Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Building an Empire:

A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Johz Gantz, Madras beach and Custom House, 1805, Watercolour and graphite on paper pasted on mount board, 36.1 x 53.3 cm. Collection: DAG

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones is one of the foremost historians of colonial India including Awadh under nawabi rule.

She has written on architecture, culture and personalities animating these lost worlds. In her new book Empire Building: The Construction of British India, 1690-1860, she focuses on the larger project of building works in the period when colonial rule was attempting to establish itself in a location that was far from the home comforts of Europe, in terms of climate, availability of material, labour, knowledge and security. The book draws our attention to the work done by several generations of engineers attached usually to the military corps of the British East India Company, who innovated new spaces and structures, from post and telegraphs offices, cantonment towns and railway tracks to hill-stations, filatures, observation towers or semaphores, and fortified settlements. She discussed the book with the editor of the DAG Journal and Giles Tillotson, a historian of architecture and DAG’s Senior Vice-President of Exhibitions. An edited version of the conversation appears below.

Thomas Daniell and William Daniell, View on the Chitpore Road, Calcutta, Handtinted engraving on paper. Collection: DAG

Q. The book seeks to highlight the work done by military and later, civil, engineers working for the British East India Company, who weren’t always trained in architecture schools or even engineering institutes. How do you think they prepared for their work, besides employing local workers and planners? What do you think is their legacy for architectural thinking in the subcontinent?

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones: Well, a significant number of them had to learn on the job as they lacked formal training. While apprenticeships existed, individuals might be apprenticed to someone with practical construction experience. However, until the late 18th century and the early 19th century, there was a notable absence of systematic training. Notably, none of these individuals were civil engineers, a term that only emerged around 1820. The Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers, established in 1771, intentionally adopted the term civil engineering instead of military engineering. However, the field didn't gain momentum until well after the period I'm discussing, around 1860. Consequently, we are predominantly dealing with military engineers, covering a broad spectrum of subjects.

For instance, Robert Barker, who eventually rose to the rank of general, found himself tasked with fortifying Fort William in Kolkata against a potential invasion by Nawab Sirajuddaulah. However, he admitted to not knowing what he was doing, illustrating the improvisational nature of much of their work during that period.

Giles Tillotson: I wanted to ask about the potential role books might have played in educating or offering expertise to these early engineers. In 18th-century Britain, many esteemed architects like Gibbs and Colin Campbell published plans, including the comprehensive "Vitruvius Britannicus." These plans covered well-known public buildings and private palaces in Britain. However, is there evidence of similar books being available to engineers or amateur engineers working in India?

Rosie: I certainly know that they were available in private libraries. I've gone through Claude Martin's library in great detail, and there are a serious number of books. ‘The Builders Magazine’ was a very popular one. But I think it is probably unlikely that they were available to engineers. I think there was a great difference between connoisseurs and people like Martin, and the ordinary sort of engineer in the field, so to speak. I think they certainly would have seen plans, but to see a plan of a building doesn't necessarily enable you to build it. So I think there was a gap. Certainly, some people would have had access to books, but I think not the majority of the people we are talking about.

Giles: I believe it's Philip Davis who emphasizes the notable occurrence of churches in India with steeples positioned over the front portico, specifically at the west end, rather than the traditional east end. The immediate precedent for this can be traced to St. Martin-in-the-Fields by (James) Gibbs, where he strategically placed the steeple at the west end facing Trafalgar Square to make a prominent statement. Essentially, he shifted the steeple from the east end, where it would have had less impact, to the west end. This then serves as a kind of model for churches in India since Gibbs published his plans, likely in the early nineteenth century. It's a fascinating concept that a particular model, born out of a highly site-specific reason, becomes translated to India. And it all seems easier to copy an existing building than to do something from scratch. I think that had a lot to do with it, too. I certainly think St. Andrew's Kirk (or, Church) in Calcutta is based on St. Martin-in-the-Fields.

Henry Salt, Calcutta, 1809, Engraving and aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 53.3 X 74.9 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. You have used the term ‘political architecture’ to characterize the broad process of colonial building projects; can you explain how such building projects—which included infrastructure projects like roads, railways and river transportation, along with post and telegraph offices—assumed a ‘political’ character?

Rosie: I wouldn't say the railways did. That was actually developed for entirely different reasons. When I refer to political, I'm usually alluding to structures like observatories, which undeniably make a statement. This marks a departure from the Mughal and post-Mughal concepts of observatories such as the Jantar Mantar. For instance, the construction of the Madras Observatory represents a distinct departure, serving slightly different purposes while making a pronounced statement.

Another example that could be categorized as political architecture is the massive silk factories or filatures that emerged across Bengal. This development was prompted by a new method for reeling silk from cocoons, necessitating additional equipment and notably larger buildings. If you examine some of the plans, they make a political statement as they consist of two or three stories, a departure from the typical one-story bungalows in the region. These structures are remarkably sizable and make a significant impact, clearly conveying a message that they are present with new ideas and technology. I would certainly classify filatures as political architecture.

Thomas and William Daniell, 'Jai Singh's observatory, Delhi', 1790, Watercolour and graphite on paper pasted on paper, 52.1 x 111.8 cm. Collection: DAG

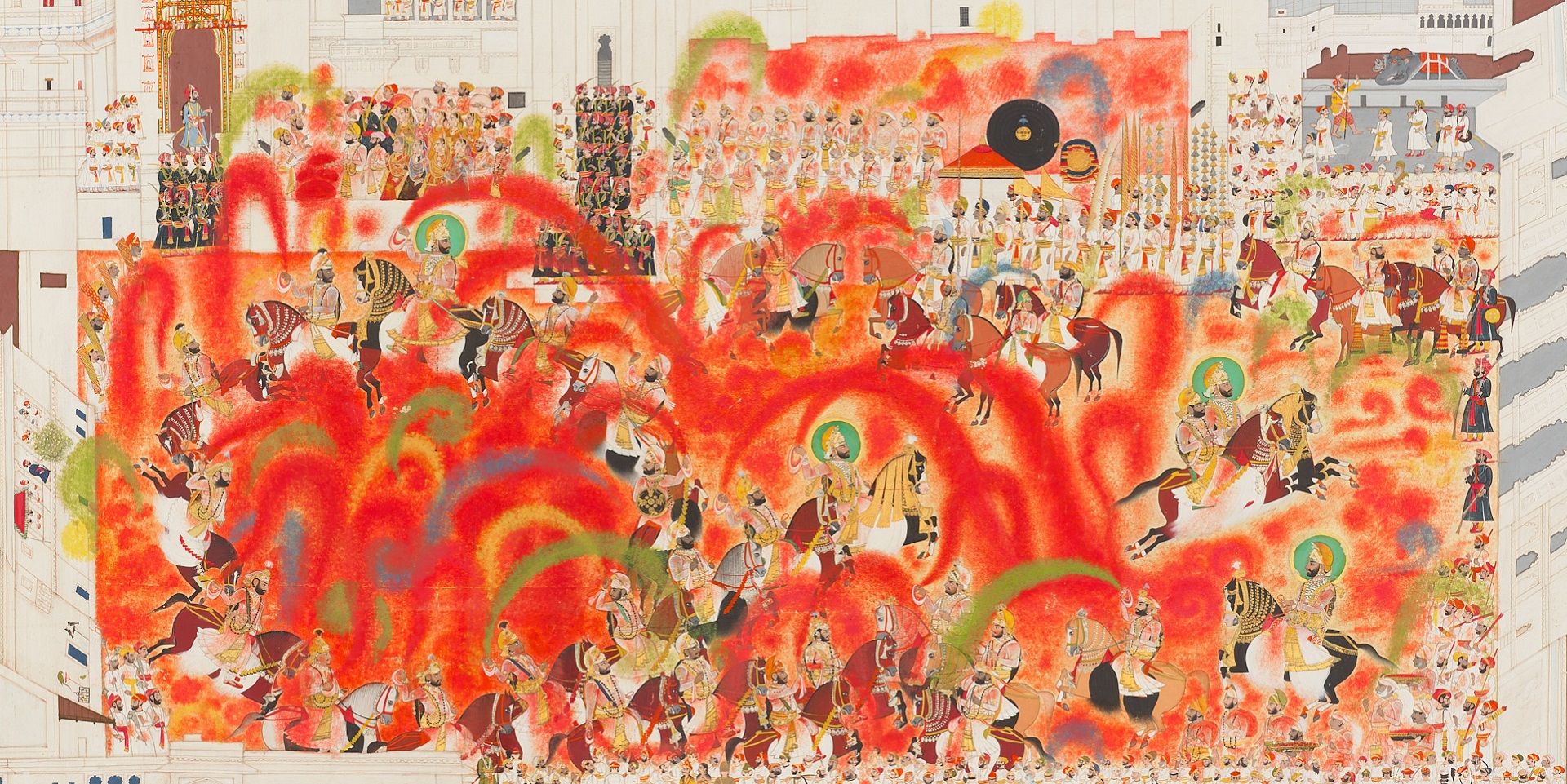

Giles: Presumably you could make the same point about the attitude expressed during Lord Wellesley’s tenure with that famous, often quoted remark, that (India had) to be ‘ruled from a palace, not from a counting-house; with the ideas of a Prince, not with those of a retail dealer in muslins and indigo’.

Rosie: That's right, but you've also got to remember that the directors (of the East India Company) were absolutely horrified at the cost, and they certainly hadn't sanctioned it, so it's very much Wellesley, you know, going off on a limb and allowing for the six months delay so he can start building before anyone says no. So I think that's an example of an individual political statement.

Giles: Oh, I see what you mean. You're making a distinction between state-sanctioned or board-sanctioned.

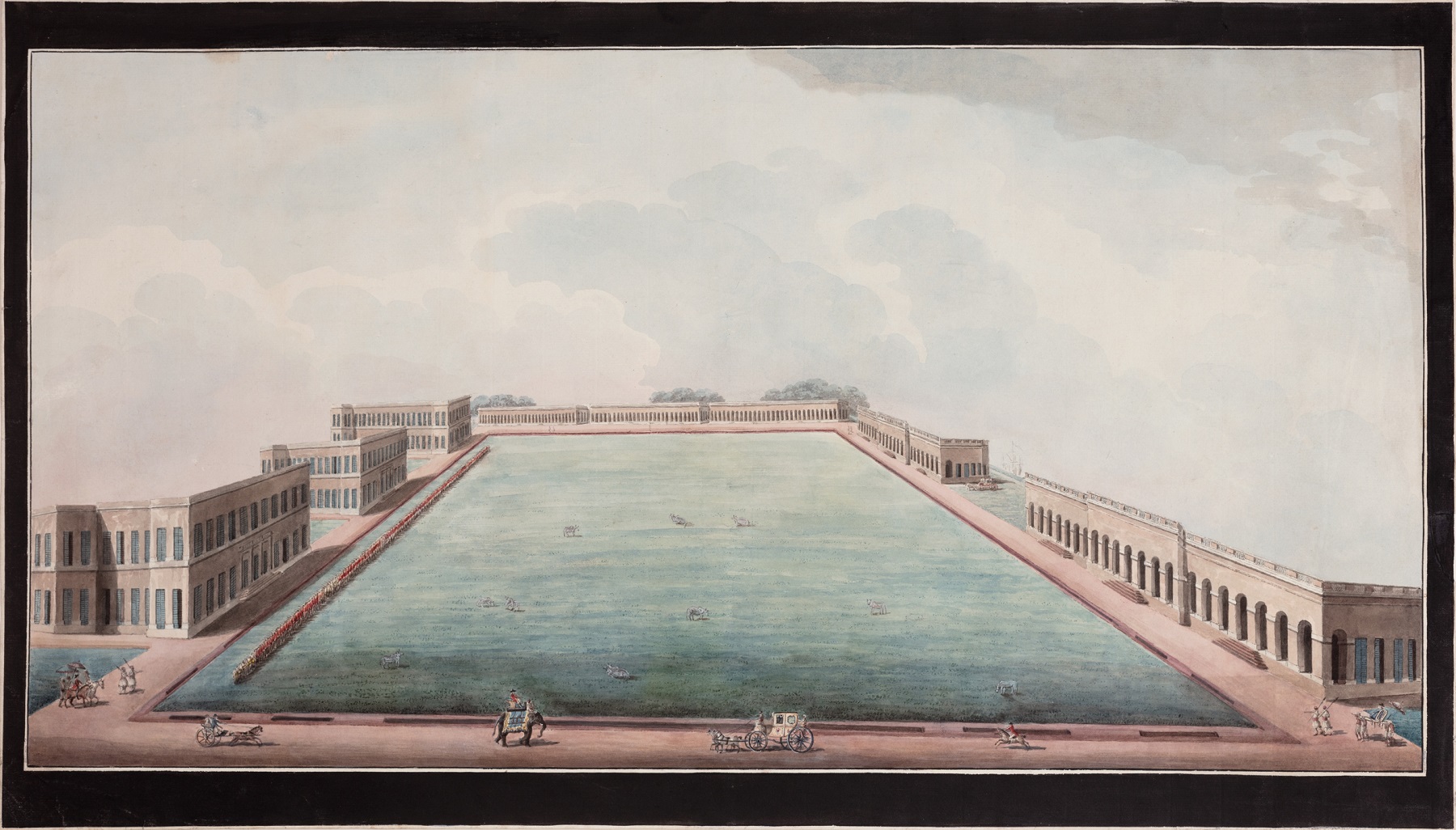

Anonymous (Murshidabad School), The Front View of Cossimbazar House, c. 1795-1803, Watercolour on paper, 35.6 X 52.1 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. You have quoted Edmund Burke to show how there was desire in Britain for colonialists to build spaces and structures in India. How did colonial officials, working on the ground, balance the demand for such architecture back home with integrating Indian design into such works?

Rosie: No, I don't think that's the case at all (that administrators would always look for this ‘balance’). Considerations of climate are crucial here. It's noteworthy that when the British began constructing structures, particularly beyond the main centers, like the Residency in Lucknow, it resembled a Palladian villa dropped into the heart of the Indian plain. This is evident in a well-executed painting by Sitaram. However, around 30 or 40 years later, modifications were made to adapt it to the Indian climate. Verandas, shades, and blinds were added, signalling a clear recognition that the original design was not suitable and needed adjustment. Similarly, some of the Europeanized palaces, while constructed, weren't well-suited to an Indian court. Notably, they lacked a central courtyard or a designated area for the women (zenana). It becomes apparent that simply transplanting English buildings to India is not as feasible as attempting to transpose an Indian building to England.

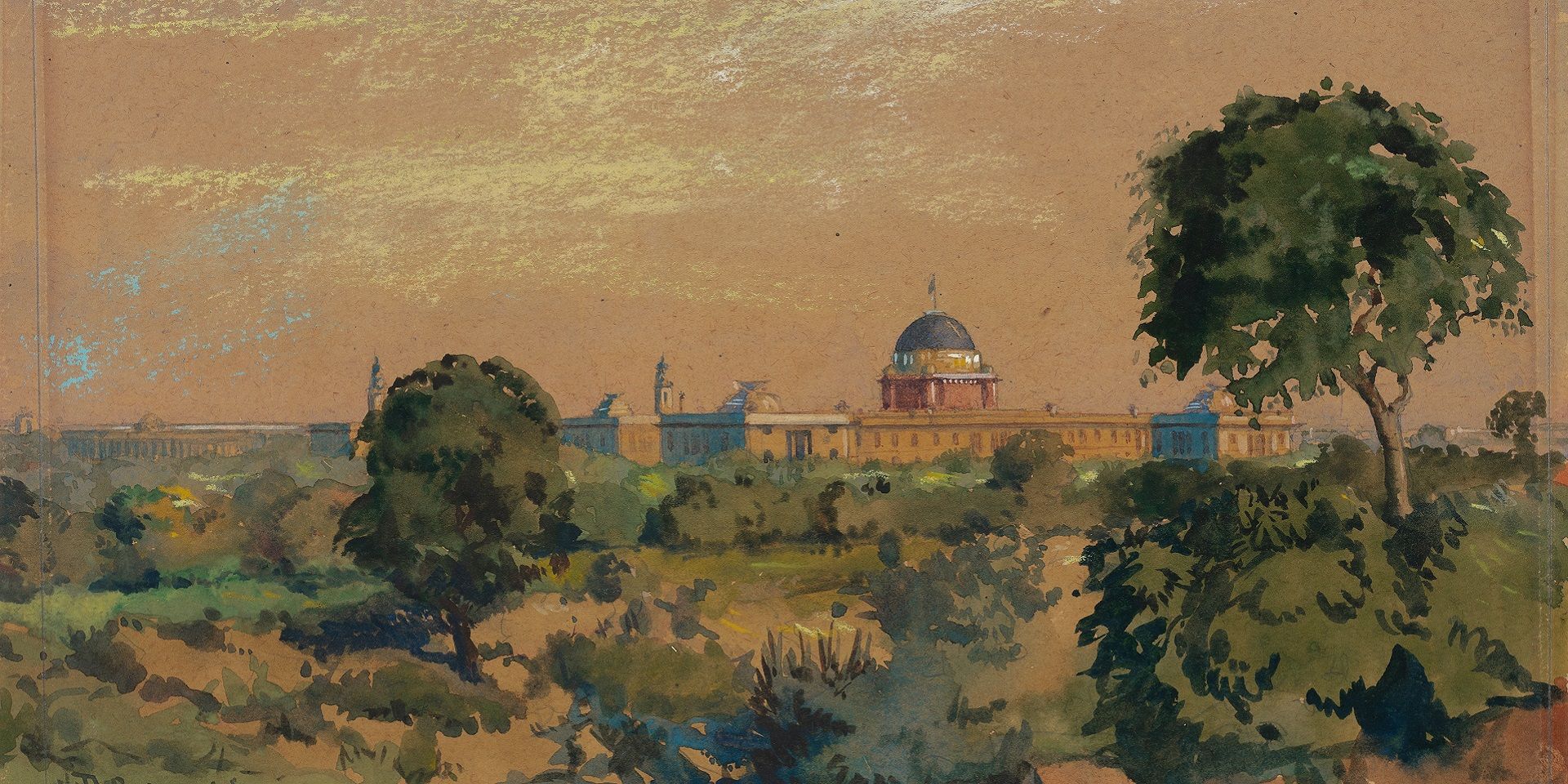

Giles: It's an interesting idea, isn't it? It comes up throughout the British period, as late as the early twentieth century when discussions around the building of New Delhi are being held. The advocates of a classical style, which of course included Lutyens, advocated on the ground that the Greco-Roman style is from southern Europe. It's developed for a warm climate, but it needs less adaptation than say, Gothic style, which is a northern European style of building. And you make the point that in your period, nobody thinks of looking at how Indians build their homes, you know, looking at the indigenous traditions for ideas, which you think would be the best place to look.

Rosie: A lot of it was trial and error.

Anonymous (Murshidabad School), Mr. Hampton's House, c. 1795-1803, Watercolour on paper, 36.8 X 69.1 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. What role did travelling artists like William Hodges, Charles D’Oyly and the Daniells play in informing viewers of their work about the architectural traditions of India? Did it serve to inspire builders/ architects to ‘revive’ certain forms or features from Indian structures, or create a taste in Indian architectural works?

Rosie: Yes, there was a certain excitement surrounding the drawings and paintings brought back by the Company artists. If you seek an extreme example, Brighton Pavilion might come to mind, although it leans more towards Chinese influence. However, places like Daylesford and another location in Gloucestershire, the Sezincote House, were notably influenced by Indian architecture. Surprisingly, there were also instances in Cheltenham, although these are almost unique examples. It's important to note that there wasn't a widespread adoption of the Indian style; rather, it manifested in just one or two examples.

Giles: And it's really a sort of exotic embellishment, isn't it?

Rosie: Oh yes, absolutely.

Sezincote House, Gloucestershire. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Q. What was unique about cantonment and hill-station architecture—and how did they spatially integrate militaristic buildings with civilian lifeworlds? Do these spaces simply reflect social hierarchies practiced during the colonial period or do they also help us see the ways in which such hierarchies were challenged, supported, or subverted in daily use?

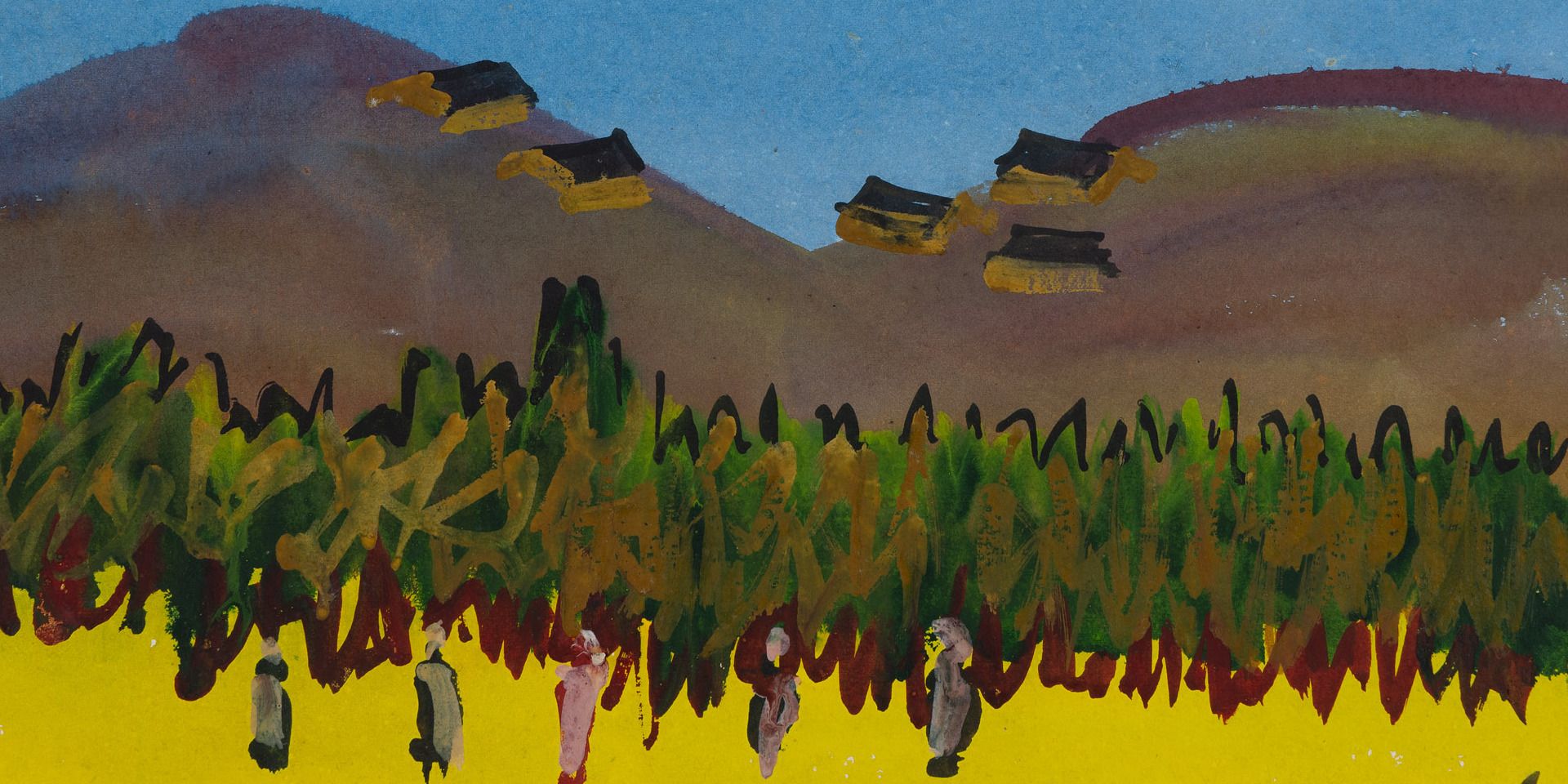

Rosie: Well if you're looking at a cantonment, obviously there is a hierarchy there. The officers reside in rather imposing houses, while the British soldiers inhabit less extravagant dwellings. On the other hand, the sepoys often find themselves constructing their own modest bungalows. For instance, in Kanpur, sepoys were known to build humble, thatched houses, and it's worth noting that the Urdu term for ‘cantonment’ translates to ‘thatched’. This signifies a departure from the traditional Mughal practice, where nobles were summoned during times of war to provide men and horses.

This shift marks a significant change, introducing, for the first time, a standing army in India—the East India Company armies. Consequently, there arises a need for designated spaces for various activities such as work, exercise, and practice. This gives rise to an entirely new structure, featuring parade grounds, powder magazines, and an armoury for weapon storage. The transformation is profound and represents a departure from the established Mughal patterns of warfare.

Anonymous (Murshidabad School), Berhampore Cantonment, c. 1795-1803, Watercolour on paper, 43.2 X 74.9 cm. Collection: DAG

Giles: Yes, it’s very much a new type: the cantonment. And I think part of the answer to the question is the extent to which these places have survived. Despite significant losses, as seen in places like Maidapur where little remains on the ground, there are cities where the civil lines or cantonment areas endure. Examples include Benares and Agra. In Delhi, for instance, we can see how its planning amalgamated different elements and traditions, with one notable influence being the cantonment. When moving around the central streets of the Lutyens' bungalow zone, which is essentially a military cantonment, the essence of this legacy remains very much visible.

Rosie: Yes, Berhampur was entirely developed around the cantonment area, with a very large parade ground and splendid rows of officers' houses. I'd say that's probably one of the best examples.

Q. While towns and cities like Murshidabad, Berhampore and Maidapore were subjected to lavish colonial building, they quickly faded away as political power (and natural amenities, like a branch of the Ganges River) moved away. Did they leave any traces of their presence in local architectural styles subsequently?

Rosie: If you look at the old British cemeteries you can get a glimpse into the historical presence of the British and they also underscore the high mortality rates. I would say that the presence of these burial grounds serves as a visible symbol of something which was there before, even if the cantonments themselves have disappeared.

Giles: The materials used in constructing many of these structures, especially in domestic architecture, somewhat hinder their long-term preservation don’t they? Unlike Mughal architecture, characterized by robust stone construction, the brick and stucco palaces of Bengal, for example, face challenges in enduring the harsh Indian climate. This aspect contributes to their relatively shorter lifespan as well.

Rosie: The preservation of these structures does depend on the care they receive, but I acknowledge your point. Bengal faces a scarcity of stone until you reach Chunar, where high-quality sandstone becomes available. Those with financial means can afford to import it for their constructions, as could be seen in some buildings in Calcutta. However, as it has been pointed out, the predominant materials are brick and stucco. Notably, brick alone can endure surprisingly well. In places like Gaur, the ancient capital of Bengal, modern houses often have foundations made of these durable old bricks, identifiable by the material used, which is usually lakhori (thin bricks that were used when stone was not available). Proper maintenance plays a crucial role. Examining the foundations of buildings reveals the use of old bricks, frequently sourced from other sites. Unfortunately, I have witnessed instances of people robbing bricks from protected monuments.

Anonymous (Murshidabad School), Mr. Fendall's House, formerly Mr. Parlby's House, c. 1795-1803, Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 38.6 X 54.6 cm. Collection: DAG

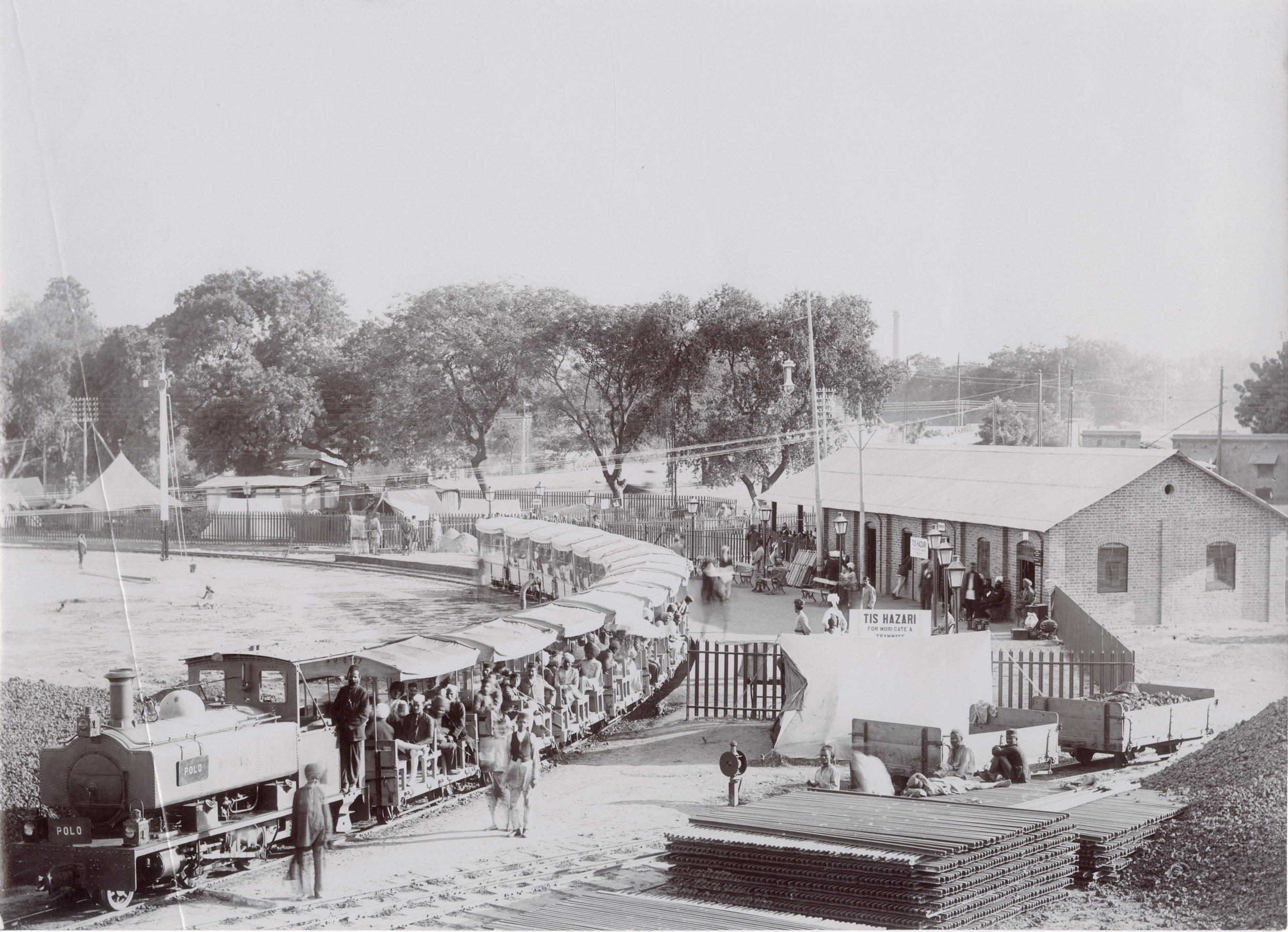

Q. You write that the railways were initially built to transport materials like coal up to steamboats, and that the authorities were surprised by its increasing popularity with Indians, leading to the enterprise becoming profitable soon. How did the colonial government seek to encourage train travellers after that? What were the enticements offered? And how do you compare this enthusiastic response with—as you point out—the general lack of response from Indians to early colonial building projects?

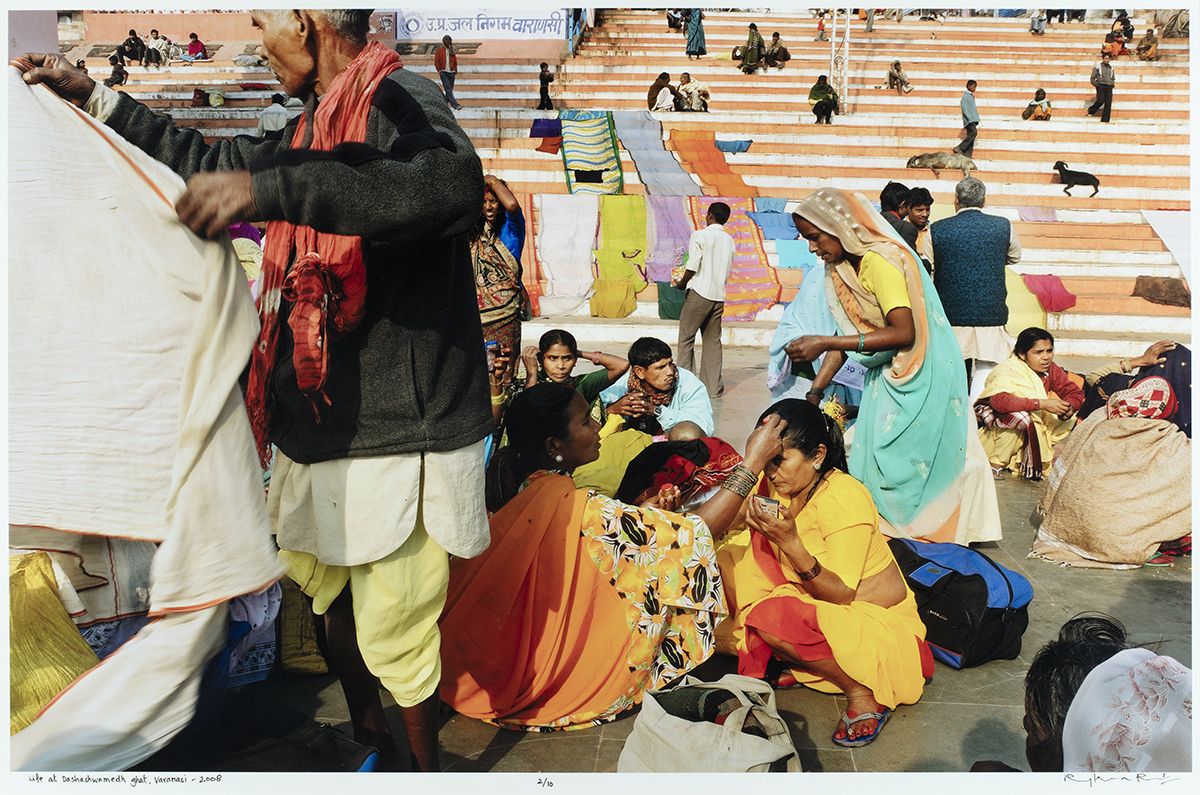

Rosie: Well, I don't, I don't think the company needed to encourage Indians to travel on railways. If you look at the statistics, it's absolutely amazing how quickly it became so popular. And initially, the idea was that the railways would transport freight and a few passengers, but it didn't work like that. Very little freight was taken on the railways. One of the reasons they were so popular was that fares were very, very cheap. It was something like a mile for half an anna, perhaps. And as I write, I think the main reason for the popularity was that people wanted to visit holy places, temples and mosques, which had previously been impossible because of distances. So it was really transporting people and not freight. And I think you've got to allow for curiosity. That's something we don't often talk about, but the simple curiosity of someone wanting to be on a train, the excitement of moving quicker than you've ever been able to do before and going to see something you've always wanted to see but have never been able to.

|

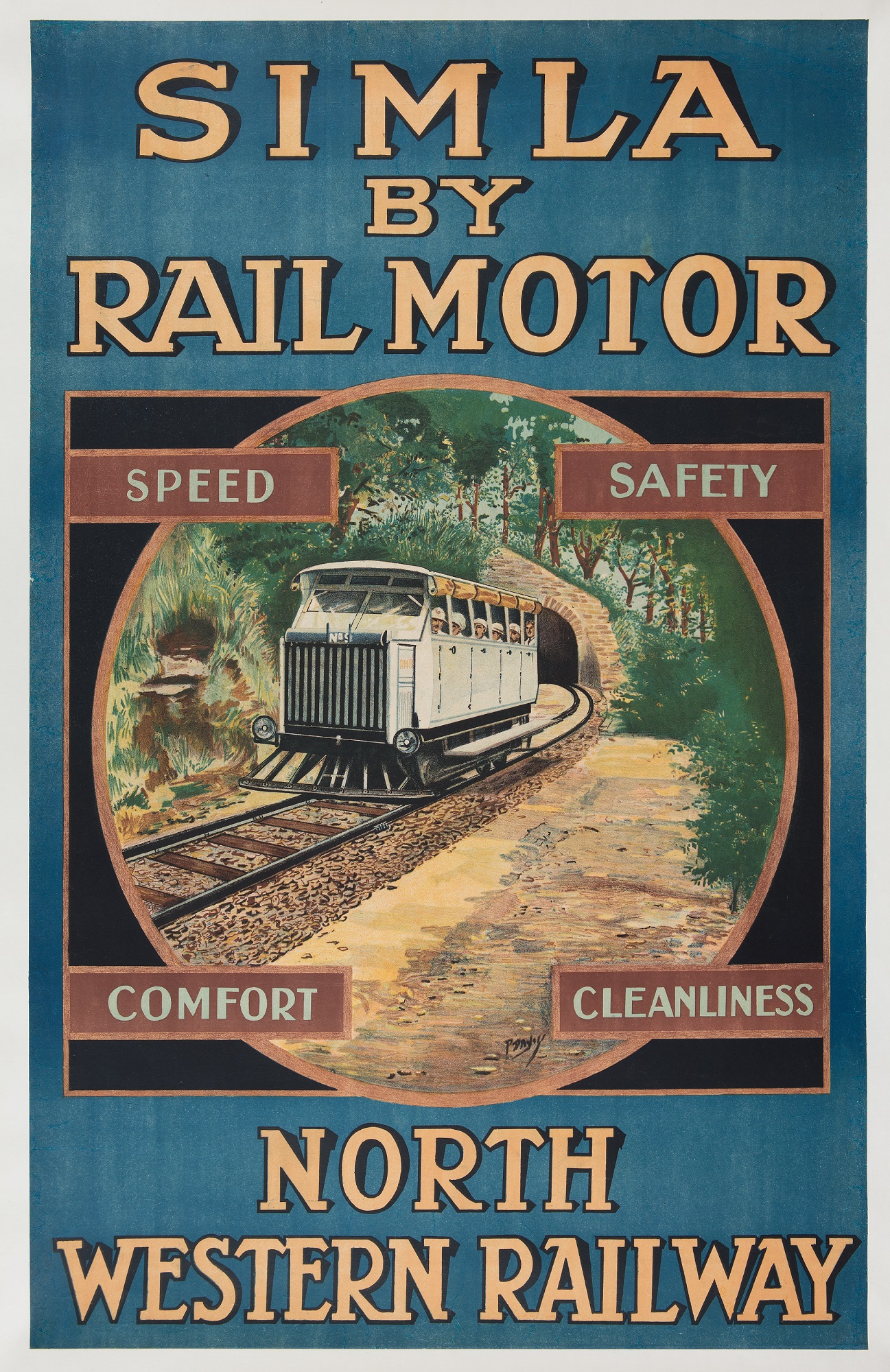

Unidentified artist, Simla by Rail Motor, c. 1930, Chromolithograph on paper. Collection: DAG |

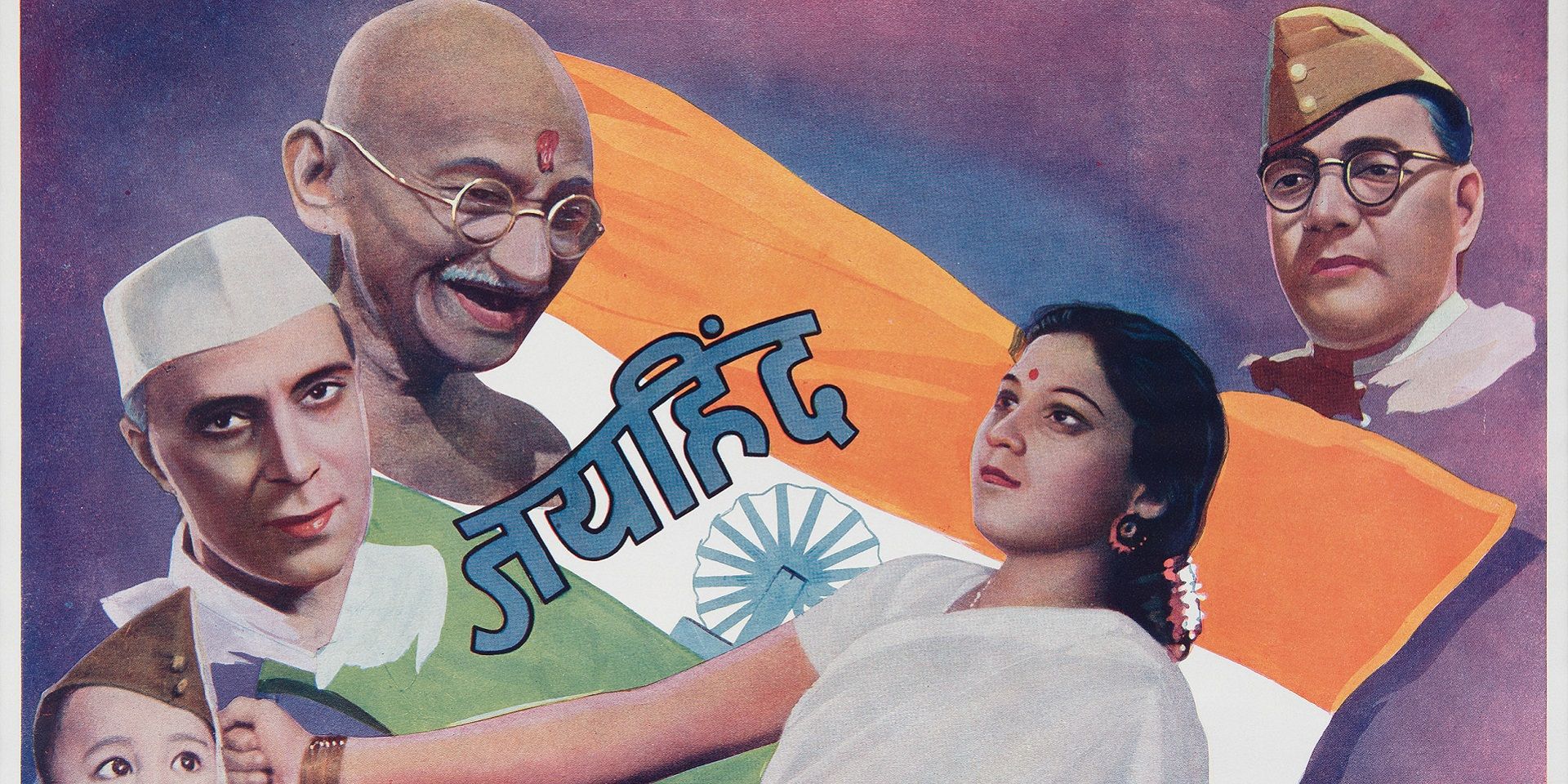

Giles: The question arose in connection with another exhibition held last year, the March to Freedom exhibition. While the travel posters featured in that exhibition belong to a later period than the one discussed in your book, they also depicted places of pilgrimage as destinations. The development of the railways played a crucial role in this, making Indian people more mobile and contributing significantly to their understanding of the nation. In essence, the railways played a pivotal role in nation-building. Before the railways, people typically remained in one place throughout their lives and didn't venture far. The ability to travel and witness different parts of India facilitated the development of a collective sense of the nation. Surprisingly, there hasn't been extensive research into the mindset shift brought about by the railways, despite its evident importance.

Rosie: Yes, I think you wouldn't actually find that until after 1860 because they had been very slow in developing the railways and they blamed themselves afterwards, because they couldn't move troops around more quickly during the uprising (of 1857). Yes, I think to some extent you're probably correct and I'd say this developed during the second half of the nineteenth century.

If we look at one of the first railways in Bengal, that was simply going up to Raniganj where coal had been discovered, bringing it back down to Kolkata for the steamships. I mean this isn't to say that people didn't go on pilgrimages before the railways, we know that they did. I have looked at some of the maps made by Joseph Tiefenthaler, the Jesuit priest, and he's clearly incorporating maps of pilgrim routes going up to Rishikesh. So, you know, there were pilgrimages, obviously, before the railways. You could say the railways accelerated them, if you like, but they certainly weren't planned to go to temples or mosques or anything like that. The British wouldn't have thought of that. The railways probably made it less of an undertaking for an individual. If you look at their papers or pilgrim maps from an earlier pre-railway period, you would see how it was a major undertaking to go into the Himalayas.

Unidentified photographer, Durbar Railway (Narrow gauge at Tis Hazari Station), 1911, Silver gelatin print on paper, 20.8 x 29.2 cm. Collection: DAG

Q. One of the central chapters in your book is titled ‘The Spirit of Enlightenment’; could you tell us how the world of ideas were influencing these projects, expeditions and the general approach to developing knowledge systems in colonia India?

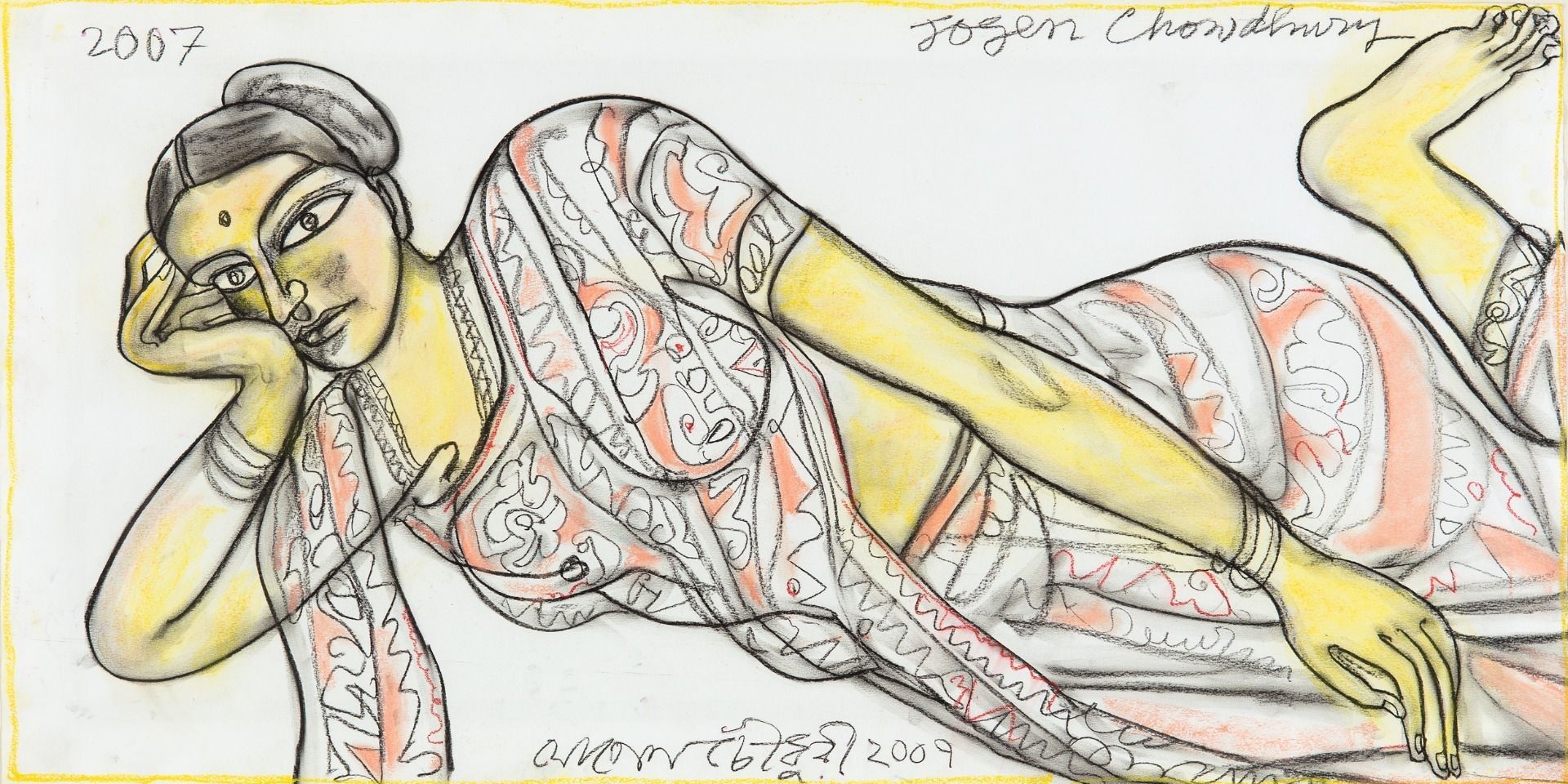

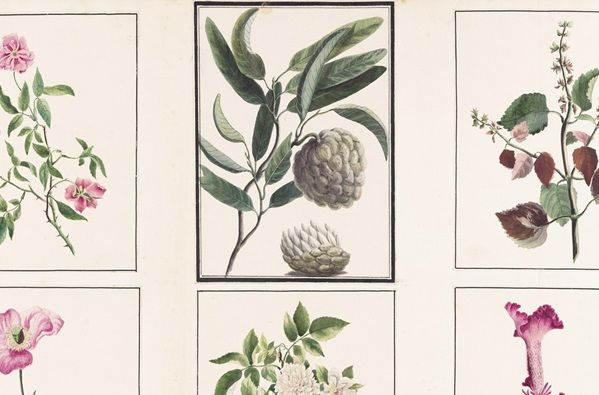

Rosie: My aim was to show the diverse roles that engineers played in the late eighteenth century. If we use botany as an example, we can consider a figure like Robert Kyd, a Bengal engineer, who founded the Botanical Garden in Calcutta (in 1787), showcasing the extensive involvement of engineers in fields beyond the traditional perception of military personnel constructing bridges. The term ‘engineer’ is often narrowly associated with certain activities, but I wanted to convey the breadth of their contributions, which included cartography, astronomy, mineralogy, and botanical explorations. Even individuals like Thomas Hardwick, initially labelled as an engineer without a formal title, contributed significantly. He was recruited into the Bengal Engineers and undertook remarkable explorations, bringing back a wealth of discoveries. In essence, I wanted to demonstrate the wide-ranging nature of the term ‘engineer’ at that time and the diverse fields it encompassed.

Giles: I think you've accomplished that very splendidly. And along the way, you tell the stories of individuals, some of whom are familiar, like William Jones, where we learn more about them, and some of them are less familiar. And the information that you've brought together about them and their careers, I think makes for a tremendously engaging read.

William Hodges, A View of Chinsura,the Dutch settlement of Bengal, Handtinted engraving on paper. Collection: DAG

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

The Editorial Team

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025