The City of Lakes: Edwin L. Weeks in Udaipur

The City of Lakes: Edwin L. Weeks in Udaipur

The City of Lakes: Edwin L. Weeks in Udaipur

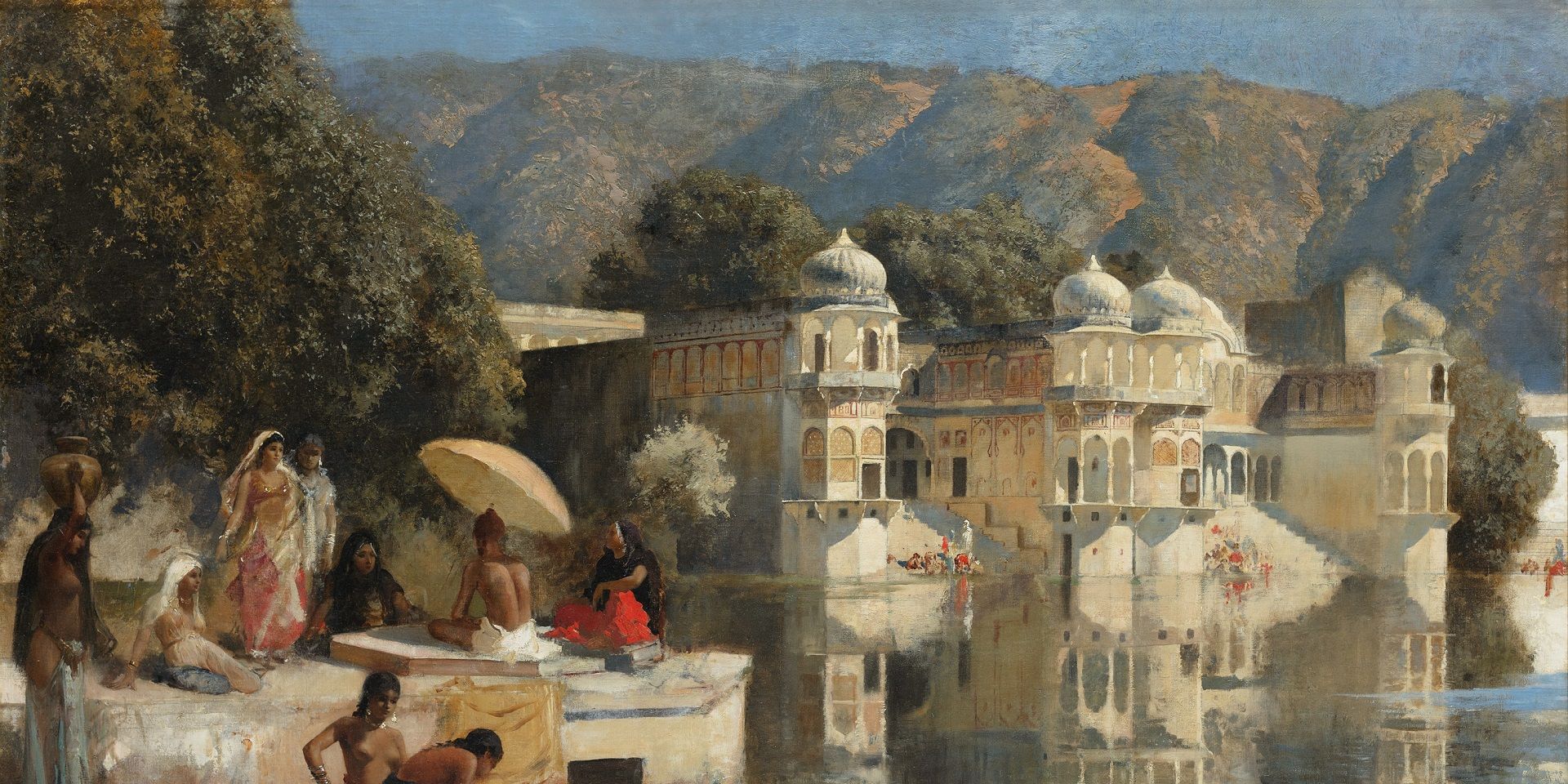

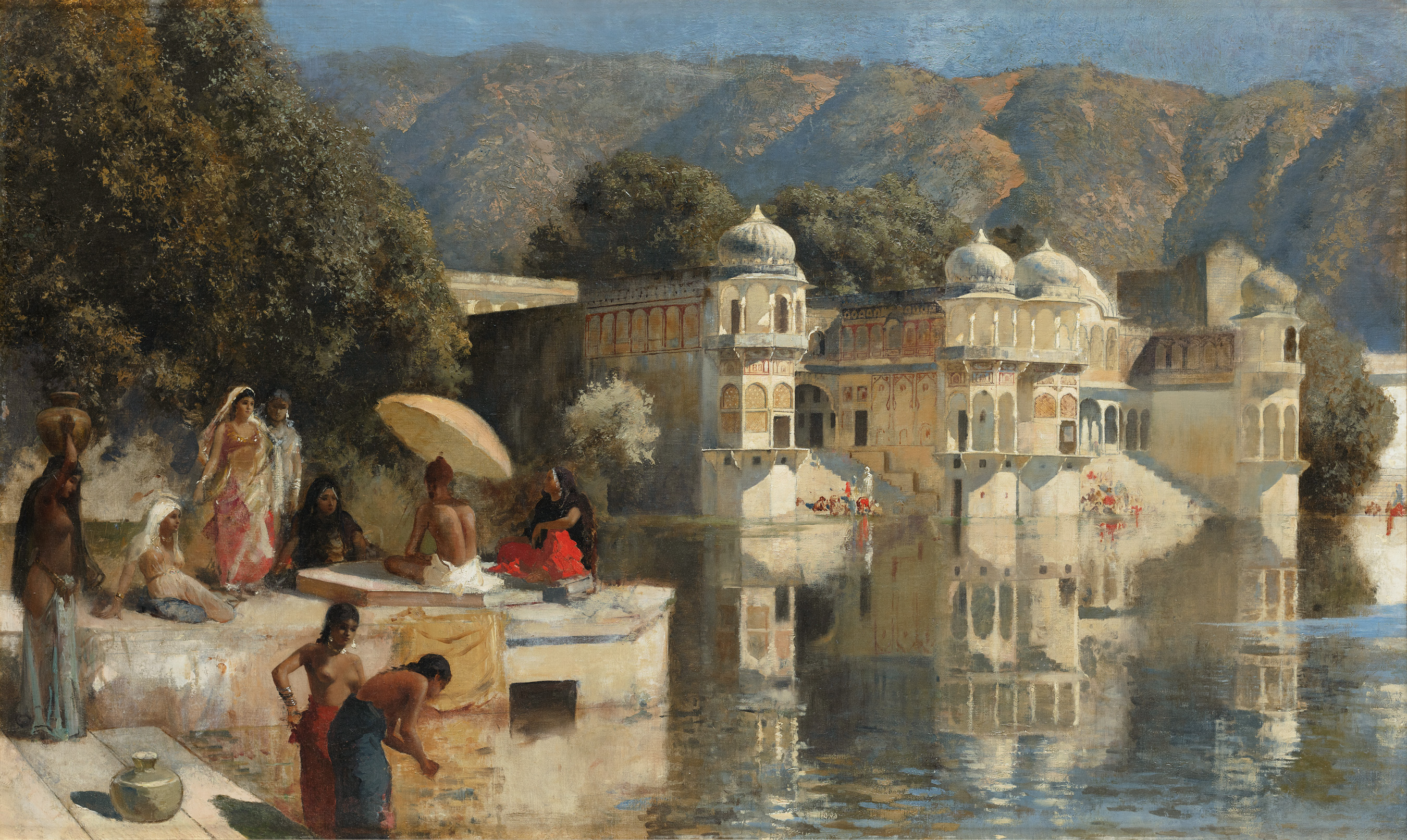

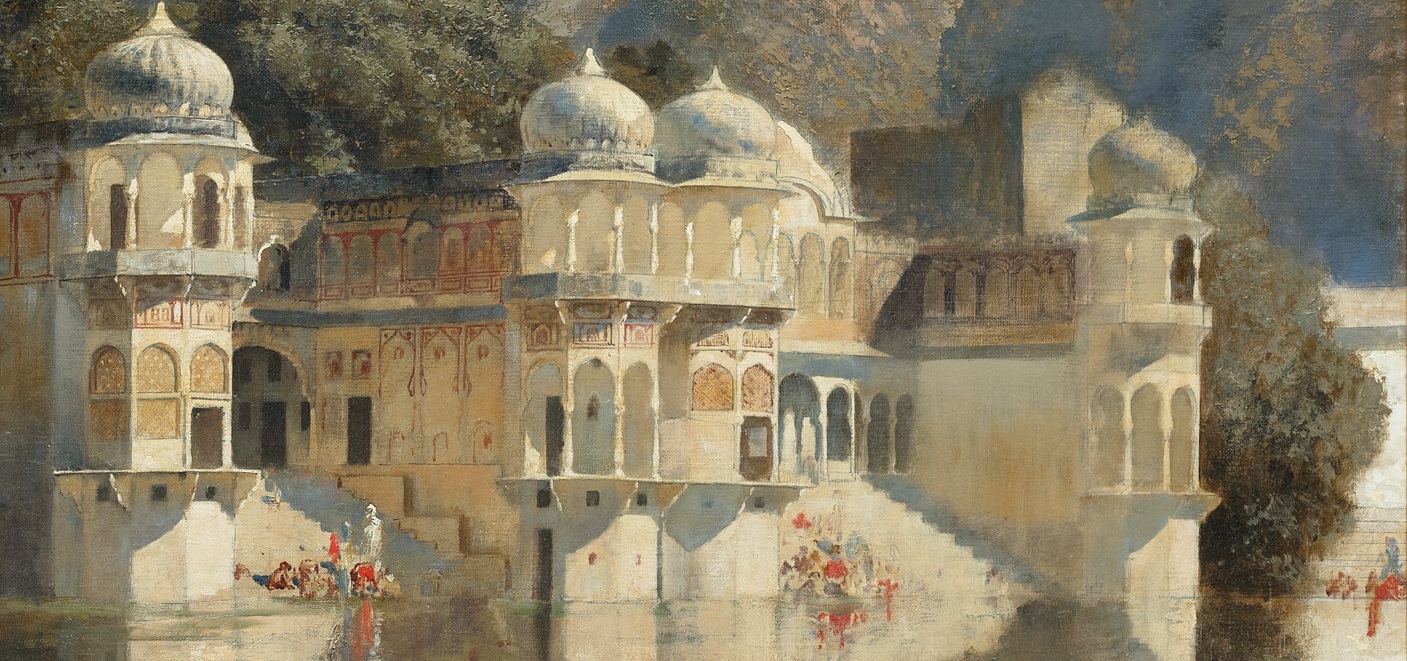

Edwin Lord Weeks, The Lake at Oodeypore, India (detail), Oil on canvas pasted on Masonite board, c. 1893, 30.0 x 50.0 in. Collection: DAG

In this article we will be taking a closer look at the artist Edwin Lord Weeks' depiction of Udaipur, along with an extract from his travel writing.

In the nineteenth century, Udaipur, part of the princely state of Mewar, navigated a complex political landscape. Ruled by the Maharana, it maintained relative stability amidst shifting powers. The region aligned cautiously with the British East India Company, signing a treaty in 1832 that secured protection in exchange for limited British oversight. During the 1857 Rebellion, Udaipur remained loyal to the British, contributing troops. Later in the century, as British influence grew, administrative reforms were introduced, altering governance and integrating the state into the British Raj. This period marked a gradual transformation from princely autonomy to greater colonial influence. Along with these changes in its socio-political landscape, artistic representations of the city, founded in the sixteenth century, also underwent a shift.

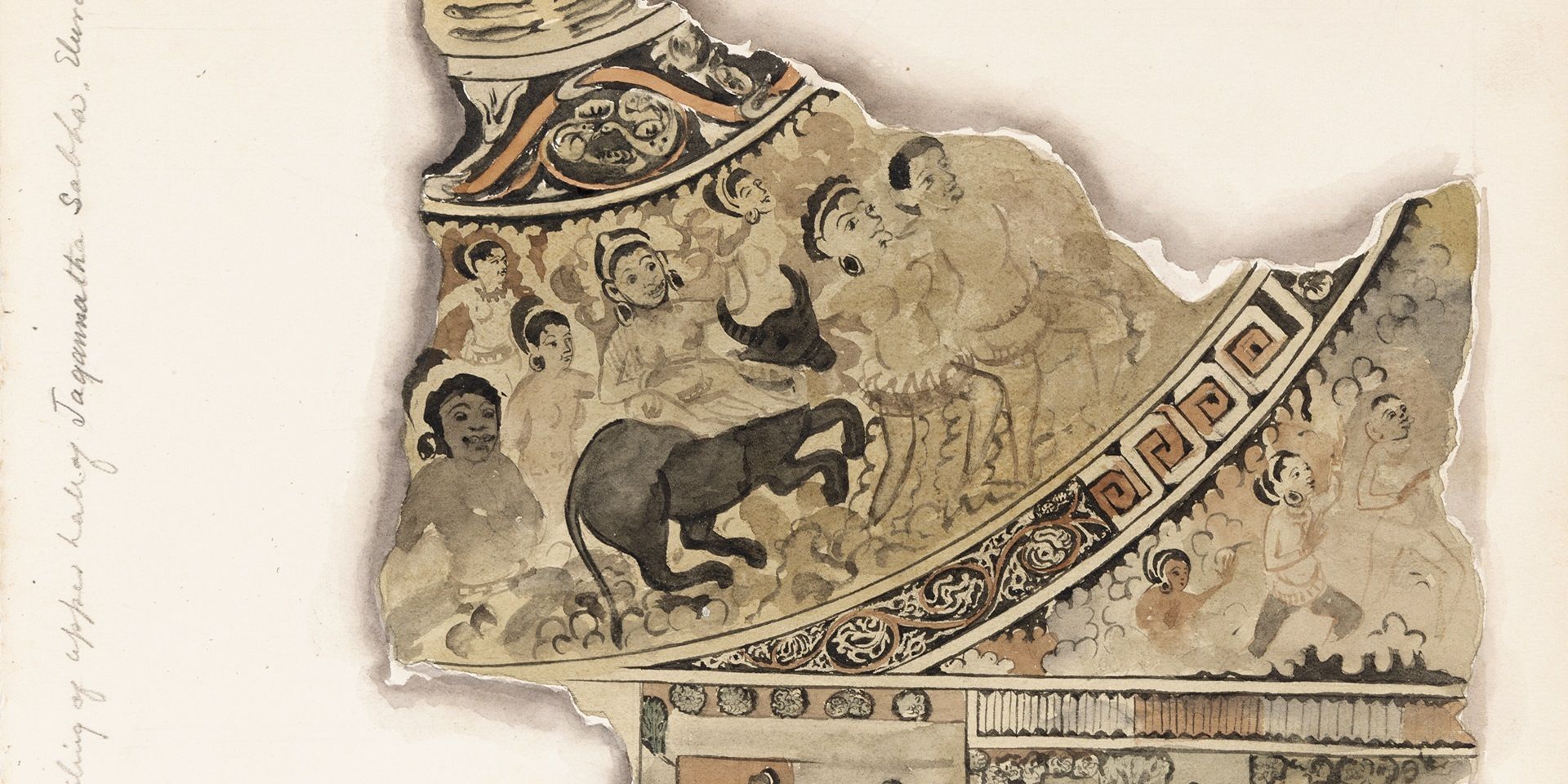

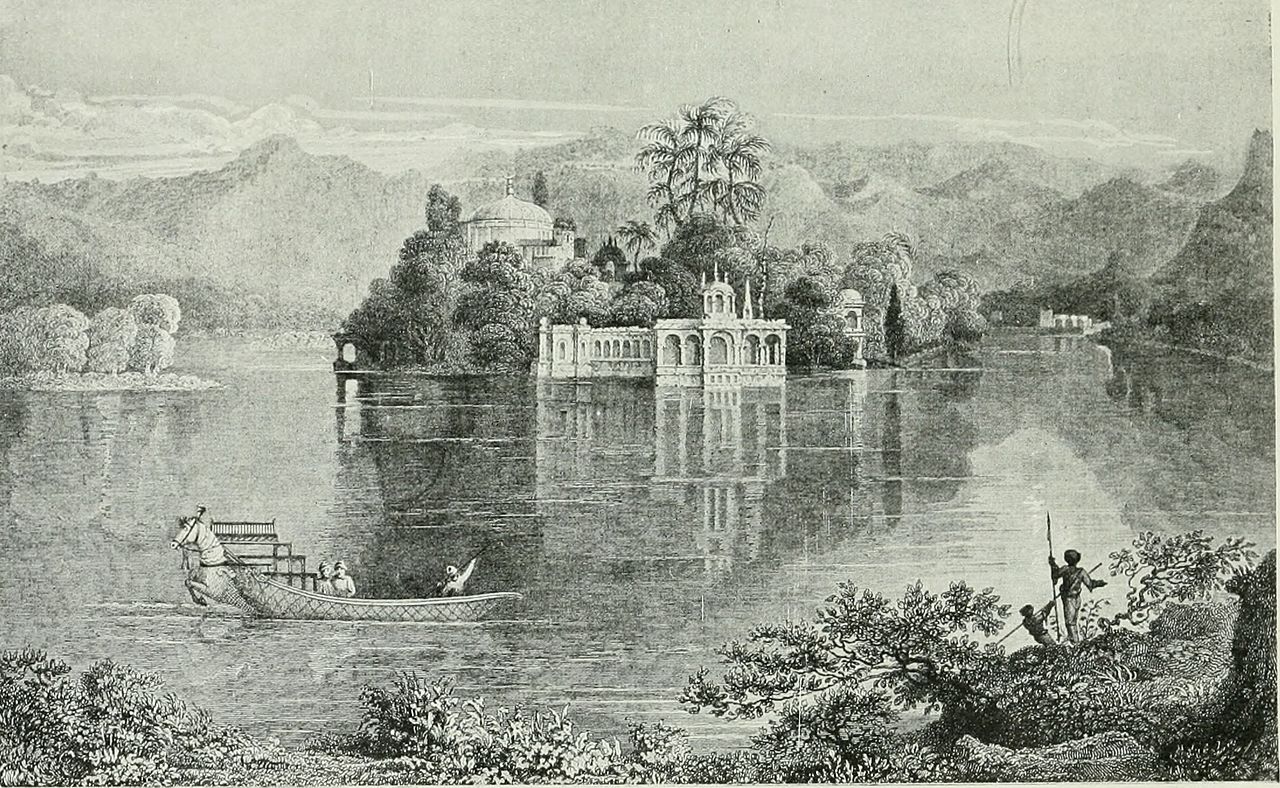

From James Tod's Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan, or The central and western Rajput states of India. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

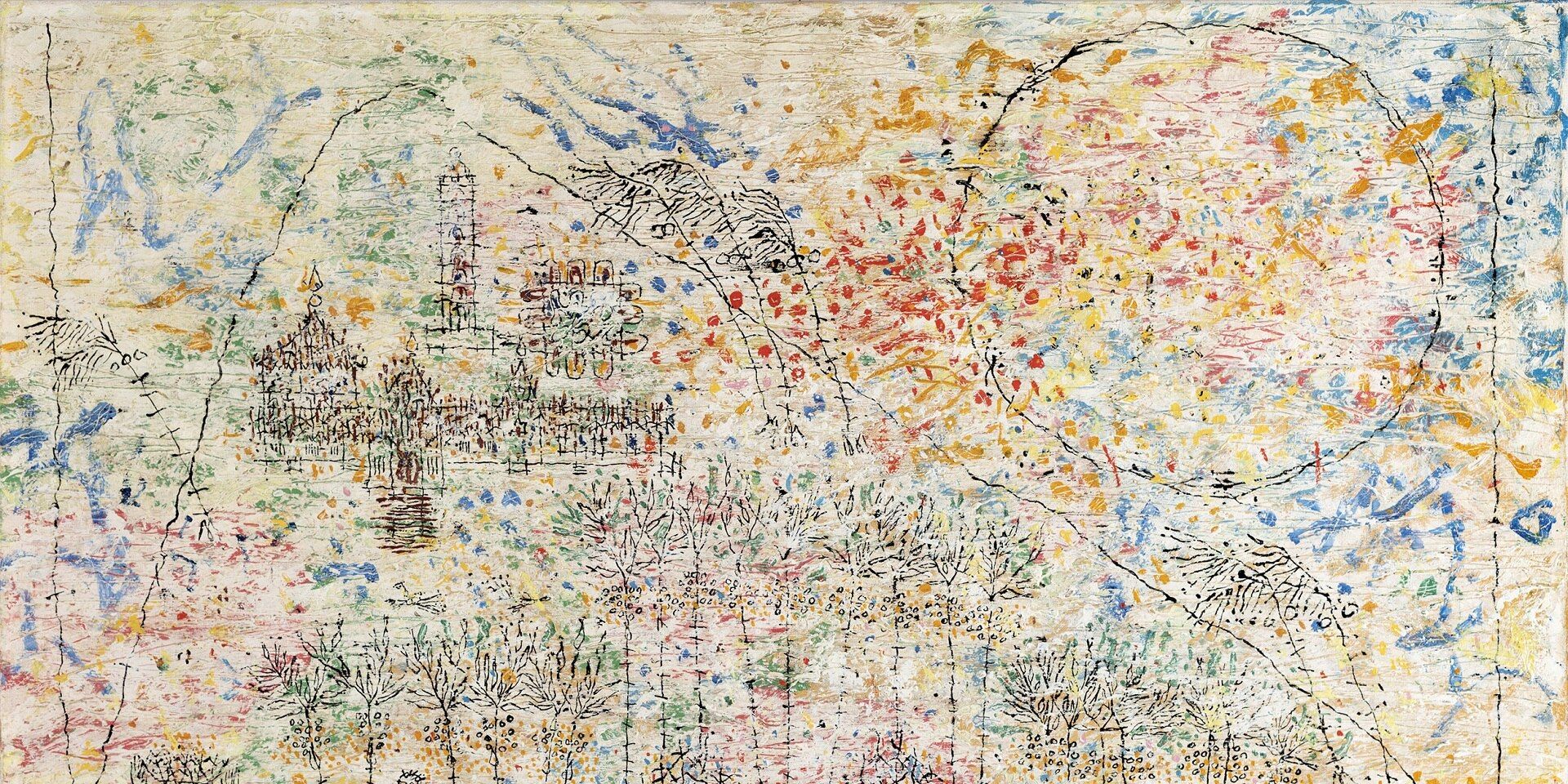

There was already a rich history of depicting Udaipur in Indian or Rajasthani art. As the art historian Dipti Khera reminds us, ‘In the long eighteenth century, artists from Udaipur, a city of lakes in northwestern India, specialized in depicting the vivid sensory ambience of its historic palaces, reservoirs, temples, bazaars, and durbars. As Mughal imperial authority weakened by the late 1600s and the British colonial economy became paramount by the 1830s, new patrons and mobile professionals reshaped urban cultures and artistic genres across early modern India.’

|

Marius Bauer, The Palace at Udeypur (Udaipur), c. 1926, Watercolour on Whatman watercolour board, 16.7 x 15.2 in. Collection: DAG |

From the miniaturists’ careful detailing of landscape and culture, that could also communicate the sensory world of the people in the paintings, the new visual economy of the nineteenth century included views made by travelling artists from the west who reacted to the splendours of the sites, buildings and waterbodies of the city. The lakes continued to play a structuring role in many of these works, as if a shiny mirror had been placed within the painted world, reflecting its life and customs as it would appear to a casual observer.

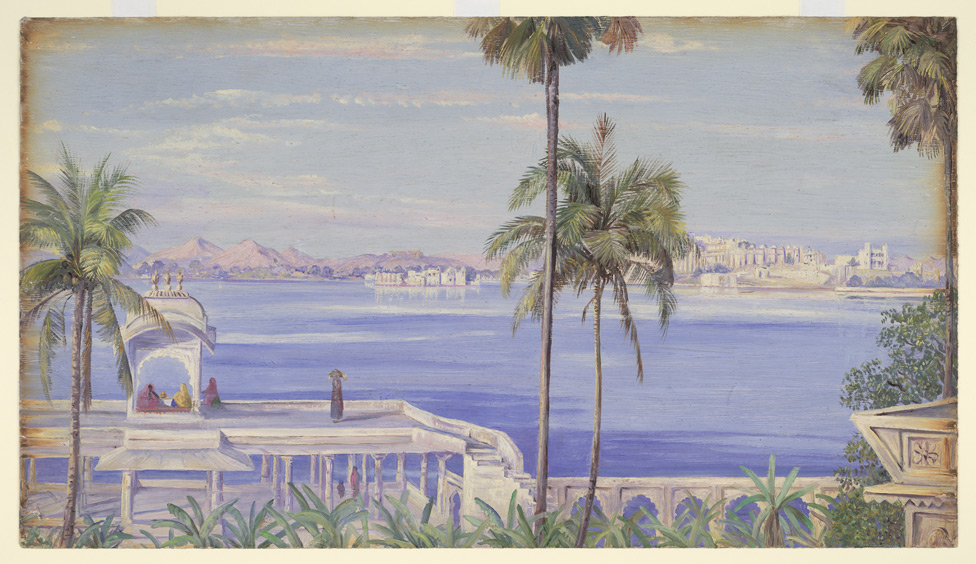

Marianne North, Udaipur from Island of Jagmandir. '1st Janr. 1879, 1879, oil on paper, 11.2 x 19.9 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Udaipur's architecture is characterised by its extensive use of white marble, which gives the city a distinctive and elegant appearance. The most notable example is the City Palace, a sprawling complex built over several centuries by successive Maharanas of Mewar. The palace features a mix of Rajput and Mughal architectural styles, with intricate carvings, arches, and domes adorning its white marble walls.

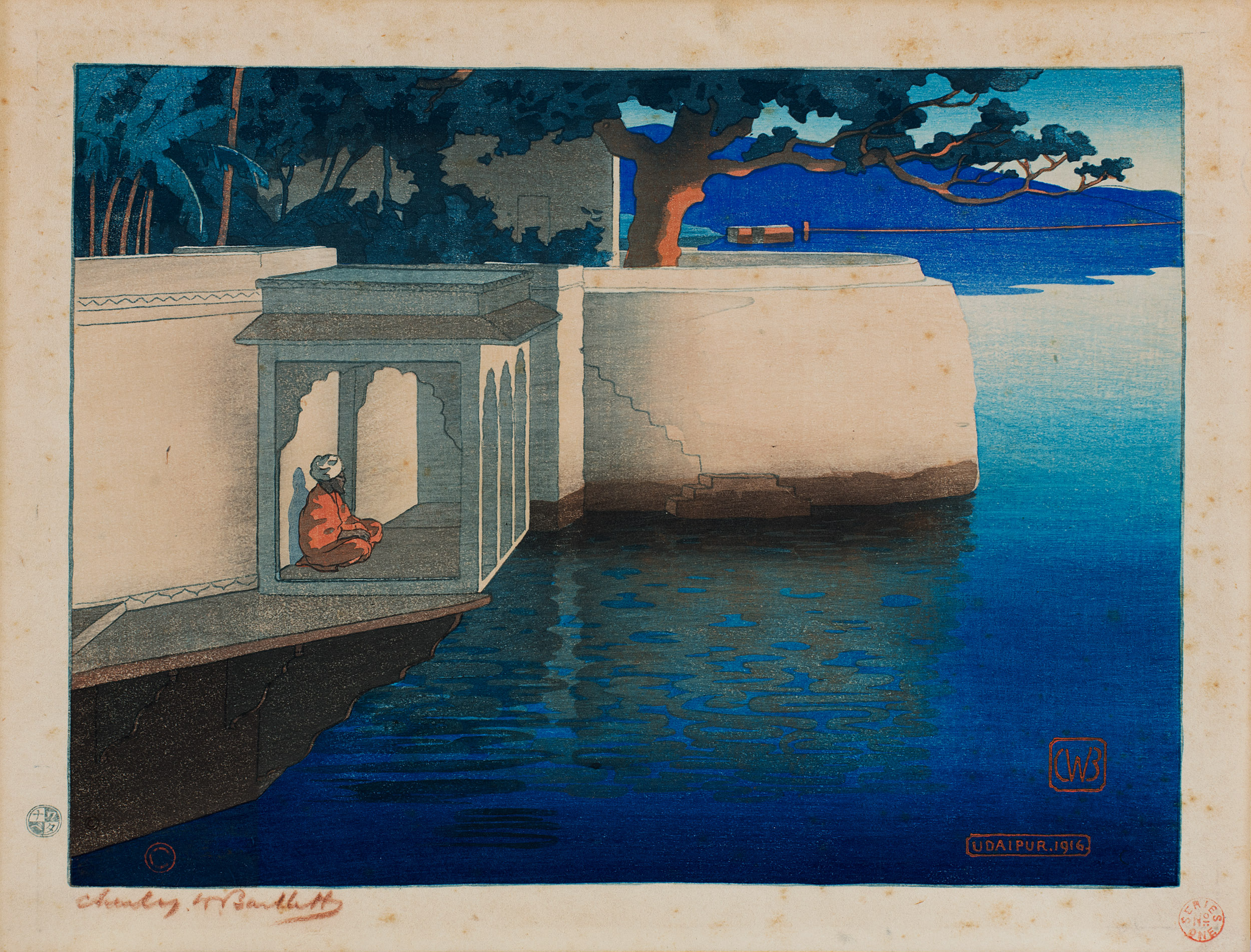

Charles William Bartlett, Udaipur, 1916, Kokka woodblock print on paper, 8.7 x 12.0 in. Collection: DAG

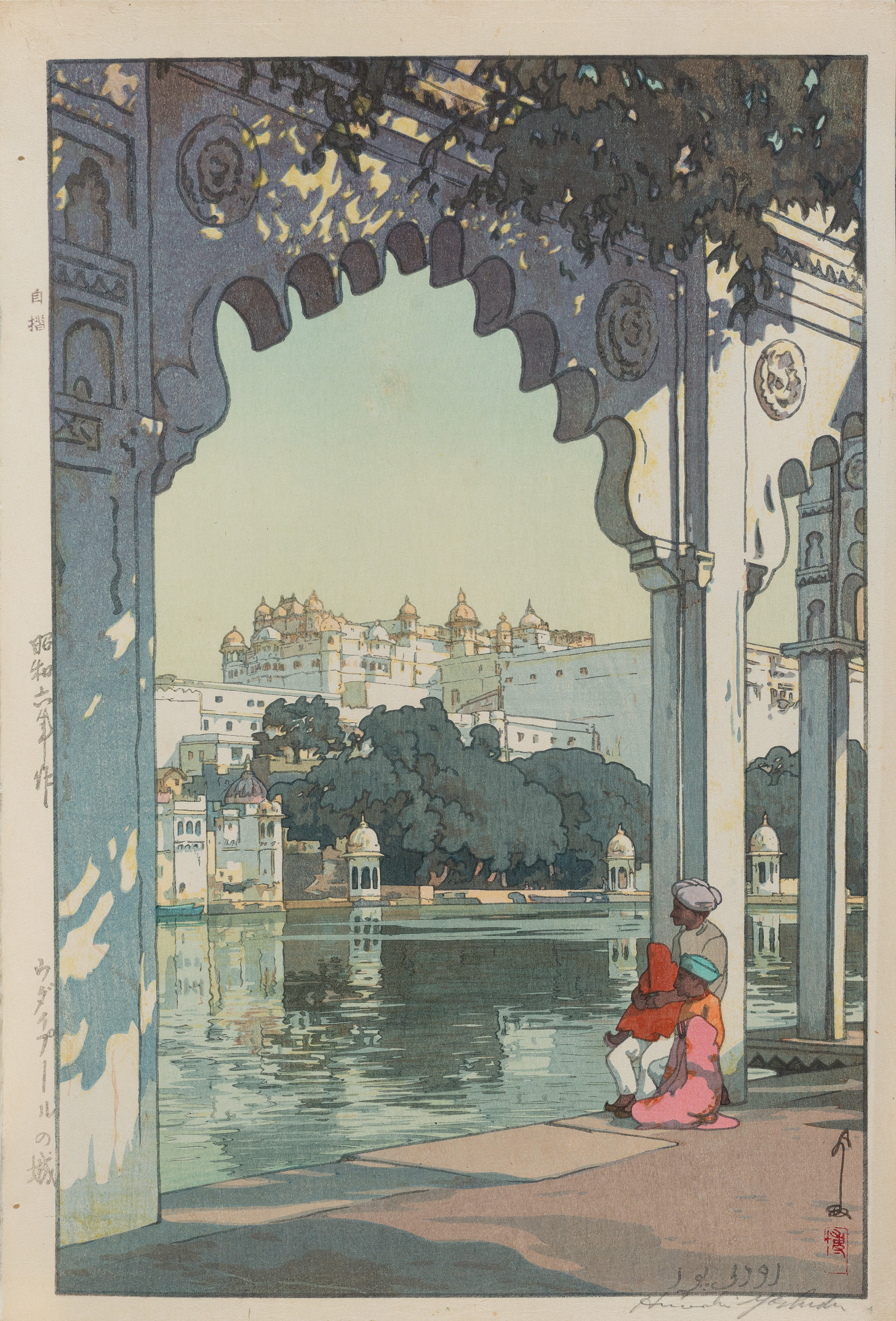

While Udaipur's white architecture has been celebrated in Indian art for centuries, it also caught the attention of European artists who visited the city in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Writers and painters like Edwin Lord Weeks (1849-1903) travelled to the city, wrote about it and painted its views, along with others like Marius Bauer, C. W. Bartlett and Hiroshi Yoshida—one of the few who was not from the West, but from Japan. Weeks was an American artist and adventurer known for his vibrant paintings of the Middle East and India. Born in Boston to a wealthy family of spice and tea merchants, Weeks began traveling and painting at a young age, visiting South America, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, and Persia in the 1870s and 1880s.

|

Hiroshi Yoshida, Udaipuru no shiro / Udeypoor, 1931, Kokka woodblock print on paper, 14.7 x 9.7 in. Collection: DAG |

He documented his experiences in the book From the Black Sea through Persia and India, which featured sketches and paintings of scenes in cities like Karachi, Lahore, Amritsar, Benaras (now Varanasi), Mathura, and Agra. Weeks returned to India several more times between 1887 and 1893, traveling extensively through the princely states of Rajputana and Malwa (present-day Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh). He made numerous drawings and paintings depicting the life and architecture of these regions, which he collectively referred to as ‘India of the Rajahs’. His paintings are known for their rich colours, attention to cultural details, and ability to transport viewers to distant lands, which can be said about his travel writing as well. What did he have to write about the views around Udaipur? He was especially attentive to the calm, white tone that prevailed over the architecture, besides the flashes of colour that he witnessed at the marketplaces. His impressionist account veers on the ekphrastic, as if he were witnessing richly painted tableaus.

Here is an extract from his travel account From the Black Sea through Persia and India:

Oudeypore is a white city. Not only the pavilions, kiosks, and arcades which rise from the shores of the lake, but the lower walls of the great palace, the island palaces, and the town itself, are positively dazzling with whitewash.

A fellow-countryman whom I met on the road, whose name is everywhere known as an authority on Indian art, said that he had been greatly disappointed in Oudeypore, mainly because the whitewasher's brush had given it the semblance of a whited sepulchre. With all deference to his taste and judgment, I found the prevailing color to be rather agreeable than otherwise, and to have an enhanced value from its setting of dark foliage, so often relieved by brilliant masses of flowering vines.

Edwin Lord Weeks, The Lake at Oodeypore, India, Oil on canvas pasted on Masonite board, c. 1893, 30.0 x 50.0 in. Collection: DAG

The whitewash is not used in order to hide baseness of material, for most of the architecture is solidly built of the dark red sandstone of the country, purely Hindoo in style, abounding in colonnades with dentilated arches, and with richly sculptured brackets upholding the horizontal eaves: white, with its luminous reflections and cool shadows, is far more restful to the eye than the dull brick color of the stone beneath.

The warmer tone of marble, where it appeals in the upper parts of the palace and in the inner courts of the island pleasure-houses, gains in value from its rarity. In going through the town for the first time one cannot fail to be impressed by its bright and generally attractive aspect. A drawbridge across the moat gives access to the great gateway studded with spikes: beyond this is a court-yard surrounded by high walls and guarded by soldiers. Here we enter the broad sandy road which leads us to the main bazaar. The continuous rows of shops are sheltered behind wide verandas and in the shadow of projecting eaves, which are supported by square Hindoo columns, shaped like the more ancient columns in the temple of Chitor, and by sculptured brackets or consoles. Behind these colonnades there is an ever-changing play of reflected light, and the patches of crude or half-effaced painting on the inner walls have an added value from the warm white which prevails. Even the costumes of the men are of the universal tone, varied by the scarlet and gold lace of turbans, and the costumes of the court retainers, while the embroidered shawls and skirts of the women are of every imaginable hue, so that these brilliant flashes of color in the passing crowd, together with the gaudy dyes displayed around the shop doors, toned by the luminous obscurity of the shadow, all unite in producing an impression at once sparkling, joyous, and festal.

Edwin Lord Weeks, The Lake at Oodeypore, India (detail), Oil on canvas pasted on Masonite board, c. 1893, 30.0 x 50.0 in. Collection: DAG

This work was first exhibited at the ‘Internationale Kunst -Ausstellung’, Berlin, 1896 to celebrate the two hundredth anniversary of Bestehens der Königlichen Akademie der Künste, and will go up on display once again during DAG’s historic exhibition, Destination India, later this month.

related articles

Essays on Art

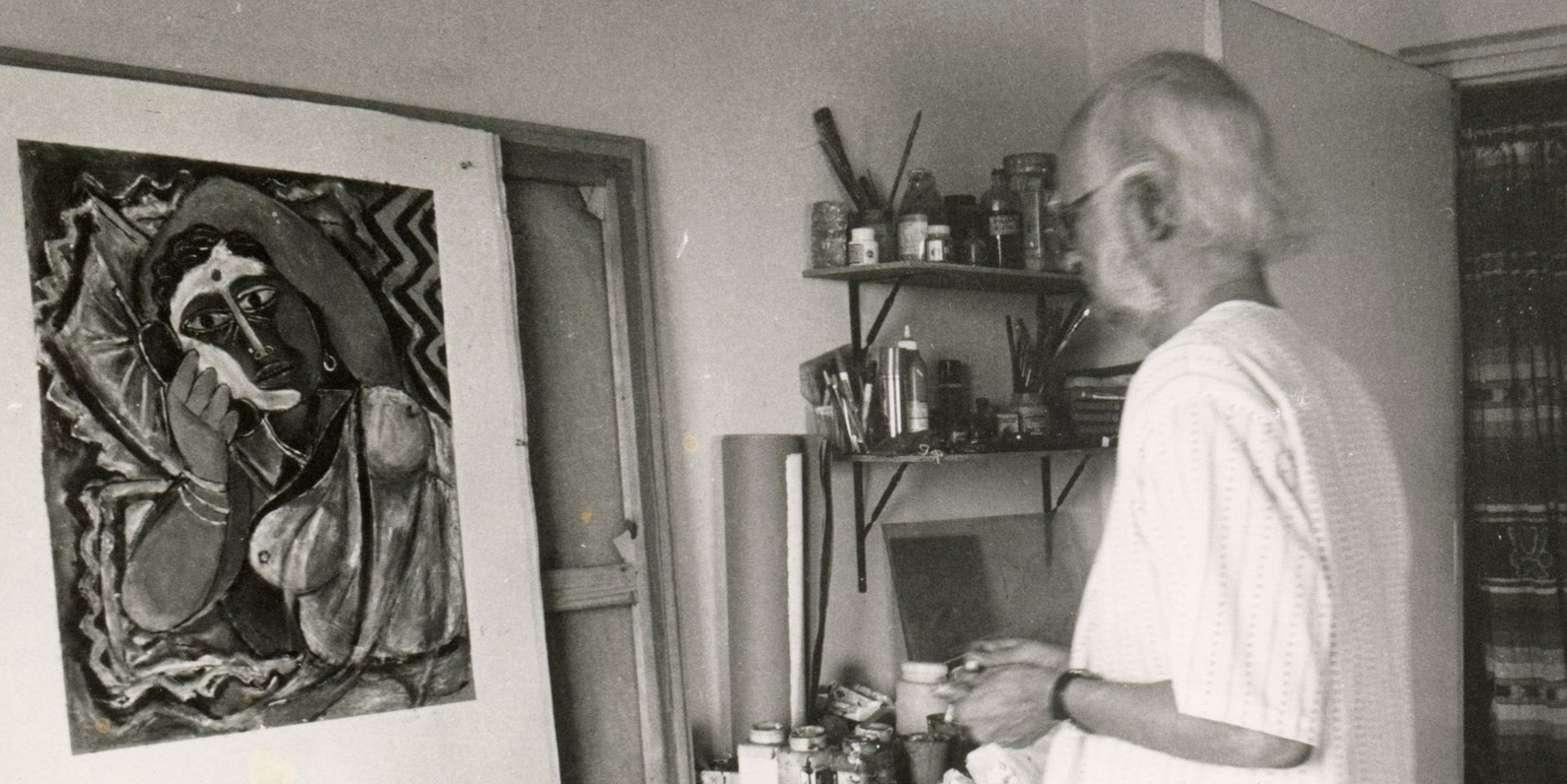

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

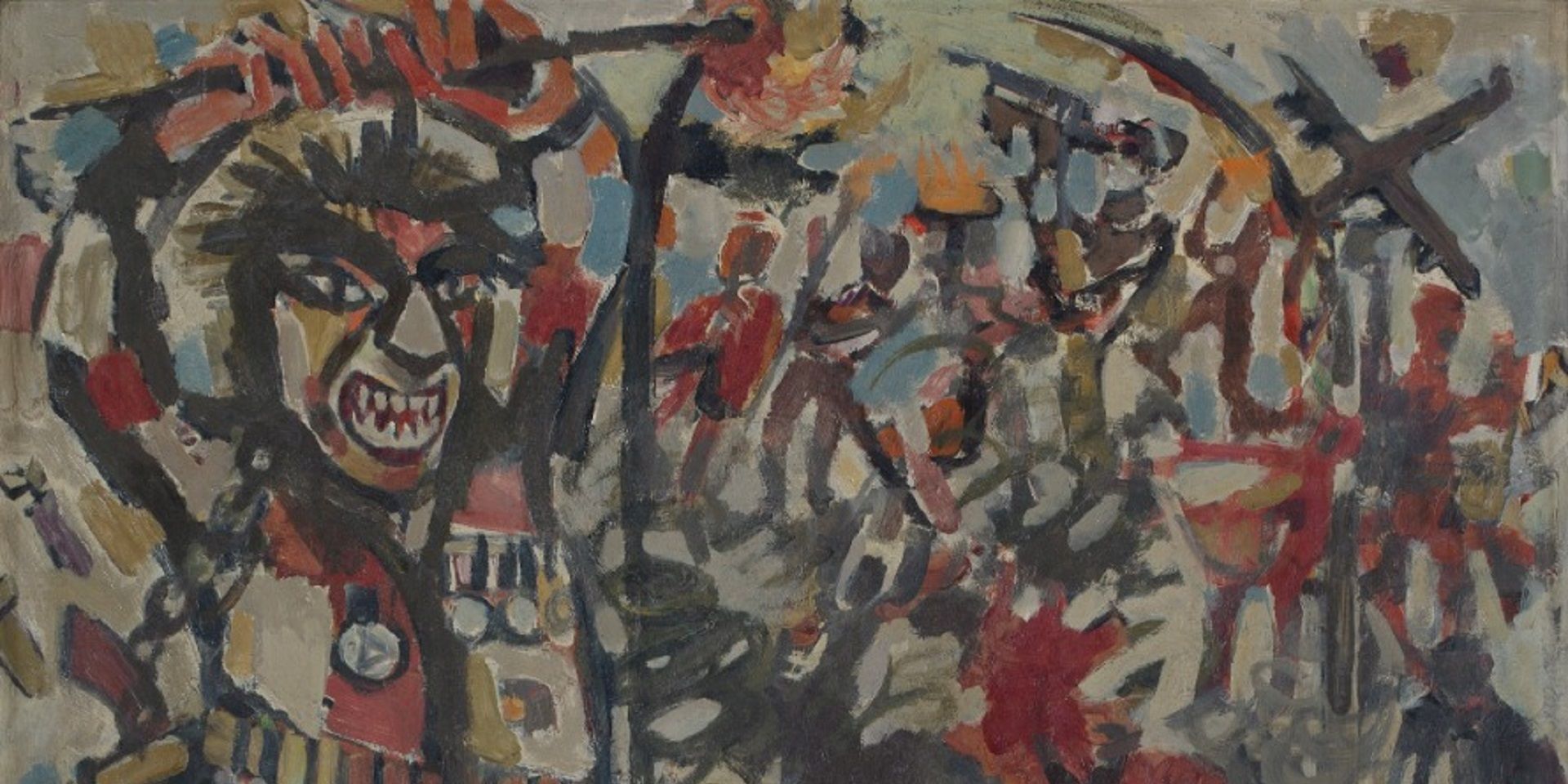

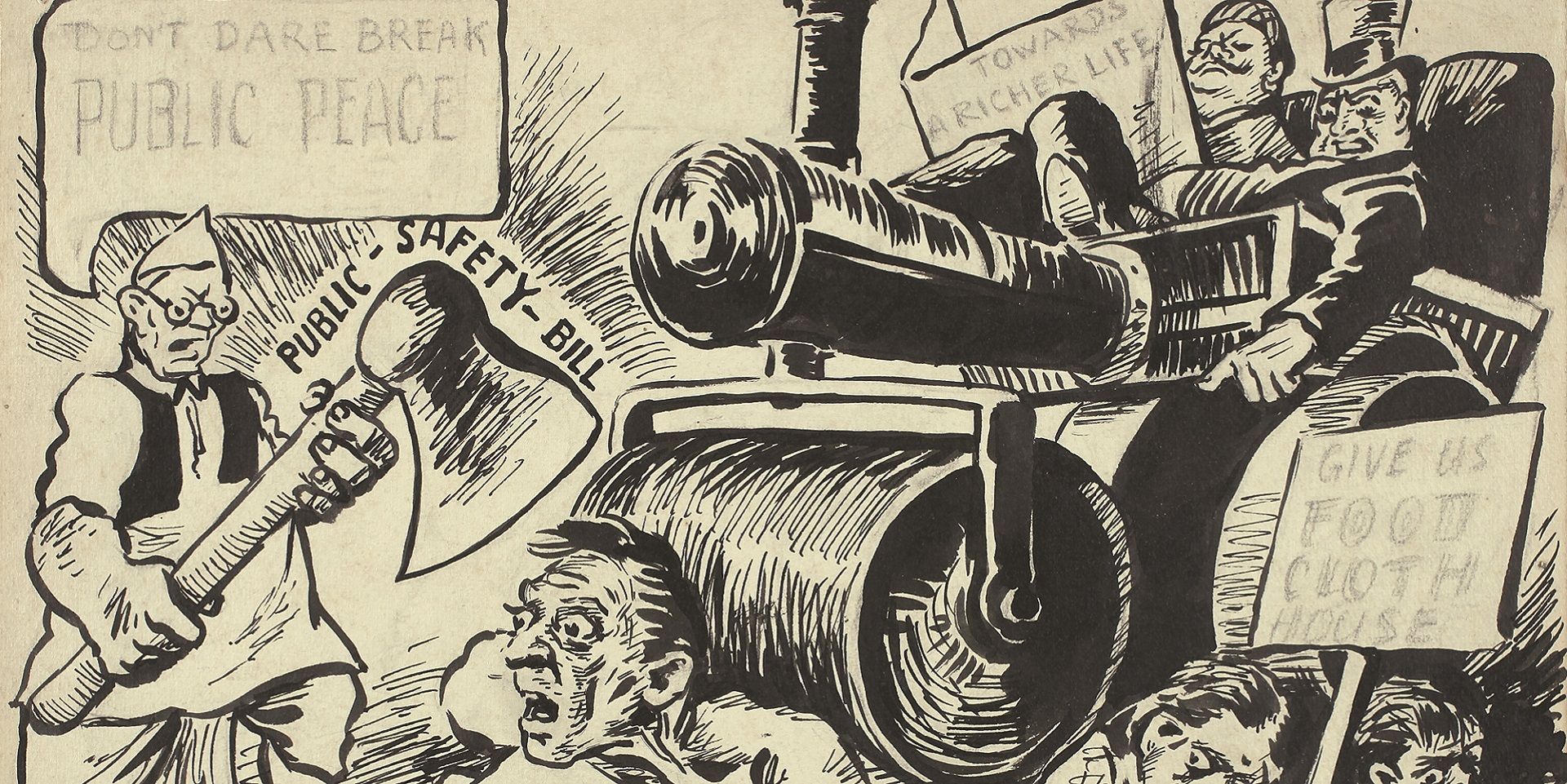

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

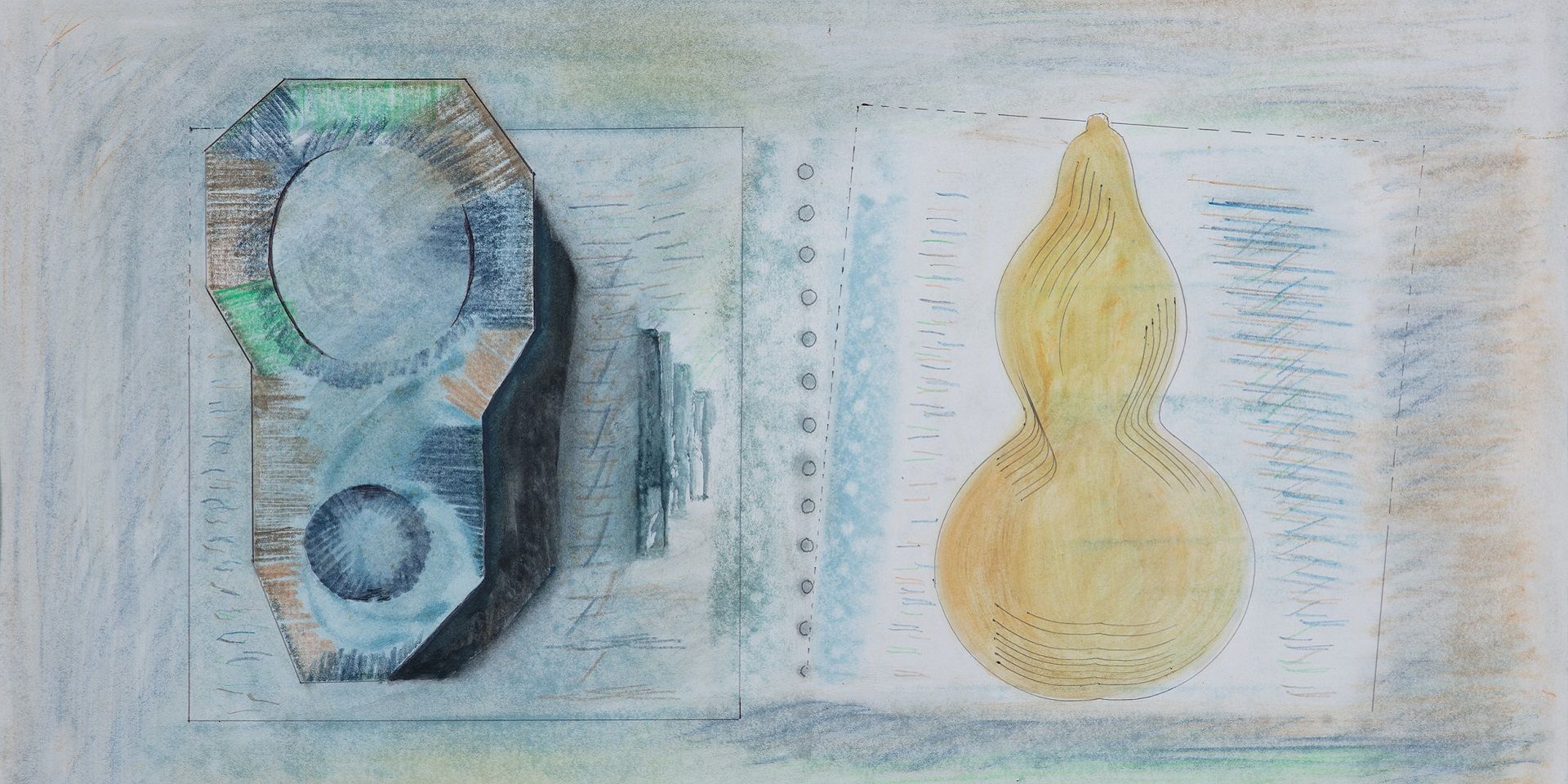

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

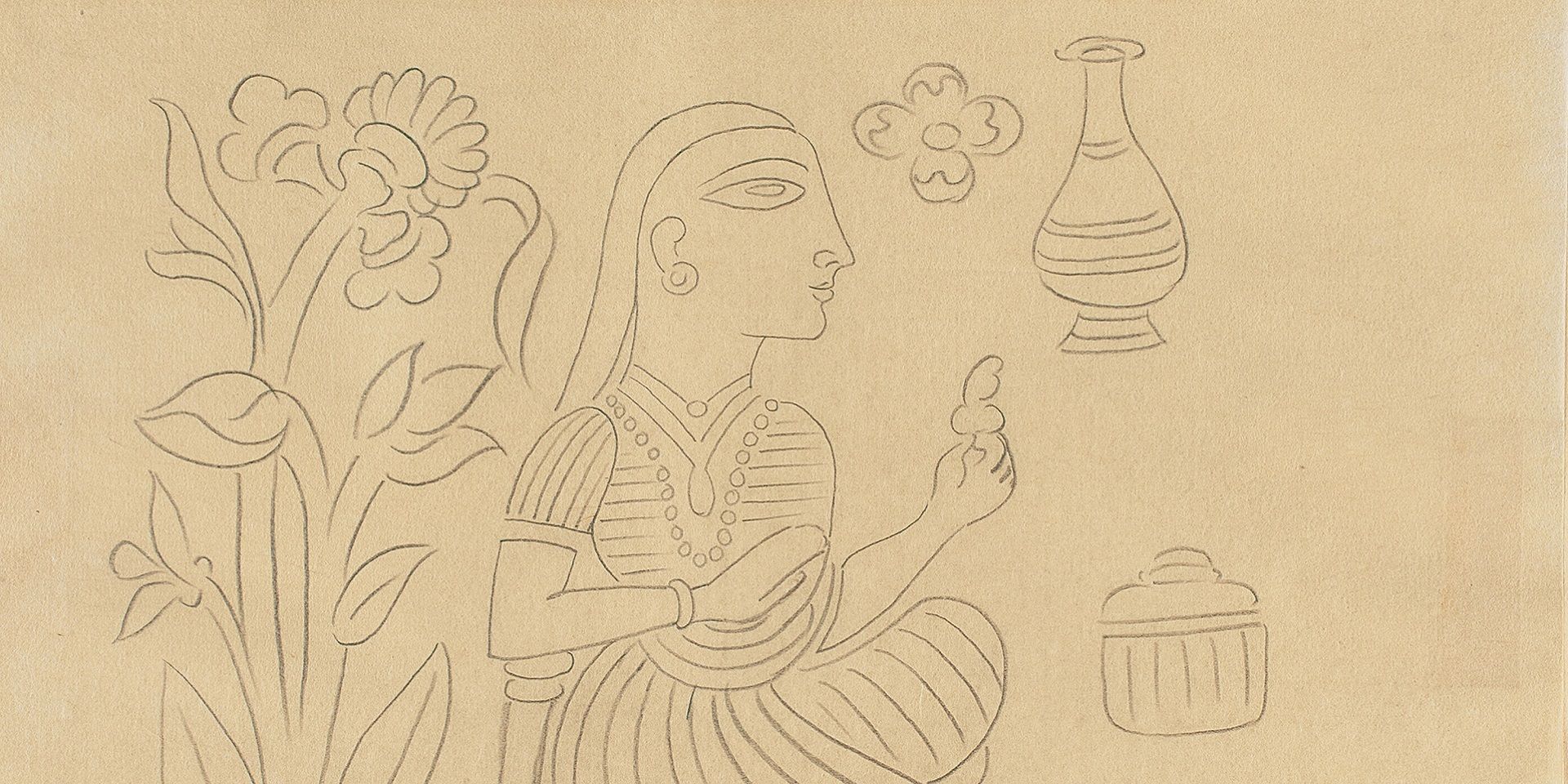

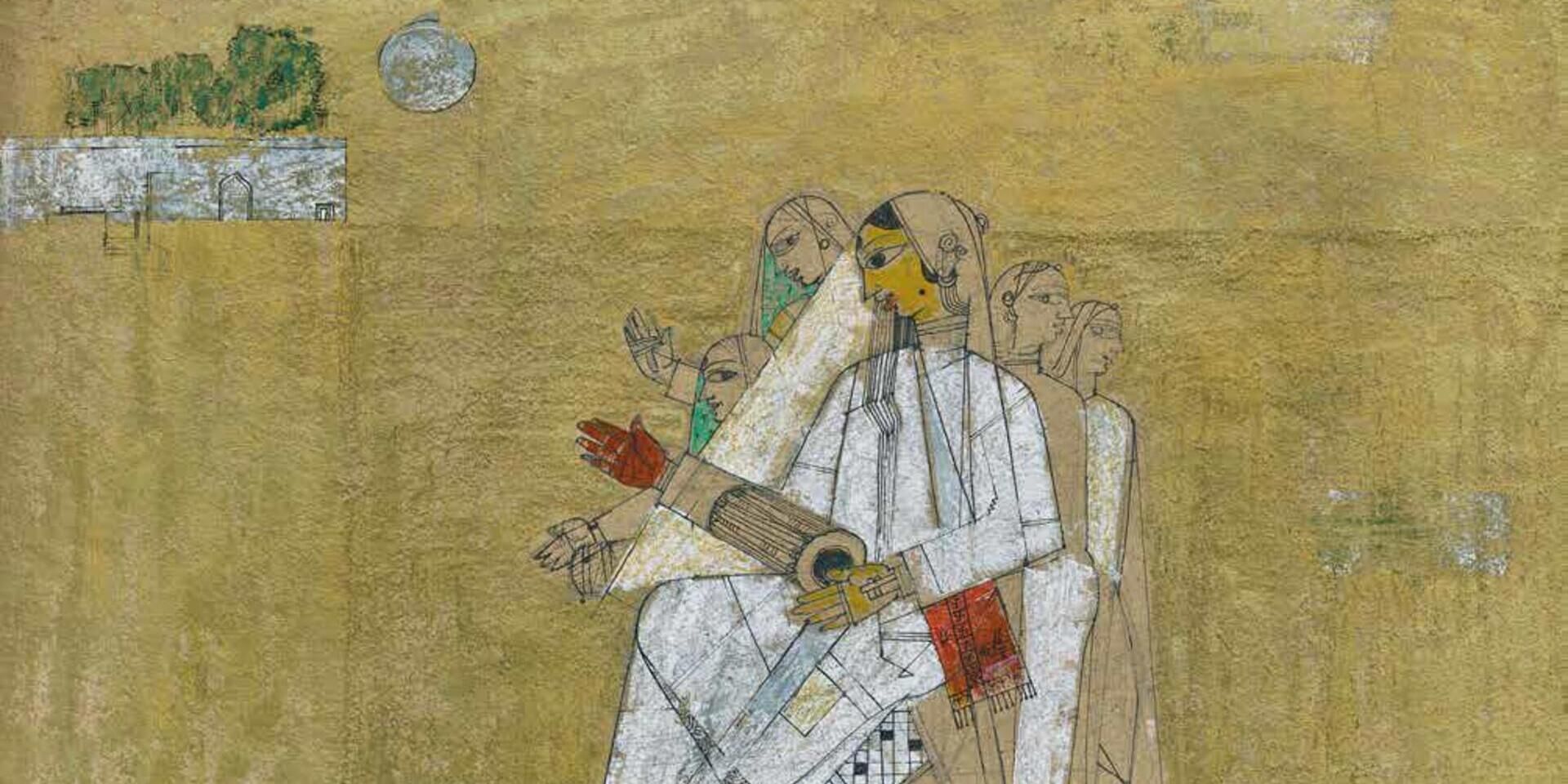

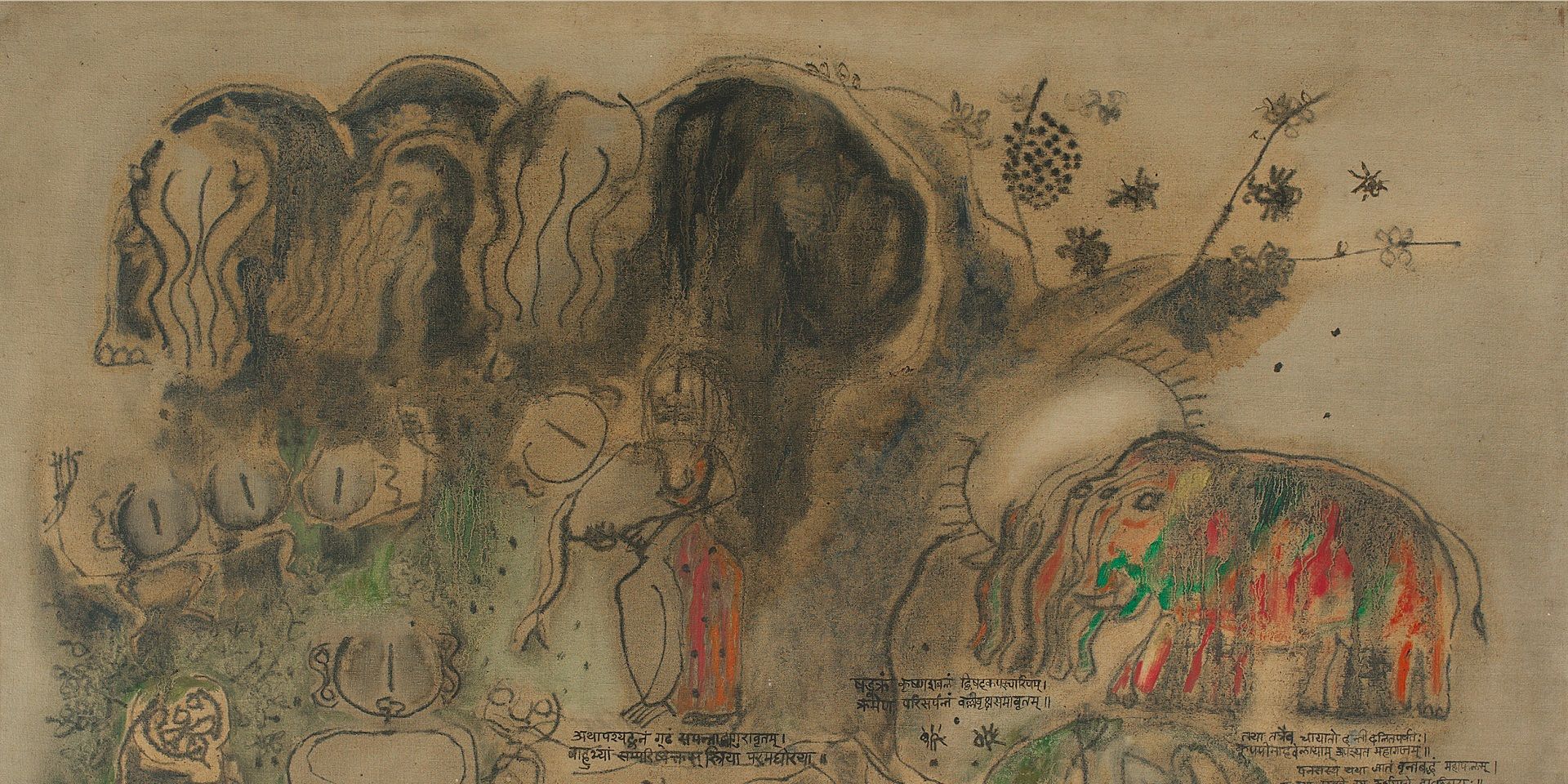

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

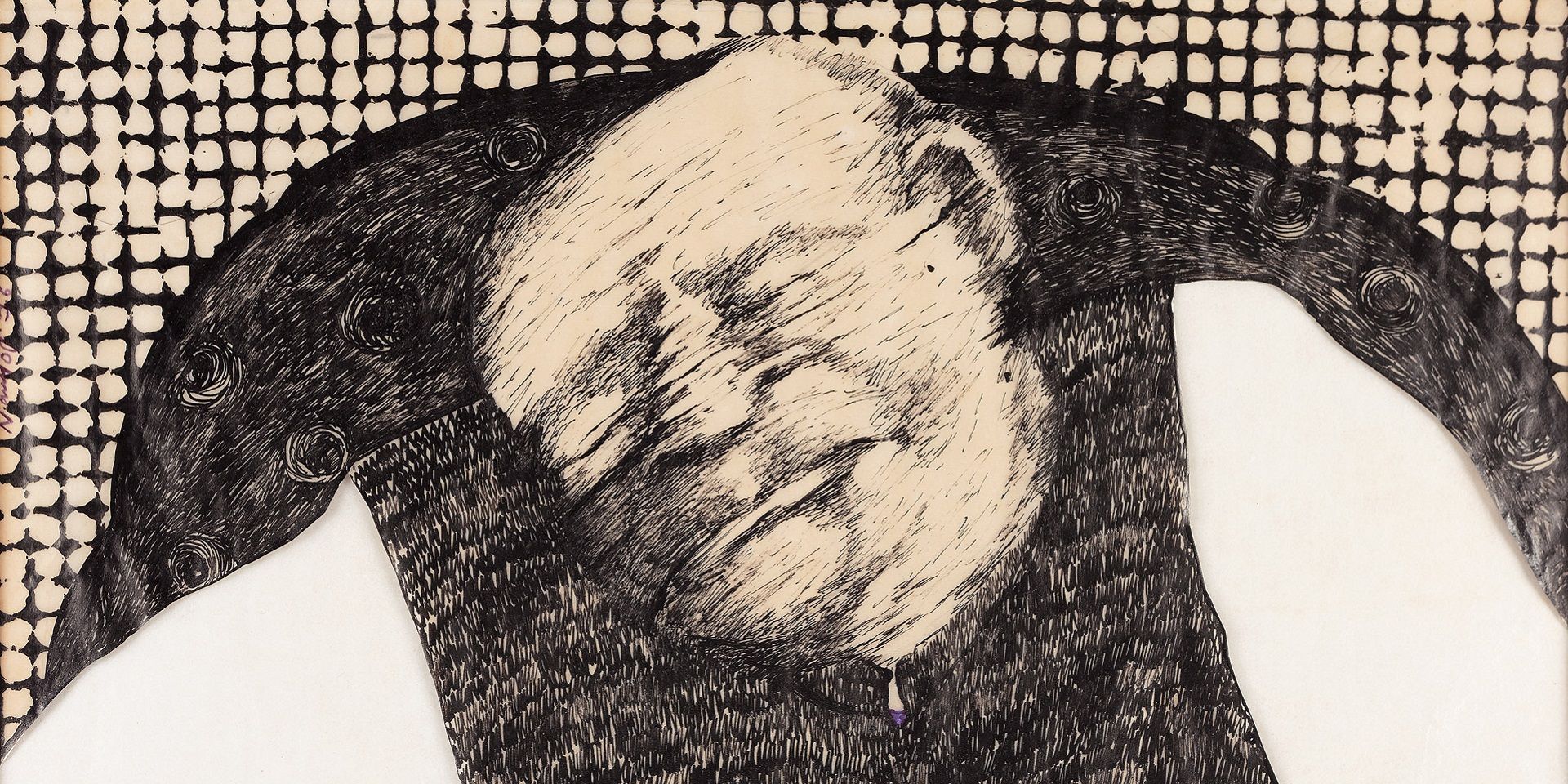

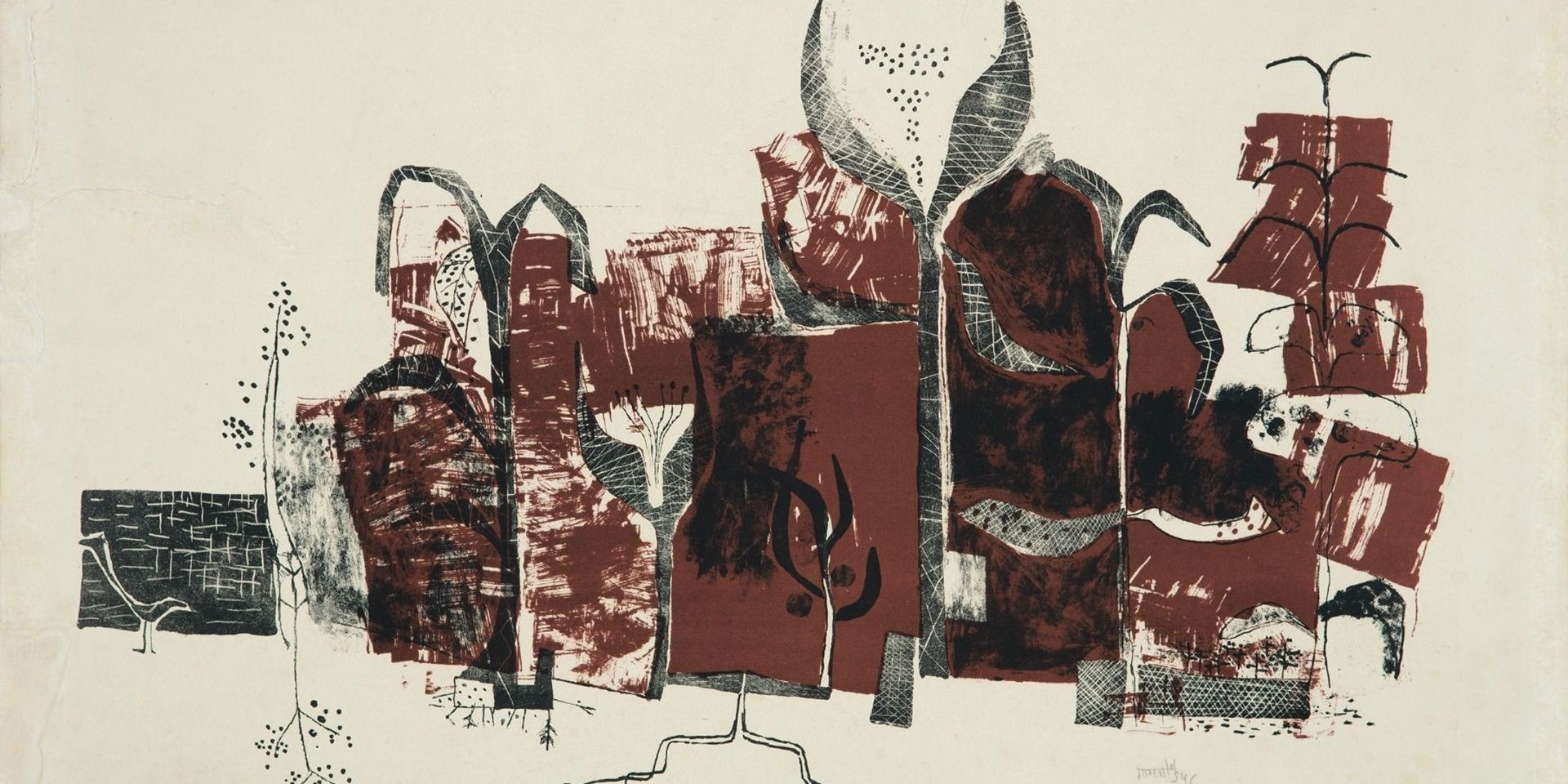

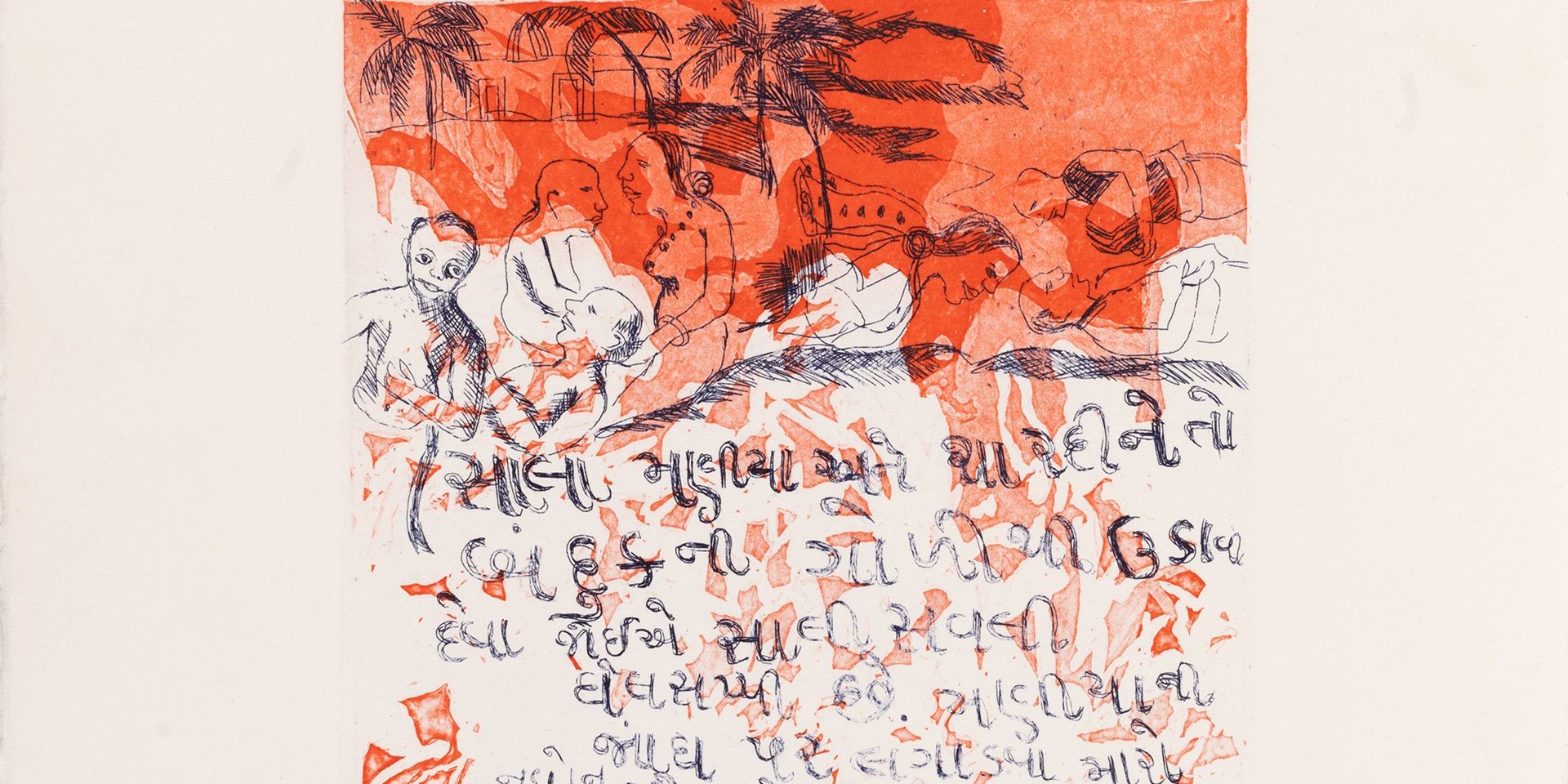

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024