Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Mithu Sen, MOU, Museum of Unbelongings, 2012, fabric and found objects, site-specific installation, dimensions variable. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

What is the role of collectors and collections or archives in the world of art today? Does it simply allude to practices of producing a consumable past today or does it also aspire to question the ways in which history has been shaped by powerful interventions in the form of artworks, performances and installations? In this series of conversations, we wanted to explore the idea of collecting recent or contemporary art—and how it inevitably takes us back to the moderns who influenced such practices heavily.

We spoke with Sneha Ragavan from the Asia Art Archive, an institution that creates archives and collections of recent art from South and Southeast Asia with a historical lens in place, and Durjoy Rahman, who founded the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation. They gave us a sense of how collections are determined by their complex geographies of operation and location, personal and public motivations around collecting and the question of protecting sensitive archives while remaining aware of gaps in any collection.

A glimpse of Asia Art Archive’s Hong Kong offices. Image: Omnispace, The Notion Album, 2022, video, handmade books; ba-bau AIR, Building a VIVA ExCON, 2022, wooden blocks. Part of The Collective School, AAA Library, 2022. Photo: South Ho

Q. What are some of the challenges around collecting contemporary or recent art, and what mechanisms does Asia Art Archive have in place for recognising what to collect?

Sneha Ragavan: The work of collecting or building an archive is rather different from collecting artwork itself. And so, building archival collections around contemporary art, or contemporary practitioners, typically requires—at least of the art historical kind that we are involved with—some amount of distance. [This is] for a couple of reasons: one, in order for us to be able to frame it historically; but two, also so that they feel more comfortable giving us access to this material that they are not working with on a daily basis. And third, so that they are also able to retrospectively look back at something they’ve done, that they’ve probably distanced themselves from, that they have perhaps moved on from.

Typically for an archival collection that institutions like us undertake, we prefer that historical distance, be it in terms of five years or ten years or whatever that gap is, we prefer that that exist because then it enables us to not just put the material out there but to also appropriately, responsibly and accurately frame it and put it out there.

At AAA, we have what are called ‘content priorities’. While our collection practices initially started off rather arbitrarily in some sense, based on the researcher’s own interest, over a period of time we decided as an organisation, to take stock of what is it that we’ve been collecting so far. Whose archives have we been digitising? What are the gaps, what are the blindspots? And what are also the directions that we as an institution would like to focus on? And so, we developed a set of content priorities. Some of these content priorities include pedagogy, art writing, exhibition histories, women in art, performance art, and so on. So it’s often a combination of figuring out whether a collection that we may be considering fits within one of these content priorities. The second is also the researcher's own interest and initiative. And all of us come with different areas of research interest and so to some extent it is also driven by that. And the third of course being the availability of such material.

|

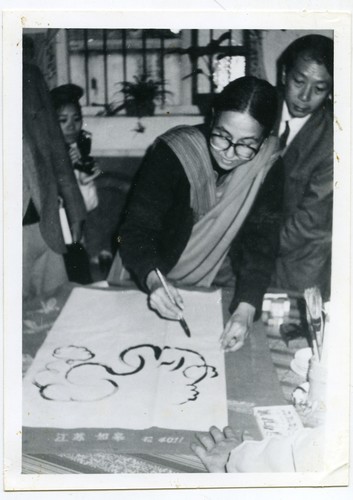

Photograph of Nilima Sheikh on Visit to China, 1990. Image courtesy: Nilima Sheikh and Asia Art Archive |

Q. How do you balance your ethical mission to increase accessibility to contemporary and modern art archives with the need to protect intellectual property or sensitive information arising out of new works and political contexts? For instance, what are the challenges or ethical issues present in the process of collecting personal material for public archives?

Sneha: To give you an example, when we often digitise the personal archive of an artist, there’s a wide range of material that they make accessible. This ranges from artwork documentation to photographs of their peers, photographs of the art community, of exhibition views, of places they have travelled to etc. Then you also often have correspondence, you have exhibition catalogues that they’ve collected, if they are writers then you have writings about them, writings by them. And then of course you have diaries and sketchbooks and so on and so forth. To make things accessible does not simply mean just putting everything online. At AAA we have three levels of access -- one is online, one is on-site, and the third is restricted.

So, just to give you two quick examples, in the case of correspondence in most cases we do not put correspondence online. Not simply because correspondence often blurs the boundary between personal and professional but because correspondence is a two-way rights process--there’s the sender [and] there’s the receiver. So typically, as an organisation our position is that correspondence should not be put online.

To some extent, there’s a huge debate today about how despite providing access there’s a lot of gatekeeping that archives do. And I think that given that we are custodians of the materials that a lot of figures have given to us to handle with responsibility, we feel it is important for us to put in place some of these mechanisms to ensure that this is not misused. We negotiate this in multiple ways for different kinds of materials.

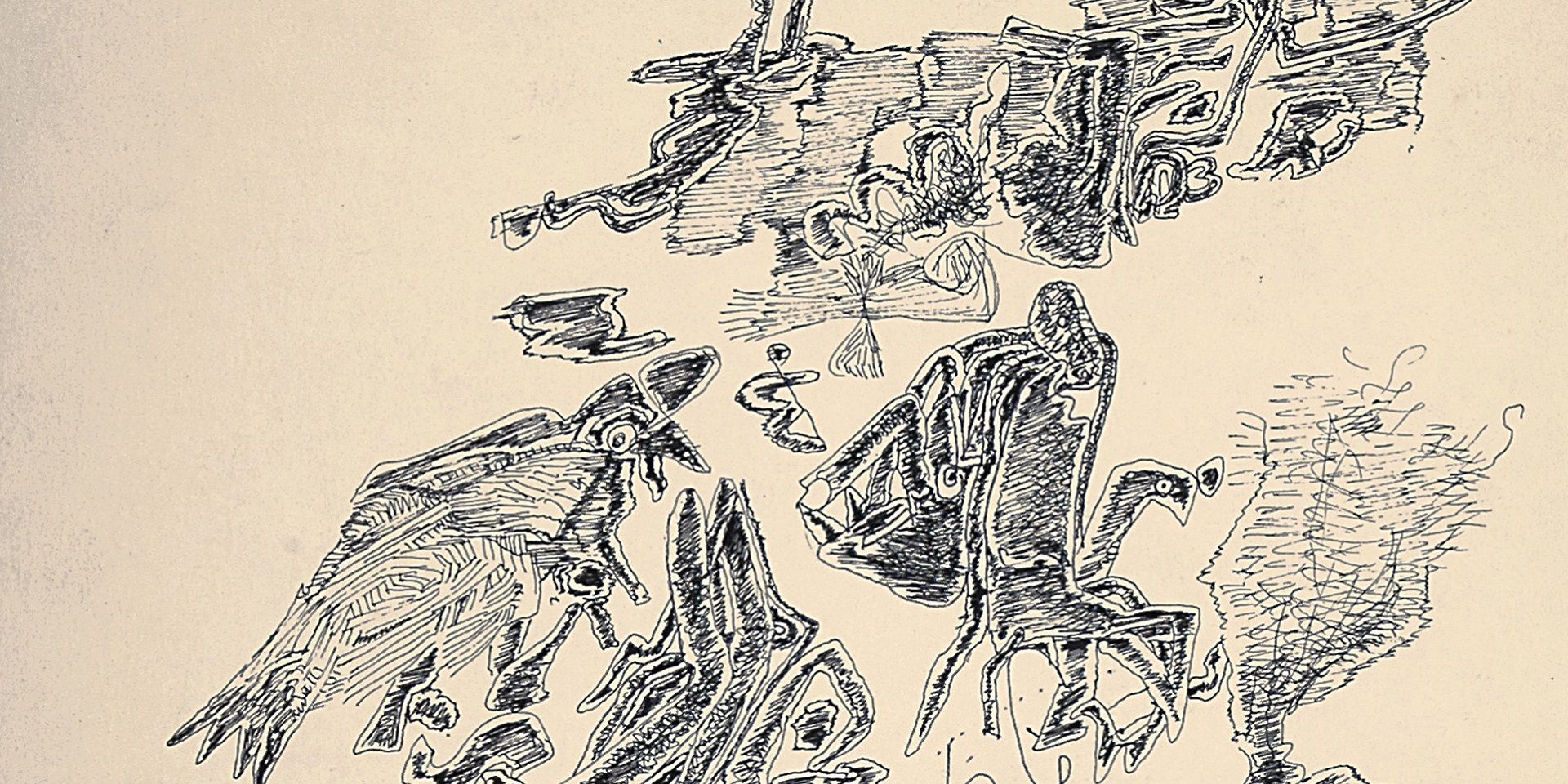

Nilima Sheikh, Stencils: Birds and Animals 1 (Set of 43 Photos). Image courtesy: Nilima Sheikh and Asia Art Archive

Nilima Sheikh, Stencils: Birds and Animals 1 (Set of 43 Photos). Image courtesy: Nilima Sheikh and Asia Art Archive

Q. How did you go about collecting or putting specific archives together, such as the Nilima Sheikh or the Salima Hashmi archives? I also find the Lee Wen archive very interesting, because of course he pioneered performance art in South-East Asia, and I’m also curious about how collecting practices differ when it is a performance artist’s archive.

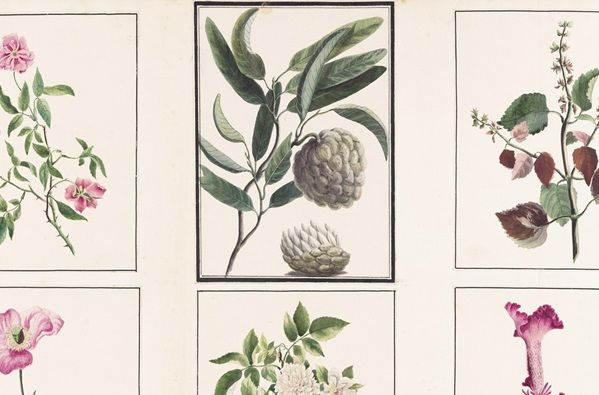

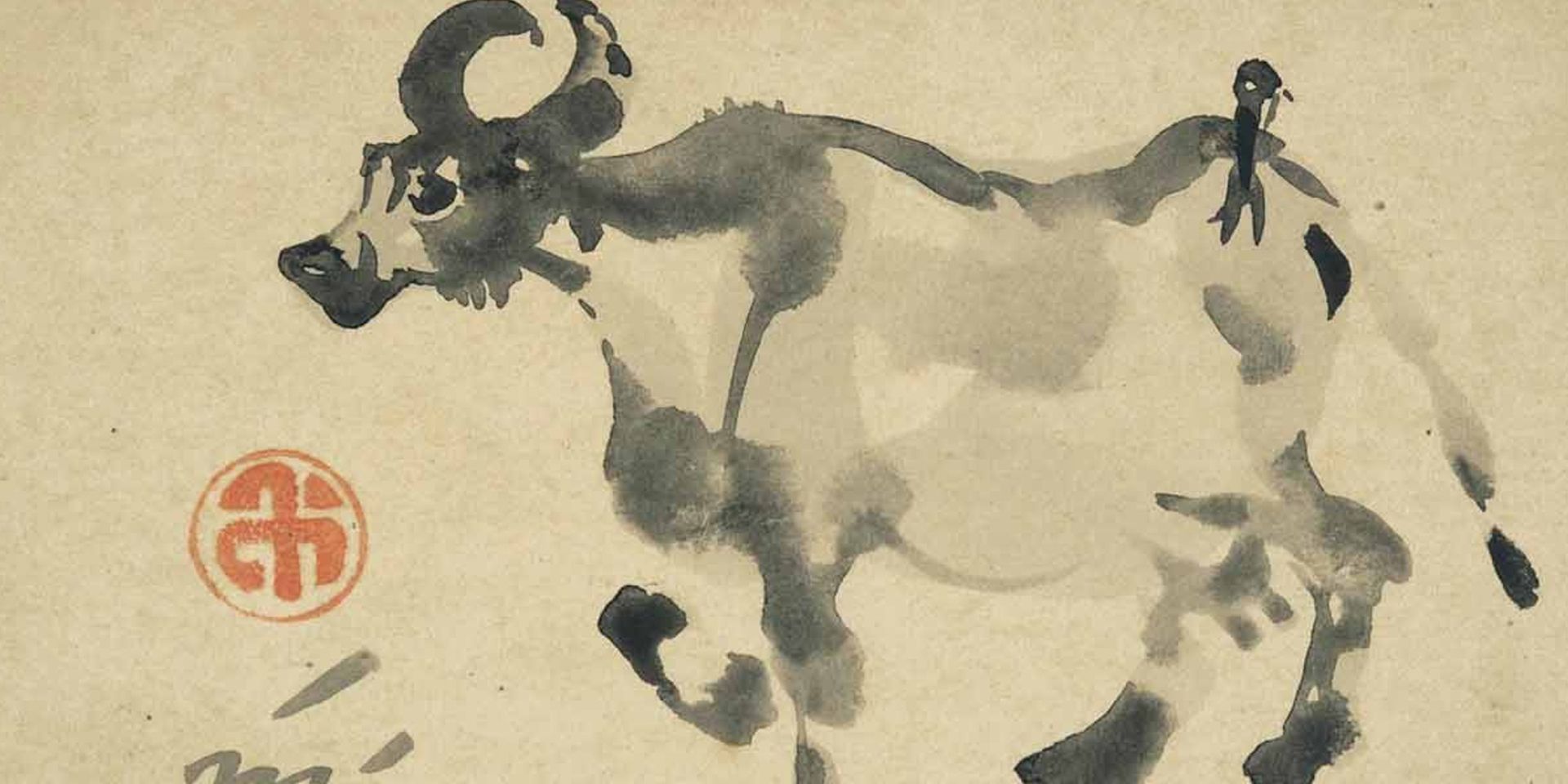

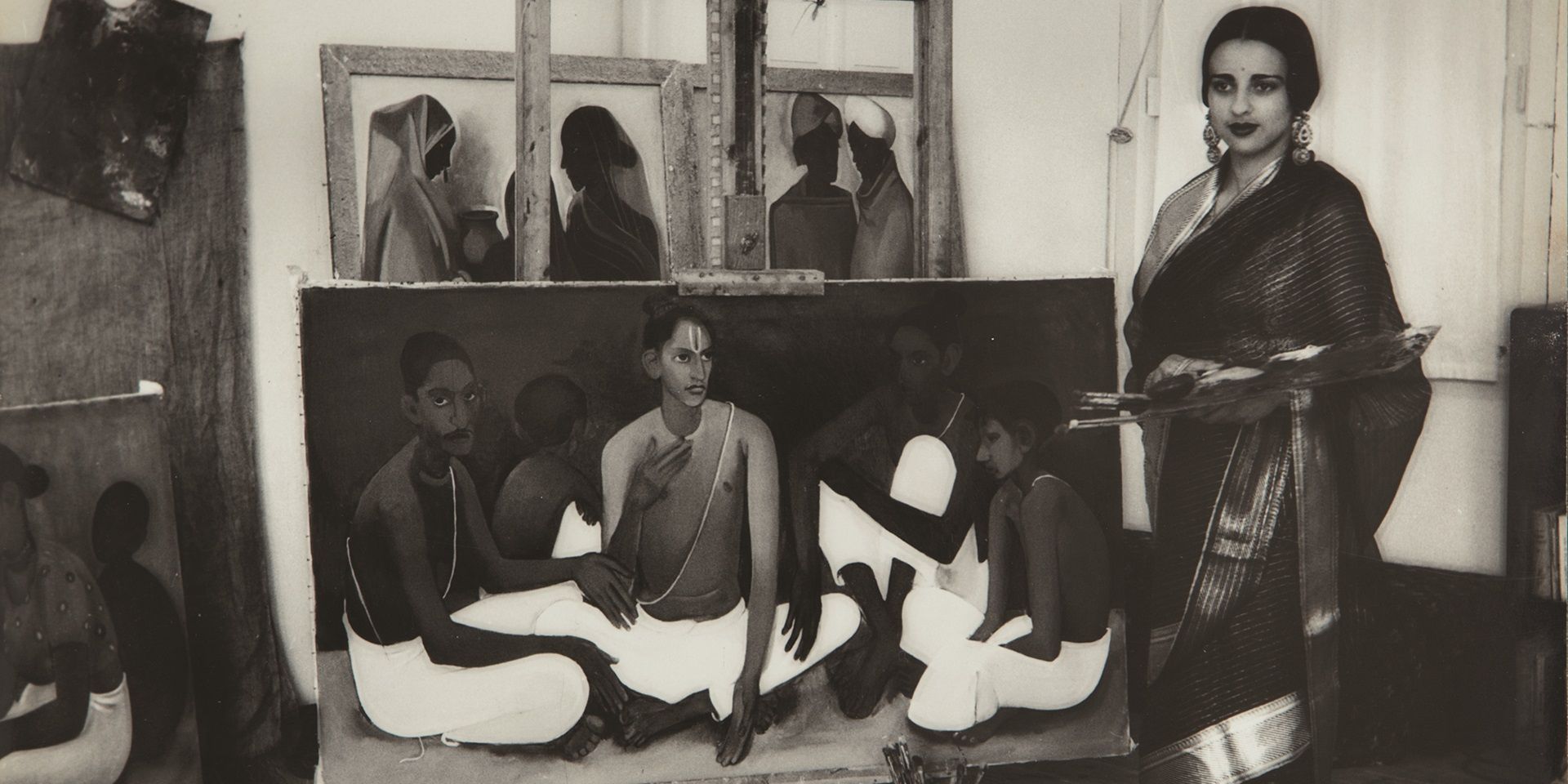

Sneha: In the context of Nilima Sheikh, there was an interest in examining archives of women practitioners in the context of our work in India particularly. Other than Geeta Kapur, whose archive we had digitised, I think we hadn’t really looked at any women artists. Right after we finished Geeta and Vivan [Sundaram]’s archive, we also began to see traces there of the presence of a lot of artists from Baroda. Baroda being such an important place in the history of not just Indian art but also the role of the school in developing curriculum for art education—we had worked on the archives of four artist educators in Baroda. [Also], Nilima Sheikh’s artistic practice itself seemed to have some archival impetus within it. This is something we had noticed, for instance, through the extensive citation that she has in her artwork, as well as in her use of stencils. I had chanced upon one of her studio assistants actually preparing some of these stencils, and in conversation I realised that she actually has a large collection of these stencils that she uses in her own artistic practice—not just that she has a collection of stencils but that these are categorised and organised in a way that she finds useful for her own practice. Secondly, these stencils derive from a lot of art historical references. This is ranging from Turkish manuscript painting, to Pahari painting, to Pahari miniature, to Mughal painting, to Chinese and Japanese scroll paintings, and so on. And then all of these visual references were also organised and classified and kept within her studio.

One of the most exciting things for us at archives often is also to not just bring something in and then reorganise it as we see fit, but also try and see how artists themselves have organised it. And typically when artists organise archives, they do it keeping in mind how they would like to retrieve these materials. In the case of Nilima Sheikh, she organised her references and her stencils—her visual references, her textual references, her stencils—based on how she would use them and reuse them for her practice. So for us it was also sort of an experiment, an opportunity really, to try and unearth the archival impetus within an artist’s own practice.

In the context of Salima Hashmi, it was pretty similar in that sense. Of course, foregrounding her role as a writer, as an art educator, but also as somebody who ran an exhibition venue, The Rohtas Gallery. It was about collecting ephemera and photographs and all kinds of material around diverse aspects of her practice, including material relating to her teaching, her own writing, and then her organisational work as an artist.

As for Lee Wen, of course, I think one of reasons why performance art became a research or content priority at AAA actually stemmed from the very specific place of performance art within South-East Asia itself, where it is extremely politically charged. In most of the countries it is, if not outright banned, under a great deal of State and police scrutiny. And Lee Wen is an artist of importance for so many reasons other than this as well.

As to the challenges specifically of engaging with performance art, it’s one of those forms where documentation is the only remnant in the archive in a sense. The more exciting question is then that, other than the document, what else can the archive of performance art carry? This was actually something that we had attempted to experiment with. And several years back we had invited a scholar on performance art—in the context of India—Samudra Kajal Saikia, to try and explore this process of what it means to build an archive not just through the documentation of a performance, but other kinds of materials. He had developed a very interesting framework which included everything from testimonies of people who happened to see it, contextual material around a performance that the organiser may have or that the artist themselves may have, which range from everything from email or letter exchanges to discussions of a performance, props or materials that people may have kept and carried with them, preparatory drawings or sketches, or preparatory movements, exercises or documents relating to that. And also anecdotal references—testimonies not just of people who have had a chance to see it but also of people around.

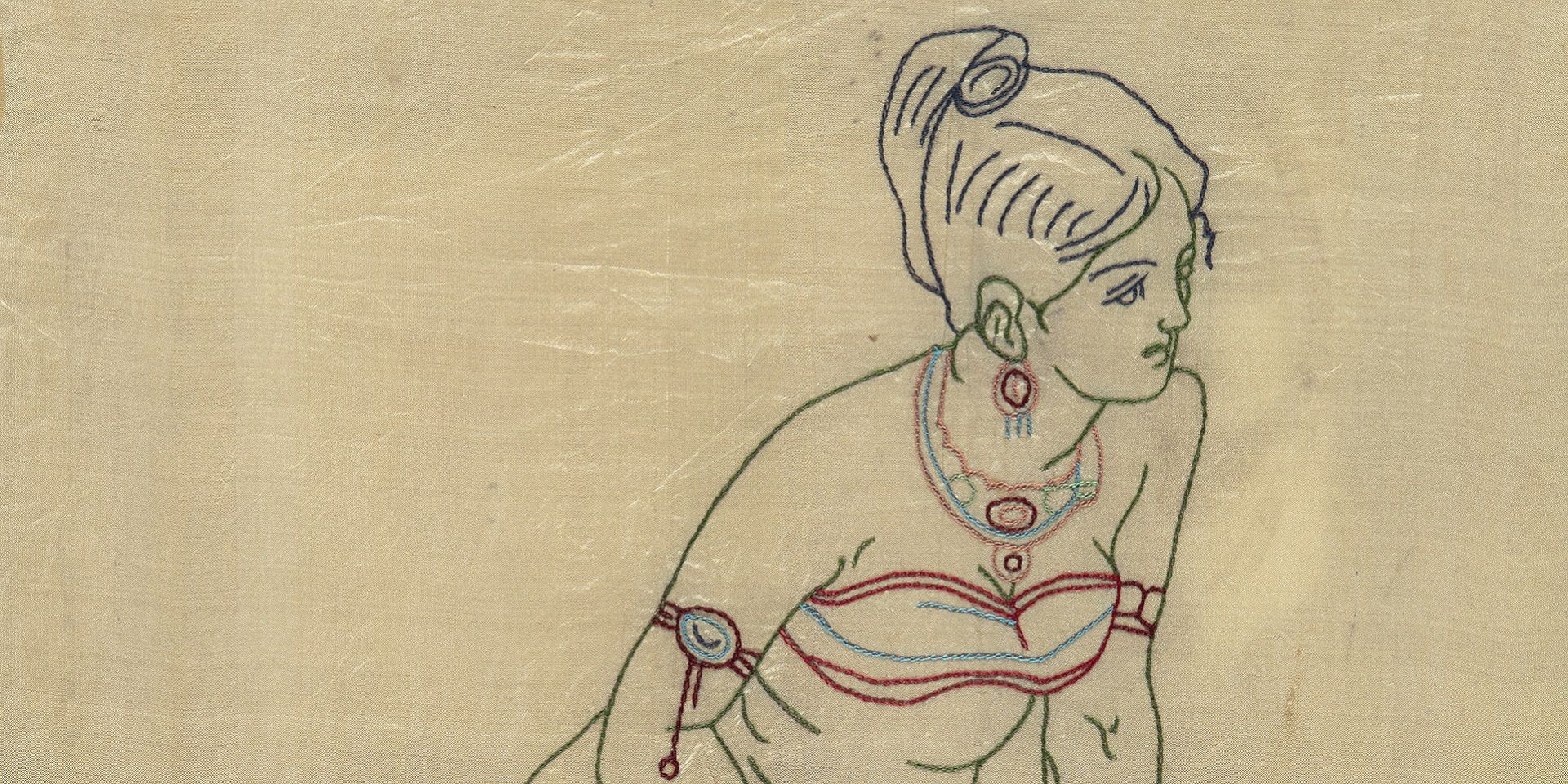

Designs by Nilima Sheikh for Nayika Bhed (Set of 6 Photographs), 1989. Image courtesy: Nilima Sheikh and Asia Art Archive

Q. I was curious about the framing of Asia Art Archive geographically as well. After beginning at Hong Kong, where did this pan-Asian perspective come in? And this geographical framing of AAA, how did that come about in the scope of the work of the organisation?

Sneha: The organisation was based out of Hong Kong, and I think Hong Kong’s own complicated colonial past as well as contemporary political reality had a lot to do with why the archive was not framed in national terms. The one thing that we are quite clear about is that art not just has complicated histories, it also has very complex geographies—whether we think about the movement of artists across borders or the movement of artworks circulating across borders. To limit the scope of an institution to just the national framework would be limiting. And so maintaining a critical position vis a vis the absurdity of thinking with national borders, I think is what led to AAA being imagined as ‘Asia’ Art Archive.

Digitization work in progress at AAA’s India offices. Image courtesy: Asia Art Archive in India

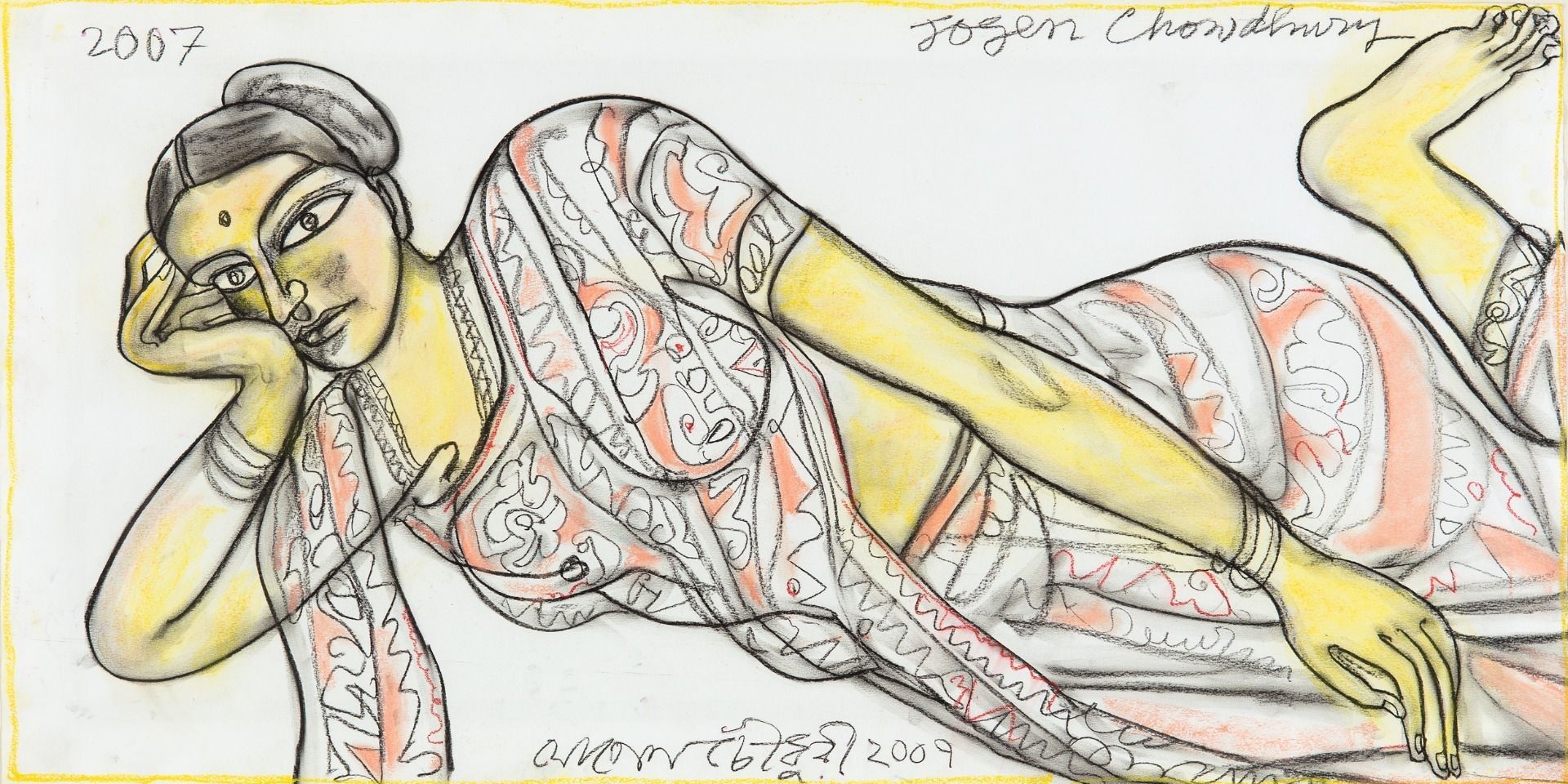

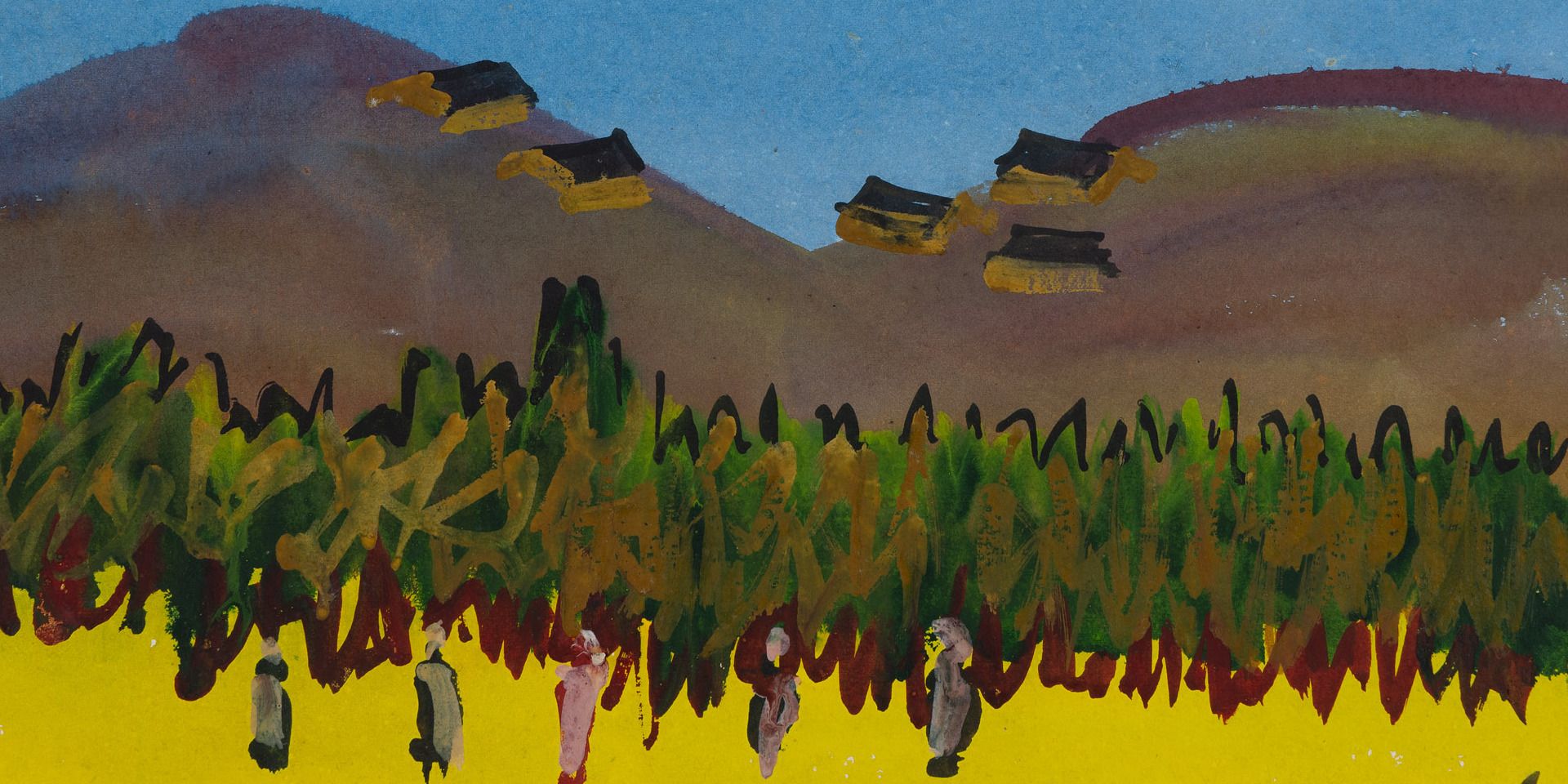

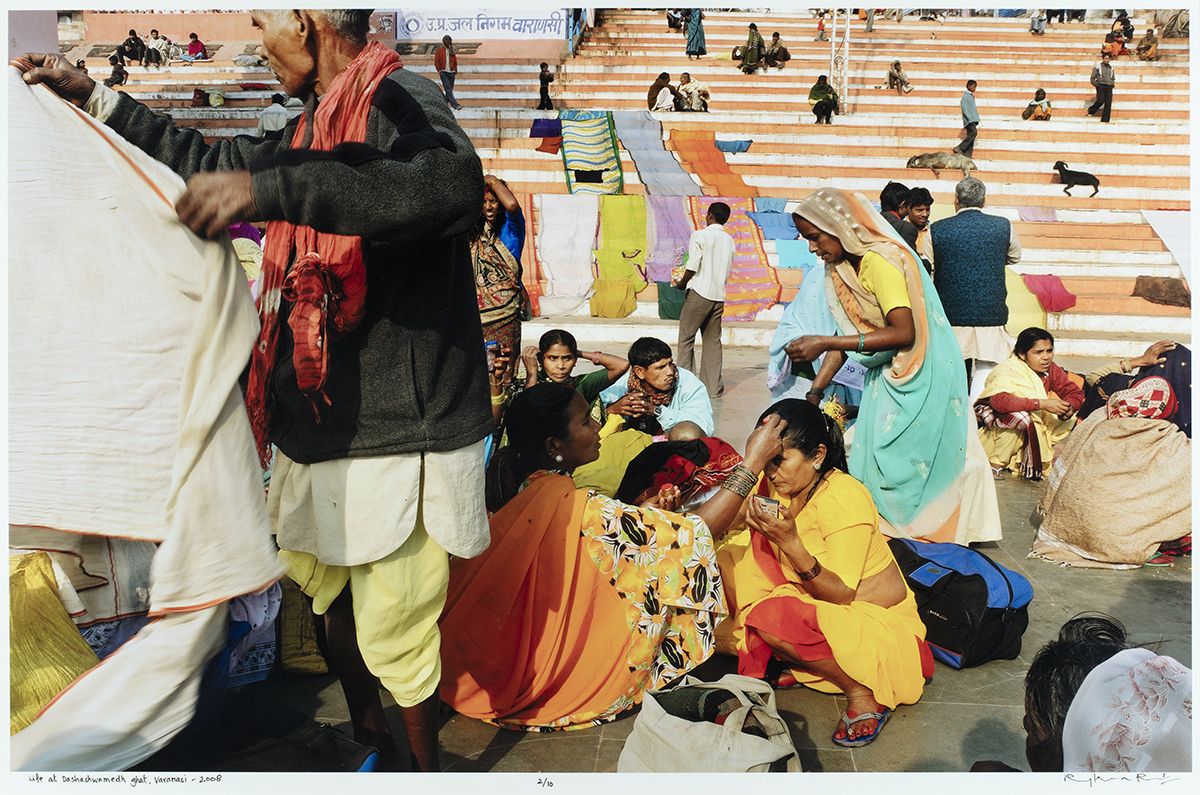

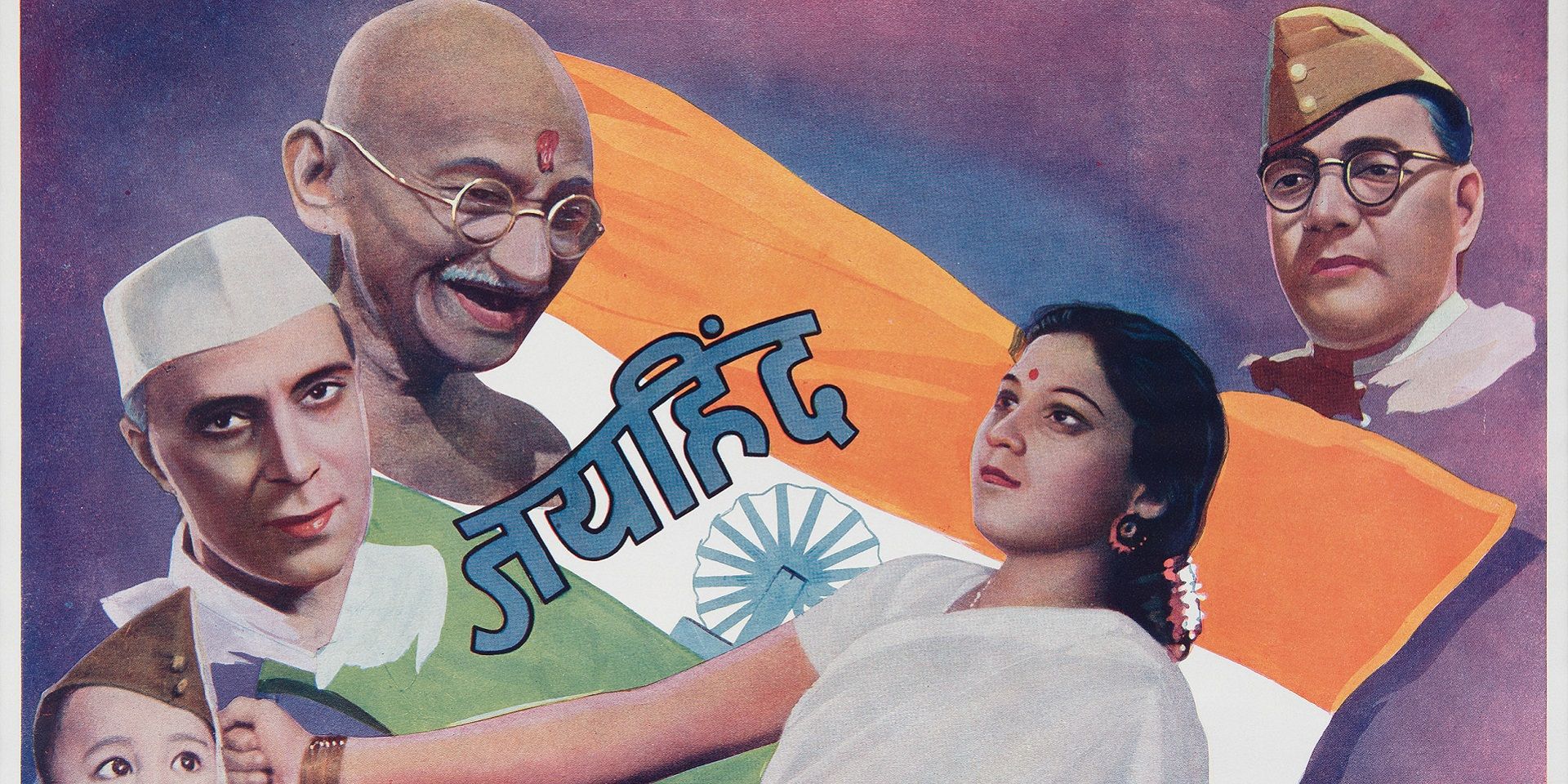

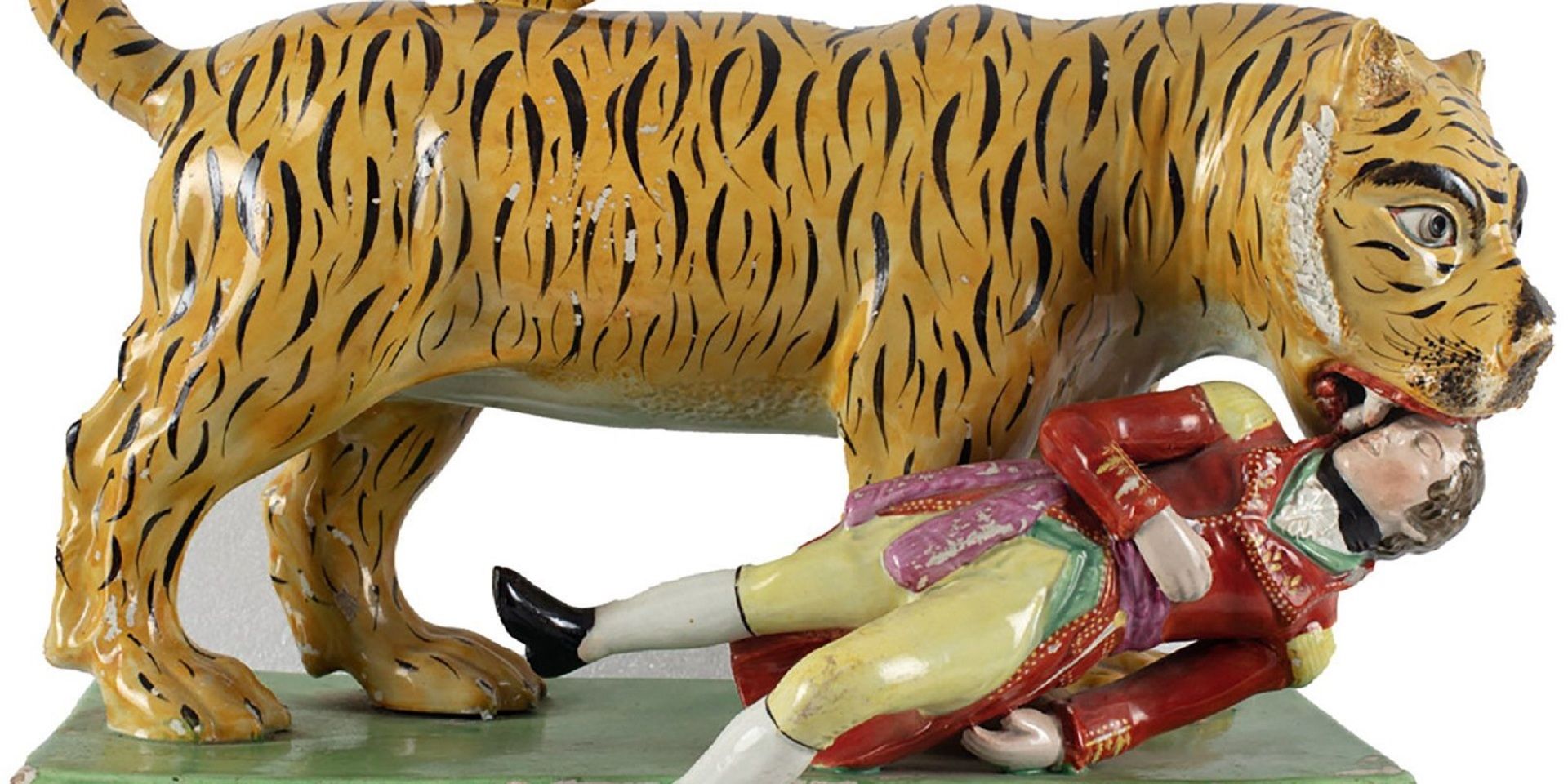

From the offices of the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong and India, we move to Dhaka, speaking with one of its most influential art collectors today. Durjoy Rahman was working as a businessman in the 1990s, when he would frequently get out of his offices during lunch hours to look at art in Dhaka’s galleries. This soon developed into a passion for collecting art that inspired him, starting with a woodcut by Rafiqun Nabi, one of the foremost artists and illustrators of Bangladesh. His personal collection grew over the next few decades, as he acquired works by some of the greatest modern and contemporary artists from South Asia—including Qamrul Hassan, Murtaja Baseer, Ram Kumar, Mithu Sen—and beyond. Inspired by his trips to the many art fairs and biennales mushrooming across the international map, he started the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF) in 2018. It is a non-profit organization that attempts to support and promote art from South Asia, with initiatives like the DBF Asia Art Future Awards. He spoke to DAG about his personal collecting practices, DBF and how building a foundation has allowed him to rethink the larger role of a collector in society.

|

Durjoy Rahman, founder of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF). Image courtesy: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation |

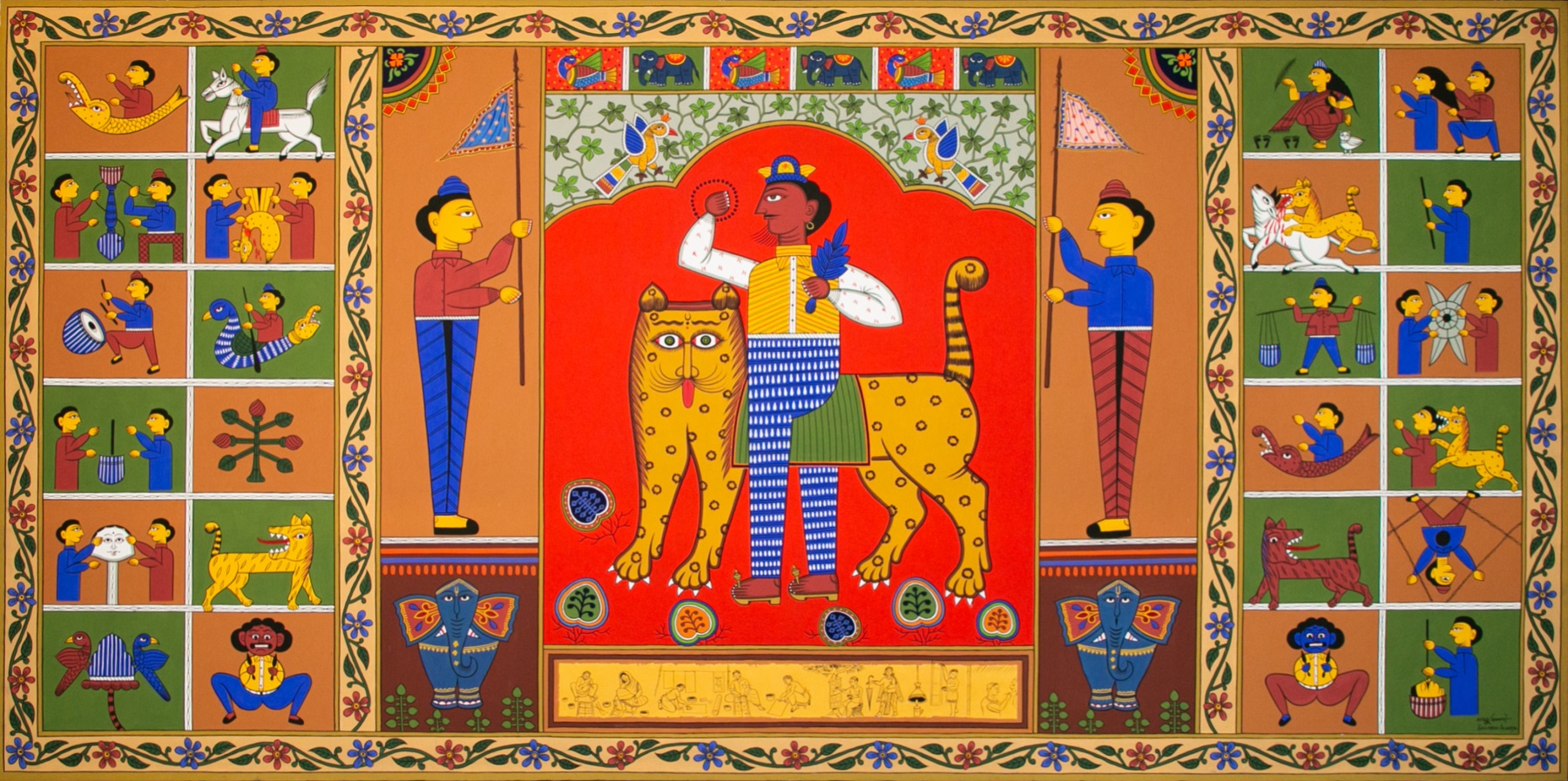

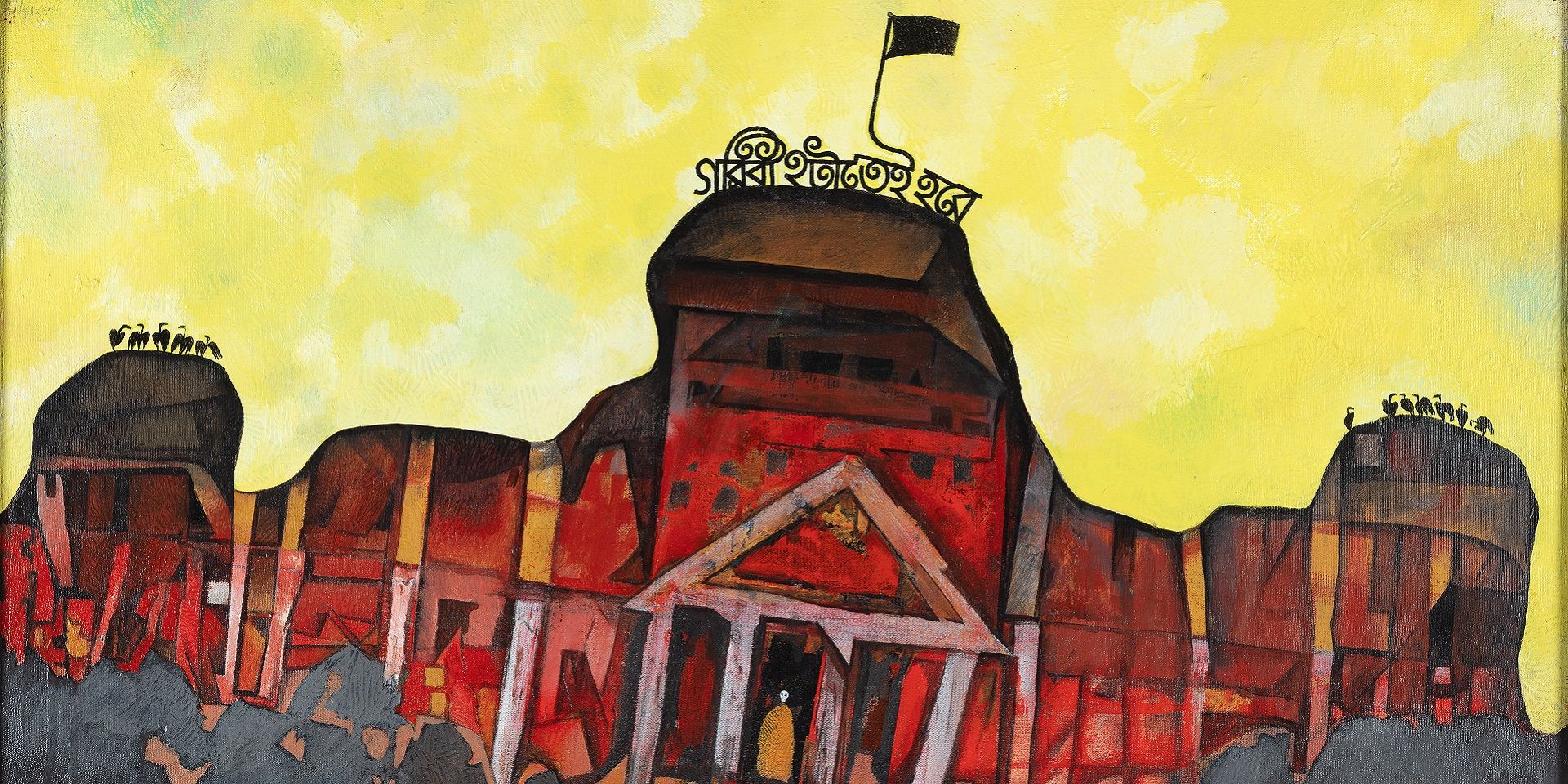

Shambhu Acharya, Gazirpot, 12X6 Feet. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Q. How long have you been an art collector and when did you decide to start an organization based around your collection? What were some of the early artworks you acquired?

Durjoy Rahman: For almost 30 years, I have collected art and have been particularly fascinated by pop art and graphic design. In 2009, I had the opportunity to showcase my collection at a personal exhibition, which was an exciting experience for me. The show not only highlighted my collection but also aimed to inspire and encourage young collectors. Following the success of the first exhibition, a 2014 exhibition showcased modern and contemporary art. My enthusiasm led me to create the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation in 2018 to support artists and art practitioners and promote Bangladeshi art to a global audience. The foundation organizes exhibitions, workshops, and talks, as well as provides grants and fellowships. Our mission is to establish Bangladesh as a cultural hub by fostering collaborations and exchanges with artists worldwide. As a collector, I have been enriched by my experiences and wish to share my passion with others through the foundation. With DBF, we aim to promote and showcase emerging and established artists and make the beauty of the art world accessible to all.

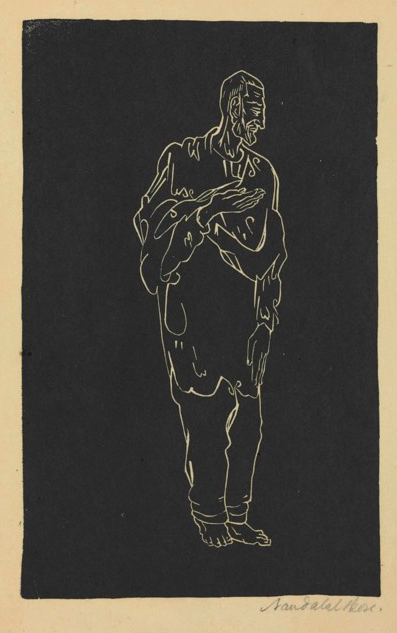

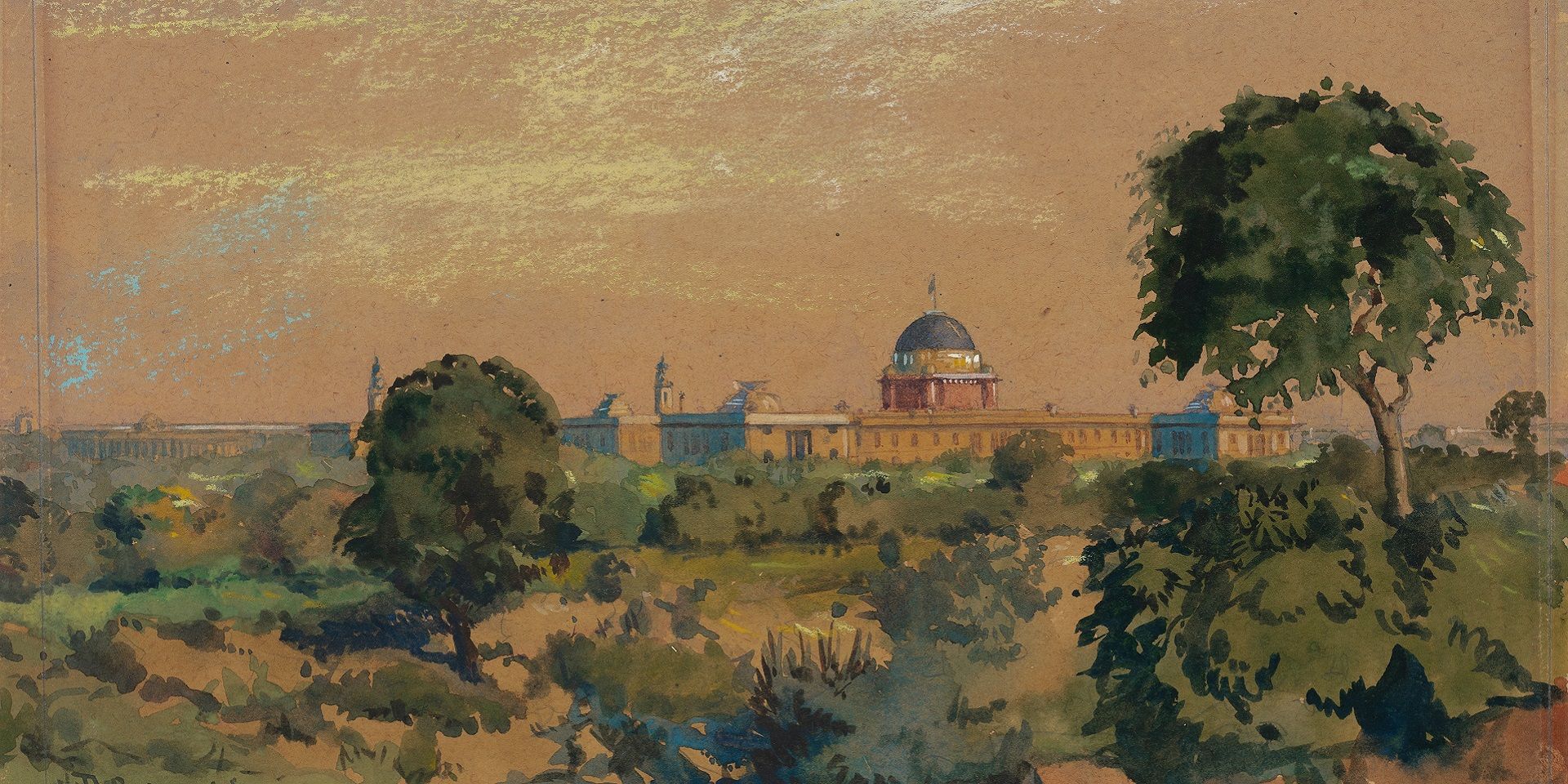

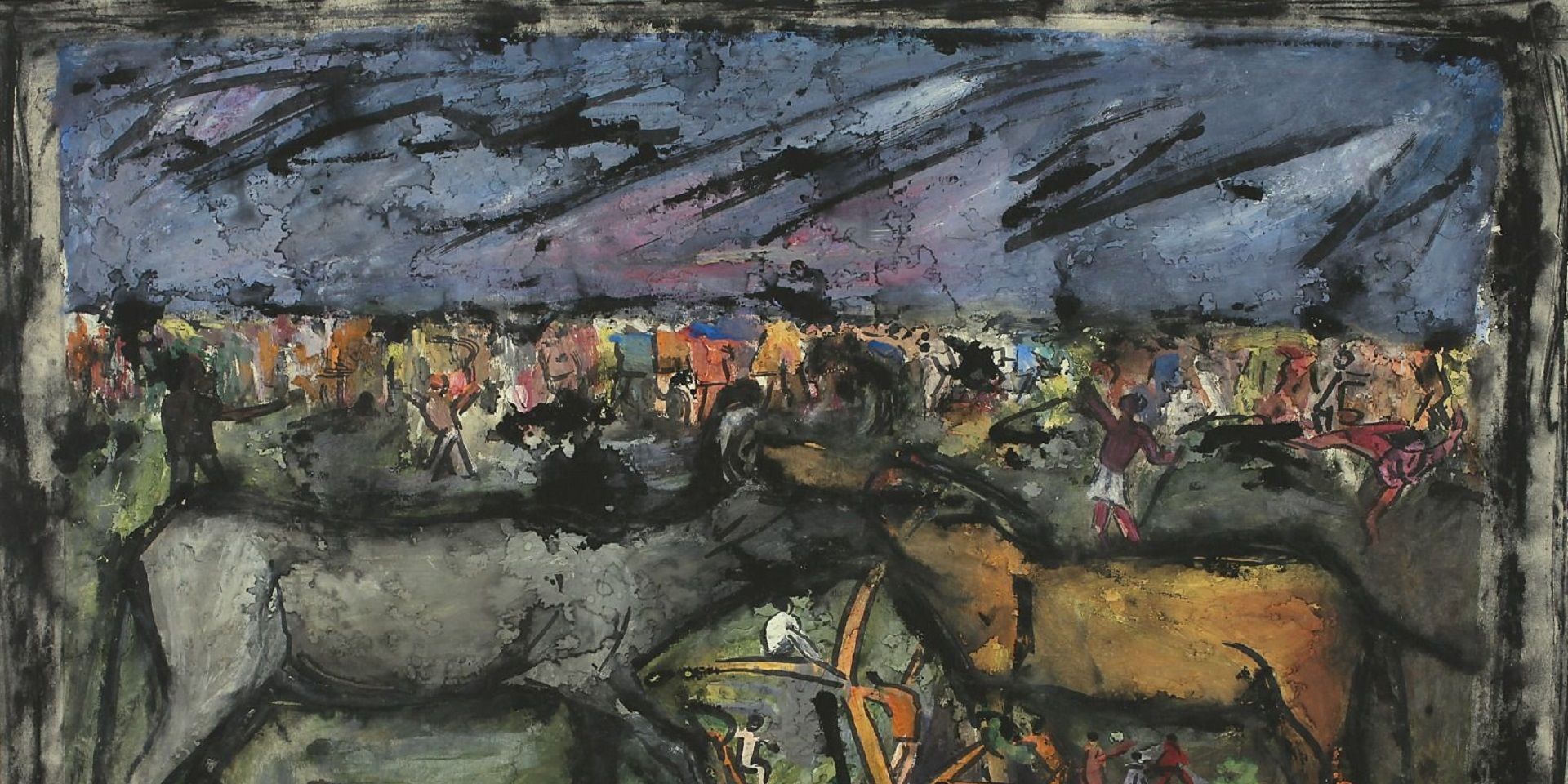

I like collecting early works from South Asian masters and prefer longer retrospective series. For example, Murtaja Baseer’s (1932-2020) works from the ’50s, Indian master artist Ram Kumar's (1924-2018) works from the ‘60s, and Nandalal Bose’s (1882 -1966) works from the ‘30s. My collection offers a unique perspective into these masters' artistic journeys.

|

Ram Kumar, Labyrinth of a Town, 1964, 99 X 82 cm. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation |

Q. How do you decide to collect works personally in contrast with what you collect for the foundation?

Durjoy: While my personal collection consists of works by South Asian masters, my collecting pattern for the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF) is different. DBF collects works that address activism, such as displacement, migration, environment, and post-colonial narratives. These themes are essential in creating a narrative and purpose for DBF to collaborate with artists and the community. Although the landscape of my collecting has not changed, the purpose has widened to accommodate DBF's mission of promoting art with a social conscience.

|

DBF Creative Studio in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Image courtesy: Durjoy Bangaldesh Foundation |

Q. How do you balance the idea of a non-profit organization for arts engagement and education with the challenges of negotiating a strong market-driven orientation for collecting new art?

Durjoy: The demand (for art) and market forces have always played a critical role in ensuring the long-term sustainability of any organization. Our goal is to promote artists, scholars, and institutions whose practices have future market potential or can drive growth through our involvement. We welcome these evolving scenarios as they bring us closer to our main objective of promoting art from South Asia.

Murtaja Baseer, Epitaph,1977, 35.5 X 56.5 inch, Oil on Canvas. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Q. Since your collecting practice extends across South Asia, how do you determine what to collect from different markets? Do you have an agenda before arriving at art markets/fairs and biennales or do you respond to your own studied instincts about collecting old masters and new works?

Durjoy: In the modern digital environment, with the increasing number of fairs, artist talks, and events, planning a roadmap is not difficult. Furthermore, DBF has a clear objective and mission, and we prioritize artworks and practices that fall within our mission. We keep a closer eye on these works to ensure that we stay true to our goals and objectives.

|

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (Abdul Gaffar Khan), 1936, Linocut, sheet: 13 ¼ X 8 ¾ in. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation |

Andy Warhol, Liz, 1965, 58.7 X 58.7 cm, Offset Lithograph on paper. Collection: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

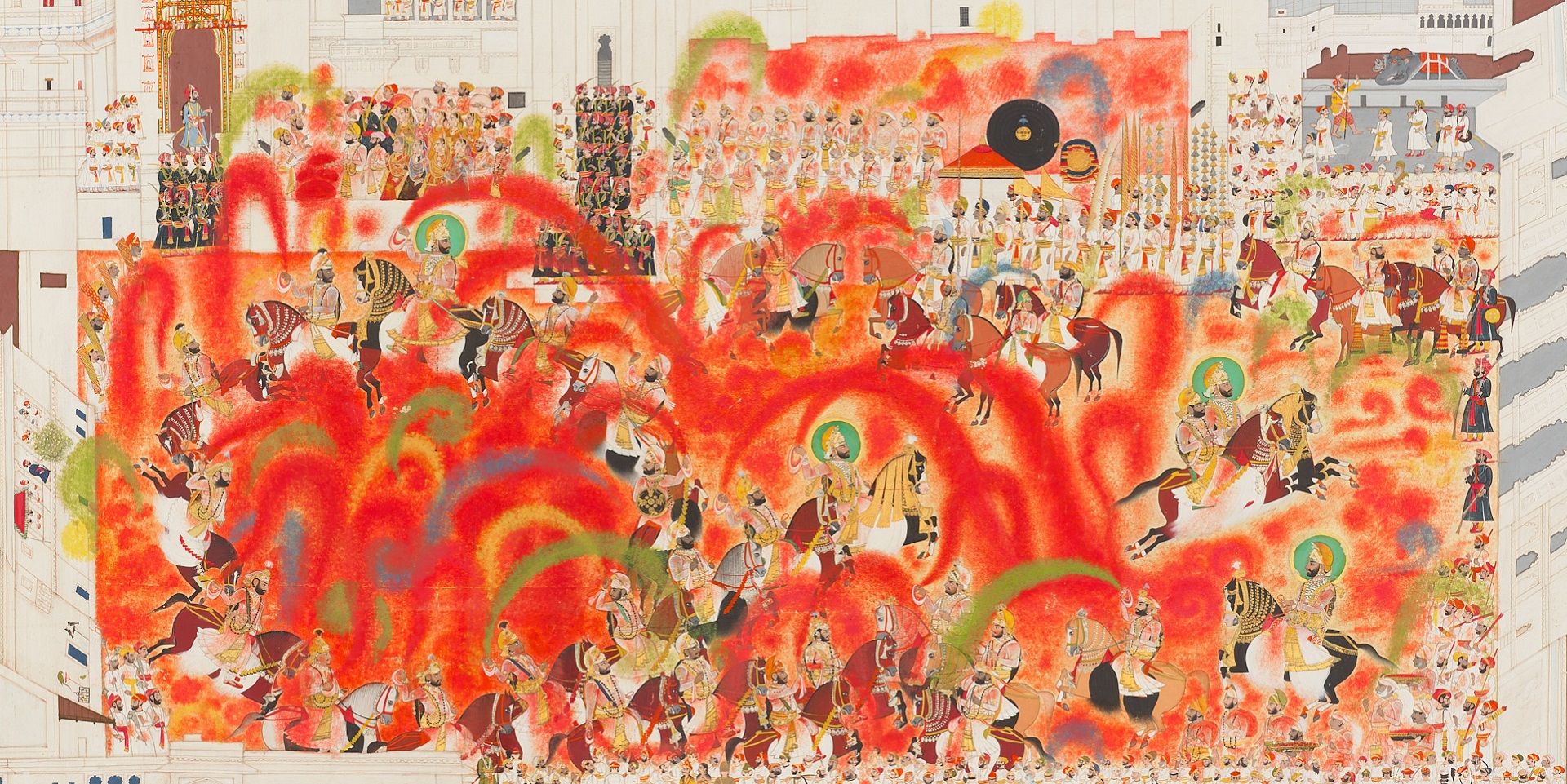

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025