To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

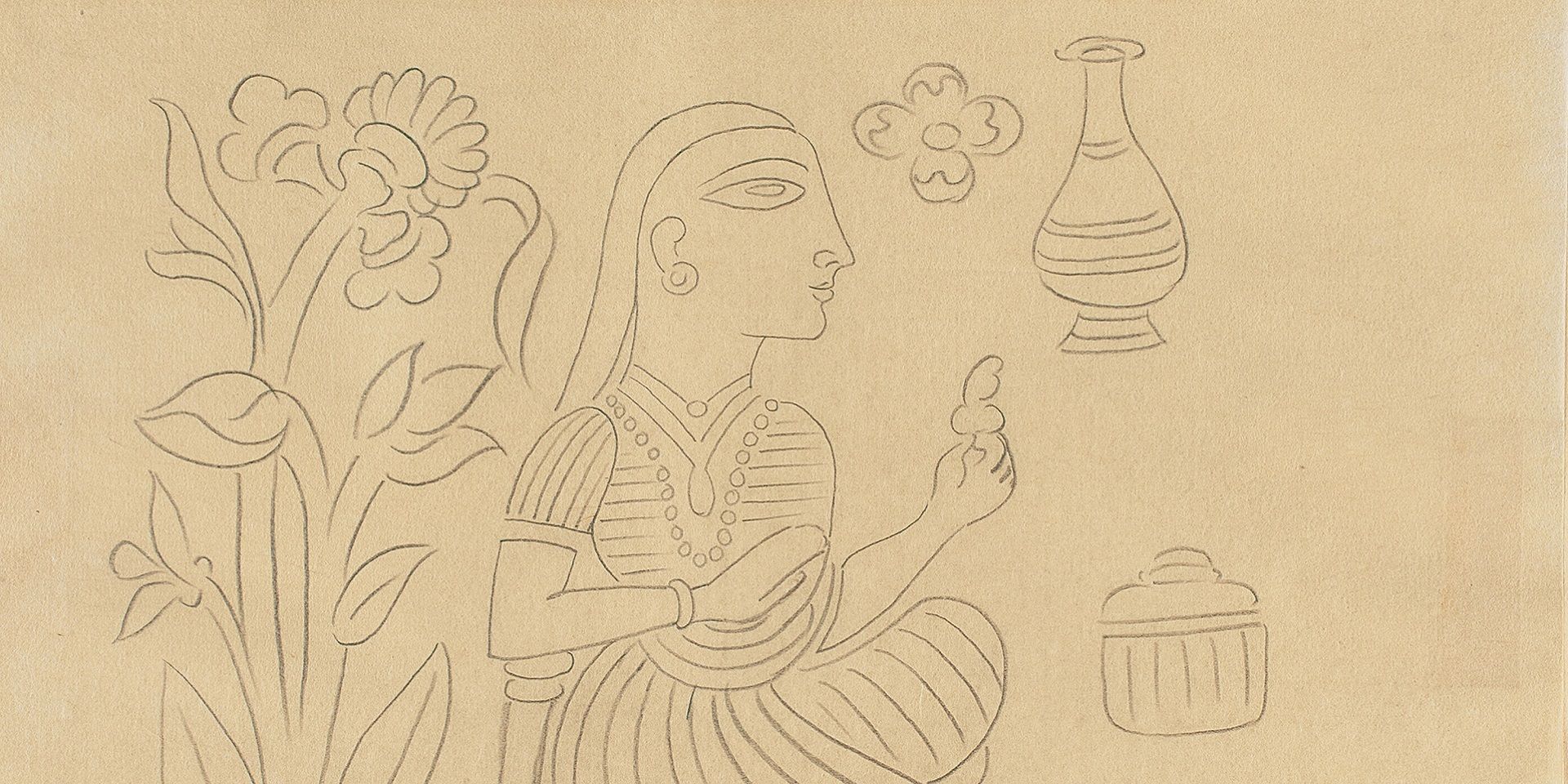

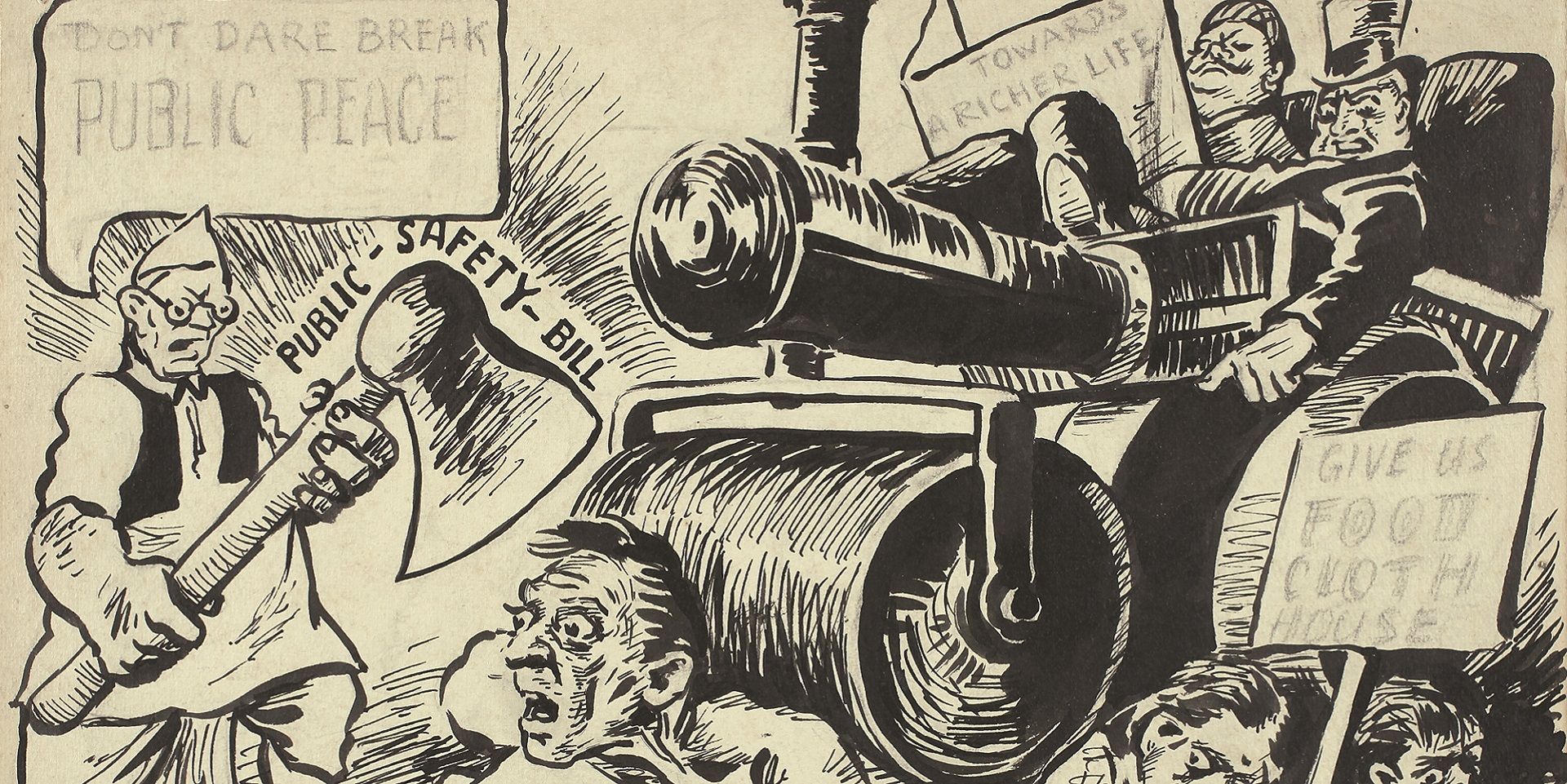

Chittaprosad, Untitled, Graphite, brush and ink on paper, 1947, 8.5 x 11.0 in./ 21.6 x 27.9 cm. Collection: DAG

Some of the great Indian caricaturists plied their trade against the world of colonial rule in the early twentieth century. How did they see their roles change after the nation gained its independence in 1947? Sayandeb Chowdhury explores the question through a close reading of three well-known caricature artists from Bengal: Chittaprosad, Prafulla Chandra Lahiri (or 'Piciel') and Pramatha Samaddar.

Political caricature aimed its ammunition at the modern state even before the modern state had emerged into adulthood. Similarly, about colonialism, nineteenth century print culture in Britain and elsewhere saw caricaturists satirising projects of that nature, which was otherwise peddled to the public as a cross between laissez-faire entrepreneurship and virtuous civilizational philanthropy. Self-love and self-delusion are often two faces of the same coin, and nineteenth century print humour showed the latter to the former, like an inverted mirror. In fact, if anything that was gestured again and again by caricature was that nothing was to be considered sacred anymore. Punch, Fun, Judy and Moonshine in Britain, Le Charivari in France and Kladderadatsch, Die Fliegende Blätter, and Simplicissimus in Germany consistently poked at the balloon of righteous colonial delusionism. Scholars have referred to, for example Punch’s iconic 1892 cartoon ‘The Rhodes Colossus’ by Linley Sambourne, where a giant Cecil Rhodes, arms and legs outstretched, is stomping on a map of Africa, indicating the pure desire for absolute conquest. There is also, for example, William H. Walker’s 1899 Life magazine caricature ‘The White (?) Man’s Burden,’ which, says Matthew Kaiser, ‘flips Rudyard Kipling’s poetic script, depicting the weight of Western imperialism as crushing the bodies of conquered peoples, who march across an inhospitable landscape and into an uncertain future doubled over in pain and despair…’ These are two representative illustrations from a pool of numerous others, in which print humour crossed arms undaunted with the notion of the righteous nation and the civilizational state.

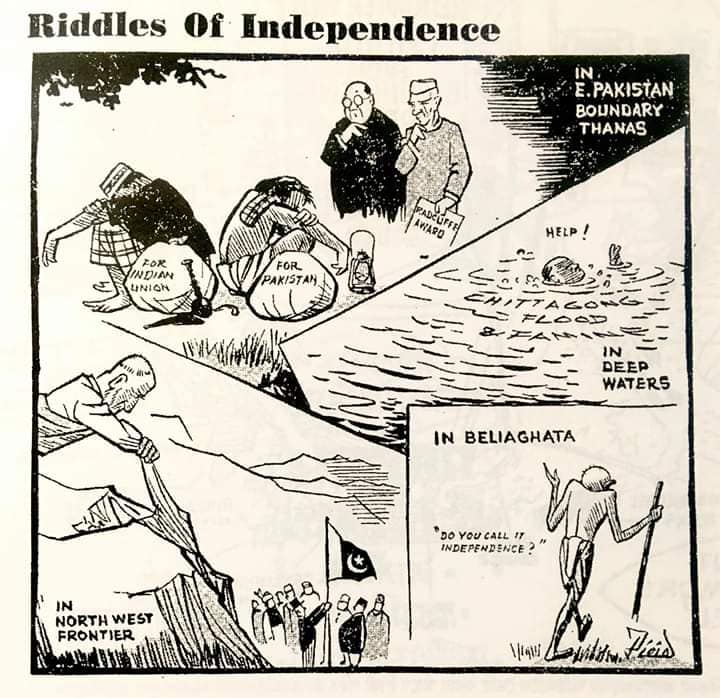

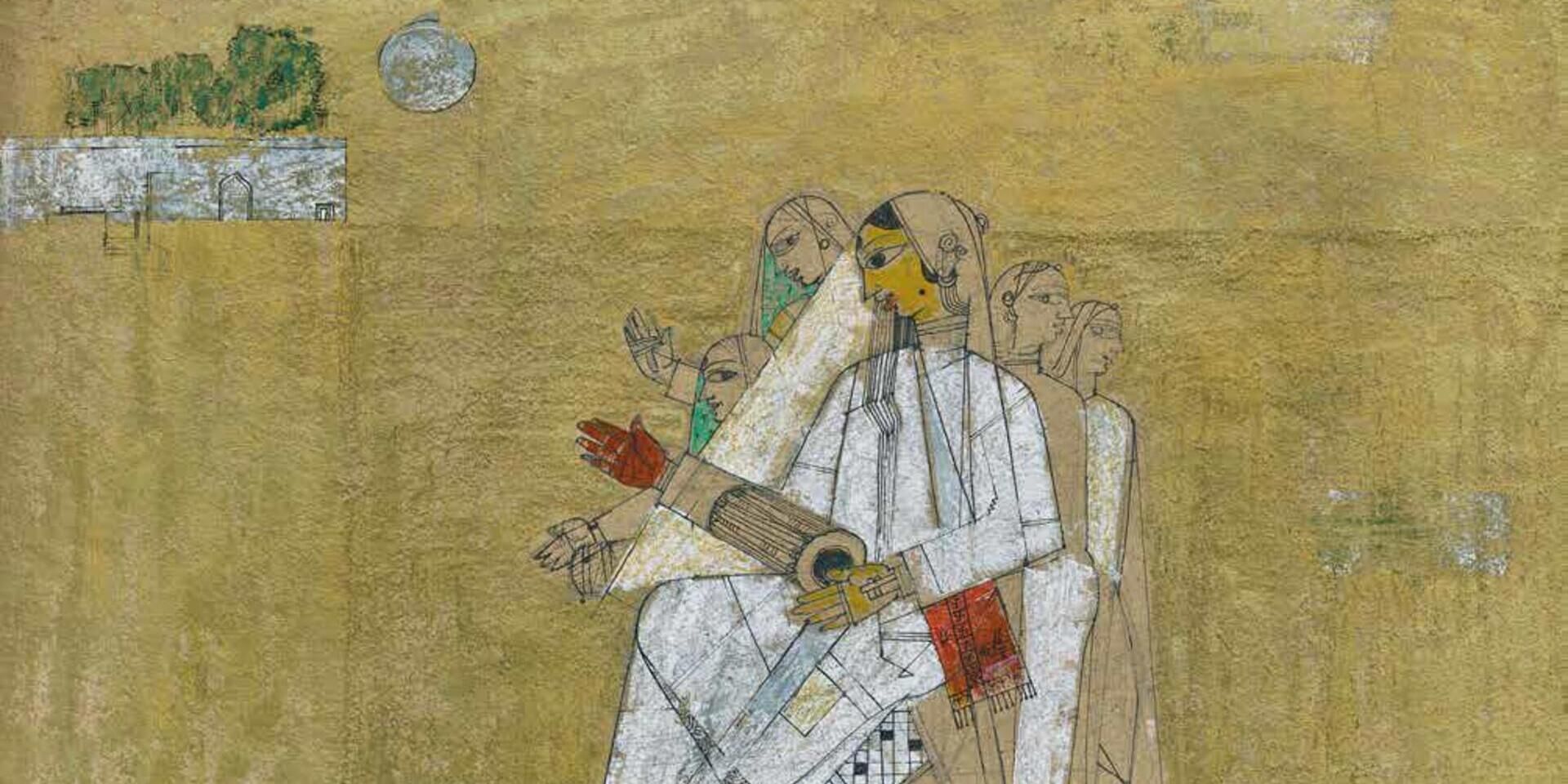

Piciel (Prafulla Chandra Lahiri), ‘Riddles of Independence. Image courtesy: https://humourinbengal.info/

Something similar happened in the Indian subcontinent. There is a long history of caricature in early print culture in India (1850s), which soon made decisive inroads into the vernacular public space. By the 1870s, born out of a thick public discourse about negotiating the Colonia, Bengali print humour had become an increasingly sophisticated space for lampooning both the colonial administrator as well as the native acolytes, including the usual stock of characters. As art historian Partha Mitter writes, ‘The stock characters—hypocritical zamindar, henpecked husband, pompous academic, obsequious clerk, illiterate Brahmin were the cartoonists’ favourites. Characteristic behaviour and typical cultural situations, such as the plump head clerk returning from the bazaar with his favourite fish or the thin schoolteacher with stick-like arms and legs were well-captured in drawing after drawing’. Among caricaturists who mocked the colonialists as well as those who had self-fashioned to that effect, Gaganendranath Tagore and Chanchal Kumar Bandopadhyay were foremost examples.

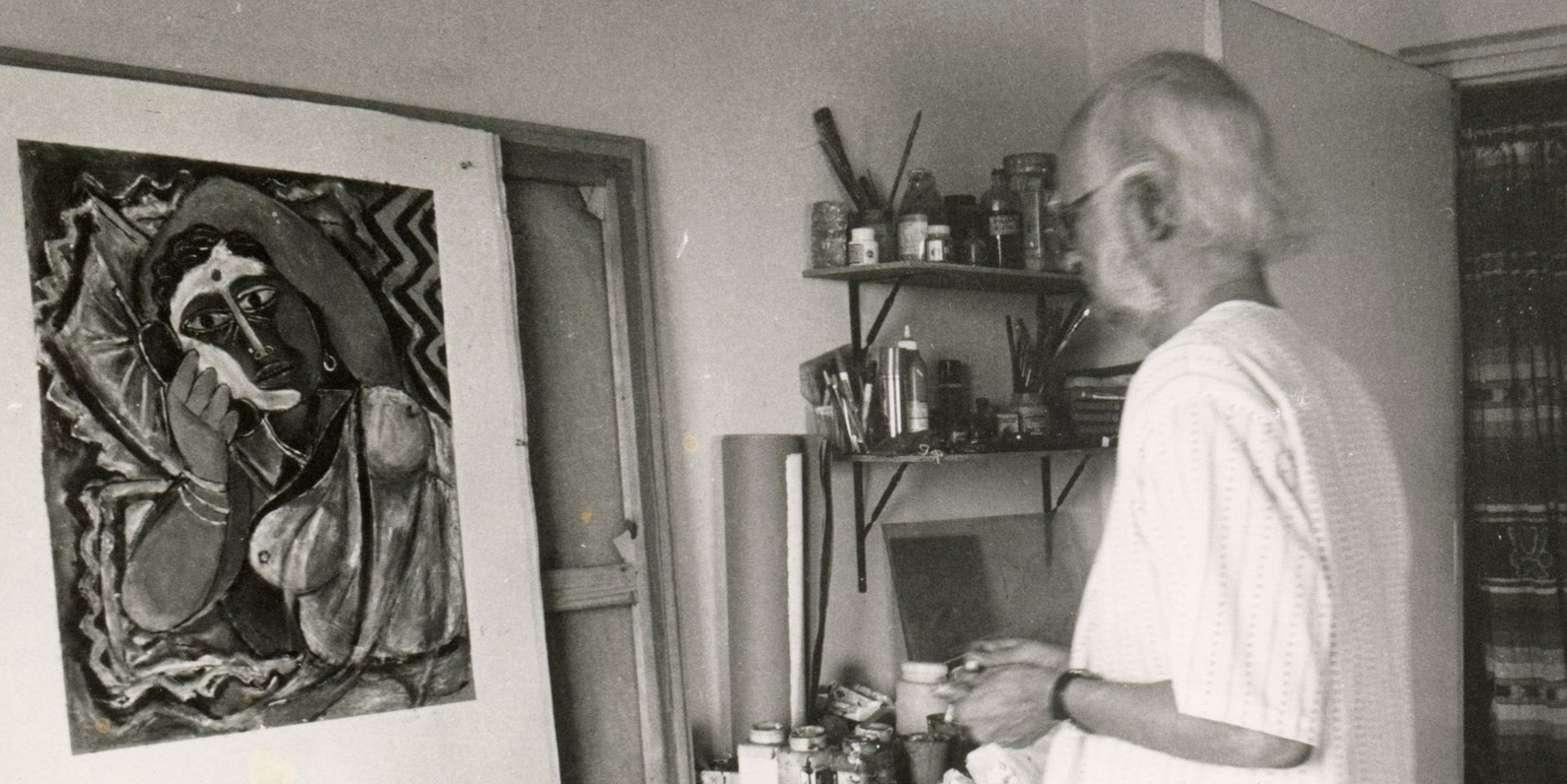

Caricature realigned its role as a tool of critique in what is broadly called the period of post-colony. That is, if we take sweeping satire as intrinsic to caricature, we must take note of how with political freedom came the liberty to take the new nation and its institutions to task as well. And three practitioners in Bengal who did it with habitual nous were P. C. Lahiri, Pramatha Samadder and Chittaprosad Bhattacharya. We shall look at three intrepid works from the early years of free India, by these key practitioners of the form. This is to understand what caricature meant for a new nation and if this encounter provokes any deeper reflection about the artist in a ‘free’ nation.

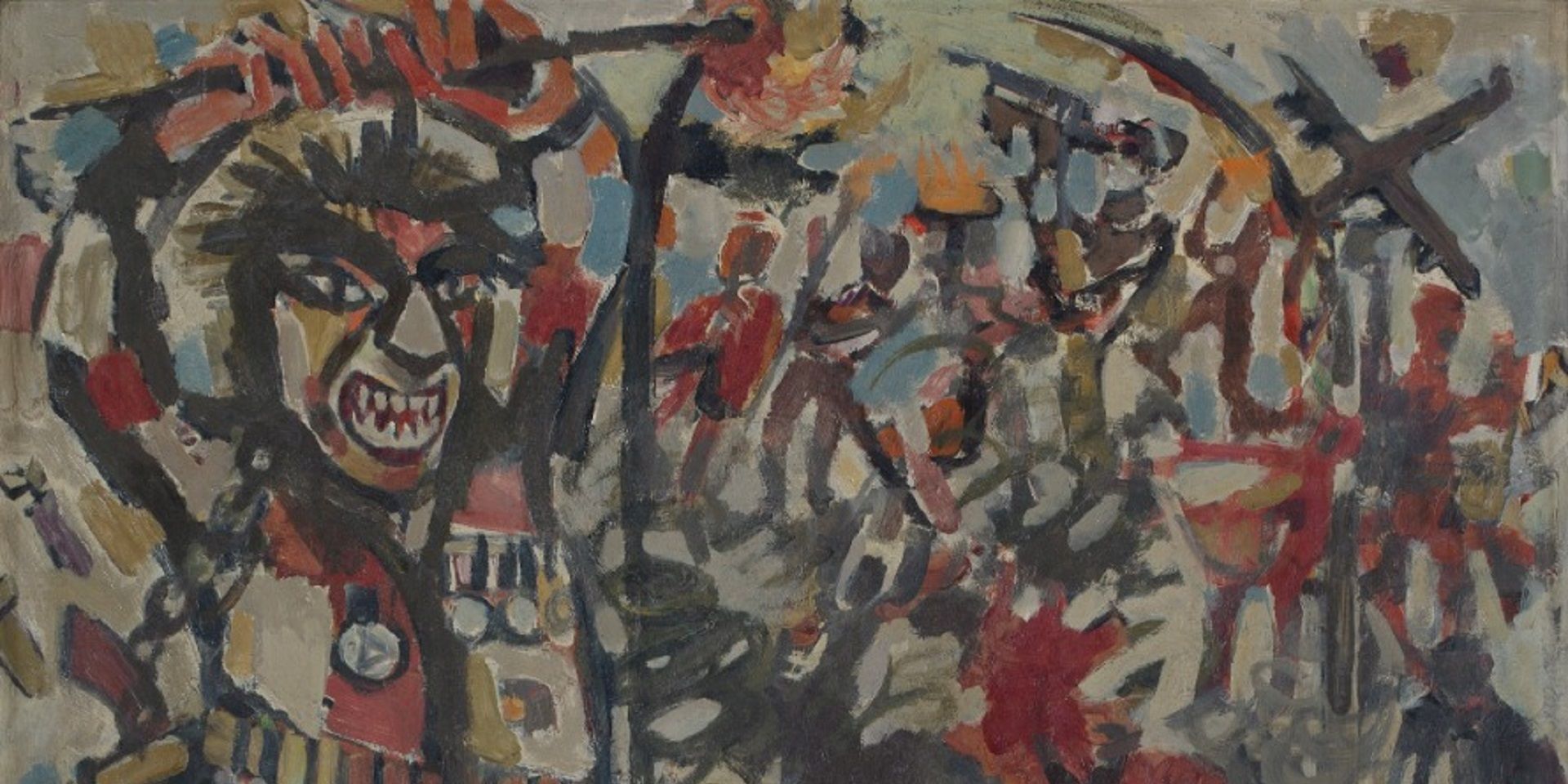

Born in 1900, P. C. (Prafulla Chandra) Lahiri drew as both Piciel (for English cartoons) and Kafi Khan (for Bengali ones) and took no prisoners when it came to satirising the political class, for his targets included Churchill, Hitler, Roosevelt and other global players of the turbulent ‘40s and ’50s. In ‘Riddles of Independence’, Piciel partitions a single frame into disparate scenarios that montage-like symbolise the moment of independence. On top left, Nehru is pondering on the fate of two miserable, ‘divided’ men; ‘Frontier Gandhi’ Abdul Gafar Khan sits forlorn atop a mountain, watching Pakistan come into shape (left bottom); Chittagong faces famine and flood (top right); and Gandhi walks away, exasperated about the true nature and meaning of independence. The sharpest point of the satire is the ‘Radcliffe Award’ that Nehru is holding in his hands, purportedly for having ‘implemented’ the slicing of India as per the ‘Radcliffe line’, the random surgery that was named after Cyril Radcliffe, the joint commissioner of the Boundary Commission.

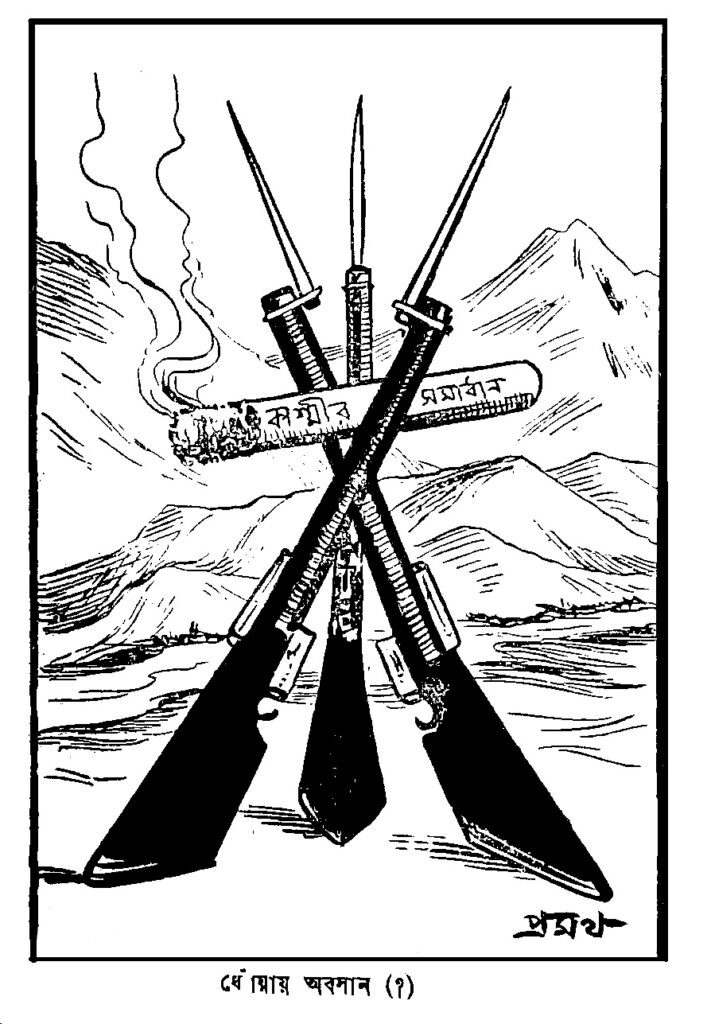

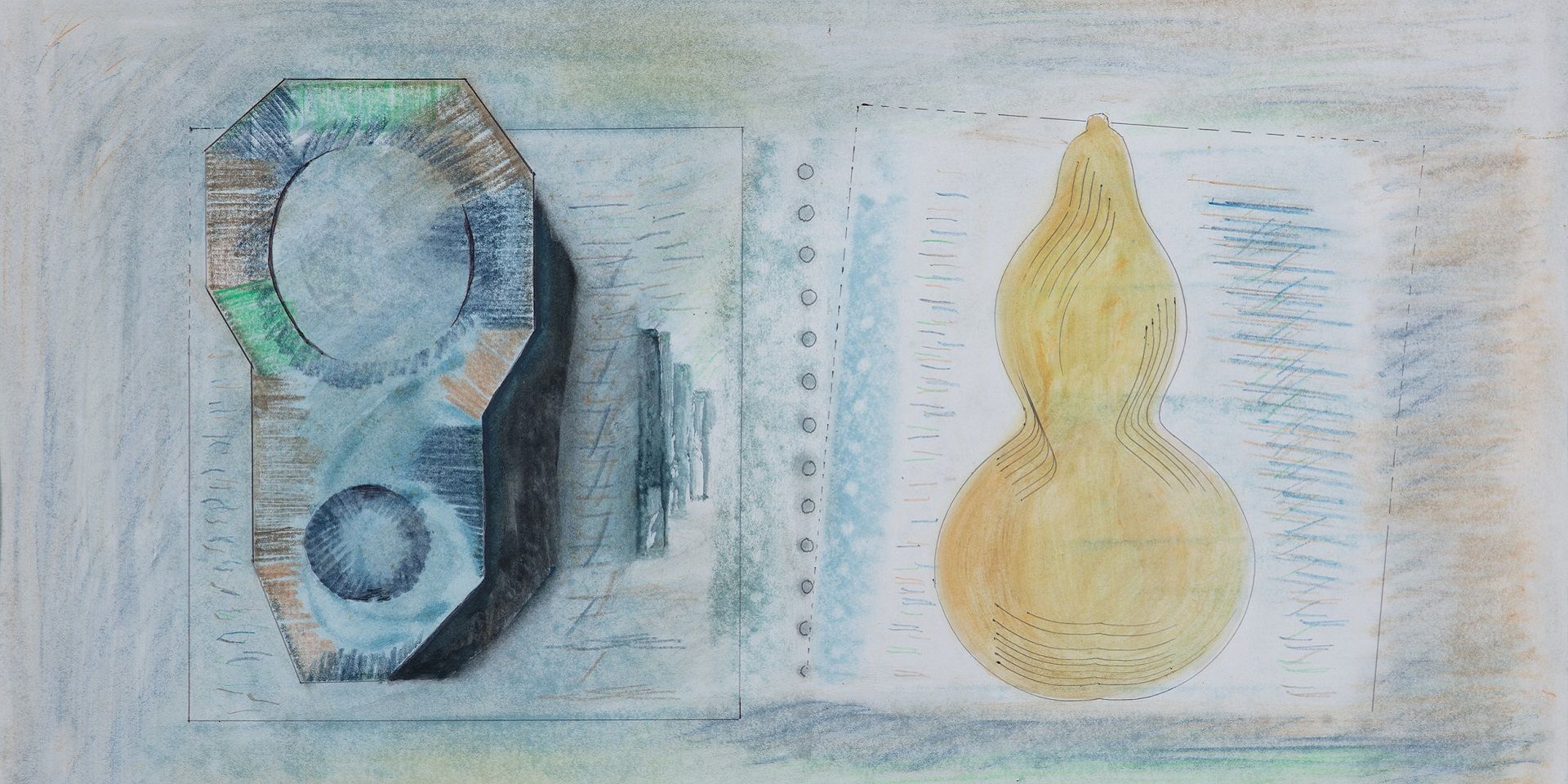

Pramatha Samaddar, ‘A Smoky Solution?’ Image courtesy: https://humourinbengal.info/

Two years younger than Piciel, Pramatha Samaddar draws upon the contentious issue of Kashmir, showing it as a paper folder in slow burn as it hangs ominously between the barrels of three assault rifles. For much of the late 40s and early 50s, the ‘fate’ of Kashmir was hanging between the divided lands of India, Pakistan and its own free existence and for Pramatha, the guns signify how siding with one will make Kashmir a possible target of the other two. ‘A Smoky Solution’ not only points at the political future of Kashmir but is hauntingly prescient, for hasn’t Kashmir been at the tip of warring emotions and barrels ever since?

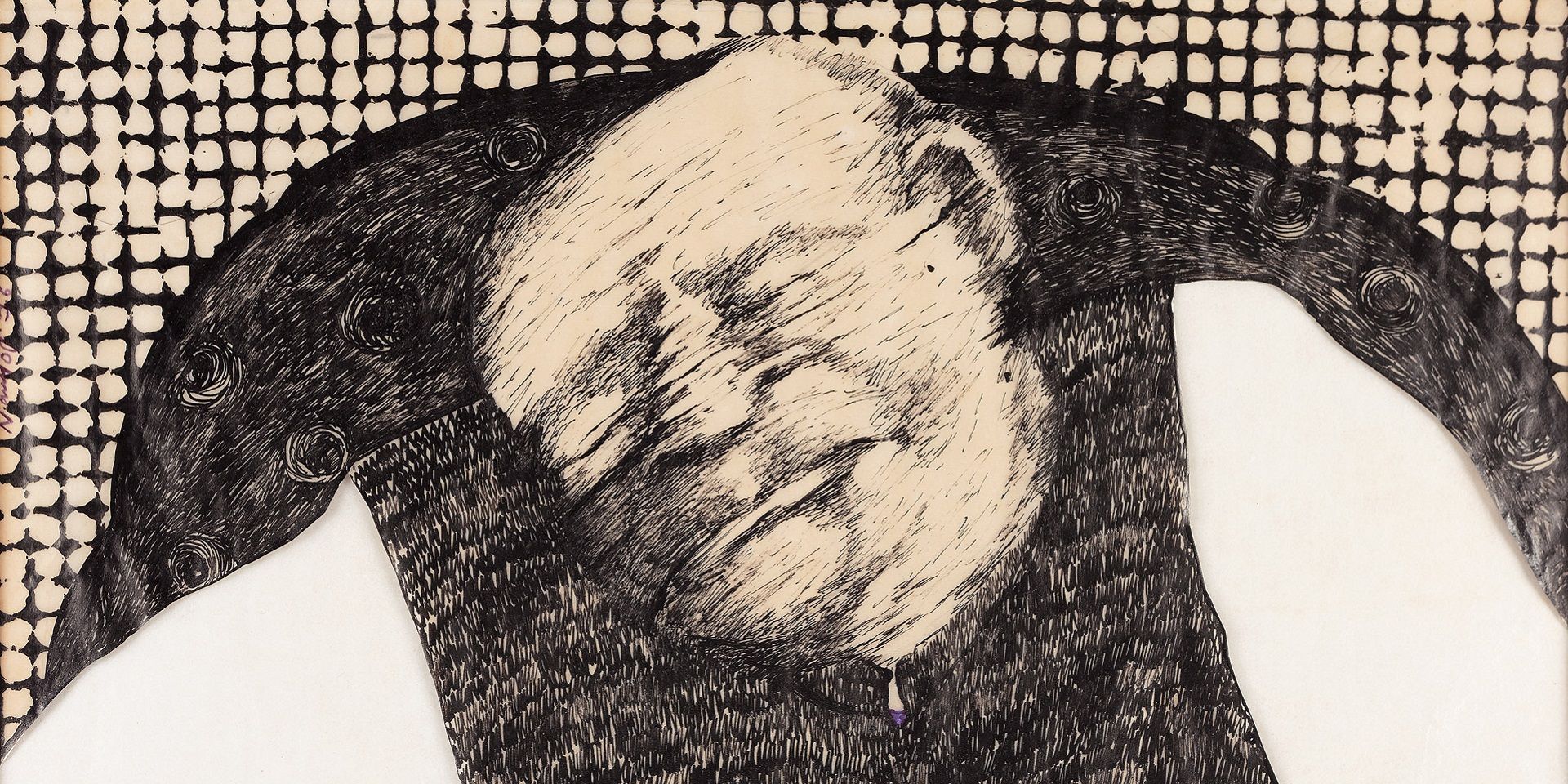

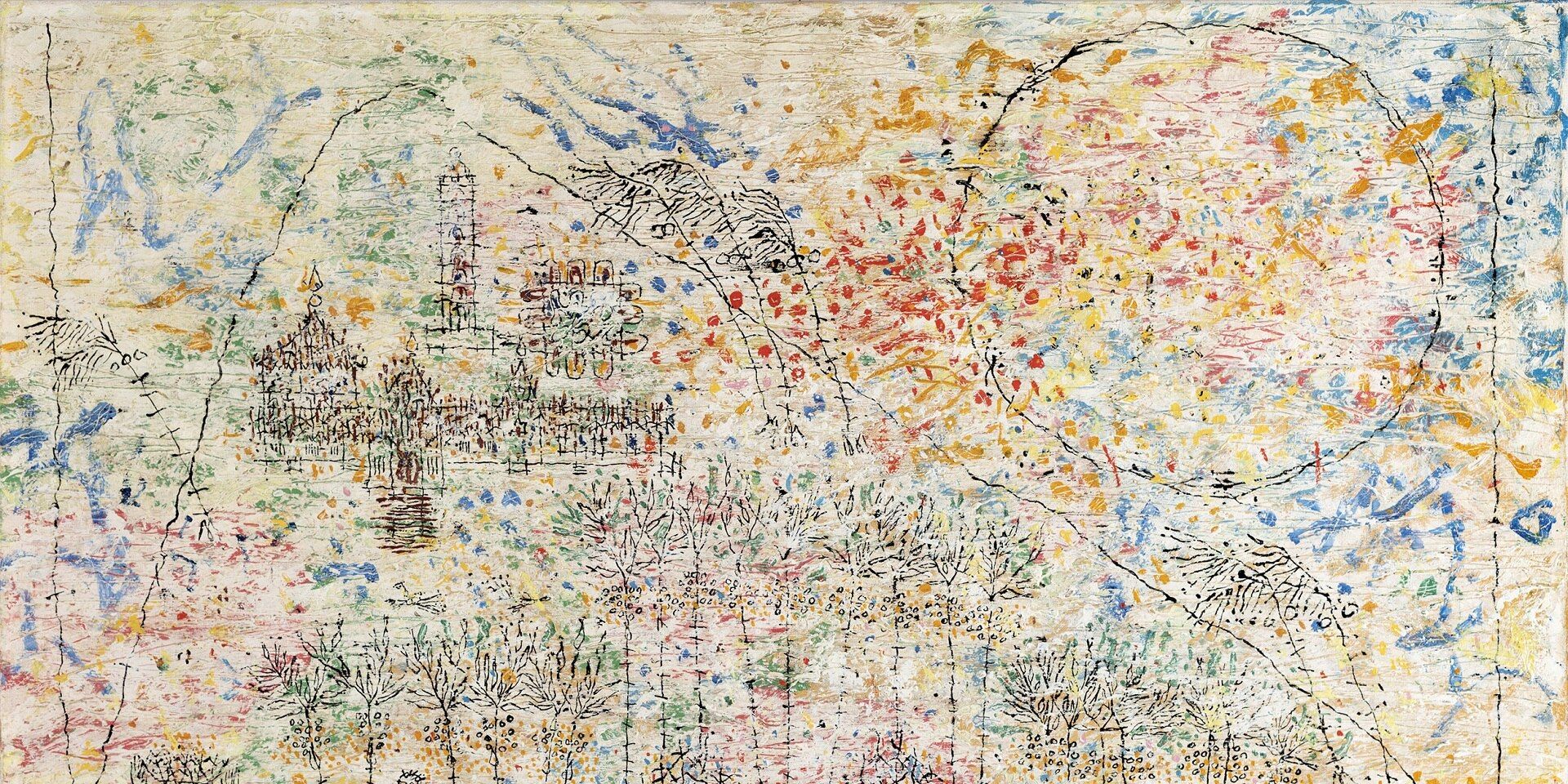

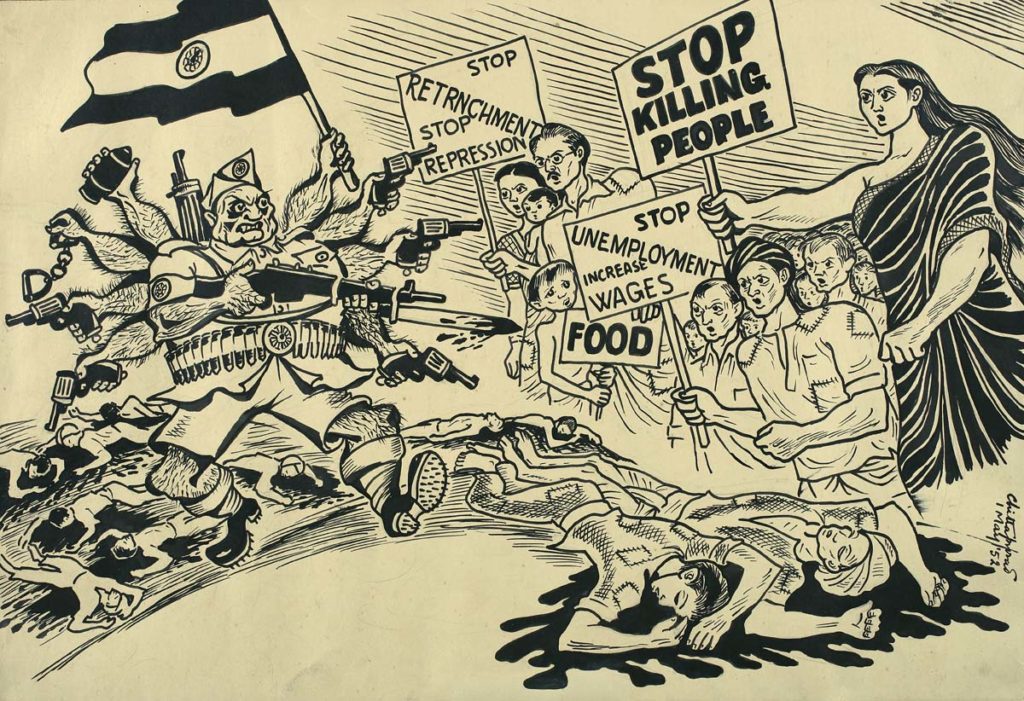

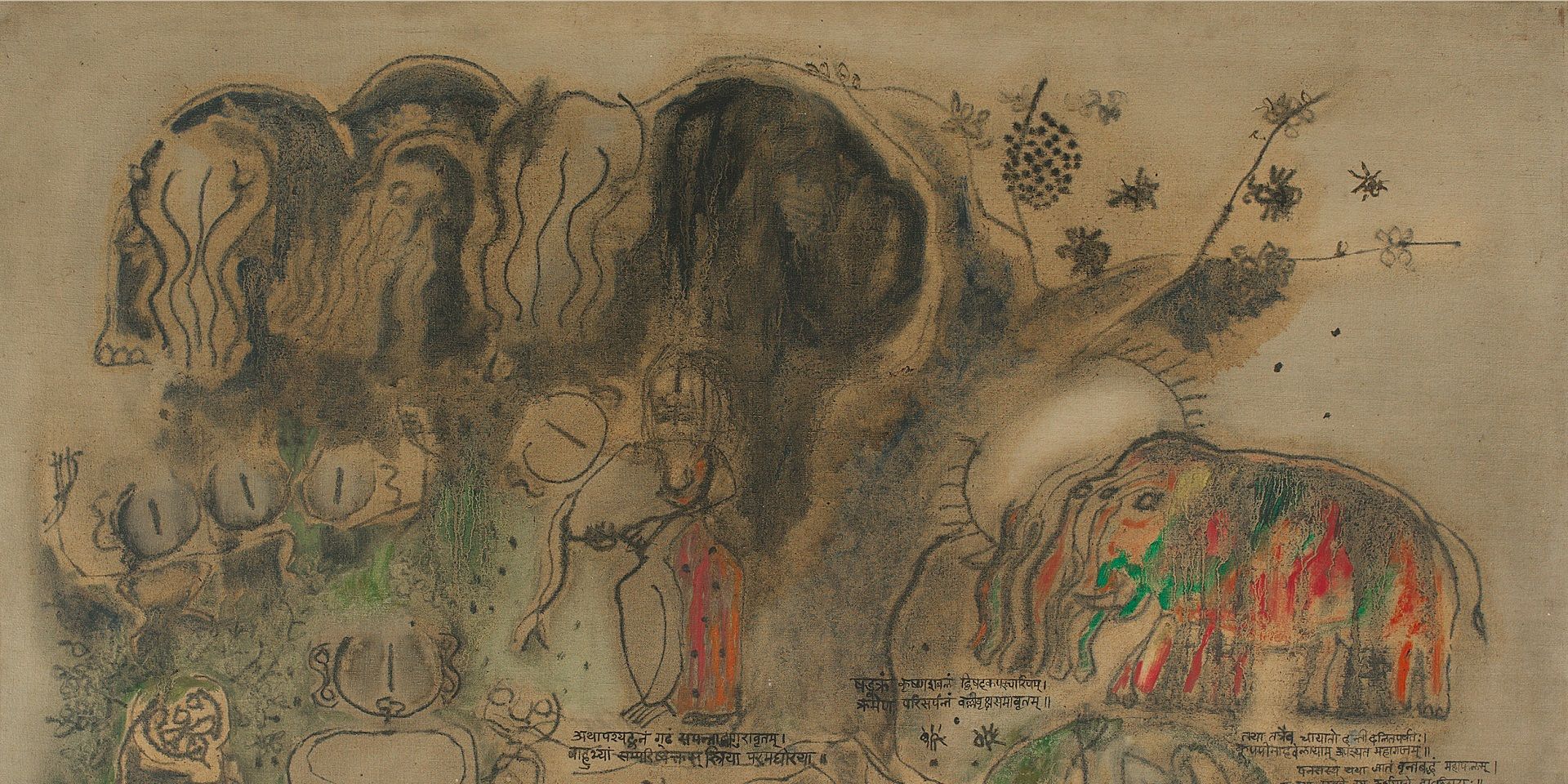

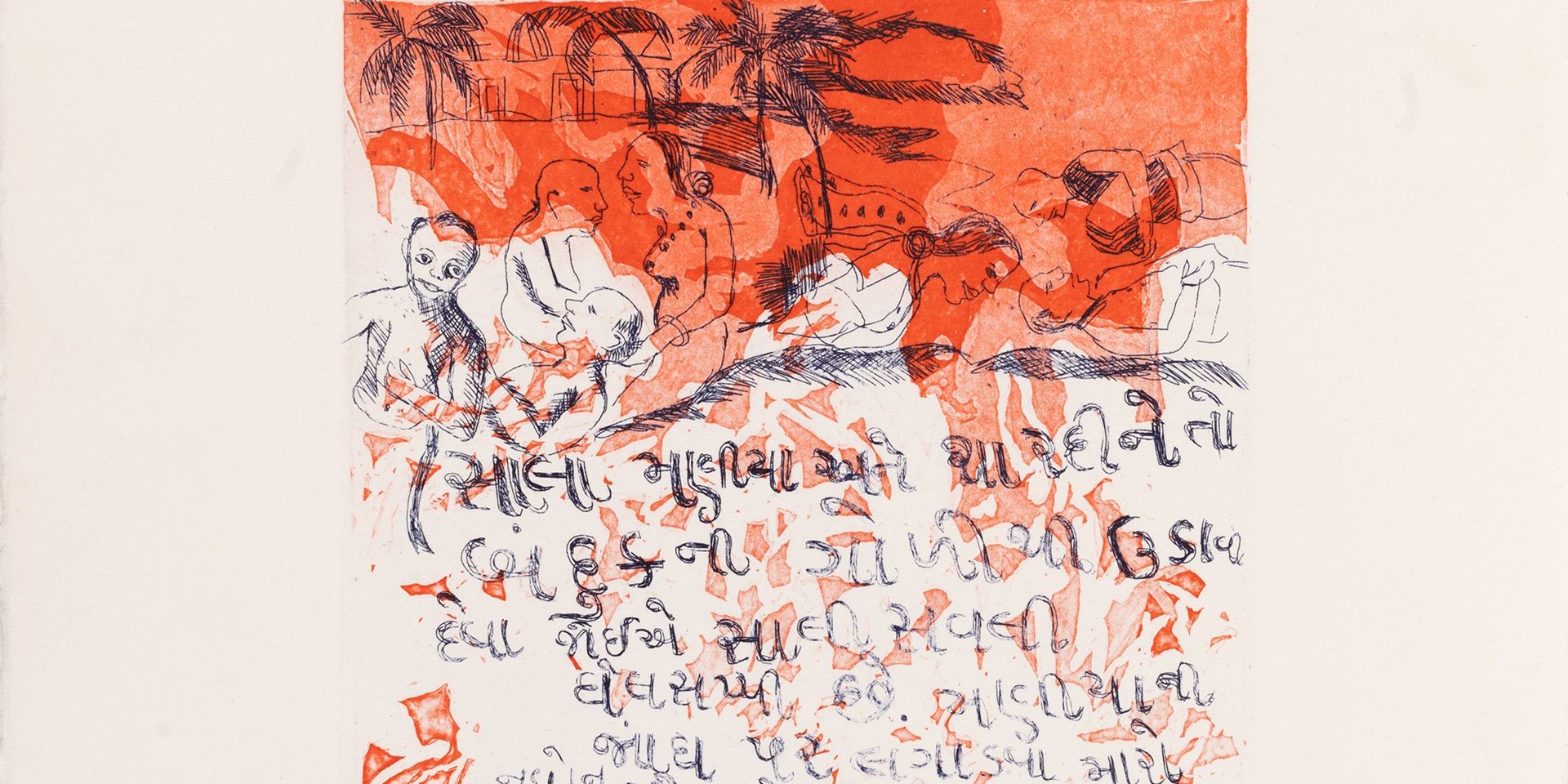

Chittaprosad, Untitled, Brush and ink on paper, 1952, 13.5 x 20.0 in./ 34.3 x 50.8 cm. Collection: DAG

Chittaprosad is not anymore considered exclusively a ‘leftwing practitioner’, though he always considered art as a war cry, a despatch from sites of oppression and disenfranchisement. Famous for his cultural journalism during the Bengal famine, Chittaprosad repeatedly viewed ‘independence’ as a set of entrenched compromises for the people of India. Here, the Indian state, indicated distinctly with the fluttering tricolour, is seen as a ten-armed gangster in a cop’s clothing, which with bracing teeth lounges itself into an all-out assault on the communion of people demanding food, employment and increase in wages. Bloodied corpses lie astray. Strikingly, the wheel (or chakra) of the tricolour is also the contraption that holds the gangster’s bandolier together around his protruding waist.

Strikingly, none of the three caricatures are really comic but are rather popular, illustrative (and mass market) art that powerfully pushes the envelope of the form, positions the artist inside the political rigmarole of his present, and sees the newly free Indian state as the new nemesis of the people rather than as their deliverer to a ‘new Jerusalem’. Clearly, the sharp, uncompromising tone of caricature as noir-satire found a new purpose in post-colonial India, rather than siding sentimentally with the notional value of freedom.

Further Reading

Richard Scully and Andrekos Varnava (ed). Comic Empires: Imperialism in Cartoons, Caricature, and Satirical Art, Manchester University Press, 2020, p 3.

Matthew Kaiser. Introduction, A Cultural History of Comedy in the Age of Empire, Bloomsbury, 2020.

Partha Mitter, ‘Cartoons of the Raj’, History Today, 47:9, 1997, pp 16-21, p 19.

Sayandeb Chowdhury teaches in the School of Letters, Ambedkar University Delhi. His work has appeared (or forthcoming) in journals and anthologies published by Intellect, Routledge, Palgrave Macmillan and university presses of Brussels, Amsterdam and Manchester. He has been a UKNA Fellow at IIAS, Leiden and a Charles Wallace UK Fellow, and is the author of Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema (Bloomsbury Academic, 2021). His major projects include co-founding a public history archive of caricature and graphic storytelling in Bengal, called https://humourinbengal.info/; He is a regular, bilingual contributor to a range of cultural press in India and internationally.

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024