'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

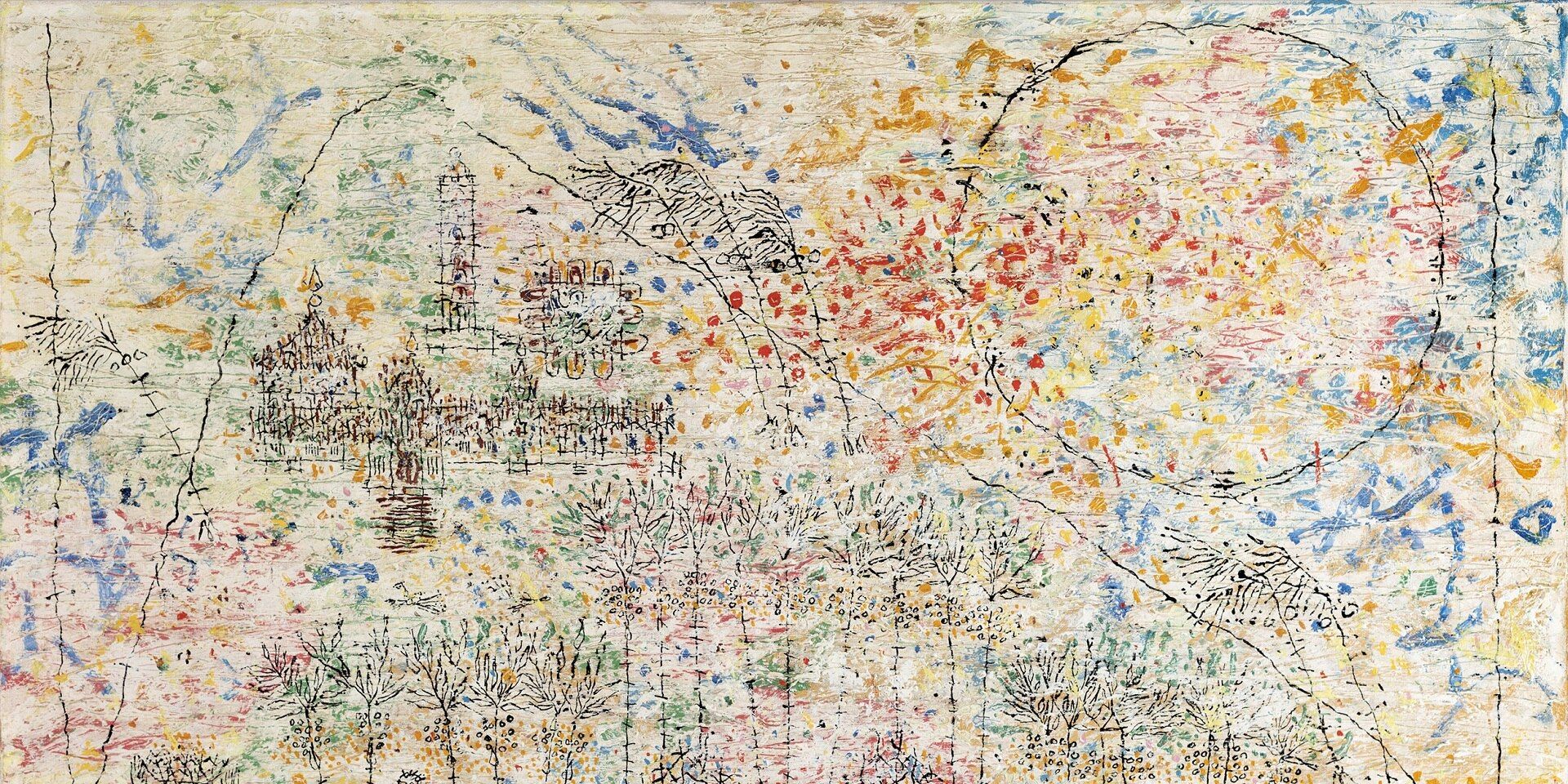

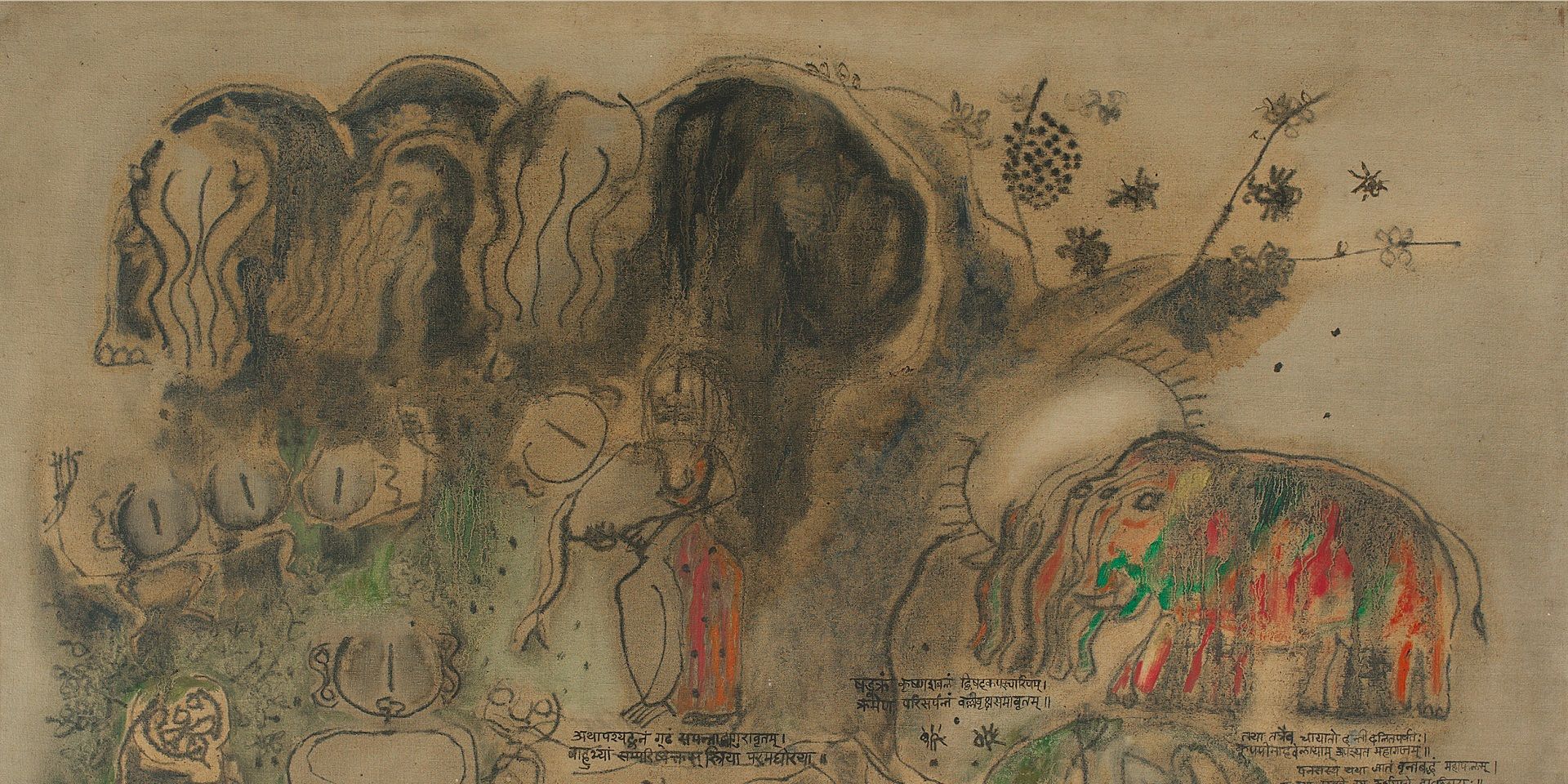

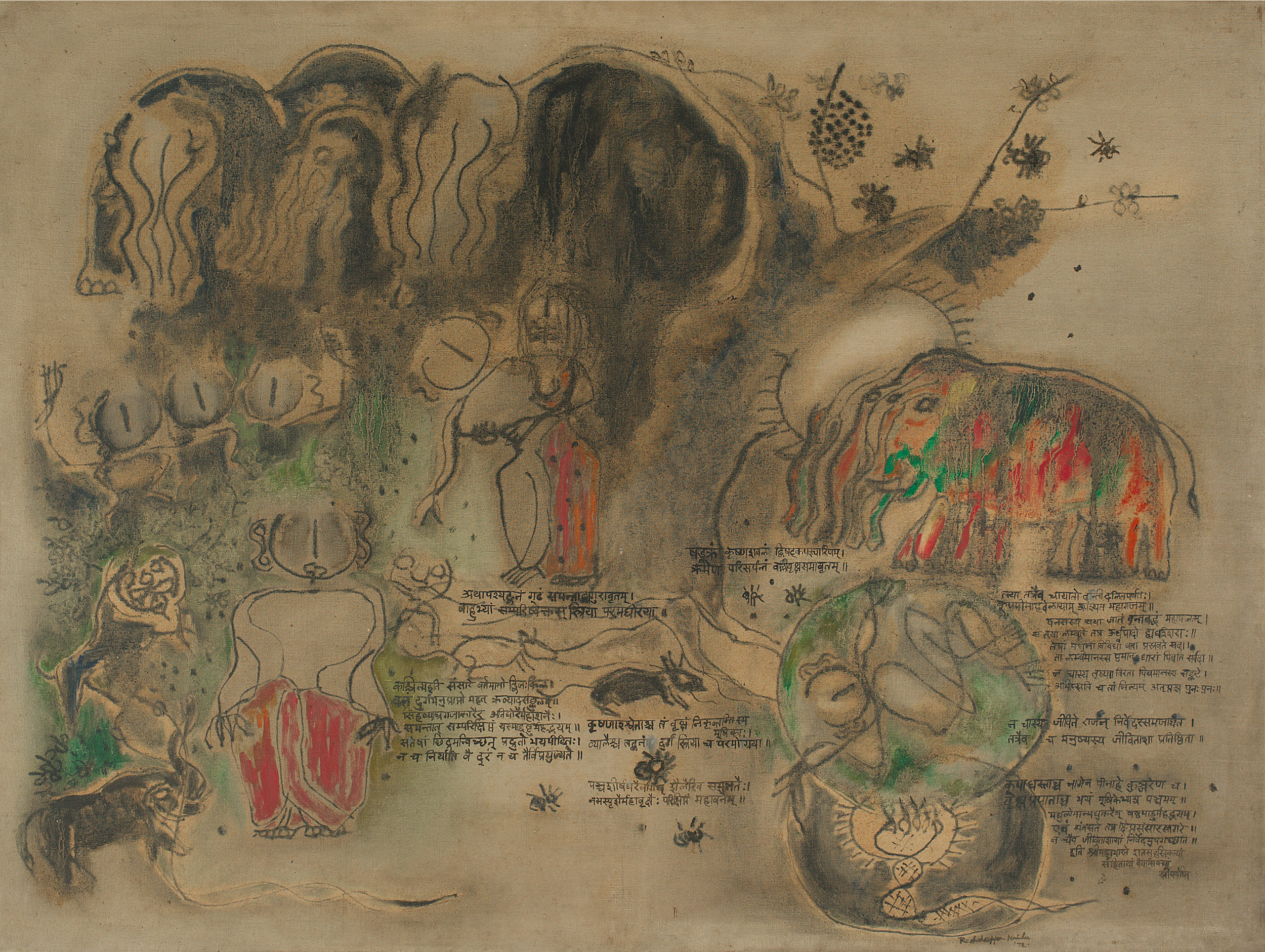

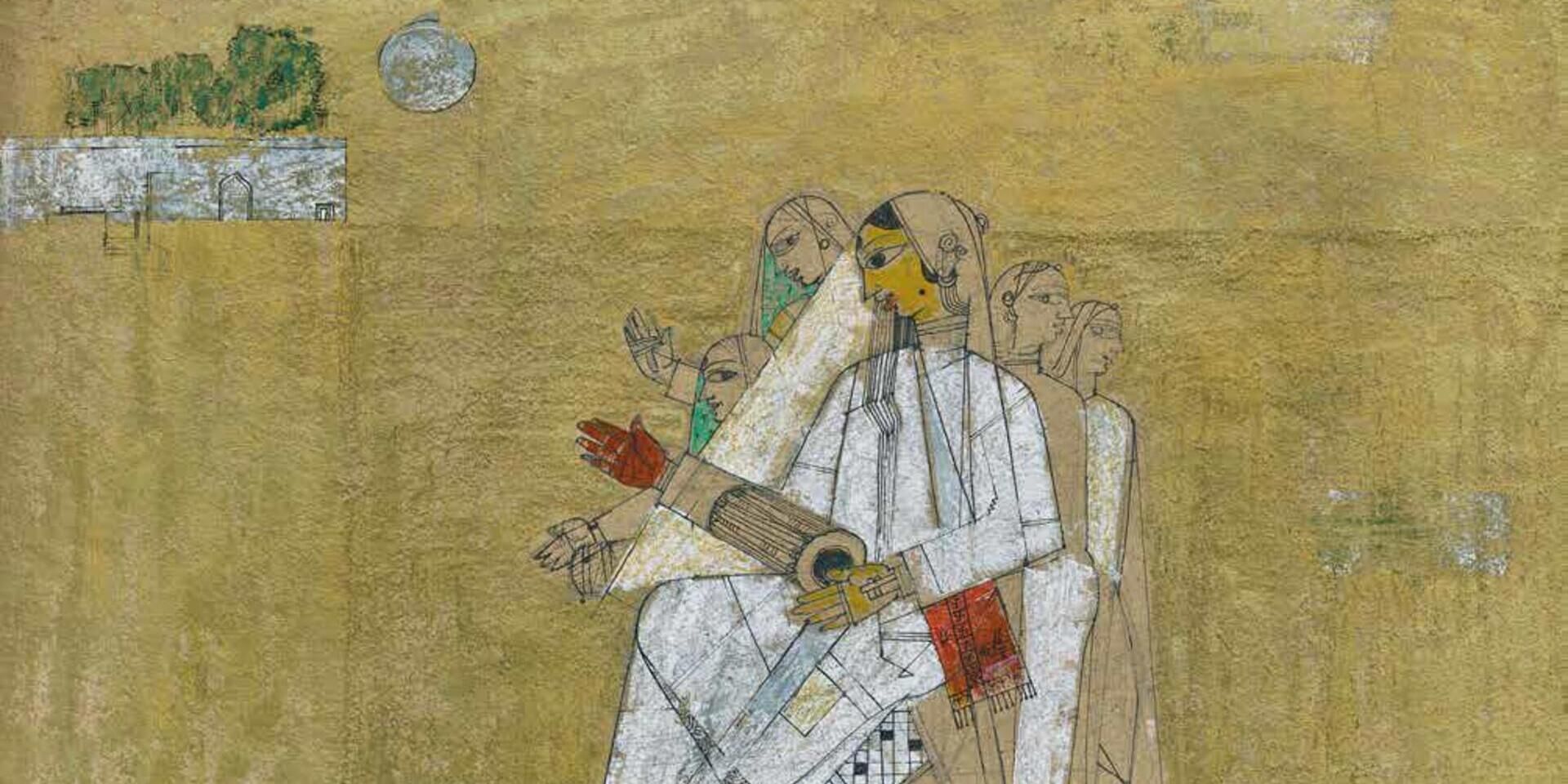

M. Reddeppa Naidu, Stri Parva (Mahabharata Series) (detail), Oil on canvas, 1972, 36.2 x 48.0 in. Collection: DAG

Reddeppa Naidu had a long and illustrious career which intersected with several craft organisations and artists’ collectives, renowned museums and galleries, both in India and across the globe. How did these eventually come to inform his work?

Naidu was the only Madras modernist to simultaneously take part in the activities of ‘Group 1890’, a group consisting of avant garde artists based in Bombay (now Mumbai) and Baroda (now Vadodara) who were hailed for their experiments in material, form and style. On the other hand, Naidu’s long stint at the legendary Weavers’ Service Center in Madras (now Chennai), where he retired as deputy director after twenty-seven years of service, made him a stalwart of the craft revival movement in postcolonial India. Naidu was also closely associated with the Cholamandal artists' village, and spearheaded one of its popular organs, the artists’ handicraft association. He also served as the president of Progressive Artists’ Association formed by the artists from Cholamandal.

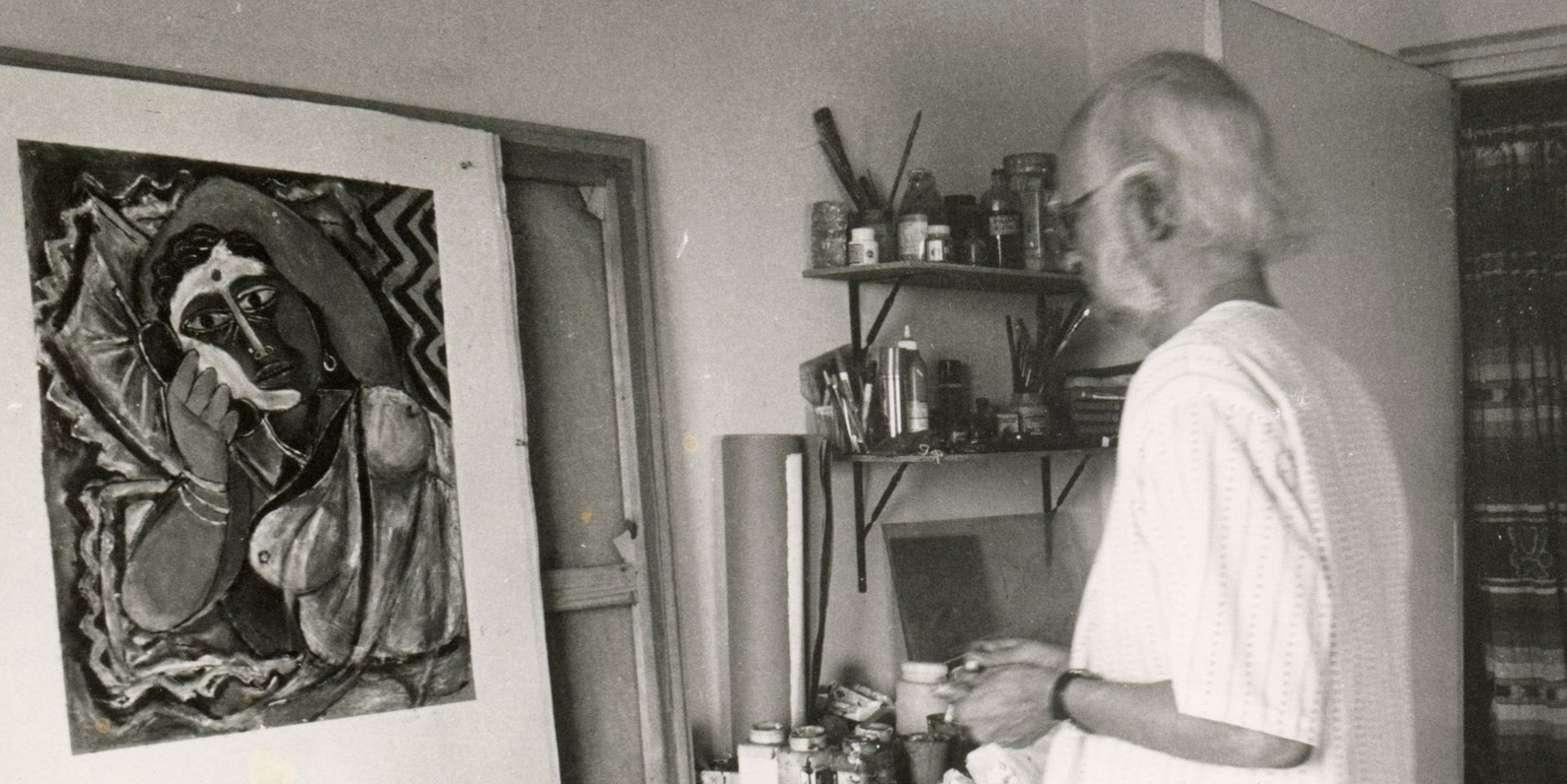

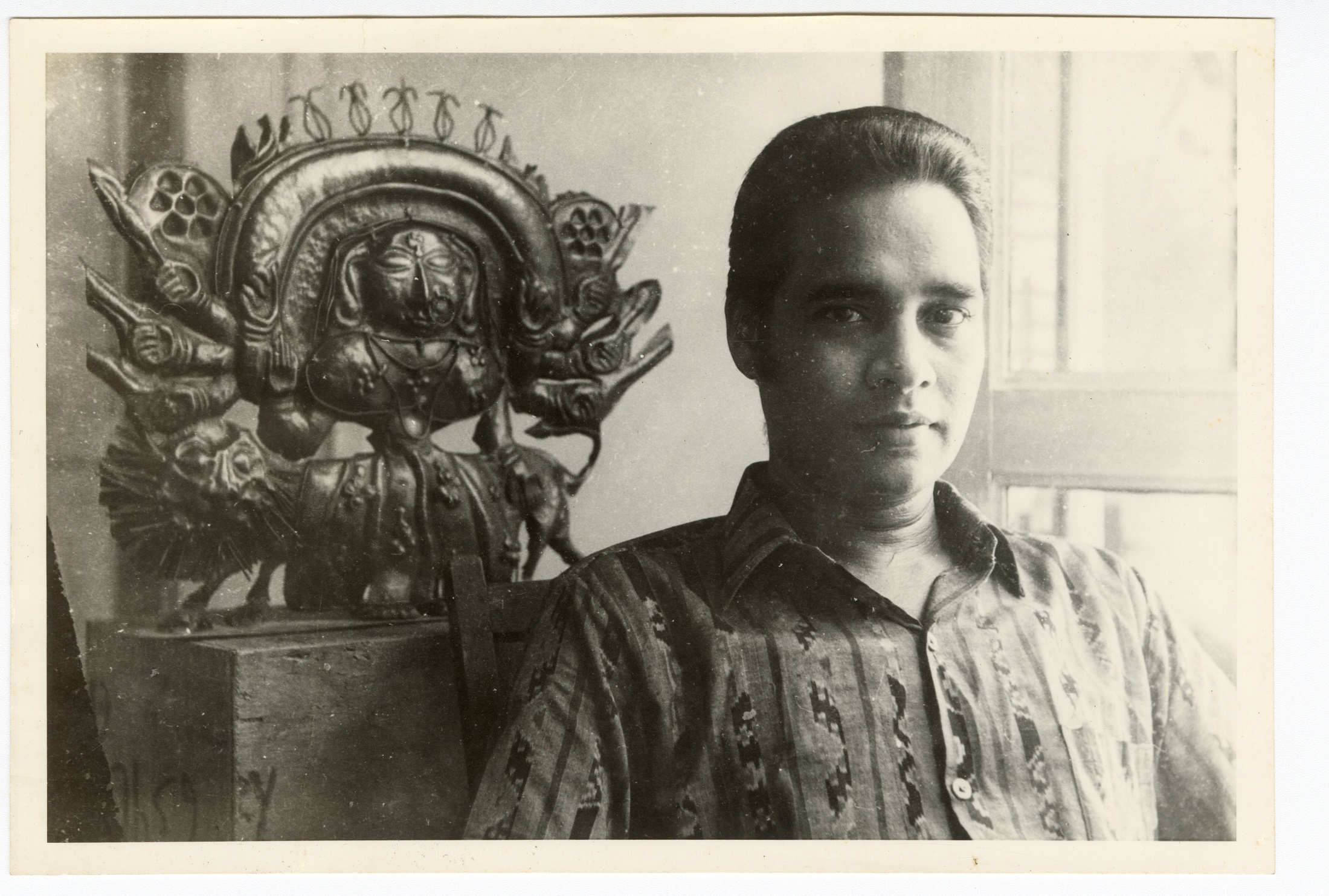

Portrait of the artist, Digital print, 4.5 x 6.7 in. Collection: DAG Archives

Naidu’s unique way of blending the ancient mythologies and modern idioms of painting made him one of the most sought-after painters of his time—the paintings having been exhibited and collected by prestigious institutions globally and nationally.

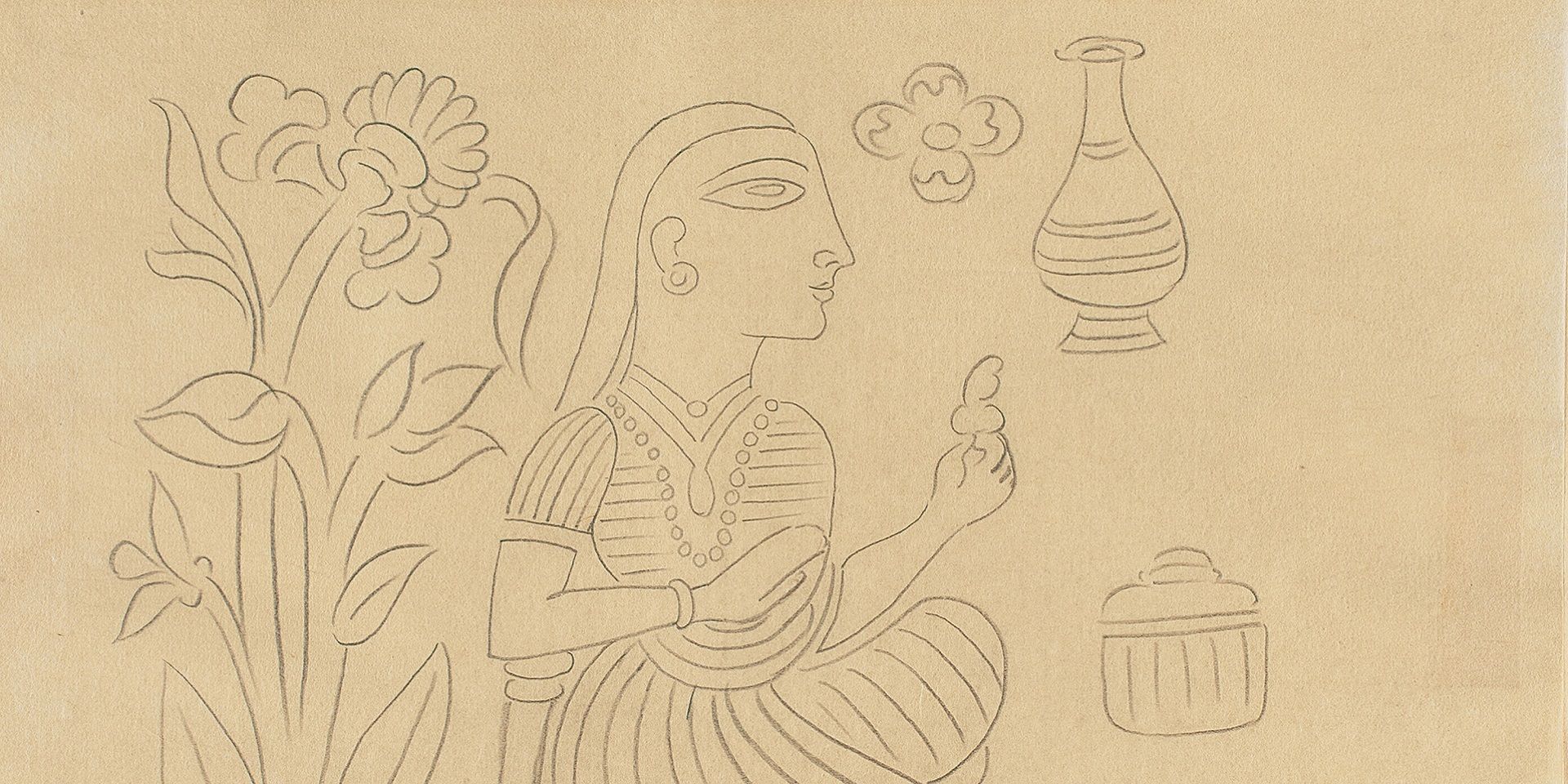

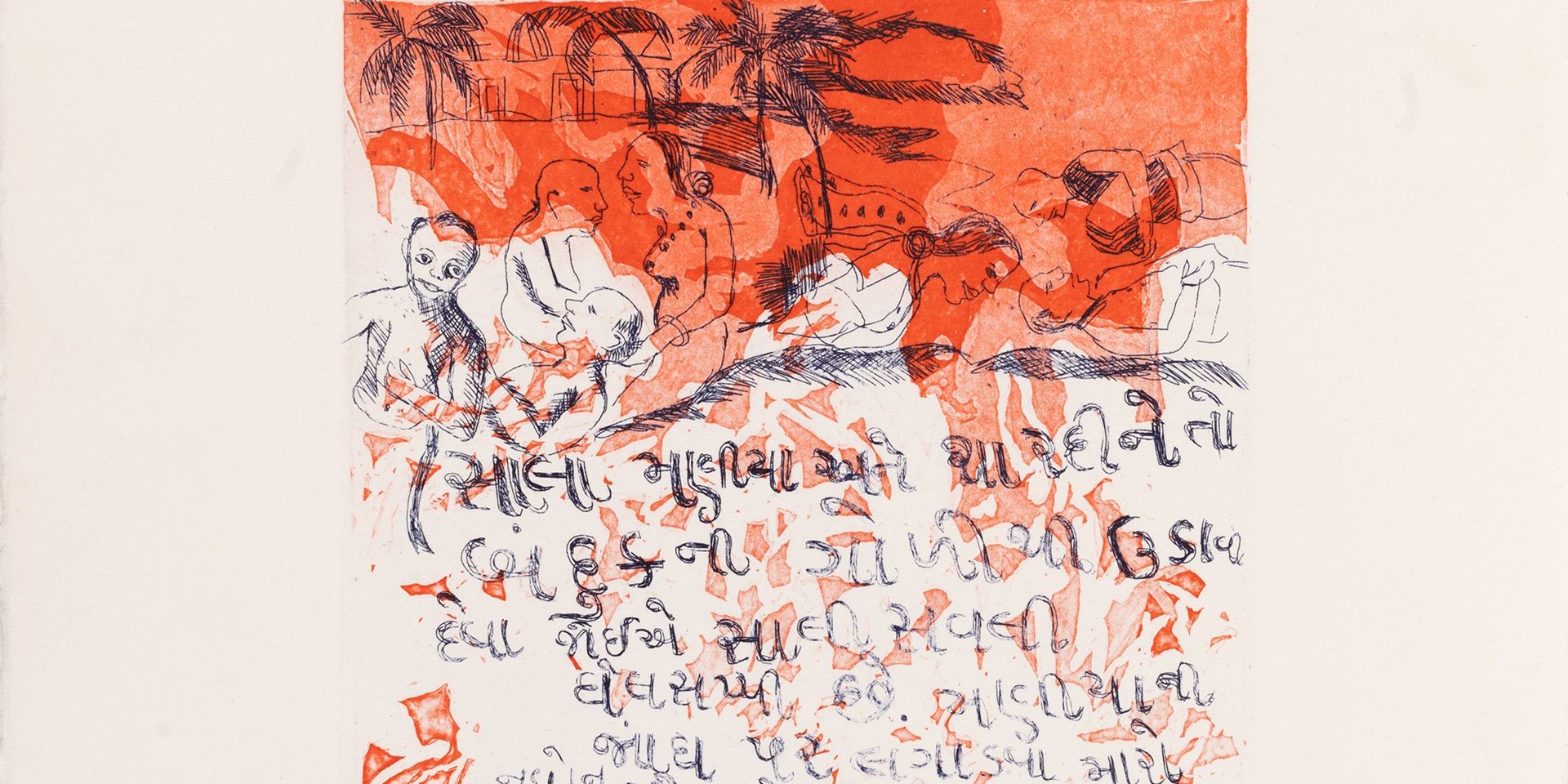

Textile and other regional craft forms deeply enchanted Naidu throughout his career. The artist himself likened the use of scripts within the body of his paintings as a kind of ‘weft work’ which reminds us of the proximity between the two words, ‘text’ and ‘textile’—both coming to us from the same Latin root ‘texere’, meaning woven.

|

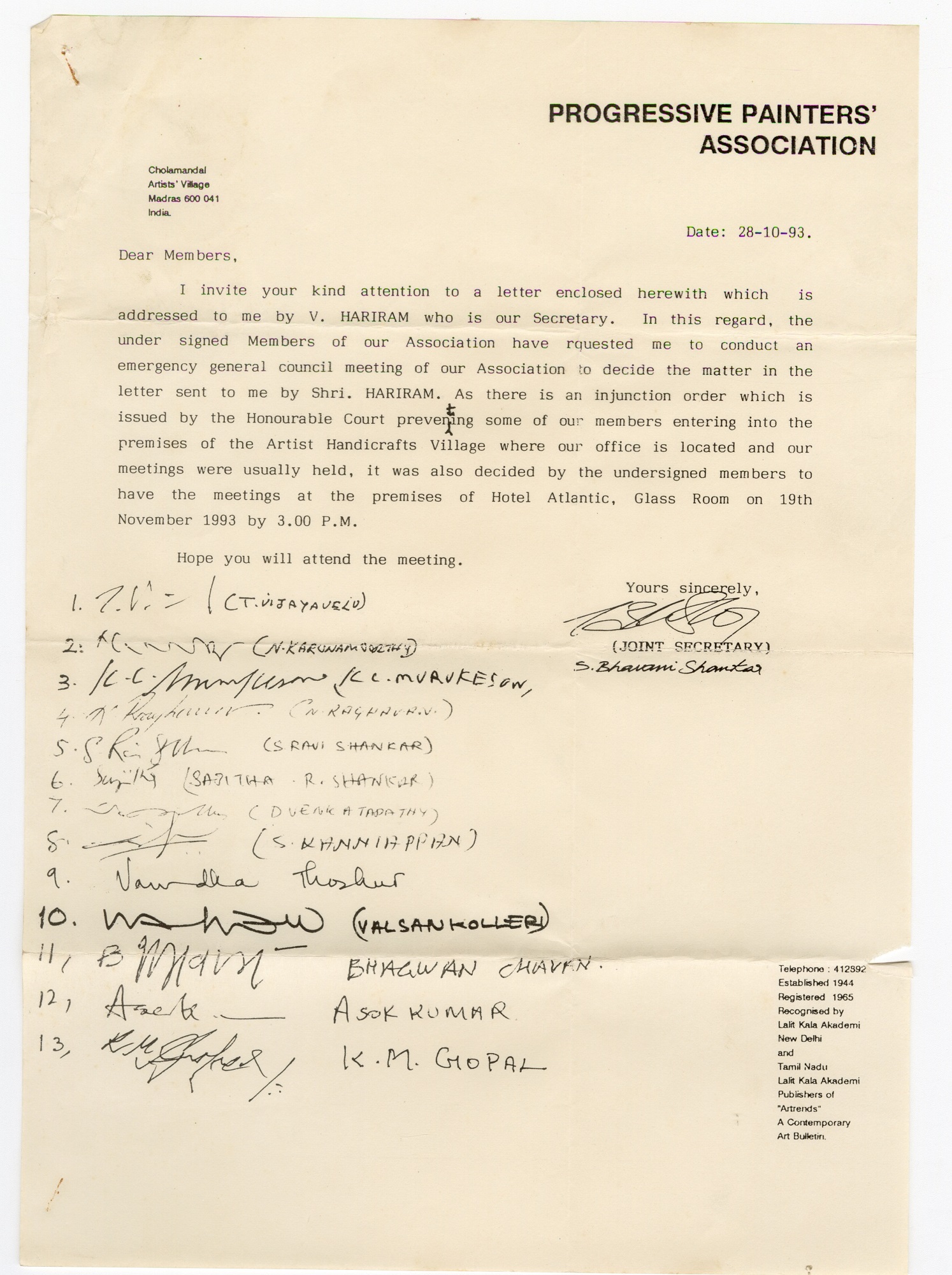

Progressive Artists’ Association, formed by the artists in Cholamandal artists’ village, who were signing a petition against the court’s order preventing the artists to enter the premises of Artists’ Handicrafts Village, which is where the office for Cholamandal was located. Dated 28th October, 1993. Ink on paper, 11.5 x 8.3 in. Collection: DAG Archives |

But why did Naidu, despite having close ties with progressive critics of modernism(s) in India, choose to express himself through mythological themes? We see that the artist’s choice behind retelling the stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata and iconic themes from Christianity is a conscious one, which sates the artist’s inner spiritual quest, but never in a narrow ‘religious’ sense.

|

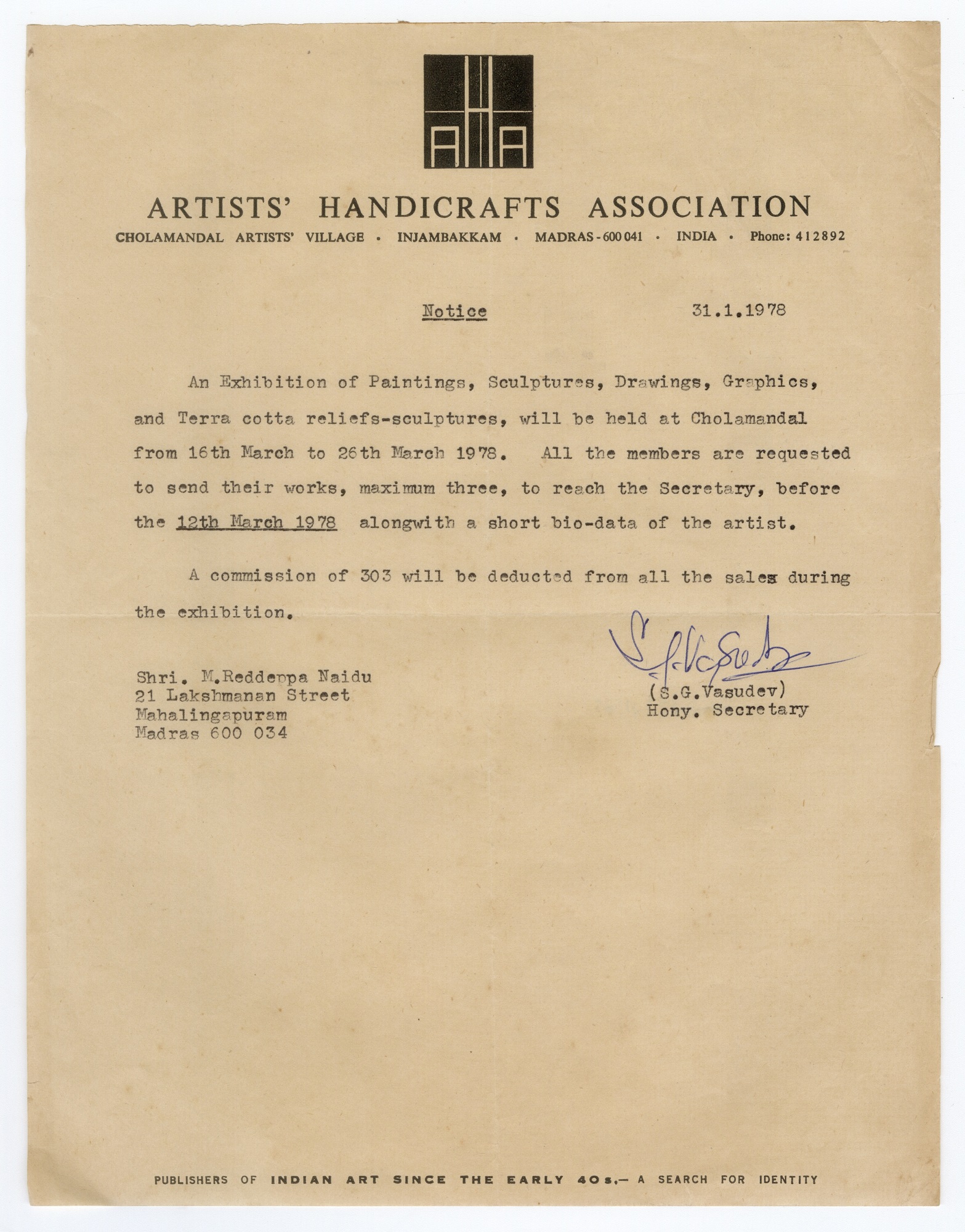

Letter from ‘Artists’ Handicrafts Association, a craft workshop situated in and run by the artists in Cholamandal artists’ village. Dated 31st January, 1978, Ink on paper, 11.0 x 8.5 in. Collection: DAG Archives |

For Naidu, the clairvoyance of the modern artist did not owe anything to the ‘mumbo jumbo of modern aesthetics’. He dispelled the airs of novelty and originality around modern art and claimed that it was merely an ‘updated tradition’. What mattered most for Naidu was the conscious acquisition of the knowledge of living minds from the past that allows an artist today to trace one’s origins in a culture, know one’s place within a collective history, and enables one ‘to identify oneself with one’s own secret urges.’ In his words, ‘the ‘livingness’ of the past is contacted by acquiring the knowledge not by imitating them. It is challenge (sic) to live in my time with myself and that knowledge … [which] enriches one’s own inner self tremendously.’

Poster for ‘Art Exhibition 1992’ in Government College of Arts and Crafts Alumni Association, Madras. Print on paper, 3.0 x 8.5 in. Collection: DAG Archives

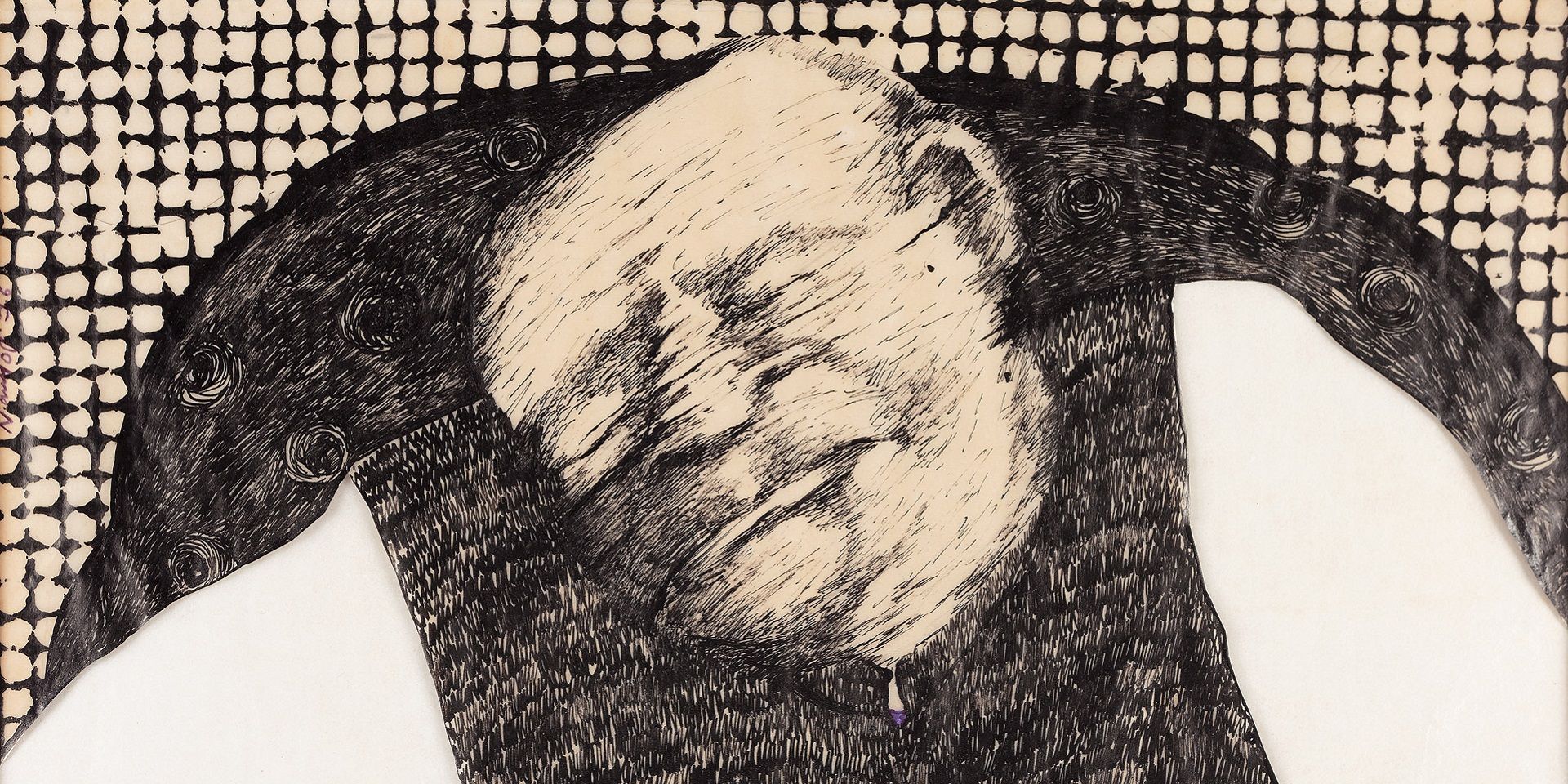

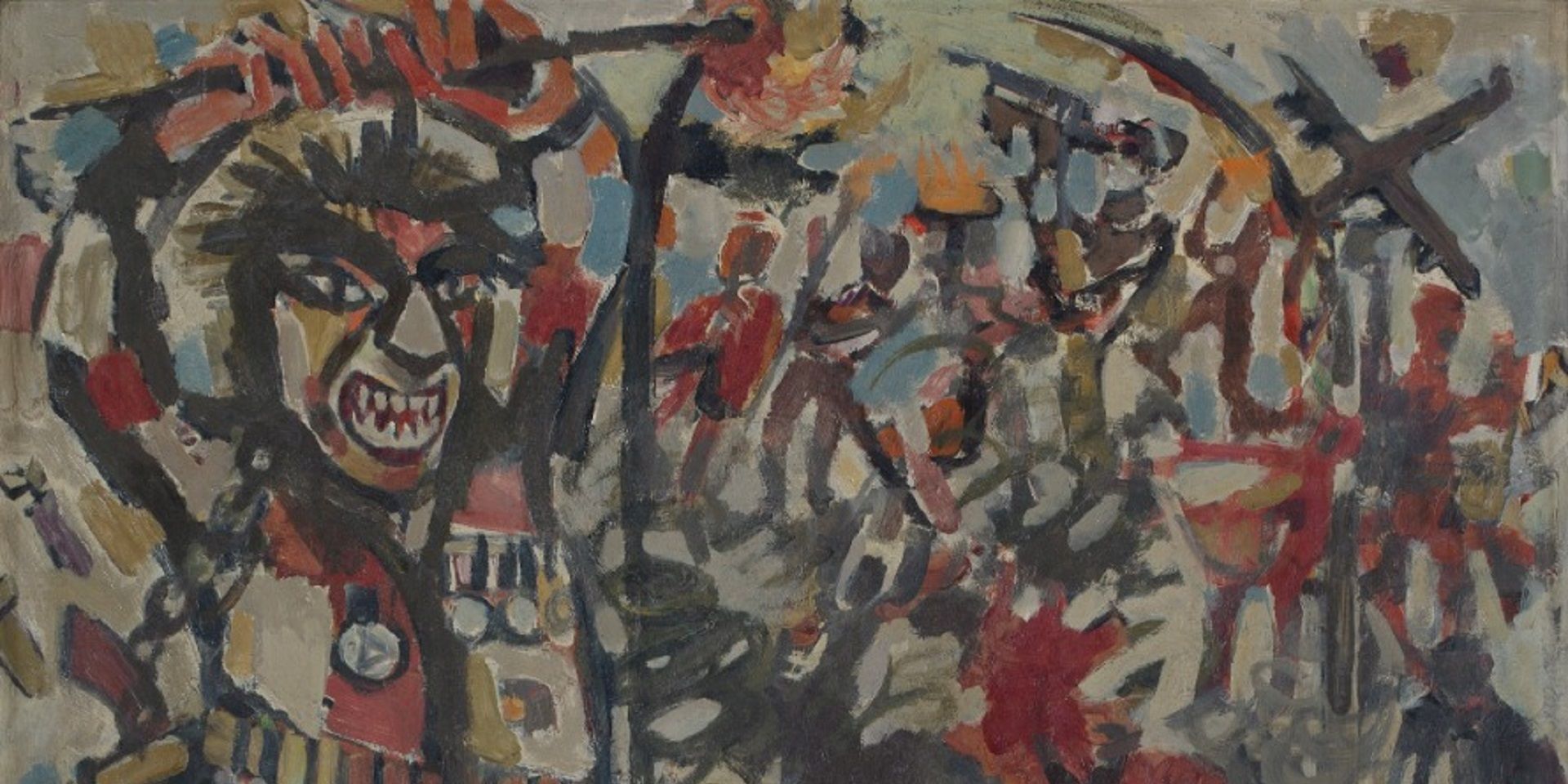

Perhaps the most iconic of Naidu’s works are the eighteen paintings in his Mahabharata series , depicting each episode of the epic like ‘cantos’, painted between 1972 and ’74, mixing the original Sanskrit stanzas with his idiosyncratic style of painting where ‘his colour, caught in the sieve of lines, gleam and sparkle with dignity of possible stained glass’, as Paniker once remarked. The series was born from a fortuitous encounter between the painter and his Telugu poet friend M. Deendayal. The poem that his friend read to him talks about a remarkable fable metaphorising the circle of life of man on earth from Stri parva, an uneventful episode following the epic saga of the Kurukshetra battle, and deals with the women mourning their losses in the aftermath of the event.

M. Reddeppa Naidu , Stri Parva (Mahabharata Series), Oil on canvas, 1972, 36.2 x 48.0 in. Collection: DAG

This is how the story narrated by a Rishi to console a bereaved Dhritarashtra goes−a man finds himself surrounded by wild and cruel creatures in a jungle. Attacked by robbers, ambushed by a six-trunked elephant, this man fell into a well and somehow saved himself by clutching to the trunk of a banyan tree. However, he soon found beneath him a five-hooded serpent and realised that the life-saving trunk had been gnawed at by two rodents; one black and the other white. As this man grappled with the whole debacle, he saw honey dripping from a honeycomb overhead and reached out to catch drops of honey—and this part astonished Naidu—‘with all this, our passion for life is unabated, for even chance drops of pleasure can rivet our attention to their precarious life of perishable joy.’ Ultimately, as the man found a way out of the gaping well, he fell into the inextricable embrace of an unattractive old woman, showing us how the same pleasurable follies of youth turn into bitterness and shrinkage in old age. Naidu recounts, ‘this is the Samsara-grahanam that the Rishi explained to mournful Dhritarashtra at the end of the Kurukshetra battle. It was this parva that Shri Deendayal asked me to paint, some time in June, 1972.’

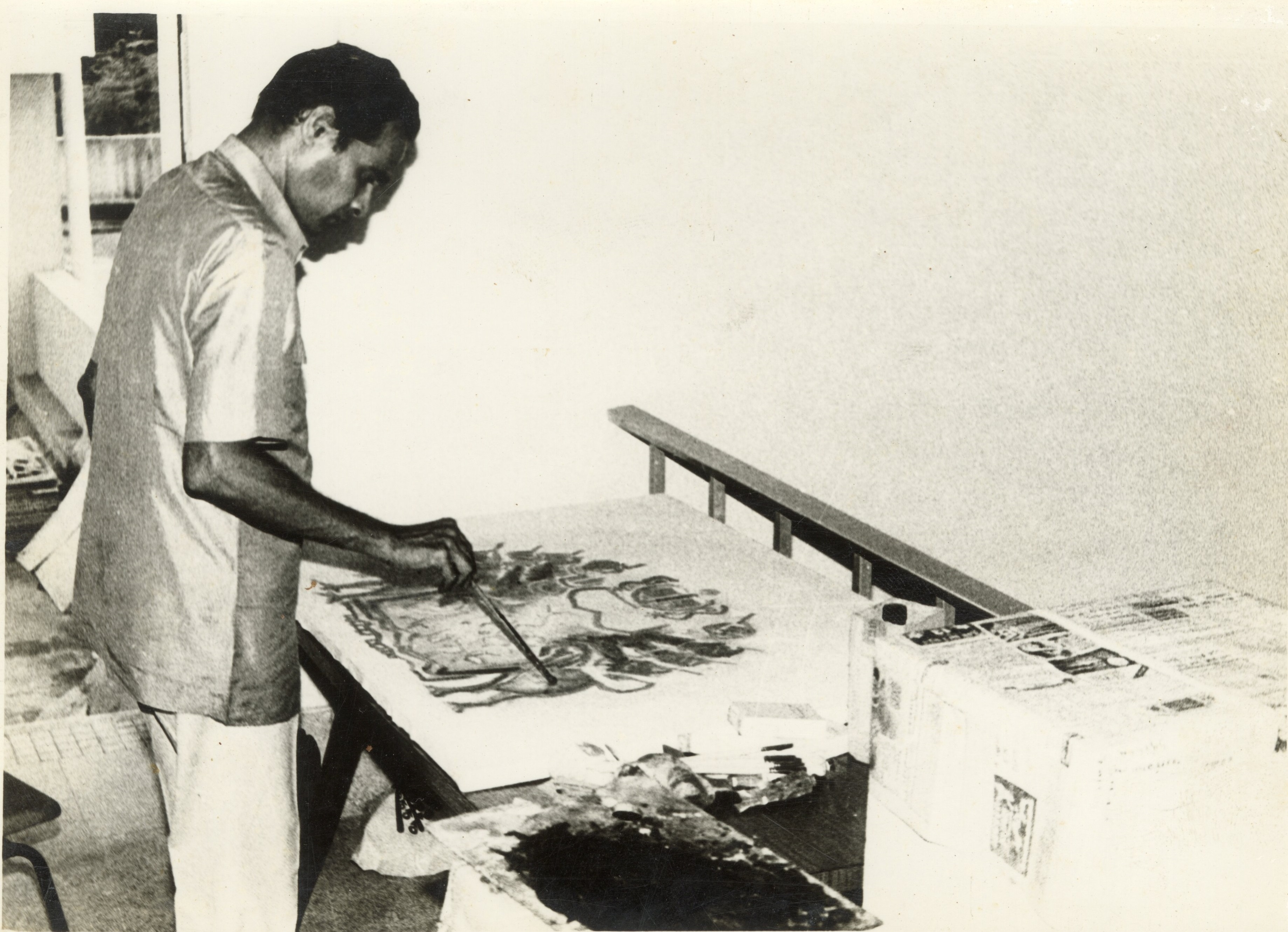

M. Reddeppa Naidu at his studio. Digital print, 4.4 x 6.2 in. Collection: DAG Archives

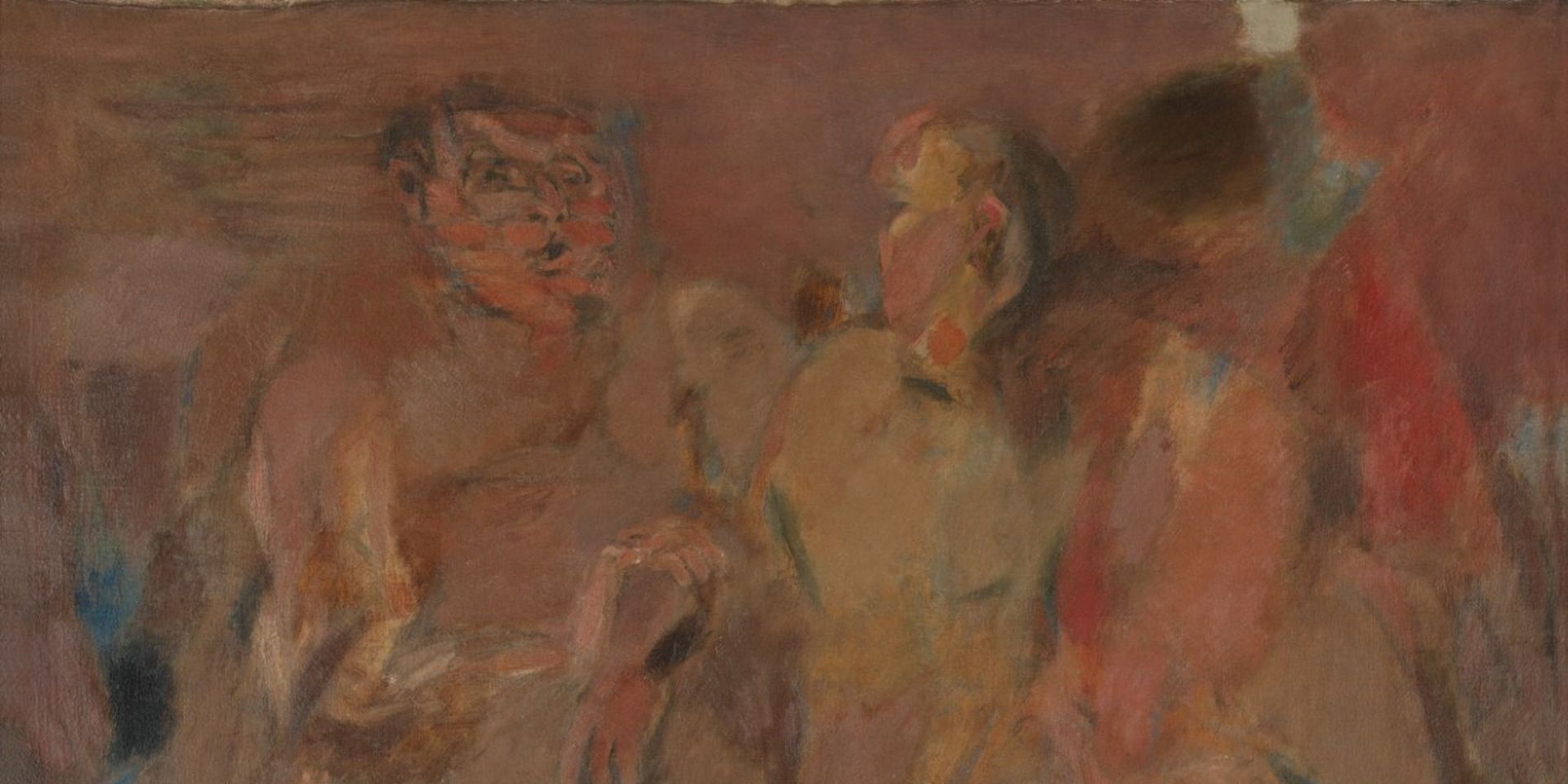

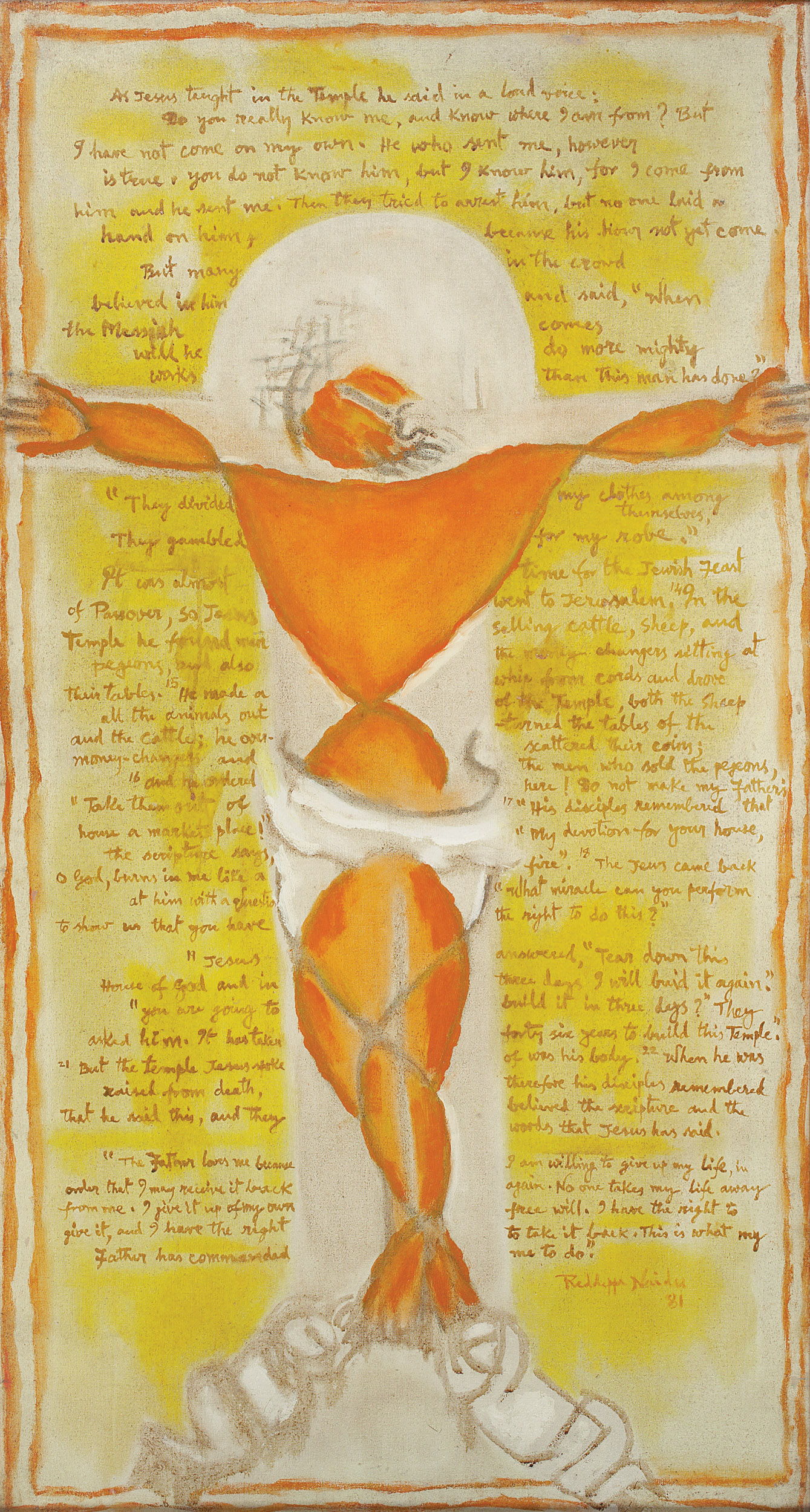

On the other hand, it was the Bishop of Madras, Lesley Newbigin, who commissioned Naidu to paint the Church Hall, thus sparking his interest in the New Testament, the incarnation of Christ, and finding the deeper meaning of Christianity. He noted the true purpose of Christ’s avatar in helping the needy. Naidu stylistically moulded the classic Western subjects like Christ with sinners, Mary Magdalene and the Resurrection.

M. Reddeppa Naidu, Untitled (Crucifixion), Oil on canvas, 1981, 45.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

’He has the makings of a superb and free painter from whom one may expect a great painting some day’, K. C. S. Paniker had once remarked. Indeed, Naidu’s eclectic and deeply personal interpretation of modernism—not only as the impetus for some figural abstraction or formal experiment, but one steeped in tradition and collective systems of knowledge such as mythology—made him an important figure in Indian modern art, alongside figures like J. Sultan Ali and Paniker himself, who had shown unwavering support and mentorship to young Naidu.

M. Reddeppa Naidu at his studio. Digital print, 4.0 x 5.7 in. Collection: DAG Archives

related articles

Essays on Art

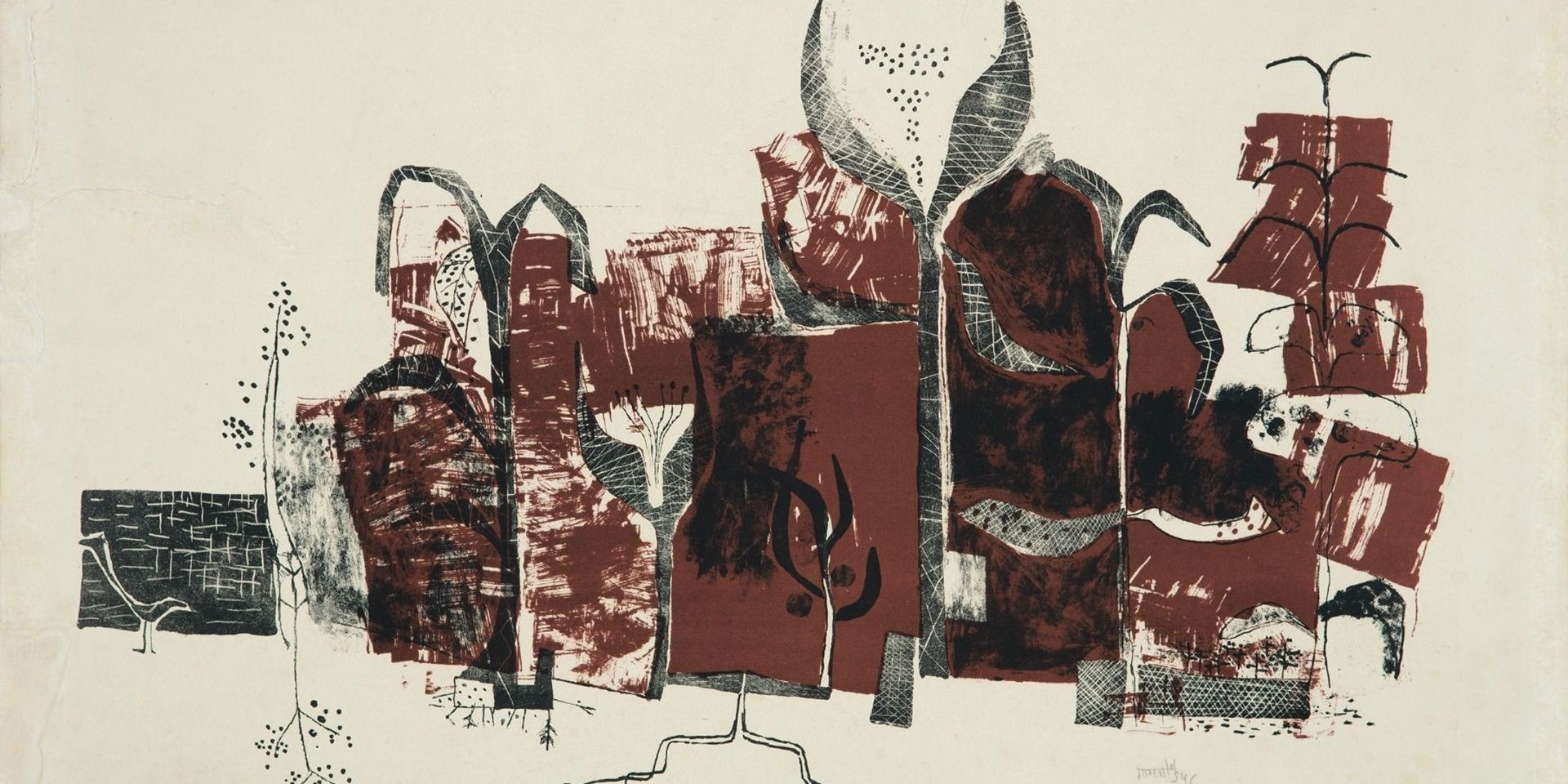

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

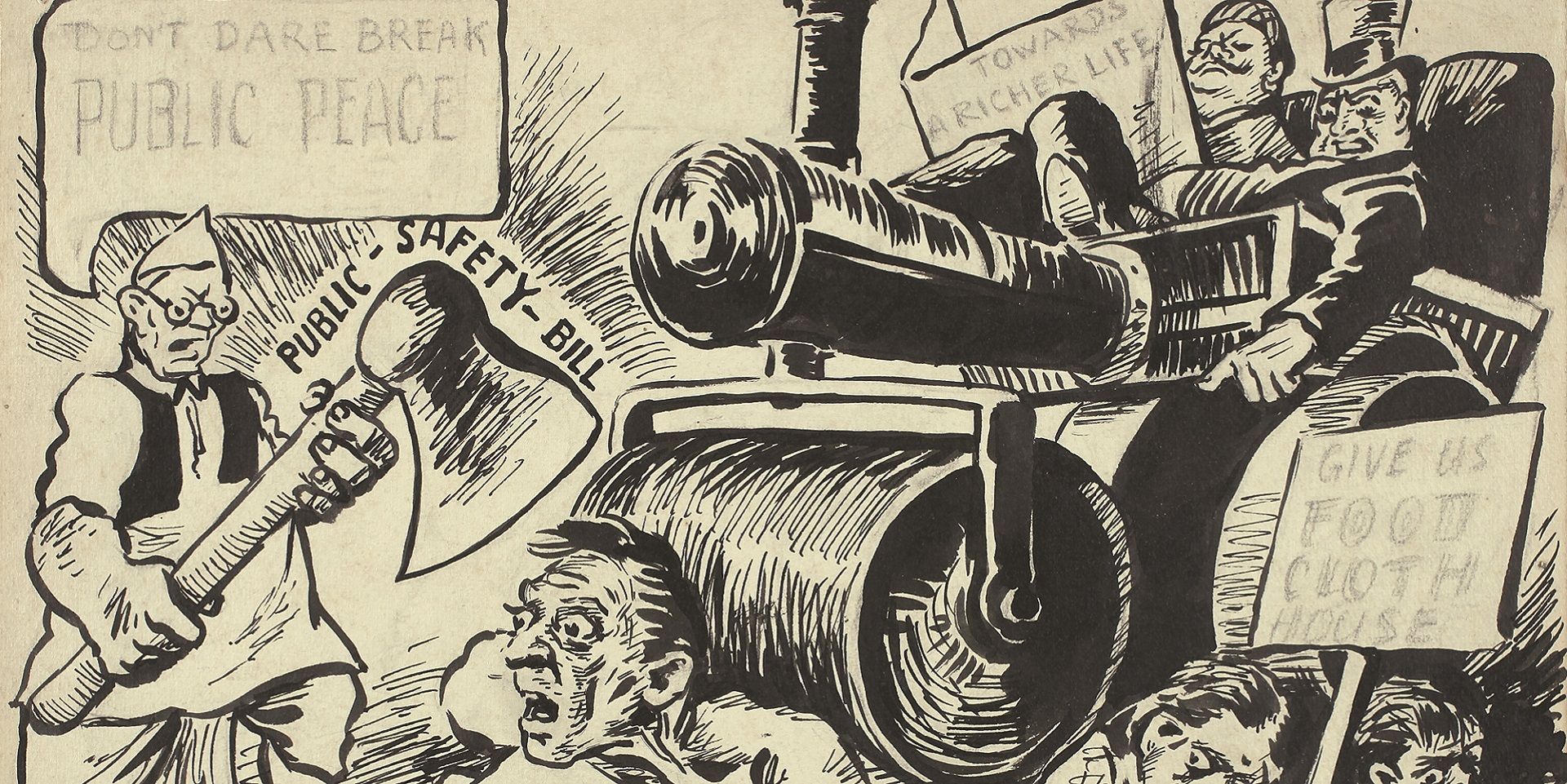

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

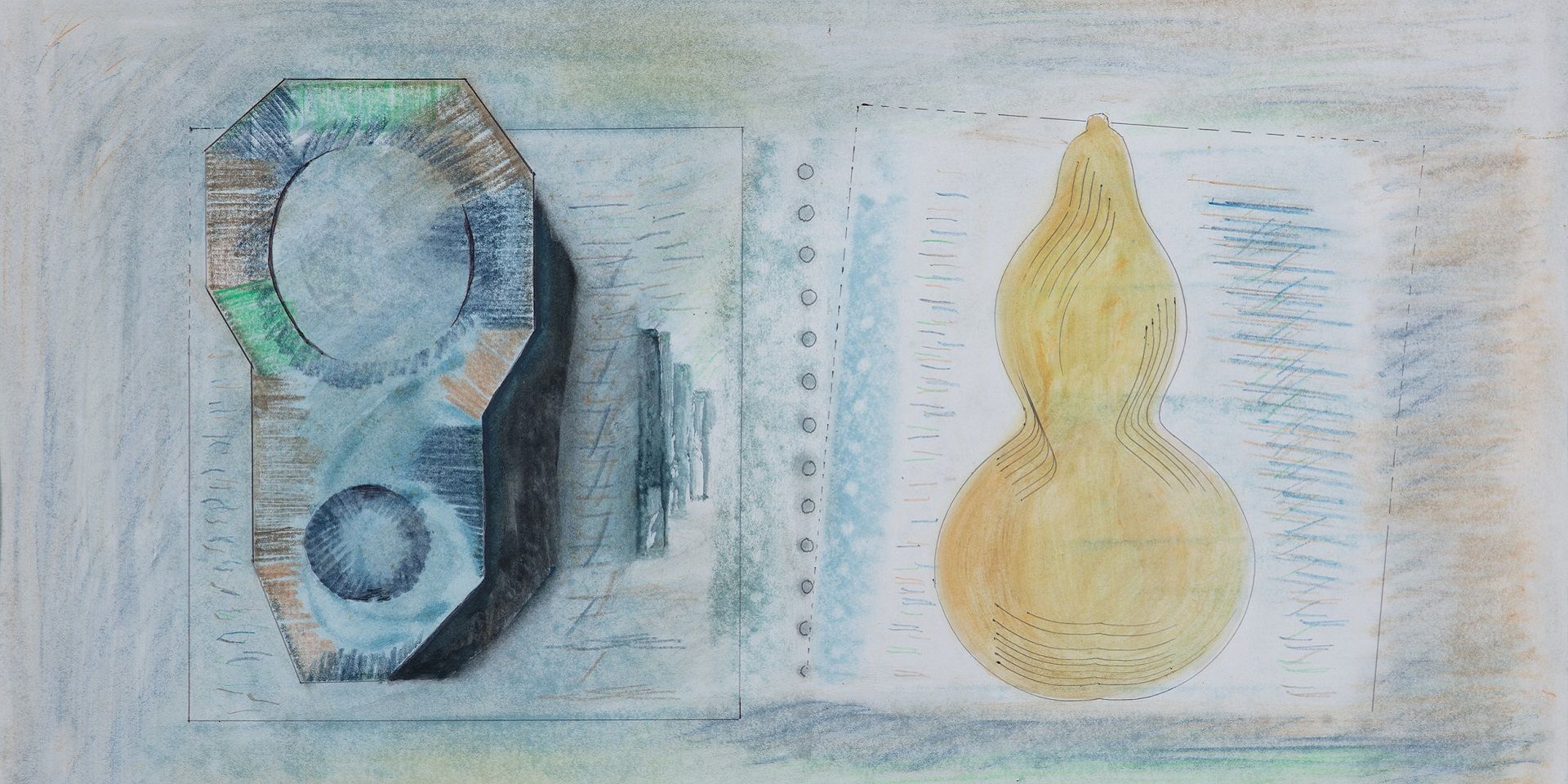

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024