Rajasthan via Japan: On Kripal Singh Shekhawat

Rajasthan via Japan: On Kripal Singh Shekhawat

Rajasthan via Japan: On Kripal Singh Shekhawat

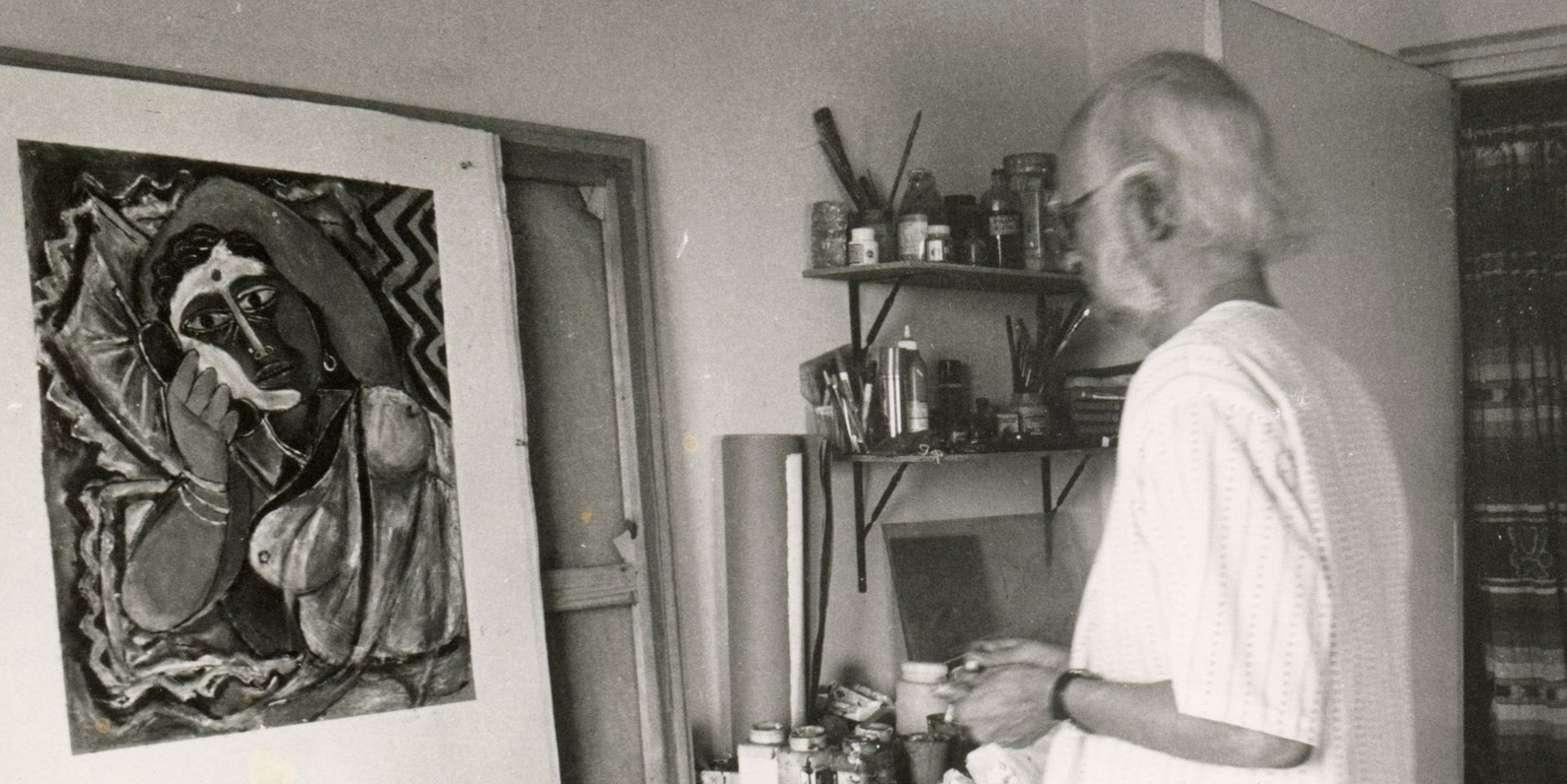

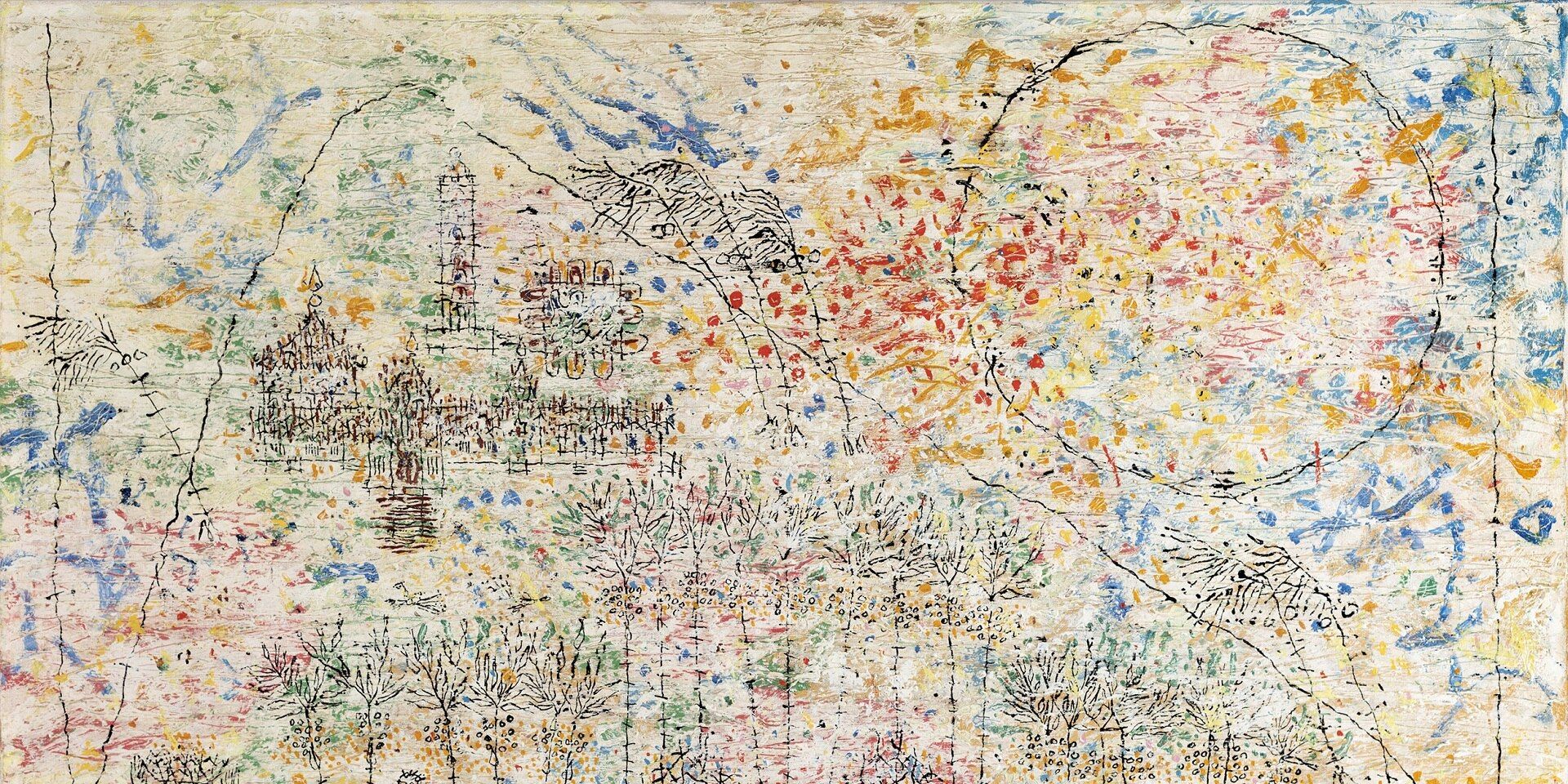

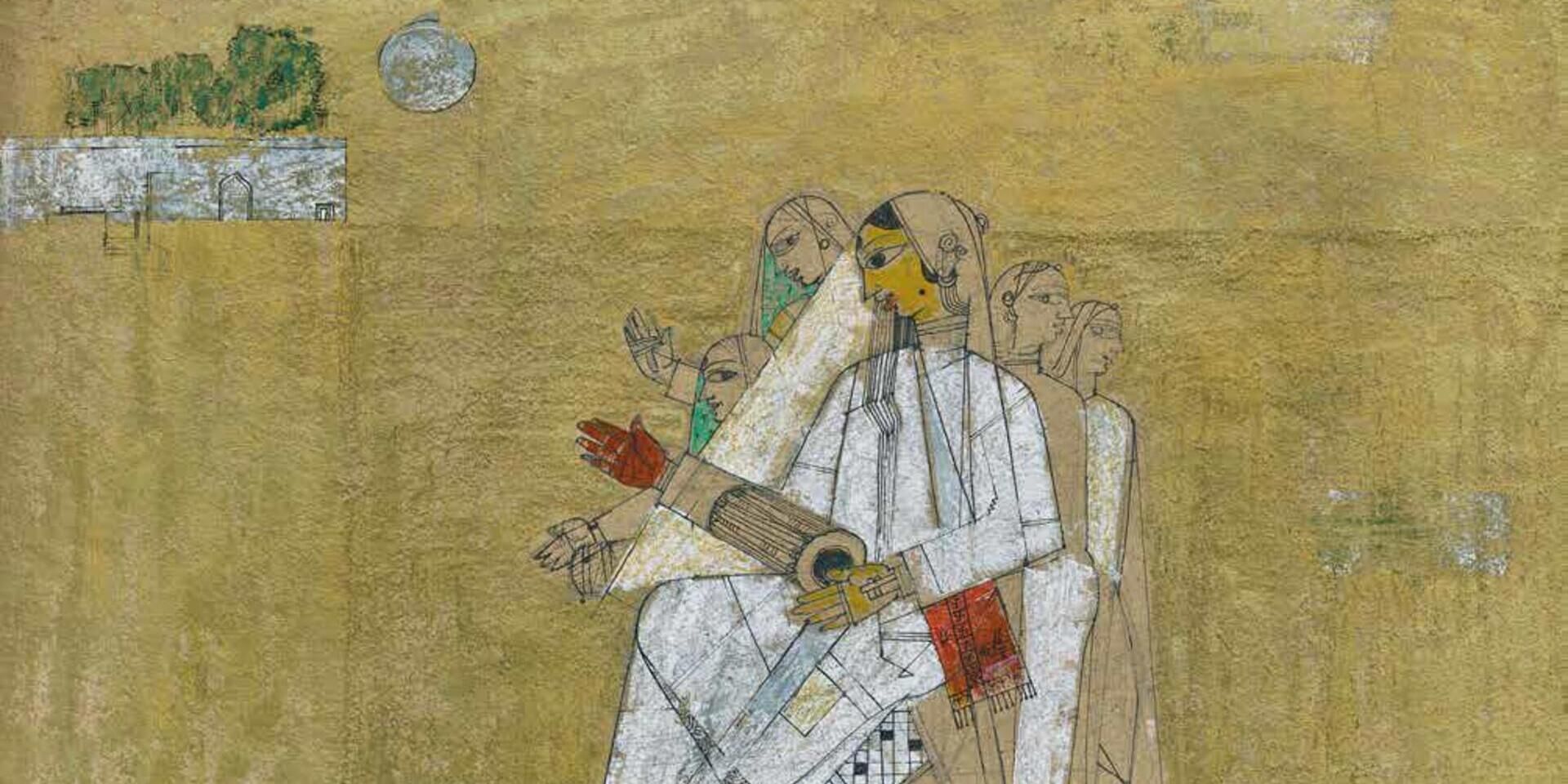

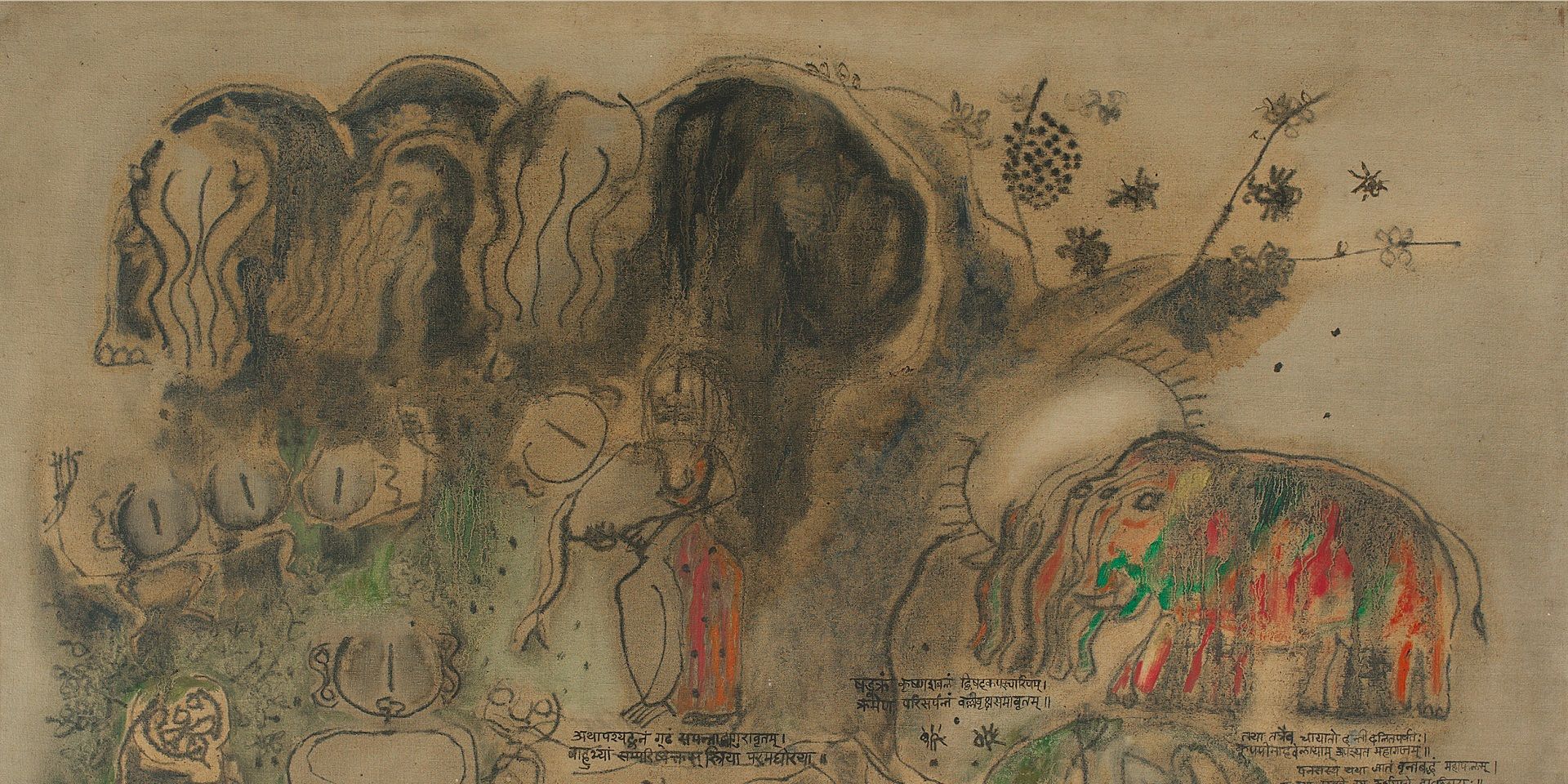

Kripal Singh, Untitled (detail), 10.7 X 9.5 in. Collection: DAG

Kripal Singh Shekhawat (1922—2008) was a renowned artist and ceramist of India, known for his skills in making the iconic Blue Pottery of Jaipur and credited with reviving that art in India. He was born in Rajasthan, studied painting at Santiniketan and was the director of the Sawai Ram Singh Shilpa Kala Mandir in Jaipur. Shekhawat received the Padma Shri in 1974 and the title Shilp Guru in 2002. How did he come to assimilate wider aesthetic influences in his work?

His time in Santiniketan exposed him to pan-Asian aesthetic influences in painting and craftworks, and he would also study for a time in Japan under renowned masters. These influences would shape the way he approached traditional practices of painting and ceramics in Rajasthan. His artistic journey reveals a captivating blend of cosmopolitan aesthetic inspirations, ranging from the intricate details of Mughal miniatures to the serene elegance of Japanese nihonga, which were two strong traditions he drew upon for his work. By doing so, he also challenges the conventional narratives surrounding the evolution of modernism in Indian art, and disrupts the traditional repository of influences presumed to have shaped it.

|

Kripal Singh, Untitled, 10.7 X 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

After finishing his school-leaving exams in 1942, Shekhawat attempted to join Santiniketan under the encouragement of his patron, the industrialist Ghanshyam Das Birla. Following a brief stint at the Lucknow College of Art, he eventually found his way to Santiniketan to study under the tutelage of Nandalal Bose, whose work he had seen previously published in several art journals of the time. As a historian puts it, ‘Nandalal Bose was much closer to the Asian visual cultural traditions of Japan and China than those of the West and was grounded in the artistic traditions of folk crafts, Ajanta and miniature paintings, all of which were absorbed by Kripal Singh.’

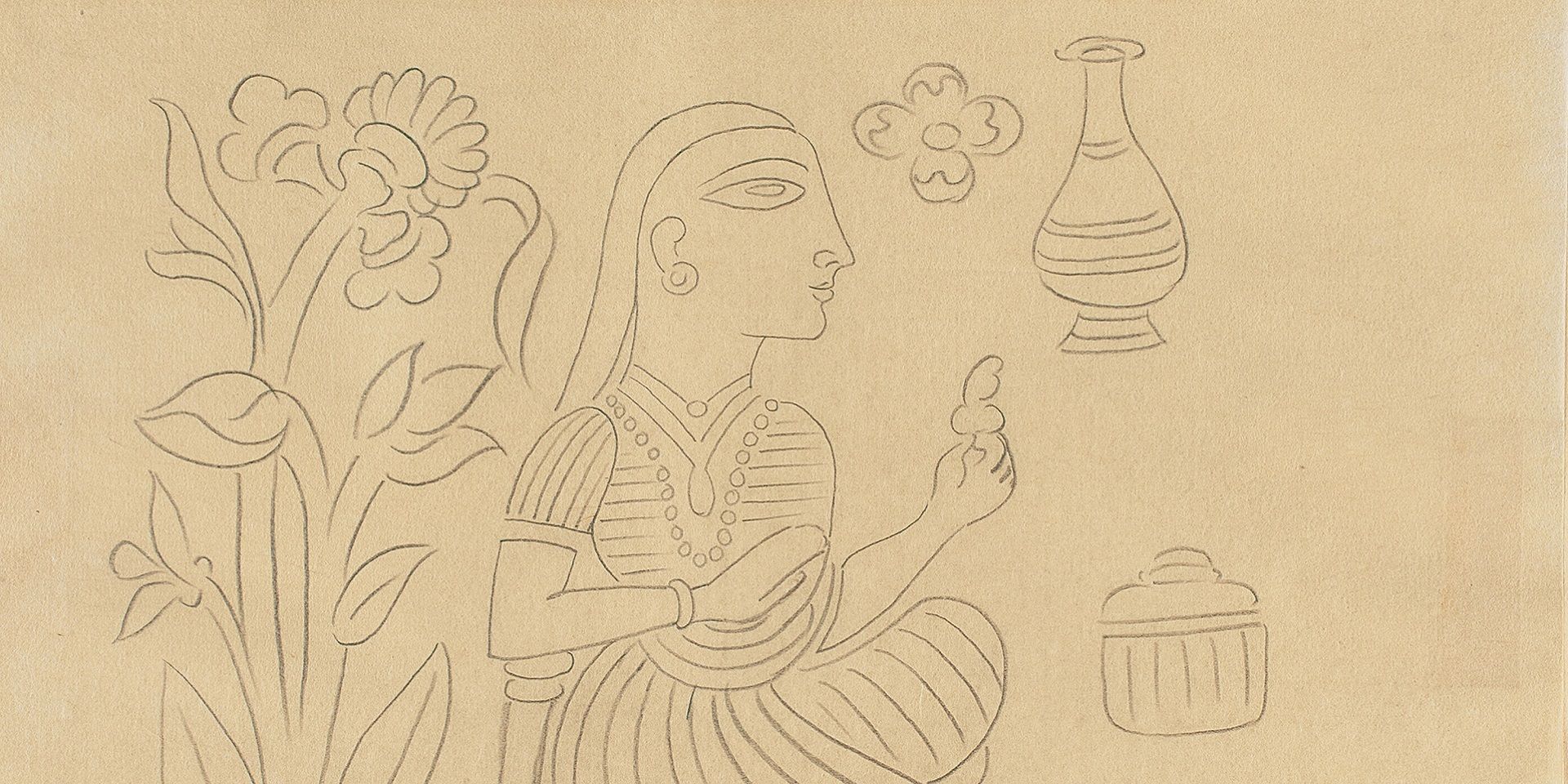

Kripal Singh, Untitled (Scroll), 14.5 X 327.5 in. Collection: DAG

Kripal Singh worked on illustrating the Indian Constitution too, as chosen by Nandalal Bose, from 1946 onwards. Bose would warmly recommend the artist on the occasion of his first solo exhibition in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1949: ‘Lovers of art will surely appreciate his technique and the wealth and grace of his colours. He has shown a special aptitude for the characteristic technique of medieval Indian art. His brush and miniature work, wood engraving and graphic art claim special admiration of connoisseurs.’

|

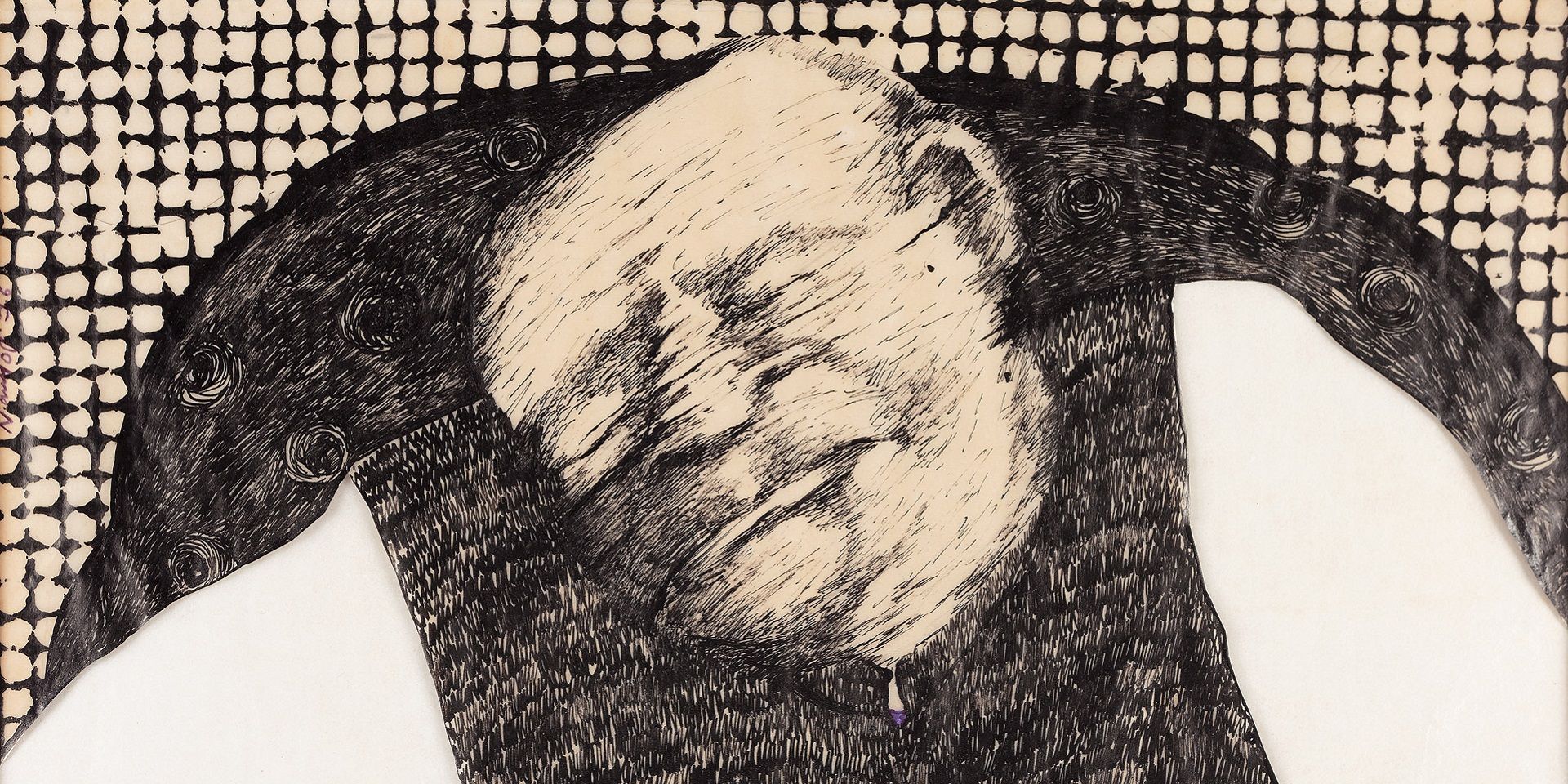

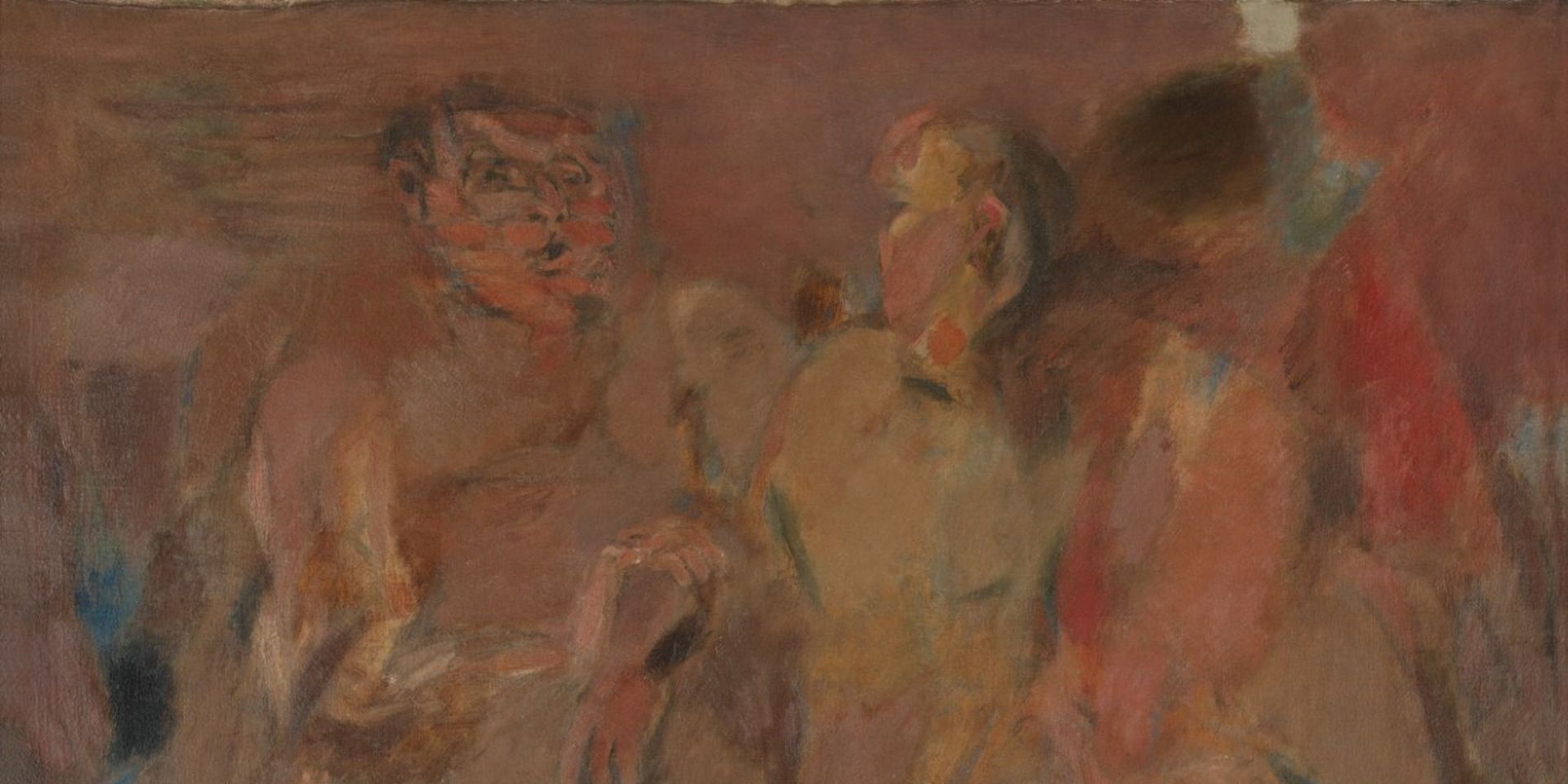

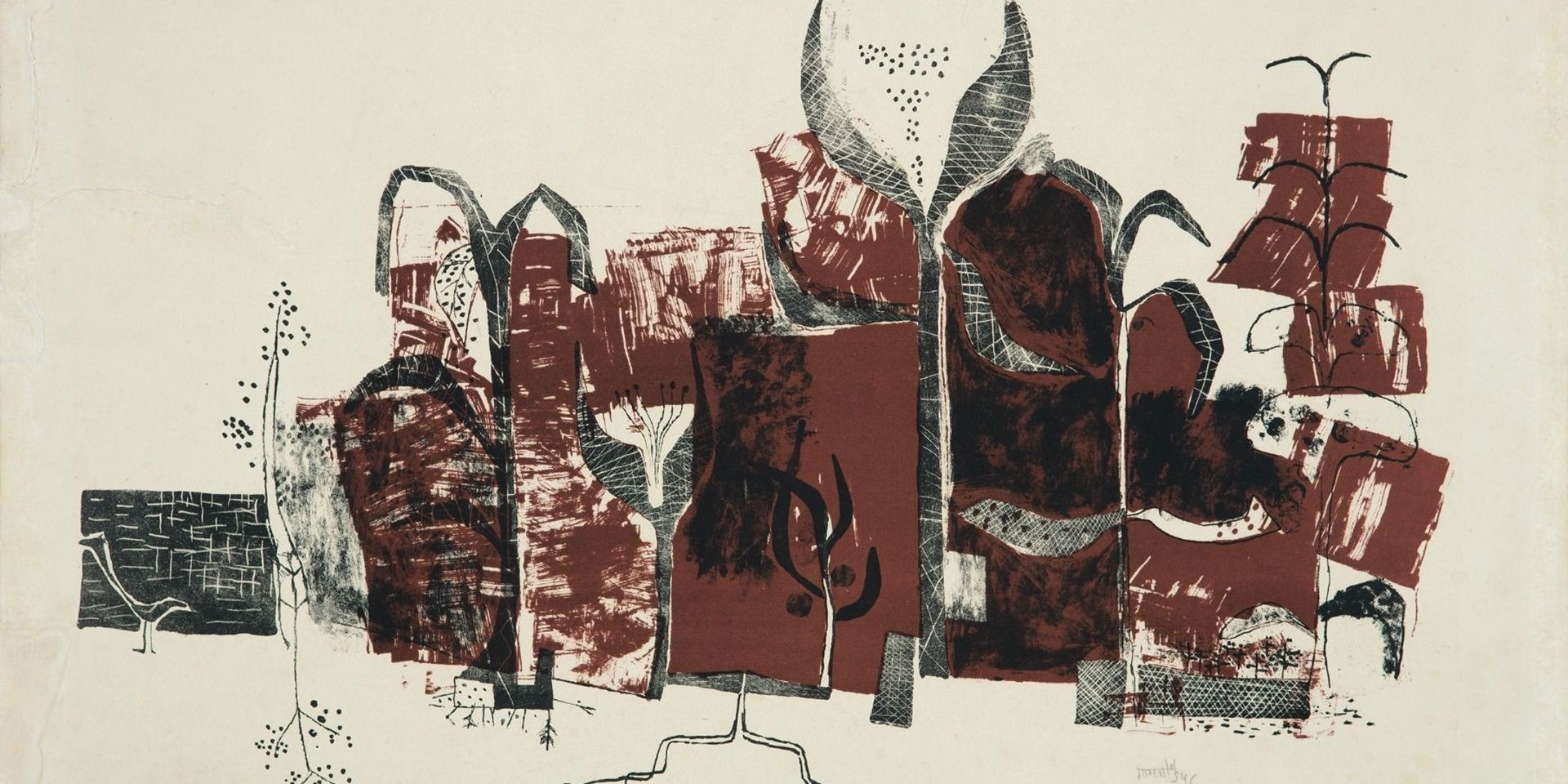

Kripal Singh, Dragon Dancer, 10.7 X 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

His proclivity towards craftwork and developing on traditional techniques pulled him towards several influences from the Japanese tradition. Following the travels and exchanges from a few generations earlier when Okakura Kakuzo first arrived in India, these aesthetic ideals had already been percolating in Santiniketan’s artistic environment for a while. As Kristine Michael writes, ‘…Singh was (…) exposed to the long shadow cast by the combined influence of the Japanese mingei craft theory and the Western arts and crafts writings on the idealized notion of the craftsman which lead to the modernist studio pottery movement in India. Mingei theory was Soetsu Yanagi’s cultural hybridization of arts and crafts theories into the shared common ground of Japanese indigenous context in an original manner. These dealt with the principles of beauty, aesthetic theories and modernist ideas which enthusiastically looked to Japonisme as its inspiration. With such exposure to Japanese aesthetics, techniques and ideas, Kripal Singh again turned to his benefactor, G. D. Birla, for fulfilling his aspiration for further training in Japan. He was accepted at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts for a two-year training in traditional oriental painting and decoration. On his way to Japan, Singh travelled overland through Burma, Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong where he did many sketches of daily life.’

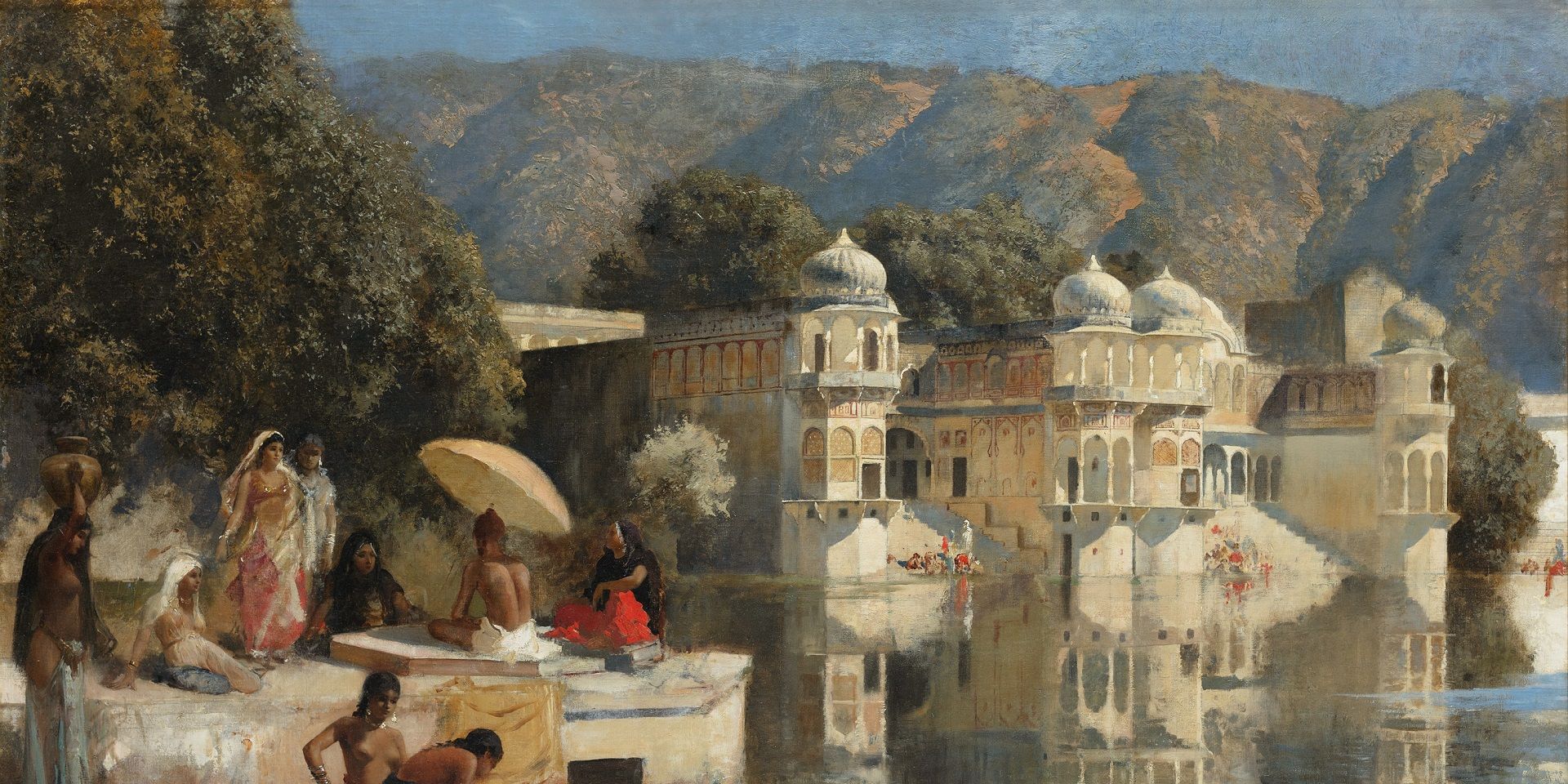

Hishida Shunsō, Hydrangeas, 1902, color on silk / framed. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

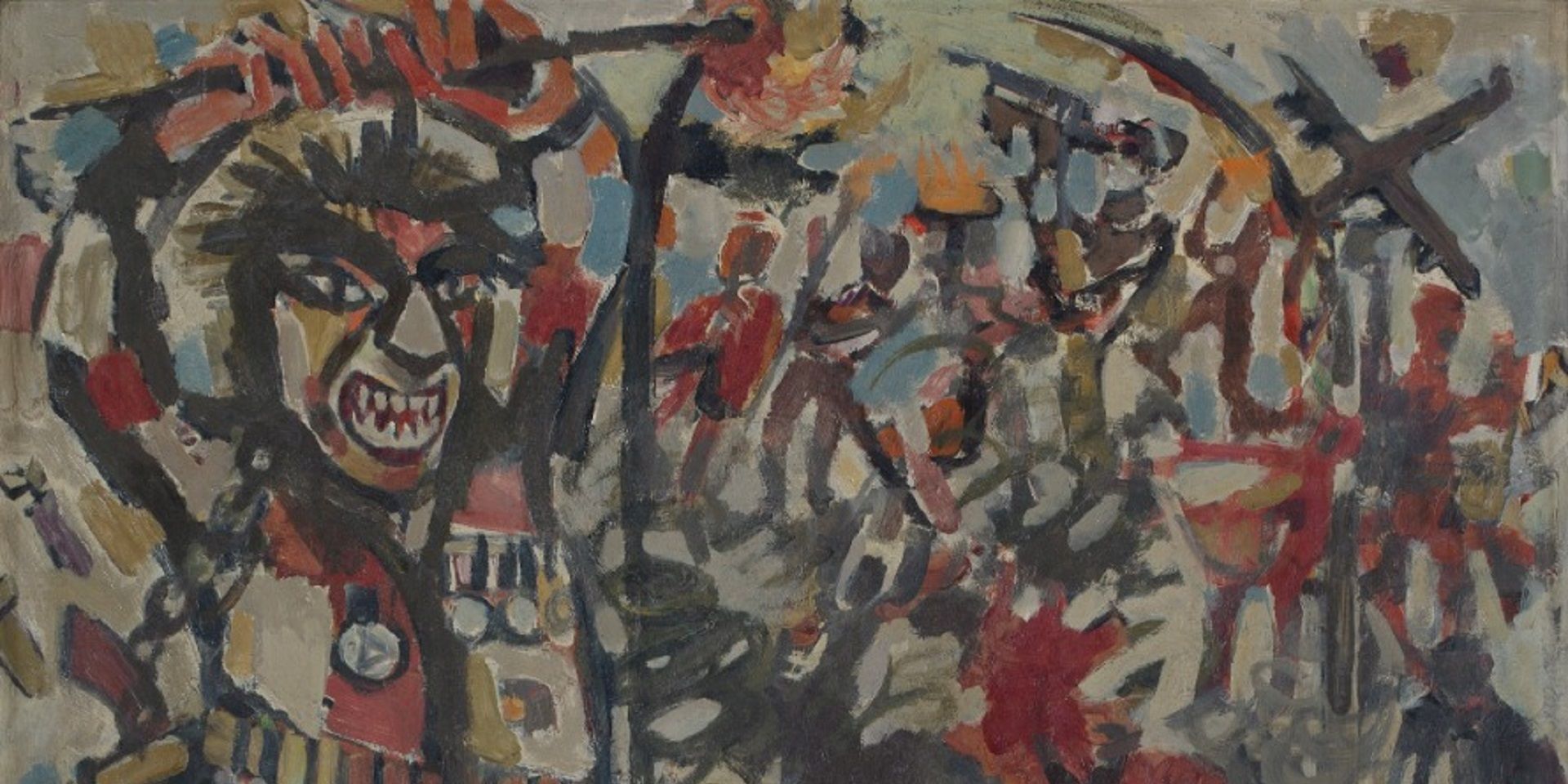

In Japan (he went there in 1951), Singh studied under figures like Mayeda Seishi; and Kawabata Ryushi, another intriguing figure in Japanese modernism who was initially trained in western-style academic realism (which he learned in the United States), but who eventually turned increasingly towards the nihonga style. However, his position across what we tend to perceive as two distinct traditions of painting led him towards a more ambivalent, complex synthesis instead of a simple replacement of one with the other. As a historian writes, ‘Critical of the strict nihonga conventions that restricted expression, Kawabata established his own nihonga organization, Seiryusha (Blue Dragon Association), in 1929, and continued his defiant efforts to destroy the framework of the nihonga art world.’ We read about similar artistic trajectories being forged by South Asian artists too, balancing the many-layered influences that we broadly describe as western and academic, or Indian and oriental, for instance, in order to respond to an artistic call that went beyond nationalism. In the case of Kripal Singh Shekhawat too, these influences can be mapped and the multiple vectors of a cross-continental modern artistic project assumes shape even as it acknowledges the conditions of Euro-American imperialism that either enables or actively encourages opposition to its own venerated traditions.

|

Kawabata Ryushi, Bomb Exploding, 1945. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Singh’s adaptation of Indian and Japanese styles required almost physical adjustments of his body movements, especially due to the increase in the intensity of focus trained upon his hands for the close work. ‘…Singh used a combination of paper from Sanganer,’ as Michael—who had also worked with the artist—writes, ‘often going himself to the paper factory and having paper made to his specification as well as using Japanese paper that he imported. The sumi lines in the Ramayana series show us how close to perfection Kripal Singh’s hand and control of brushwork was in the tradition of both Indian miniature and Japanese painting.’ In making these adjustments he was bringing the embodied practices of painting Indian miniatures and Japanese paintings together, reminding us about the commonalities between the two styles, including the similarity of the single-haired brushes that are typically used for both (among many other types of brushes used, of course). For his ceramic paintings Singh would use local squirrel tail hair for his brushes, even as he also kept a wide array of Japanese brushes. Experienced in Indian, especially Rajasthani, fresco and miniature panting techniques, Singh would also use similar methods of mixing colours using inorganic mineral and organic watercolours.

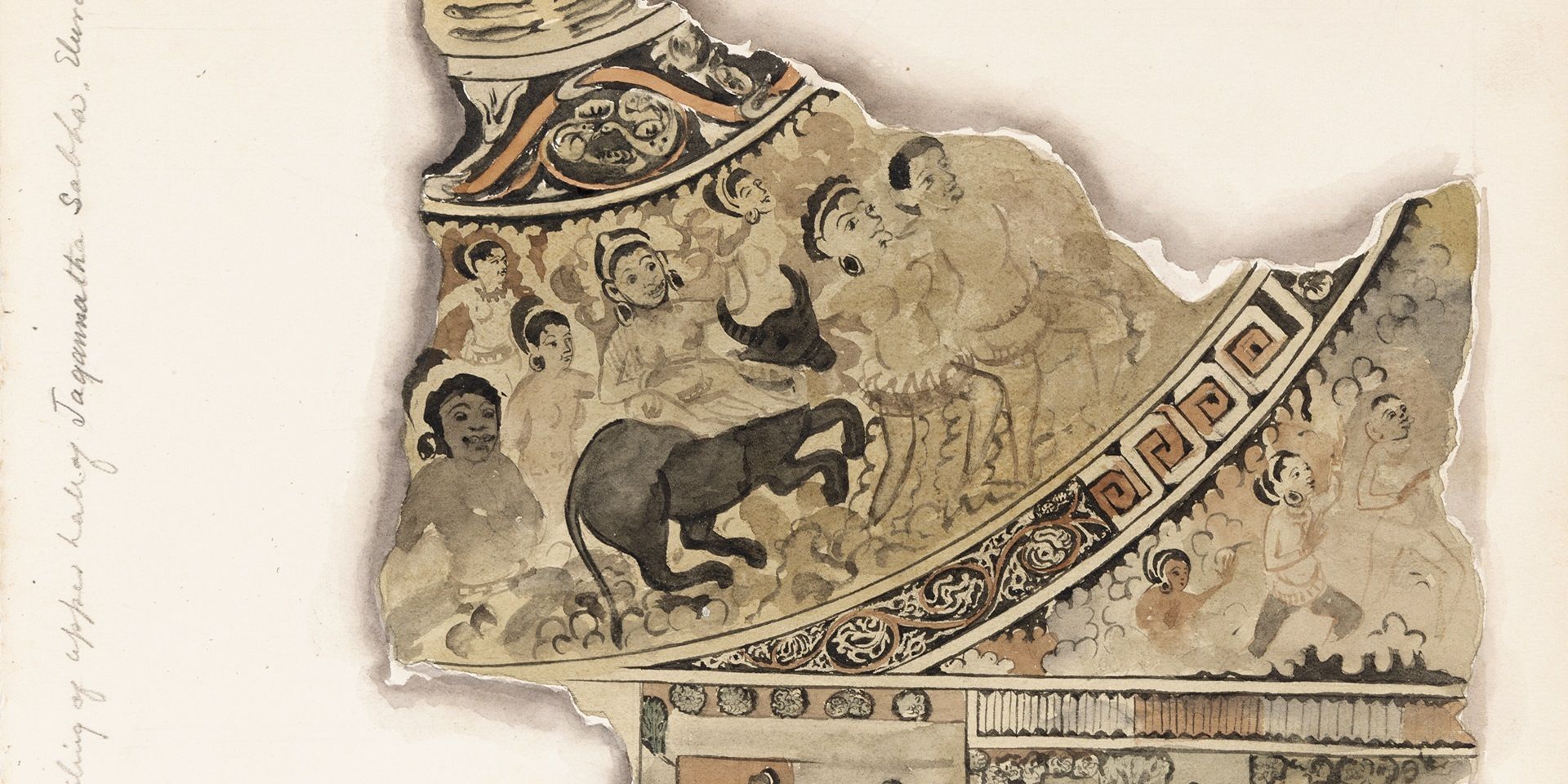

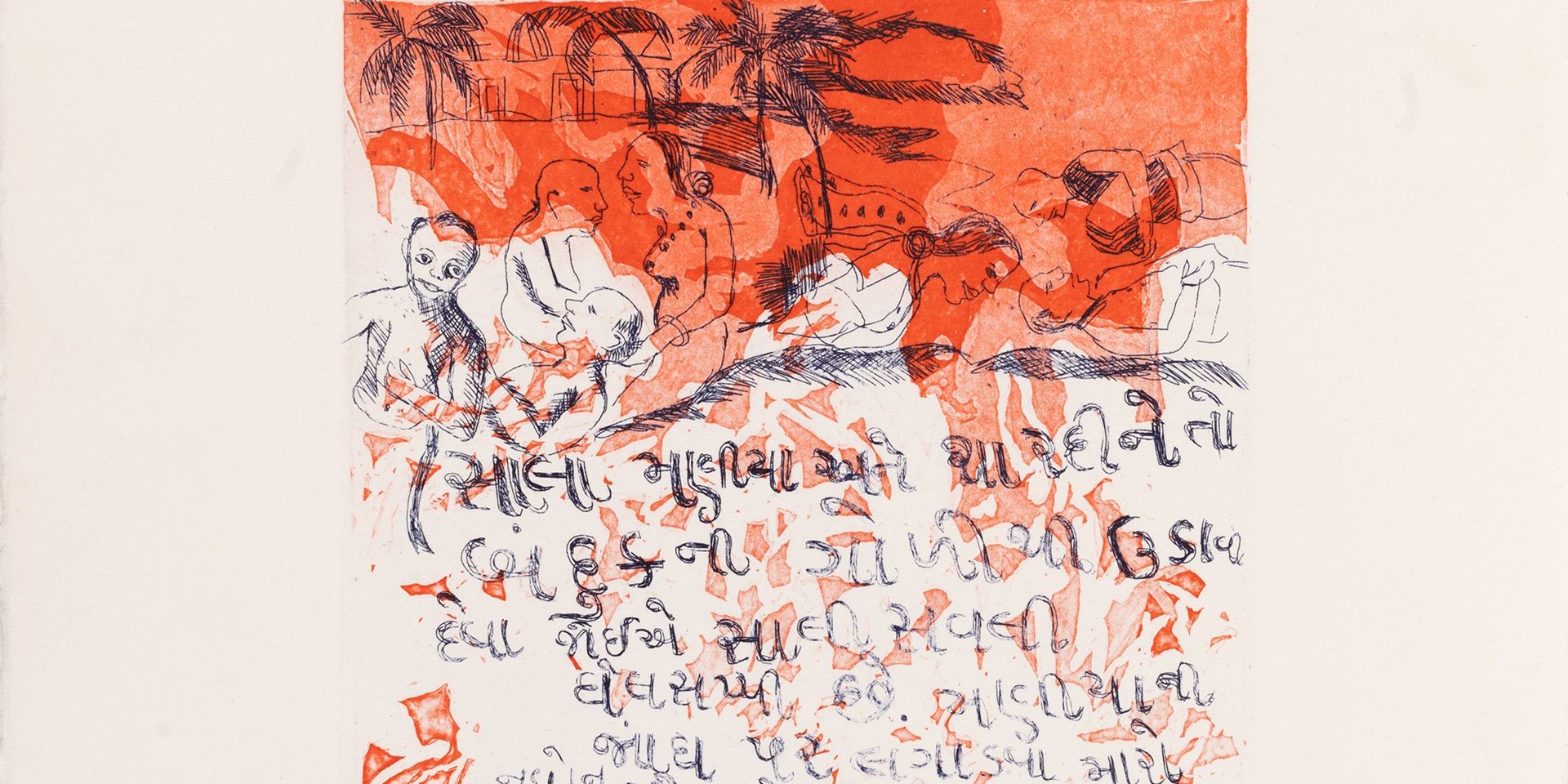

Kripal Singh Shekhawat, Untitled (detail), watercolour on paper, 12.2x338.7 in., c. 1950s. Collection: DAG

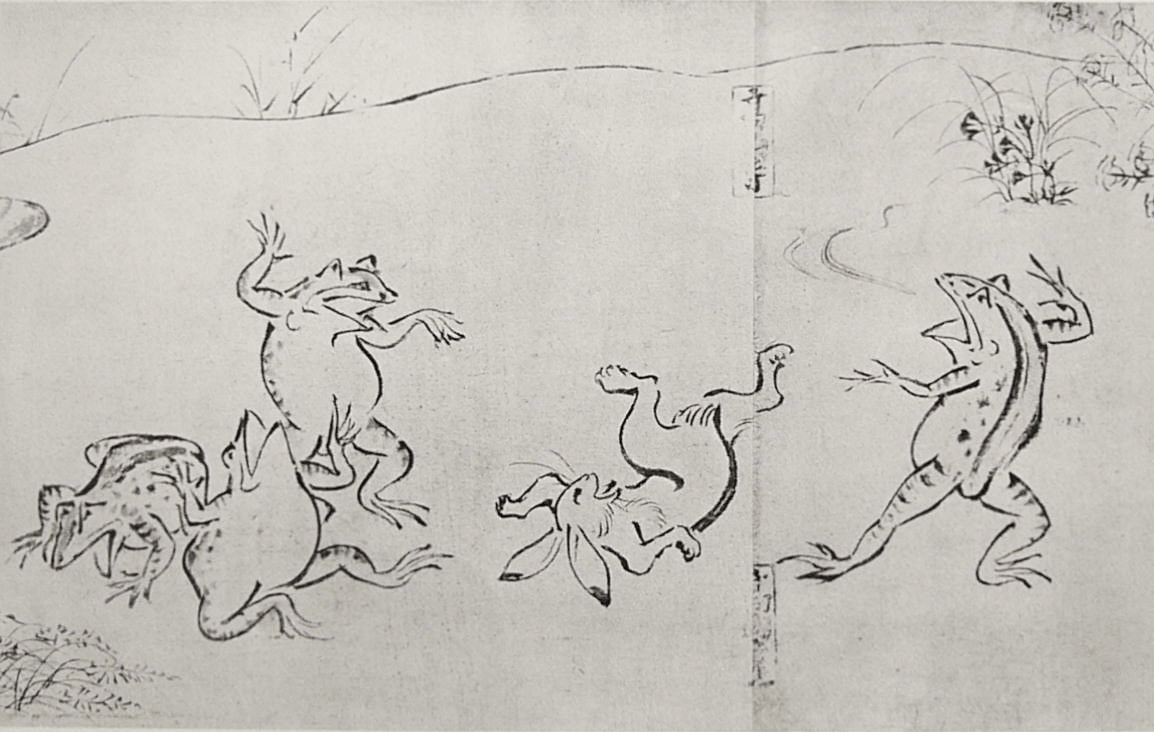

As with Indian artists, the sources of modernism in Japan extended to its storied early modern pasts as well, especially with regard to its scrollworks, which were frequently reinterpreted. ‘One of the classical formats that Kripal Singh studied,' a historian writes, 'was the late twelfth century illustrated scroll attributed to Toba Sojo Kakuyu. Kakuyu was an eminent priest of the Tendai sect of Buddhism who was also famous as a painter. This national treasure… owned by the Kozanji Temple in Kyoto is a black ink monochrome and depicts bird and animal caricatures painted in sumi ink on paper. Kakuyu used the form of satirical caricature to express the indignation he felt towards his corrupt contemporaries.’ Perhaps to strike a similar vein, the elaborate scrollwork that Singh made, featuring Japanese characters and settings, was in a light register, suggesting comic scenes and situations, played out against well-articulated Japanese architectural forms and rolling, natural landscapes. Whatever its inspiration was, it remains a unique work of art in the world, carrying as it does the material trace of a significant cultural encounter of an Indian artist with a far-eastern tradition of art.

|

Toba Sojo, Frolicking Animals, 12th Century Handscroll. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

There were other artists in Rajasthan who followed similar routes too, looking to expand the basic vocabulary of Rajasthani styles and mythological subjects by accessing the influential pan-subcontinental aesthetic style of the Bengal wash technique, which, in its turn, was shaped by the pan-Asian ideals of Abanindranath Tagore and his students, under the shadow of Rabindranath, Okakura and others. Artists like Ramgopal Vijayvargiya, who was the principal of the Rajasthan School of Art from 1958-1966, was another influential disseminator of this style in Rajasthan, encouraging synthesis with local influences as well as extra-regional ones. Together with the unique practice of Kripal Singh Shekhawat, these works point towards rich cultures of exchange and learning from the tradition of intimate Others that can become a new template to decentre the demands of a Euro-American hegemony in the arts and truly decolonise our understanding of the world and its representation(s) in art.

|

Ramgopal Vijaivargiya, Untitled, c. 1940s, Watercolour wash on paper pasted on paper, 40.0 x 27.0 in. Collection: DAG |

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

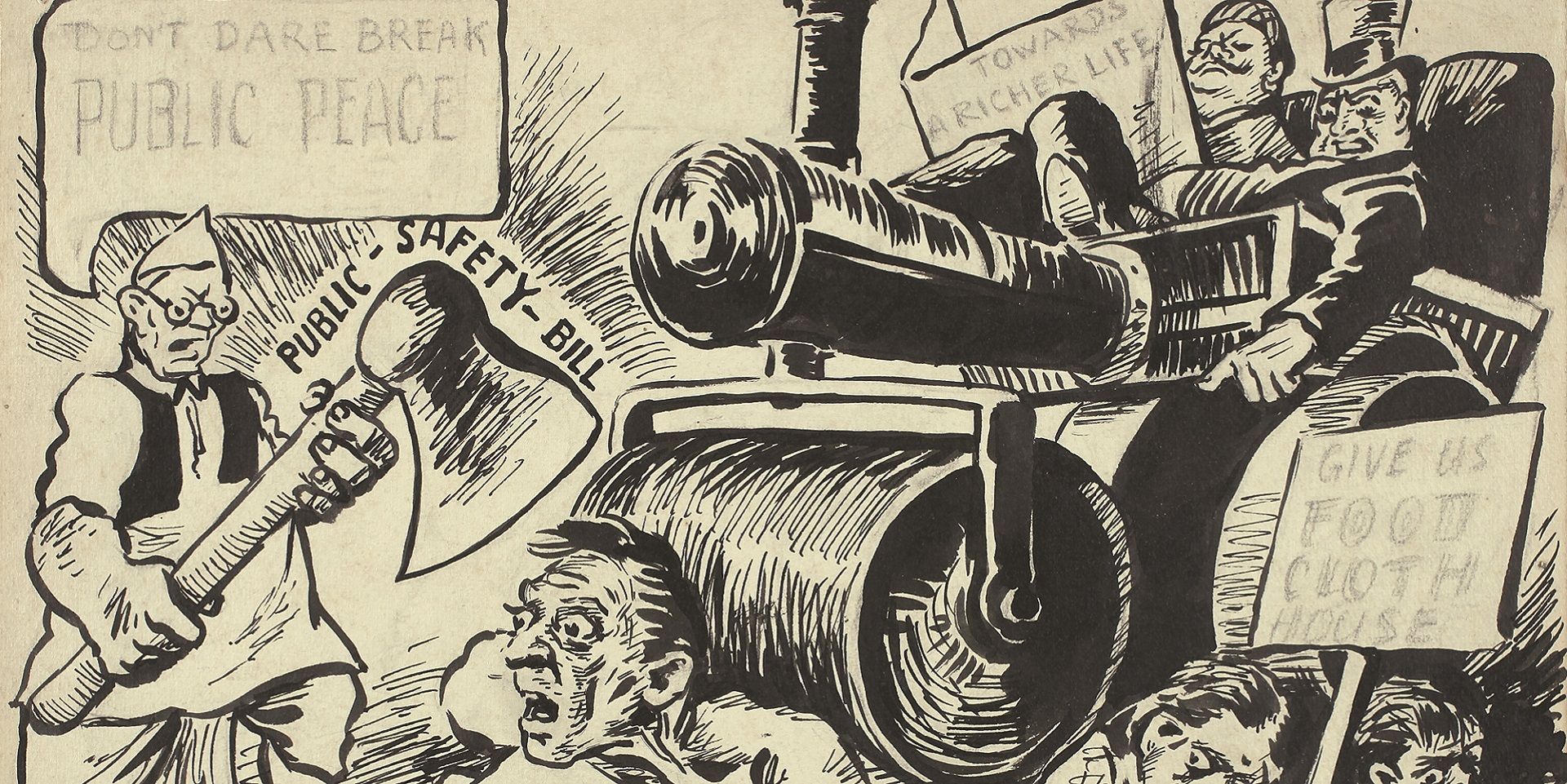

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

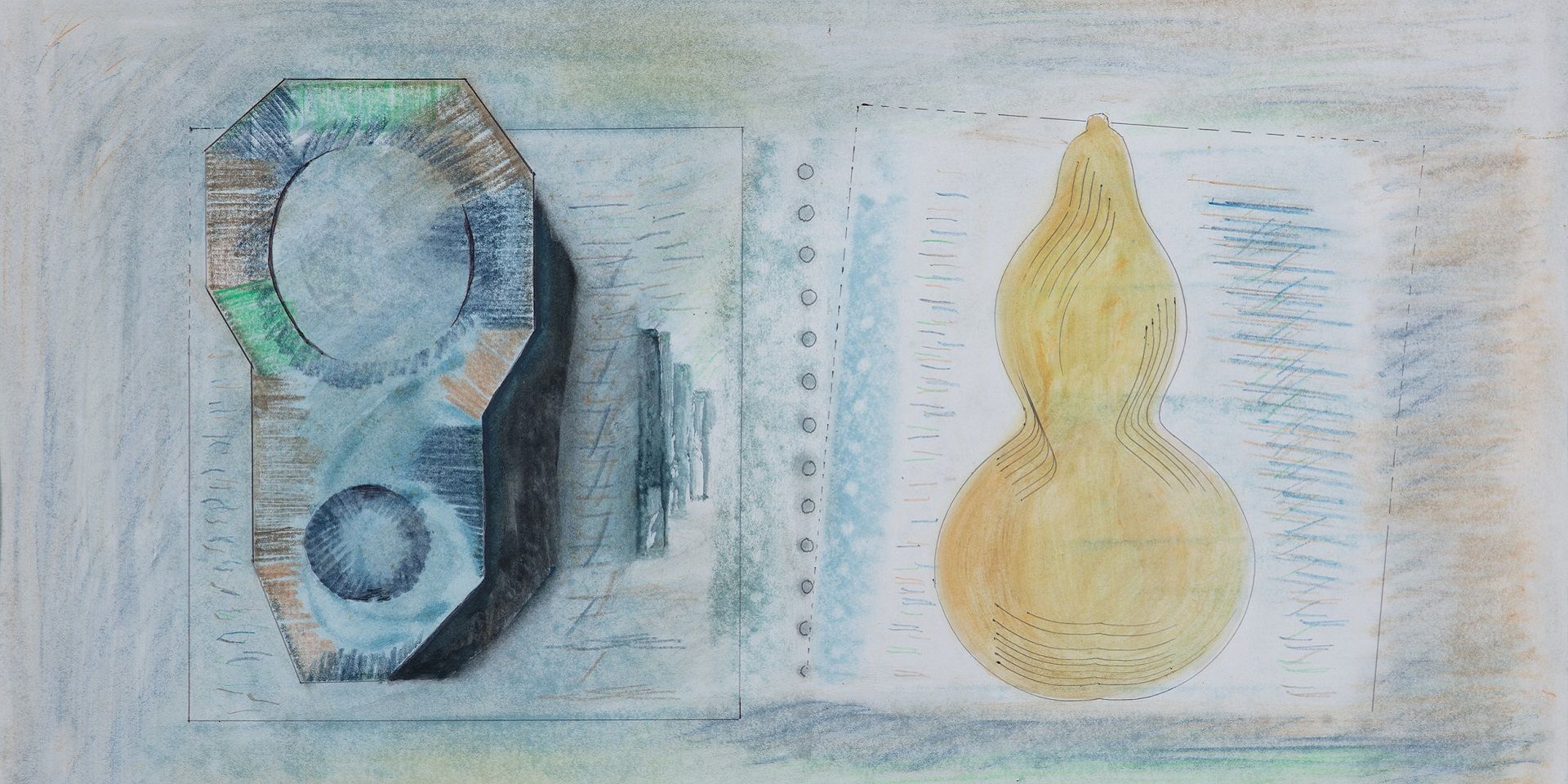

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024