Photographic Journeys: The Scenic and the Lived

Photographic Journeys: The Scenic and the Lived

Photographic Journeys: The Scenic and the Lived

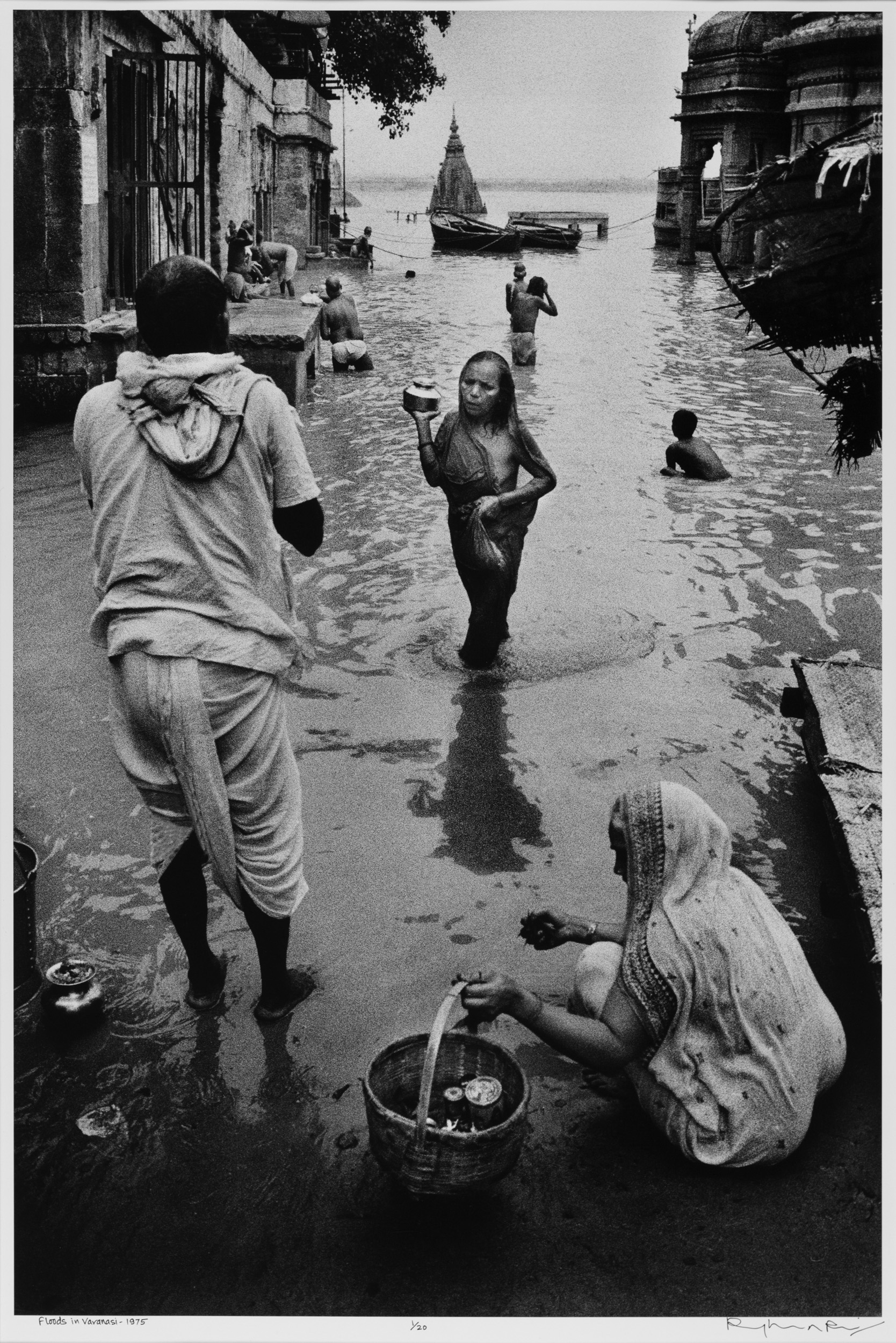

Raghu Rai, Floods in Varanasi (Detail), Inkjet print on archival paper, 1975. Collection: DAG.

What do you commonly see when you look at representations of the city of Banaras? From Puranas to contemporary films, Banaras has been framed again and again by artists over time. What becomes interesting, especially through Gayatri Sinha’s curated exhibition ‘Banaras Imagined Landscape’, are the subjects that get centralised by the artists. Does it simply represent the mythical and scenic or are we allowed glimpses into the complexities of urban life?

Art historian E. B. Havell offers the following depiction of Banaras in 1905, ‘…the colossal flights of stone steps, great stone piers and wooden platforms jutting out into the sacred stream, dotted river with palm-leaf umbrellas, like gigantic toad-stools, under which the ghatiyas are sitting to render various services to the bathers, the countless spires of Hindu temples, dominated by the lofty minarets of Aurangzeb’s mosque. At last, Surya, the Sun, appears, glowing with opal fire above the cloudy bars of night. The miasmatic mists, like evil spirits―the wicked Asuras―shrink and shrivel and vanish into thin air…’

|

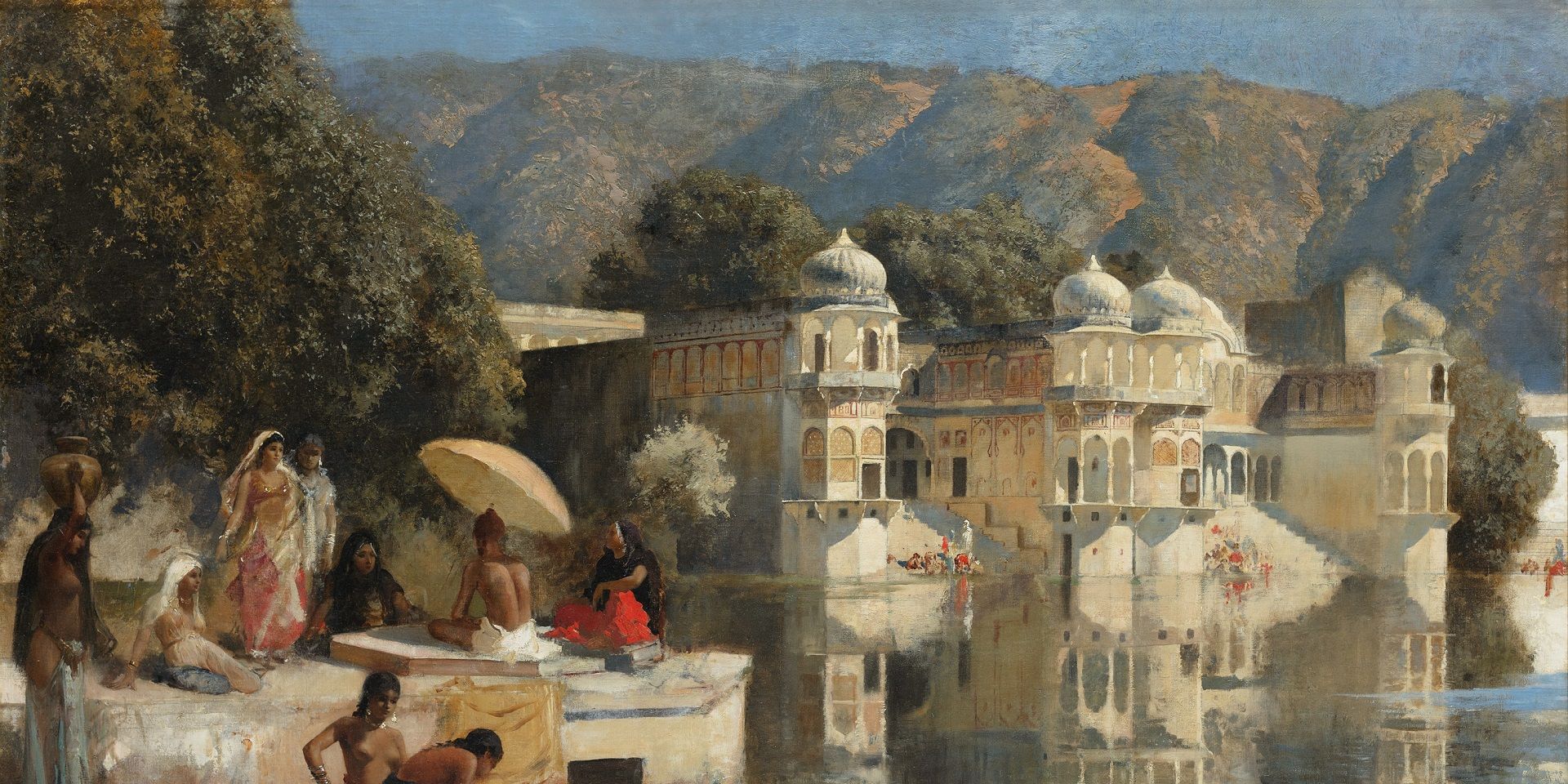

Thomas Daniell, Aurangzeb’s Mosque, Oil on Canvas, 1700-1800, Wikimedia commons |

The romantic gaze of Havell transforms the built environment of a city into a mythologised world, a platform where Gods and demons seem to cavort alongside humans. This has been the popular representation of the city of Banaras, a sacred and eternal place, where everything seemingly revolves around the sites of pilgrimage and legends of the divine. Such an image has been concretised through storytelling and pictorial representations that privileged the ghats and temples piled on the curved banks of the Ganges. The complex histories and urban forms of the city lose focus as Europeans and Indians alike have tried to construct a ‘Puranic’ character of the city where an untouched Hinduism can be witnessed.

The ‘timeless’ ghats of Banaras were largely constructed by Marathas in the eighteenth century, and bear a multi-layered history of negotiations between multiple groups of people. A simple glance at the range of houses that overlook the alleys reveals the rich diversity that has shaped this city. Banaras, once the commercial heart of North India, thrived as a key link in the trade route connecting Bengal to the Maratha territories. Yet, history often overlooks the powerful ‘gosains’ who once held dominion over all activities along the ghats, the Chet Singh Palace, where the final chapters of a Mughal family were written, and the ‘kothiwalas’, who made Dashashwamedh Ghat their bustling center of operations. Yet the earliest indigenous maps of Banaras like ‘kashidarpana’ reinforced the primacy of the sacred geography over the lived histories of the city. Madhuri Desai notes, ‘The city’s religious life was constituted through spatial systems, including in the form of pilgrimage routes…’ the development of which was a focal point for the colonial government and the elites of Banaras.

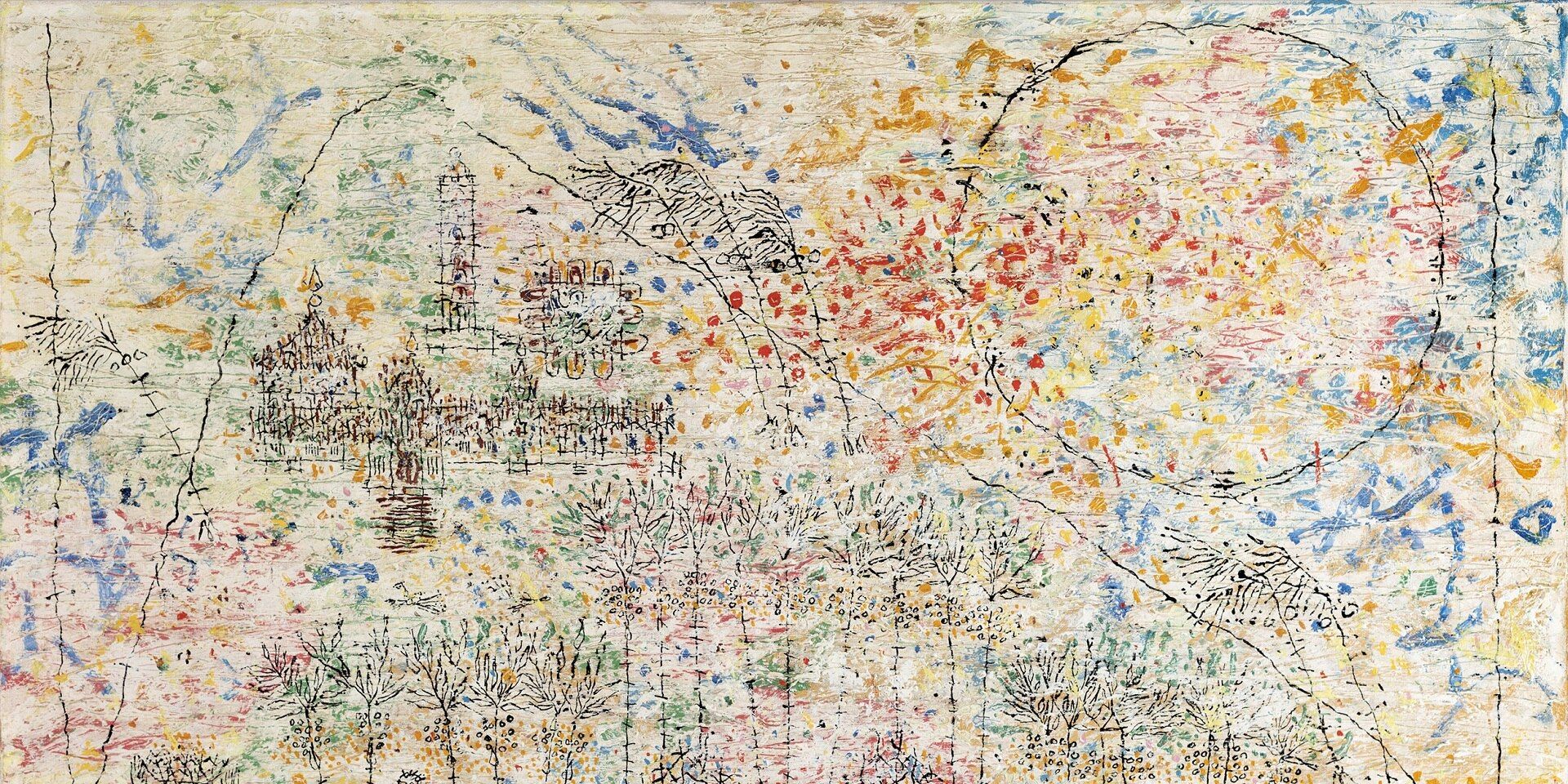

Unidentified Artist, Map of Kashi, Offset print on paper. Collection: DAG

When colonial painters like Thomas Daniell visited Banaras in the eighteenth century, their visual depictions of the city were coloured by the contrast they wished to draw between an unspoiled Hinduism and the tyranny of the Mughal rule. This classical manner of painting was also a way to document and categorise territories that were controlled by the British, minimising the people who lived within it. As photography developed, the same expectations slipped into that medium. Samuel Bourne came to India in 1863 and produced almost 2,500 photographs for his studio Bourne and Shepherd. A commercial photographer, he preserved the same aesthetics centralised around the ghats and the majestic architecture of the temples. The people, when present were diminished to their roles as pilgrims performing sacred rites along the ghats. Bourne’s photographs were also shaped by the growing industry of travel and the demand for architectural, landscape and topographical photographs of India by Europeans. This resulted in a dematerialisation of the city detected in the subjects that gain focus in his photographs. When capturing Manikarnika Ghat which hourly sees the burning of dead bodies, he centralised the temples and details of their ornate architecture. The people became smudges compared to the towering spires of the ‘Vishnu Pud.’ There is a deliberate sanitisation of the urban forms to preserve the timeless quality of the landscape. Anyone who has been to Banaras will realise how singular these representations of the ghats are. Rana P. B. Singh reiterates the popular saying about Banaras streets, ‘rand, sandh, seedi, sanyasi, ense bache to seve Kashi’ (if you can escape from the widows, bulls, stairs and saints, then only can you live in Kashi). None of this confusion seems to be represented by the colonial painters or in the photographs by Bourne.

Samuel Bourne, Vishnu Pud and Other Temples near the Burning Ghat, Benares (Varanasi), Silver albumen print mounted on card, 1860. Collection: DAG

The Great Mosque of Aurangzeb, and Adjoining Ghats (Varanasi), Silver albumen print mounted on card, 1860. Collection: DAG

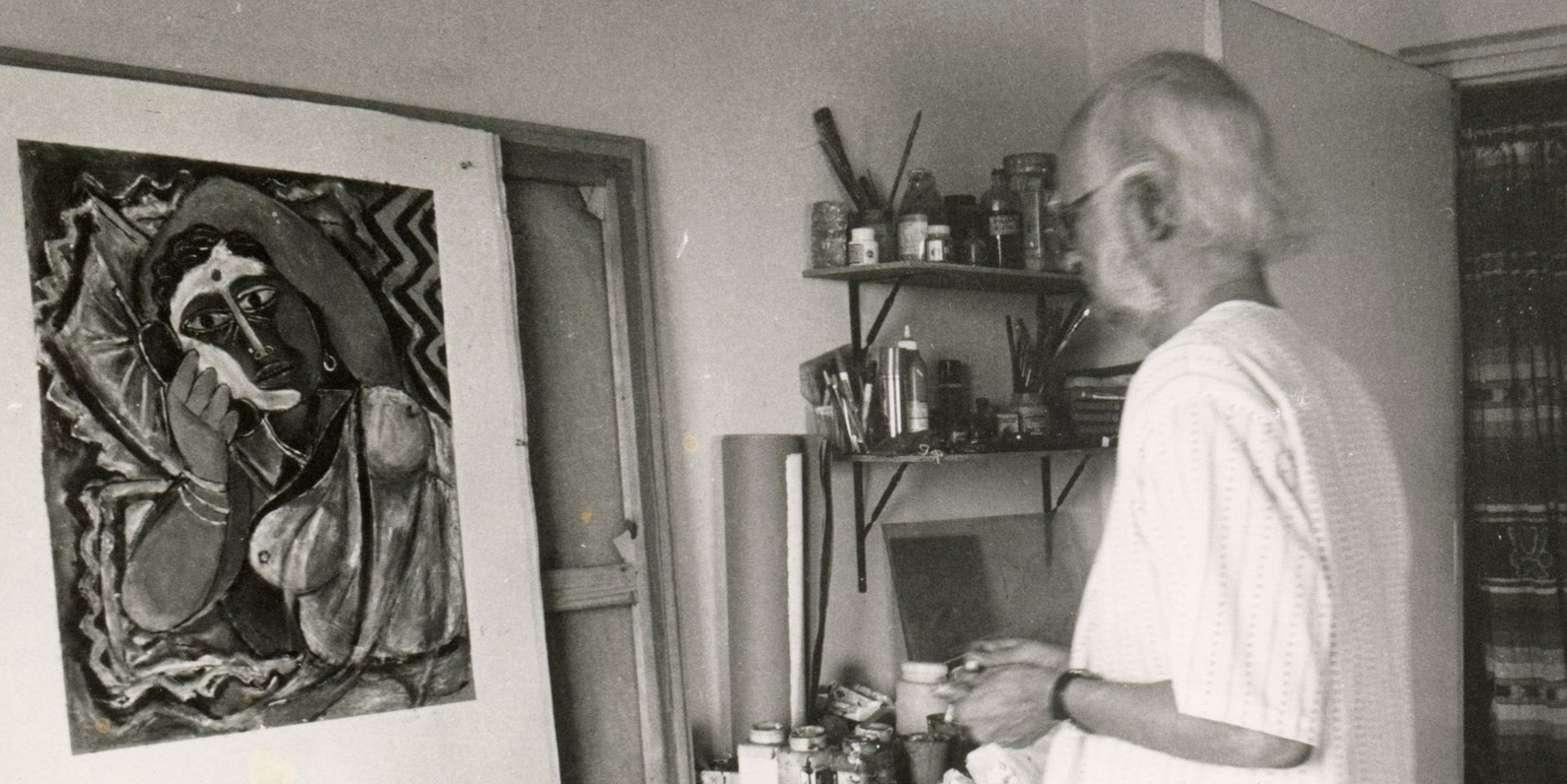

After independence there is a deliberate shift that can be noticed in the visual representation of the city, where the lived realities of people start to take centre stage. Through the lens of photojournalist Raghu Rai for instance, Banaras attains a completely different character. As a person who has extensively documented people and spaces afflicted by disaster, he distances himself from western stylisations in photography. He instead adopts the philosophy of capturing the truth in its honest and simple form, which reflects in his photography of Banaras and its people. Banaras gets flooded every year, as the water of the Ganga reaches critical levels, flooding the ghats and streets of the city. Residents have to be relocated and sewers overflow making large parts of the city uninhabitable. The redevelopment every year and concretisation of the ghats keeps putting the people at greater risk whose livelihoods are dependent on pilgrimage and tourism. Raghu Rai captures this phenomenon in ‘Floods in Varanasi’ showing how people are compelled to risk their lives, even when the river is flooded, for their livelihood.

|

Raghu Rai, Floods in Varanasi, Inkjet print on archival paper, 1975. Collection: DAG. |

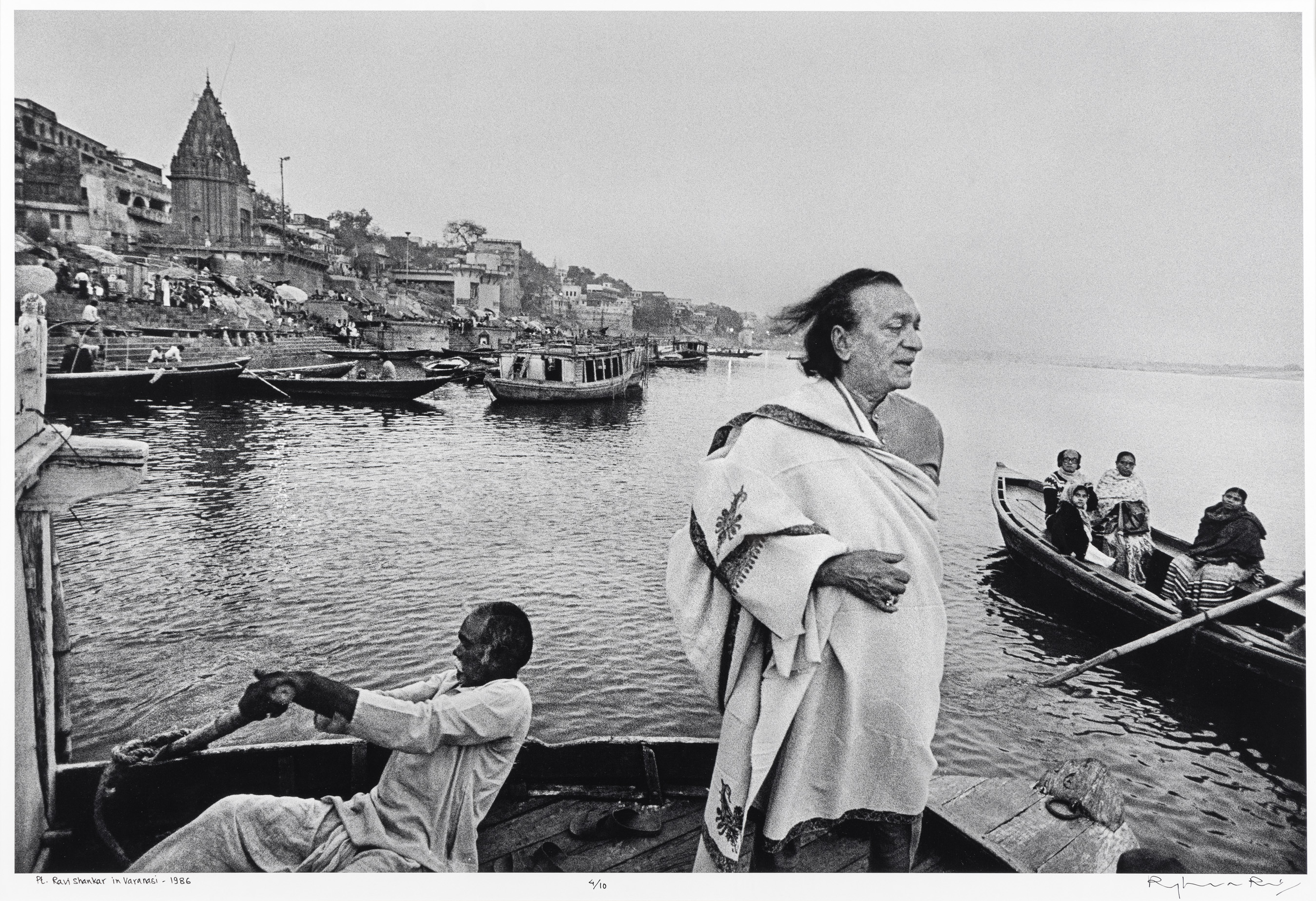

The serene architecture diminishes in his work as the ghats are seen animated by the activities of people. It is not that Raghu Rai is impervious to the significance that the geography and architecture in Banaras holds, as we see in his photograph of the late Maharaja and Pandit Ravi Shankar. He manages to alter the gaze with which we see the city in his photographs. The backdrop to Ravi Shankar’s photograph is the familiar picturesque curve of the Ganges, which in his photograph appears as a lived space. The Maharaja in his palace is a familiar trope of paintings, but Raghu Rai manages to humanise the grandeur of the palace and the Maharaja. This change in the politics of representation does not alter the significance that the city of Banaras holds in our culture and history, it simply grounds it in those who inhabit it.

Raghu Rai, Pandit Ravi Shankar in Varanasi, Inkjet digital print on museum quality archival paper, 1986 Collection: DAG

Raghu Rai, Late Maharaja of Benaras, Inkjet print on archival paper, 1986 Collection: DAG

Readings:

1. E. B. Havell, Benares the Sacred City, Blackie and Son Limited, London, 1905.

2. Madhuri Desai, ‘Urban Negotiations: Urban Space and Narrative in Banaras.’, Banaras: Urban Forms and Cultural Histories, Michael E. Dodson (ed), Routledge, 2012.

3. Rana P. B. Singh, Banaras: Making of India’s Heritage City, Cambridge Scholar’s Publishing, 2009.

related articles

Essays on Art

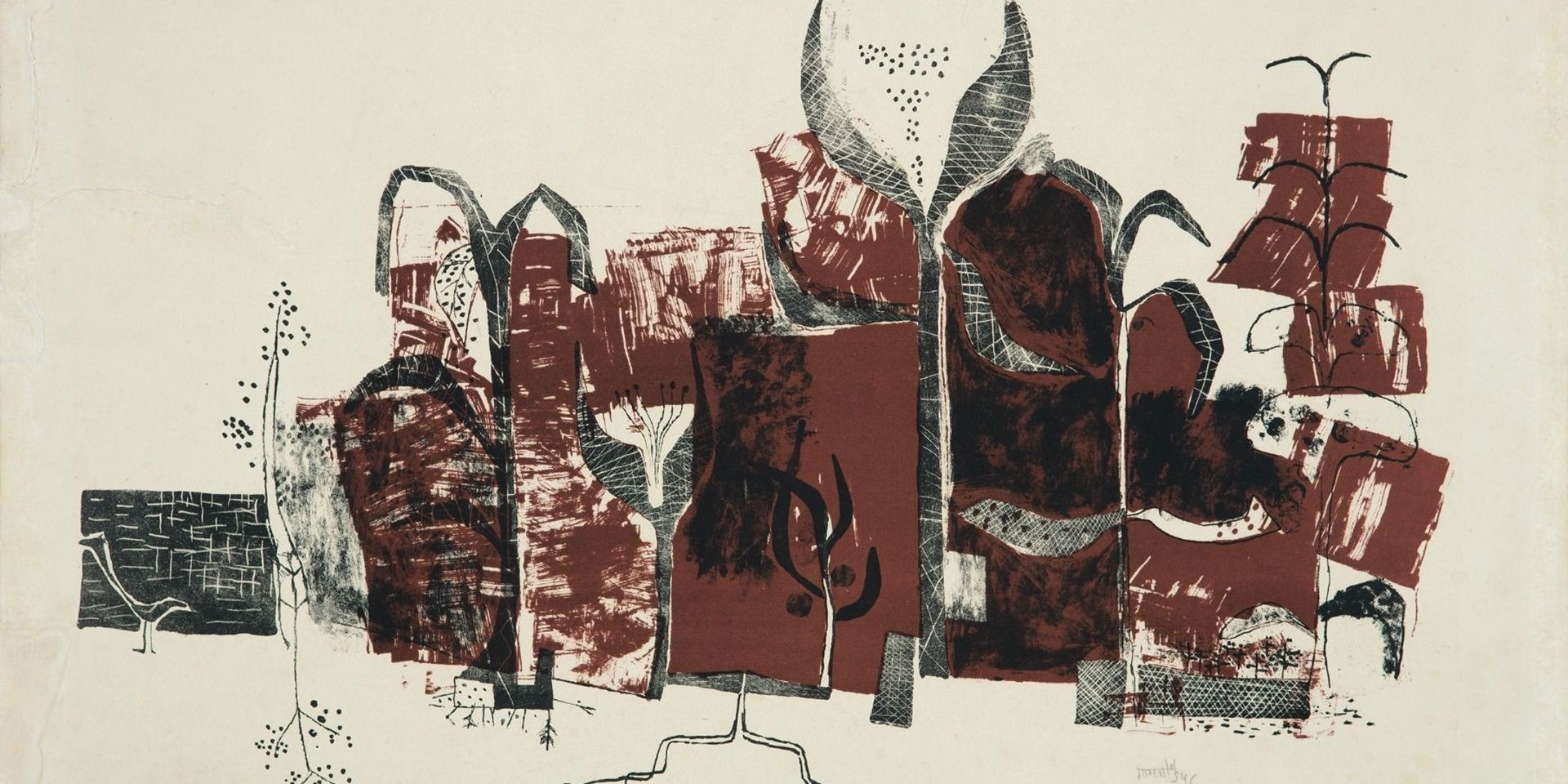

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

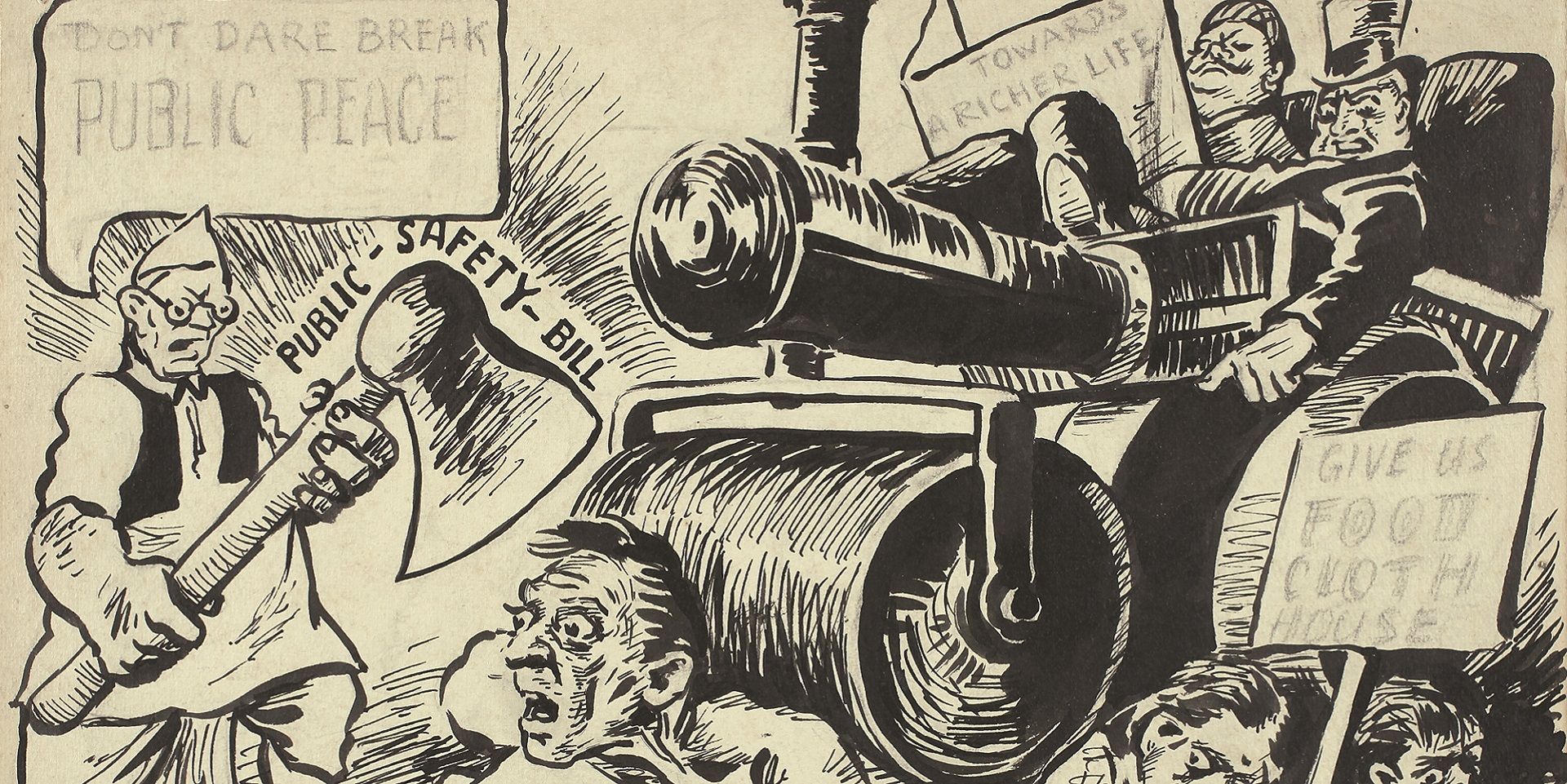

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

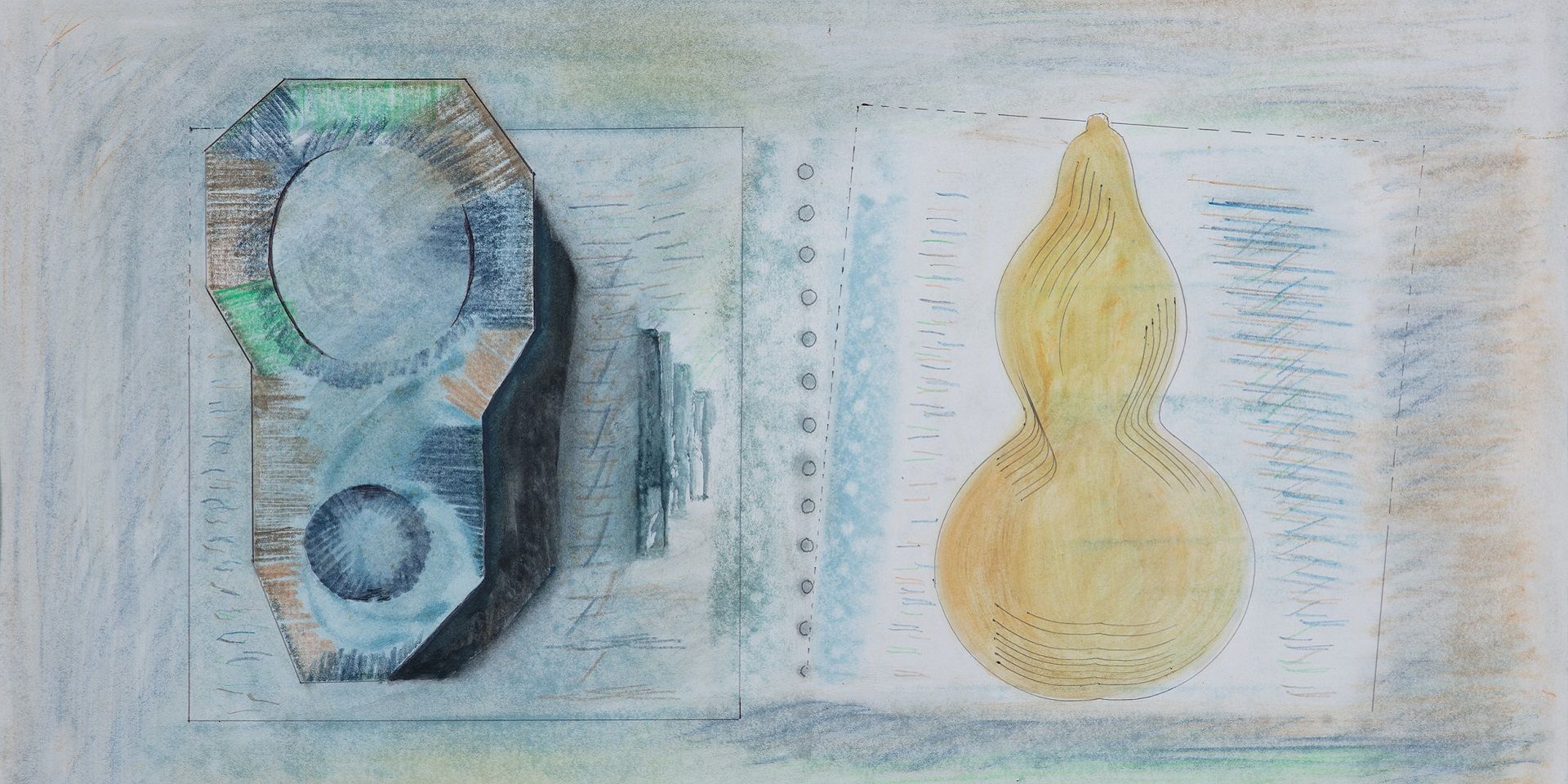

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

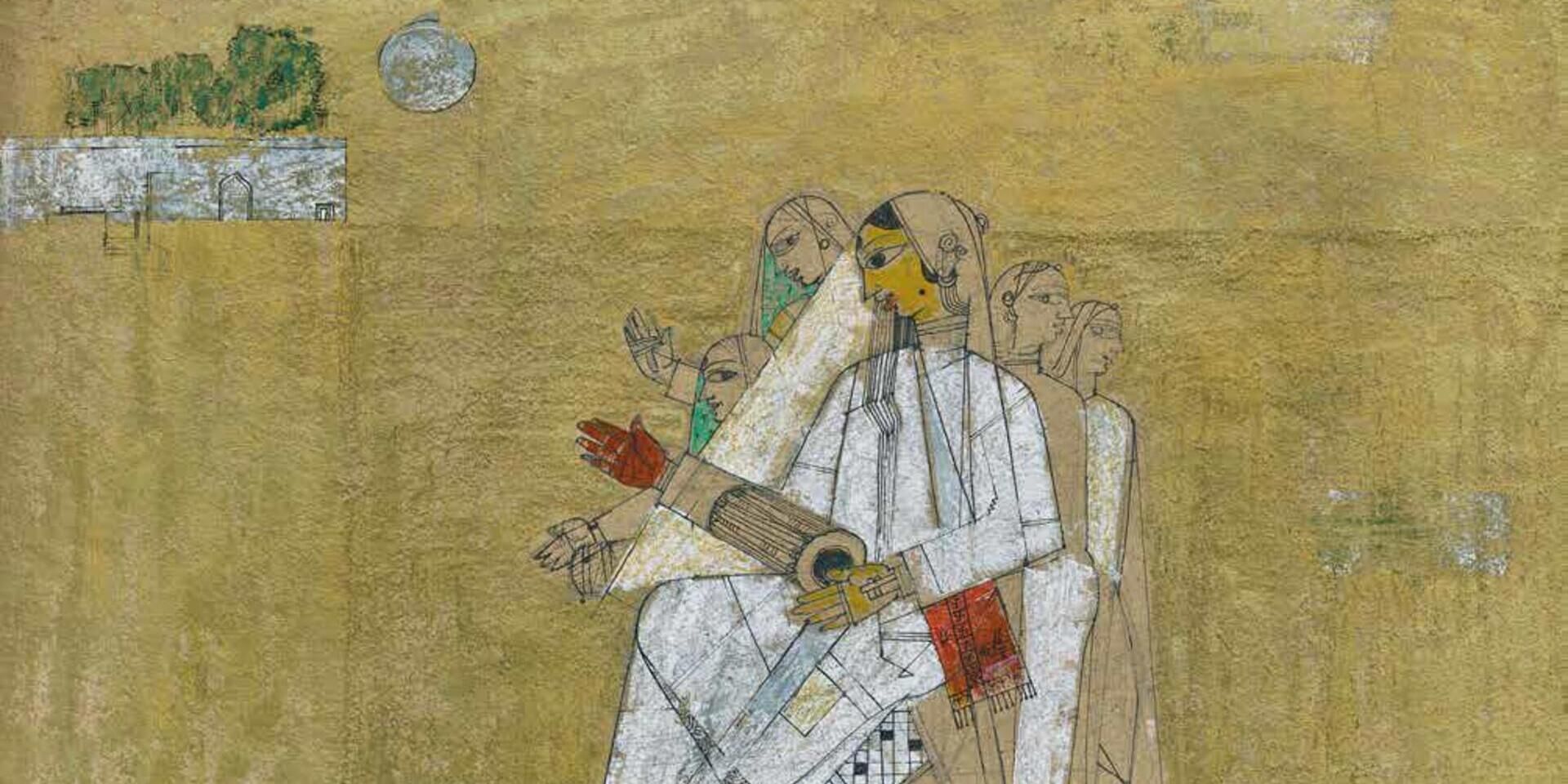

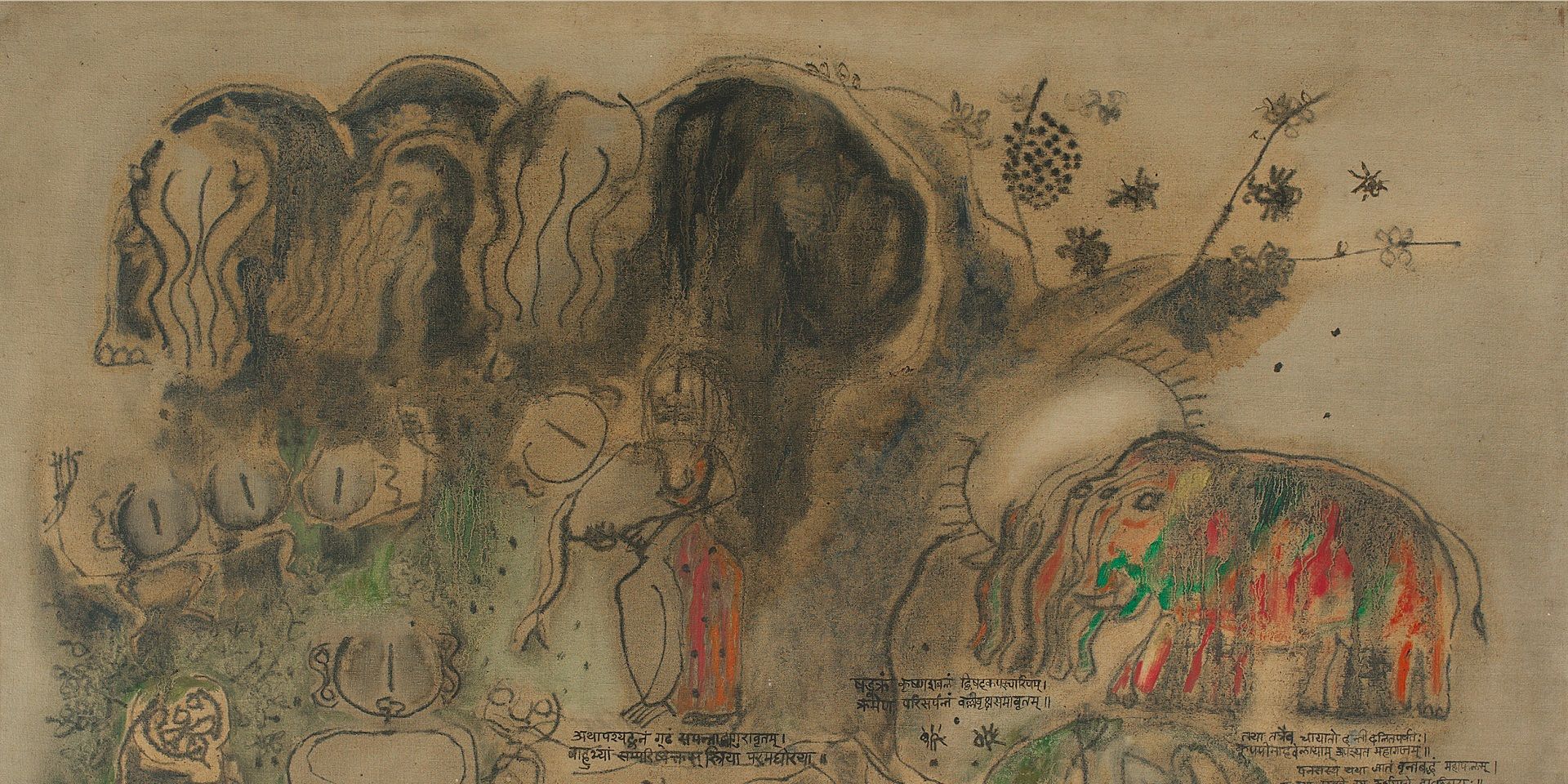

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

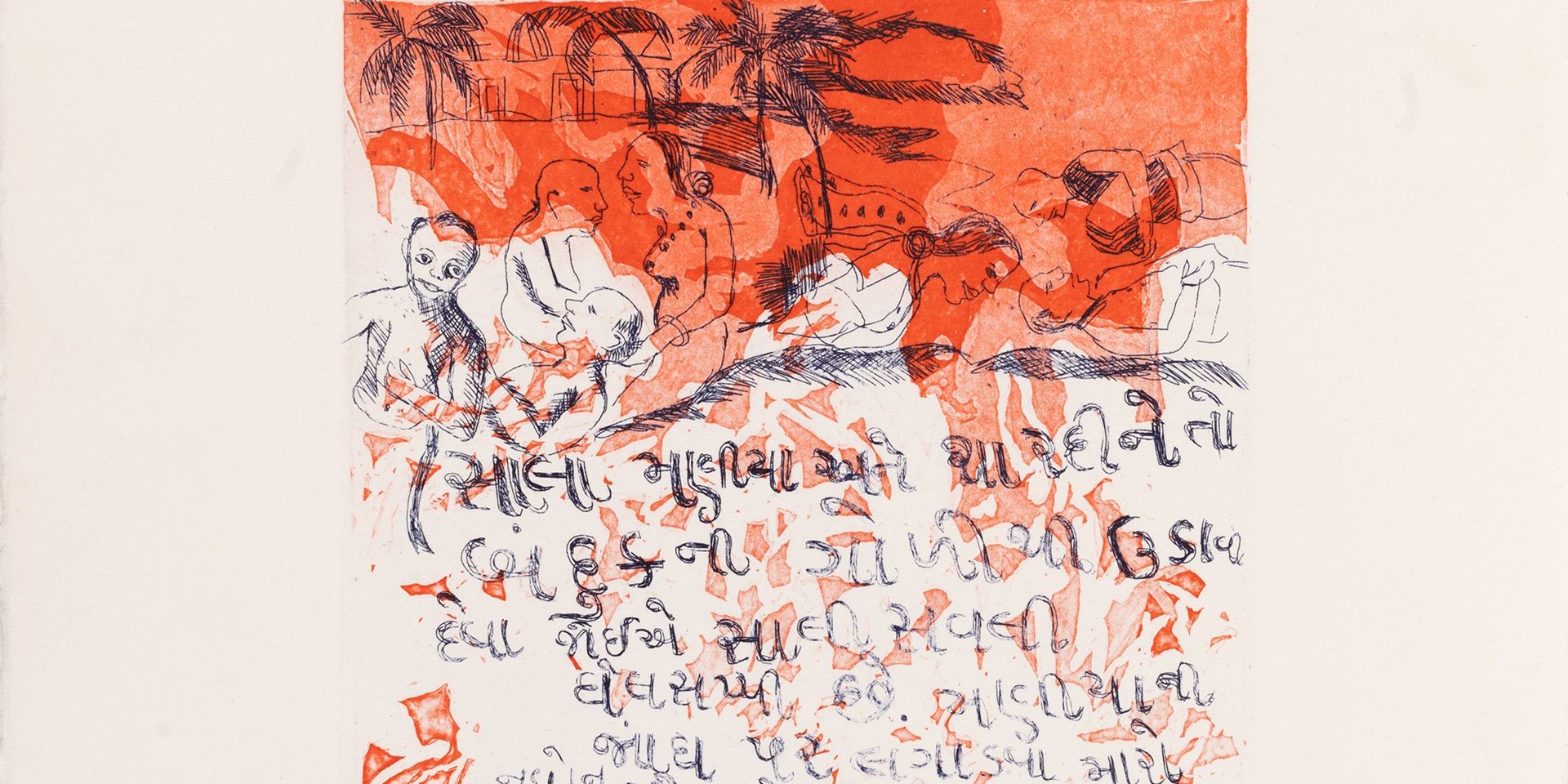

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024