Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

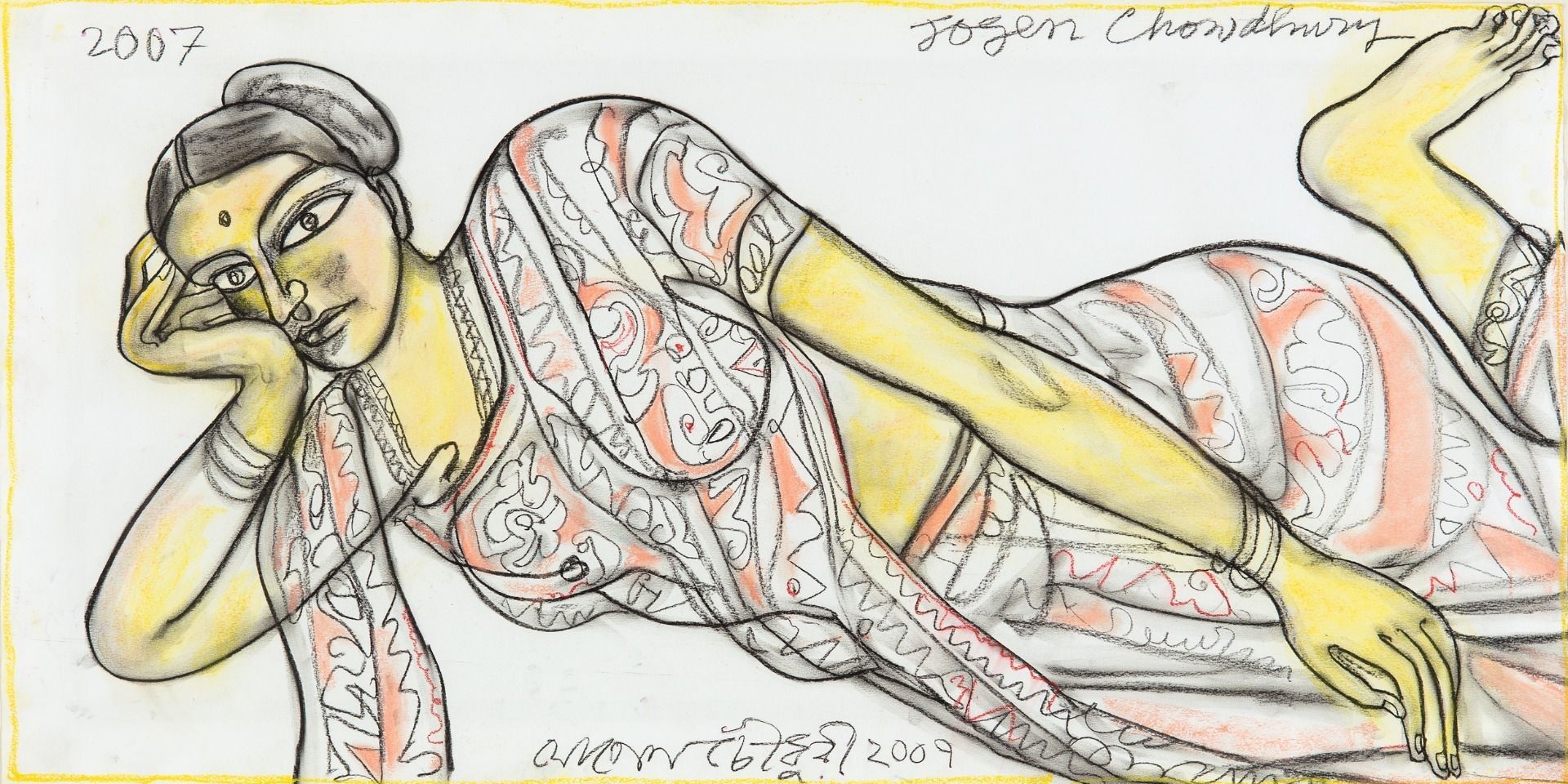

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

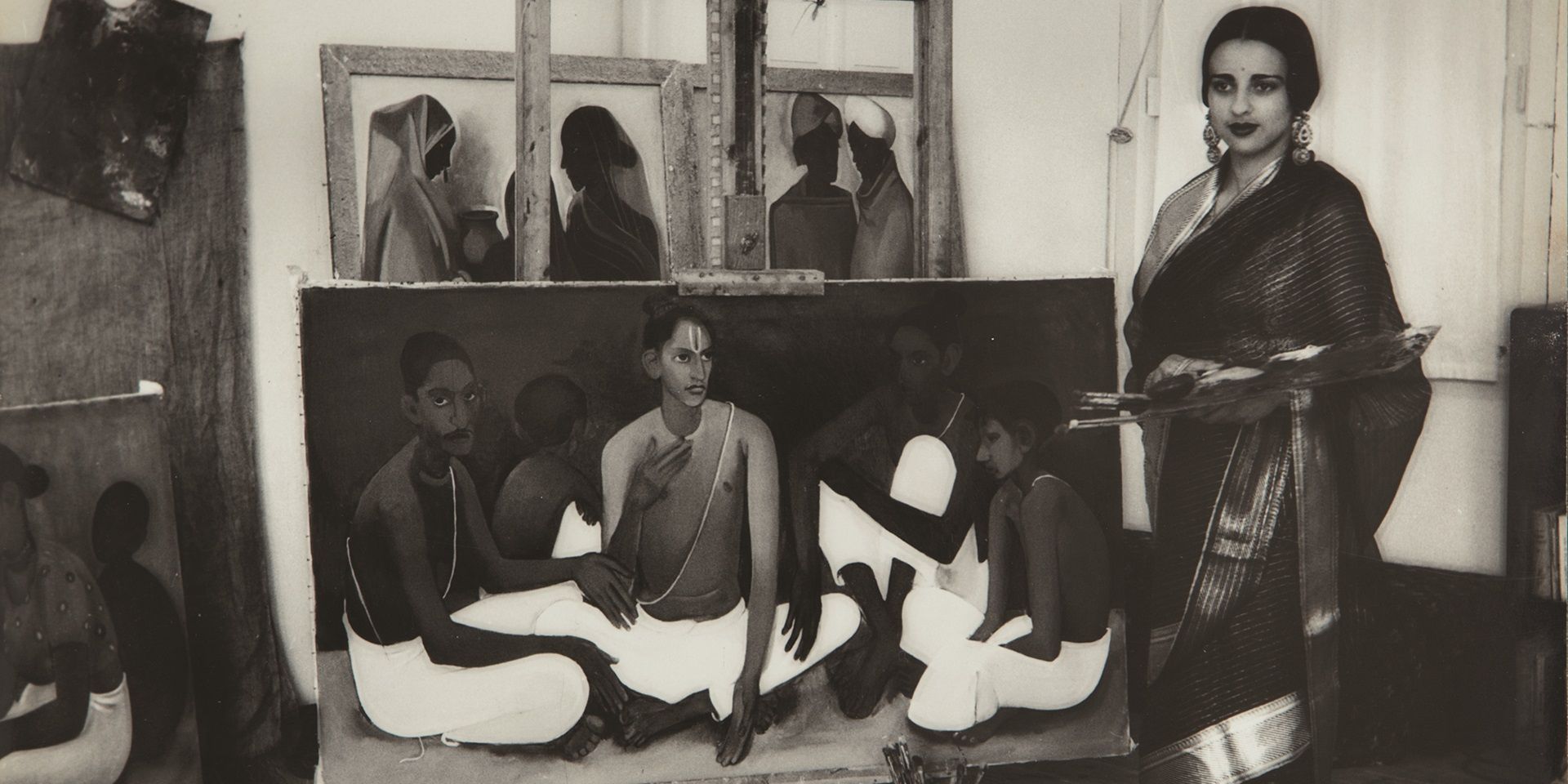

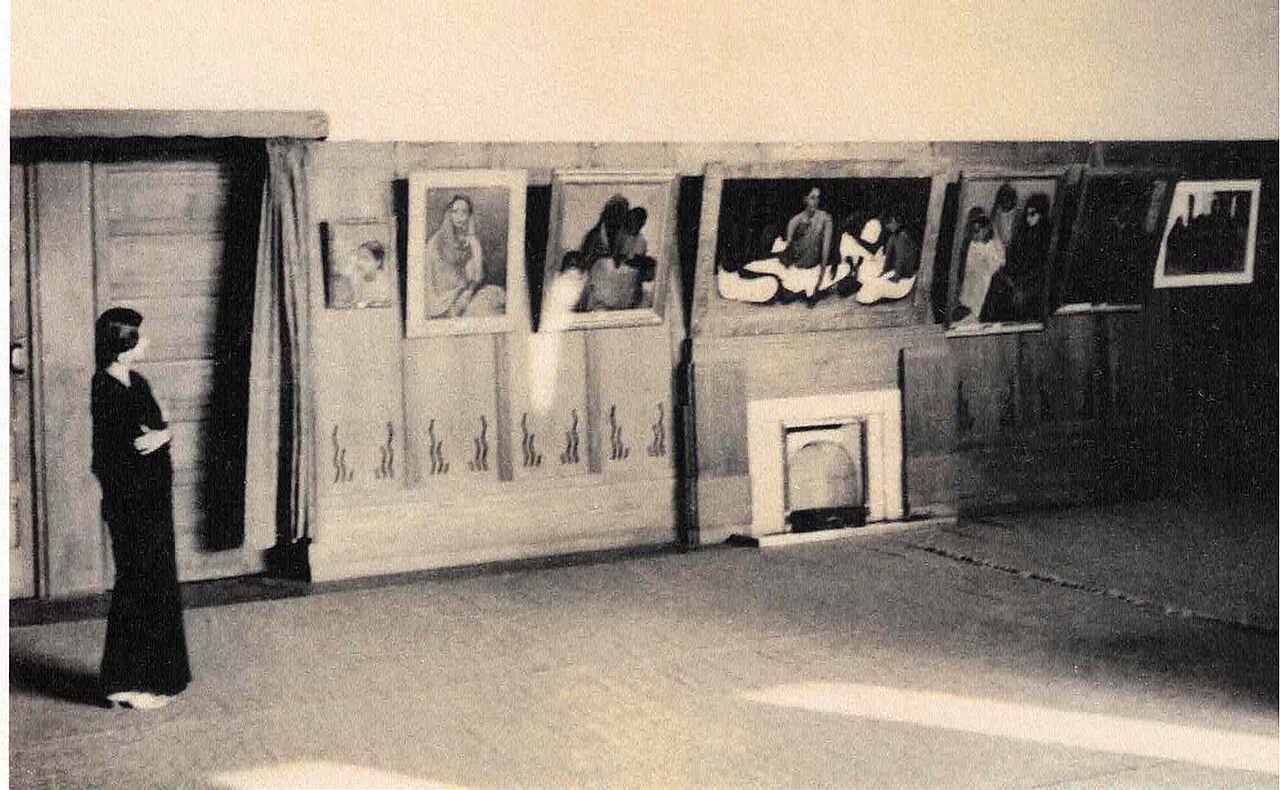

Amrita Sher-Gil with her painting Brahmacharis. Collection: DAG

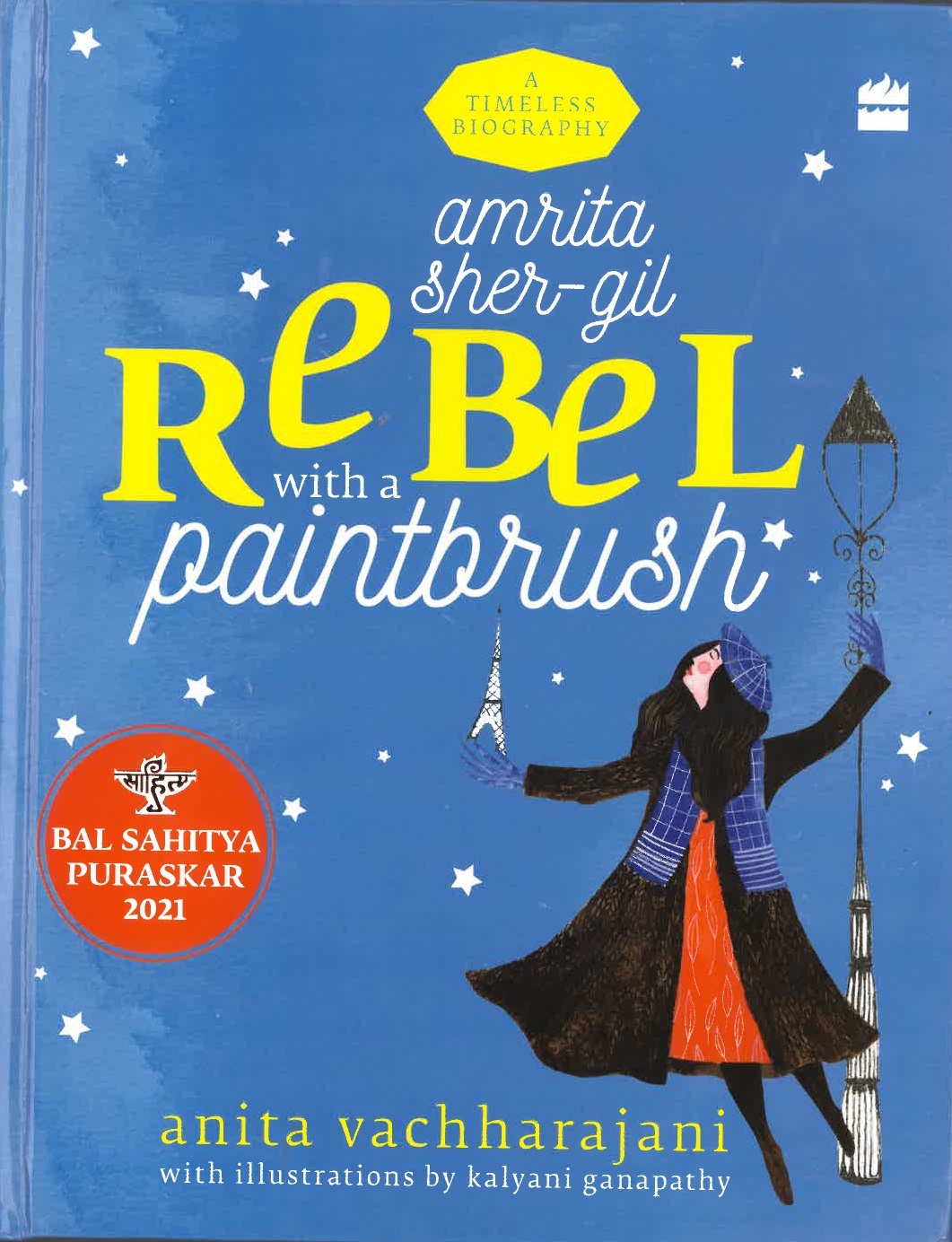

Anita Vachharajani is the author of Amrita Sher-Gil: Rebel with a Paintbrush, a biography of the seminal modernist painter from India and Hungary, aimed primarily towards a young readership.

It won the Sahitya Akademi’s Bal Sahitya Puraskar for English in 2021. Carrying illustrations by Kalyani Ganapathy, and drawing on archival material from the artist’s childhood, the book attempts to provide a narrative of Sher-Gil’s life that focuses on her multiple sources and locations of inspiration, while challenging received ideas about what made her such a fascinating figure in early to mid-twentieth century modernism. Rejecting the often prurient gaze directed at her life and work, the biography breaks new ground in terms of presenting to a younger readership a complex artistic persona that was shaped by multiple historical trajectories precipitated by India’s colonial encounter and subsequent turn towards reclaiming a ‘nationalist’ art.

She spoke to the editors of the DAG Journal about the journey she undertook to write the book and the larger process of writing about art and artists for young readers.

|

Cover of Anita Vachharajani's Amrita Sher-Gil: Rebel with a Paintbrush. Courtesy: Anita Vachharajani, Kalyani Ganapathy and Harper Collins India |

Q. How does one tell stories of art – which can be told through its material processes as well as its ideas – to children? What kind of children’s stories or books inspired you to write this?

Anita Vachharajani: I believe that children are, by nature, endlessly curious. If you can start from a place of storytelling—just that basic human instinct of wanting to know what happened next—you’re already halfway there. That impulse is especially strong in children. They love to follow a thread, to discover, to be surprised. Of course, not every artist’s life is packed with cliff-hangers or pirate ships, but even within quieter or more complex narratives, we can preserve that storytelling energy. We can still say, ‘And do you know what happened next?’—and keep that sense of momentum alive.

Telling Amrita Sher-Gil’s story wasn’t easy, but I found that if we respect children’s intelligence, curiosity and openness, we can share complex lives in ways that are accessible. We can gently introduce history, process, and difficult themes without it becoming heavy or didactic. Competing with so many forms of media today, it’s crucial to educate while being engaging. This book became a journey in learning how to talk about hard things lightly. While working on it, I was raising my daughter—then around seven—and was deeply aware of how narrow the dominant models of ‘success’ or ‘importance’ were for children. So, I started wondering: how do I bring in someone like Amrita into that world? How do I integrate her story into the kinds of stories children are already used to hearing?

|

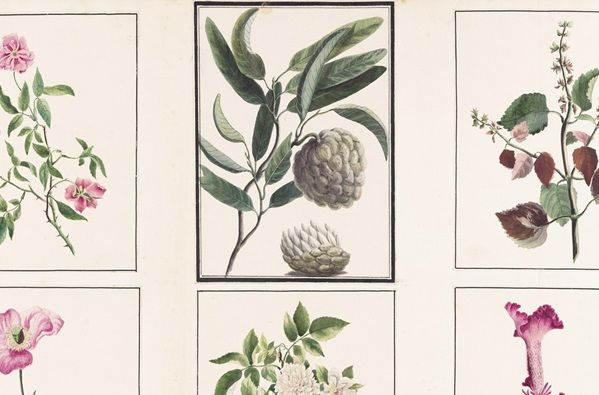

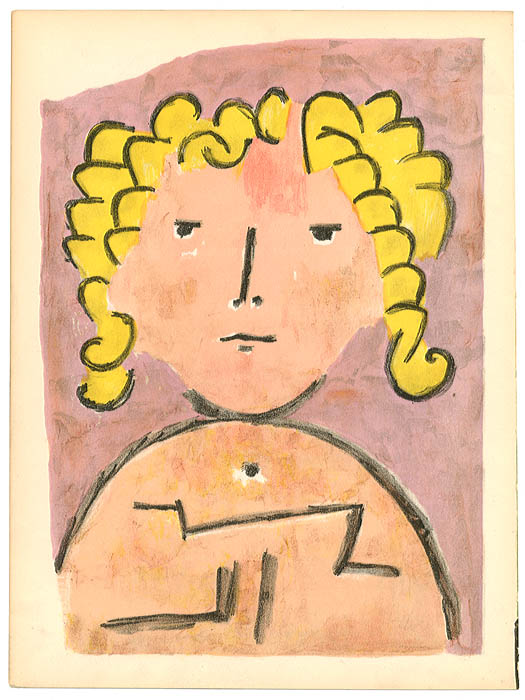

Paul Klee, Tête d'enfant (Head of a Child), 1939. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

I’m an absolute glutton for visuals in children’s books—especially when it comes to art. There is so much wonderful material out there about Western artists, made for Western children by Western writers—and our kids are consuming those books. But we have not been offering enough from our side. As a continuation of that existing pedagogy, why can’t we create equally rich material about our artists for our children and for children anywhere? I’ve always loved those large-format art books for kids. Growing up, my daughter had a wonderful series of picture books by the artist-writer James Mayhew introducing kids to different art movements. His books really inspired me to attempt something similar for Indian artists. Thankfully, now we’re seeing a lot more books like that being published—stories about Indian artists made for children everywhere. That is something to celebrate.

Q. How did the project materialise—especially the process of collaborating with your illustrator, Kalyani Ganpathy, whose work is featured across the book?

Anita: I have absolutely no hesitation in admitting that, for me, the first ‘text’ a child encounters in a book is the visual layer. The illustrations are their first text. Of course, we can write beautifully—lightly, playfully, even with a sense of adventure—but before anything else, the child is absorbing the visuals. That’s where they begin. So, I was very conscious of how important the visual narrative would be in this book.

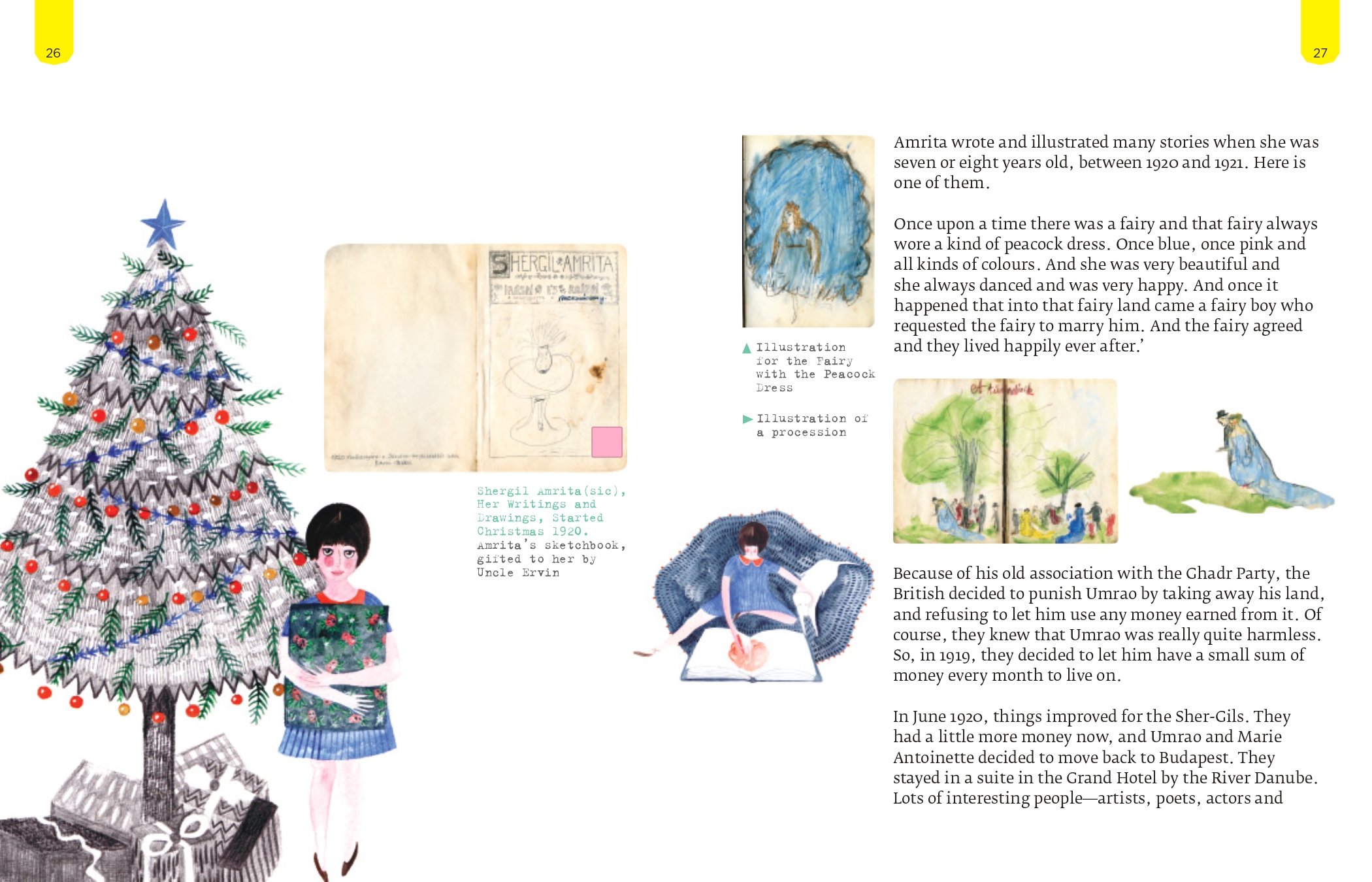

The book is made up of 'five distinct layers': the main narrative text, Amrita's own artworks going back to her childhood, boxed historical and contextual information, family photographs and the illustrator, Kalyani Ganpathy's art. Image courtesy: Anita Vachharajani, Kalyani Ganapathy and Harper Collins India

I gave myself the freedom to explore different artistic possibilities. I met with different artists, gave each of them a brief and a chapter, and waited to see what they would do with it. The responses ranged from stunning to indifferent. But even with the stunning submissions, there were complications. Some were beautifully done in a bold, graphic novel style—very intense, very accomplished—but I realised that their work risked overpowering Amrita’s story. And for a project like this, where we are introducing children to art history—not pirates or superheroes—you have to strike a very careful balance. The visuals need to invite children in, not dominate the space. Then I met Kalyani, who was probably the fifth artist I approached. She understood the brief intuitively and knew just how to support the story with her art—when to be bold and when to hold back. If you look at the book, you will notice this rhythm. In the first chapters, especially up to Amrita’s Paris years, Kalyani’s illustrations are present on every page. At that point, we are still telling Amrita’s story, still drawing readers in. But once Amrita begins to present her own art to the world, Kalyani subtly steps back. Her work becomes quieter—just spot illustrations here and there. That was not a direction from me—it was a decision she made on her own, organically. Yet her presence is felt throughout the book. She adds these clever little visual touches—something playful on each page—so it never feels dry or ‘educational’ in a heavy-handed way.

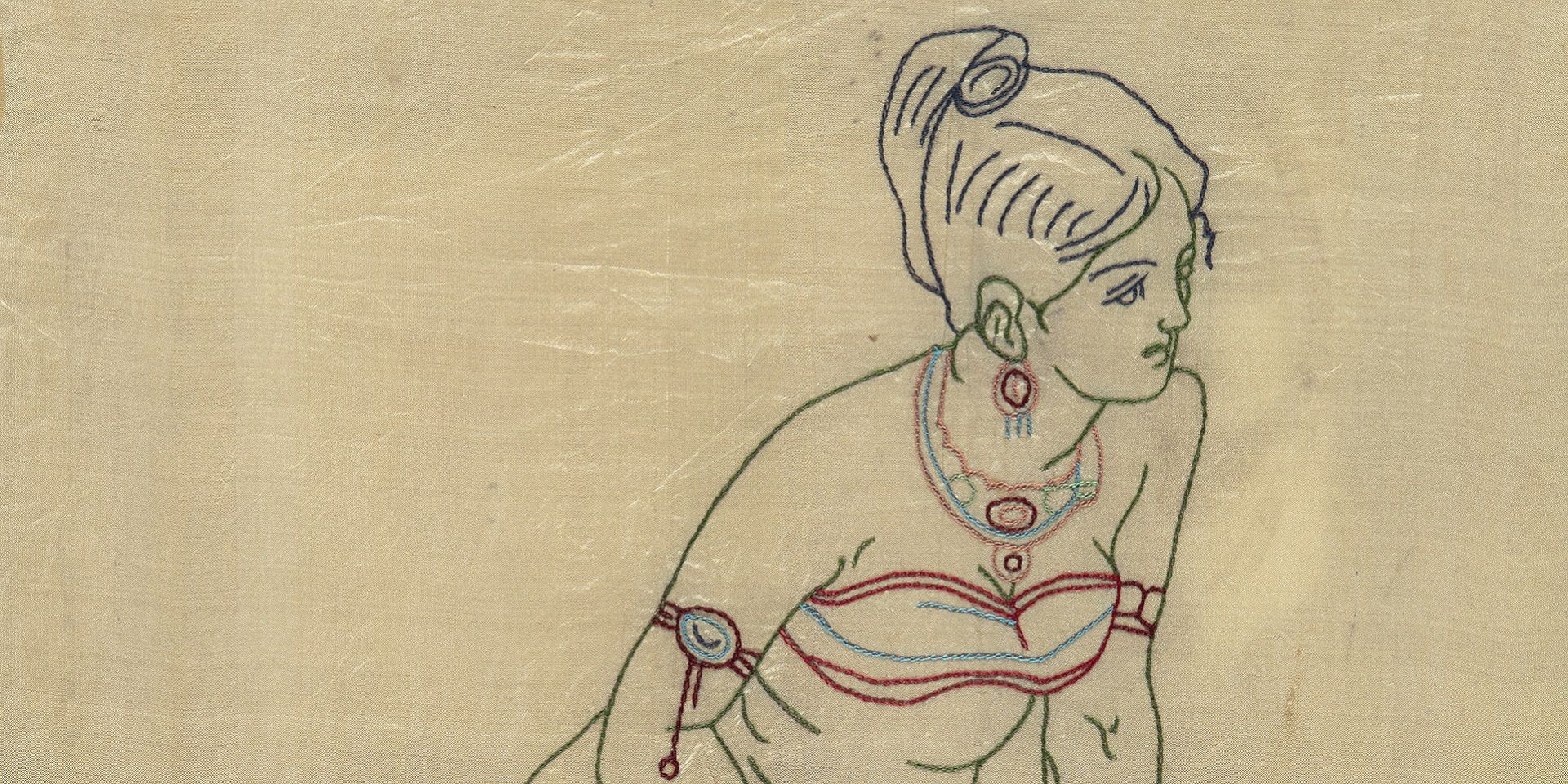

Together, we also worked on the structure of the book, which ended up having five distinct layers. First, there’s the main text—the narrative itself. Then there’s Amrita’s artwork. We also included a layer of historical and contextual information: who the Impressionists were, what the Mattancherry murals are, what was special about Ajanta, and so on. Then there are the family photos—images taken by Amrita’s father and other relatives. And finally, of course, there’s Kalyani’s art. Our challenge was to weave these five layers together cohesively—so that nothing felt out of place or disconnected. It took a lot of effort, but I think we succeeded in creating something that feels unified and engaging. It was an intense process, but also incredibly rewarding. And in many ways, we were developing the format as we went along—discovering what the book wanted to be while making it.

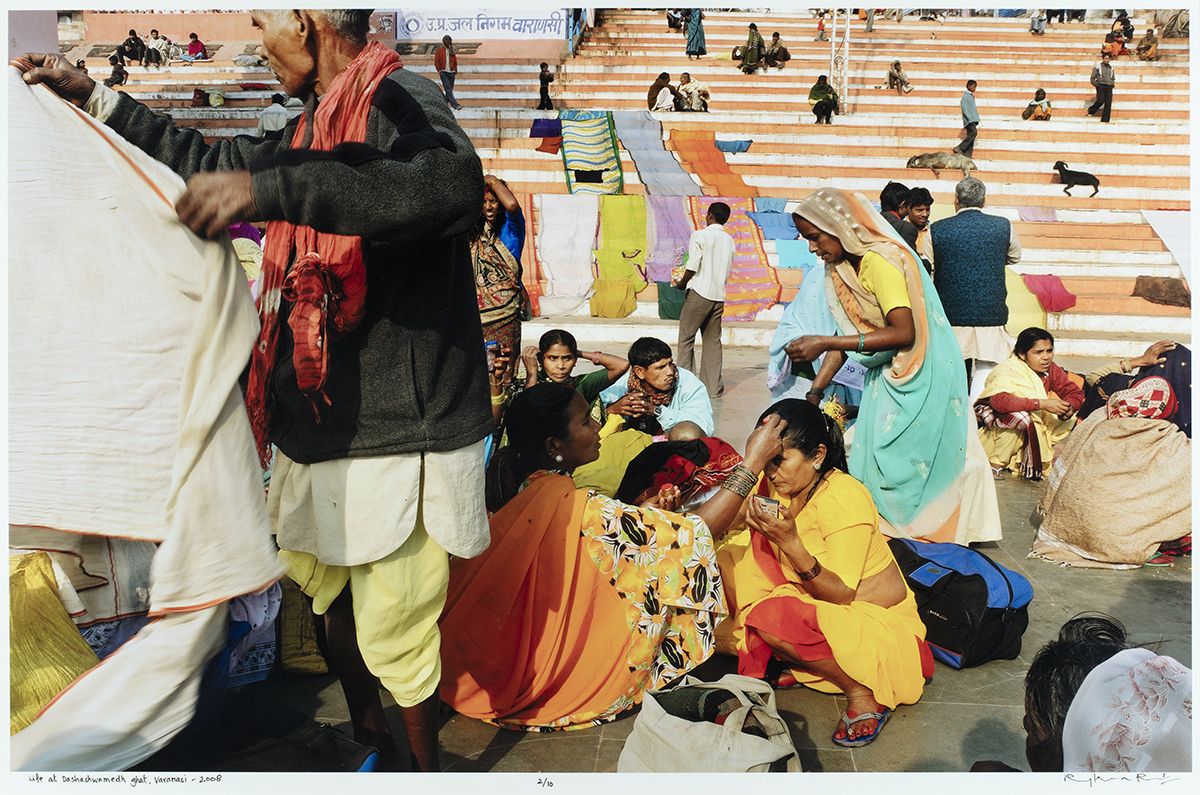

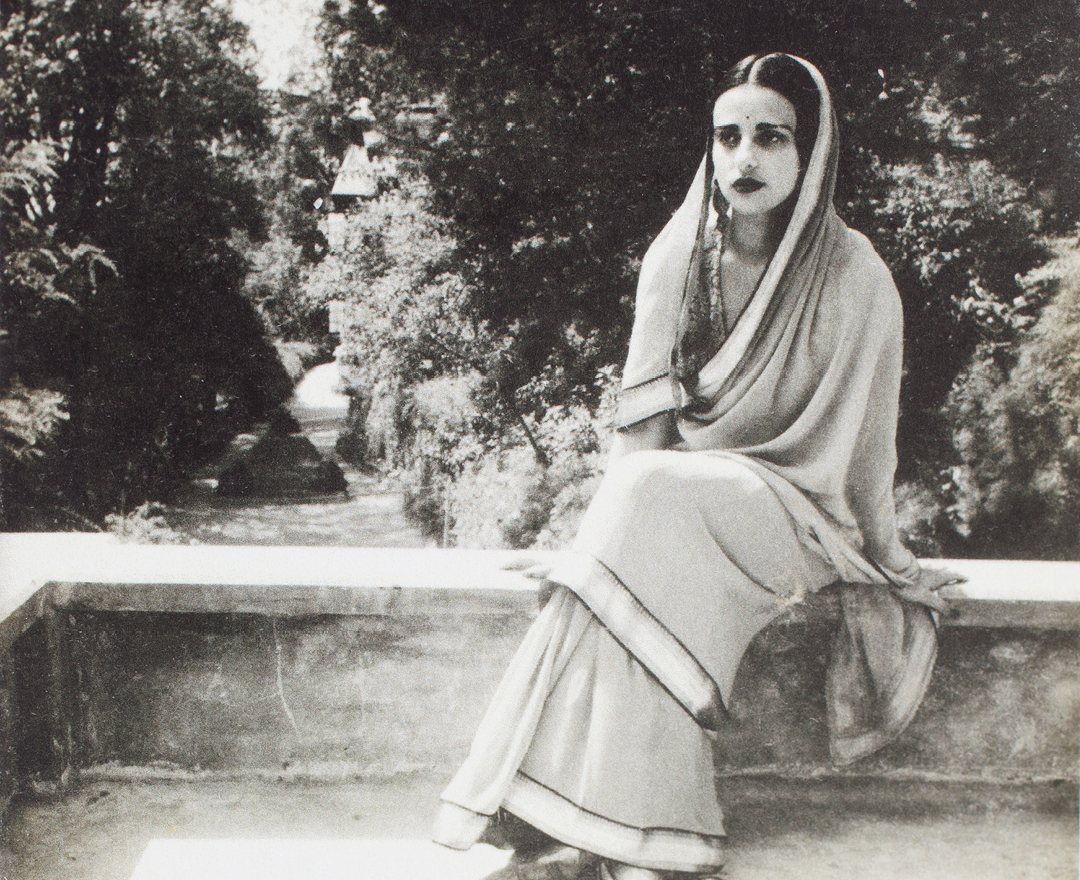

Amrita Sher-Gil at her Lahore exhibition, 1937. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Q. The book generously showcases a lot of images and artworks from Sher-Gil’s early life—including her own drawings, photographs and particularly the image of a sculptural cast made of Amrita and her sister by a visiting artist; how did this collaboration with Sher-Gil’s archive take place? And why do you think the story of Amrita’s life is important for children today?

Anita: I drew heavily from Vivan Sundaram’s work and support—especially the two volumes he put together (Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self-Portrait in Letters and Writings, Tulika Books, 2010).

Vivan’s help for my project was invaluable. He was always ready to answer my questions, ready to point out sources in his book or outside of it that would help, and to read my drafts. His guidance was a huge relief for me, especially since I was most interested in Amrita’s childhood. The material he had gathered on that period was so rich, and I was incredibly grateful to be able to use it. He also helped with permissions, which was a big part of the process. We were very particular that every painting used in the book was properly sourced and credited. Vivan connected me to the sources for every single painting, which made the whole process so much smoother. My publisher, Harper Collins India, and my editor, Tina Narang, also went out of their way to support the presence of Amrita’s paintings in the book.

The very first spark for this project came back in 2015—or maybe even a bit earlier—when a publisher sent me a list of people they were considering for a series on pioneers. And I noticed two glaring things right away: first, there wasn’t a single woman on the list. Second, there wasn’t a single visual artist—except for Hergé, the creator of Tintin. They asked me, ‘Is there anyone here you’d like to write about?’

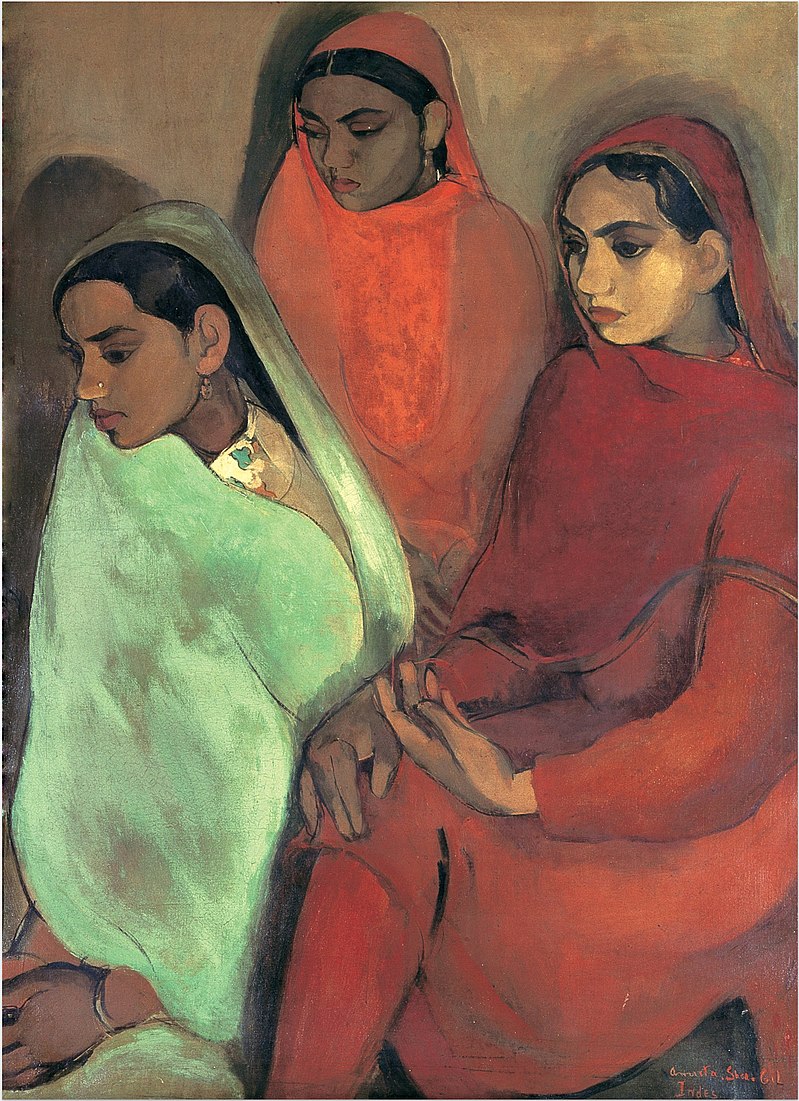

I appreciated that they were open to suggestions, because I responded, ‘Actually, I’d like to write about an Indian artist—and a woman. Would that be okay?’ And to their credit, they said yes. My sole point of entry—the only reason I even thought of Amrita Sher-Gil—was a painting of hers I’d once seen in a museum: Group of Three Girls. That painting stayed with me. I didn’t know much more than that, but I knew I wanted to write about the artist behind it. So initially, the motivation was simple: I wanted to tell the story of an Indian woman artist. And as I started researching her, it deepened into wanting to understand this woman artist and represent her practice.

|

Amrita Sher-Gil, Group of Three Girls. Image courtesy: NGMA and Wikimedia Commons |

At that time, most of what you could find online about Amrita was focused on her sexuality. There was so much prurient, judgmental content, so much misinformation. Sure, there were some books on her, and serious institutions had written about her, but that material was geared entirely toward adults. And what was missing was something accessible that focused on her art, her process, her life as an artist—for younger readers.

So that became my mission: to write about Amrita in a way that was true to her work and her artistic journey, not distorted by gossip or reductionist narratives. Even as someone just beginning to learn about her, I could tell how skewed the public discourse was. If she had been a male artist, the gaze would have been entirely different. I started (researching) with a book by N. Iqbal Singh, who was a close friend of Amrita’s. Then I found Vivan’s book, which felt like the most expansive and empathetic view of Amrita. It included so much about her childhood, her family, her parents, and even the larger extended family. It gave context, warmth, and a depth of understanding that felt like a solid foundation to build on. I also read Yashodhara Dalmia’s biography, which is an excellent book, but many of the intimate, formative anecdotes—especially from her early years—came through Vivan’s work. His perspective gave me the kind of access and emotional grounding I needed to begin telling her story in a new way.

Q. How does one translate a difficult narrative like Amrita’s life and art—almost indissociable from complex questions around a counter-intuitive narrative of colonial encounters and European modernism—into material for a children’s book? How does one begin to penetrate through the normative textbook treatment of broad historical formations that the narrative of Amrita’s life challenges?

Anita: Let me separate this into two parts. First, I’d like to address the question about colonialism, and then I’ll come to how we approached the more difficult aspects of Amrita’s life, which you asked about later.

Looking back, what struck me most was how deeply Amrita’s life was shaped by the many facets of colonialism. It was everywhere—woven through her family, her education, her career, and even her personal relationships. Take her father, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. He was openly critical of British imperialism and wrote anti-colonial articles, which led to the British confiscating his property and objecting to his return to India. His brother—who had set up a sugar mill in Saraya near Gorakhpur and was a member of the viceroy’s imperial legislative council—intervened on his behalf. That dynamic within the family itself reflected a split: one branch more aligned with colonial power and wealth, and the other, living more modestly, almost genteelly, in Shimla, a colonial hill town.

|

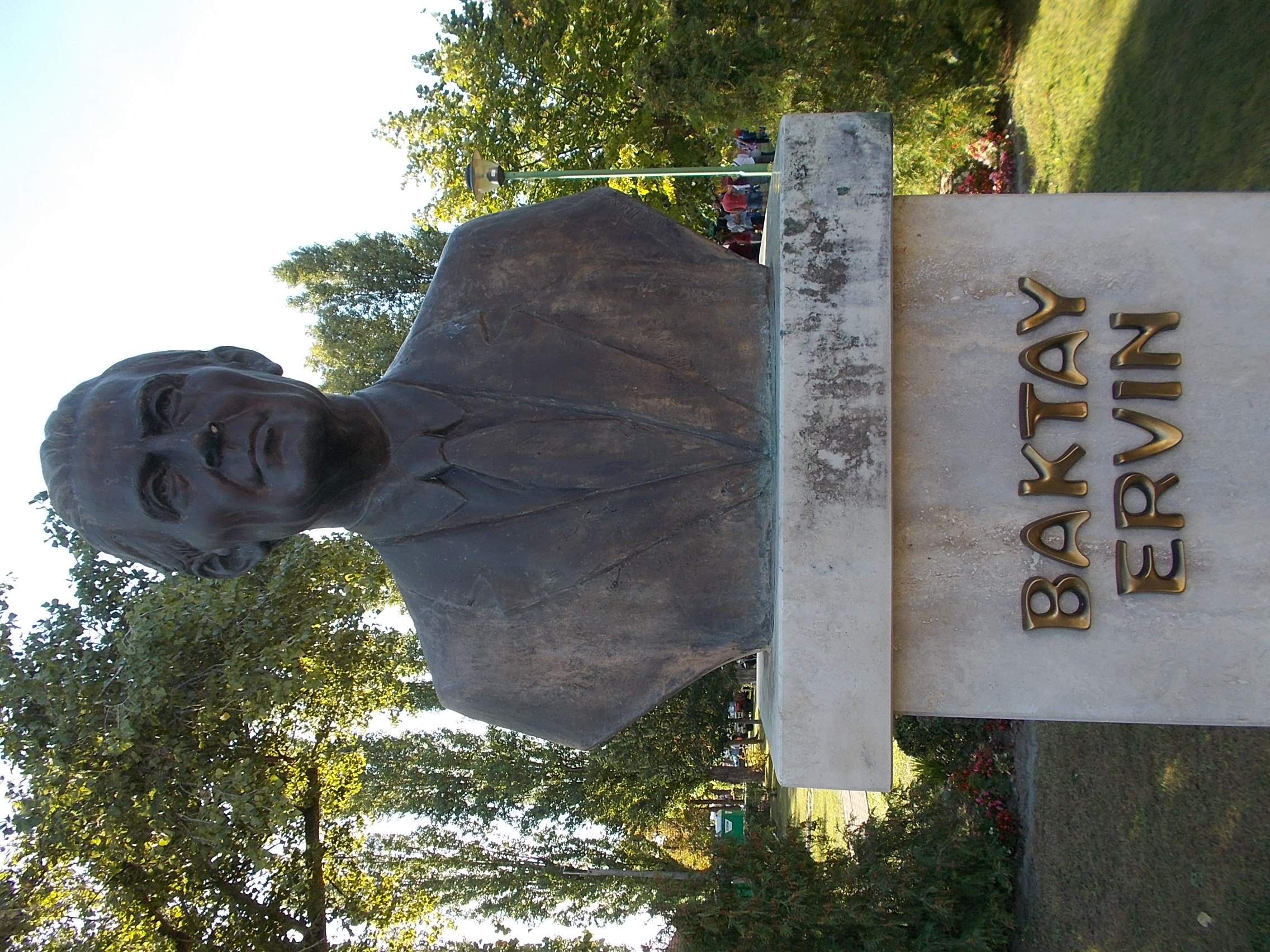

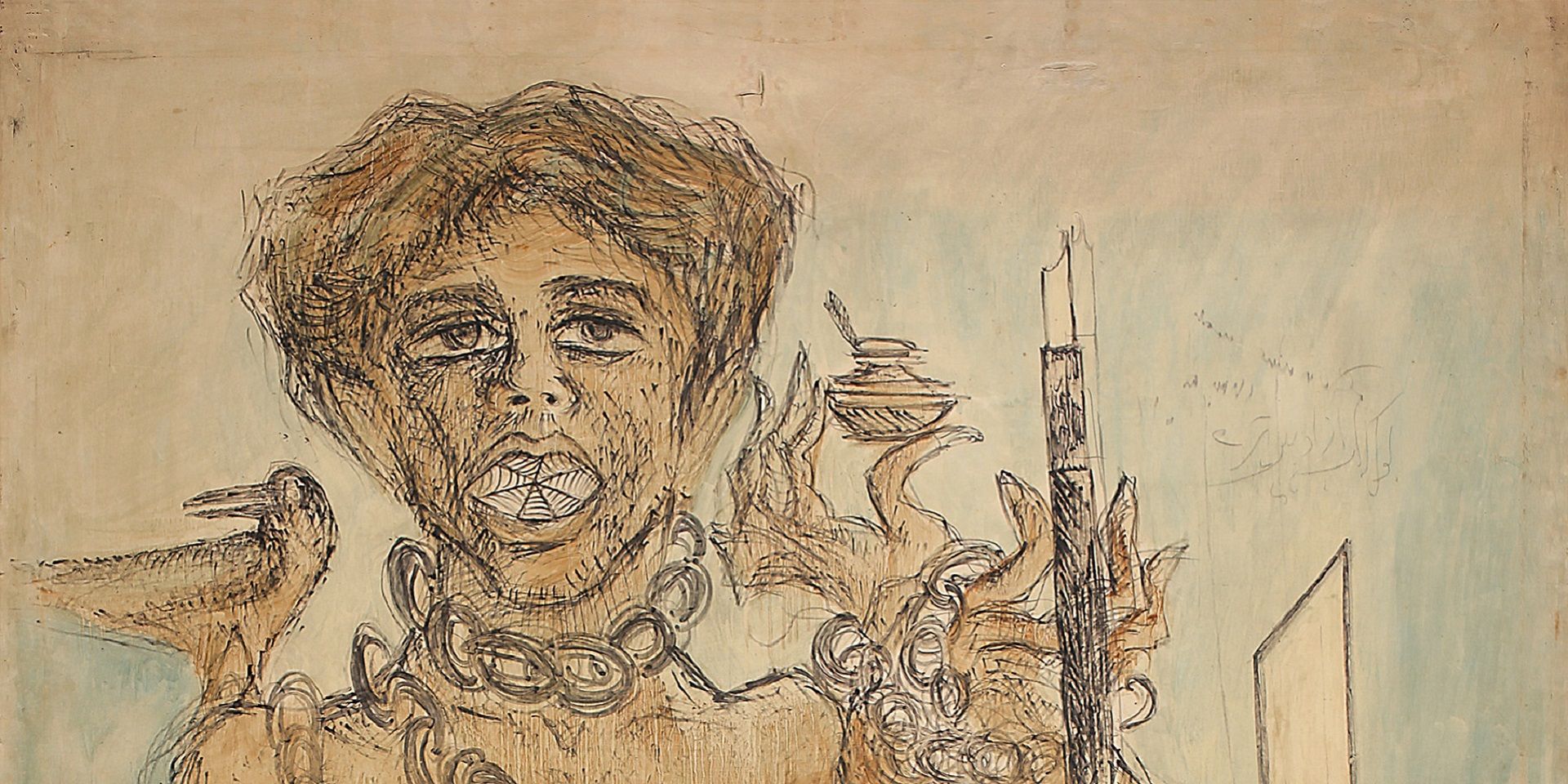

Béla Dominonkos, Ervin Baktay. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

From a young age, Amrita was recognised within her family for her artistic talent. One significant turning point came when her uncle from Hungary, Ervin Baktay, visited them. He had trained under the artist Simon Hollósy, who had formed the Nagybánya artists’ colony. He noticed she was copying posters and popular images, and told her, ‘Draw the people around you. Draw from life.’ He introduced her—quite radically for the time—to the idea of depicting ordinary people around her, the people who did the labour. That was a huge moment. He was also an Indophile, a Sanskrit scholar, a yoga practitioner—a kind of polymath who brought a different worldview into her life.

Later, when Amrita married her cousin Victor Egan, her mother strongly opposed the match. Although she had raised her daughters to be independent and self-driven, she still hoped they would marry ‘well’. Victor, in her eyes, did not meet that standard. As a result, she shut her doors to the couple. But once again, the uncle’s side of the family stepped in—they supported the marriage, even commissioned Amrita’s work, and encouraged her artistic career.

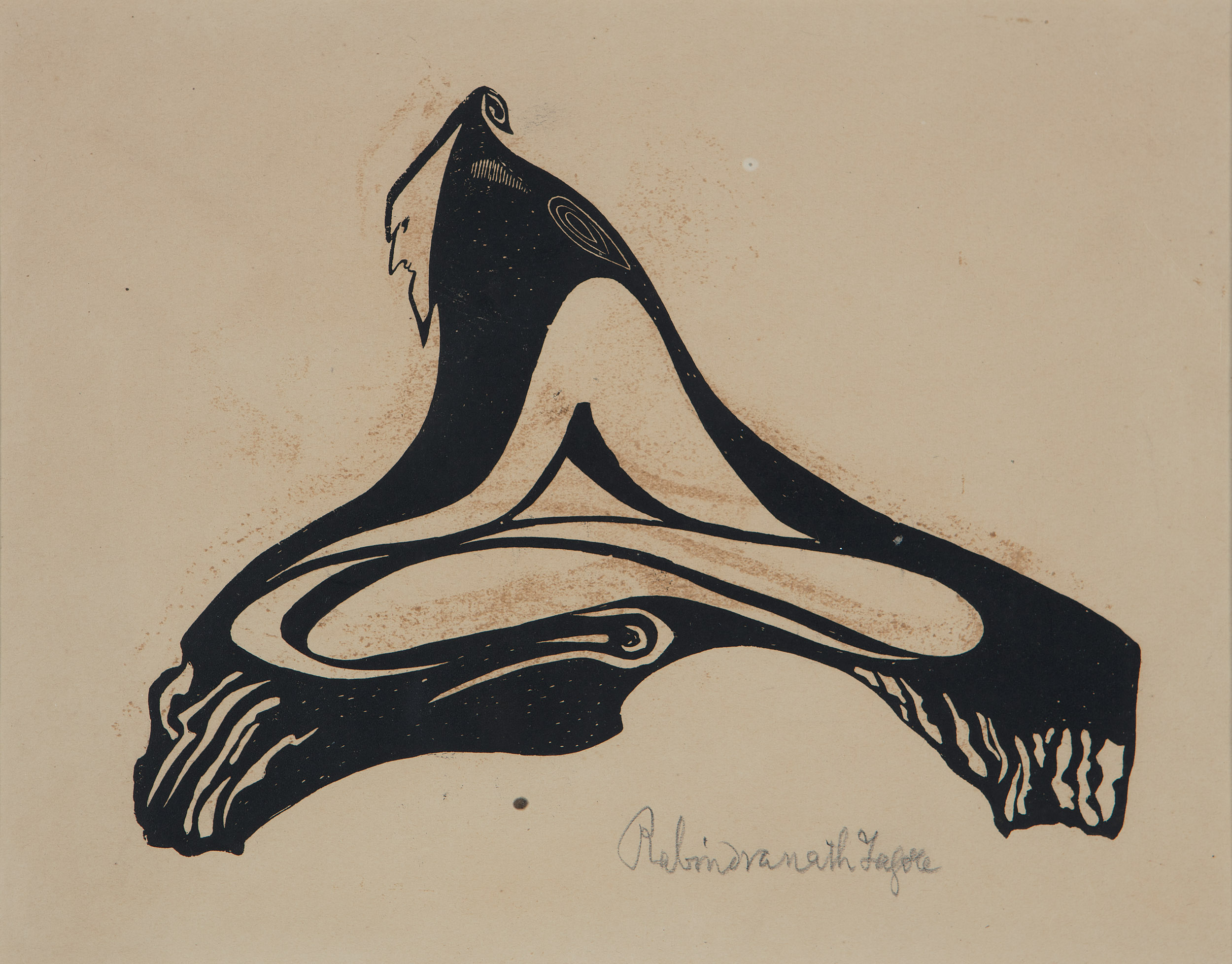

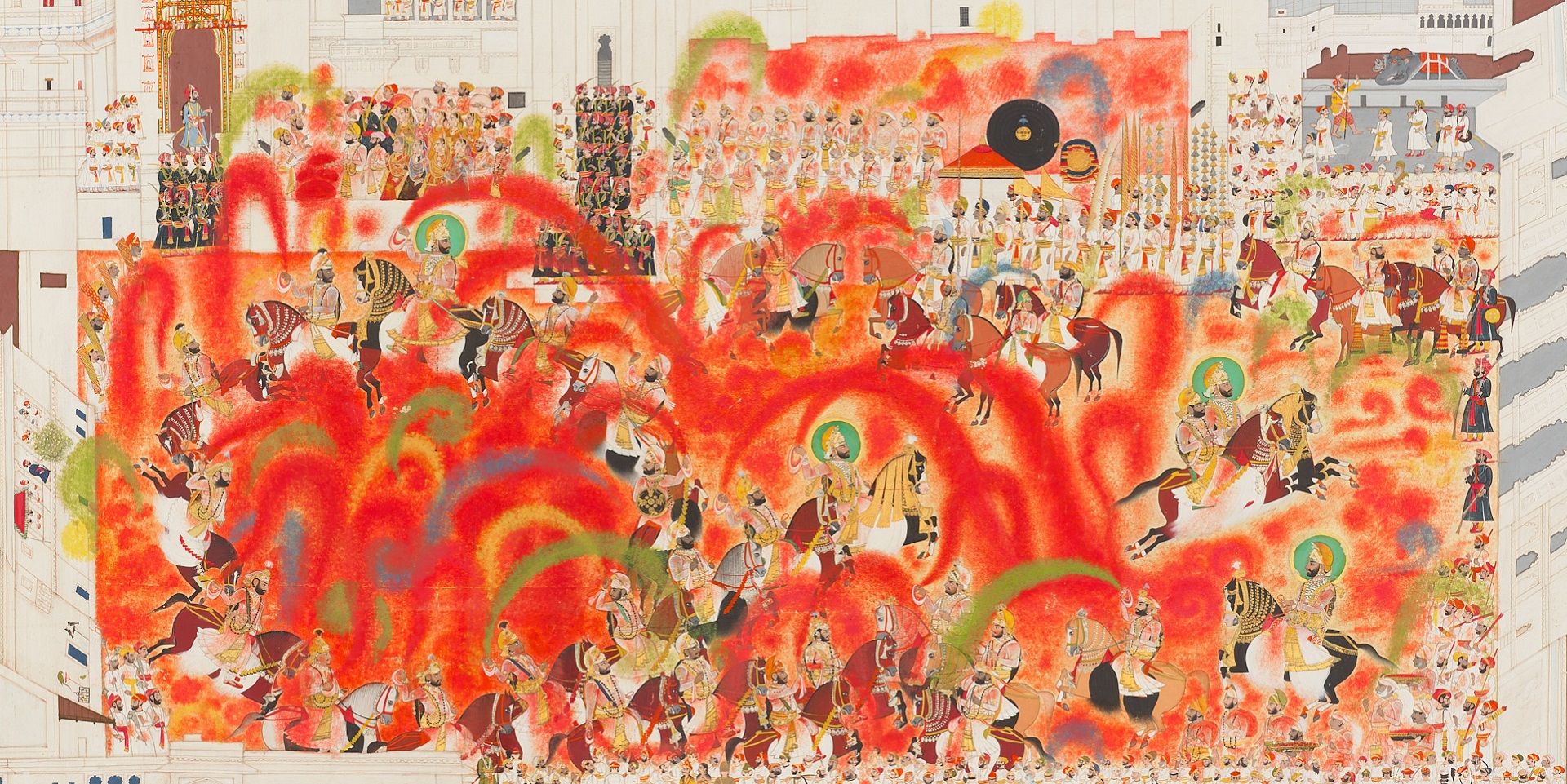

So, throughout her life, Amrita was navigating and reacting to different expressions of colonialism—political, cultural, and familial. She was exposed to it, shaped by it, and often pushed back against it. For example, when she saw the Nizam’s art collection in Hyderabad, she was sharply critical of it. She was dismissive of the Bengal School, though she admired Jamini Roy. And interestingly, she preferred Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings over his writing—which her father couldn’t understand at all. But of course, we now recognise the importance of Tagore’s art in its own right.

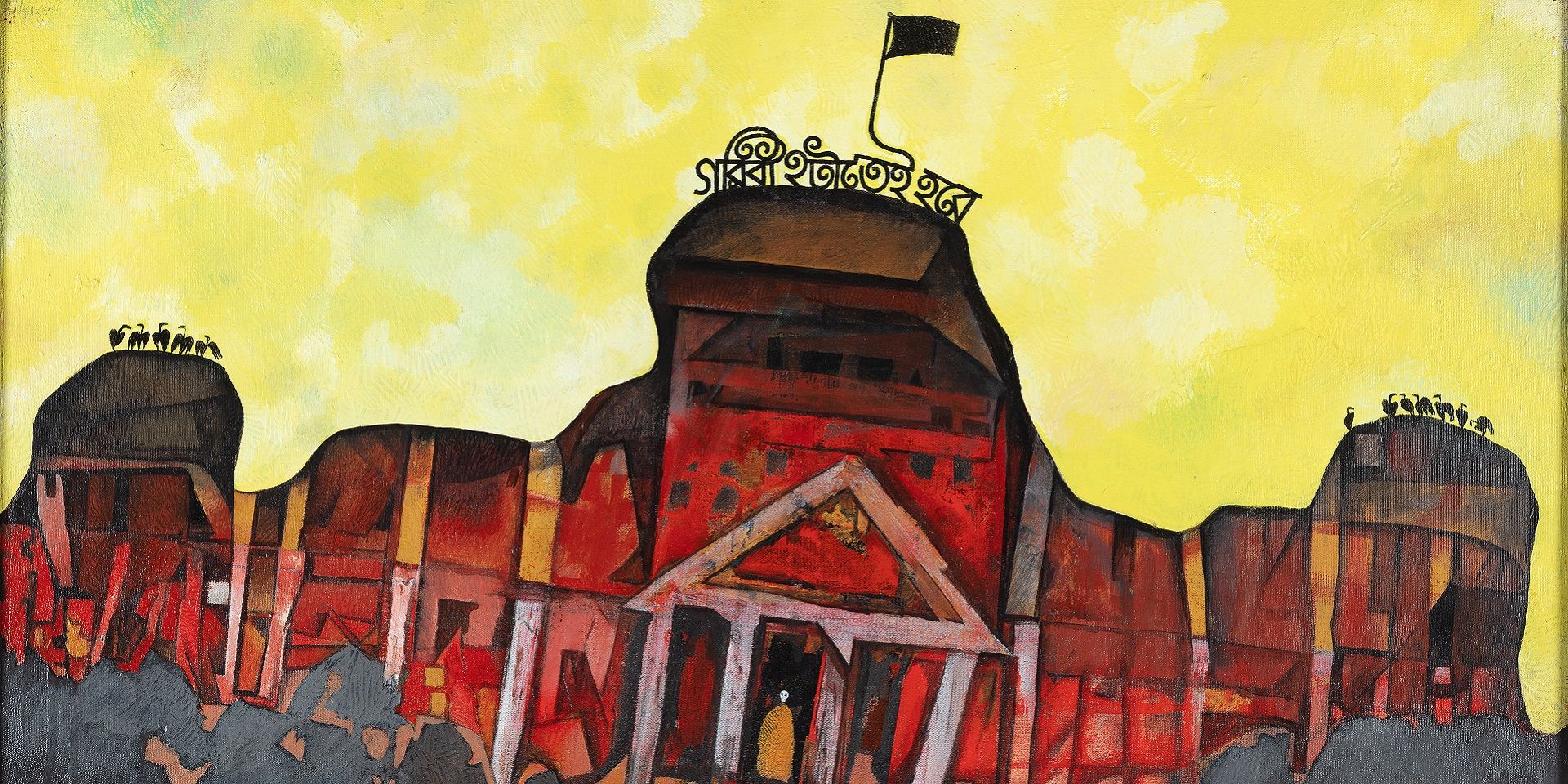

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled (Namaz), c. 1930s, Woodcut on newsprint paper, 8.7 x 11.2 in. Collection: DAG

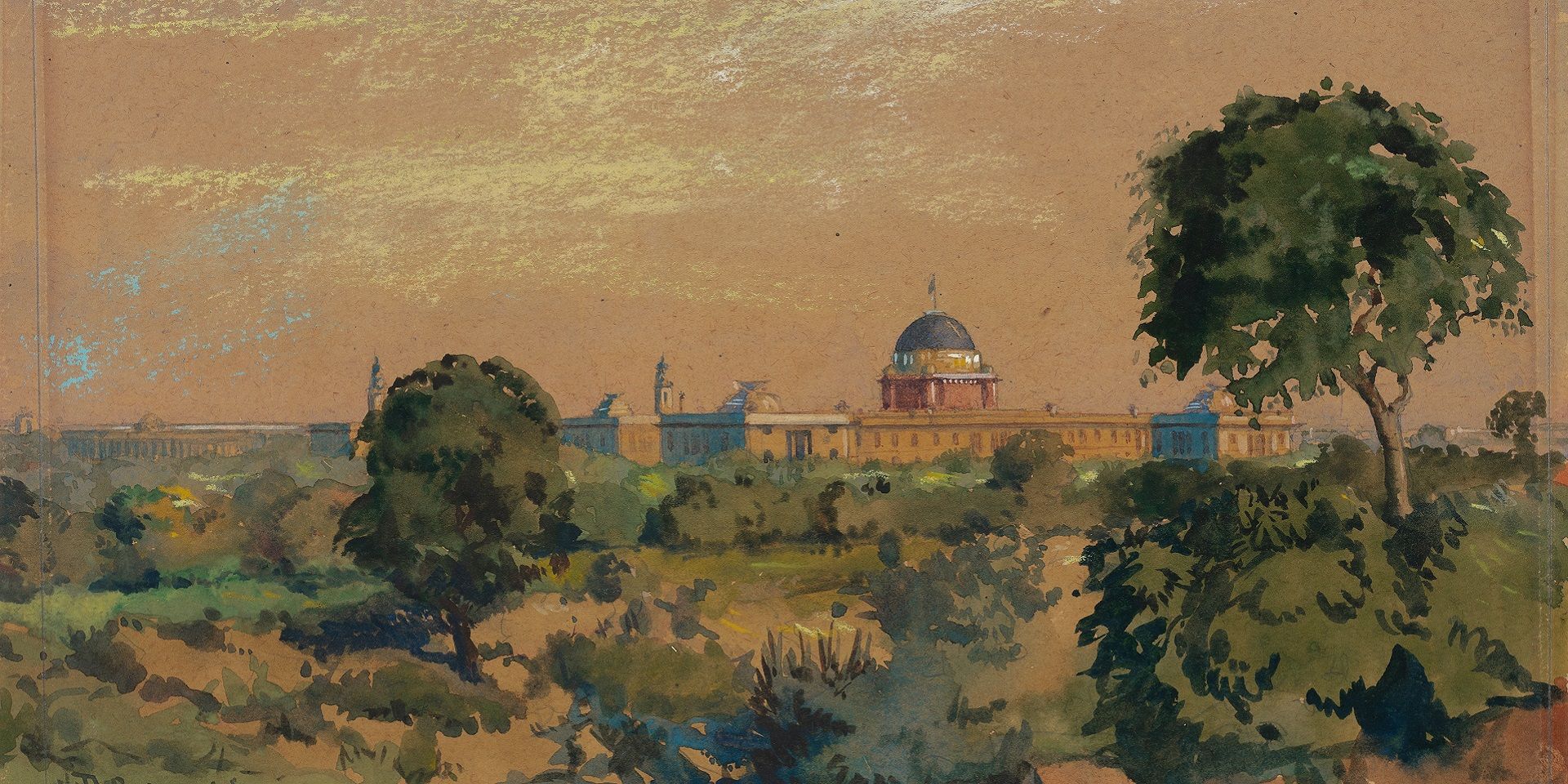

Eventually, Amrita chose to live in Gorakhpur with Victor, where he worked at the sugar mill and she painted. Life was comfortable. But she wanted to be in Lahore, where the anti-colonial cultural movement was thriving—artists, poets, thinkers were coming together, resisting British rule. That’s where she moved next, and that’s where she found a creative and intellectual community. Tragically, that is also where she died suddenly of complications likely related to dysentery.

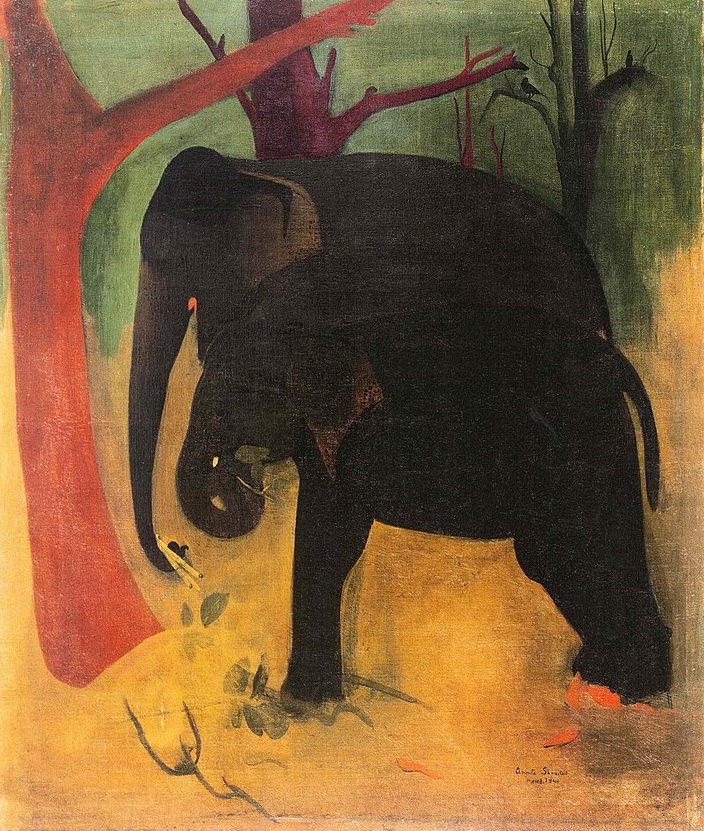

To me, her life was a constant back-and-forth—a negotiation between privilege and resistance, between the comforts of a colonially shaped world and a desire to break free from it. Even small details reflect this complexity. For instance, when Amrita painted elephants, they were often those that belonged to her uncle and were posed in their compound so she could paint them from life. That’s the kind of support she had, even as she mentally wrestled with the structures that made such gestures possible. All of this leads me to say: when telling the story of someone’s life—especially to children—you cannot leave out history and geography. These elements shape our lives in ways we often don’t even realise. So no, storytelling without history and geography is, in my view, a lost opportunity. In fact, kids respond to these elements far more strongly than we expect.

|

Amrita Sher-Gil, Elephants, 1940. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Q. How have readers—especially the intended, younger readers—responded to the book?

Anita: Interestingly, this book actually began with a moment of feedback—long before it was even fully conceived. At that early stage, I had ordered a set of large art prints from the National Gallery of Modern Art (N. G. M. A.), and one day, my daughter—who was around seven or eight at the time—had her friends over. I happened to be looking through the prints when the kids gathered around, curious to see what I was doing.

They studied the paintings very seriously. After a while, they said, ‘These ones are very good,’ pointing to Amrita’s early academic work. Then they asked, ‘If she could paint like this, why did she paint like that?’—referring to the flatter, mural-like-style work she later developed. I was both amused and fascinated by their sharp observations. It struck me because, by then, I already knew that Amrita herself saw her academic paintings as her weaker work. And yet, here were these kids praising what she had dismissed, and questioning her more evolved artistic style. That moment immediately gave me a sense of direction. I realised two important things: first, that I needed to respect the arc of Amrita’s artistic evolution; and second, that I had to create space for the young reader’s own responses—even if they differed from the artist’s perspective. That encounter also made me very clear on how I wanted to present her artwork. In many traditional art books, the bulk of the text is in black and white, with a single colour section in the middle showing all the images. But I knew from that day that I didn’t want to follow that format. I wanted the art to appear with the narrative, right at the moment when Amrita was making it—so the reader could see her work evolving in real time alongside her story.

|

Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-portrait 5, 1932. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

And the feedback continues to amaze me. Apart from the ones that respond to Amrita’s art warmly, there are others that are interesting. Just recently, a reader of Cypriot origin from the U. K. told me she was reading the book to her nephews, aged five and seven. They became completely fixated on the phrase freedom fighter. They kept asking: ‘What is a freedom fighter? Were there any in our family? Why weren’t they free? What is war?’ Being from Cyprus, a country with its own colonial history, the term struck a deep chord. I love that the book opened up that line of questioning. Another reader, the mother of a twelve-year-old, wrote to tell me that she and her daughter had been quarantined together during COVID and had read the book. They were fascinated to learn that Amrita herself lived through a pandemic in 1925. That recognition felt comforting and meaningful to them. These are the kinds of conversations I had hoped the book would spark. My aim was always to show how history and geography shape not just the course of an artist’s life, but the very nature of their work. And I’m glad to see that both children and adults are picking up on those layers.

The book closes with Amrita’s death, and I intentionally chose not to add more sorrow by including the later suicide of her mother. Ending there allowed space for readers to absorb Amrita’s life without overwhelming them. What I wanted most was to show her complexity—she could be sharp and difficult, but also fiercely alive, curious, and constantly seeking. She didn’t stay confined to books; she travelled to Aurangabad, Kochi, Madurai pursuing art in its living context. In Hungary, she explored Jewish collections with a friend who admired her. This active engagement with the world is what I wanted to highlight—her restlessness, her questioning spirit, and her refusal to be a passive observer. Amrita felt deeply modern, deeply human. I didn’t want to reduce her to a label or symbol. I wanted young readers to see a real person—alive, flawed, passionate—someone they could connect with and perhaps even see themselves in.

Unidentified Photographer, Amrita Sher-Gil. Collection: DAG

*Vivan Sundaram was Amrita Sher-Gil’s nephew

’Conversations with Friends’ is a series where we speak with inspirational figures from the art world who are working behind the scenes

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

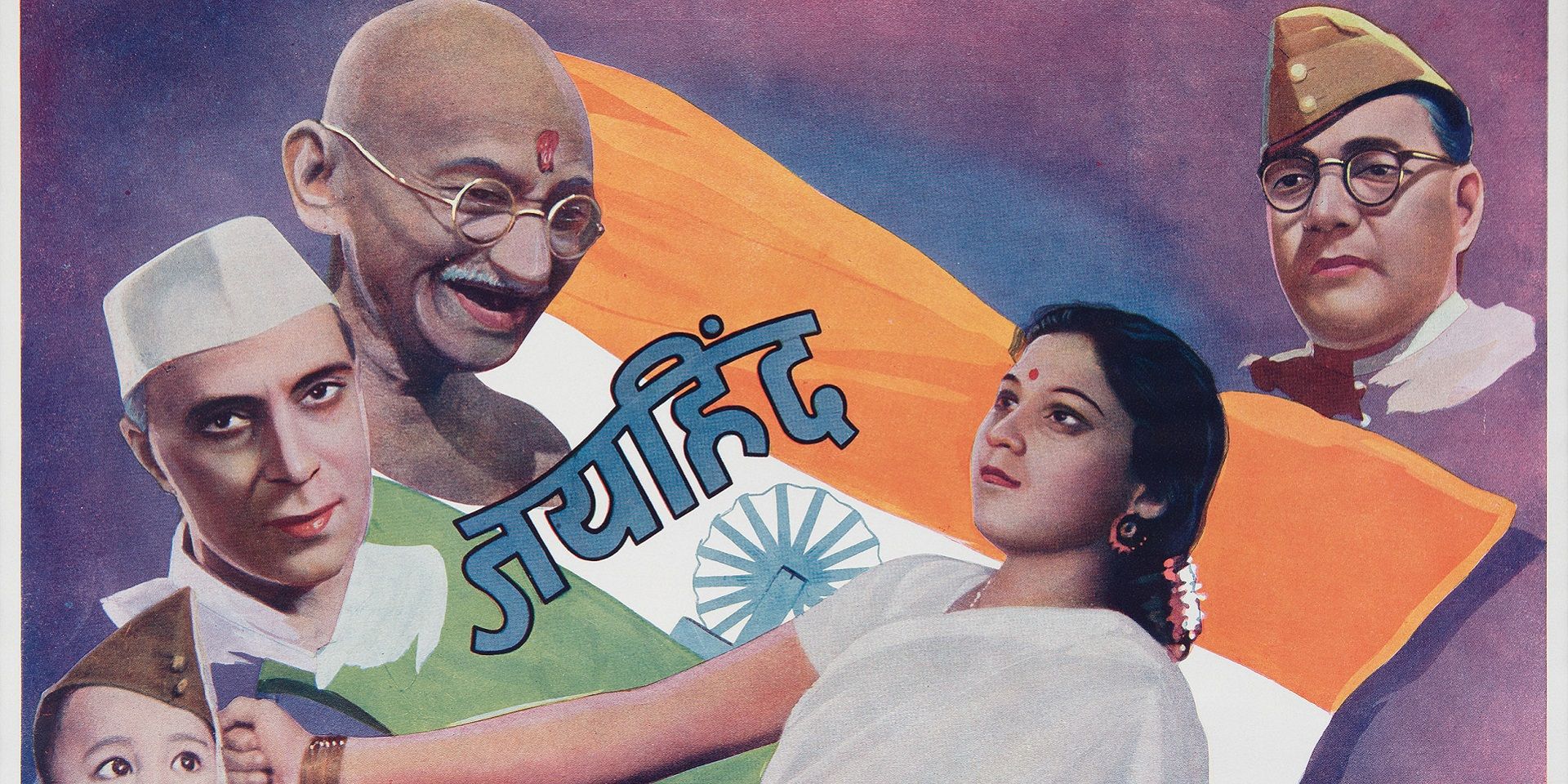

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025