Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Dr. Guha-Thakurta II

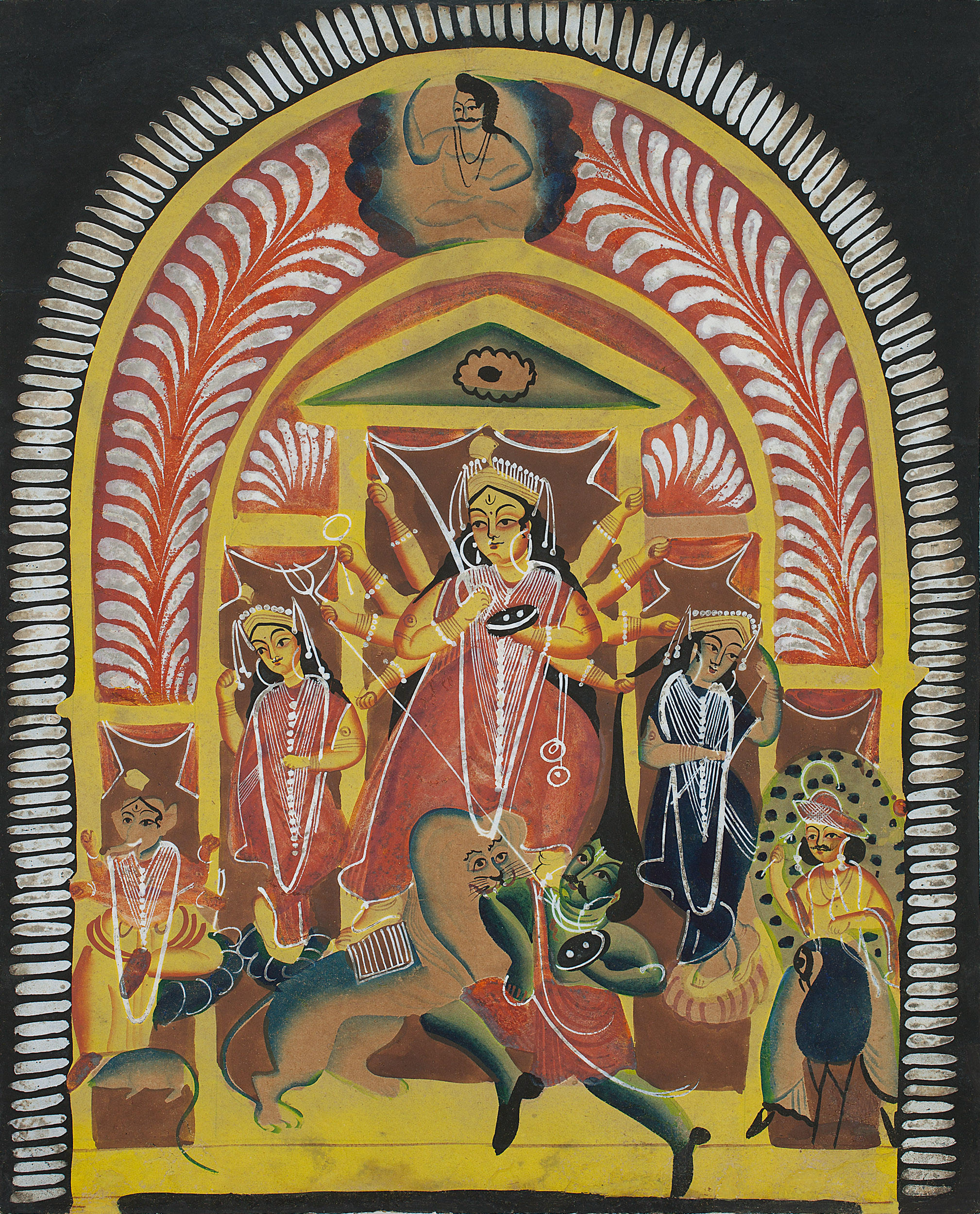

Anonymous (Kalighat pat), Untitled (Durga Puja) (detail), Watercolour and gouache on paper pasted on cardboard. Collection: DAG

Read the second part of our conversation with the scholar Tapati Guha-Thakurta, where she takes us through the general thematics explored by the book How Secular is Art?, finishing with her views on the curious place of the folk in the secular imagination, and the changing fate of goddesses in Indian art.

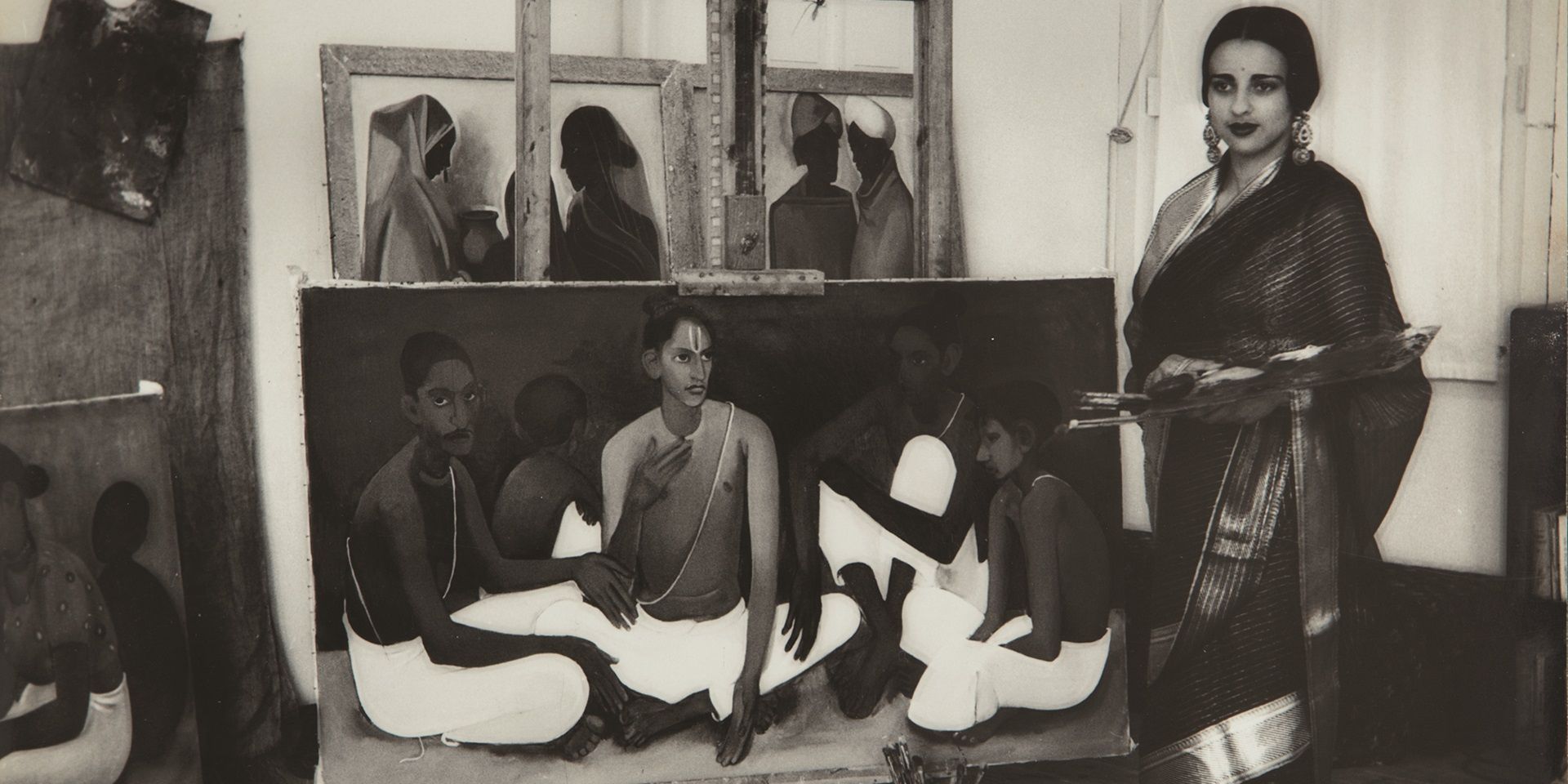

As Dr. Guha-Thakurta reminds us, this volume of essays, co-edited by her, entirely features the work of women scholars in the fields of art history and visual culture. Even though this was largely serendipitous, it underlined the need for solidarity among scholars at a time of unprecedented shocks provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the scholars lost family members at the time, and, as she put it to us, ‘when we talk about (the) secular as a ground of solidarity, we felt that as women scholars in a field where men still dominate, it was also our act of solidarity in coming together to produce this book’. With the recent passing of another scholar who contributed to this volume, Dr. Kavita Singh, this political need gains even more relevance at this moment in time—and acts as a way to memorialize her contribution to the world of art history at large.

To read the first part of the interview,

click here.

Pushpamala N. during Khoj Live, 2012. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Q. The (thirteen) essays in the volume are divided into four thematically distinct parts—would you like to elaborate on these themes for us?

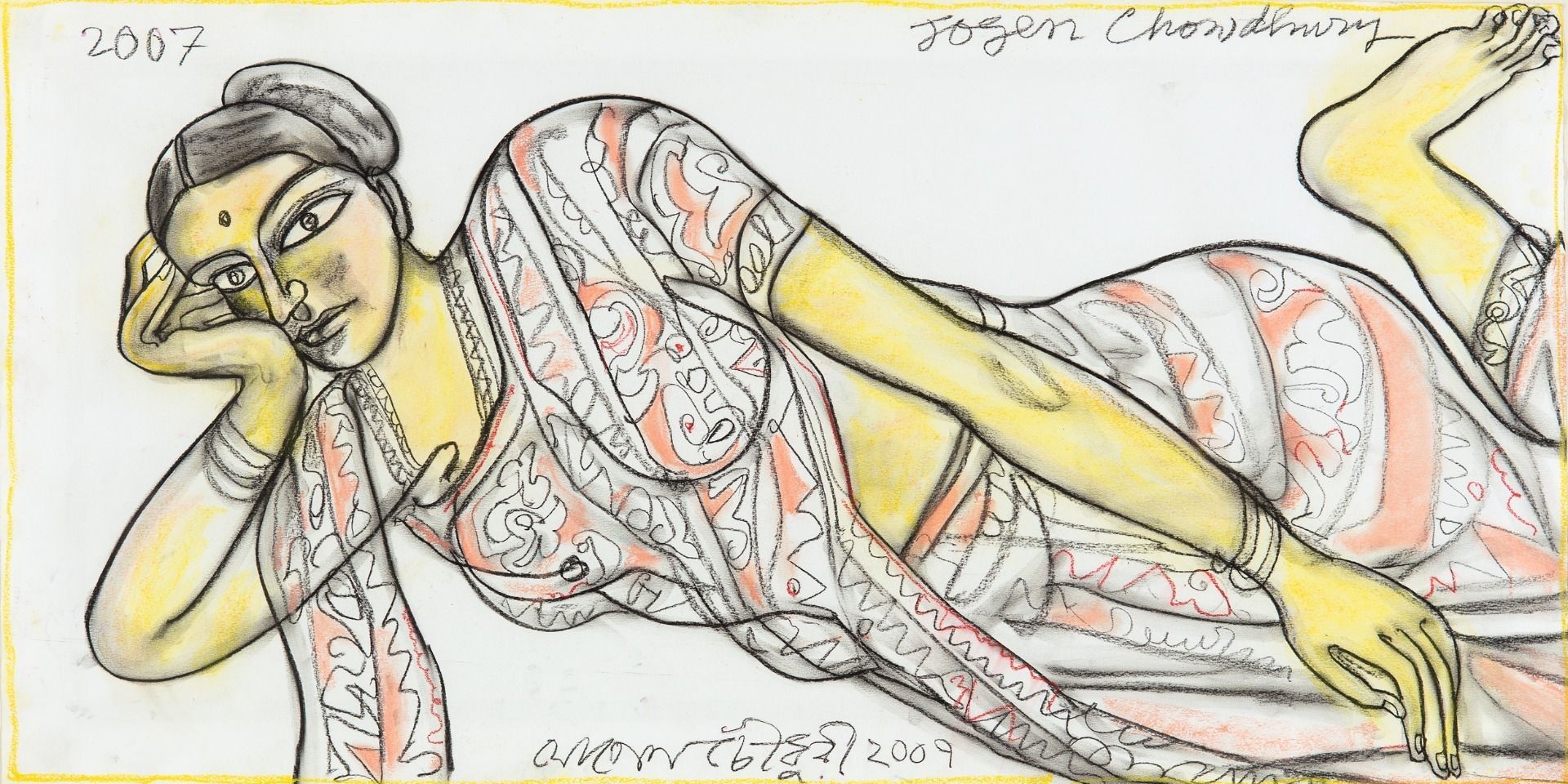

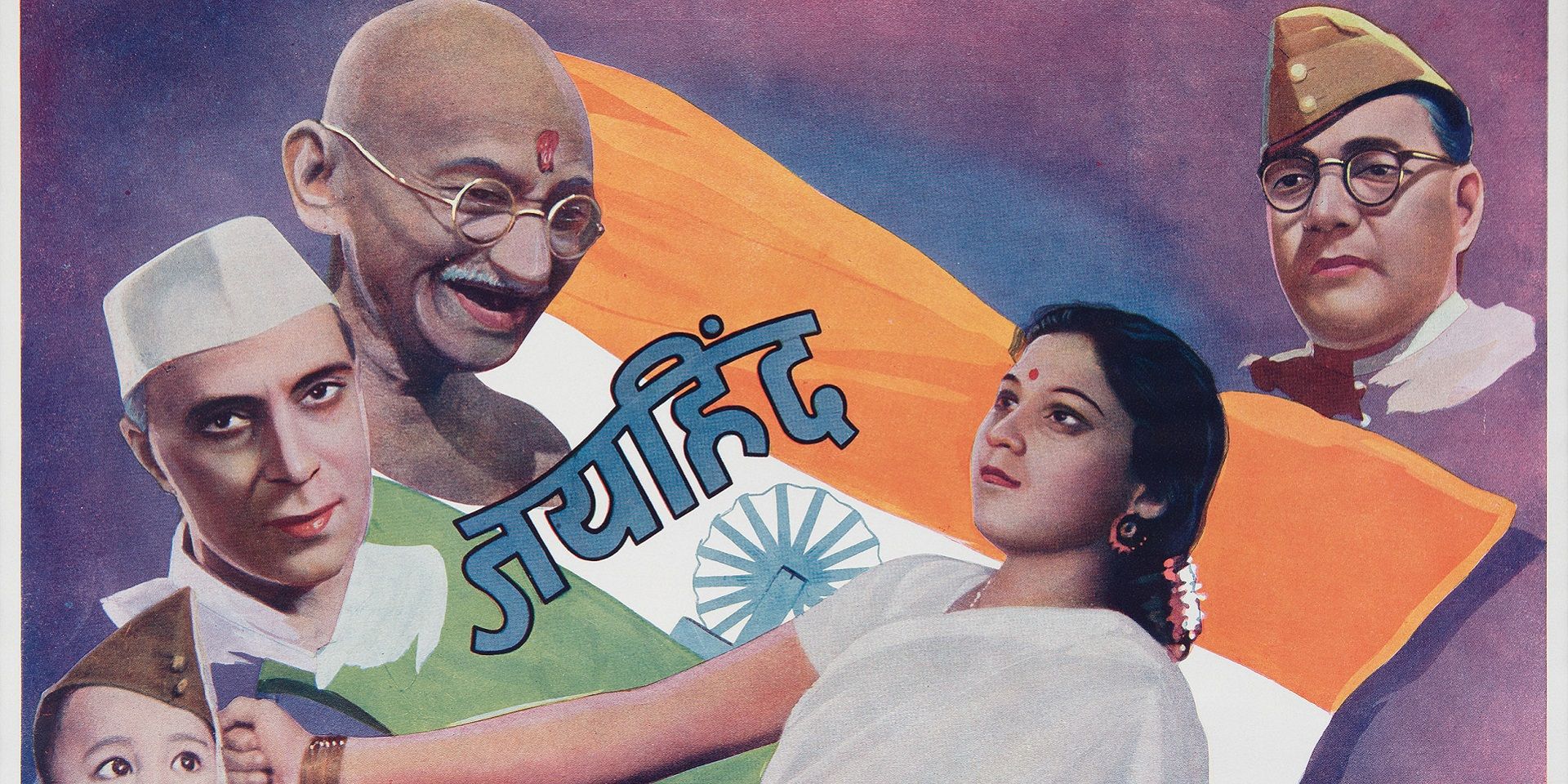

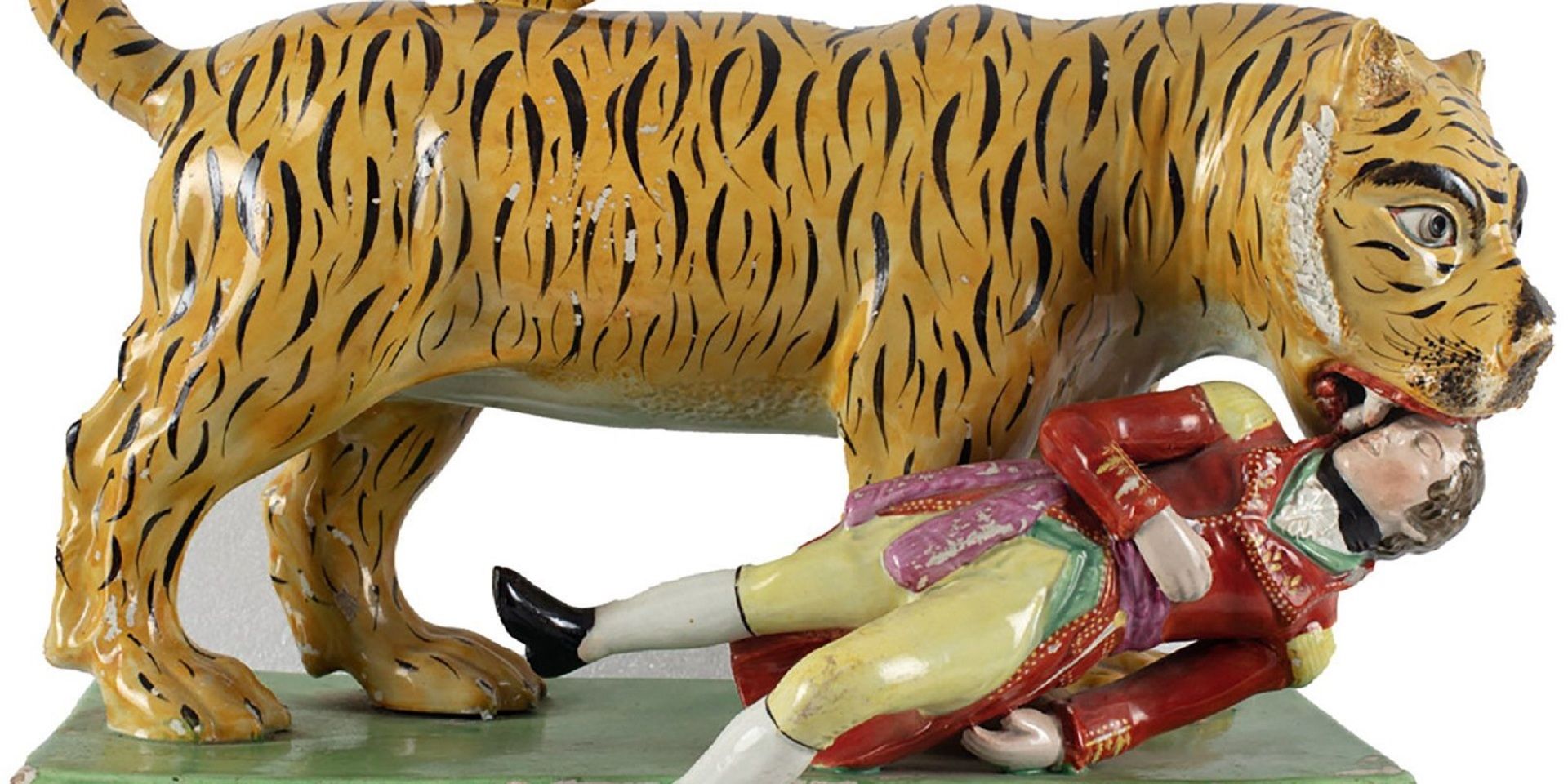

Tapati Guha-Thakurta: I had intended to put Kajri Jain’s essay in a later section but ended up including it within the first thematic bloc of the book, ‘Secularity and its Art’, which also contains two other essays by Akeel Bilgrami and Karin Zitzewitz. In Bilgarmi’s essay, he is looking at the political and cultural mandate of the secular, and what this has meant for a Muslim writer or artist when s/he enters the public discourse as Muslim, and not just as a secular citizen, which is of course not to suggest that in becoming a secular citizen s/he ceases to be Muslim. Zitzewitz’s essay offers an important instance of someone who continues to hold the flag for thinking that certain basic professional solidarities of practice still remain that can define the ambit of a secular practice, if not secularism generally. In Jain’s essay, she asks what happens when one chooses objects that have no place in art history proper but that artists may appropriate for their work. An artist like Pushpamala N. may dress herself to fit into the frame of a popular religious poster, but how does a secular art historian read that act of appropriation or insinuation while staying within her own disciplinary boundaries? These are some of the issues raised in the first section.

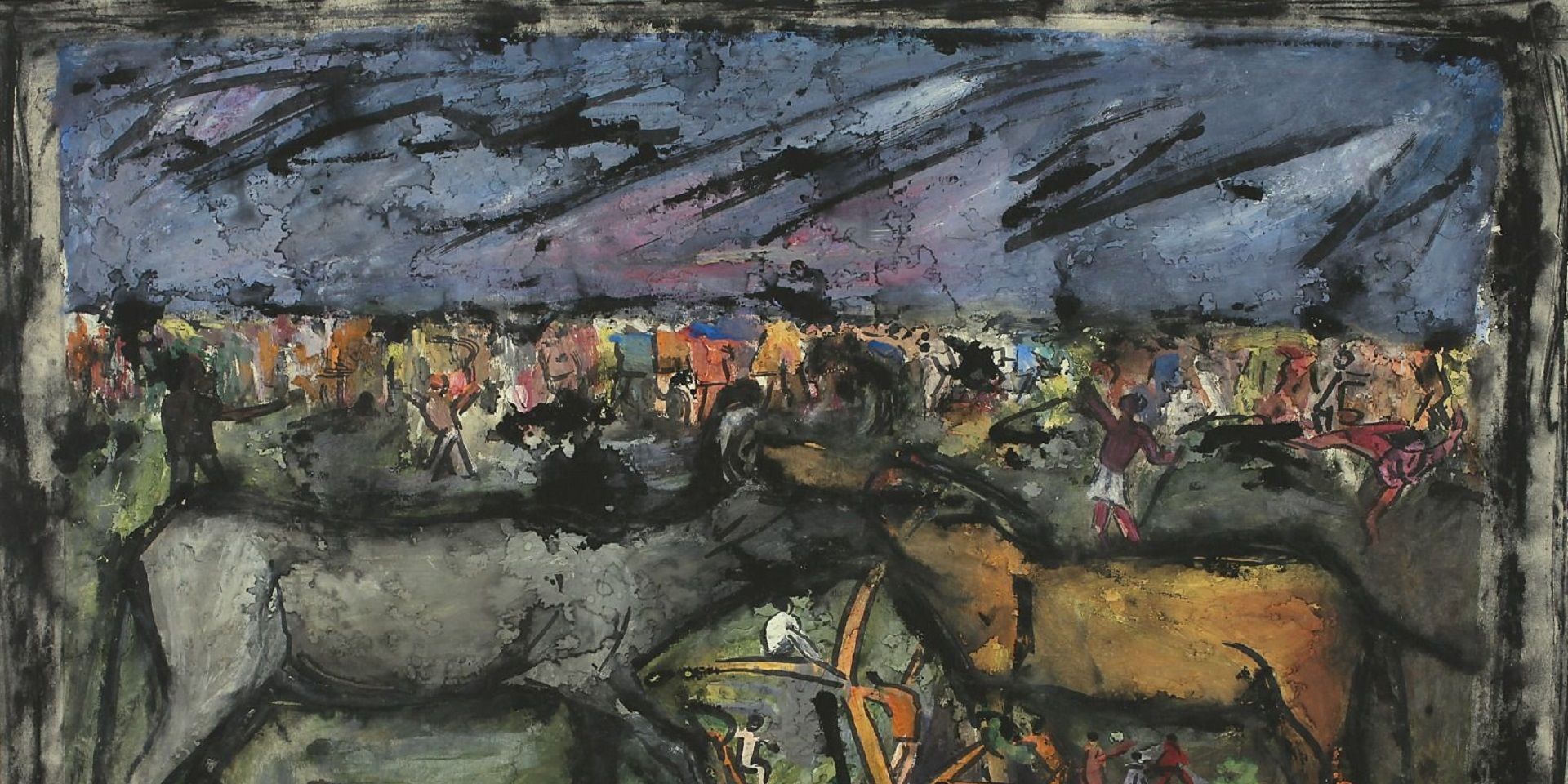

The second section, titled ‘Boundaries of Secular Nationalism’, includes essays by Vazira Zamindar (focusing on the Pakistani artist Sadequain), Sanjukta Sunderason (focusing on the Pakistani, and then Bangaldeshi, artist Zainul Abedin’s career working for the state of East Pakistan), and Zehra Jumabhoy, and looks at the problem of being a modern artist across boundaries and partitions and what the subsequent cementing of nationalities does to the idea of the secular nation state. We invited Holly Shaffer and Sanjukta Sunderason to write separate essays for the volume—but they weren’t a part of the original conference. Vazira and I wrote our papers after the conference too, since we were busy organizing it at the time. We wanted to include more essays from outside India, especially from Pakistan and Sri Lanka, but that did not work out eventually.

|

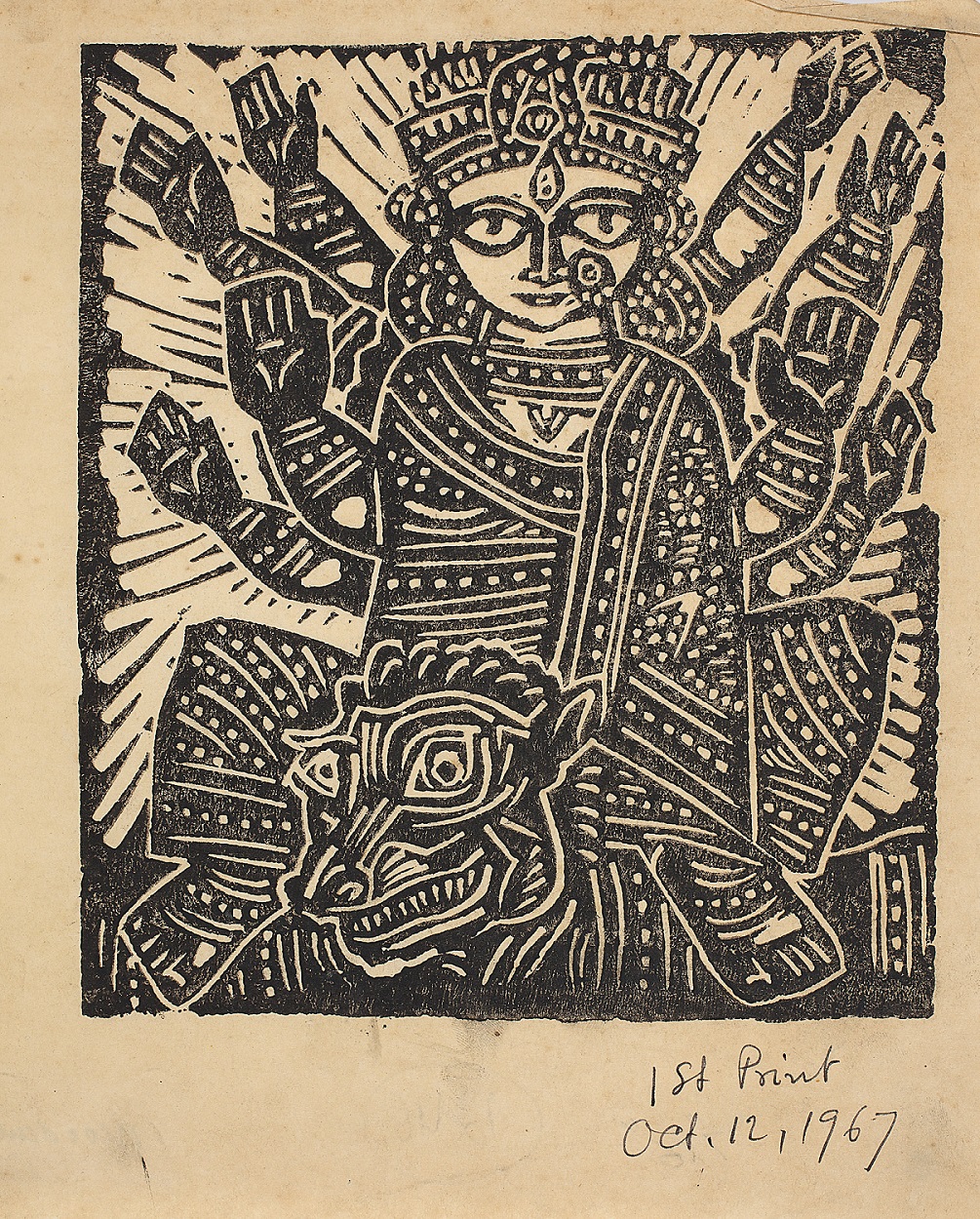

Chittaprosad, Untitled, Linocut on paper. Collection: DAG |

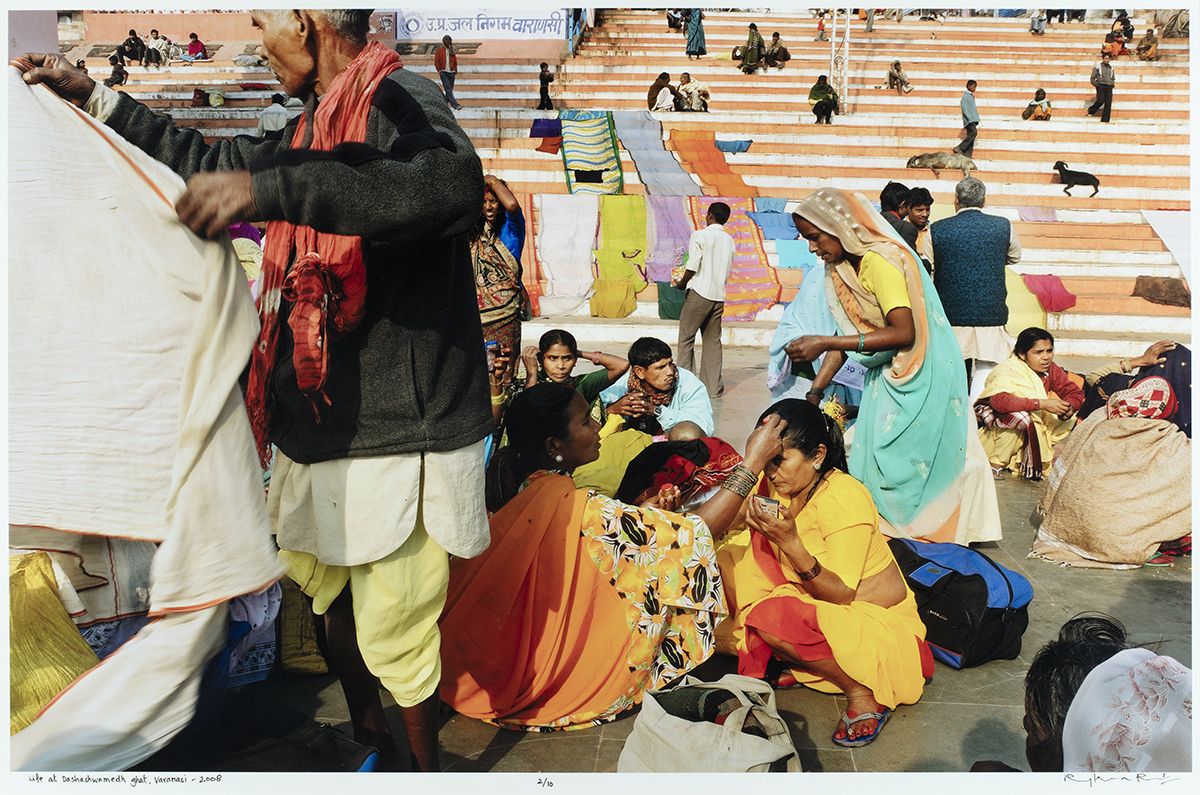

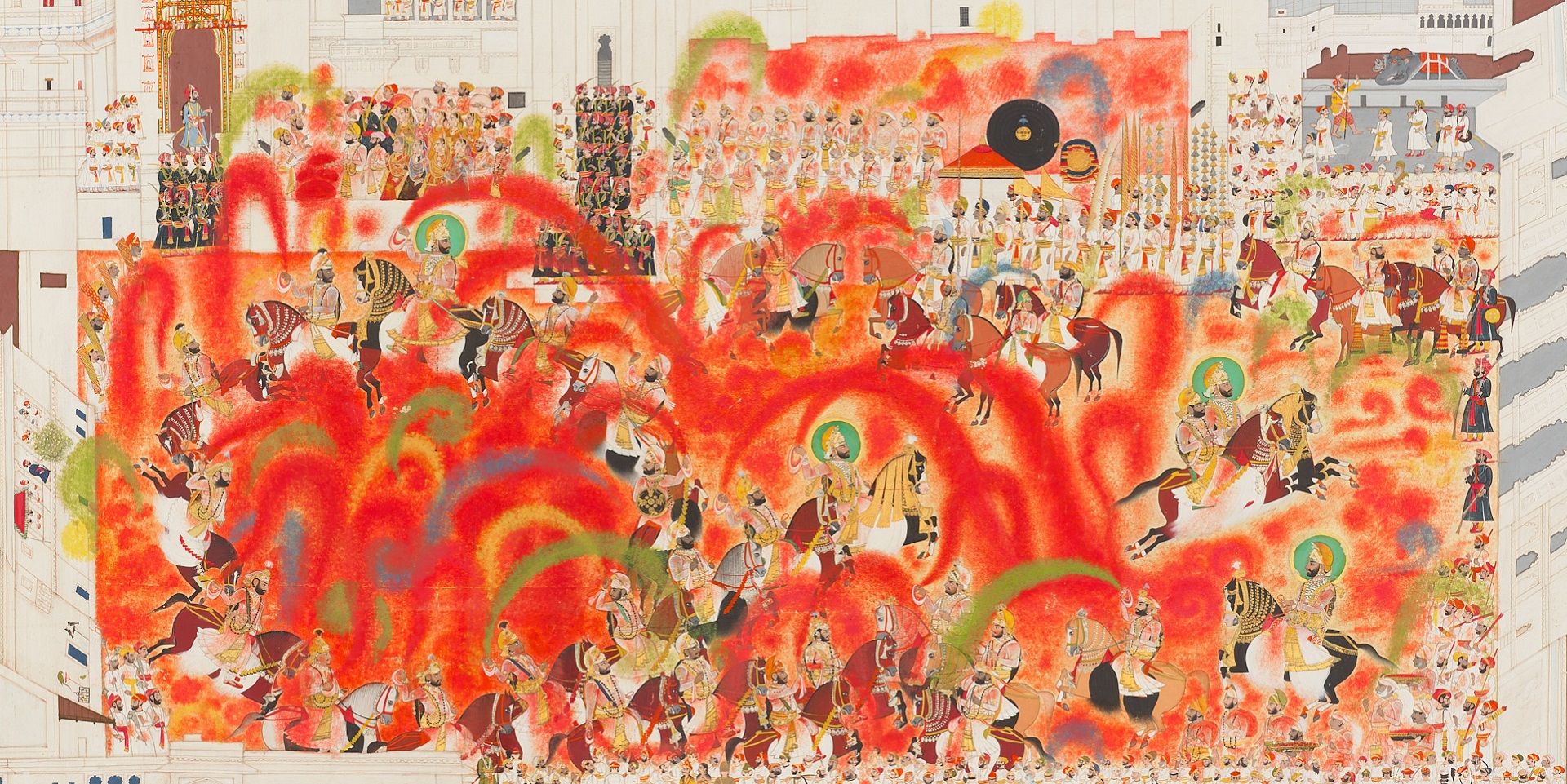

The third section, titled ‘Art and its Gods’, focuses on iconographies. Shaffer’s essay grapples with the ideas informing visual representations of Shivaji in Marathi art and culture. Even when his image becomes a political icon, it is also seen as an object of intense devotion. I wrote my essay, ‘Can a Festival of a Goddess Be ‘Secular’?’, as a postscript to my book (In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata) because I did not really address the influence of political parties on the festival. In the essay I look at this segment, and at the terms by which the present government has turned Durga Puja into Kolkata’s biggest event while capitalising on the Hindutva brigade’s non-comprehension of the avowedly secular cultural essence of this festival. I contrast this aspect of the festival with its artistic conception and production. My case studies were from 2019, when the citizenship debates spilled right onto the conceptualization of theme pujas.

|

Goddess Durga depicted as a migrant mother at a Durga Puja pandal in Kolkata's Barisha neighbourhood, 2020. Image courtesy: Wikimedia commons |

Sumathi Ramaswamy, in her essay ‘A Historian among the Goddesses of Modern India’, explores how she—as a historian—enters the world of goddesses, both older ones, like Tamilttay (literally, ‘Tamil mother’), and more contemporary ones like Angrezi Devi/Dalit Ma, the pandemic goddess, etc. The coronasura (where the demon, in the guise of the virus, is vanquished by Durga) also featured in the Durga Puja pandals during the pandemic.

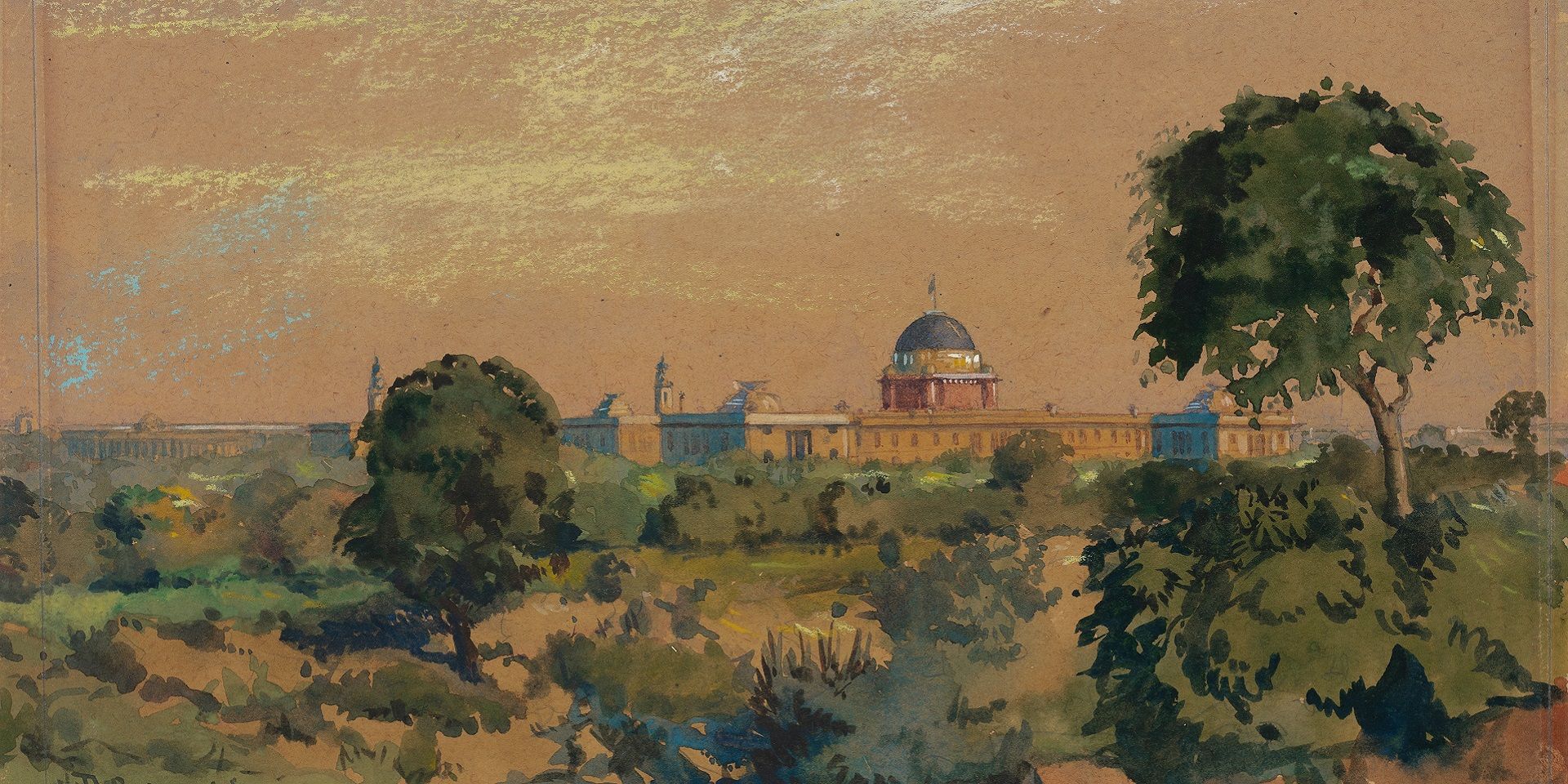

And the last section, titled ‘Architectures of Devotion’, is looking at architecture and the re-sacralization of architecture. In the first essay, ‘Re-enchanting Mughal Architecture: A Critique of the Secular Disenchantment of India’s Past’ the author, Santhi Kavuri-Bauer, argues for a re-enchantment of the Taj Mahal—as both, an Islamic monument as well as a wondrous object in itself. She feels that a lot of the academic work on the monument has emptied the Taj of its potential to enchant viewers. However, it is also interesting that it is precisely because the Taj is such an auratic object, that ultimately it has survived—and may still survive—the various political claims to become a world heritage monument.

Randolph Bezzant Holmes, Taj from the River, Toned silver gelatin print on paper, 9.4 x 11.2 in., c. early 20th century. Collection: DAG

I was recently in Istanbul, and there the wonderful Hagia Sophia museum has been turned once again into a mosque, thus becoming a place of worship. There has been a lot of criticism against this move in Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, but people who were decrying this change were disregarding the fact that for most of its life it was a mosque right from the fifteenth century into the twentieth. In some ways this bringing back of religion also raises questions about the steady vigor of Islamification and what Kemal Attaturk’s secularist project meant for Turkey in the past and its consequences today.

The last two essays—by Tamara Sears and Kavita Singh—are about the recreation of temples in contemporary times. The essay by Kavita Singh, titled ‘For the Love of God: Conservation as Devotion in Tamil Nadu’, is particularly interesting because in addressing the work of the REACH foundation in Tamil Nadu it talks about conservation as devotion. Here we have the scientific process of conservation—using the professional language of restoration as well—followed by a wish to return to religion. These essays confront questions about temple revival and reclamation, exploring, for instance, how Konark was used as a model for building a new Birla temple at Gwalior. Kavita’s essay has no pictures because the REACH foundation refused to let her use a single image from their website because of her institutional affiliation (Jawaharlal Nehru University). There has been a lot of debate recently on the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HRCE) Trust, and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI); with the critique being advanced against ASI that a lot of the temples which are managed by the religious trust have not been given the right kind of restoration and treatment they need.

Interior view of the Hagia Sophia Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, formerly a museum. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Q. The art historian James Elkins contends in a book that religion, when it does enter the world of a modern artwork, does so inevitably in the language of mockery or as ‘kitschy’/ middle-brow references. In South Asia how do we look at the legacy of modern artists who did adopt religious idioms in their work prominently—like G. R. Santosh?

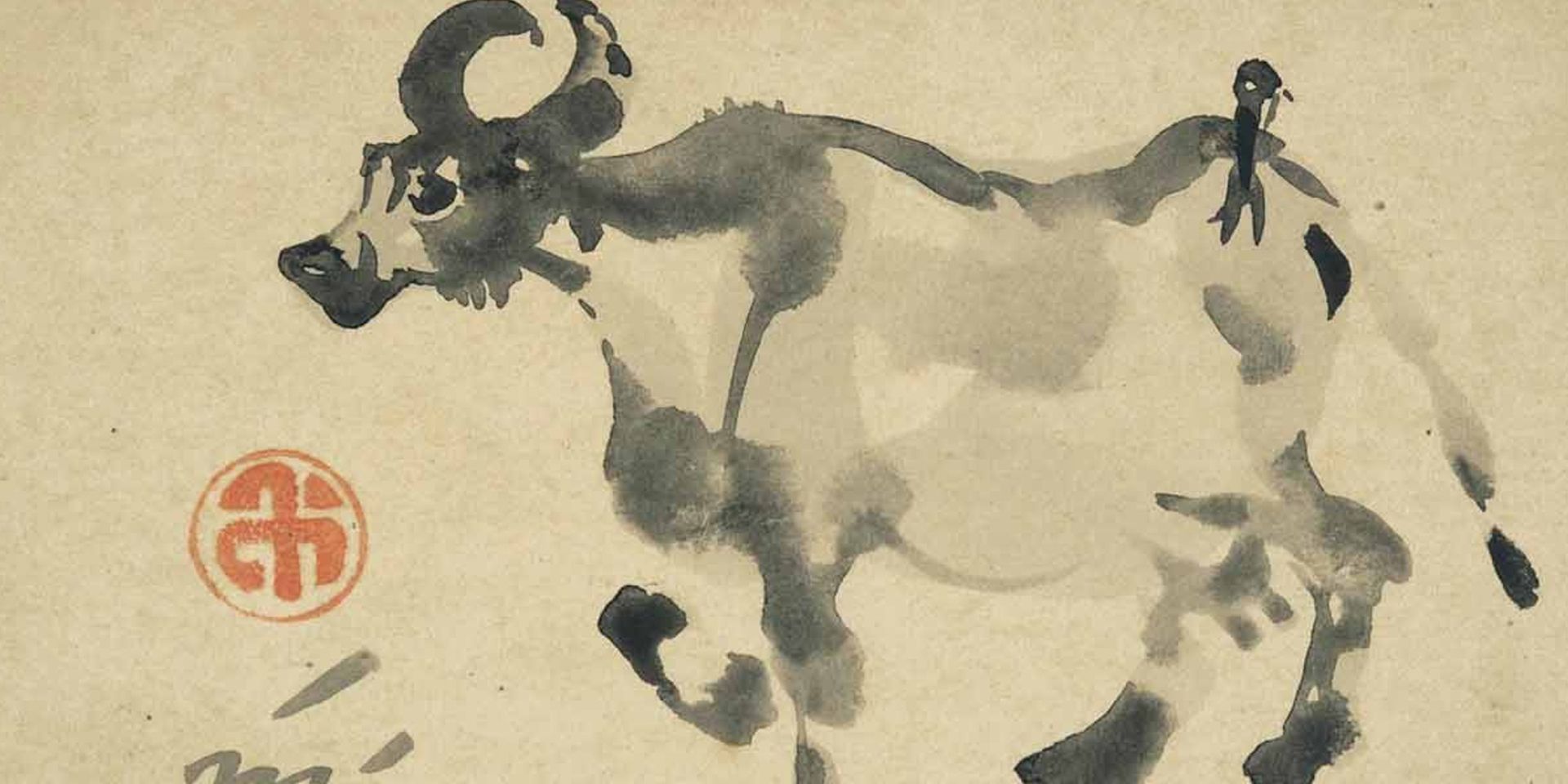

Dr. Guha-Thakurta: Madhu Khanna did a book on Tantra art for DAG, which probed the deeper motivations of this form of art-making (undertaken by G. R. Santosh, among others), asking what tantra meant in the decade of the 90s when the world was discovering Indian spirituality. Was it just a decorative art? I think the interesting question will be to ask how we can place the modern artist as both a secular citizen and as a carrier of belief and faith. And not necessarily within the parameters of religiosity we recognise today. That is a more difficult question that Elkins is asking. And Elkins, like Kajri Jain, is trying to say that there are other artists who do use these idioms differently. Many of them who do this also come from a background in fine arts training and practice, so that they can play around with different styles and have a very clear sense of what works for the market. So, the market becomes an important agent in these discussions as well and no artist works without a sense of how this market operates. Consider an artist like Jamini Roy, for instance, and the use of religious imagery in his work; he was a committed, Leftist intellectual but made a lot of religious images that complicates his left-secular-modern orientation.

|

G. R. Santosh, Untitled, Acrylic on canvas, 50.0 x 40.0 in., 1978. Collection: DAG |

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Tempera on board. Collection: DAG

The fact that he's also popular, that he makes copies of his own work and converts himself into a future industry does not take away from these basic commitments (for him). In some ways, however, he does fall out of the Indian art historical canon, except for some select circles of criticism. R. Siva Kumar, for instance, has no place for Roy in his modernist art histories and neither does Geeta Kapur. Jamini Roy is an interesting artist who poses this challenge to a modernist canon, largely because he brings so much of religion into his work.

Q. Zainul Abedin has been criticized by some artists in Bangladesh for drawing upon a social realist academic style for his famous famine sketches and not upon the global language of abstraction that he was expected to mature into and he doubles down on this social realist style. And is he also replenishes it with folk references and influences. How do you see this career of the ‘folk’ unfolding in modern art, vis-à-vis the idea of the secular; do you think it expands the secular, or is there a risk of it becoming another route through which ‘soft’ religiosity can enter?

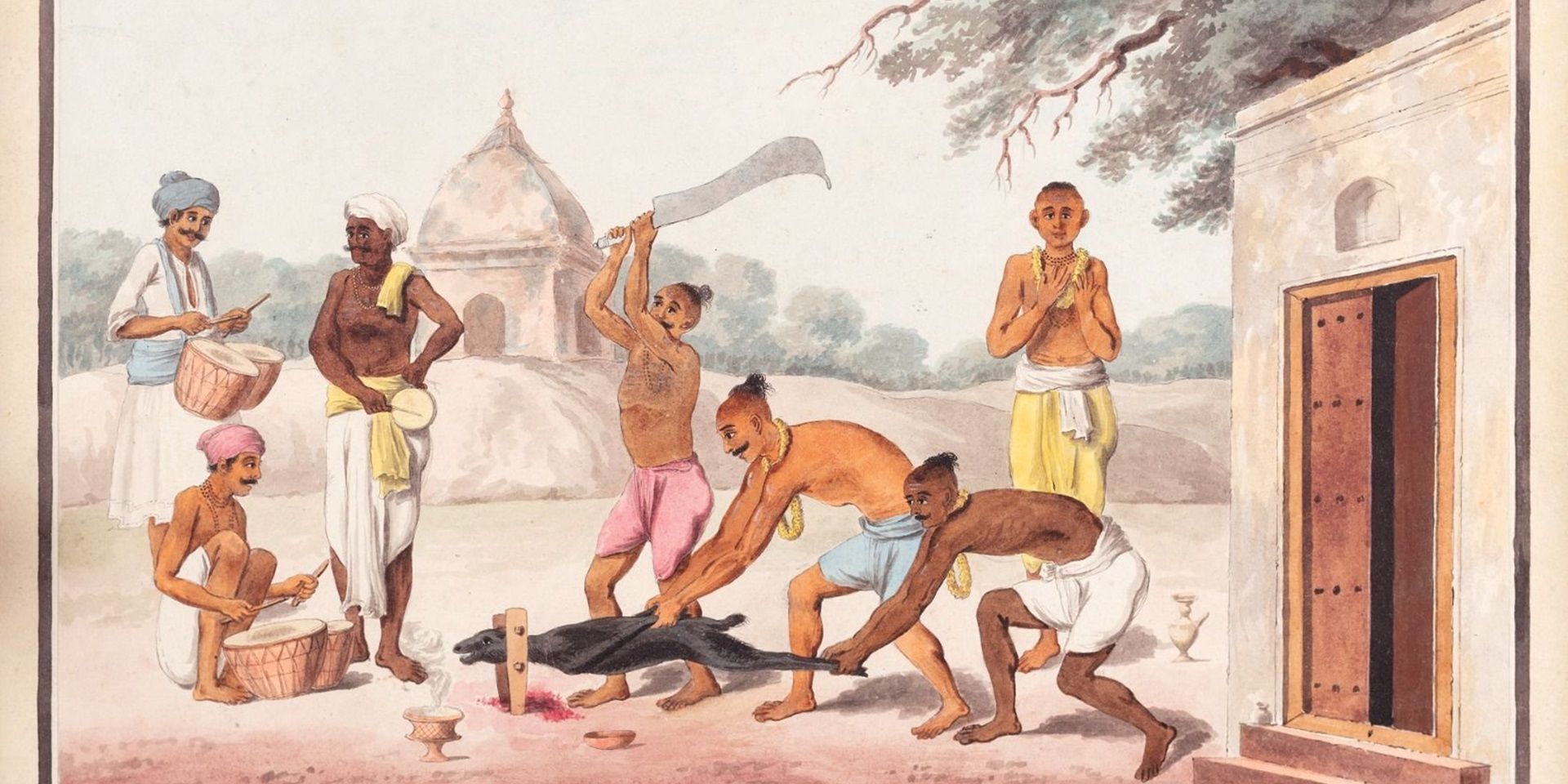

Dr. Guha-Thakurta: The folk can be appropriated because the folk artist is not ‘secular’; folk inhabits its own world of belief and rituals, etc. From Gurusaday Dutta onwards to the work of Meera Mukherjee and Jamini Roy, the folk aims to signify that romantic notion of a pure organic world based on belief, customs and rituals. Folk does not stand in just for religion, but much more, because it falls outside the fold of Brahminical institutions and other official forms of religion. Zainul Abedin’s move is to reclaim a distinct identity for East Pakistan.

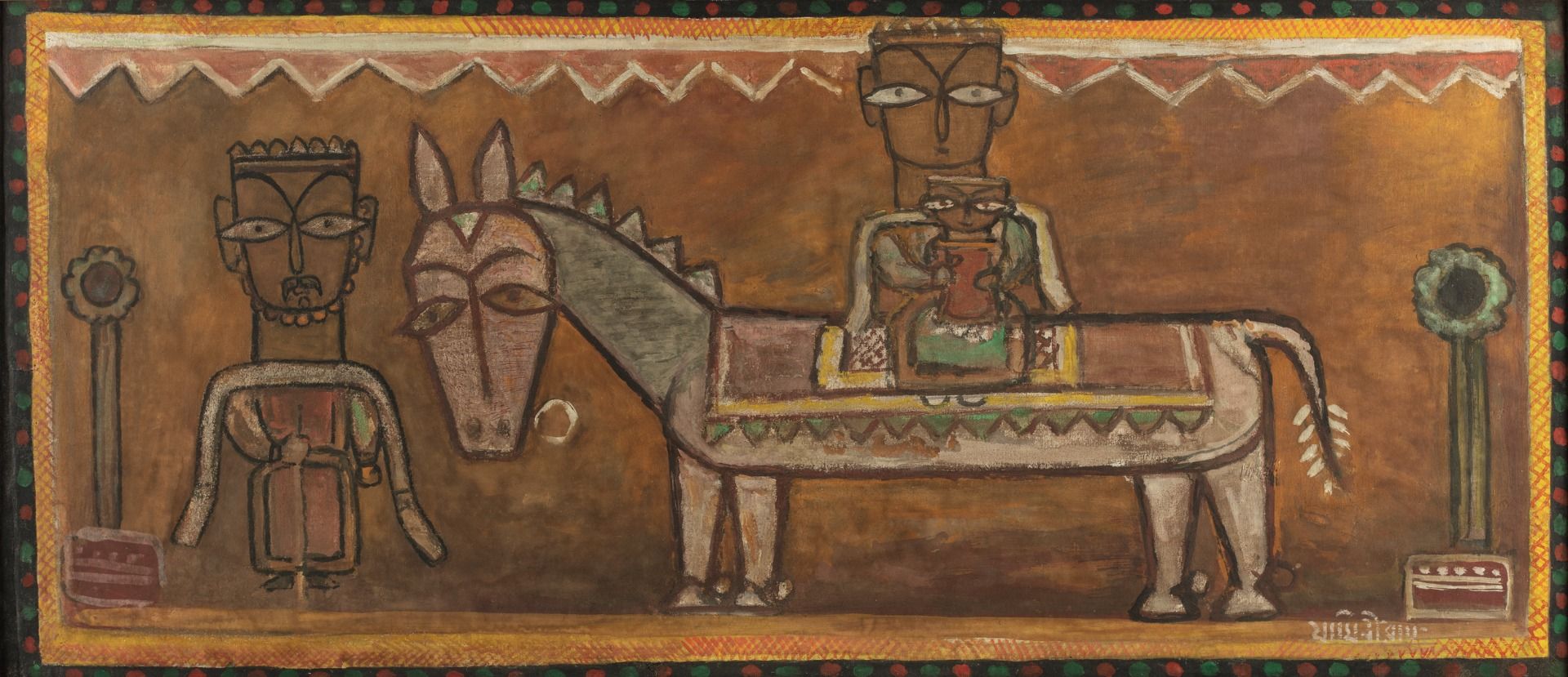

Jamini Roy, Untitled (Flight into Egypt), Tempera on canvas, 19.5 x 45.7 in. Collection: DAG

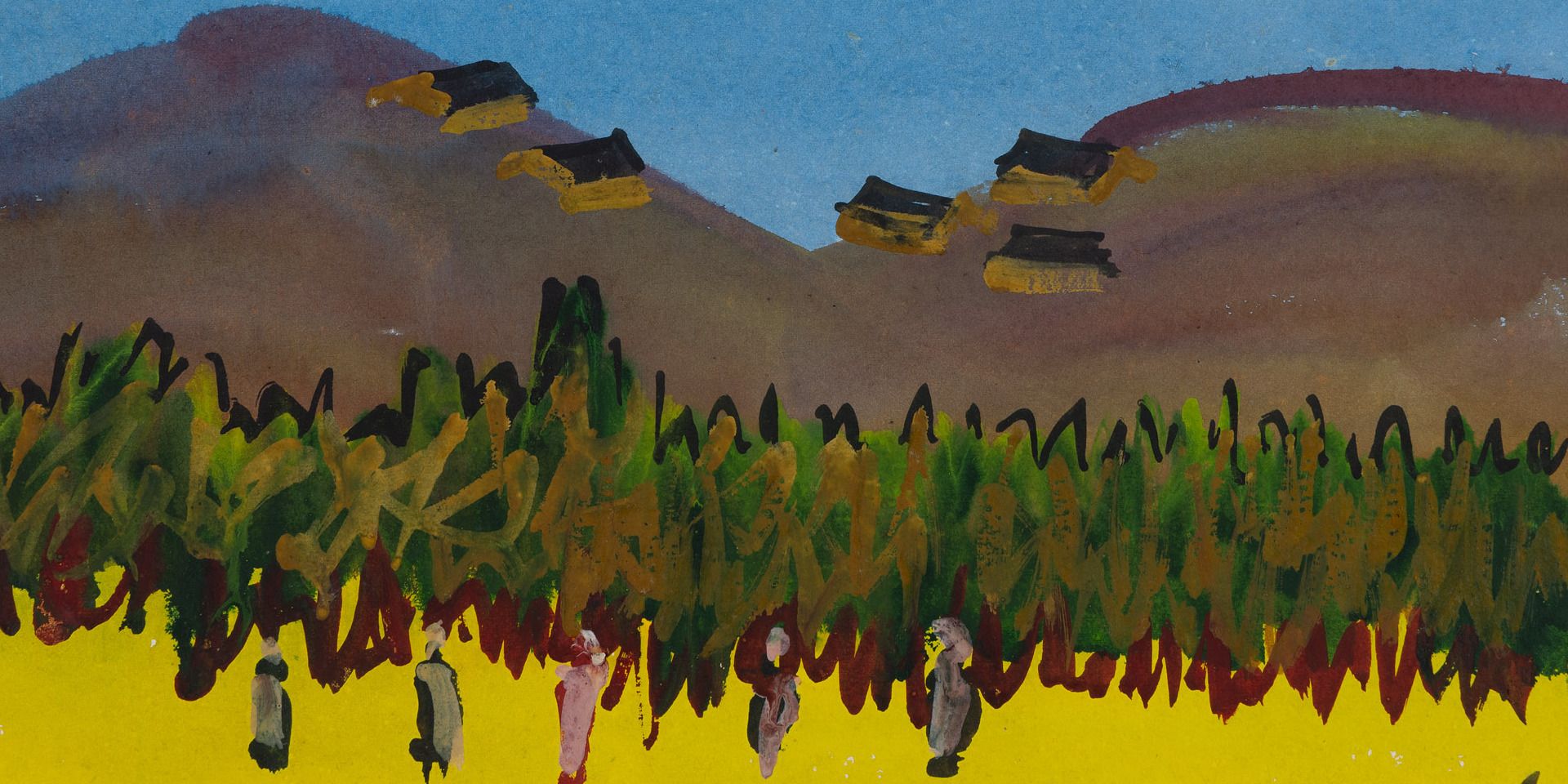

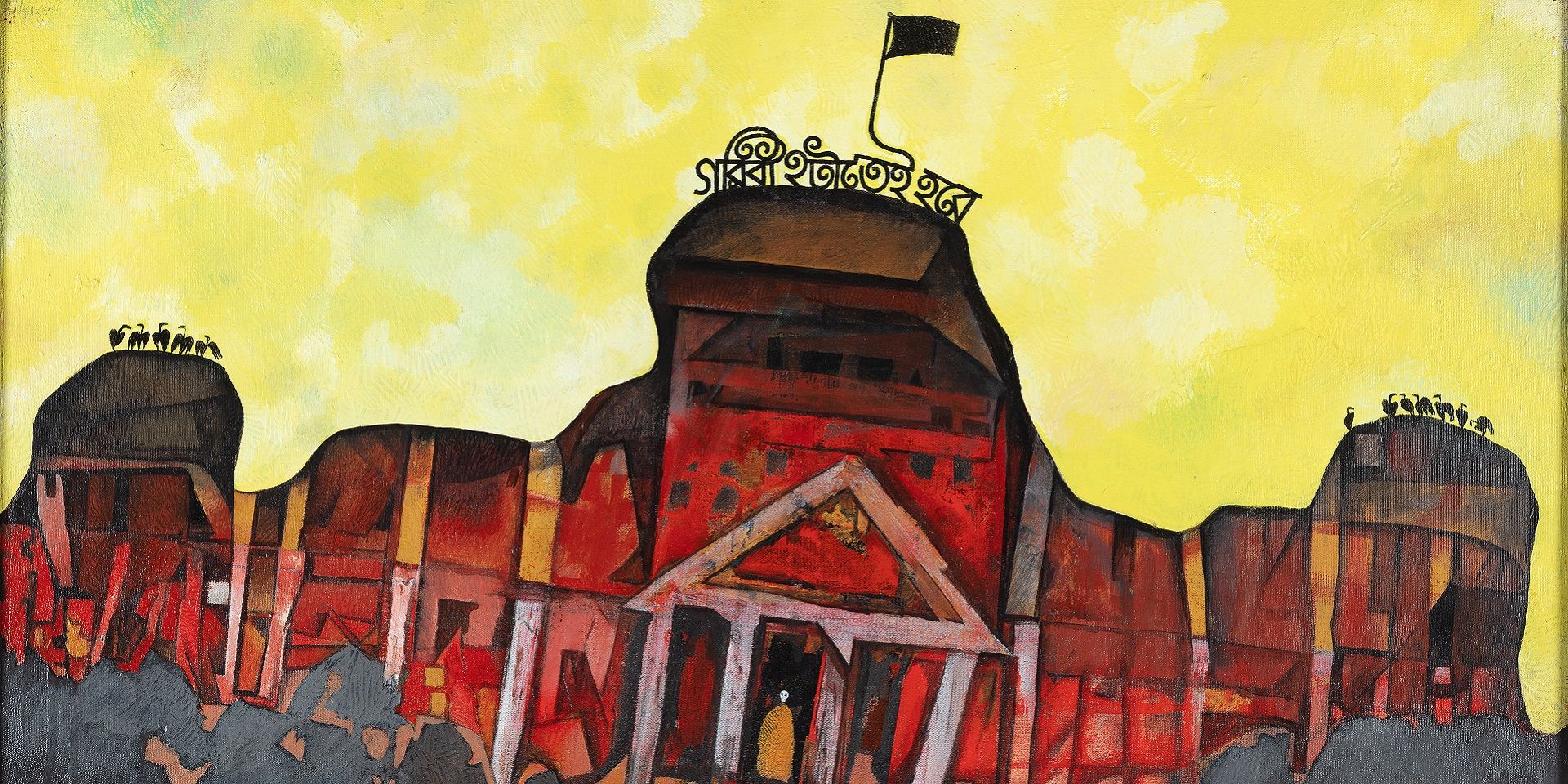

High modernism, or abstract modernism, is something that influences the universal secular models. Abedin deliberately returns to ethnic folklore as a way of marking a secular specificity in a state where secularism was not a state doctrine; as does Nandalal in a different way. What is your language of modernism that would not be about abstraction, or impressions, or expressionism, etc.? In Nandalal’s case, he is also looking at far eastern sources. In the 1930s and ‘40s you have writers like Dinesh Chandra Sen and Jasimuddin attempting to recover an authentic Bengali identity, and that is where Abedin is coming from. What Sadequain does in West Pakistan is to take a Sufi saint and play with that image and, therefore, has to face some amount of controversy, but the critique that he is not modern enough can be placed vis-à-vis the sort of critique that Abedin faces. Qamrul Hassan, who calls himself a patua, is encouraging him (Abedin) to develop an aesthetic of—and from—the region by incorporating folk and rural art practices with a linguistic and cultural basis. It is very much in that sense that Abedin lends himself to becoming an iconic figure; he is a Muslim, East Bengali, and he is modern.

|

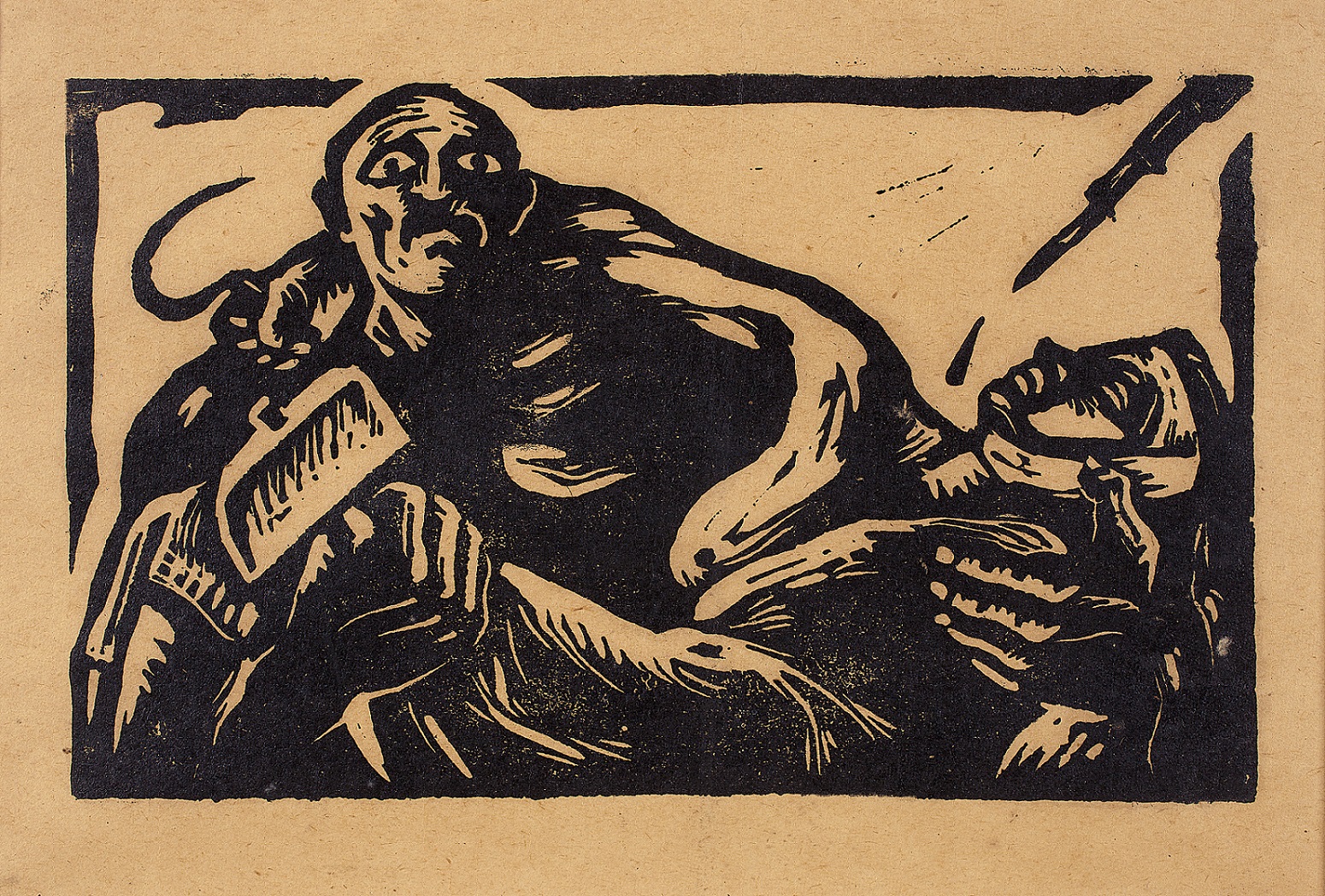

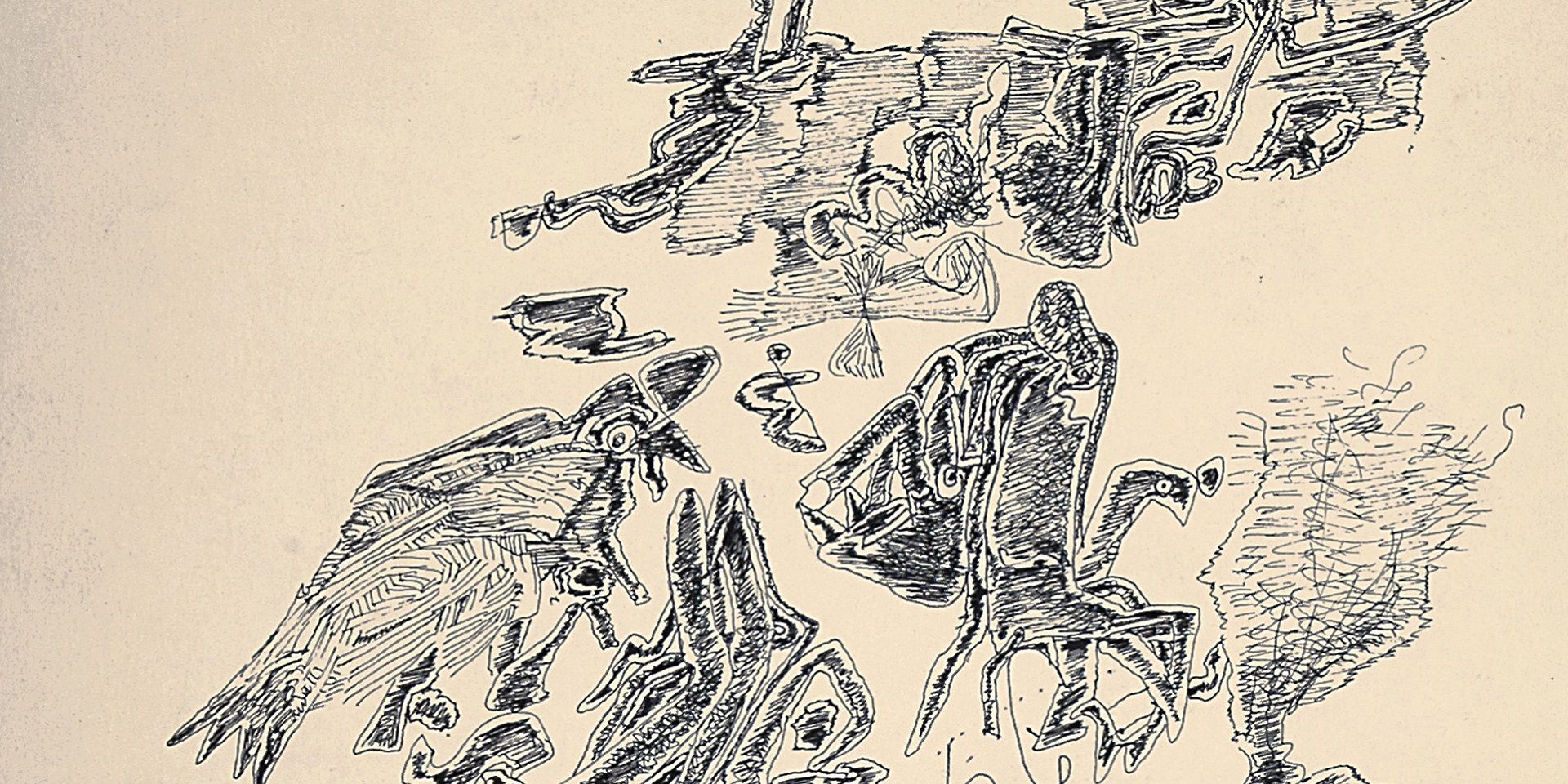

Zainul Abedin, Untitled, Woodcut on newsprint paper. Collection: DAG |

|

Qamrul Hassan, Untitled, Linocut on paper. Collection: DAG |

Q: In her essay on the goddesses of modern India, Sumathy Ramaswamy writes about the resignification of the Statue of Liberty as the Dalit Ma or Angrezi Devi popularized as the symbol of a unified Dalit tongue in the mid-2000’s. She traces the transcultural history of the iconic New York statue to a peasant woman working in the fields of mid-nineteenth century Egypt. How do you think such a politically charged and arguably polysemous icon, adopted for the cause of a Dalit secular politics and imbricated in a ritualistic fervor, might act as an effective counterpoint to the hegemonic claims of a Brahminical-masculinist Hindu nationalism?

Dr. Guha-Thakurta: This was really about the Dalit claim to English and the argument that the British ‘came too late and left too soon’. What is more interesting to me is the popular currency of a particular icon like that. The more abiding goddess that Sumathy refers to is of course mappus mundi (or the figure of Bharat Mata propped against a cartographic image of India) and she approaches these figures party through her own engagement with what she calls the ‘enchanting labour of the image’.

And the idea that images have agencies is, of course, a central argument. Kajri Jain says that art history thinks of the art object as something that has been ‘tamed’, yet we use terms like the ‘image’ which speaks to us in certain ways when seen through a secular lens. So, somewhere that idea of the ‘efficacious image’ that Kajri talks about in the context of calendar or bazaar art, referring to the authority of visual evidence and the imaging of identity becomes important.

|

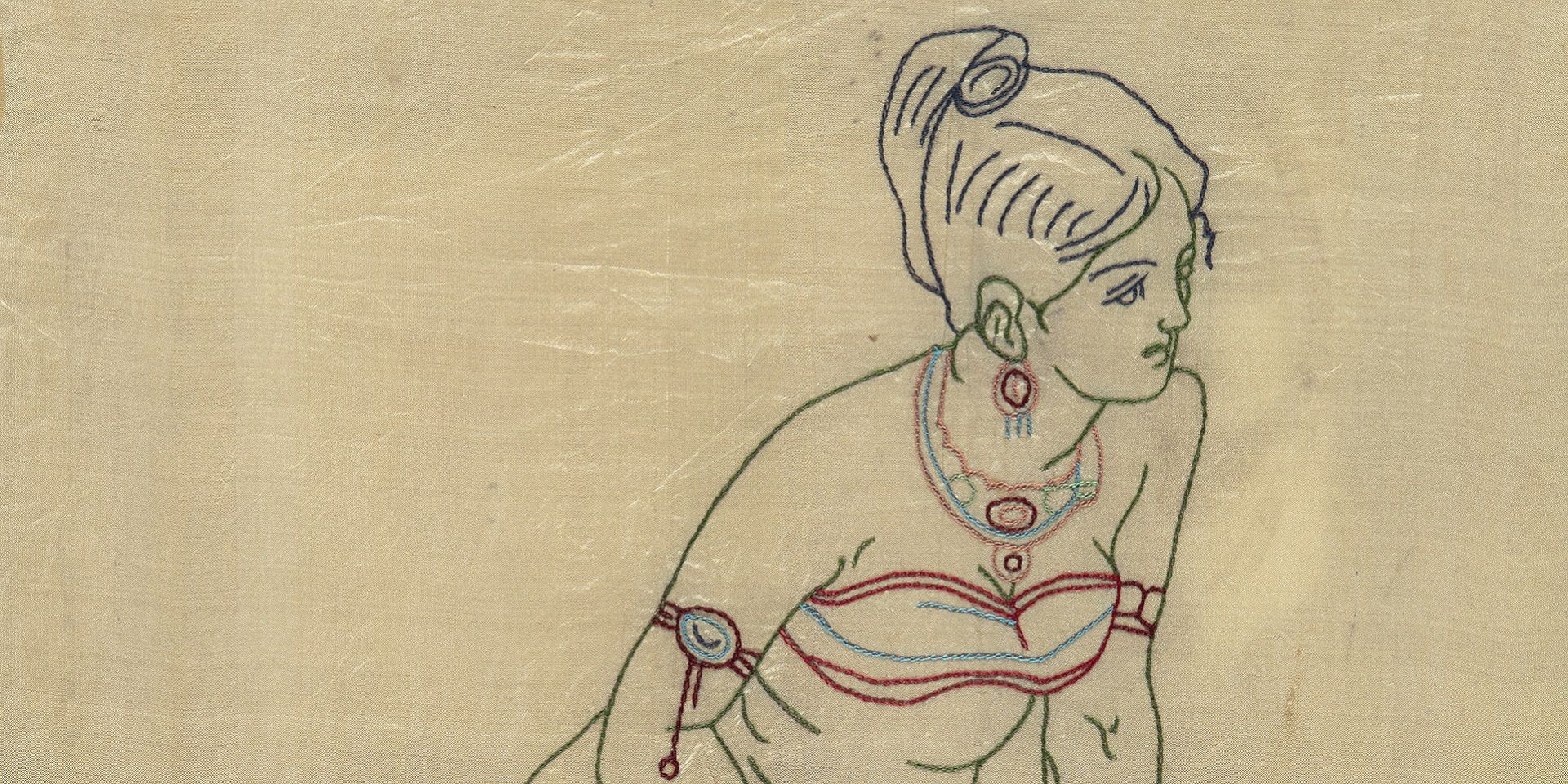

Anonymous, Untitled (Tripura Sundari), Oil on canvas. COllection: DAG |

The question that often arises in religious discourses is—(to echo the title of a book by W. J. T. Mitchell) ‘what do images want’? They have their own desires, and the images are living not only because of the relationship they enter into with the spectator but also for occupying a mutual field of resonance. I think what is also interesting is that each of the goddesses Sumathi brings up have very specific historical contexts in which they are most vibrant and most efficacious. But today, in the D. M. K.-led agnostic culture in Tamil Nadu, we do not have goddesses. Sumathi’s work was heavily criticized by the Dravidian lobby, mostly because she is a Tamil Brahmin, and what is interesting is that we are defined by our caste even in the world of scholarship. Secondly, she was working with a lot Brahminical journals. However, it was definitely appreciated as a pioneering work of cultural history. The life of each of these goddesses in the public domain become particularly charged in specific political moments, and that is one of the interesting aspects of the essay.

|

Anonymous (Kalighat pat), Untitled (Durga Puja) , Watercolour and gouache on paper pasted on cardboard. Collection: DAG |

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debating secularism in South Asian Art with Tapati Guha-Thakurta

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Remembering Ambadas with art critic Prayag Shukla

Ankan Kazi

August 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Discovering the lives of Bengal's women artists with Soma Sen

Ayana Bhattacharya

September 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Becoming New Delhi: A Conversation with Swapna Liddle

Ankan Kazi

October 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Visualising the Freedom Struggle: A conversation with Vinay Lal

Ankan Kazi

November 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Building an Empire: A Conversation with Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Ankan Kazi and Giles Tillotson

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Designing Calcutta: Navigating the city with architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

December 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Unarchiving the City: A Conversation with Swati Chattopadhyay

Shreeja Sen and Vinayak Bose

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Partition and Popular Art: A Conversation with Yousuf Saeed

Ankan Kazi

January 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Singing to Kali: A Conversation with Rachel F. McDermott

Ankan Kazi

February 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

The Asian Moment: A Conversation with Sugata Bose

Ankan Kazi

May 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Rudi von Leyden's Indian Art Adventures: With Reema Desai Gehi

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Objects and the Museum: A Conversation with Sudeshna Guha

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2024

Conversations with Friends

Art of the Graft: A Conversation with Holly Shaffer

Ankan Kazi and Bhagyashri Dange

June 01, 2025

Conversations with Friends

Anita Vachharajani on Writing about Art for Children

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2025