Technologies of Company Art: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Technologies of Company Art: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Technologies of Company Art: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Technologies of Company Art:

A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

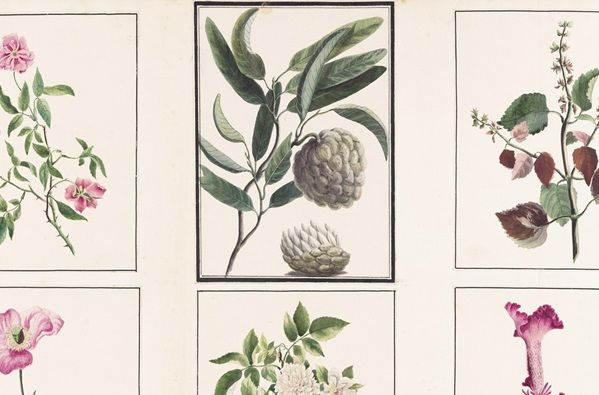

Murshidabad Artist (Company School), China Rose (Rosa chinensis), Custard Apple (Annona squamosa), Patchouli (Pogostemon cablin), Corn Poppy (Papaver rhoeas), Double Musk Rose et. al. (detail), c. 1795. Collection: DAG

In the second part of our conversation with the scholar of ‘Company’ painting, Holly Shaffer, she discusses her concept of ‘graft’ to describe the layered, often uneasy fusion of artistic styles in Company-period art in late eighteenth-century Western India.

She also explores material aspects of Indian painting for the East India Company, especially the use of pigments. She highlights global pigment sources for Indian Yellow and Persian Blue, and talks about her obsession with identifying ‘coconut black,’ a charcoal possibly used by artists like Gangaram Tambat. Conservation efforts have revealed key differences between Indian and European papers and techniques, underscoring how material choices shaped visual outcomes. The edited interview appears below.

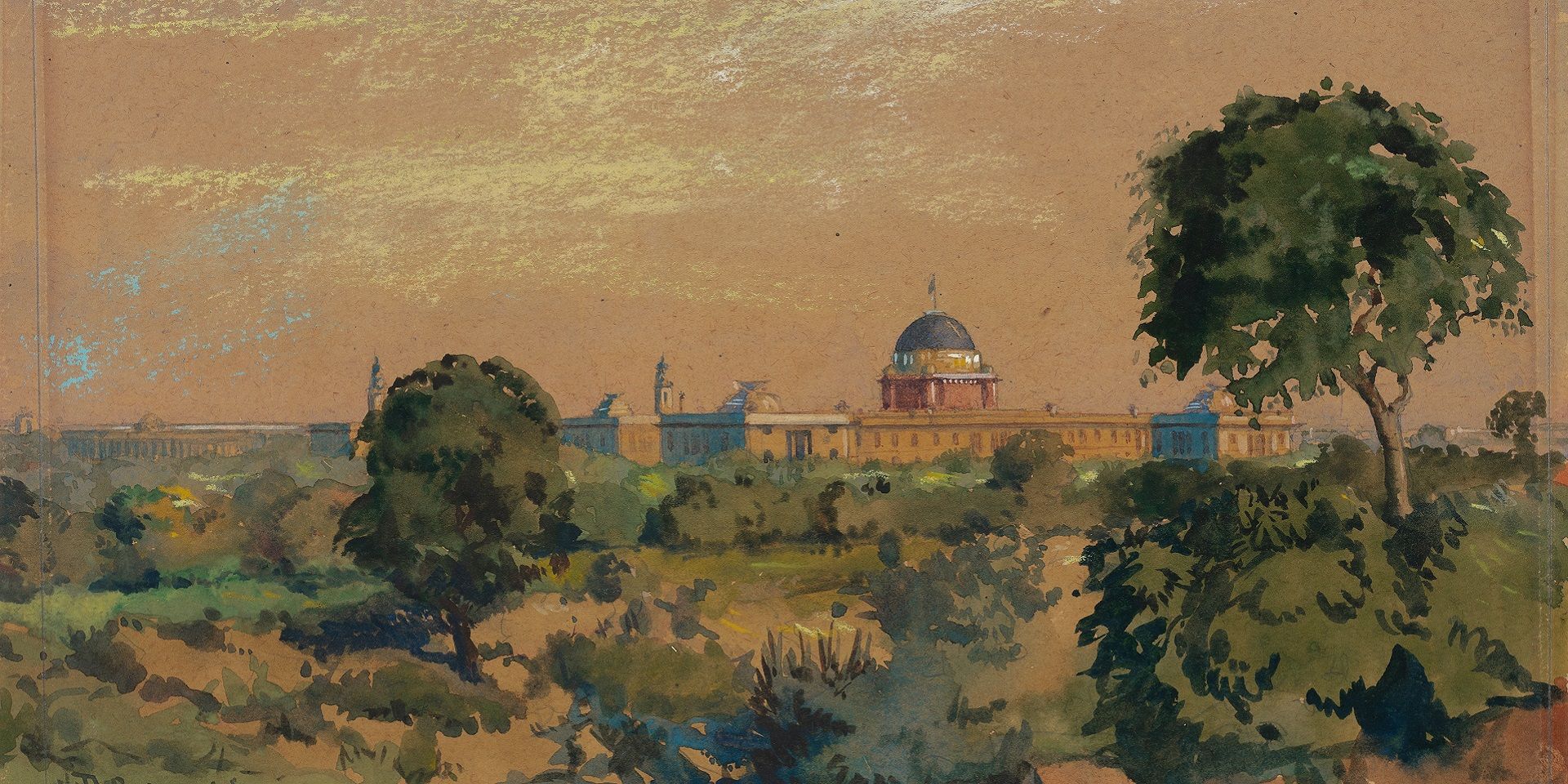

Gangaram Chintaman Tambat, View of Parbati, a Hill near Poona Occupied by Temples Frequented by the Peshwa, Watercolor and graphite on medium, slightly textured, cream laid paper, 1795, 10.9 x 16.7 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Common and the Yale Centre for British Art

Q. The concept of ‘graft’ is a term that can accommodate multiple artistic operations and socio-political moves that were occurring at the time, including connotations of imposition, conquest, corruption and organic, or even surgical, transplants. Could you explain how you are using the concept to understand Indian and Company art in Western India?

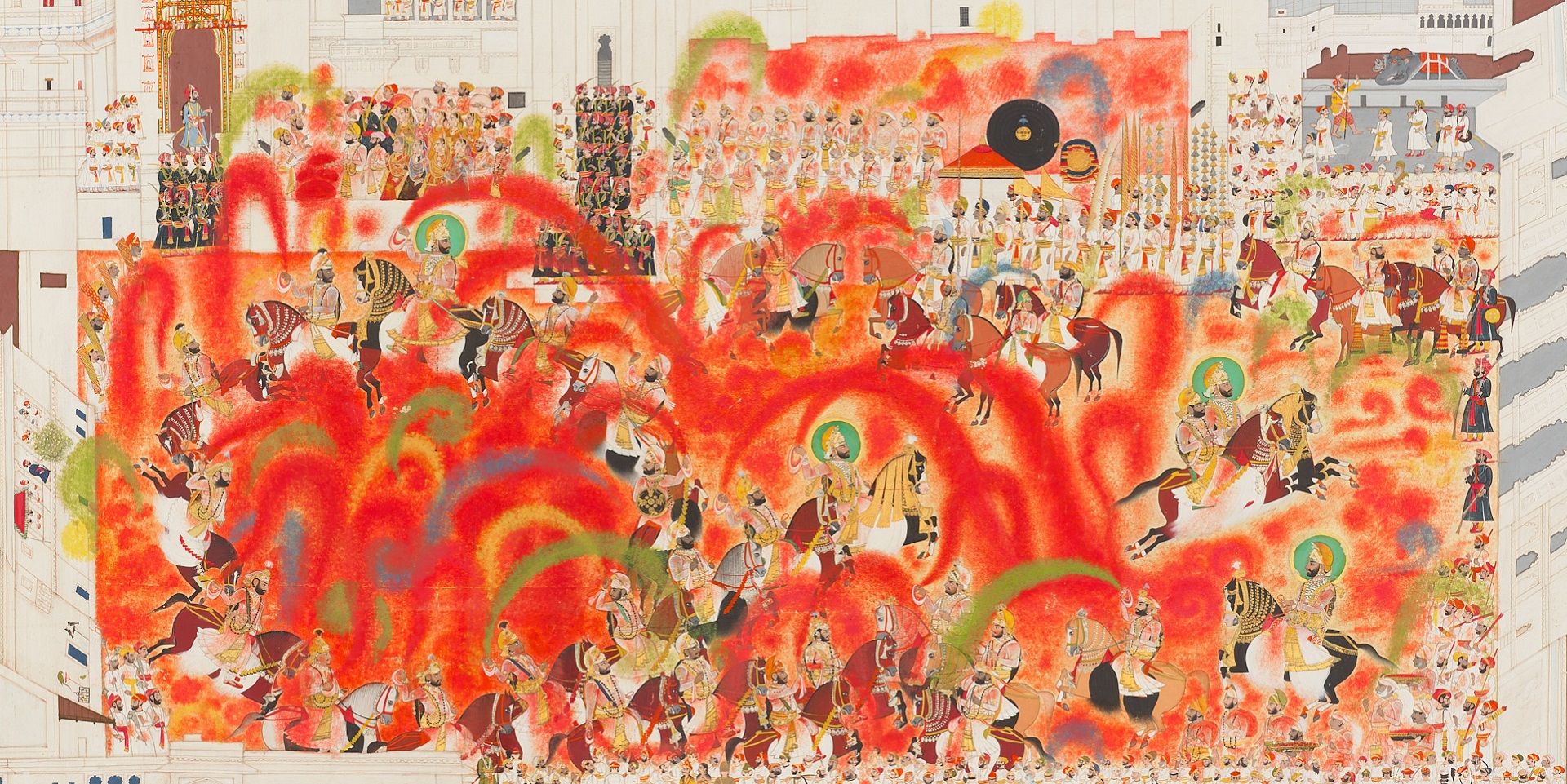

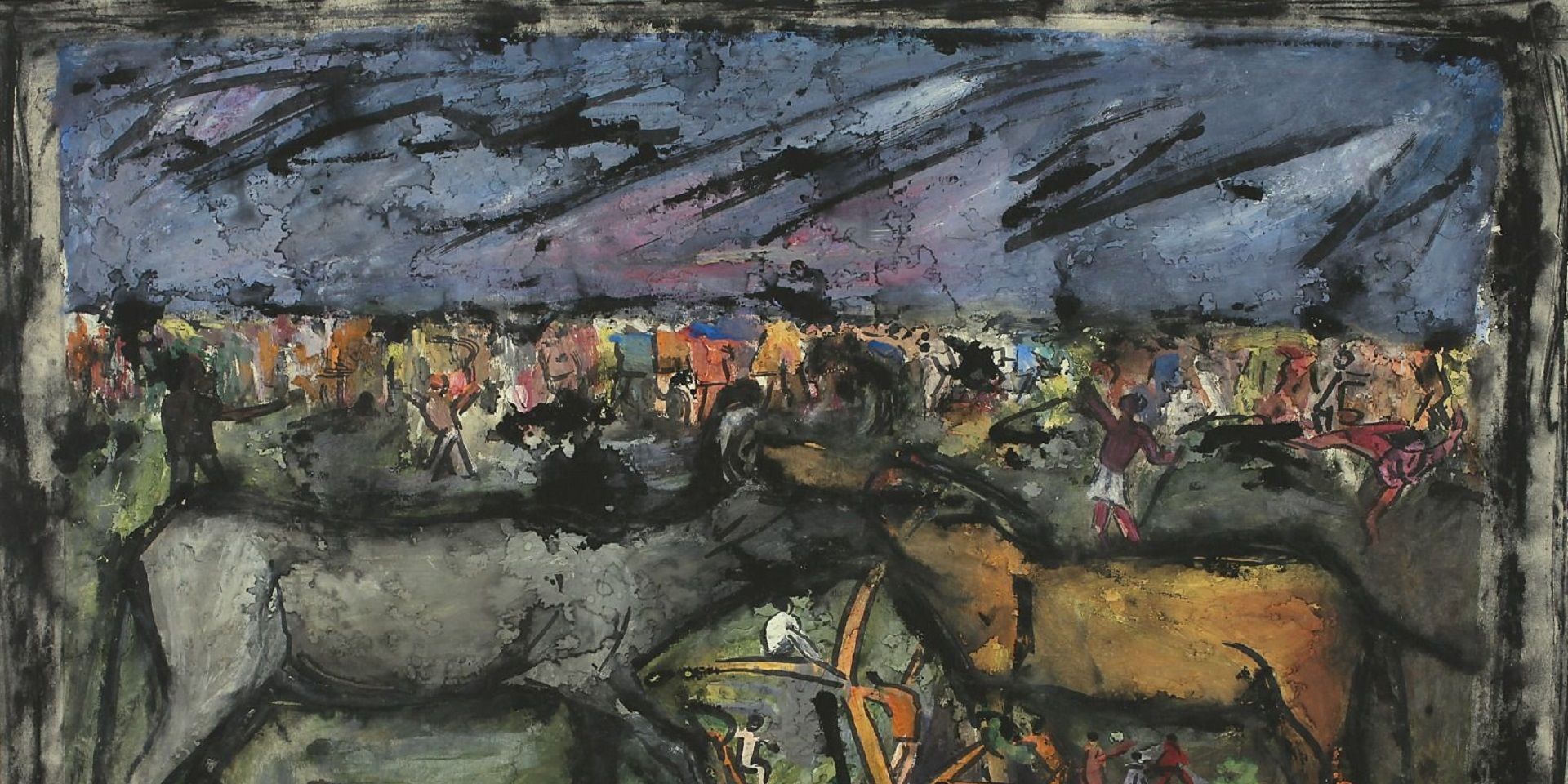

Holly Shaffer: One of the most important aspects of Company art, I think, is its hybridity—or what I have recently started calling grafted art. I use this term not to dismiss others like ‘hybrid’ or ‘mixed’, which are also useful, but because graft helps capture the layered, sometimes messy, and often violent nature of these artistic combinations. The style of Company-period art often depended on who commissioned the work or whether it was intended for a broader market. Take the Daniells, for example—their visual language was deliberately constructed and heavily influenced by optical technologies. Their compositions often feature strong diagonals and a controlled framing of the scene, likely derived from tools like the camera obscura. This reflects a broader trend in Company art: artists adapting methods to meet market demand, which often meant producing work faster and relying on techniques of reproduction.

Thomas and William Daniell, View on the Chitpore Road, Calcutta, Hand-tinted engraving on paper, 1797, 16.7 x 23.7 in. Collection: DAG

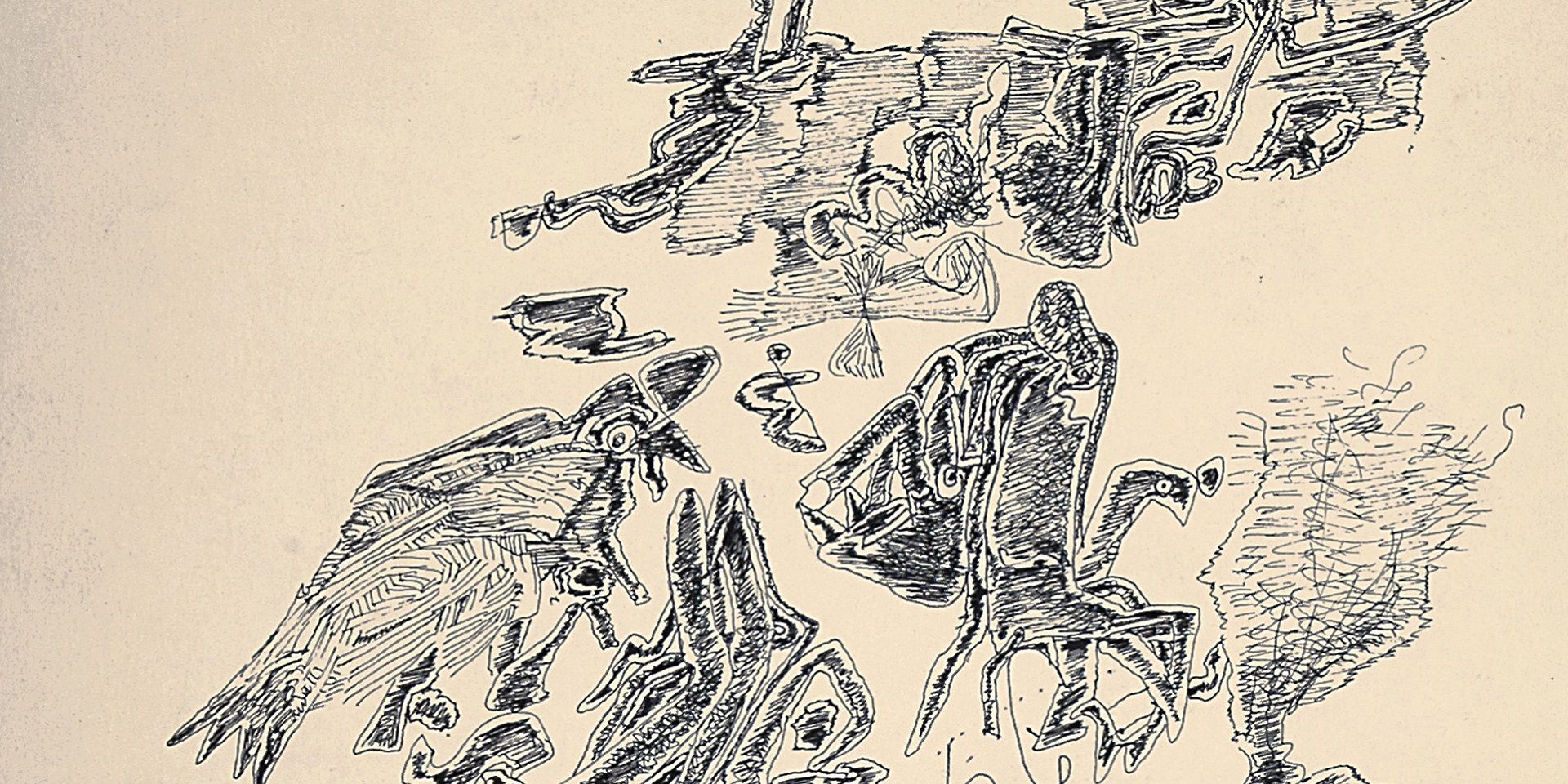

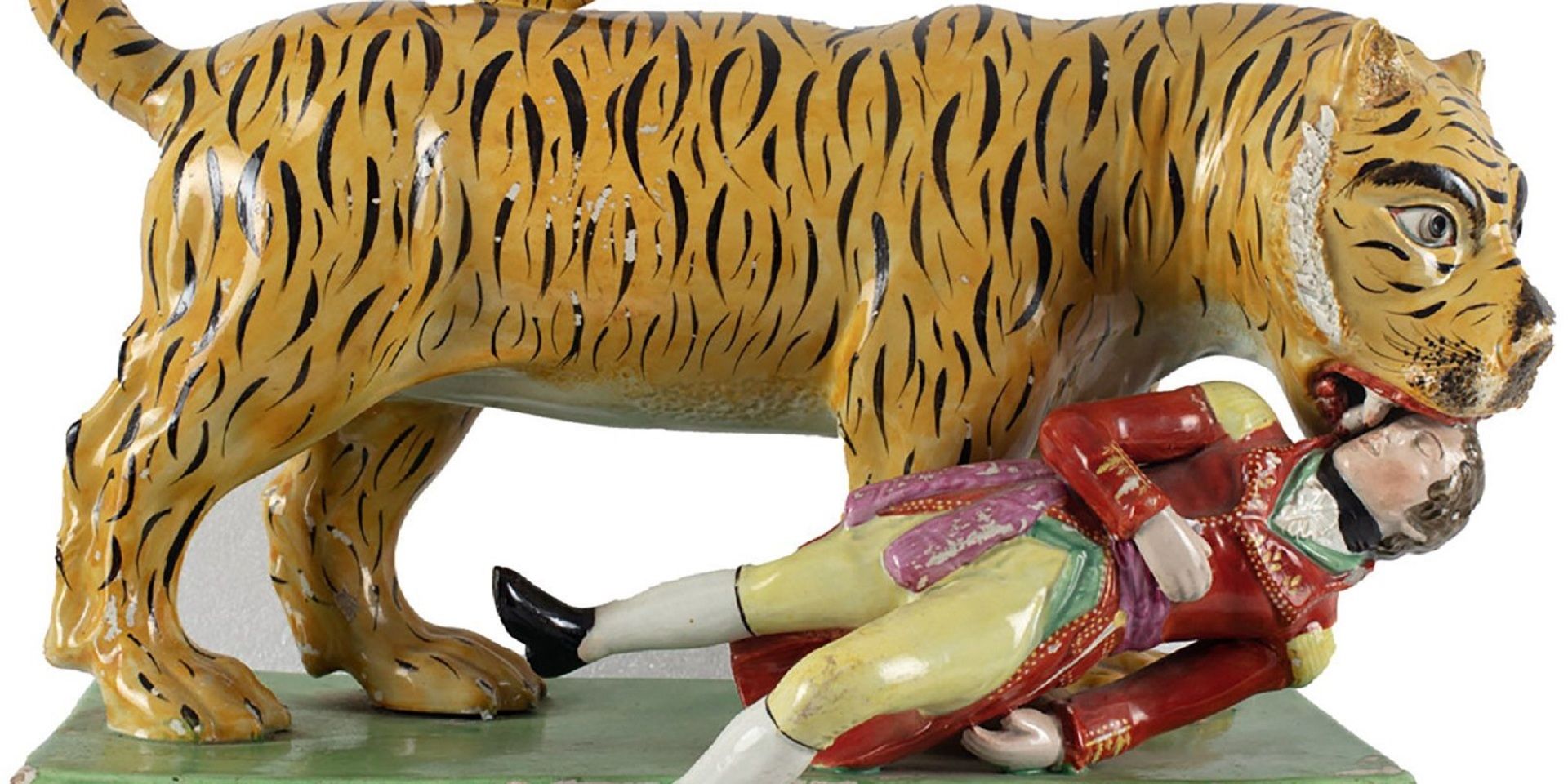

James Forbes is a fascinating figure in this context—deeply engaged with Mughal and Chinese art, he not only studied them but incorporated their aesthetics into his work. James Wales went further, openly copying Mughal paintings. These kinds of stylistic fusions were not always seamless. Sometimes the blend was elegant, but at other times, it felt rough or ‘grafted’—a term I have come to use for these moments when styles collide more visibly, even awkwardly. This metaphor comes partly from botany, but also from the word’s use by military artist Robert Mabon, who documented a remarkable case of early plastic surgery among the Marathas and used the term ‘graft’ to describe it.

In the context of late eighteenth-century Western India—a time marked by intense military conflict involving both the Marathas and the British—you see artworks that bear the marks of that violence. The visual seams, so to speak, are exposed: prints overpainted, perspectives forcibly combined, traditions abruptly layered over each other. These artworks reveal not only artistic innovation but also the fractured, often violent circumstances in which they were produced. Company paintings, especially from this region and period, are therefore best understood as the product of both creativity and coercion. While some later images become more polished or sanitised, we should not lose sight of the fact that these works were born within—and often reflect—the brutal realities of a colonial, profit-driven enterprise.

|

James Forbes, The Curmoor or the Florican, Etching and aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 1781, 11.0 × 5.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. I have been especially curious about the black pigments used during the Company period because they often have a distinctive, lustrous quality. As an artist, I am really interested in understanding more about the materials used at that time—not just the blacks, but also pigments like Persian blue. When I examined some works under light, I noticed incredibly fine surface cracks in the blue—tiny, almost imperceptible fractures—which made me wonder about the composition and aging of the pigment. I would love to hear any insights you might have about these material qualities and what they can tell us about the techniques and choices of Company-period artists.

Holly: It’s a great question—and there’s still so much more to uncover on this front. As part of the upcoming exhibition at the Y. C. B. A. (opening January 8, 2026), we have undertaken extensive conservation work on objects in their collection. This process has been fascinating in two major ways.

|

Whatman Drawing Board. Issued by Reeves & Sons ltd London, England. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

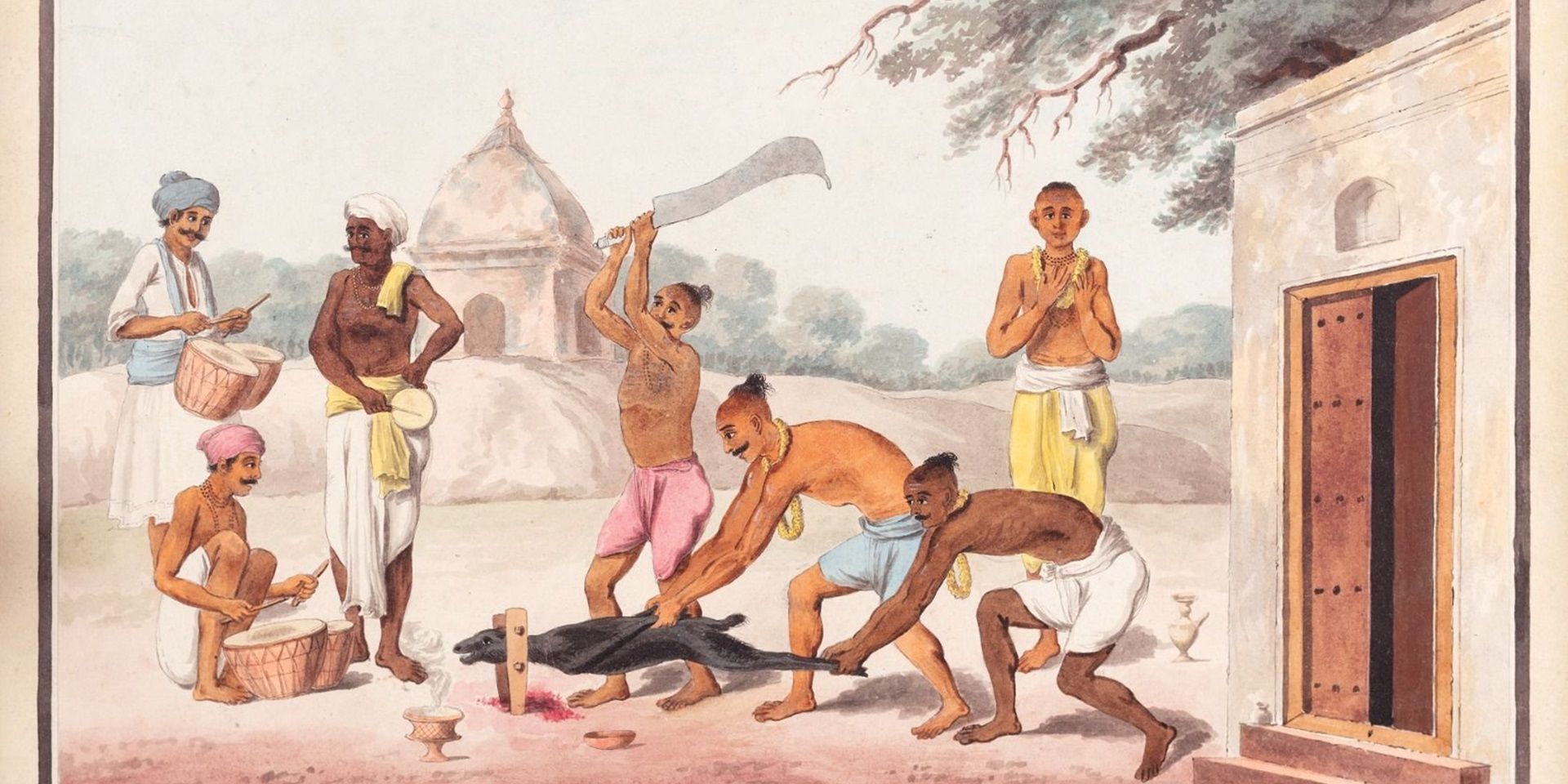

First, it has highlighted how global the pigment sources were. We focused on Indian Yellow (Purree or Piuri), which can be identified through simple, non-invasive U. V. light testing. Many Indian artists used it in small amounts to create highlights or to intensify gold. We also found use of Vermilion from China and Persian Blue—pigments that can help date works.

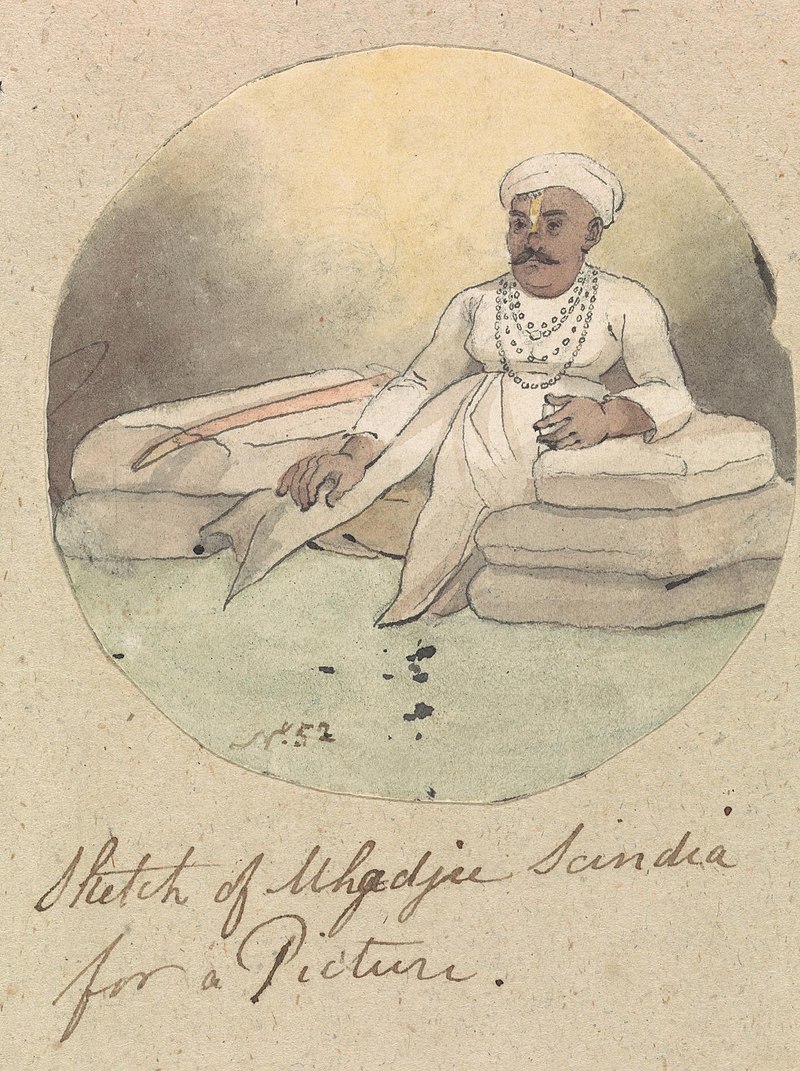

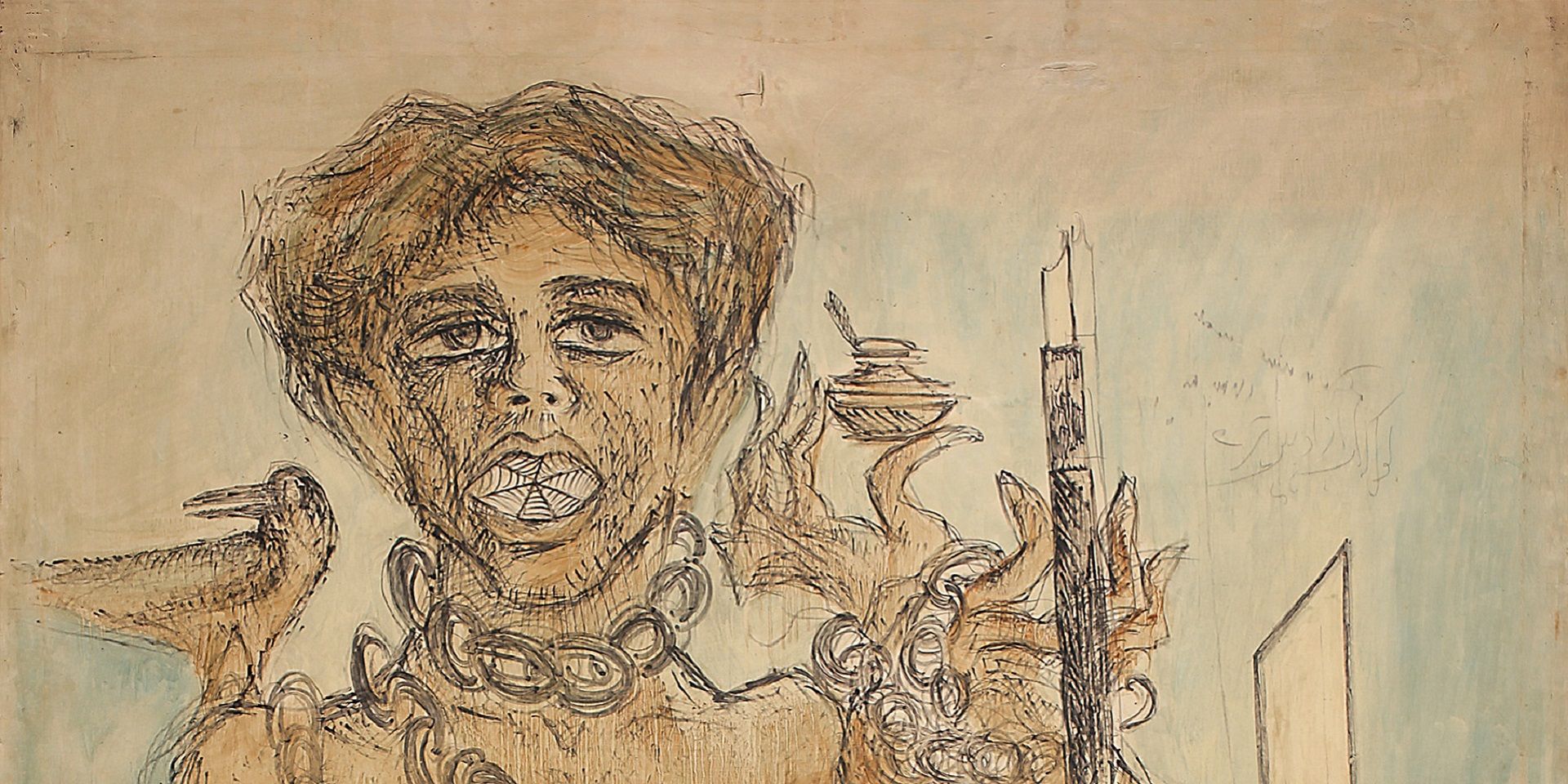

Your question about black confronts a real mystery—and it is one of my personal bugbears. James Wales mentions ‘coconut black,’ likely a charcoal made by burning coconut shells. It has a distinctive quality, but conservation scientists have found it difficult to distinguish chemically from other charcoals. Unlike Indian Yellow or lead whites, blacks lack a unique chemical signature, making them hard to trace. I have become obsessed with this pigment—especially when looking at works by Gangaram Tambat and later Robert Mabon, who used intense blacks in depicting rock-cut architecture. It is possible they were using leftover pigment from earlier projects, and I suspect it might be coconut black. But without clearer testing methods, it remains unresolved.

|

Robert Mabon, Mahadji Sindia, Watercolor and graphite with pen and black ink on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 4.8 x 3.7 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons and Yale Centre for British Art |

James Wales likely came to India through his connection with James Forbes. Both were Scottish and knew each other when Forbes returned to Britain. At some point, Forbes commissioned Wales to turn his Indian watercolours into grander oil paintings. One particularly significant work by Wales—probably based on one of Forbes’ original sketches—was later translated into a print. This painting illustrates how Company officials, like Forbes, sought to elevate their artistic efforts through collaboration with academically trained painters. It also shows how such collaborations encouraged artists like Wales to travel to India and develop entire careers there.

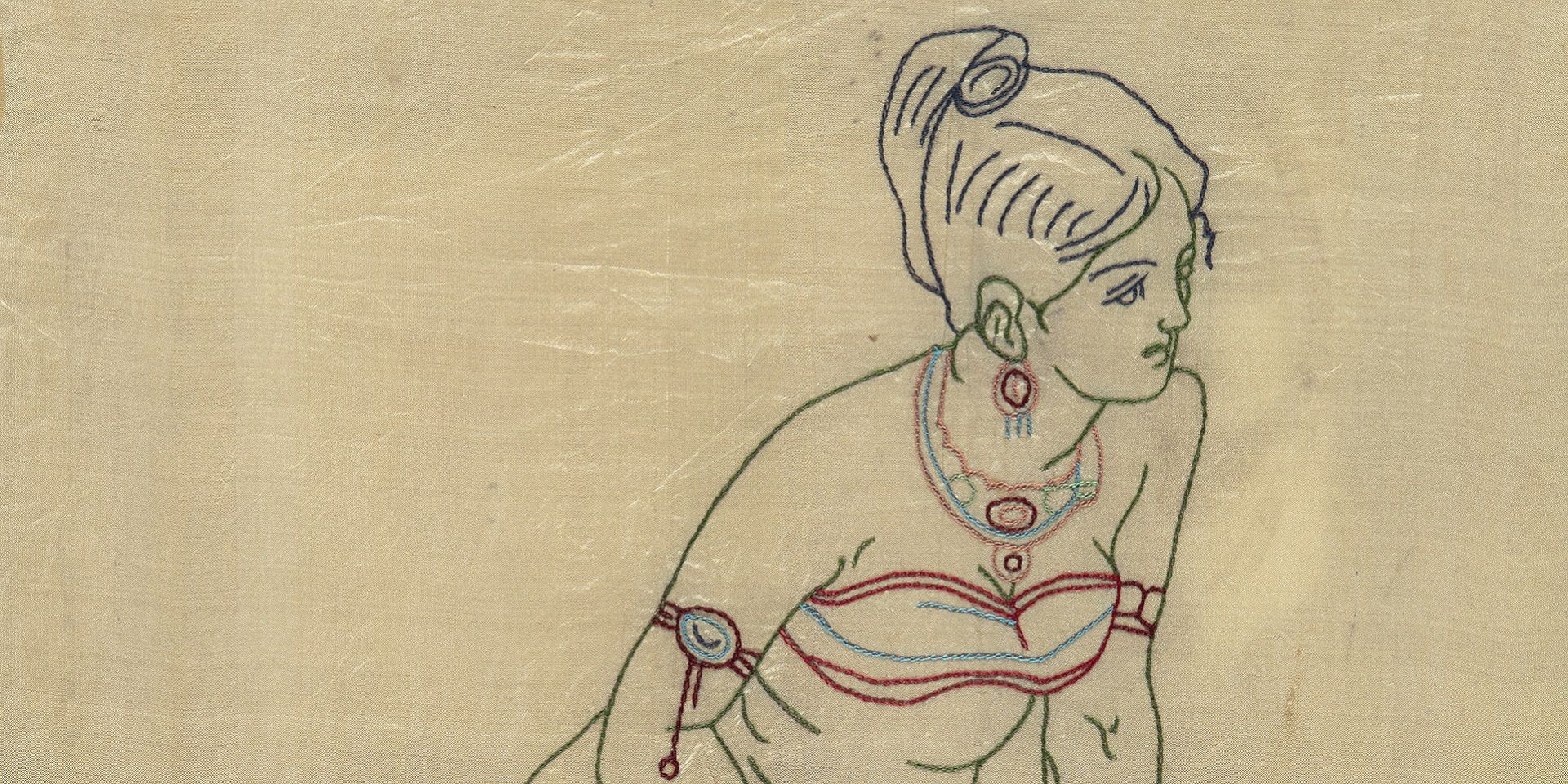

While the pigments used in that painting were probably European or processed in Britain, it is important to remember that high-quality pigments have always circulated globally. The larger point, though, is how materials and techniques changed depending on the paper and context. Indian artists used burnished wasli paper with dense pigments and minimal water, creating richly layered surfaces. In contrast, British artists worked on absorbent Whatman paper with diluted pigments, leading to softer, less saturated results. These technical differences profoundly shaped the look and feel of Company-period works. Interestingly, as Indian artists adopted European papers, they adapted their methods, resulting in hybrid techniques that varied depending on the materials used.

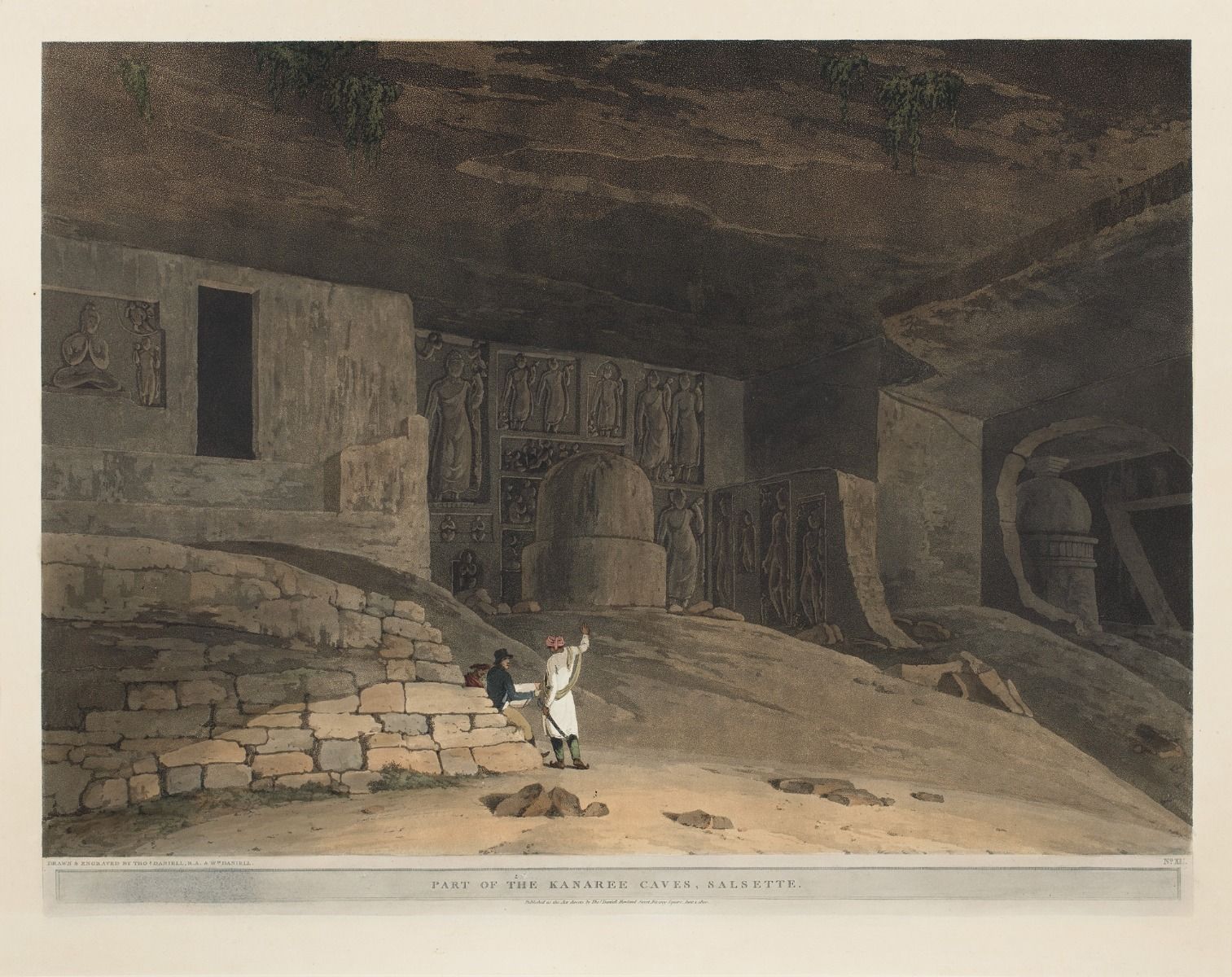

Thomas and William Daniell, Part of the Kanaree Caves, Salsette, Engraving, 1800, 18.2 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

This is the interior of Cave 2 at Kanheri. The European figure shown sketching is James Wales, who accompanied the Daniells on their visit to the caves in 1793. Two years later, on a subsequent visit, Wales caught a fever in the Kanheri caves and died.

This fluidity challenges the term ‘opaque watercolour’—a label that does not fully capture the complexity of these techniques. Depending on the nature of the binder—whether oil or water—the density of the pigment varies. I tend to say watercolour washes and then opaque application of paint. So, we are using the same terms—opaque watercolour and watercolour. What is really at stake is the interaction between pigment, water, and surface, and the shifts that occurred as artists negotiated new materials and aesthetic expectations across cultural and economic boundaries, along with the time they had available to work on each painting.

All this makes me even more eager for collaborative research across collections—especially to better understand the varied and locally sourced blacks that artists were using. After all, black can be made from burning almost anything.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

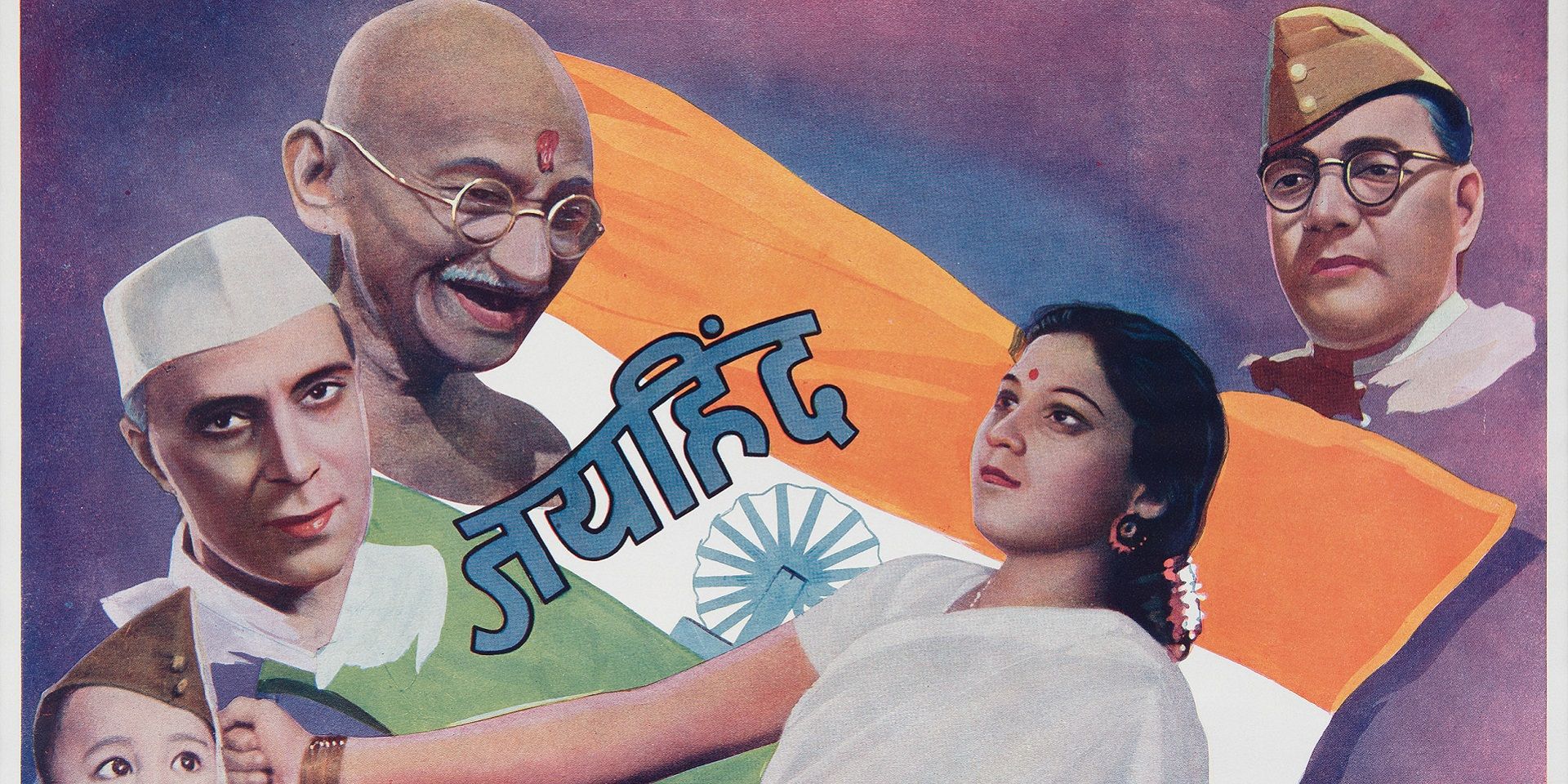

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

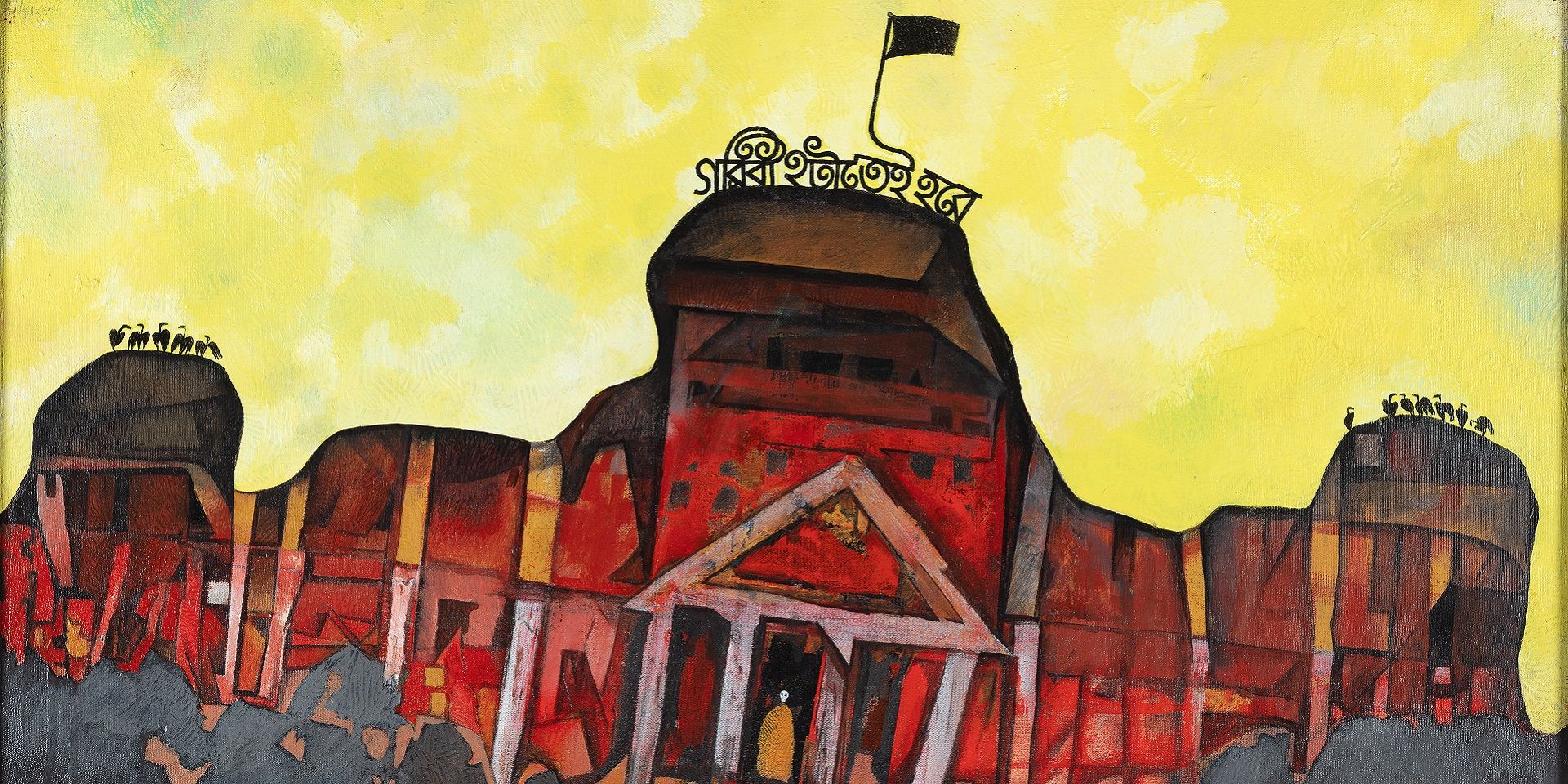

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

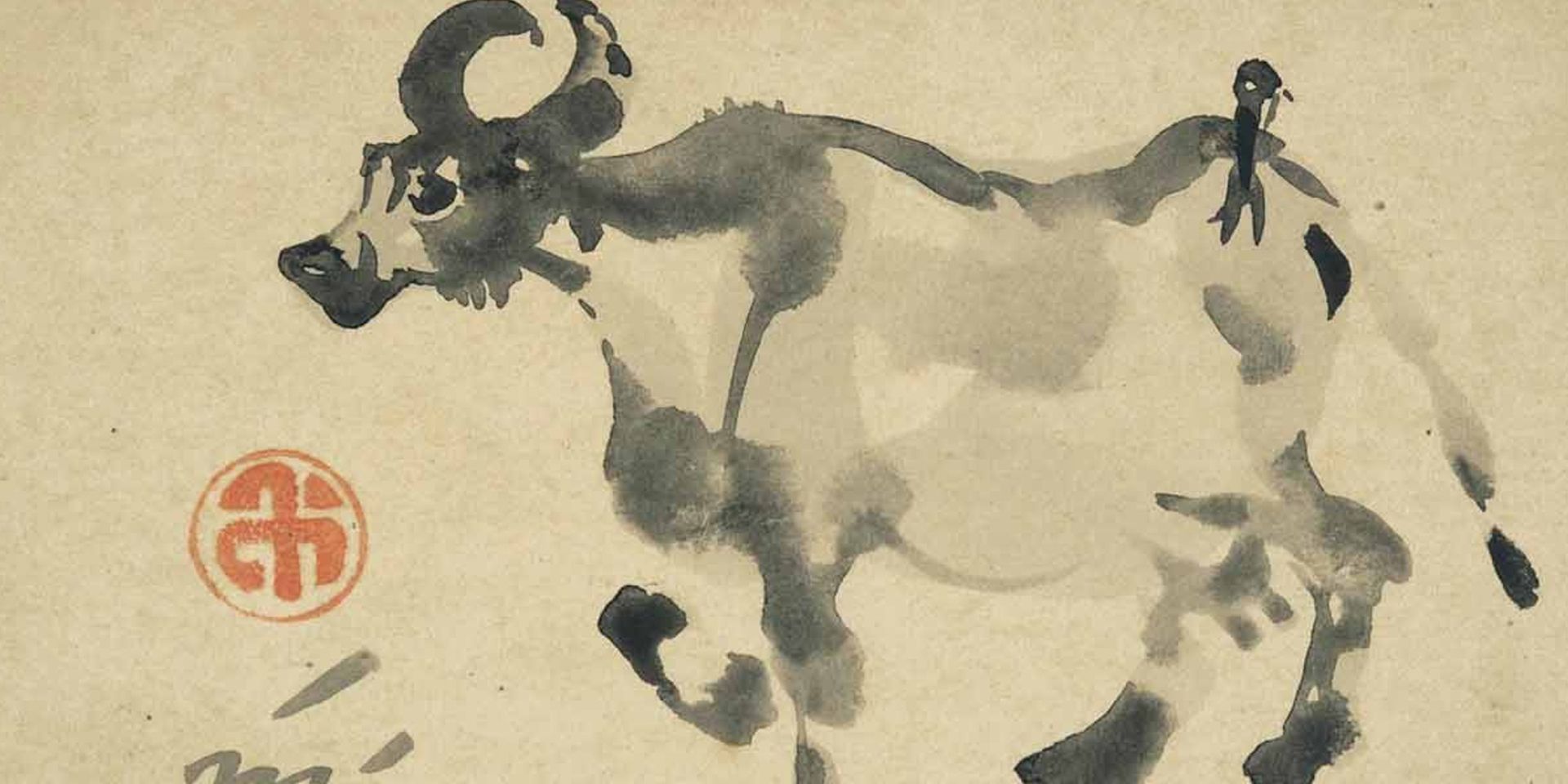

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025