Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

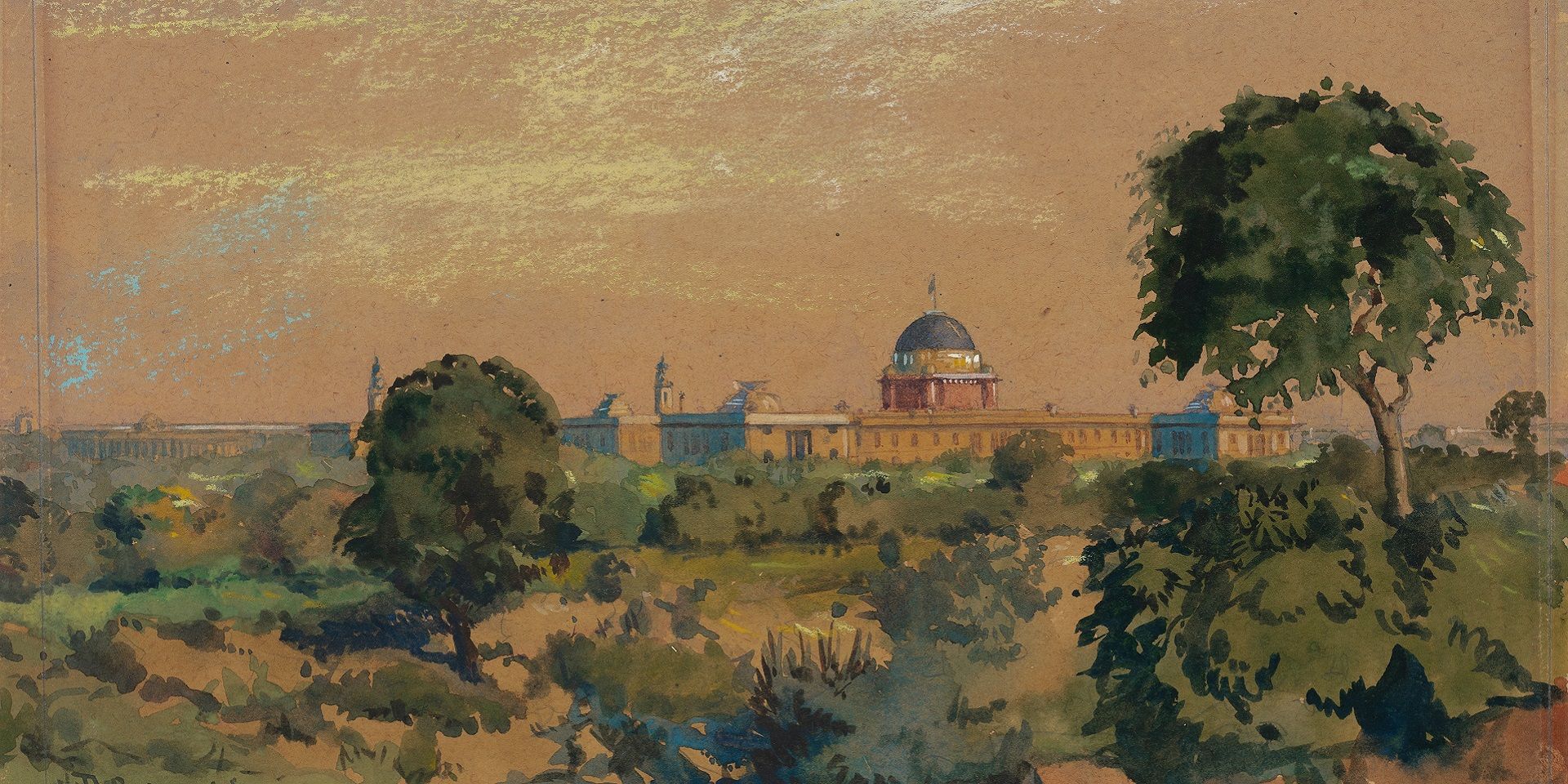

David Gould Green, View of Viceroy's House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan) (detail), Watercolour and pastel on cardboard, 24.6 x 36.1 cm., 1916. Collection: DAG

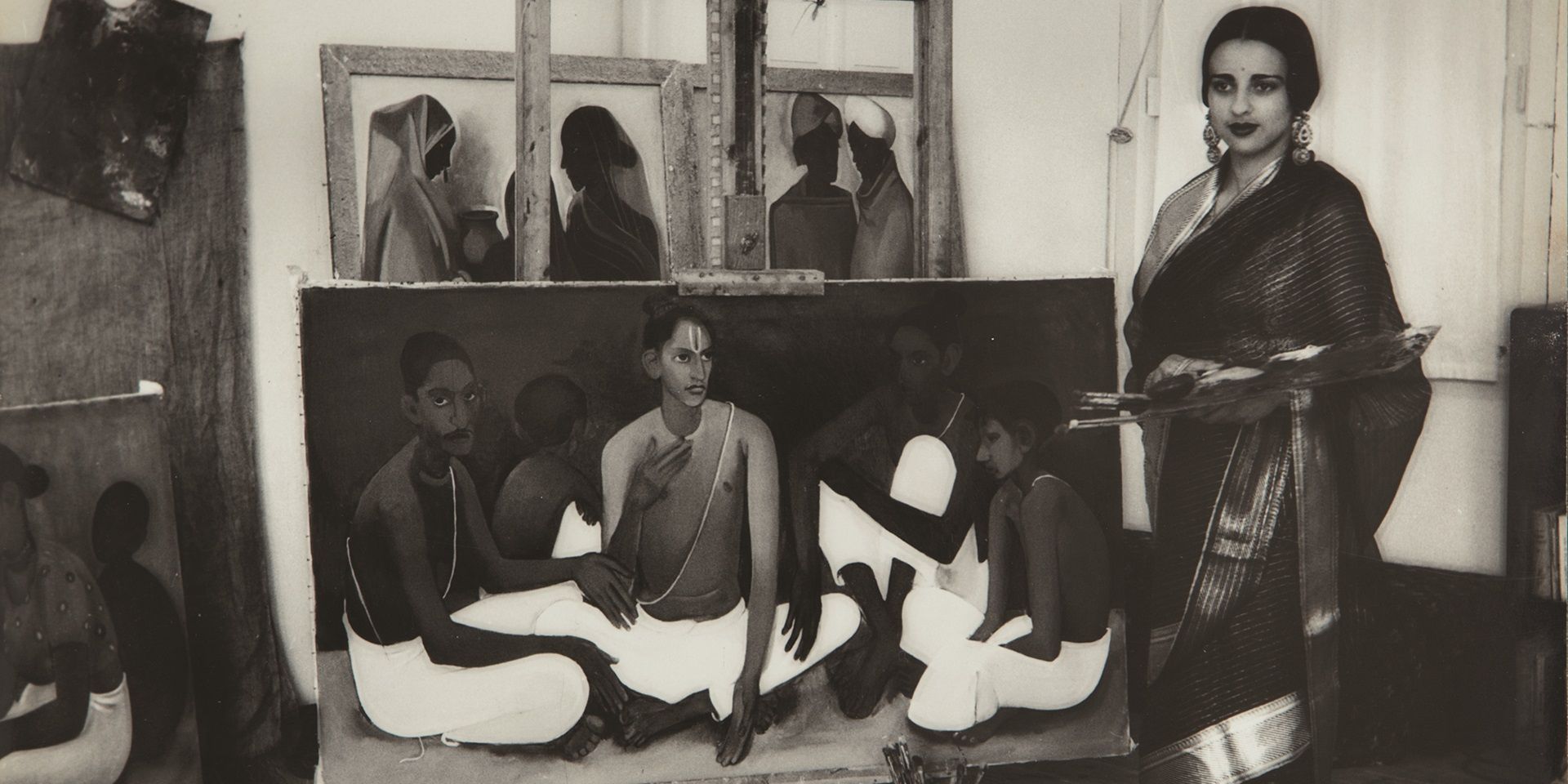

Swapna Liddle is one of the foremost historians of Delhi, with publications focusing on the formation of the modern capital city of India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She is the co-curator of a current exhibition by DAG, titled Delhi Durbar: Empire, Display and the Possession of History.

In works like The Broken Script: Delhi Under the East India Company and the Fall of the Mughal Dynasty, her focus is trained on the mechanics by which power in the city shifted symbolically and materially from the older regime of the Mughal Empire to the imperial administration of the East India Company, from 1803 to 1857, after which the Indian empire was directly administered by the British Crown. This process of transition, however, occupied a complex zone of assimilation, borrowing, disavowal and re-inscription, especially in the spheres of architecture, literature, civic administration and culture. In this conversation with the DAG Journal, she highlights the process of change in the city, the symbolic and political significance of the three British Indian Durbars and the legacies of older forms of sovereignty in India.

Unidentified artist, The Imperial Durbar (The Durbar of 1903), Chromolithograph on paper, 49.5 x 66.5 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. Since the objective of conquest without adhering to a local power structure was practically completed by the British East India Company after the revolt of 1857 was suppressed, why did the Imperial assemblage of the 1877 Durbar also refer back to Mughal symbols of royalty, accession and display—or to what extent were these older symbols re-appropriated again, while also maintaining clear differences from them?

Swapna Liddle: The relationship between the British and the Mughals was quite complex, as the British initially ruled on behalf of and sheltered behind the Mughal name for a long time. This was because the Mughals were seen as the traditional rulers of India, and the British felt that they needed to maintain this perception in the minds of the Indian people in order to maintain their own power.

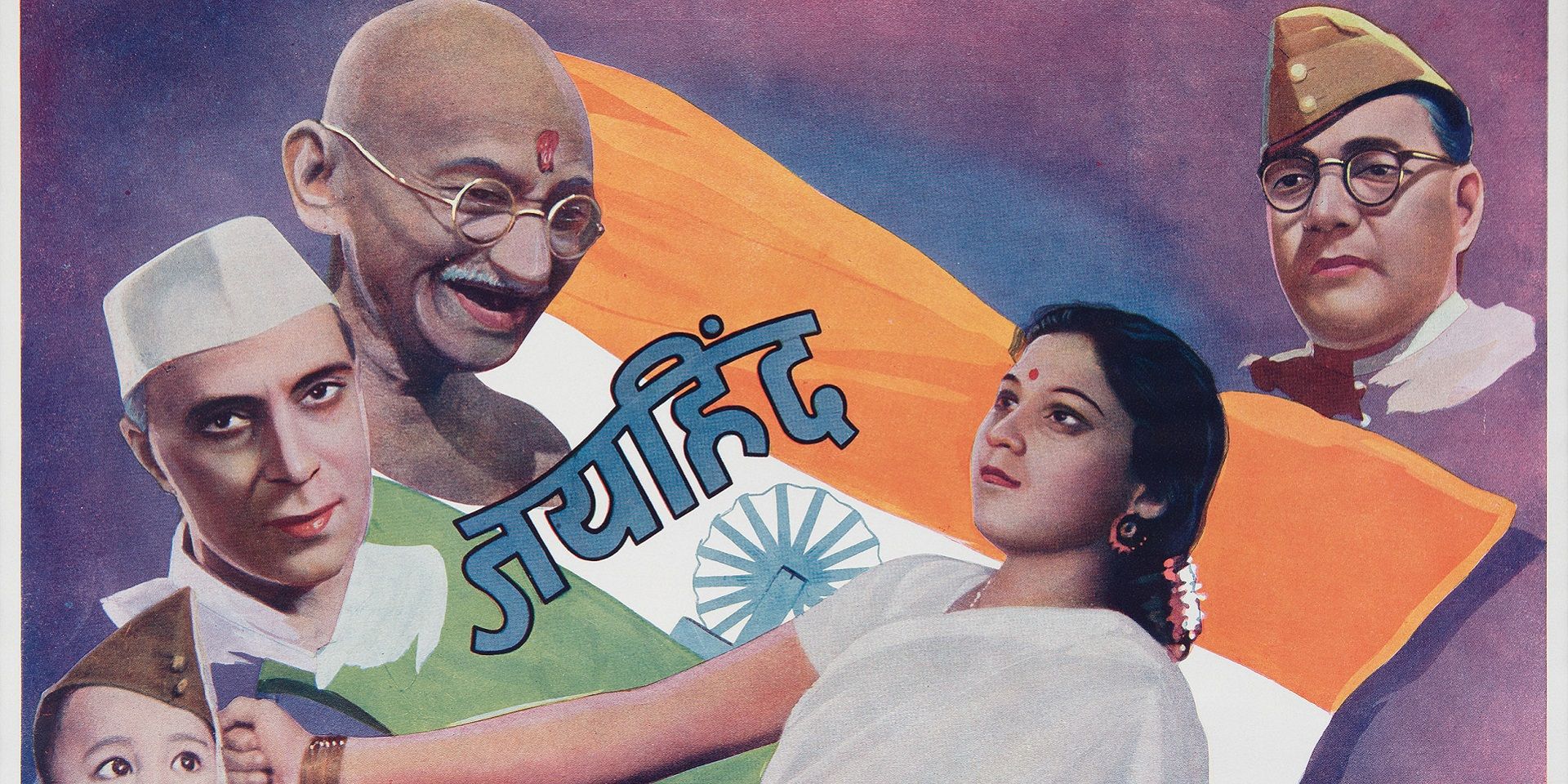

However, the events of 1857, (also known as the Indian Rebellion or the First War of Indian Independence), changed the British perception of the Mughals. The British eventually suppressed the rebellion, but they realized that leaving the Mughal Emperor sitting in the Red Fort could be dangerous, as he could become another center of power and potentially lead another rebellion. After that they chose to get rid of the Mughal emperor altogether, and it was decided that the East India Company’s rule would be replaced by direct rule by the Crown, meaning the British government because it was already a constitutional monarchy there. So it is the British Government, but the face of that rule was the British Crown, in this case, Queen Victoria; so it was felt that in India—since so many people had rallied around the Mughal emperor himself in 1857—if you have to replace the Mughal emperor, you have to replace him with another kind of charismatic ruler, therefore Queen Victoria was the one who was put forward as this benevolent, but firm monarch who would rule over India.

|

Her Majesty Queen Victoria, Empress of India, From Colnaghi's The History of the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi, Silver albumen print on paper mounted on paper, 19.0 x 11.9 cm., 1877. Collection: DAG |

At that stage, the ‘Emperor’ or ‘Empress’ title was not considered. By 1877 there were a lot of other rulers in Europe who bore such titles, such as the Emperor of Russia, for instance. So Queen Victoria herself felt that, in order to take her rightful place in Europe, she needed an imperial title and it was decided that the title ‘Empress of India’ would be suitable. So, to some extent, this was also about the politics that were happening in Europe and in Britain itself.

Queen Victoria, interestingly, gained significant popularity in India. The reasons behind this might not always be obvious for us, but it was due to the positive perception of her among the general populace. Despite criticism directed at the British government in India, Queen Victoria herself was generally well-regarded. This positive view was shaped by her seemingly benign proclamations. The negative aspects of British rule were often associated with the government's actions rather than her personal image. However, there was a careful balancing act involved. The intention was to maintain this sense of grandeur without overly emphasizing Mughal symbolism. Hence, in 1877, the event was not referred to as a ‘Durbar’ but as the ‘Imperial Assemblage’.

|

Historians of the event were mindful of calling it an 'Imperial Assemblage', as can be seen in the title of a popular account of the 1877 event by J. Talboys Wheeler. Collection: DAG |

Q. Besides establishing a continuing lineage with the immediate/Mughal past, the British administration was making appeals to a wider rule of sovereignty that would even introduce elements from further in the past, including mythic memories of Indraprastha, for instance. Why did the colonial administration feel the need to wade into such mythical pasts, especially from 1877 onwards, even finding new ways to justify the elephants in the procession?

Swapna: I believe the strategy employed by the British was centered around the aura of Delhi. There's this notion of Delhi having a historical prestige, a sense of power. Akbar played a significant role in shaping this perception. Abul Fazal, the author of the Akbar Nama, established a lineage of rulers who had governed Delhi, creating an uninterrupted chain from Indraprastha. However, this notion is flawed. Delhi truly emerged as a major power center from the early thirteenth century during the Sultanate period. Before that, it wasn't even prominently mentioned in historical accounts. The name ‘Delhi’ itself only appeared around the eleventh century or so.

Claiming that Delhi had been the capital of India since the time of Indraprastha is imaginative and historically inaccurate. This concept was first introduced during Akbar's reign and he aimed to depict himself as part of a long line of rulers who had governed from Delhi. By his era, Delhi had become deeply entrenched in people's minds as the epitome of power in India, owing to the centuries of Delhi Sultanate and early Mughal rule, such as during Akbar's and Humayun's reigns.

The British latched onto this existing narrative, drawing upon this historical association with power. Their perspective wasn't limited to Mughal history but also included the Sultanate era and even figures like Prithviraj Chauhan, despite the fact that the Chauhans hailed from Ajmer. It's essentially a constructed history, but one that captivated imaginations and continues to do so.

|

V. B. Pathare, Indraprastha, Delhi, Watercolour on paper, 38.9 x 26.7 cm., c. 1950. Collection: DAG |

Q. How did the British public back in Europe respond to the Imperial assemblages organized by the rulers of the Empire? Did sovereign displays like these inform royal displays or processions in Britain too? How were the innovative architectural features and designs received by people in India and Britain?

Swapna: The concept of ‘Picturesque India’ had already taken shape by the late eighteenth century, especially as images of India began to circulate in Britain during that period. Artists such as the Daniells and Hodges played a significant role in this, as they sent back images of India's landscapes and architectural marvels. These visuals contributed to shaping a specific perception of what Delhi and India were like in the minds of the British public. This influence extended to the design of country homes and even structures like the Brighton Pavilion, with many architectural and decorative elements drawing inspiration from Indian themes. Therefore, the imagery of India projected through events like the Durbar was not entirely novel.

However, the Durbar did serve as an occasion to celebrate British rule in India and generate a sense of pride about it. Interestingly, a recent example of the coronation of Charles III highlighted the enduring relevance of such ceremonial events. Despite the monarch being perceived as less glamorous, the event generated significant enthusiasm and strong emotions among the British public. It underscores the importance of monarchy in uniting people, which is valuable for any ruling authority, as unity tends to be a positive force.

The Royal Pavilion, Brighton. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Daniell, North East view of the Cotsea Bhaug, on the River Jumna, Delhi, 1795. Collection: DAG

While I haven't extensively studied the impact of the Durbar in Britain, I assume that the media coverage and related events would have bolstered the image of the British government in India. This would have conveyed the message that British rule was popular, well-received, and beneficial for India, ultimately contributing to the positive perception of British rule in India.

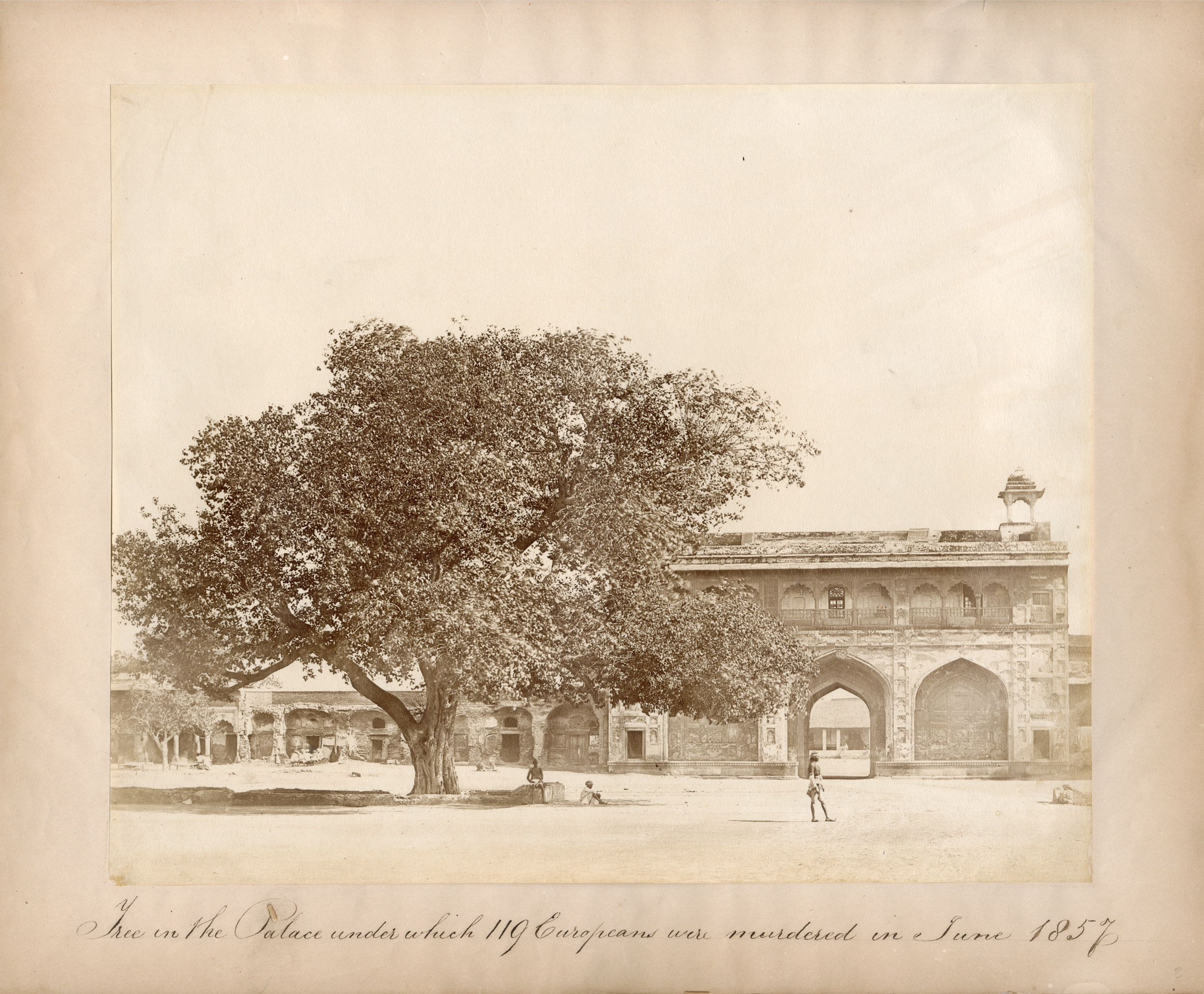

In the specific case of Delhi, it further propelled the city into prominence. Prior to this, Delhi was already a notable destination due to historical events such as the 1857 uprising, albeit for negative reasons. The city had become a stop on the tourist trail, particularly on the ‘1857 trail’ where travellers visited places like Kanpur, Lucknow, and Delhi to witness sites associated with British heroism during the 1857 uprising, as perceived in the British imagination. Consequently, Delhi was already on the map for tourists, albeit with a different focus.

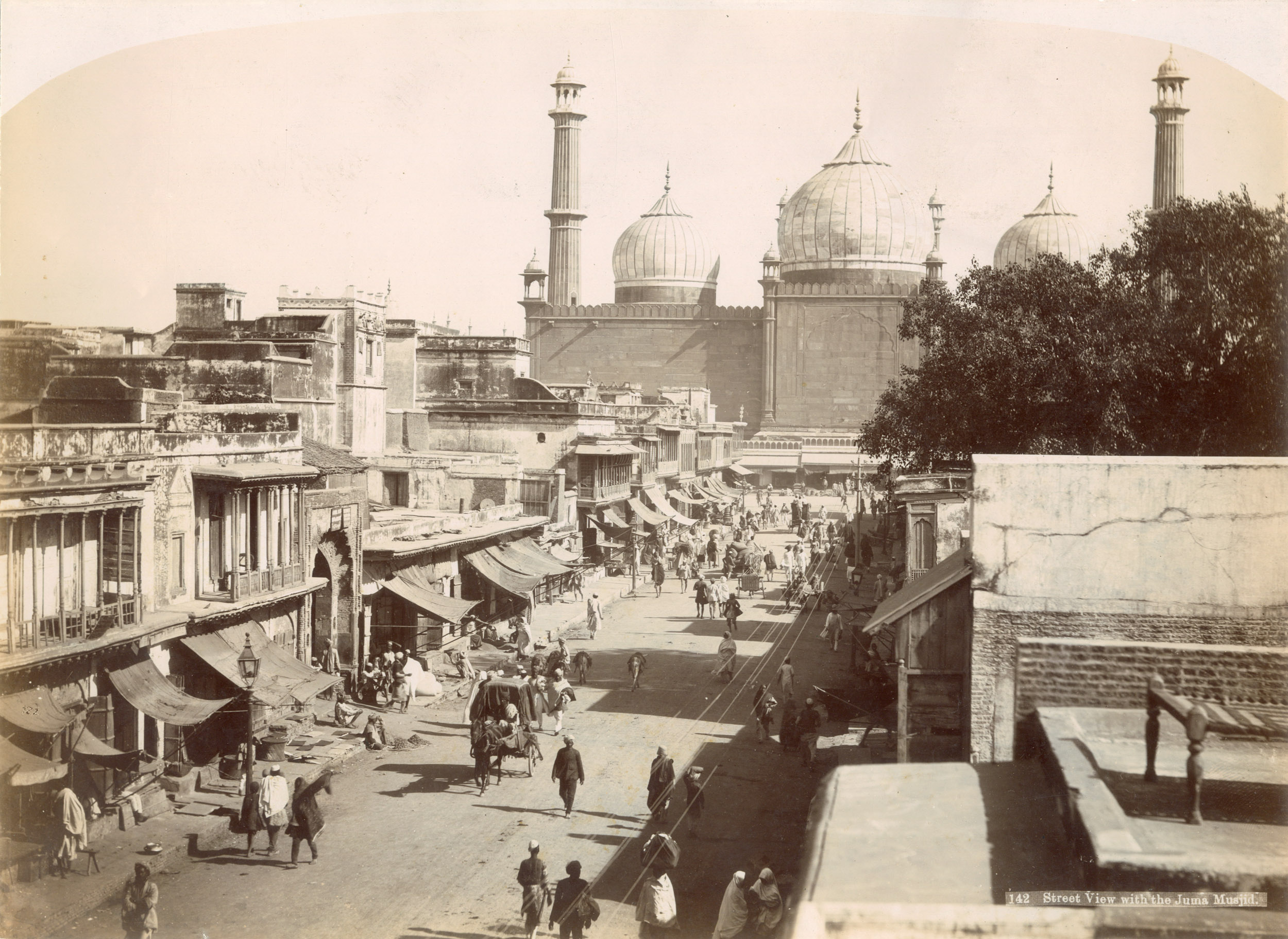

However, with this event, Delhi underwent a rebranding process, being reimagined as a city rich in monumental architecture and historical significance. This transformation had actually begun earlier, around 1877, when official records of the Darbar featured photographs from renowned photographers Bourne and Shepherd, showcasing scenes from Delhi. These visual representations served as a captivating way for people to discover the city.

In 1903, a guidebook titled ‘Fanshawe’s Delhi Past and Present’ was published, a book that remains in print and has become the most popular guidebook to Delhi. This guidebook, like many others that followed, highlighted Delhi as a space brimming with history and monuments, often mentioned as a must-visit in travel guides. These guides typically suggested spending 3 to 4 days exploring the city. Consequently, Delhi found a significant place in the imagination of travellers, marking it as a prominent destination on the tourist map.

Felice Beato, Tree in the Palace under which 119 Europeans were murdered in June 1857 (Naqqar Khana, Red Fort), Silver albumen print on paper mounted on paper, 24.3 x 30.4 cm., 1858. Collection: DAG

Q. The Durbars were also meant to display Britain’s colonial possessions to the world outside Britain and its empire, which was confirmed by the large presence of visitors, journalists and photographers from America and elsewhere, such as James Ricalton. What were some of the large-scale changes in attitude towards British rule brought about by the Delhi Durbars for observers?

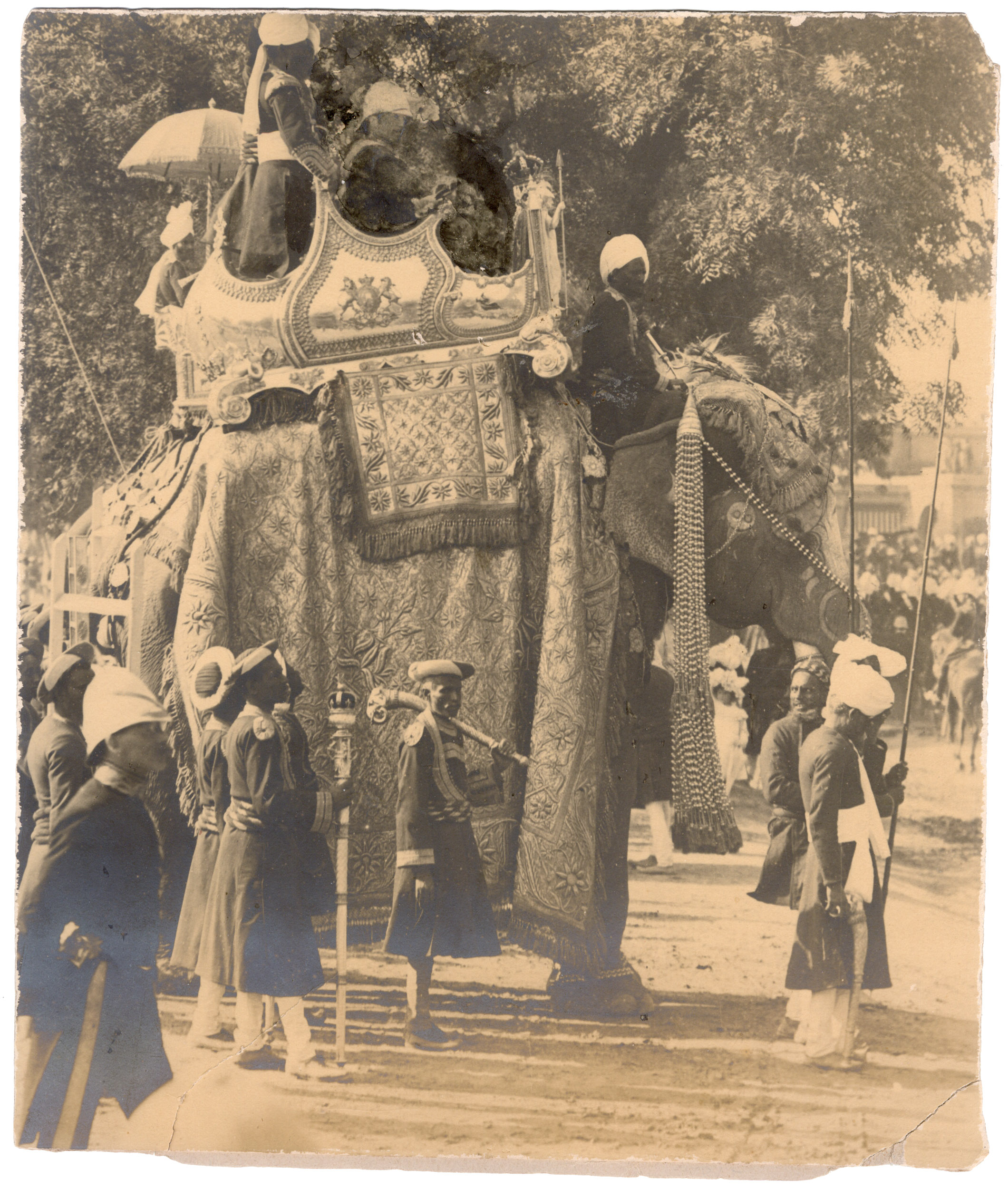

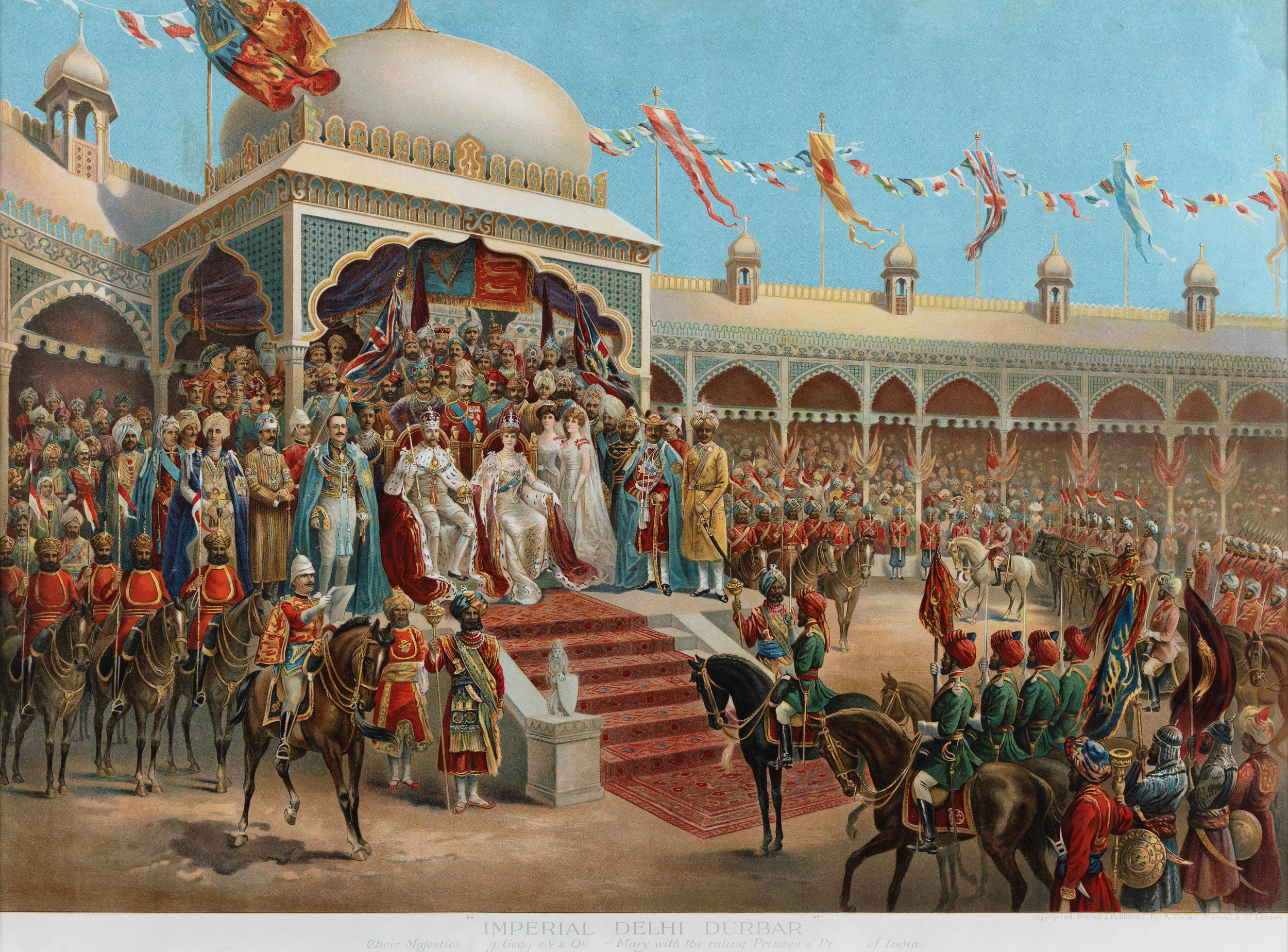

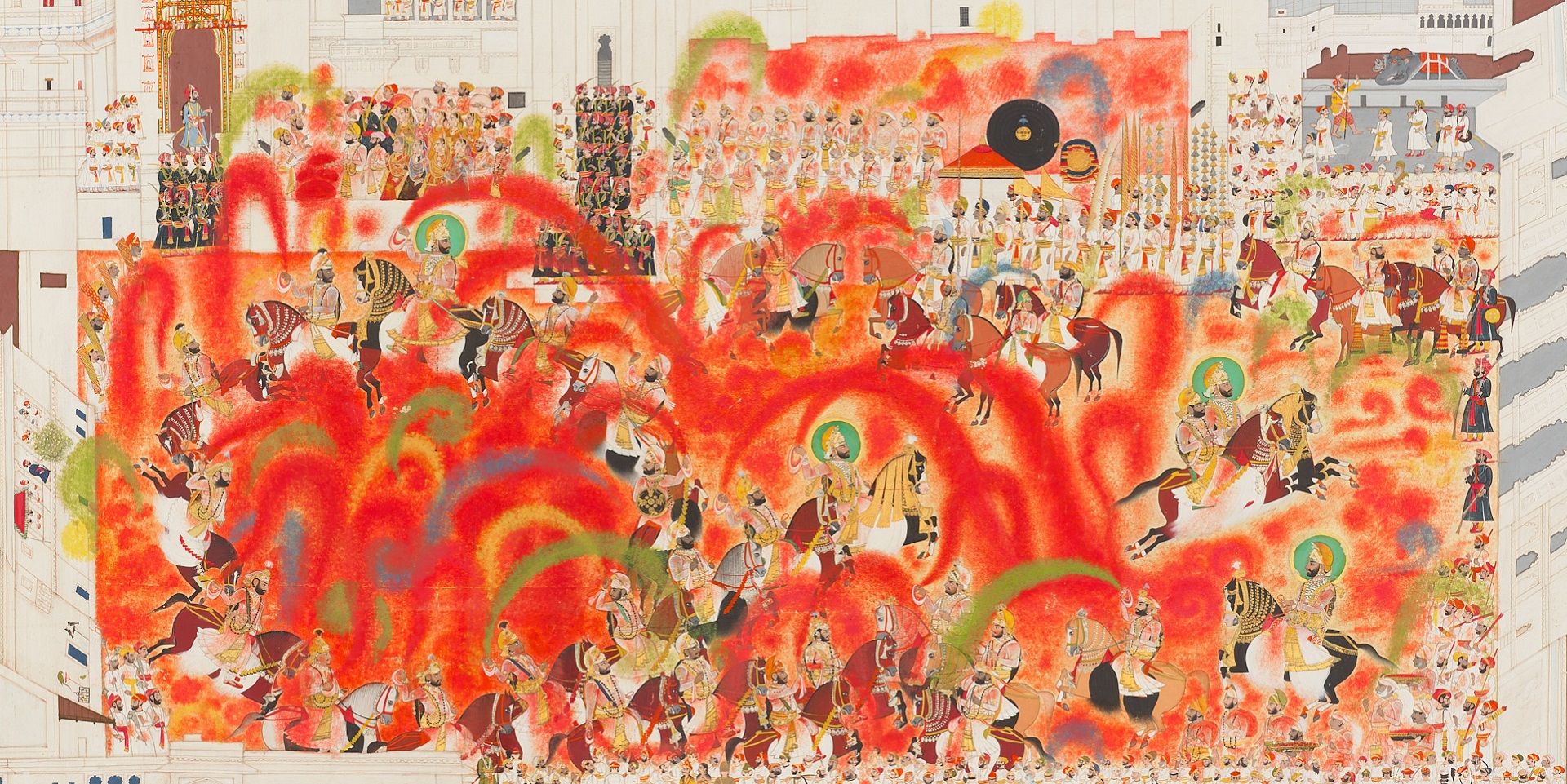

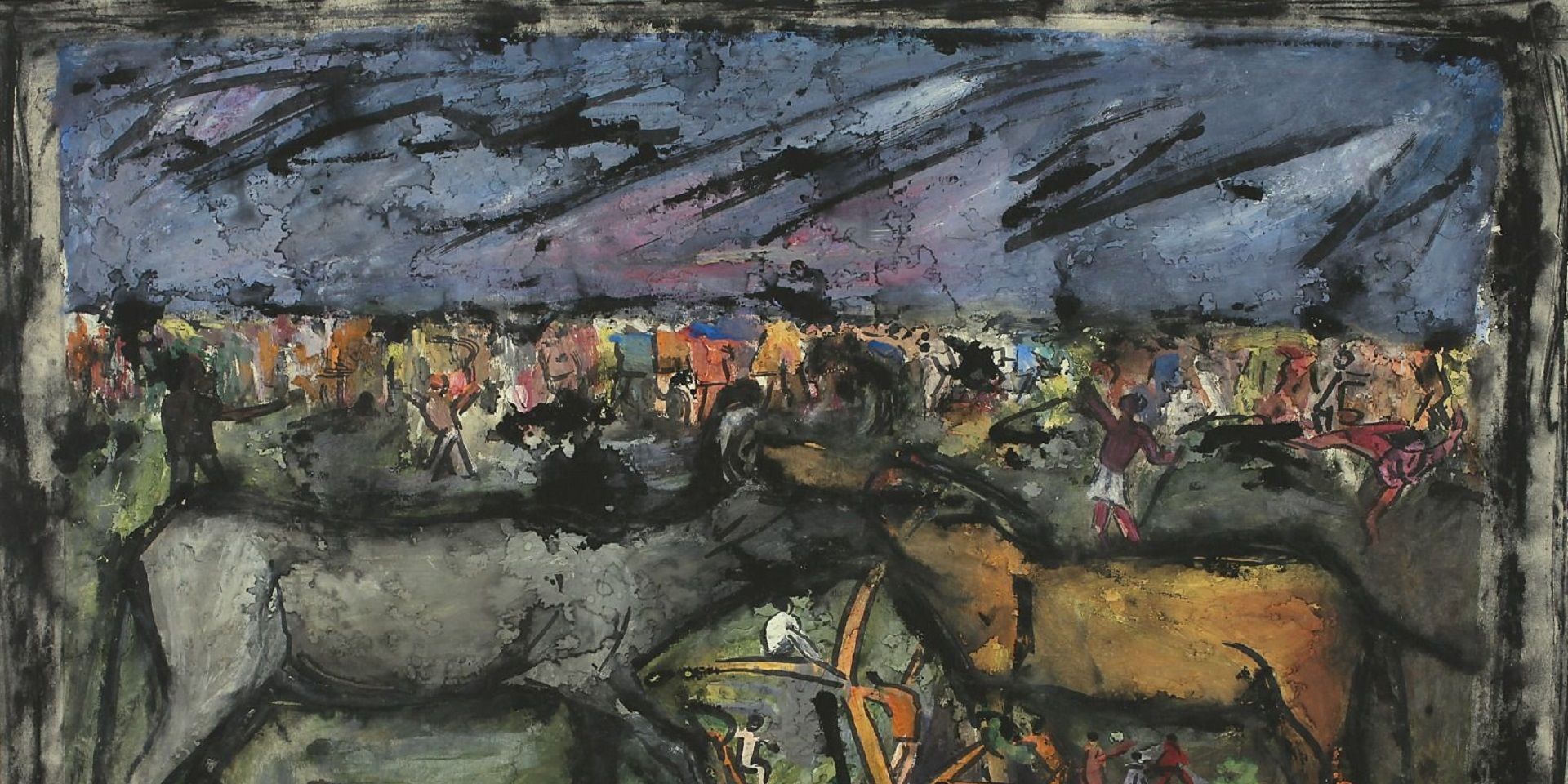

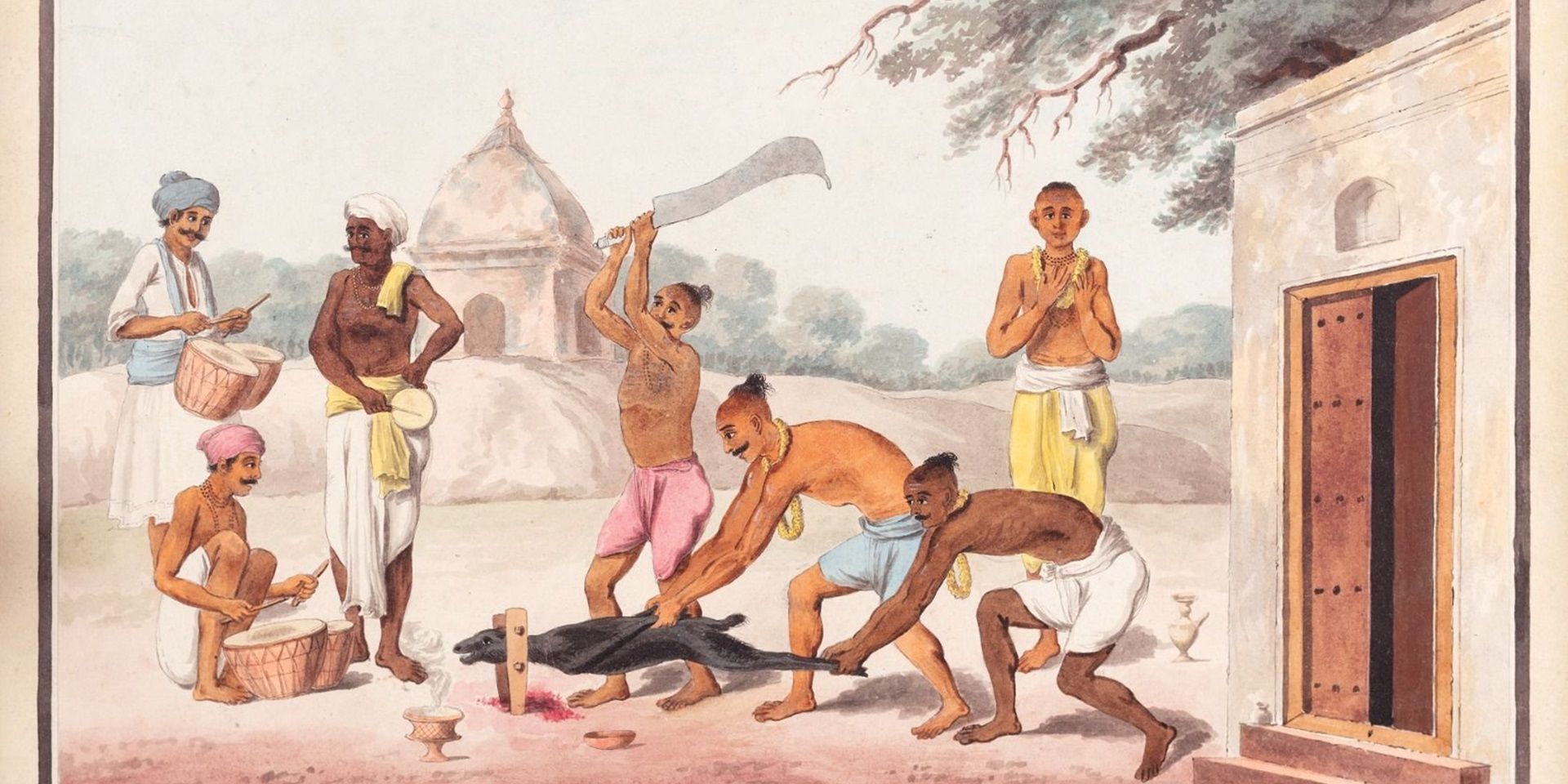

Swapna: I believe that the two Durbars, 1903 and 1911, are fundamentally different in some ways. In 1903, Curzon gathered the Indian princes, showcasing the might of British rule supported by traditional and princely India. This event was a spectacle of wealth, glitter, and the rich crafts of India, displayed through exhibitions in the Red Fort and darbar pavilions. The procession of elephants added a picturesque element, enhancing the grandeur. Moreover, technological advancements were crucial. While recording the Imperial darbars, the British emphasized their role in bringing order and modernity to India, especially Delhi, through efficient postal systems, electricity, and piped water. They transformed a wilderness into a city overnight. This contrasted with the old traditional India, illustrating the complex message of change. The British not only brought modernity but also contributed to rediscovering India’s past, with Curzon's involvement in the Archaeological Survey of India, emphasizing restoration and preservation. Hence, it was the British who rescued India’s traditions and simultaneously introduced modernity.

Lal Chand & Sons, Street View with the Juma Musjid (Jama Masjid), Silver gelatin print on paper, 20.8 x 28.7 cm., late 19th century. Collection: DAG

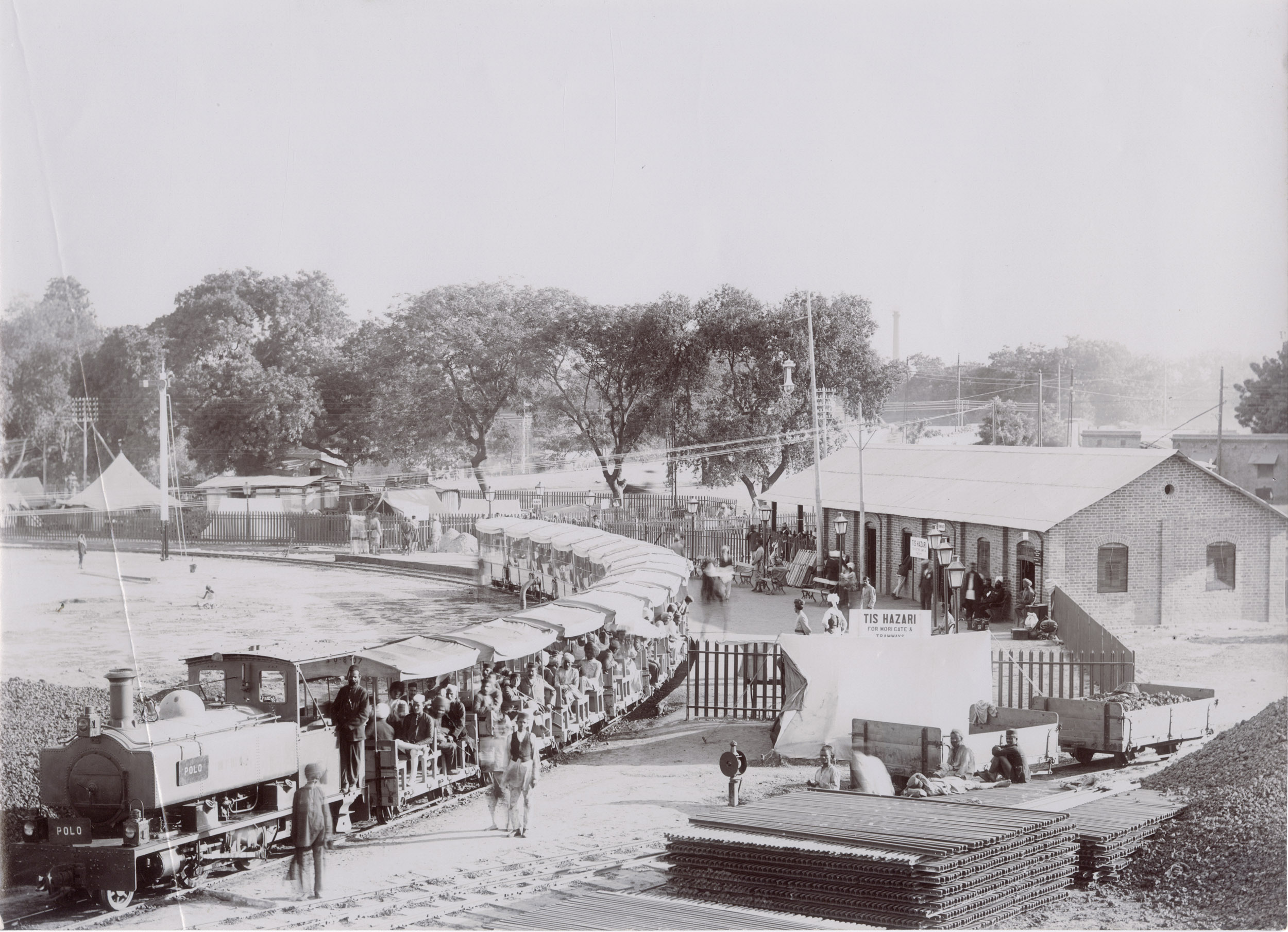

Unidentified photographer, Durbar Railway (Narrow gauge at Tis Hazari Station), Silver gelatin print on paper, 20.8 x 29.2 cm., 1911. Collection: DAG

However, 1911 marked a significant shift due to the changing British attitude towards India. This change was largely a response to the growing national movement, which gained momentum after Curzon’s failed attempt to partition Bengal. There was a realization that power needed to be shared; the British Empire could no longer dictate what India's relevant identity, aspirations, or historical foundations should be. These determinations were now the domain of Indian aspirations, including those of both the princes and the people, as represented by various leaders of British India.

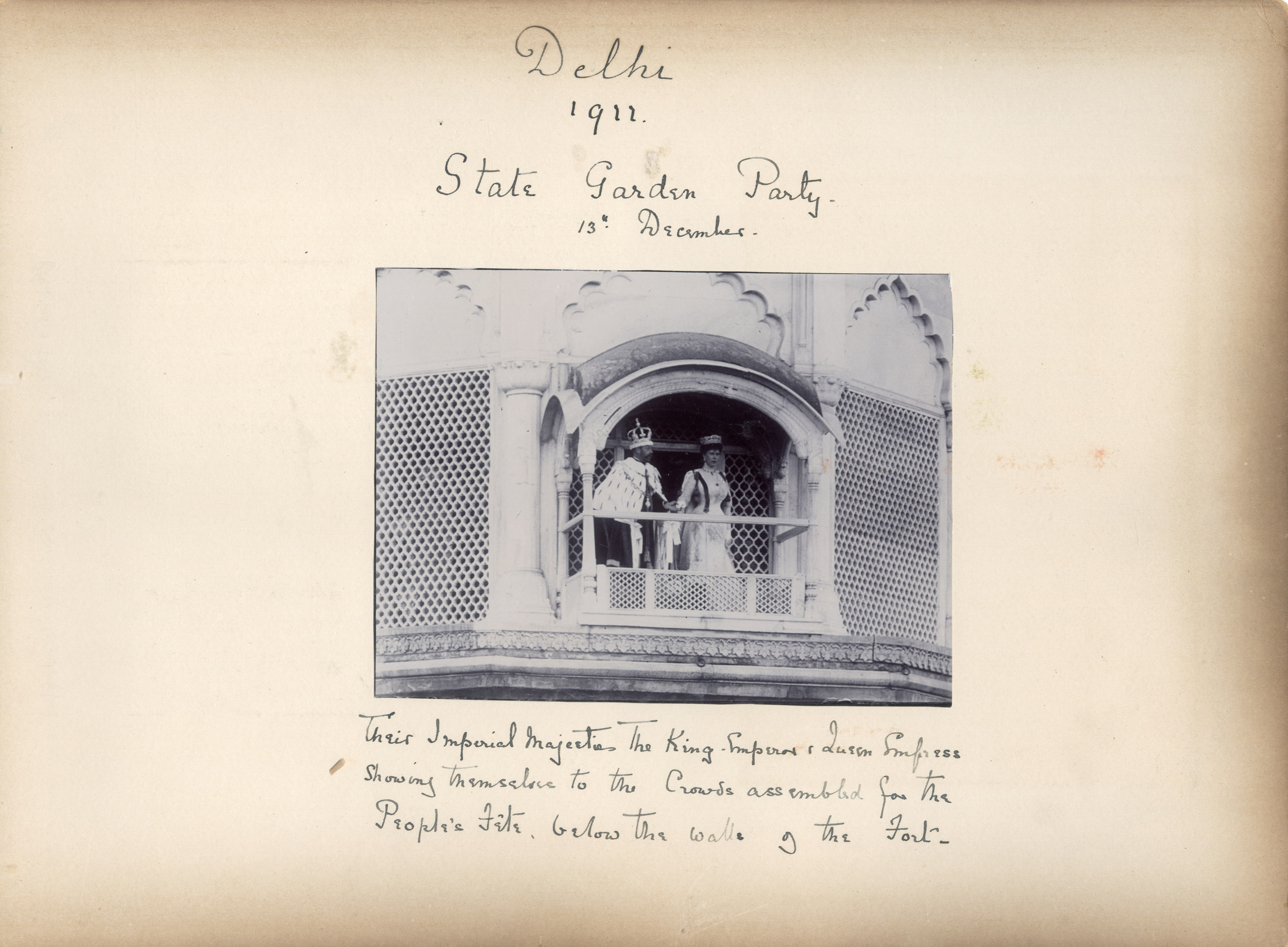

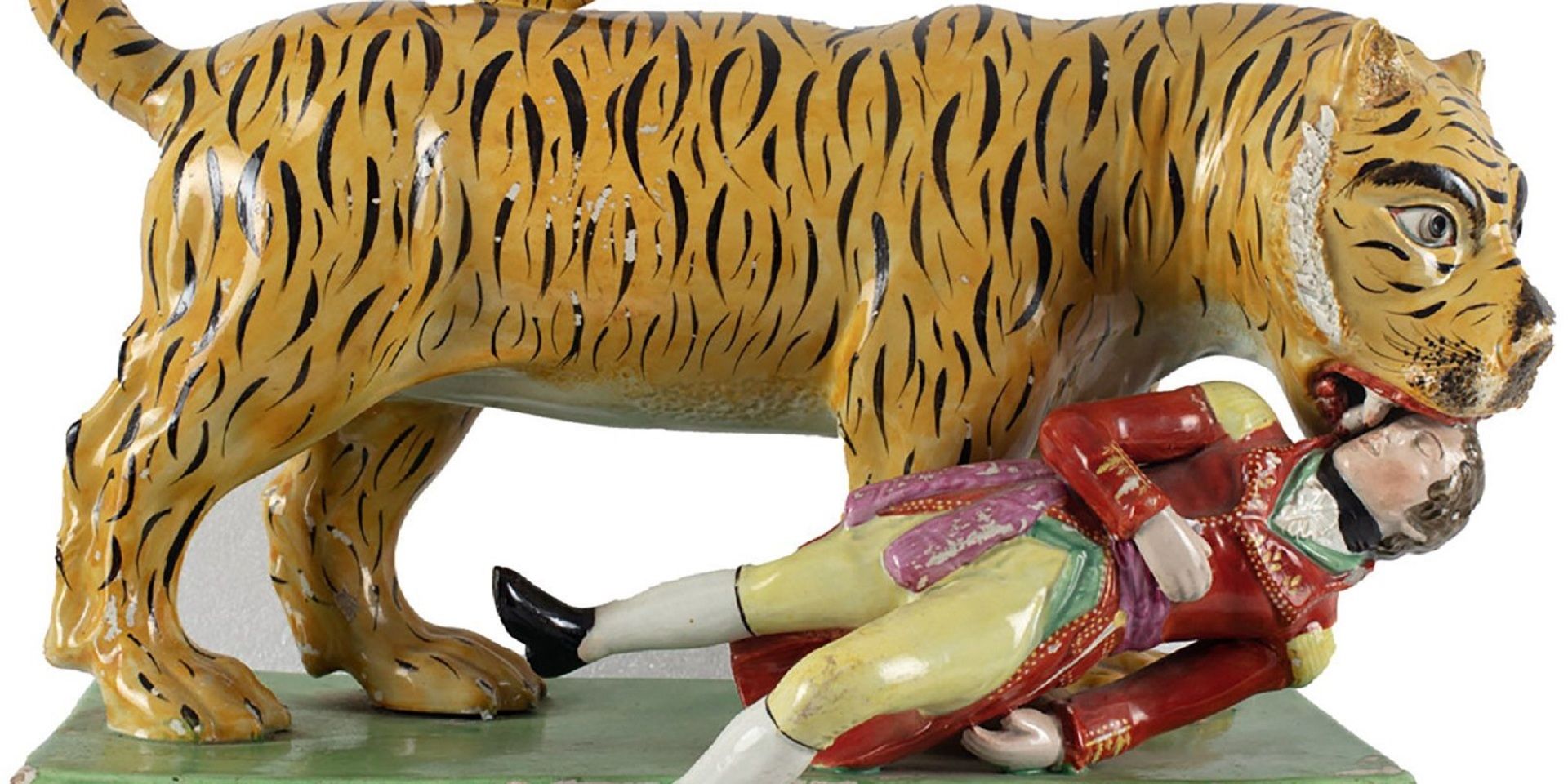

As a result, the 1911 Durbar took a markedly different form. It sought to involve more people and gain popular support. Instead of a royal ball in the Red Fort, there was a smaller, less extravagant garden party, with the focus shifting to the Badshahi Mela held on the Red Fort's sands. Despite these modern elements, efforts were made to establish a connection with India's Mughal past. This was evident in rituals like the riding out from the Delhi gate of the Fort and the Jharokha Darshan, where the emperor presented himself before the assembled subjects on the riverbanks. These gestures were clear attempts to align with Delhi's historical significance as the capital of the Mughals and other dynasties, aiming to make British rule more acceptable to the Indian people in the face of their demands for greater power sharing.

The crowds assembled for the fête, or ‘Badshahi mela’, on the banks of the river beside the Red Fort, saw George V and Queen Mary framed in the window known as the Jharoka-e- Darshan. The scene was designed to invoke the tradition of the Mughals, who had stood at the same window to enable their subjects to see them. Collection: DAG

|

Unidentified photographer, Lord and Lady Curzon atop the elephant Lakshman Prasad, Silver albumen print on paper mounted on card, 24.1 x 20.5 cm., 1902. Collection: DAG |

Q. In numerous photographs of the Durbar, ordinary crowds can be seen gathered and organized. Do we have any sources or information about how these crowds were managed? Furthermore, do you think there was a political motive behind assembling such large crowds and portraying them as passive spectators during the royal displays?

Swapna: Yes, I think the event in 1877 primarily focused on marshalling the Indian princes together. There were limited arrangements for the general spectators; it was assumed they would attend but not much provision was made for their comfort or experience. They were essentially just spectators, not given much consideration. By 1903, some designated space was allocated for spectators and attendees. However, the main focus remained on the V. I. P. guests who were expected to attend the event.

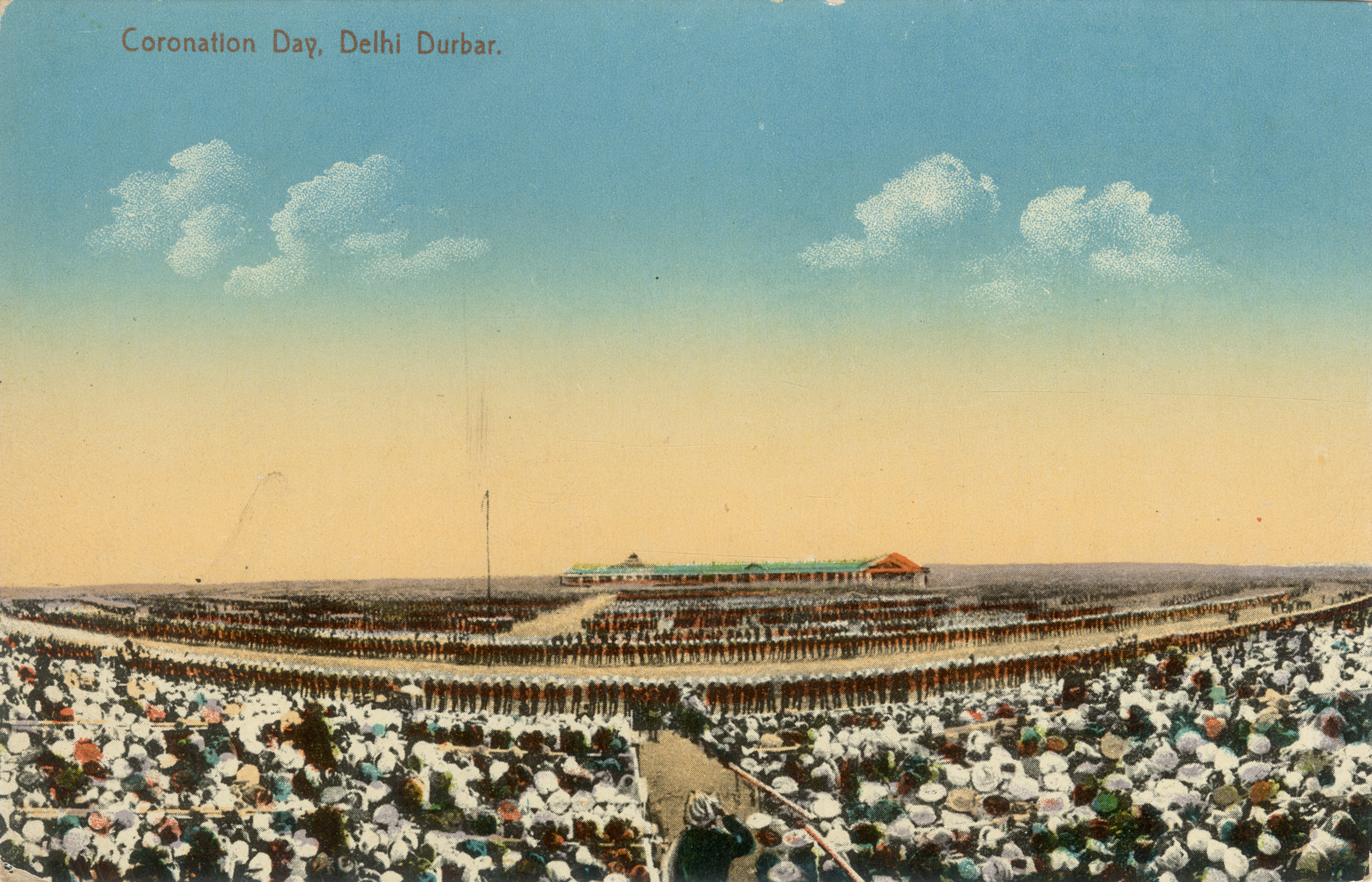

In 1911, this visibility increased significantly. There was a heightened emphasis on events like the Badshahi Mela, where activities such as wrestling matches, cultural performances, and fireworks took place. The main objective was to gather a crowd for the Mela, allowing them to witness the Emperor and Empress. These gatherings were grand, with even school children being brought together along the road from the Red Fort to the Jama Masjid. Large stands were erected for the Proclamation Day ceremonies, emphasizing that this event was not just for the elite but for all the people of India. This marked a departure from the 1903 Durbar, which had faced criticism for catering only to the aristocracy. The 1911 event aimed to include the common people, evident in the massive crowds and purpose-built stands for their benefit. When the Emperor wore his crown, he faced these popular spectator stands (with the princes behind him), signifying a shift towards acknowledging democratic rule. This change was a response to the growing national movement, demonstrating popular support and drawing people in due to the spectacle it presented.

Mansell & Co., Imperial Delhi Durbar, Oleograph on paper, 49.5 x 66.0 cm., 1911. Collection: DAG

Coronation Day, Delhi Durbar, postcard. Collection: DAG

Q. How did the politics of display, the architecture of the camps, pavilions and infrastructure—made to host the Durbars—feed into the construction of Delhi as the new capital of the colonial administration in the public imagination? What is the legacy of these grand events on the life and architecture of the city today?

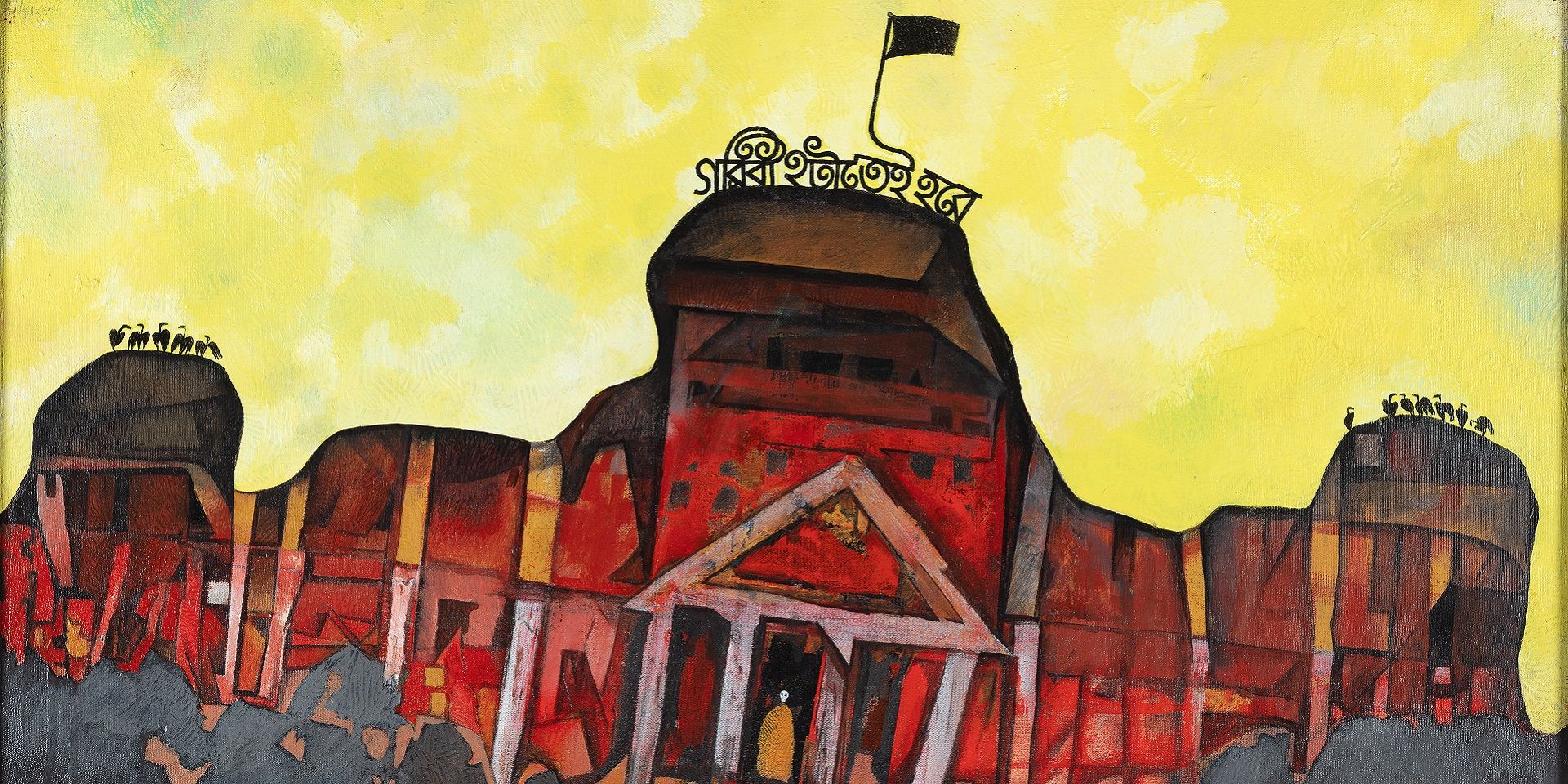

Swapna: The concept behind the Delhi Durbars and the decision to hold these grand coronation celebrations in Delhi, rather than in Calcutta, the then-capital, was deeply rooted in political considerations. This decision was influenced by the belief that, from the perspective of the Indian populace, Delhi held the status of the traditional capital. Consequently, it was deemed essential that the coronation of a king or emperor take place in Delhi. This political impulse drove the transfer of the capital as well. The rationale was that locating the capital in Delhi would be more acceptable to the majority of the Indian population. Therefore, the choice to establish Delhi as the capital stemmed from this political motivation, aiming to resonate with the sentiments of the Indian people.

Regarding the architectural aspects, in 1877, the intention was to differentiate the British Empire from its Mughal predecessors. Consequently, the structures built during that period did not reflect typical Indian architectural styles. However, in the case of the other two Durbars, a deliberate effort was made to adopt a style known as Indo-Saracenic. This approach represented a modern British interpretation of Mughal architecture. The aim was to blend British and Mughal influences intentionally. One of the prominent architects of this Indo-Saracenic style, Swinton Jacob, was tasked with designing the pavilions for both Durbars. In fact, he was responsible for designing the major pavilions of the amphitheatre in both instances.

H. A. Mirza & Sons, The Dais, Delhi Durbar, Silver gelatin print on paper, 28.7 x 20.8 cm., 1911. Collection: DAG

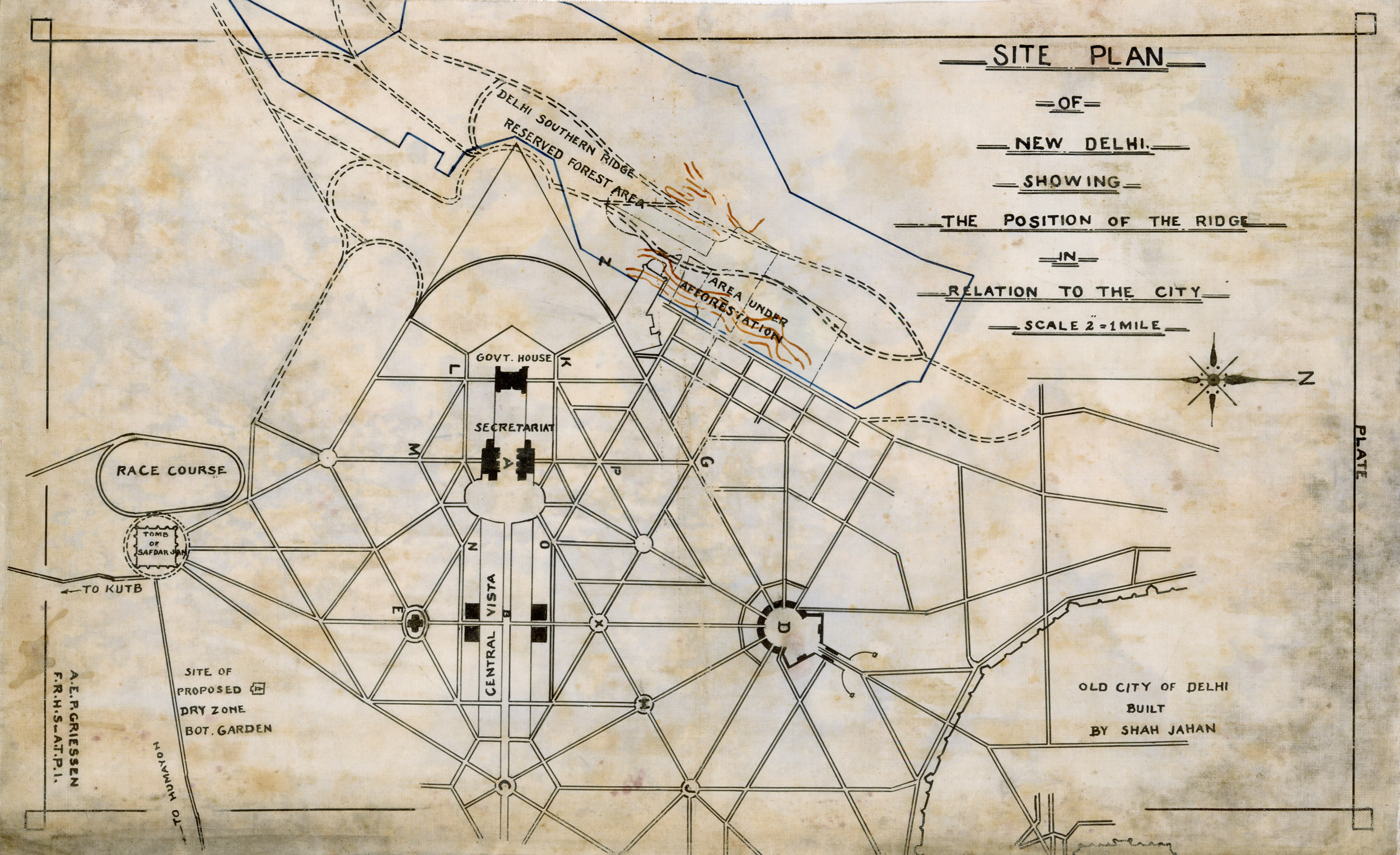

During the construction of New Delhi, the objective was once again to reference older Indian empires. When engaging in discussions with the principal architects, Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, the authorities, including the Viceroy, appointed Jacob as an adviser. His role was to guide them on incorporating more Indian elements into the design of these buildings.

As it turned out, Swinton Jacob, who was already in retirement, found it difficult to collaborate with Lutyens, who was proving to be particularly challenging. Consequently, he resigned from his advisory role rather swiftly. Subsequently, when the design details were revealed, they drew from a broader range of architectural traditions, not limited solely to the Mughals. Elements from places like the Sanchi Stupa were incorporated into the architecture of Delhi, such as the dome added to Government House, reminiscent of the Stupa. While Mughal influences were still prominent, the core concept remained the same: to draw upon Indian traditions because the city being constructed was Delhi, not Calcutta. It was envisioned as an Indian city, distinct from British cities, serving as the capital of India in the 1910s. The message to convey to the Indian people was that this was an Indian city for an Indian Raj.

All of these elements are interconnected. Interestingly, the city's inauguration occurred even before the site had been finalized. Foundation stones were laid northwards of the city where the Durbar was held. The formal ceremony took place with the Emperor and Empress placing the stones on the stage before their departure. This connection between the Durbar layout and the layout plan of New Delhi has been studied extensively. For example, the main avenue linking the amphitheatre to the Viceroy's camp in the Durbar site was named Kingsway. Similarly, the road connecting the Viceroy's house in New Delhi to the amphitheatre, now known as Dhyan Chand Stadium, was also called Kingsway. There are noticeable parallels in the architecture as well, such as the Durbar Hall inside the Viceroy's palace, which mirrors the major ceremonial hall named Durbar Hall. These similarities are evident in the architectural aspects of both settings.

Attributed to Albert Edward Peter Griessen, Site plan of New Delhi. Showing the Position of the Ridge in Relation to the City, Ink on cloth, 20.3 x 34.2 cm., early 20th century. Collection: DAG

Unidentified photographer, Site for the New Capital, Silver gelatin print on paper, 20.3 x 29.2 cm., 1911. Collection: DAG

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025