Stepping Stones on the Path to Folk Modernism

Stepping Stones on the Path to Folk Modernism

Stepping Stones on the Path to Folk Modernism

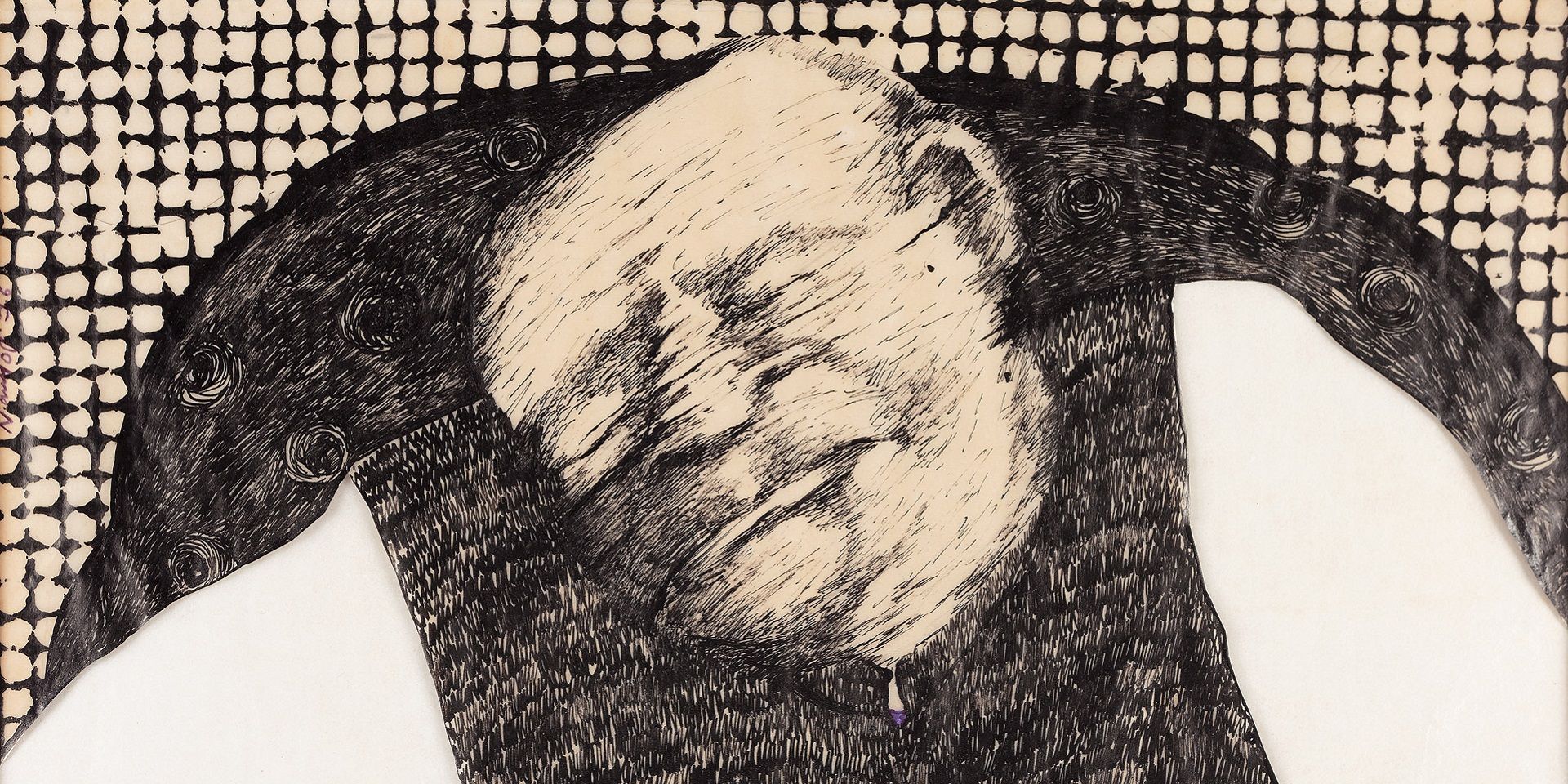

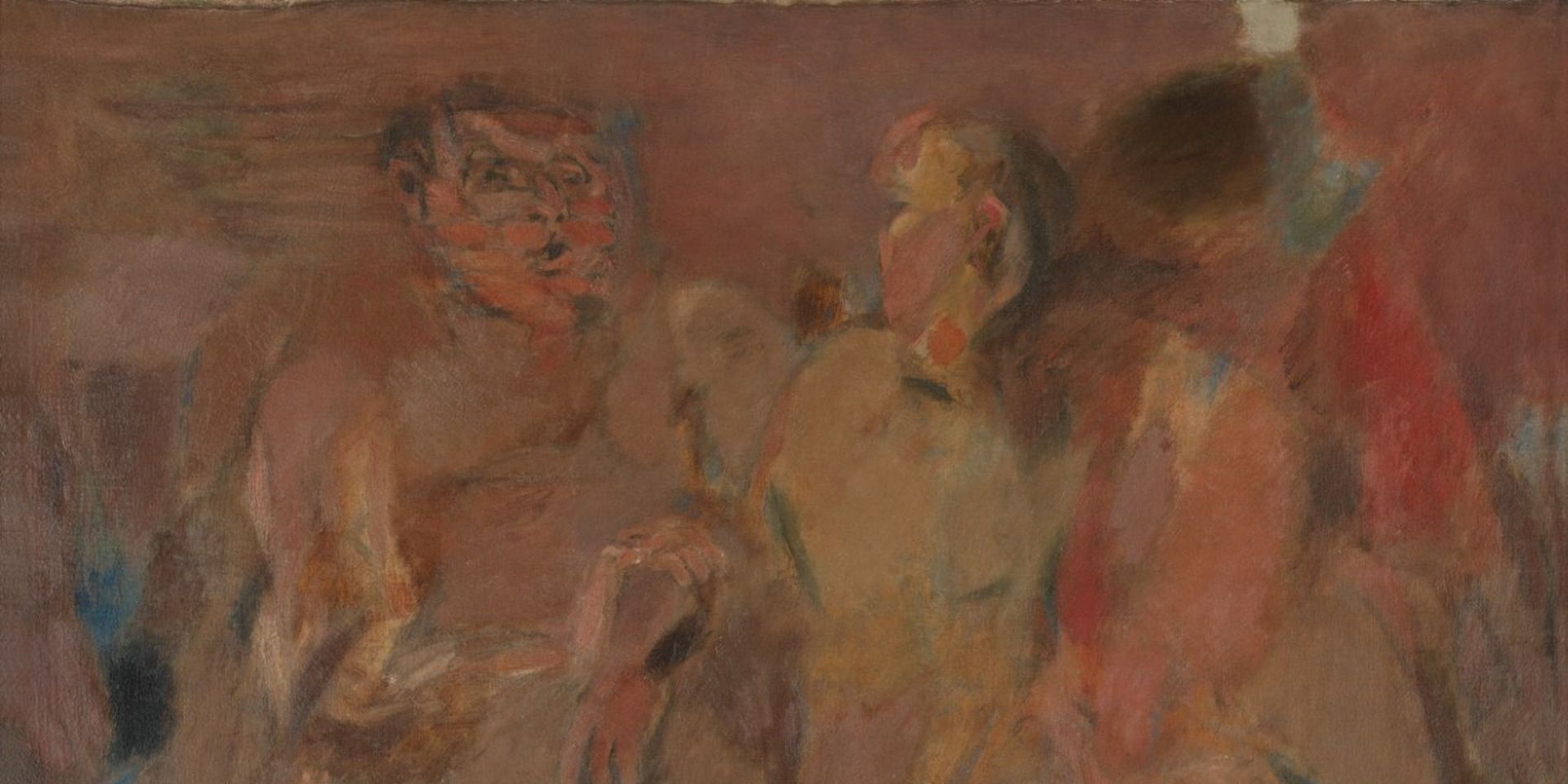

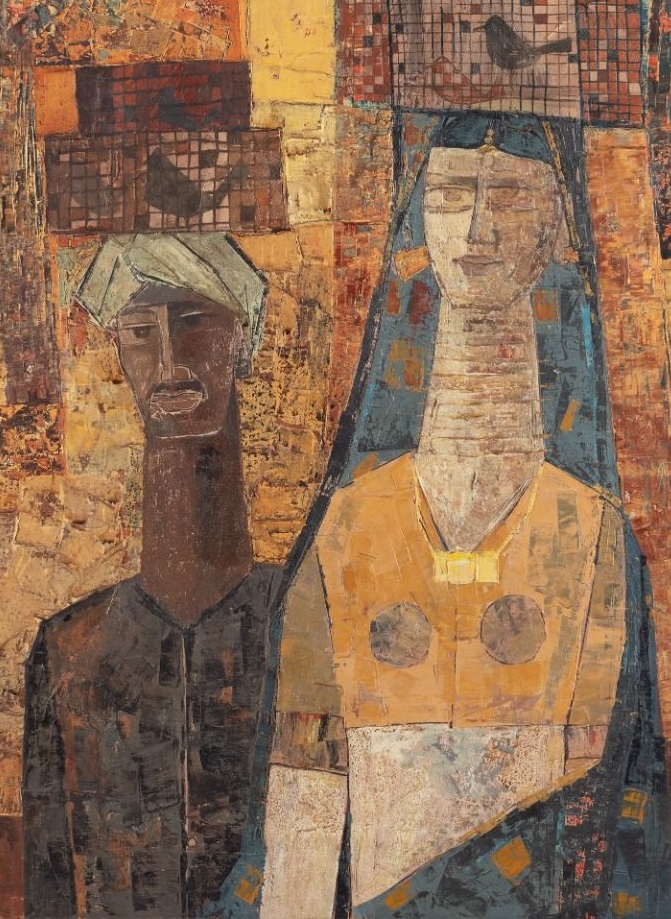

J. Sultan Ali, Muria Maiden (detail), Oil on canvas, 1967, 33.0 x 38.0 in. Collection: DAG

'J. Sultan Ali was decidedly part of the gamut of aesthetic and ideological changes sweeping Indian art mid-twentieth century that would significantly influence the more defined variegated streams it developed into', writes art critic Shruti Parthasarathy. In the essay below, she explores one of Ali's early works, Cage Birds, that marked a departure for the artist into the world of the folk-modern.

Ali is best known as a ‘folk modernist’, not in the mould of the artist best identified by that epithet and for whom it was coined—Jamini Roy—who took a vernacular aesthetic idiom and found a contemporary and ‘modern’ interpretive expression and grammar for it. Instead, Ali was a modernist who responded to key sources and directions in the journey of Indian modernism—tribal and folk art, tantra, écriture. He came to be known for his visually powerful wielding of totemic animal forms, bulls and serpents that were symbolic yet playful, his acumen as a colourist, and for exploration of the lesser-charted of the rasas—bhayanaka, terror.

J. Sultan Ali, Cage Birds, Oil on canvas, 1962, 30.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

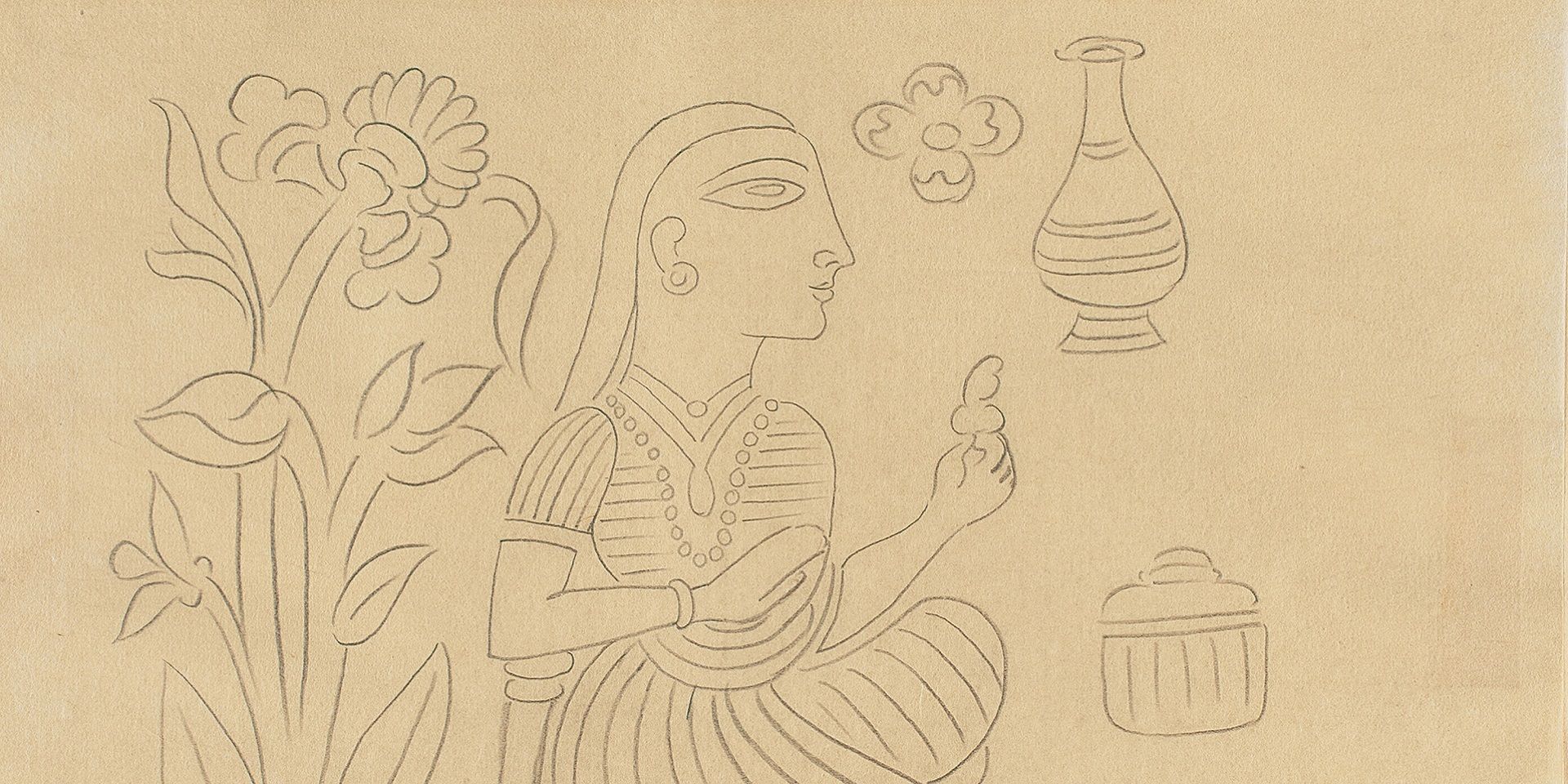

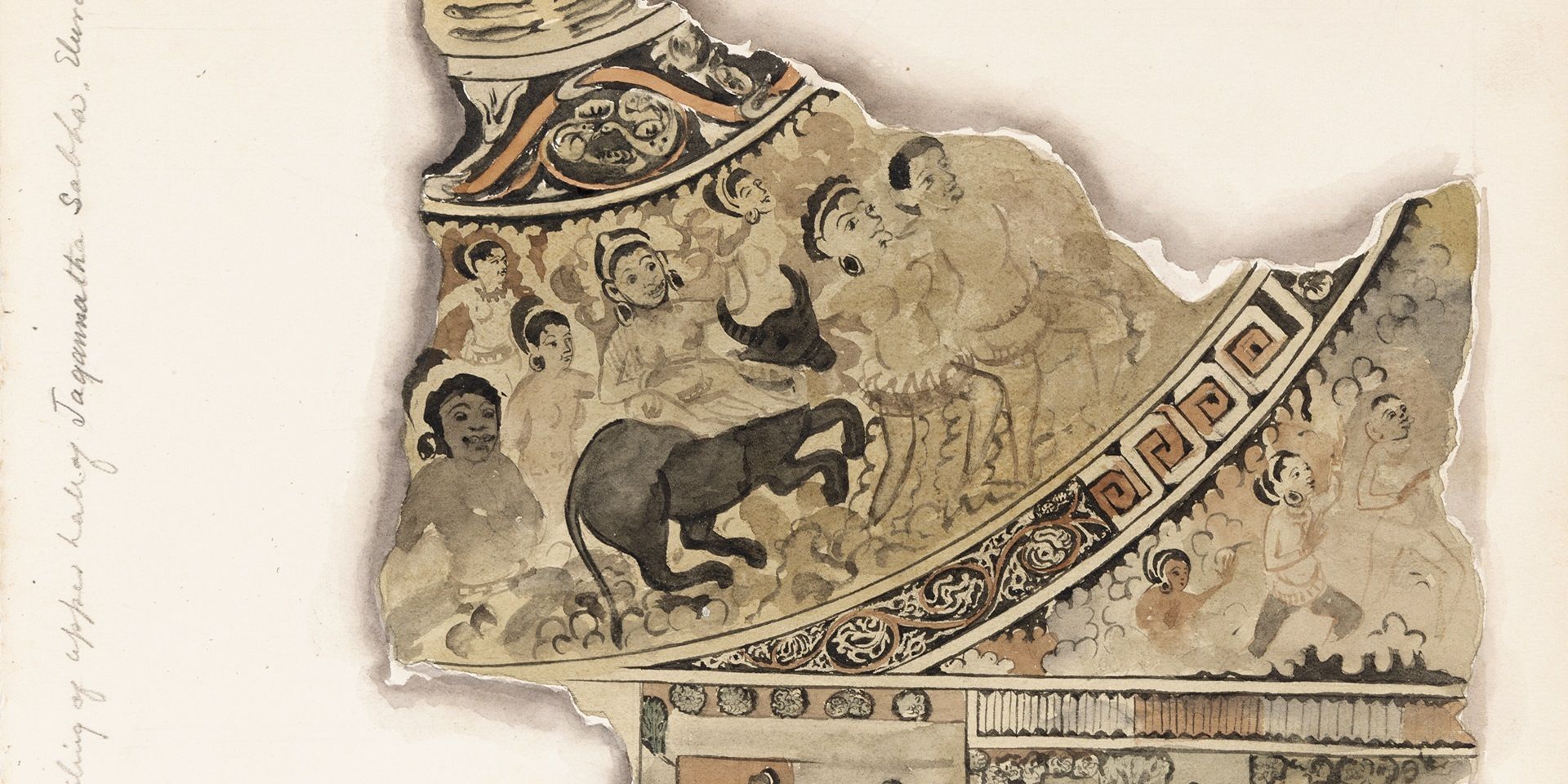

Ali graduated from the Madras colonial art school in 1945; active in the freedom movement, his shift in the early 1950s from academic watercolour landscapes to Buddhist themes came perhaps in response to the call to create an authentic modern art/ language for a new nation. A study of Indian miniatures at Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi, where he had moved in 1954, led to a suite of works adapting the miniature idiom to modernist ends. A noteworthy work from the late 1950s, Travellers (1957) demonstrates his adaptation of miniature painting tropes but in a major inversion, the figures, usually small-to-mid-size within a landscape, were made larger than life, completely dominating the picture plane.

|

J. Sultan Ali, Cage Birds (detail), Oil on canvas, 1962, 30.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG |

The 1960s thrust the ongoing search for an authentic ‘Indian’ modernist expression towards indigenism. It appears to have manifested in Sultan Ali’s works in a move to the rural, recalling perhaps Gandhi’s early-century dictum of ‘India lives in her villages’ asking artists to look to indigenous village-based art traditions. This 1962 oil painting on feature, Cage Birds, represents the brief early 1960s phase of rural themes on the cusp of Ali’s encounter with Indian tribal art via the books of the British priest-turned Gandhian-turned anthropologist, Verrier Elwin, and subsequently, in person—dramatically shifting his art into the world of symbol and numen.

|

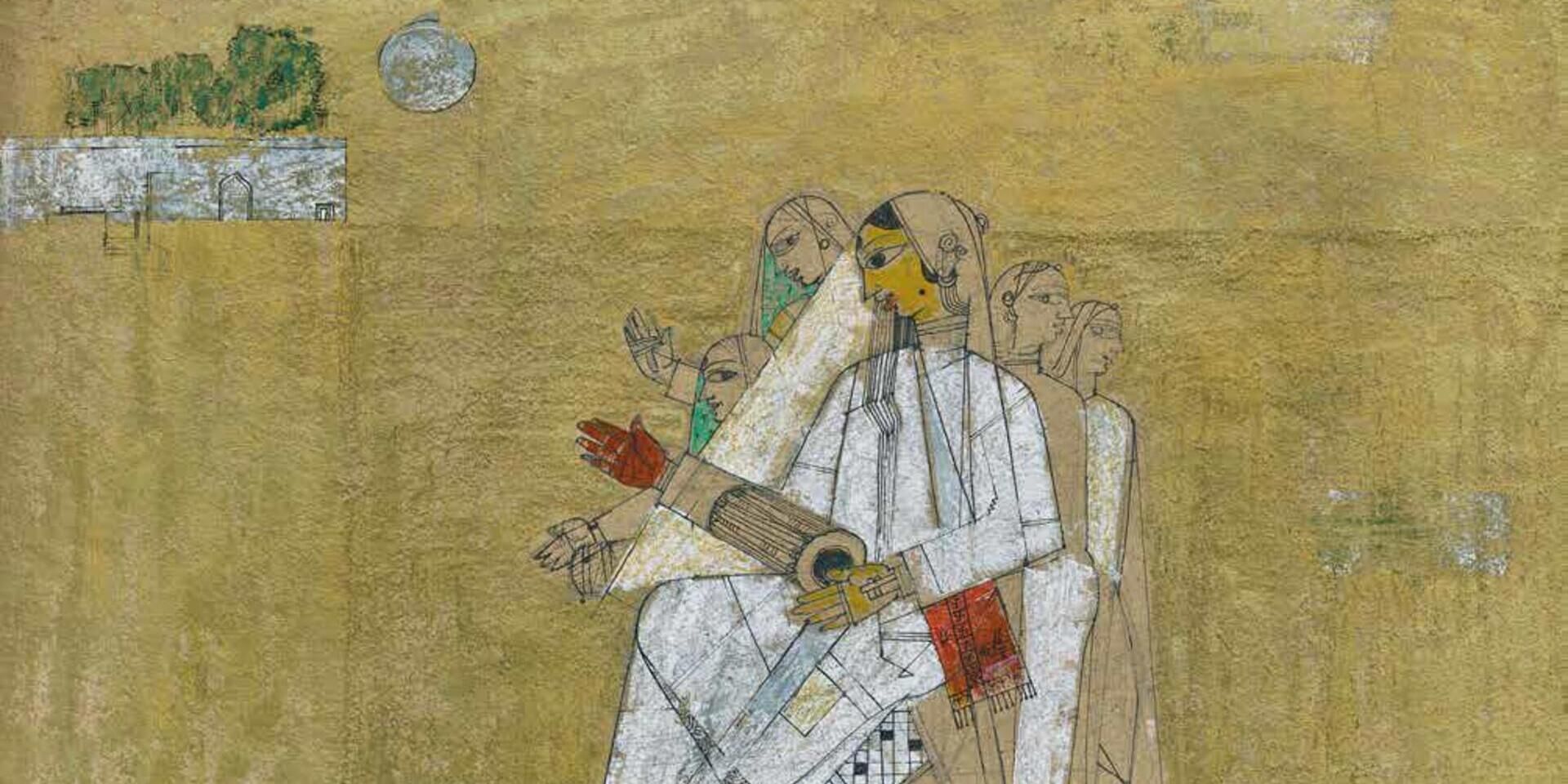

J. Sultan Ali, Milkmaid, Gouache on paper pasted on board, 1958, 17.5 x 14.2 in. Collection: DAG |

The idyllic imaginary of the nayika paintings on themes of beauty, languor, and longing in a bucolic countryside gave way in these works to a harsher rural setting of toil and sun—set in the rural Andhra Pradesh where he had taught children art at the Rishi Valley school a decade prior (1951-54). His lyrical line now changed to a hard-edged, thick-outlined angularity, the forms blocky; he shifted from tempera to oil, and the miniature-staple of the three-quarters profile figure turned fully frontal. In later years, however, post the assurance of his folk-based works, this phase was dismissed as ‘inconsequential’, to be ignored by even as significant a voice as the art critic S. A. Krishnan, a major interlocutor of Ali work’s and his friend.

Instead of examining this work on its own, in something of a vacuum, it would be more fruitful, and fitting, to study it within the larger context of Ali’s art—not entirely free of teleological motivations. Rare is the artist who finds their authentic voice at the outset or overnight; the voice marks an arrival, the road to which is frequently dotted by deviations and divergences, moulded as it is by intuition and accident, experimentation, labour, and time, false starts and missteps; crucially, they provide the artist with the regular practice without which no greatness (or assurance) is reached. Not only must these steps be examined and given their due as stages/experiments that succeeded, failed, or offered discovery, taught the artist what to embrace or avoid; their significance lies, too, in tracing how they might have impacted or shaped the very path they chart.

J. Sultan Ali, Cage Birds (detail), Oil on canvas, 1962, 30.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

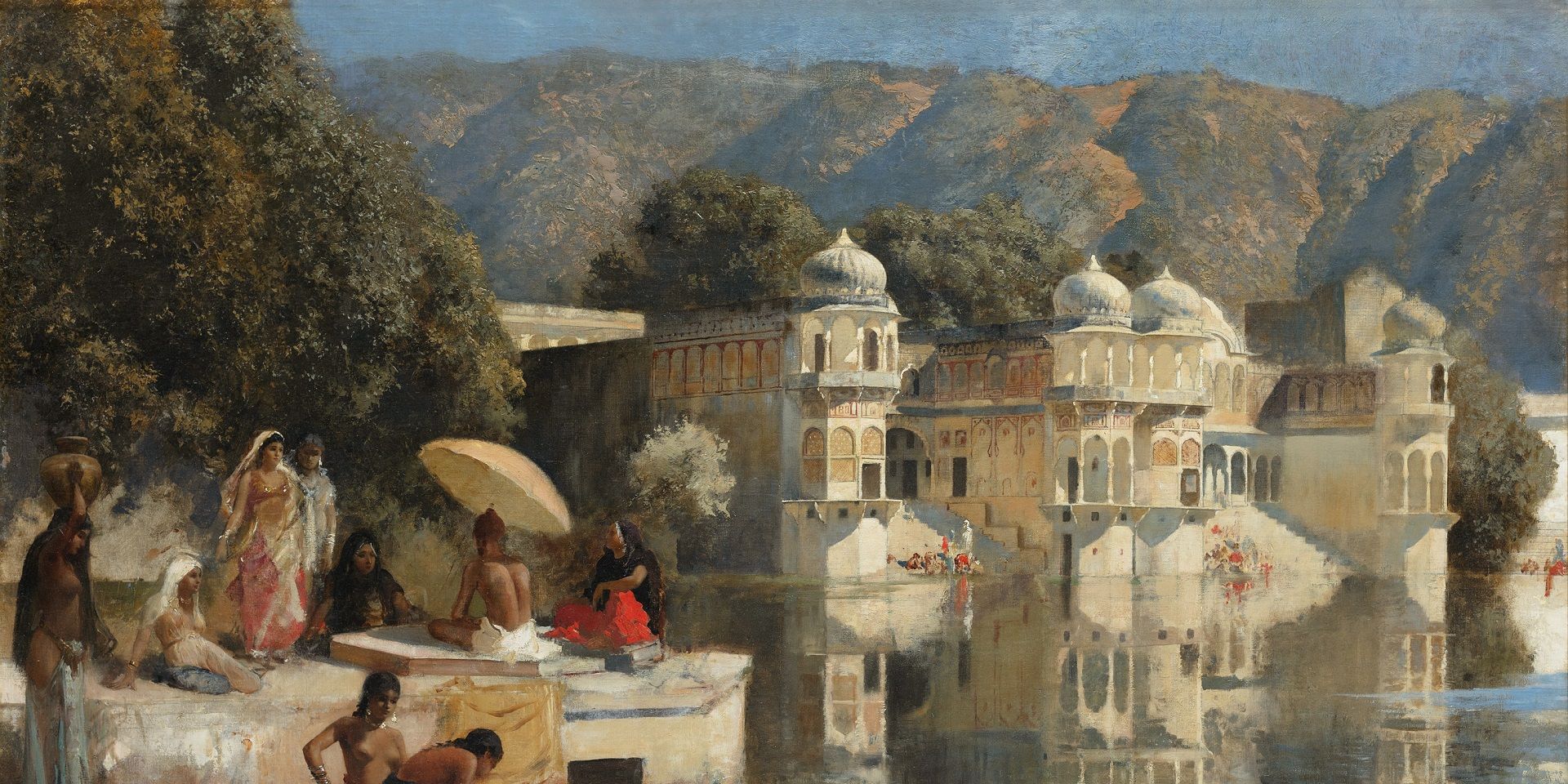

Cage Birds features a woman and a man seen frontally up to their torsos, rendered large against a backdrop of a few trees and carrying upon their heads two bird cages, each with small, captive native birds. They are dressed in recognisably ‘rural’ clothes: the man wears a buttoned, front-open dark blue tunic and grey turban while the woman wears a pale ochre blouse and a loose blue wrap, odhni, with an orange and red angular patchwork-like pattern draped over her head and shoulders and diagonally across her midriff. Their clothing suggests Rajasthan or Gujarat, but the woman’s jewellery, particularly her gold-coloured (likely brass) pendant, signifying her marital status, is distinctly from the Deccan: these figures would likely be from the nomadic Lambadi community in rural Andhra Pradesh, specifically in the Rayalaseema area of the Deccan plateau where the artist would have glimpsed them. Itinerant, the community made their living doing odd rural jobs; the couple here capture and sell birds, perhaps on their way to the nearest small town or big city to sell the birds as pets.

The man is dark-skinned, painted in dark umbers, while the woman is rendered chalky white; their forms are elongated and blocky, with long, clay jar-like necks, and are painted to suggest generic types rather than individuals. The woman, seen here in her rural environment—with small, rounded breasts, brings to mind the rural women working in urban construction projects in the 1950s painted by artists such as B. C. Sanyal or K. K. Hebbar. Complementing her wrap’s patchwork pattern and striking blue hue within the work’s overall muted palette is the backdrop of trees flecked with reds, ochres, and blue-greens which, together with the angular ochre blocks of the rocky ground sloping up against the dark dirt road, seem bejewelled. This is augmented by the small checked pattern of the cage wires framing the birds and the ochre band running horizontally behind.

|

J. Sultan Ali, Muria Maiden, Oil on canvas, 1967, 33.0 x 38.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Another 1962 oil, Old Shepherd is similar in its compositional structure and surface treatment, with a more realistic figural rendering. Thin and long-torsoed, an old man and a young woman in Lambadi clothes, likely his daughter, occupy the foreground vertically from the centre to the right half. They are framed against a centrally placed bullock in a field and a horizontal strip of distant houses in the upper register, while the blocky stones and boulders build up the earth surface vertically from the bullock in the middle ground marking the Deccan plateau’s rocky outcrop.

Ali made a small number of works in this style and it becomes apparent the figures are not rural protagonists seen at their tasks or amidst their life but present as freeze frames and vignettes of outdoor rural life, which remains merely the backdrop. Boasting attractive colour schema, the works seem decorative figural studies—frontal, somewhat flatly rendered, and stiffly posed figures framed against woods or village houses—becoming snapshots of village life/folk for the passing urban visitor (including the artist) driving by; the stiffness could indicate being met with curious stares.

|

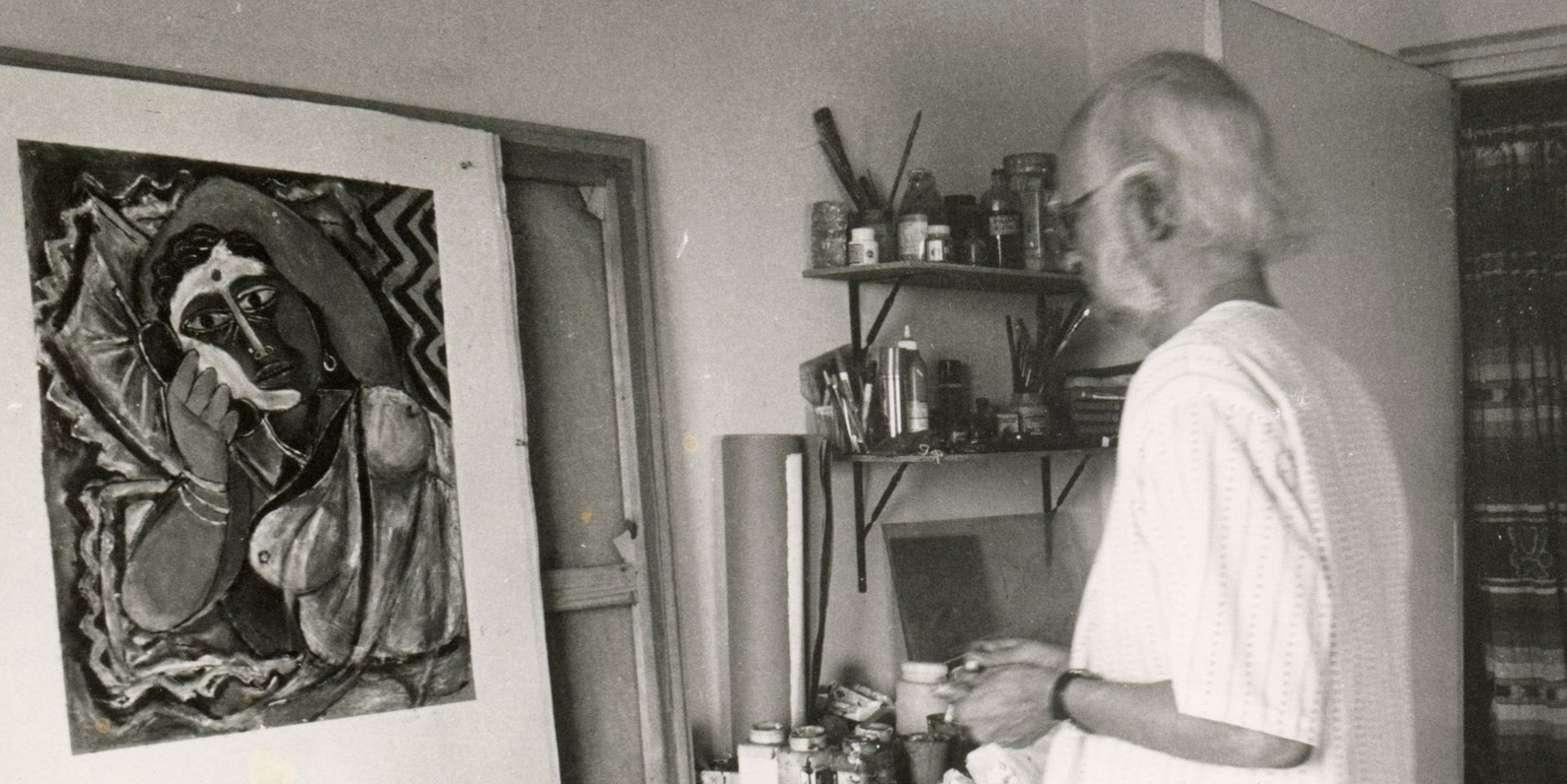

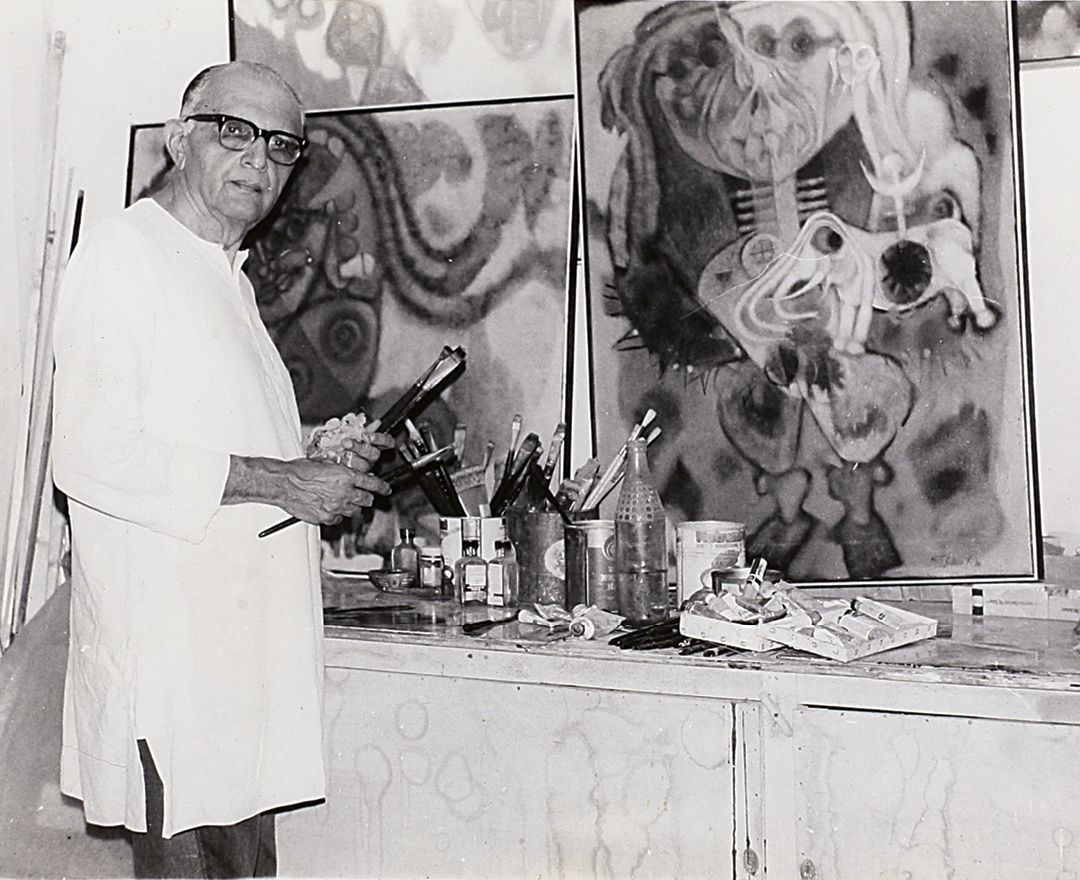

J. Sultan Ali in his studio. Photograph : DAG |

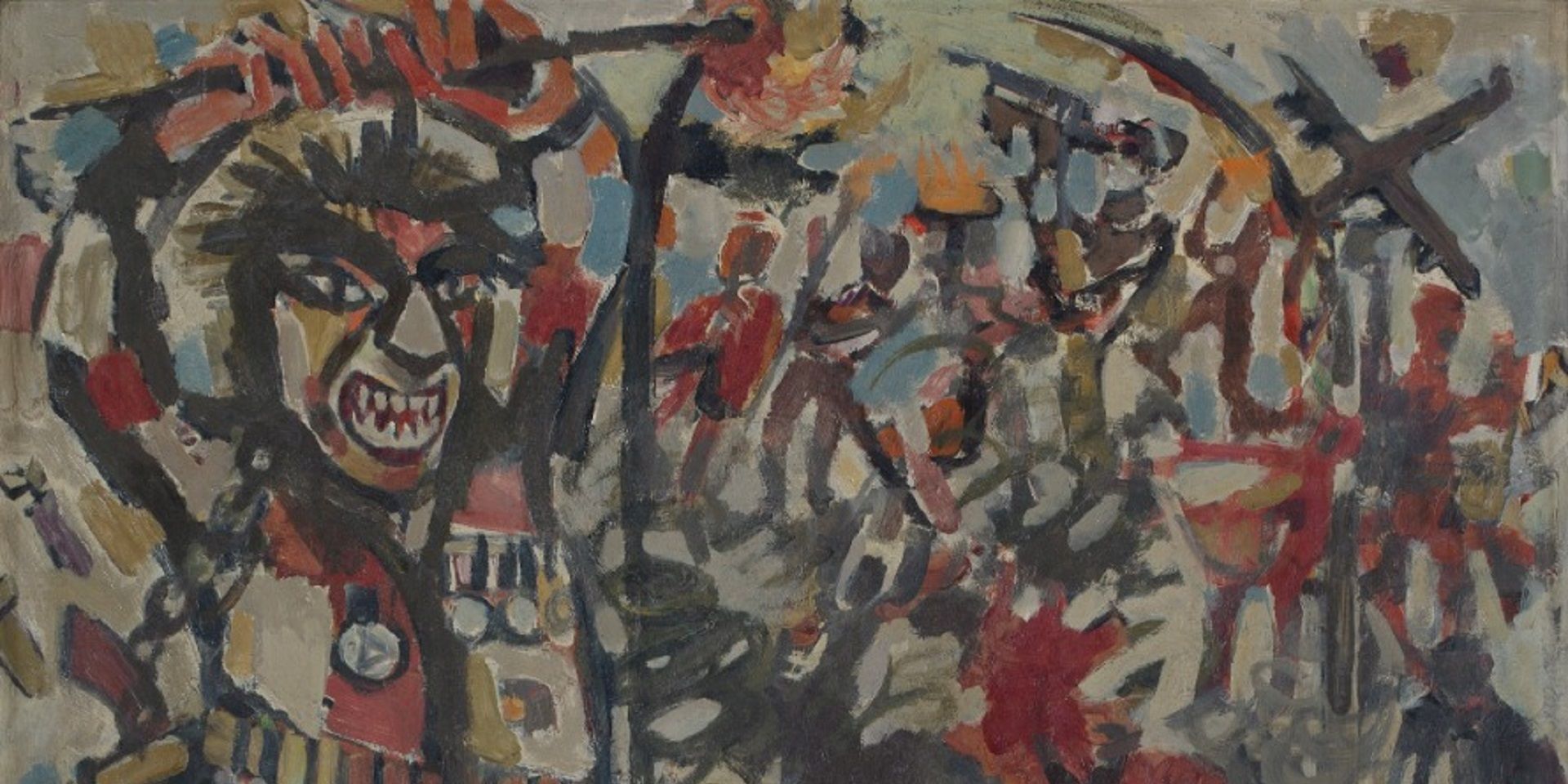

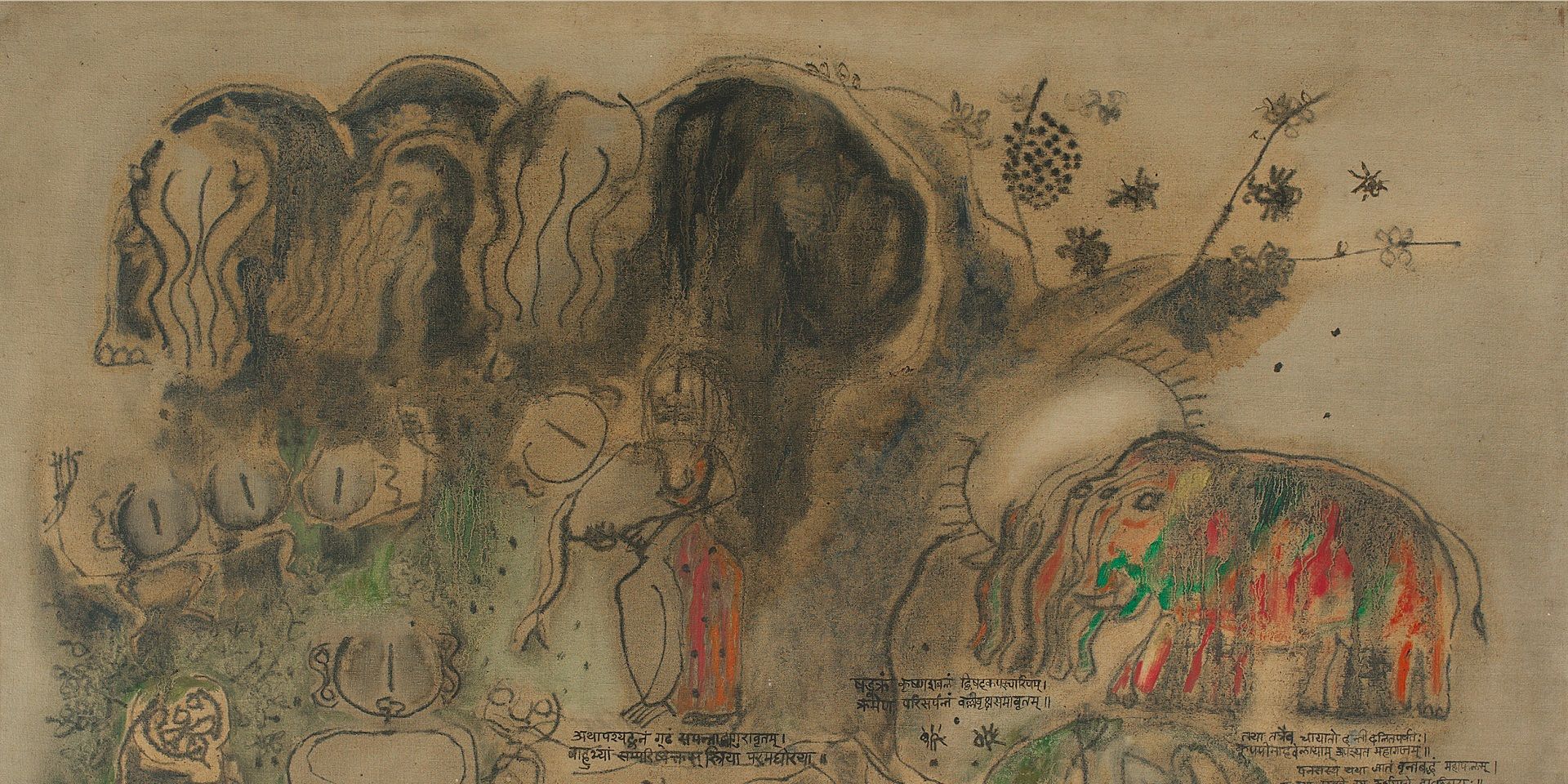

Over the next couple of years, Ali’s subject matter remained rural but the surroundings grew bare and the figures abstracted, though still vertically elongated and looming over the composition—exemplified by the 1964 works, Fisherwoman and The Watercarriers. It is at this stage that the encounter with tribal art manifests in a dramatic change in composition and surface treatment: first seen in the arresting 1965 Festival Bull or Nandi from Devanahalli (1966). The human figure is replaced by the animal, frequently the bull and, in the 1970s, the serpent takes centre stage and expands to nearly fill the picture plane with a majestic presence; the pigment is now applied thinner and boasts a highly assured and subtle use of colour. This new, centrally-placed looming figure also appeared in a few intriguing, assuredly rendered 1963 works featuring fine markmaking and symbology, as Penance or Sea Life, now in major institutional collections.

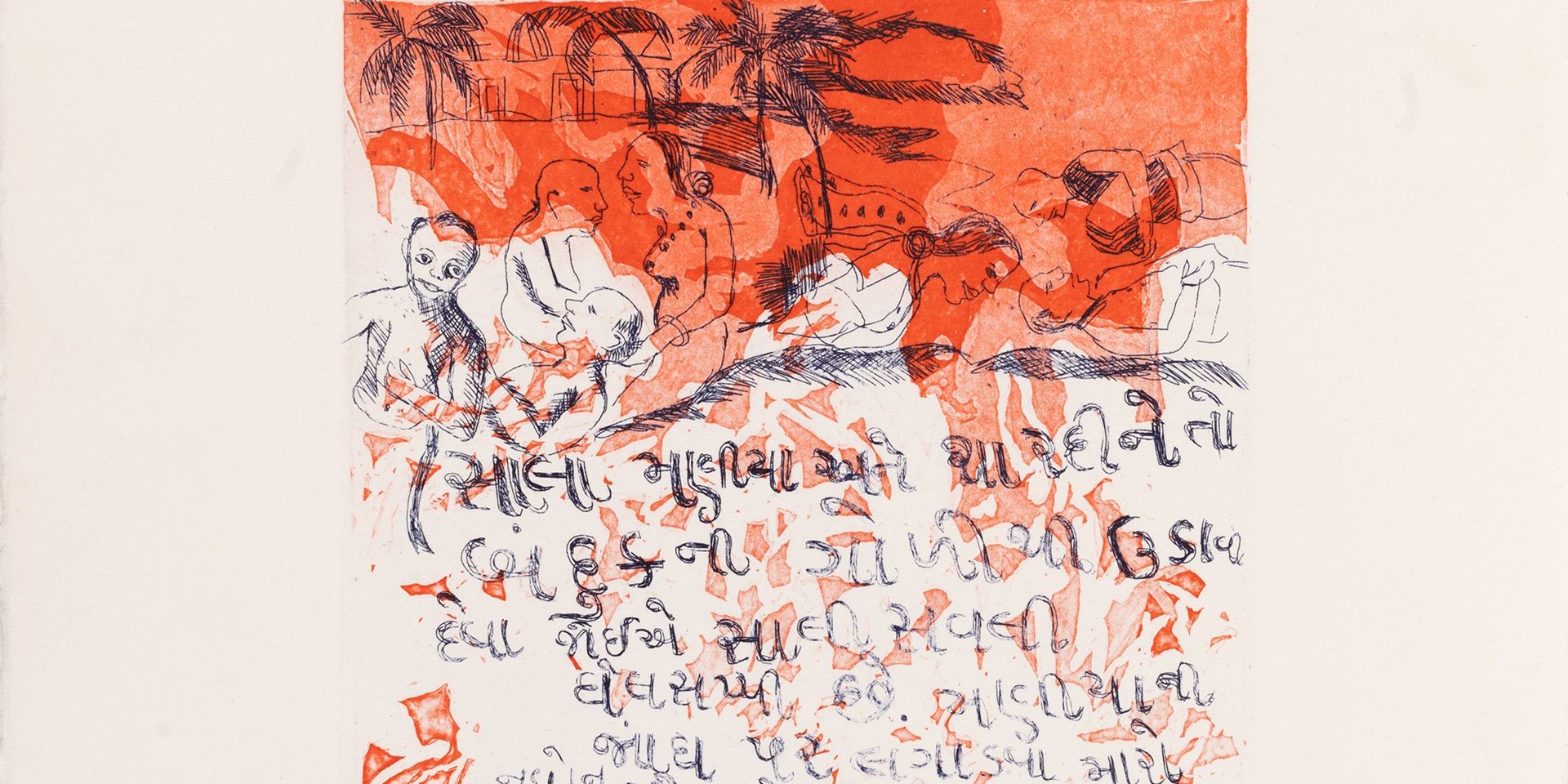

Over the next few years, the late 1960s and ’70s, manifold changes sweep over Sultan Ali’s work but with the noteworthy presence of the figure: it remains and is dominant, frequently central. A lone female tribal figure reappeared in the early 1970s: either clothed, more blockily rendered and small-breasted, standing totemically, or a sensuously drawn, realistic one with a bare upper body, her skin a rich brown and ornamented with the jewellery and tattoos of the Murias and Baiga tribes of central India; or further, an abstracted, phallically-rendered totemic mother goddess seen in Tribal Myth or the national award-winning Hassia Matha. Thus rendered variously, she evokes a proto-mother figure suggestive of fertility and life—a rather simplistic connection suggested by a lone, nubile young woman featured with a bull or hooded serpent in the background; see, for instance, Muria Maiden (1967) or Milkmaid (1971). The animal forms are often anthropomorphised, with multiple heads, limbs, or eyes, wearing baring grins, or with multiple plant, animal, and human forms inset within its belly and accompanied by text: Gujarati text and nigari script, initially merely decorative and later intended as decipherable. Well into the late 1970s and ’80s, whether in chromatically rich oil paintings in light-impasto or divergently, in translucent, nebulous forms, still firmly contoured, or in dramatic pen and ink works, as Pakshi, and even in the abstract works, across multiple stylistics, the central/large figure or form remains.

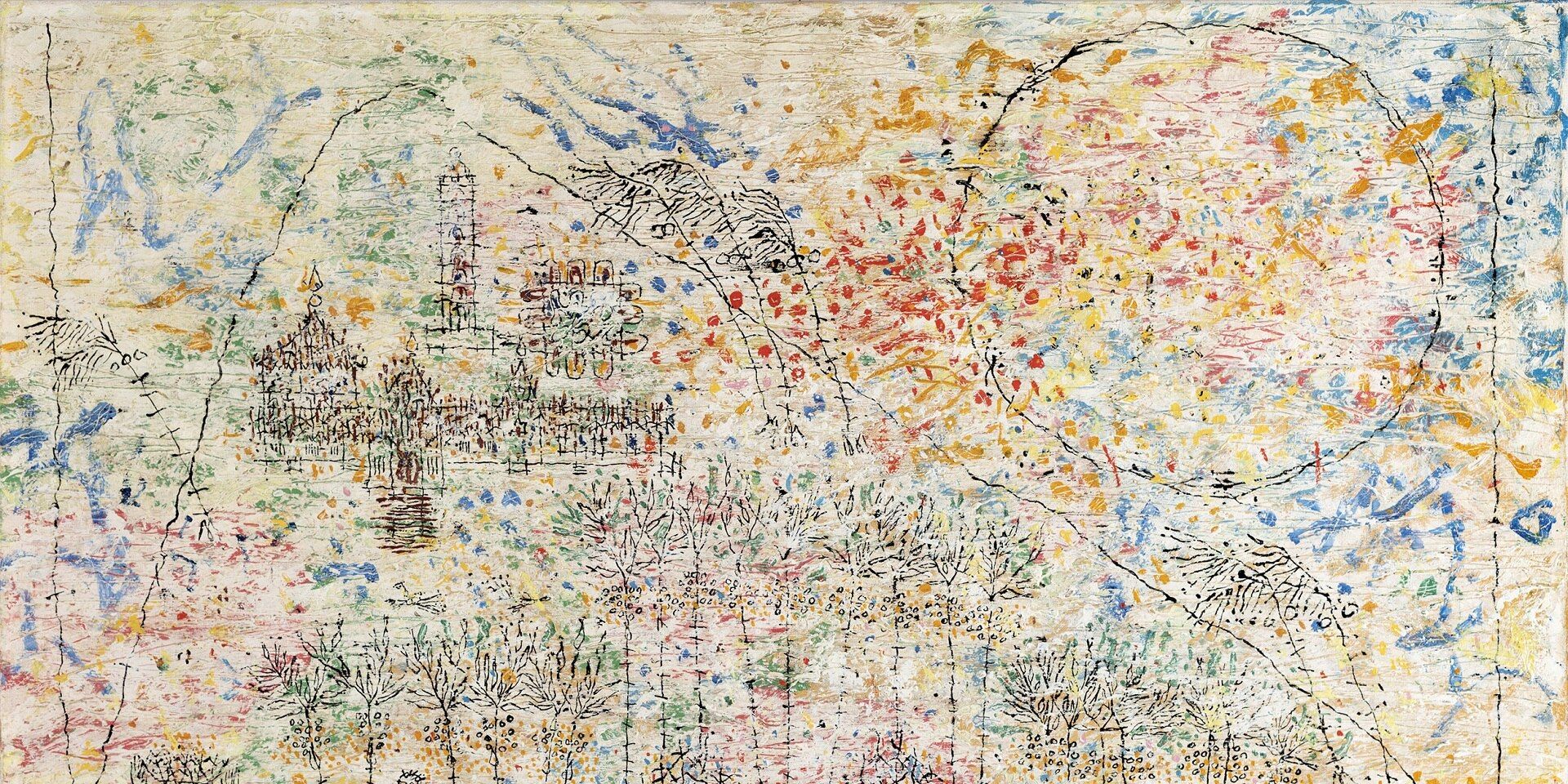

J. Sultan Ali, The First Sin, Oil and encaustic on canvas, 1965, 32.0 x 54.2 in. Collection: DAG

So what is the charm of this large (often central) figure for Sultan Ali, where does it come from? Mumtaz J. Khan, highly respected artist and daughter of J. Sultan Ali, views it as a structural device, with the figure used to anchor the composition. She recollects her father’s visit to Kashmir in the ’60s or ’70s when he was fascinated by the jewellery the women wore and painted them as elongated, vertically placed figures. Citing Sea Life as an example, she speaks of his compositional structure as girded by the ‘main figure’ deriving the main emphasis, and surrounded by all the other elements around.

The early 1960s phase of works which the featured painting belongs to reminds us that no phase of an artist’s work is without value: it brings to Sultan Ali’s subsequent work the pronounced line but most emphatically, the frontal, looming figural protagonist of his art.

related articles

Essays on Art

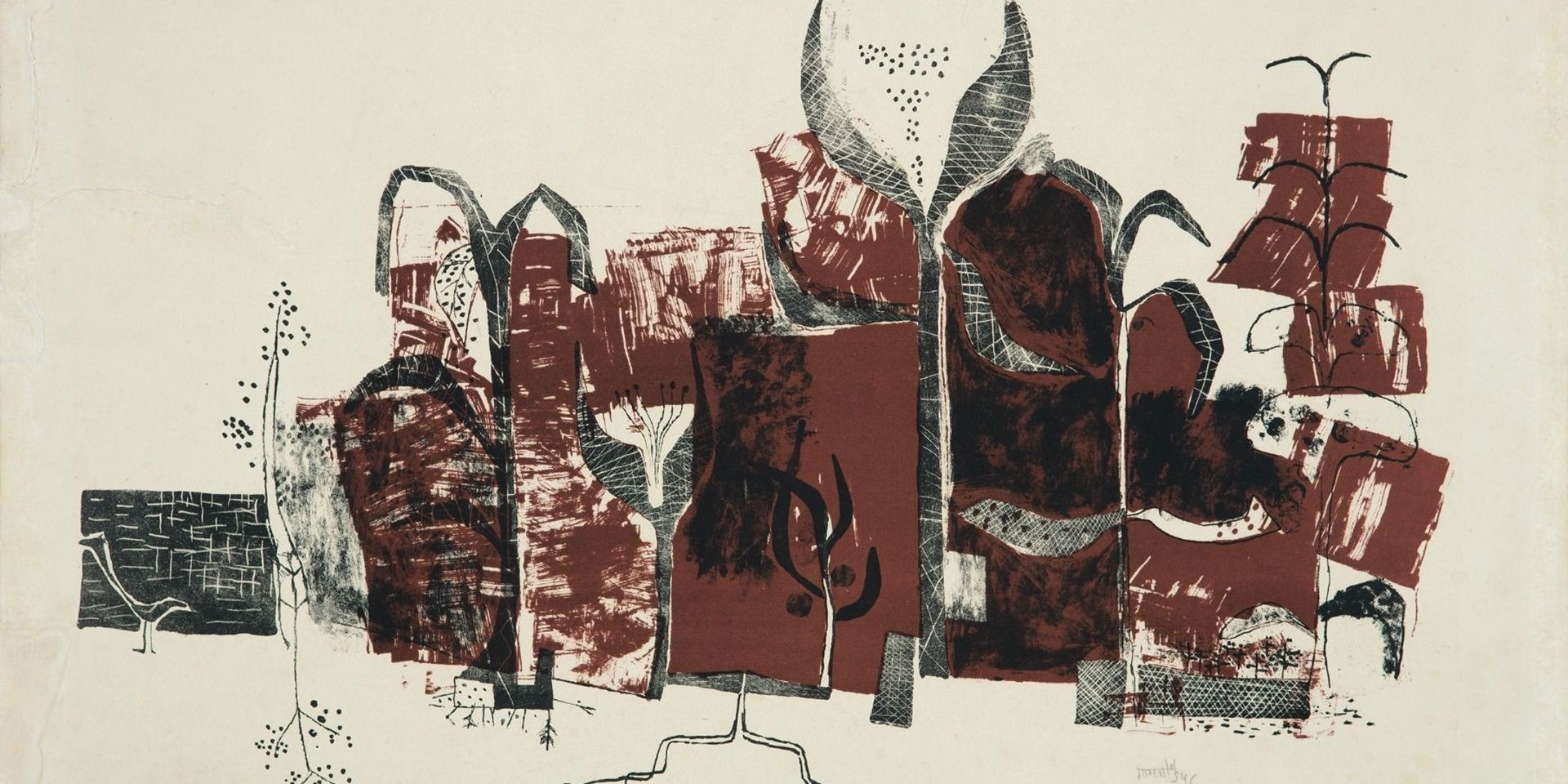

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

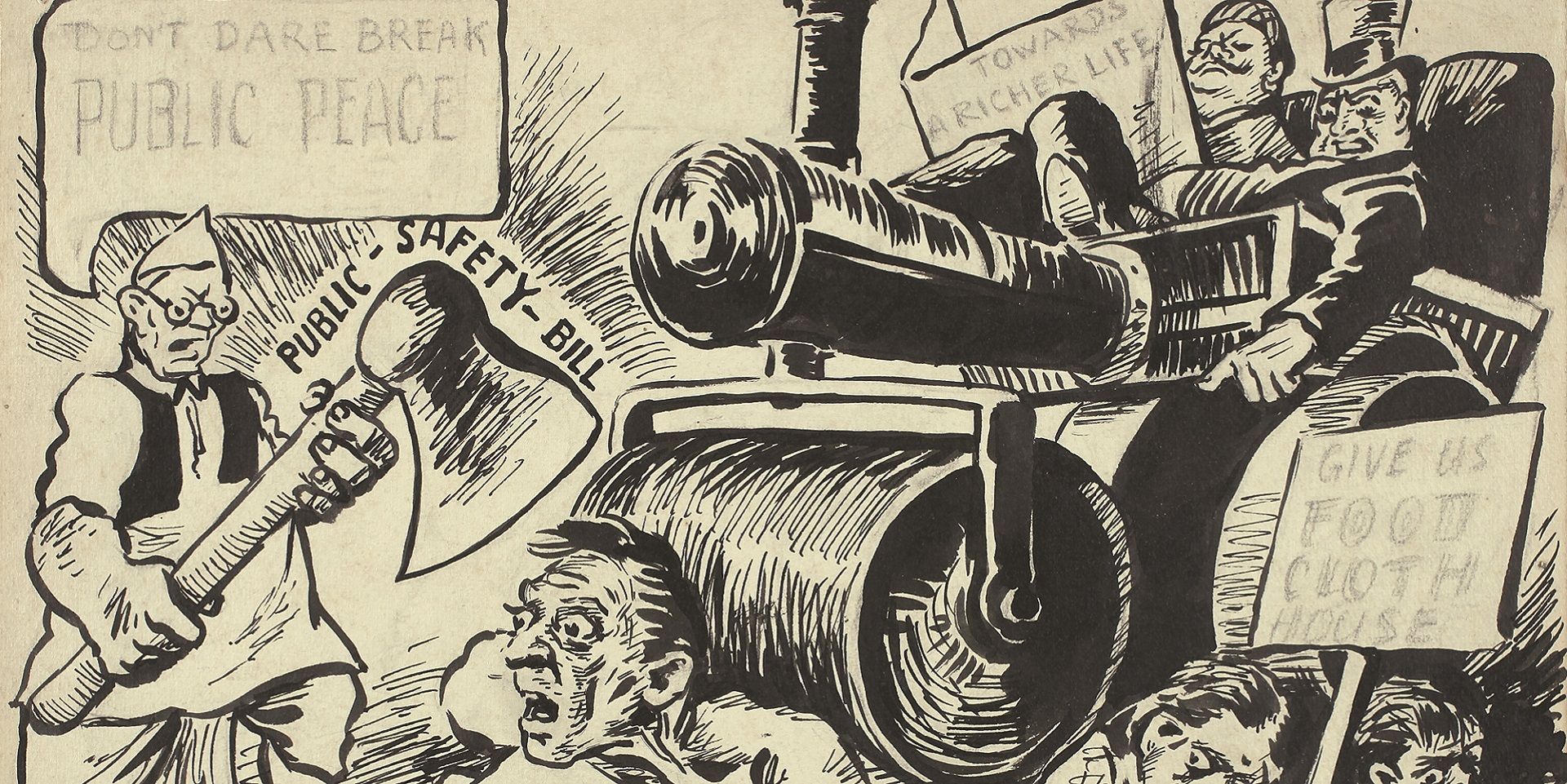

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

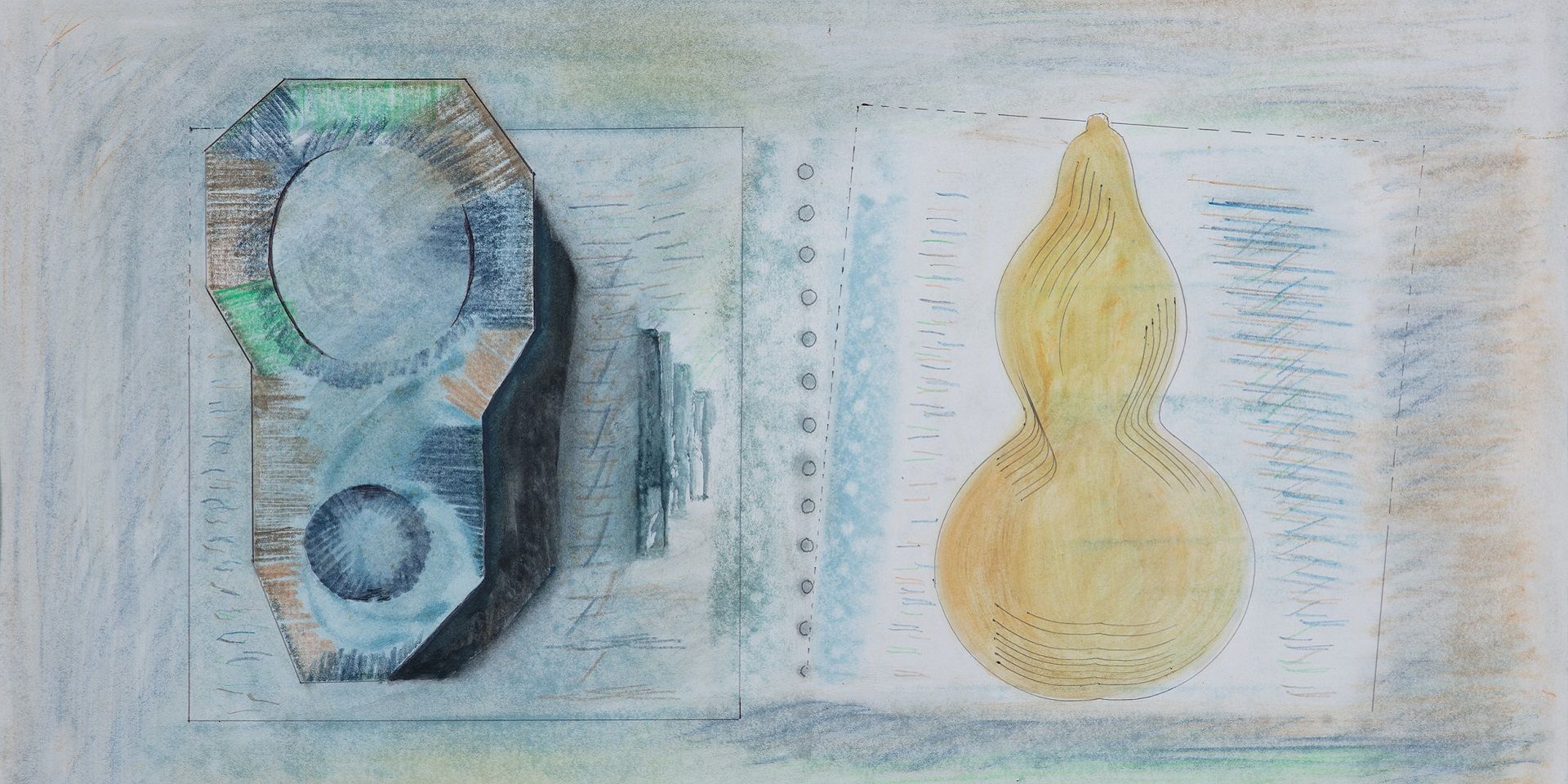

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024