Visualising the Dandi March at Santiniketan

Visualising the Dandi March at Santiniketan

Visualising the Dandi March at Santiniketan

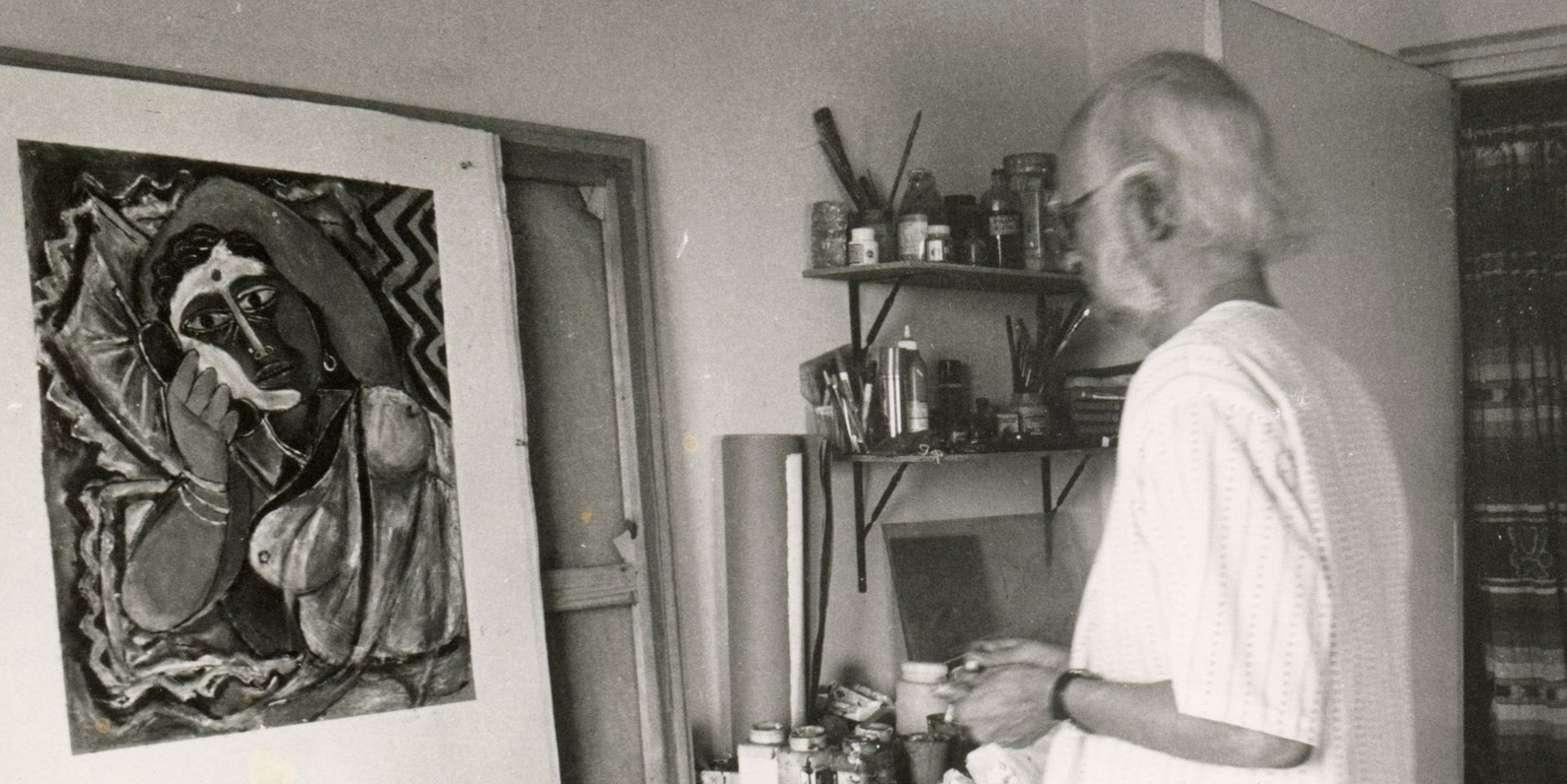

Mahatma Gandhi and Nandalal Bose at Santiniketan, Unidentified photographer. Collection: DAG

Art historian Debdutta Gupta recounts the events surrounding the making of a famous linocut by Nandalal Bose, just as the Dandi March (or, the Salt Satyagraha) was being undertaken in the 1930s.

Rabindranath Tagore met Mahatma Gandhi and conducted several important dialogues with him, especially on the nature of the national movement and the cultural implications of the Swadeshi movement. Similarly, Nandalal Bose, the Principal of Santiniketan's Kala Bhavana since 1921, also met Gandhi when the latter visited Santiniketan. Even though the national movement was regularly targeted by British authorities, Bose and many other students and teachers at Santiniketan continued their support for Gandhi's mass movement as it entered the decade of the 1930s. How did Bose contribute to this movement?

|

Nandalal Bose's linocut of Gandhi, seen here at the Gandhi Memorial Museum at Barrackpore, West Bengal. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

The year was 1930 and the storm of Swadeshi was blowing across the nation. Meanwhile, Nandalal Bose was preparing to send his son, Biswarup, for art training in Japan from Santiniketan’s Kala Bhavana. He wanted Biswarup to learn about coloured woodcut-making, printing and framing images and various other techniques of craftsmanship. Bose thought that the next generation of Kala Bhavana students would get the opportunity to learn such techniques from Biswarup. While this was going on, news filtered in that Prabhatmohan Banerjee, a student of Kala Bhavana, had joined the Swadeshi movement. And along with him, many others from Santiniketan, such as the local compounder and Bose's dear friend Akshay Babu, had also joined. There were several students from across India studying in Santiniketan at the time. That year, however, Prabhatmohan was the only Bengali student who had joined the Swadeshi movement.

|

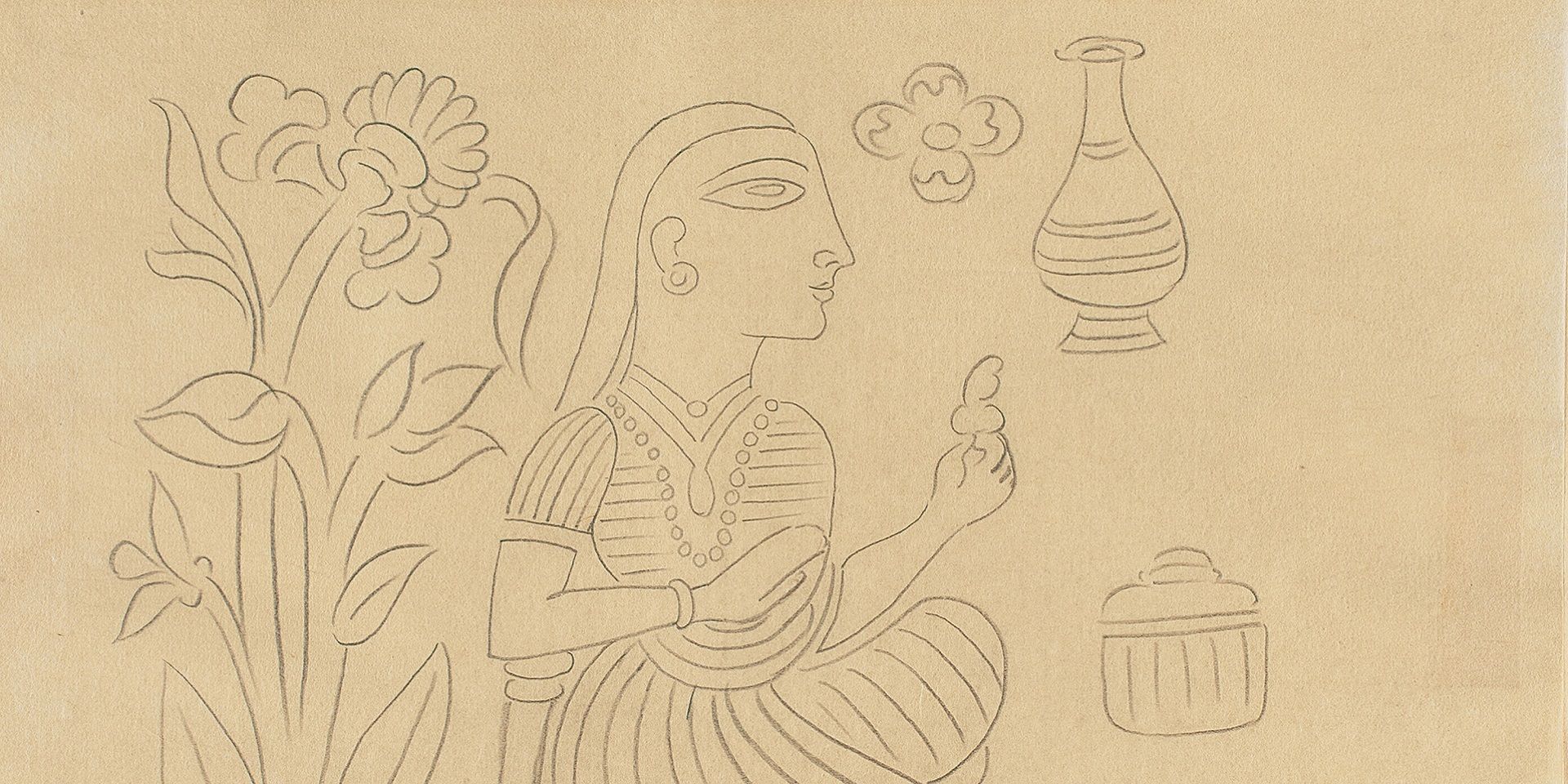

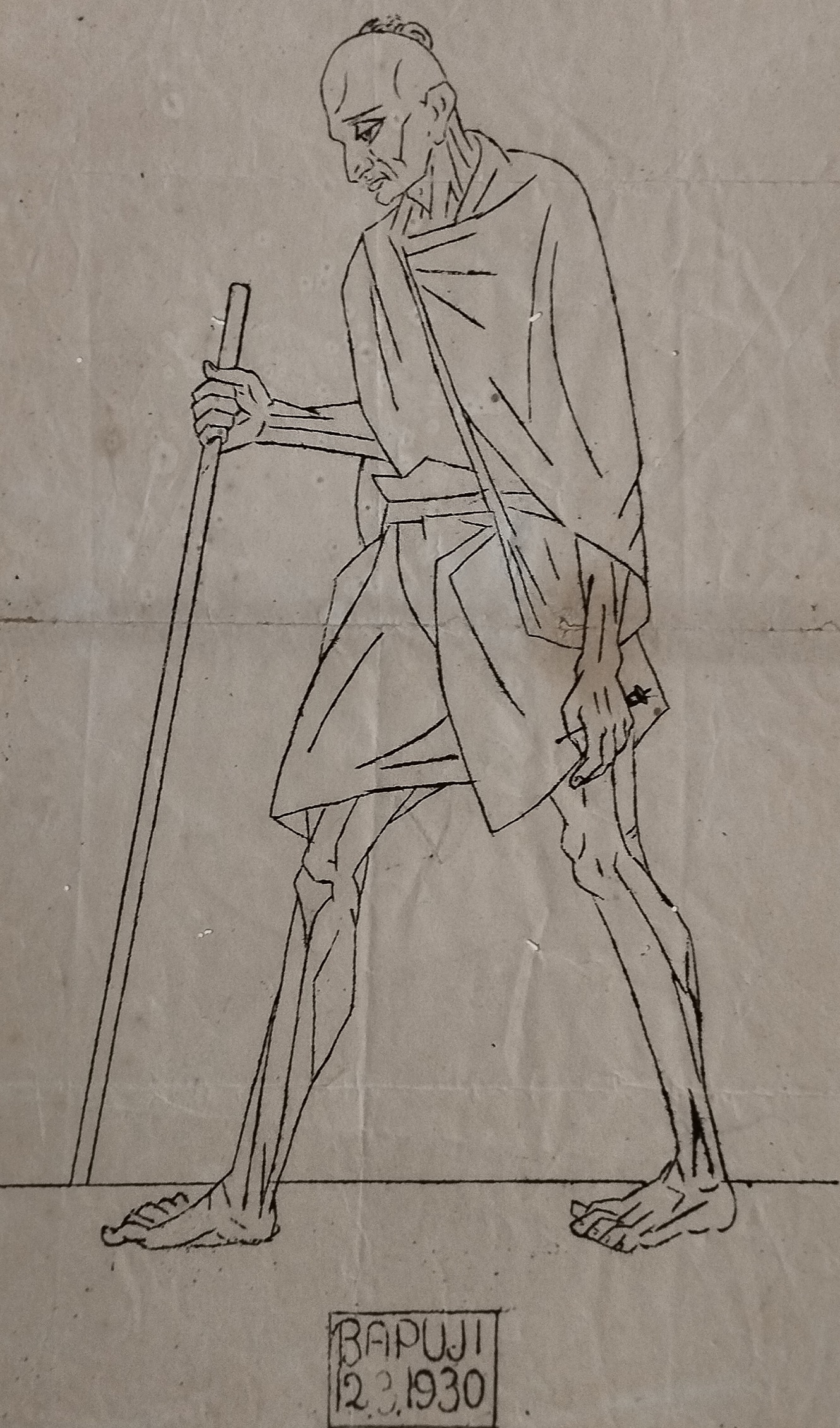

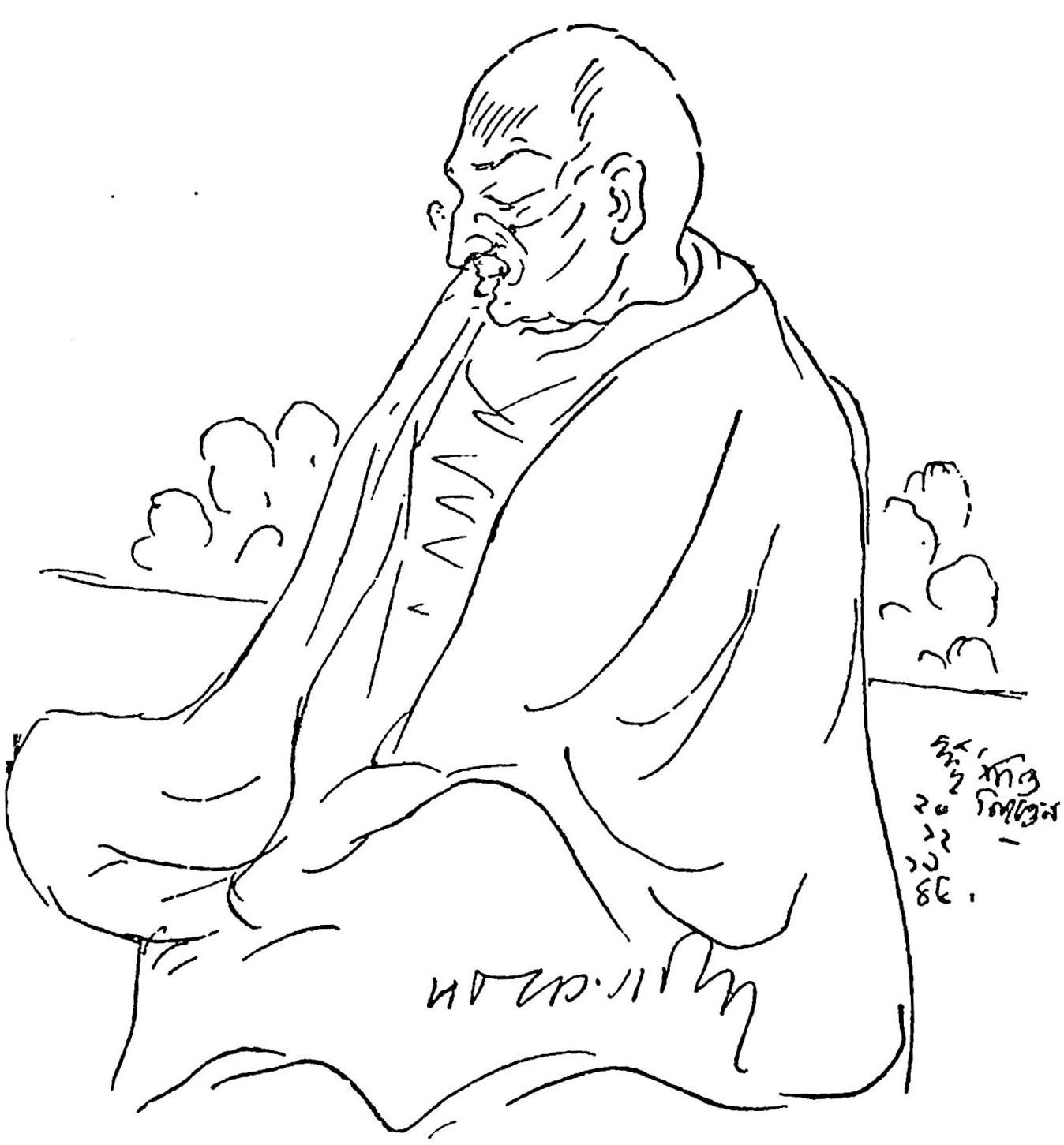

An early drawing of the iconic image by Nandalal Bose. The date inscribed at the bottom shows it to have been made on the day the march began. The final linocut image bears a date from a month later. Image courtesy: Subir Bandyopadhyay and Debdutta Gupta |

In the same year, when Akshay Babu went on the Dandi March with Gandhiji from Sabarmati, Prabhatmohan was breaking the salt law under the leadership of the revolutionary Satish Chandra Dasgupta in Mahish Bathan (a village in Bengal). After staying in the village for a few days Prabhatmohan was sent on Calcutta. In the same year, when Akshay Babu went on the Dandi March with Gandhiji from Sabarmati, Prabhatmohan was breaking the salt law under the leadership of the revolutionary Satish Chandra Dasgupta in Mahish bathan (a village in Bengal). After staying in the village for a few days Prabhatmohan was sent on Calcutta. In a November-December (1966) issue of Des magazine, Prabhatmohan Banerjee wrote about his personal experiences from that day in the past in an article titled ‘Despremik Nandalal’ (Nandalal, the patriot), focusing on some unique events. He writes, ‘After staying in Mahish bathan for some time, I was sent to Calcutta. Our office was in a big house by Gol Dighi (also known as College Square, located close to the Calcutta University buildings), where leaders and workers used to come from different parts of Bengal. The newspaper ‘Satyagraha Sangbad’ (News of the Satyagraha) was already being published in cyclostyled sheets under the editorship of Satish Babu from some time before that. I was working as the printer. After the enforced closure of the newspaper, the need for it only increased, and workers from different districts of Bengal would come by train to take contraband copies of the paper every morning. Volunteers like myself would work all day and half the night to print thousands of these copies and bind them together in bundles. At that time, ‘Mastermoshai’ (‘The revered teacher’, referring to Nandalal Bose) came to Calcutta to make arrangements for his son Biswarup’s travel to Japan. He used to come to our office to spend some time almost every day to inquire about our work. Upon my request, he gave me a line drawing of the Dandi March work, which I printed in those cyclostyled newspaper sheets with much pride.'

|

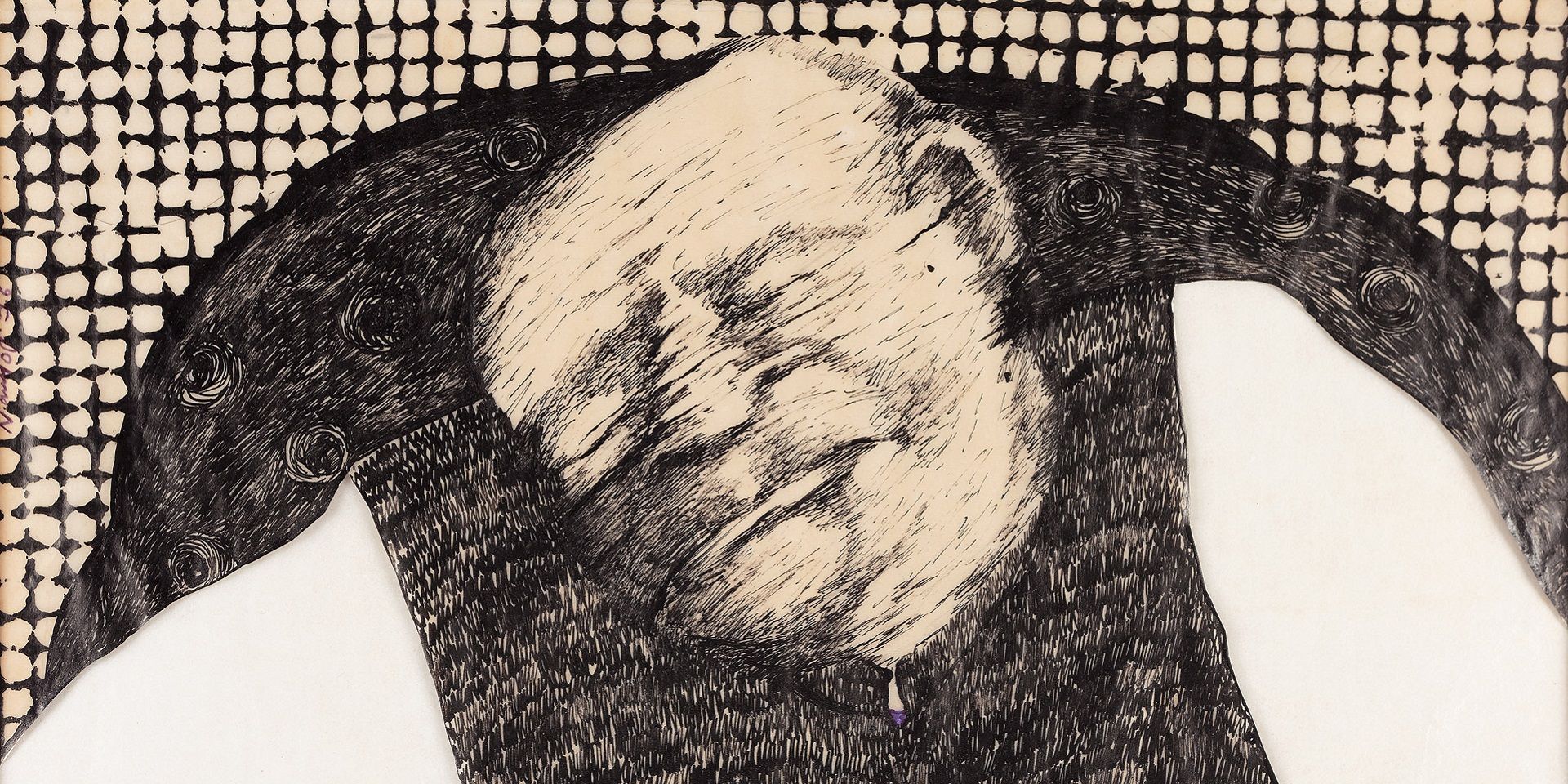

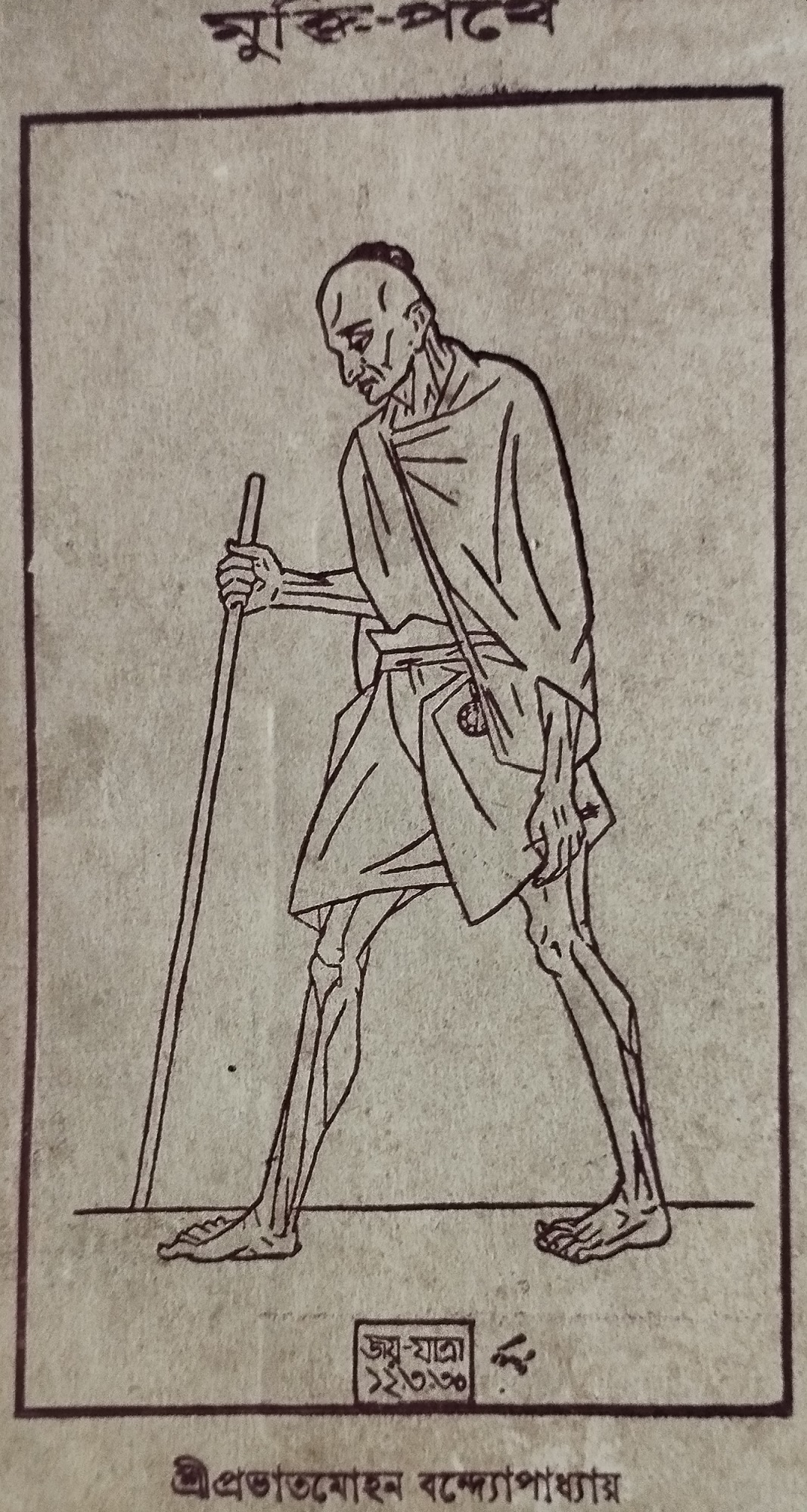

Nandalal Bose's Bapuji on the cover of Prabhatmohan's book. Image courtesy: Subir Bandyopadhyay and Debdutta Gupta |

One of the most popular works of Indian art, a linocut titled ‘Bapuji’, was created a month after Nandalal made this line drawing. Here, ‘Bapuji’—referring to Gandhi’s popular moniker—has a bell in his hand and a tiki or top-knot on his head that is reminiscent of Chanakya—a royal advisor, philosopher and economist, also known as Kautilya, from the fourth and third centuries BCE who is generally credited as the author of the treatise Arthashastra. And when Prabhatmohan published his book Mukti-Pothe (On the Path to Freedom) in 1932, the cover bore a similar image of Gandhi at the Dandi March by Nandalal Bose. However, the caption to this work was not ‘Bapuji’ in English, but Joy-jatra (Victory March) in Bengali, along with the date ‘12/3/1930’. This was the same date inscribed in the original image that was printed in the cyclostyled sheet. To this new image, Bose had added a pocket watch in Gandhi’s hand—referring to the actual watch Gandhi still retained from his student days, after deliberately giving up every sign of an English ‘gentleman’s’ attire. The original image from the cyclostyled sheets, however, is untraceable today. This is possibly due to the fact that extant copies may have been seized by authorities from the revolutionaries’ office. The line drawing on the book cover is also impossible to find today because the book was proscribed by the British administration. This is the brief, practically unknown, history of the origins of the famous black and white linocut titled ‘Bapuji’ by Nandalal Bose, owing to his association with the revolutionaries who operated out of their small office next to the Gol Dighi. What started out as a simple line drawing, went through a few permutations, and emerged as the final linocut that we are all familiar with; and the date on that original drawing, 12/3/1930, marked the beginning of the Dandi March.

Nandalal Bose's drawing of Gandhi, included in Rabindranath Tagore's book on the nationalist leader, titled Mahatma Gandhi. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

|

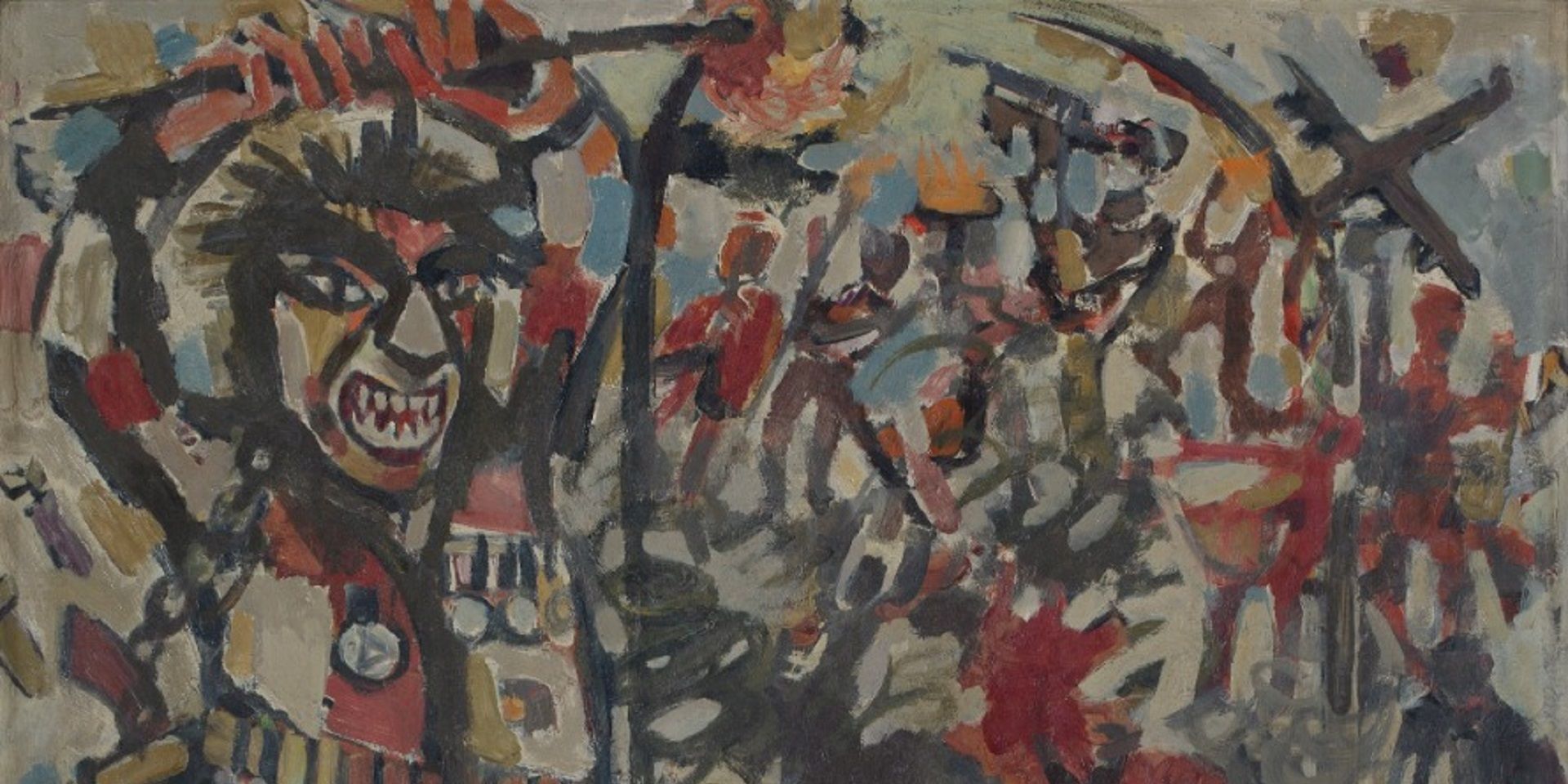

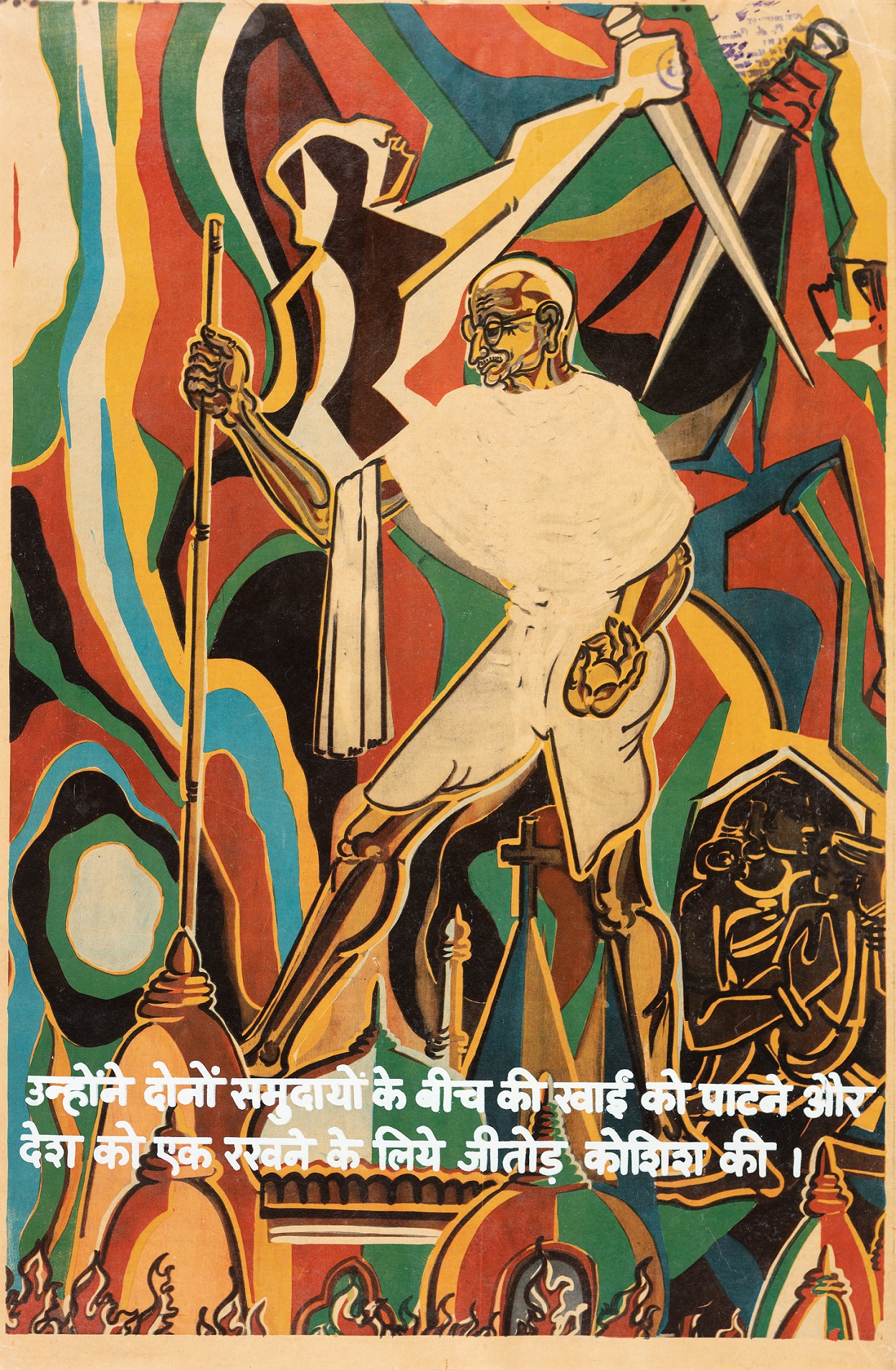

Unidentified artist, Gandhi poster, Offset print and serigraph on paper, 69.9 x 45.0 cm., c. 1960. Collection: DAG |

Popular posters of Gandhi employed similar iconographic details too. In this image, we can also see the pocket watch at his waist, along with the iconic walking stick.

Unidentified artist,

Gandhi poster (detail),

Offset print and serigraph on paper, c. 1960. Collection: DAG

Debdutta Gupta is an art historian, curator and educator at Kolkata's Rabindra Bharati University. His area of interest includes the work of Bengal modernists, exploring little-known facets of works done by major artists like Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Lalitmohan Sen and others.

related articles

Essays on Art

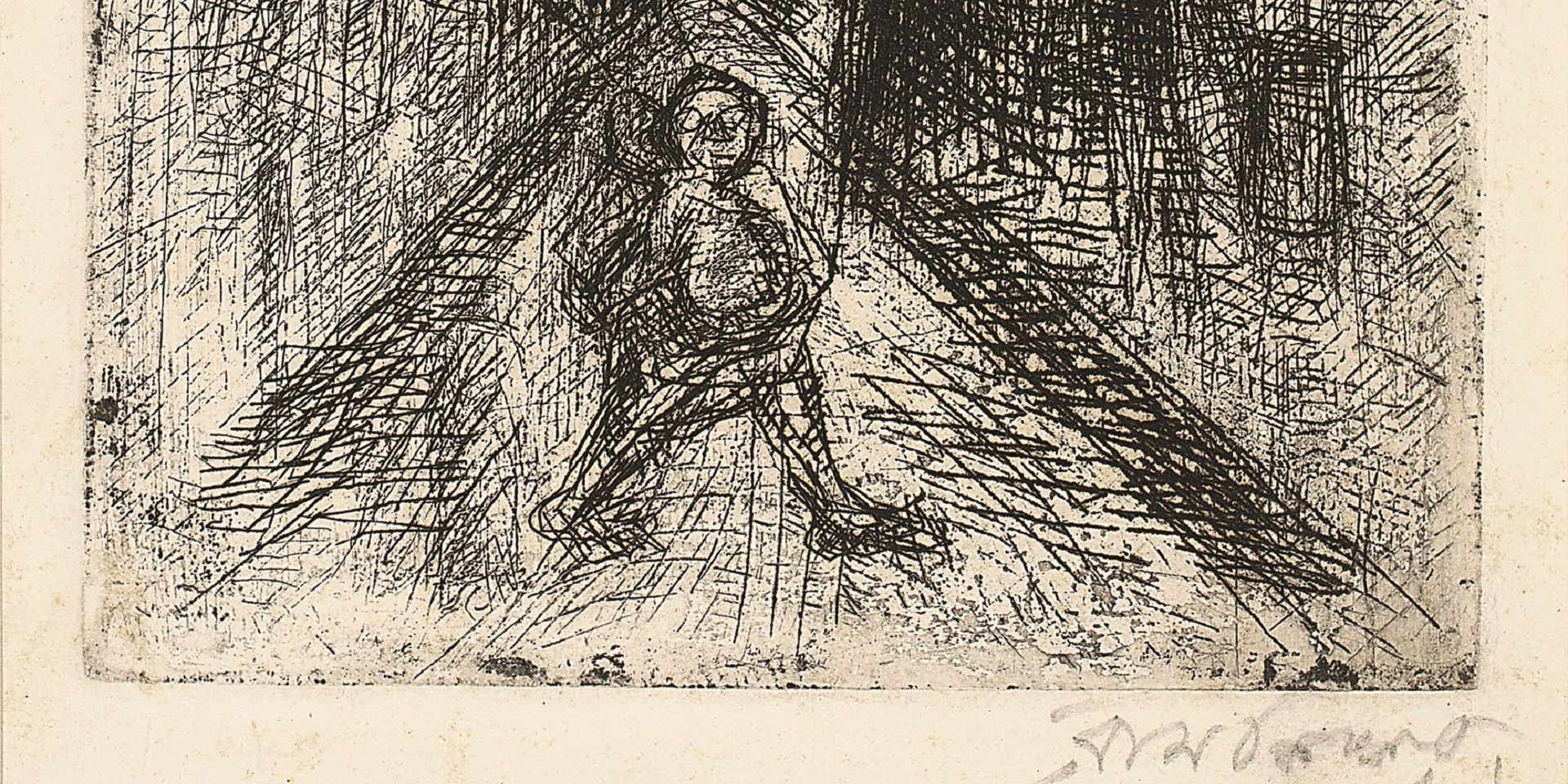

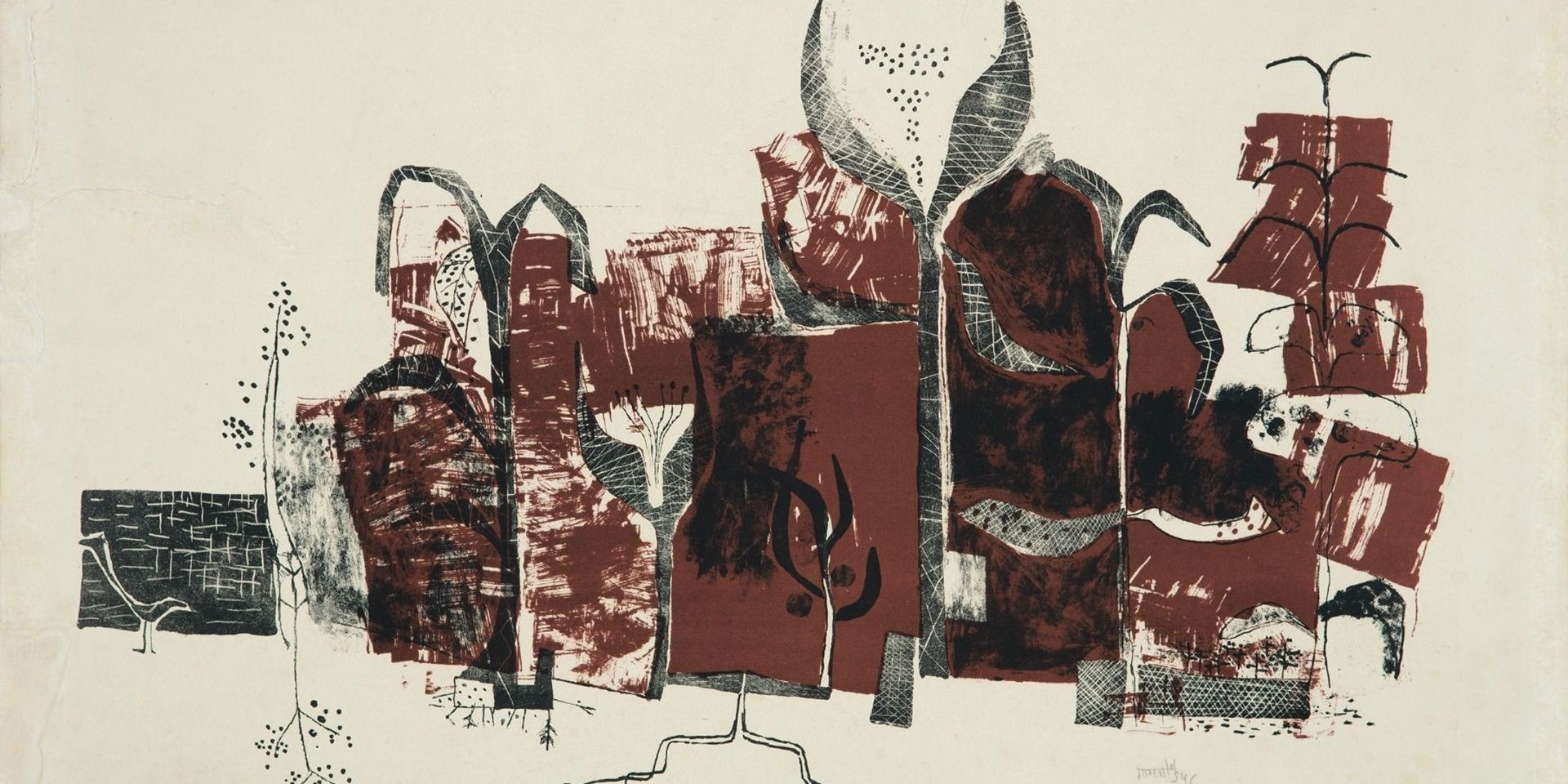

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

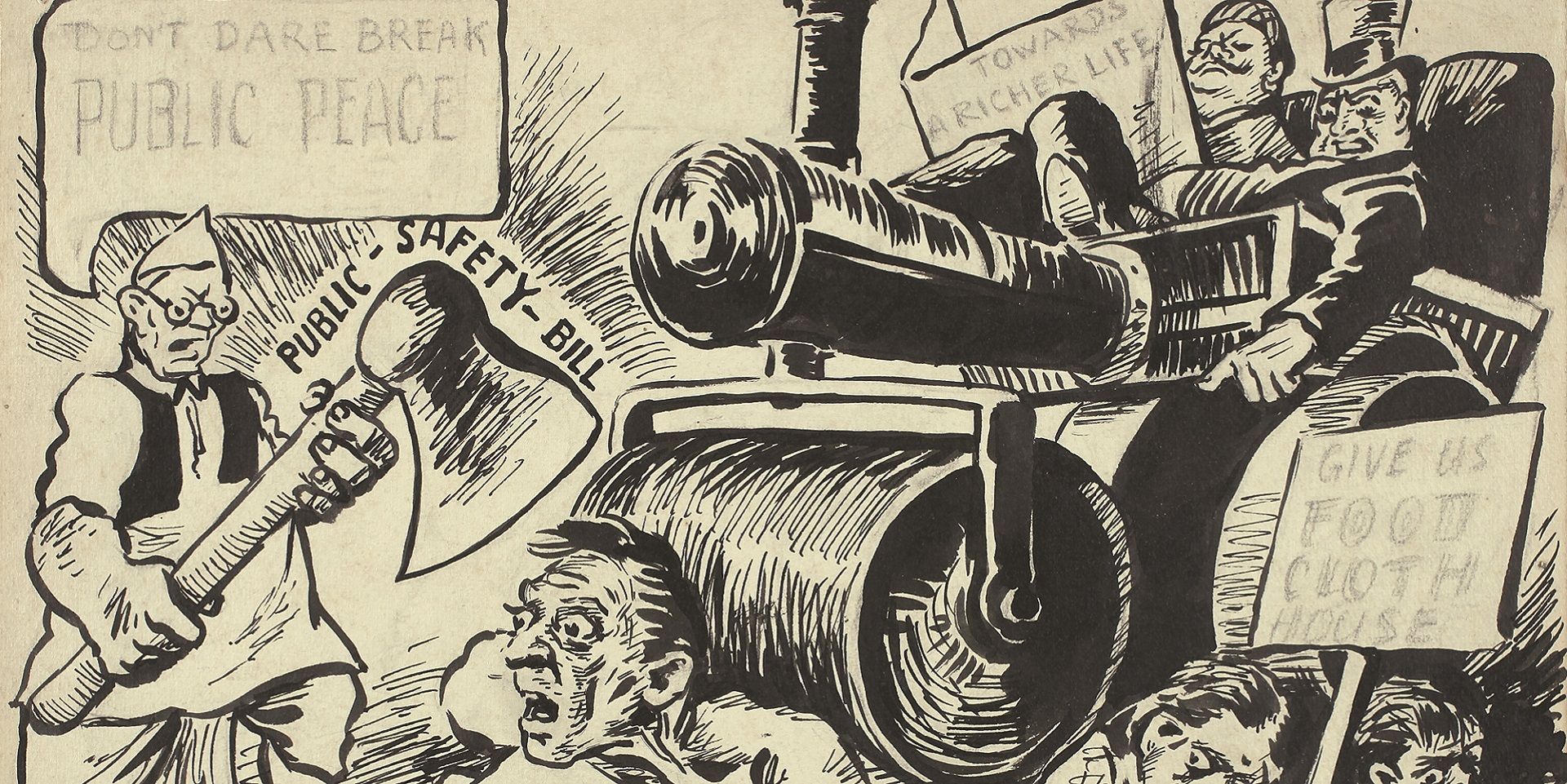

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

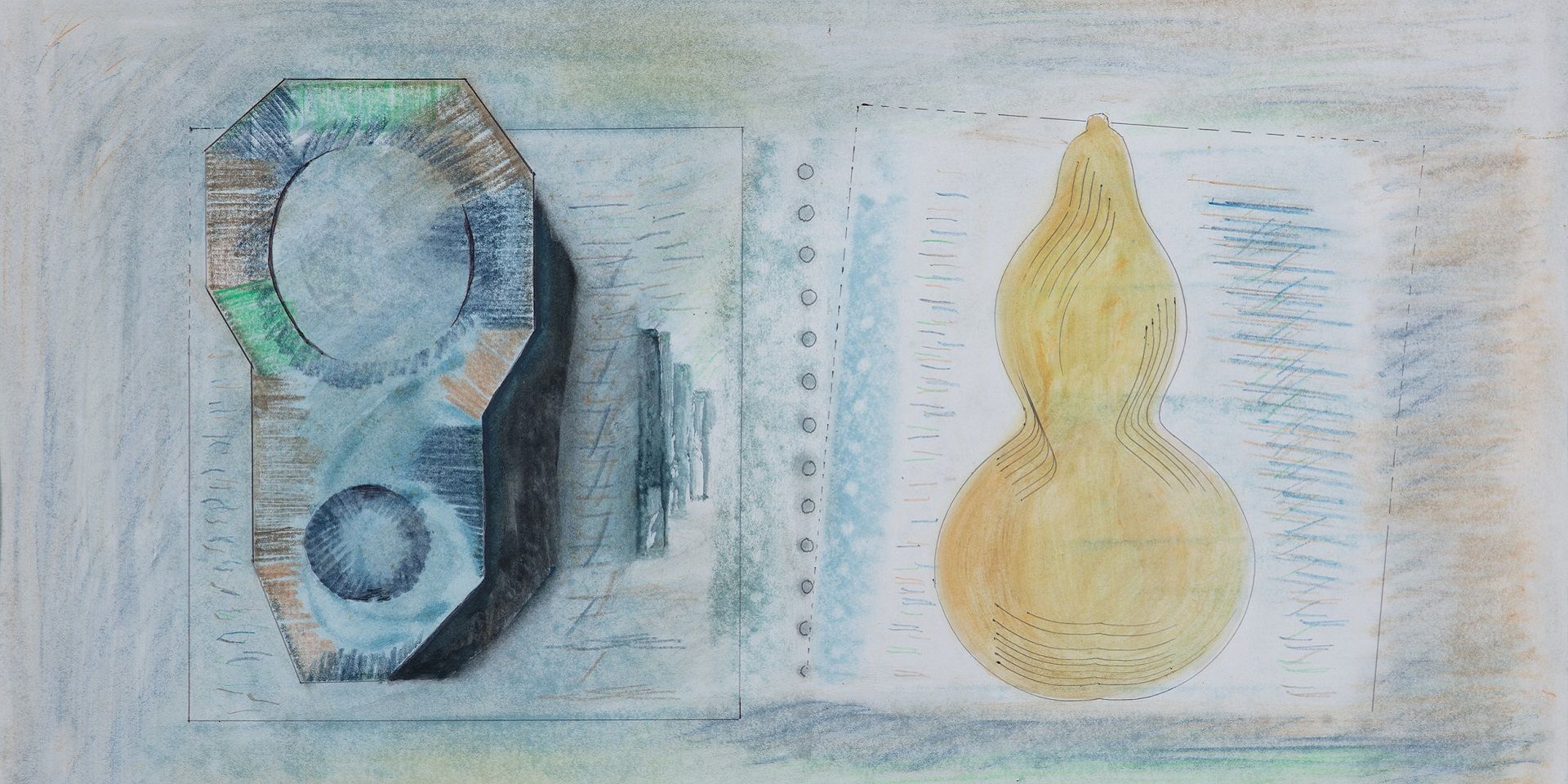

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

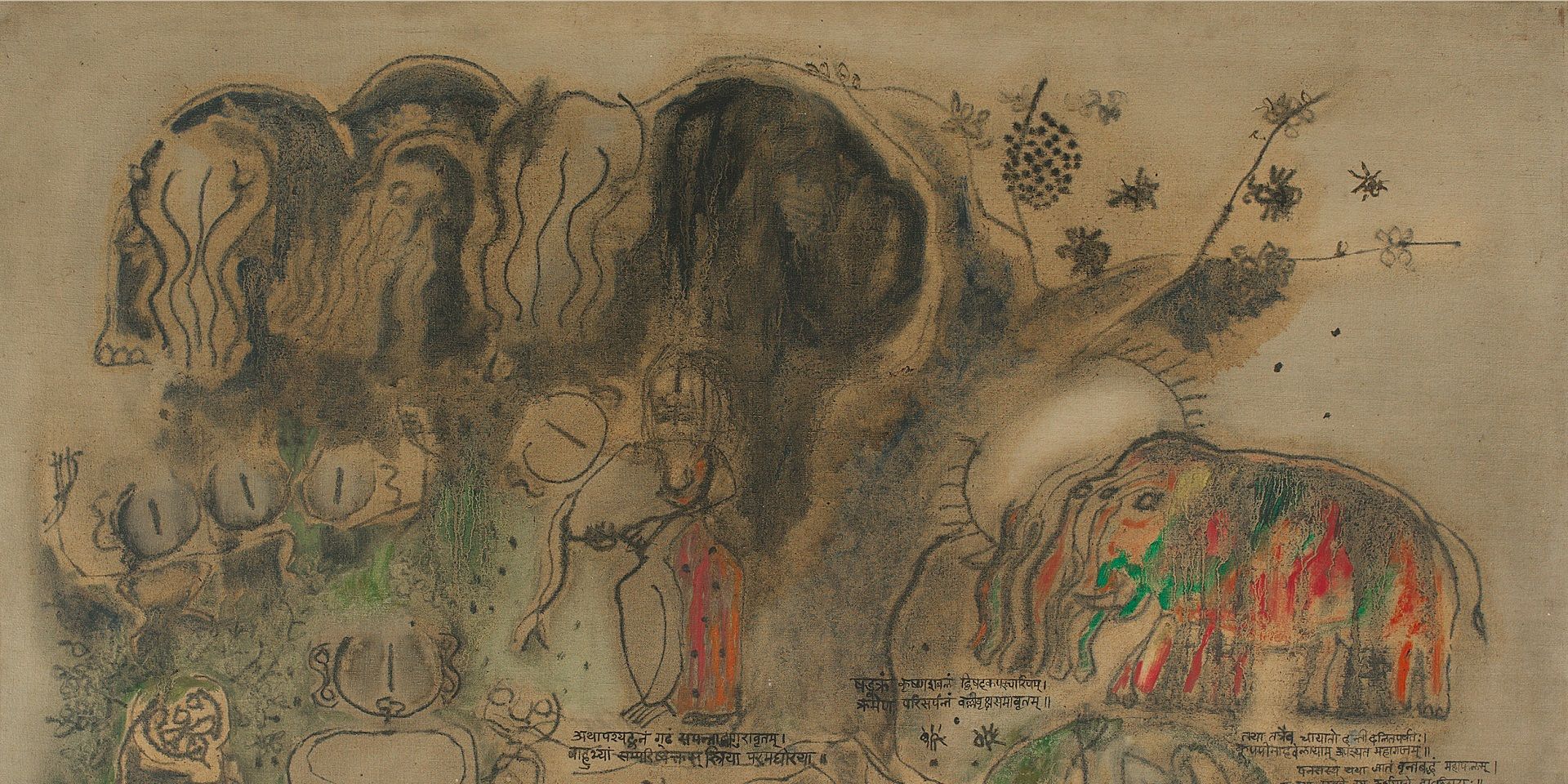

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

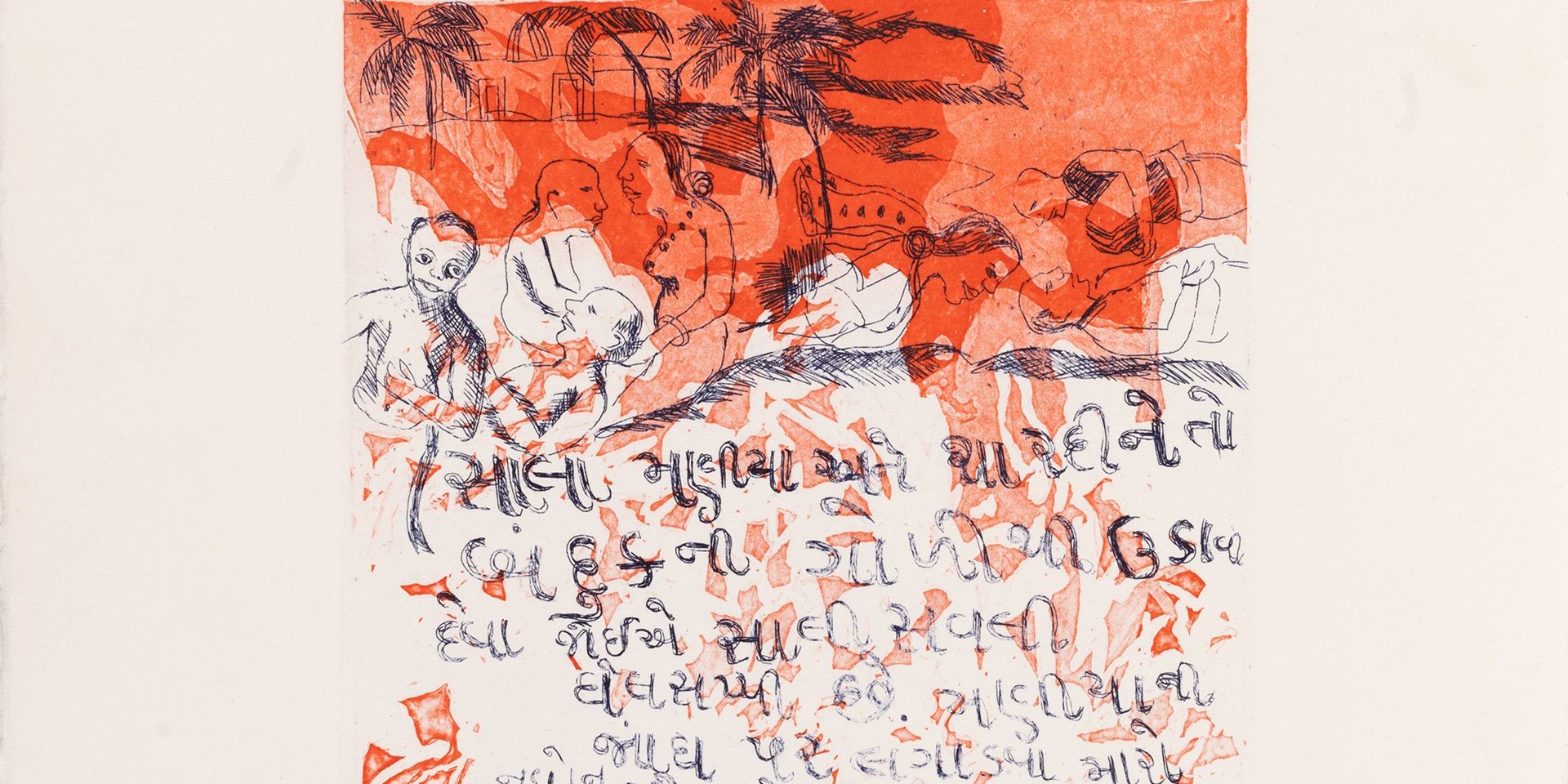

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024