On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

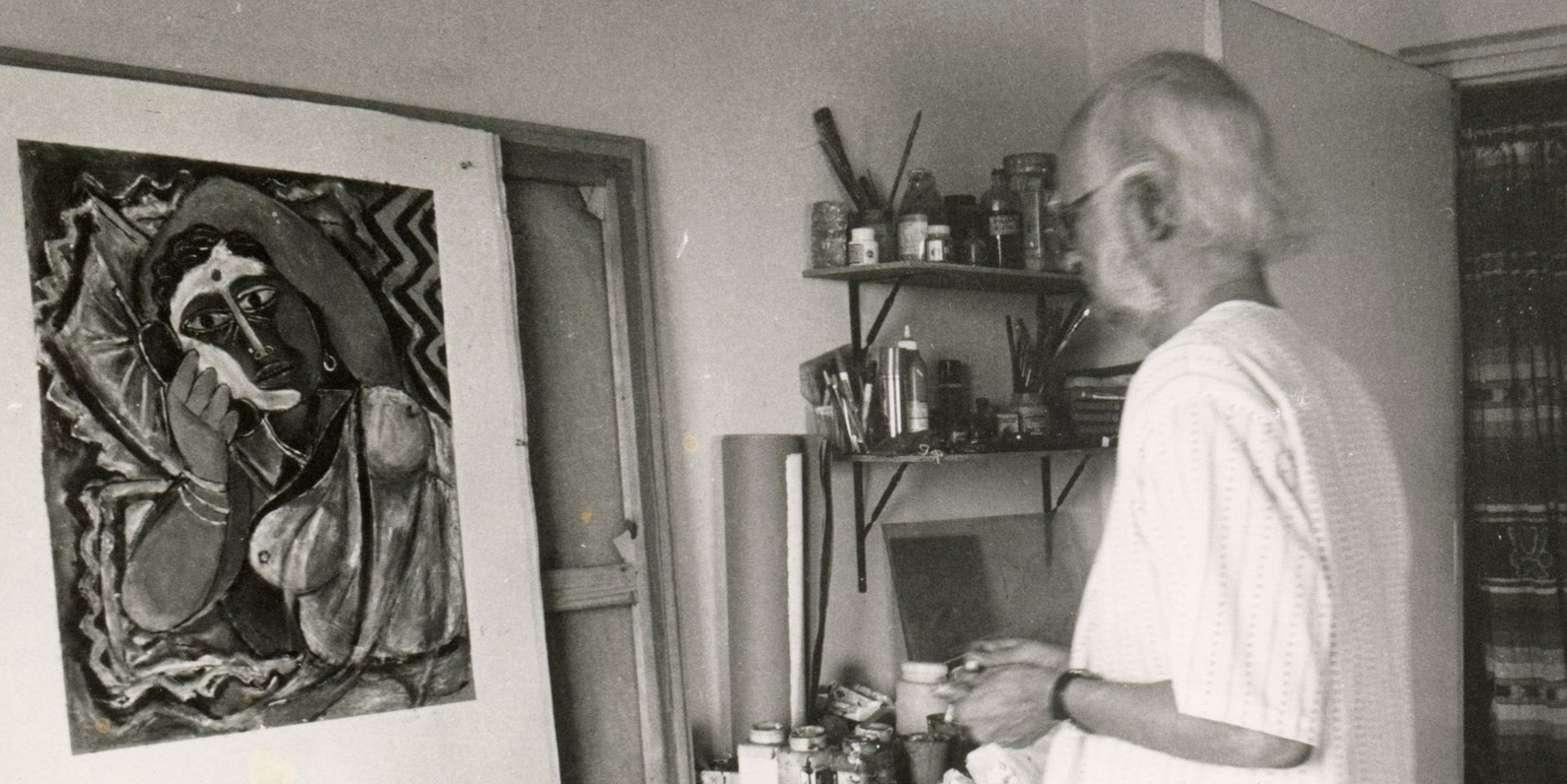

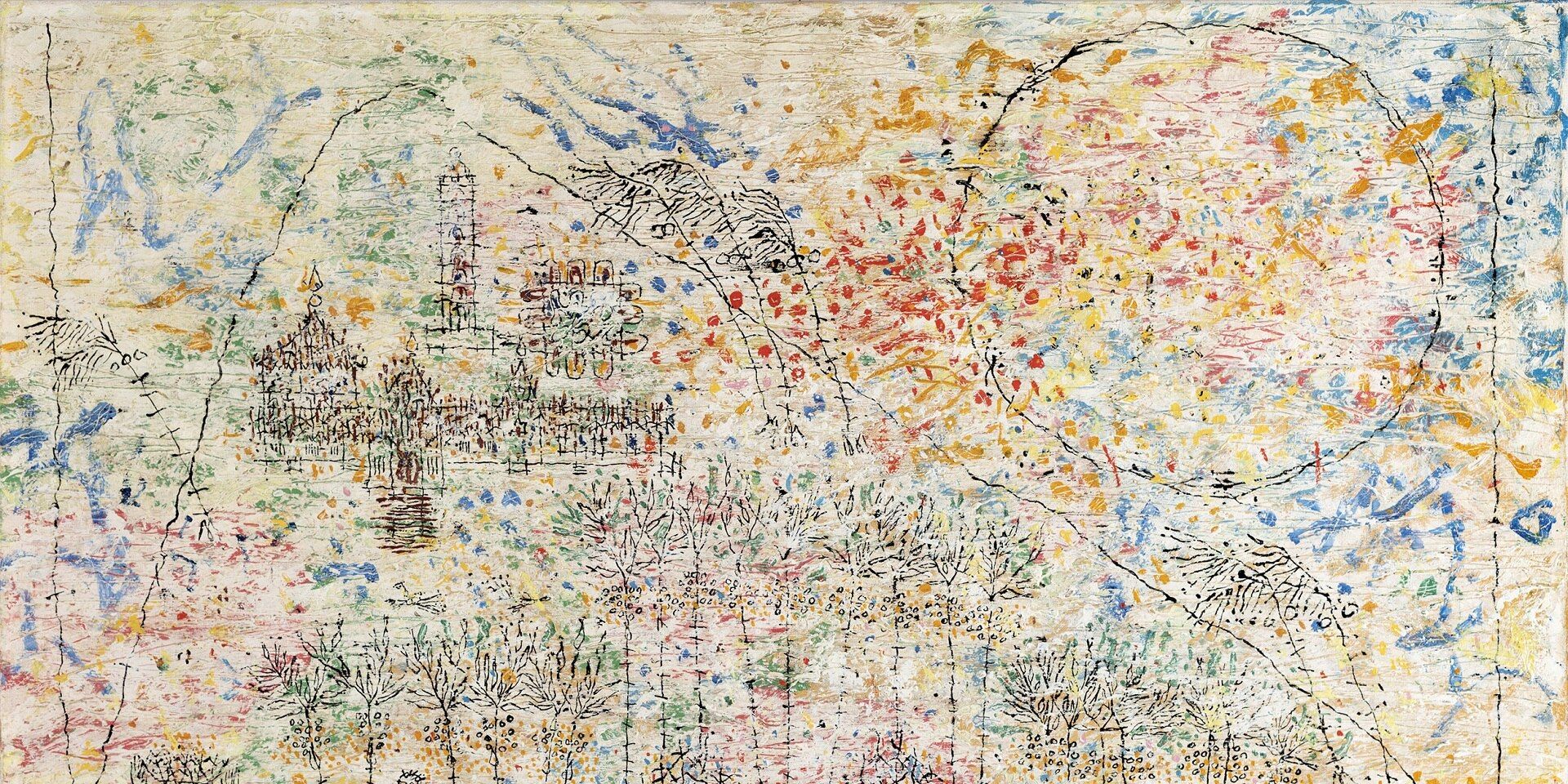

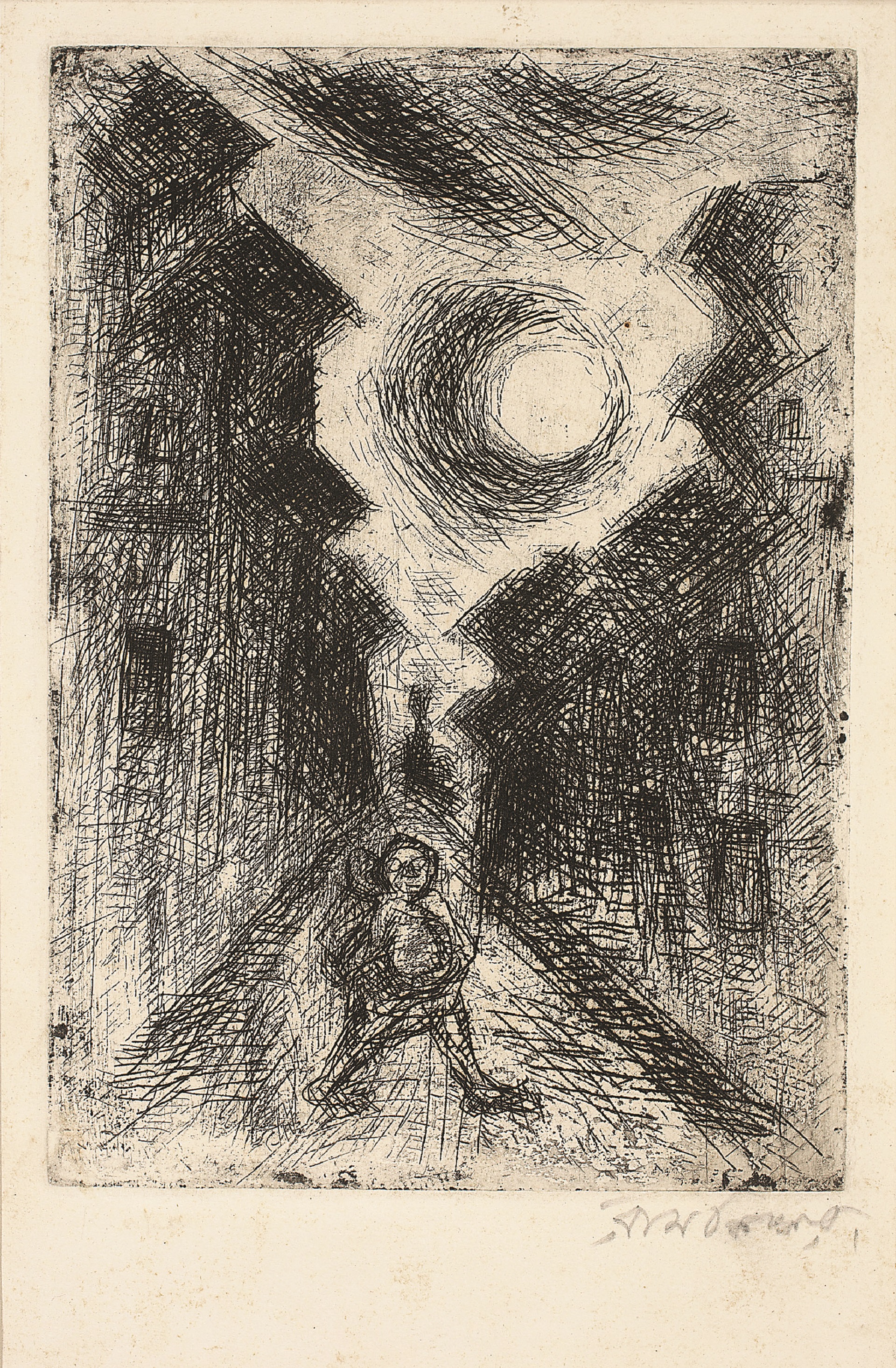

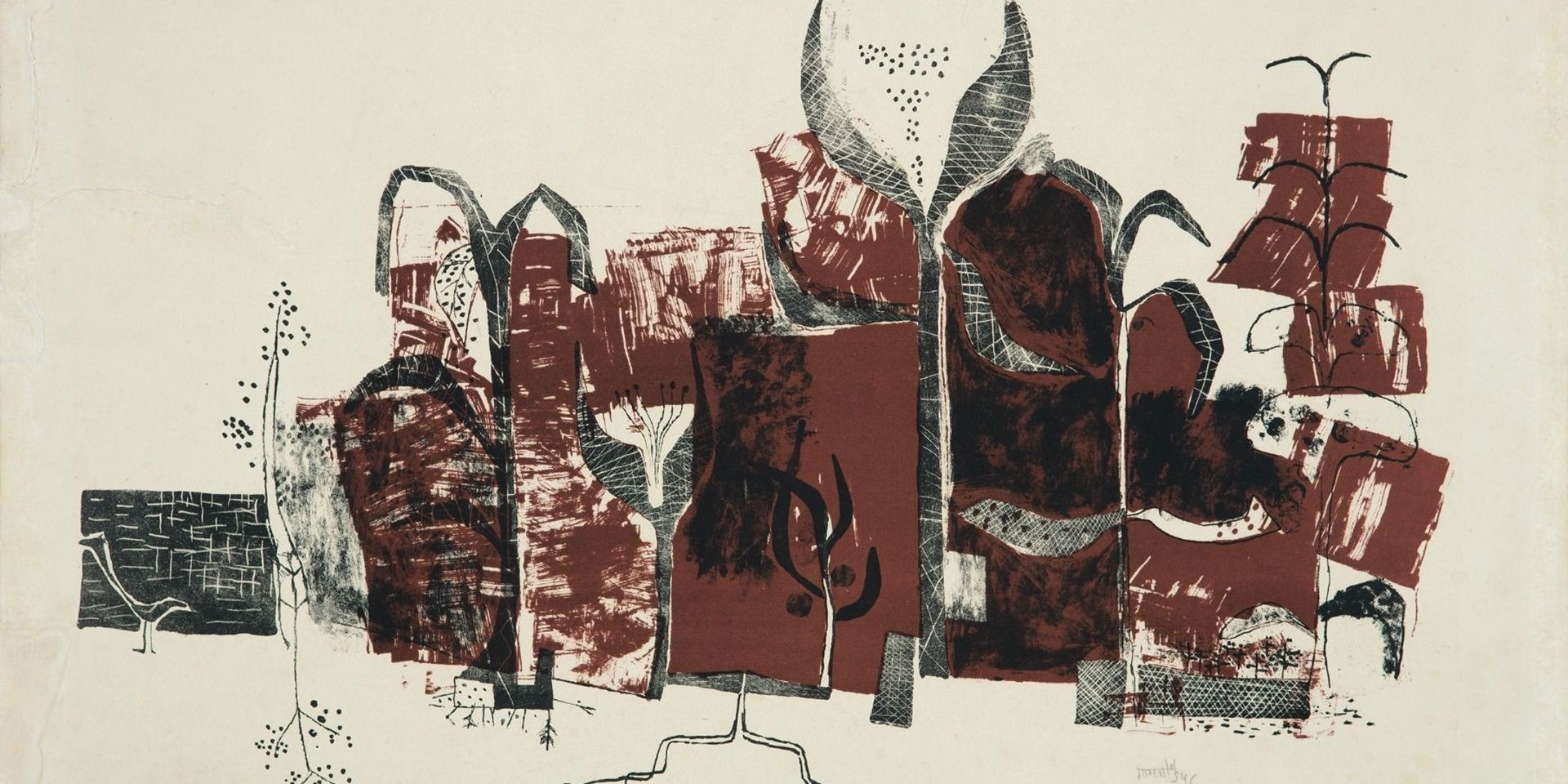

Ramkinkar Baij, Untitled (detail), Etching on paper, Collection: DAG

One evening in Santiniketan, the pathway leading to the home of the poet and artist Rabindranath Tagore was bathed in soft, dim light. Ramkinkar Baij, his student, stood there like a shadow, holding his breath, his mind racing with thoughts as ‘Gurudeb’ had summoned him for a meeting. Tagore affectionately called Baij into his room and said, ’Fill up the space with your sculpture and artwork. Finish one, and start the next. Go ahead like this, and don’t ever look back.’ Happy and elated, Ramkinkar, while recalling this story much later said, ’After hearing that, I didn’t look back either’.

|

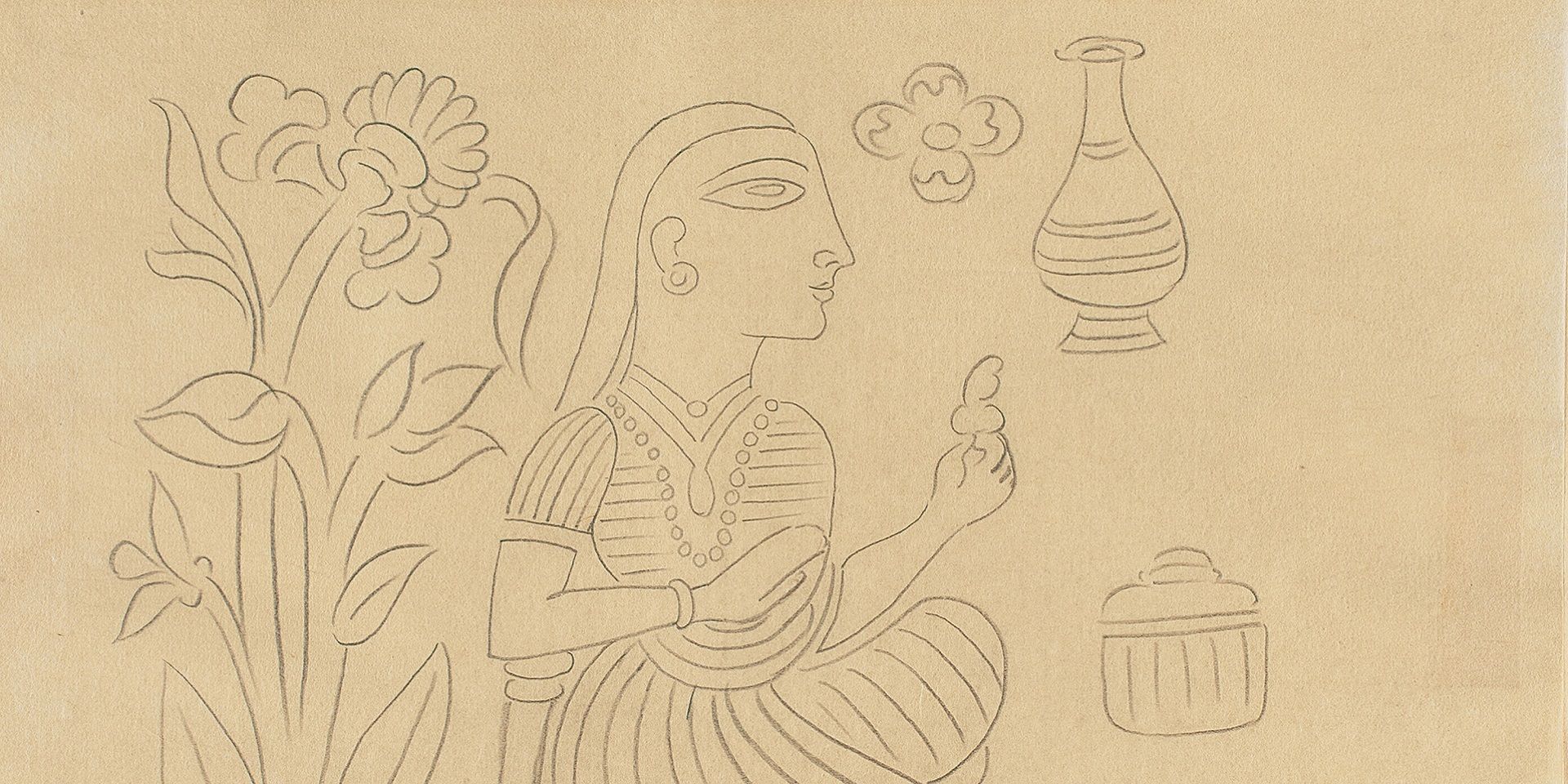

Ramkinkar Baij, Untitled, Etching on paper, Collection: DAG |

In 1987, when Samaresh Basu (1924—1988) began publishing a biographical novel on Ramkinkar Baij, he chose to draw from the essence of this anecdote and named his text Dekhi Nai Phire (Not Looking Back). On 27 January 1987, the first installment titled Roudradogdho Deergho Belar Ekdin (A Scorching Long Afternoon) was published in a noted bi-monthly magazine named ‘Desh’. Samaresh Basu, who rose to popularity in Bengali literature during the 1960s, was one of the few authors who pursued writing as a full-time profession. Several of his acclaimed novels such as Amritakumbher Sandhane (In Search of the Holy Grail), Shambo, and Mahakaler Rahther Ghora (The Horse of the Chariot of Time) became favourites among readers, while some of his other works sparked controversy for explicitly addressing Bengali middle-class hypocrisy and sexuality. Dekhi Nai Phire, Basu's last (unfinished) work, was perhaps closest to his heart.

Ramkinkar Baij, Untitled, 1961, 10.5 x 14.5 in. Collection: DAG

It is worth paying attention to the lengthy preparation that Basu went through before the first installment saw the light of print. He was attracted to the vibrant life of this self-taught sculptor who later gave a new direction to the Tagore-Nandalal legacy. Though the filmmaker Satyajit Ray once advised this acclaimed author to think about writing a biography on Benode Behari Mukherjee (another pioneer of Indian art)—it was Ramkinkar Baij that got Basu excited enough to take the hard yet much-rewarding journey on the road to writing a fascinating text that is often described as a biographical novel.

To Basu, Ramkinkar was a surprising character, and he wanted to delve into his past and present so that he could pen a clear picture of this ecstatic ‘character’s’ life, work and struggle for his readers. The process was not easy though. Initially, when the author decided to meet the artist at his Santiniketan home–the latter was quite indifferent to the idea of an authentic biography. It took time, and Basu’s eagerness, for Ramkinkar to change his mind. What was initially supposed to be limited to two meetings with the author evolved into a continuous exchange of stories with each other, and a kind of camaraderie grew between them.

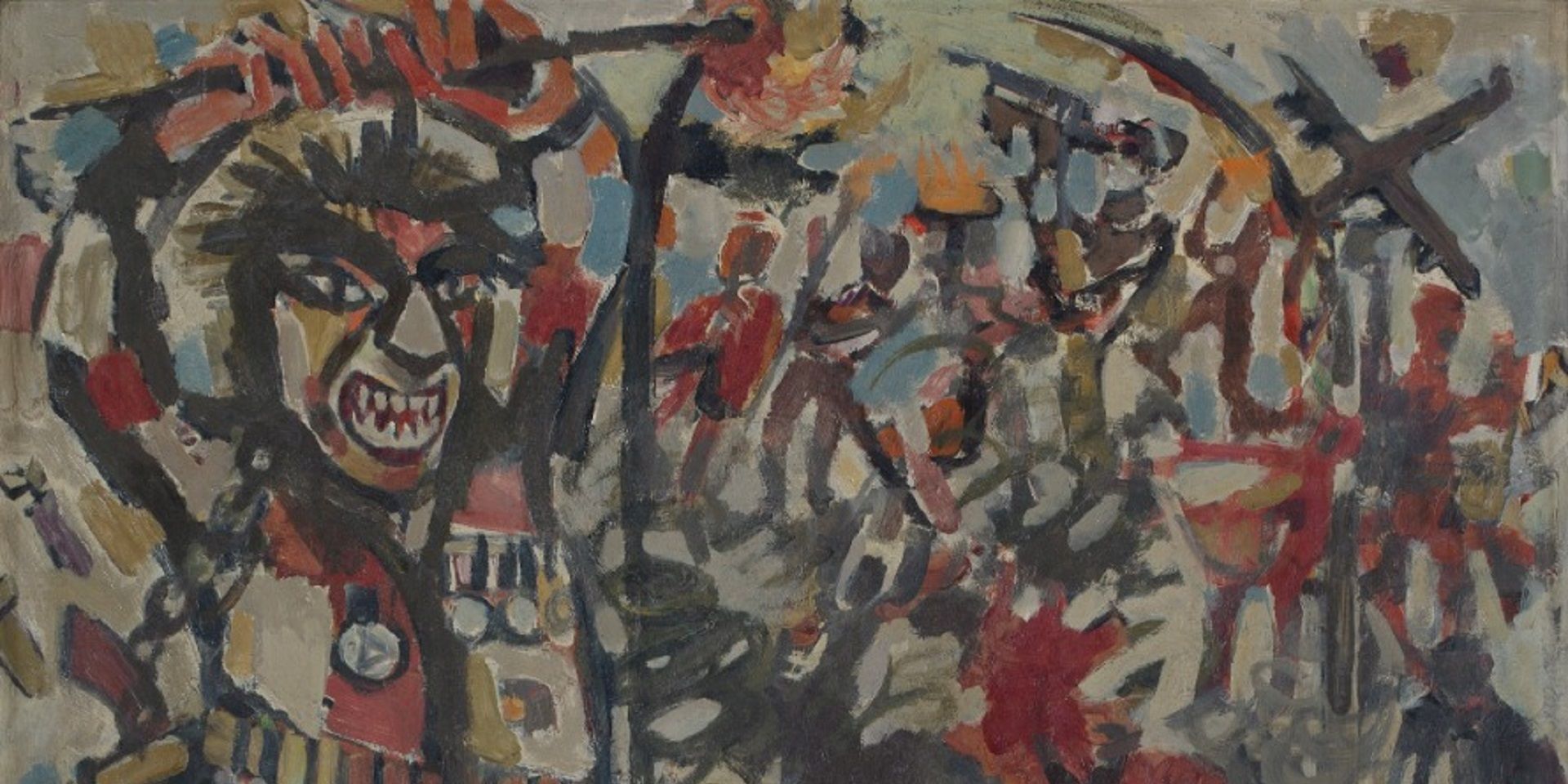

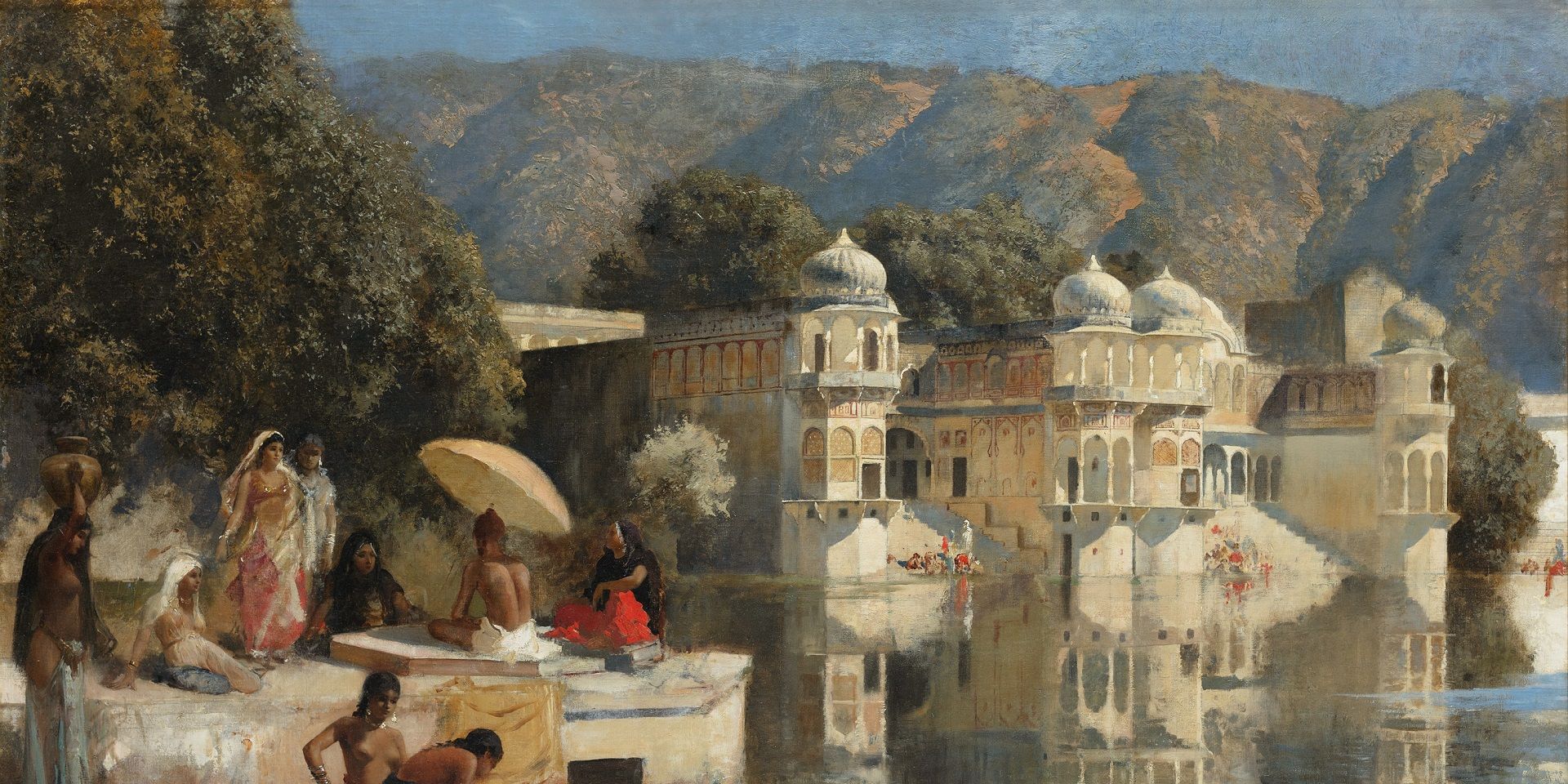

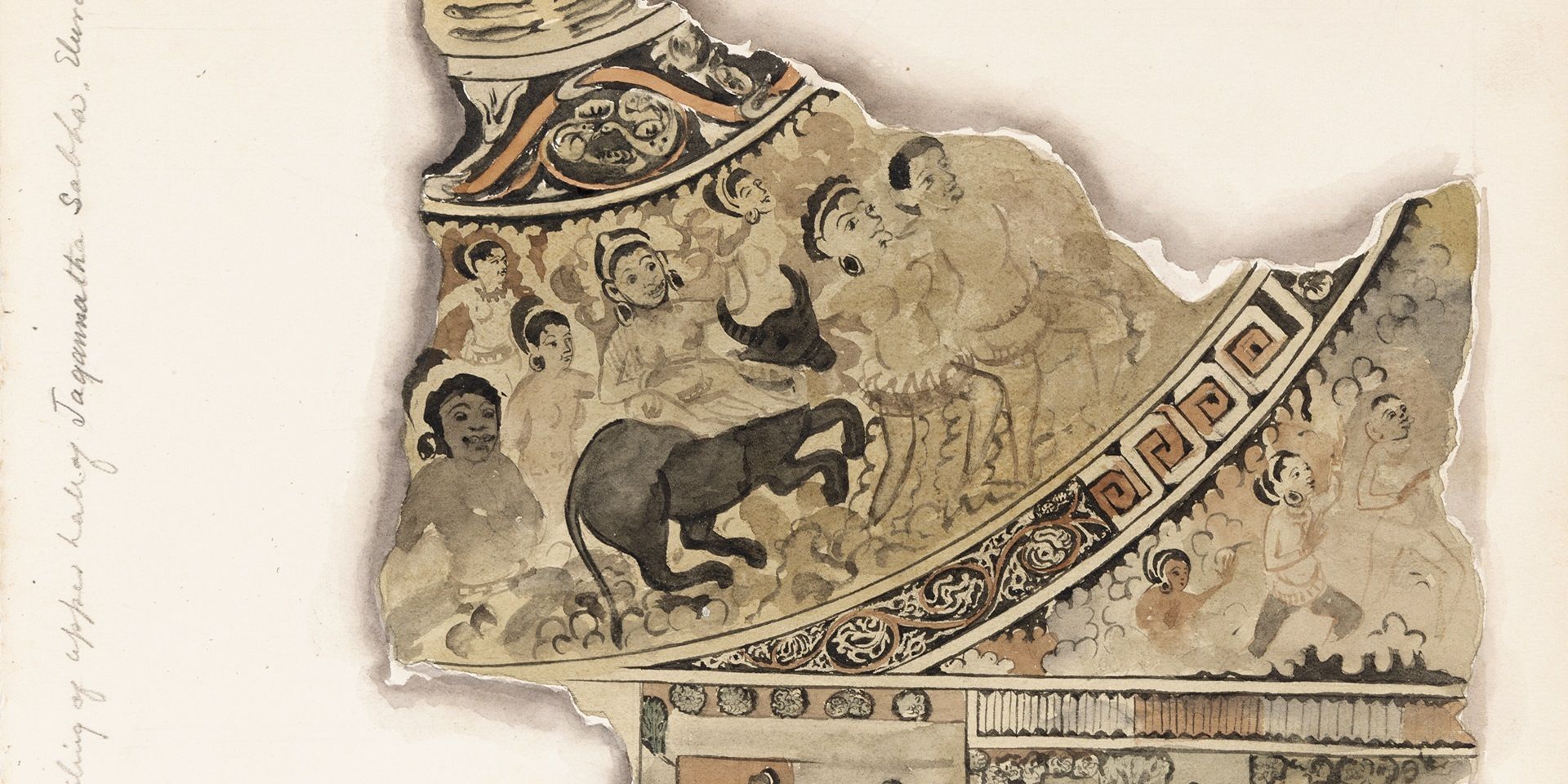

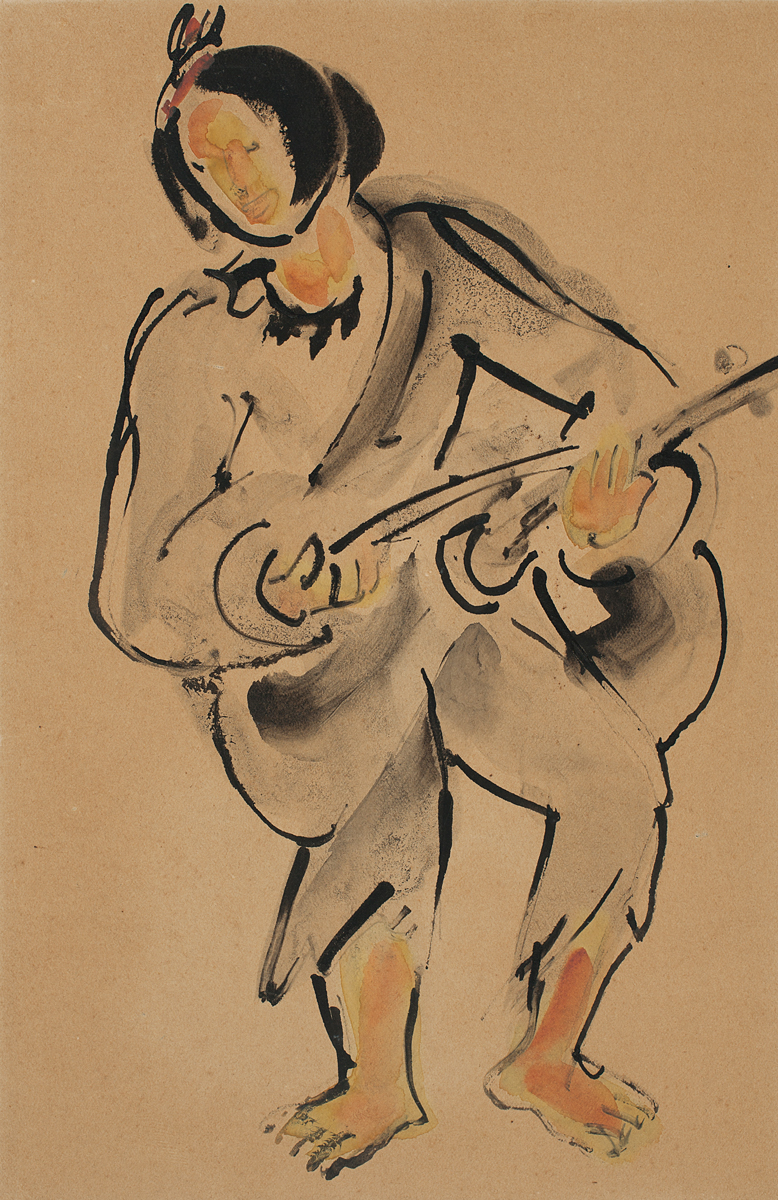

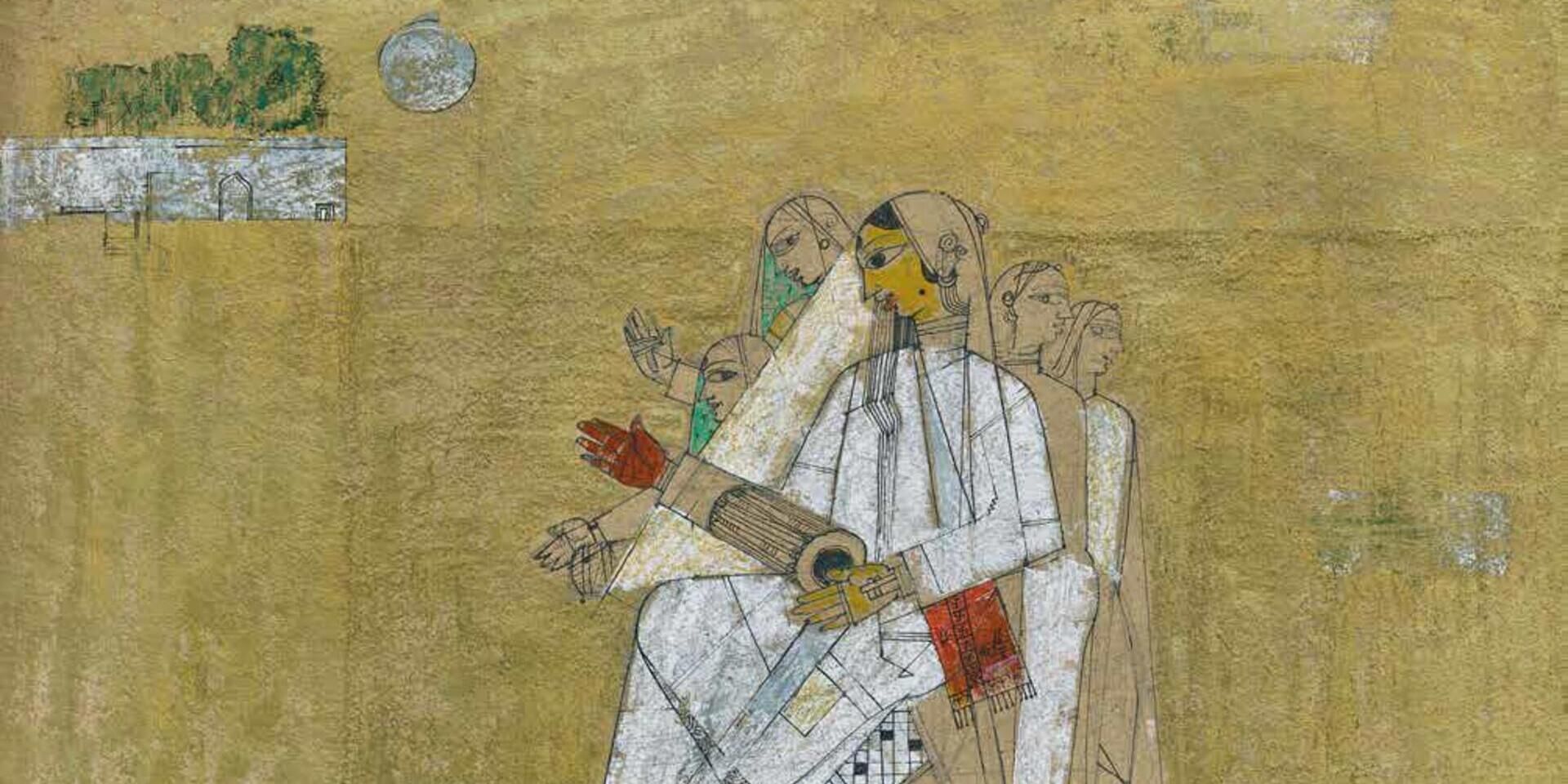

Ramkinkar Baij, Untitled, Water colour and ink on paper. Collection: DAG

Basu always thought that Ramkinkar’s life had a certain similarity with his own, and they might have a similar kind of approach to society through their work. What is especially significant about it was that Ramkinkar became the first modern Indian artist who caught the attention of a serious novelist. Though in the West, celebrated artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Michaelangelo became subjects of highly acclaimed novels—in India, it was the first of its kind.

|

Cover of the novel The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone, which depicts the life of Michelangelo. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Researching with the Artist

Ramkinkar arrived in Santiniketan at the age of nineteen, after spending his entire childhood and teenage years in Bankura. Basu's dedication to his research was such that he brought Ramkinkar back to Bankura, his birthplace, where the journey of his exceptional talent began amidst countless struggles. As Ramkinkar spoke about his life challenges and artistic approach, Basu became increasingly absorbed in these stories, finding echoes of his own creative methods within them.

Basu returned to Bankura numerous times, sometimes without the artist, to explore the places where Baij had spent his childhood and to converse with people who knew him growing up. Through these visits, Basu gradually understood that Ramkinkar was a self-taught sculptor and painter, learning through trial and error with whatever materials he could find. He created pigments from natural extracts for his colours, with clay as his primary medium. For his monumental outdoor sculptures, he used mixtures of cement and pebbles.

For Basu, going back to Ramkinkar’s native place was very rewarding. His thorough research with the artist, and with the locals, even picking up the local dialect, allowed him to weave the magic tale of Baij’s childhood through his words. Despite incorporating fictionalised elements in Dekhi Nai Phire, Basu's portrayal felt authentic to his readers. In a letter to the editor of ‘Desh’ magazine, Sagarmoy Ghosh, Basu wrote, ‘I am immersed in Ramkinkar. His local dialect is under my control. I can clearly see Bankura city as it was seventy years ago.’

|

Ramkinkar Baij, Santhal Family, 1938. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

The controversial Artist through the eyes of a controversial Author

Ramkinkar's journey is that of a Dalit boy who was introduced to sculpting by village idol makers, eventually becoming a notable figure in India's modern art scene. Only someone like Samaresh Basu had the courage to write a fictionalised biography of such an artist. Baij encountered numerous struggles in both his personal and professional life due to his unconventional approach to work and his social class. As a young man, he abandoned his real surname Paramanik and adopted Baij or Baiddyo. Yet, he remained actively engaged in challenging the hypocrisy of the so-called cultured Bengali society. This aspect particularly intrigued Basu and motivated him to write about Baij. If one examines Samaresh Basu's body of work, the approach is strikingly similar. Two of Basu's novels, Bibar (The Vagabond) and Prajapati (The Progenitor), stirred controversy and were banned on grounds of indecency. Similarly, Ramkinkar's artworks consistently questioned the established norms of Bengali society.

Both Baij and Basu were connected deeply to their contemporary social reality. While painting the life of a labourer, or a farmer—Ramkinkar was very much aware of their lives and conditions. Even Basu knew well about the social realities of potters and fishermen while writing novels about them. Despite facing controversy, Basu had a keen ability to perceive through his own eyes the dilemmas and social messages embedded in the artist's works.

Ramkinkar passed away even before Basu was able to publish the first chapter of this work. But to Basu the rhythm and movement of Ramkinkar’s life and work had already become very clear—so he decided to continue with the writing. The only change that he made after Ramkinkar’s death was to shift the approach of the book from an authentic biography to a biographical novel.

And the work remains unfinished

Dekhi Nai Phire marked a pivotal moment in Basu’s journey to discover the essence of creative vision. Finally, his life as an author was coming full circle. Surprisingly enough, his first novel Nayanpurer Maati (The Soil of Nayanpur, written in 1946, published in 1952) was also a story about sculptors and potters. Though so close to his heart, Basu did not live long enough to see the story through. The author passed away on 12 March, 1988.

|

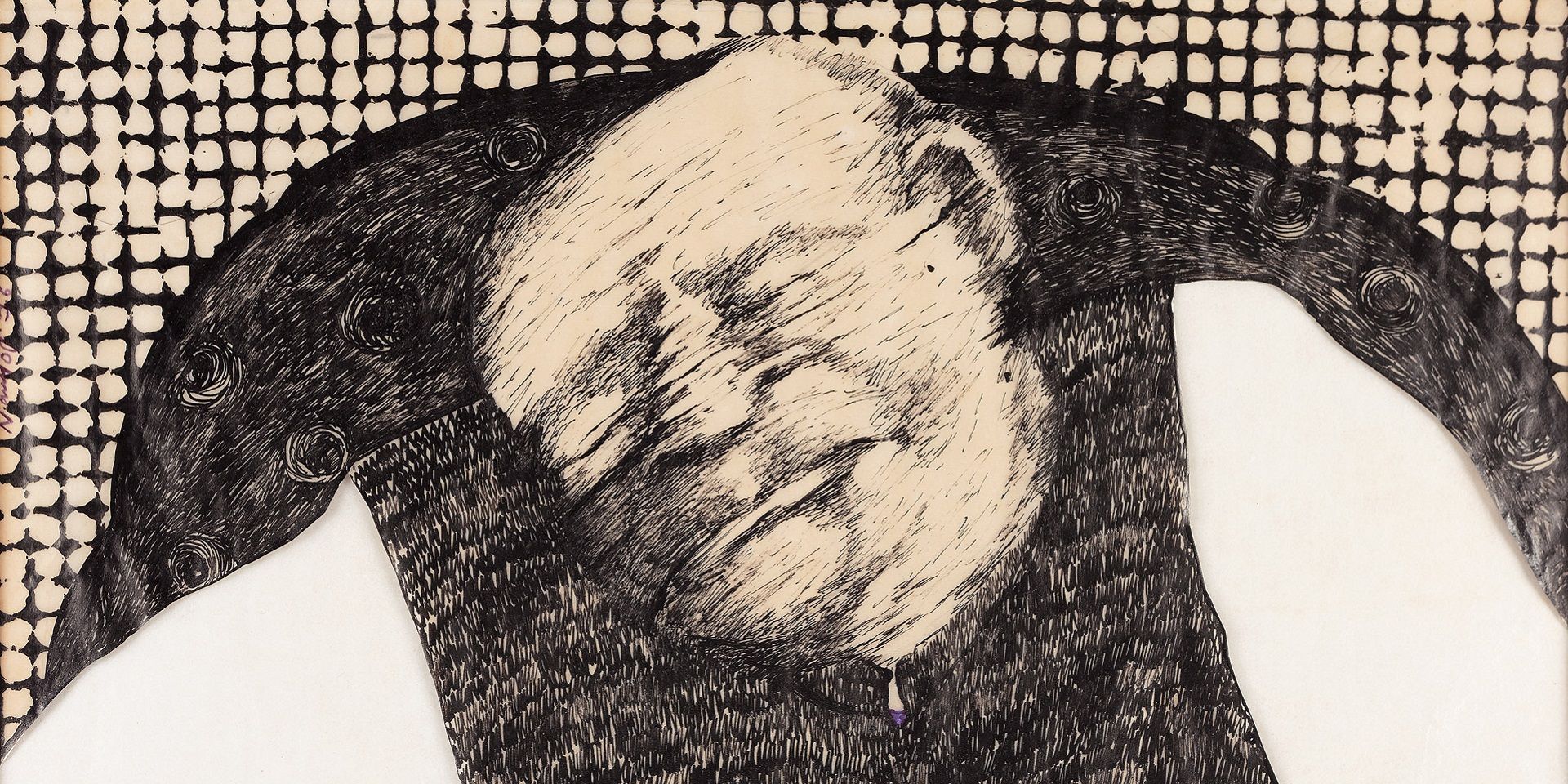

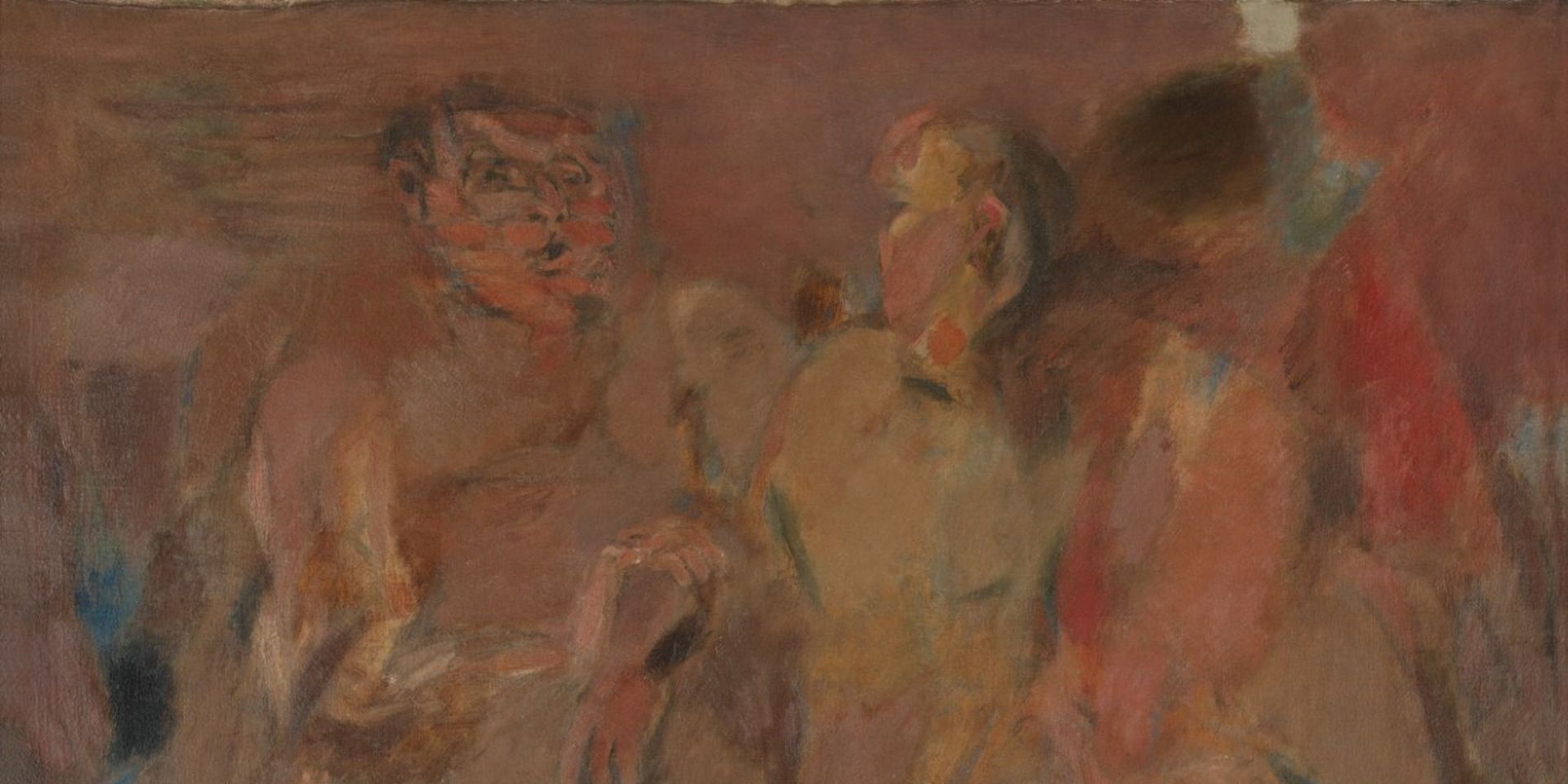

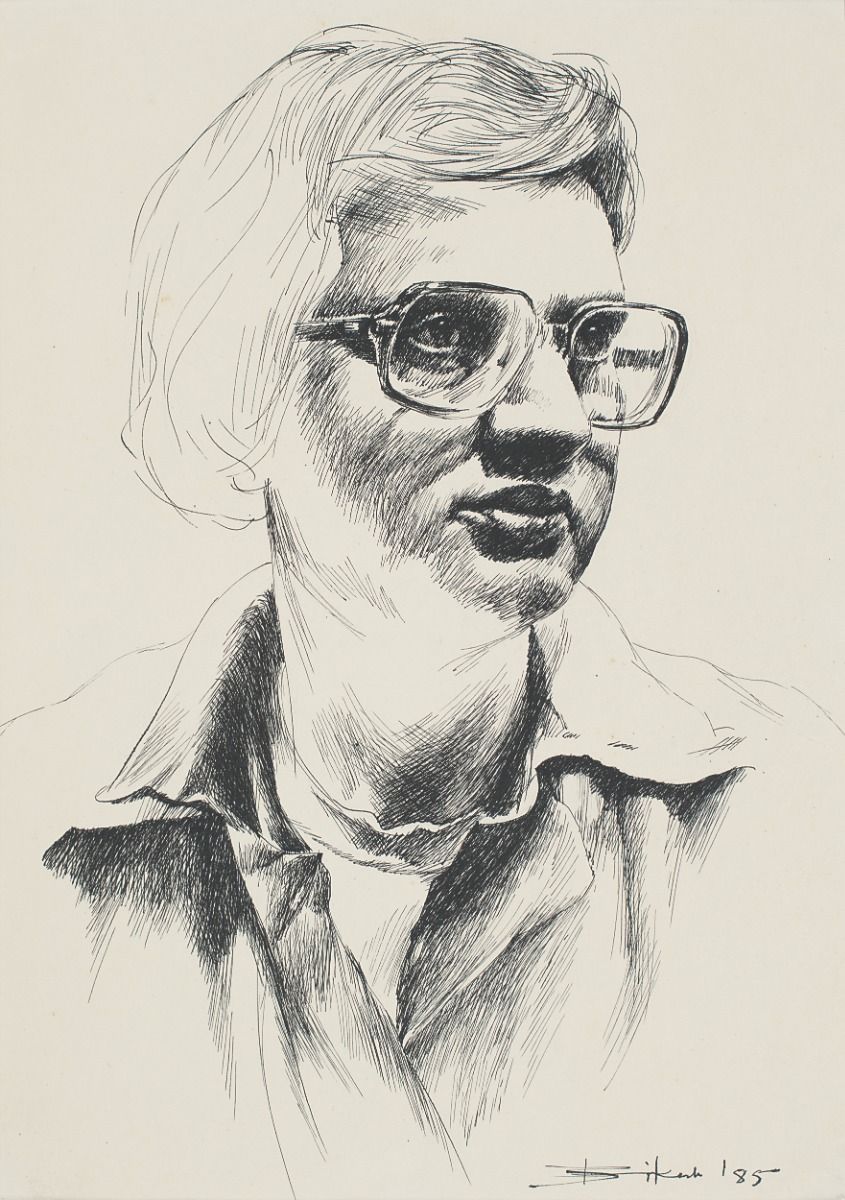

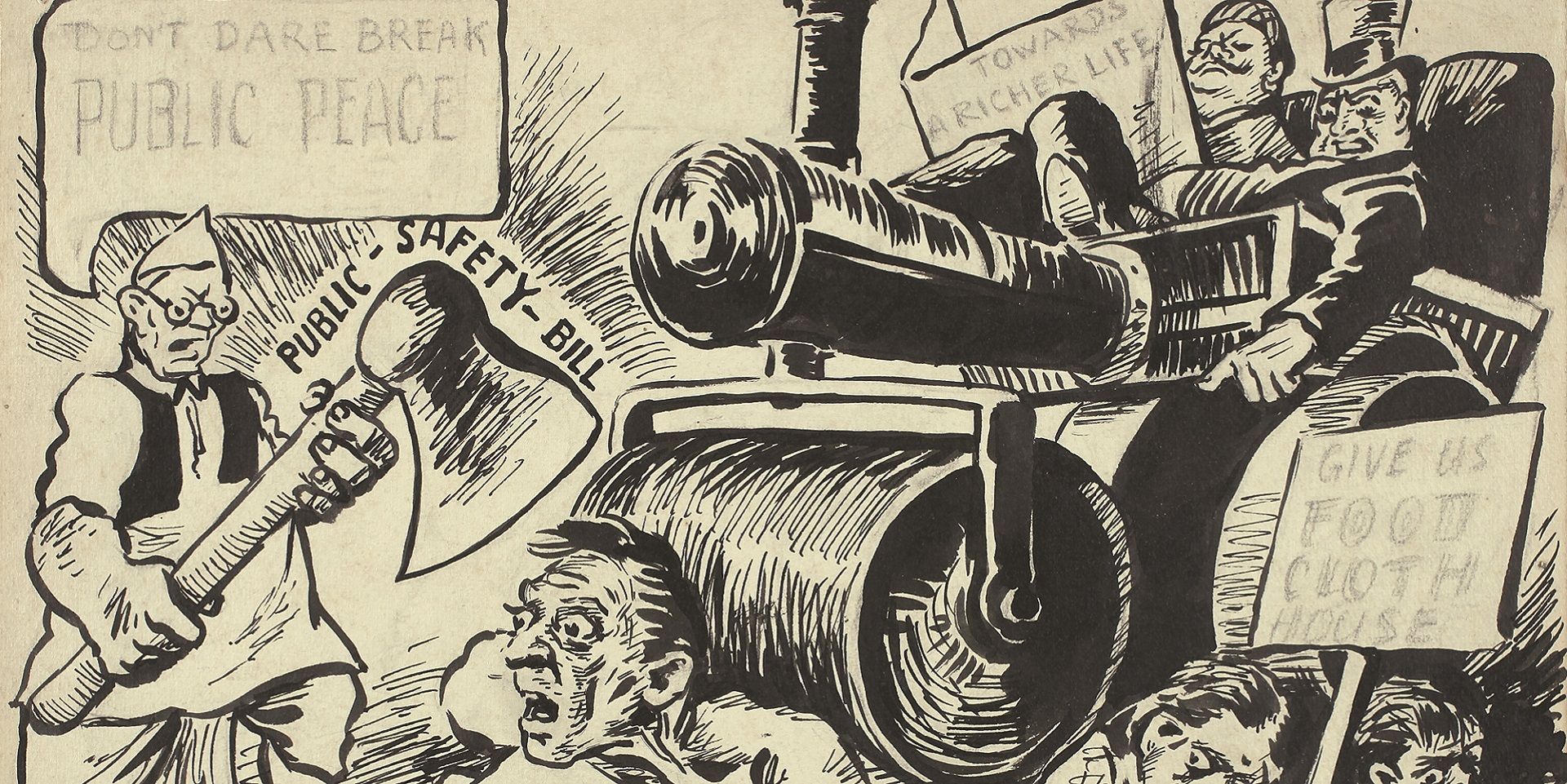

Bikash Bhattacharjee, Untitled, 1985, Ink on paper, 9.2 x 6.5 in. Collection: DAG |

The artist Bikash Bhattacharjee (1940—2006), who was illustrating Dekhi Nai Phire for ‘Desh’, mentioned how his depiction of Ramkinkar Baij had begun to subtly reflect the facial features of Samaresh Basu as well. He said, ‘I knew both Ramkinkar da, and Samaresh da. They have the same passion and blazing courage. They both have a primitive, wild streak. They have (a) simple and clear laugh. I found Ramkinkar's life blending seamlessly with Samaresh's introspective narrative. So, I changed the facial expressions. Then, I completely blended Ramkinkar with Samaresh's personality.’

Unfortunately, readers never got to see that. In the book that was published, which, in spite of being unfinished, runs to over seven hundred pages, one can still see Bhattacharjee’s delicate sketches, triangulating a unique creative collaboration between three iconic writers and artists of modern Bengal.

Samaresh Basu's vision for Ramkinkar Baij's life and his plans for the novel ended with his passing. Sagarmoy Ghosh was adamant that no one should attempt to complete Basu's work. He believed that no one else could have rendered the tale as enchantingly beautiful as Basu did. Thus, the magical tale remains incomplete.

|

Ramkinkar Baij, Untitled (Musician) , Water colour and ink on paper. Collection: DAG |

Debotri Ghosh is a writer and editor based in Kolkata, India. Her previous works have appeared in ABP, Bartaman Patrika, and Scroll. Her areas of interest are Bengali Literature, and Indian Films.

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

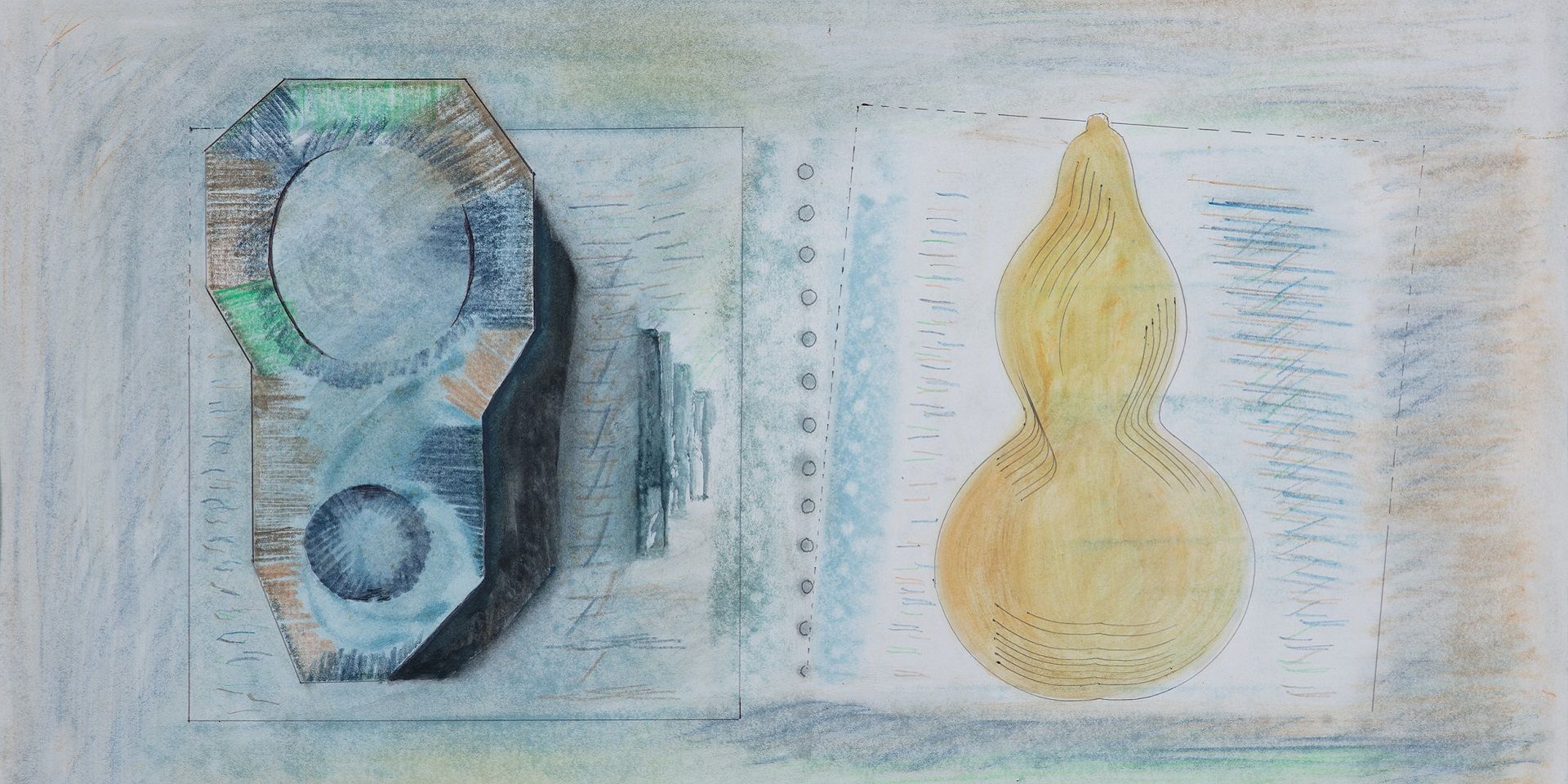

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

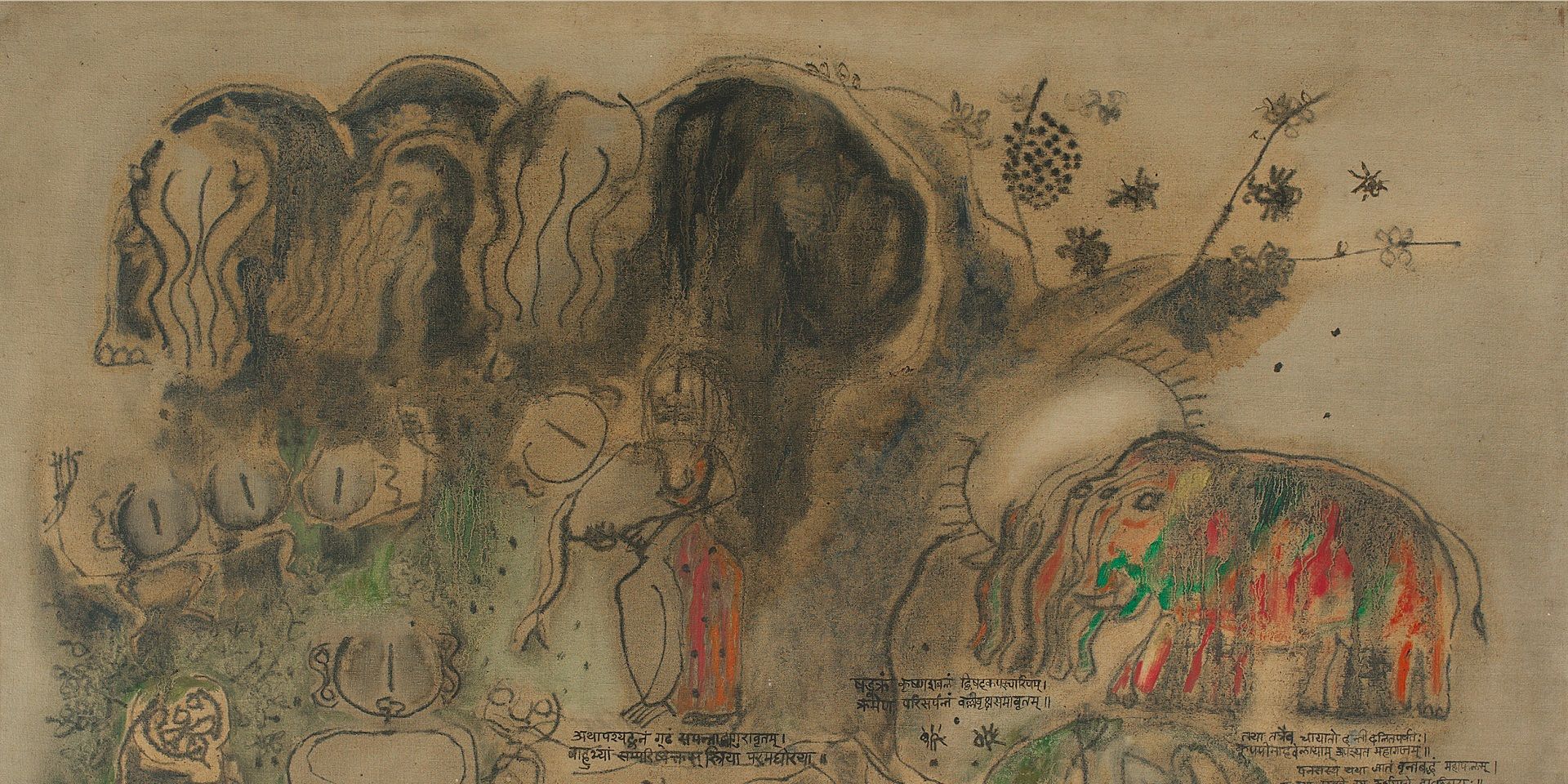

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

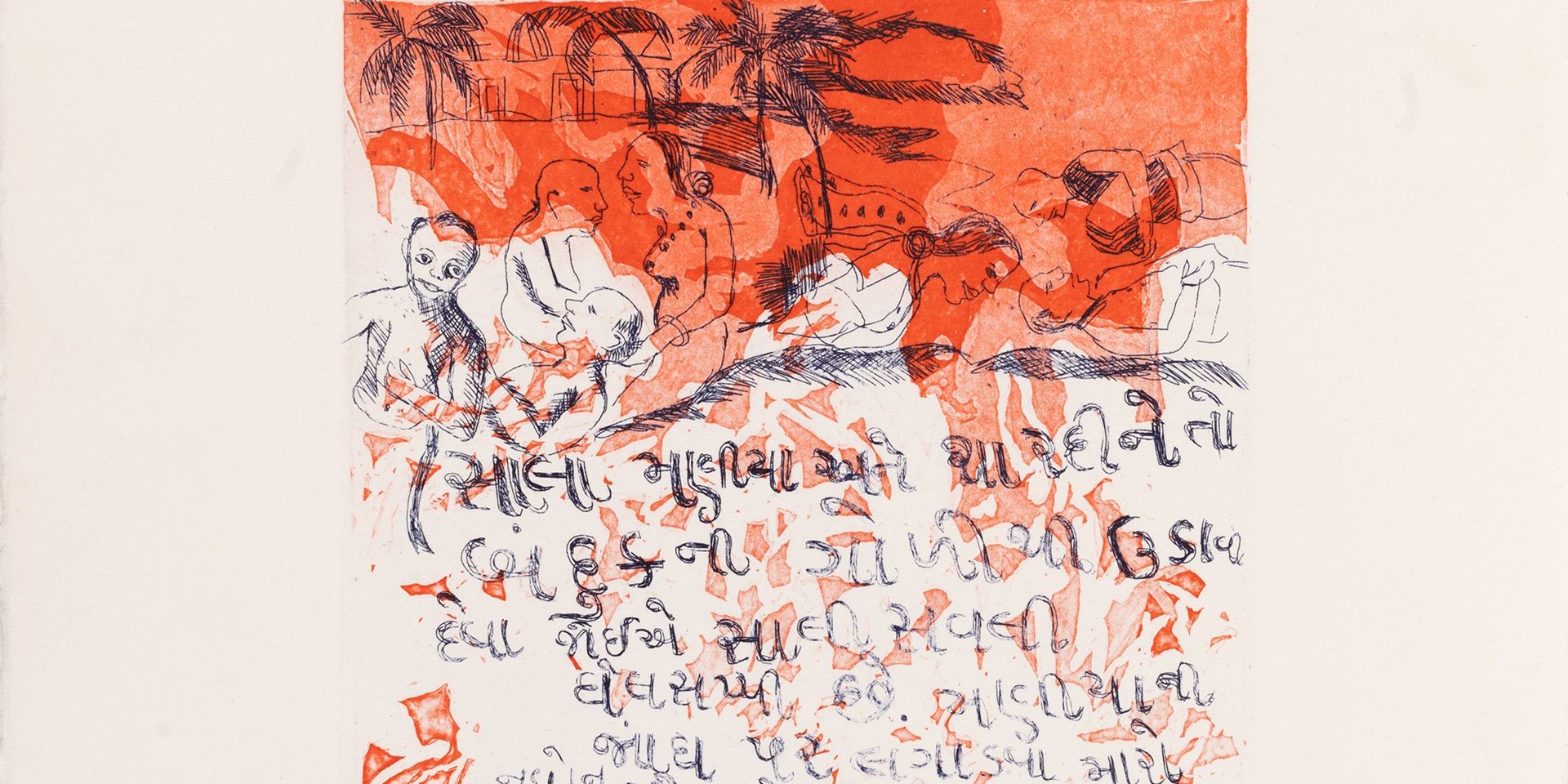

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024