Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

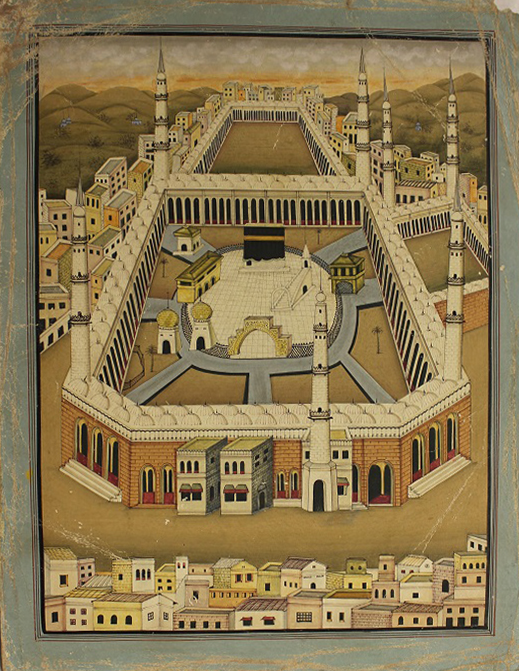

Anonymous, A Panoramic View of Mecca (Ka`aba and the Masjid al-Haram) (detail), 1890, Gouache and ink on paper, 35.6 X 44.5 cm. Collection: DAG

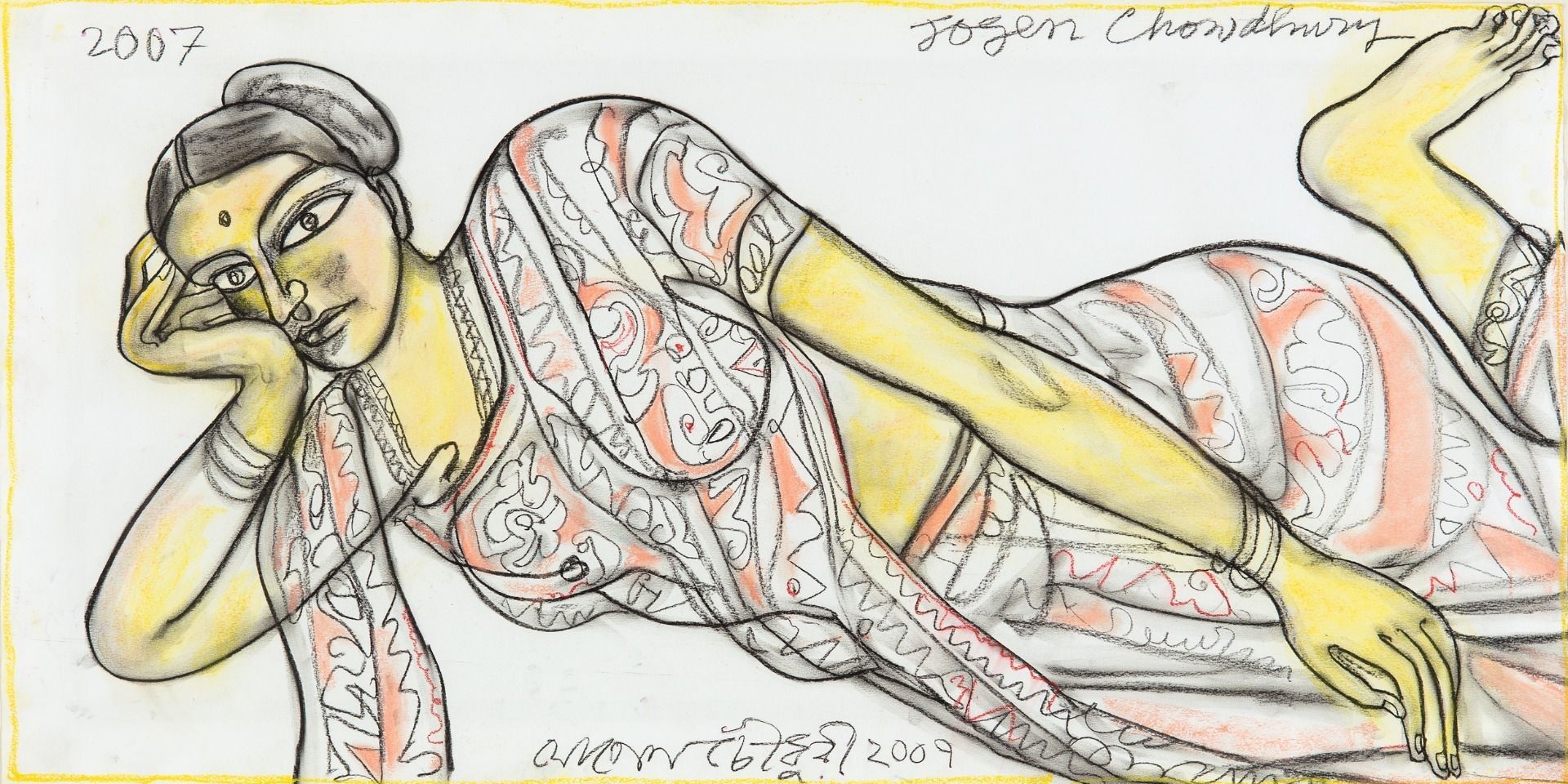

Filmmaker, author and archivist Yousuf Saeed is the project director (and founding member) of Tasveer Ghar (along with the academics Christiane Brosius and Sumathi Ramaswamy). His book, Partitioning Bazaar Art: Popular Visual Culture of India and Pakistan Around 1947, published as a part of Seagull Books’ History for Peace series, recounts the context and material history of popular (or, ‘bazaar’—meaning market) art that catered to a wide variety of consumers across the Indian subcontinent, from various faiths and political dispensations.

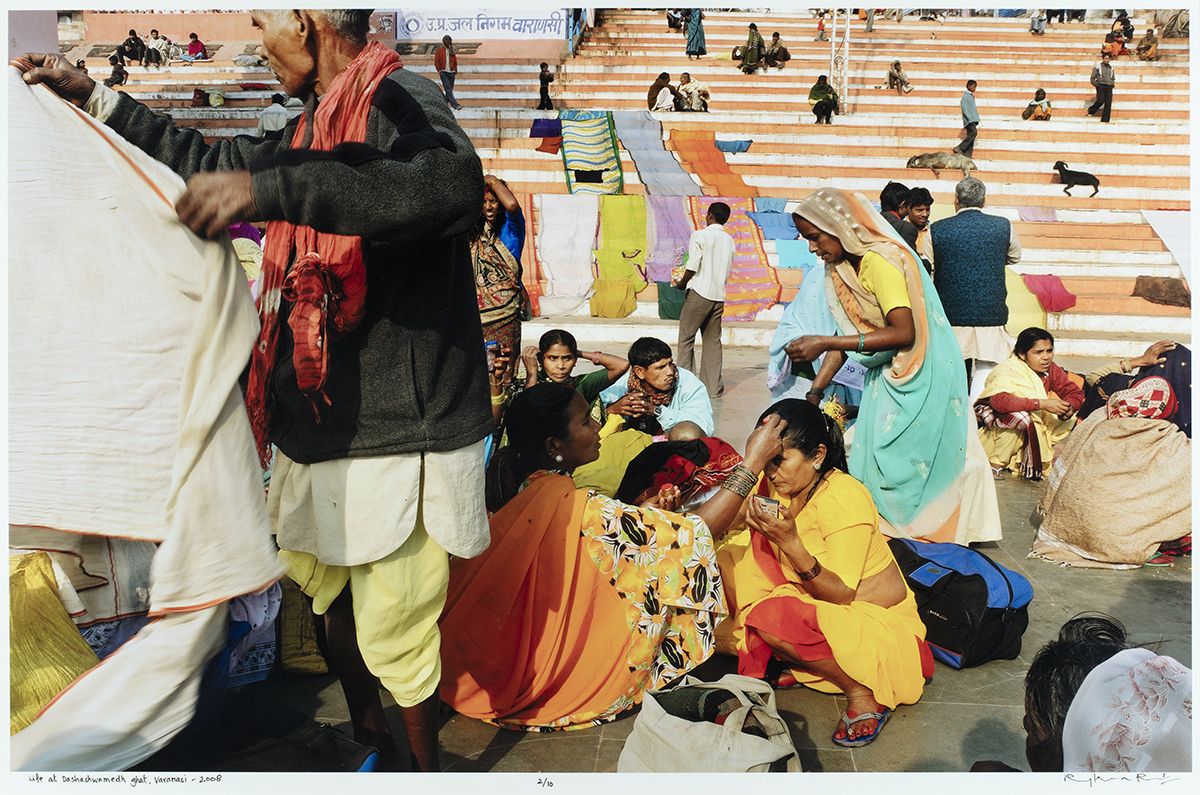

As the Indian nationalist movement gained currency in the popular imagination, the decades of the 1940s and ‘50s saw these themes being increasingly adopted for posters, calendars and almanacs—ephemeral art objects that offer a view into popular consciousness. Within this wider context, Saeed’s book also highlights the impact of partition on this network of printers and publishers, and the general absence of Islamic political themes and imagery in these works, while pointing out its prevalence in depicting more generic, devotional subjects. He discussed his book and the Tasveer Ghar archive with the editors of the DAG Journal.

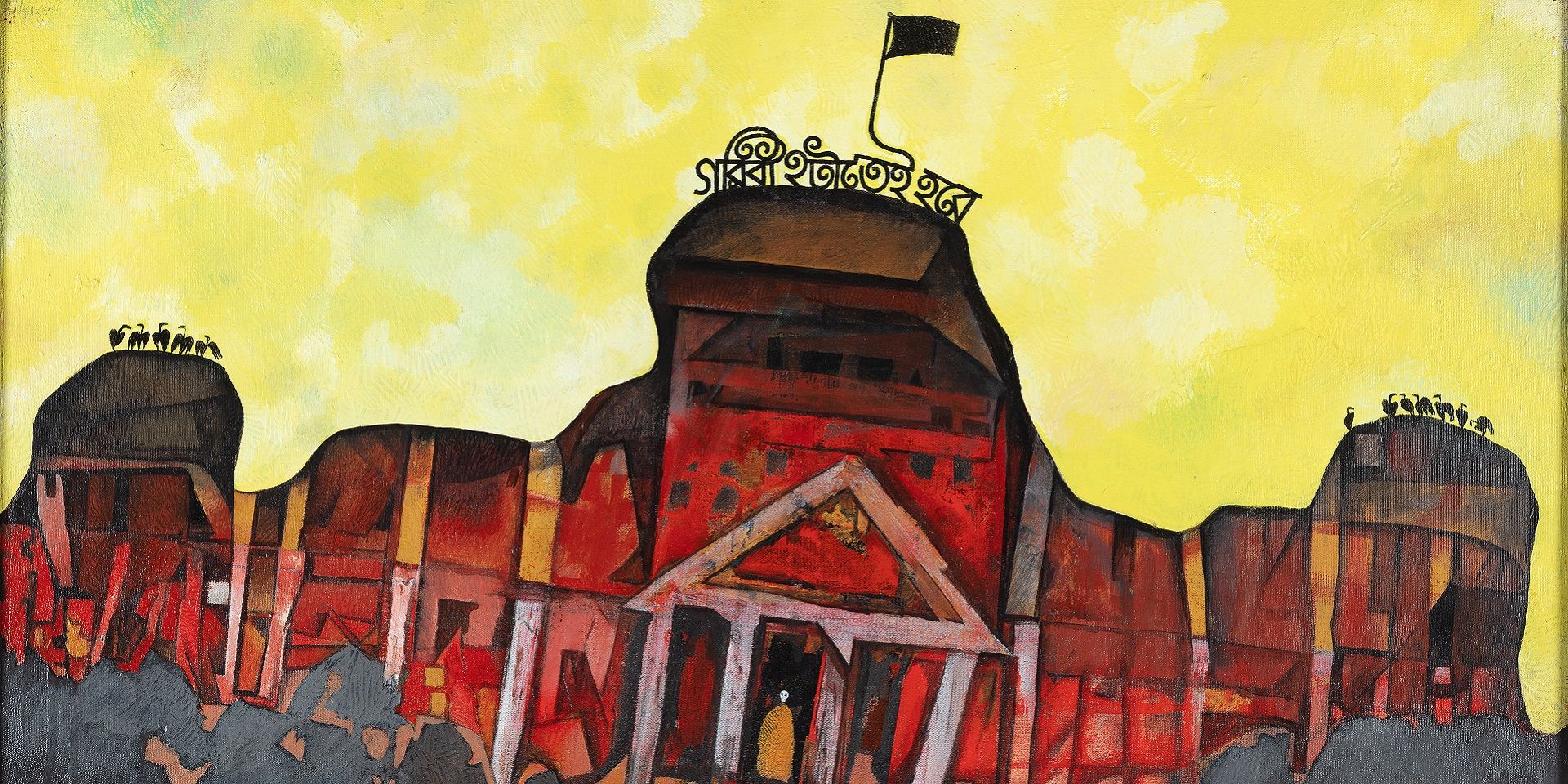

Q. What were some common themes and symbols adopted by Muslim artists for popular artistic representations in the 1940s and 50s? How did this negotiate with strictures against representing the human form in Islam?

Yousuf Saeed: First and foremost, let's consider the industry responsible for producing calendars and posters. It's not confined to a specific religious group; rather, it involves the same individuals and publishers catering to both Muslim and Hindu communities. The artists and publishers work for both groups, creating images for Muslims and Hindus alike.

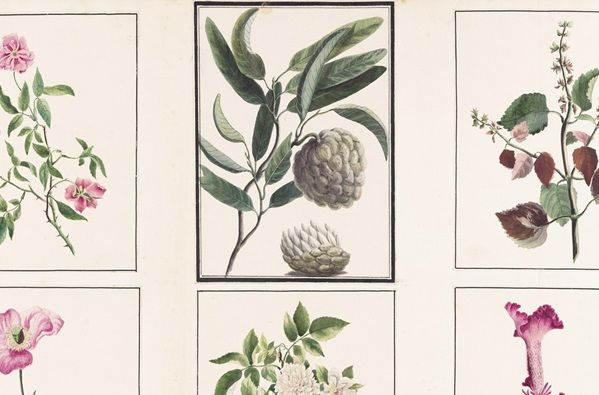

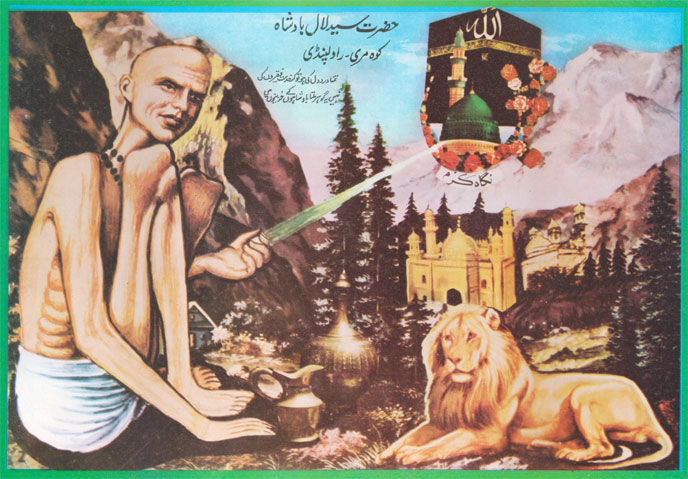

In the case of Islamic imagery, the predominant subjects include Mecca, Medina, and various shrines. Notably, these images tend to avoid the depiction of human figures, as some Muslims prefer not to use such representations. Hence, they have refrained from including such depictions, although occasional exceptions exist, such as a few images showcasing Sufi saints. An instance of this is a depiction featuring six Sufi saints, a theme with historical precedence in miniature painting dating back to the Mughal era. This particular composition has been reimagined by a calendar artist, adhering to a specific interpretation. However, aside from these instances, there are few representations of other human figures in these artworks.

Anonymous, A Panoramic View of Mecca (Ka`aba and the Masjid al-Haram), 1890, Gouache and ink on paper, 35.6 X 44.5 cm. Collection: DAG

During my visit to Pakistan in early 2005, however, I noticed a difference in the approach towards depicting human figures in comparison to India. In Pakistan, there seemed to be a greater abundance of such images, reflecting less of a concern within the industry about potential sensitivities. In contrast, in India, where a significant portion of publishers is Hindu, there is a conscientious effort to avoid offending anyone's sensibilities. This careful approach is particularly evident in the domain of religious imagery.

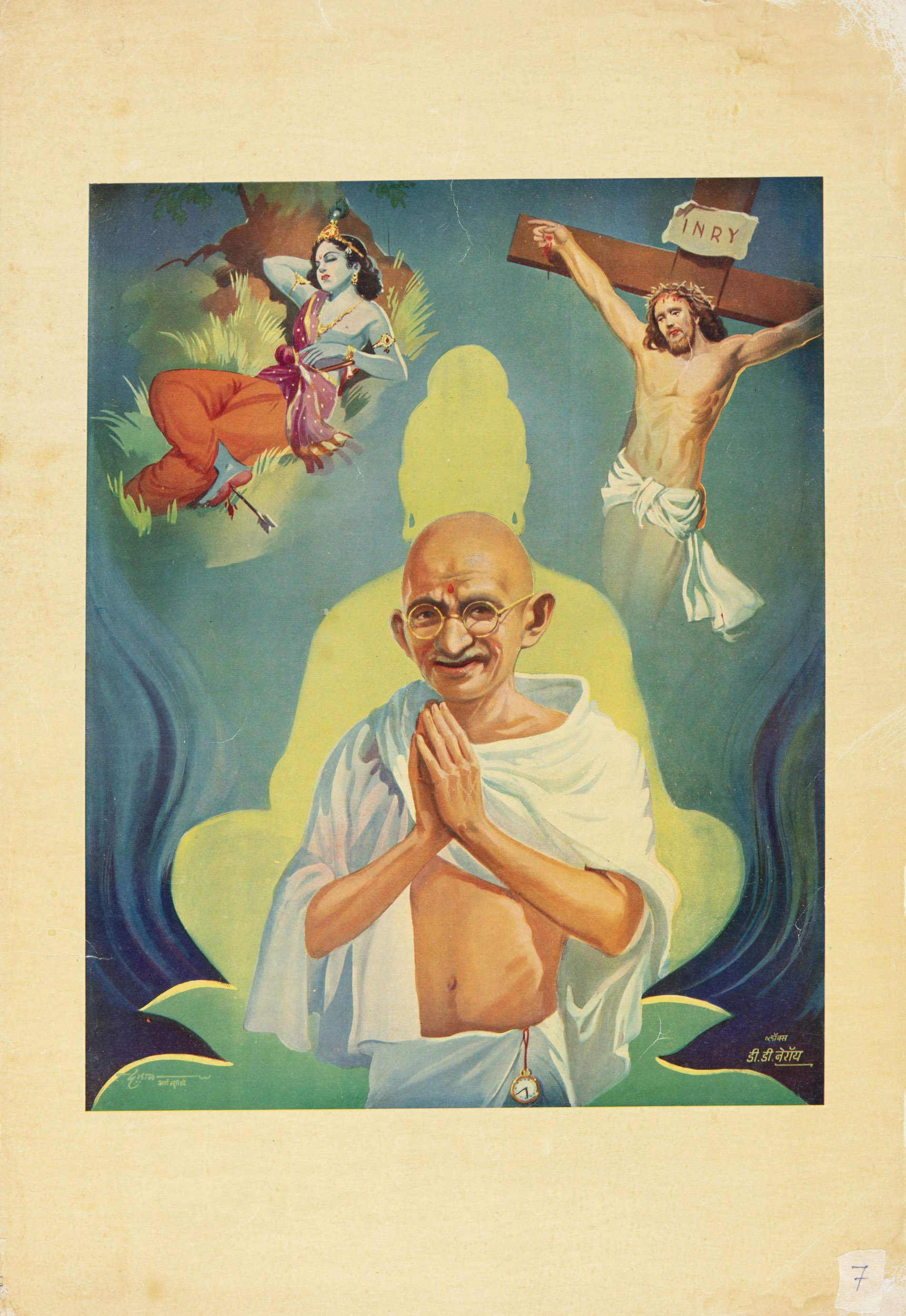

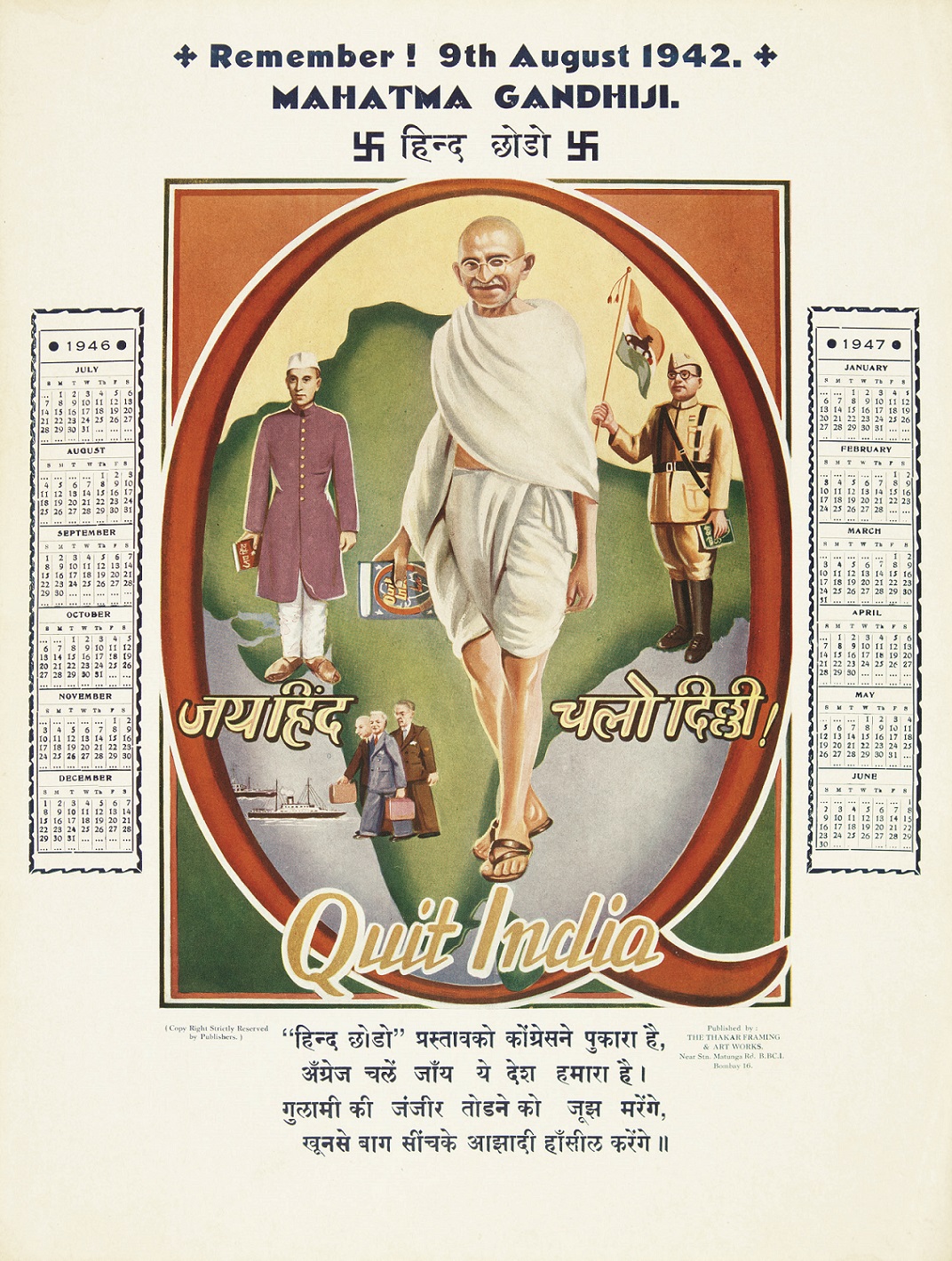

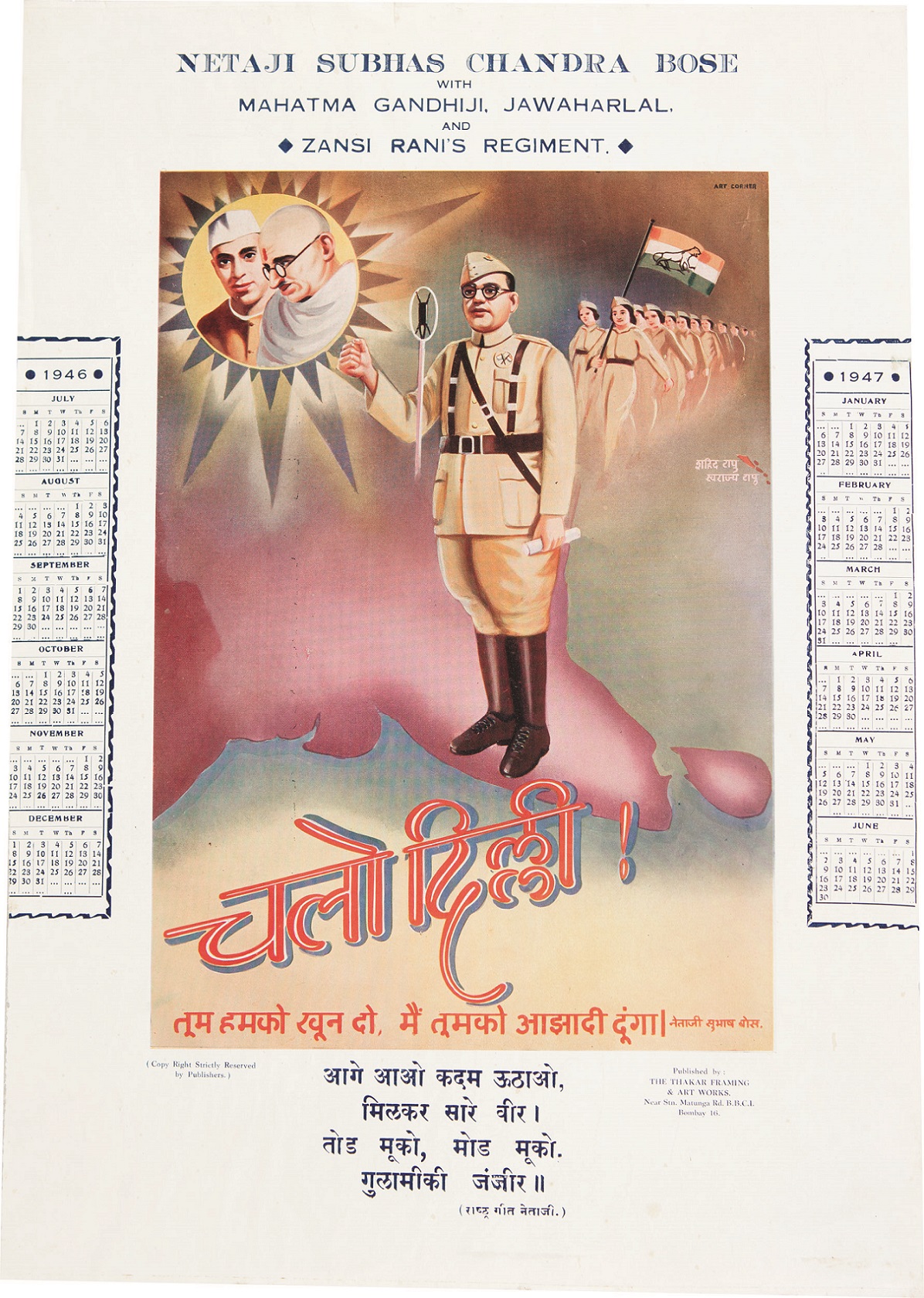

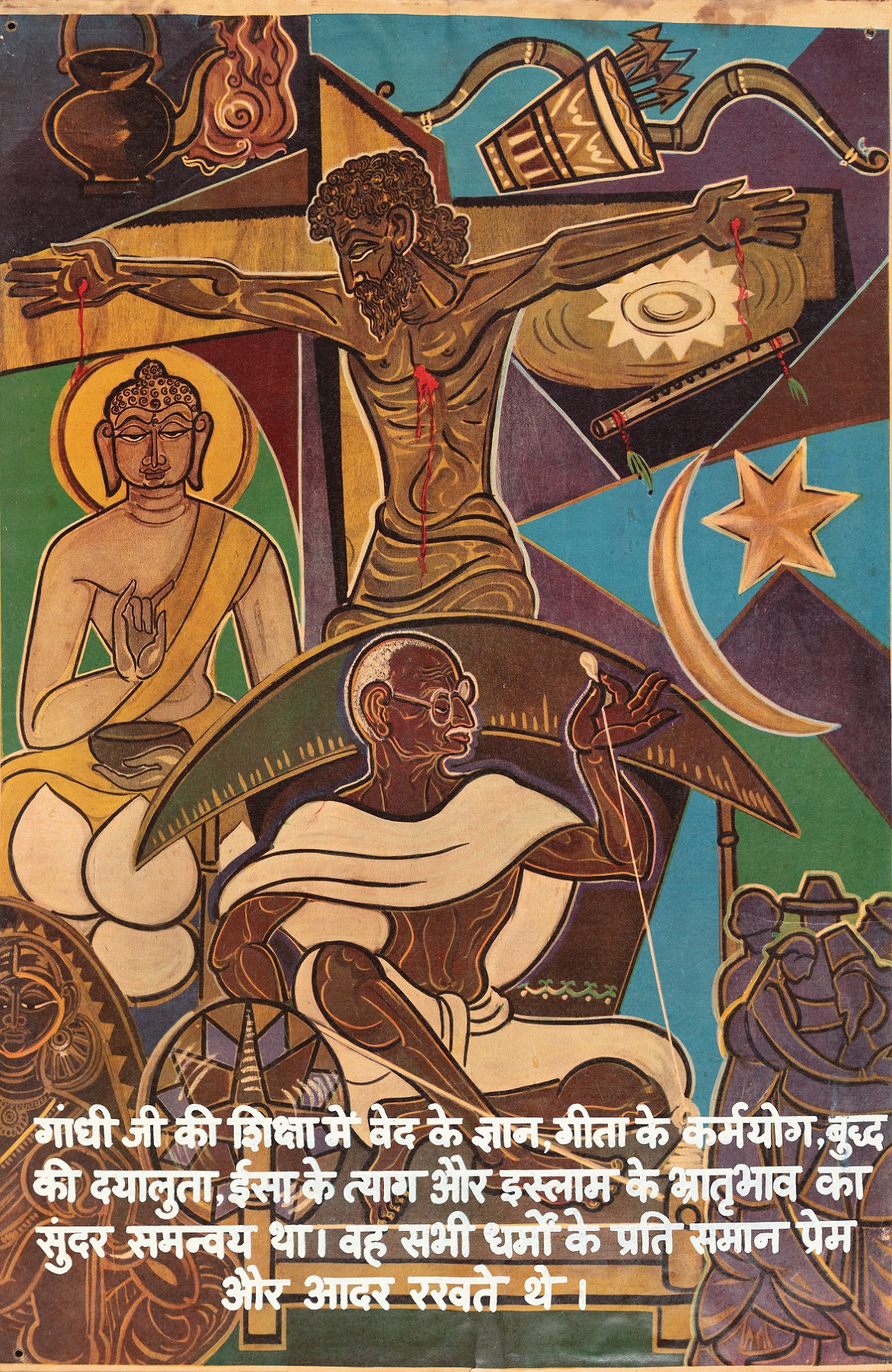

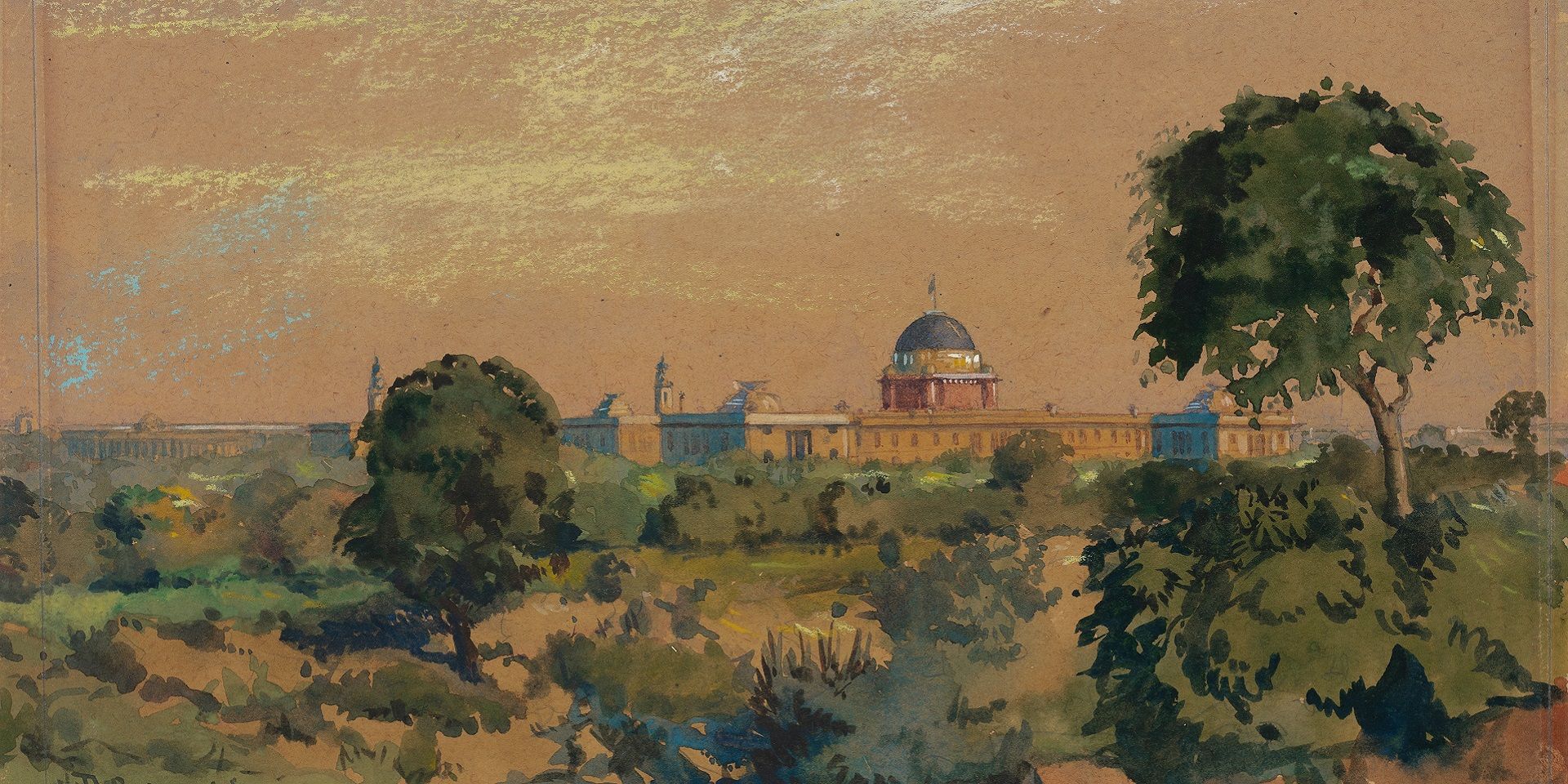

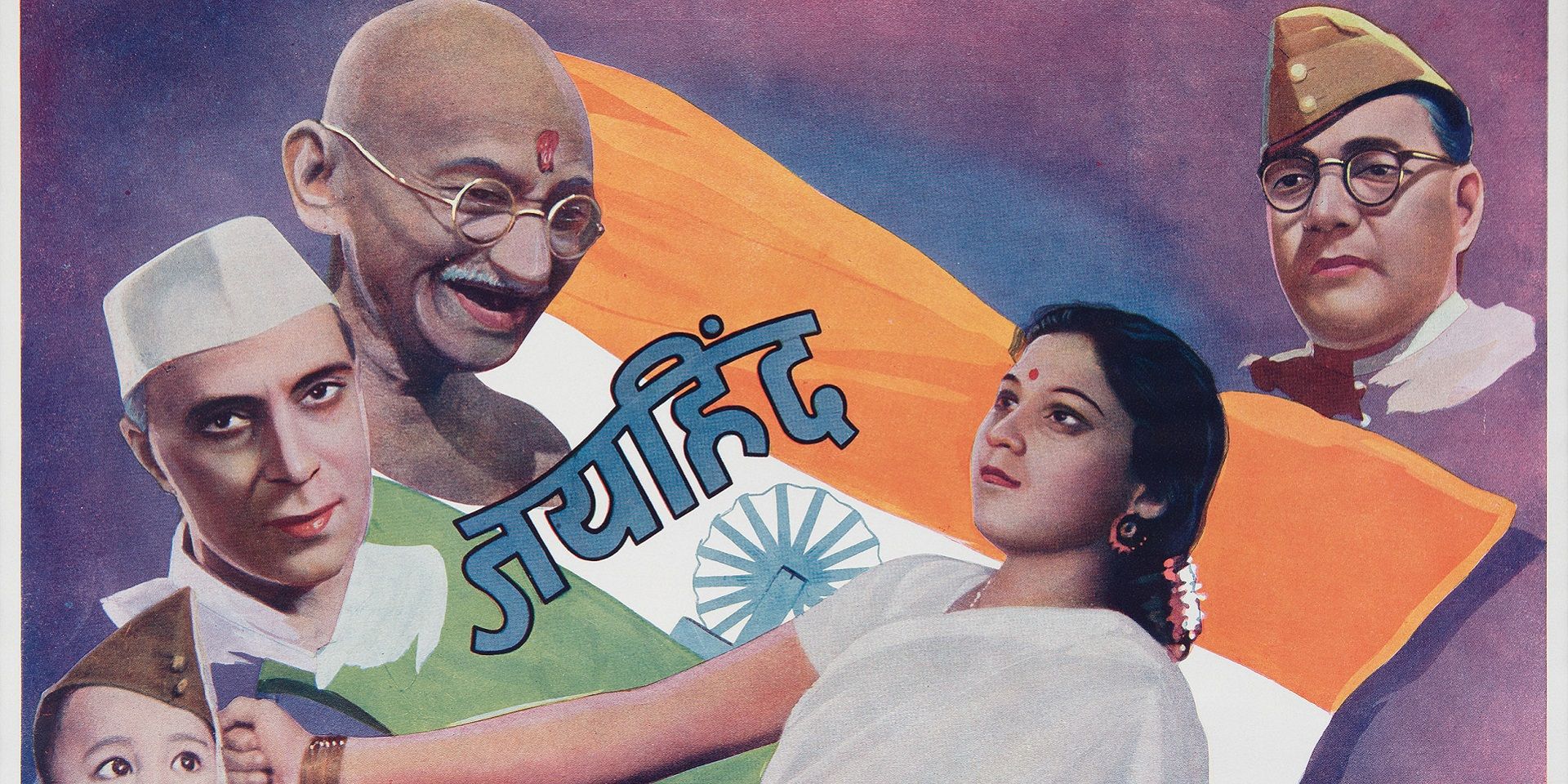

As explored in my book, Hindu imagery often conveys a sense of nationalism by intertwining Hindu religious revivalism with patriotic sentiments. A notable example is the depiction of Bharat Mata, or Mother India, alongside other Hindu freedom fighters and leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru. This fusion of religious and nationalistic themes is a prevalent feature in Hindu visual representations.

In contrast, Islamic images, particularly those used before the 1940s or around the 40s and 50s, typically lack political content. Unlike Hindu imagery, Islamic depictions during this period seldom incorporate political themes, maintaining a focus on religious and cultural elements without intertwining with political narratives.

|

Anonymous, A view of Mecca, India, c. 19th century, Opaque pigments on heavy paper, between polychrome rules and minor borders, 33.0 X 25.4 cm. Collection: DAG |

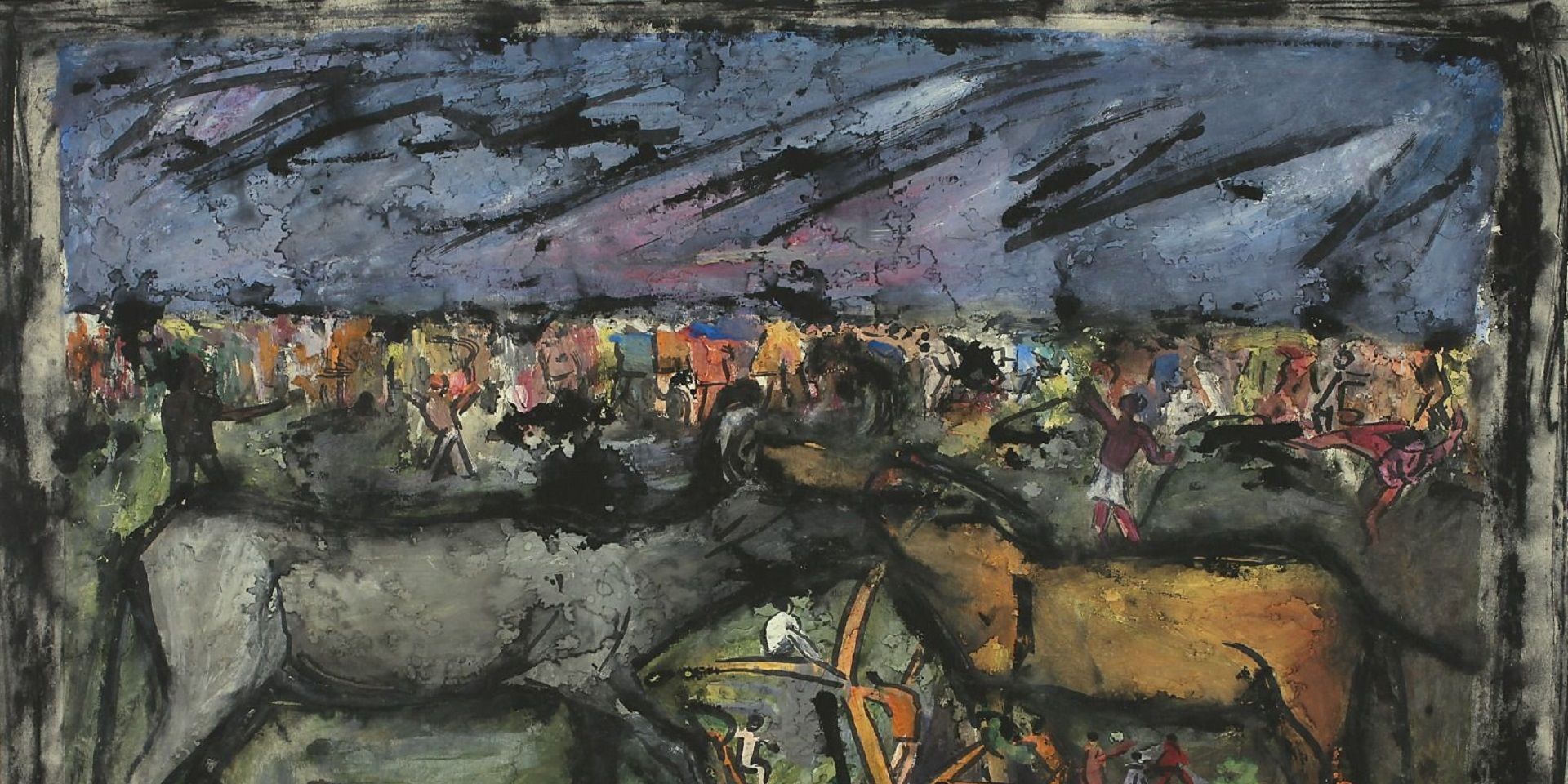

Q. As Hindu revivalist tendencies made their way towards shaping the central agenda of the nationalist movement, how did Muslim popular artists respond visually to their own absence from these narratives?

Yousuf: I’m not sure if this was a major concern back then because there are hardly any records of people commenting on these images during that period. Sadly, these images, including posters and calendar art, weren't taken seriously at the time of their production, and there was minimal effort to preserve them. It’s more recently that art historians and other scholars have started examining them, identifying their content and analysing their significance. Some have started talking or writing about how these images portrayed Indian nationalism.

If you look at the publishers involved in creating these artworks you can see a clear emphasis being laid on depictions of Indian nationalism. The publishers viewed Hindu buyers as a more significant market compared to Muslims. Regarding imagery, depictions of Bharat Mata often included not only living freedom fighters but also religious figures like Jesus Christ and Buddha. While Hindu deities were featured, there was a notable absence of Islamic representations. This absence may have stemmed from concerns about selecting appropriate Islamic figures for inclusion in these visuals.

|

Anonymous, Untitled, Off set print on paper, 50.8 X 35.6 cm. Collection: DAG |

In an interview with M. L. Garg, the owner of Brijbasi Press, I asked him about their approach to Islamic imagery. Garg pointed out the challenge in representing Islam, due to the sensitivity around depicting Prophet Muhammad or any significant Islamic figure. This constraint led to a notable limitation, preventing the inclusion of Islamic figures alongside representations of other religious figures.

Certainly, it's possible to find creative ways to portray subjects, yet there remains a disparity in the representation of Muslim freedom fighters (as well). While posters prominently feature figures like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, and Subhas Chandra Bose, Muslim freedom fighters, especially Maulana Azad, are rarely depicted. In contrast to the imagery of other freedom fighters offering their heads to Bharat Mata, Maulana Azad and other Muslim freedom fighters are seldom portrayed in similar scenarios. The absence of such depictions underscores a distinctive pattern in the portrayal of different communities within the artistic narrative.

There exists a cautious approach among publishers, evident in their deliberate exclusion of numerous Muslim freedom fighters from the overarching theme of Indian nationalism. Despite the presence of hundreds of Muslim freedom fighters, they are rarely portrayed within this context. Occasionally, individuals like Captain Shanawaz make appearances in informative posters that provide details about their contributions. These informative posters, distinct from the vibrant artistic ones, serve as a different category, presenting factual information about various figures. This nuanced distinction reflects a deliberate choice in the portrayal of Muslim freedom fighters in visual narratives.

Q. Popular posters incorporate different techniques of image-making, like collage, painting, use of archival or contemporary photographs, tonally bright colours and articulated forms and panel-divisions, among others; what are some of the distinctive material features of such posters? And how do you see their value changing over time as art history, at least since the 1990s, has started to accommodate bazaar prints into their remit of acceptability?

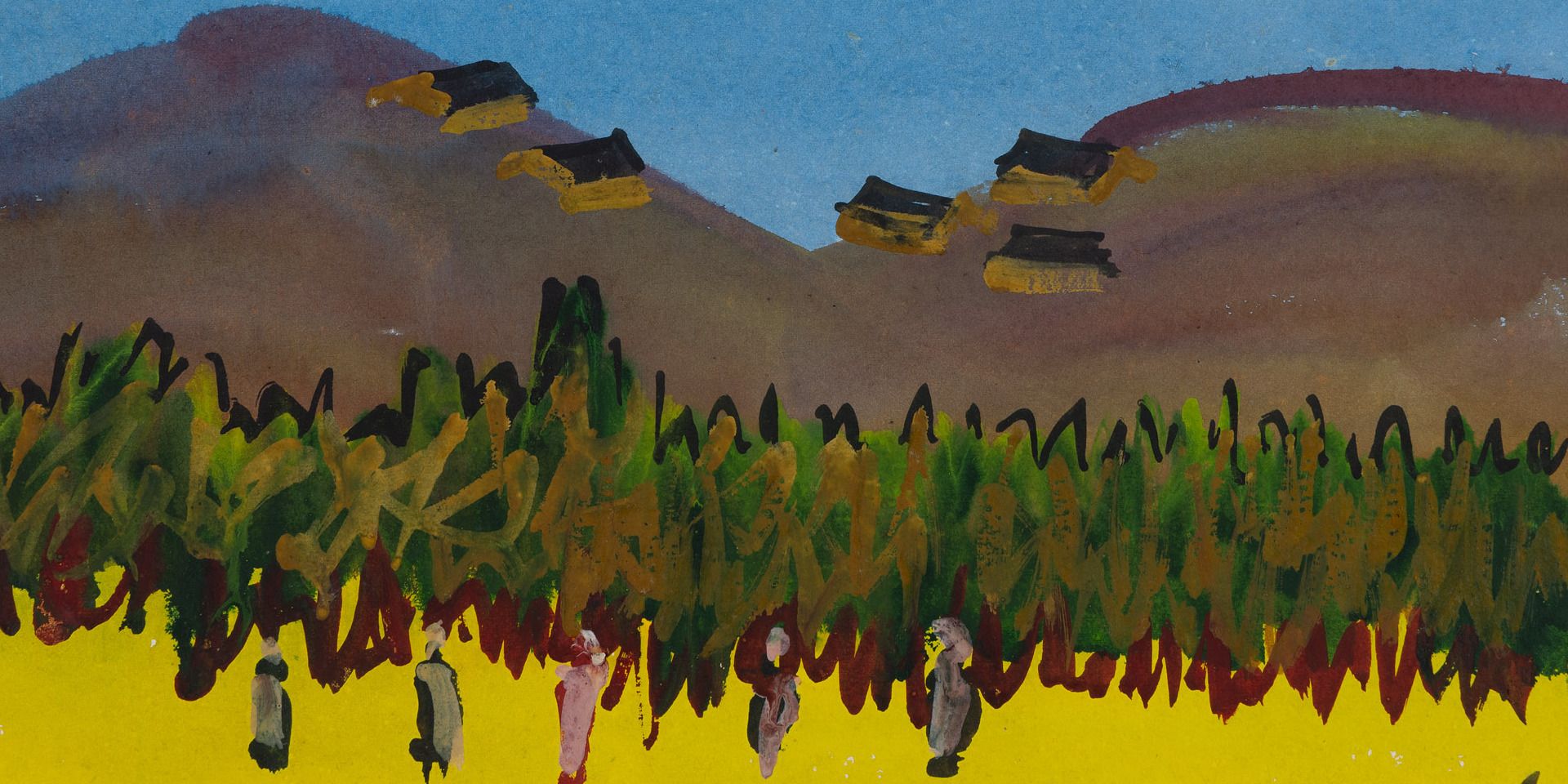

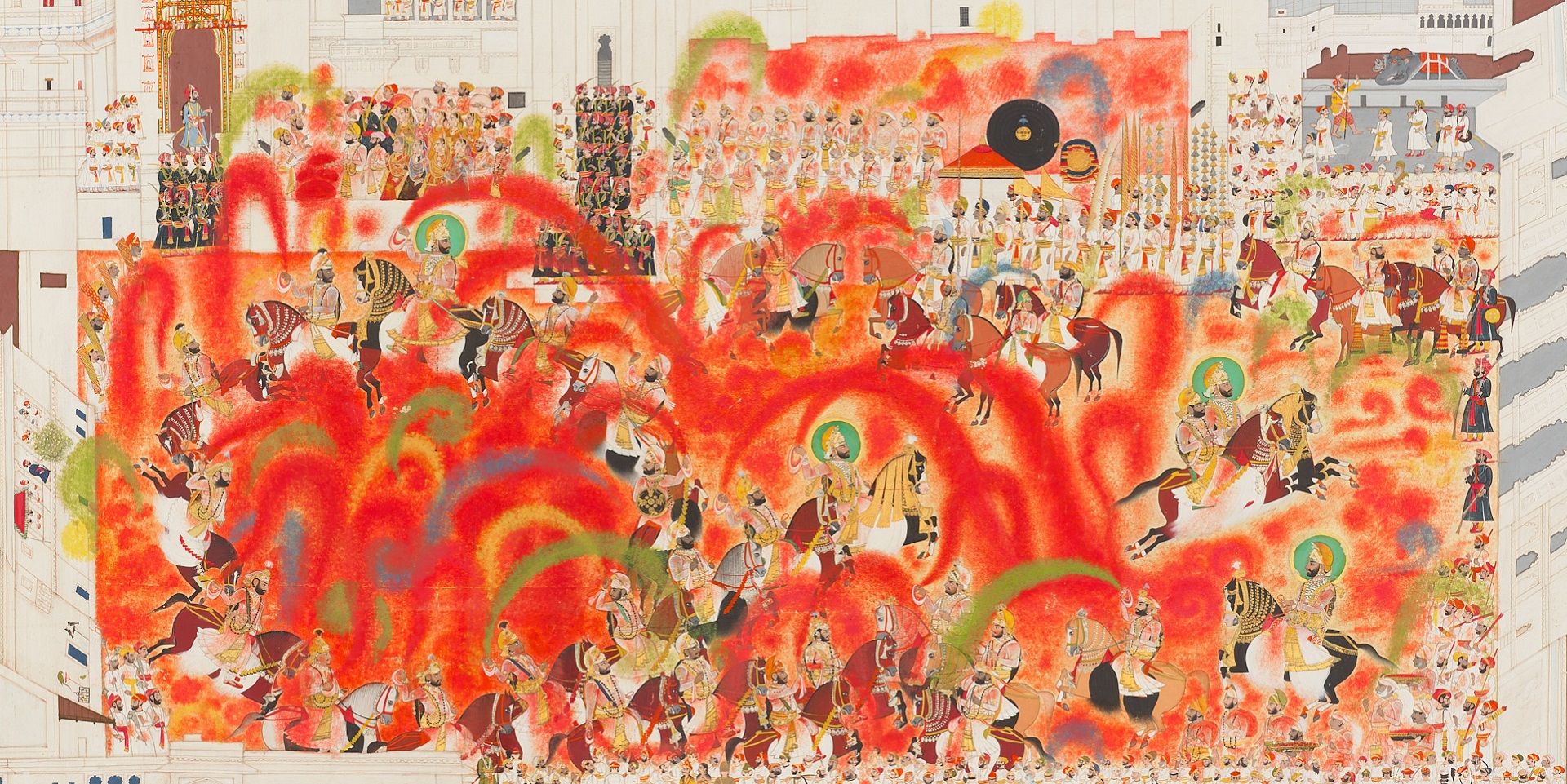

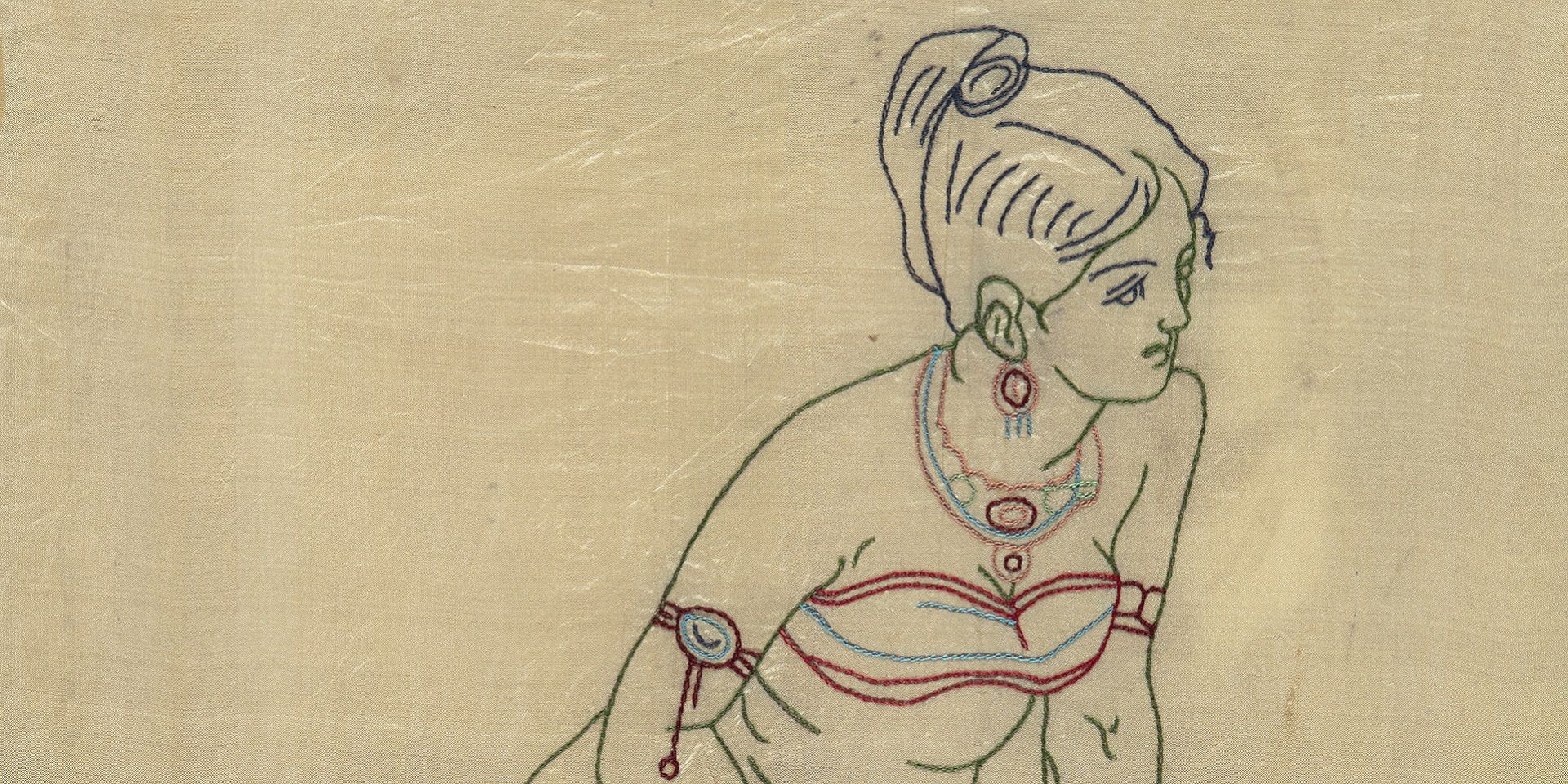

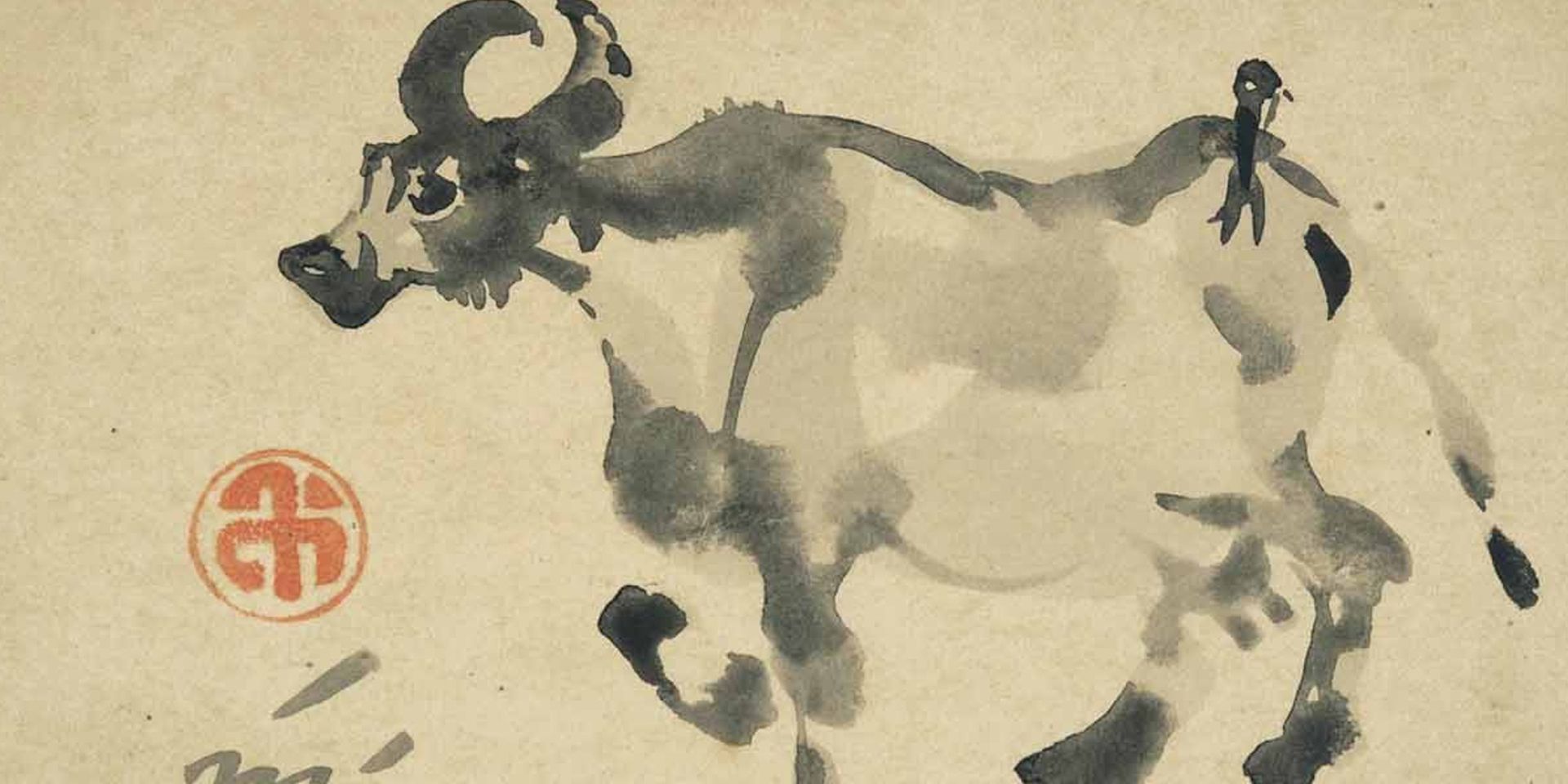

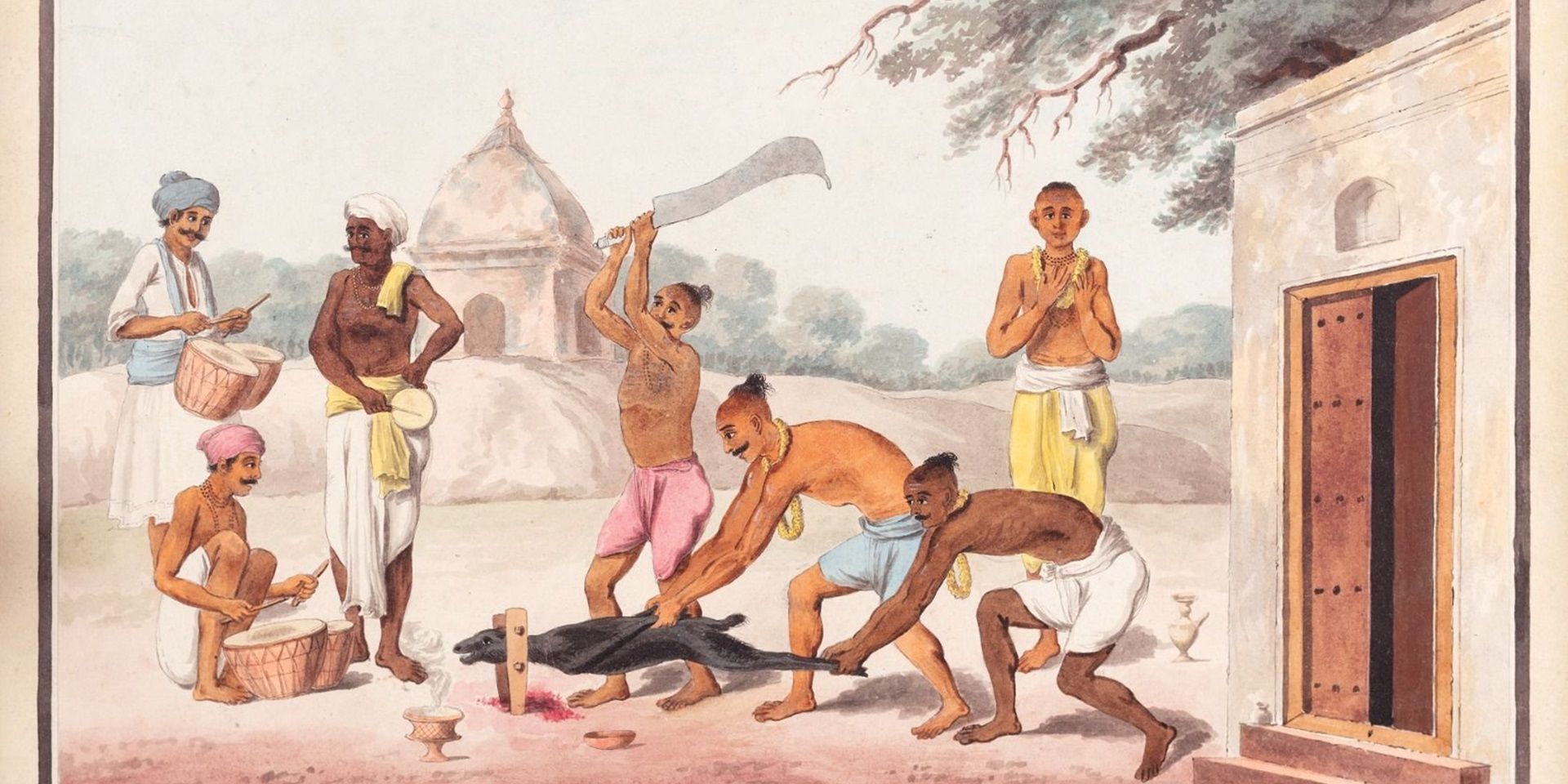

Yousuf: Prior to the 1940s and 50s, the art style commonly referred to as Bazaar art had not fully emerged. During this period, artists were primarily engaged in creating traditional paintings, showcasing their skills and a distinct sense of beauty and aesthetics. These early images exhibit a unique charm, with meticulous attention to the aesthetic qualities, particularly in the portrayal of human figures.

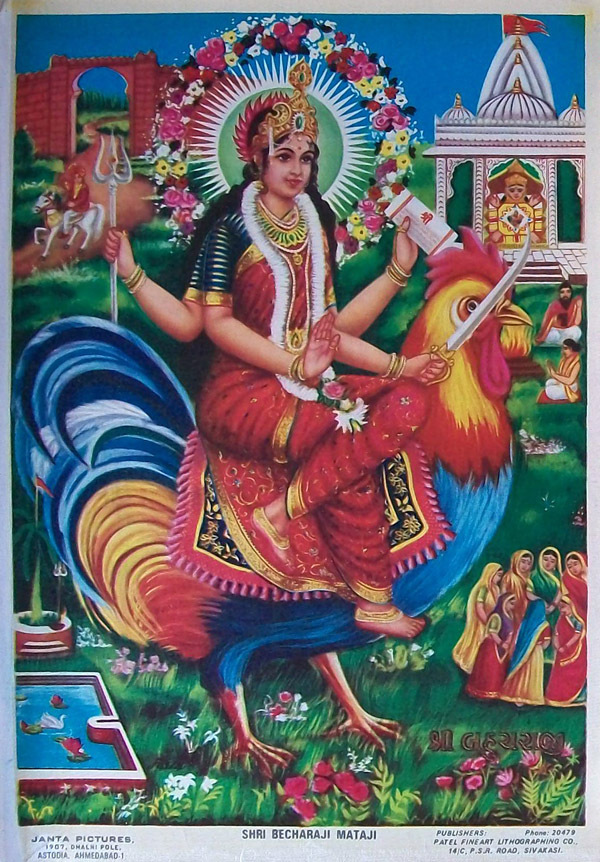

The evolution of the Bazaar art style took place later, especially in the post-1950s era. Sivakasi in Tamil Nadu played a pivotal role in this evolution, emerging as a central hub for printing. The development of specific printing techniques and the use of particular colours contributed to the distinct characteristics of the Bazaar art style.

|

A poster made at Sivakasi, featuring the Bahuchara Devi. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

In fact, Kajri Jain extensively discusses in her work (Gods in the Bazaar) how publishers employed consistent techniques and colours to enhance the attractiveness of posters. The utilization of specific colour saturation methods played a crucial role in making these posters visually compelling, resulting in widespread consumer appeal and increased sales. However, it's worth saying that until the 1930s and 40s, the techniques were still in their nascent stages, with chromolithography representing just an initial step in the development of these artistic processes.

The printing presses that were being used were not originally Indian; instead, they were imported from Germany and other places, leading to numerous experiments. In my interpretation, efforts were made to maintain the fidelity of the original painting during the printing process. However, in Sivakasi, additional enhancements were applied to the painting, so that the final product that reached the market differed slightly from the original, featuring richer colours, heightened colour intensity, and a vibrant, shiny appearance. Additional steps, such as laminating the paper, were taken to increase the overall attractiveness of the printed images.

Conversely, when examining prints created before the 1940s, those that have endured until today often display faded colours and a more aged, yellowed appearance. Determining the exact original colours becomes challenging here. Up until the 1950s there was minimal interference with the initial creations. However, in contemporary times, there is a prevalent trend of recycling and rehashing, with publishers frequently repurposing older paintings. This involves processes like photoshopping, suggesting a shift from the earlier emphasis on maintaining the sanctity of the original artwork.

|

Anonymous, Untitled, Serigraph and off set print on paper, 45.0 X 34.8 cm. Collection: DAG |

Furthermore, since we are discussing the context of partition, I've also examined prints originating from Pakistan. The Pakistani printing industry, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, adopted even cruder practices. Methods included physically cutting paintings from various sources with scissors, pasting them together, and then attempting touch-ups. Additionally, the paper used for printing was predominantly recycled, often sourced from Europe and other locations, with one side already bearing advertisements. This choice was driven by a cost-cutting mindset, reflecting an inclination to minimize investment in the printing process.

I'm also not sure about the compensation provided to the artists for the original prints, but it seems it might not have been substantial. I was recently asked about the presence of artist signatures or bylines. While some artists ensured their names were visible in the paintings, others opted not to include their names, or in some cases, the artist concealed their signature in a small corner or obscure location. Identifying such signatures often requires the discerning eye of an expert familiar with these images.

About the impact of art historical writing and categorisation on the reception and production of popular art:

When I was talking to M.L. Garg, the owner of Brijbasi, he strongly rejected the term ‘calendar art’, expressing displeasure and emphasizing that what they produce is genuine art. He said that any artist creating images for them is considered a contemporary artist, irrespective of their background in billboards, cinema hoardings, or advertisements. They don't perceive their work as confined to a specific style like calendar art or bazaar art; rather, it's a customary approach.

Many artists, some originating from folk art traditions in places like Rajasthan or Bengal, possess the flexibility to adapt to various styles. They may occasionally reference older pictures or photographs in their work. For instance, when creating cinema billboards, artists might employ a grid system to upscale a small photograph onto a larger scale. While art historians often analyse these images in terms of class distinctions—because these works tended to be popular among a specific class or social group—the artists themselves don't think in those terms. For the artists, their creations are contemporary art, not confined to the labels or distinctions imposed by external observers.

|

Anonymous, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose with Mahatma Gandhiji. Jawaharlal, Serigraph and off set print on paper, 47.0 X 34.8 cm. Collection: DAG |

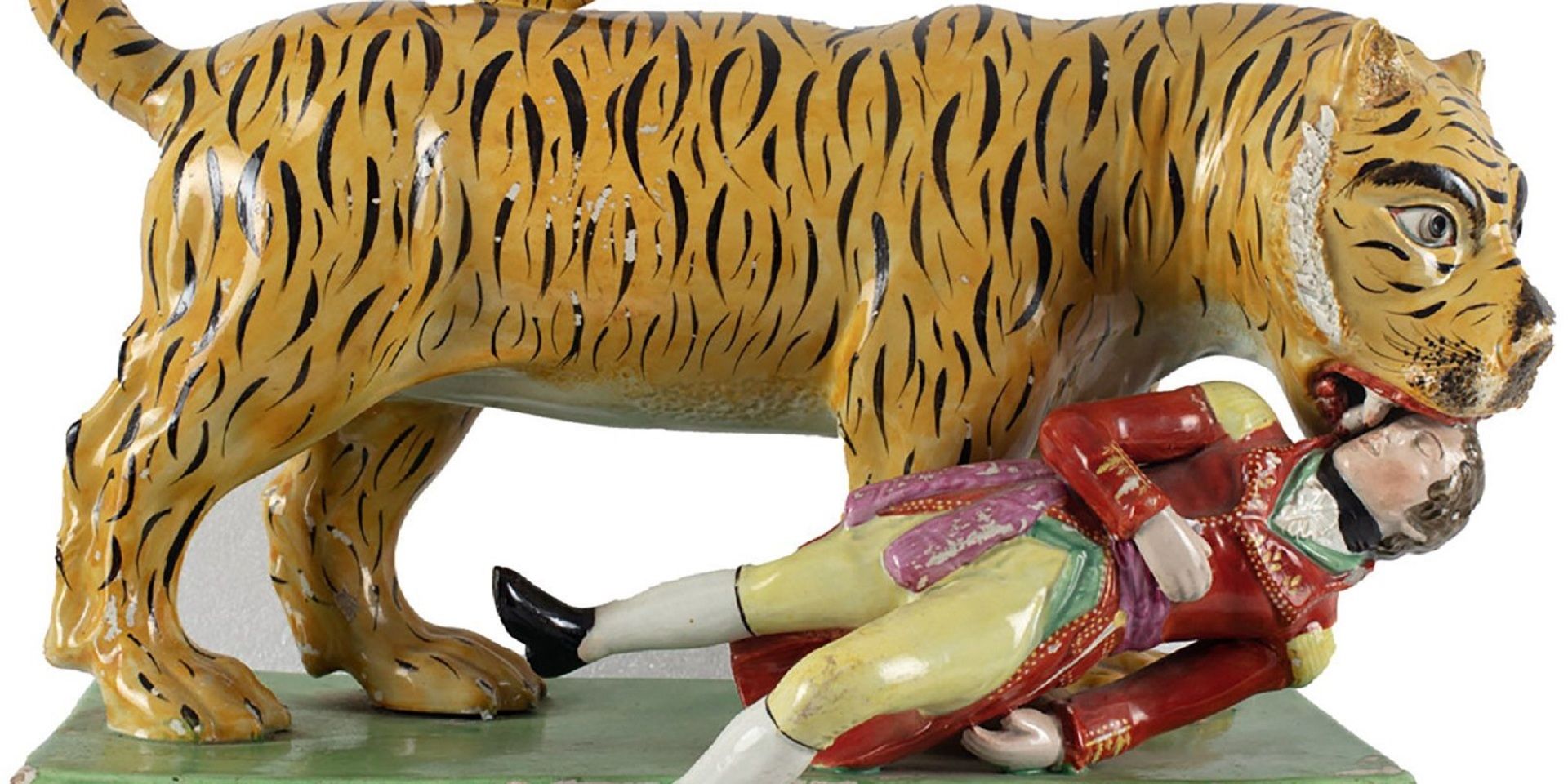

Q. Like the Aror Bans Press, which you have discussed briefly in your book, do you know about other major printers or publishers who were displaced by partition? What were the infrastructural facilities available to them post-partition in India or Pakistan and how do you think partition impacted the wide network of publishers, printers and distributors across the subcontinent who frequently worked with each other?

Yousuf: The partition had a substantial impact on this wide network. It's an area that has received little attention and research. I've come across some information on the subject and have written about it, but there's a notable gap in understanding what happened to these publishers when they crossed borders. Surprisingly, even in Pakistan, where I've consulted with art historians, there's a dearth of knowledge about the fate of these publishers and their activities post-partition.

Take the Taj Press in Lahore, for instance; they were known for producing posters featuring Mecca and Medina. Interestingly, some of these posters have been found in India as well, and I have a couple of them in my personal collection. In attempting to trace the current status of Taj Press, I did some online research and learned that they have diversified into other areas. The challenge lies in tracking the trajectory of such businesses because, often, the original individuals engaged in the trade may not have continued it post-migration. It's common for their children or other family members to take over, especially given the initial devastation of the businesses after partition. Starting afresh and rebuilding the enterprise was a strenuous process for most, and only a few publishers managed to persevere through these challenges.

|

Unidentified artist, Gandhi poster, c. 1960, Offset print and serigraph on paper, 72.9 x 48.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

We may also consider the Jantri, or astrological almanacs, produced by Hindu publishers in Urdu in cities like Lahore. When these publishers migrated to India, particularly Delhi, they continued producing the Jantri. In their publications, they often mention their familial connection to Sialkot or Lahore, emphasizing their ancestral involvement in this field. The rationale behind this continuity was the recognition of a market demand. Upon arriving in India, Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan discovered a familiar market. To cater to these communities who primarily spoke Urdu, the publishers continued creating literature, images, calendars, and similar materials. On the other hand, there were cases like the Aror Bans Press, which also previously made Jantri works, but upon arriving in Delhi shifted their focus to the Mayapuri magazine and adopted Hindi in Devanagari script. This strategic shift reflected an adaptation to the linguistic preferences of the audience in India.

Likewise, when individuals from Delhi migrated to Lahore in Pakistan, they continued producing similar publications in Urdu, catering to the linguistic needs of their community. This continuity in language and content was crucial for maintaining readership among the migrating population. More research needs to be done in this field, certainly. Even in Pakistan there's a notable absence of preserved memories and materials related to this aspect. While some books may be found in libraries, establishing connections between publishers and tracking their transitions remains a challenging task.

Despite the partition in 1947, there was significant ongoing exchange between the two countries, marked by correspondence and the cross-border circulation of magazines. This reciprocal engagement persisted until 1965. However, with the outbreak of the war (between India and Pakistan) in 1965, this exchange came to an abrupt halt, putting an end to the ongoing connections and interactions between the publishing communities on both sides.

Sobha Singh, When the Goal was in Sight, 1945, Offset print on paper, 33.0 x 47.5 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. Where did you find major collections or holdings of popular art in India and Pakistan? Are they usually found in institutional/ public archives or personal ones? And can you tell us something about your Tasveer Ghar archive?

Yousuf: I have not found any of this material in any institutional archives; instead, they are primarily housed in personal ones. One example is the digitization project undertaken at Tasveer Ghar, where a substantial collection, including around 5000 images encompassing posters, calendars, and cinema-related items, was digitized. A significant portion of this collection comes from Priya Paul, who, in turn, acquires items from wholesale dealers, such as kabaadiwalas (junk dealers), with whom she has long-standing connections.

Having gone through her extensive collection, I felt like I was conducting an archaeological exploration of these images. The collection unveiled numerous artifacts dating back to pre-partition times. Beyond Tasveer Ghar, I looked at additional collections, including one belonging to the Pakistani art historian, Iftikhar Dadi, who is now based in the United States of America. I also benefited from the contributions of Jürgen Wasim Fremgen, a German scholar who spent time in Pakistan and amassed a collection of posters. Furthermore, during my visit in 2005, I personally collected a few posters as well; so yes, these works are mostly available in personal collections. Unfortunately, it seems that no institutional entity has undertaken the preservation of these valuable artifacts.

Hazrat Syed Lal Badshah Koh Murree, Rawalpindi, a poster of the emaciated sadhu-like saint at his shrine near the Murree hill station in northern Pakistan. Published in Lahore, Publisher and Artist unknown, c. 2000. From the collection of Yousuf Saeed at Tasveer Ghar.

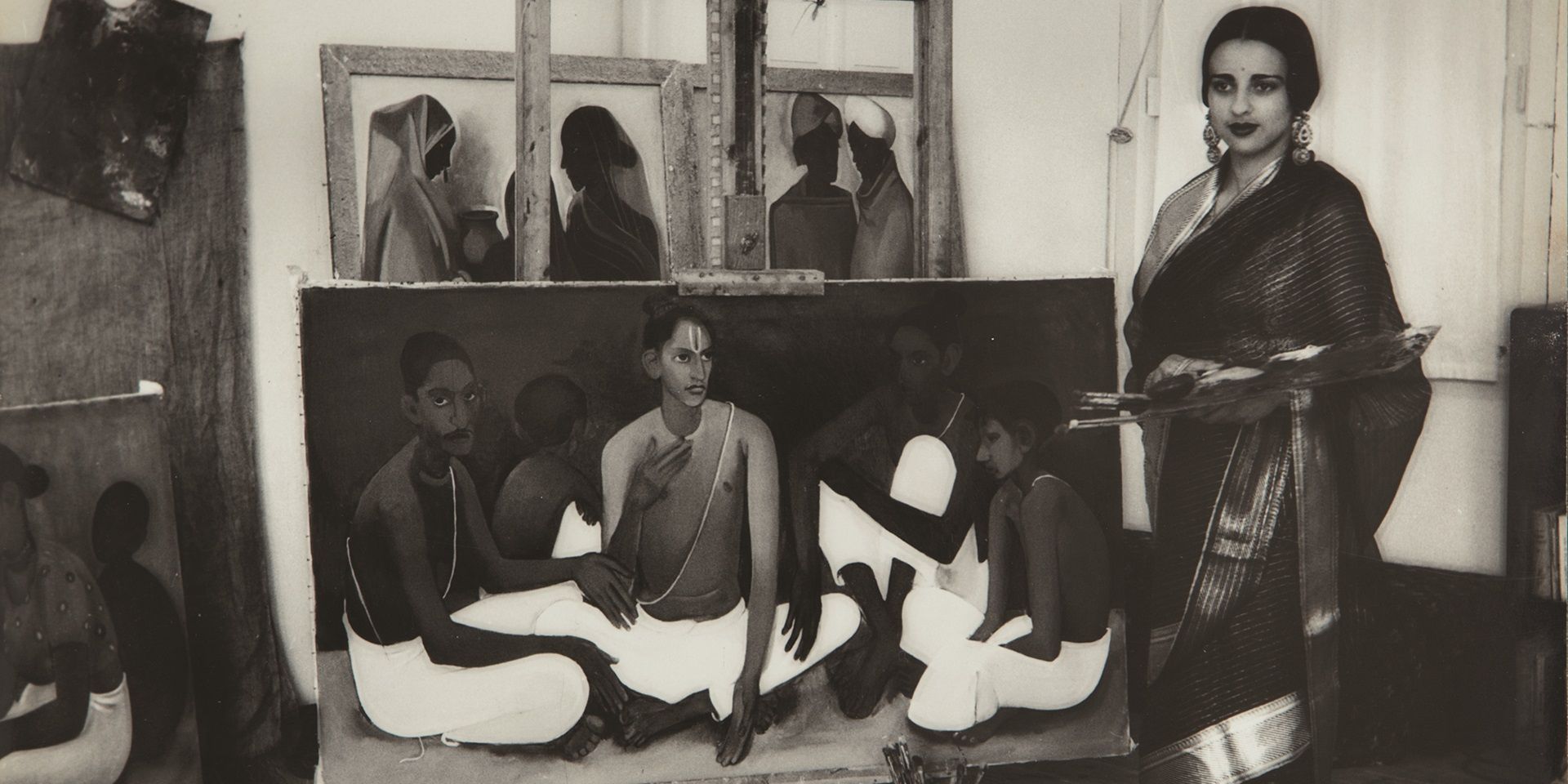

Tasveer Ghar was initiated in 2006 through the collaborative efforts of three partners – myself based in Delhi, Sumathi Ramaswamy in the U. S. A., and Christiane Brosius in Germany at Heidelberg University. We came together during a conference in Heidelberg, where researchers and art historians, including Patricia Oberoi, Jyotindra Jain, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta, among others, were in attendance. Recognizing the need for a digital space to document and archive popular art, we conceptualized Tasveer Ghar during these discussions. We established the website with support from various American universities, particularly those associated with Sumathi, and Heidelberg University.

Tasveer Ghar operates solely in the online realm, as maintaining a physical space for the vast collection of artifacts isn't feasible. While I personally possess a small collection of posters, our primary focus is on digital preservation. In 2008, we had the opportunity to digitize Priya Paul's collection, which was subsequently hosted on a server at Heidelberg University. To encourage scholarly engagement, we invited academics to put together visual essays based on her collection. The resulting essays, covering diverse themes, were compiled into a book, and the entire collection is accessible online.

Moreover, Tasveer Ghar has supported young scholars by providing fellowships on various topics, including gender, women's empowerment, religious syncretism, masculinity, and religious popular visual culture. Over time, we have amassed a substantial body of work, comprising essays and images available on the website. While not extensive, the collection serves as a valuable resource for scholars and enthusiasts interested in exploring the world of popular art.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025