Making Madras Modern: Rediscovering the legacy of K.C.S. Paniker

Making Madras Modern: Rediscovering the legacy of K.C.S. Paniker

Making Madras Modern: Rediscovering the legacy of K.C.S. Paniker

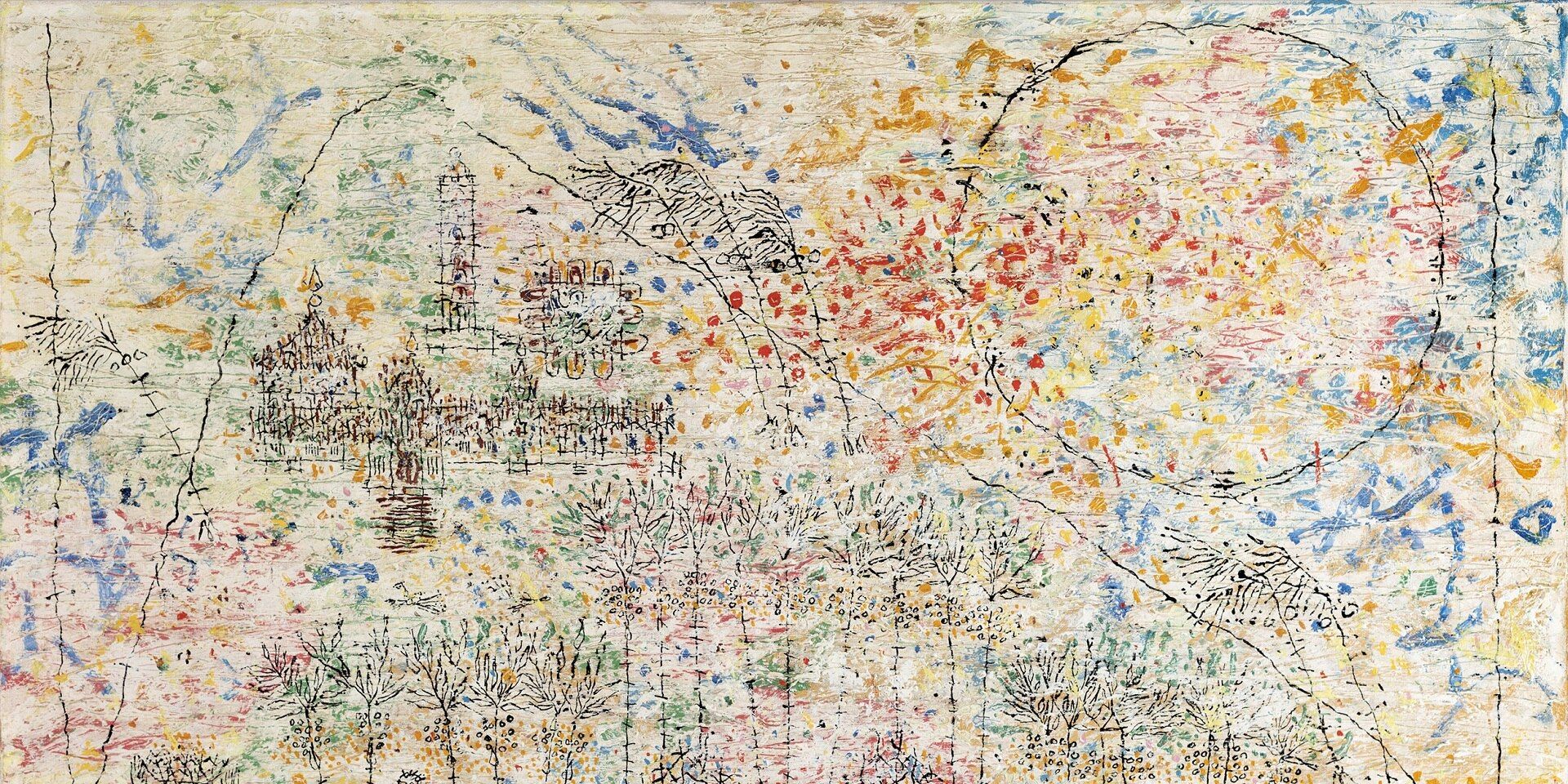

K. C. S. Paniker, The Foot Bridge (detail), Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 1950, 15.5 x 16.7 in. Collection: DAG

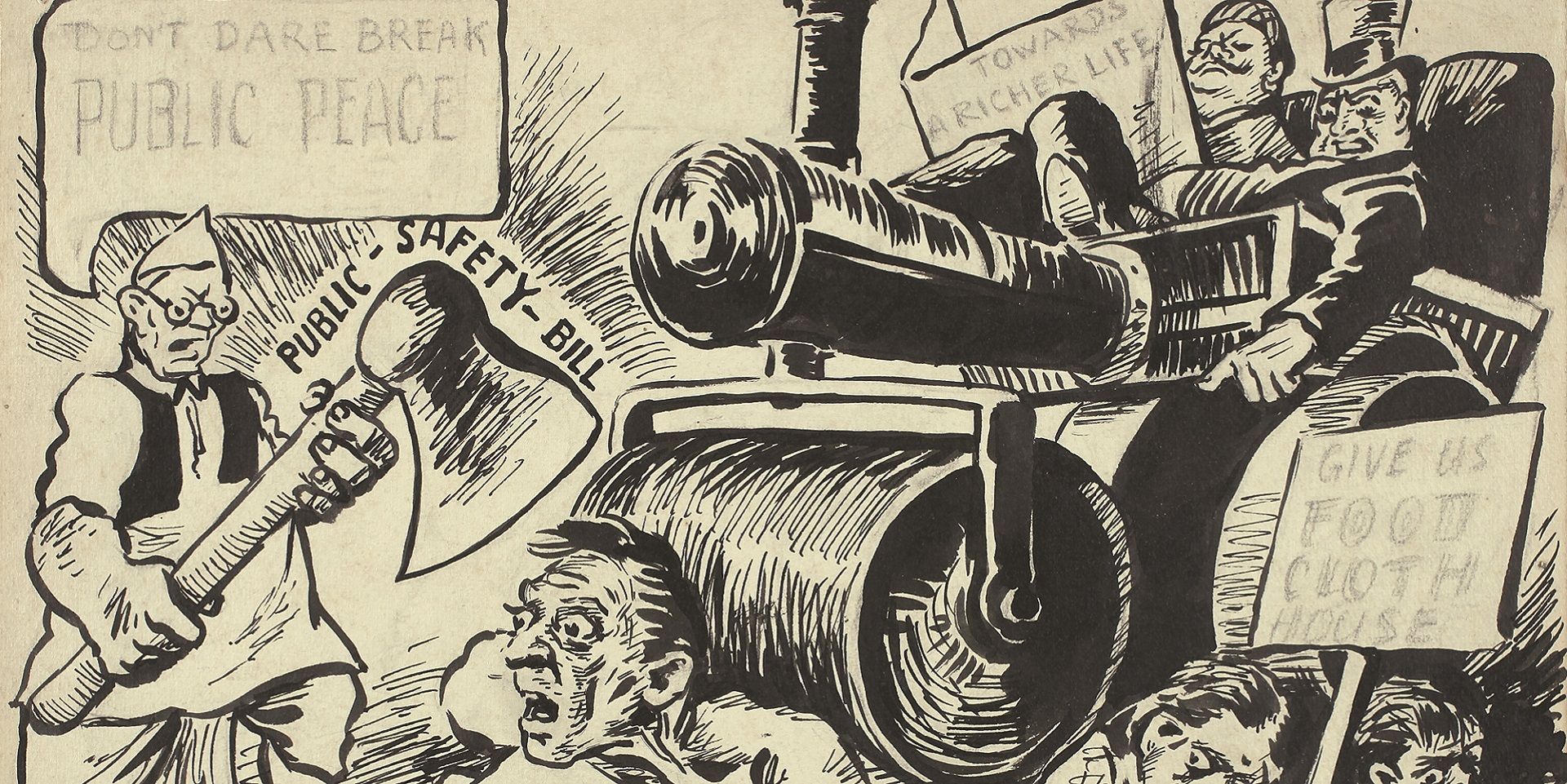

The most influential member of the Madras Modern movement, K.C.S. Paniker continued the work of progressively modernising the colonial art school at Madras (now Chennai), which was started by D. P. Roy Chowhdury before his time. While Paniker respected Roy Chowdhury as a senior colleague, he also had strong disagreements with his style of pedagogy, art-making and administration. Institutionally, this was one of his great legacies for Indian modern art, even as he continued to experiment and push his own art in surprising directions and participated in influential discourses about the role of art in a postcolonial nation.

K. C. S. Paniker (1911-1977) was a pioneering figure in the Madras Art Movement, known for his metaphysical and abstract paintings and sculptures that engaged with regional aesthetic and pictorial traditions. Born in Veliyankode, in Kerala’s Malabar district, Paniker played a crucial role in establishing a distinct artistic agenda within the broader postcolonial Modernist framework.

|

K. C. S. Paniker, Untitled, Bronze, 9.7 x 7.5 x 7.0 in. Collection: DAG |

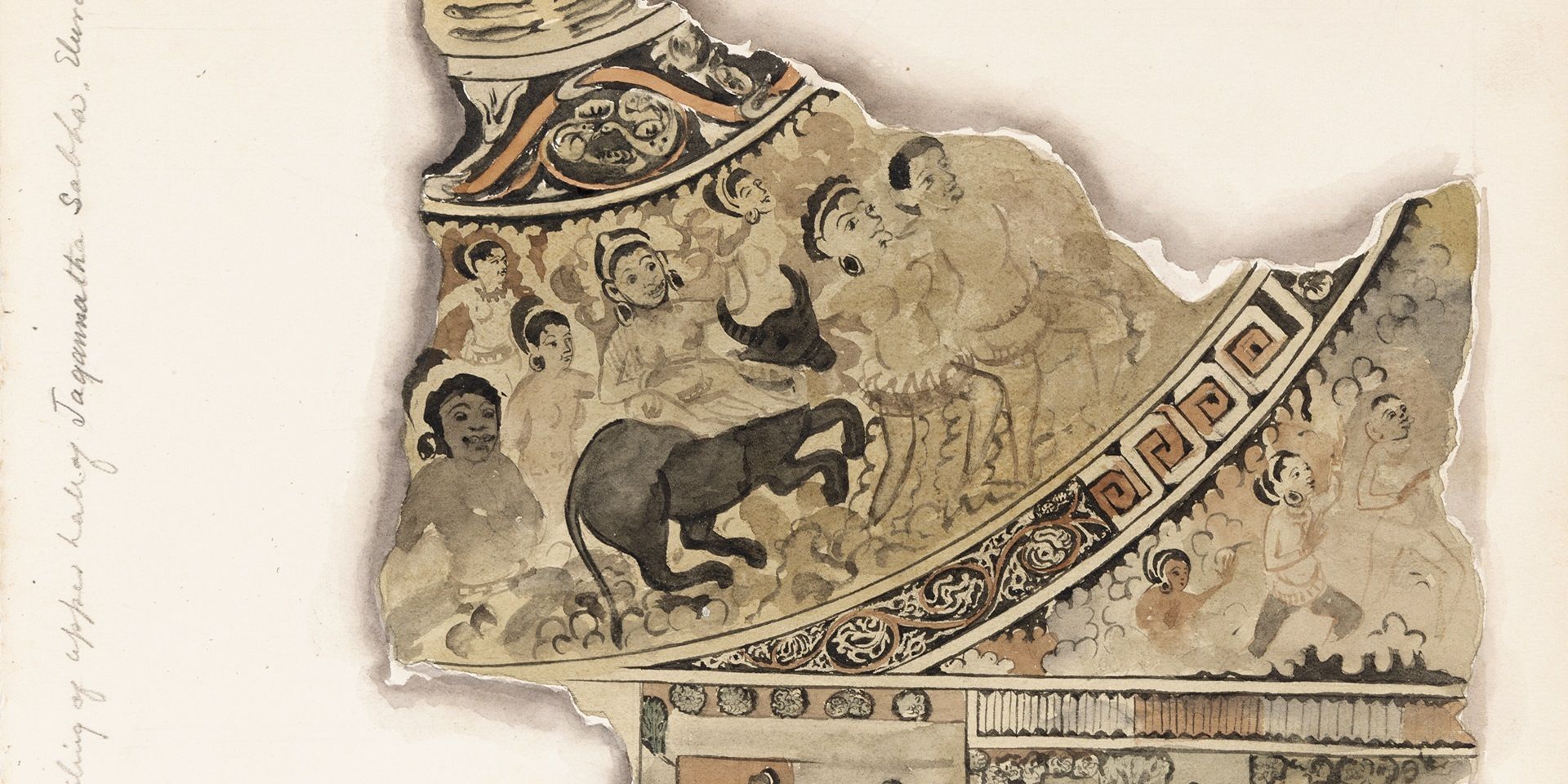

Paniker's artistic journey began with watercolor landscapes and figural drawings, but he later transitioned to a more abstract style that drew inspiration from indigenous visual languages and traditions. He emphasised the exploration of local cultures and artistic idioms, steering his students towards a model of Modernist art that was rooted in regional identity rather than conforming to Western influences. Like D. P. Roy Chowdhury, for Paniker too there was an organic connection between words and images. In an autobiographical piece exploring his origins as an artist he remembers a time when he would spin out tales of heroism to impress his friends and adult relatives. The impulse behind it, he reckons, had to do with a sense of inferiority. Moreover, he connects this sense of inferiority to the work of an overwhelming gaze that he sought to evade. Subconsciously, one could see this as an early attempt to find problems with the way normative ways of seeing were culturally constructed during the colonial era and the need to work in the shadow of such gazes to recover sights and scenes that were personal for him, rather than mere technical exercises: ‘…from my childhood days, ever since consciousness dawned on me, what has haunted by imagination throughout was a sense of some deficiency, and a sense of inferiority. I had yet another awareness; that if I had been alone; if there were no one to see what I was doing, I would be able to do something beyond the capacity of most. This helped me to land into many scrapes. Though my tales about my imaginary daredevilry were made fun of by other children, the elders listened to these amusedly. And they used to ask me to repeat such tales. However, I used to feel that I had never succeeded appreciably in this diversion. And I used to wonder why. But, I was helpless to remedy it. With the narration of such tales, I used to gather some sort of self-confidence. And I had nothing else to do.’

|

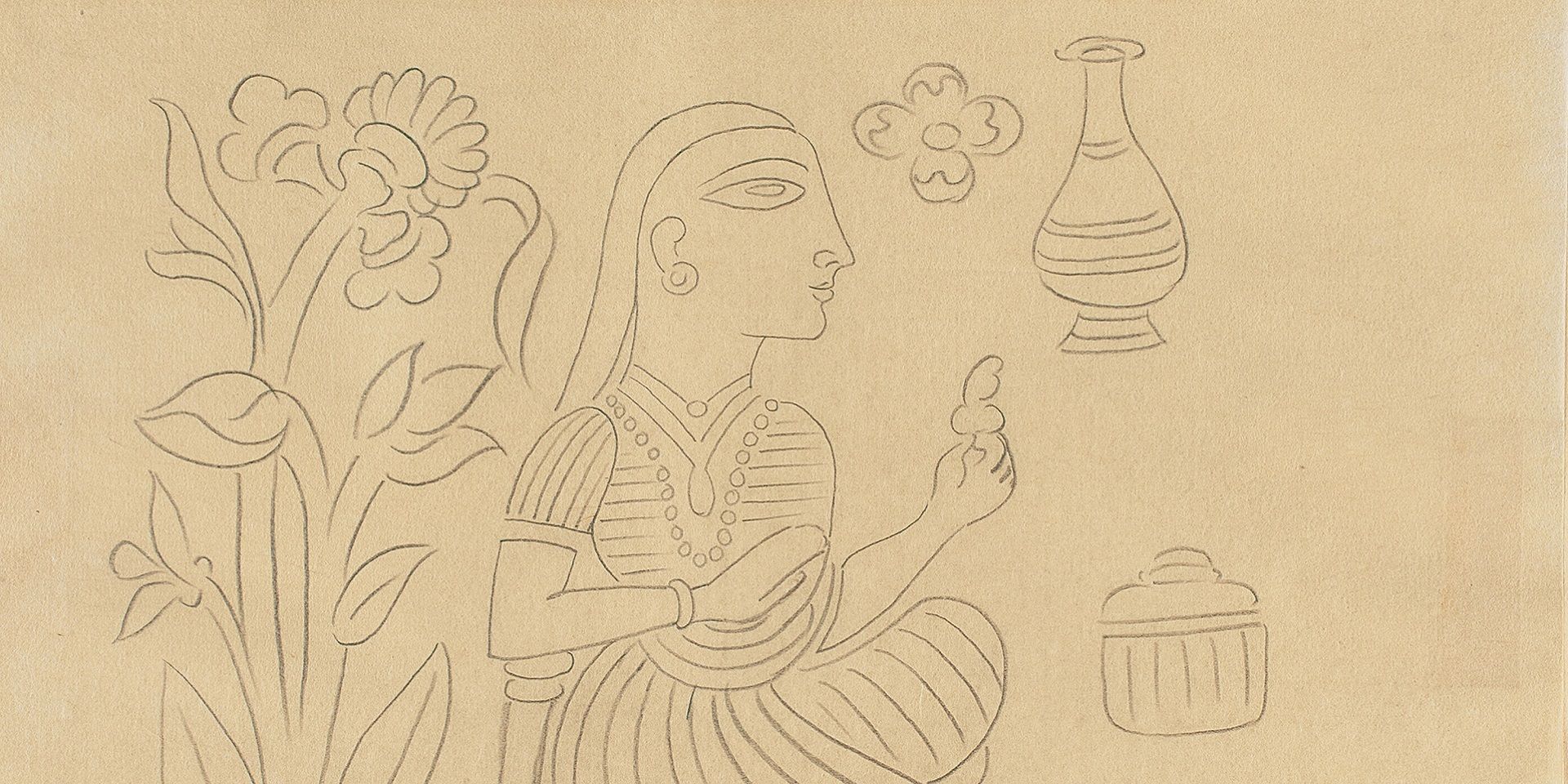

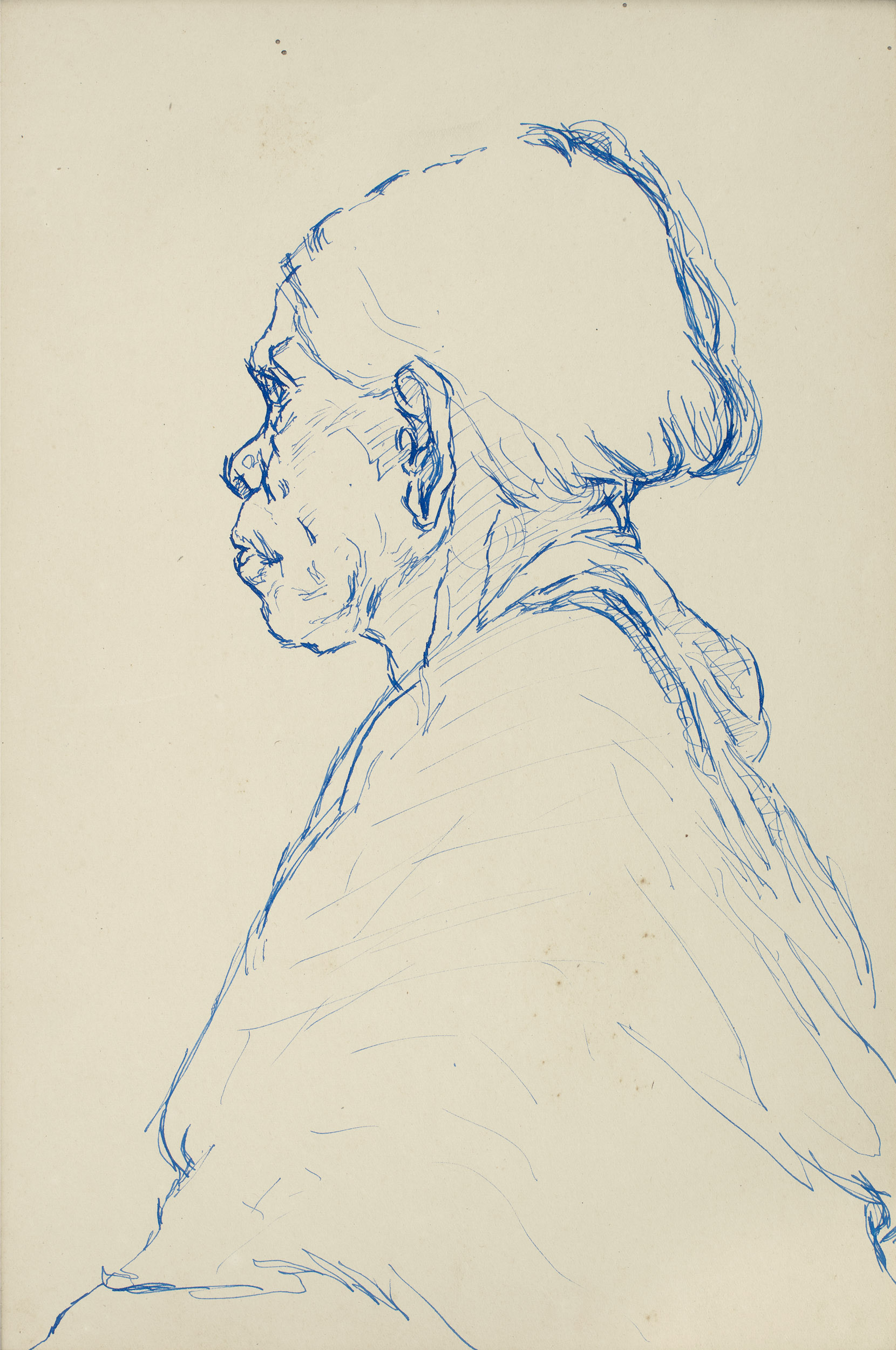

K. C. S. Paniker, Untitled, Ink on paper, 14.0 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Eventually, when he began to paint after seeing the work of a fellow-student at the Madras Christian College School, he maintains the attempt to employ intimate knowledge of landscape (especially Kerala, in his case) and an emotional connection with them as essential frameworks for a modern art, whatever its claims for technical achievement may be: ‘Canals used to make me highly emotional. And my eyes used at such times to fill with tears. Feelings that this was unmanly, I was at pains to hide the tears from others quickly wiping them off. I began to paint continuously from then onwards. Initially, these depicted canals, coconut groves, and paddy fields. And this work could be done alone, without the supervision of anyone else. And I could get immersed in such work. And it was much better than spinning out heroic tales. It used to give me similar self-confidence and was of equal attractiveness.’

|

K. C. S. Paniker, The Edge of the Canal, Malabar, Oil on board, 1953, 19.2 x 25.0 in. Collection: DAG |

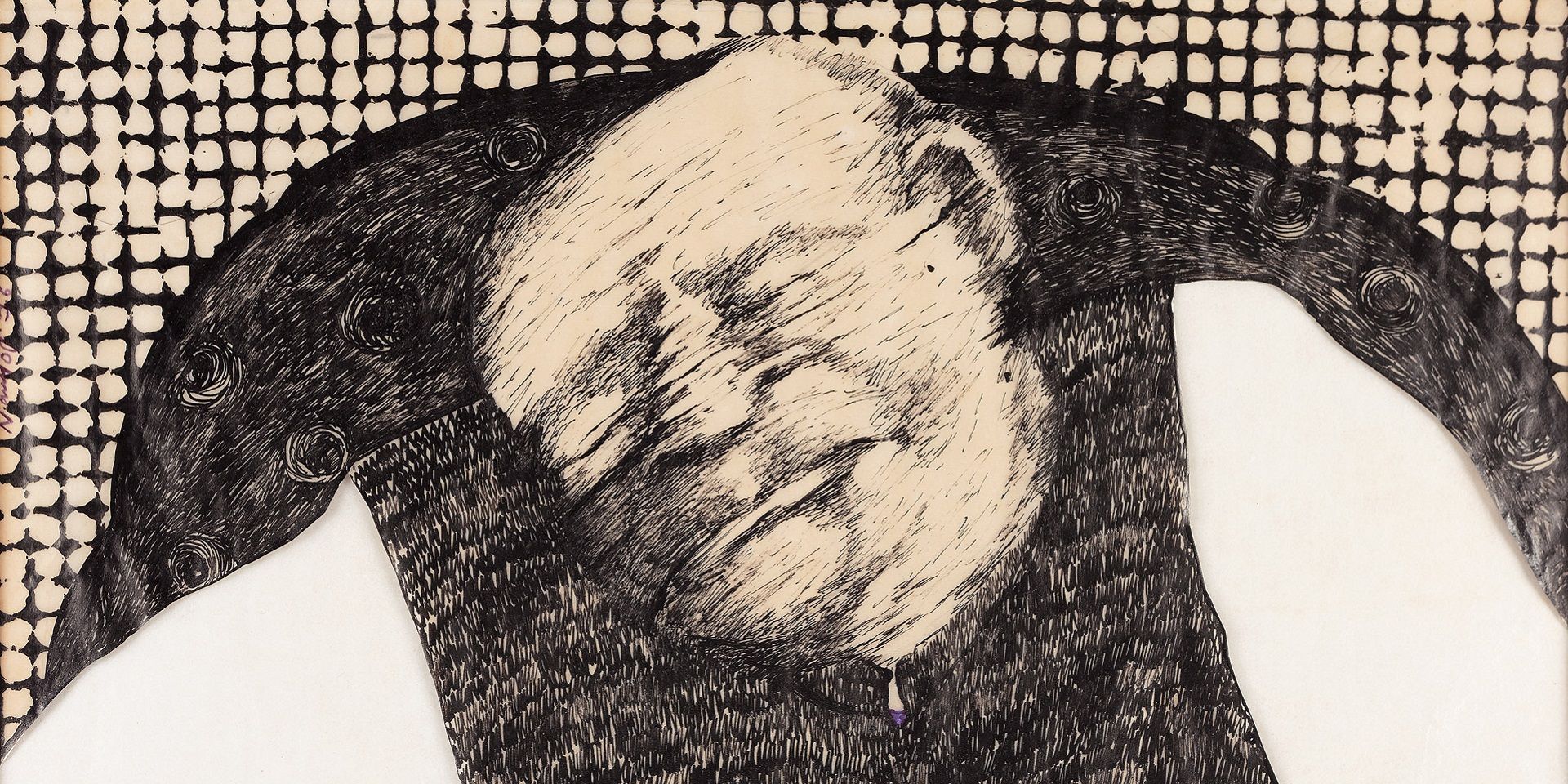

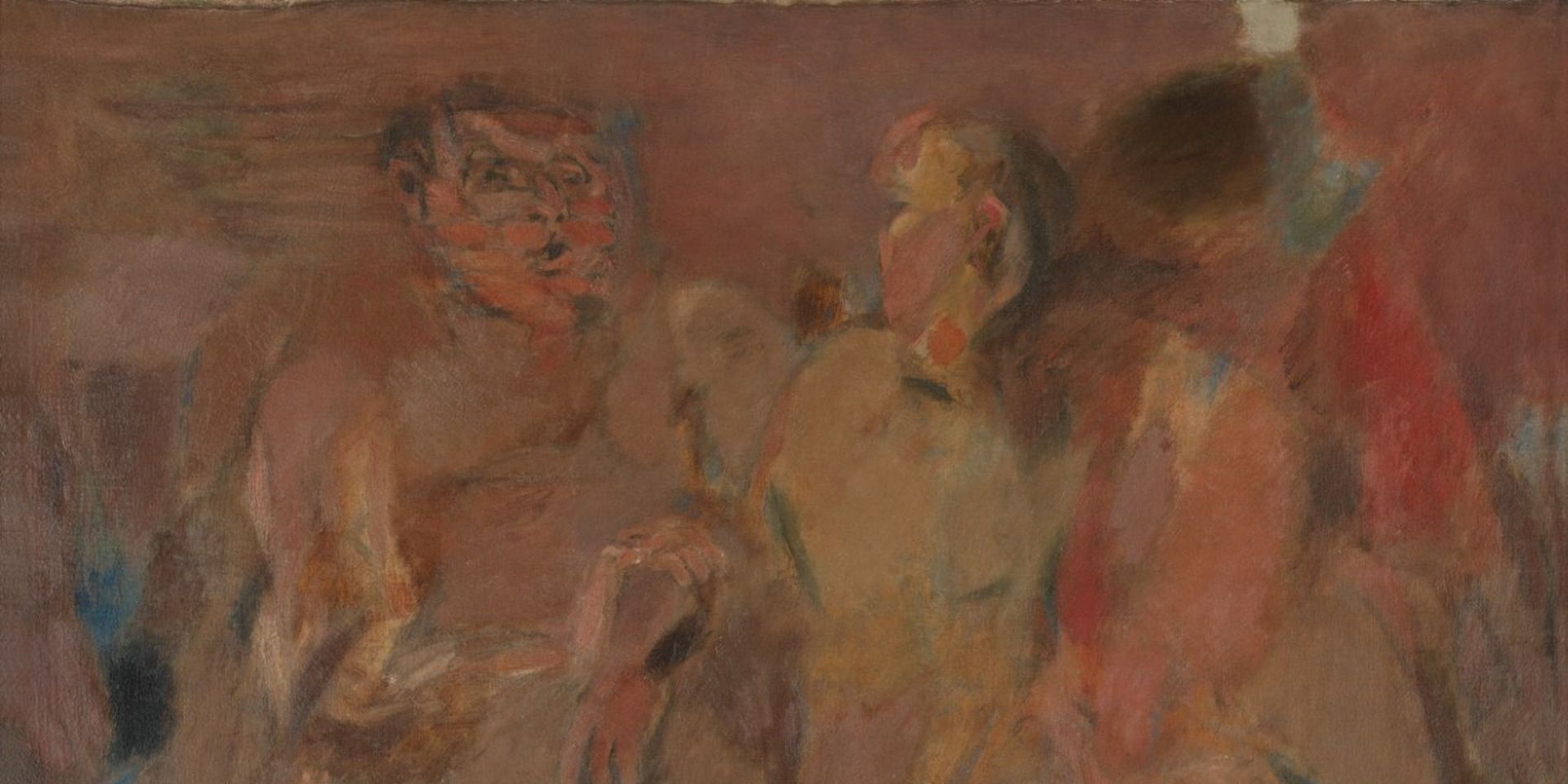

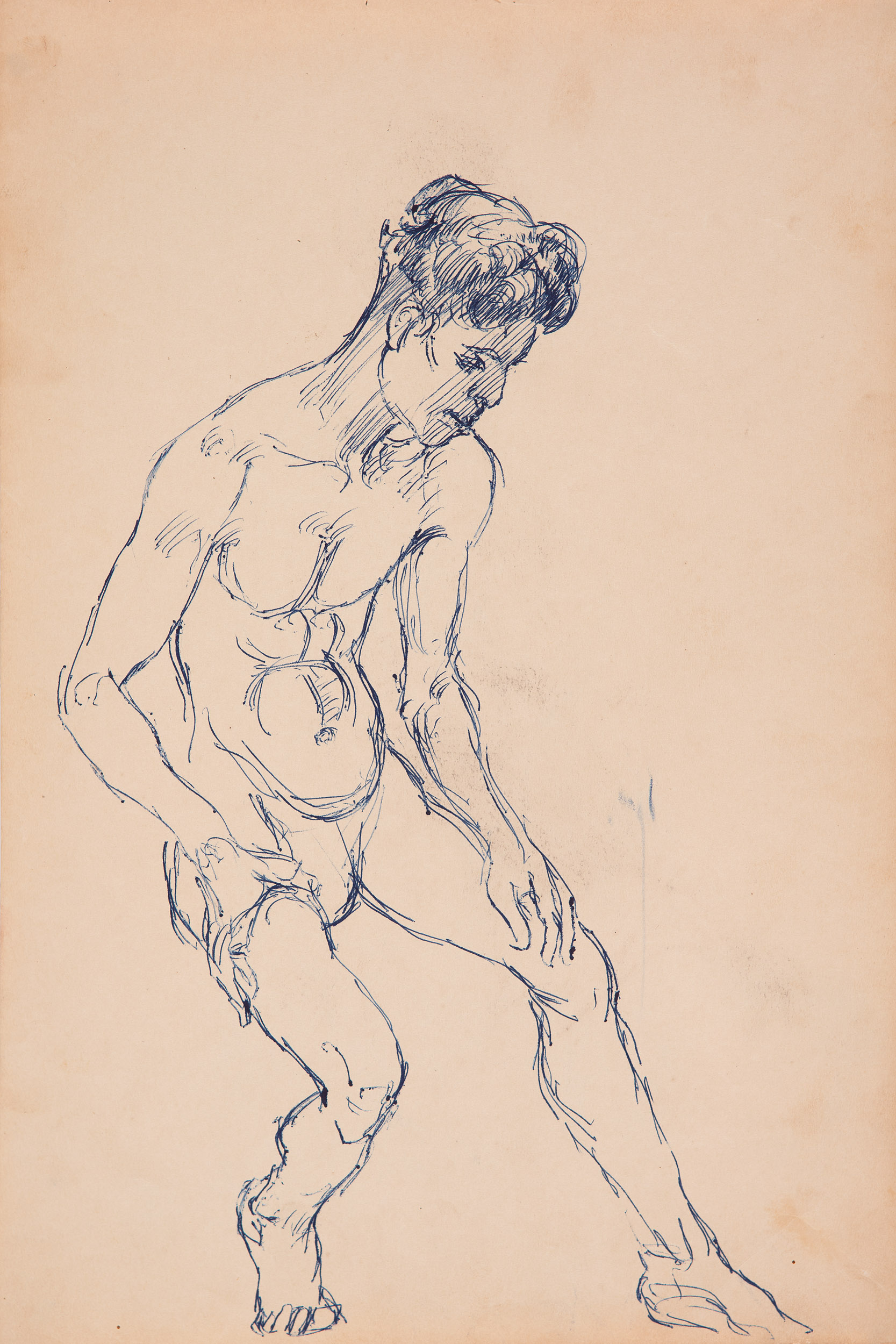

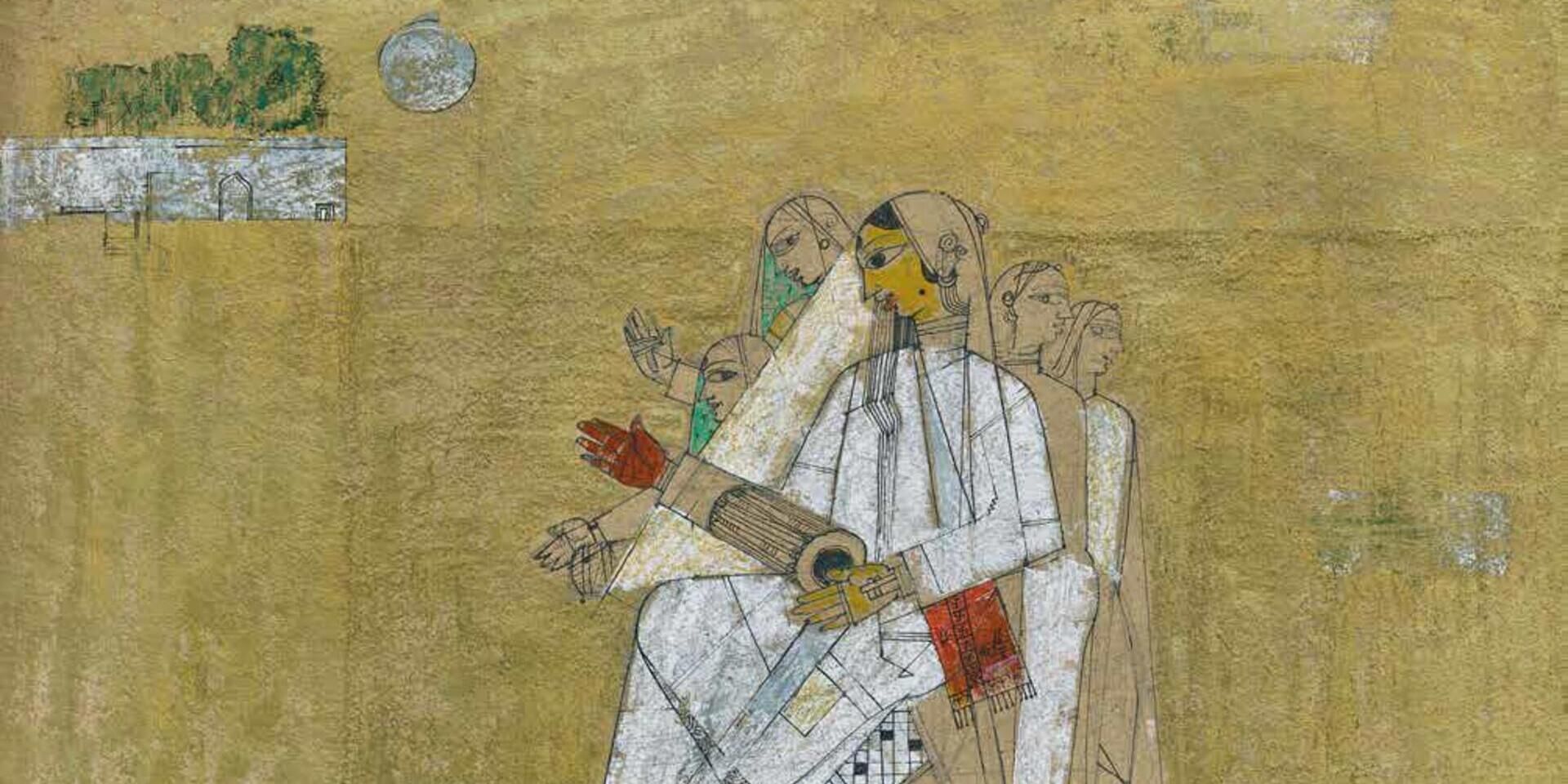

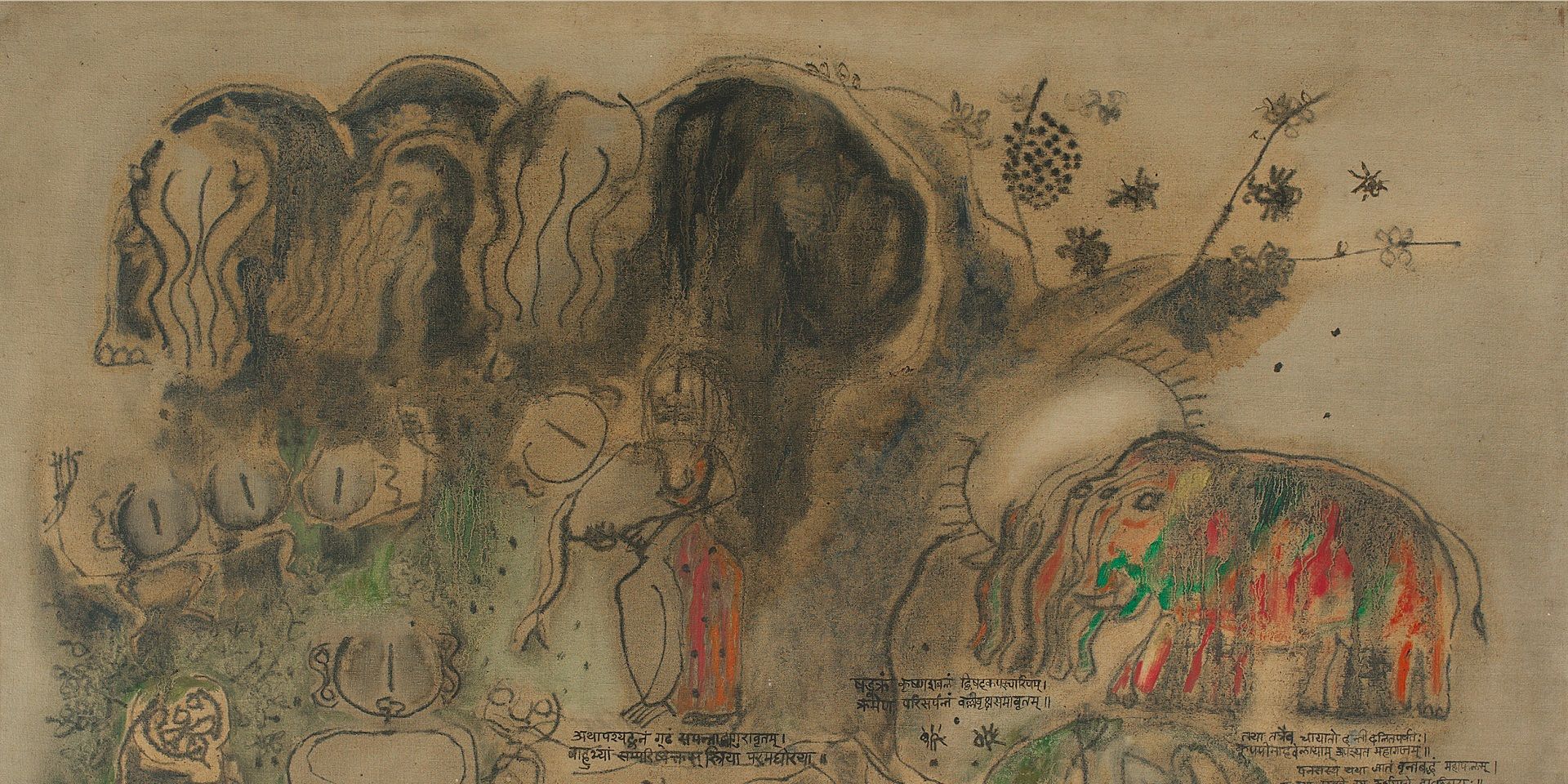

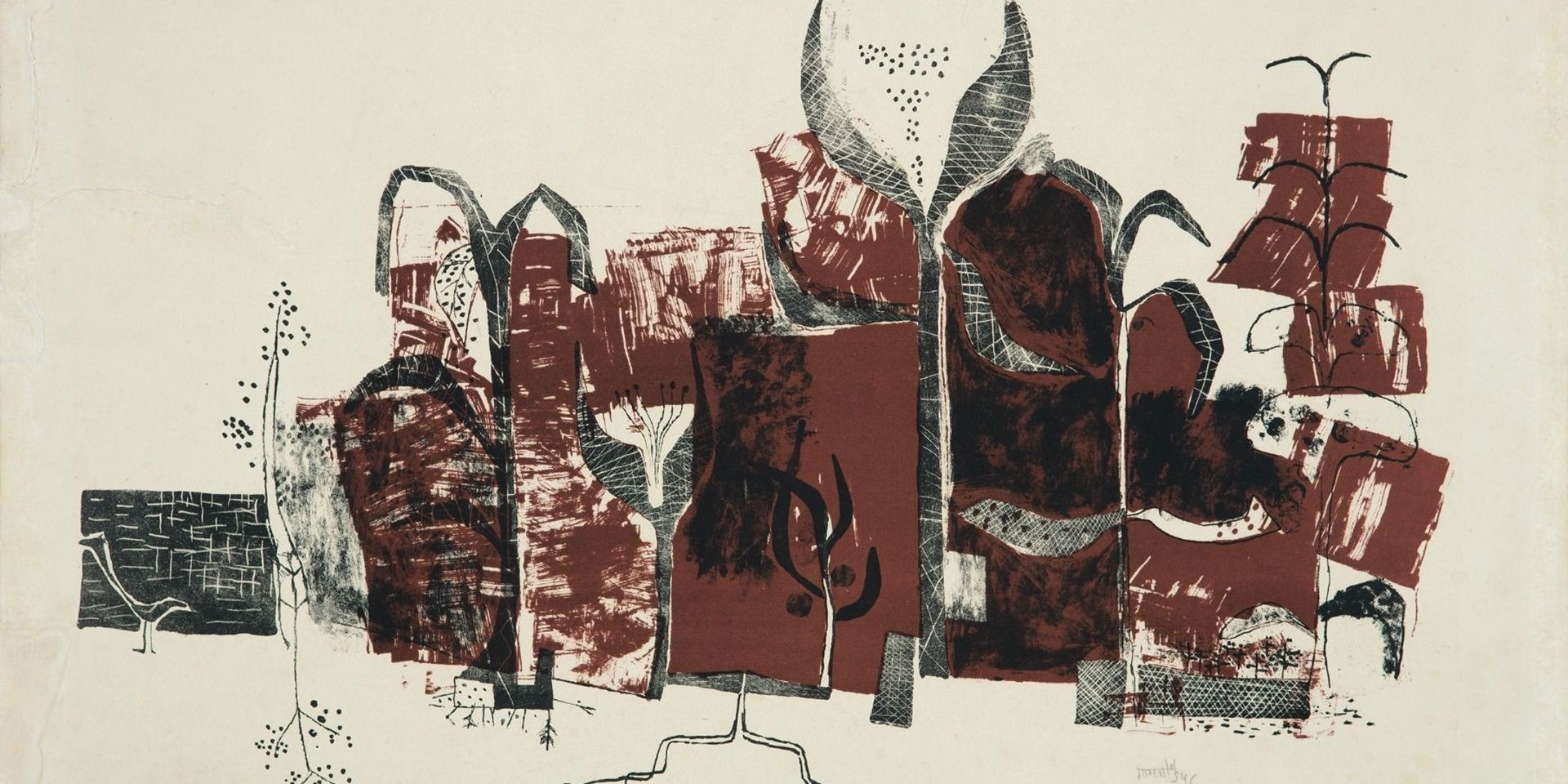

As an artist and educator, Paniker's approach was marked by a shift towards abstraction and symbolism, particularly evident in his renowned Words and Symbols series. In this series, he explored calligraphic styles and fluid designs inspired by traditional art forms, creating a fusion of regional motifs with contemporary artistic expressions. As a critic noted, ‘This grand cognitive sweep encompassing the conception of art as mark-making to construction of signifiers, to conceiving of images, albeit ignoring altogether the representational function of art, makes KCS Paniker a modernist artist with a difference.’ He also continued to make rich studies of anatomy and human forms till late into his teaching career as he innovated new ways to teach figure drawing to his students. He emphasised observation of daily life too, and told his son Nandgopal, ‘Unless you can draw what is in front of you how it is (sic) possible to draw from imagination’. According to the painter Vasudev, ‘while academic naturalism was insisted upon in Bombay by making copies of the classical sculpture plaster casts, here in Madras, Paniker would instigate us to distort, make it abnormal or stylise the human model studies away from realistic representation, and it is this artistic directive which made an impact on the minds of his young students’.

|

K. C. S. Paniker, Untitled, Ink on paper, 14.5 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Paniker's works exemplify his innovative approach, characterised by simplified forms, distortion of proportion, and a unique blend of indigenous and modern artistic elements. As Rebecca Brown points out, ‘Paniker resisted banishing the Indian visual past from scientific and national progress and also refused to see the past as holding all the answers to the present.’

K. C. S. Paniker, The Foot Bridge, Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 1950, 15.5 x 16.7 in. Collection: DAG

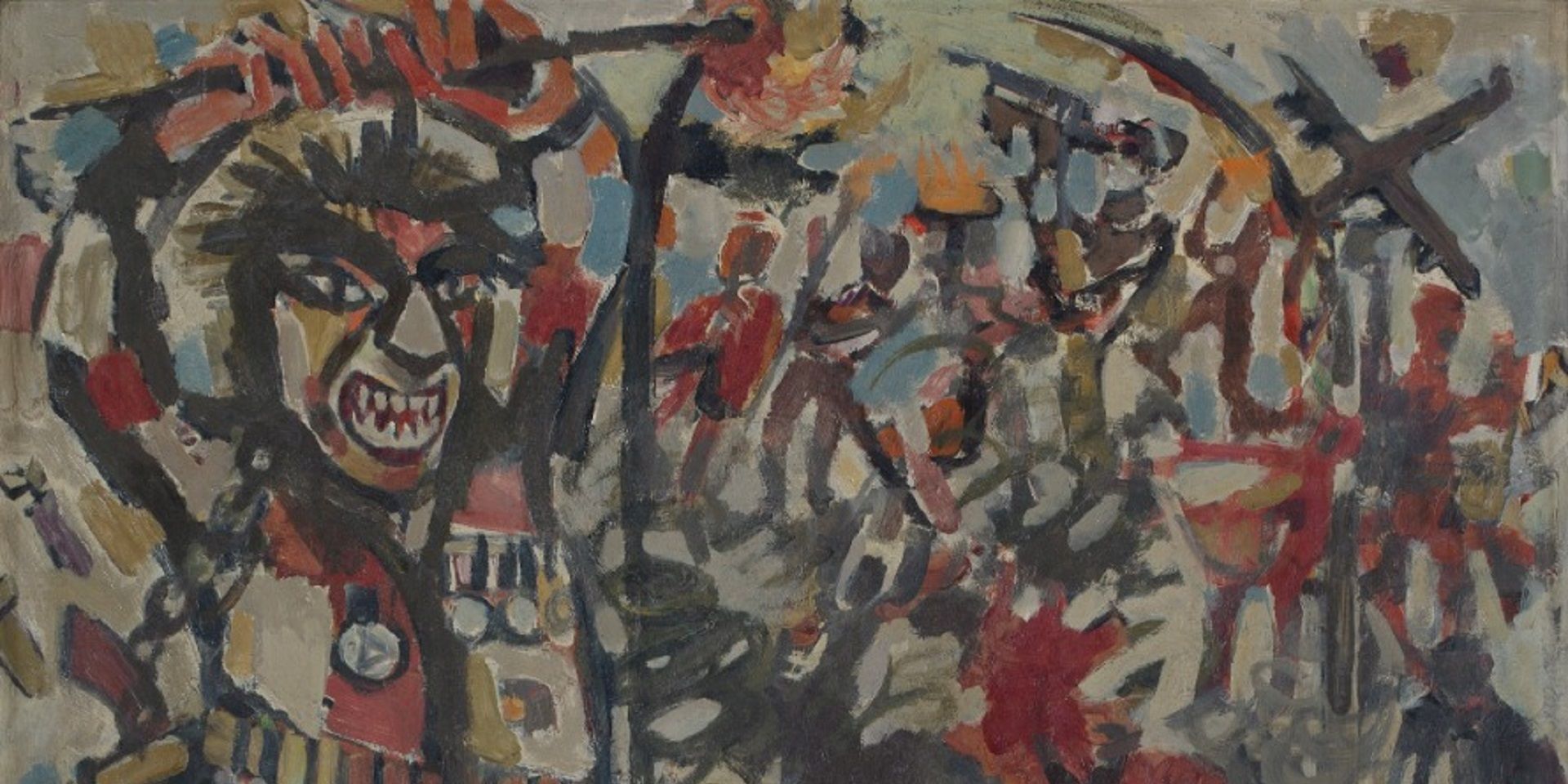

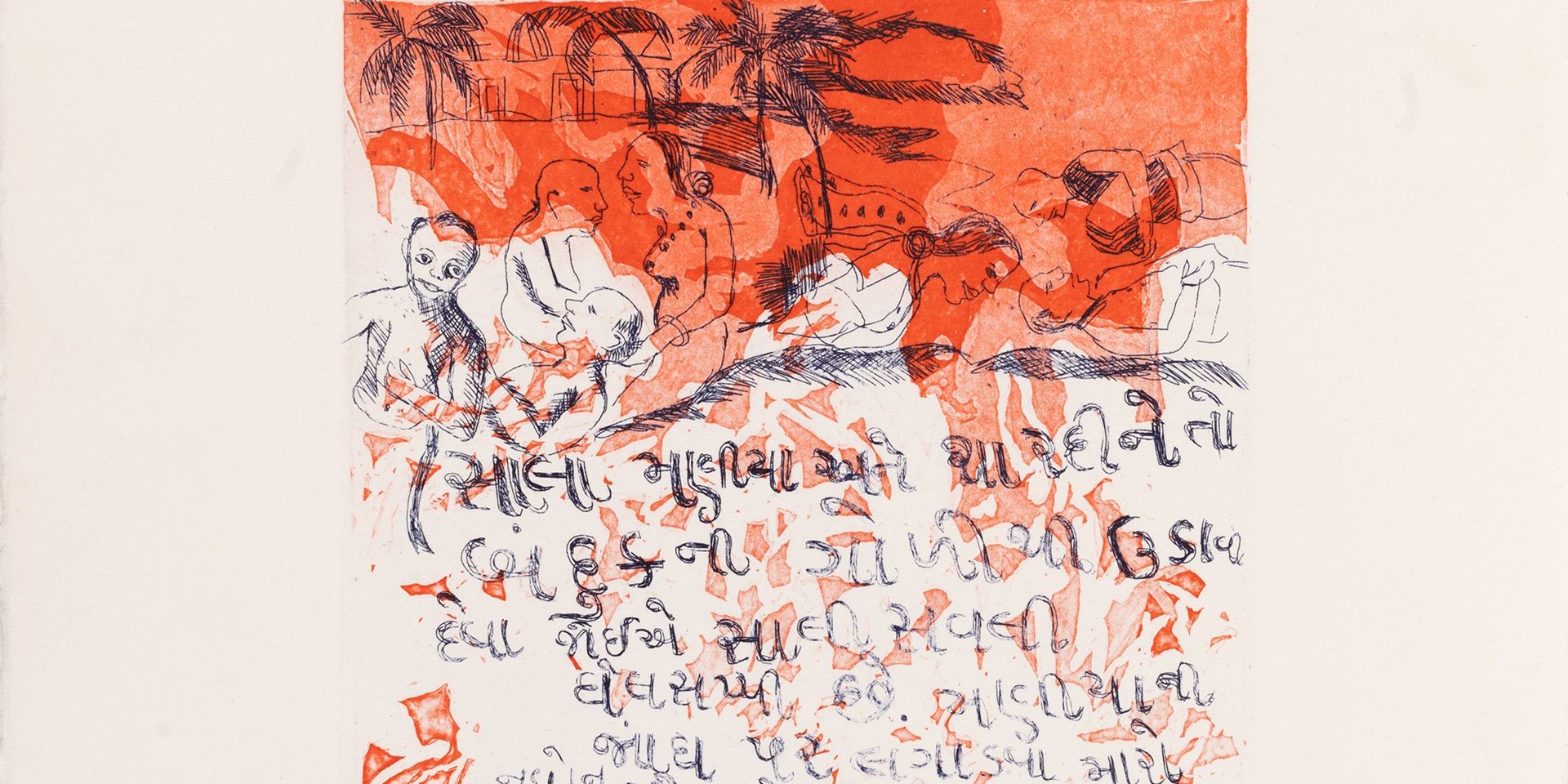

Paniker's legacy as an artist and educator in the Madras Art Movement is defined by his commitment to exploring and redefining regional artistic traditions, fostering a culturally rooted Modernism that resonated both locally and internationally. It was in order to implicate the regional traditions of art that he began to incorporate decorative elements, text and symbols from Kerala’s architectural and sacred histories. During an early exhibition at London in 1954, the art critic Ludwig Goldscheider castigated his work for not being authentically ‘Indian’ enough. Paniker took this criticism seriously and it led to his search for finding ways to make work that was more rooted in his soil. It must also be remembered, however, that western critics and educators of the time tended to valorise the primitive, the artist who was untouched by the baneful effects of western academic training, even as Indian artists held ambivalent feelings at the time about committing to alternative paradigms of art and its influence on their own commercial prospects. Goldscheider would write to him, ‘You are one of the very few Indian painters who went through the ordeal of Western teaching and came out unbroken.’ Thus, it is important to note that even in Paniker’s role as a pedagogue later on, he would try to unwork some of the dustier, mechanical tendencies of an art education that sought to either formalise traditional arts and crafts education or displace them altogether. He introduced several craft and pictorial modules, including a batik workshop, to forge these indigenous connections for his students. It should also be pointed out that his art did not translate into a simple parochial hankering after authenticity—as he was committed to a larger decolonial process. His painting of a familiar scene from the war between the United States of America and Vietnam shows his feeling for the atrocious napalm-bombing campaign carried out by the Americans that affected children and burnt forests to the ground.

|

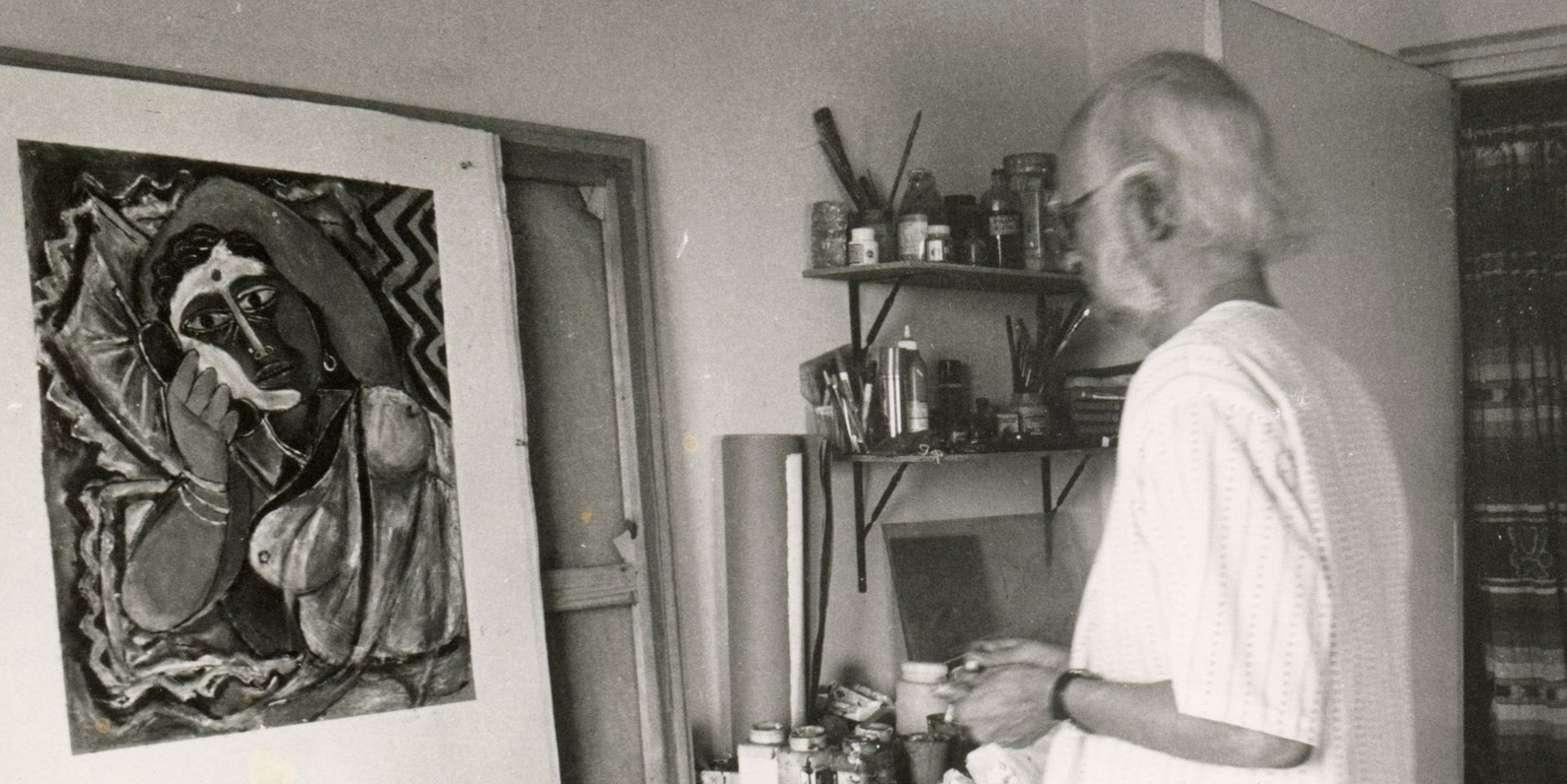

K. C. S. Paniker |

Paniker remained optimistic about the evolving artistic agenda(s) in postcolonial India, saying that ‘Progressive artists of all shades of opinion in India today are convinced that this country is heading towards a vigorous art movement which should develop her national art on modern lines.’ K. C. S. Paniker's contributions to the Madras Art Movement were significant, as he pioneered a unique approach to Modernist art that was deeply rooted in regional identity and traditions. His abstract paintings showcased a fusion of indigenous motifs and contemporary artistic expressions, making him a ‘modernist artist with a difference.’

|

K. C. S. Paniker, Untitled (Still-Life), Oil on ply board, 1954 11.5 x 11.5 in. Collection: DAG |

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

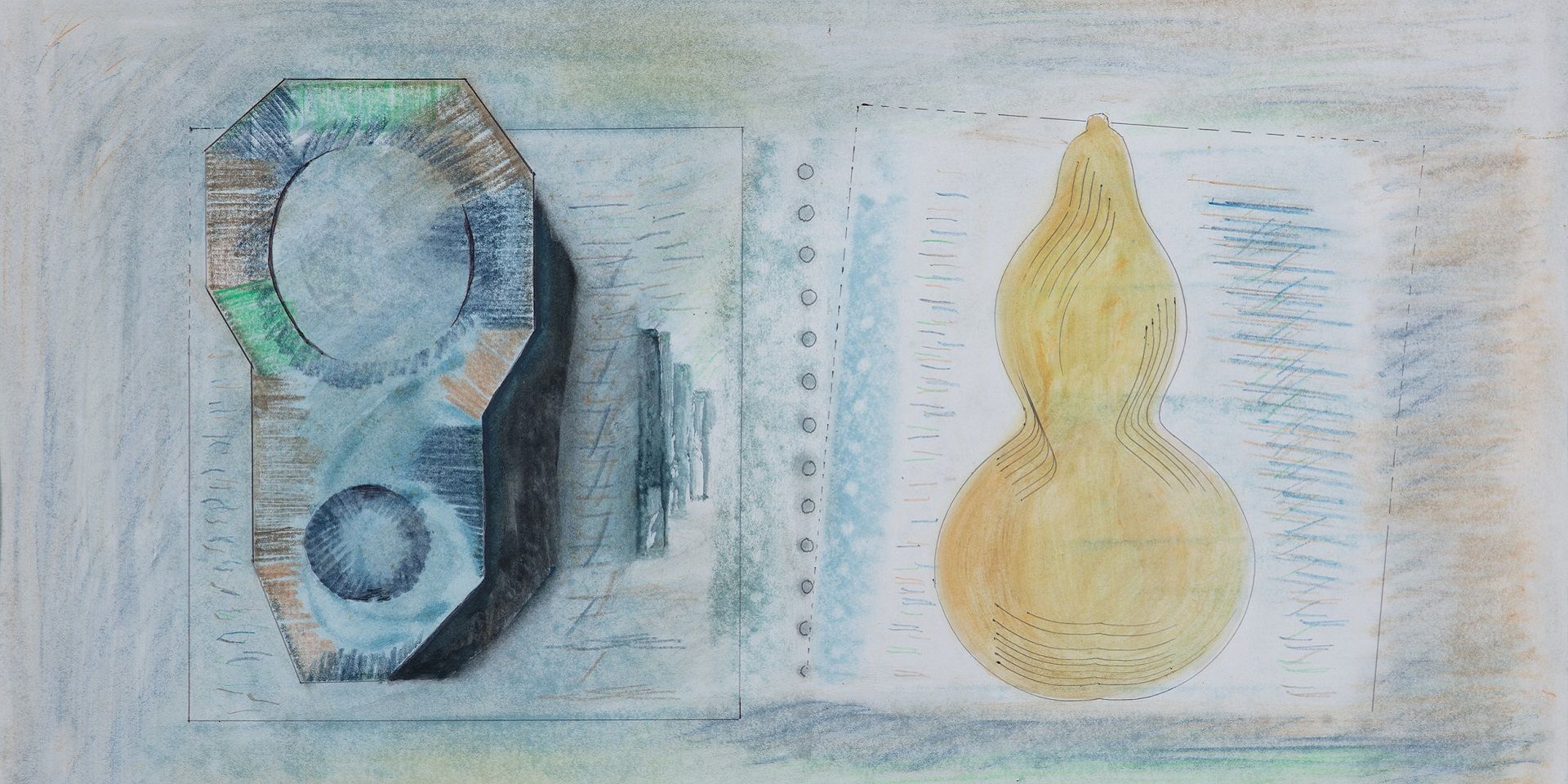

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024