The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

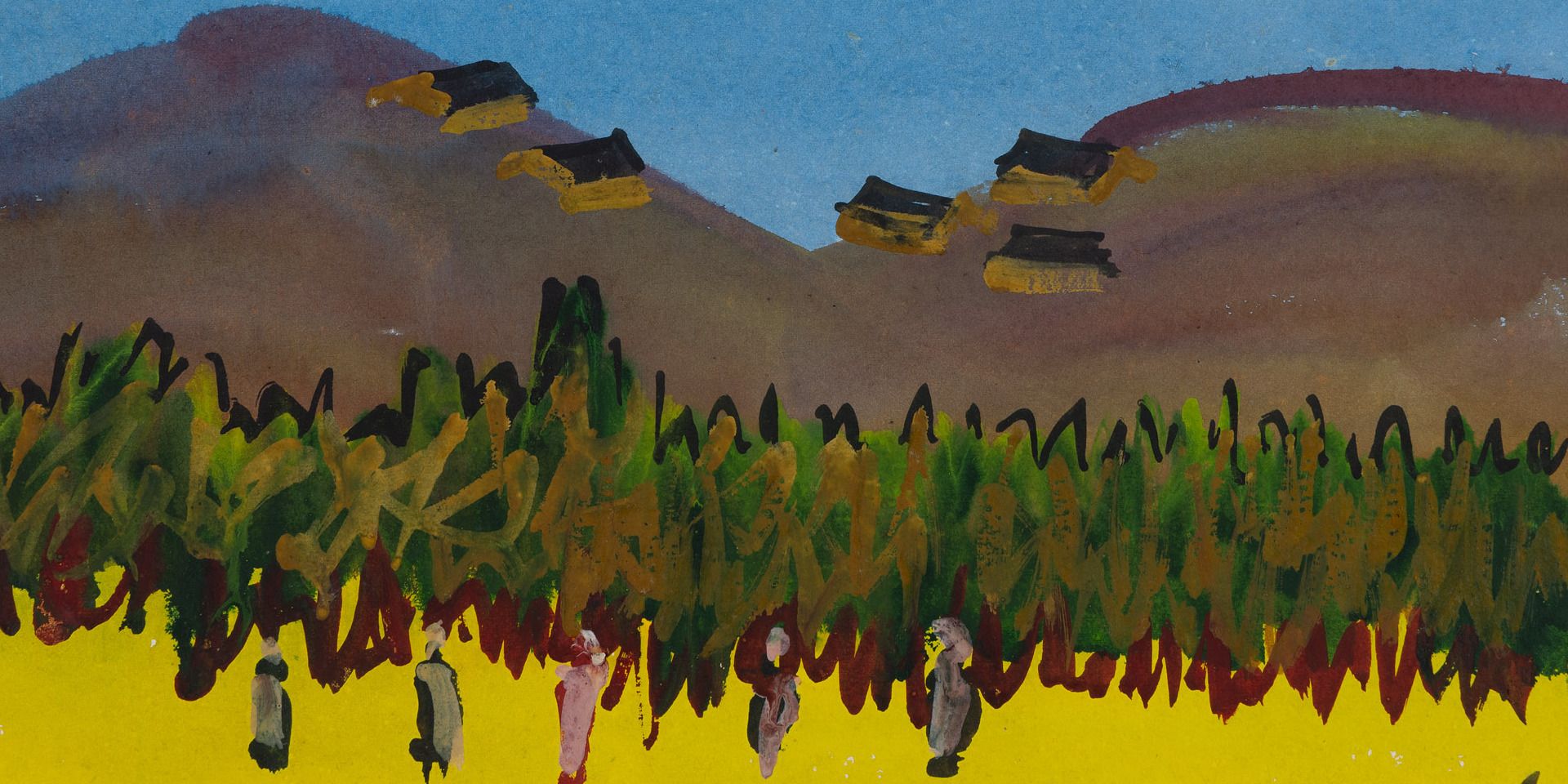

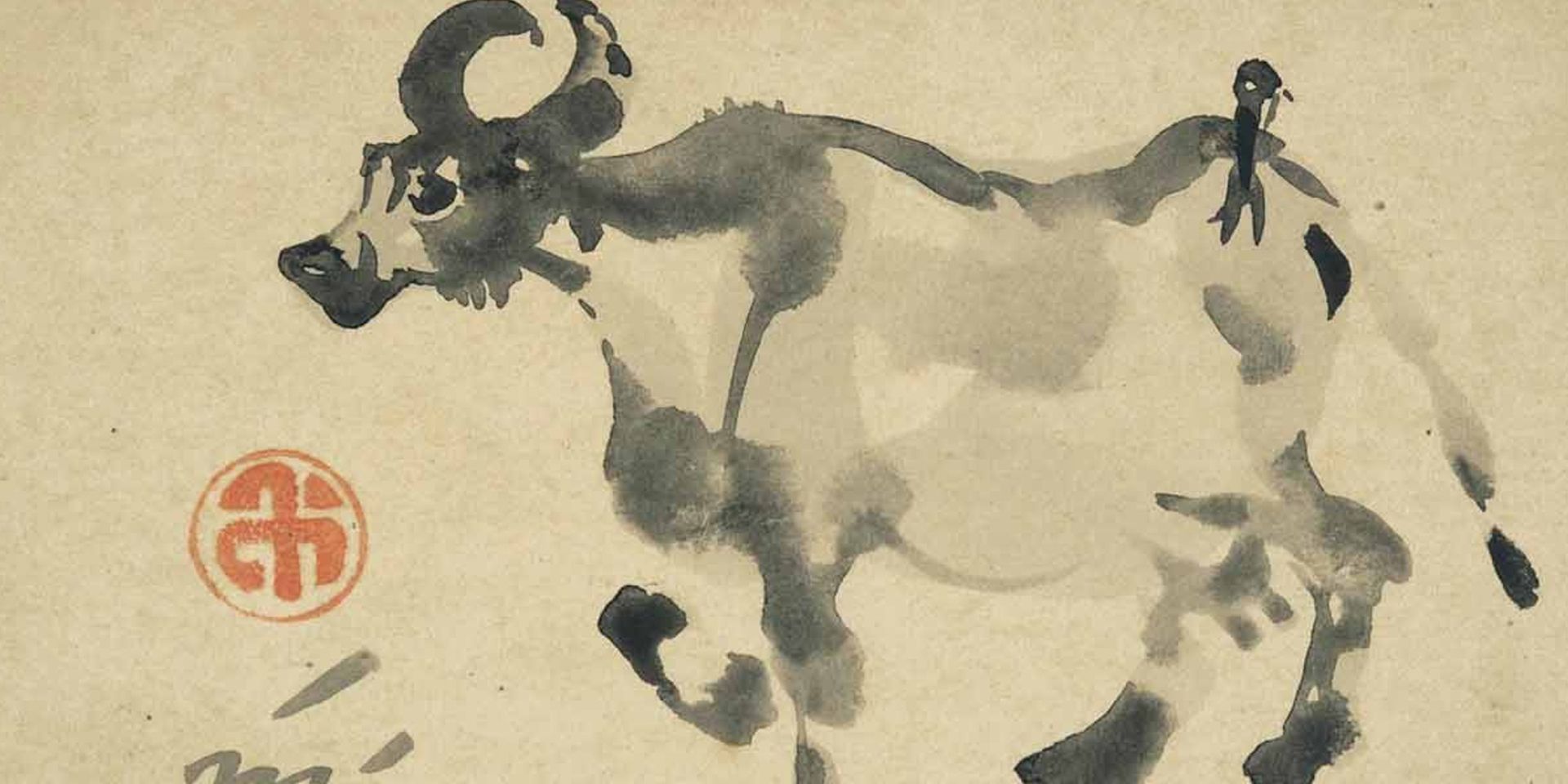

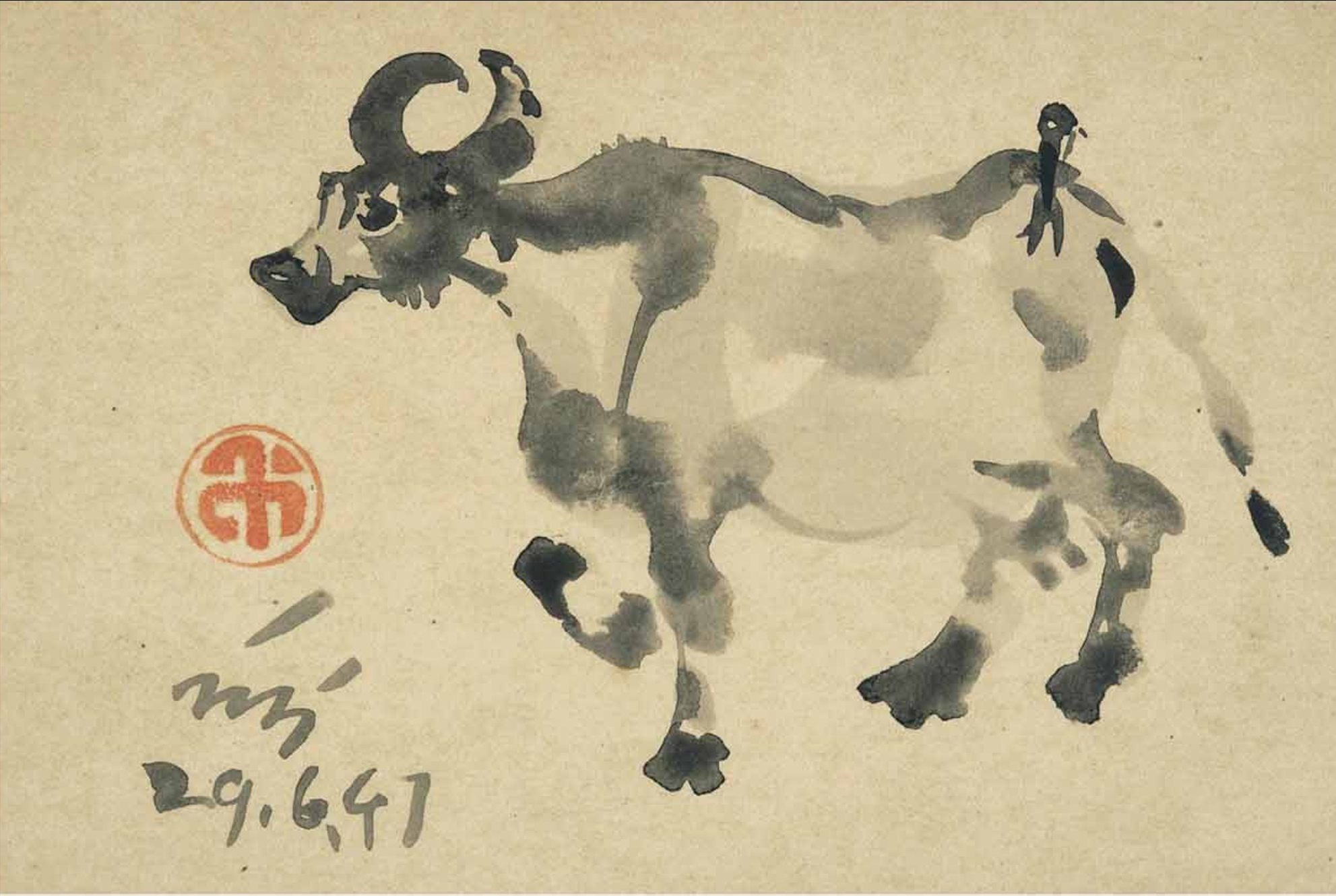

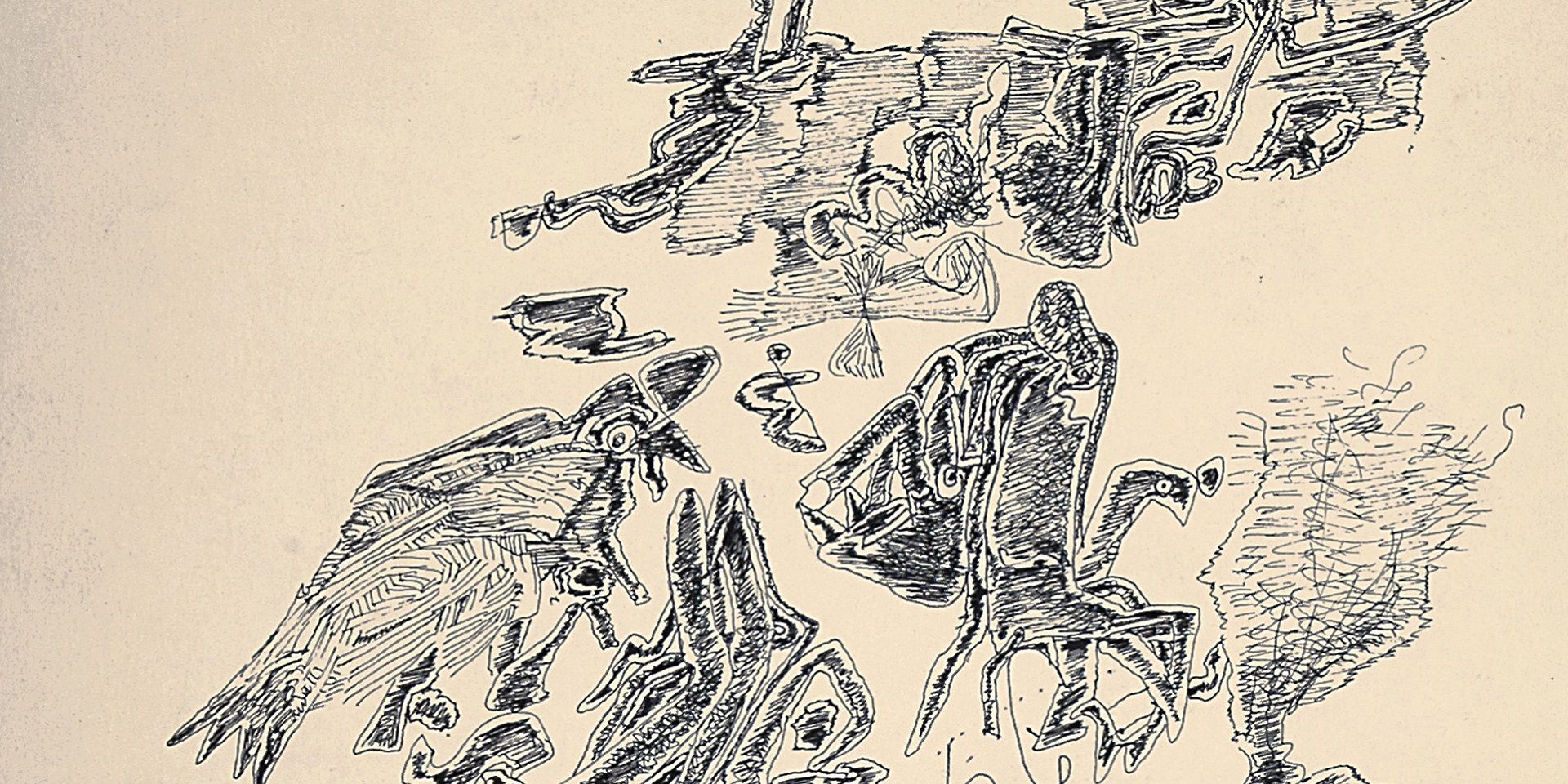

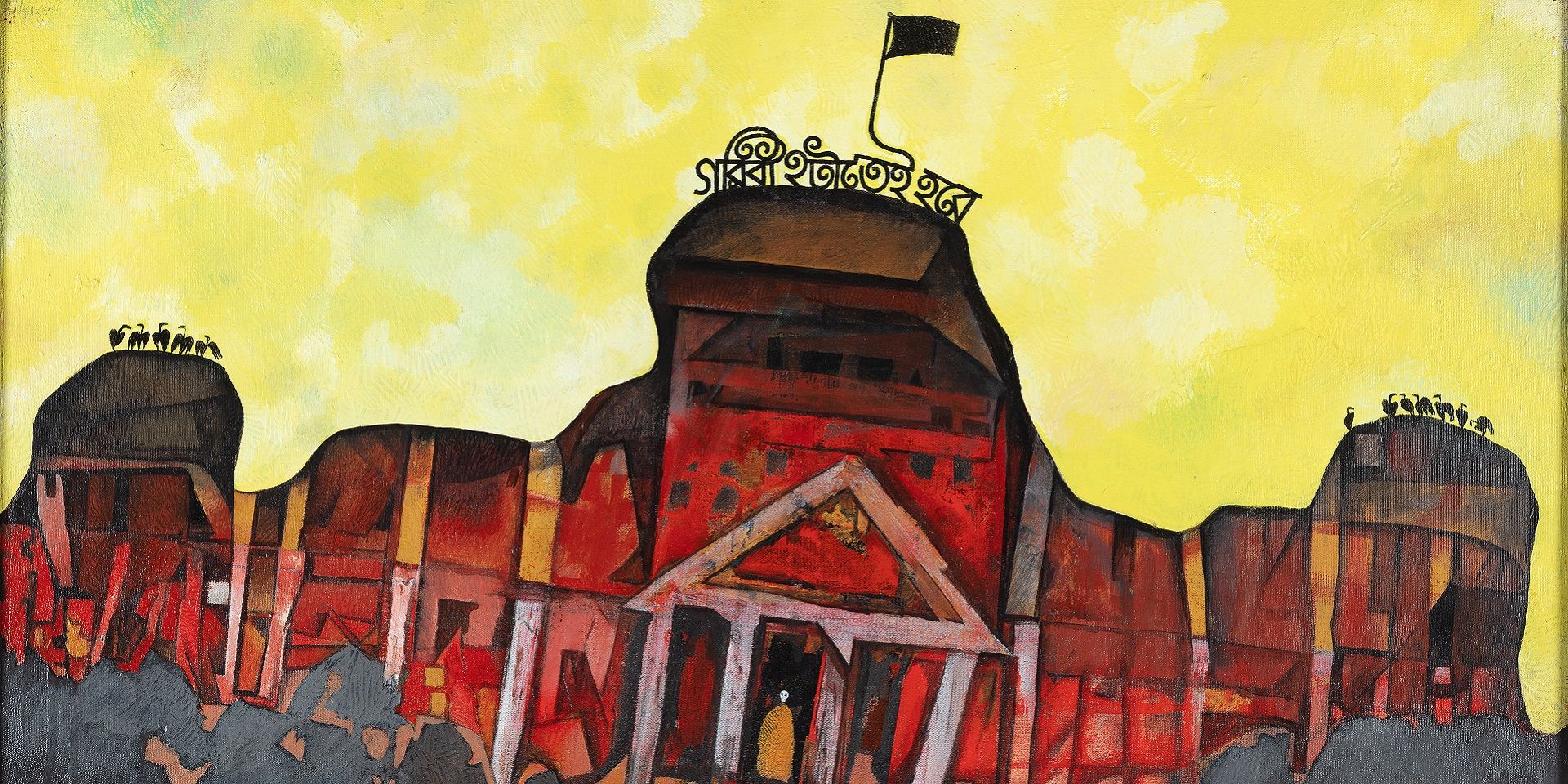

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (detail), Ink on postcard. Collection: DAG

Sugata Bose is the Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University, U.S.A. His books on Indian subcontinental history, including its oceanic histories, have shaped our understanding of the various strands that gave birth to the modern nation states of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

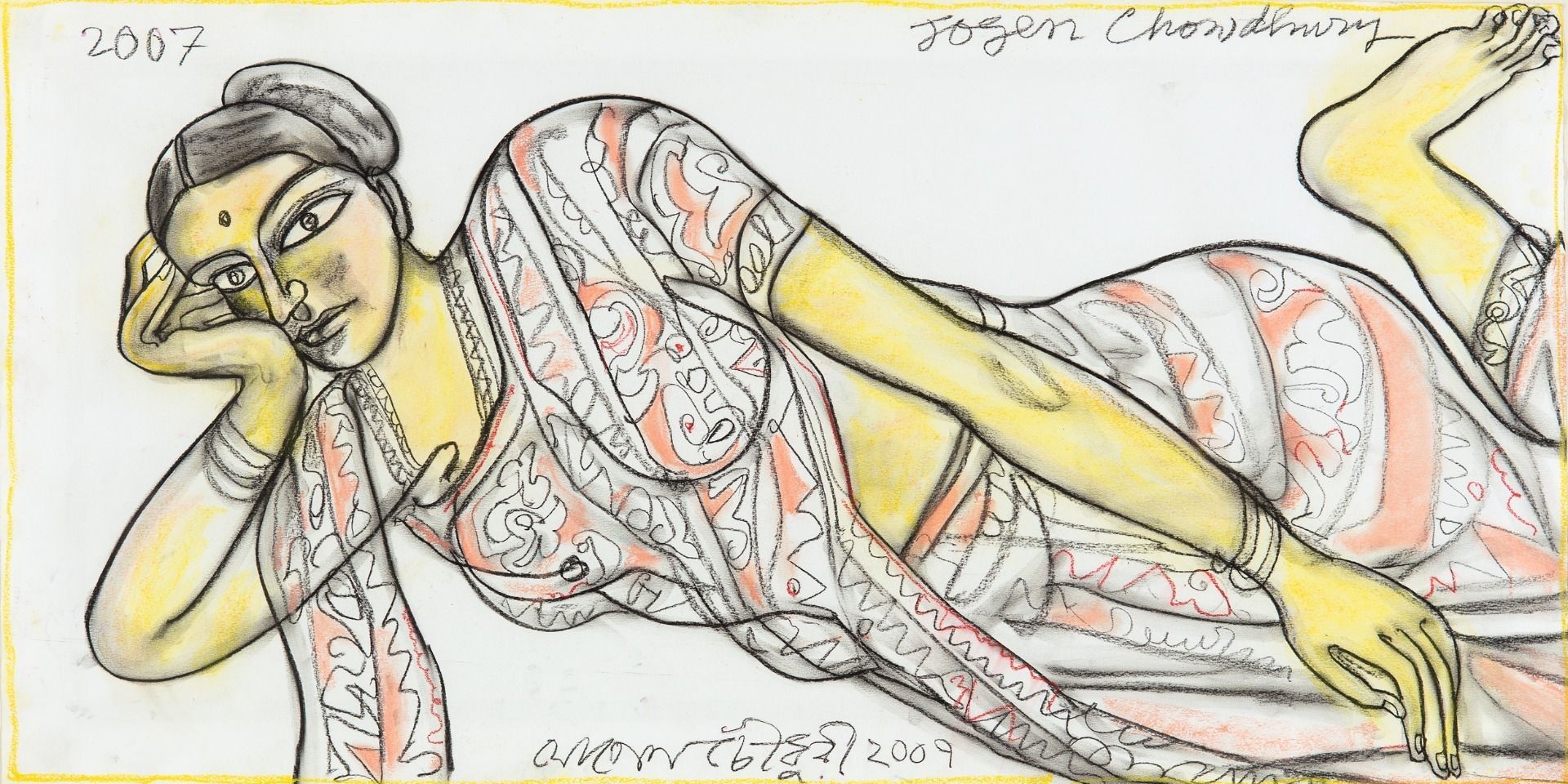

In his new book, Asia After Europe, Dr. Bose expands his vision to capture the imaginary formations of pan-Asianism, which served as a critical method to look beyond the national aspirations of Asian countries in the twentieth century. A plea for greater regional coherence against the global imperium dictated from Europe, pan-Asianism occupies a complex moment of political and social idealism in Asia, which was largely driven by artists and writers, rather than political leaders. Thus, figures like Rabindranath Tagore, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, Okakura Kakuzō, Xu Beihong and Nandalal Bose feature prominently in his account.

The demand for a nation may have been a colonial graft, supplanting alternative conceptions of sovereignty in Asia, but Dr. Bose shows how a range of intellectuals, artists and reformers—ranging from Indians to Filipinos, Chinese and Japanese intellectuals—resisted this toxic legacy while maintaining their own interests in their country as a constituent of a larger geographical and cultural force. He spoke to the editor the DAG Journal about his book, and what follows is an edited version of it.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, Watercolor on postcard. Collection: DAG

Q. Your book tries to restore lost dimensions of pan-Asianism, which you show to be a conscious, cross-cultural ‘movement’, starting from the early twentieth century, informing intellectual, artistic and cultural currents that attempted to look beyond the limiting potentialities of the nation-state and draw from the energies of the global anti-colonial movements of the time. Interestingly enough, your book suggests that some of the earliest provocateurs of the pan-Asian ideal were art critics and artists, especially figures like Okakura Kakuzō and Sister Nivedita (Margaret Noble). Why did you choose to give artists and art critics a near-central role in this project of constructing pan-Asian identity? And what role did aesthetic ideals generally play in crafting this vision of pan-Asianism?

Sugata Bose: I trace the roots of Asianism in the modern era to the 1880s. Many historians foreground Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905 in narrating this history. Yet the quest for Asian universalism in the domain of culture preceded this landmark political and military event. The art critic Okakura Tenshin and the artists Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunso visited India between 1901 and 1903. Sister Nivedita wrote the introduction to Okakura’s book The Ideals of the East that appeared from London in 1903. As she put it, Okakura had shown Asia ‘not as the congeries of geographical fragments that we imagine, but as a united living organism, each part dependent on all the others, the whole breathing a single complex life.’ Rabindranath Tagore acknowledged Okakura as a pioneer in exploring Asian connections. I have simply given artistic conversations and collaborations across Asia the place they deserve in the larger history of Asia after Europe.

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled (Namaz), Woodcut on newsprint paper. Collection: DAG

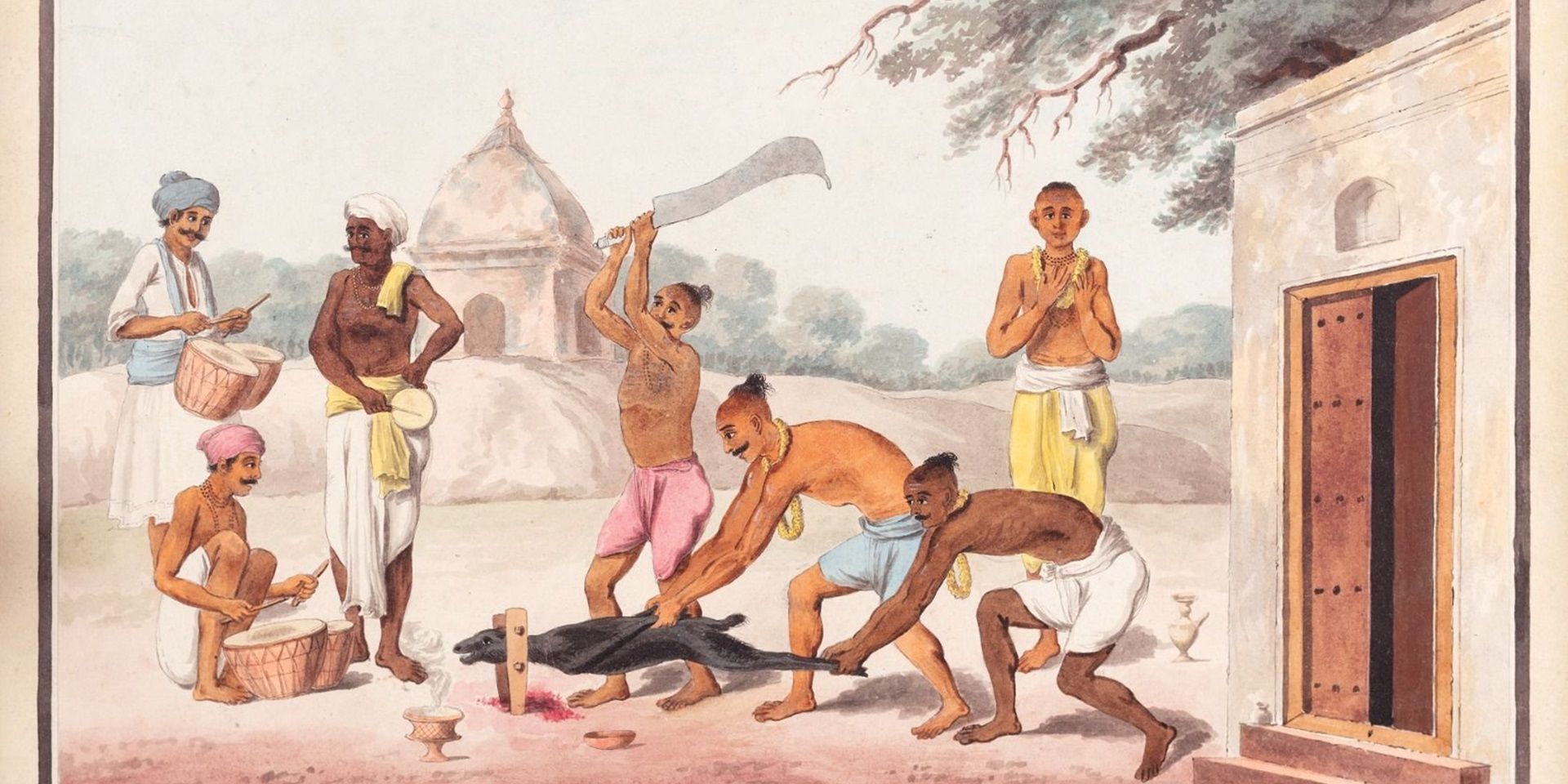

Q. You write about significant artistic exchanges that took place with the arrival of Japanese artists and students like Taikan Yokoyama and Shunso Hishida in Calcutta’s Jorasanko household where Abanindranath and Gaganendranath learned from their techniques and taught them some of their own iconic Indian motifs and figures. Shokin Katsuta would also teach briefly at the Government School of Art, Calcutta (1905-1907) when Abanindranath was the Vice-Principal. Chinese artists like Xu Beihong also engaged substantially with Indian figures and aesthetic ideas, which are memorialized in Kolkata’s Jorasanko Museum as well. How do you see this period of exchange influencing the trajectory of Bengal modern art?

Sugata: The Japanese and Indian artists learned from one another. If Abanindranath and Gaganendranath imbibed the techniques of slow drawing of lines and the Japanese wash from Taikan, they imparted methods of Mughal and Persian paintings to their Japanese guests. The visitors took up Indian themes in their art as exemplified by Taikan’s Raas-Leela that was installed in Abanindranath’s studio in 1903. Taikan’s Kali and Hishida Shunso’s Saraswati were bought by Swarnakumari Devi. They were still hanging on the walls in her Calcutta home when Yone Noguchi visited her daughter Sarala Devi Chaudhurani in 1935. High-quality reproductions of these paintings were printed in Rupam in 1922. This art magazine is well preserved in the Fine Arts Library at Harvard. Xu Beihong arrived in Santiniketan from China in 1940 and interacted with Abanindranath, Nandalal Bose, and Benode Behari Mukherjee. He was a versatile genius. He not only painted portraits of Rabindranath and Gandhi but produced exquisite landscapes of the Himalayas as viewed from Darjeeling.

|

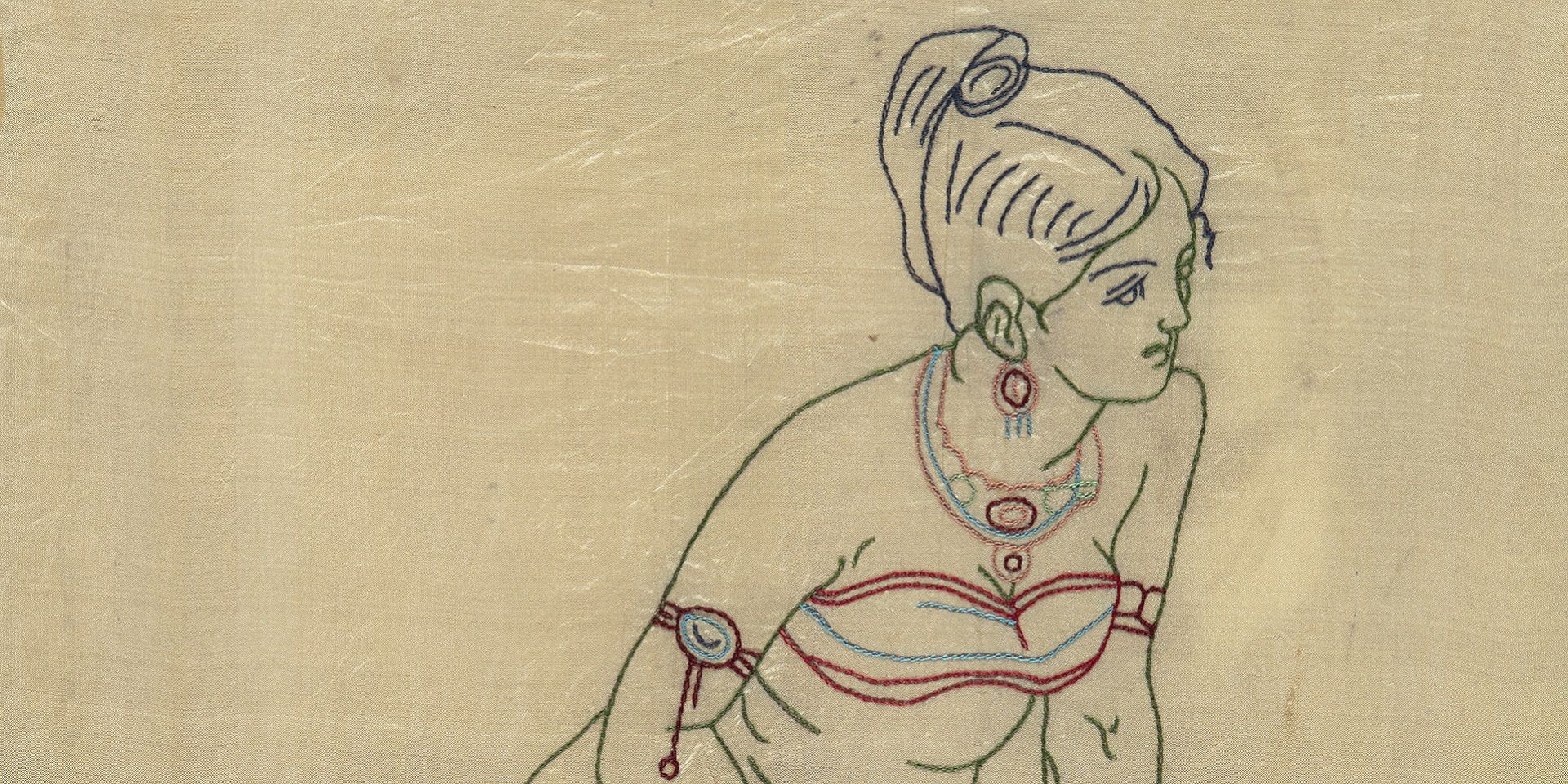

Katsuta Shokin, Untitled (Rama's Parting), c. 1906-07, Gouache, watercolour and gold pigment on silk pasted on board, 40.2 x 16.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Yokoyama Taikan, Holy peaks of Chichibu at spring dawn, 1928, Hanging scroll, ink on silk. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

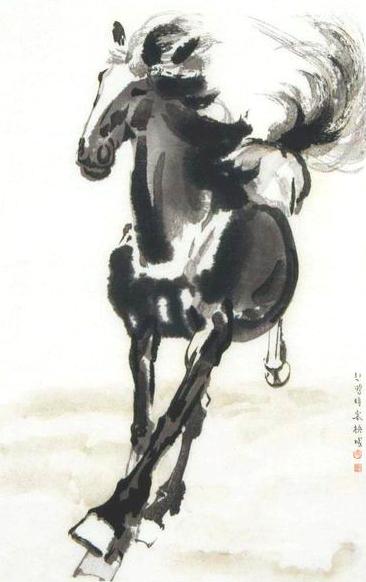

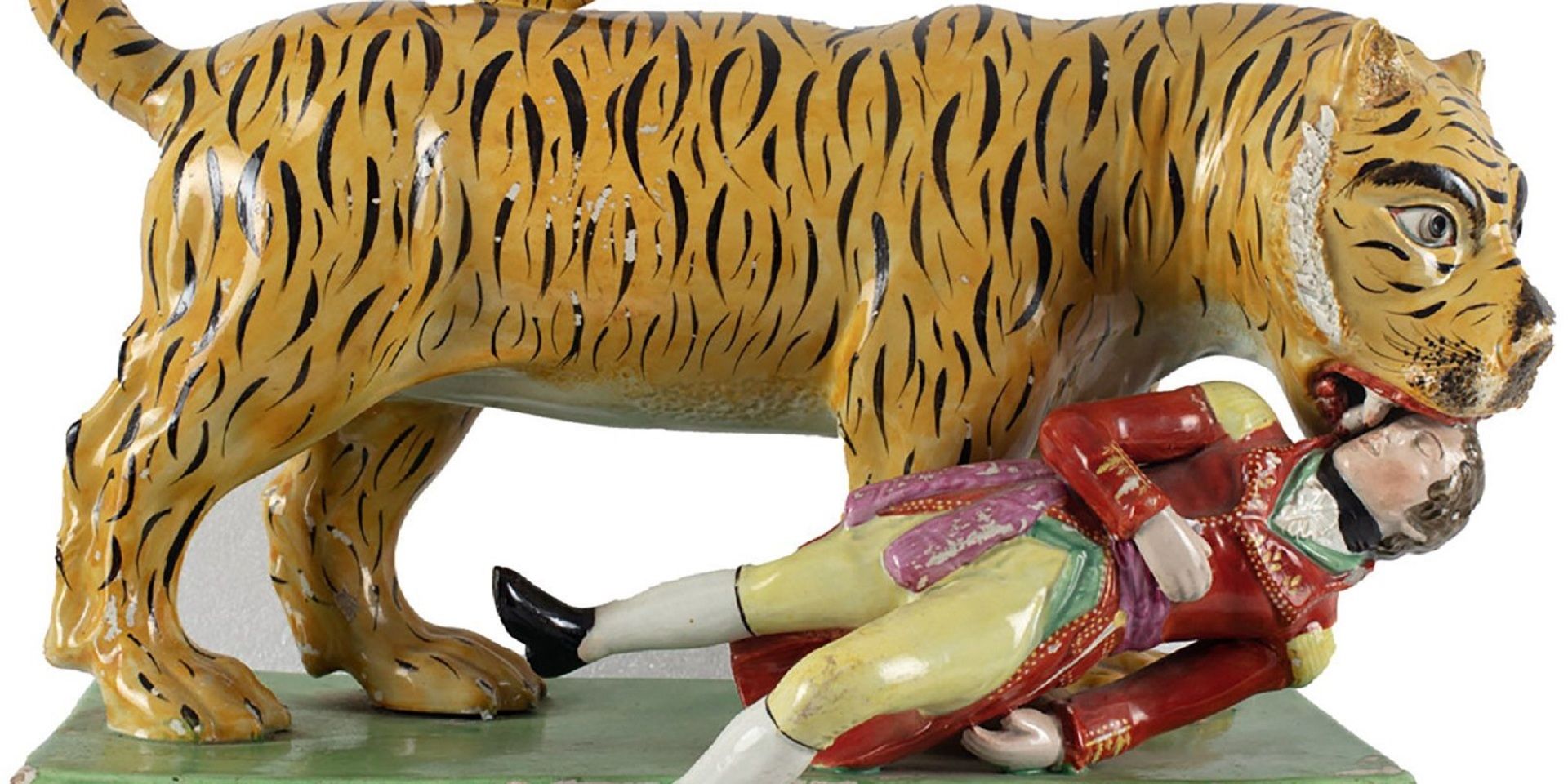

Of course, cosmopolitan influences arrived from Europe as well as Asia. For example, there was a large exhibition of Bauhaus art in Calcutta in 1922 and Benoy Kumar Sarkar organized a show of art of the Bengal School in Berlin the following year. However, I show in Asia after Europe that Asians were able to forge a rather special affective bond. Another episode of an Asian connection occurred in 1952 when Maqbool Fida Husain was mesmerized and deeply influenced by Xu Beihong’s horses in Beijing.

|

Xu Beihong, Galloping Horse. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Q. Abanindranath’s iconic Bharat Mata image was one of the creations of the ‘hybrid’ wash style as you point out. Somewhat ironic for the subject matter, its process of construction acknowledges a wider history of aesthetic influence than what critics like Nivedita were willing to give it credit for. Did it serve a strategic purpose to name the image after a feminised evocation of the nation at the time, or do you think the name we know it by today deviates substantially from Abanindranath’s conception of the image and its original name, which was Bangamata (Mother Bengal)?

Sugata: Abanindranath’s Bharatmata is perhaps the most famous example of the Japanese wash in an Indian painting. There are remarkable similarities with Hishida Shunso’s Saraswati. I think Nivedita did recognize what you are describing as ‘a wider history of aesthetic influence’ in its creation. I quote her critical appreciation in my book: ‘The curving line of lotuses and the white radiance of the halo are beautiful additions to the Asiatically conceived figure with its four arms, as the symbol of the divine multiplication of power.’

|

Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, Chromolithograph on paper. Collection: DAG |

It is well known that Abanindranath had in mind his daughter’s face as he painted the visage of the divine mother. That is what gave the painting its quality of intimacy. Perhaps the original title Bangamata was closer to the artist’s own conception, but Nivedita’s suggestion to gift it to India as a whole had its own charm. After all, the regional identity was not at odds with an overarching nation in the making during the early twentieth century. That tension developed later and has reached new proportions today.

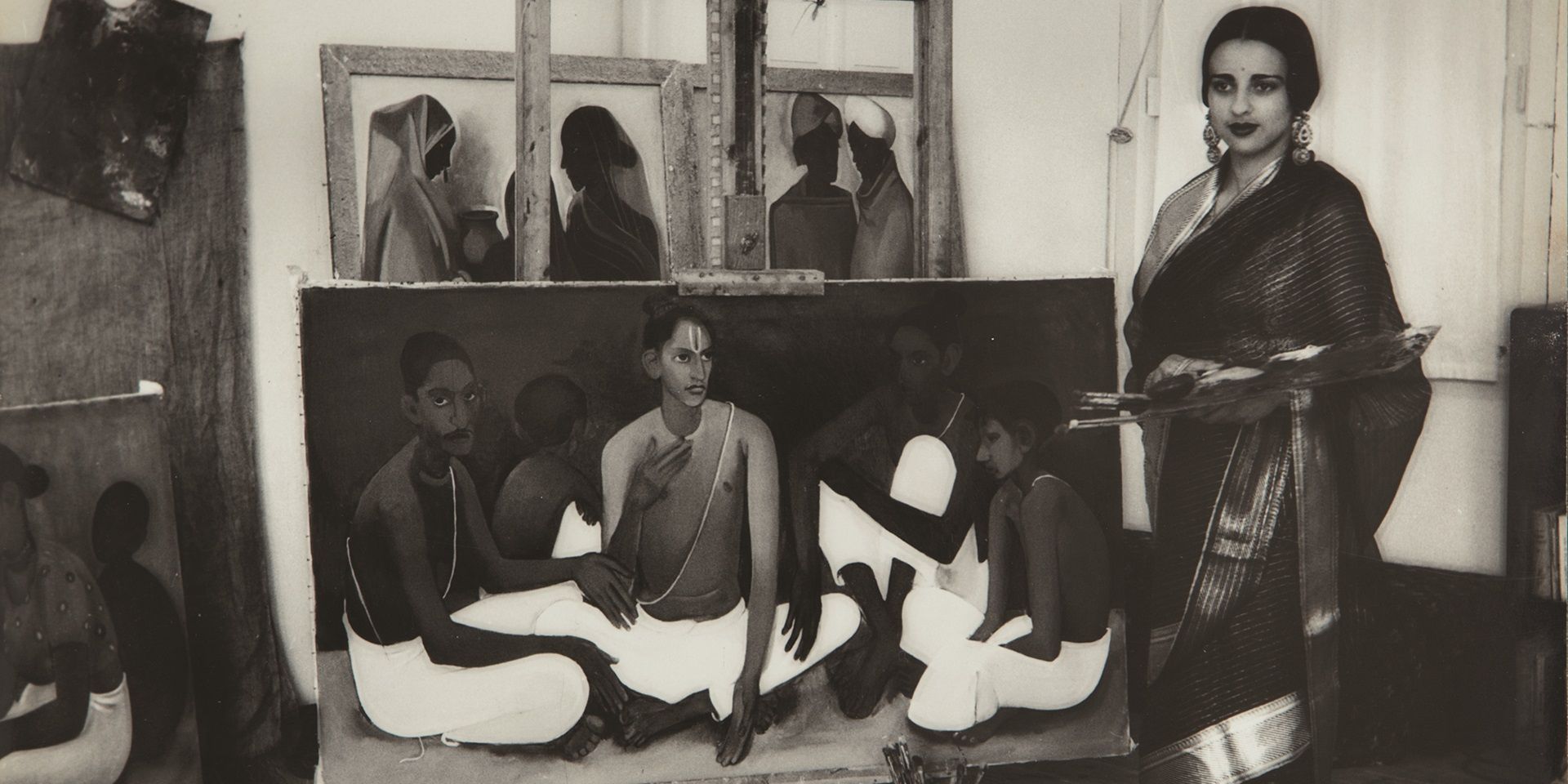

Q. Artists like Nandalal Bose were also a significant figure in constructing this transitional aesthetic, due to his own travels (usually with Rabindranath) to China, or taking Okakura around to visit Indian temples, like the one at Konarak. As a pedagogue at Santiniketan and master artist himself, how do you see him negotiating these influences in his own work as a teacher and artist who learns from the studio of the Tagores as well?

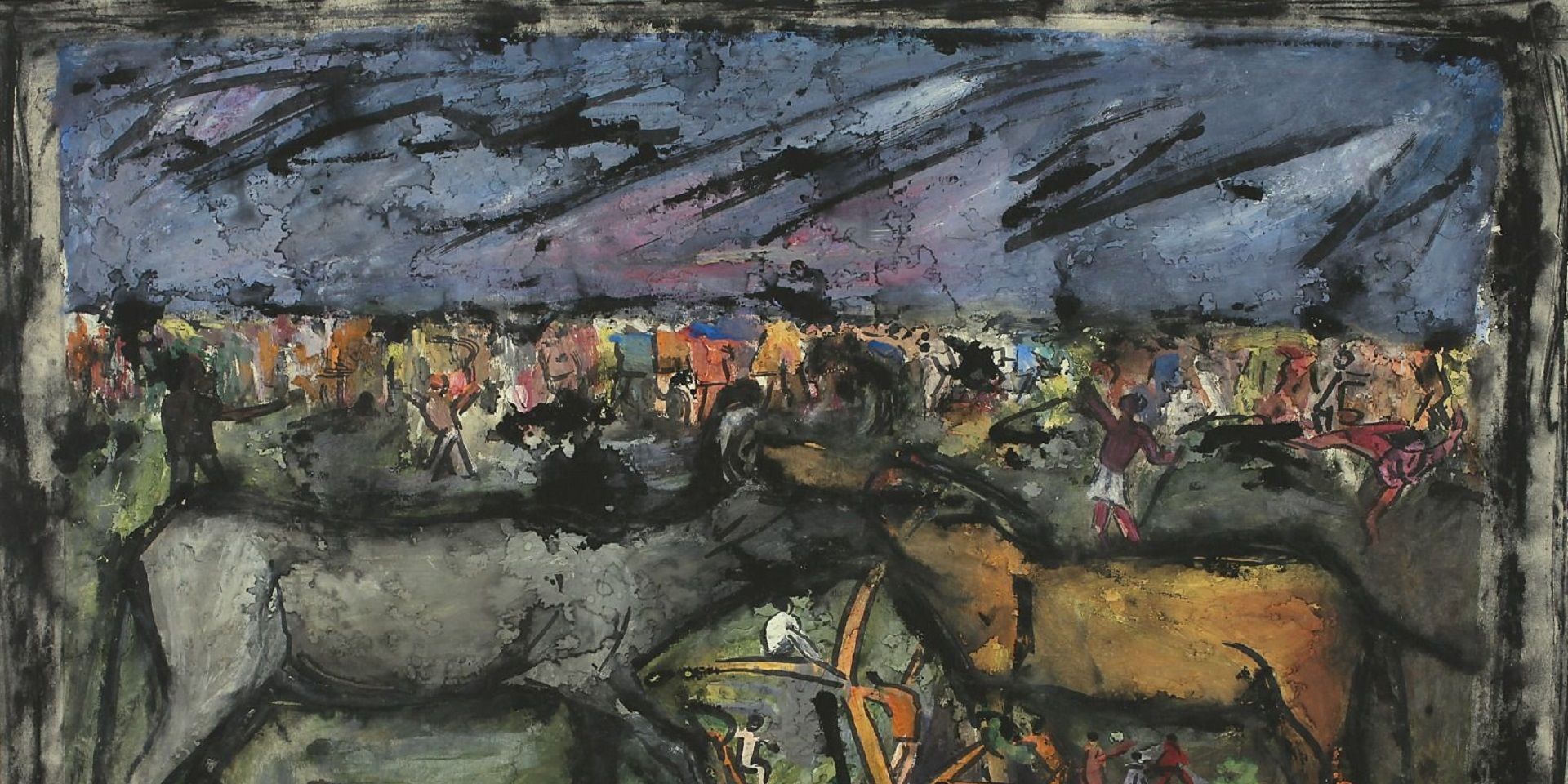

Sugata: Rabindranath typically took a talented cohort of intellectuals and artists with him on his travels overseas. Among artists Mukul Dey accompanied him in 1916, Nandalal Bose in 1924, and Suren Kar in 1927. Like all truly great artists Nandalal had many different phases in his illustrious career. In China he was able to interact with great artists including Qi Baishi, who M. F. Husain would later describe as the Matisse of Asia. He was introduced to the masterpieces of Japanese art by none other than Yokoyama Taikan. In 1943 Nandalal depicted the great Bengal famine in Annapurna and Rudra in a combination of tempera and Japanese wash. Later in the early 1960s he adopted the Japanese sumie style to portray the Indian countryside.

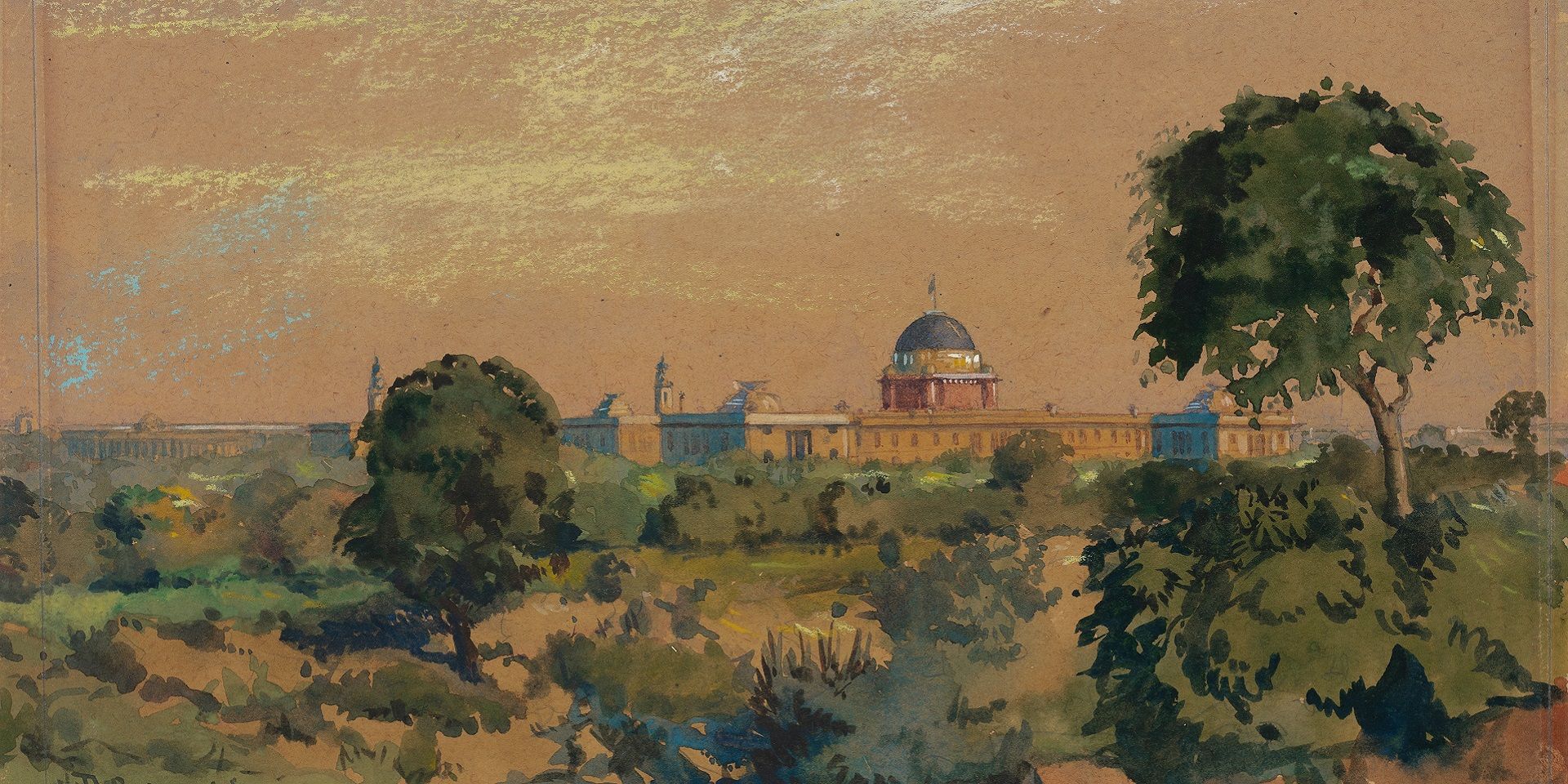

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, 1948, Watercolour on card, 3.7 x 5.7 in. Collection: DAG

Q. During moments of critical pressure or strain, when political ties between colonized India and its Asian cohorts like China or Japan were invariably mediated by larger imperial-global forces, whether war (including Japan’s own imperial aggressions) or global depressions, how were these cultural ties maintained or held on to?

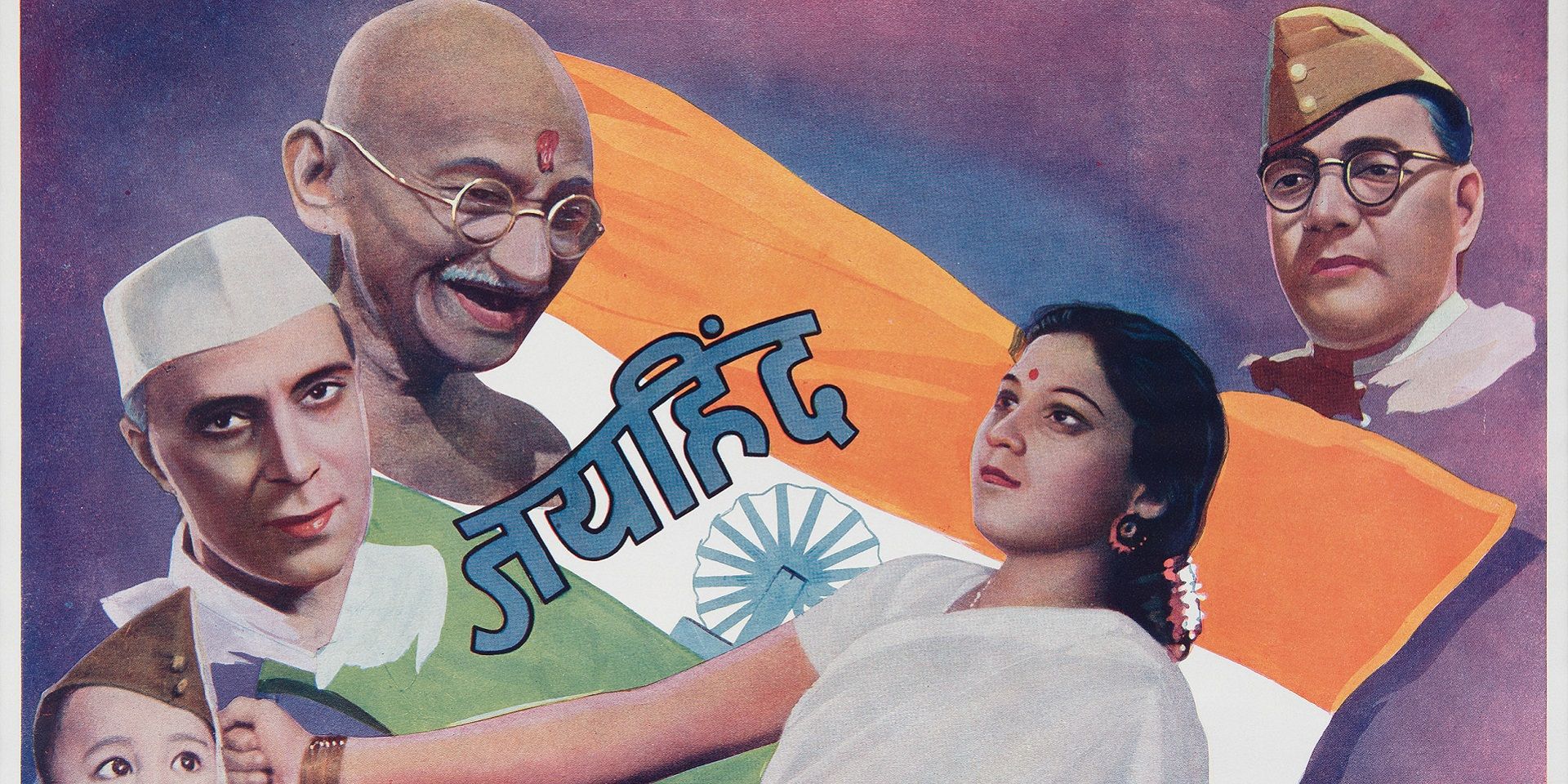

Sugata: Nationalist conflicts and wars were never fully able to disrupt artistic and cultural conversations even though I do discuss ruptures in friendships, for example, between the poets Tagore and Noguchi in the late 1930s. It is significant that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose chose to visit the Ueno Museum of Art in Tokyo during World War II. After the war perhaps the best justification for nurturing the ties came from Takeuchi Yoshimi, a Japanese scholar of Chinese literature, in his 1960 lecture ‘Asia as Method’ in which he urged Asian countries to ‘transcend the confines of nation and state to jointly address particularly urgent issues’.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, Ink on postcard. Collection: DAG

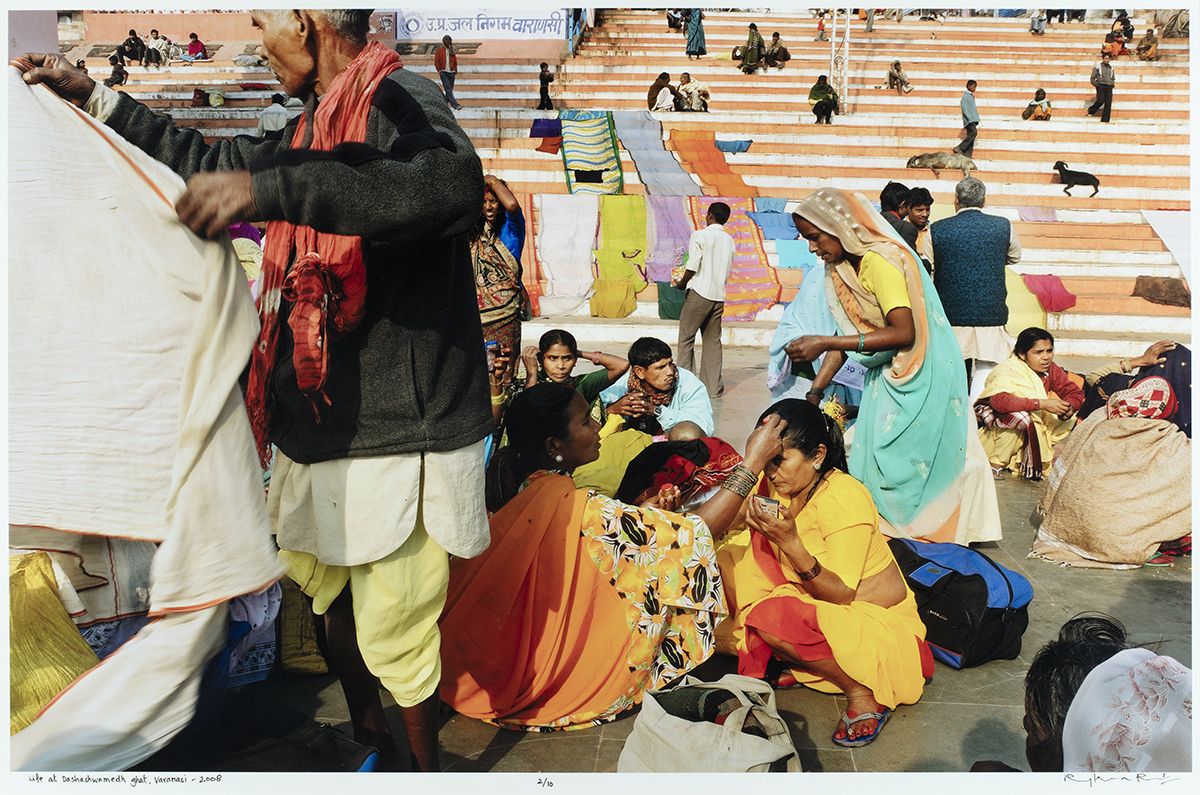

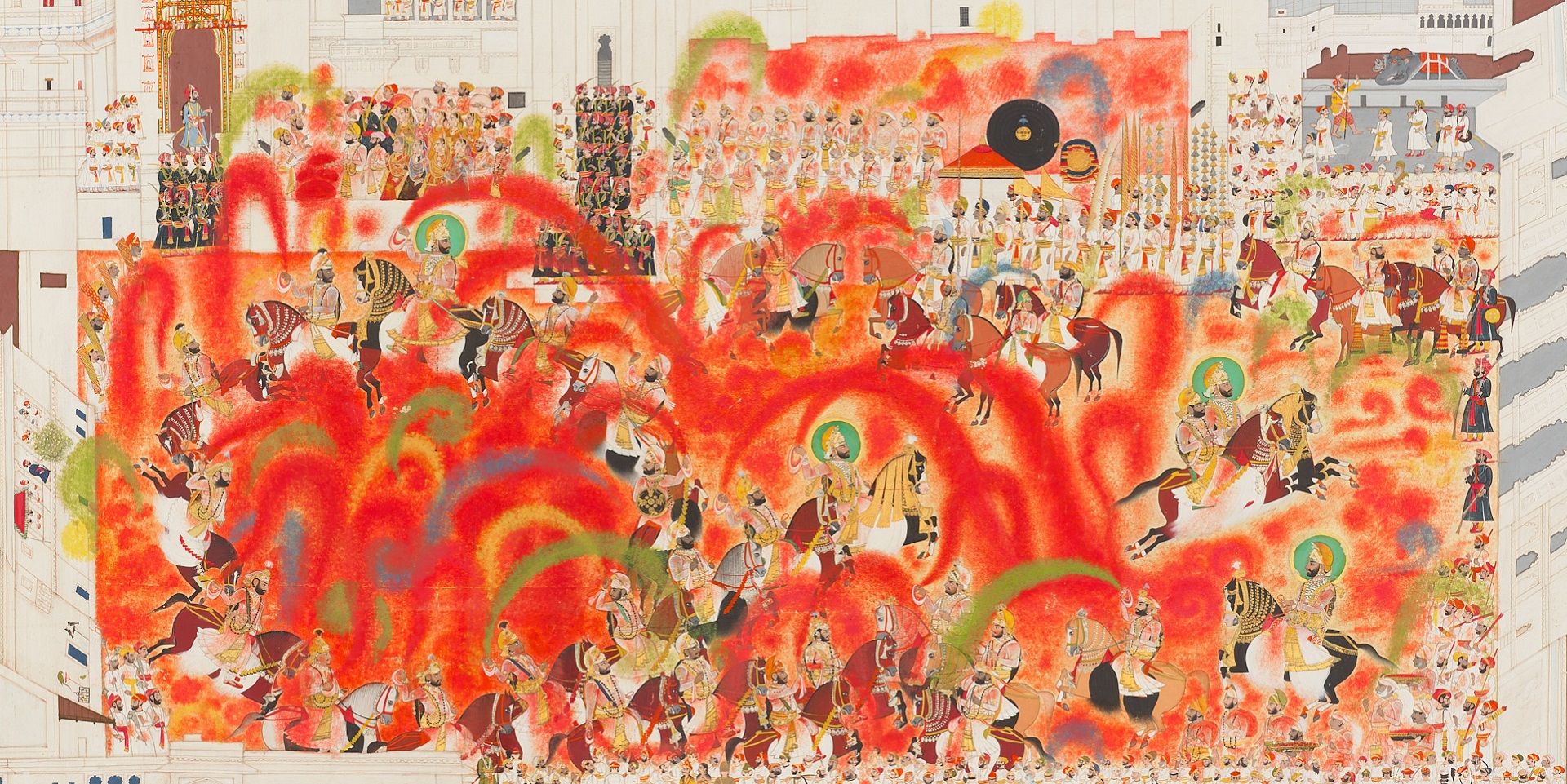

Q. In the post-independent era, you write about a few almost abortive attempts to maintain pan-Asian networks of cultural influence, sometimes even after wars were fought between nations like India and China. The Asian Relations Conference of 1947 featured an exhibition that showed works by Asit Haldar, Jamini Roy, A. R. Chughtai and Abanindranath, among others. Do we know how visitors reacted to this show or what narratives curators tried to draw from these ‘inter-Asian’ cultural products then? How different were they to the exhibition agendas you write about in Japan’s Fukuoka Art Museum in 1979-1980 and the later 30th anniversary show that was titled ‘Under Construction: New Dimensions of Asian Art’?

Sugata: I would not say the efforts to nurture cultural connections were abortive. They had to contend with the political obsession of nation-states with borders. There is scope for more research into the reception of the art exhibition featuring more than 200 paintings at the Asia Relations Conference of 1947. What I have found is that a Kakemono painting of ‘Fish’ was immensely popular even though the United States ensured that Japan could not even be invited to that conference. The later exhibitions from 1979 onwards were part of efforts to reconnect Asia. Earlier cultural theorists and art critics were invoked. Okakura was an inspiration behind the 1979 exhibition in Fukuoka while in 2002 Takeuchi Yoshimi served that role in Tokyo.

Q. Recent years have also seen energetic efforts to craft pan-Asian sentiments, mostly by China with a semi-imperial vision towards geopolitical control. We are also seeing the growth of art markets in Southeast and East Asian regions, as European markets shrink in the post-pandemic period. How do you see culture playing a critical role in this new era? And what role do Southeast and East Asian nations play in this new cultural landscape, especially in relation to the Indian subcontinent?

Sugata: In my book’s conclusion I ask what kind of China is now rising and what the implications of China’s nationalistic imperialism might be for the more generous imaginaries of Asian universalism. There are new stirrings in domains of economy and culture in Indonesia and Vietnam, even though the current sorry state of Myanmar has been hampering plans for greater Asian connectivity. South Korea has been fashioning new styles of Asian music and film that have strong appeal across the continent including India, especially among the younger generation.

|

S. N. Kar, Untitled, 5.5 X 3.5 in. Collection: DAG |

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025