Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

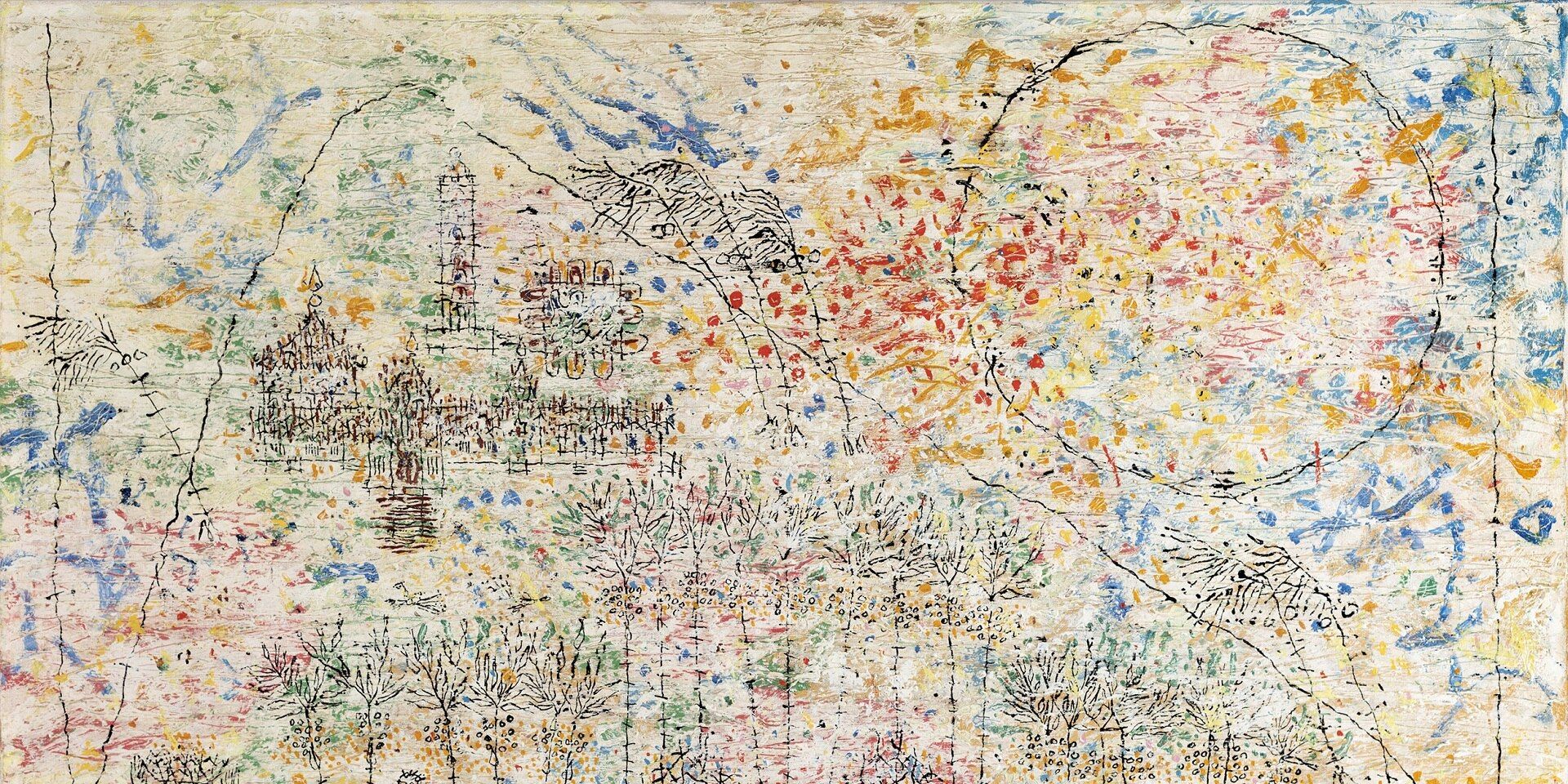

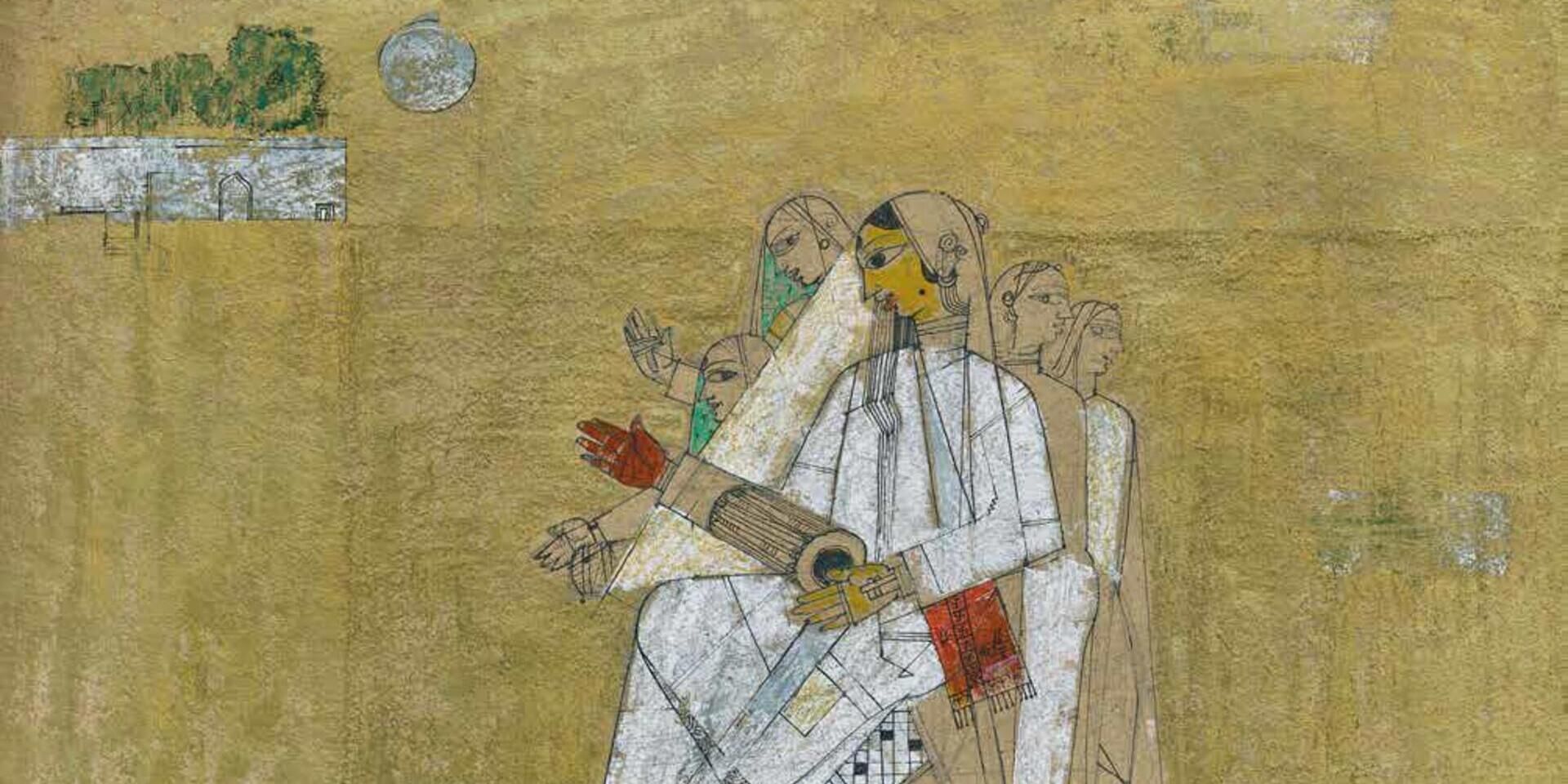

Avinash Chandra, Moon and Houses (detail), 1960, Oil on Masonite board, 36.0 x 60.0 in. Collection: DAG

In October of 1978, the artist and critic Rasheed Araeen wrote to Andrew Dempsey of the Arts Council of Great Britain proposing a survey exhibition of the works of Black artists in Britain [1]. Dempsey wrote back in May 1979 with the disappointing news that the exhibitions committee had rejected the proposal citing as their reason that the artists mentioned by Araeen in his proposal were not lacking in exposure and the ‘more sensible thing would be to broaden the scope to include all foreign artists living and working in the country’.

However, there was no interest in taking that further either. Despite the initial rejection, and general resistance in the London art world to such an endeavour, Araeen’s proposal ultimately took the form of a landmark exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1989. The exhibition included works by twenty-four Afro-Asian artists in Britain—amongst them Francis Newton Souza and Avinash Chandra.

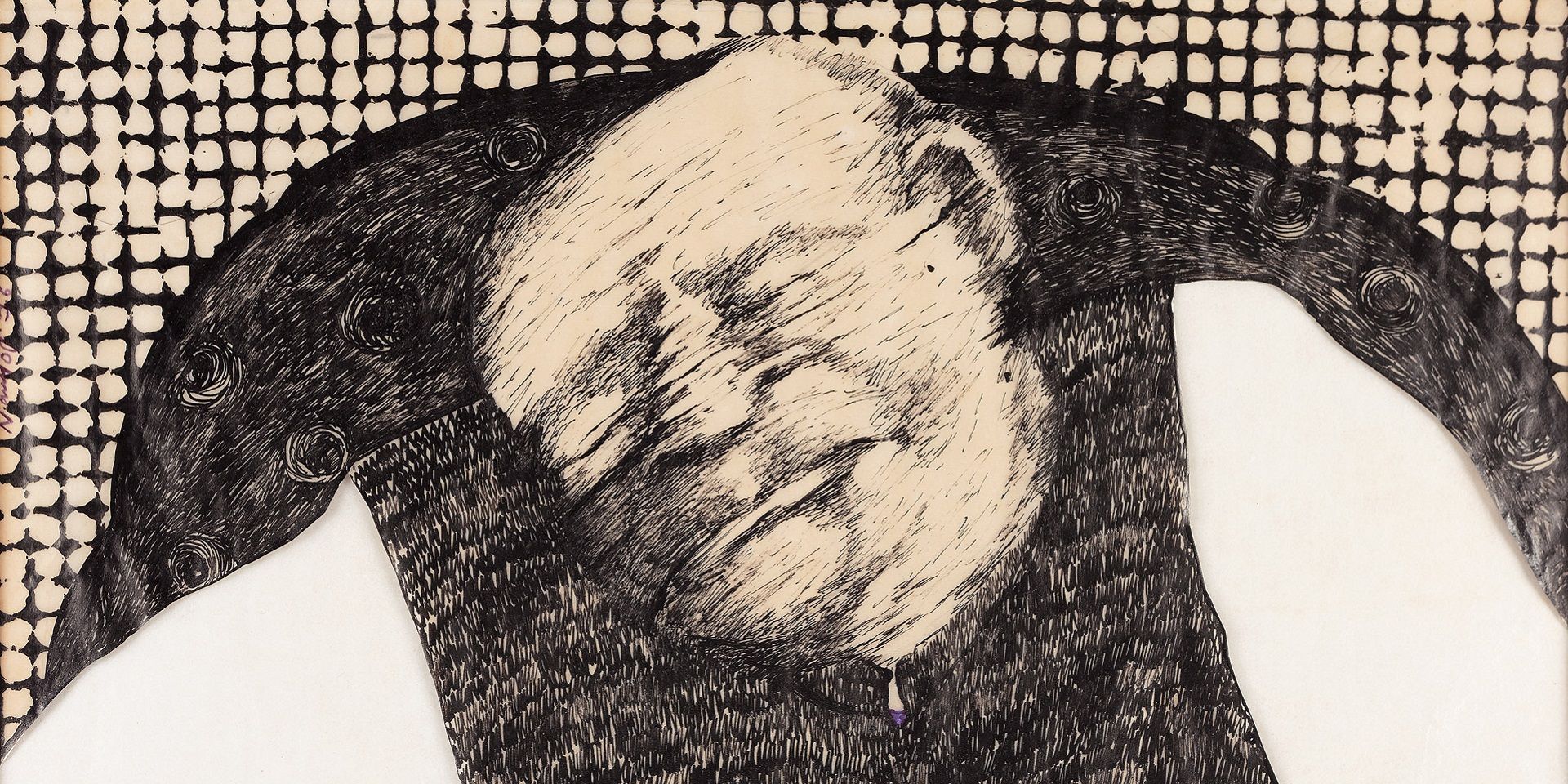

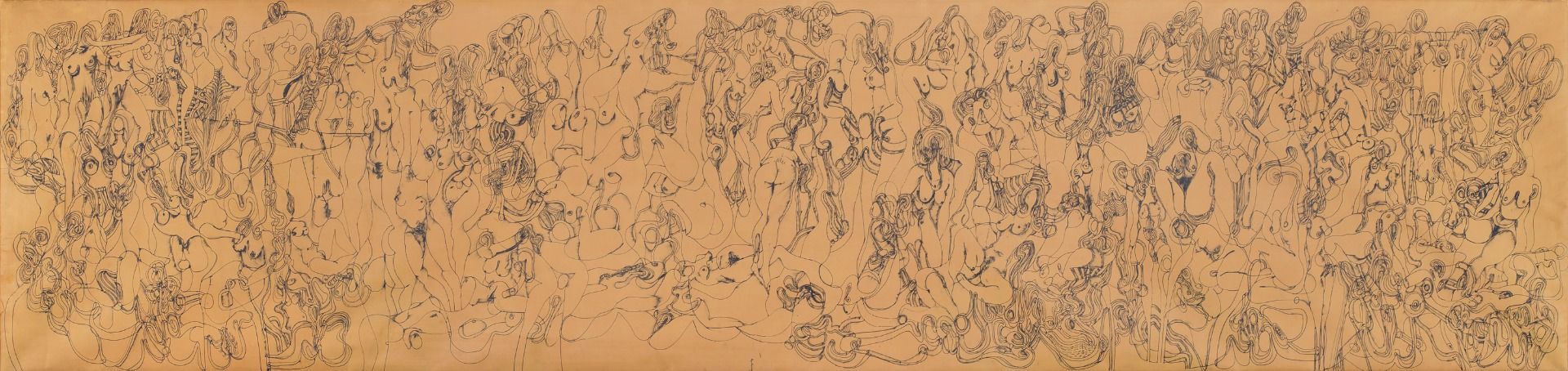

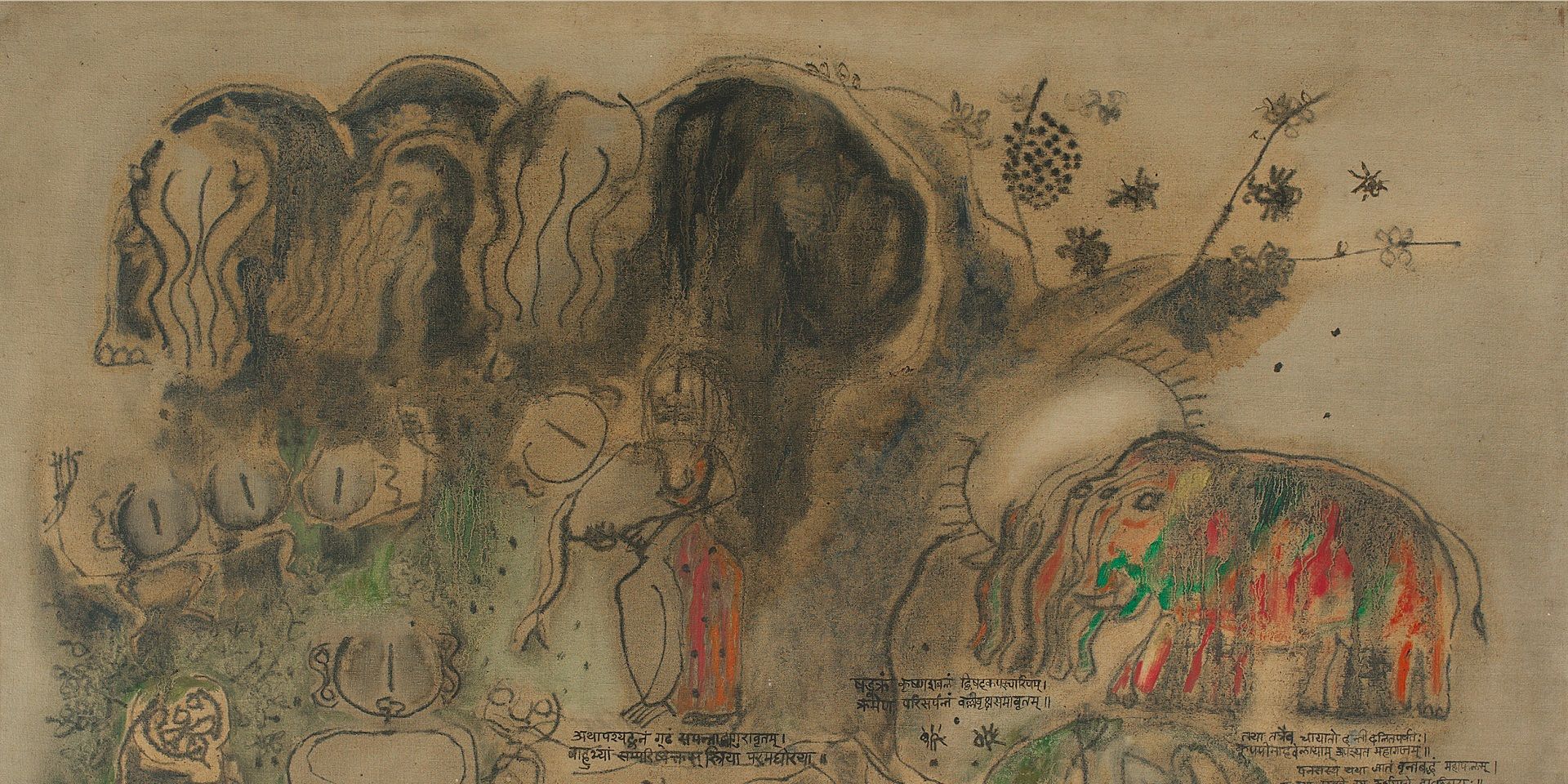

Avinash Chandra, Untitled, 1960, Ink on paper pasted on fabric, 40.2 × 169.2 in. Collection: DAG

The Arts Council’s reasoning for rejection, although quite absurd in ways Araeen himself pointed out in his next reply to Dempsey, seems not entirely out of place in the first half of its claim regarding exposure, especially in the case of Souza and Chandra.

F. N. Souza had moved to London in 1949 and attended Central School of Art. Struggling in penury in the initial years after his move, Souza was close to starvation when in 1955, Gallery One by Victor Musgrave hosted the first of many solo shows by Souza which marked a turn in his career. Steadily gaining fame, one might even say notoriety, Souza’s works piqued as much interest as his well-crafted unabashed persona of crude genius in London art circles. Avinash Chandra, who moved to London in 1956 had his first solo show at the Molton Gallery in London followed by spin-off shows at the Galerie de l’Université in Paris and the Galerie Katerina in Amsterdam in 1961, a show at the Bear Lane Gallery, Oxford in 1960 and again in 1964. As Giles Tillotson, in his essay in the book for DAG’s recent exhibition ‘Contours of Identity: F. N. Souza and Avinash Chandra’ notes, all of these exhibitions were received well.

|

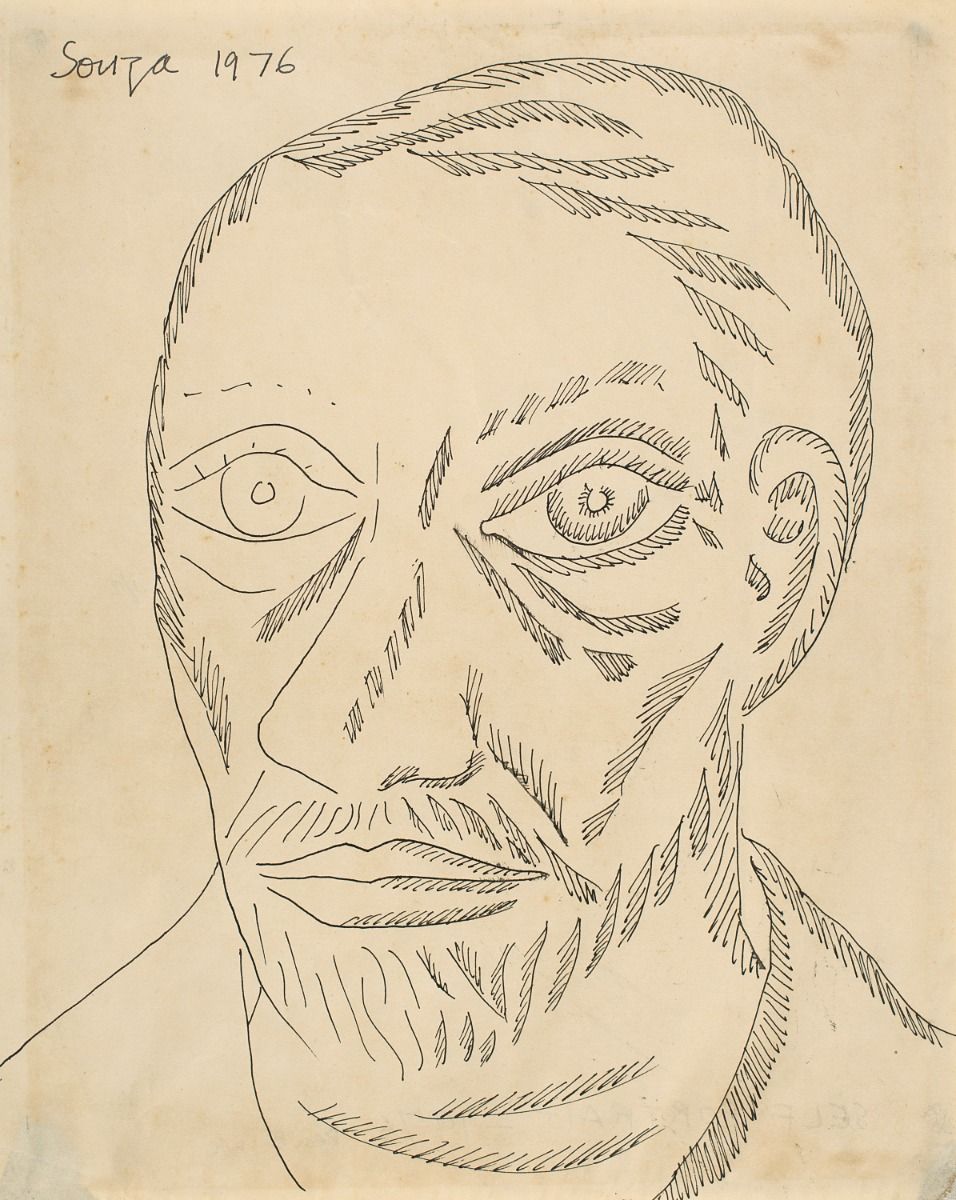

F. N. Souza, Self-Portrait, 1976, Ink on paper, 11.0 × 8.5 in. Collection: DAG |

In 1965 Avinash Chandra became the first Indian British artist to be showcased at the Tate. Facilitated by the keeper of Indian art at the V&A, W. G Archer, the Tate also hosted an exhibition of Souza’s works. Reviewing the exhibition catalogue titled, Indian Painting Now, at the Commonwealth Institute of London curated by Archer and organised by the Arts Council, for Studio Magazine, critic George Butcher proclaimed Souza and Chandra to be the two most important painters of Indian origin then in London. In fact, Araeen himself, in the accompanying book to The Other Story, acknowledges the amazing support and response enjoyed by Afro-Asian artists in these periods of success and specifically mentions Souza and Chandra who had become ‘so phenomenal by the early 60s that there must have been many English artists envious of their success’. The issue that we contend with then, in terms of the Arts Council’s rejection of Araeen’s proposal on the grounds that these artists did not lack exposure, is a definitional one. The well-received exhibitions and critical acclaim conferred upon both these artists affirm that their work enjoyed a certain level of exposure, but it bears asking: what kind? What also requires investigation in retrospect is the discursive impact, if any, of this exposure in art historical terms. These, I would argue, are central to Araeen’s purpose in curating The Other Story. It is not a project that merely sought to bring to the limelight, rescued from the shadows of obsolescence or ignorance, Afro-Asian artists in Britain, but rather, to interrogate the nature of the art historical narrative that continually affirmed the centrality of the Western/white artist in the paradigm of modernism in an attempt to inscribe the ‘other’ stories within this master narrative.

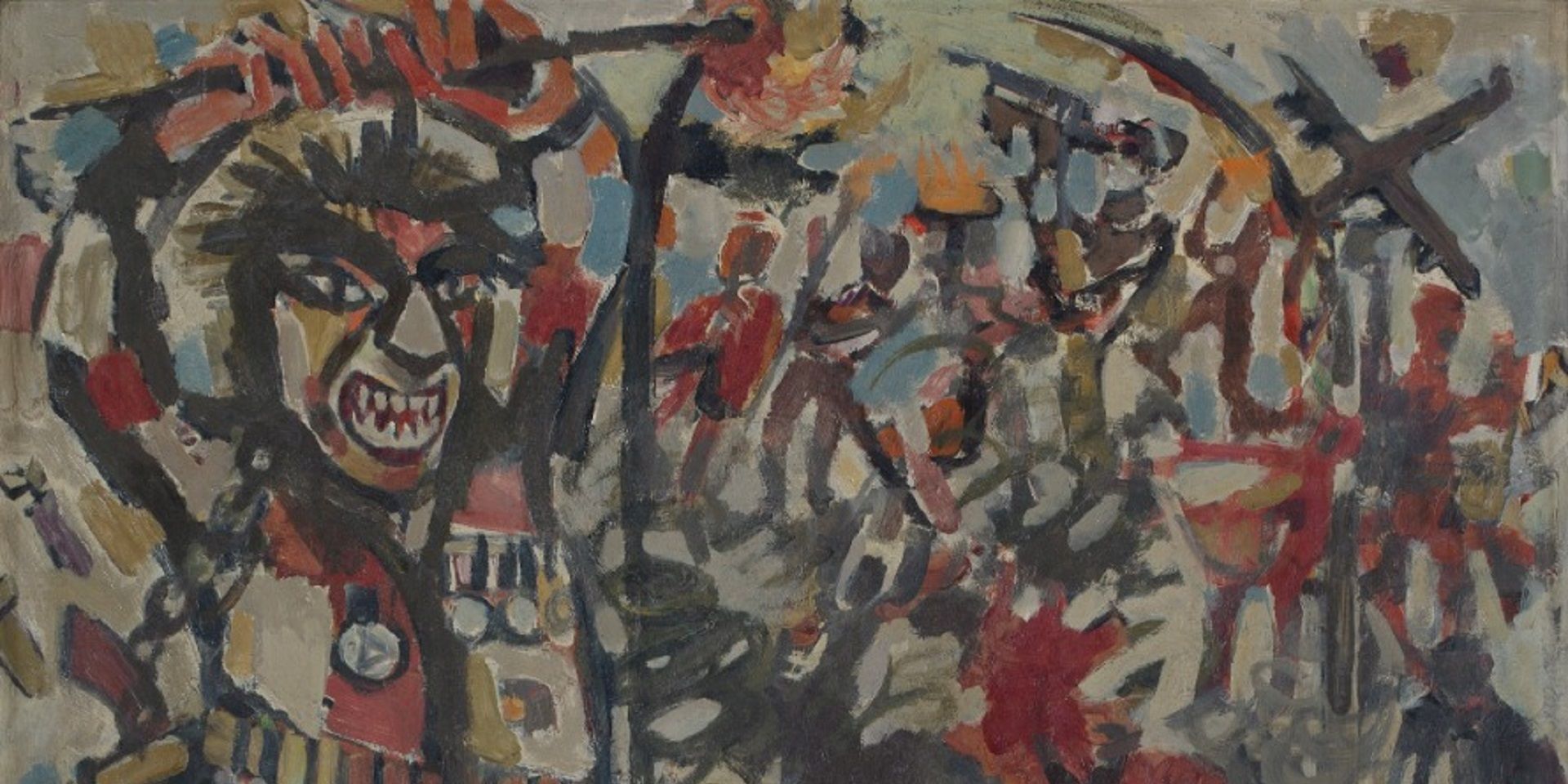

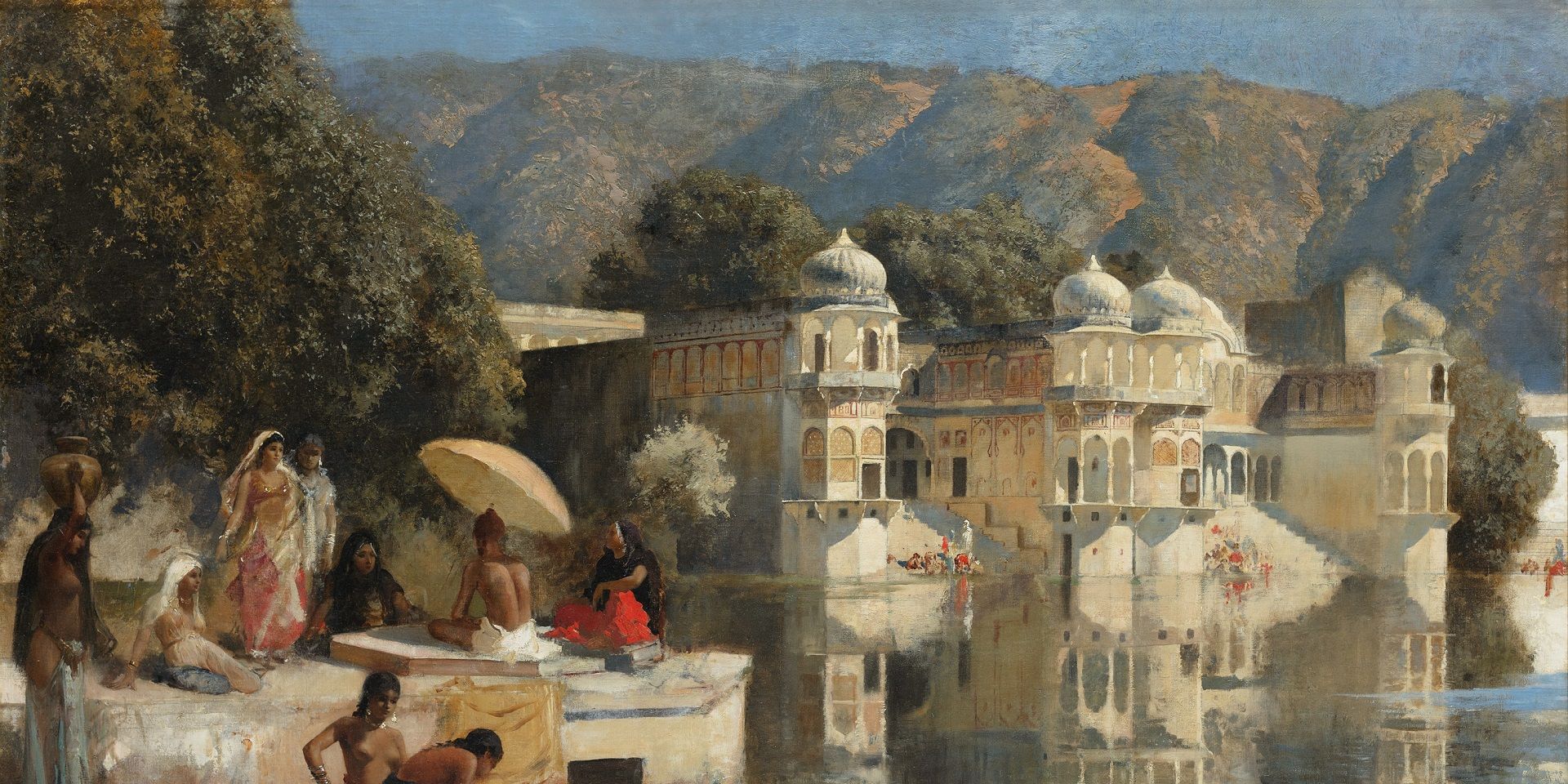

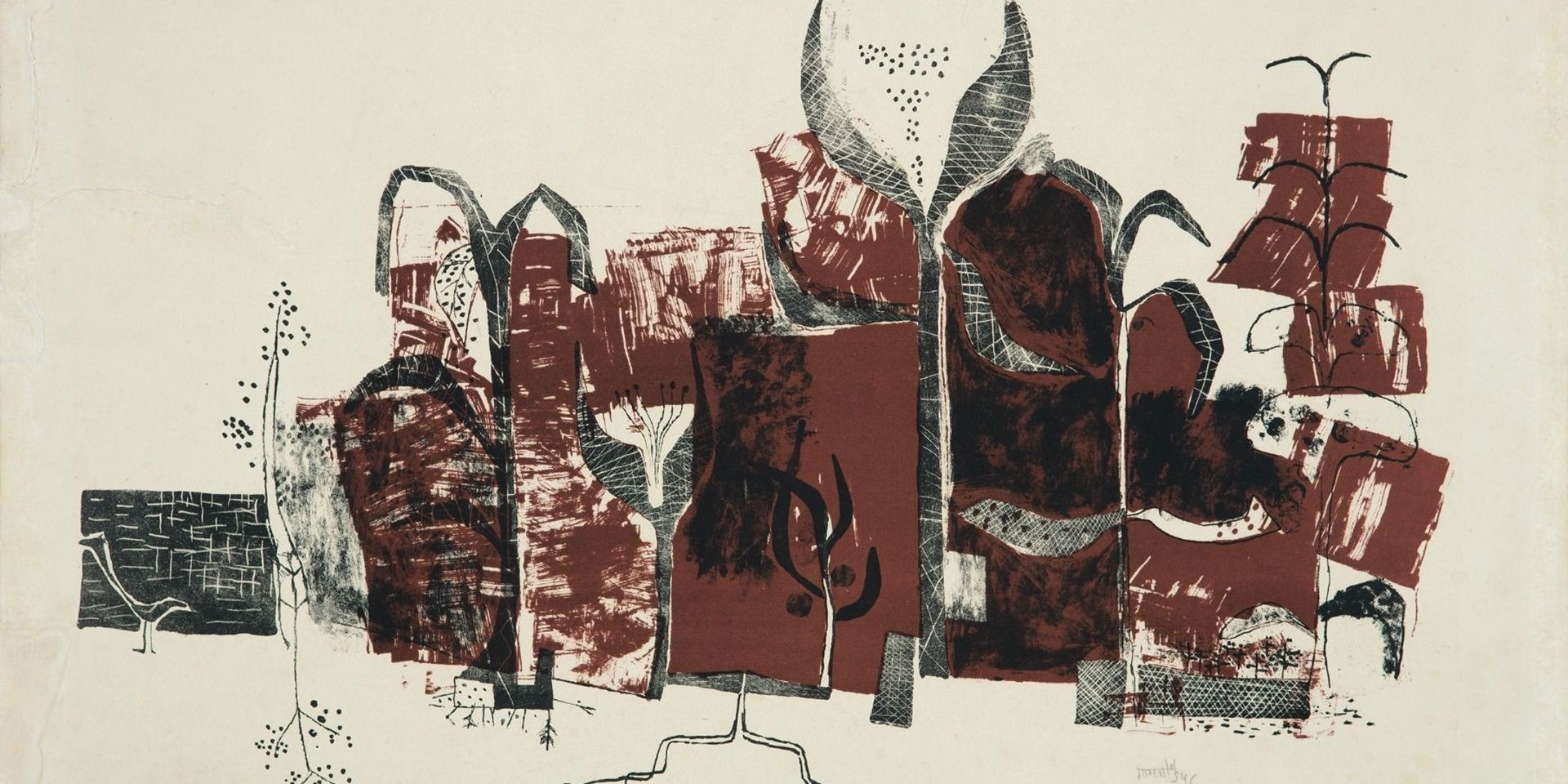

Avinash Chandra, Untitled, 1963, Oil on canvas, 40.0 × 113.5 in. Collection: DAG

In his response to Dempsey's letter, Araeen directly addresses the issue of exposure with sharp clarity. He argues that, within the context of artistic recognition, it is an absurd notion. Even if the work of these artists is already known, he questions what justifies denying them further exposure or institutional recognition. For even in the ‘acclaim’ they received in the 50s and 60s, the ‘Otherness’ of these artists was constantly evoked. Araeen points to headlines such as ‘Oriental Week’, ‘Indian Vision’ etc. which were common discourses around the works of these artists. And, of course, there is the notorious incident of Avinash Chandra being asked if he could paint tigers and elephants by a London gallery owner upon the latter realising that Chandra is Indian.

|

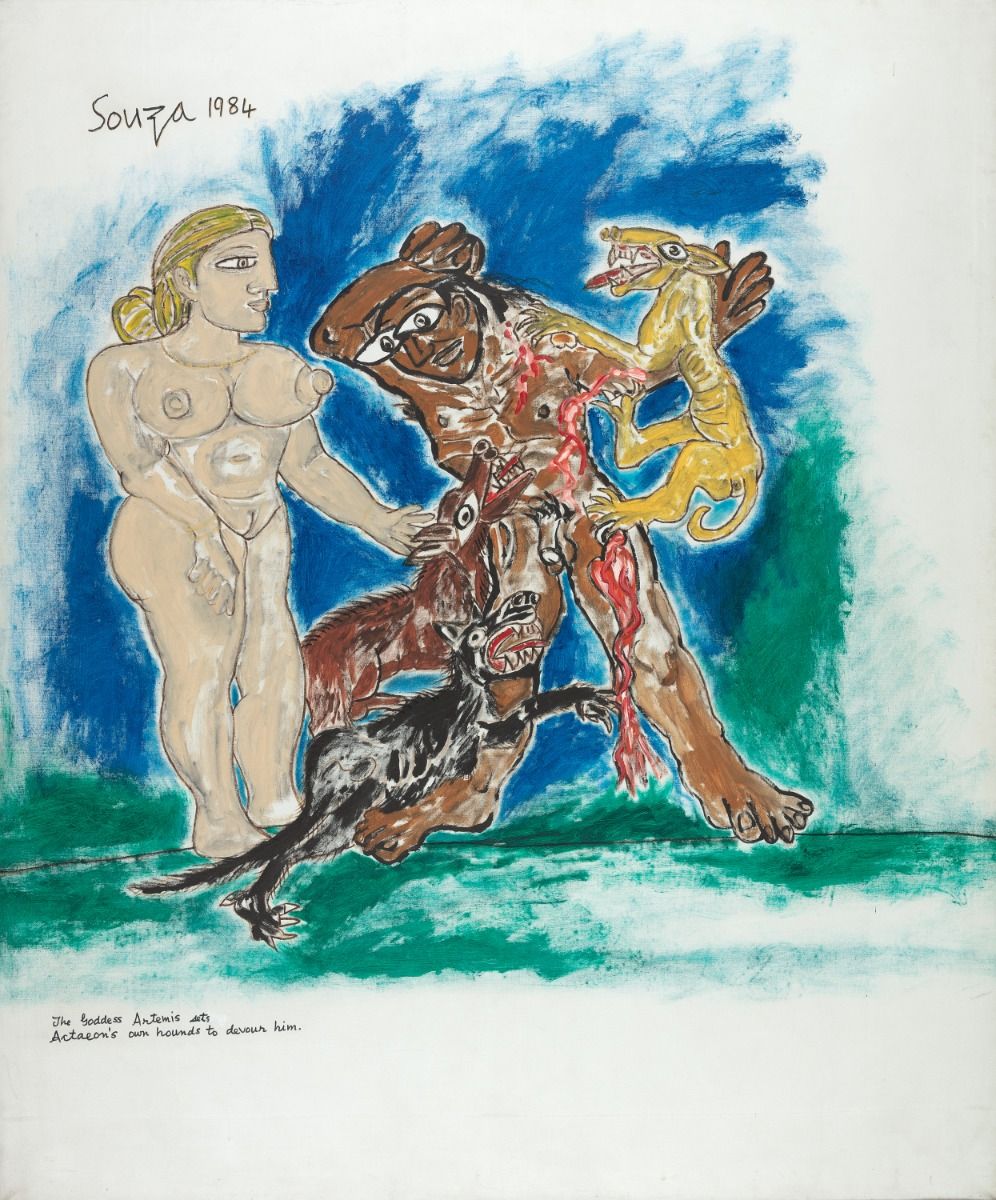

F. N. Souza, The Goddess Artemis Sets Actaeon's Own Hounds to Devour Him, 1984, Acrylic on canvas, 68.7 × 56.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Araeen also highlights that acclaim does not necessarily translate to an intervention into the art-historical canon since the success of these artists, he claims, was short-lived. Even in 1962, arguably within the heyday of their success, Norbert Lynton points out that survey books such as Art Since 1945 which purported to present an international picture of the art scene failed to recognise the contributions of artists not ‘originally’ from Europe and America. Jean Fisher, in her paper on The Other Story, strikingly remarks upon the lingering ‘malodorous trace of this privileged Western canon’ even in more recent art historical texts. It is in this context that Araeen’s framing of the works of these twenty-four artists should be considered—as an attempt to construct what Fisher has called a ‘cultural and archival counter-memory'.

Souza and Chandra’s works were prominently featured in the first section of the exhibition titled ‘The Citadel of Modernism’. Identity and the post-colonial subject in Britain remain a crucial framework for Araeen, who explored, through close analysis of the works of both Souza and Chandra, how their upbringing, training, ‘Indianness’, and experiences in Britain interacted, and sometimes came into conflict with their artistic practices.

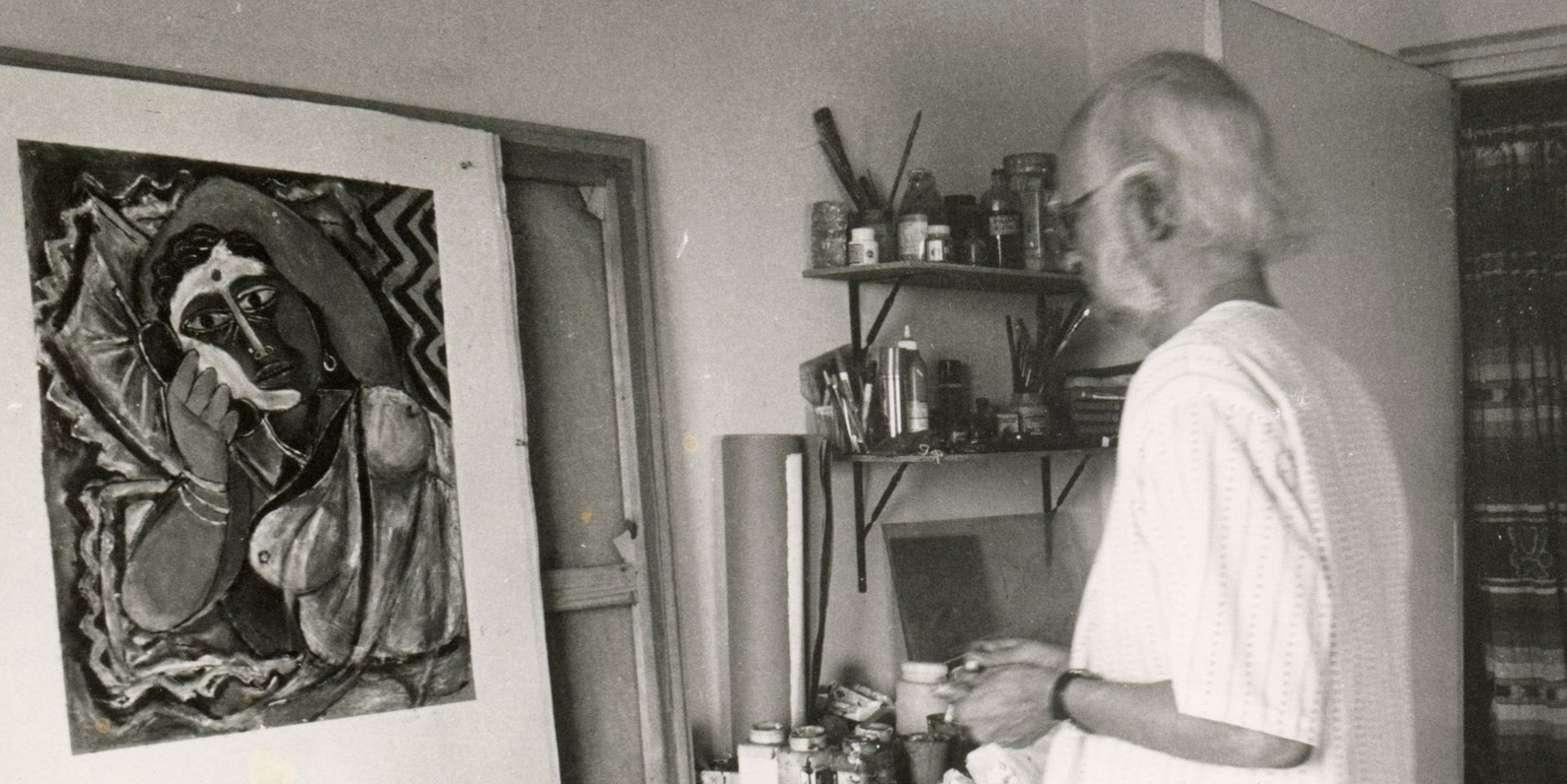

F. N. Souza and Avinash Chandra, The Other Story, Exhibition Documentation, Courtesy: Rasheed Araeen, Asia Art Archive

Araeen begins the exploration of Souza’s work by addressing sexuality but contextualising the eroticism of his work in the field of the artist’s psyche and cultural upbringing. He sees the erotic and the overtly sexual in his work as tied to conflict and paradox intrinsic to Souza’s practice. In his sharp broken lines, distortions, aggressive brushstrokes, jagged and rough forms, Araeen reads the conflict within his upbringing as a Catholic, his experience as a postcolonial subject in Britain, the conflict between sin and sensuality, his disgust and longing, escapism and catharsis: ‘The surface of canvas thus becomes a battleground on which are fought the fear and passions.’ He concluded by refusing to concern himself with the archetype of the ‘genius’ in modernism but nonetheless firmly situated him within modernist discourse: ‘For me it is not important whether he is a genius or not. But he is one of the most important artists of the post-war period, for whom the anxiety of the time was part of a personal anguish, and he articulated this forcefully and expressed it through a highly personal style.’

Avinash Chandra, The Other Story, Exhibition Documentation, Courtesy: Rasheed Araeen, Asia Art Archive

Araeen recognises that the erotic plays a role in the success of Avinash Chandra’s work as well. He quotes analyses which draw parallels between Chandra’s works and the eroticism of traditional Indian sculpture. However, he claims that what he is concerned with is not the supposed obsession of sexuality in the case of either artist but rather the way they responded to their presumed positions in British culture. In Chandra’s works, the dispersed and fragmented bodies, rather than being sexually positive and regenerative in its energy, to Araeen become a Jungian metaphor where ‘confronting the ‘imperial masculinity’ of the dominant culture, the ‘feminized body’ inverts itself, wearing a paradoxical mask, and explodes into parts which are thus separated from the ‘real’ self and dispersed.’

|

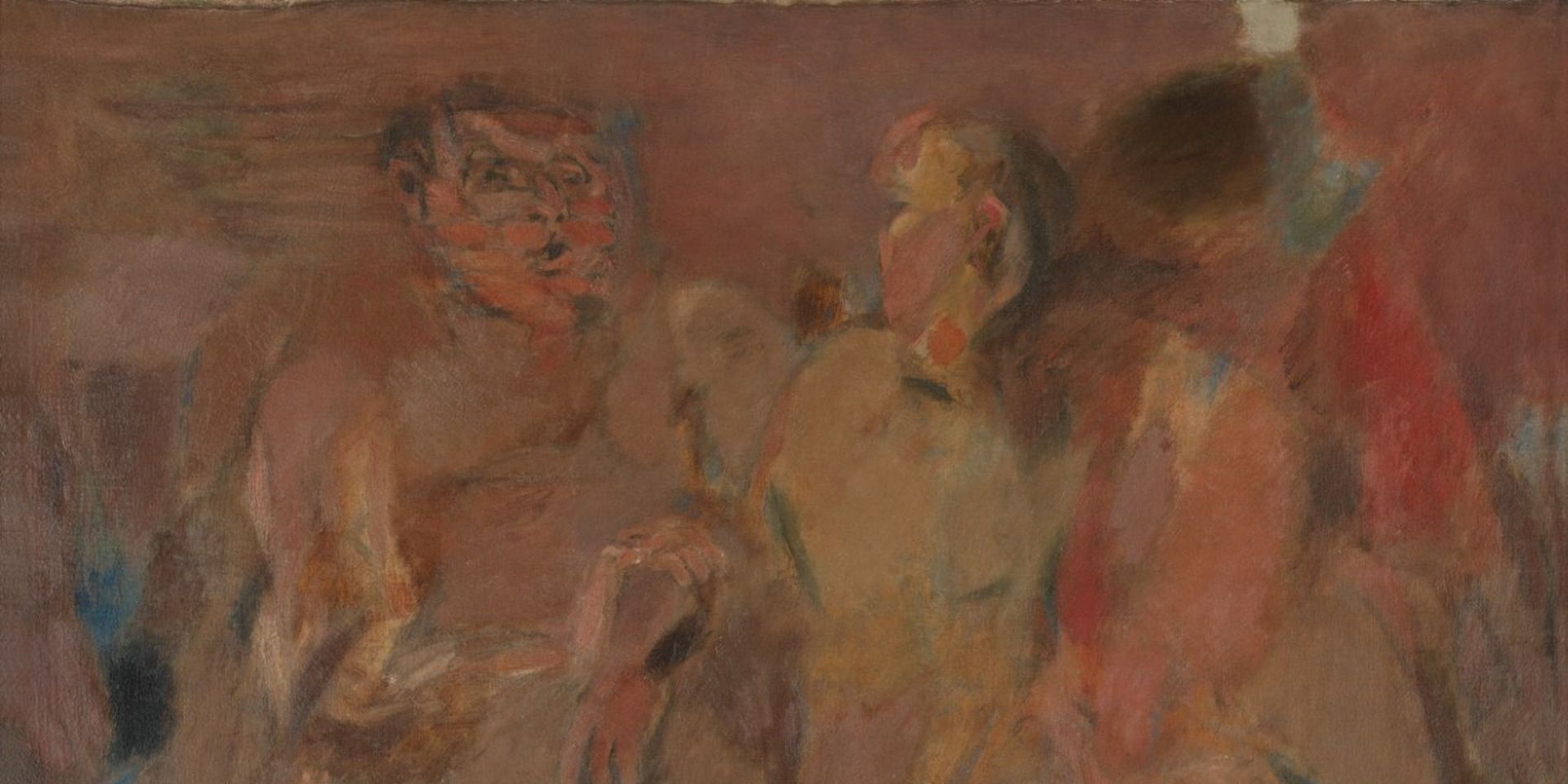

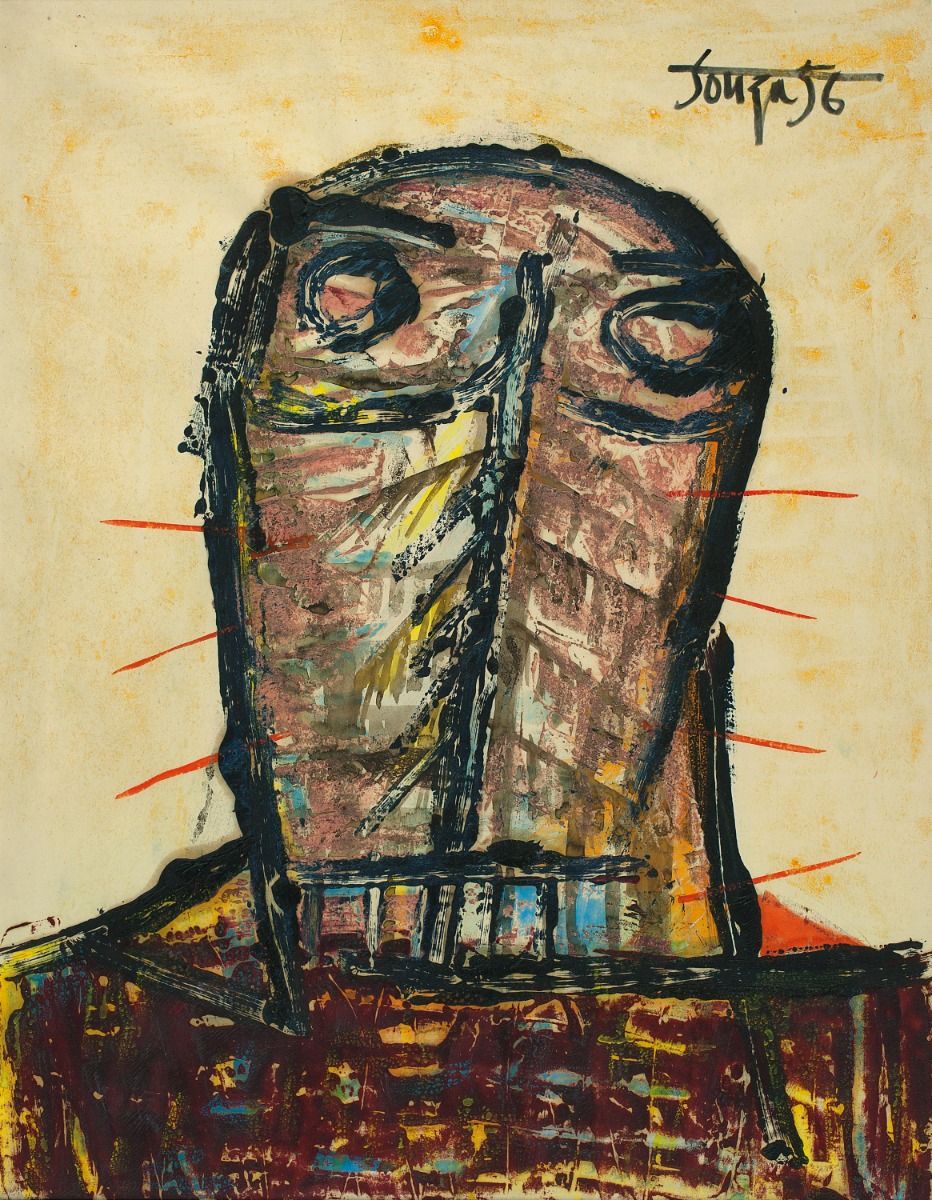

F. N. Souza, Untitled, 1956, Oil on paper, 26.7 × 21.0 in. Collection: DAG |

In the introduction to the catalogue, Araeen asks (about Afro-Asian artists such as Souza and Chandra popular in the 50s and 60s): ‘Why did none of them manage to enter history?’. Yet, more than three decades on we are, this year, celebrating Souza’s centenary with exhibitions of his works happening globally. New art historical research, not just about Souza, but the cultural milieu he worked in is being generated. One could, with some confidence, proclaim that endeavours like The Other Story, which are of course not without their due criticisms (not within the purview of this essay but discussed amply elsewhere) have succeeded in inscribing a counter-memory within the annals of modernist discourse where Souza and Chandra’s names are indelible.

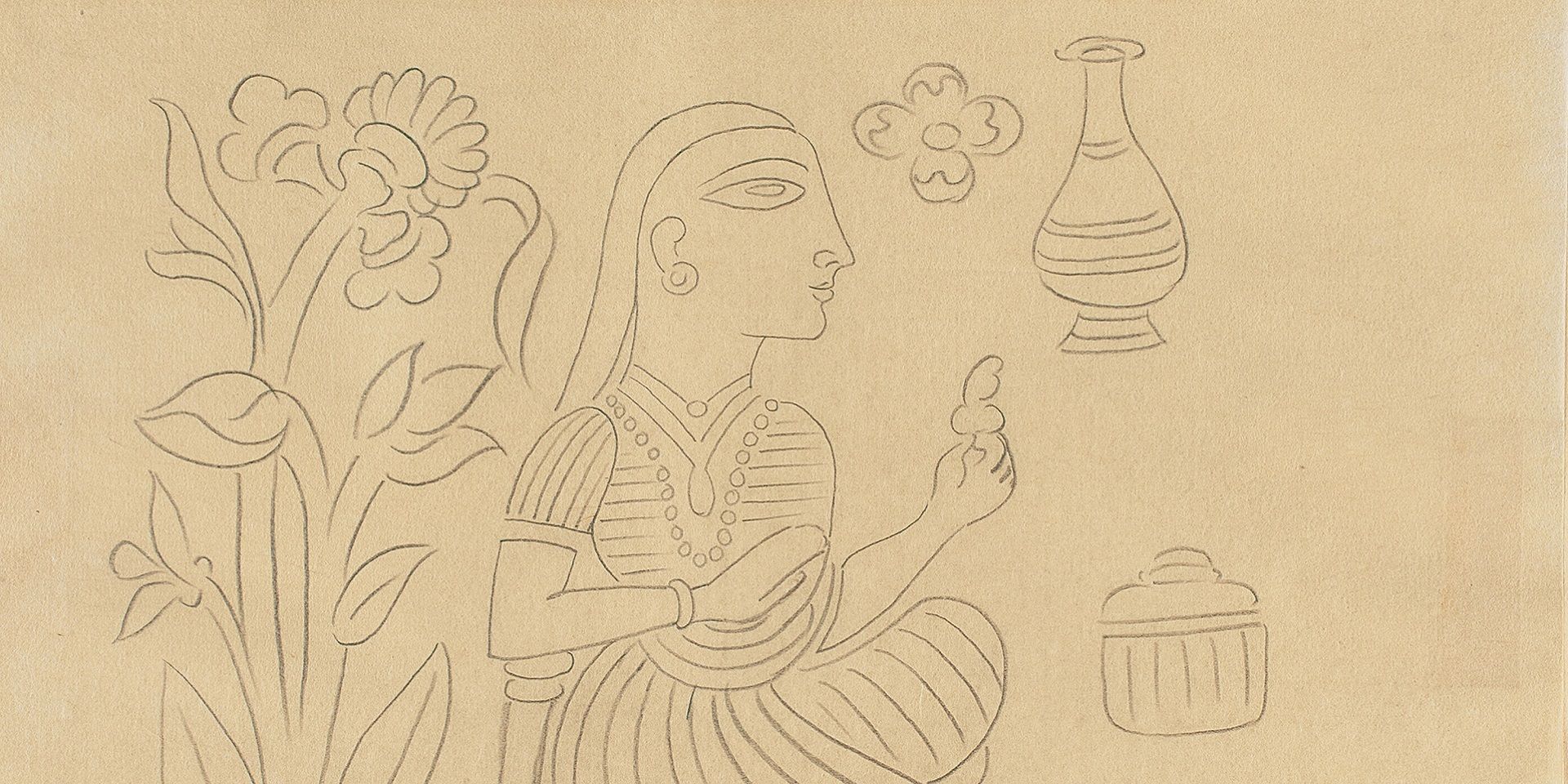

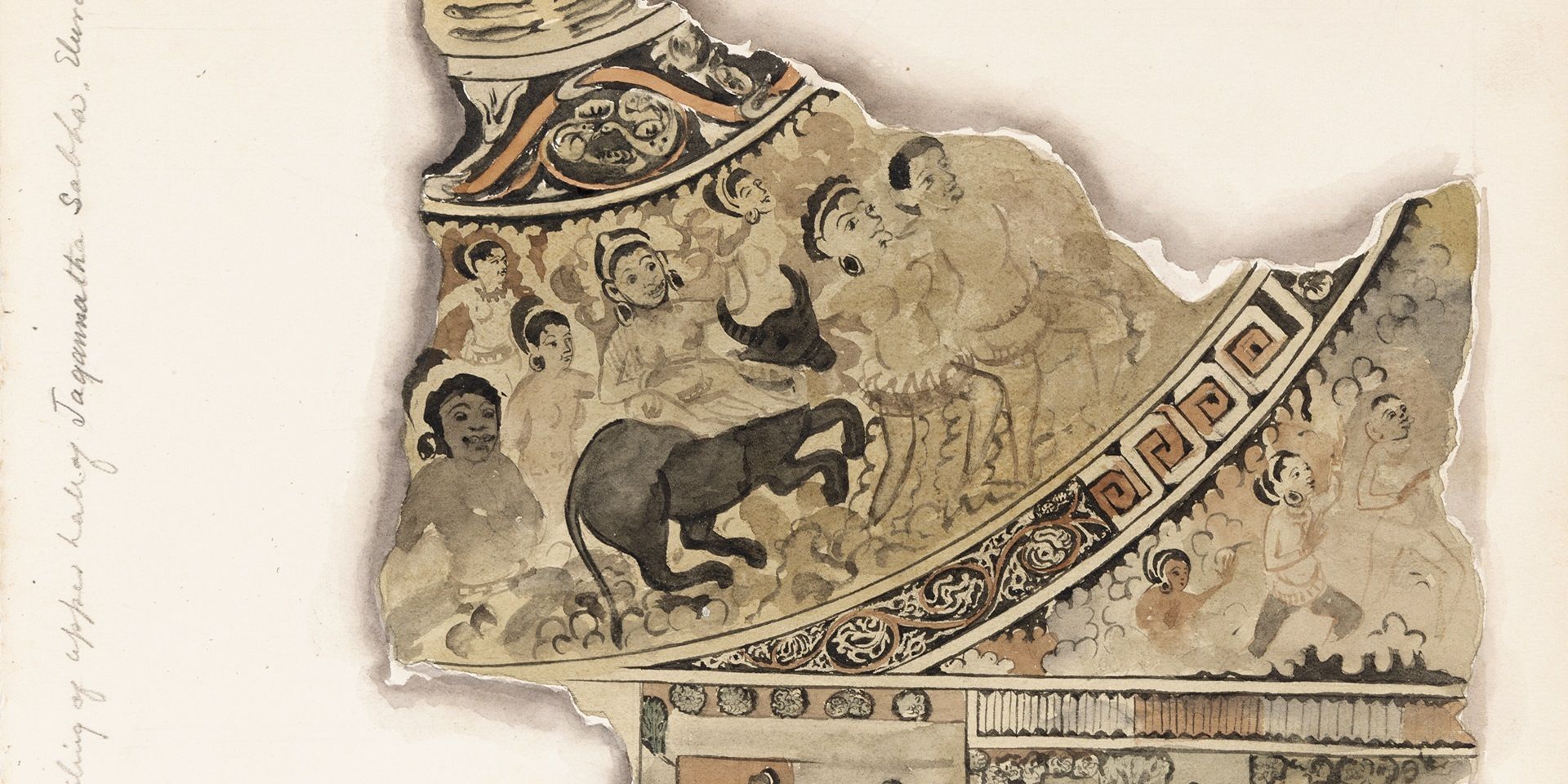

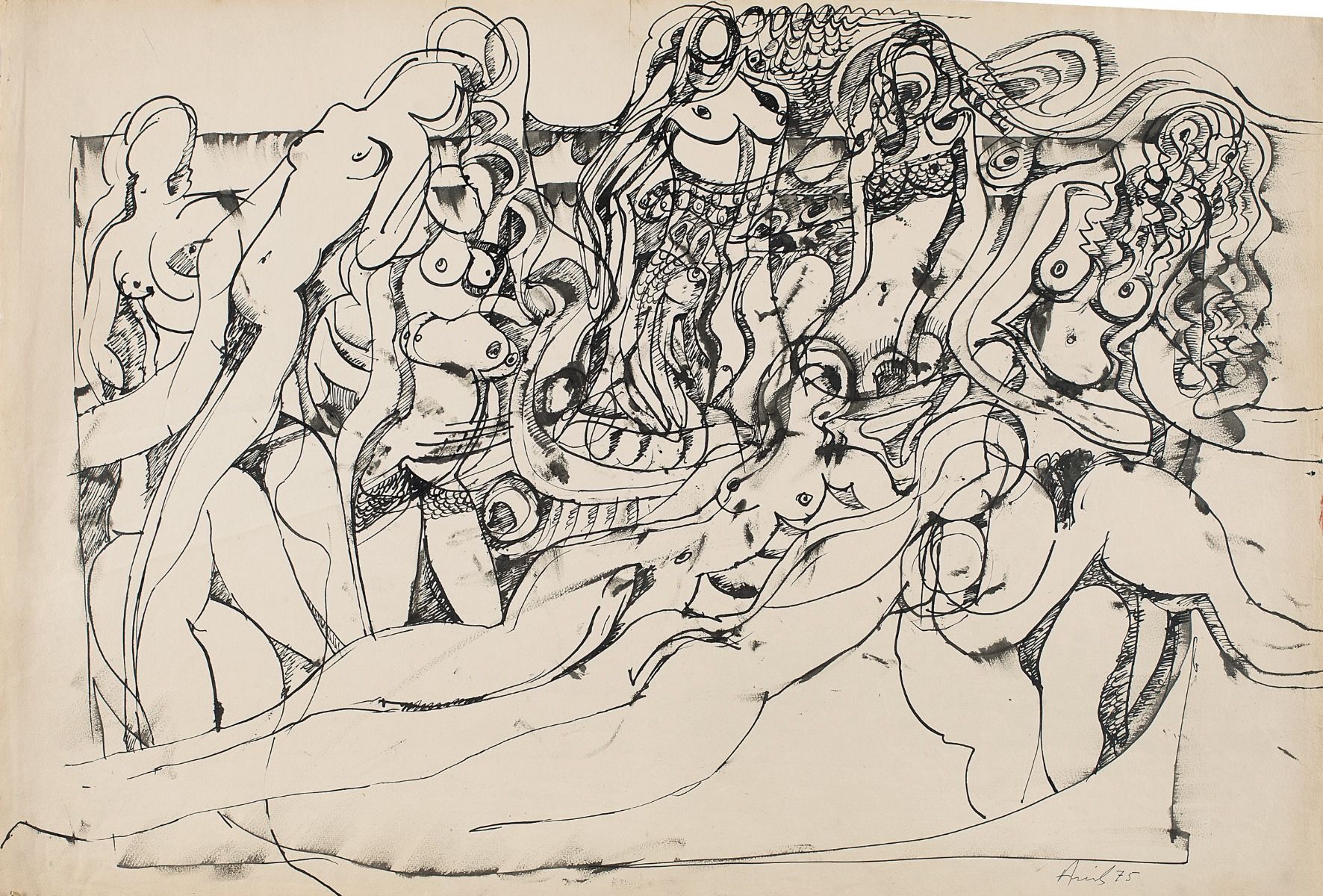

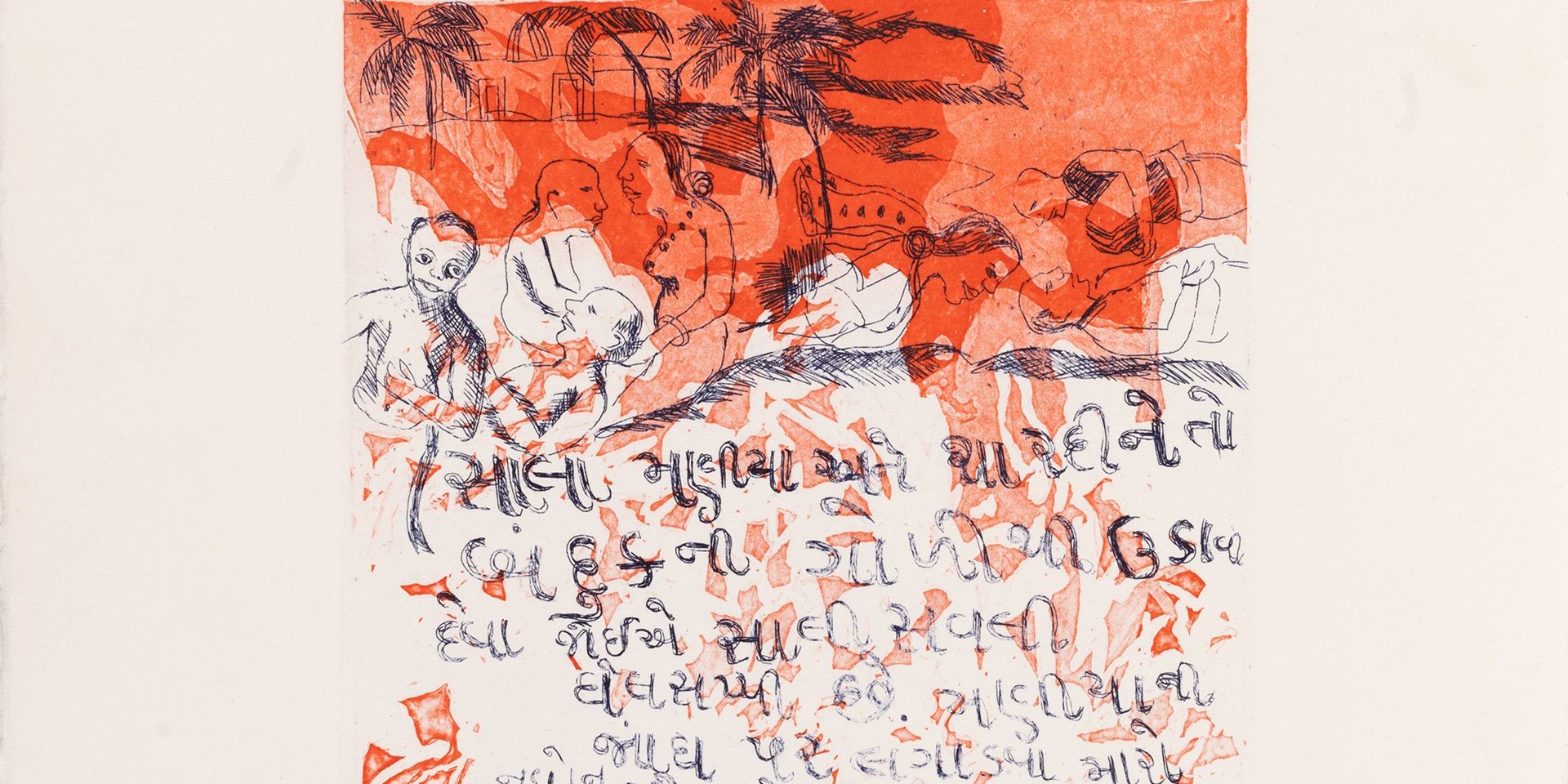

Avinash Chandra, Untitled, 1975, Waterproof ink on paper, 20.2 × 29.2 in. Collection: DAG

Endnote

[1] ‘Black’ here, as Jean Fisher has pointed out, referring to a ‘self-defining political not phenotypical category, alluding to alliances based in shared histories of colonial repression’.

References

Rasheed Araeen ed., The Other Story: Afro-Asian artists in post-war Britain, Hayward Gallery London, 1989

DAG, Contours of Identity: F. N. Souza and Avinash Chandra, DAG, 2024

Jean Fisher, The Other Story and the Past Imperfect, Tate Papers no. 12, Autumn 2009

Lucy Steeds, ‘Retelling "The Other Story" – or What Now?’, in Afterall: Exhibition Histories, 30 September 2018

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

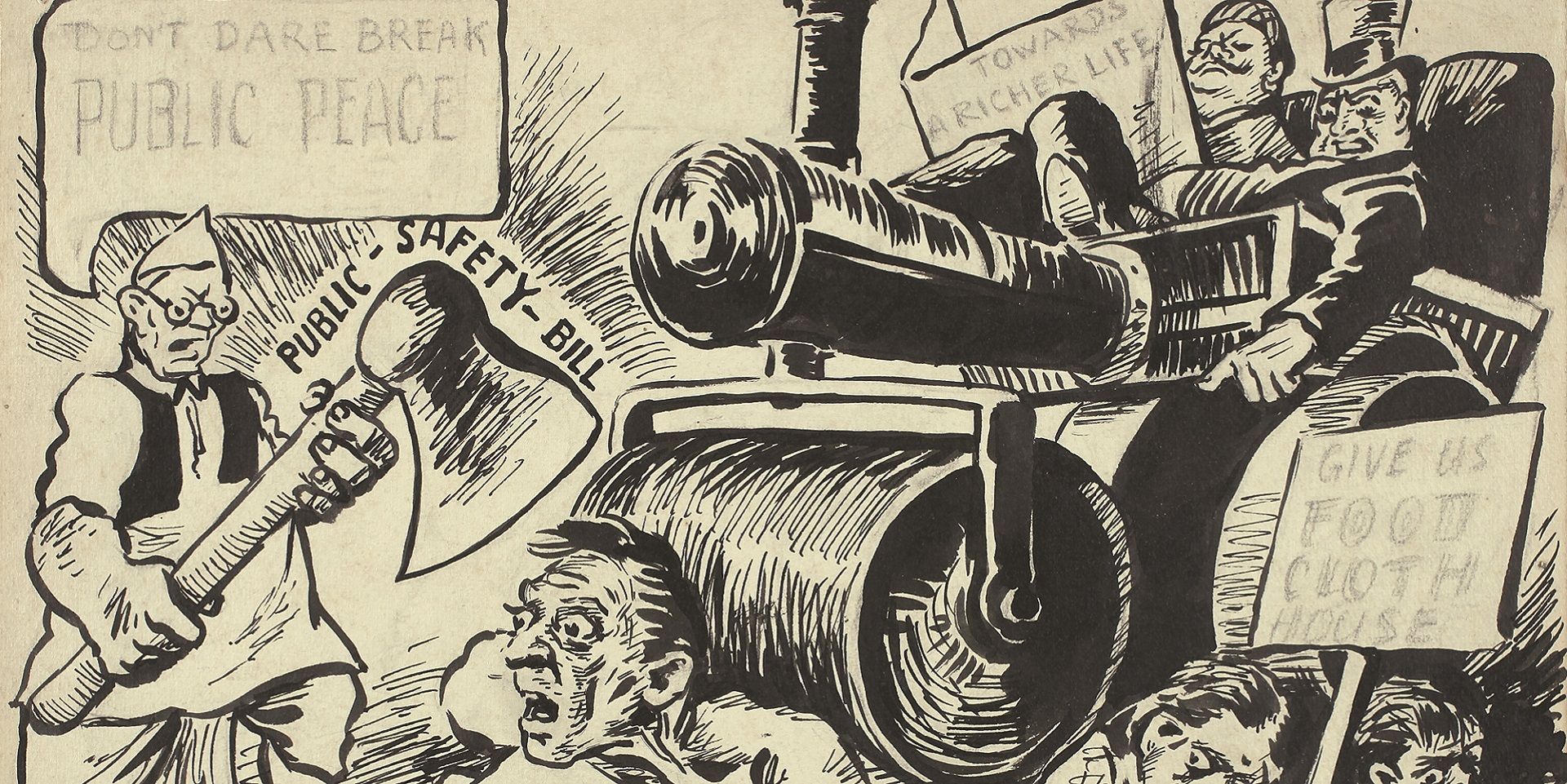

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

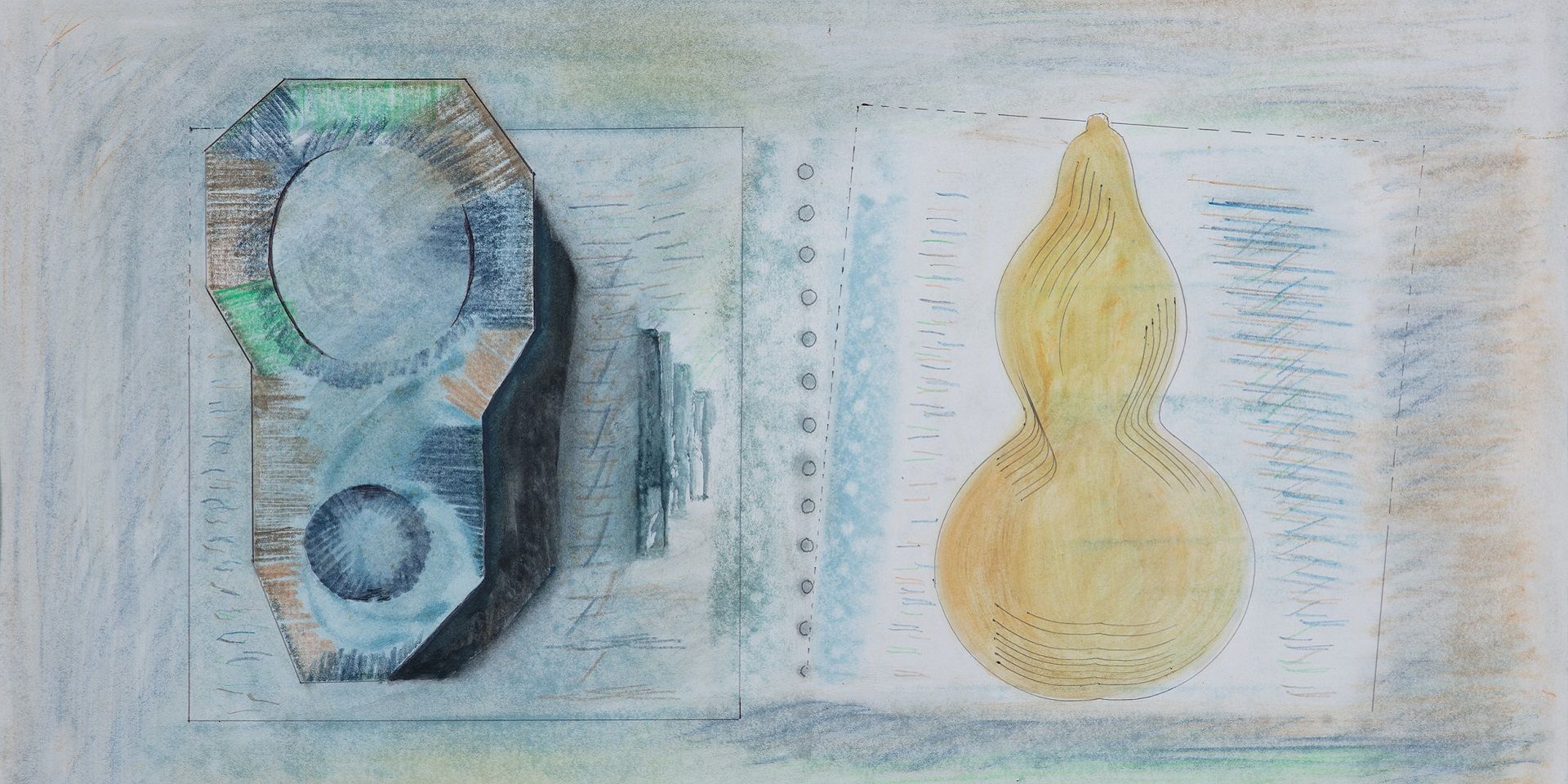

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024