Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Erotics of the Foreign:

On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

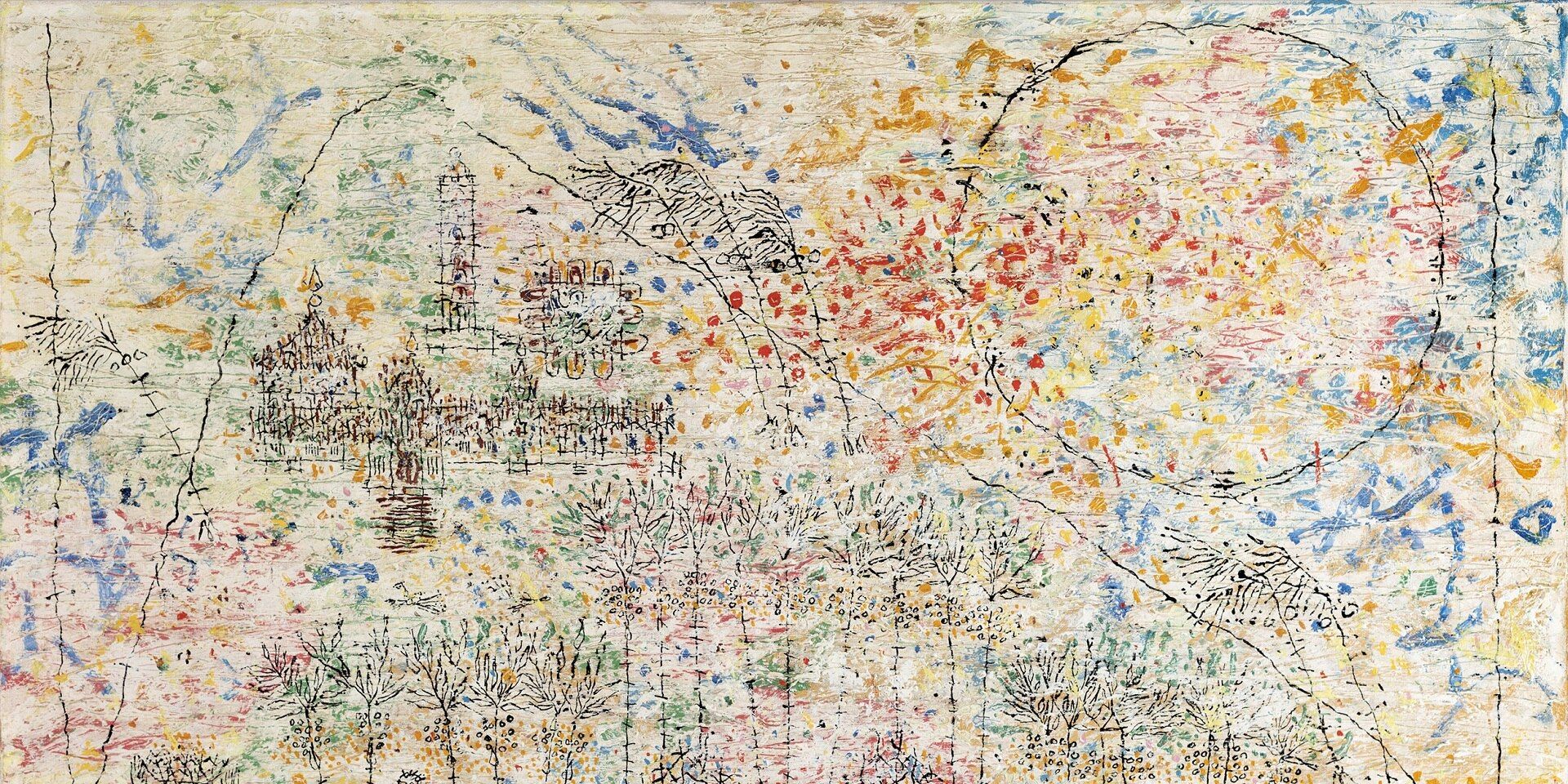

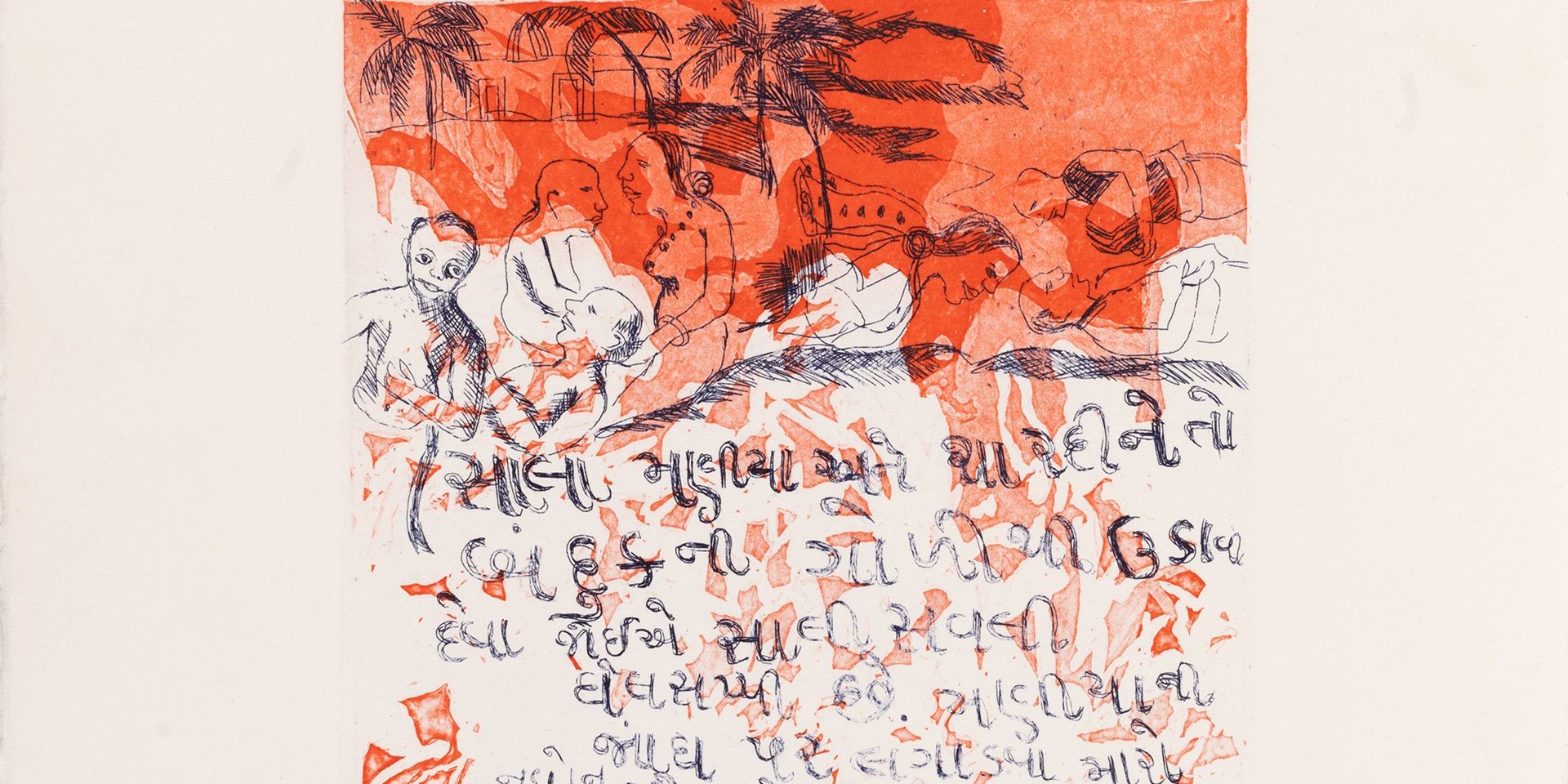

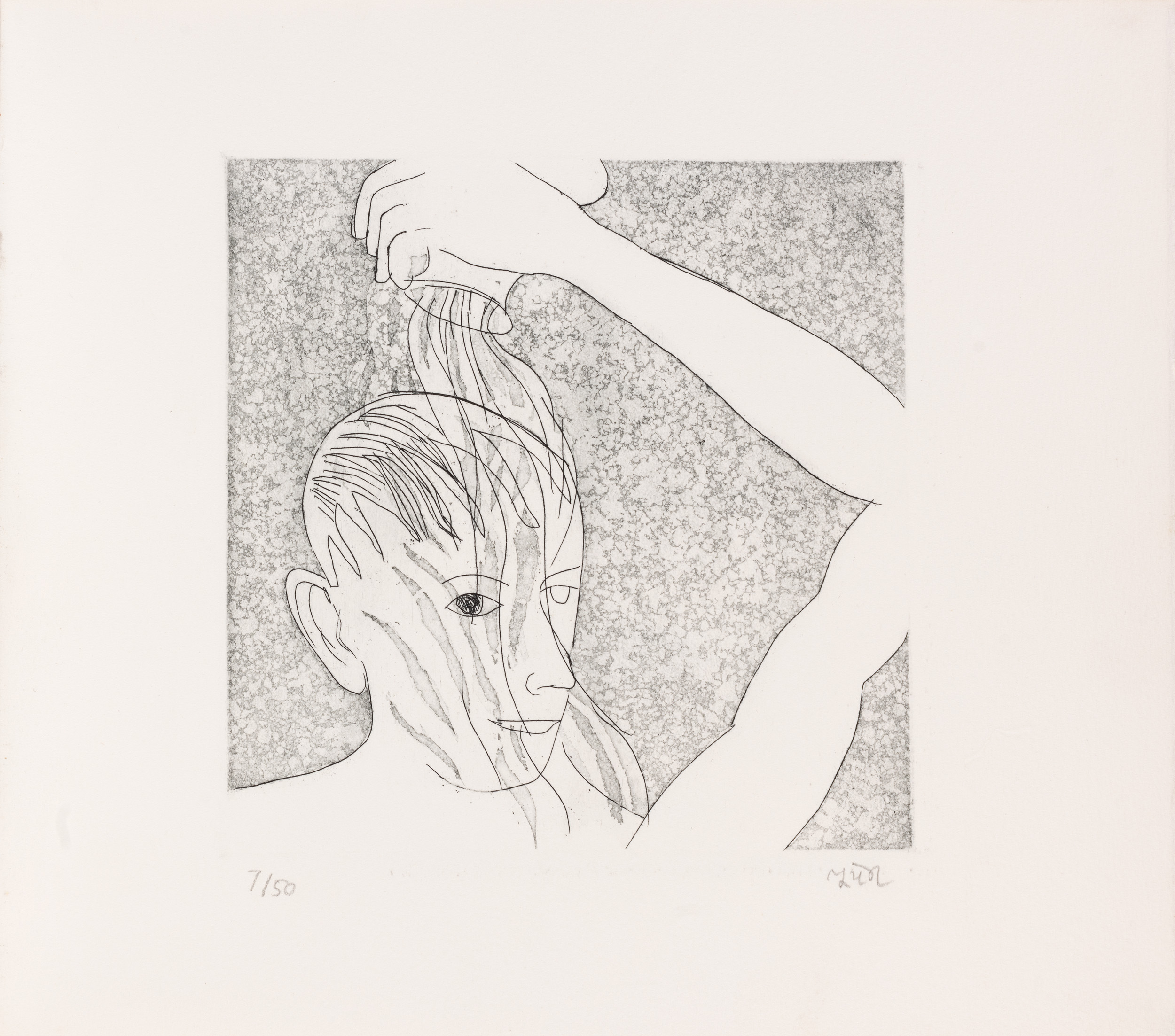

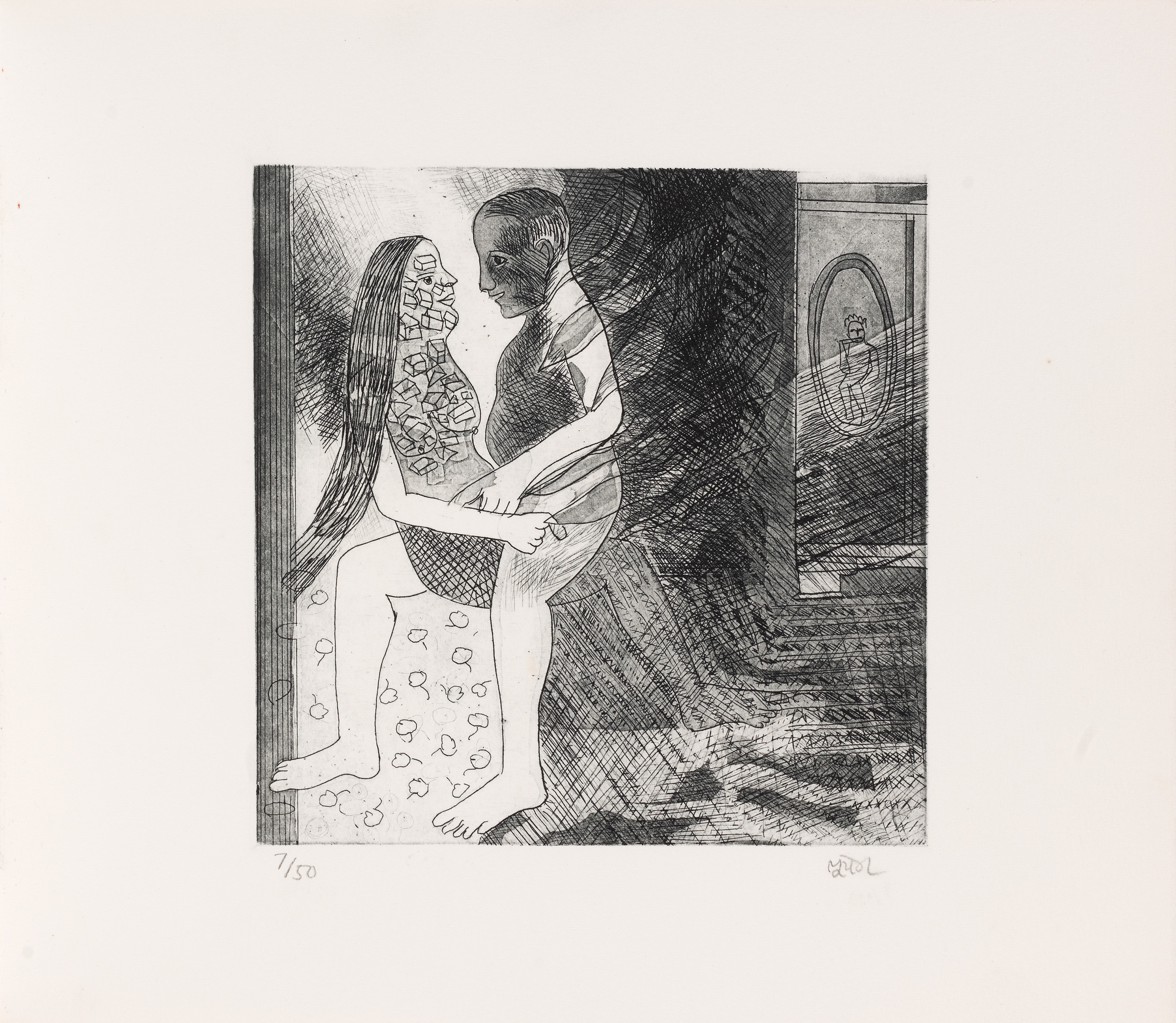

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati) (detail), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

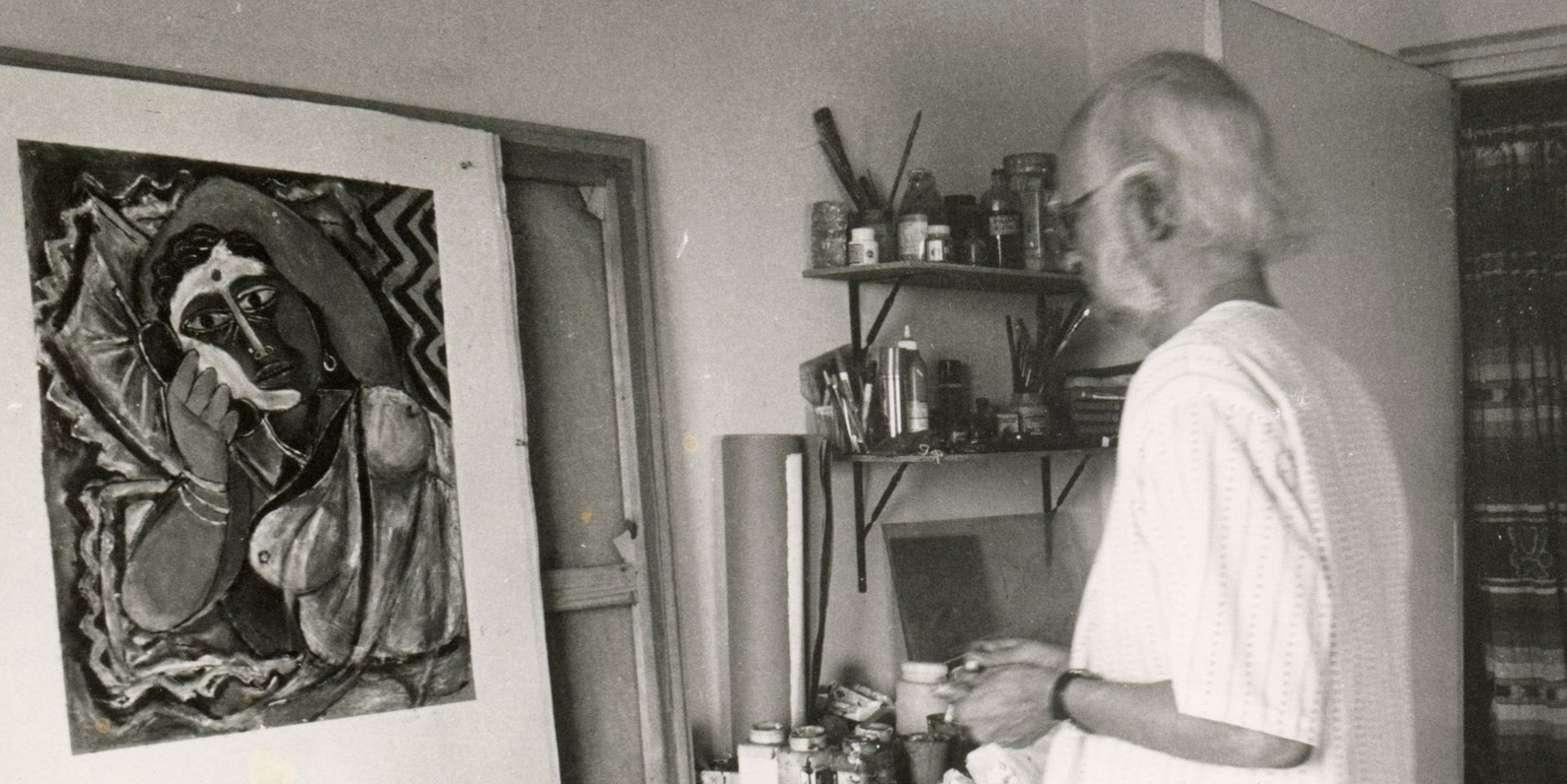

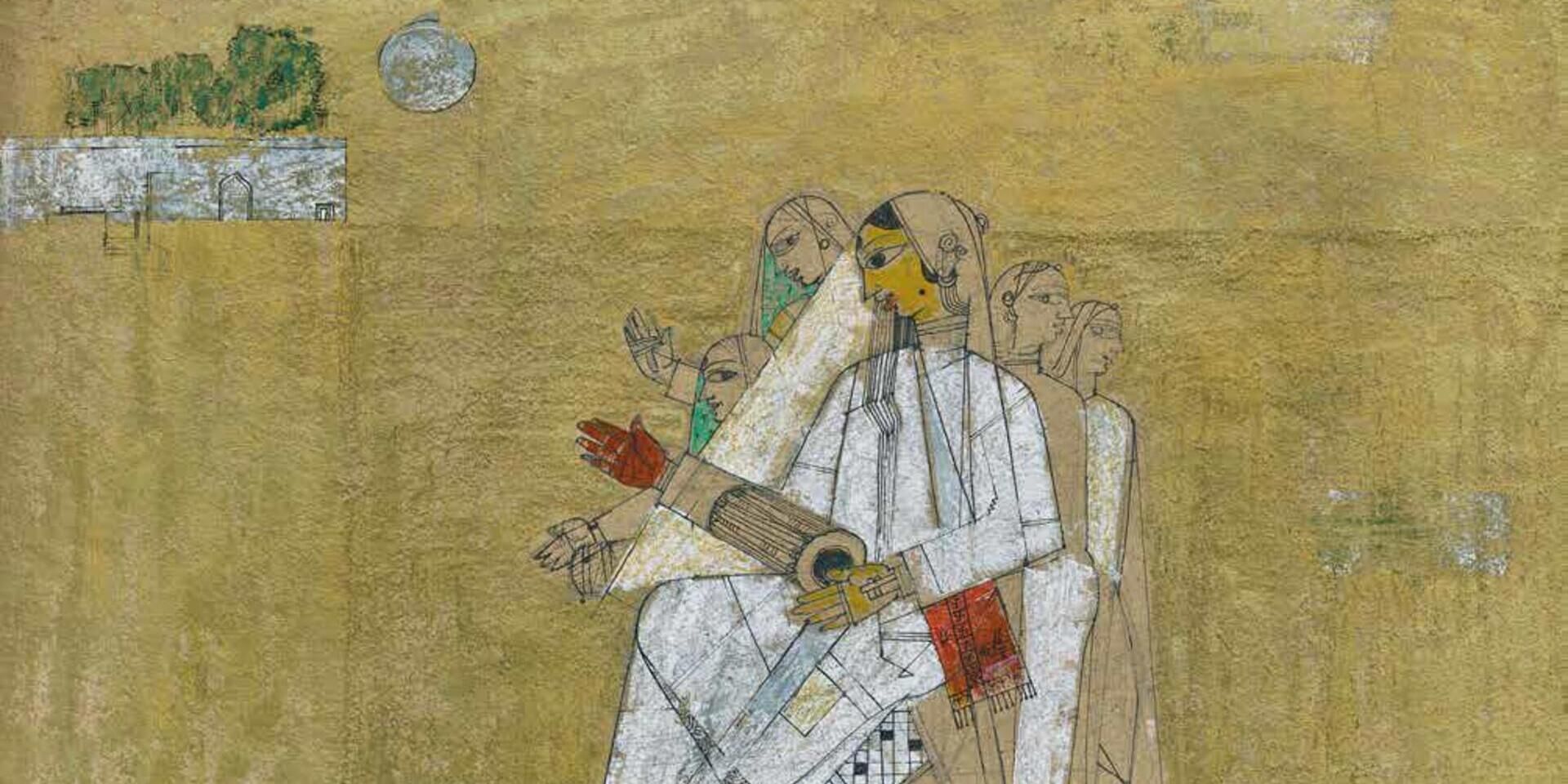

Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003) was one of India’s most original artists, mixing humour, satire and social criticism in his works with equal flair and commitment. His work expressed a deliberately uneasy confusion of American pop-art forms and Indian bazaar art—each interrogating the other about the values of ordinary, mass-produced forms of art.

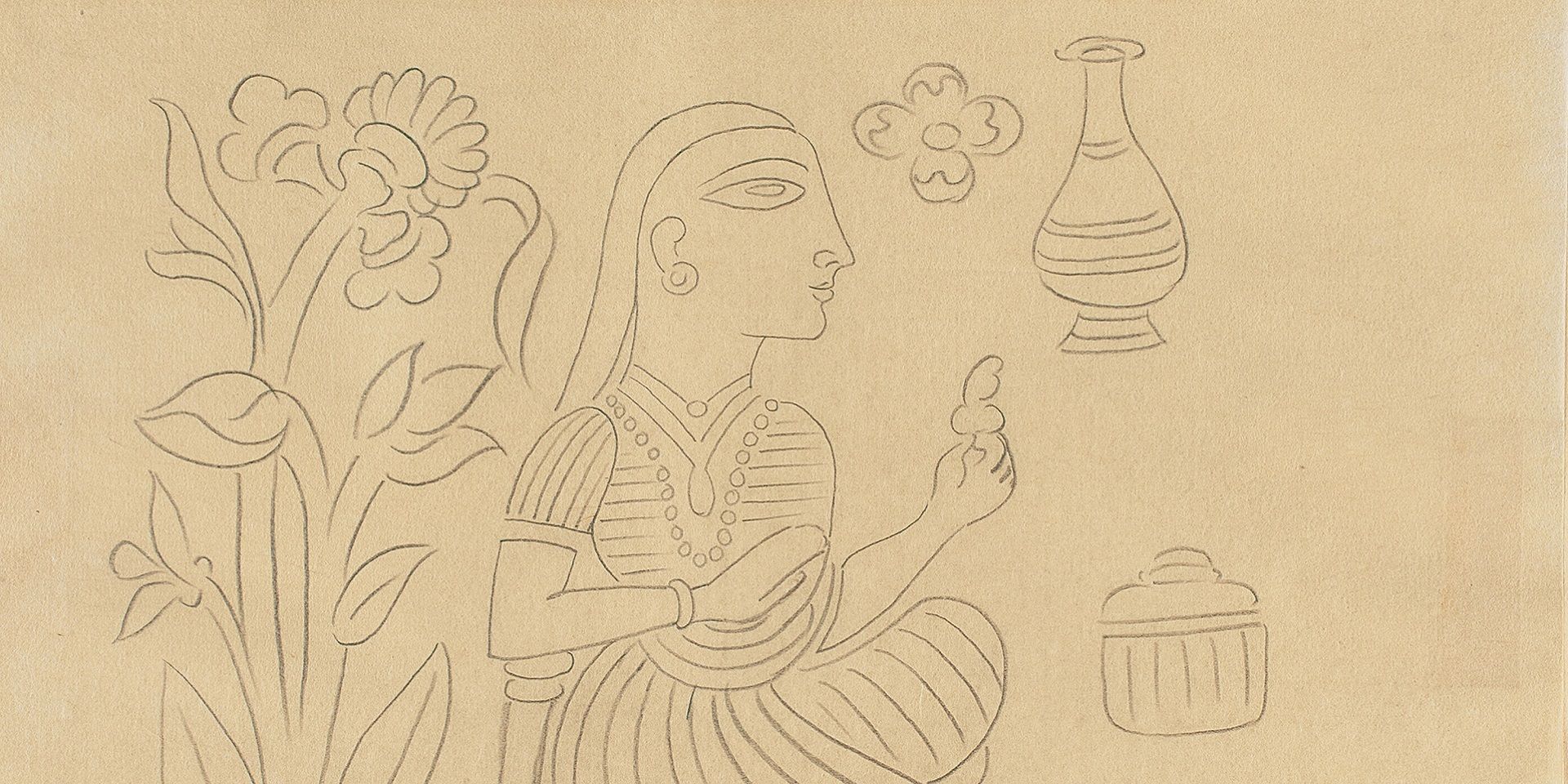

Trying to find a private language within this world of bazaar art and subverting its normative signs of cultural value-making became important preoccupations for the artist, who was fairly open about his homosexuality from the late-1980s onwards. Along with his painting career, Khakhar was invested in the literary milieu of Gujarat as well. Although he wrote stories in Gujarati occasionally, these were collected by Katha and published with English translations (by Ganesh Devy and Naushil Mehta) in 2001. Khakhar had made a limited set of fifty copies of a particular story from the collection, titled Phoren Soap (Foreign Soap), with fifteen illustrations, which is a part of DAG’s exhibition ‘India’s Rockefeller Artists: An Indo-US Cultural Saga’.

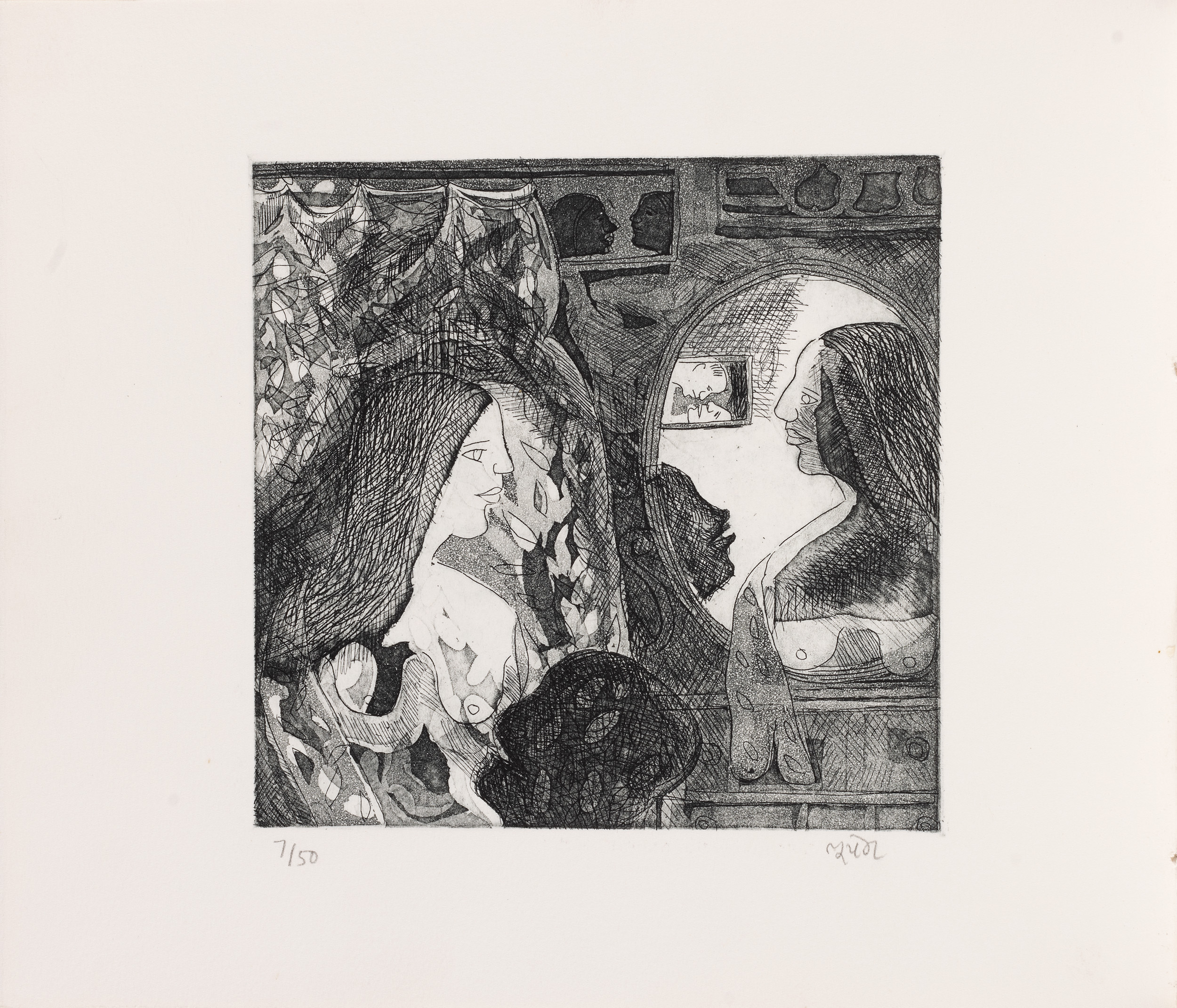

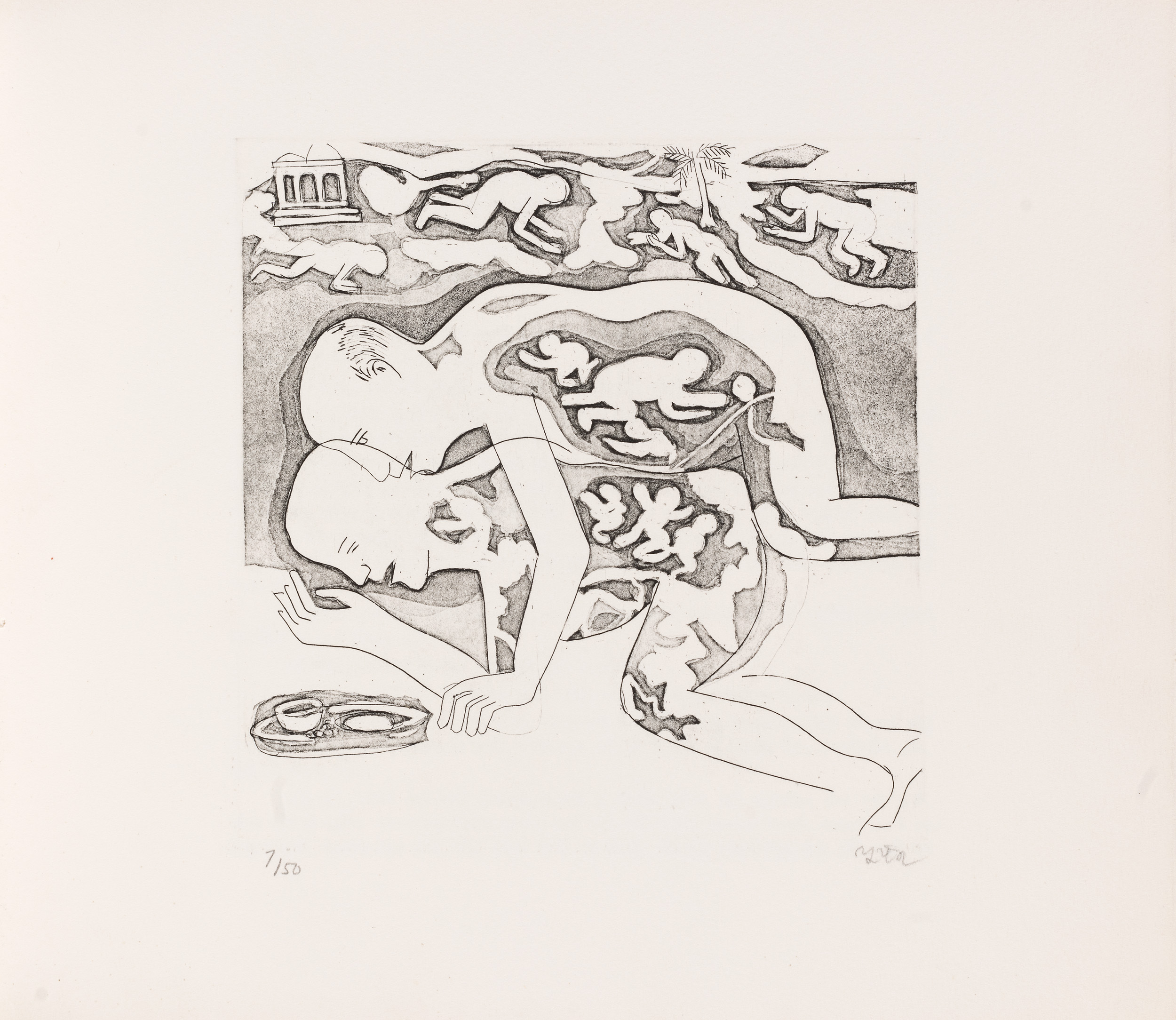

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

Khakhar begins Phoren Soap with his protagonist Jeevanlal’s first reaction to a new phoren (imitating the rough pronunciation of ‘foreign’ by the Gujarati character) soap that he is about to use for his bath; and registers his almost sensual enchantment by the aromatic object that washes his body, including his genitals, ‘of all its sins’. After his bath, when his wife Savita offers breakfast, he responds, ‘To hell with your batata-pauva. We spend a lifetime eating sev-usal and pau-bhaji and whatnot. Where does that get us in life? Now here comes this phoren soap. Just look at it. This changes our whole damned life!’.

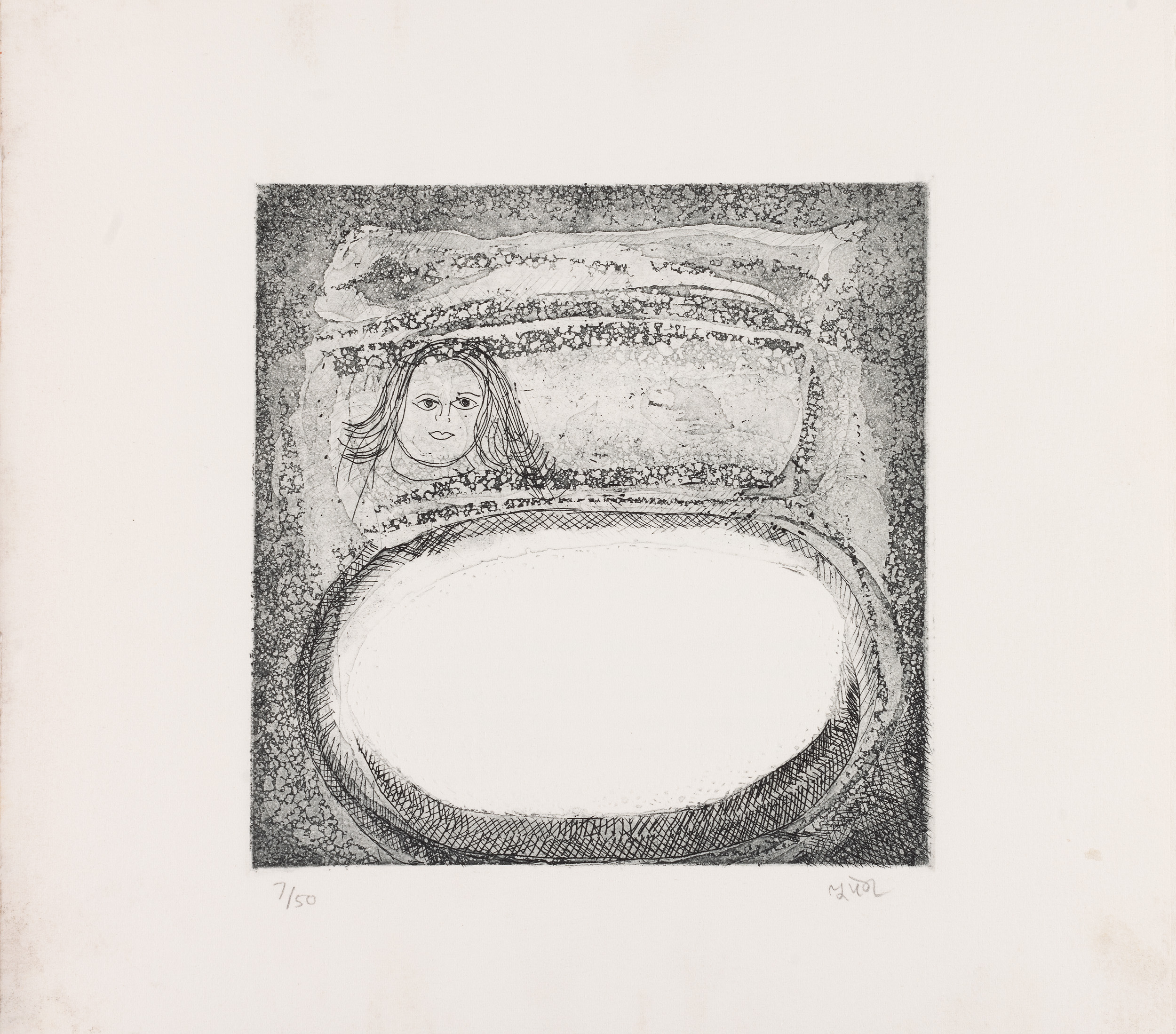

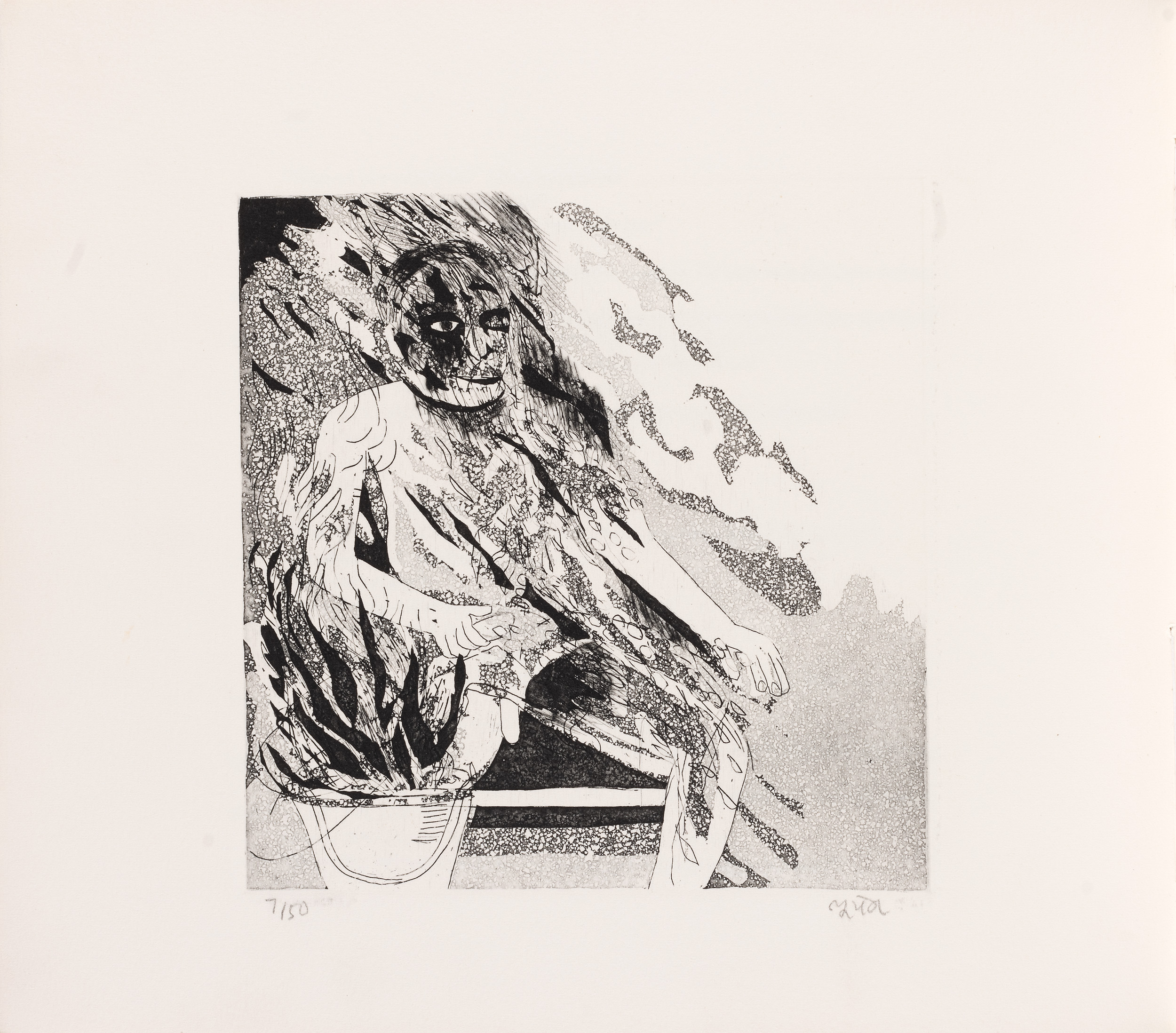

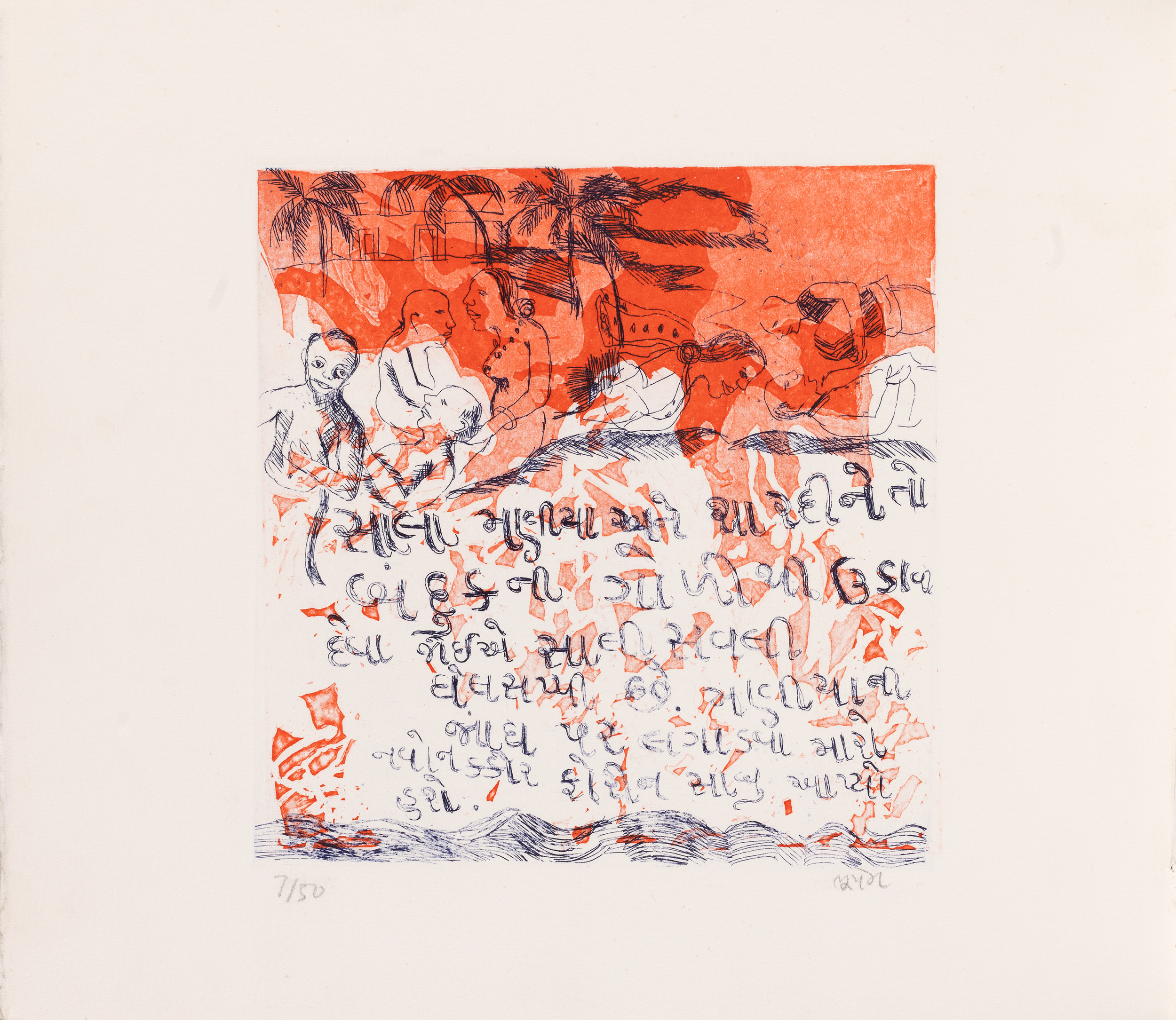

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

Khakhar’s transition from being a Chartered Accountant to an author/artist is well known. At the behest of fellow-artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, he enrolled in the masters course on Art Criticism at the Faculty of Fine Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University, in the year 1962. While in Baroda, he had a flat-mate called Jim Donovan, a British student who introduced Khakhar to Pop-art, it is this influence that he considered to be ‘the foundation of his work’.

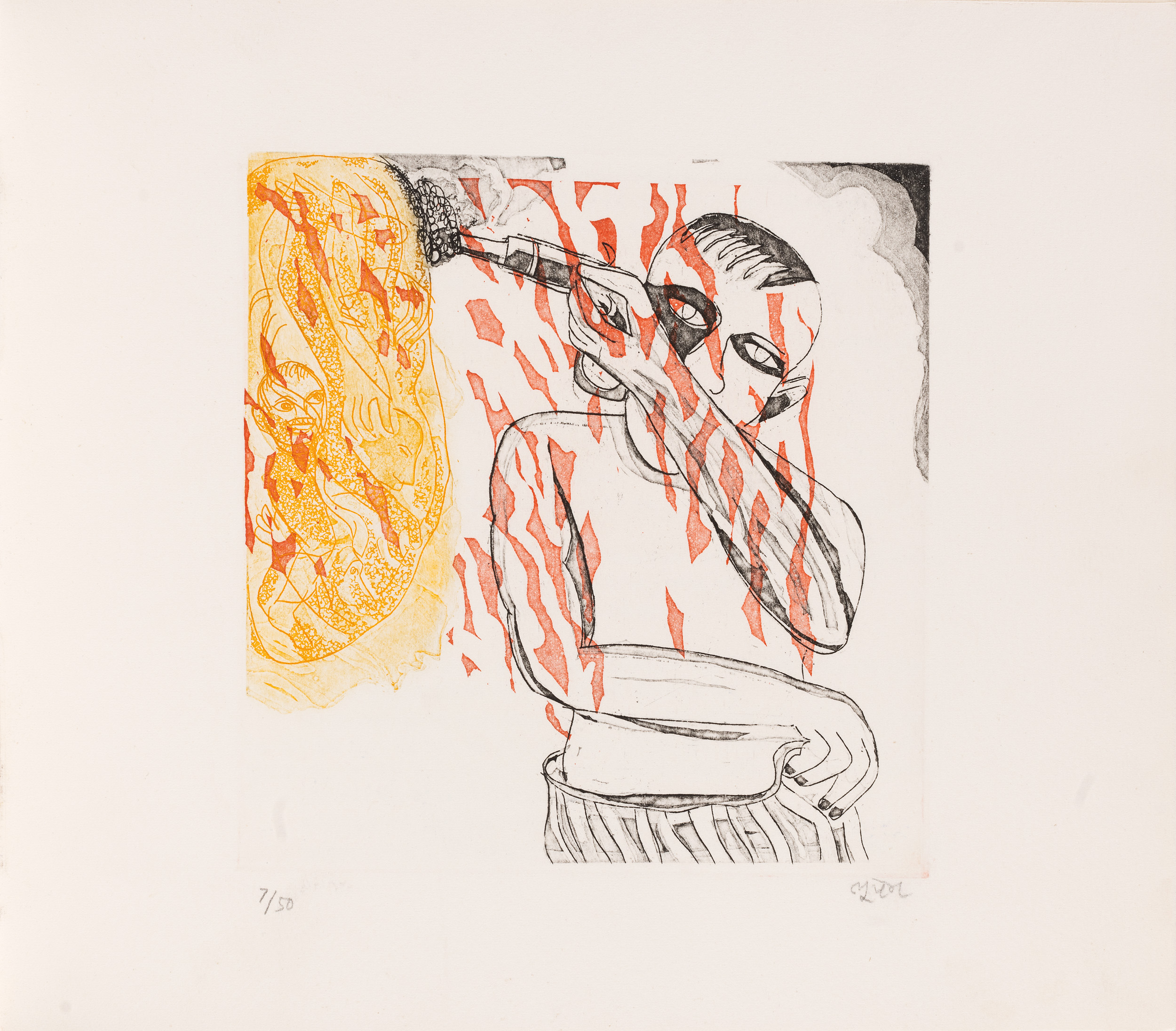

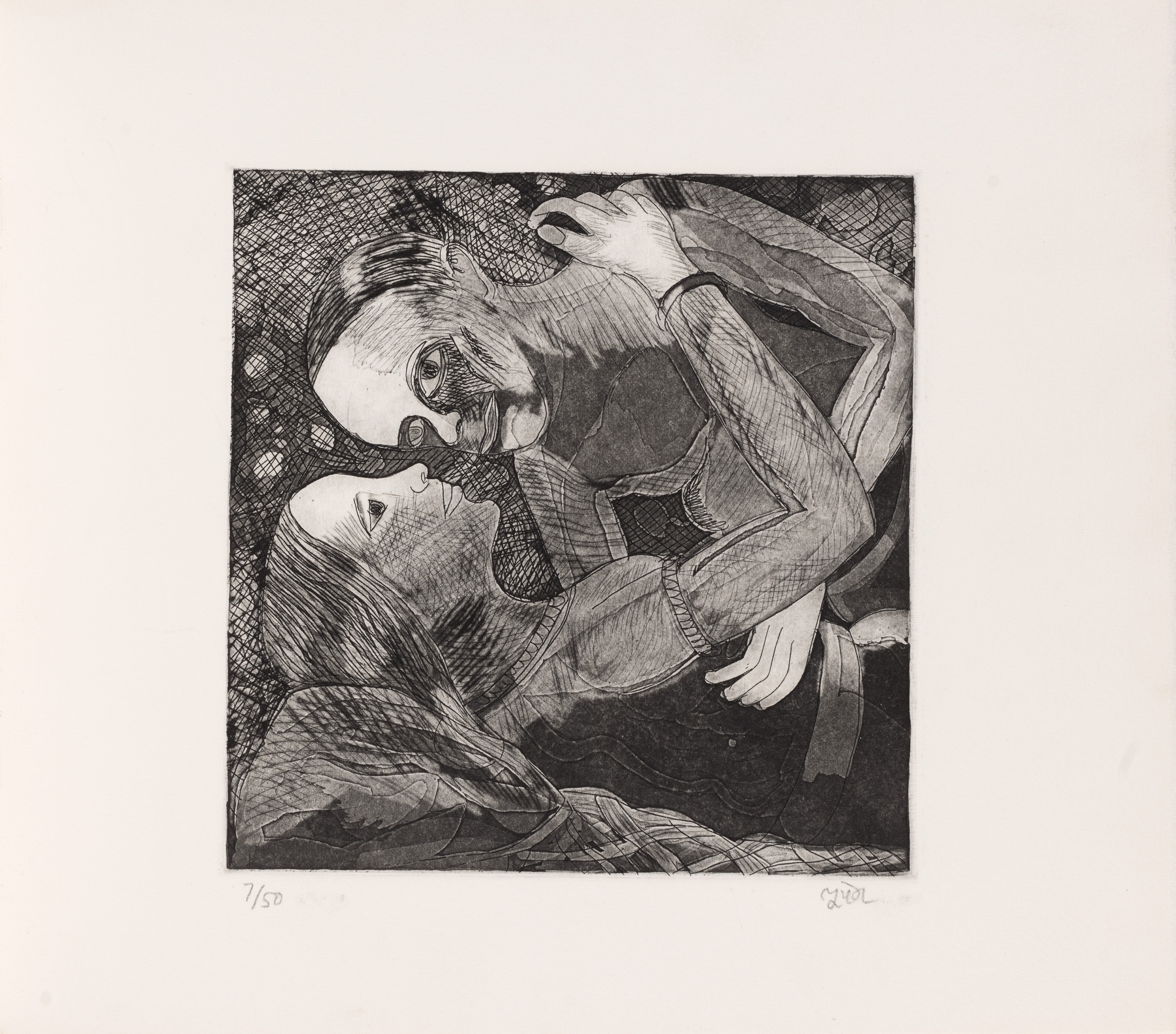

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

His collages of the mid-1960s reveal his sources, which included cheap religious prints, advertisements and popular images. What was his relationship to these prefabricated objects of mass consumption? As the art historian Devika Singh writes, ‘While including widely disseminated images, his art did not emerge in the context of the post-war consumer society that characterised British and especially American Pop art. What nurtured Khakhar’s work was not a surplus economy but that of the bazaar he so often depicted’, suggesting a spatially-located intervention into the global imagination of the market itself. His reference to food items like batata paua and sev usual is symptomatic of his intense gleaning from the popular and its multiple textures of experience and sensation, even that of the mundane every day. Moreover, these dishes are commonly available in Baroda and Mumbai (where he grew up), whose streets are populated with food stalls, which are accompanied by gaudy banners, illustrations and digitally manipulated images of the dishes, along with other regional favourites.

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

Christopher Pinney’s term ‘corpothetics’ can help us understand this world of easily exchangeable terms between sensual enjoyment and visual pleasure in Khakhar’s work. Pinney's term refers to the study of how the body is represented and understood through material culture, particularly in relation to visual and sensory experiences. He explores how aesthetic and embodied experiences shape the perception of identity and cultural practices. This term combines ‘corporeal’ (relating to the body) and ‘aesthetics’ (concerning the perception of beauty and art), emphasising the interplay between physical presence and artistic representation. In the case of religious prints, for instance, Pinney writes about the ways in which viewers engaged with those images and responded to the ones that ‘addressed their presence’ and enabled sensory engagement. Khakhar’s description of the perfume of the soap along with the image of a beautiful woman on its wrapper, suggests his ironic take on the advertiser’s attempt to enhance the desirability of the object which is merged with a certain quality of myth-making that he eventually weaves into his narrative, where various characters and their psycho-sexual obsession with the soap forms the crux of the story. Khakhar’s lifelong attempt to communicate his own personal experience of pleasure through the ‘simplified’ forms of bazaar art particularly acquires value in the context of the corpothetic. But what explains this obsession around a ‘foreign’ soap?

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

The liberalisation of the Indian economy, initiated in 1991, marked a transformative shift from a state-controlled economic model to a market-oriented one. Faced with a balance of payments crisis, India undertook sweeping reforms, including deregulation, privatisation, and the opening up of markets to foreign investment. These changes aimed to stimulate economic growth, increase efficiency, and integrate India into the global economy. The liberalisation policy led to rapid economic expansion, increased foreign direct investment, and a burgeoning middle class. Khakhar published Phoren Soap in 1990 (reissued as a distinct artist’s book, with the text in Gujarati and English, along with his own illustrations in 1998)—right around the time of liberalisation, when obsession with foreign commodities—forbidden, or difficult to acquire for many decades in India due to economic regulations—had become a national pastime. The foreign not only provoked curiosity, but promised a fulfilment of hidden desires, making the foreign soap a slippery signifier of all that was forbidden but arousing, even to the point of threatening one’s ‘local’ identity. It becomes twinned with the idea of ‘risk’ that also underwrites the condition of queer love in heteronormative societies, within which Khakhar lived in India.

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

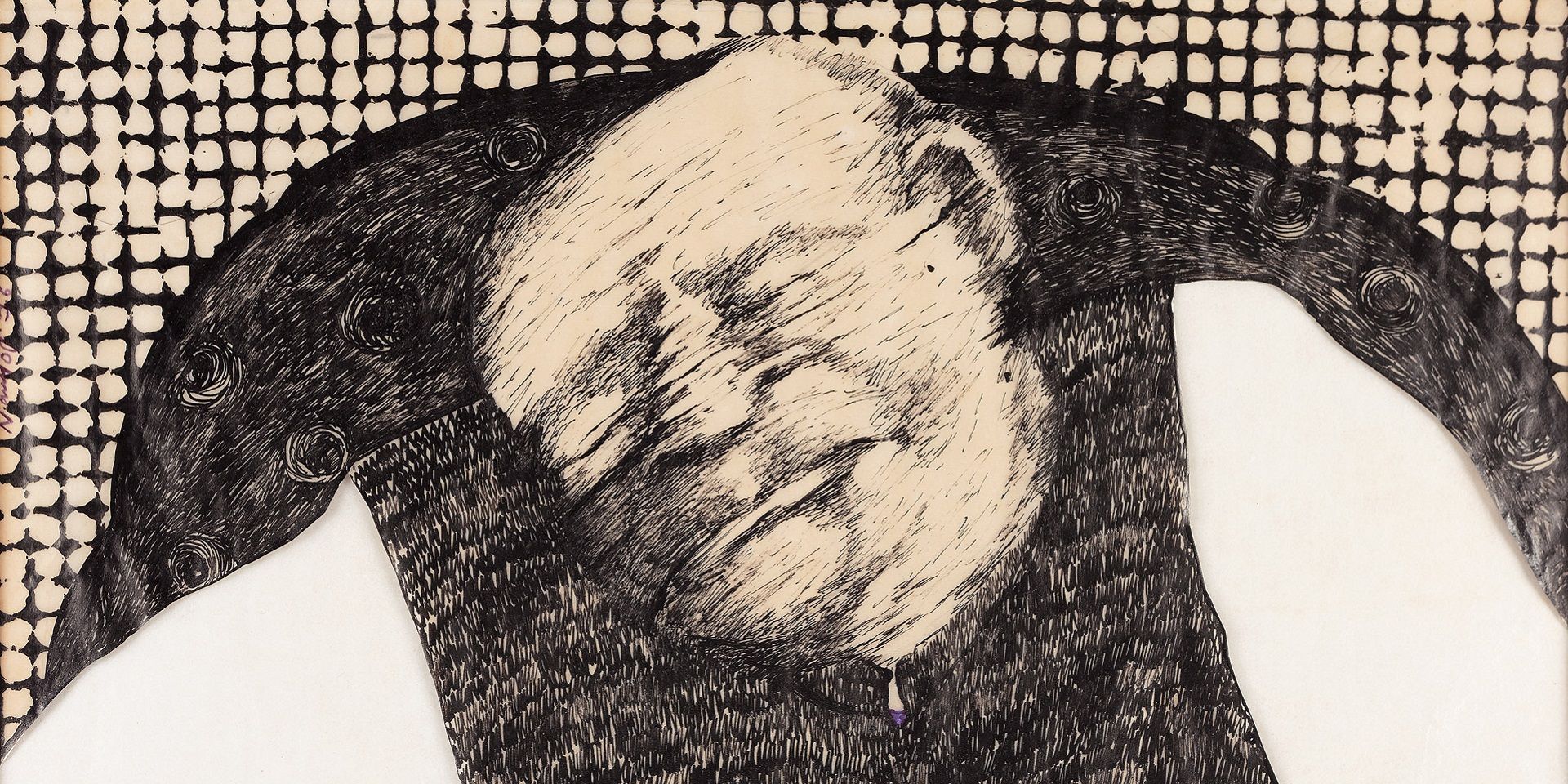

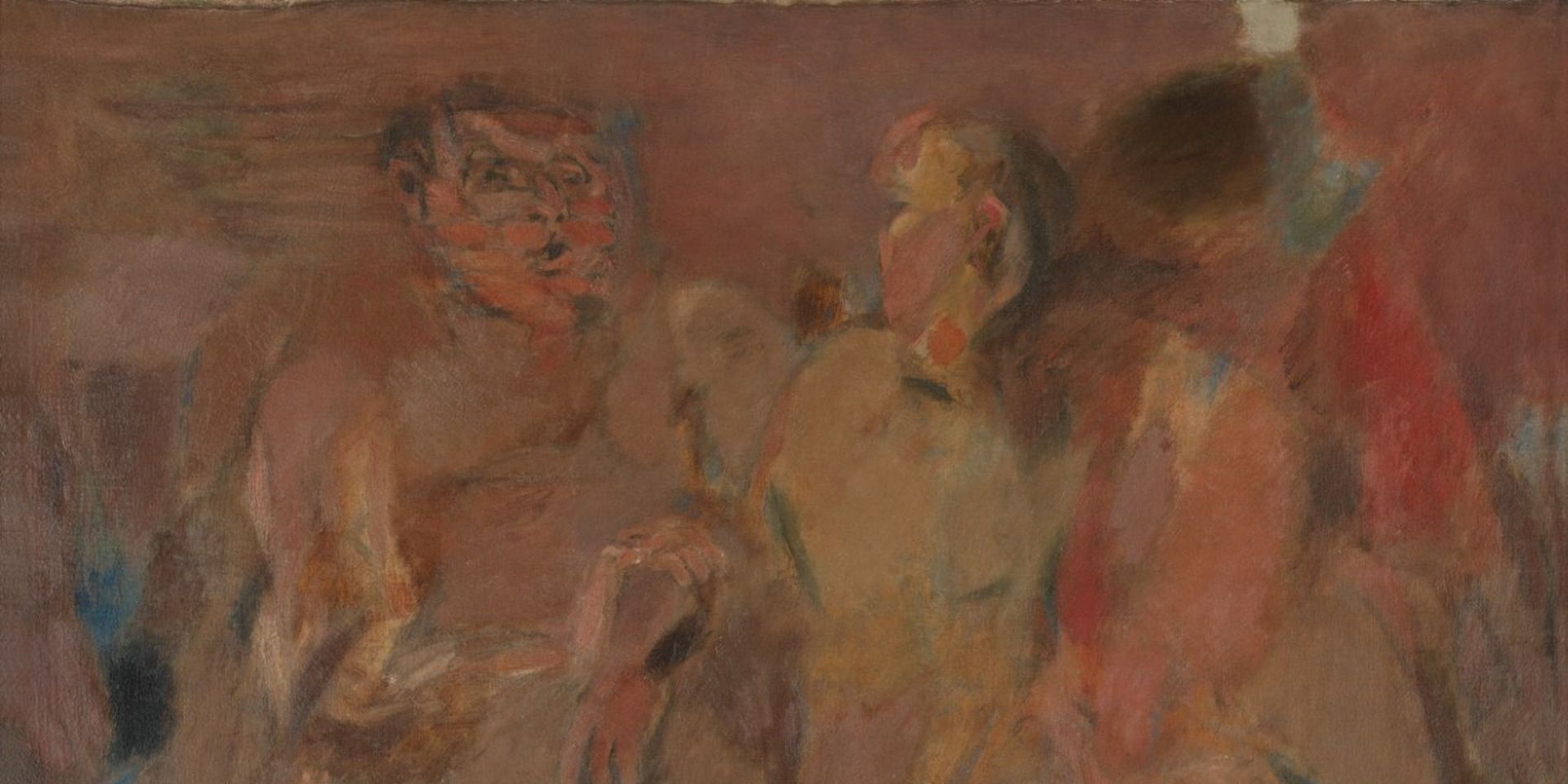

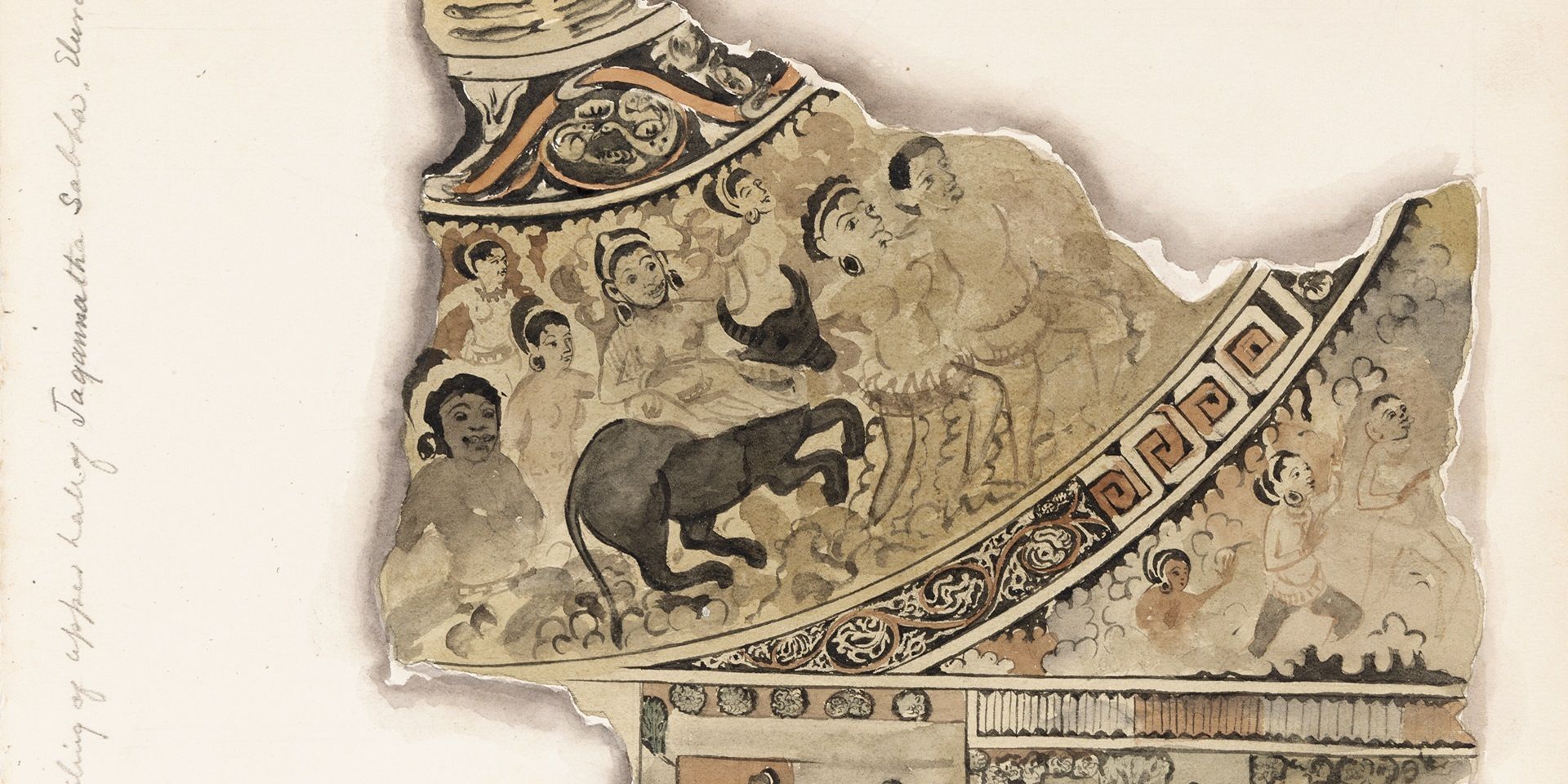

Khakhar’s inclination towards illustrated stories can be drawn back to the time when he worked with Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and Geeta Kapur on the Baroda-based experimental magazine Vrishchik (‘Scorpion’), where he contributed ‘visual notes’ for the inaugural issue, which included ‘advertisements for soap, posters of celebrities and religious ephemera’. The many etchings that illustrate the text of Phoren Soap, reveal a variety of episodes that the artist consciously decided to illustrate. Some of them give shape to the private, masturbatory fantasies of Jeevanlal and his neighbour Manilal, while others show larger thematic orientations. Although Khakhar’s most celebrated paintings and prints tend to depict homosexual men and their covert explorations of pleasure, he made a few erotic illustrations of heterosexual couples for Phoren Soap as well. However, there is also an illustration which shows two men embracing each other, with children’s forms included within and outside their bodies, as if suggesting the ‘unnatural’ phenomenon of male pregnancy. The story is a witty example of Khakhar’s take on the hypocrisy of heteronormative couplings, which is regularly disrupted by the queer intrusions of objects and irrepressible desires. Instead of the depiction of a gay encounter or narrative, the gaze turns inwards—directed towards the mechanics of Indian social (and sexual) norms. As Geeta Kapur writes, ‘It is as if with the help of the ‘saint-pervert’ (Jean Genet) that Khakhar now celebrates the moment of transition from sodomy, in (Michel) Foucault’s words, into a ‘kind of interior androgyny, a hermaphrodism of the soul.’

|

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG |

|

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG |

The story takes an intriguing turn when the protagonist, Jeevanlal, loses his temper over the sudden disappearance of the revered object, the phoren soap. This loss leads him to seek atonement for the sin he feels was prompted by his desire for the soap. The act of atonement seems to address the sexual urges provoked by the soap itself, revealing a humorous take on Hindu mythological themes, particularly the concept of 'brahmacharya'—the struggle between self-discipline and indulgence. A similar theme appears in his 1995 work, An Old Man from Vasad Who Had Five Penises Suffered from Runny Nose, where the central figure, displaying his five penises, embodies irrepressible sexuality, reflected in his chronic runny nose. The art historian Karin Zitzewitz notes that the artist sees the image as a parody of yogic practices that advocate semen retention, highlighting the impracticality of such discipline for someone so ‘blessed’. This commentary shows his ongoing interest in humorously engaging with elevated religious concepts of atonement and guilt, a theme he continues to explore after finishing the painting.

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

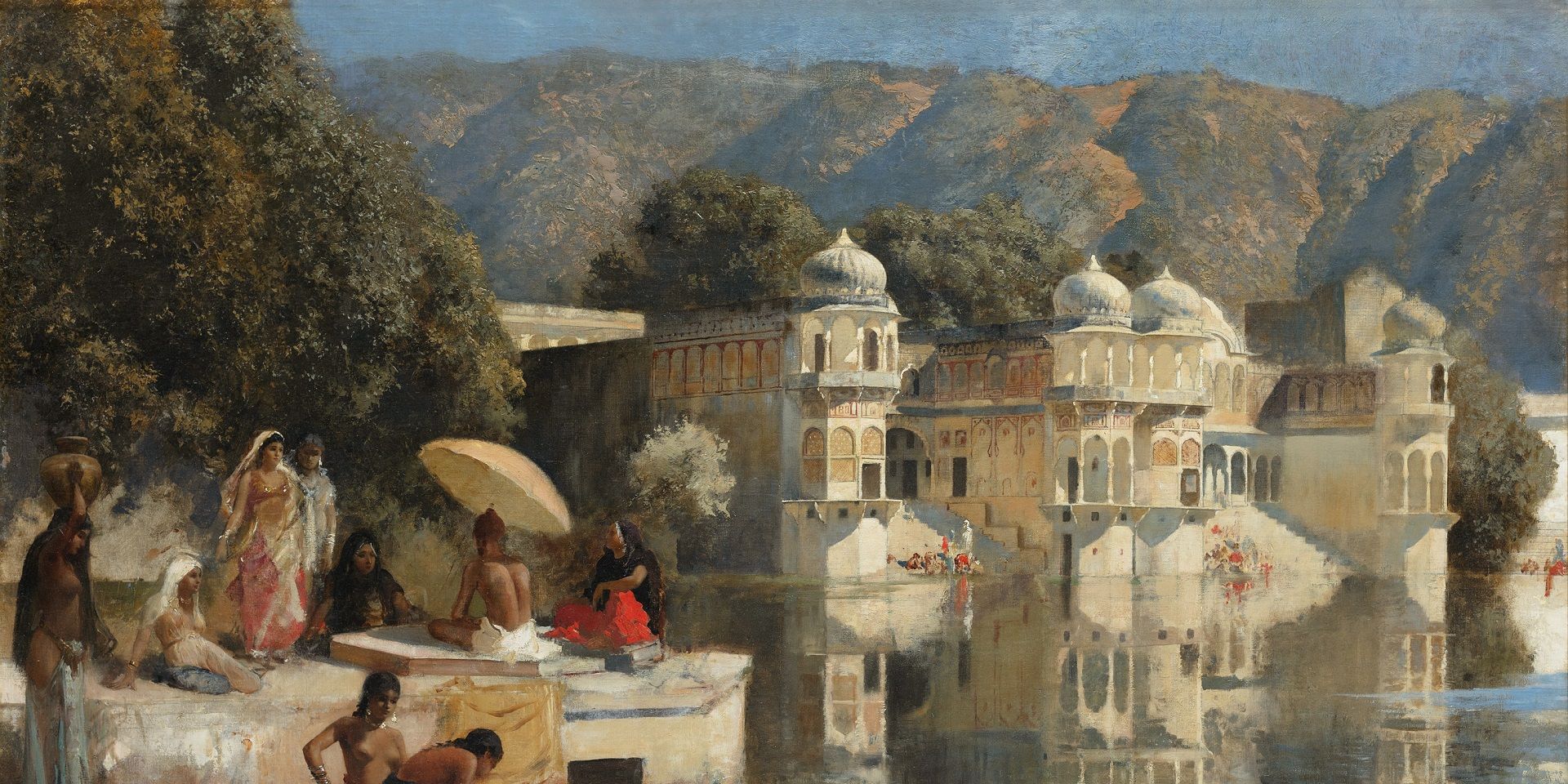

His observations of the local and experimentation with eroticism expand out of the Indian context owing to his travels abroad, where the ‘foreign’ is said to originate. He visited England in 1979, where he was invited to teach for six months at the Bath Academy of Art. Singh quotes Khakhar to write, ‘After my visit to England in 1979, I saw that homosexuality was accepted. People lived together’. He also travelled extensively to Italy, U. S. S. R., and Yugoslavia on a cultural exchange programme provided by the Indian government. Khakhar also received the Rockefeller Foundation Grant and visited New York in 1985. Some of his iconic works including Banaras (1982) and Yayati (1987) were made in between these various sojourns. The world of the foreign, which signifies risk, danger and sensual pleasure in his story, became slightly more familiar for Khakhar following these years—as it did for millions of Indians around the same period.

As writers like Timothy Hyman have suggested, the decade of the 1980s also marks the period when Khakhar came out of the closet; and subsequently, ‘(h)e found himself, once again, speaking for a class and a world hitherto unregarded, unrecorded. The most striking change was that his art became explicitly confessional, as often as not including a self-portrayal—sometimes approaching life-size, and frequently naked.’ His later works that dabble with various representations of the erotic and the public, however, can still be traced back to Phoren Soap, where he chose particularly erotic excerpts from the narrative and transformed them almost into symbolic representations of people exploring their own bodies and fantasies, while also confronting the dangers associated with them. As his private obsessions became public preoccupation, Khakhar’s ironic narrative of the foreign soap as a suspicious agent of subversion became a symbolic story for the whole nation.

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

Finally, as suggested above, it is worth noting again that these images do not always directly illustrate the story but let us peek into the clandestine themes suggested by it. Through such larger thematic interventions, the socially normative barrier between the private and the public, which forms a harder, more impassable, kind of boundary for queer individuals and artists like Khakhar, is wittily dismantled in his great and memorable work.

Bhupen Khakhar, Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati), Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50. Collection: DAG

Endnotes

Bata pauva: A popular Indian dish usually consumed for breakfast, consisting of flattened rice (pauva or poha) and potatoes (batata)

Sev Usal: Another popular and flavourful street food dish from western India. It consists of a spicy, tangy curry made from dried peas or beans (usal) and is topped with crispy sev, a type of fried gram flour noodle

Pau-bhaji: A well-known Indian street food dish from Maharashtra and Gujarat consisting of a spicy, mashed vegetable curry (bhaji) served with buttered, toasted bread rolls (pav, or pau). The dish is garnished with onions, coriander, lemon, and often a dollop of butter, offering a flavourful and hearty combination of textures and spices.

related articles

Essays on Art

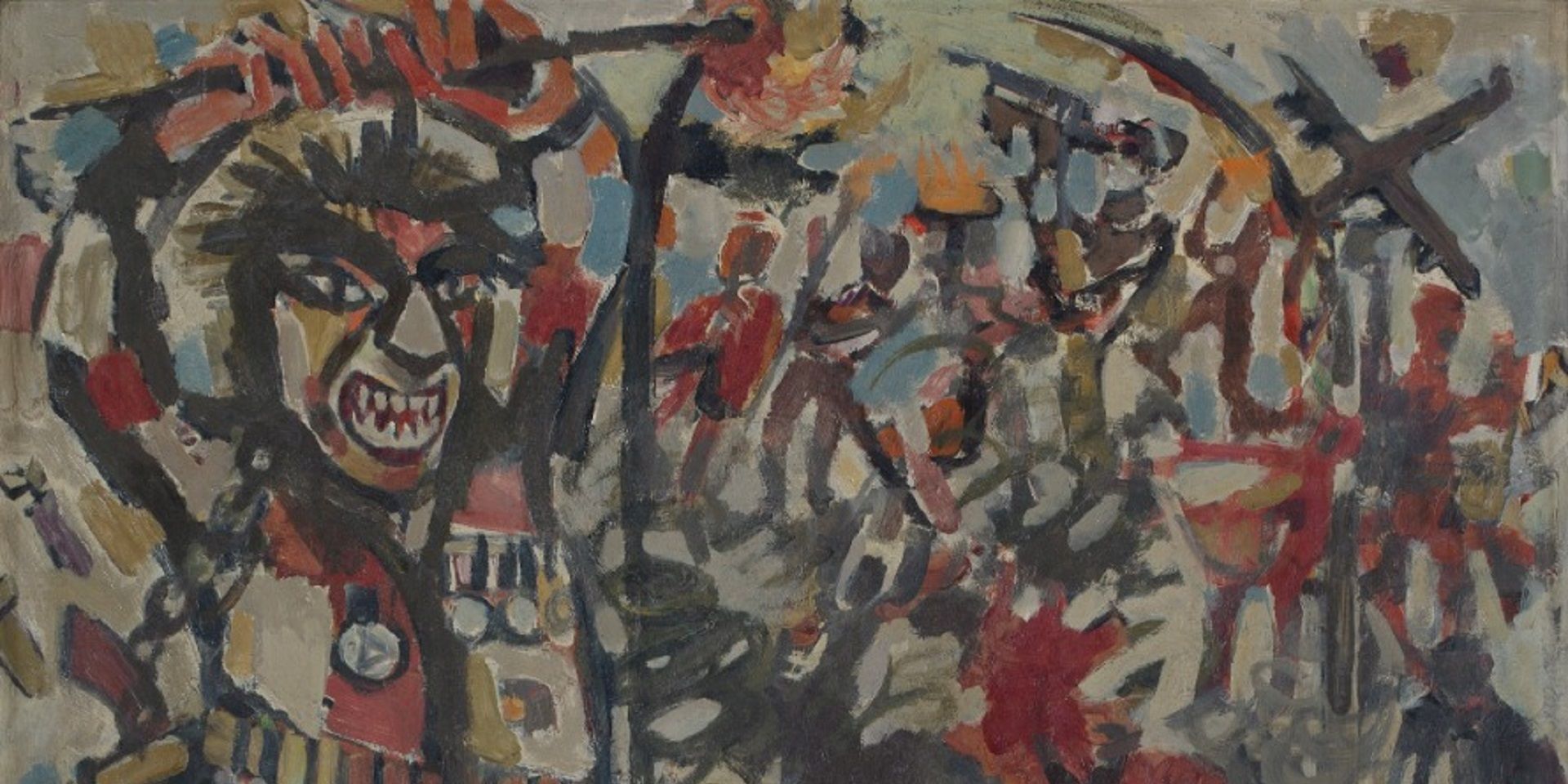

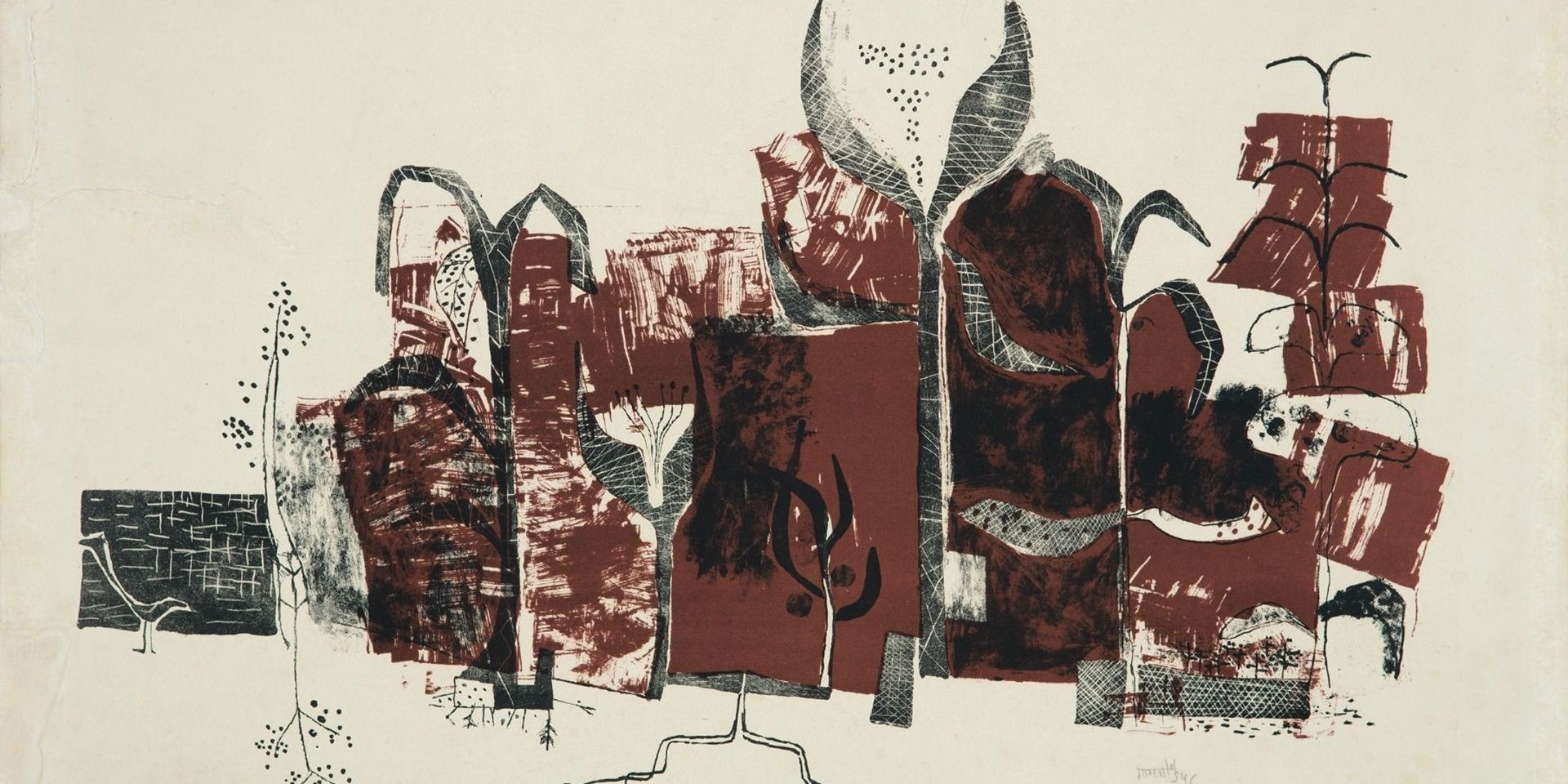

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

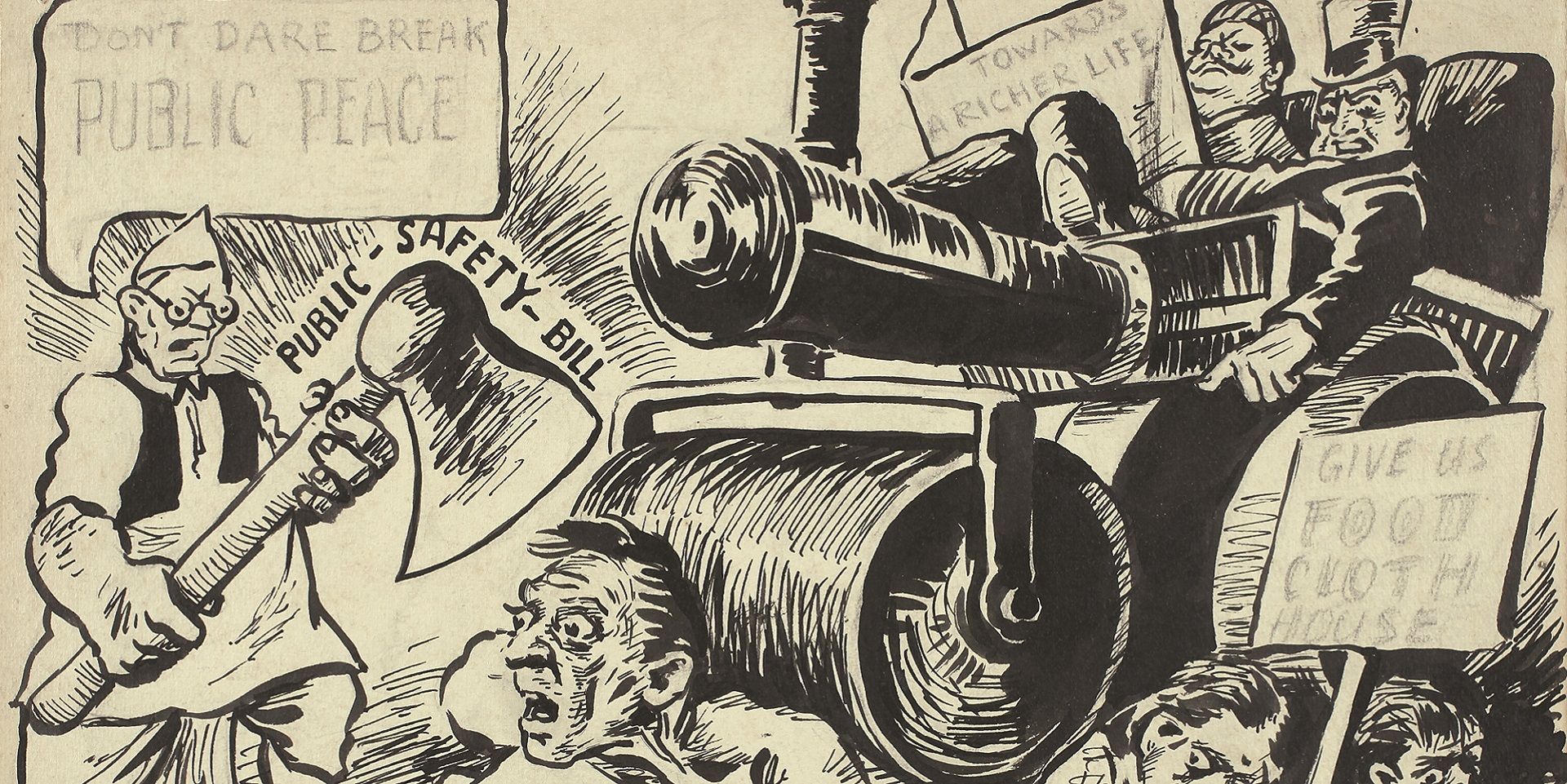

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

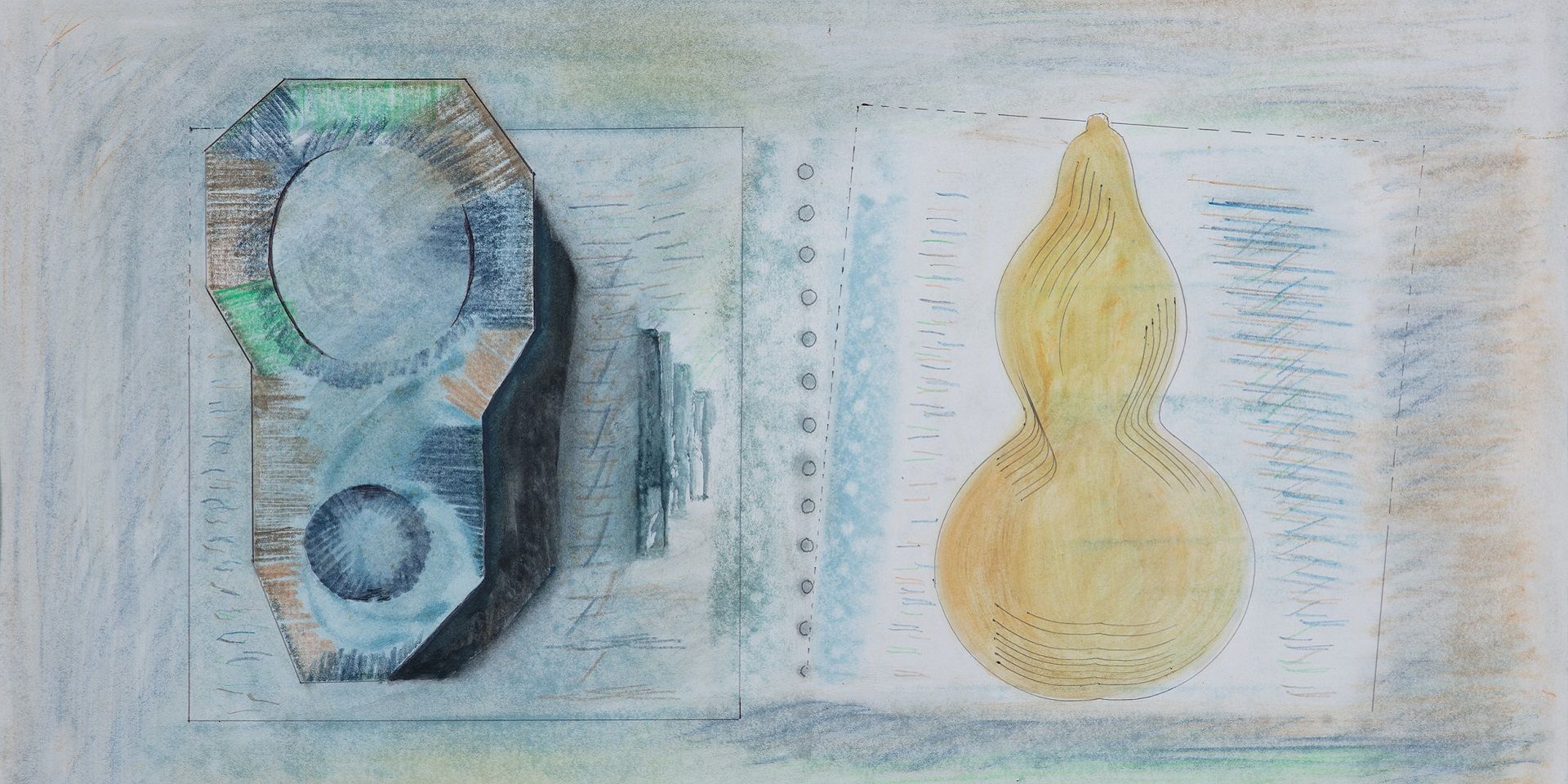

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

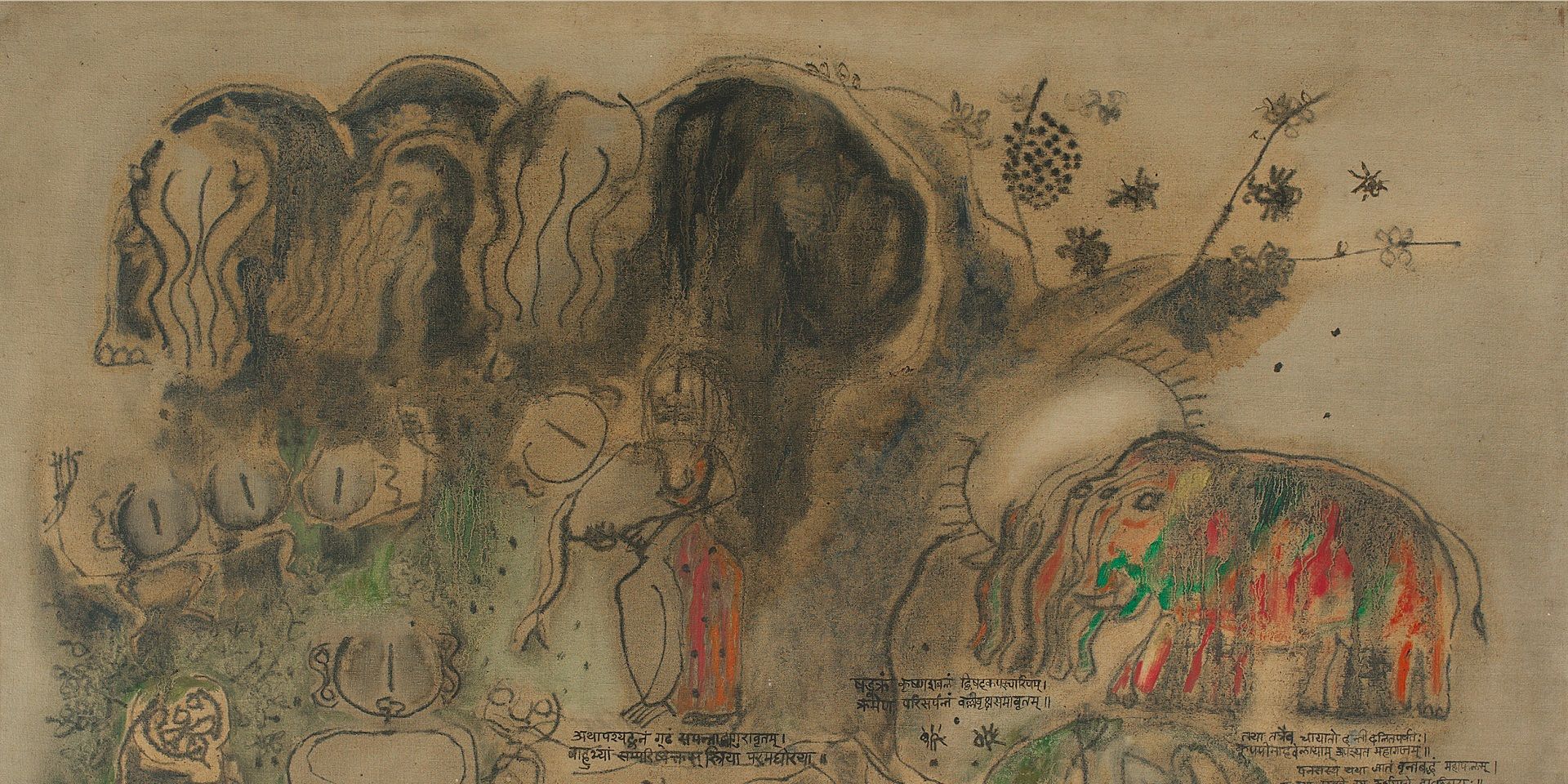

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024