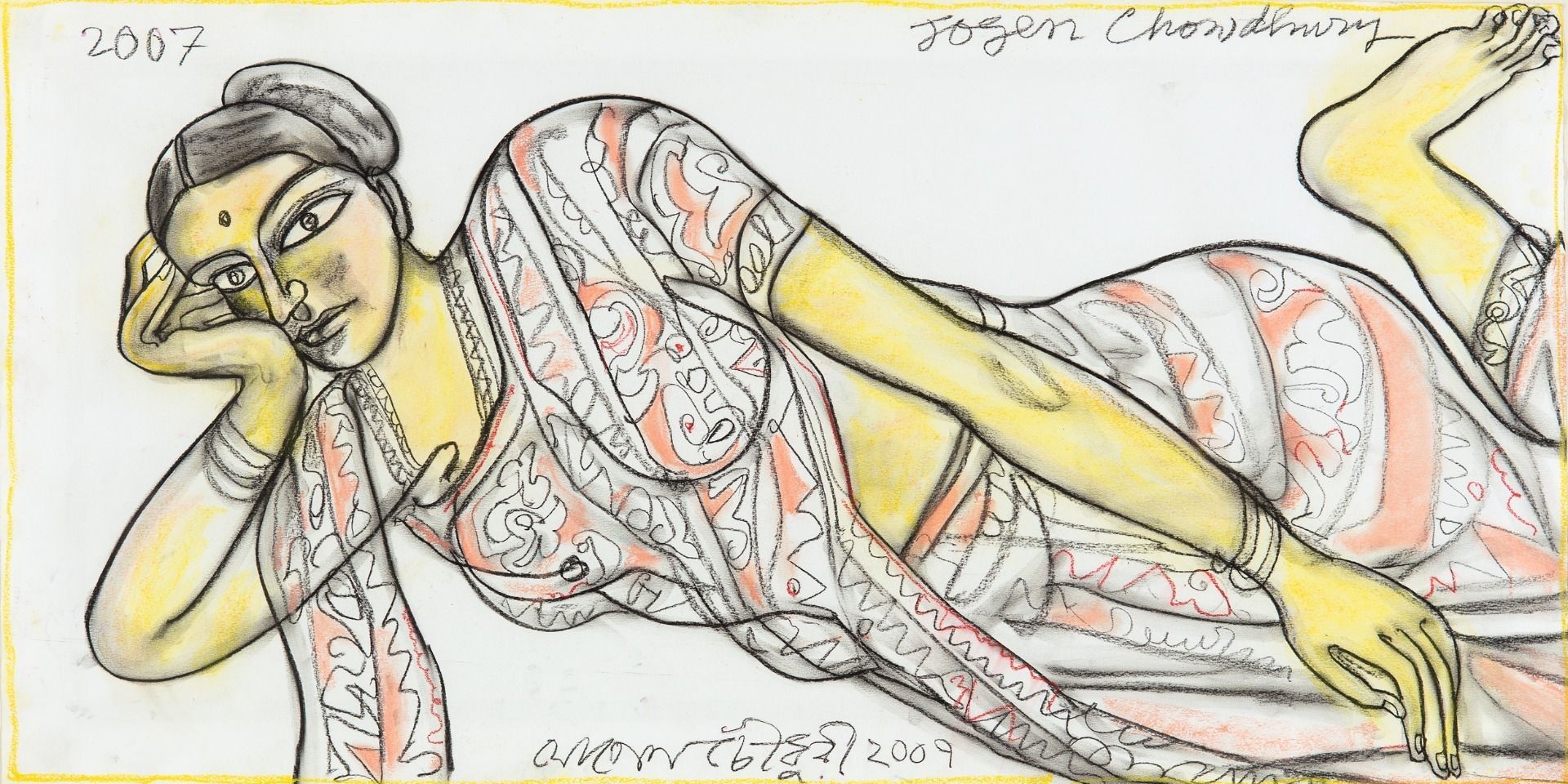

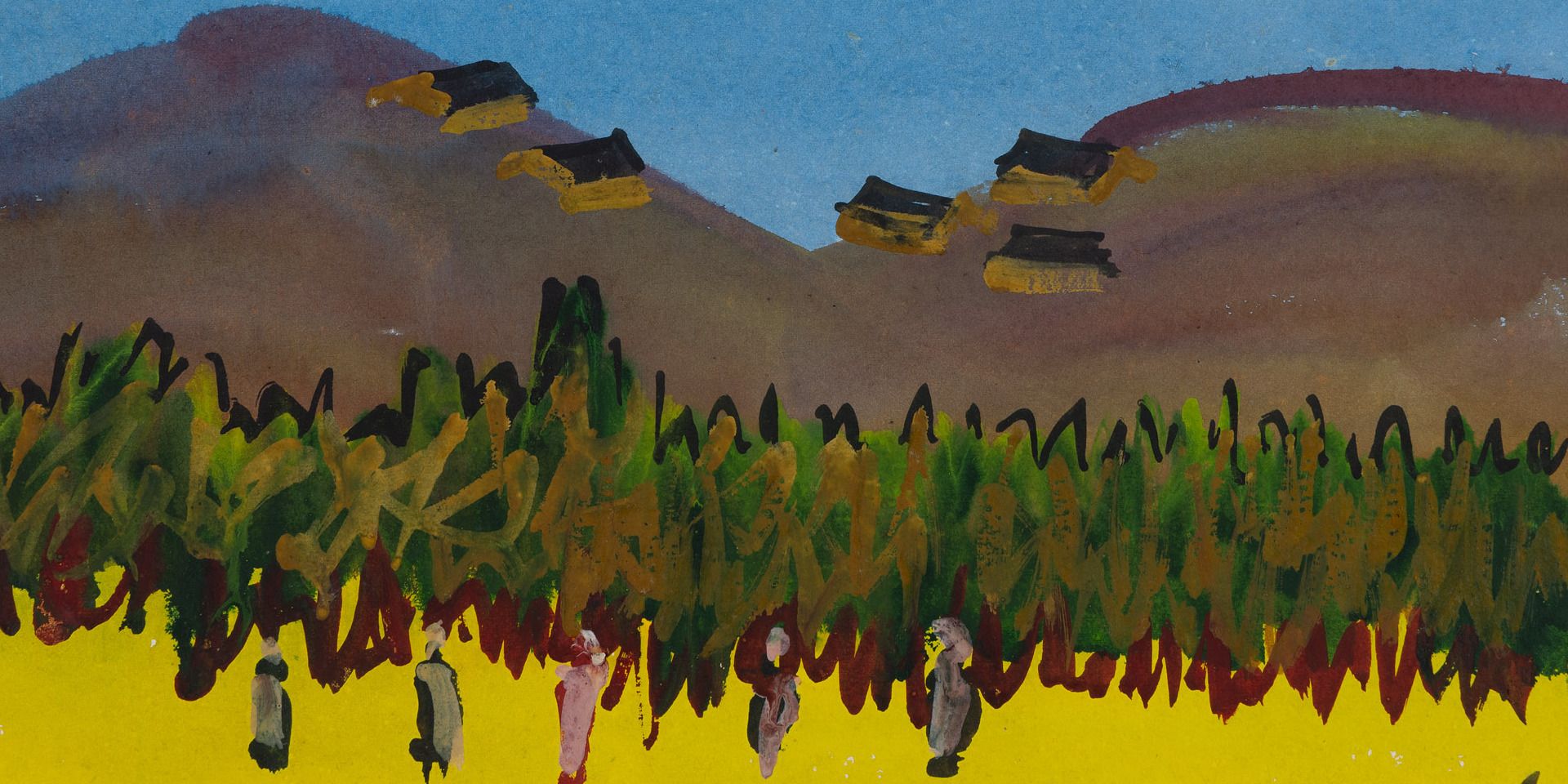

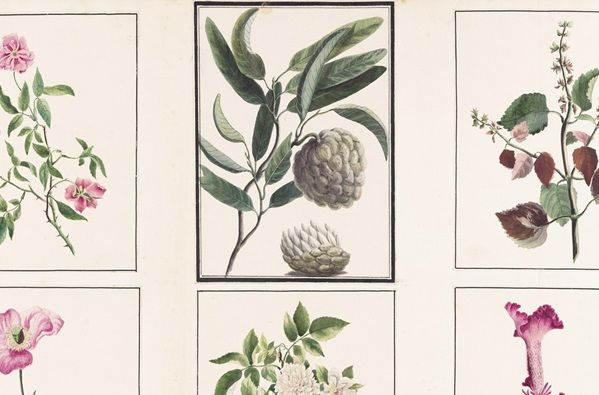

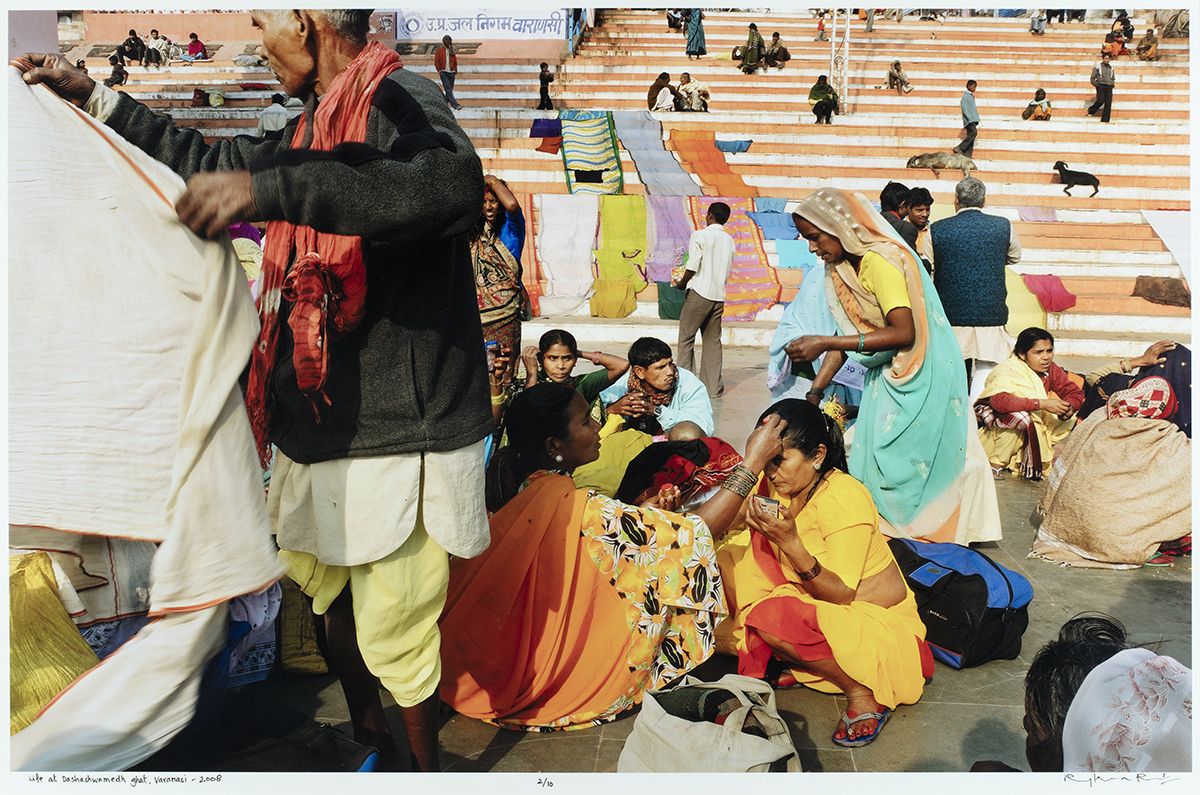

Modern Art in Mumbai: Jerry Pinto looks back

Modern Art in Mumbai: Jerry Pinto looks back

Modern Art in Mumbai: Jerry Pinto looks back

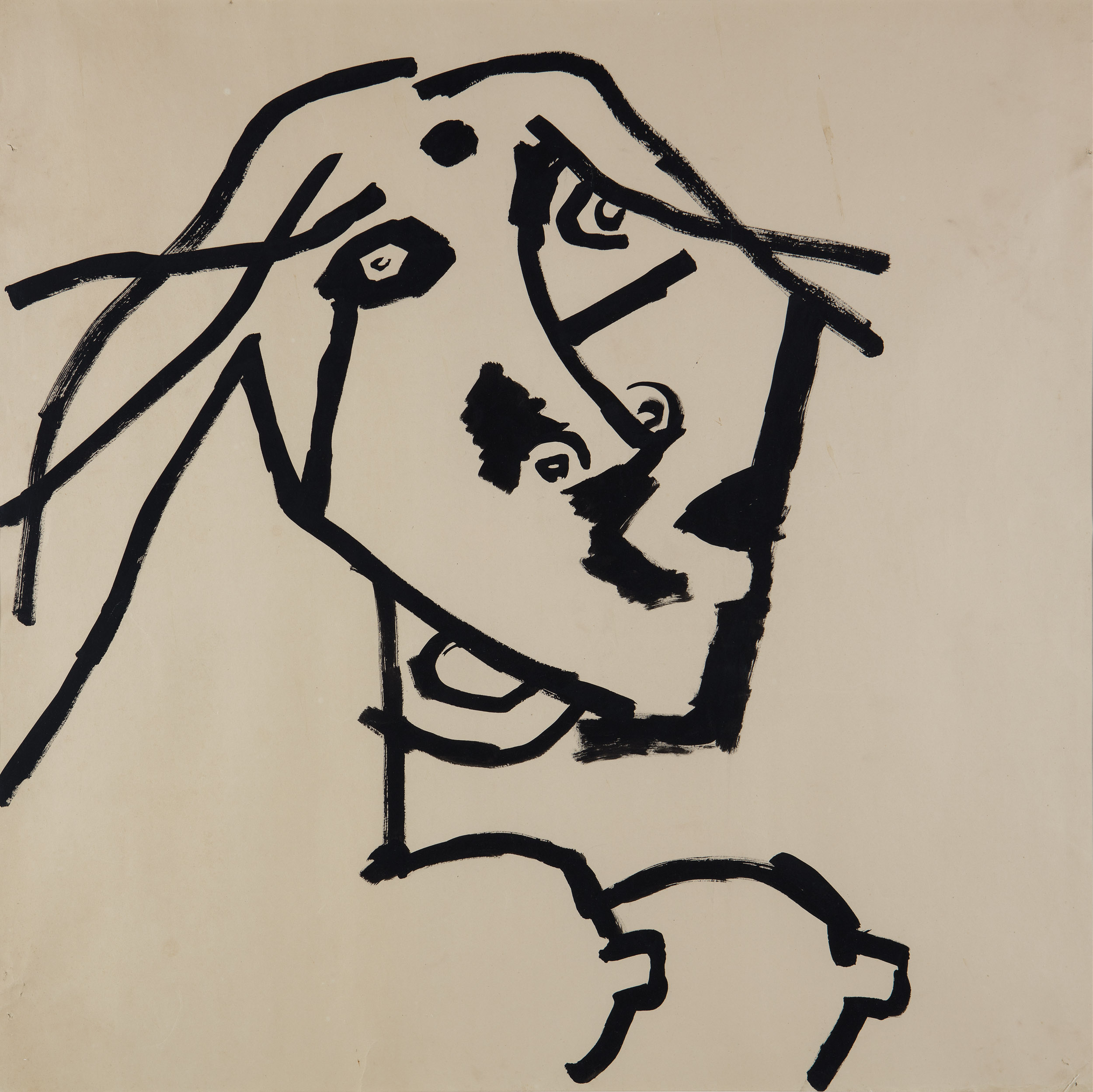

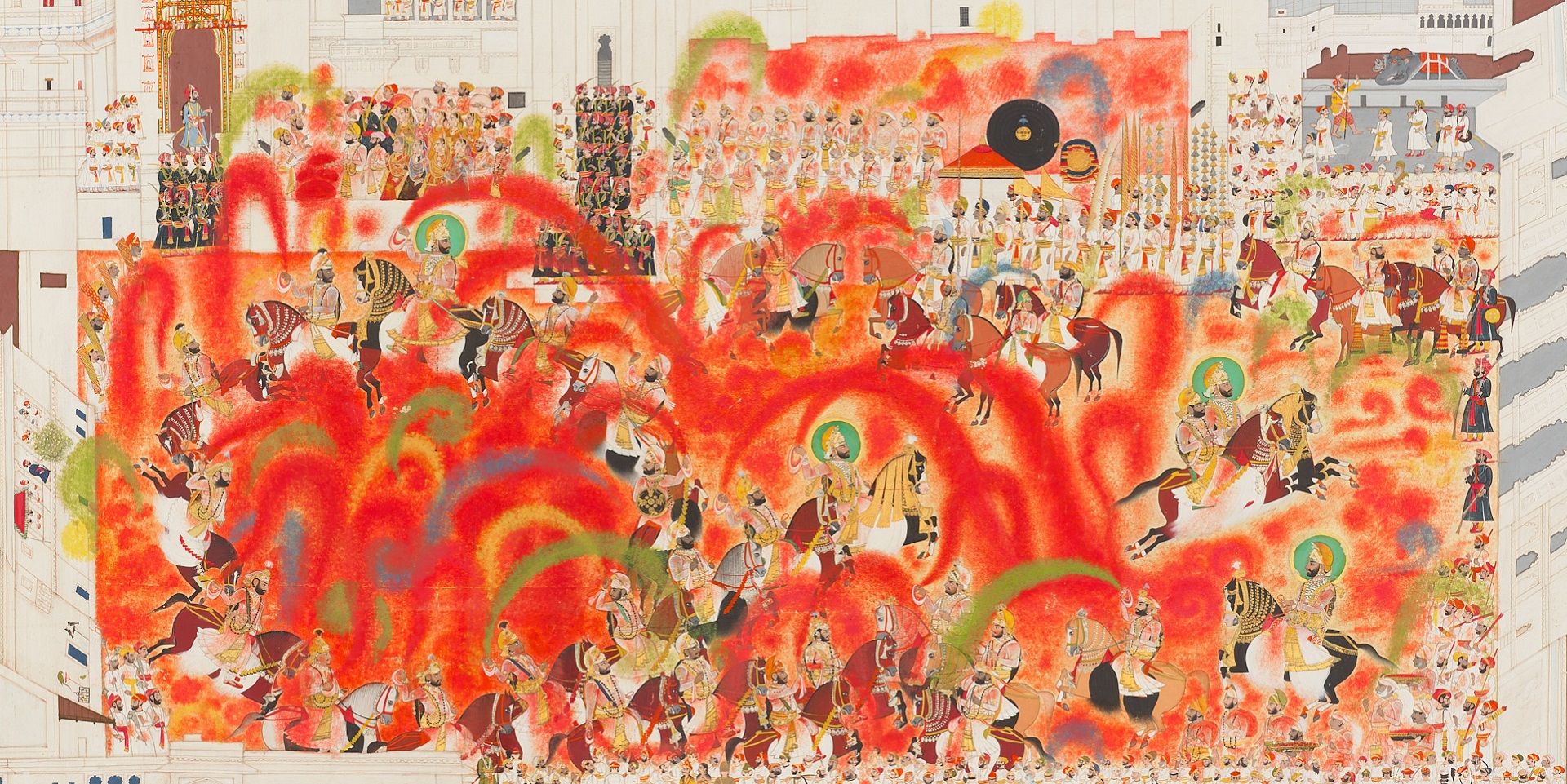

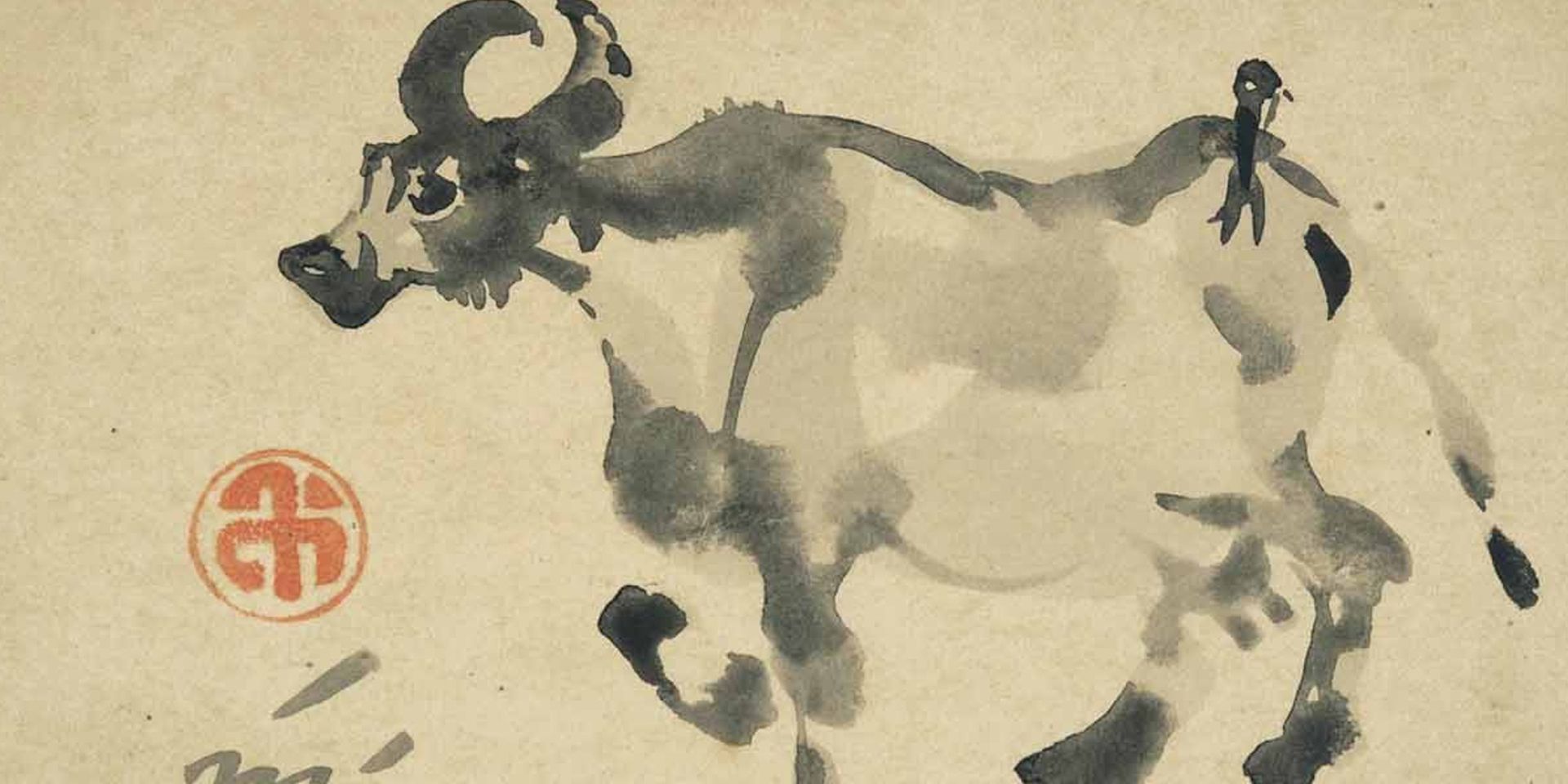

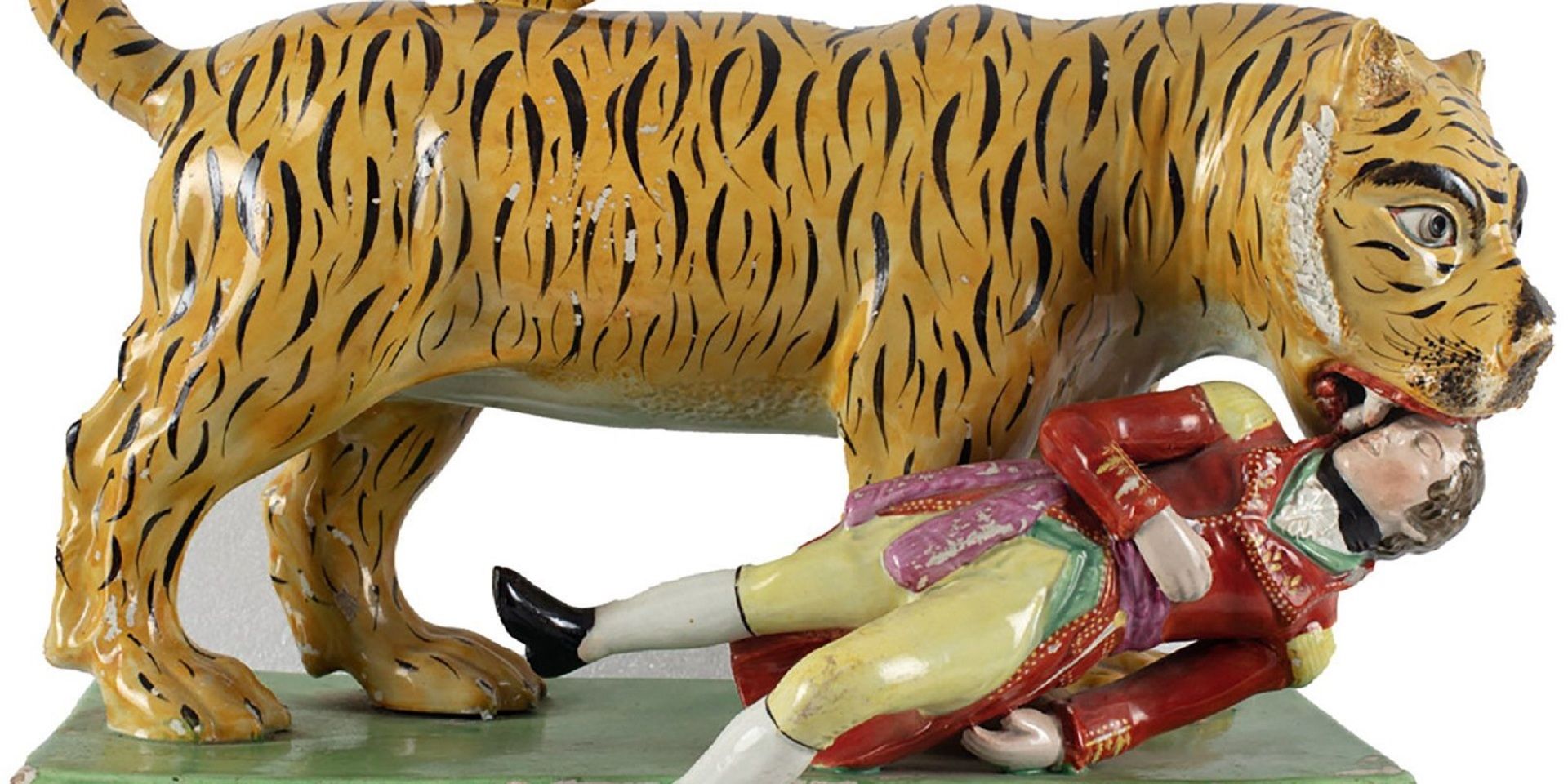

Mohan Samant, Untitled (detail), c. 1952, 18.0 x 23.7 in. / 45.7 x 60.2 cm., Acrylic, gouache and marker on cardboard. Collection: DAG. Samant was a member of the famous Progressive Artists Group of Mumbai, and later, the Bombay Group.

Award-winning poet, journalist and novelist Jerry Pinto has spent his career chronicling the cultural lives of the city he belongs to—Mumbai. From biographies of screen legends like Helen, to literary anthologies on Mumbai city, his work opens doorways towards popular as well as neglected areas of the city’s history, whether in cinema, the arts or literature.

When it comes to literary translations, Pinto’s works have brought popular Marathi voices into the national mainstream, such as Daya Pawar or Baburao Bagul; and with his translation of the artist Prabhakar Barwe’s prose for The Blank Canvas, he also highlighted another neglected area in Indian English art writing: the extensive body of texts that exist in ‘vernaculars’ like Marathi or Hindi.

With his new book, Citizen Gallery, Pinto revisits the post-independent art milieu of Bombay (now Mumbai), when influential art movements like The Bombay Progressive Artists' Group were taking shape within the rubric of this global, cosmopolitan city. The Group was composed of artists from various backgrounds and included the likes of F. N. Souza, M. F. Husain, S. H. Raza, K. H. Ara, H. A. Gade, S. K. Bakre and later on, Ram Kumar and Tyeb Mehta, among others. Seen through the eyes of Gallery Chemould, which was run by the Gandhys of Bandra, a dense and off-kilter image of cultural efflorescence shines through the book. He spoke to the editors of the DAG Journal about the book:

Author Jerry Pinto. Image credit: Wikimedia commons

I wanted to start with your early art journalism/criticism years, when you say you covered art exhibitions and interviews with artists in a fairly regular format for newspapers. How did you prepare yourself to write popularly about art? Who were some of the art writers that inspired you when you set out or what were some of the noteworthy Indian books or publications that you felt equipped you beyond the easy accessibility to artists and curators that spaces like the Samovar café or the Jehangir Art Gallery afforded?

Jerry Pinto: Those were the days when there was space in the newspapers for the arts. Then the Times of India decided that the artists were doing well enough and the galleries doing well enough so they could pay for the space. This was an incredible decision, ugly, ill-considered and offensive in spirit and letter but completely in keeping with the spirit of the Times.

But even then I remember thinking that we needed to have a greater variety of registers in our art writing. There was the High Modern and there was the Low Illiterate. I thought we needed to have someone who could say something about art in the way that worked against the high waves of modernism and the fatuity of illiteracy.

I remember how Nissim Ezekiel told me of the time he was doing art criticism and his friend, Ebrahim Alkazi said he could not possibly talk about oil painting until he had seen the Old Masters. Nissim told him that he had no chance of ever doing that since he could not afford the fare to Europe. A little while later, Alkazi got into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London and he booked a ticket for himself and he booked a ticket for Nissim too. And off Nissim went and:

'Philosophy,

Poverty and Poetry, three

Companions shared my basement room.'

as he wrote in ‘Background, Casually’.

I saw my first Old Masters many years after I had started writing about painting. Perhaps I should have waited but I was also a free-lance journalist and the tribe did not turn down assignments.

So I read a lot of art criticism, buying random books from the street: Ortega-Gasset and Jean-Paul Sartre. I studied the glossy art books at Strand Book Stall on the mezzanine floor, longing to buy, unable to afford, the student dilemma: eat lunch or buy a book? I haunted the museums and went to every art gallery I could. I discovered gallery openings with cheese and cherry and pineapple on a straw. I talked to people. Baiju Parthan worked on the same floor as I did and I learned from him. Ranjit Hoskote was one floor down and I learned from him too. Many artists came to the Poetry Circle; Mehlli Gobhai was one of them; so was Gieve Patel. I had editors like Shanta Gokhale (at the Independent), Meenakshi Shedde (at the Metropolis on Saturday) and Sonal Patel (at Bombay Times) who trusted my eye and my words. I refined my seeing by seeing. I refined my writing by writing. I suppose there are other ways. This was mine.

There are no arts pages these days but then these days there’s the internet and I am sure young art critics are hanging out there, writing and learning, learning and writing. I wonder though whether the galleries are looking around there, scoping out the next new voices. Or is everyone still stuck with the names we have, the names we know?

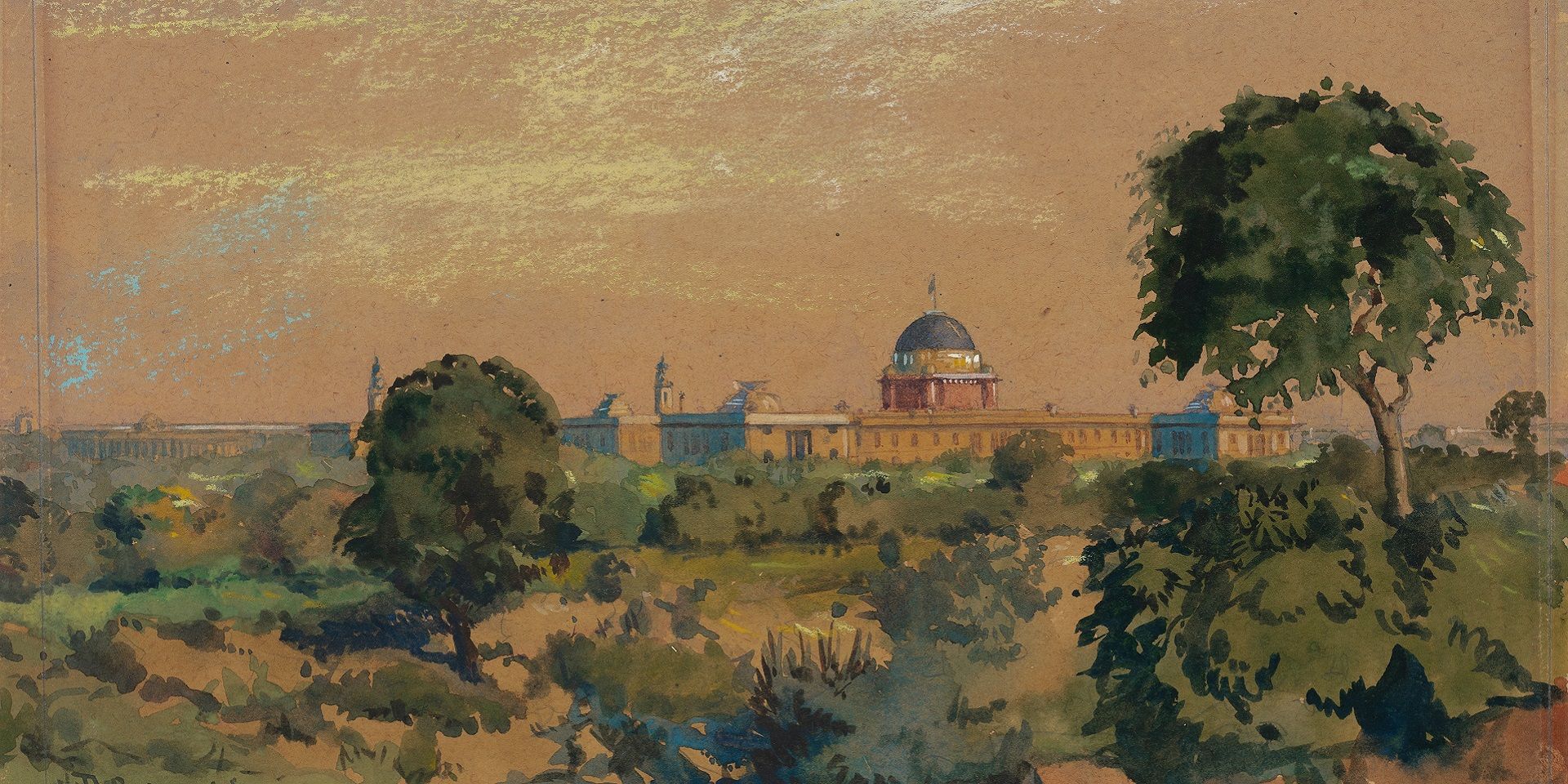

Prabhakar Barwe, Circular Oneness, 1994, 48.0 x 48.0 in. / 121.9 x 121.9 cm., Enamel on canvas. Collection: DAG

In Citizen Gallery, you quote Gallery Chemould’s Kekoo Gandhy as saying once (while in Switzerland) that he’s doing the 'government’s work—making Indian art known in the west'. But we also tend to hear about this period being a time of great state-aided cultural exchange programmes from which many artists benefitted with travel, foreign exhibitions and gaining western collectors that translated into universal popularity and value for their work. How does this relationship between state and artist evolve over time?

Jerry: India seems sometimes to be a black swan event.

India’s art scene as it exists today seems like a black cygnet event, spawned by some contradiction of the law of averages.

It is the terribilitas with which we are surrounded that makes us look back at the way things were and wonder that they could be that way. Or else a Muslim (Alkazi) paying for a Jew (Nissim) would not be a story worth telling again. So many of our stories rely on a beautiful past which actually only existed for a small educated elite who patted each other on the back for the diversity of their friend lists. That it was never broad-based has been proved in recent years.

So yes, we must celebrate the past and its magnificence but we must also be careful of the Scylla of Nostalgia and the Charybdis of Despair. Shilpa Gupta told me that hers was the first generation of artists that could live off their art. But of that inability came magic. Take the art teachers of the city of Bombay, Badri Narayan at Bombay International School, Lalitha Lajmi at Fort Convent, Piloo Pochkhanawalla at J. B. Petit School…

So if the State once funded the artist, that was the role of the State then.

After that we had the artists’ camps. A whole bunch of artist taken to Istanbul or to some sylvan retreat and hosted for a week or ten days or whatever period in return for a painting.

Today, they fund themselves. Good for them, I say.

As for the State working to help the cause of Indian art, that still isn’t happening unless you count the erection of enormous statues of political leaders and the erasure of our built-up history.

|

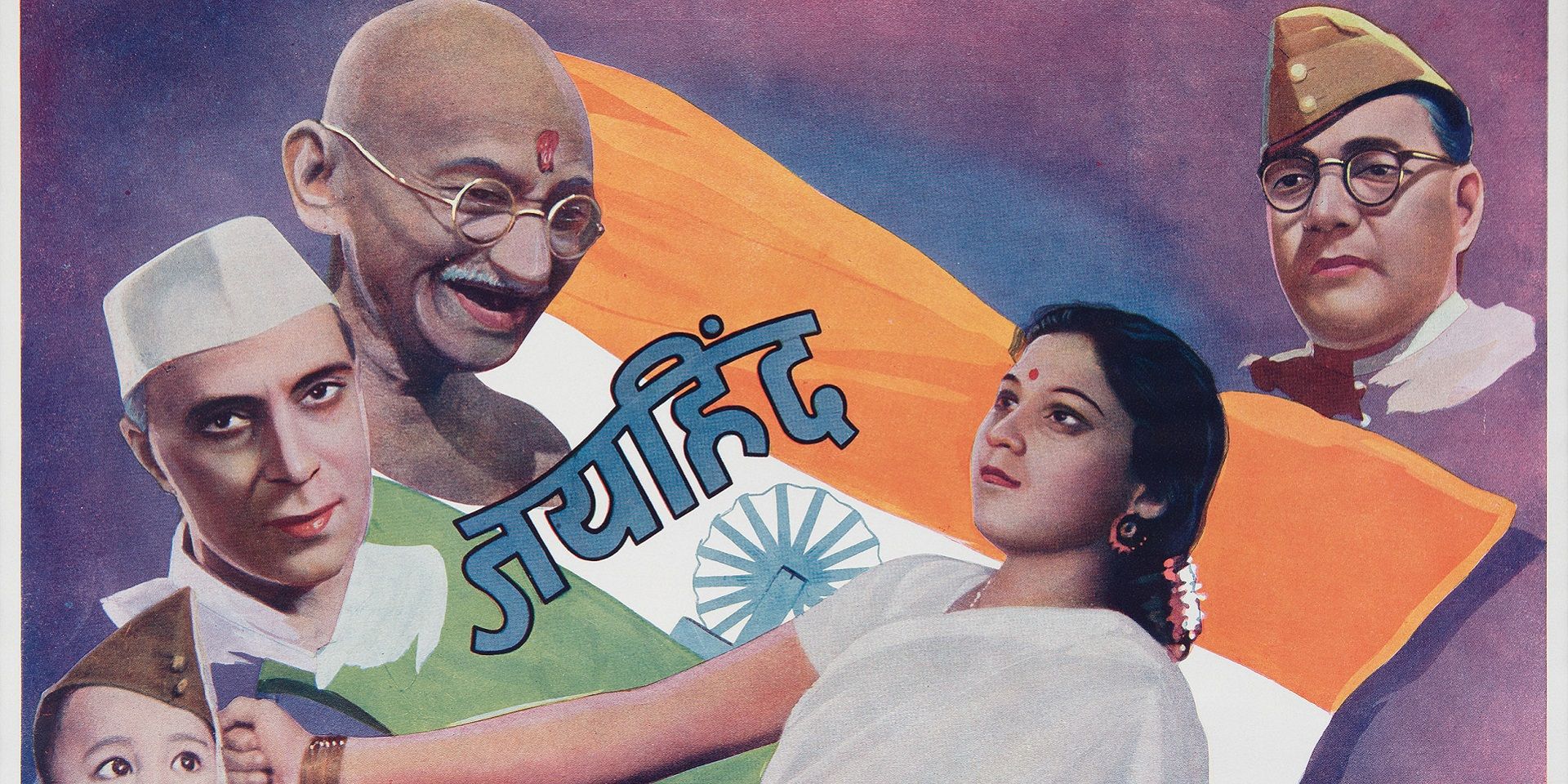

M. F. Husain, Untitled, 30.7 x 30.7 in. / 78.0 x 78.0 cm., Acrylic on paper. Collection: DAG. Husain was one of the earliest successful Progressives of Bombay, and his success was linked to the success of galleries like Chemould |

|

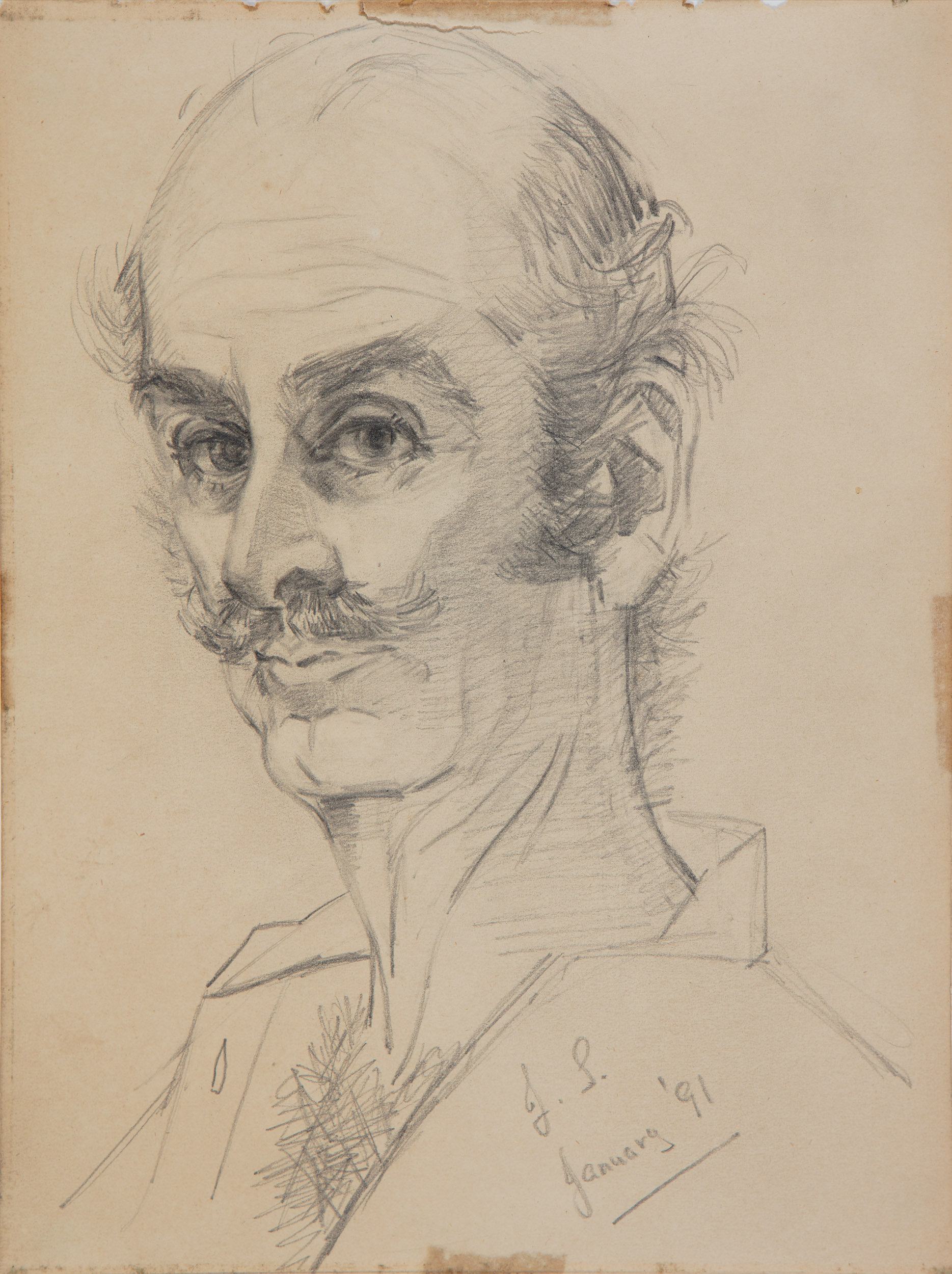

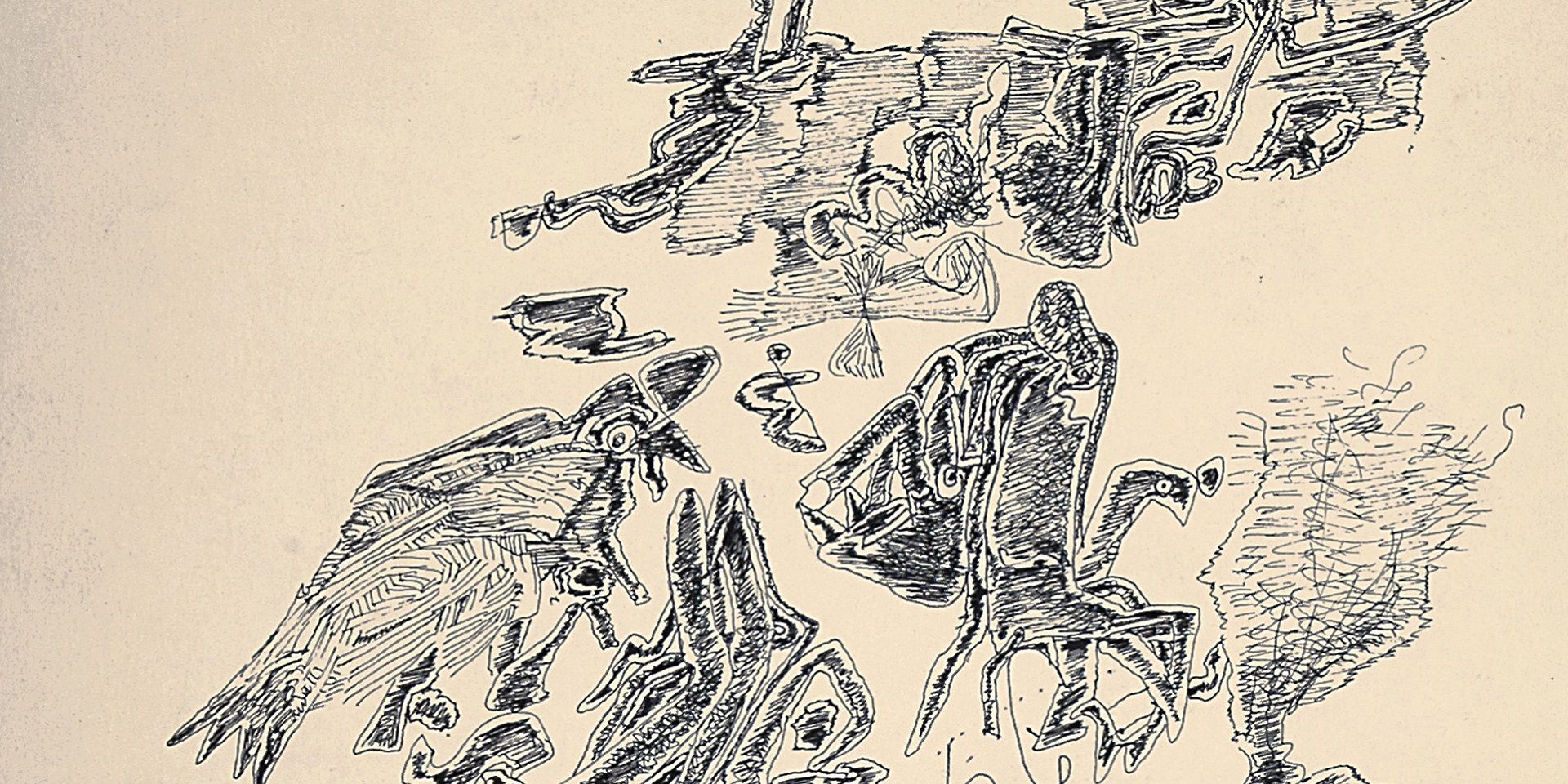

Jehangir Sabavala, Untitled, 1991, 9.2 x 7.0 in. / 23.4 x 17.8 cm., Graphite on newsprint paper. Collection: DAG. Belonging to a wealthy Parsi family (related to Sir Cowasji Jehangir, founder of the Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai), Sabavala was one of the most visible artists in the city’s post-independent art-scene. |

The book also goes into great detail about Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy’s personal lives, their family circumstances and the Parsi community at large. How do you think their culturally privileged but minoritarian presence in the Indian postcolonial landscape informs their choice of constructing their roster of artists, at a time when ‘curation’ was not a very popular approach to look at artists or artworks in relation with each other?

Jerry: You know, no gallery has a magic formula. You look at the names on the roster now and some of them coruscate and some absorb light. They have been forgotten and this does not mean they were bad artists but that they did not catch that tide in the affairs of men which taken at the flood leads on to fortune. Jehangir Sabavala would often tell me of how cabals of buyers fixed prices; perhaps these artists lacked cabals behind them?

So the Gandhys were the first movers and they had that advantage. They were the go-to guys in the gallery space. Their imprimatur counted, I suspect, for Kali Pundole as well, their chief competitor. They had, neither of them, any formal training in art appreciation or art criticism but who did? But eventually each of them became an archive on their own, they knew almost everything there was to know and they developed that strange quality called ‘the eye’. They knew it when they saw it. Their economic privilege made it possible for them to stabilize the lives of some of the artists they worked with. They could help them with stipends. Their minoritarian status would have meant that they could segue between Hindu, Muslim and Christian, for the Gandhys began their work in the art world when Partition’s wounds were still bleeding.

|

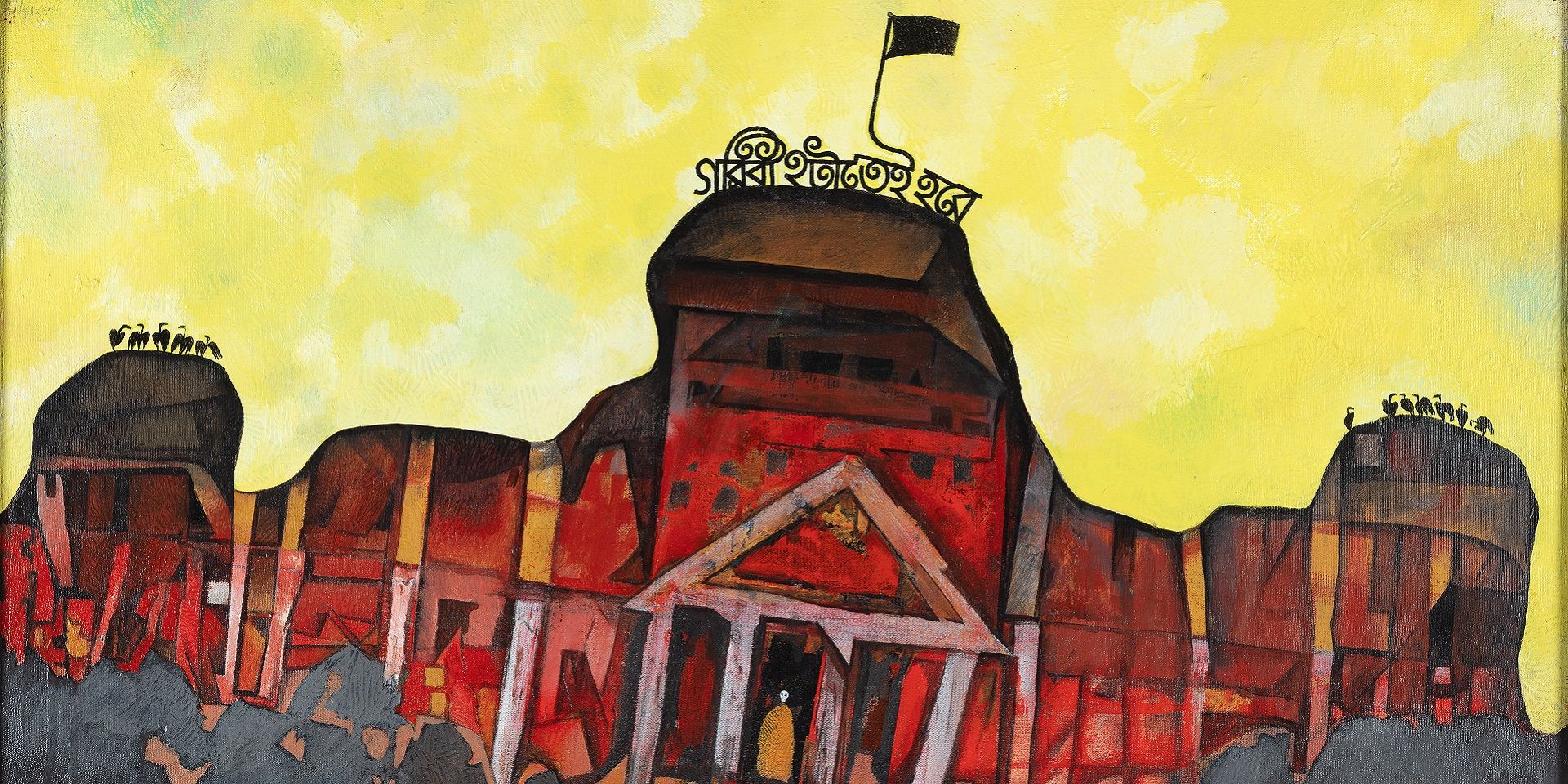

Paritosh Sen, Untitled (Portrait Cubist de Femme a la Cruche), 1952, 25.5 x 19.7 in. / 64.8 x 50.0 cm., Oil on canvas. Collection: DAG |

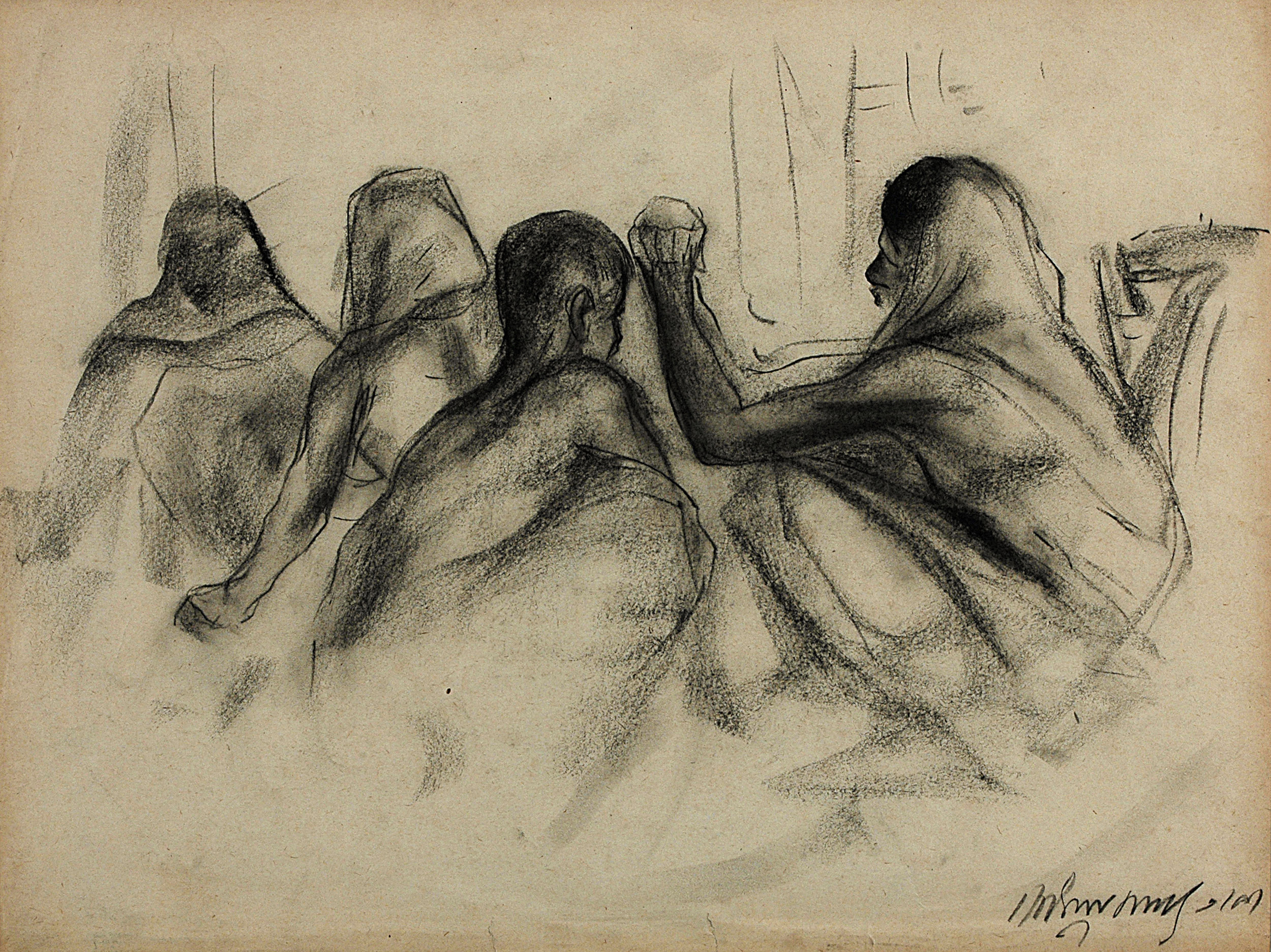

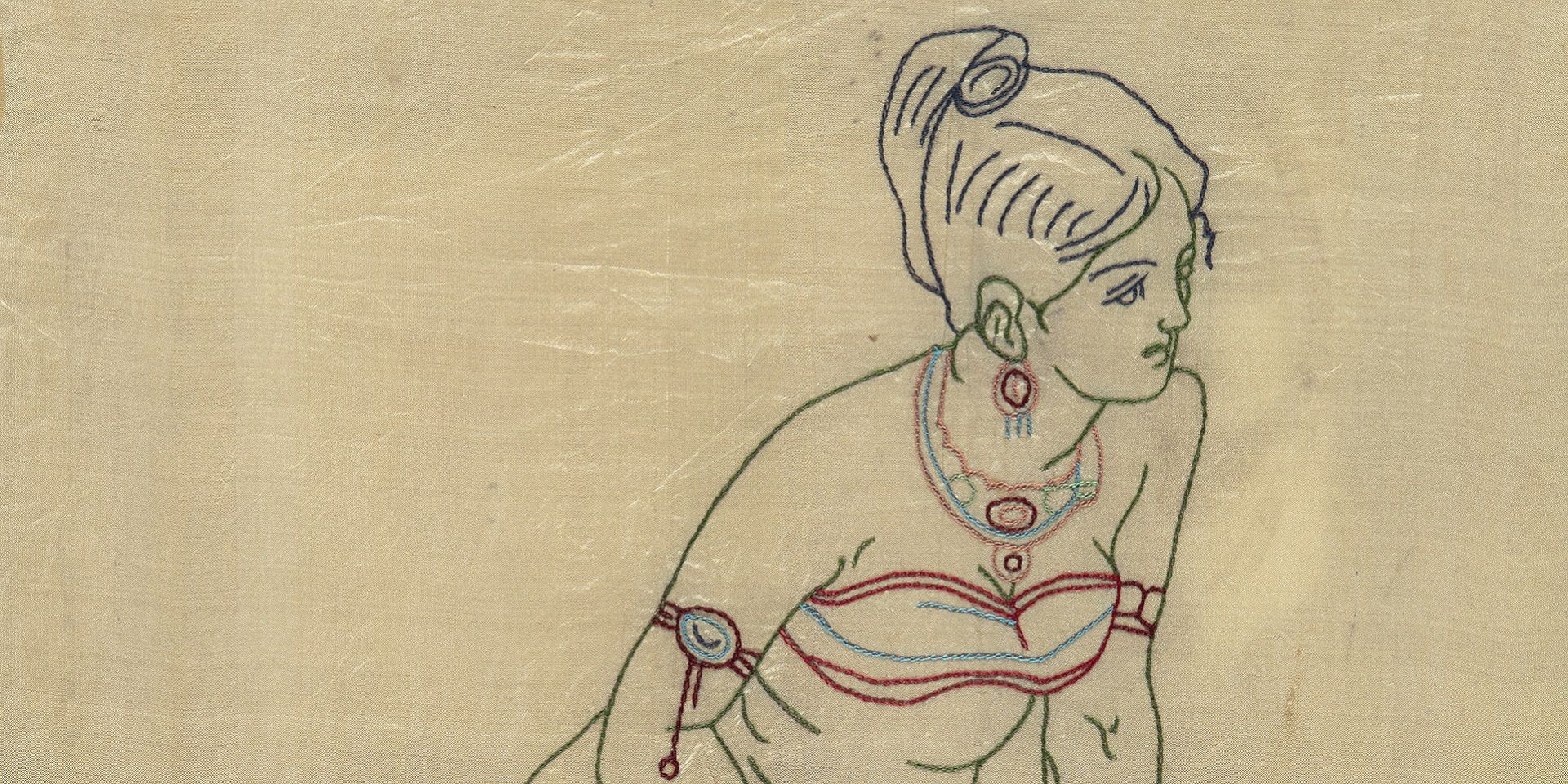

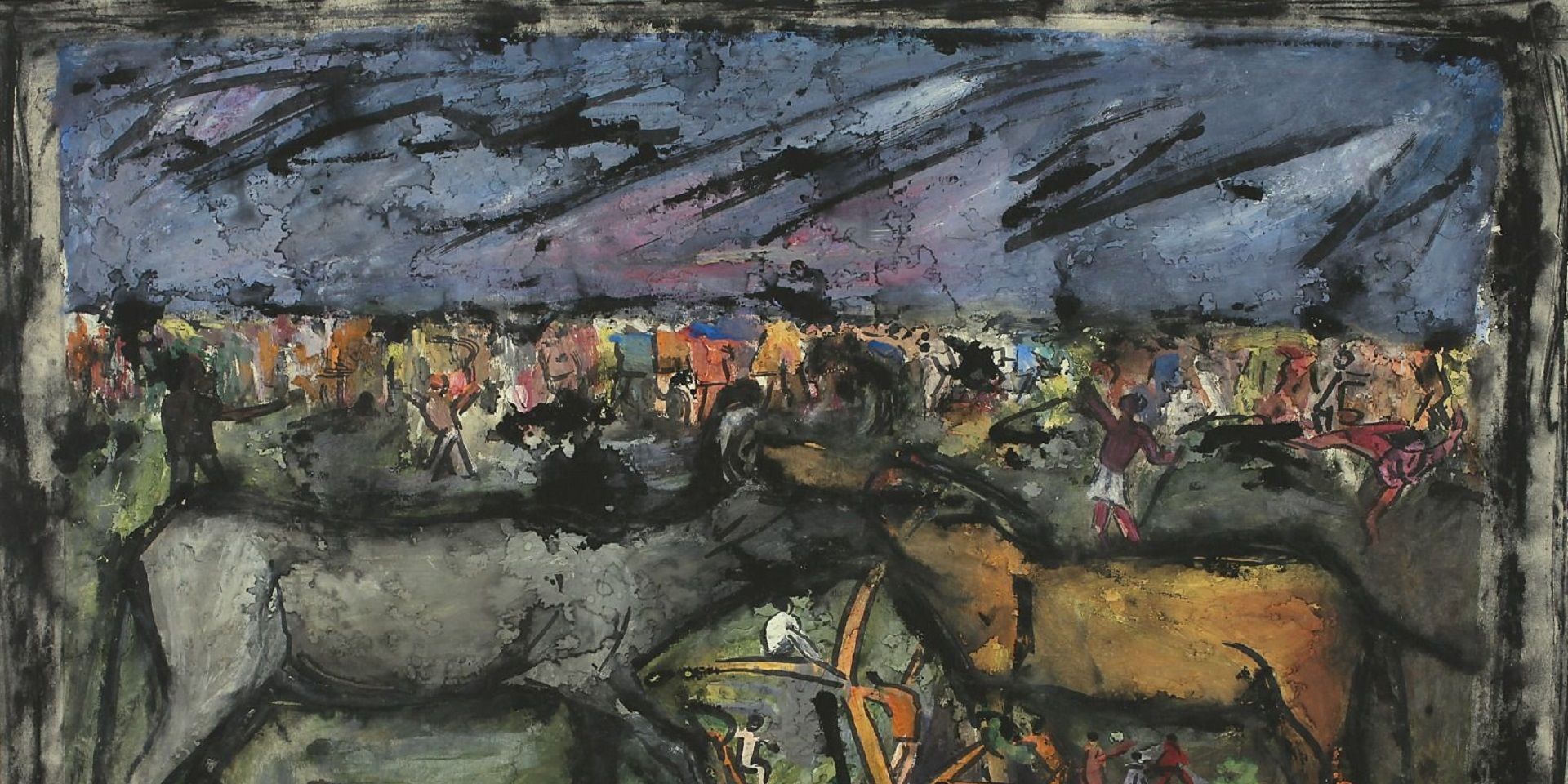

Sunil Das, Composition I, 1957, 14.5 x 19.2 in. / 36.8 x 48.8 cm., Charcoal on paper. Collection: DAG. Not just for Bombay artists, those from elsewhere like Paritosh Sen and Sunil Das found initial recognition through their exhibitions with Gallery Chemould's Calcutta (now Kolkata) chapter

Writing about the art spaces that preceded the appearance of galleries in Bombay (now Mumbai), you mention the J. J. School of Arts and the Bombay Art Society as the two major venues, both representing the rump of debates surrounding academic art until the middle of the last century. How do you see these cultural polemics playing out?

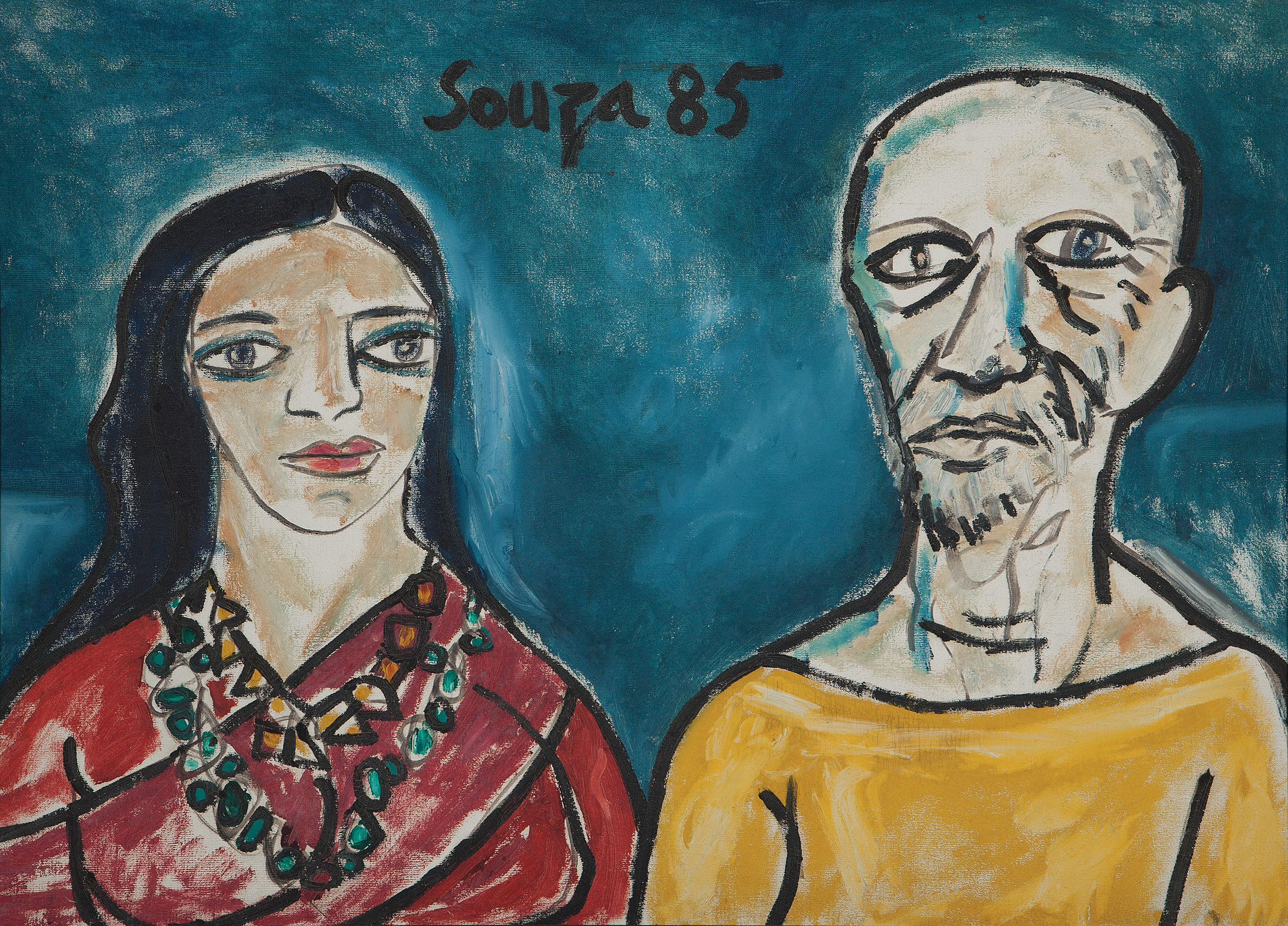

Jerry: I think the polemic is a work of anger and we must learn to respect the anger. I believe the manifesto is an act of rebellion and we must learn to respect the rebellion. Artists work with media other than words though a few were good with words—Souza was one, Ram Kumar comes to mind and Mehlli Gobhai—so their words often fail to sound the depths of their intentions. With Souza too, the problem has always been for me that he seems to be a bother. I can see why he speaks the way he does because he is tired of cant. I do not take his words any more seriously than his Redmonism but I am silenced, humbled by his work. There we must confront the power of his anger, his searing outrage, his vast abilities and his unquenched hungers. He was a mess, Souza, but his was a creative mess, the chaos and anarchy of the birth of a universe.

So our words, yours and mine, must fall short. We are turning them on that which would not be captured in language. Whatever we say will be stilted because it is an approximation of an approximation of an approximation. We’re wandering, you and I, wordpeople in a world not ours, and we must be humble or we might miss the point. I know I so often do.

F. N. Souza, Self Portrait with Young Woman, 1985, 29.0 x 40.0 in. / 73.7 x 101.6 cm., Oil on canvas. Collection: DAG

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025