'Adhi noi Tebhaga chai': Somnath Hore's Activist Art

'Adhi noi Tebhaga chai': Somnath Hore's Activist Art

'Adhi noi Tebhaga chai': Somnath Hore's Activist Art

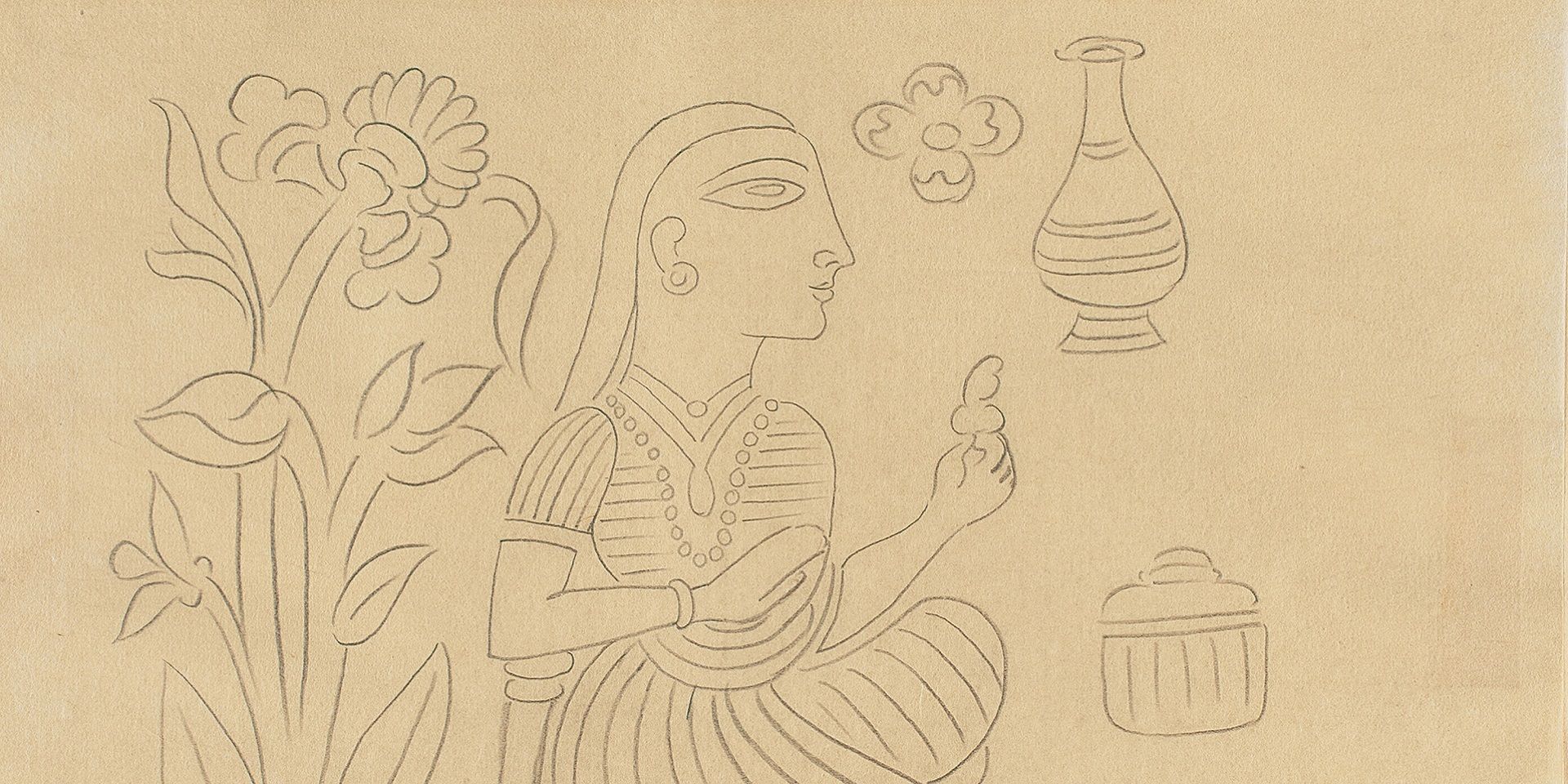

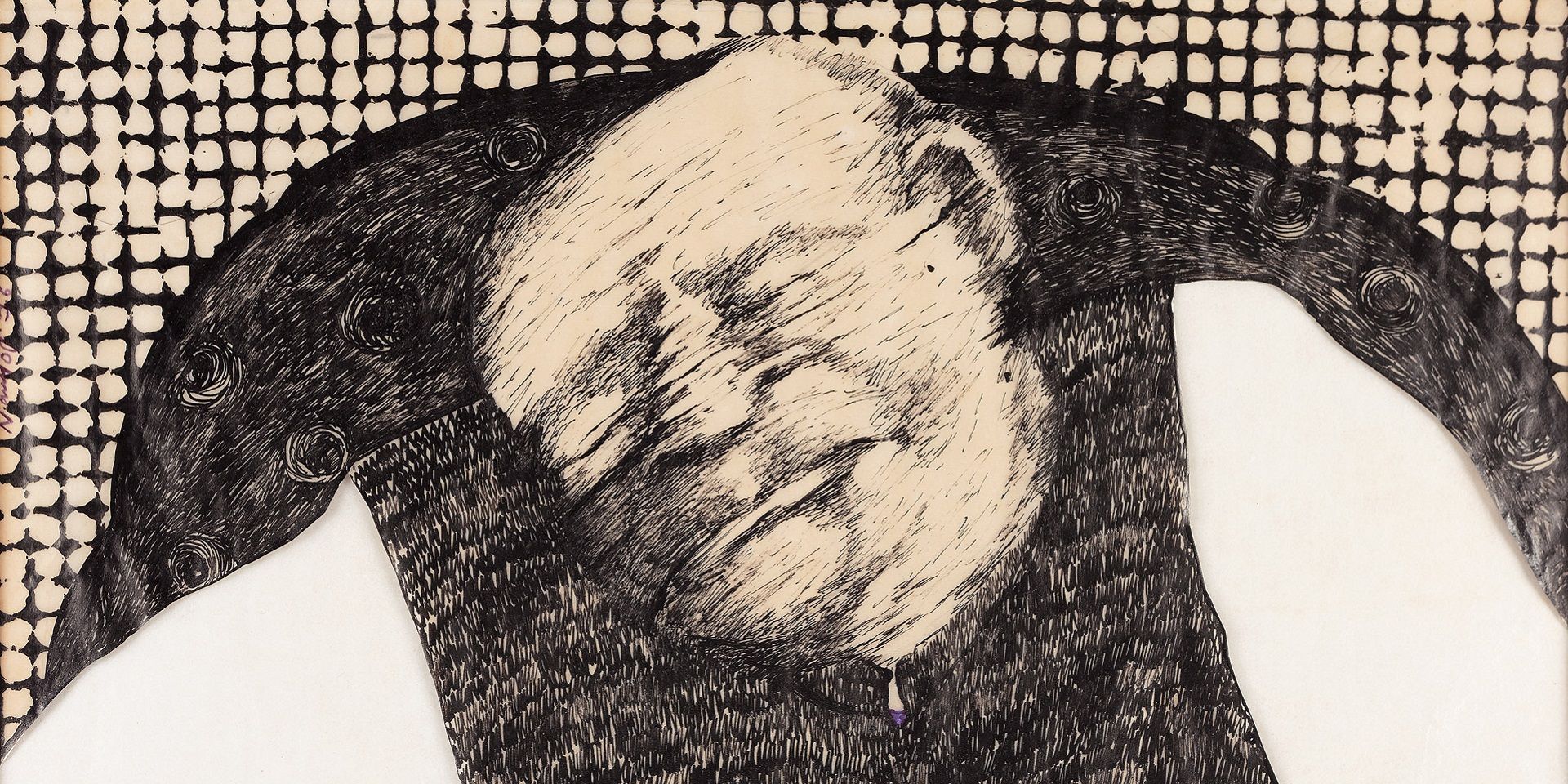

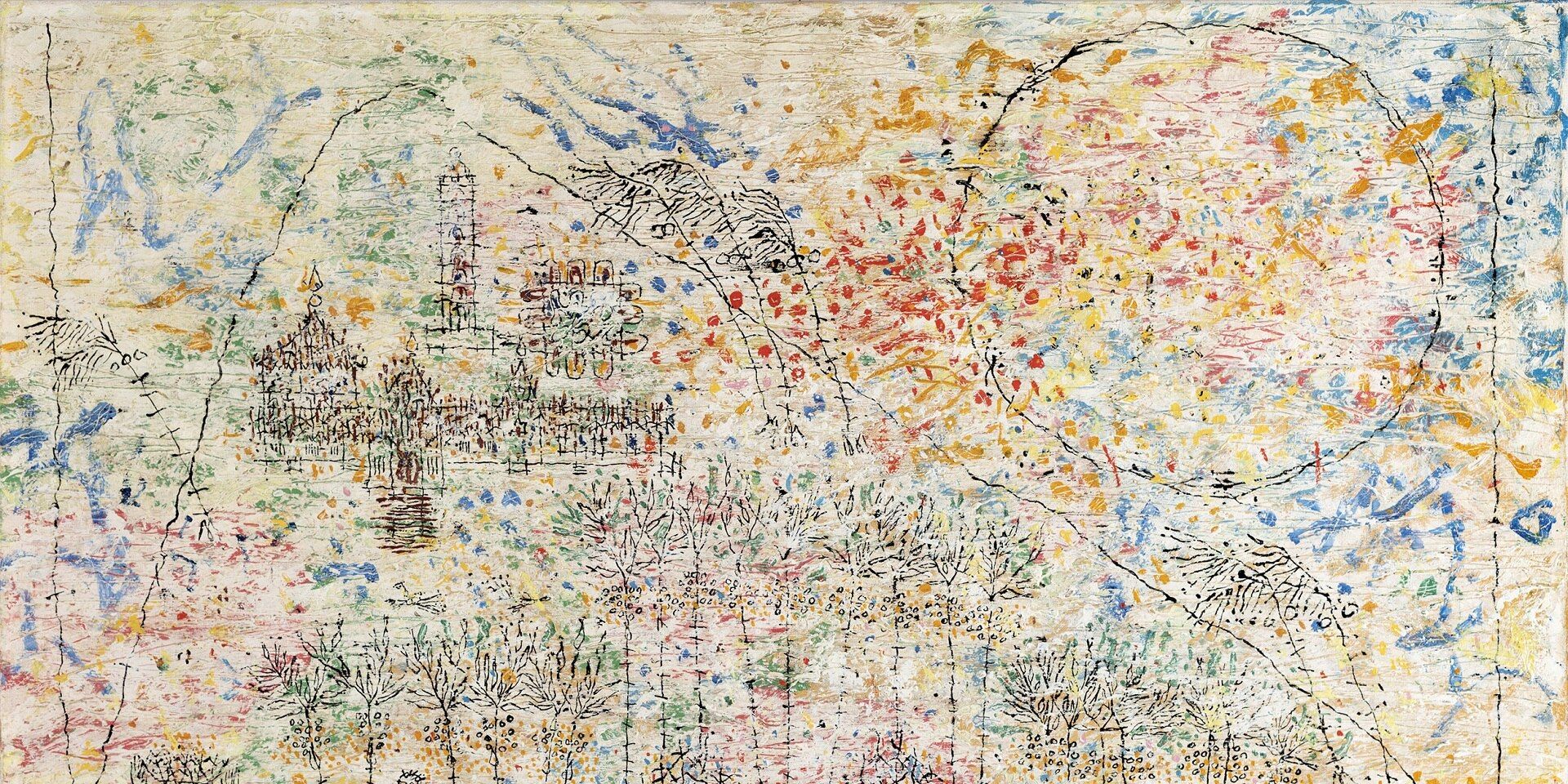

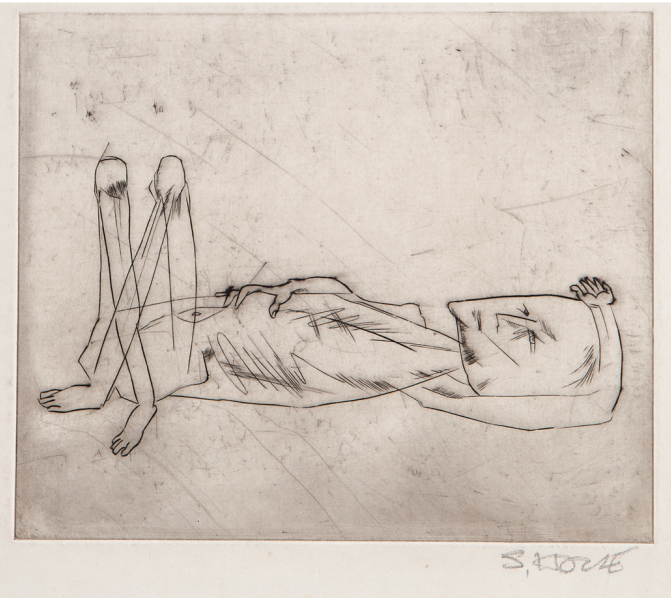

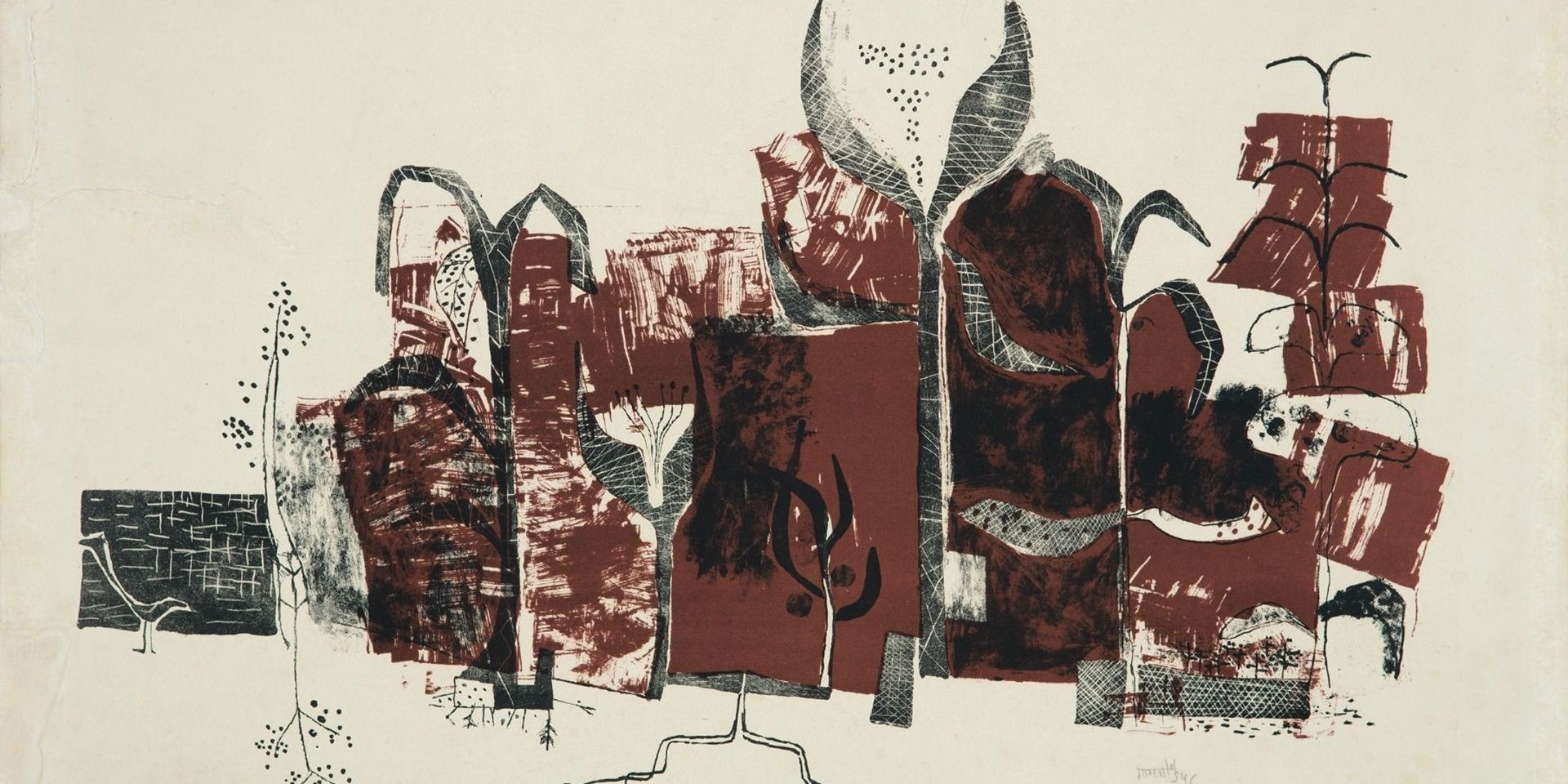

Somnath Hore, Untitled (detail), Etching on handmade paper, 5.2 x 7.2 in. Collection: DAG

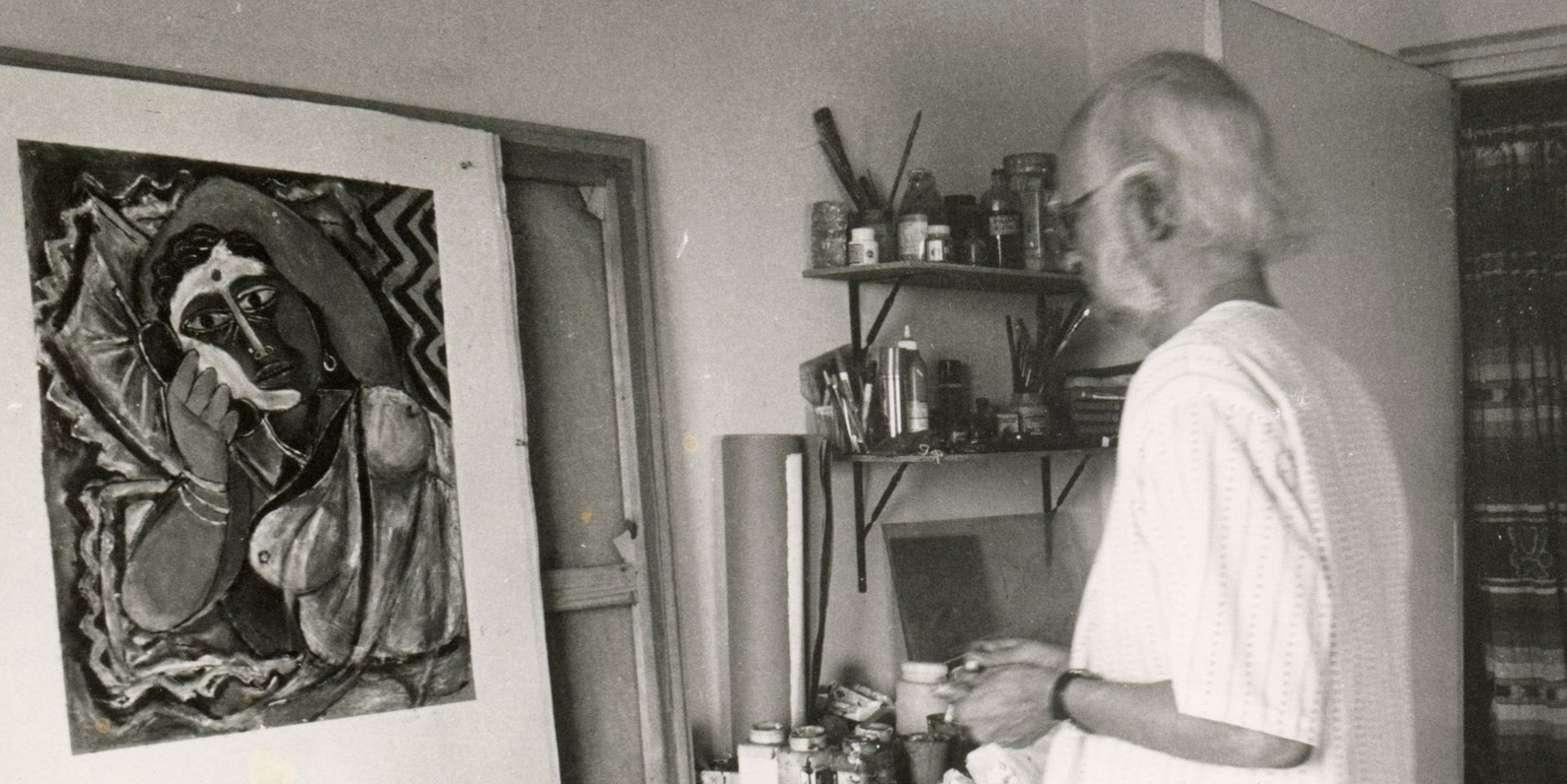

Somnath Hore, born in 1921 in Chittagong (now Bangladesh), emerged as a pivotal figure in modern Indian art, profoundly shaped by the socio-political upheavals of twentieth century Bengal. His artistic journey was deeply intertwined with his early affiliation with the Communist Party, which not only influenced his ideological stance but also provided him access to formal art education at the Government Art College in Calcutta.

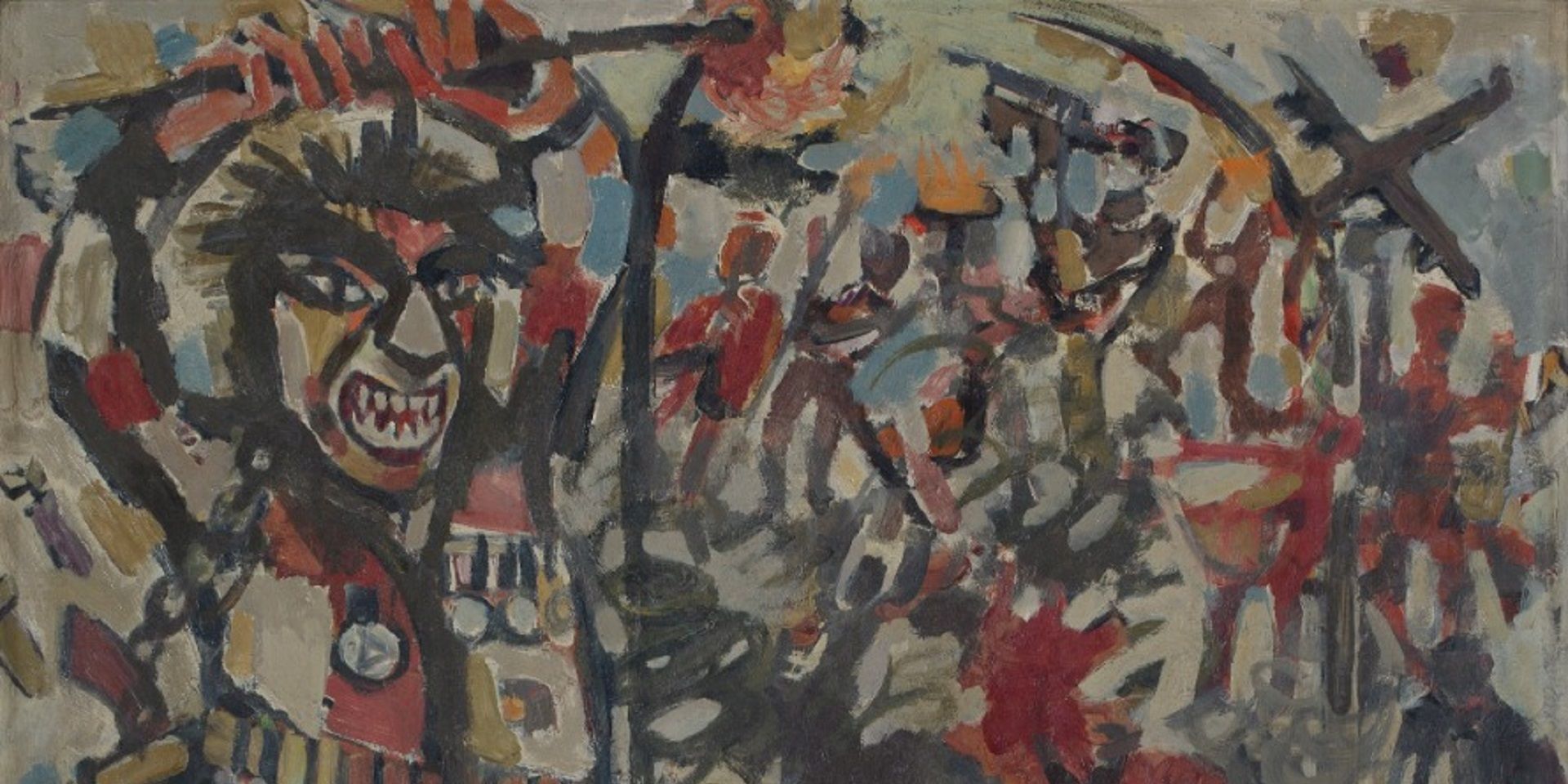

Hore's work is characterised by a visceral engagement with human suffering, a theme that resonates throughout his sketches, prints, and sculptures. His early artistic endeavours were marked by a response to significant historical crises, notably the Bengal Famine of 1943 and the Tebhaga movement of 1946. Frequently tasked with making posters for the then illegal Communist Party, Hore, since his school days, was a highly active servant of the party. As he made his way to Rangpur ‘on a stifling Calcutta night of 17 December 1946’, Hore carried a diary where he would carry out his assignment: to document the massive mobilisation that was taking place and capture the widespread spirit of the Tebhaga Movement.

|

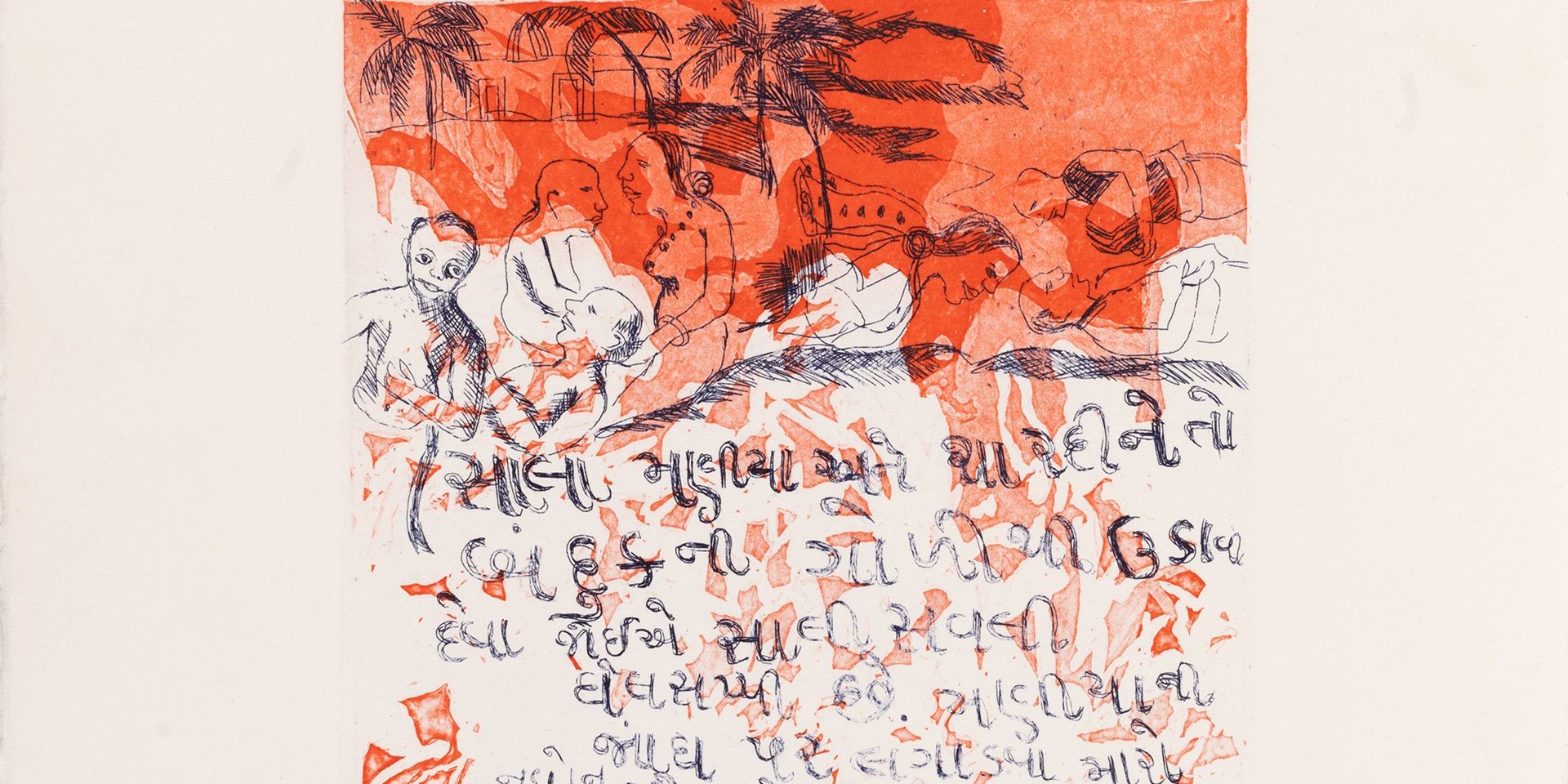

Somnath Hore, Untitled, Etching on handmade paper, 5.2 x 7.2 in. Collection: DAG |

A mass insurgency initiated by the Bengal Provincial Kisan Sabha, the Tebhaga Movement (1946–47) rallied thousands of impoverished peasants, led by both urban and rural activists, to demand two-thirds of their harvest instead of the customary half. Spanning over just ten days, Hore’s subjective account of the movement, gives an insight to a lived reality of a young radical activist-cadre brimming with hope for an upcoming revolution that lies inaccessible to other purportedly ‘objective’ historiographies of archival records. In this context, Somnath Hore emerges as a sharp witness, vividly documenting the enthusiasm of a united peasantry. As he travels through Rangpur, he encounters a range of peasants and activists in different situations, capturing their experiences through both his writings and sketches. One such individual is communist organiser and Kisan Sabha leader, Mani Krishna Sen.

Somnath Hore, Mani Krishna Sen. Hore's hand-written caption reads: 'Com. Mani Krishna Sen. He has sustained a scalp wound in an attack from a Marwari jotedar. Some other parts of his body have been further injured'. Collection: DAG Archives

Hore met Sen when the latter had sustained a nasty scalp wound in an attack from a ‘Marwari’ jotedar. Even on the day of it, multiple narratives emerge of the event, navigating through which, Hore identifies the following story to be more accurate:

‘As Mani-da was preparing to sit down for his midday meal at Baburi Burman's house on 20 December, jotedar Koramal came there with about a dozen people... When Mani-da, alerted by the noise, went up to them, Koramal charged him, 'Are you the man who's inciting the sharecroppers?’ and forthwith struck him on the head with a lathi. At this comrade Bipin Burman attacked Koramal with a small staff, but he had to fall back before Koramal's hired thugs. It was at this moment that Baburi's old mother, the only other person in the house, picked up a husking pestle and hit Koramal. She was struck down by Koramal's thugs... Meanwhile, people had started gathering on receiving news of what had happened. Koramal, unnerved by this, started firing in the air…’ Subsequently, her accounts disappear from the archives.

Somnath Hore, Mother of Baburi Burman. Collection: DAG Archives

In the malleable terrain of memory, mediated through affect, tensions arise. Forty years later, in a memoir remembering the Tebhaga Movement, Mani Krishna Sen would tell a different story, recalling how, when he accompanied Bipin Burman to confront a group of sharecroppers defying the party’s directives, he was confronted by ‘a group of 10–12 people armed with sticks, spears, and knives, led by a mounted man with a gun. There was no way to retreat. As far as I remember, the place was an open field with only a house consisting of two or three huts... A heavy blow injured Bipin’s hand, and his bamboo stick fell to the ground... I picked it up and stood blocking the way to prevent the attackers’ advance. The men of the huts had fled, and the cries of women and children echoed inside. Some distance away, a small crowd of marketgoers with two or three familiar faces had gathered. I had hoped that realizing the danger behind them, the enemy would retreat, freeing this innocent sharecropper family from humiliation. But as paralyzed with indecision, the unorganized crowd remained silent spectators, a heavy stick struck my head and blood streamed down, blinding my eyes. I somehow escaped through the back door to save myself.’ Aware of the other version, Sen commented: ‘This being an incident occurring four to five decades ago, a lack of proper investigation [sic], can lead to the severe distortion of the facts.’

Discrepancies like these reveal how historical moments become sites of negotiation, as individuals selectively choose what to remember or record, influenced by their desires and fears, joys and anxieties, as well as shifting perspectives and relationships over time.

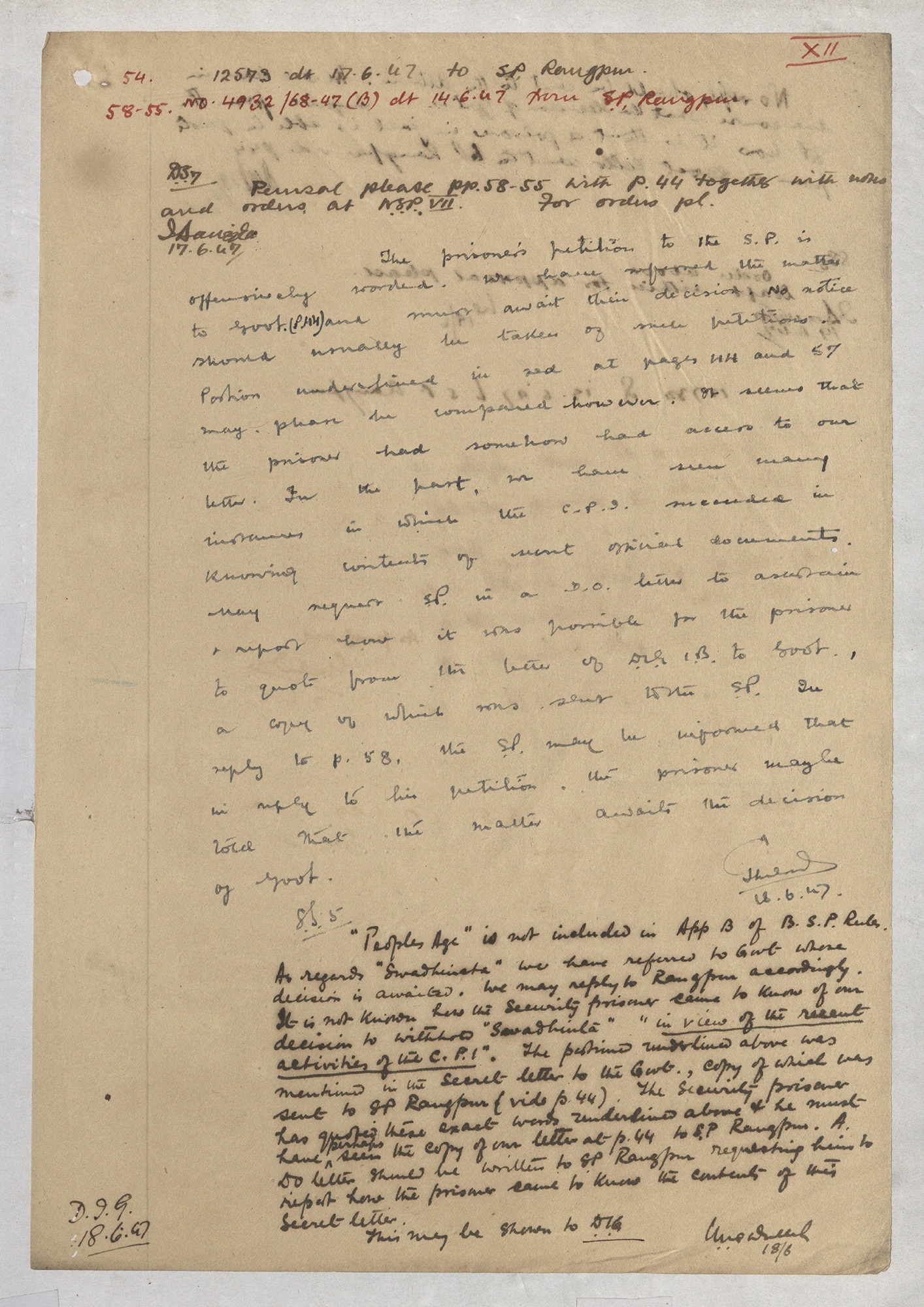

Excerpt from ‘Brief History of Mani Krishna Sen’. File 890/31, Mani Krishna Sen Gupta, under the custody of Directorate of State Archives, Kolkata.

Excerpt from ‘Brief History of Mani Krishna Sen’. File 890/31, Mani Krishna Sen Gupta, under the custody of Directorate of State Archives, Kolkata.

Many activists like Mani Krishna Sen have their names and activities recorded in confidential police files in documents under the custody of The Directorate of State Archives in Kolkata. These files show decades of surveillance in the lives of these activists, manifesting the colonial state’s desire for meticulous documentation. Categorising and mapping the population in attempts to transform chaotic realities of the colonised into manageable data points, these files reduce complex narratives to only those aspects deemed relevant for control. Writing in the context of the peasant insurgencies in the nineteenth century, Ranajit Guha reveals the dangers of such generalisations that discount the subjective agency of the peasants: ‘By making the security of the state into the central problematic of peasant insurgency, it assimilated the latter as merely an element in the career of colonialism. In other words, the peasant was denied recognition as a subject of history in his own right even for a project all his own.’

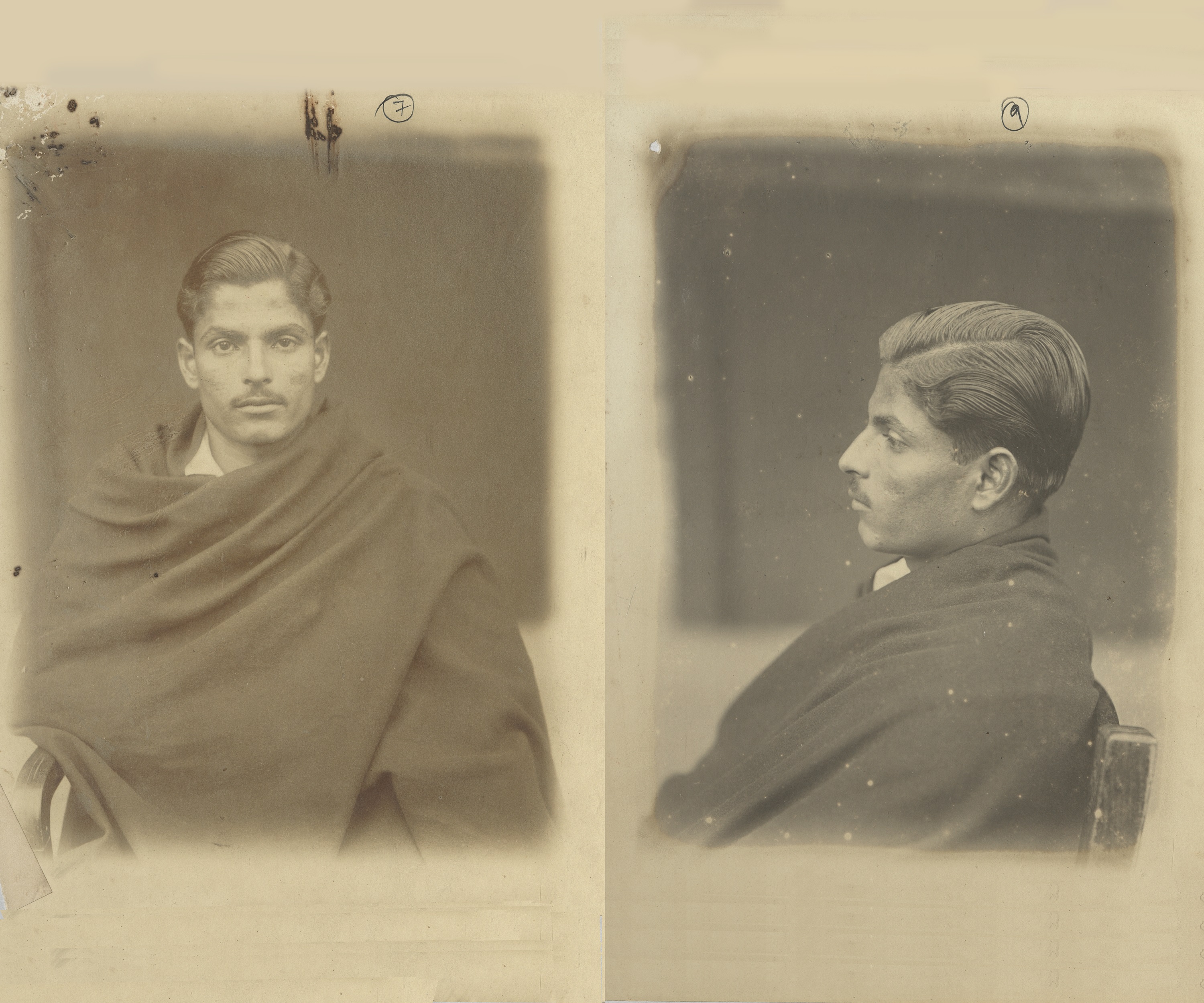

Mugshot of Mani Krishna Sen. File 890/31 under the custody of Directorate of State Archives.

The archive's ability to reduce all potential subjects to a single code of equivalence was facilitated by the precise metrics of the camera, merging optics with statistics. Strongly influenced by phrenological theories, the mugshot, along with its annotations, was designed to enable the camera to distinguish criminals physiognomically, ethnically, and racially from law-abiding citizens.

While Hore's portraiture elevates Sen to the honoured realm of an iconic and courageous leader, injured while fighting for the success of the Tebhaga movement, the police mugshot freezes him into an image of a ‘terrorist’, transforming him into a body in time, an object of scrutiny and suspicion.

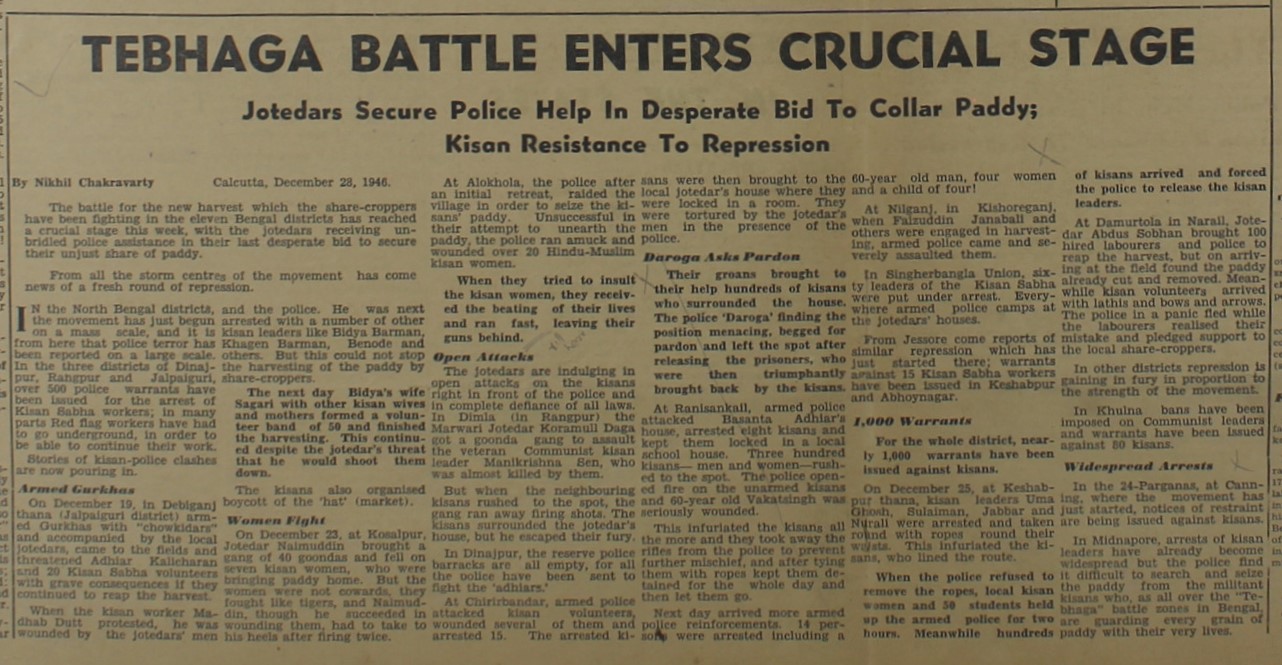

People’s Age, January 5, 1947. Collection: P.C. Joshi Archives

|

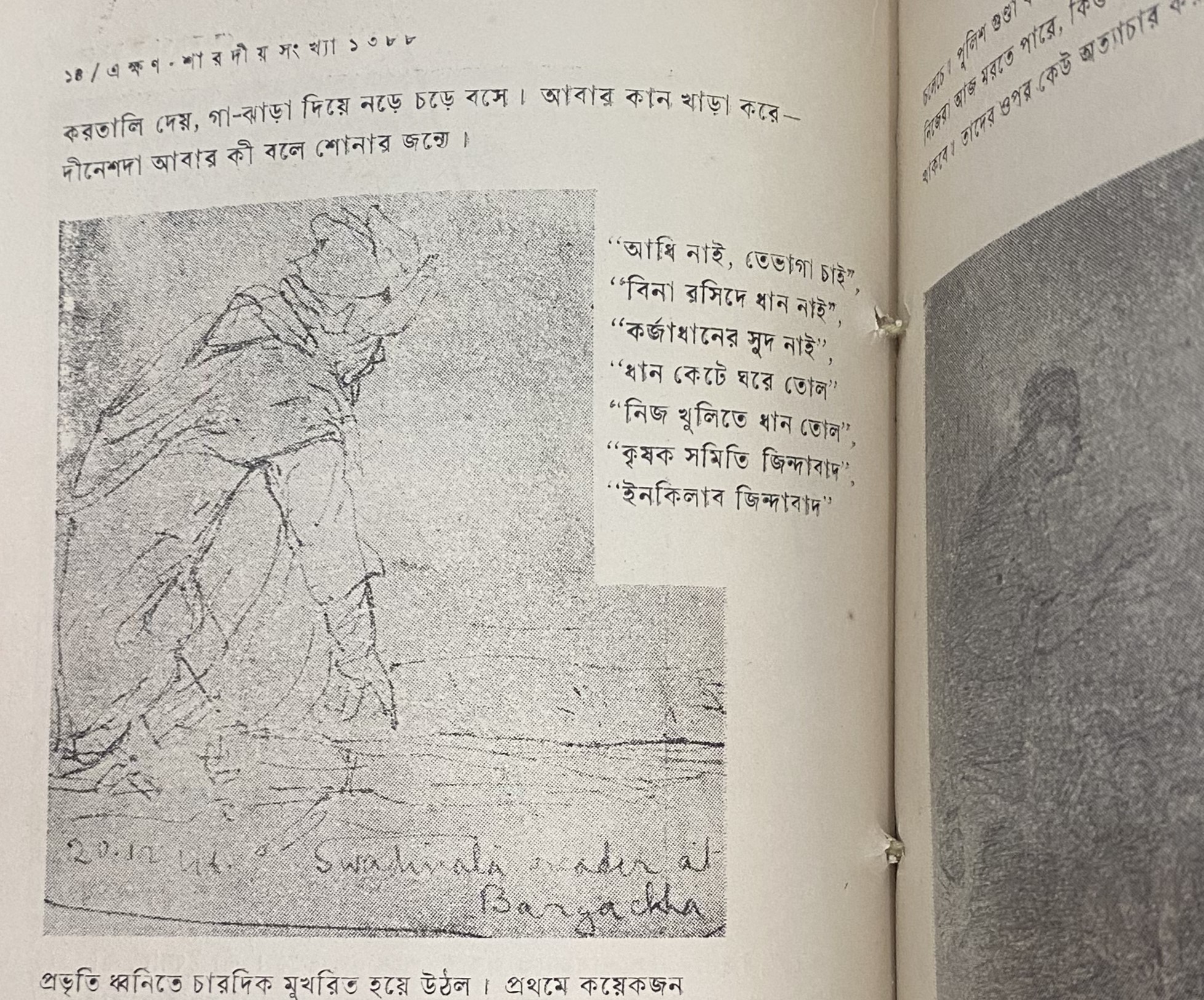

‘Swadhinata reader at Bargachha'. Saradiya Ekshan, 1981, Little Magazine Library, Courtesy: CSSSC archives. |

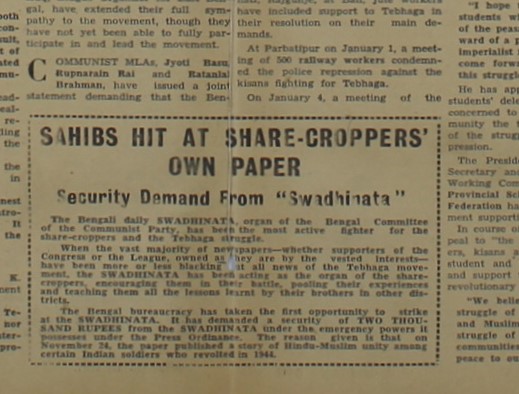

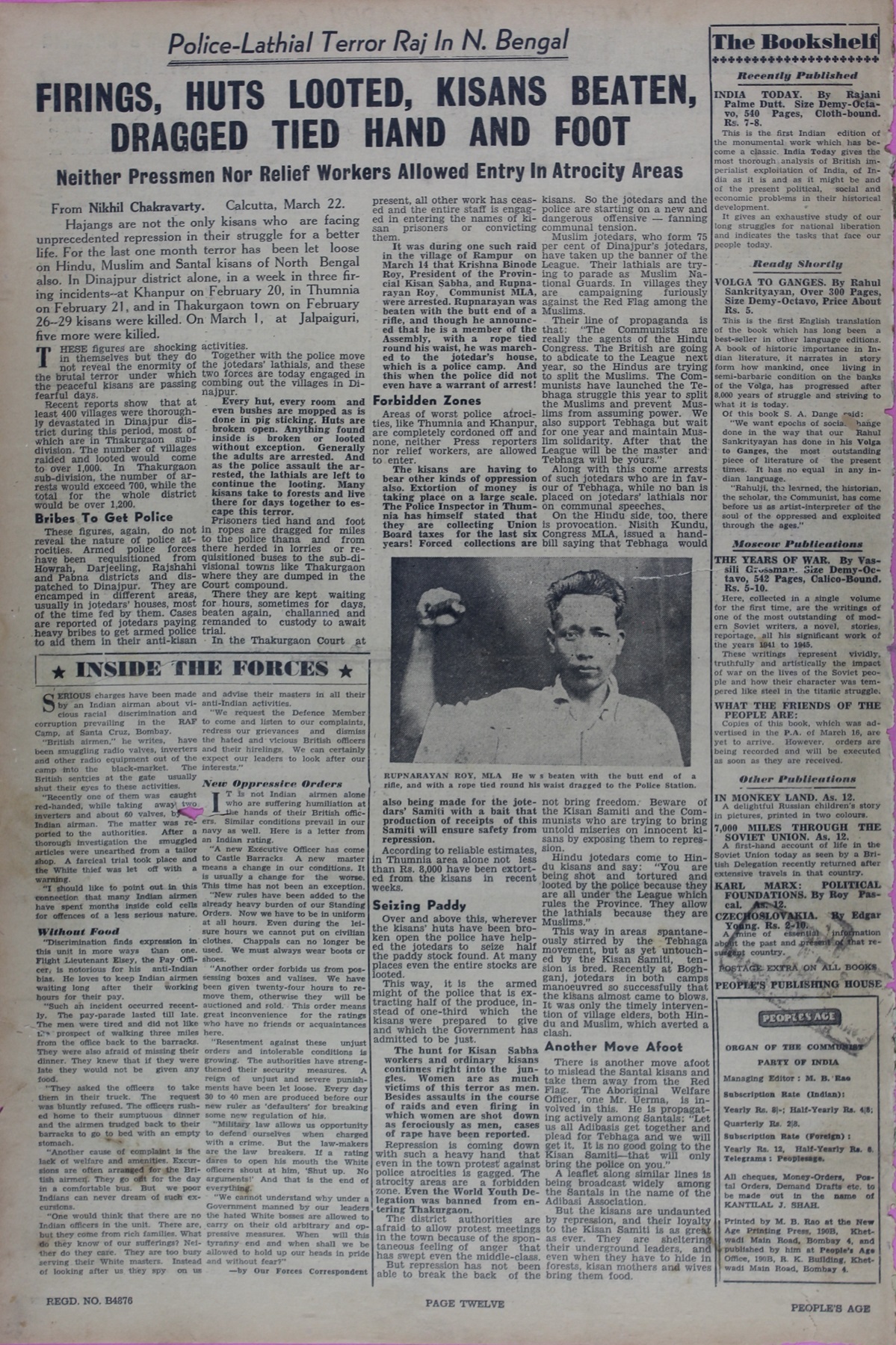

Counter-mainstream newspapers like ‘People’s War’ (later ‘People’s Age’), which extensively documented the famine and subsequent agrarian movements such as Tebhaga, played a crucial role in ensuring these events were not relegated to the obscurity of impersonal records. As a young party worker, Somnath Hore used to look up to Chittaprosad, and draw blown-up versions of his cartoons published in the ‘People’s War’, that were to be pasted on trees in various public spheres. It being a general feeling amongst Tebhaga activists that newspapers such as Ananda Bazar Patrika were failing to cover the movement, the ‘People’s Age’ along with ‘Swadhinata’ (organ of the Bengal Committee of the Communist Party), bound the world of sympathising communists together.

Santi Sanyal’s letter revealing importance of People’s Age. File 263-47 under the custody of Directorate of State Archives.

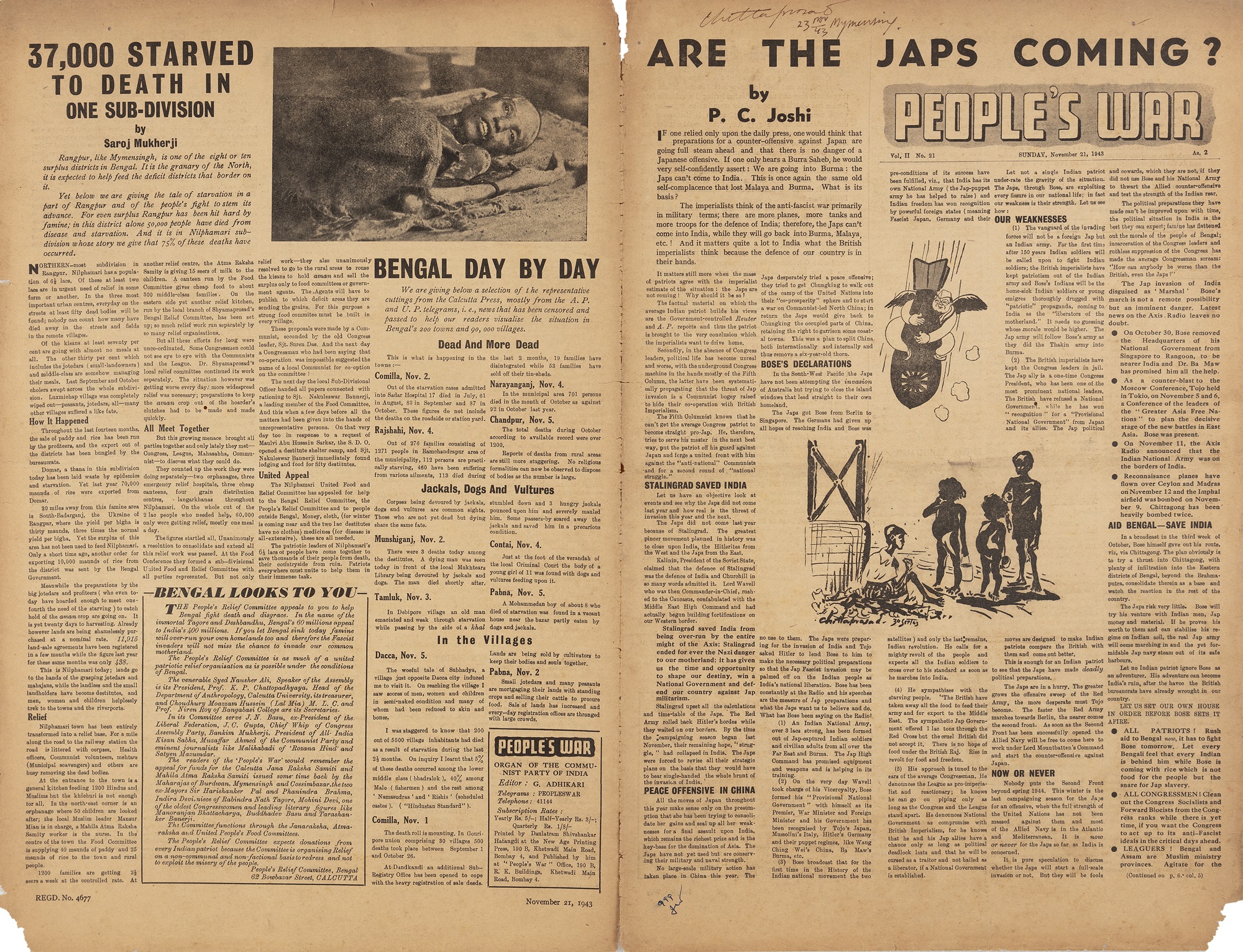

People’s War. November 21, 1943. Collection: DAG Archives

|

People’s Age. January 19, 1947. Collection: P.C. Joshi Archives. |

Abani Bagchi, a recurring character in Somnath Hore’s diary, would note that the Ananda Bazar Patrika went on to publish the fact that ‘A sovereign rule has been established in Dimla Thana... Their forces are capturing villagers, conducting trials, and meting out punishments. They have created a reign of terror.’ Reading this, he went on to note, ‘It was clear to the section of the movement who were aware, that an armed attack from the police... is imminent.’

People’s Age. March 30, 1947. Collection: P.C. Joshi Archives.

The Tebhaga movement, despite its initial hope and later atrocities, would have a lasting influence on Somnath Hore's artistry. Specific details would fade, forms would disappear, leaving only visceral impressions shaped by his evolving subjectivity. In revisiting this moment in history, affective testimonies like his fill crucial gaps in dominant historiographical methods, such as the State Archive documents, and give voice to the subaltern, whose conscious intentions and motivations are often overlooked or written over. By creating inner dialogues and contradictions, each perspective, with its unique layer of meaning, contributes to a polyphonic understanding of the past and gives us access to the larger experiential environment of the Tebhaga Movement, which became a ground for conflict and progress.

Somnath Hore, Untitled, Etching on handmade paper, 5.7 X 7.0 in. Collection: DAG

Further reading:

Somnath Hore. Tebhaga: An Artist’s Diary and Sketchbook. Translated by Somnath Zutshi. Seagull Books. 2022.

Manikrishna Sen. “Rangpurer Tebhaga Songram er Kotha”. In: Tebhaga Andolon. Edited by Dhananjay Ray. Ananda. 2019 Translations by the author.

Kavita Panjabi. “Aesthetics in the Making of History: The Tebhaga Women’s Movement in Bengal”. In: Puri, S., Castillo, D. (eds) Theorizing Fieldwork in the Humanities. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. 2016.

Ranajit Guha. Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India. Duke University Press. 1999.

Allan Sekula. “The Body and the Archive”. JSTOR. 1986.

Somnath Hore. My Concept of Art. Translated by Somnath Zutshi. Seagull Books. 2009

Abani Bagchi. “Tebhaga Songramer Amar Kahini”. In: Tebhaga Andolon. Edited by Dhananjay Ray. Ananda. 2019. Translations by the author.

related articles

Essays on Art

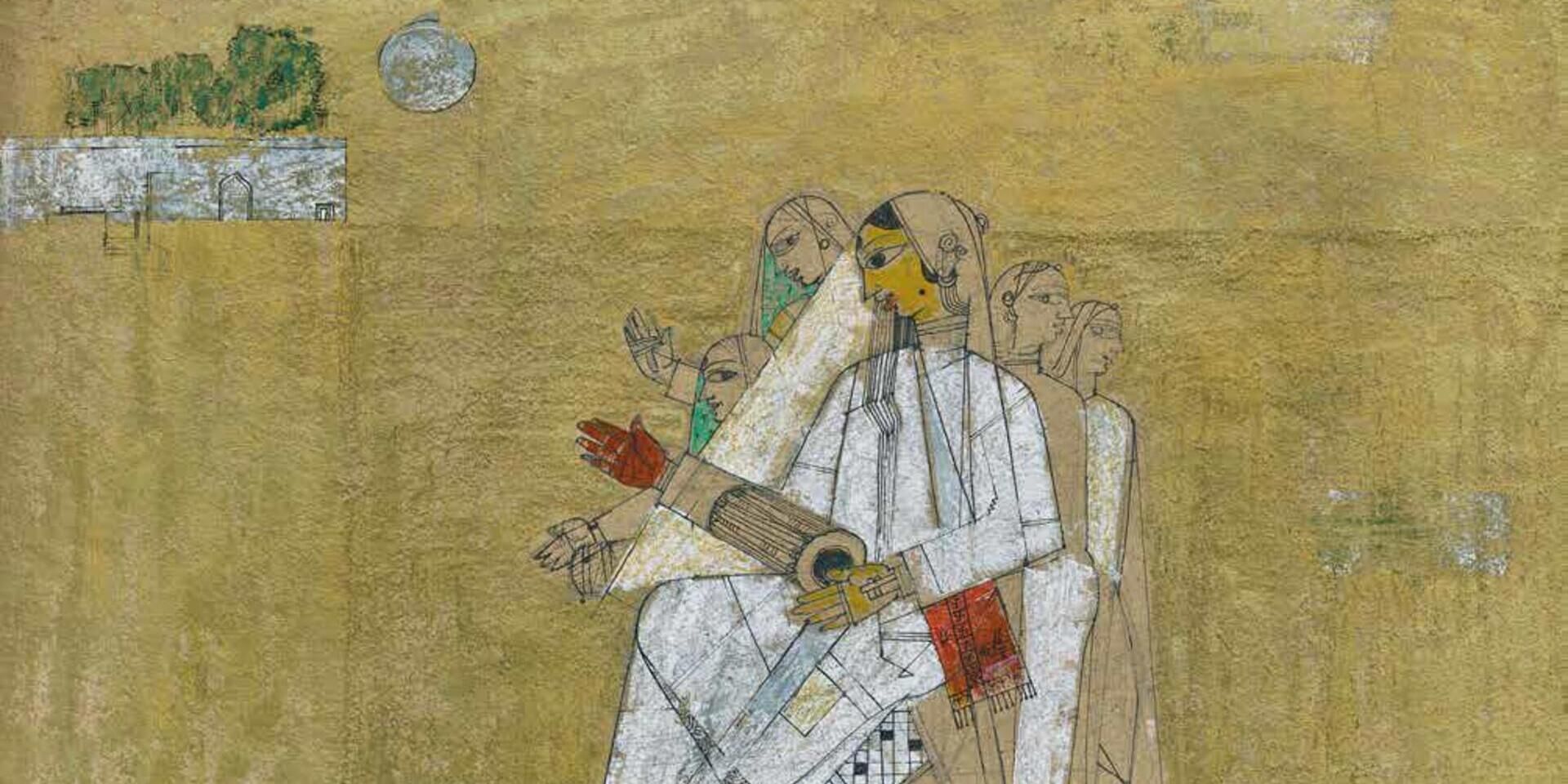

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

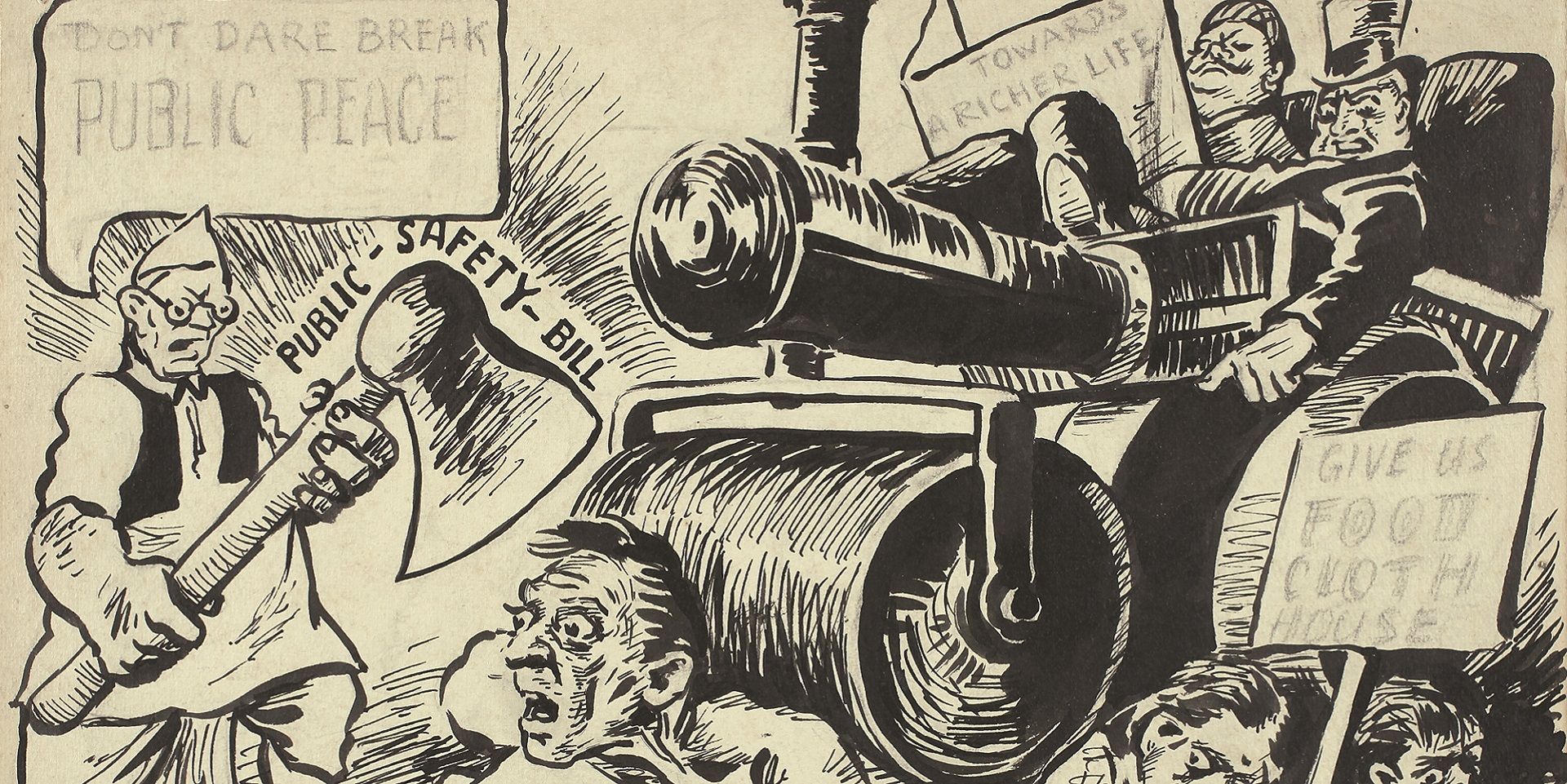

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

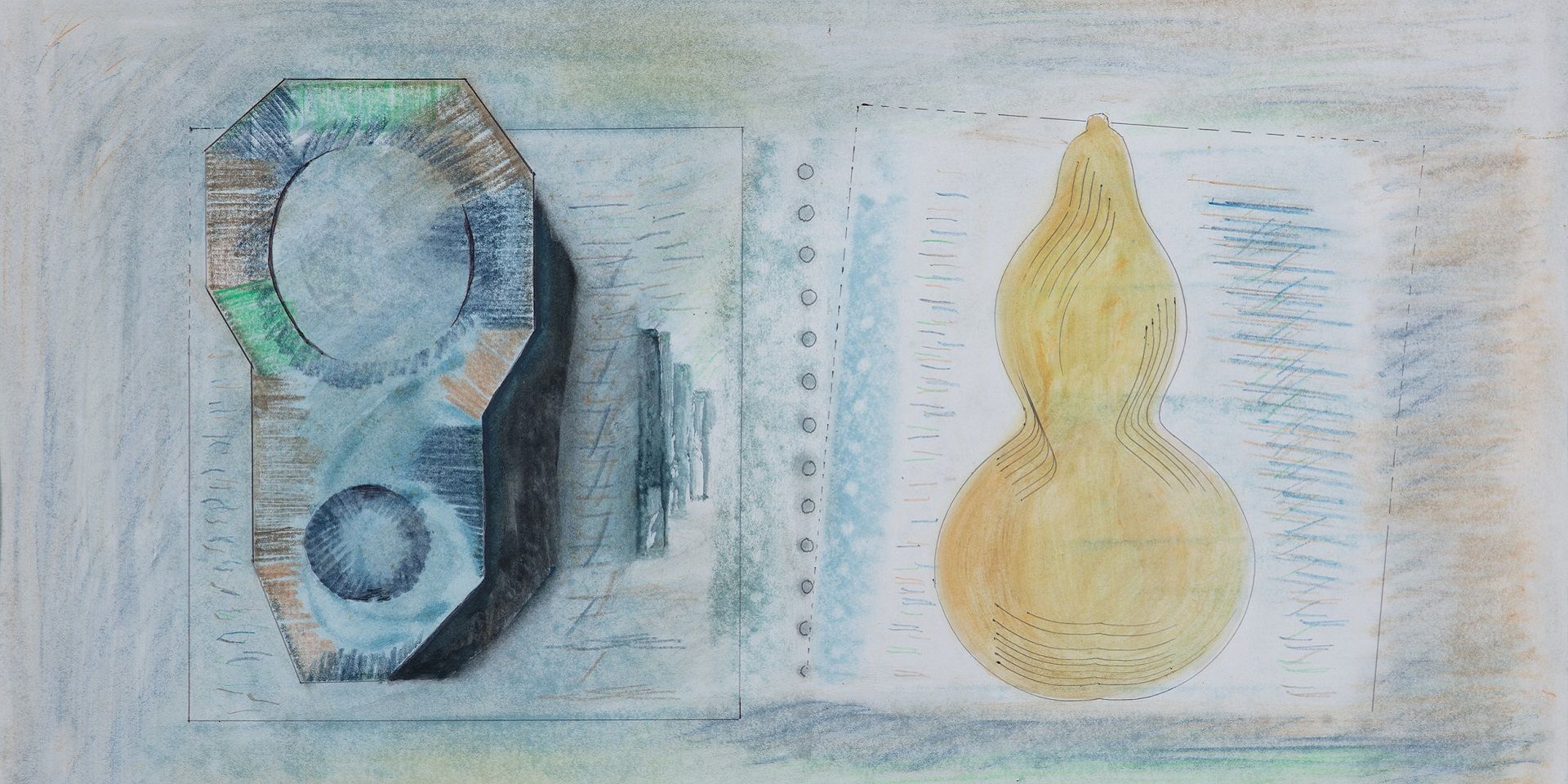

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

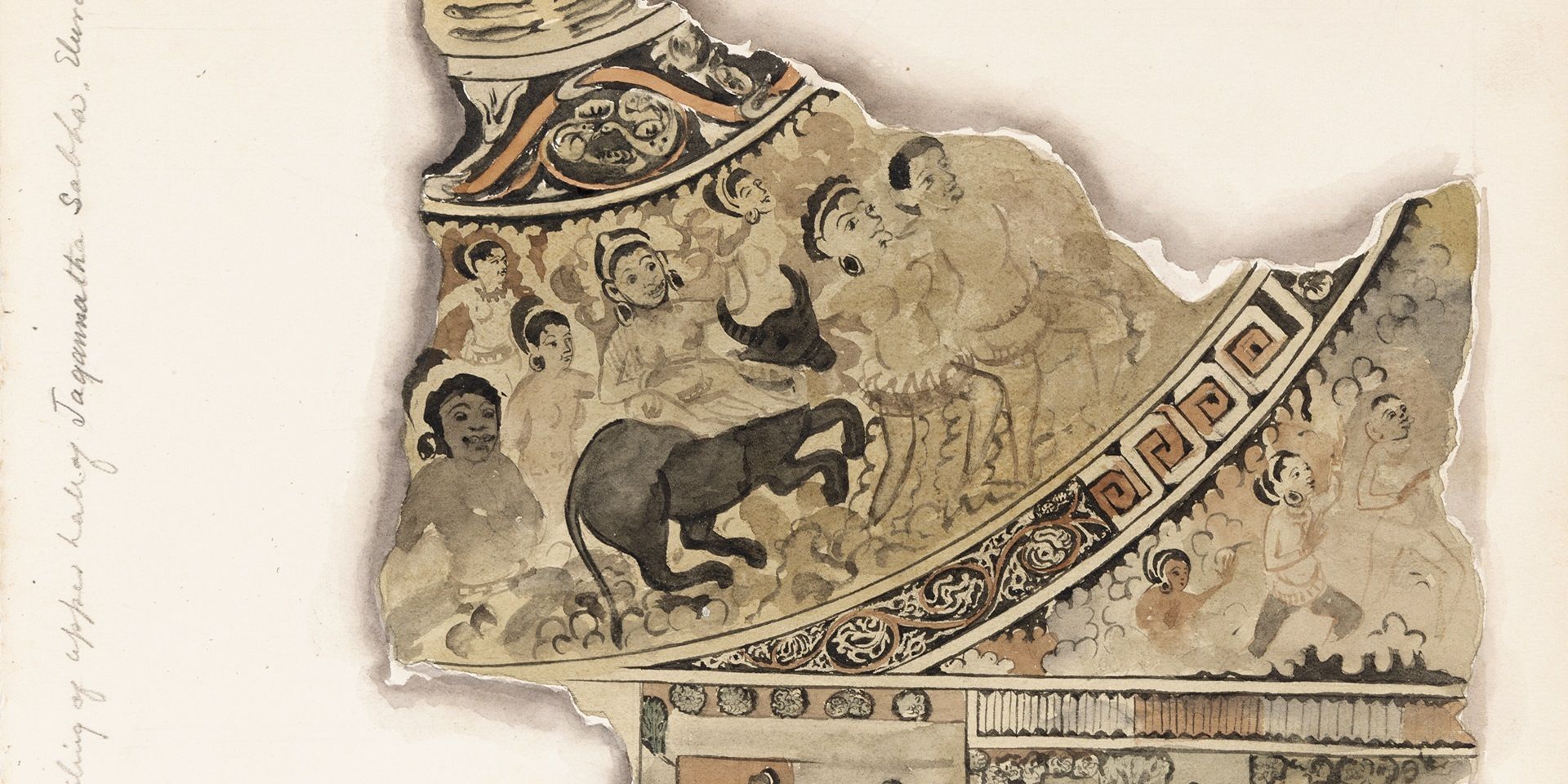

Archival Journeys

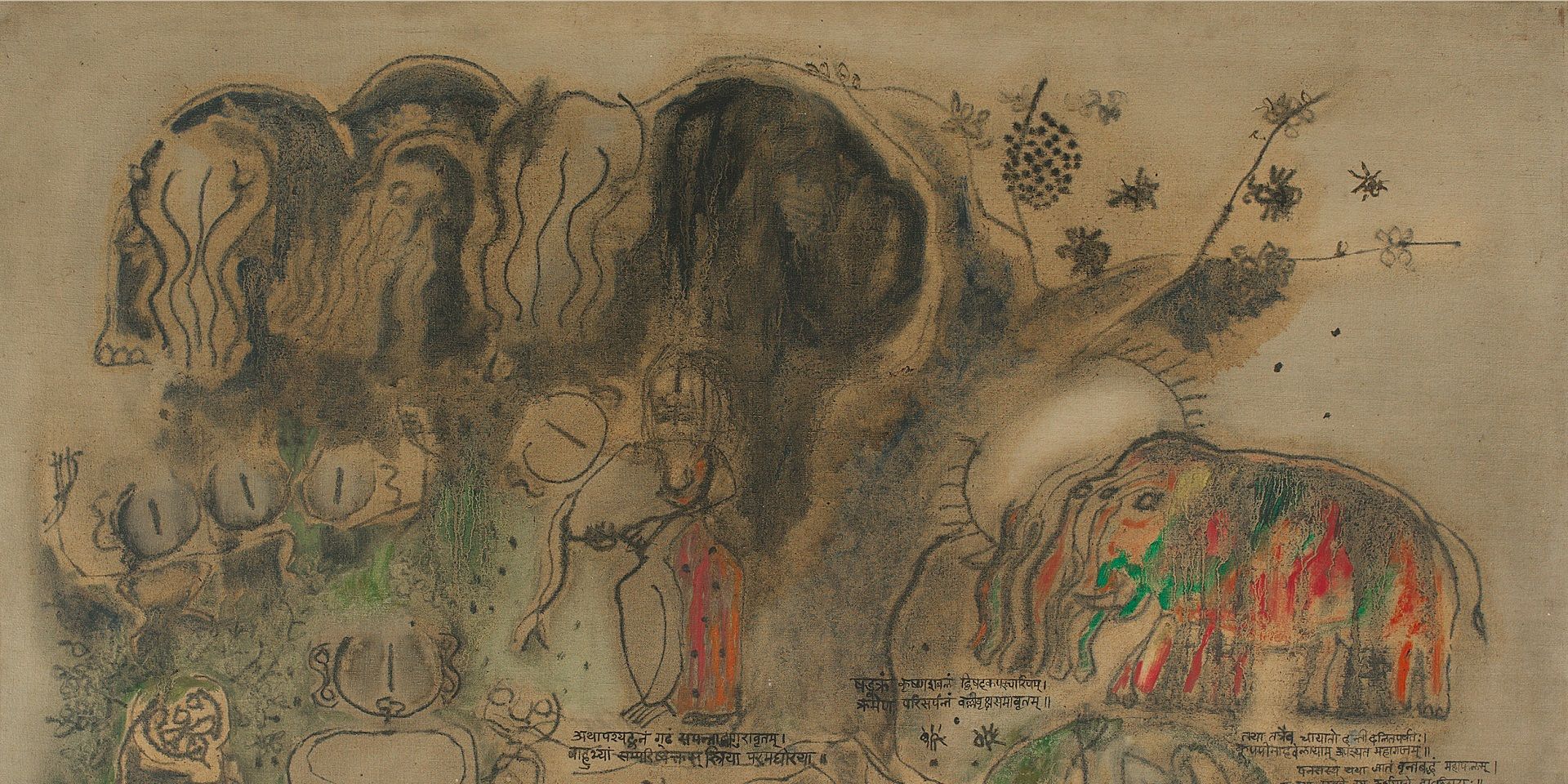

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024