Nirode Mazumdar: Dance Diabolical as a Route to Liberation

Nirode Mazumdar: Dance Diabolical as a Route to Liberation

Nirode Mazumdar: Dance Diabolical as a Route to Liberation

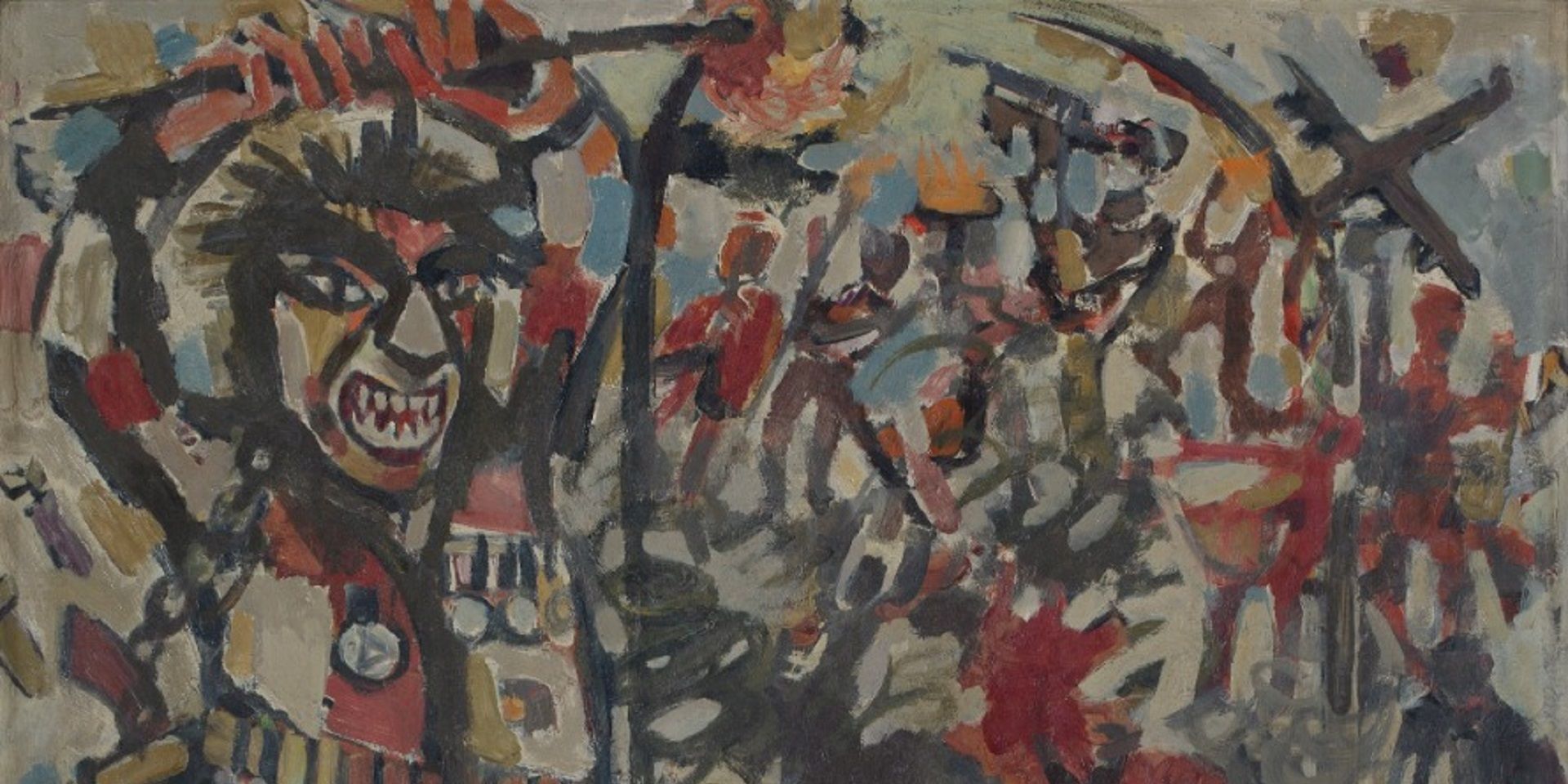

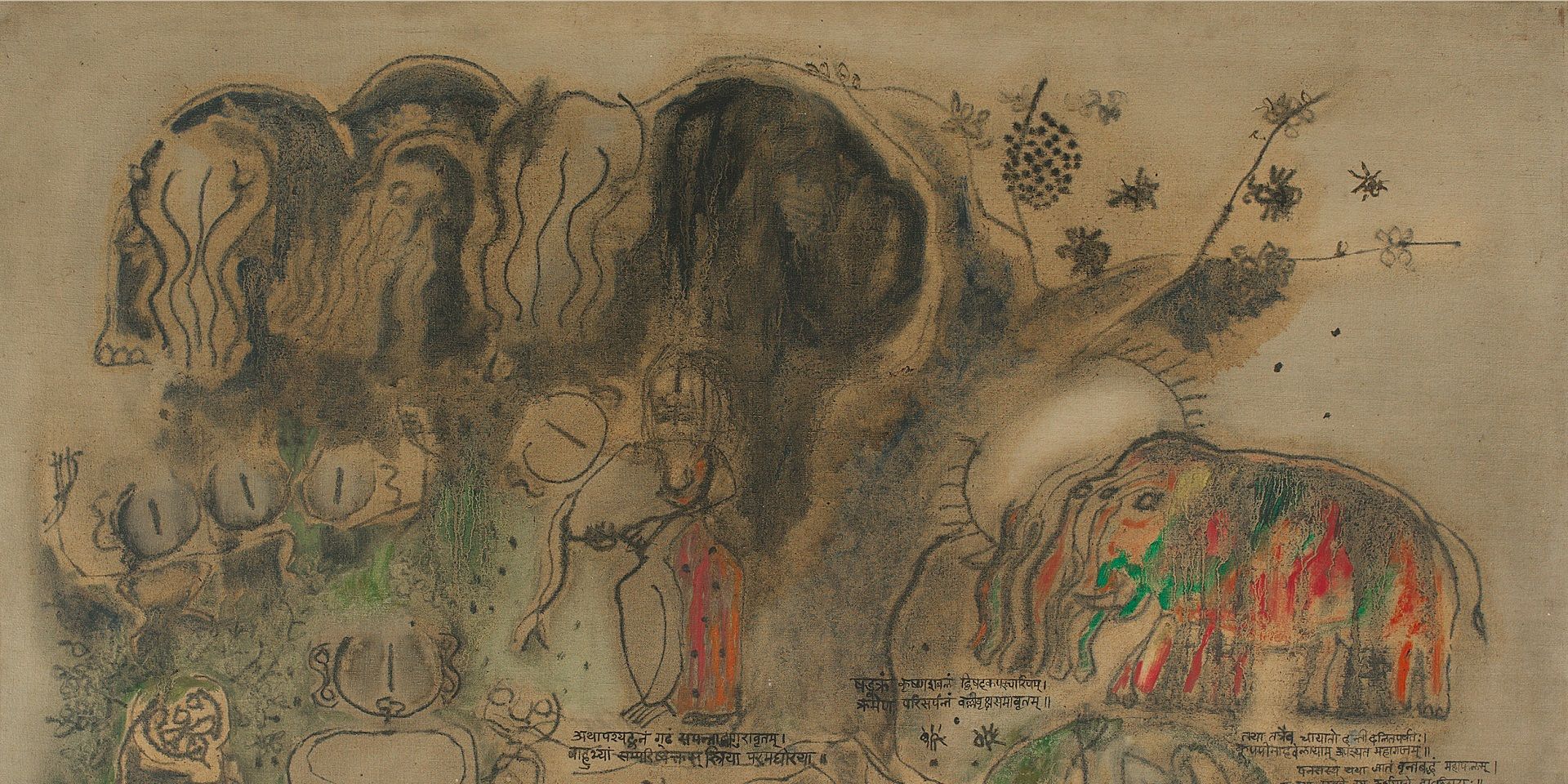

Nirode Mazumdar, Diabolical Dance (detail), Oil on hardboard, 1970-74, 47.0 x 34.7 in. Collection: DAG

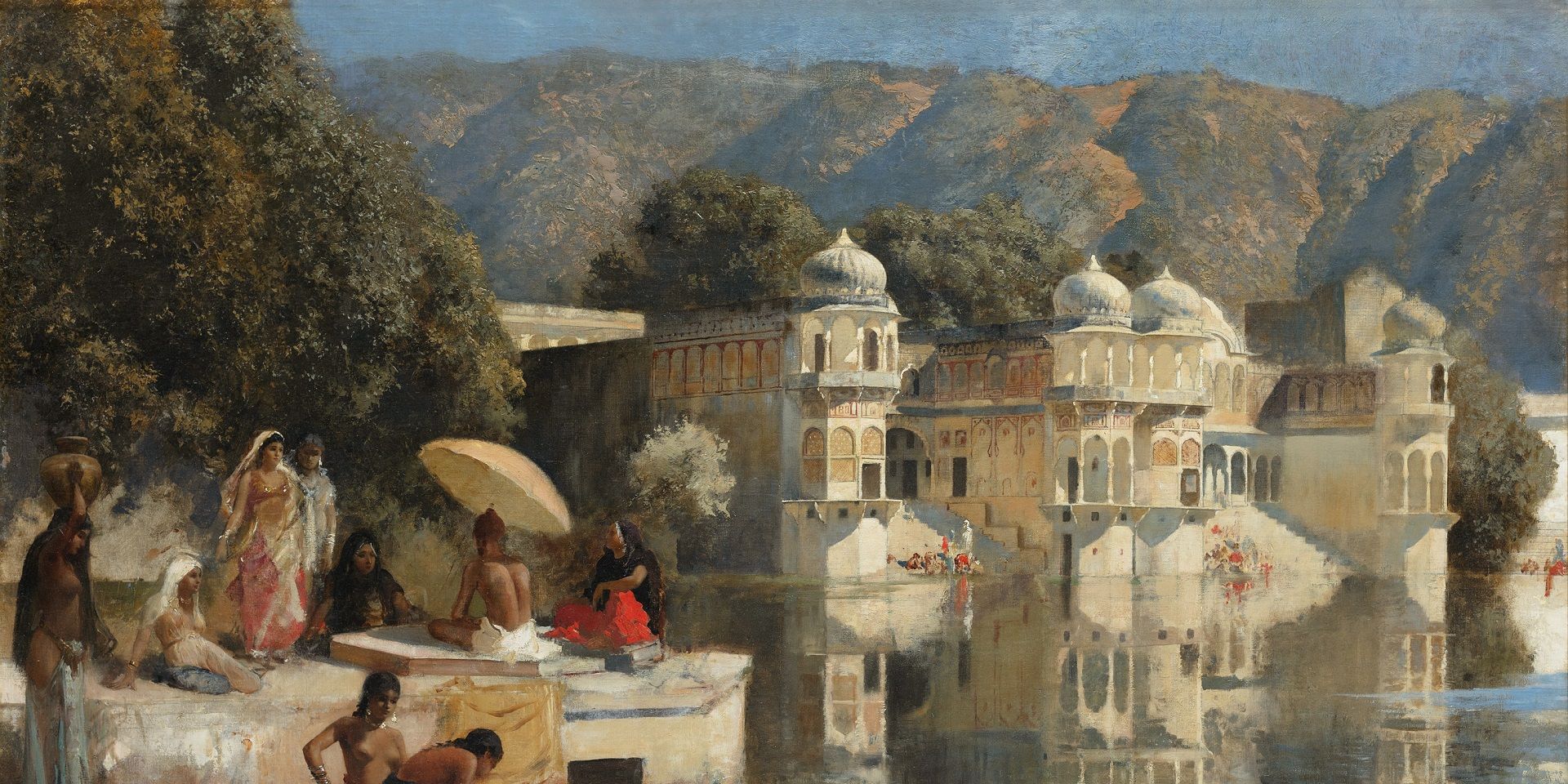

On the occasion of DAG's historic exhibition Kali: Reverence and Rebellion, we take a deep dive into one of the most fascinating works in the exhibition. Madhu Khanna, one of the foremost experts on tantra and modern art, explores the dark netherworld unleashed by Nirode Mazumdar's depiction of the goddess Kali in Boitoroni.

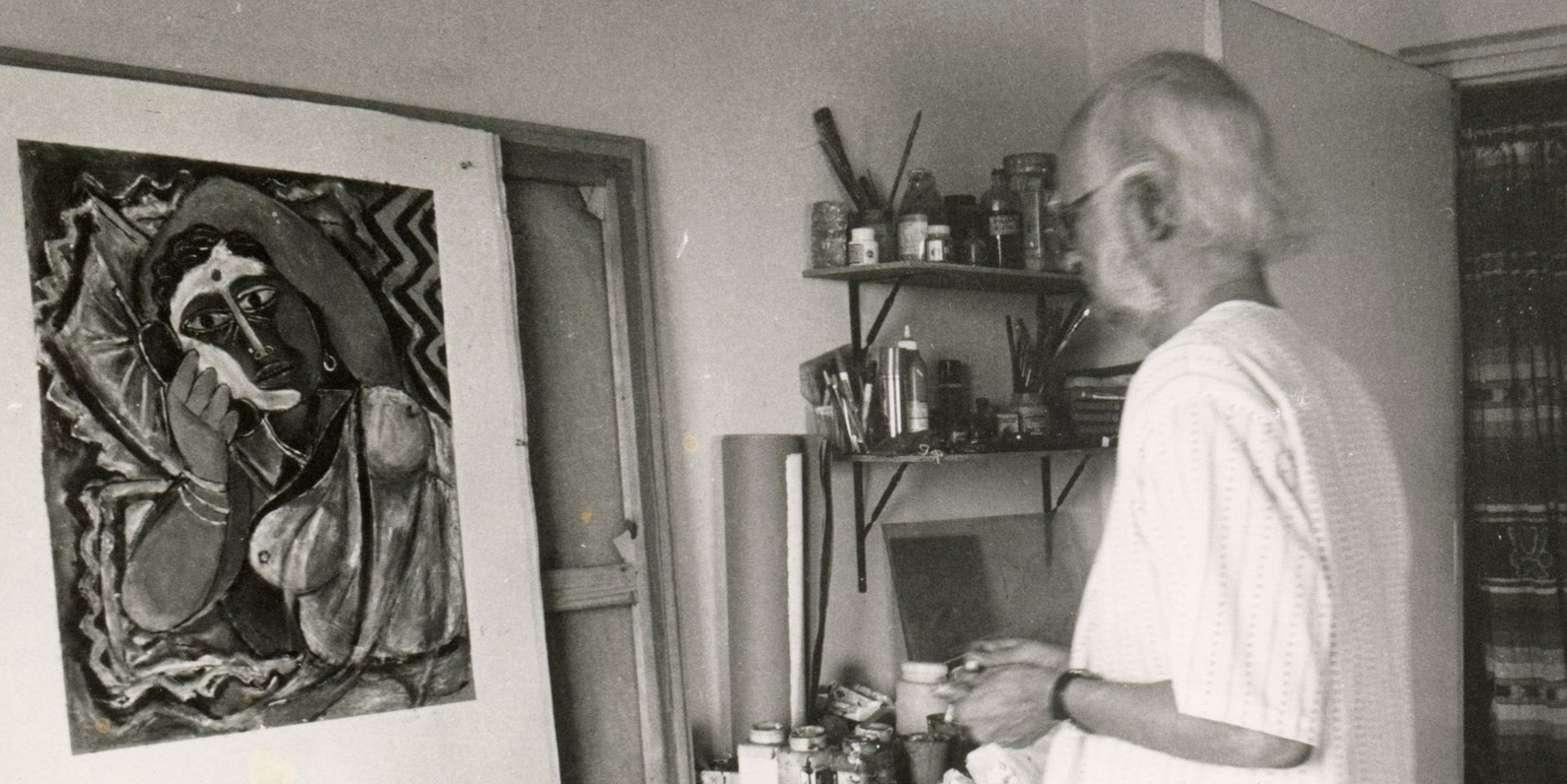

Nirode Mazumdar’s Diabolical Dance is a remarkable painting by a significant painter of the twentieth century. Widely known in his native Bengal as a titan of twentieth-century modernism, he was also a founder of the little-known Calcutta Group of modernists. In the late 1940s, he received a scholarship to Paris, where he was exposed to the great artists Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Constantine Brancusi. Mazumdar stayed in Paris for over a decade and participated in various exhibitions there.

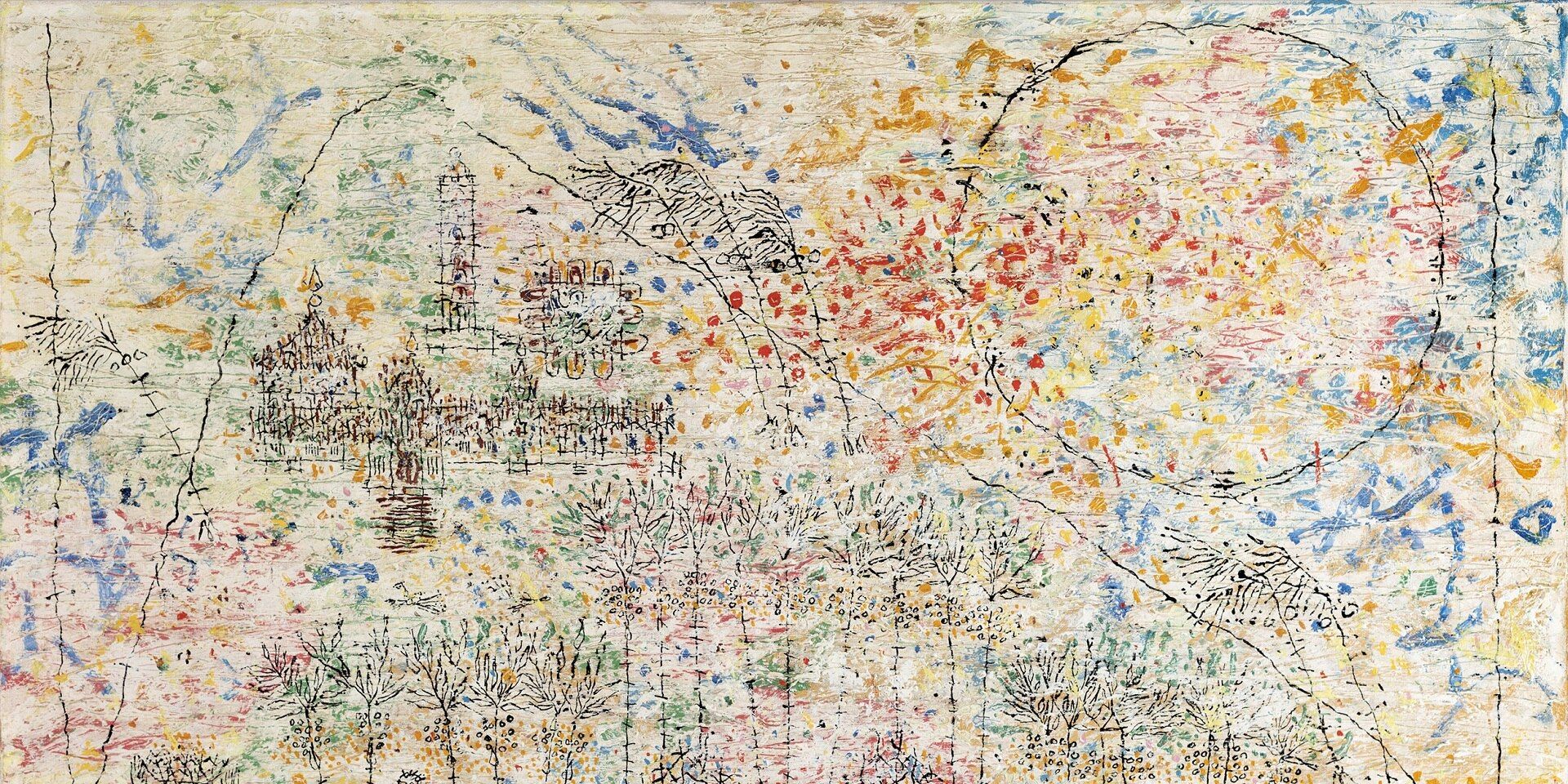

The 1970s was a golden period when his style achieved the perfection he sought from it. His expression was international; his works showed an apparent influence of European modernism; simultaneously, they were also rooted in his Bengali origins. The painting under discussion was probably exhibited, among others, in a solo show at the Academy of Fine Arts, Calcutta, as a part of his Boitoroni series.

|

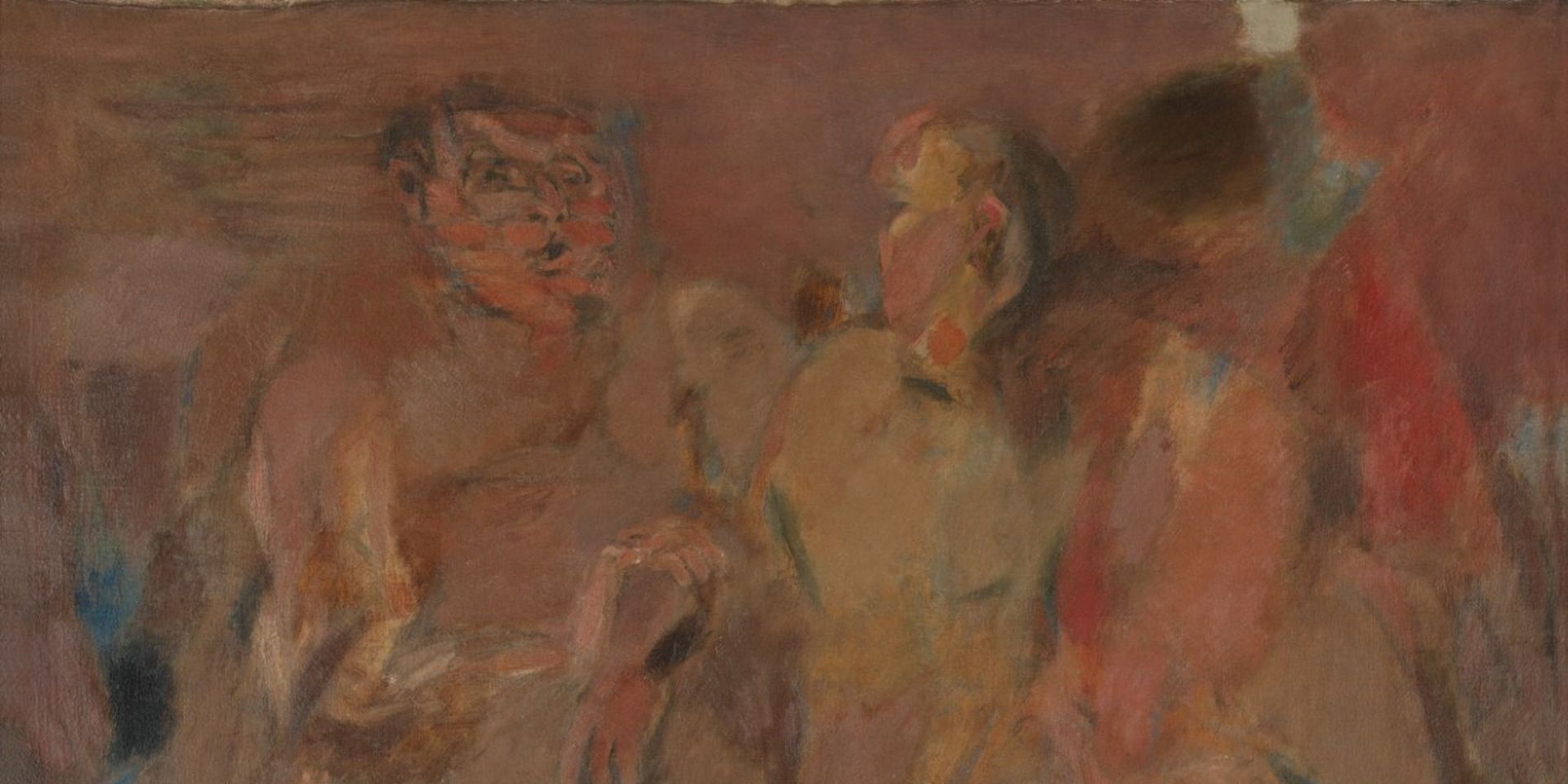

Nirode Mazumdar, Diabolical Dance (detail), Oil on hardboard, 1970-74, 47.0 x 34.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Mazumdar drew his inspiration from a variety of performative and mythical genres. Foremost among these was the imagery of dance and its association with Goddess Kali. In all ancient cultures, dance is an expression of the earliest art form moved by a transcendent power. Before humans expressed their life experiences using chalk or paint, their bodies released a rhythmic energy that served as a medium of expression. Primal tribal societies still dance on every occasion as an expression of their joy, grief or fear. According to the Hindu worldview, Lord Shiva creates and sustains the world; dancing destroys all matter as he dances with the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and ether. This dance of the god creates a manifold world of tangible matter, and with the same force he pulverises and reduces it to ash. It is, therefore, believed that the cosmos is his theatre. In the cyclic act of dancing, Shiva assumes his manifestation as Nataraja, the King of Dance, spewing out an aureole of fire that forms a circular girdle around the icon—an image that has become a classical embodiment of the grace as well as wrath of the Lord as a dancer.

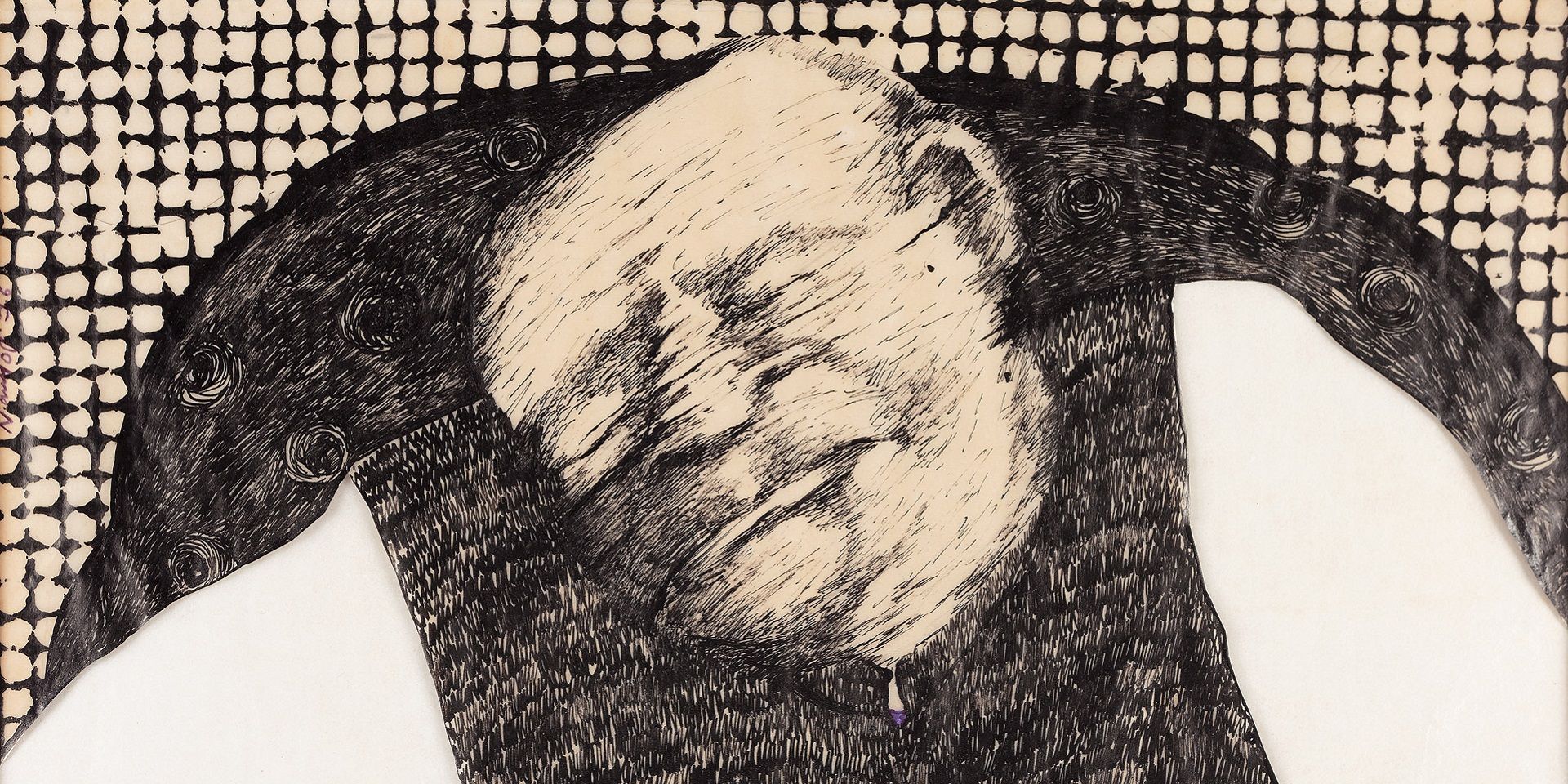

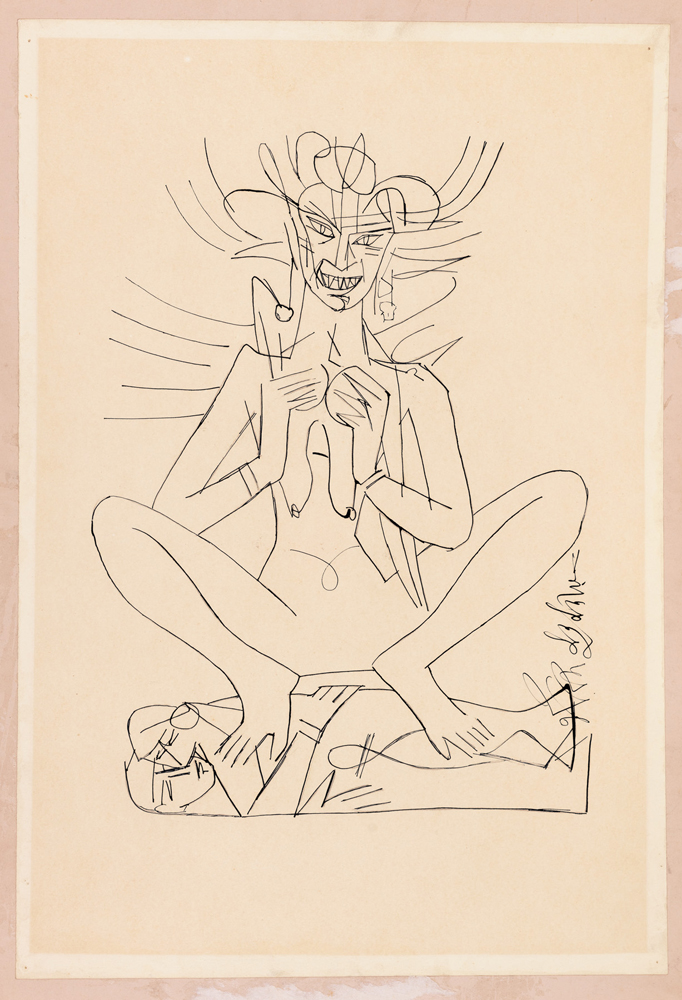

Nirode Mazumdar invokes a similar imagery in this painting. Diabolical Dance is an exemplary work which recalls several elements of Kali’s fierce manifestation. In the painting, the mystic nativity of the loving, benign mother goddess replaces her fierce personification as one who performs, like Shiva, the vigorous and thunderous dance of death. In order to understand the significance of its symbolism, we return to Shiva’s divine dance of destruction as described in the Natyashastra and appropriated in Mazumdar’s painting through its symbolism. Shiva’s tandava has many aspects; performed to invoke a serene and joyous mood (Ananda-tandava) or performed in a violent mood (Rudra-tandava) which is described as a vigorous dance with a brisk movement of feet and a variety of hand gestures that symbolise the cyclic act of creation and destruction.

|

Nirode Mazumdar, Diabolical Dance (detail), Oil on hardboard, 1970-74, 47.0 x 34.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Bengali folk religion creates a unique sub-culture in a festival known as Kali Nach, an ancient ritualistic performance of the tandava by Kali. Here, Goddess Kali represents the cycle of time. Her props, a khanara or book of omens, and a curved sword are essential elements. Gripping the khanara, she swings it vigorously to show her might. Accompanying her is another dancer who assumes the role of Shiva as Mahadeva. While Shiva lies prostrate before her, Kali performs rapid kinetic postures, unleashing her horrendous power. As she dances, the spectacle becomes increasingly turbulent. The moving khanara adds to her wrathful nature, representing the chaotic face at the moment of the world’s destruction.

In the painting, the performer is depicted as grotesque, ugly, and fearsome to create a dark mood. Painted masks peer out. At the same time, the drum beats highlight the impact and capture the moment of the virulent, bloodthirsty dance of Kali in the vigorous brushstrokes of the two figures, a dancer adorned with a monstrous mask and another figure by her side. This painting represents rage, frantic power, and the bursting of pent-up emotions. The gaping mouth with fangs appears ready to devour whatever appears before it. A host of chaotic, frenzied figures, small in size, recede into the background.

Boitoroni (Vaitarini in Sanskrit) is the river of life, knowledge, and judgement, described in Hindu and Buddhist scriptures and forming a part of the corpus of Vaishnava literature. The Garuda Purana describes the river that flows between the earth and naraka (hell), or Yamaloka, the abode of Yama, the god of death. The river is the realm of hell where the departed souls who have transgressed the divine law undergo severe torture. It lies in the underworld of the south of the universe. The righteous experience the river flowing with nectar-like water, but it is frightening for sinners.

Nirode Mazumdar, Diabolical Dance (detail), Oil on hardboard, 1970-74, 47.0 x 34.7 in. Collection: DAG

In the Buddhist Jatakas written in the Pali language (300 B.C.), Nimi, the righteous king, was led by Matali to behold the wonders of the cosmos during which he saw that sharp knives and weapons lie beneath the waters and its habitants are those who are guilty of sins on earth. The unrighteous need to purify and cross the river Boitoroni, which is full of filth, pus, and blood, vultures, fish, bones, and crocodiles with needle-sharp teeth, and is in constant turbulence (Garuda Purana, Preta Khanda 5). The psychopomps of the river ferry the souls of the dead across the river. Only the righteous cross over without pain.

The imagery of the painting is complex because it weaves a variety of symbols in the short compass of the canvas: the dance, the goddess, and the river’s underlying moral or social significance. Mazumdar renders a pictorial allegory of the destructive fury of Kali’s diabolical dance. The imagery is dense and multifaceted, peopled by frenzied, mutilated bodies in the background and two ugly figures, one standing and the other sitting in the foreground holding a weapon. The standing figure’s face has a ghoulish mouth, fanged teeth, and grizzly hair. Diabolical Dance provides the viewer with a peculiar mixture of revulsion, hostility, and conformity.

|

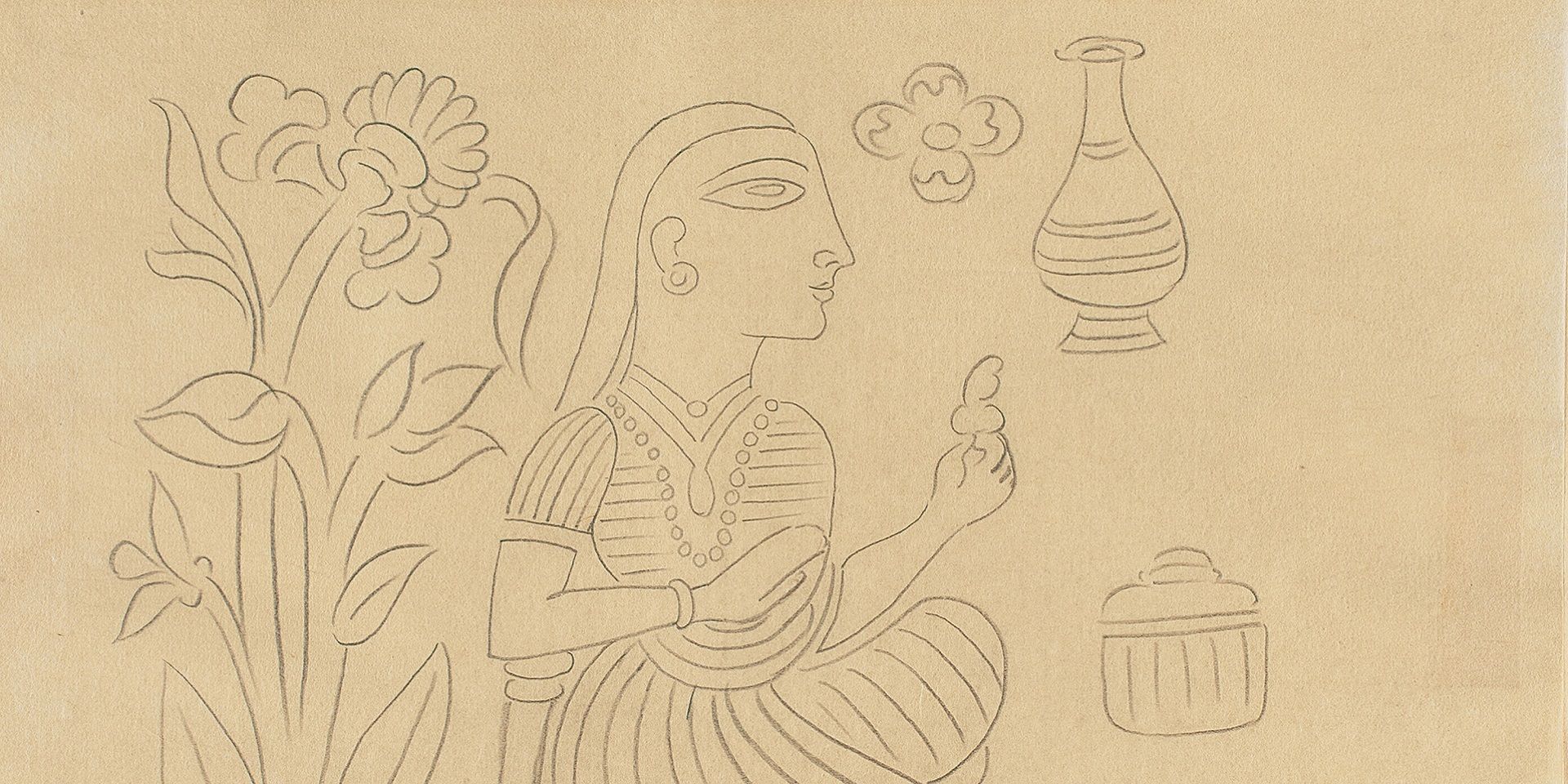

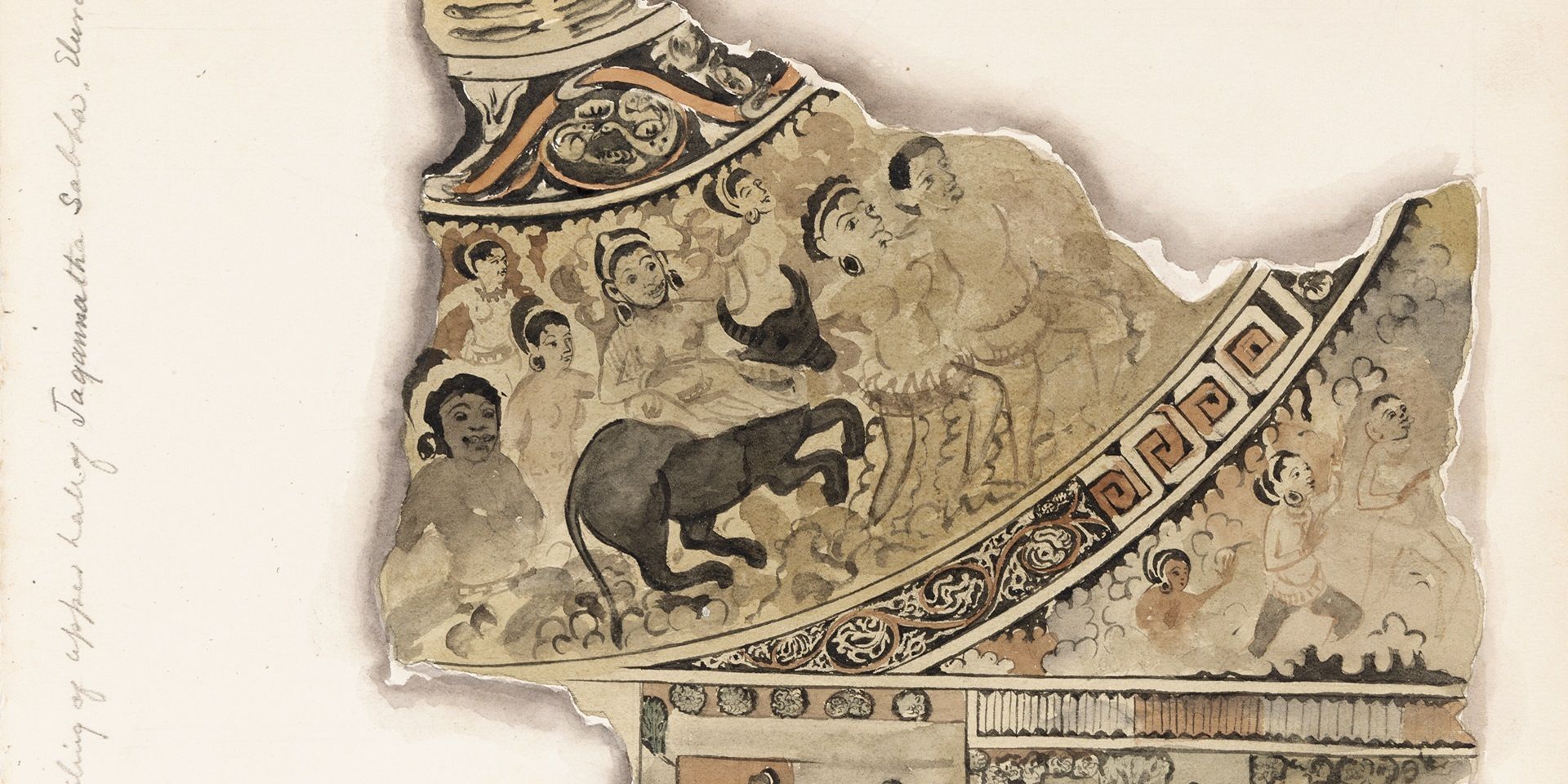

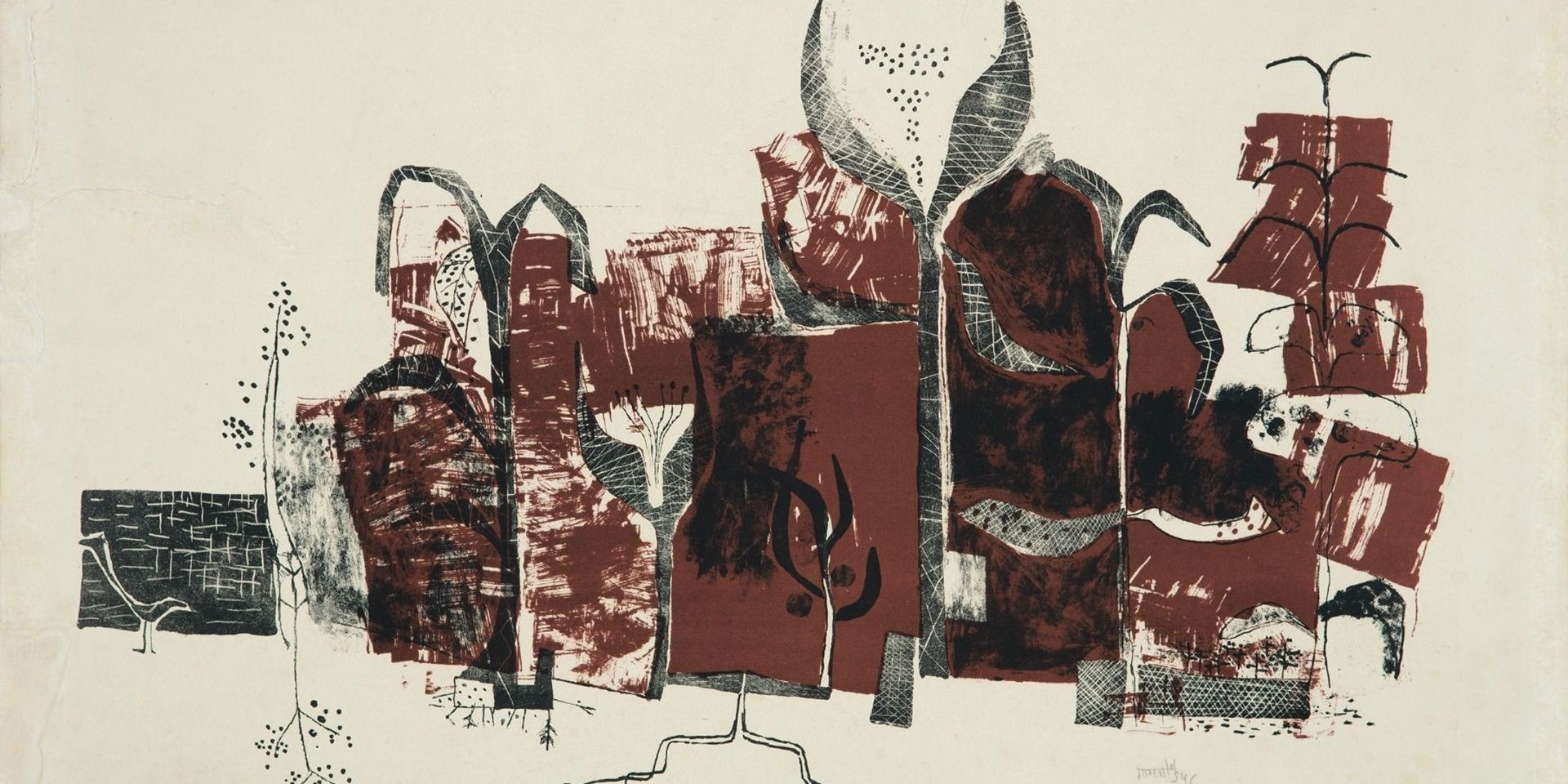

Nirode Mazumdar, Chamunda (Book- Drawings on Ramproshad Songs Series), 1967, Waterproof ink and graphite on mount board, 22.0 X 14.7 in. Collection: DAG |

In his works, Mazumdar uses fragmented brushstrokes that create complex fields. Daubs of colour define the contours of the figurative images. Muted greys, blues, and madder-red tones are favourites; he avoids harsh contrasts of light and shade. Short brushstrokes and broken daubs of colour are trademarks of most impressionistic painters. One can discern that the influence of shape and technique of this painting bears an impressionistic signature.

Nevertheless, Mazumdar’s vision, inspiration, and subjects are different from the European masters of impressionism. His inspirations and subjects were from India in which he portrayed the underlying structure of the objects he painted. The strokes of colour in the painting, though they appear chaotic, match the theme of fury. Each colour complements the chromatic composition to form a unity. His figures and images swirl in a flat space sans perspective, held up by the solidity and mass of colour.

Mazumdar’s quest to see beyond reality ultimately pushed him to dig deep into his Bengali roots. He was aware of the rich visual resources and folk narratives that were a part of Bengali consciousness. The goddess-centric tradition of the Dakshina Kali and the age-old symbols of tantric yantra and chakra had inspired him even as early as the 1950s when he first started to experiment with tantric imagery, long before the rediscovery of traditional tantra art in the 1970s.

Mazumdar reinterprets the narrative of Kali in purely visual terms, but the figures are not imitative of any storyline. This genre of expression is entirely his own. In this work, the artist challenges himself to reveal symbolic connotations based on all that is old as well as new. The painting is not an iconographic expression of the sacred image of Goddess Kali with her lolling tongue while holding weapons of destruction. This image suggests the horrific dance of protest which Kali performed to assert her supremacy over the patriarchal deities who had hijacked the public presence of an autonomous cult of female divinity. Postmedieval tantric literature brings the Shakta cult on par with those of Vishnu and Shiva. In a familiar myth from the Adabhuta Ramayana (chapters 23-24), the horrifying form of Mahakali dancing in visible anger is depicted with blood dripping on the battlefield over the corpses. The dance is so gruesome that Shiva bows down to pacify her rage and humbly submits to her. Kali then places her foot on his chest, proclaiming her victory over the male god. This form of dance of protest challenges male hegemony and asserts the gyrocentric victory of the Shakta cult.

Nirode Mazumdar, Diabolical Dance, Oil on hardboard, 1970-74, 47.0 x 34.7 in. Collection: DAG

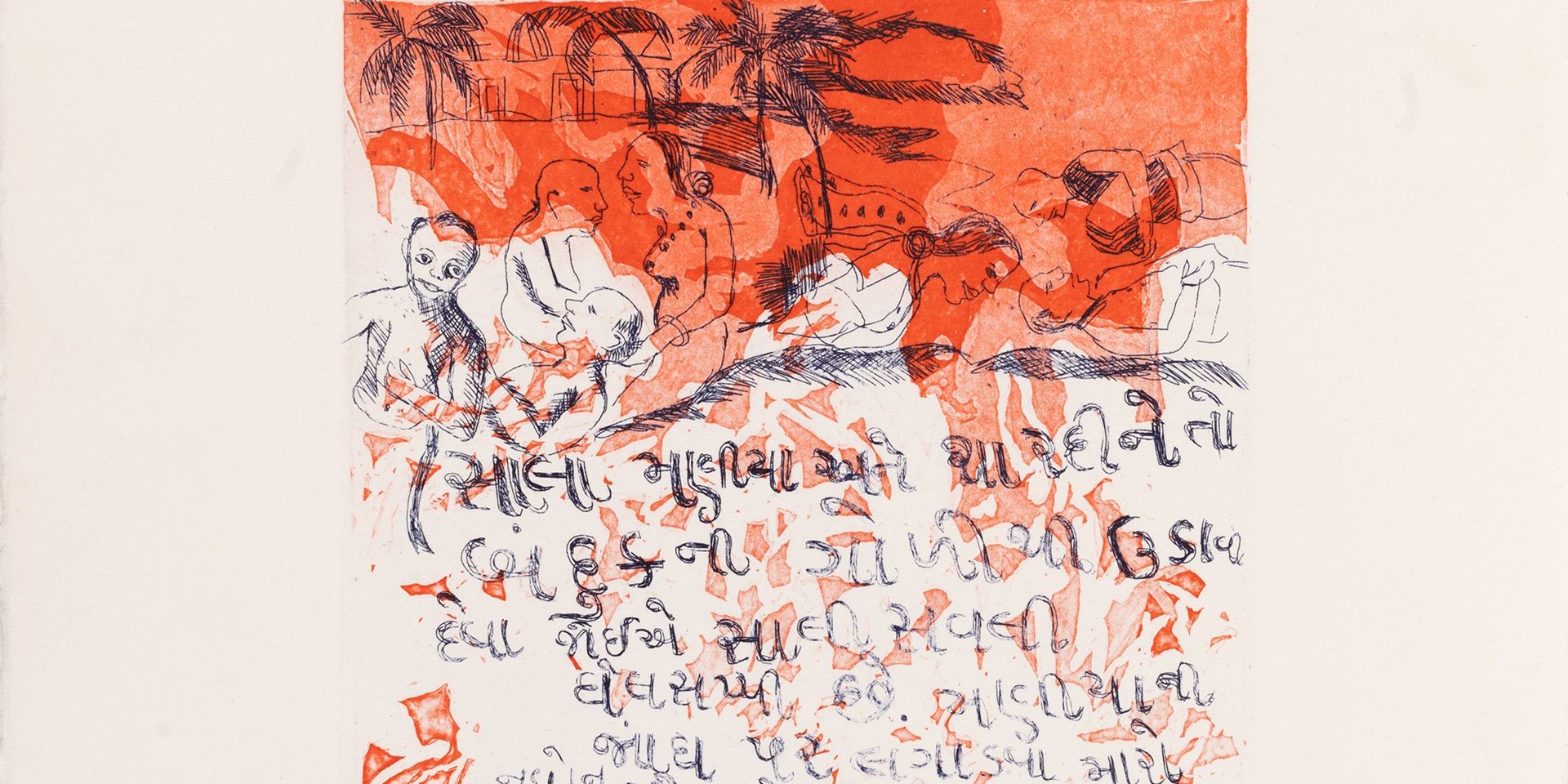

The painting also lends itself to another interpretation. Is it that Mazumdar was making a social statement and a period commentary of protest against the social ills of his time? We must not forget that he painted this work in the early phase of the post-colonial period, in the 1970s, when the veneer of the bourgeois was beginning to wear off. Bengal was under a grip of violence set off by people from low incomes exploited by the upper castes. The polity of liberal left ascent in Bengal occurred when the rest of India adopted the capitalist model of industrialisation. The underprivileged sections of society did not enjoy the privileges of the elite, reducing the role of the subaltern to passive submission. Diabolical Dance poignantly captures this frustration and may be read as a statement of protest against upper-caste hegemony mediated through the symbolic folk dance of Kali Nach. The imaginative folk narrative of the goddess’s dance recalls the conundrum of the age. The social scum of inequalities and social injustice are equated to the blood and pus of the mythical Boitoroni that a society needs to metaphorically cross to regain the dignity of humanitarian values of society. Diabolical rage is, thus, the route to liberation.

related articles

Essays on Art

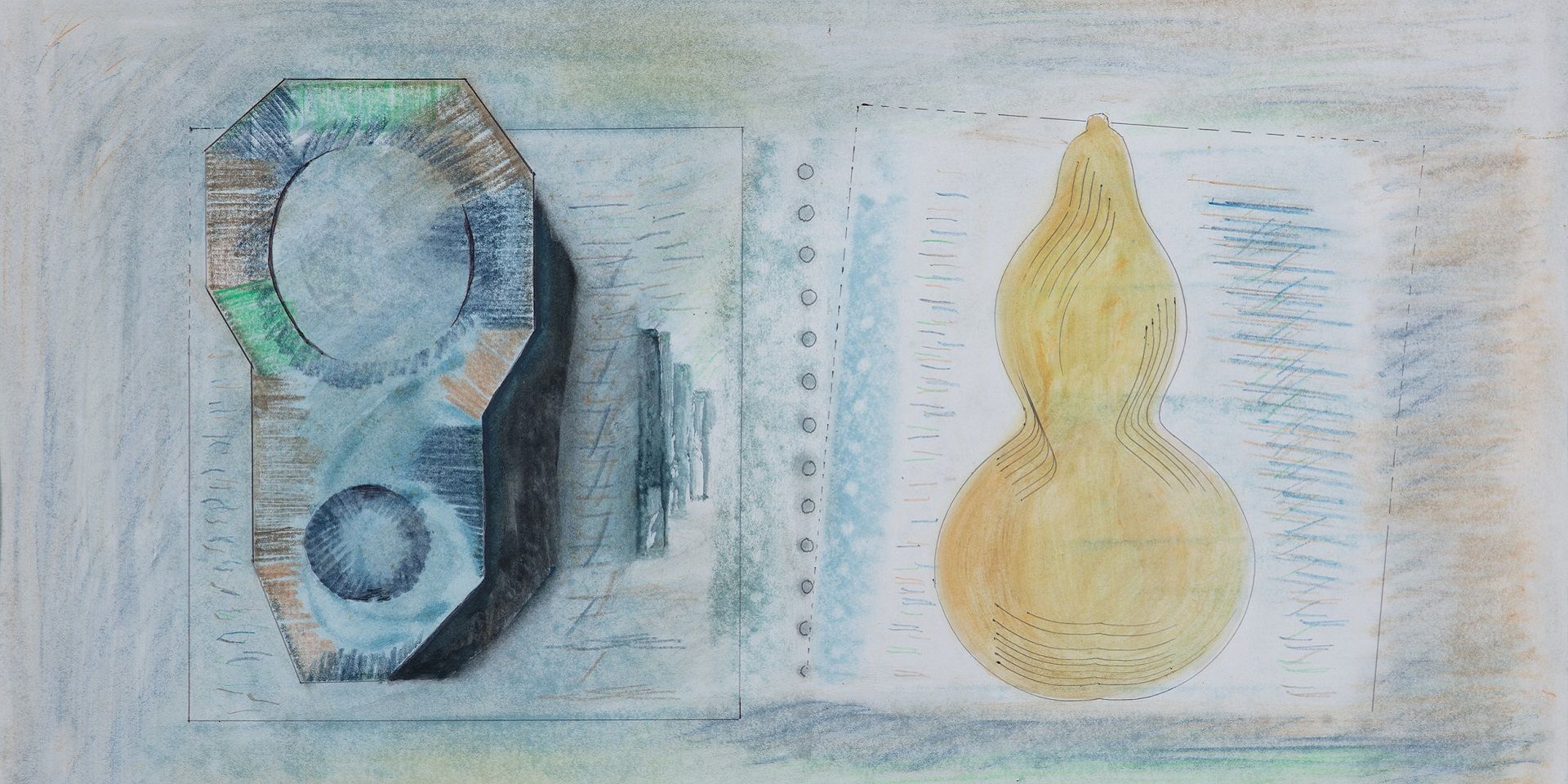

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

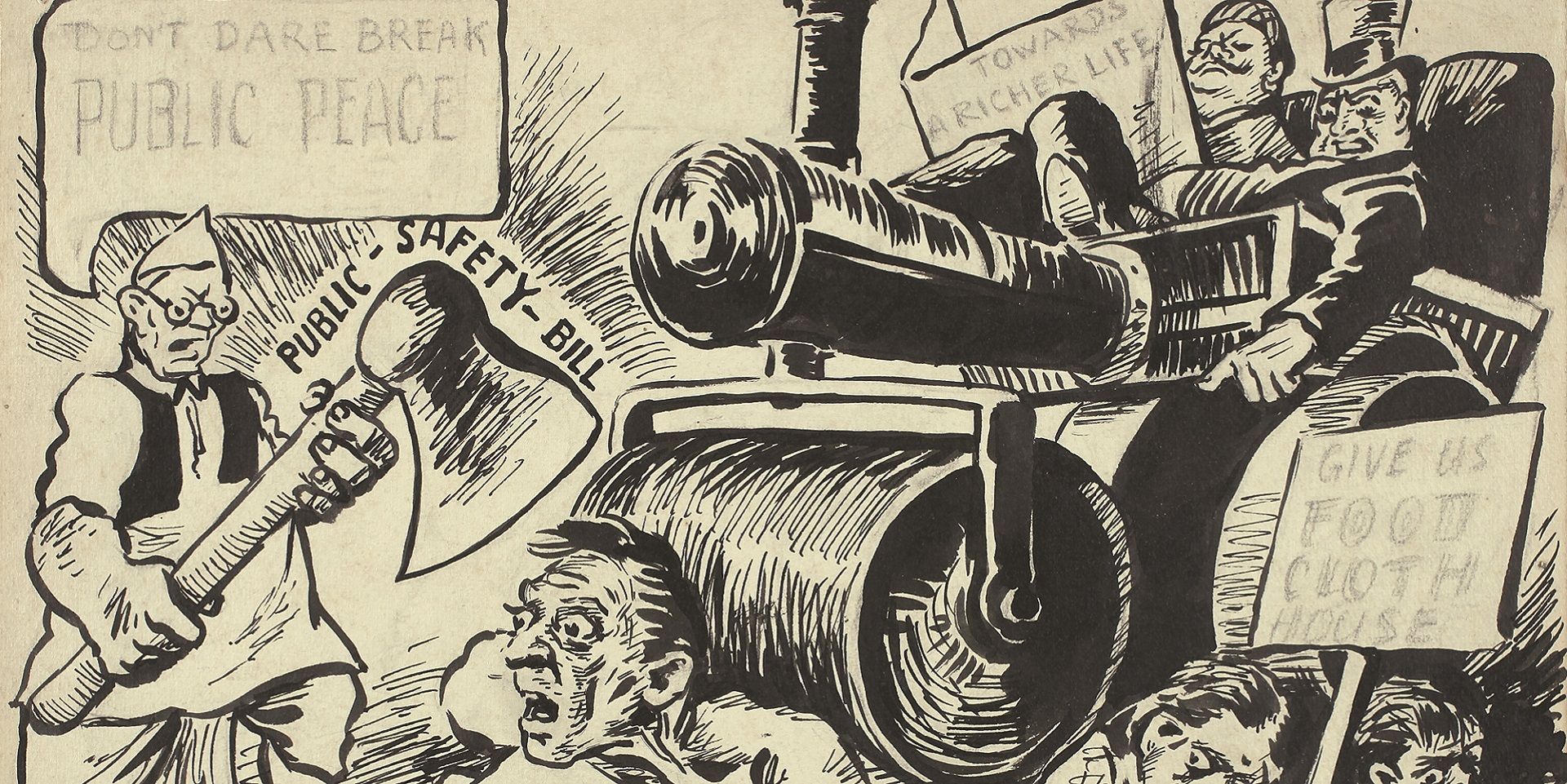

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

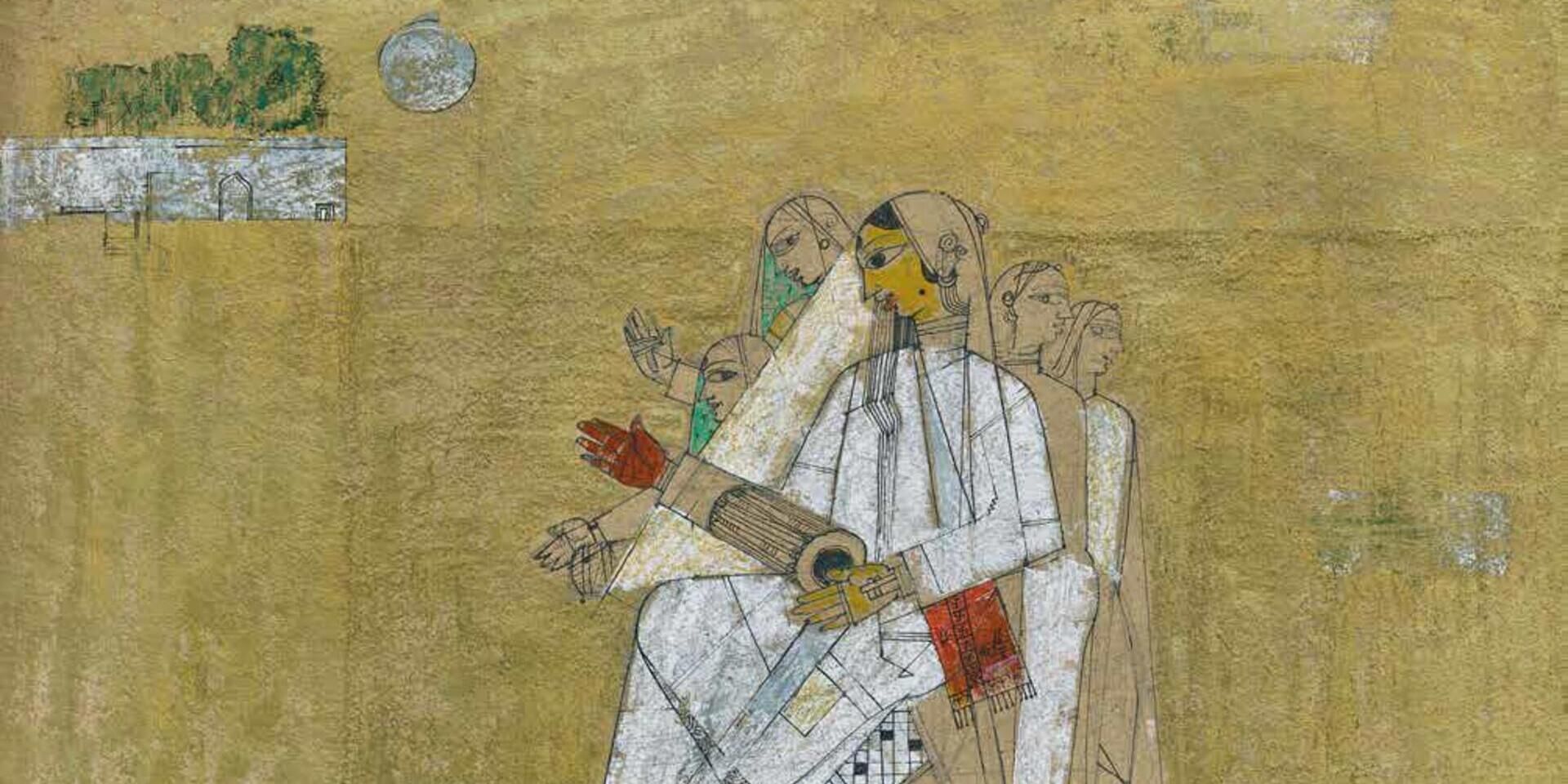

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024