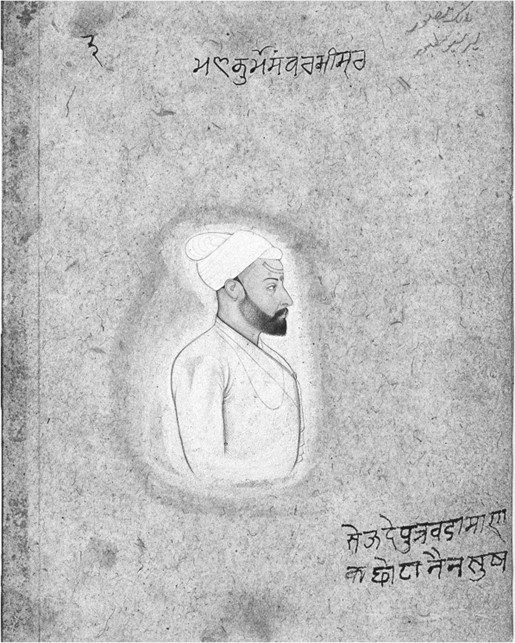

Portrait of Manaku by his brother Nainsukh (c. 1740). Tinted brush drawing on paper, 16.3 x 12.7 cm. Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh D-116. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

’Conversations with Friends’ is a series where we speak with inspirational figures from the art world who are working behind the scenes.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

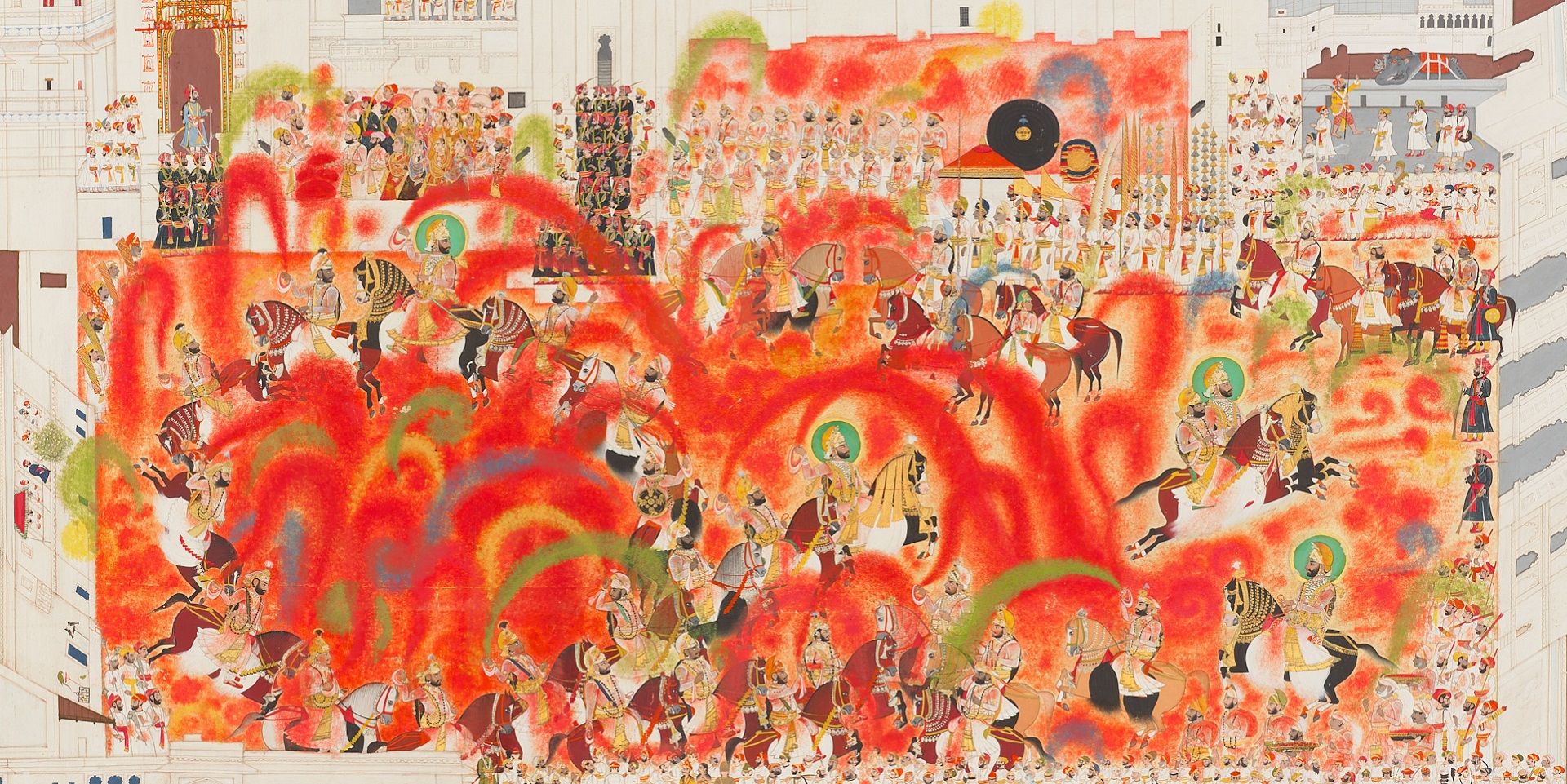

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

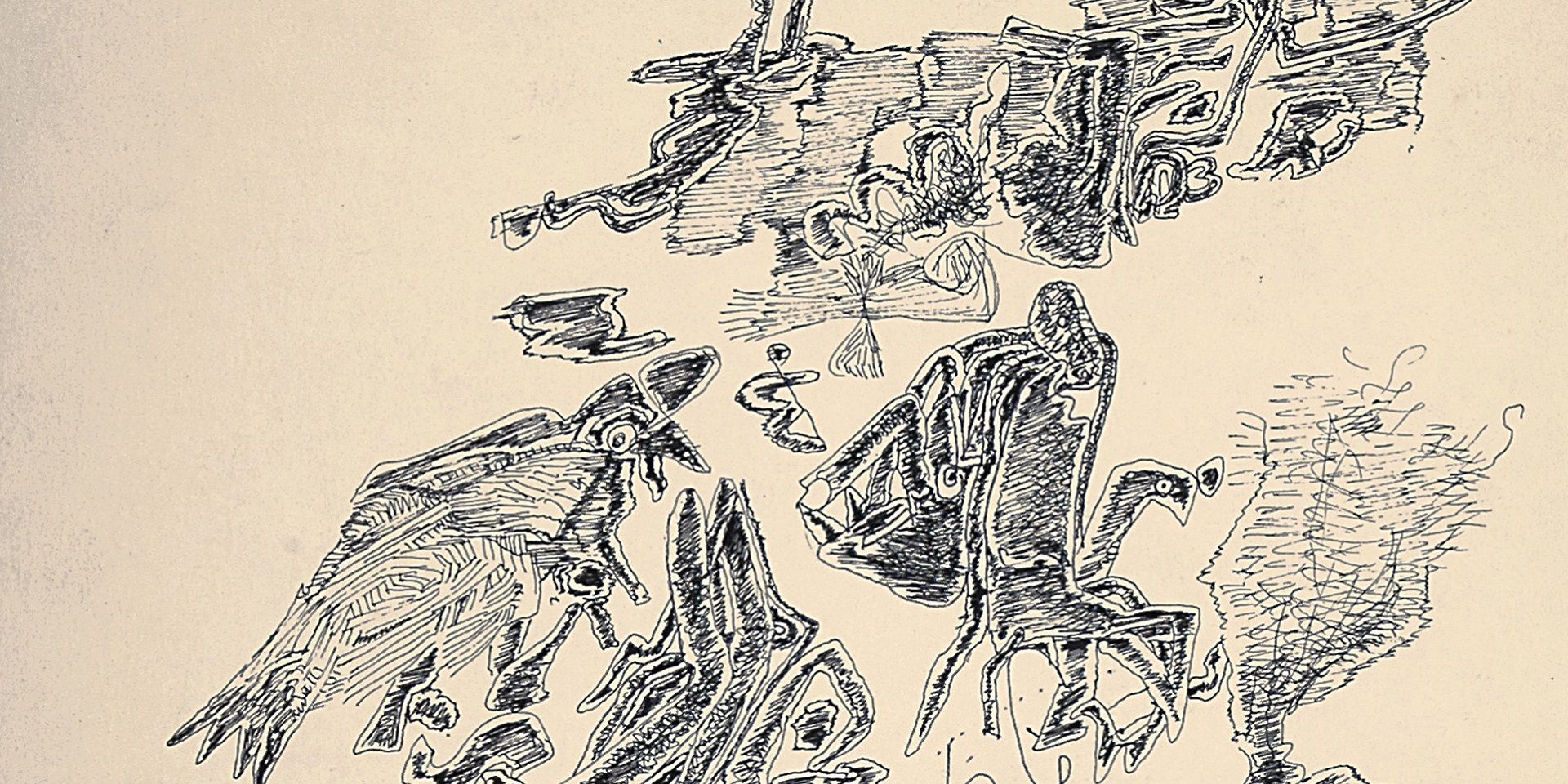

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

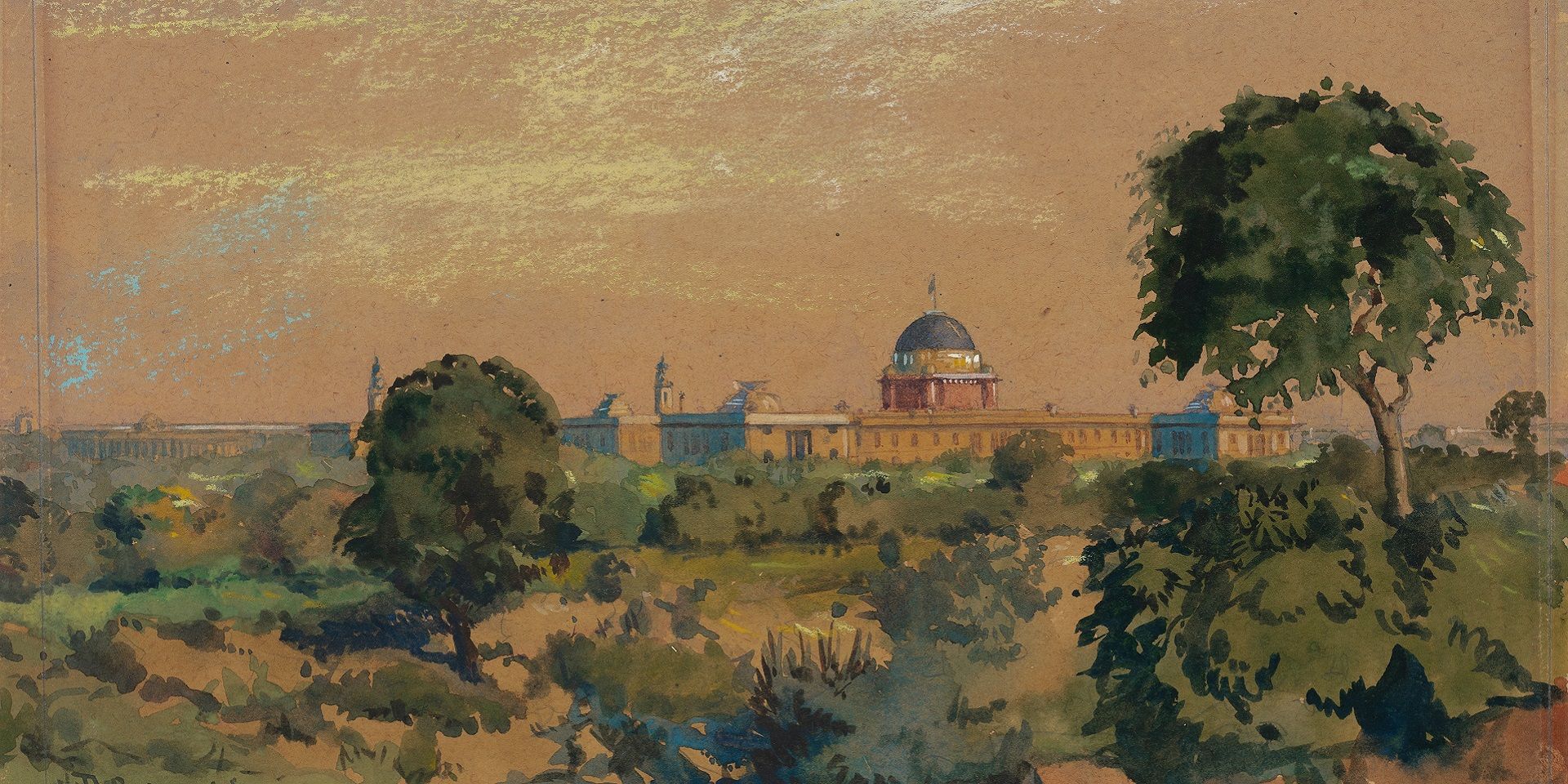

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

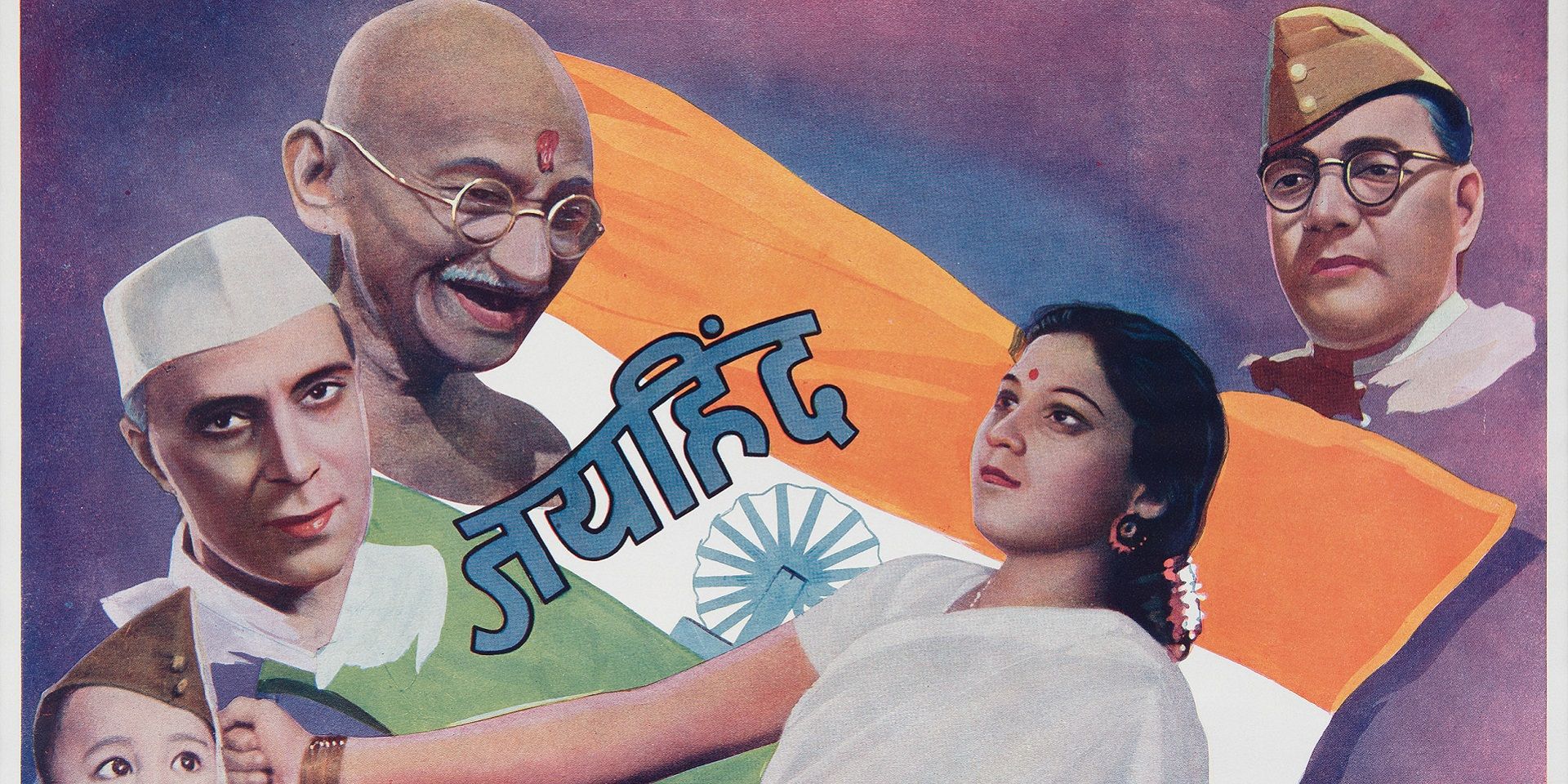

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

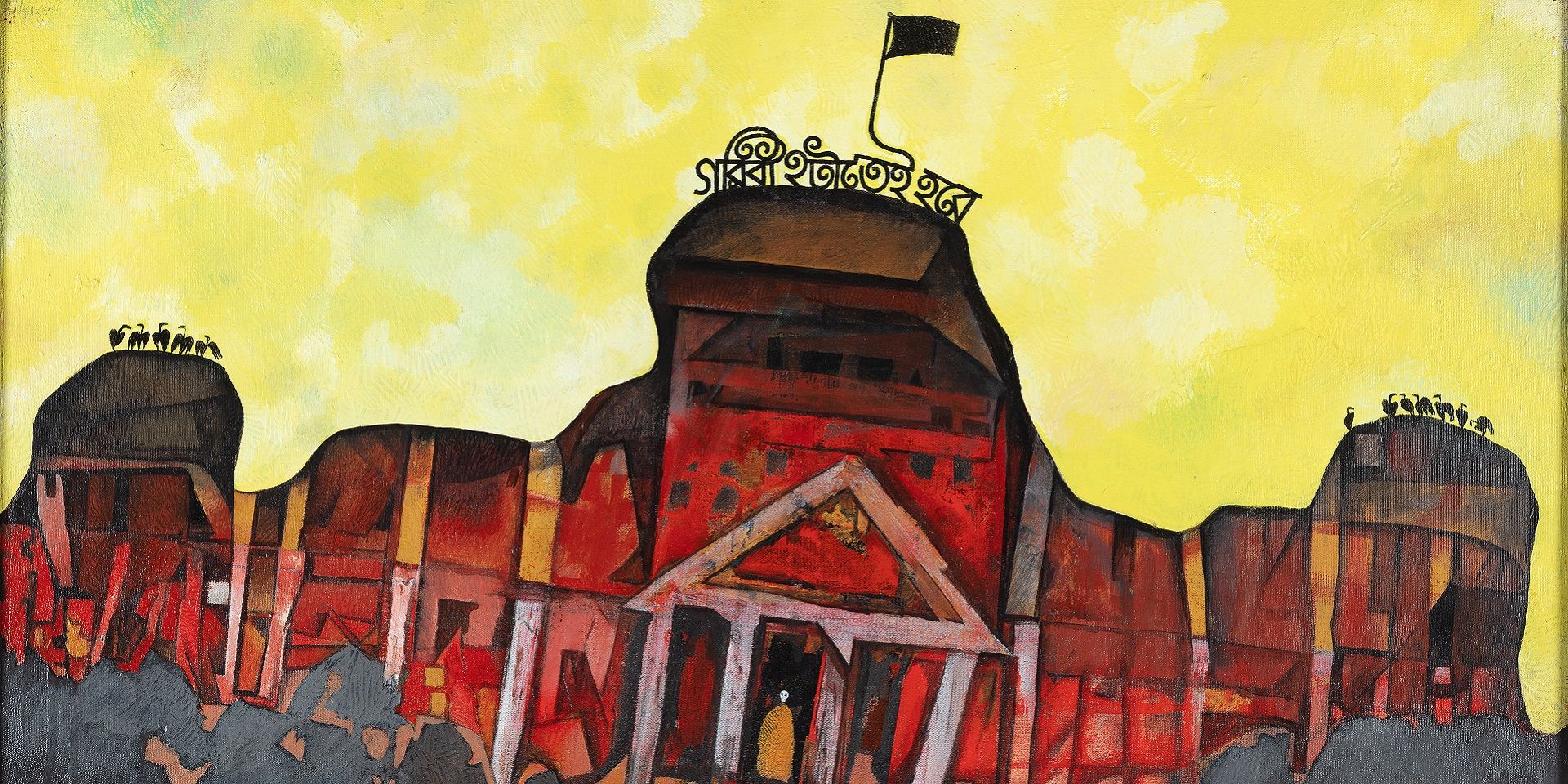

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025