Finding a Refuge: Indian Modern art and Migration

Finding a Refuge: Indian Modern art and Migration

Finding a Refuge: Indian Modern art and Migration

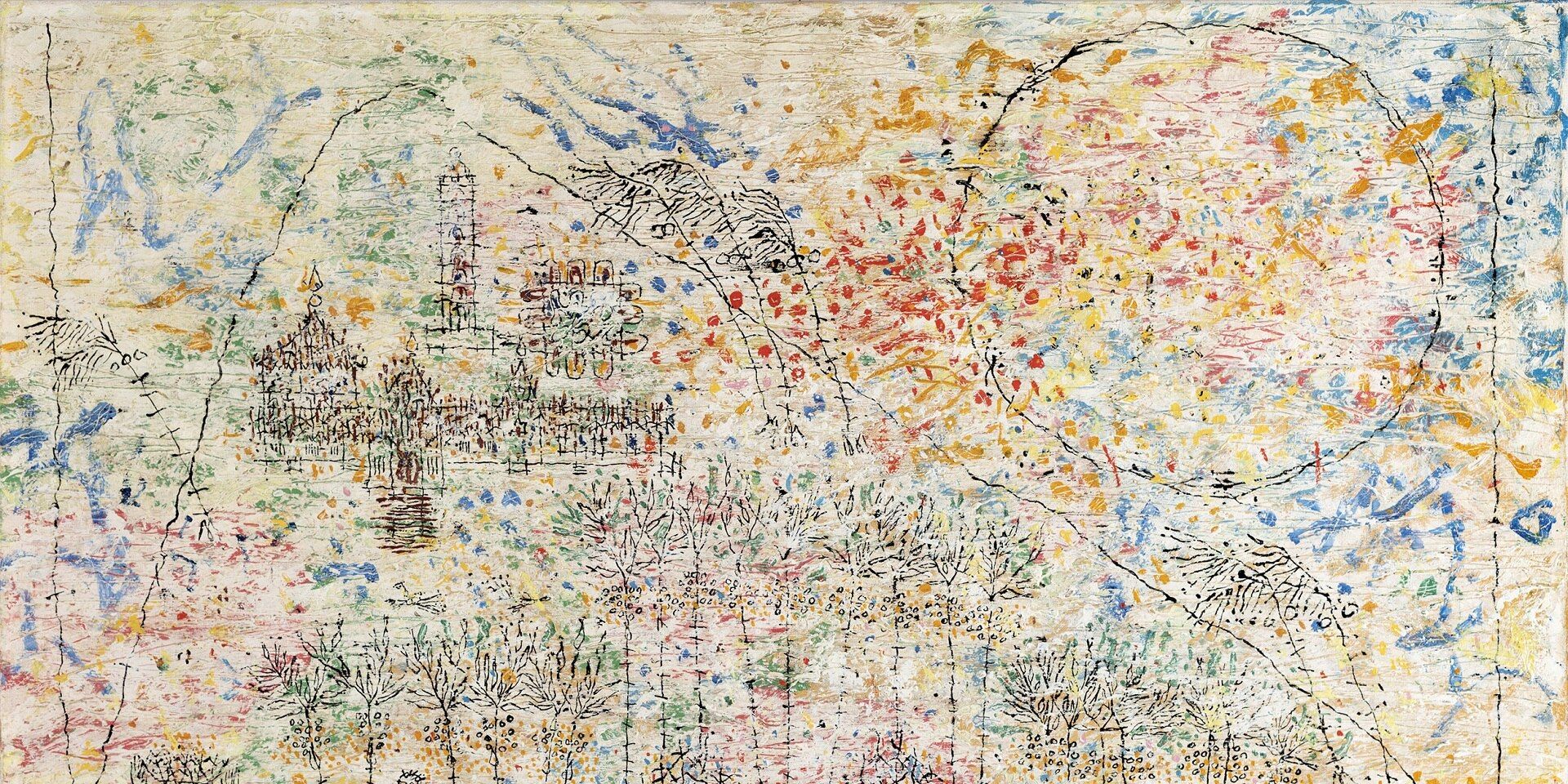

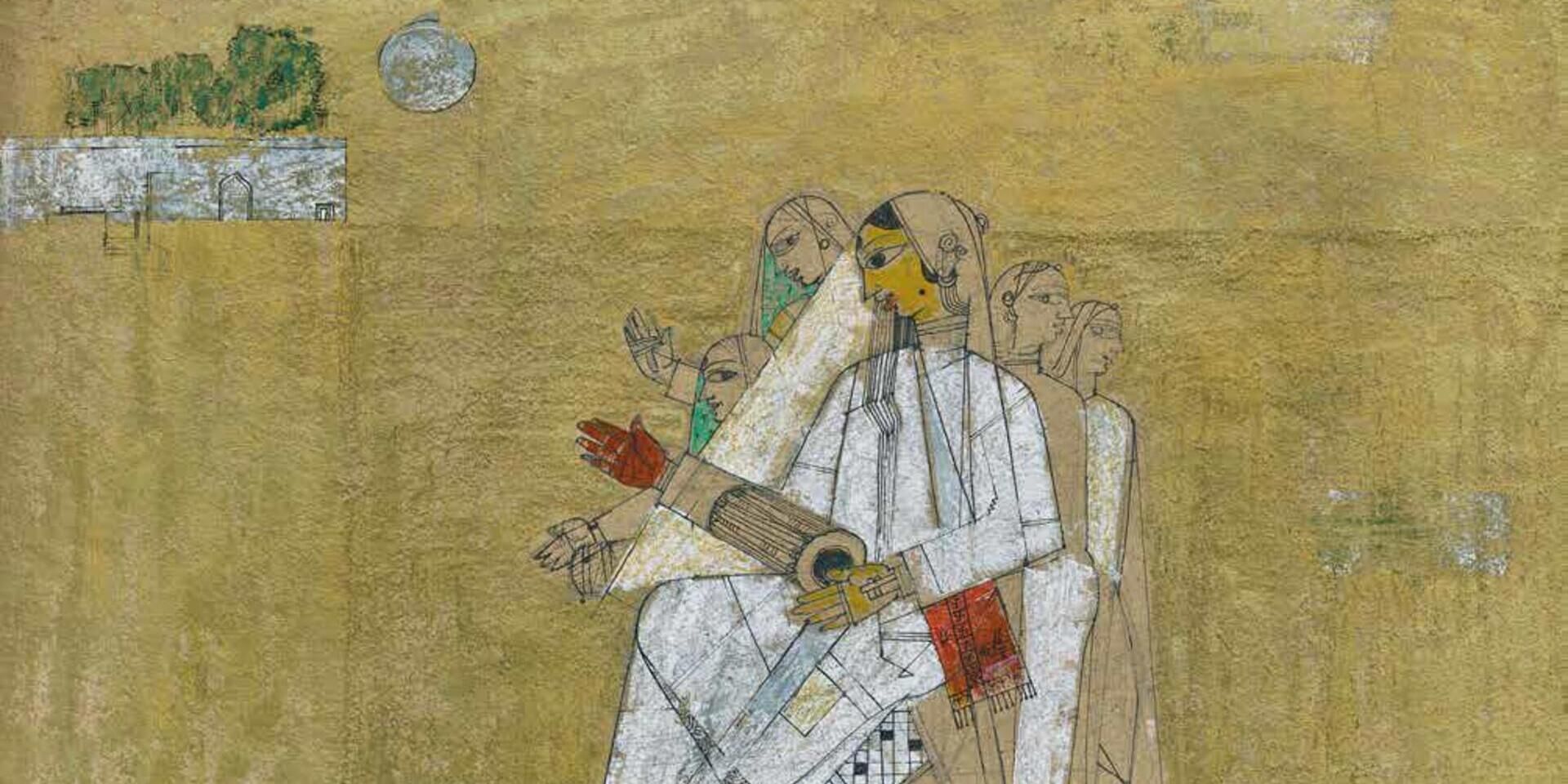

Ganesh Haloi, Untitled (detail), 1992, Gouache, watercolour and acrylic on handmade paper, 16.5 x 19.0 in. Collection: DAG

The connection between migration, refugeehood, and the development of modern art is profound, reflecting both personal and political aspects of displacement. Modern art emerged amidst global turmoil, including wars, political revolutions, and the rise of nationalism, all of which had a direct impact on artists, many of whom were refugees or migrants themselves.

A key element of this connection is how modern artists responded to the trauma of displacement. Scholars have noted that modernist art was, in part, shaped by the experiences of migration and exile, which offered fresh perspectives on the world. The upheaval of displacement often compelled artists to re-evaluate their identities, respond constructively to the material world around them, and reflect on their emotional ties to their homelands, all while contemplating art’s role during times of crisis.

|

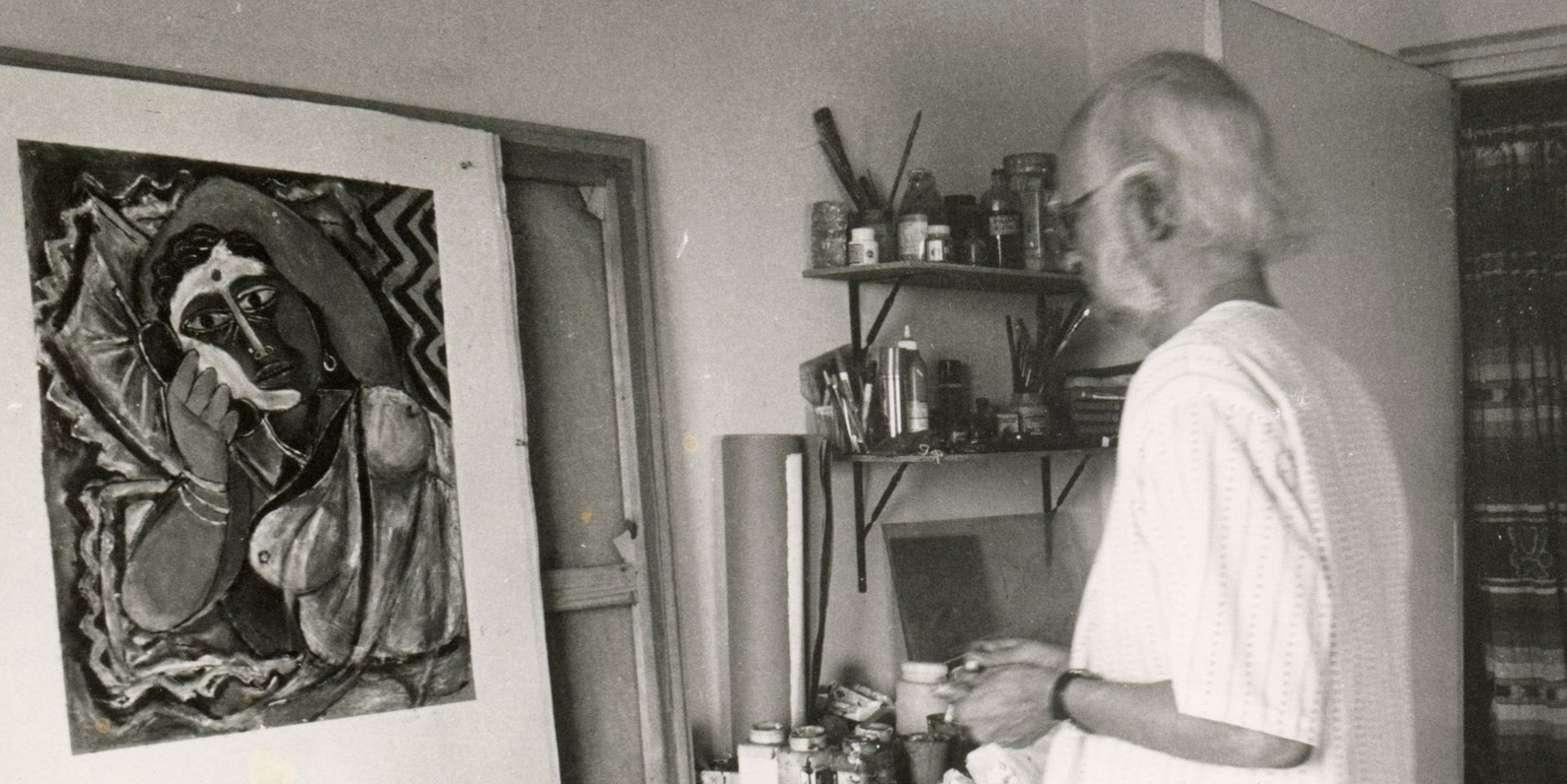

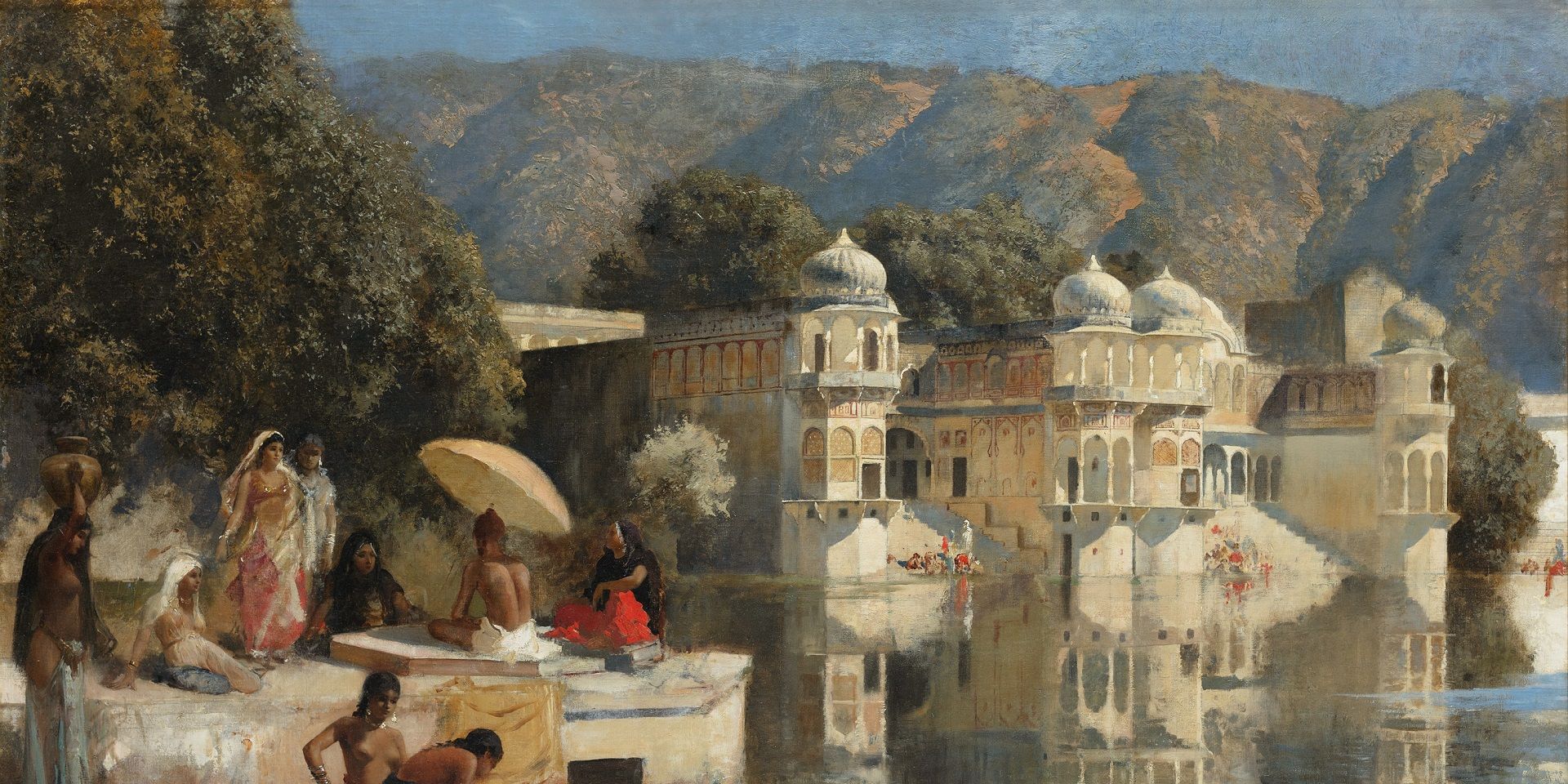

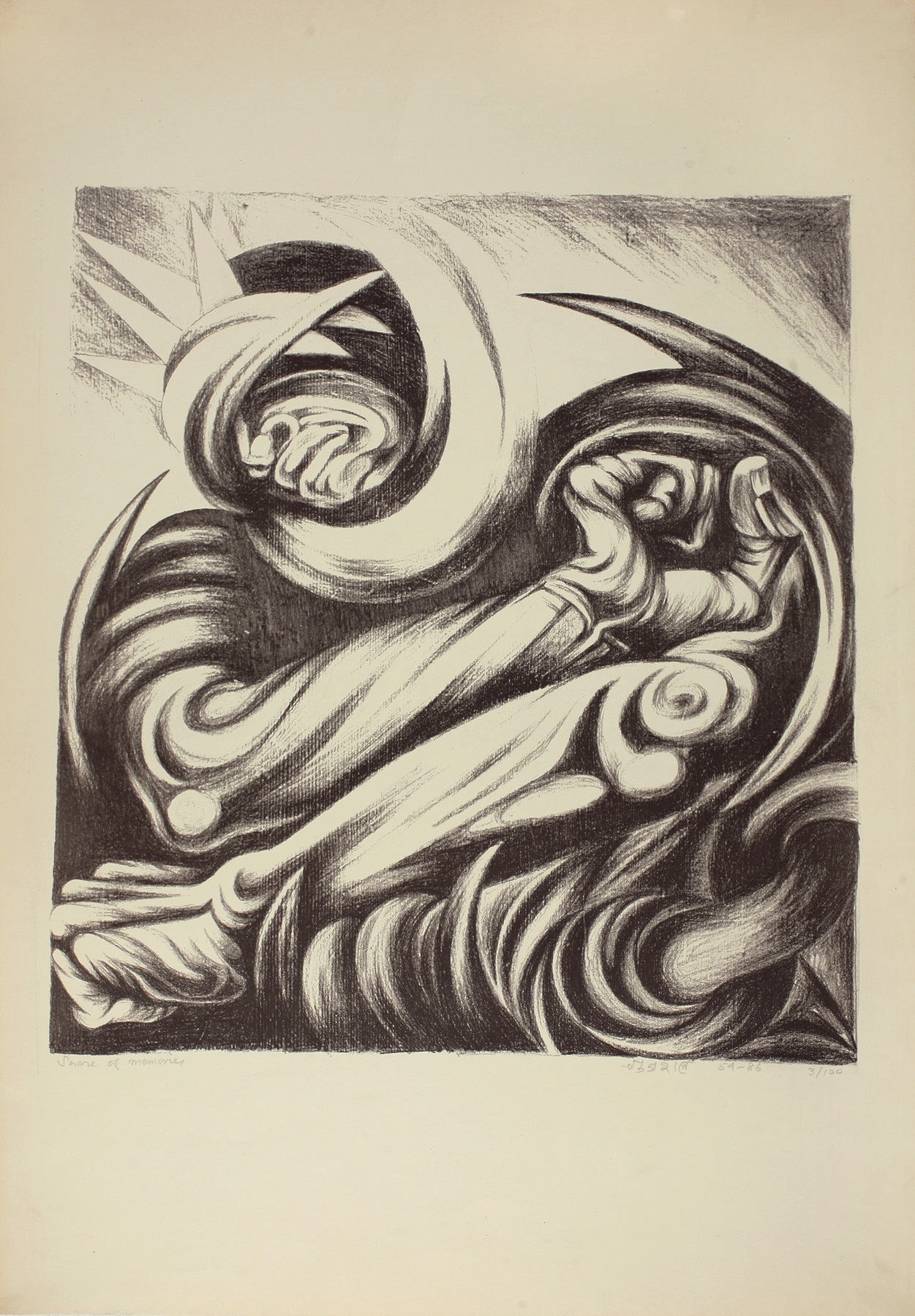

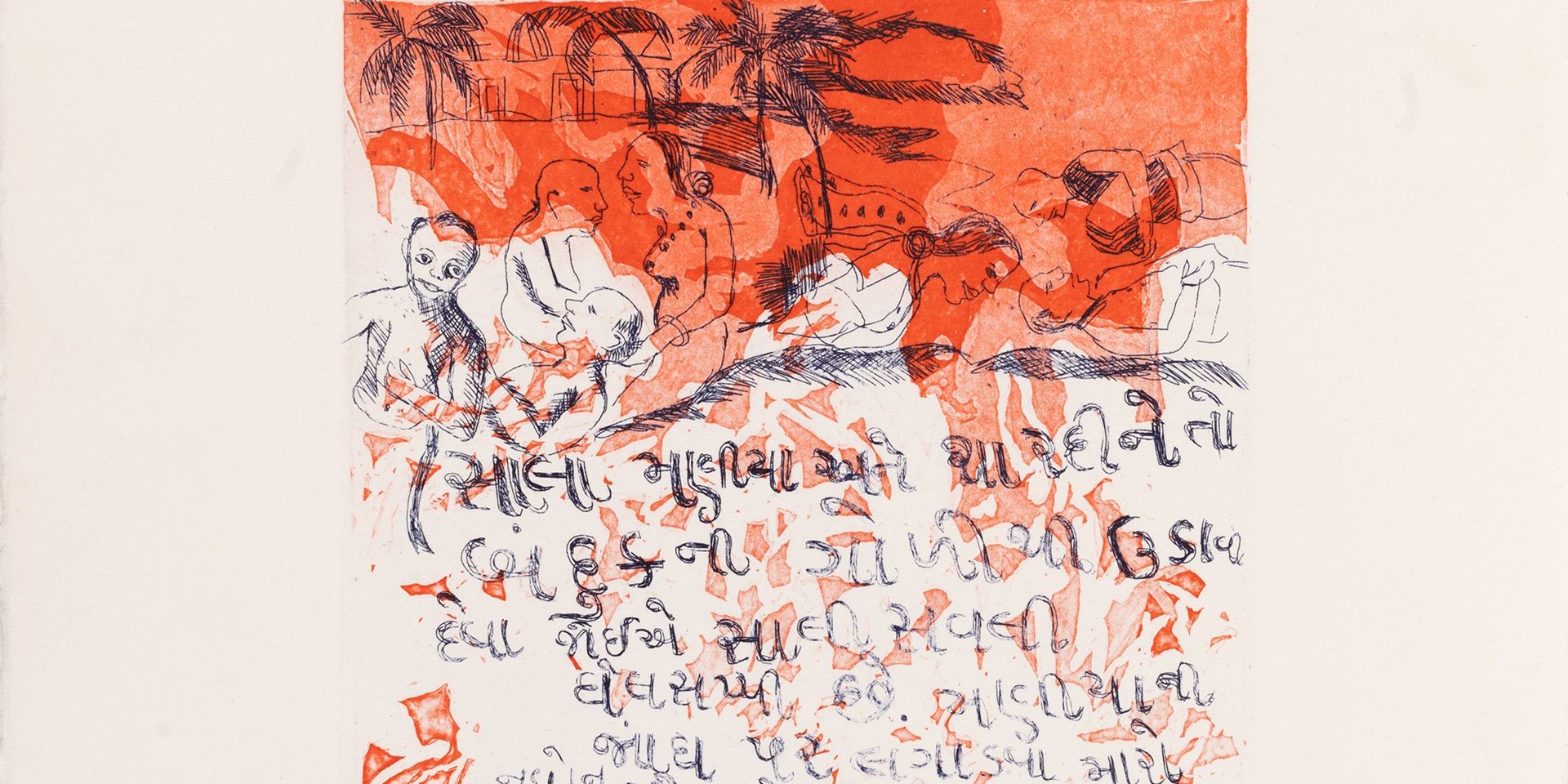

Satish Gujral, Share of Memories, c. 1954, Mechanical print on paper, Print: 19.0 x 17.5 in. Collection: DAG |

The relationship between art and Partition in South Asia allows us to pose some of these questions. As the Partition of 1947 left lasting scars on the subcontinent, both culturally and psychologically, artists from the region have long engaged with the trauma of separation, using their work to explore the violence, displacement, and loss that accompanied the division. In India and Pakistan, many artists, particularly those who experienced the partition first-hand or came from affected communities, whether across the northern borders of Punjab or the eastern one of Bengal, created works that expressed the collective grief and dislocation caused by the event.

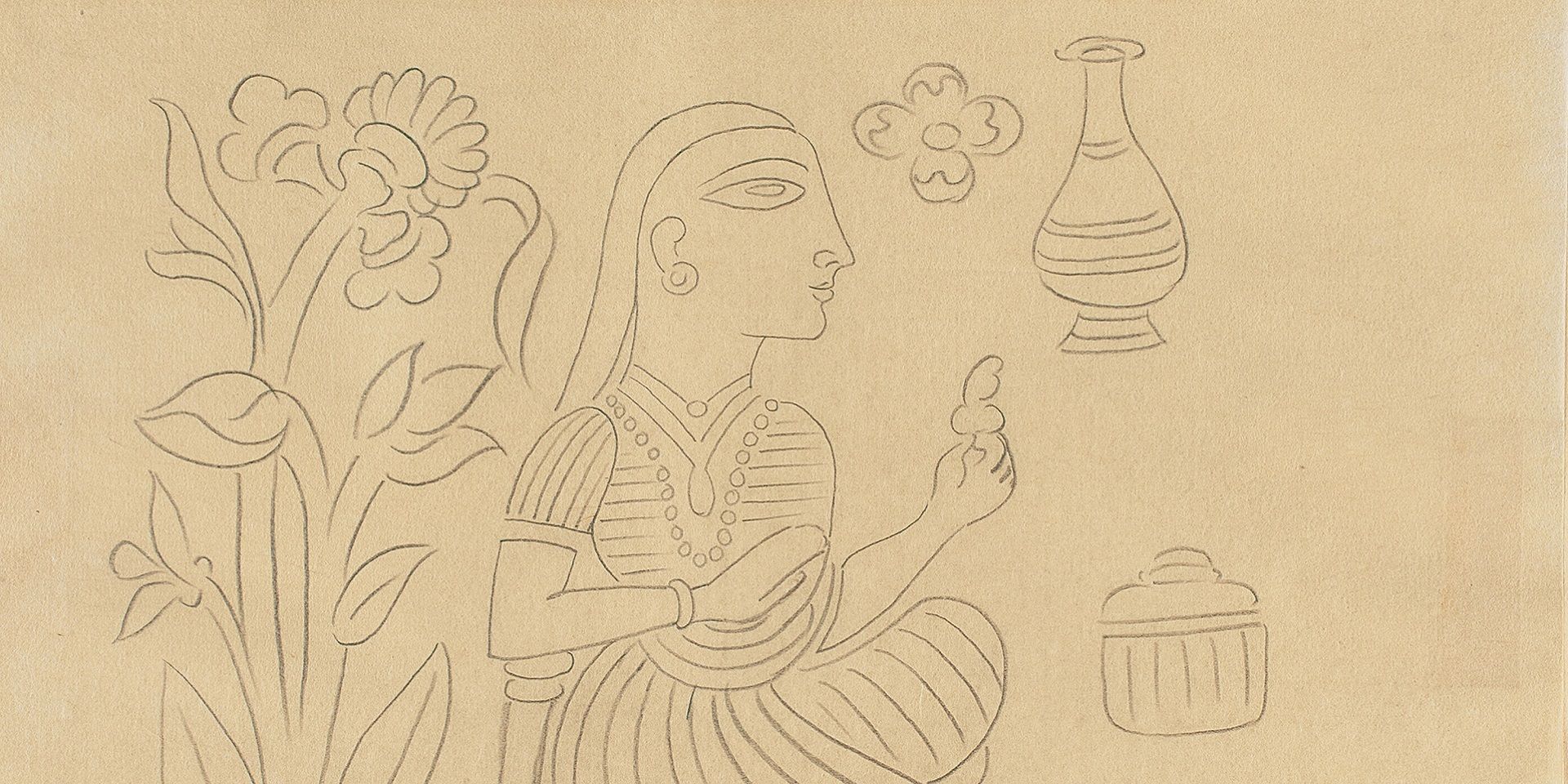

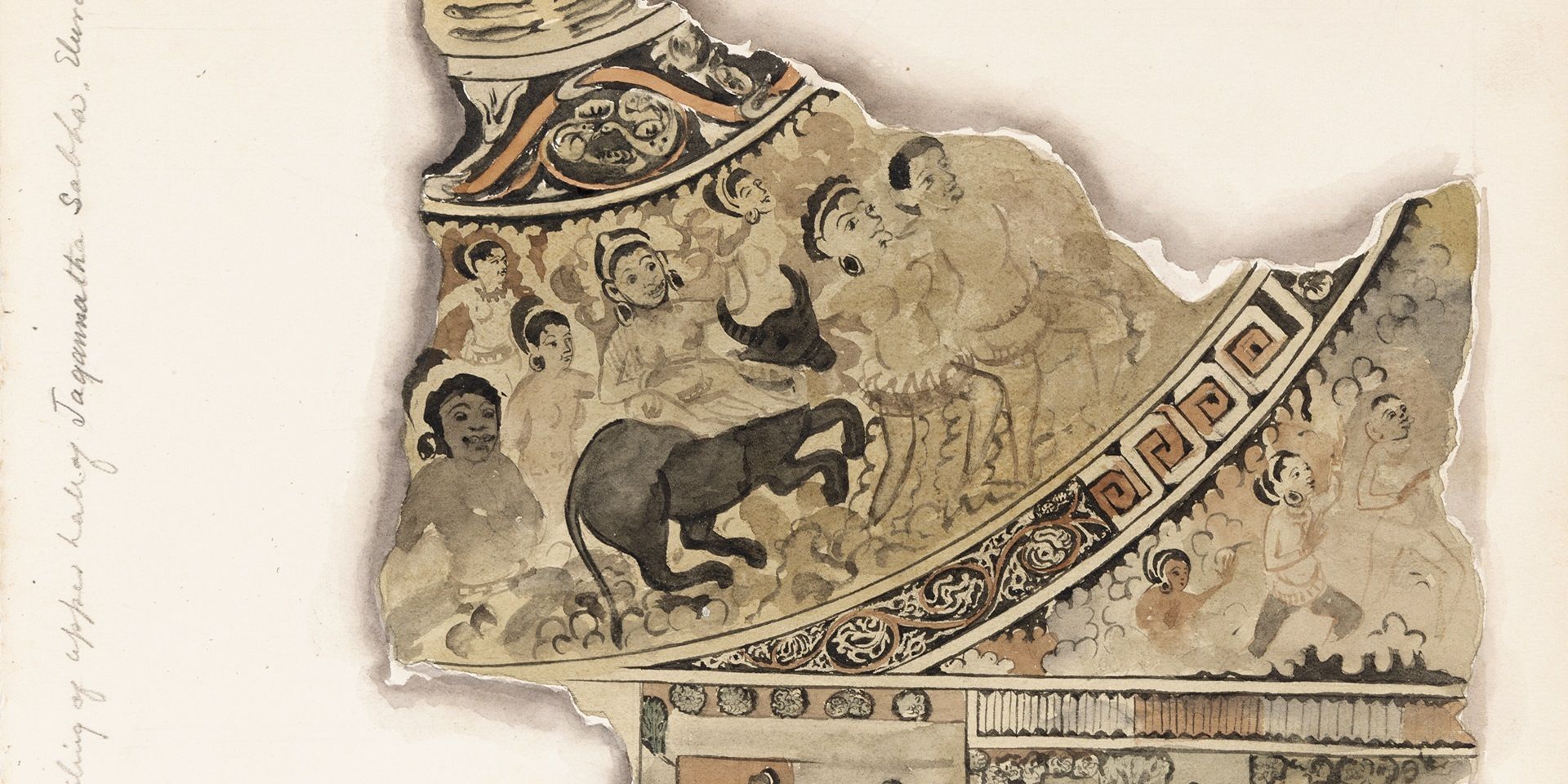

Chittaprosad, Untitled, c. 1950, Watercolour on handmade paper, 15.0 x 22.0 in. Collection: DAG

Thus, memories of displacement that can feed ideas of loss and home, is central to the work of artists affected by migration. One of India’s best-recognised modernists, Ganesh Haloi, faced an uncertain future when he was displaced from his home in East Bengal’s Jamalpur. He had lost his father in the violence that accompanied Partition and found himself being moved from one refugee camp to another across the new state of West Bengal, with the imminent threat that they might be sent even further away from the land and language that he was familiar with constantly hanging over them.

|

Ganesh Haloi, Untitled, 2004, Acrylic on canvas, 33.5 x 35.7 in. Collection: DAG |

He writes, ‘Branded as refugees, dependent on the mercy and charity of others, I saw these people change over time. From being mute recipients of largesse, they began to assert a voice for demands—and eventually, claimed rights. In spite of these changes, I continued to dream. No one shared my dreams, however. I felt extremely lonely. When we left our country (desh) I was carrying some paint, colours, paper and board from the wood of a jackfruit tree—and used them to draw occasionally. One day, a Bengali officer from the Rehabilitation Committee arrived in our camp to supervise its activities. He saw some of my paintings and said that I should join the art school. He said he would arrange a scholarship through the refugee quota. But it was not possible to do that at the time.’

Ganesh Haloi, Untitled, 1992, Gouache, watercolour and acrylic on handmade paper, 16.5 x 19.0 in. Collection: DAG

Eventually, Haloi would find himself living on the platforms of the railway station at Howrah, which

he had to provide as his official address while applying for admission to the Government College of Art and Craft in Kolkata. For all the volubility of his account, full of details about where he lived and what he felt about those times, there is a greater wall of silence that refuses to blame others or claim the greatest victimhood for himself. He says at the end that ‘I am not going into the details of how I spent those years. Many others went through what I did—there’s nothing unique about it. Those of us who survived those terrible times were few, compared to the ones who were lost.’ And this is where art as a public form of reconciliation and harmony comes to the fore; a process that allows the artist as a betrayed citizen-subject to heal along with the lives of many others. Images of houses and home-like constructions recur regularly in Haloi’s work, from concrete images to more abstracted ones; and each of them point to the difficult process of healing after trauma, and the human subject’s eternal search for a home in the world. The act of dwelling in a place requires a poetic engagement with space, for ‘Poetically man dwells’ (as Friedrich Holderlin put it); and Haloi’s work is a testament to the ways in which refugees like himself constructed an imagined space for themselves in an environment that was not always kind or welcoming. In fact, the historian Anwesha Sengupta quotes contemporary accounts of the people of Kolkata reacting with pity and horror at the sight of platforms filling up with refugees. A certain Ila Sen wrote a letter to the editor of The Times of India, observing:

‘Calcutta has its own Frankenstein—the four and a half million refugees …are now holding the city at ransom. It is impossible to enter from any direction without climbing over their heads. They are in possession of the railway stations. Desperate and despairing, this is a classless society. Each one has been ground down to bear an identical face—a face from which all distinguishing marks of education, culture or occupation have been effaced. No longer it is possible to tell the school master from the postman…. At Sealdah station, on the east side of the city, the counter marked ‘Reservation’ is like some island in a vast sea of ragged filthy destitution. The clerk and his clients are separated by thick masses of humanity.’

Satish Sinha, A Refugee Camp in South Calcutta, 1946, Watercolour and ink on paper laid on cardboard, 10.0 x 14.7 in. Collection: DAG

Sengupta writes, ‘Perhaps, it was not only the numbers, but the fact that ‘distinguishing marks’ like culture and education had been ‘erased’ and rendered the entire population as one hapless bunch of refugees that bothered the educated elite of the city. That a school master could not be distinguished from a postman was alarming—it meant that education or culture did not matter in face of this tumultuous tragedy.’ The story of displacement would come to be told in many voices, across various communities, so that it became clearer over time that there were diverse groups of people who went through a variety of experiences. Artistic accounts instinctively highlighted this diversity of feeling and experience. In the work of artists like Satish Sinha, for instance, we can catch a glimpse of how media representations (especially in newspapers and photography) were equally influencing the artworks that sought to observe the details of refugee arrivals.

|

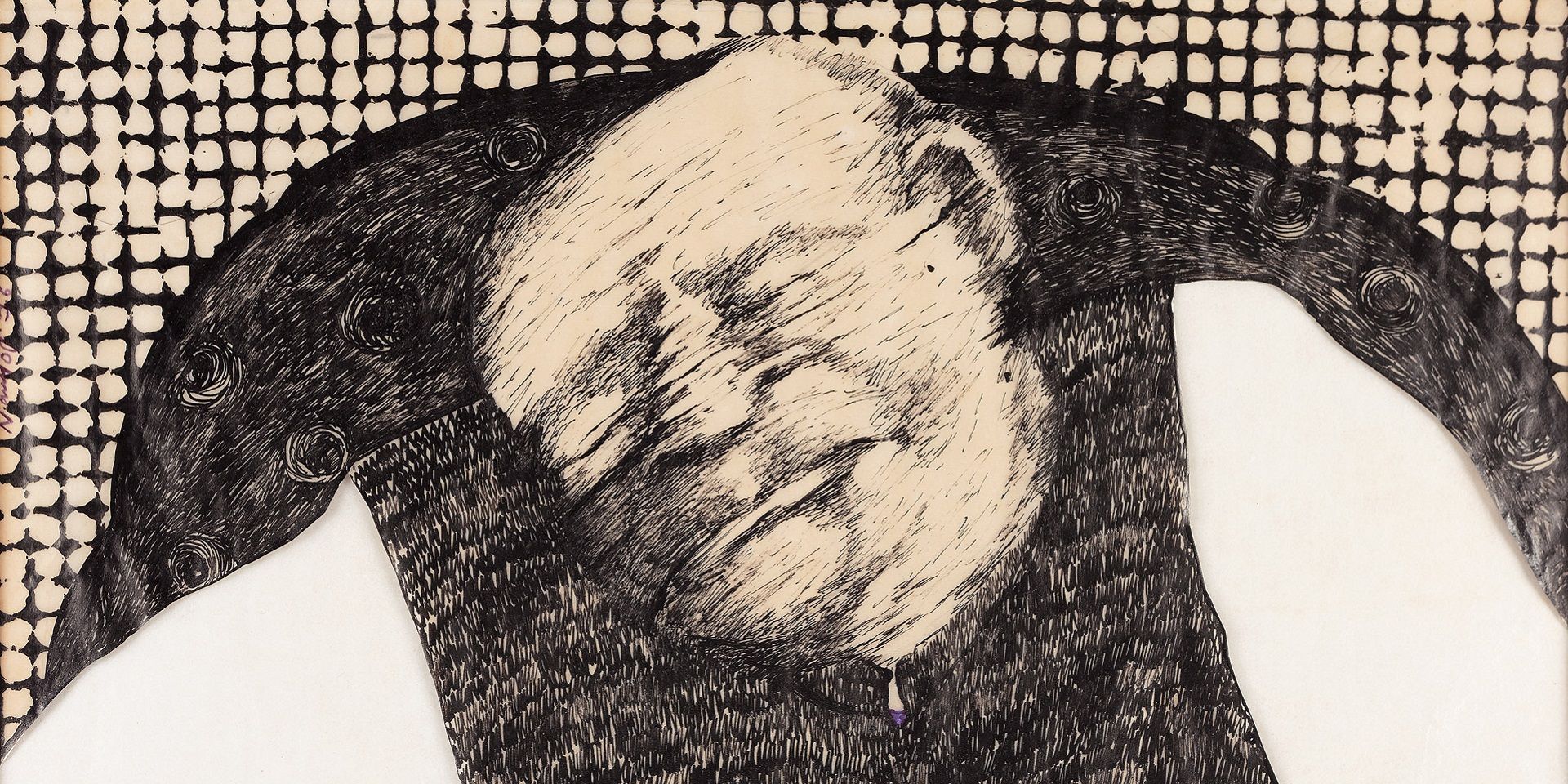

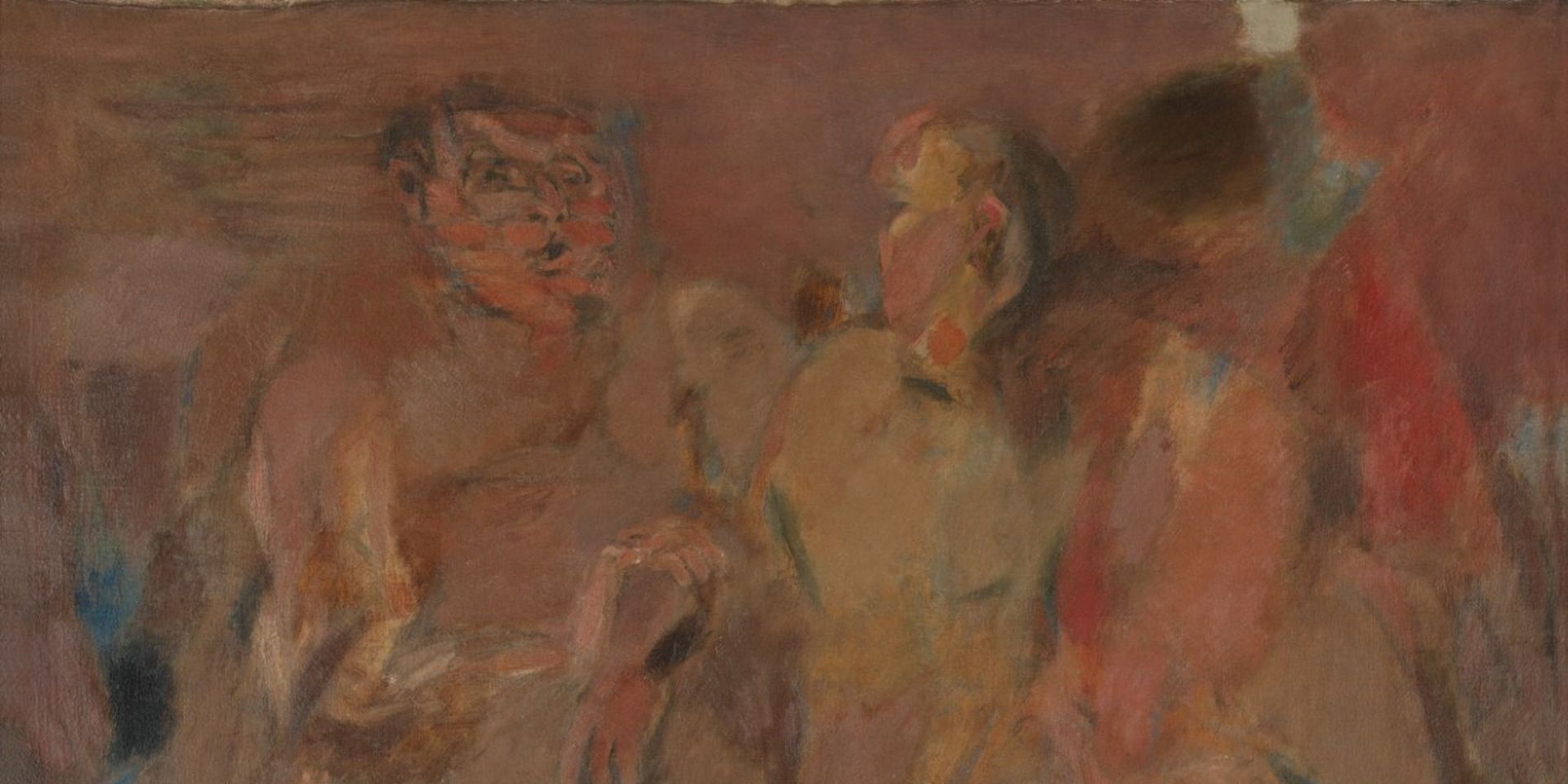

Jogen Chowdhury, Untitled, 1959, 16.2 X 12.7 in. Collection: DAG |

More recently, the art historian Soumik N. Majumdar has observed that ‘(a) few years back, Jogen Chowdhury completed a large work on paper called Partition 1947. Perhaps for the first time, Jogen titled a work with a straight allusion to the theme of 1947 Partition, a theme that has haunted him throughout. Yet, until this work, one cannot find a single known work by him that carries such a direct reference to this subject, right from the title.’ Chowdhury’s newer work that directly refers to the Partition might indeed signal a new departure rooted in old memories, but it wouldn’t be wrong to suggest that the trace of that traumatic event can be discerned in many works he has made earlier. More than a trace, his sketches of refugees crowding the Sealdah Railway Station, for instance, directly refer to the original violence and depredation of a time that has since been formalised and disciplined by historical narratives and cultural reactions. Chowdhury’s sketches, executed in the 1950s when he himself had been forced to migrate to Kolkata and had just been admitted to the Government College of Art and Craft, reveal the dark irony of a student-artist practicing his modelling sketches by drawing directly from the open wounds of the city.

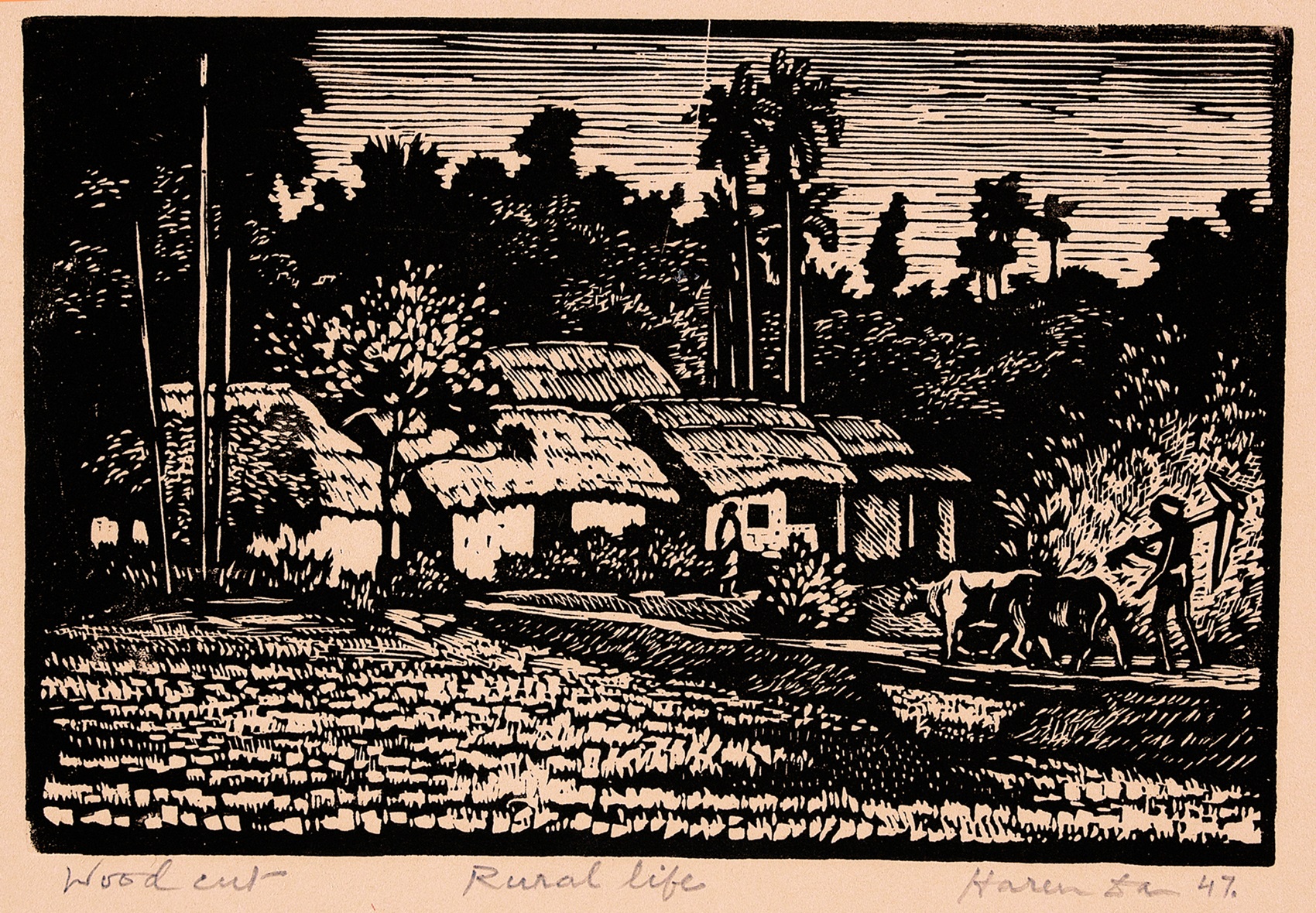

Haren Das, Rural Life, 1947, Woodcut on paper, : 4.2 x 6.2 in. Collection: DAG

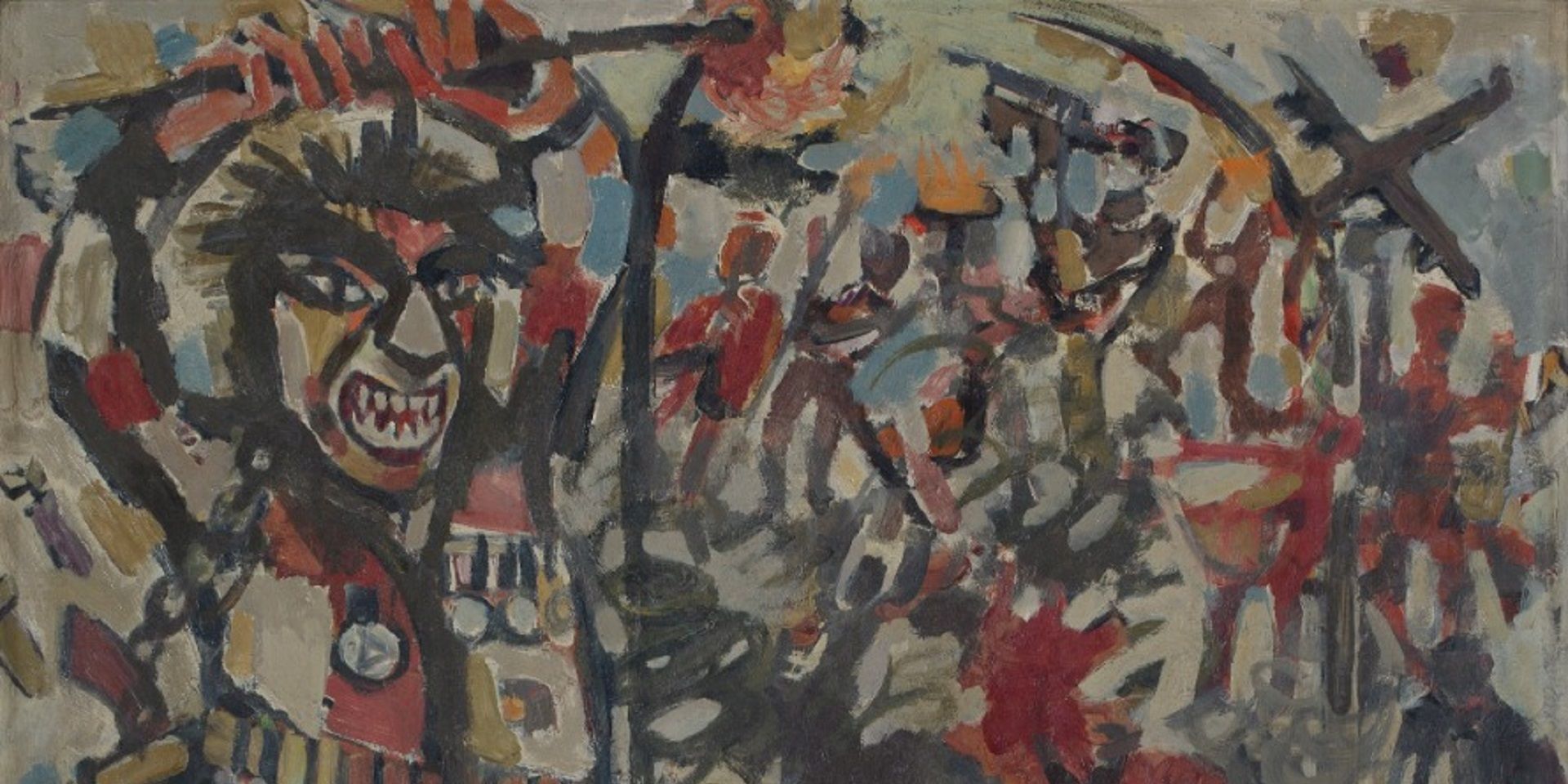

However, partition's impact on South Asian art has not been limited to representations of loss and trauma. It also gave rise to the search for new forms of artistic expression, with artists navigating the complex terrain of national and personal identity in the aftermath of a violent rupture. For artists of an earlier generation, such as Paritosh Sen or Haren Das, the response was markedly different. Das, who came from the Dinajpur district in modern-day Bangladesh, continued to depict the rural idylls he was to become well-known for making. These idealised landscapes of rural (East) Bengal, played an important part in the wounded psyches of those who were being forcibly displaced. It allowed them to carry an idea of home with them and offered a psychic salve when they were confronted with the disharmony of their immediate lives in temporary shelters, refugee camps and forcibly settled land.

|

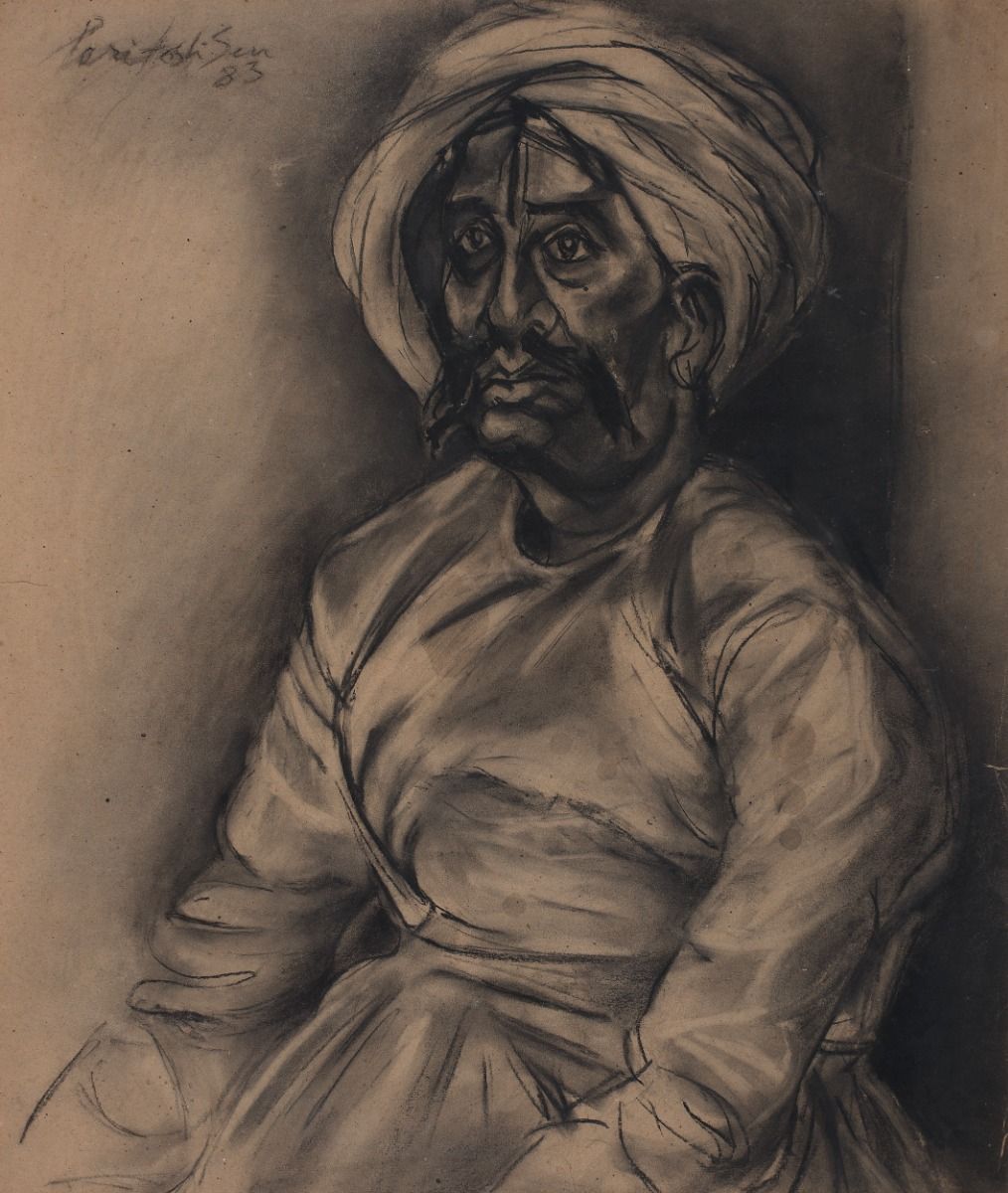

Paritosh Sen, Untitled, 1983, Charcoal on paper, 29.5 x 25.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Dislocation, in such accounts, becomes a possibility for reimagining the world and creating new forms of belonging that go beyond the boundaries of nation, culture, and identity. This doesn’t have to entail a corresponding will to forget the past either. In Paritosh Sen’s autobiographical writings, he narrates the life of a neighbourhood in Dhaka—called Jindabahar Lane—where he grew up in the early decades of the twentieth century. Full of closely observed details of the natural landscape and the characters that were invested in the cultural life of the city, including tailors, hustlers, painters and odd jobbing men of various stripes, Sen’s intimate portraits, accompanied by his sketches, offer a glimpse of a place in time that was shaped not just by the features of a landscape, but by the people who haunted those spaces and marked them in the memories of would-be artists like young Sen. This also constitutes an archive of memories that gain a special poignancy after the political act of separation between the two nations. In his artists’ book ‘A Tree in My Village’, Sen evokes the rapturous green of the landscape he was familiar with in East Bengal, even as he writes about a grand, sheltering Arjuna tree that he encountered regularly. The Arjuna tree, where a variety of birds and insects took refuge, becomes a powerful metaphor for the search for shelter that Haloi and other artists wrote and made works about later.

Jogen Chowdhury, Landscape, 1989, Ink on paper, 4.0 x 6.2 in. Collection: DAG

Artists resorted to various means while representing their experiences of loss due to Partition. From naturalistic accounts that serve as documentary evidence from the time, artists moved on to make abstractions that were equally informed by the changing shades of memory as those traumatic events entered historical accounts and political narratives were drawn out of them. Paritosh Sen invokes Mark Rothko when he casts his mind back to remember the landscapes of his childhood—seeing it as a green wash; and it informs his subsequent experiments with modernist painting. As we still account for the variety of losses that were accumulated by Partition, artists have sought to become empathetic guides through such darkened landscapes.

The central crossroads of Netaji Nagar, established as a refugee colony in the late 1940s, is decorated ahead of the celebration of its founding anniversary. A statue of a refugee family marks the crossroads, left of centre. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

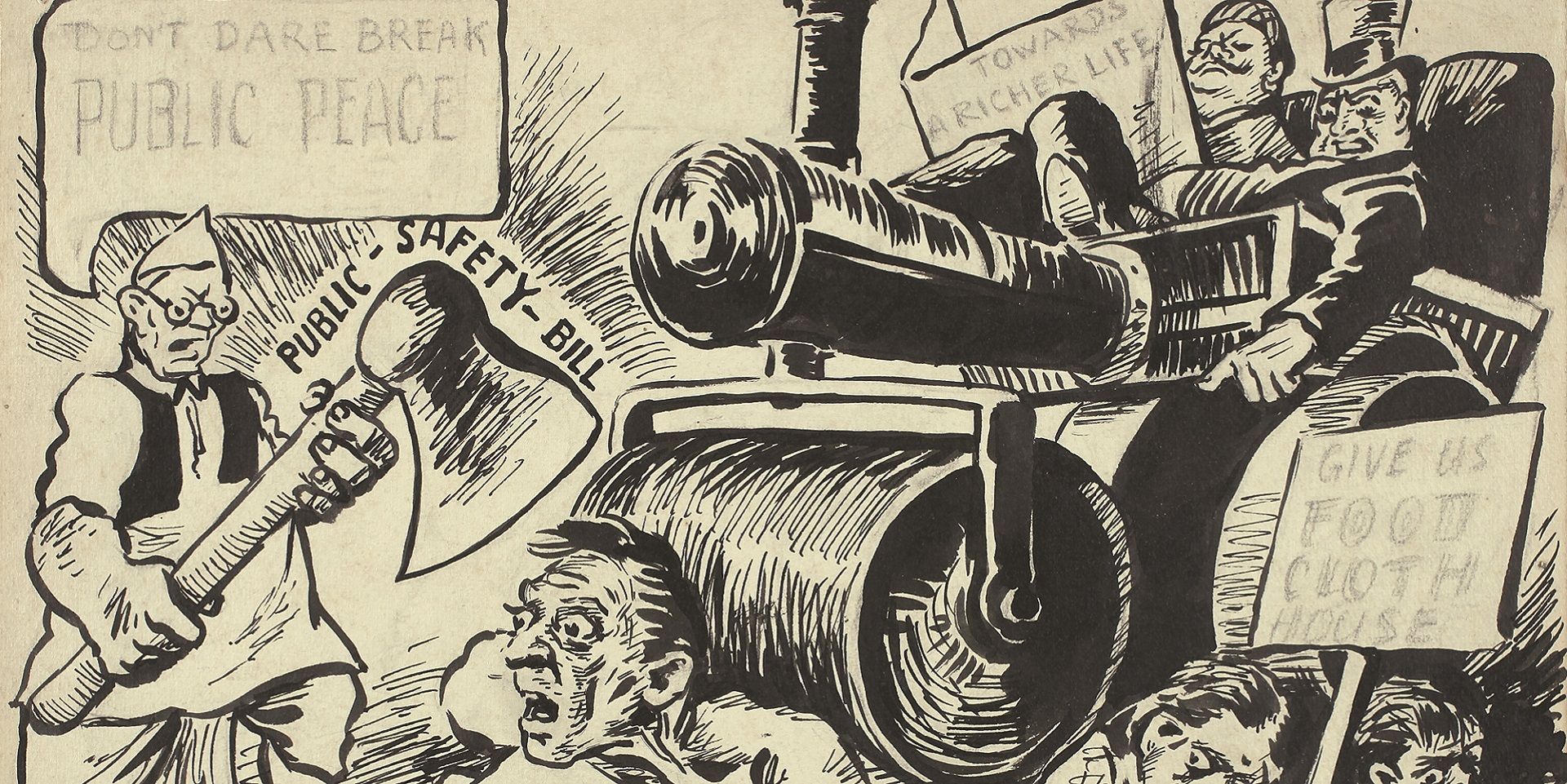

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

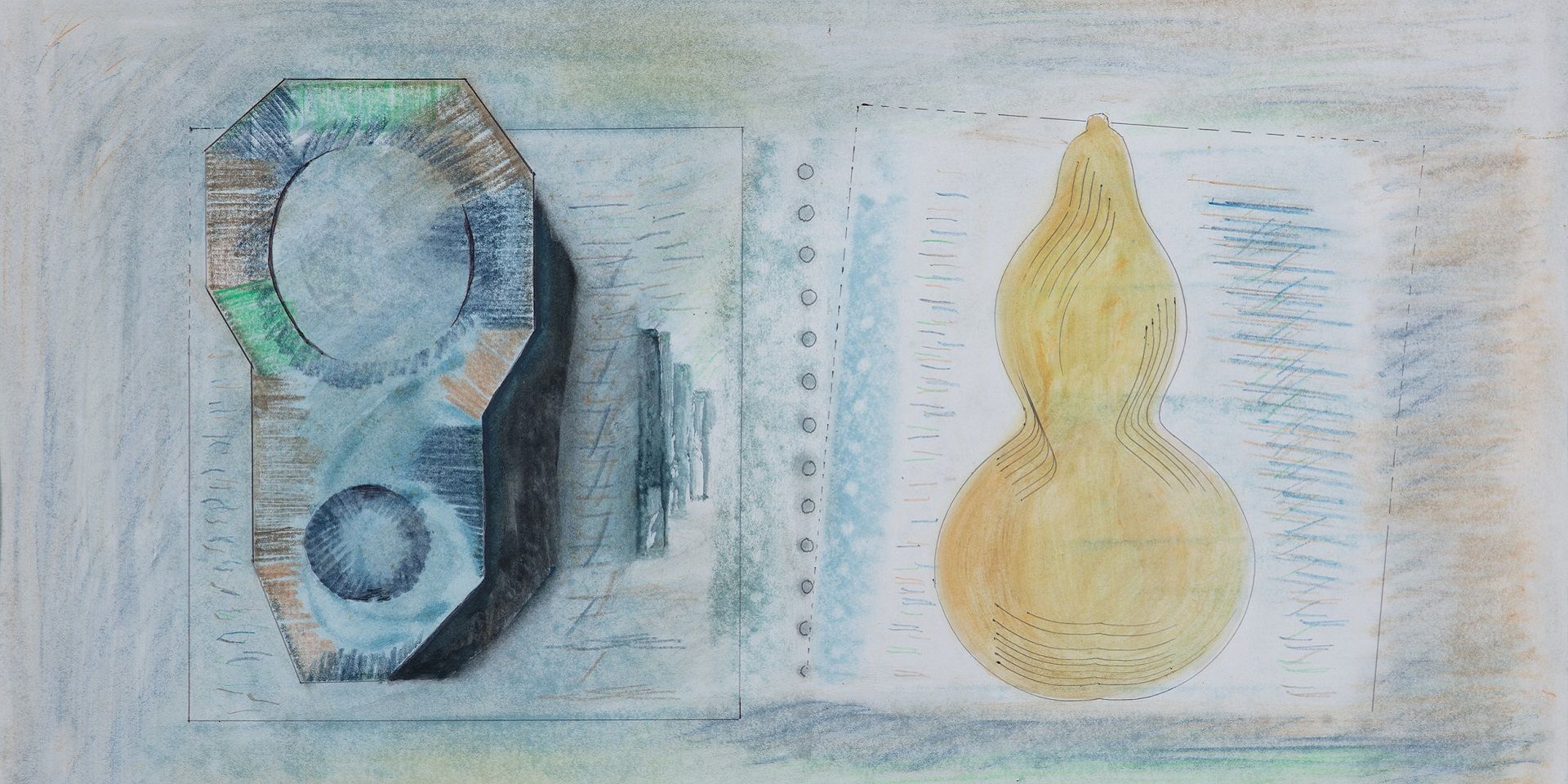

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

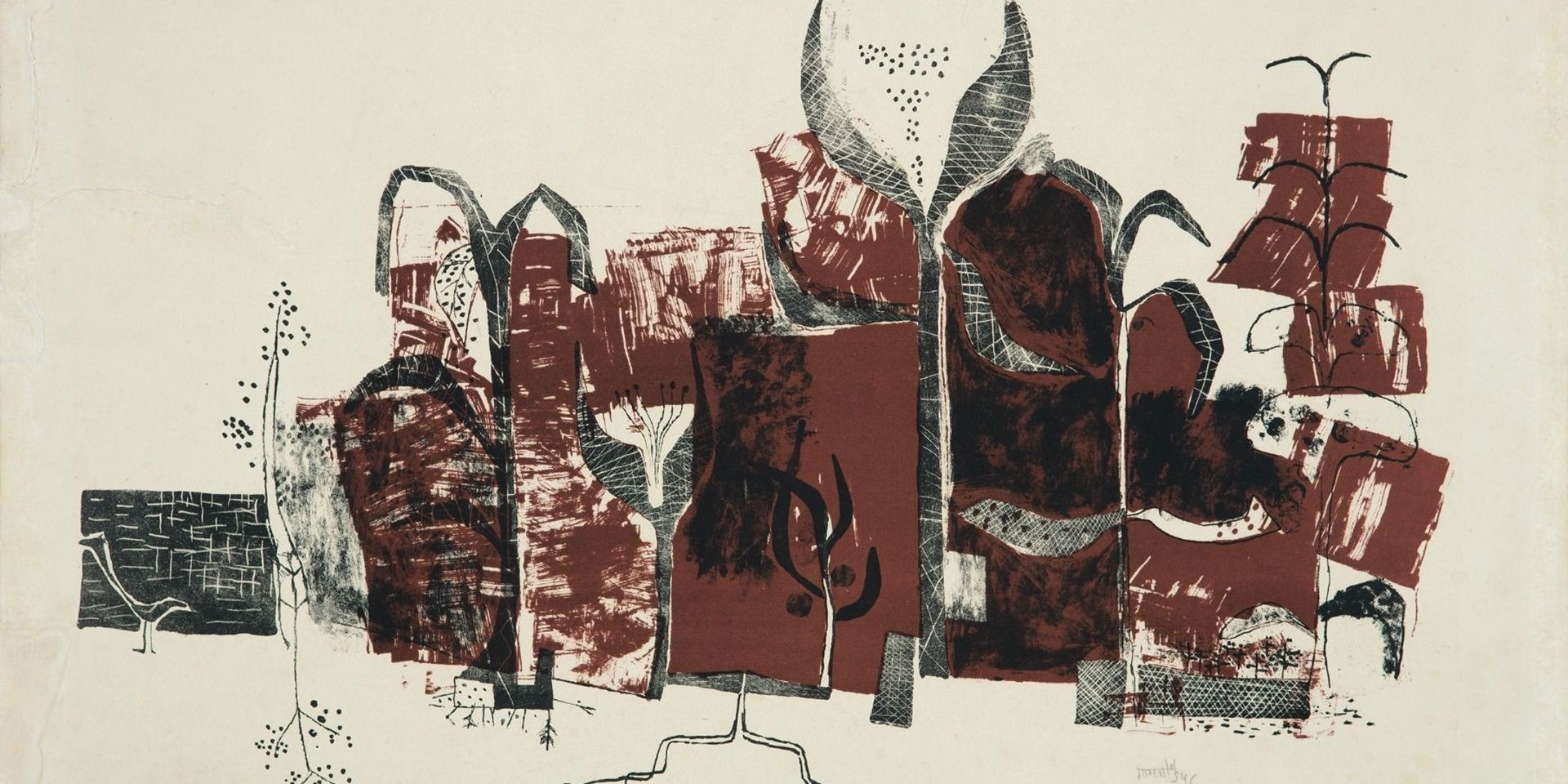

Archival Journeys

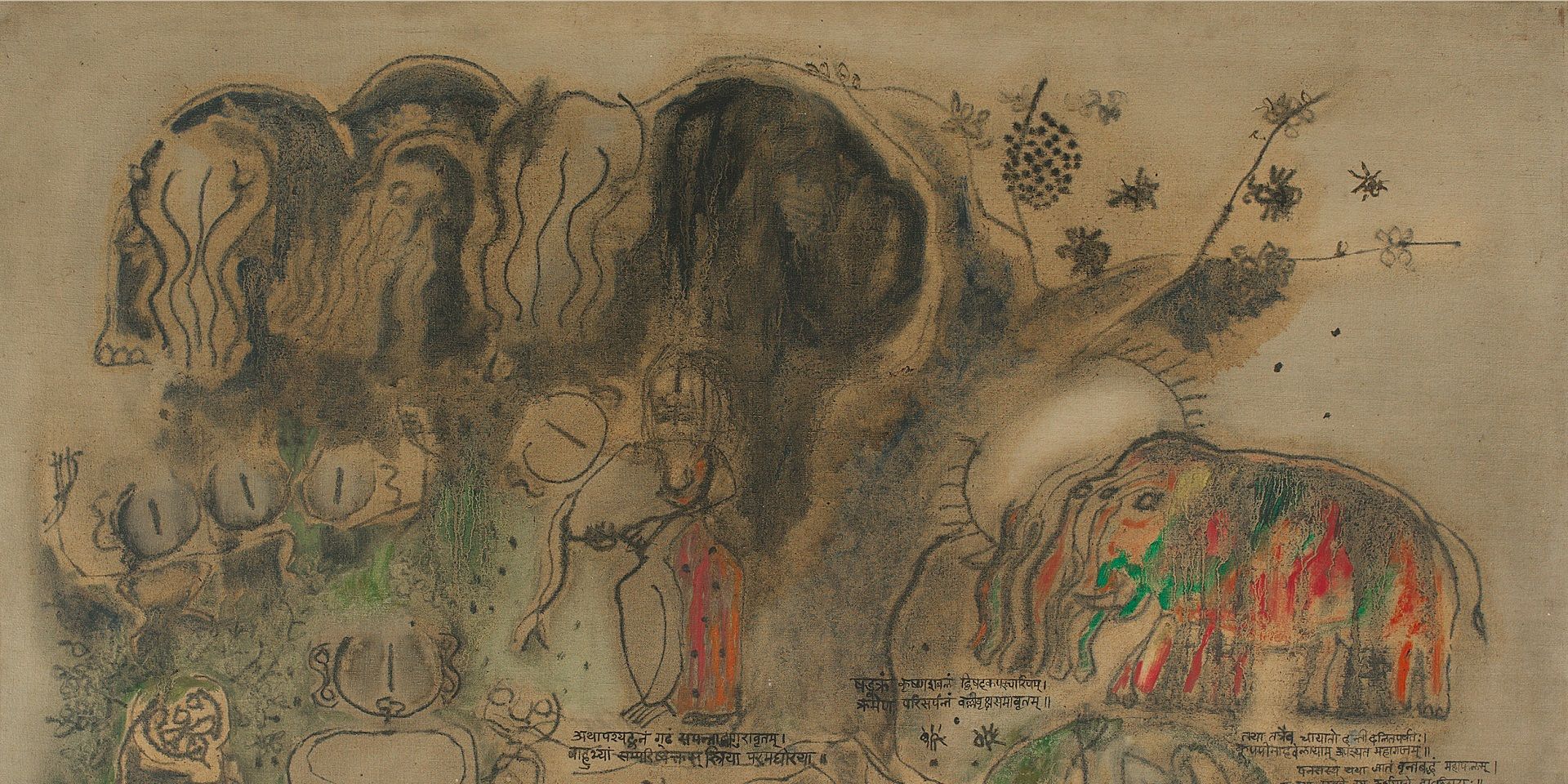

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024