Reverse-glass paintings: Variations on the Kalighat pat

Reverse-glass paintings: Variations on the Kalighat pat

Reverse-glass paintings: Variations on the Kalighat pat

Anonymous (Early Bengal), Mahisasuramardini (detail), Late 19th Century, Gouache highlighted with gold and silver pigments on glass (reverse painting), 19.0 × 13.7 in. Collection: DAG

A unique product of European and inter-Asian cultural encounters, the reverse glass painting technique represents a significant variation on iconic early modern image-making, of which the Kalighat pats form a part. How did this technique come about?

The origins of painting on the reverse side of glass are contested. Popular discourse proposes that the art form originated in Italy in the fifteenth century, and was then exported to China, especially the region of the port city Canton (present-day Guangzhou), which became a trade port of imminence through the Opium Wars (1839–60). However, contrarian schools of thoughts suggest that reverse-glass art developed independently across different urban centres in Asia and Europe, with certain ideas placing its origin as far in the distant past as the Roman Empire.

Unidentified Artist, Untitled (European Factories at Canton), Gouache on glass (reverse painting), 19th century, 9.0 × 13.5 in. / 22.9 × 34.3 cm. Collection: DAG

Throughout the eighteenth century, Canton served as the sole primary point of contact between China and the foreign world. Consequently, it became a hub for various industries, including those specialising in the art of reverse-glass painting. This technique involved painting on the back side of glass—both mirrored and non-mirrored—which was initially imported from Europe, with the finished product then reexported out from Canton. The art form’s popularity reached the highest echelons of power, as evidenced by Emperor Qianlong (reign 1736–96), the fifth emperor of the Qing dynasty. He established a workshop for reverse-glass painting within his palace and employed a French Jesuit artist, Father Jean-Denis Attiret. Father Attiret was not only a skilled artist but also the author of a widely acclaimed 1752 publication about the Yuanmingyuan gardens.

Unidentified Artist, Untitled (Court Scene), Gouache on glass (reverse-painting), c. 1890, 14.0 × 19.7 in. / 35.6 × 50.0 cm. Collection: DAG

Reverse glass painting emerged in India during the time of Tipu Sultan (1751–99) and was prevalent in the princely states of Satara and Kutch. An early family portrait of Shuja-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Oudh (reign 1754–75), stands as a remarkable example of early Cantonese-origin reverse-glass painting depicting an Indian subject, inspired by an engraving from the British artist Tilly Kettle (1735–86). As this art form was primarily export-oriented, Cantonese artists employed imagery that resonated with the target demographic, meticulously recreating these on glass using a vibrant palette dominated by reds and blues. Initially evident along India’s western coastline, likely introduced in the region by Chinese and Parsi traders, it spread to burgeoning cosmopolitan centres such as Calcutta in the nineteenth century, where the city’s wealth attracted new forms of trade. Therefore, it is not surprising that reverse-glass art targeted for the Indian subcontinent showcased a variety of subjects: from landscapes, reproductions of miniature art, Islamic calligraphy to Zoroastrian themes.

Anonymous (19th Century), Ganga, c. late 19th century, 18.2 x 14.5 in. / 46.2 x 36.8 cm. Collection: DAG

In selecting images that would appeal to the markets of Calcutta, Kalighat pat watercolour paintings served as a template, likely due to their straightforward iconography that showed only characters and were devoid of background elements. It is likely these works may have been created by Chinese artists living in India, or were made in Cantonese workshops that copied the designs from Kalighat paintings. By the nineteenth century, a direct trade route existed between Calcutta and the Chinese port and therefore it is not implausible to imagine some pat paintings making their way to the Chinese city on China-bound vessels. There is also a hypothesis that Indian artists might have adopted the reverse-glass painting technique from their Chinese counterparts. However, the presence of flawed iconography in the images suggests that it is improbable for Indian artists to have introduced such inaccuracies, thereby weakening this argument. The identity of the artists behind these images remains a mystery, yet their work represents a remarkable fusion of two distinctly different cultural traditions.

|

Anonymous (Early Bengal), Mahisasuramardini , Late 19th Century, Gouache highlighted with gold and silver pigments on glass (reverse painting), 19.0 × 13.7 in. Collection: DAG |

The DAG collection’s reverse-glass paintings, particularly those featured in The Babu & the Bazaar: Art from 19th and 20th-Century Bengal, display elements from both the western and eastern coasts of the Indian subcontinent. While the subjects are clearly borrowed from pat watercolours—notice the typical cross-beaded jewellery on the forearms and legs that have been adapted as tattooed designs—the clothing on some figures appear closer to how people dressed along the western coast of India, if not outright Maharashtrian. The figures are placed within a standardised landscape with a mountain framing the backdrop. Even as it locates itself in a generic, imaginary landscape, the reverse glass works have a lot to say about the nature of global aesthetic influences and trade networks, especially at the height of colonialism, that made the circulation of such works possible.

|

Anonymous (Early Bengal), Scene from Ramayana, c. late 19th century, Gouache, highlighted with gold pigment on glass (reverse painting), 20.0 x 14.0 in. / 50.8 x 35.6 cm. Collection: DAG |

related articles

Essays on Art

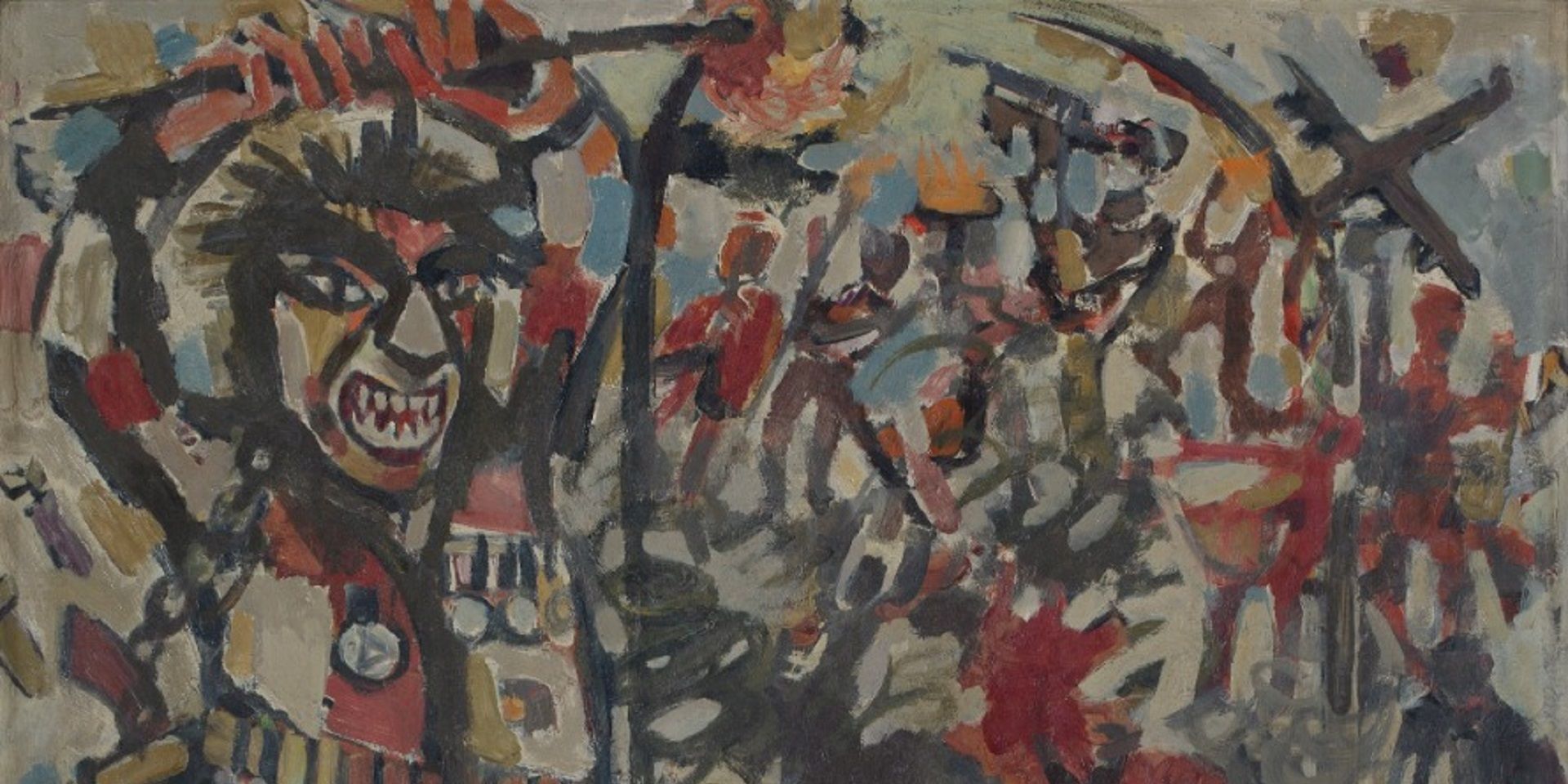

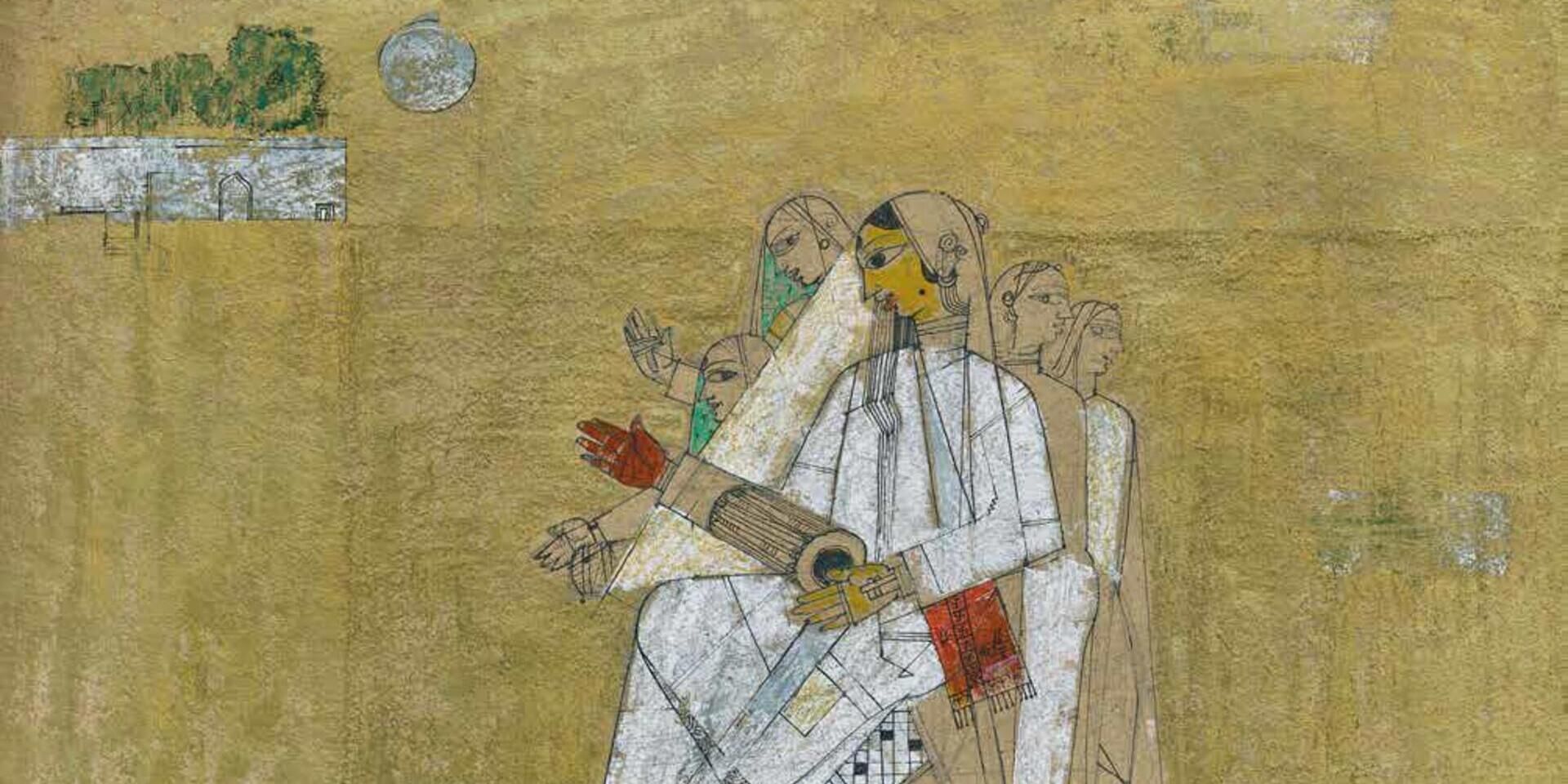

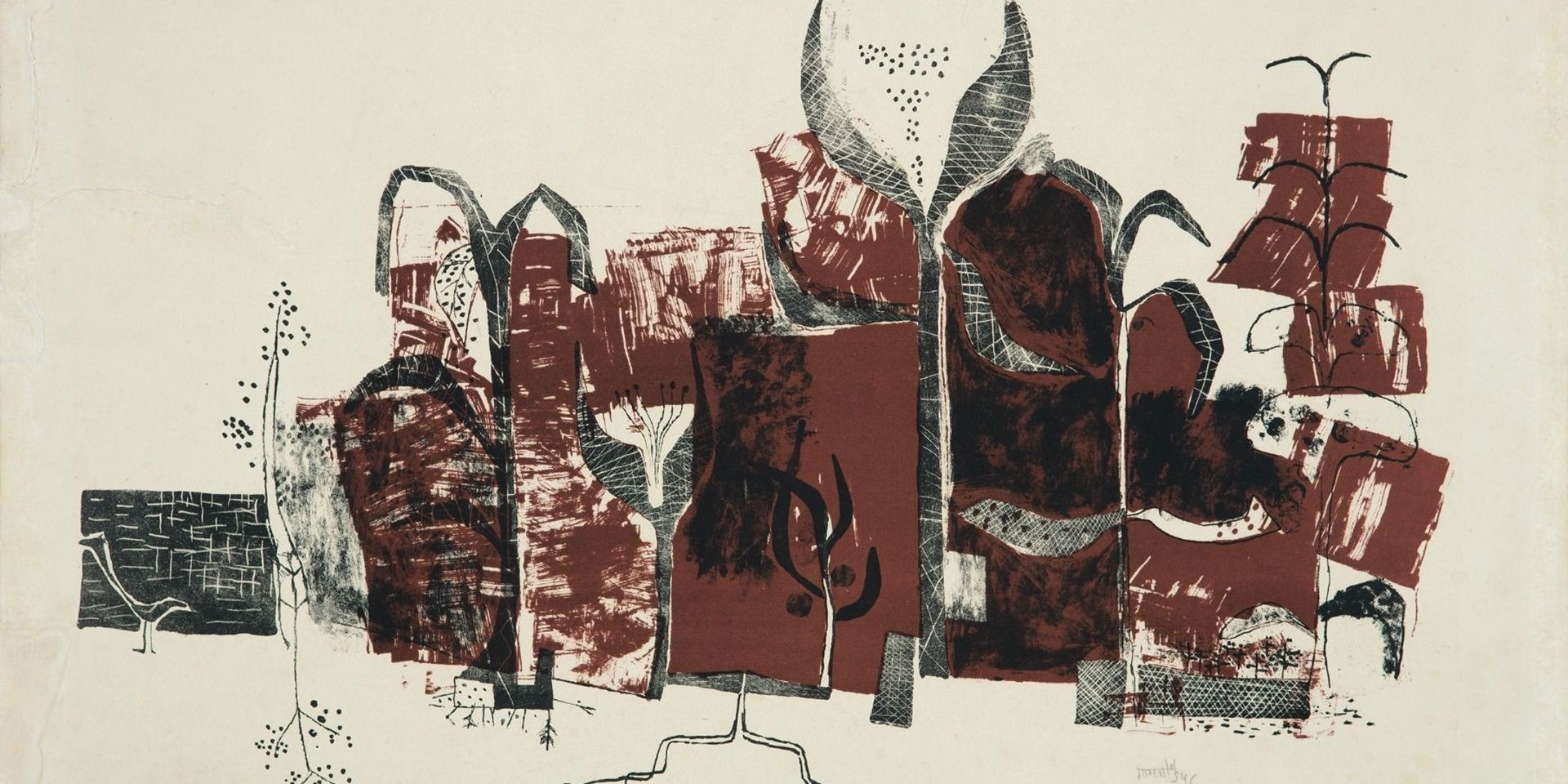

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

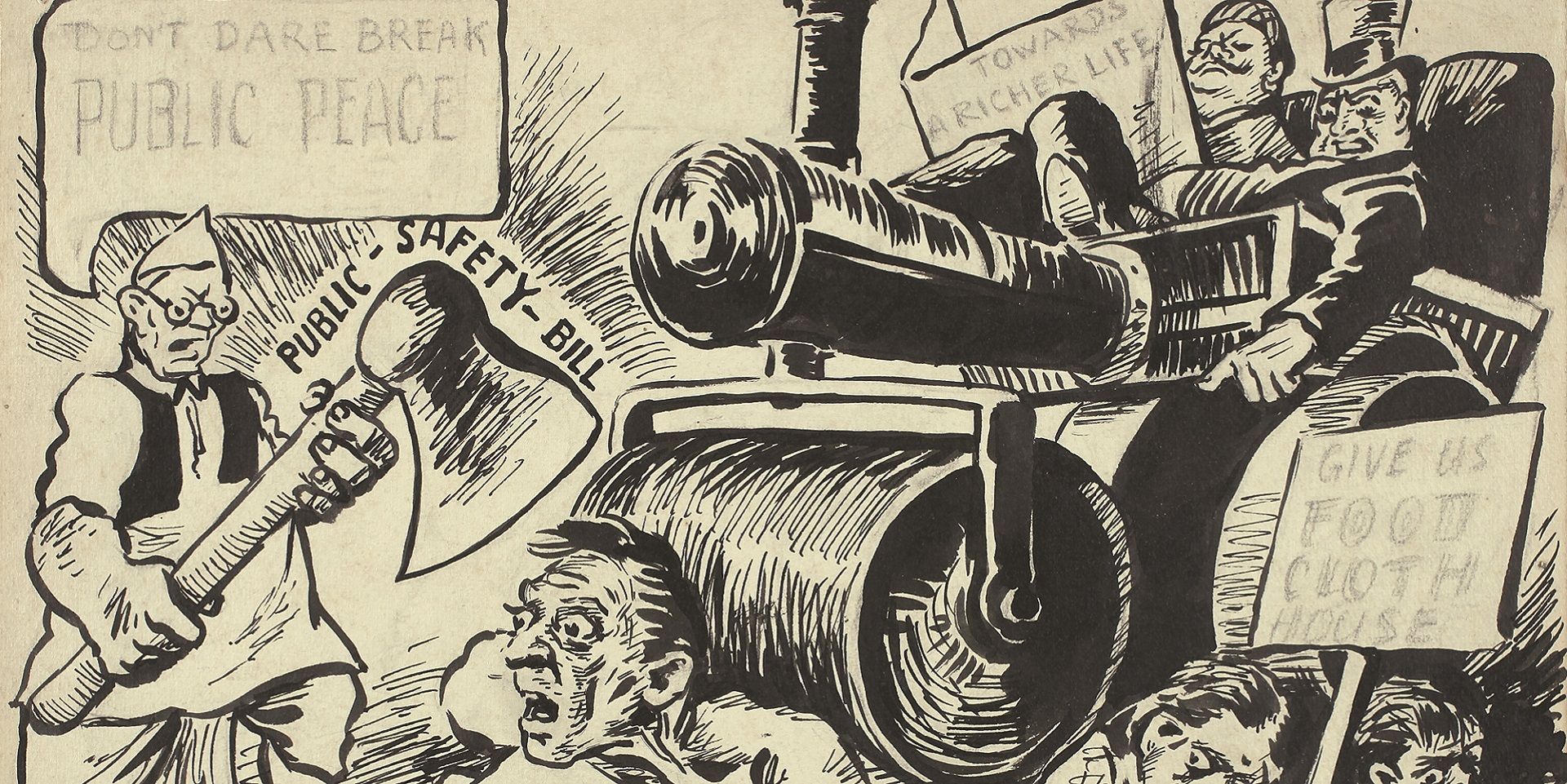

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

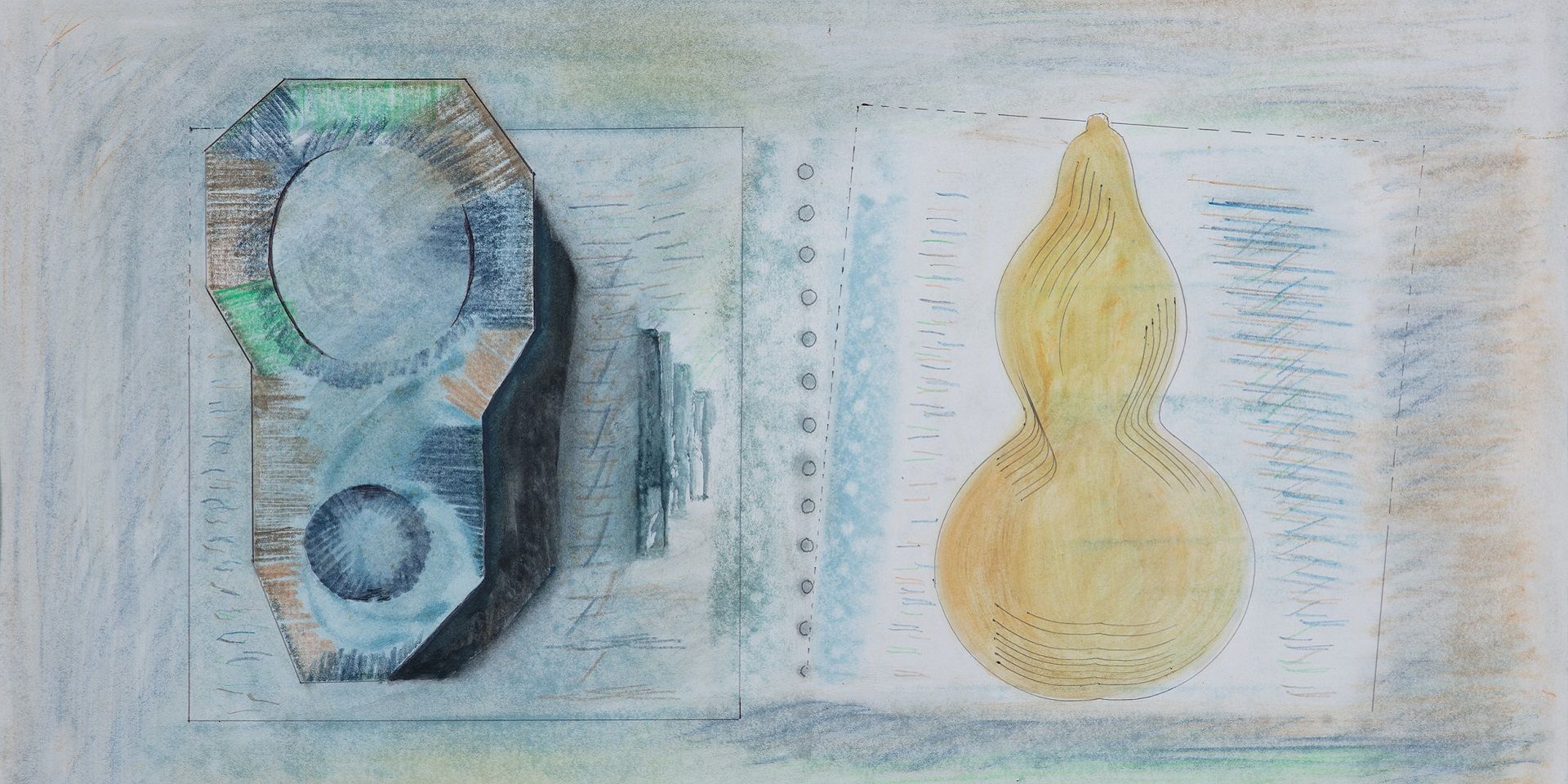

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

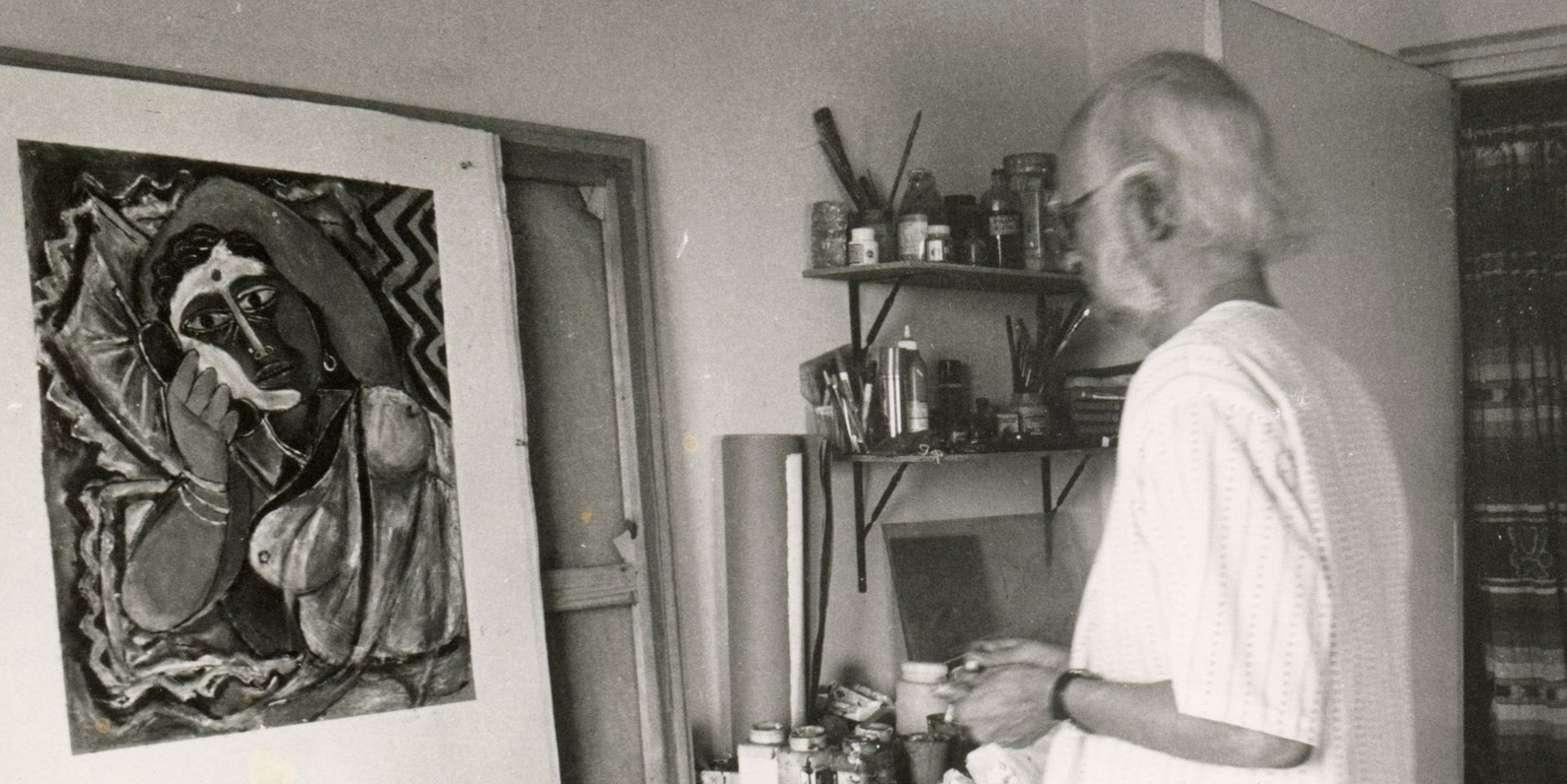

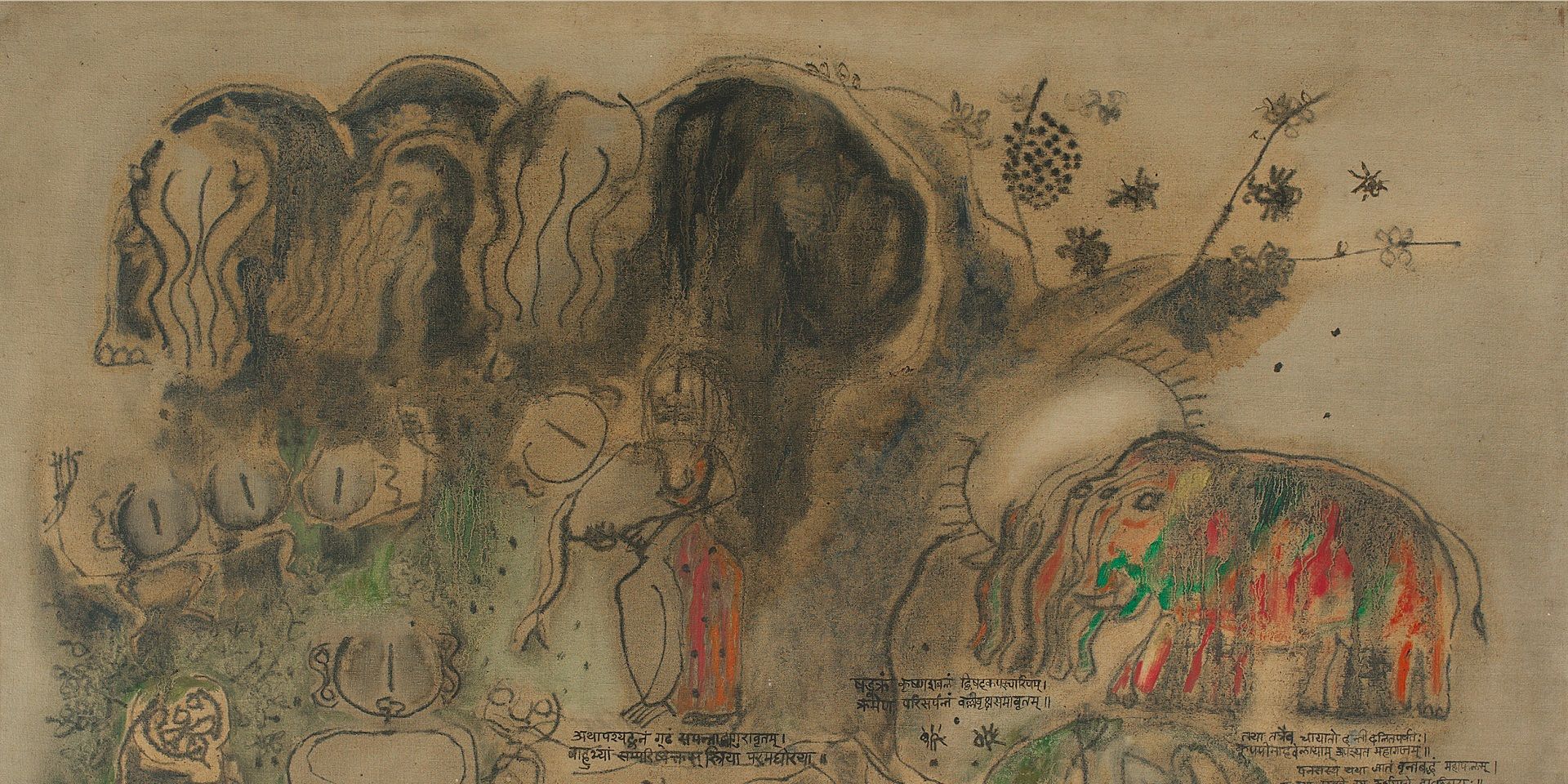

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

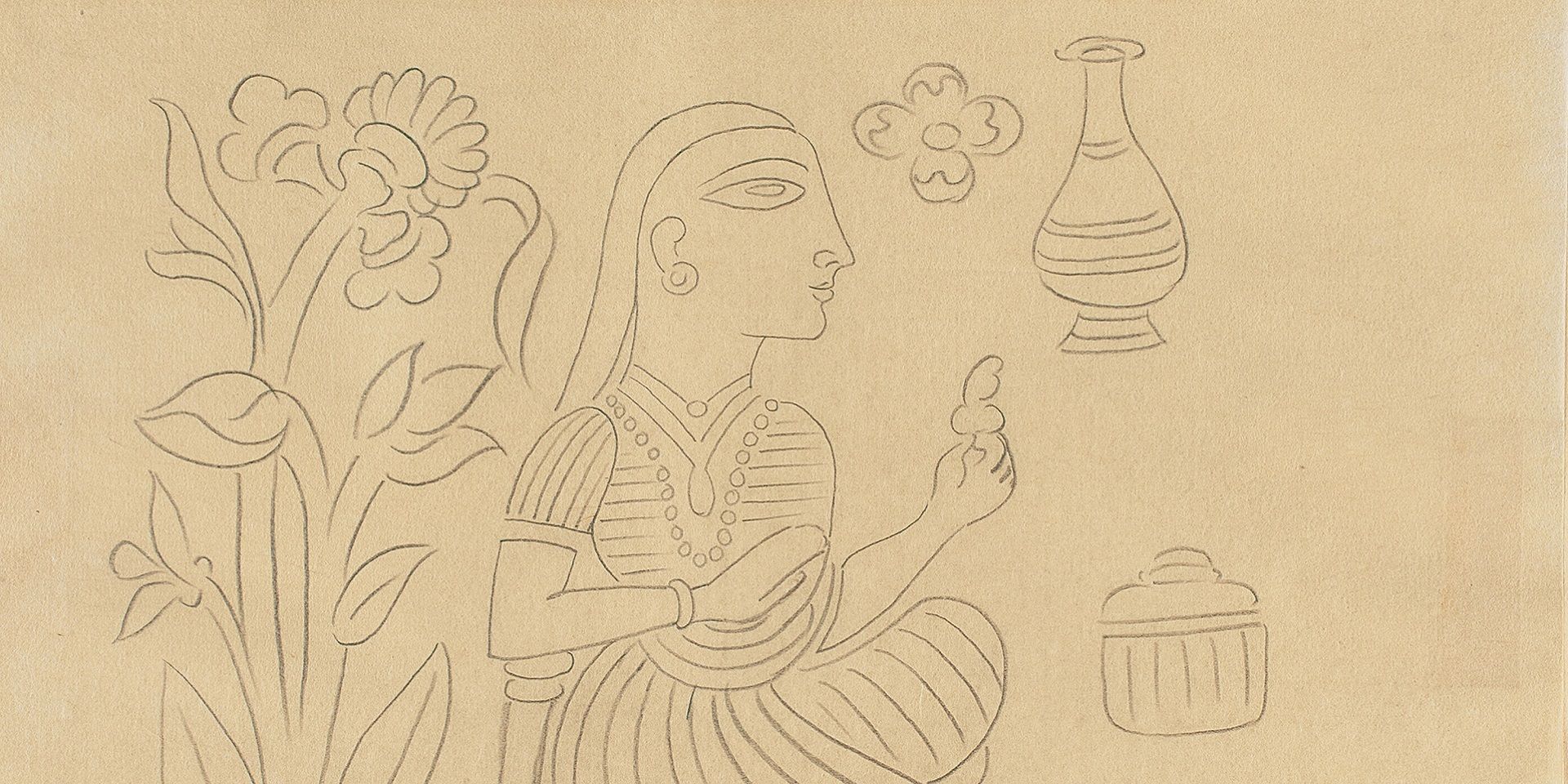

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

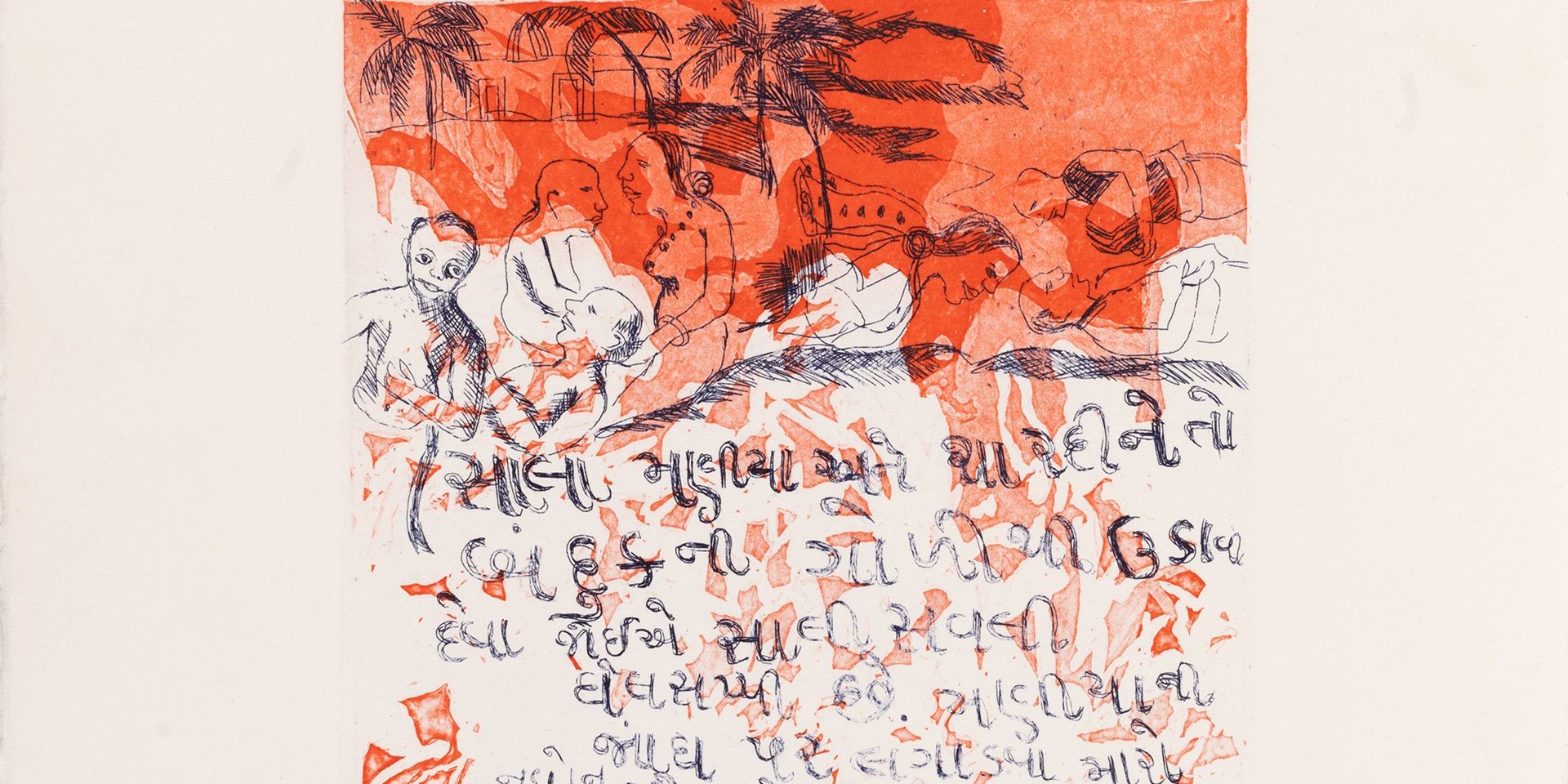

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

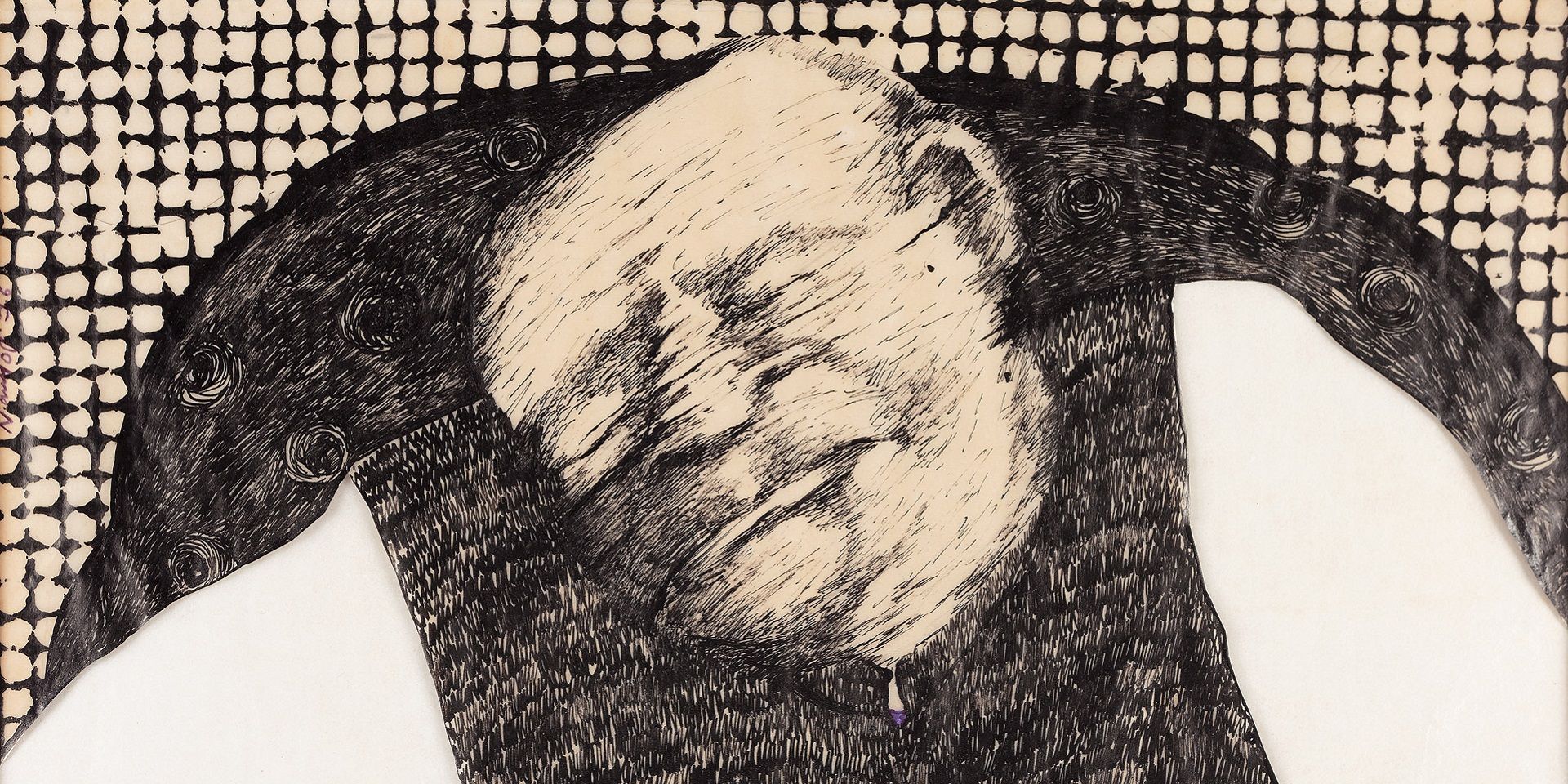

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024