Tyeb Mehta: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Tyeb Mehta: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Tyeb Mehta: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

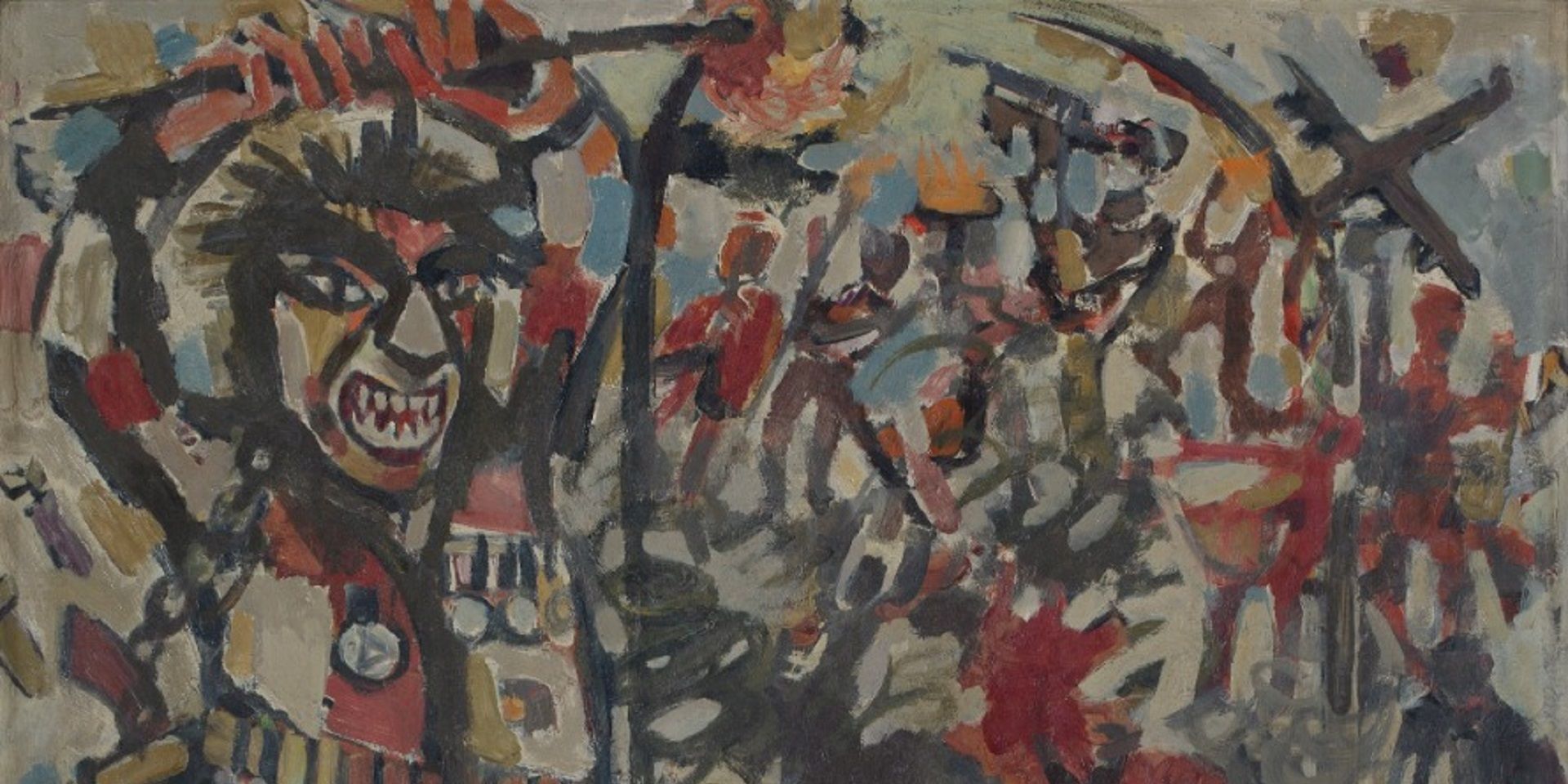

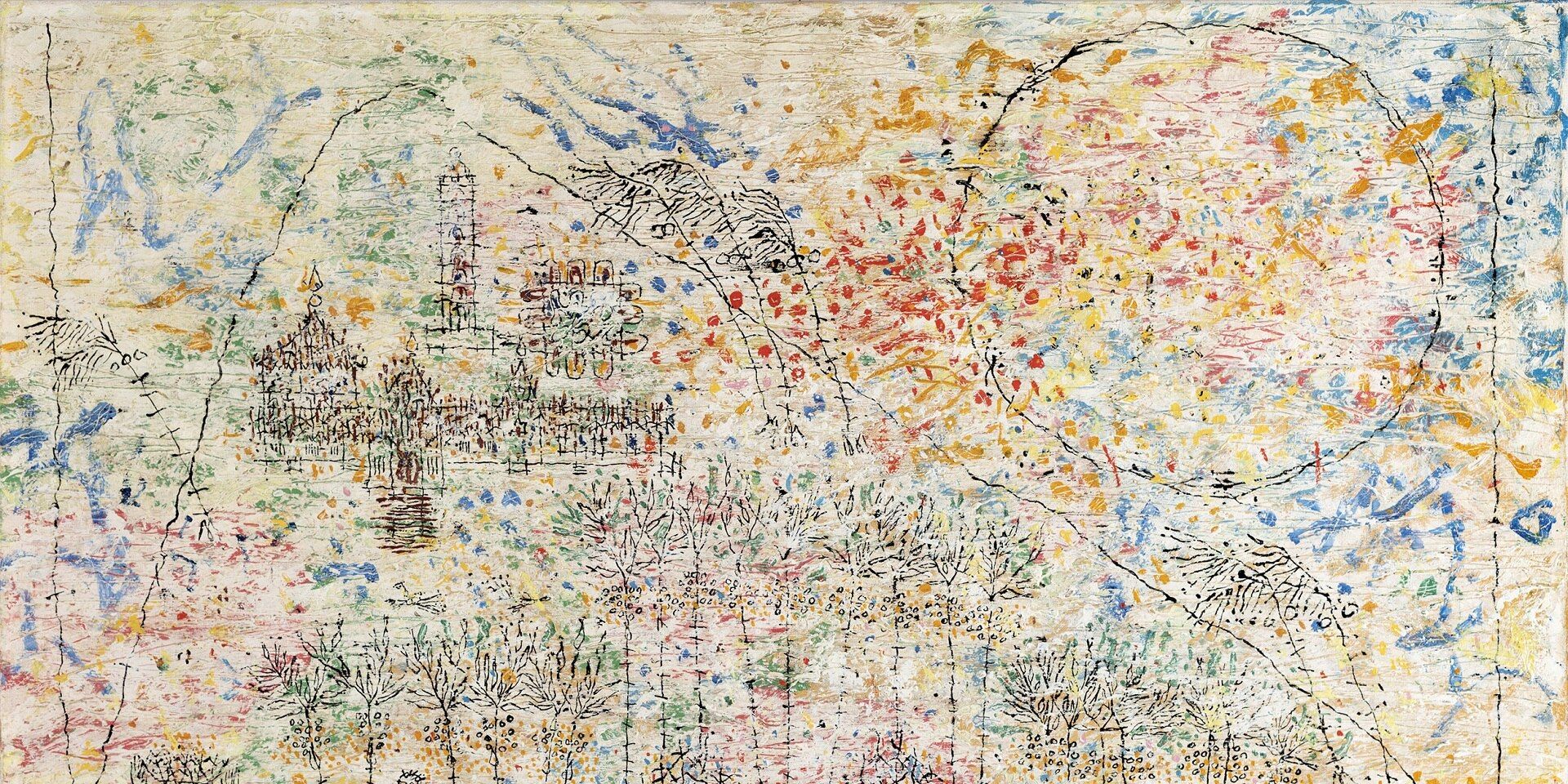

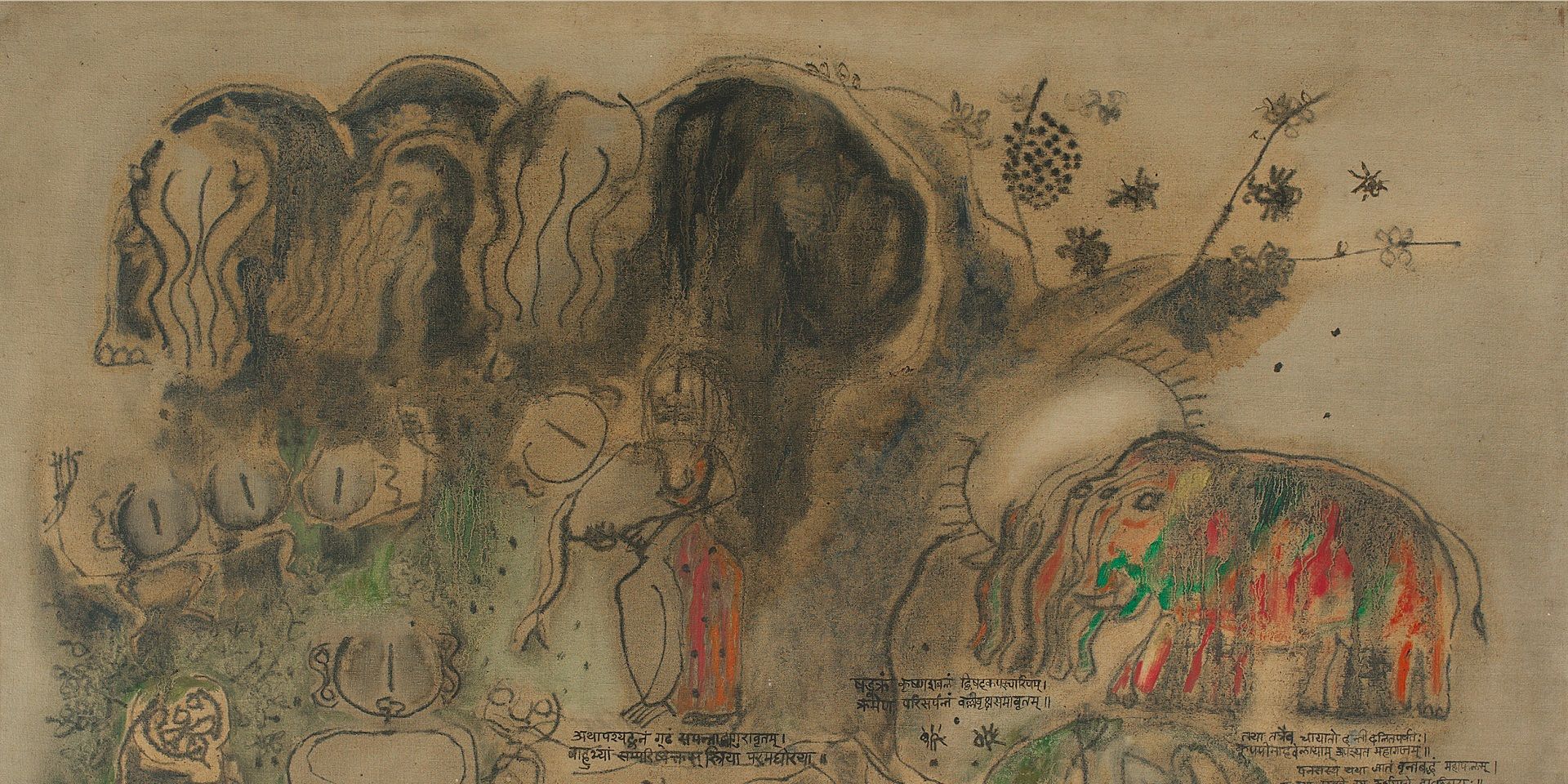

Tyeb Mehta, Untitled (detail), 1966, Oil on canvas, 48.7 x 58.0 in. / 123.7 x 147.3 cm. Collection: DAG

Art writer K. S. Shekhawat takes a close look at Tyeb Mehta’s mid-career masterpiece that signalled an imminent shift of style and vision.

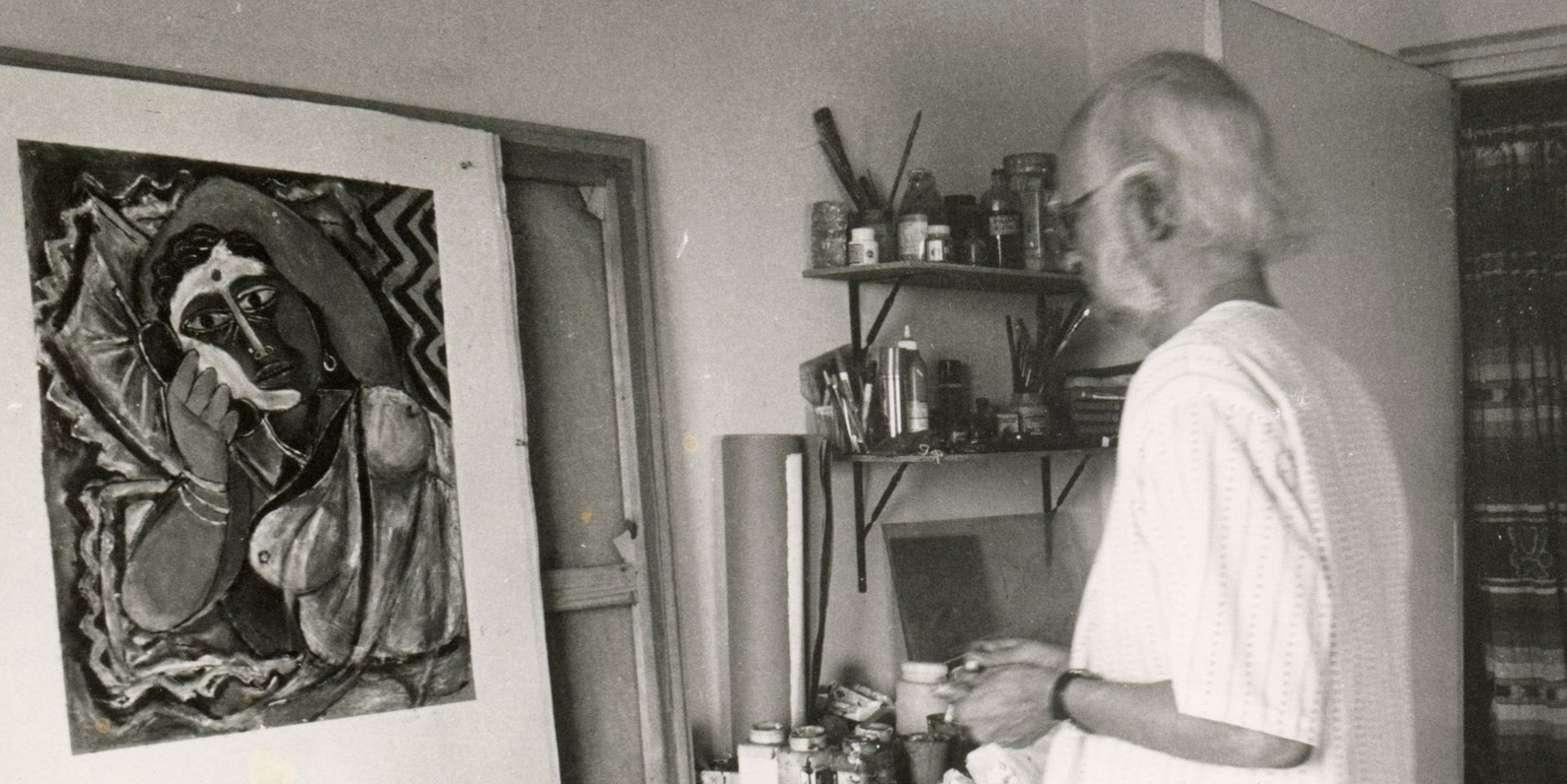

The year is 1966. Tyeb Mehta is showing at the Kumar Gallery in New Delhi, At the opening, Ebrahim Alkazi, who has a deep link with art as well as artists—even though he is a theatrewallah—is giving a talk on Mehta’s work:

‘I believe Tyeb is an extremely difficult painter to understand,’ he says. ‘There is no instant attractiveness in his works, like the neon-lighted distinctiveness with which many artists attract customers. There is no seductive appeal of colour or form or content. On the contrary, like a cunning barbed wire entanglements and barricades, beset with mines and booby traps, and machine-gun nests all carefully camouflaged—a region which only the determined and intrepid beholder would dare to cross.’

Cue to 1989. Another speech, this one by fellow artist J. Swaminathan, in Bhopal on the occasion of Mehta winning the coveted Kalidas Samman, an award instituted by the state government of Madhya Pradesh. On this occasion, Swaminathan acknowledges the transition in the artist’s work that occurred in the late 1960s:

‘The startling change that took place in Tyeb Mehta’s work was a total antithetical turn in his pictorial technique. From the highly agitated expressionistic brushwork, both revealing and enmeshing the tortured human figure, Tyeb, as if in one stroke, decided to annihilate the agitation and reduce pictorial space into becalmed areas of flat colour.

‘His dark sombre palette was banished by the invasion of bright, contrasting colours. The decaying yet live flesh which formed itself into his figures disappeared, yielding place to a strictly unemotional line. From the fluid, intensely human drama of his former period, Tyeb, inexplicably it would seem, had switched over to the still backdrop and jerky figures of the puppet stage.’

Tyeb Mehta, Untitled (detail), 1966, Oil on canvas, 48.7 x 58.0 in. / 123.7 x 147.3 cm. Collection: DAG

Between Alkazi and Swaminathan’s observations is a gap of only a few years in which a catalytic change occurs, something that will define Mehta’s career henceforth—but what causes this? The reason is simple enough. Mehta is awarded the John D. Rockefeller III Fund grant and takes off for New York for a year in 1968. Almost the first place he sets foot on arriving at the Big Apple is the Museum of Modern Art where he encounters his first Barnett Newman, a moment that has a powerful and lasting impact on him:

‘This breakthrough was precipitated by his first encounter with Barnett Newman in the original. As he stood in front of one of Newman’s great walls of intricately worked colour at the Museum of Modern Art, New York—a painting that was not at all simple, uninviting flatness that Indian artists knew from the inadequate black-and-white reproductions of the period—Tyeb formulated a question for himself: How could he articulate his paintings in such a way as to savour the sheerness and radiance of large areas of colour, the sensuous pleasure of colour-as-field, without sacrificing the figure? Tyeb’s paintings, ever since, have taken the form of arguments, solutions and counterpropositions around this theme, in an unfolding process that has thrown up further questions, further investigations. On the face of it, it appears that the breakthrough prompted Tyeb to abandon his earlier emphasis on texture, irregularity and accident, and dedicated himself, instead, to reclaiming perfection, as though a classicist temper were reasserting itself.’

Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The colour-field artists may have nudged Mehta towards a more primary palette and Francis Bacon may have become the default comparison of choice for Mehta’s paintings from this point onwards, but the Untitled work under review is one that preceded this shift and is, therefore, important, for being on the cusp of a cataclysmic change—one of an increasingly rare body of works from that pivot point that saw the culmination of his expressionist, encaustic oil paintings to which he was never again to return.

Mehta himself spoke of that metamorphosis in an interview:

‘My encounter with minimalist art was a revelation. I had seen minimalist reproductions previously, but I hadn’t seen the works in the original. I might have dismissed many of them as gimmicks… just another tricky idea. But when I saw my first original Barnett Newman for example, I had such an incredible emotional response to it. The canvas had no image… but the way the paint had been applied, the way the scale had been worked out… the whole area proportioned. There was something about it which is inexpressible. It emotionally moves you and that is I think that intangible quality we were talking about. It’s a direct relationship you can’t really analyse.’

|

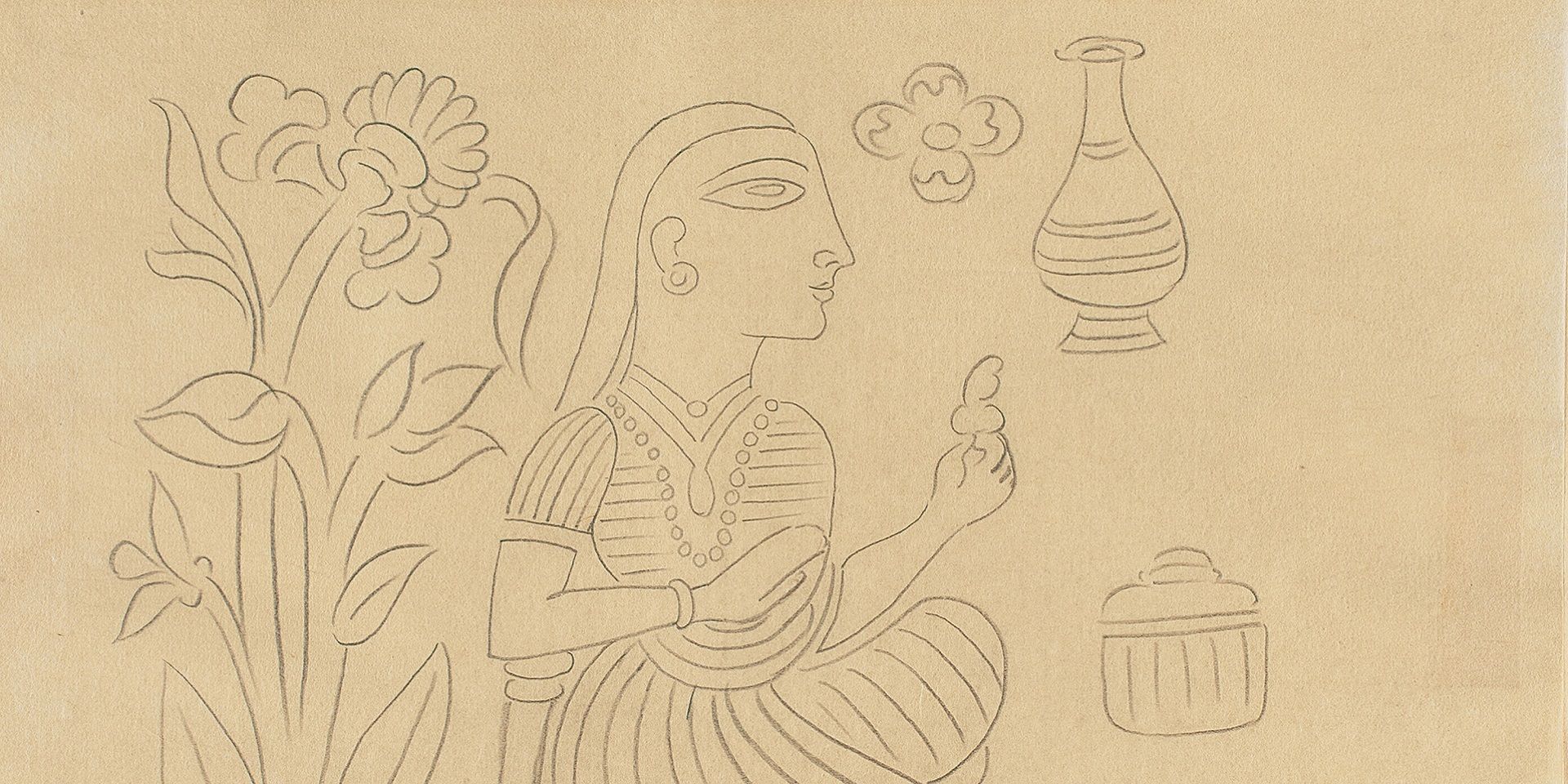

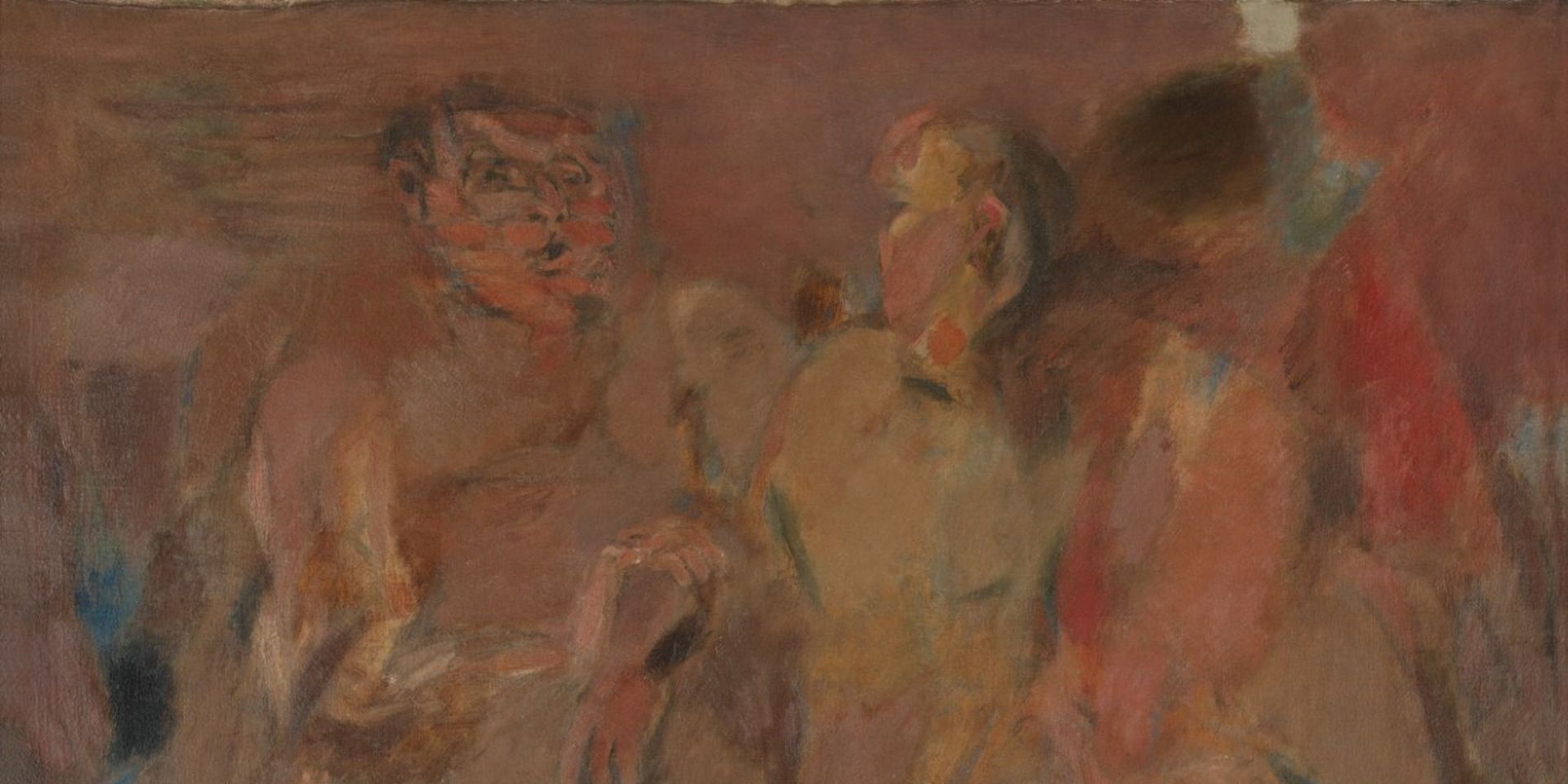

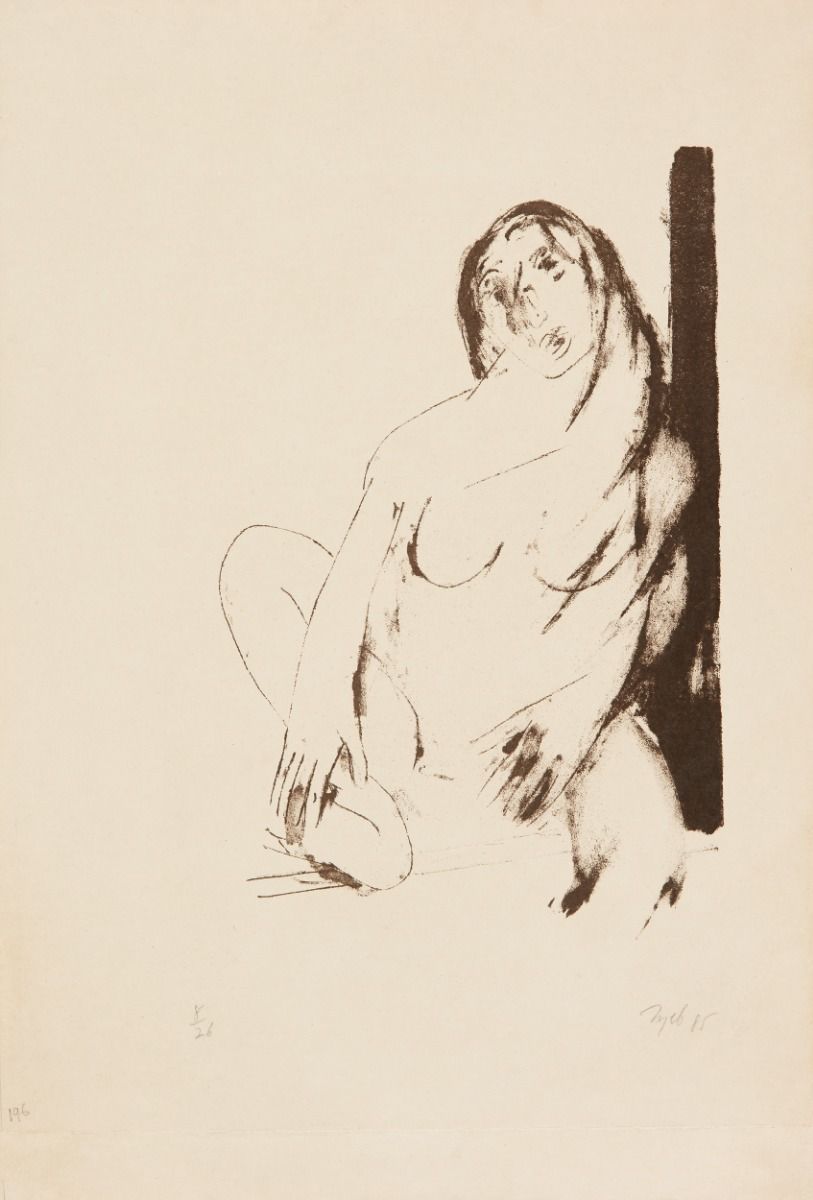

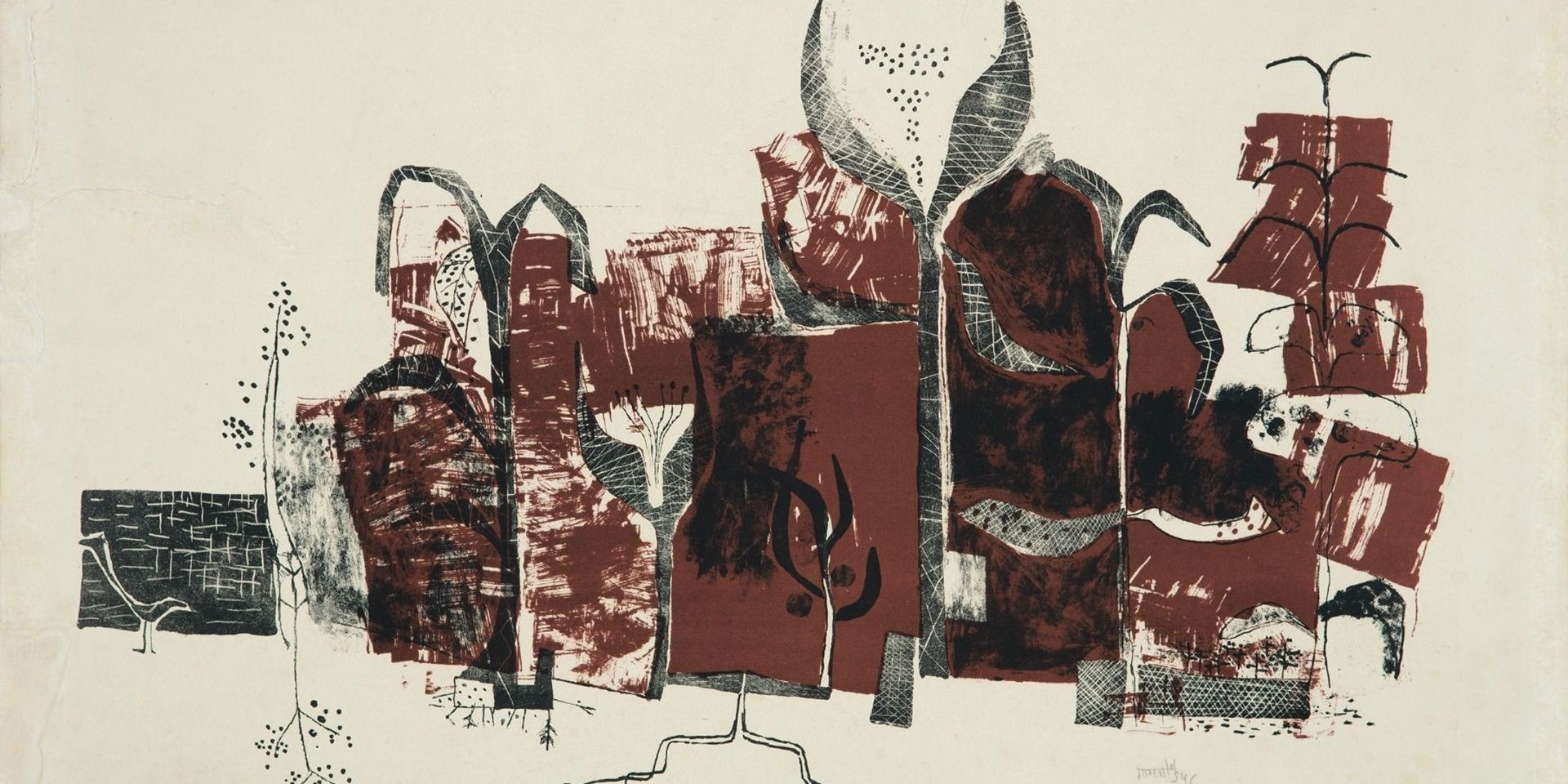

Tyeb Mehta, Untitled, 1985, Lithograph on paper, 13.2 x 8.5 in. Collection: DAG |

This Untitled painting may appear, at first, unexceptional considering how Mehta was painting at the time. There are the indicative, expressionistic brushstrokes in a single colour tone that defines the painting, with darker and lighter hues and the manipulation of black strokes delivering us figures from the fugue, as it were. The figure was central to his practice even if it lacked, in its aloneness or aloofness, any hint of heroism. This was a figure burdened, a precursor to his flat-planed figures that would follow from 1969 onwards when he painted his first Diagonal. In their hazy appearance, it is possible to ascertain, in hindsight, his trussed bulls and falling figures and rickshaw pullers and even the maw of the hauntings that had stayed with him since Partition.

Here, a group sits, three figures foregrounded across the painting (perhaps there are more behind them, their ascertainability difficult to tell in the earthy terrain of the figures placed in proximity like a group of impenetrable rocks). Within the group, there is no sense of camaraderie or bonhomie; these are strangers brought together through an act of individual or social tragedy. They sit together yet apart before what might be a bonfire over which one figure appears to warm its hands. An emotional anguish suffuses the painting—something in common with Mehta’s works from this period—even though there is no obvious handwringing or pathos whether in the figuration or the artist’s choice of colour. There is something primal about the group where a collective sanctuary is not without suspicion of the other.

Tyeb Mehta, Untitled, 1966, Oil on canvas, 48.7 x 58.0 in. / 123.7 x 147.3 cm. Collection: DAG

After a stay in London of five years, where he had caught the eyes of the art critic George Butcher, Mehta returned to Bombay in 1964, relocating the following year to New Delhi where he completed this Untitled painting. He could hardly have anticipated at the time the threshold of change before which he stood, an upheaval so complete it would overtake his previous career and leave it behind in the shade—only to be re-discovered decades later as a marker of an artist’s journey that began and matured in a language that he abandoned to embrace another. It is time, now, to reclaim that first language of his pictorial journey.

In 1966, the art critic of The Times of India wrote about Mehta’s exhibition at Kumar Art Gallery:

‘In Tyeb Mehta’s paintings the figure exists as a palpable presence in its own right, as paint and as a significant form emerging from the composition. It provides a focus and suggests a field of experience. […] Within reason and good taste he keeps touch with both the worlds—the figurative and the abstract.’

It is tempting to think that this painting might have been in that exhibition; it is even more exciting to imagine that the critic was talking about this work. Perhaps he was.

related articles

Essays on Art

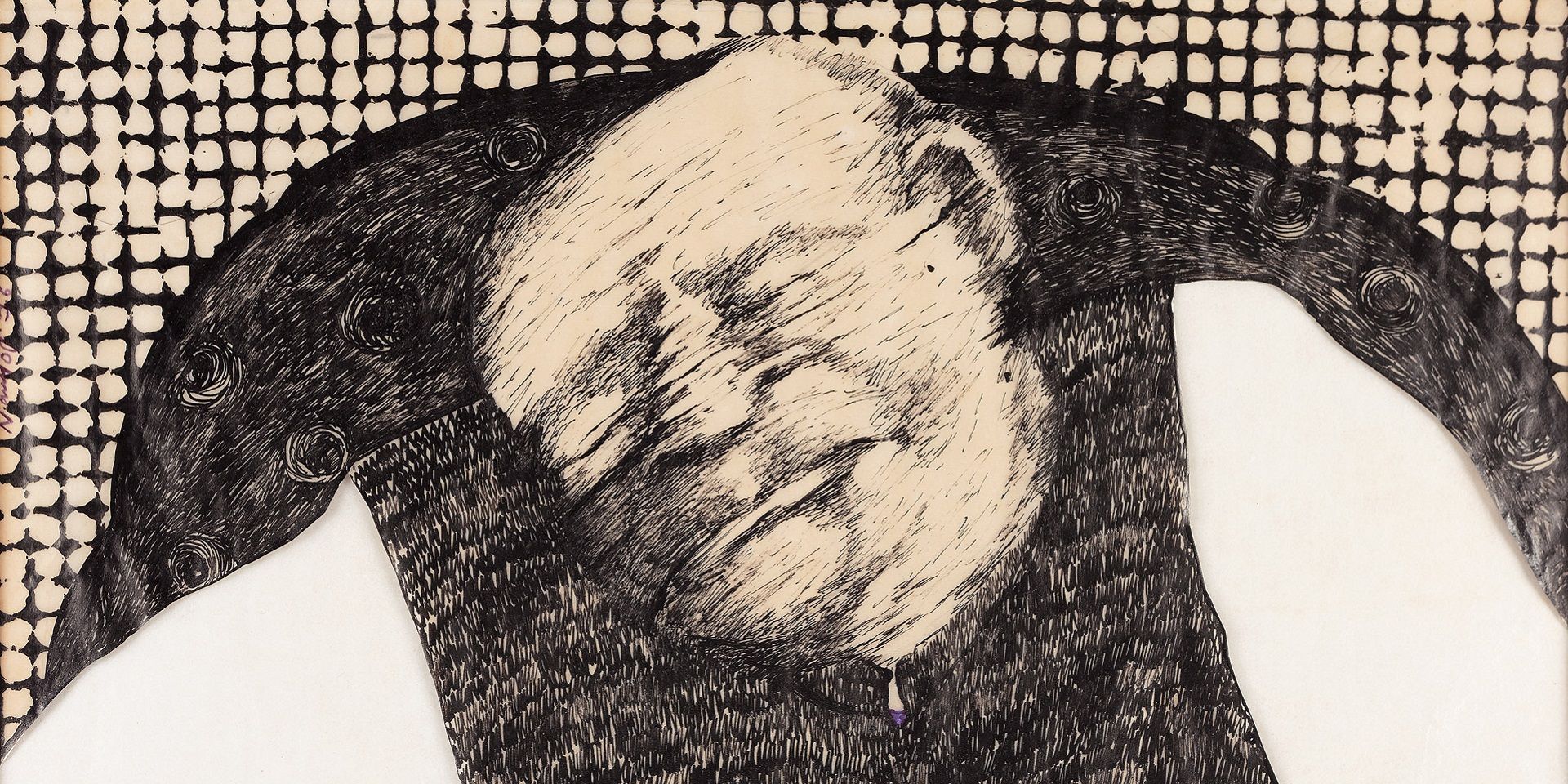

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

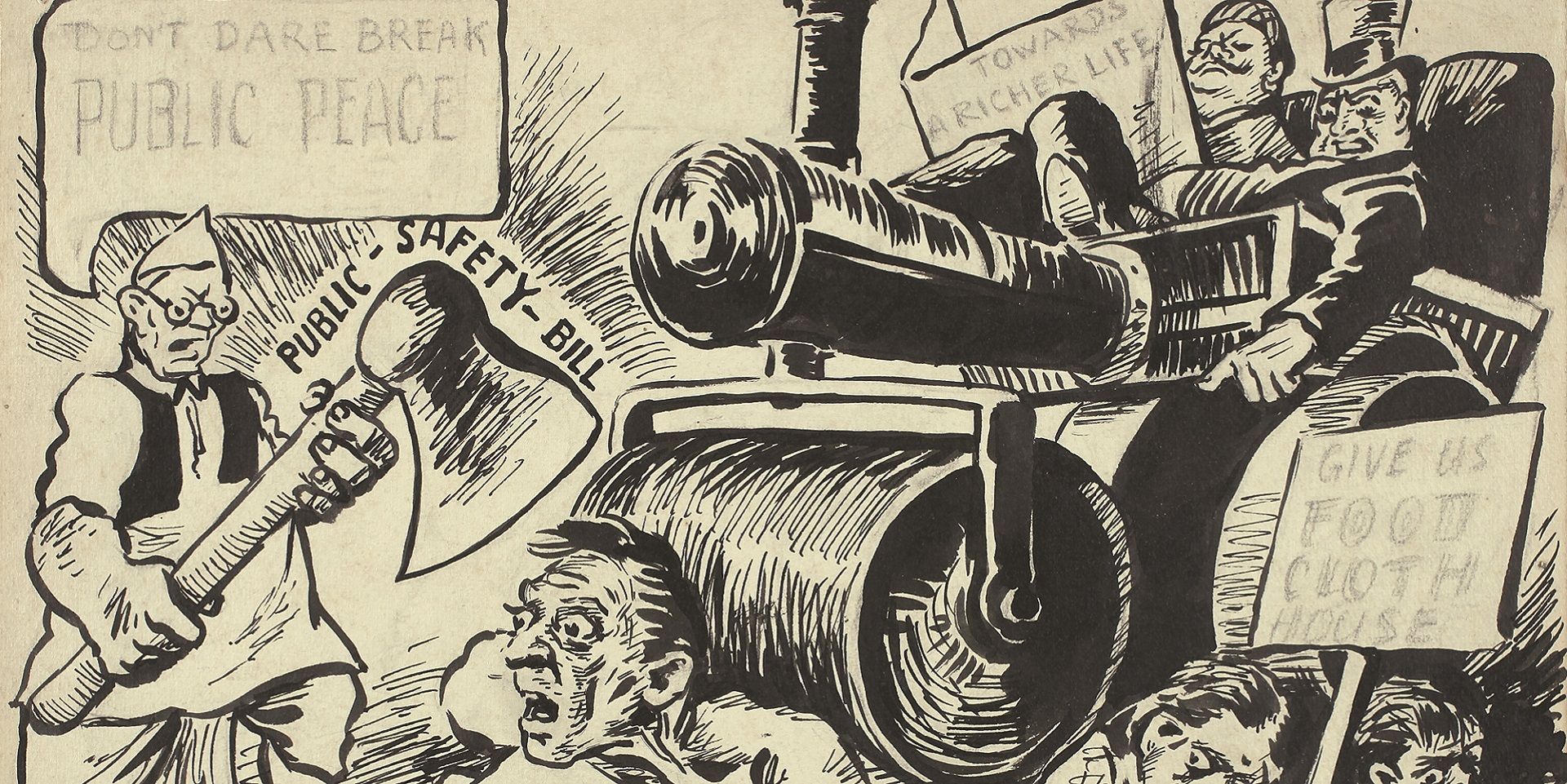

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

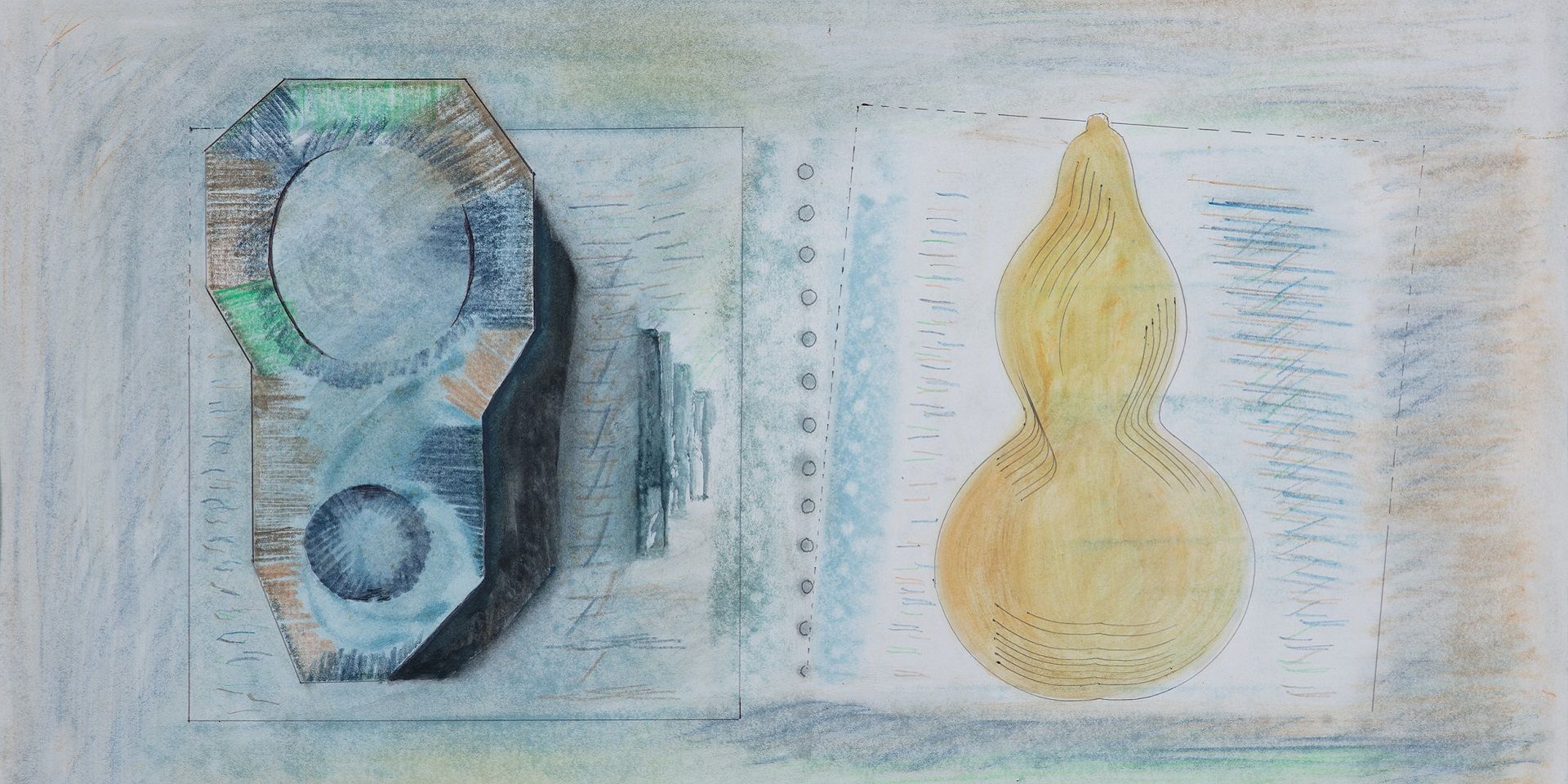

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

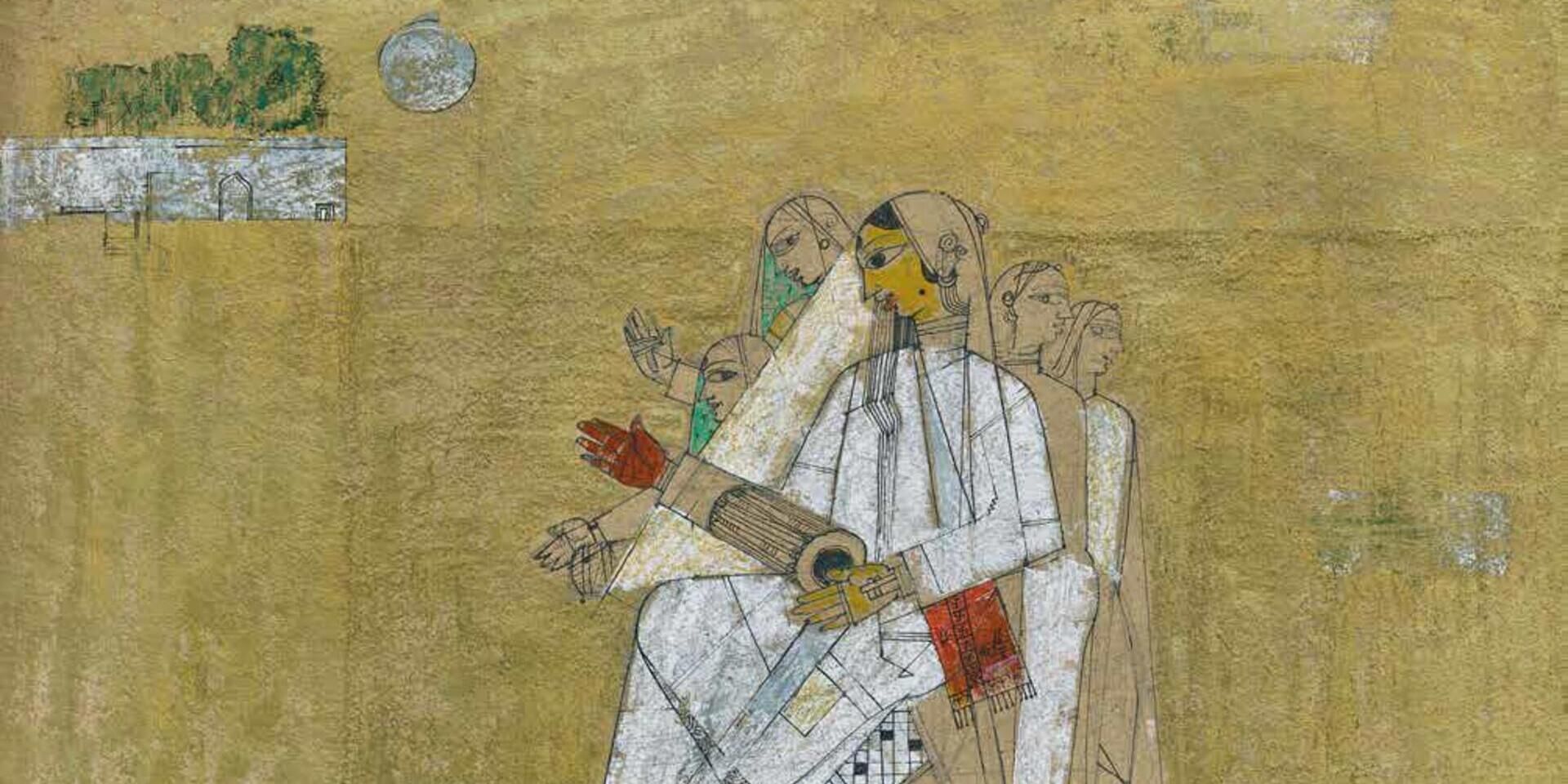

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

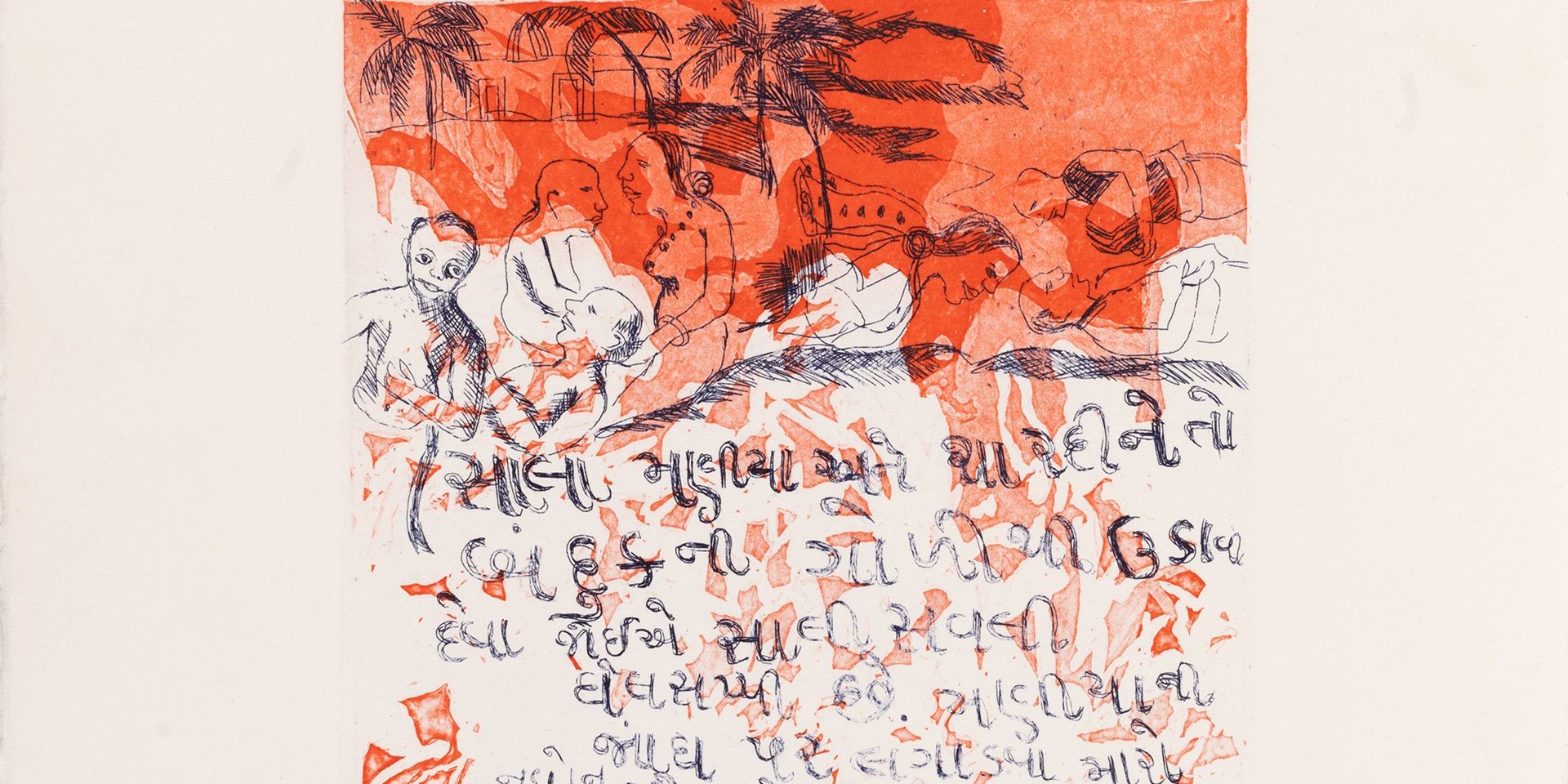

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024