Open Air Archives: Recovering History through Landscape

Open Air Archives: Recovering History through Landscape

Open Air Archives: Recovering History through Landscape

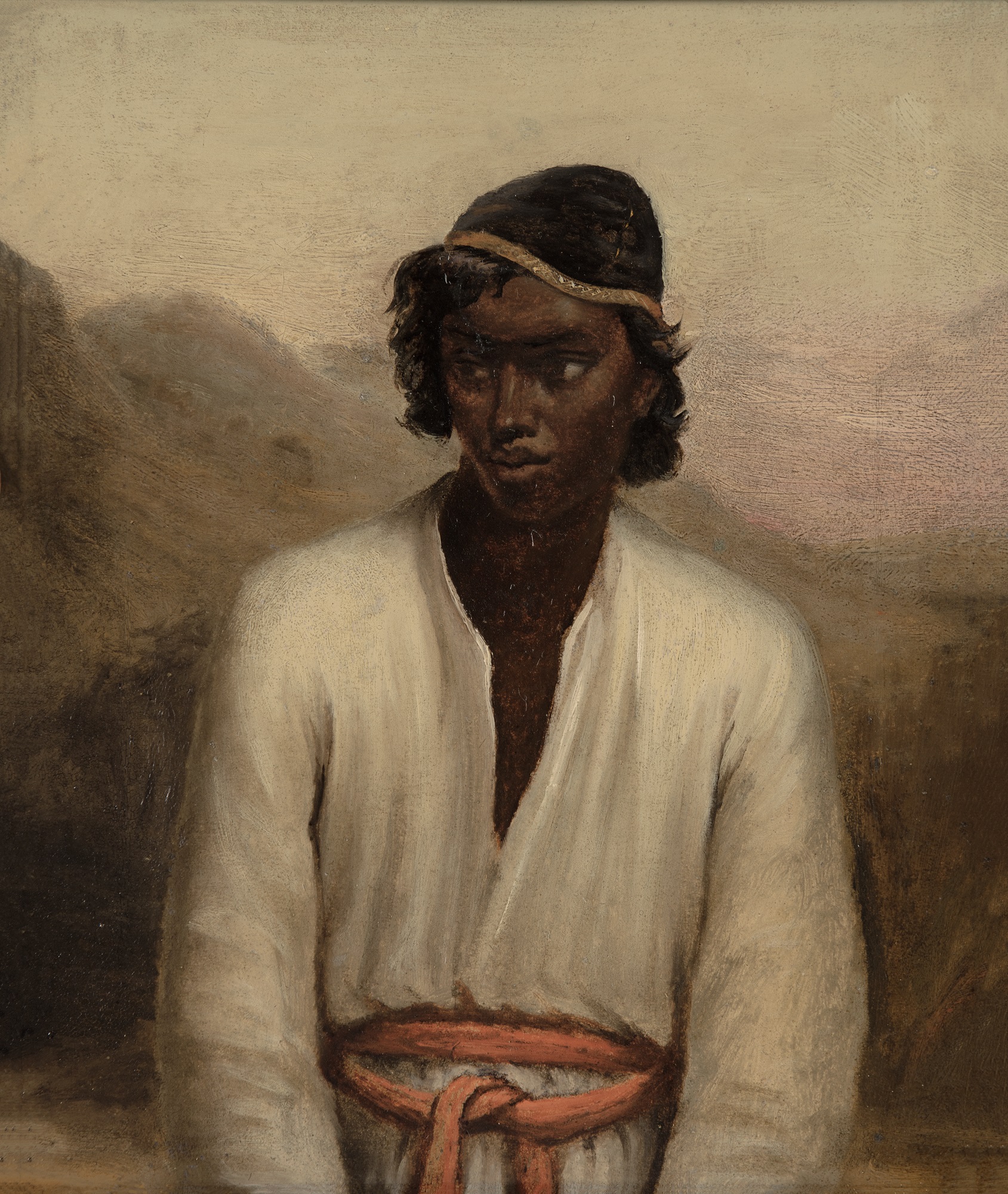

Pestonji Bomanji, Untitled, 1900, Oil on canvas, 12.0 x 23.7 in. Collection: DAG

'The roof comes down on Maruti’s head.

Nobody seems to mind.

Least of all Maruti himself

May be he likes a temple better this way.

…

The pariah puppies tumble over her.

May be they like a temple better this way.'

(Arun Kolatkar, Jejuri)

Open air painting, also known as en plein air (French for ‘in the open air’), refers to the practice of painting outdoors, directly from the landscape, rather than in a studio. While artists have sketched and sometimes painted outdoors at least since the early modern period, these works were typically preparatory studies for larger studio paintings. The true emergence of plein air as a central method and philosophy in art emerged in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

|

Thomas Gainsborough, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, Oil on canvas. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

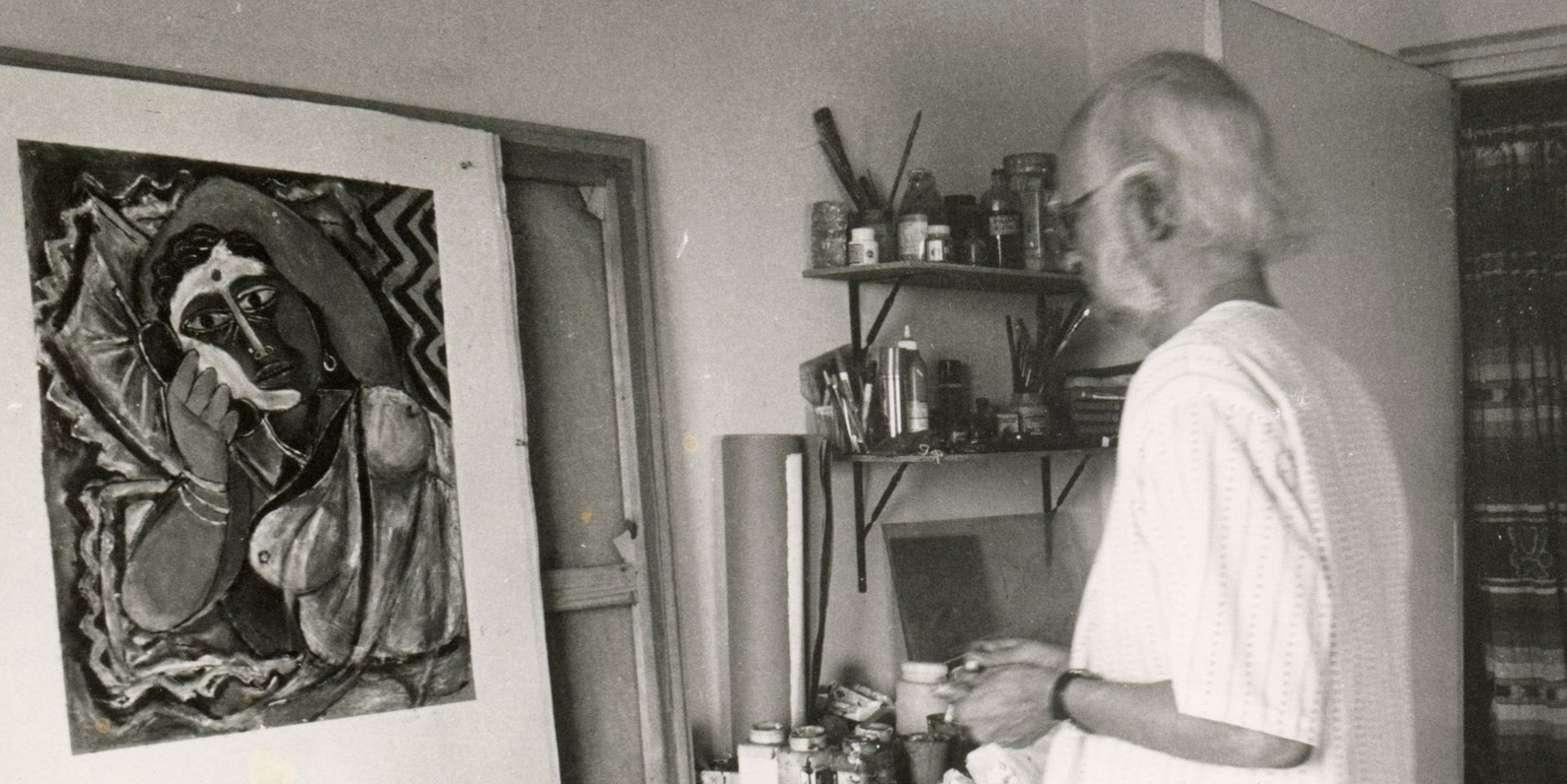

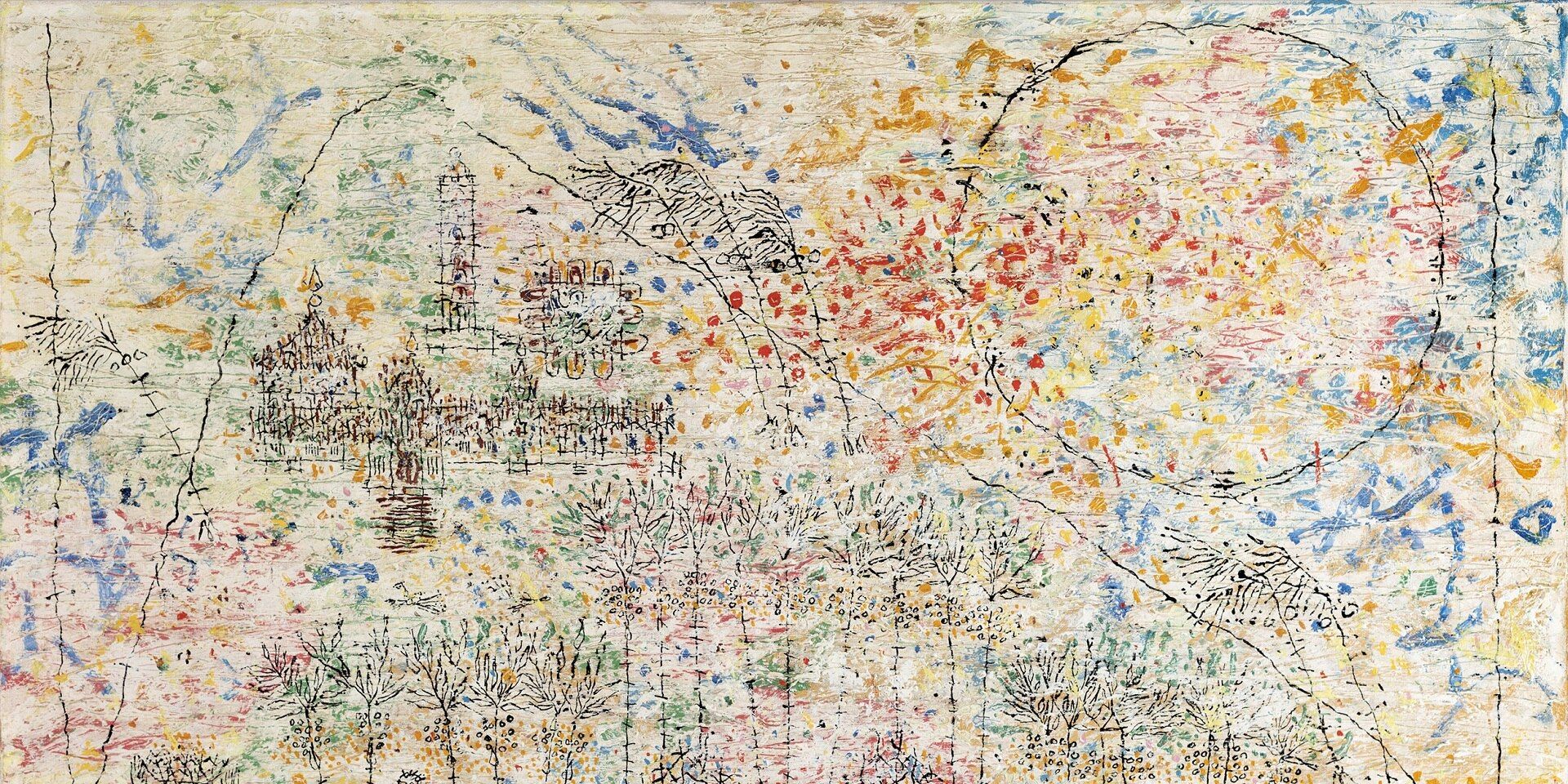

In England, artists such as John Constable and J. M. W. Turner began producing finished landscape works directly from nature, moving away from the idealised, studio-based landscapes of their predecessors, marking a subtle embodied shift between landscape painting in general and the emergent plein air style. There is a marked contrast between the kind of landscapes produced by Pestonji Bomanji and the generation of students that graduated from Bombay’s Sir J. J. School of Art following his time at the same academy. While Bomanji’s unpeopled landscapes (sometimes depicting grazing or, lounging cattle) recall the methods and ideas of an English Romantic or pastoral painter like Thomas Gainsborough, the later generations experimented more with the lay of the landscape and techniques of rendering them for an initiated viewer who was a version of the artist’s modern, reconstructed proto-nationalist self. How did this change come about?

Pestonji Bomanji, Untitled, 1900, Oil on canvas, 12.0 x 23.7 in. Collection: DAG

The plein air technique reached its artistic peak with the Impressionists in France. In the 1860s, Claude Monet and others began painting finished works outdoors, focusing on capturing the fleeting qualities of light and colour in real time. Their approach—painting ‘alla prima’ (wet-on-wet, often in a single sitting)—contrasted sharply with the meticulous, layered methods of academic studio painting. Italy too played a pivotal role in the early history of plein air painting, attracting artists from across Europe who sought to capture the unique light and landscapes of the region. Italian artists, artworks and plaster cast models wielded a strong influence on the development of art academies in colonial India; making a turn toward this practice almost inevitable by the end of the nineteenth century. Similarly, as a recent exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art suggests, the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich ‘reimagined European landscape painting by portraying nature as a setting for profound spiritual and emotional encounters’. As the show makes clear, the ‘German Romantic movement… championed a radical new understanding of the bond between nature and the inner self’. Painted against the backdrop of diverse European polities achieving national consciousness over the course of the nineteenth century, whether Germany, Italy or even England, in whose case a national imaginary was formed against the background of imperial expansion—the significance of these works is not just limited to their technical breakthroughs but espouse a new shift in the artist’s identity as a communicator of national memory.

Caspar David Friedrich, Memories of the Giant Mountains, c. 1835, Oil on canvas. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Johann Gottfried Herder, a foundational figure in both German Romanticism and nationalism, introduced the concept of Volksgeist (the ‘spirit of the people’), arguing that each nation possesses a unique character expressed through its language, traditions, and culture; and, in his scholarship, framed India as the cradle of human spirituality. He described India as the ‘soil of God’, representing humanity’s ‘childhood’ marked by innocence and closeness to nature. This Romantic vision influenced Orientalist scholars like Max Müller, who saw India’s Vedic texts as a key to understanding universal religious truths. He wrote: ‘I well remember when I was at school; one of my copybooks had a large picture of Benaras... What did I know of India at that time? Nothing but that the people were black... On my picture, however, they are represented looking tall, and, as I thought, beautiful’. This idealisation positioned India as a mystical counterpart to Western rationalism, but also reduced its complexity to a static, primordial archetype. It is crucial to note, therefore, that these larger philosophical transformations in thought that tried to construct a modern, nationalist self in Europe, had Indian sources as a basis to work from, in spite of their scholarly distortions through language, conflicting motivations and the unequal distribution of power over this body of knowledge about an entity called ‘ancient India’. For a Bombay School artist like M. S. Satwalekar, who produced picturesque landscapes before turning to study the Vedas and joining the nationalist movement, these intellectual, or consciousness raising contexts were of primary importance, where, to echo Friedrich’s words, when they learned to truly look at the landscape, they also learned to look within themselves. It is worth asking, however, if there were any Indian developments and concerns that may have led to this practice becoming popular across the country too.

|

Abalal Rahiman, Fort Panhala, Oil on canvas, 10.5 x 7.7 in. Collection: DAG |

While pilgrimage tended to be the only social occasion when Indians went on tours to temples or sacred caves across frequently difficult terrain, the arrival of new technologies of travel, such as the train, and new modes of thinking about the country as a unified, sacred landscape and source for the nation’s natural beauty, especially outside its increasingly cluttered urban centres, led to more Indian artists and travellers stepping outside their familiar environment and confronting the sublime remnants of their past.

Moreover, as Partha Mitter writes in his discussion of Bombay’s Open Air artists… ‘the most noticeable aspect was the sketch-like character of the paintings.’ The ‘sketch-like character’ of the paintings speak to the larger, almost deliberate sense of unfinishedness—which allowed these landscapes to provide access routes for viewers to complete the whole aesthetic sensation of experiencing the location itself.

|

N. R. Sardesai, Untitled, Watercolour on paper, 13.5 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

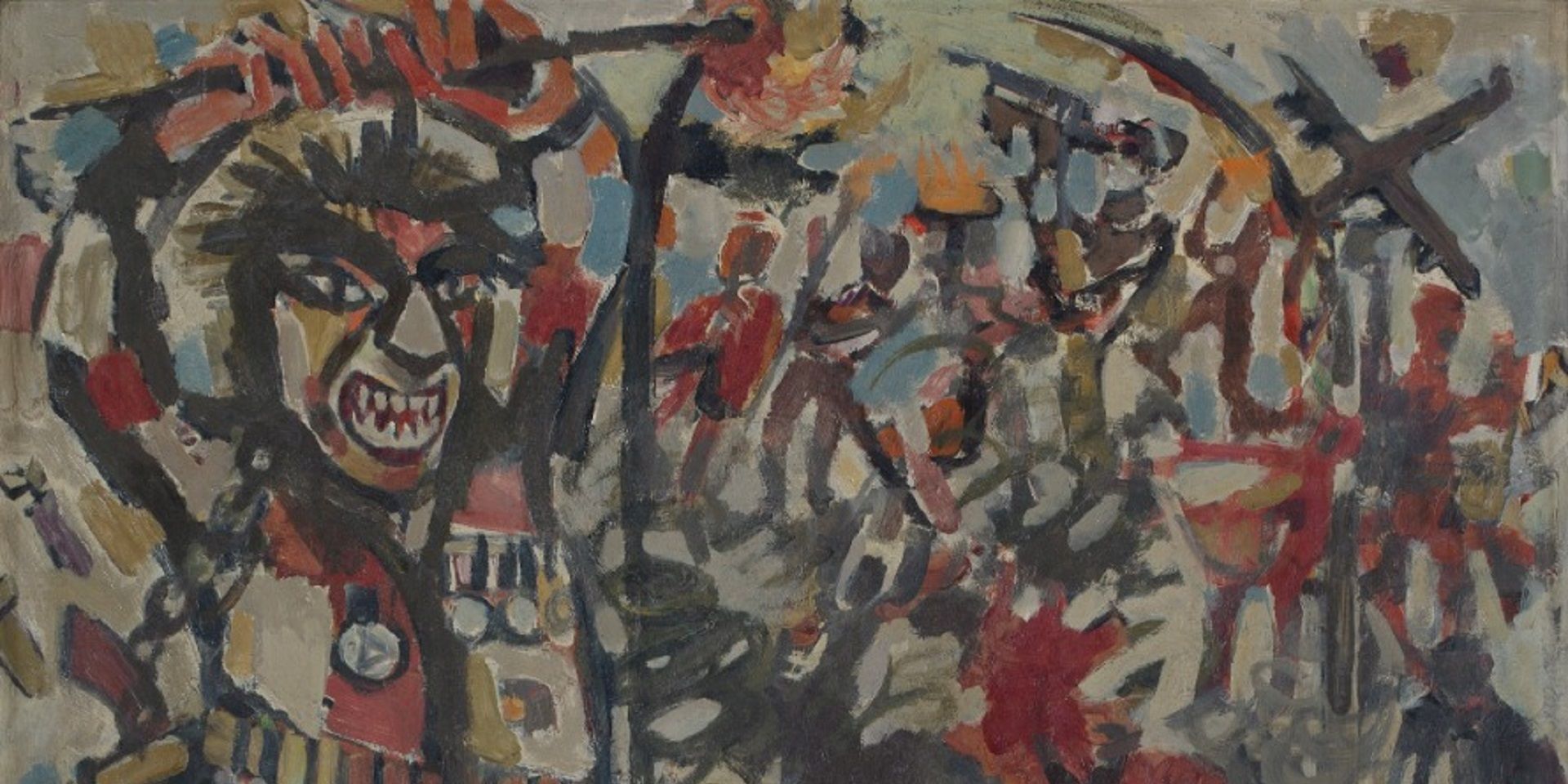

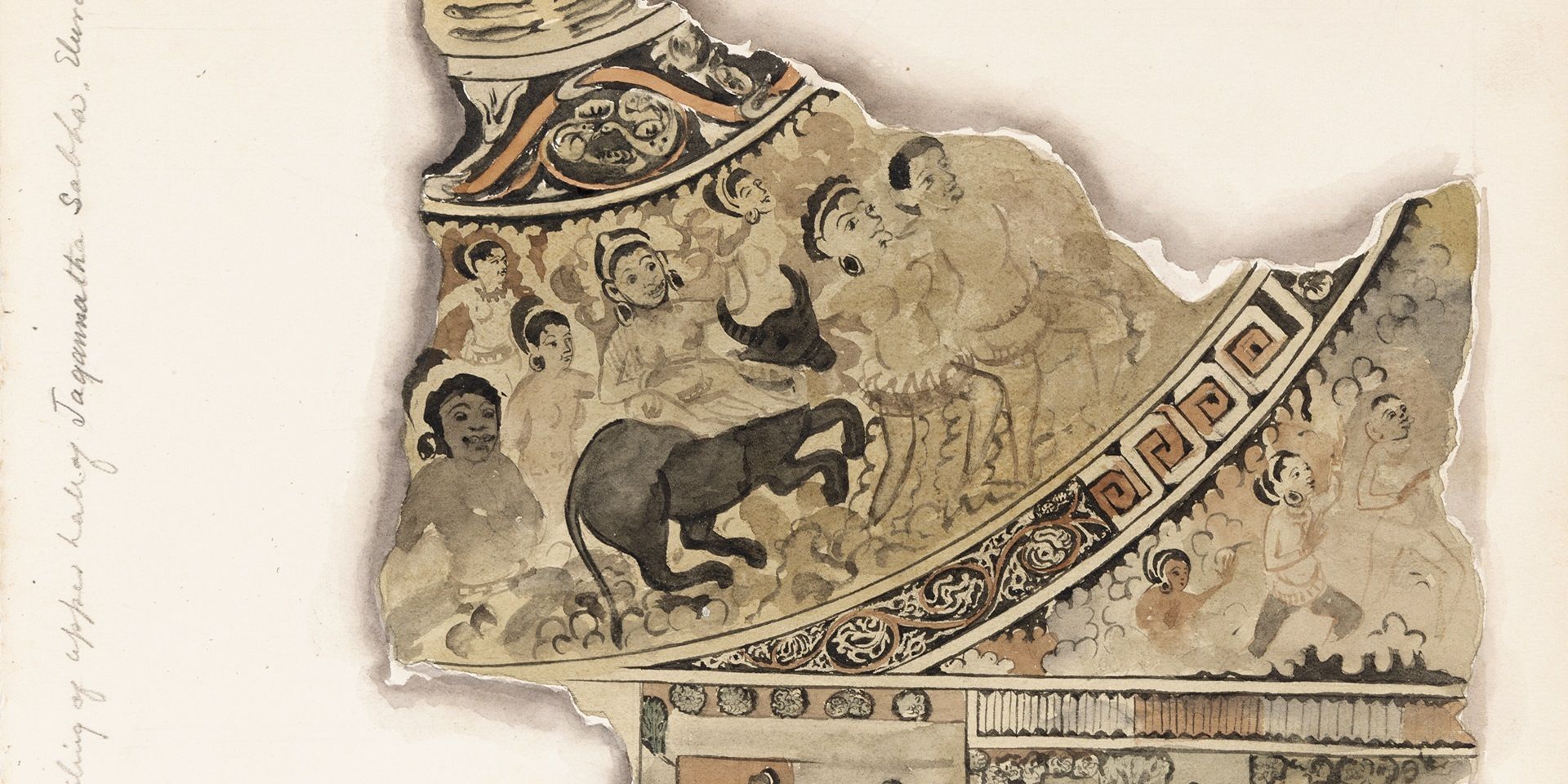

Eventually, drawing up an intimately experienced, sacred geography of the greater Bombay region, became an act of reappropriation from colonial modes of visual representation which passed as documentation. Precedents for this move went back at least to the tenure of John Griffiths, if not earlier. A teacher of decorative painting at Sir J. J. School of Art, Griffiths encouraged his students to paint in styles that were in harmony with the cultural environment around them. His own works highlighted the spaces and inhabitants of the countryside, including the portrait of a ‘Moplah Boy’, painted in the late nineteenth century, or a rural sage, suggesting that these sites offered potential counter-narratives to the colonial modern. In fact, as the title of the work seems to imply, community and landscape get intertwined in the case of the ‘Moplah Boy’. A few decades later, in 1921, the Mappilas (or, Moplahs) rose in revolt against the colonial administration and local landlords, and took control of police stations, colonial government offices, courts and government treasuries.

|

John Griffiths, Portrait of a Moplah Boy in a Landscape, Oil on board, 9.5 x 11.5 in. Collection: DAG |

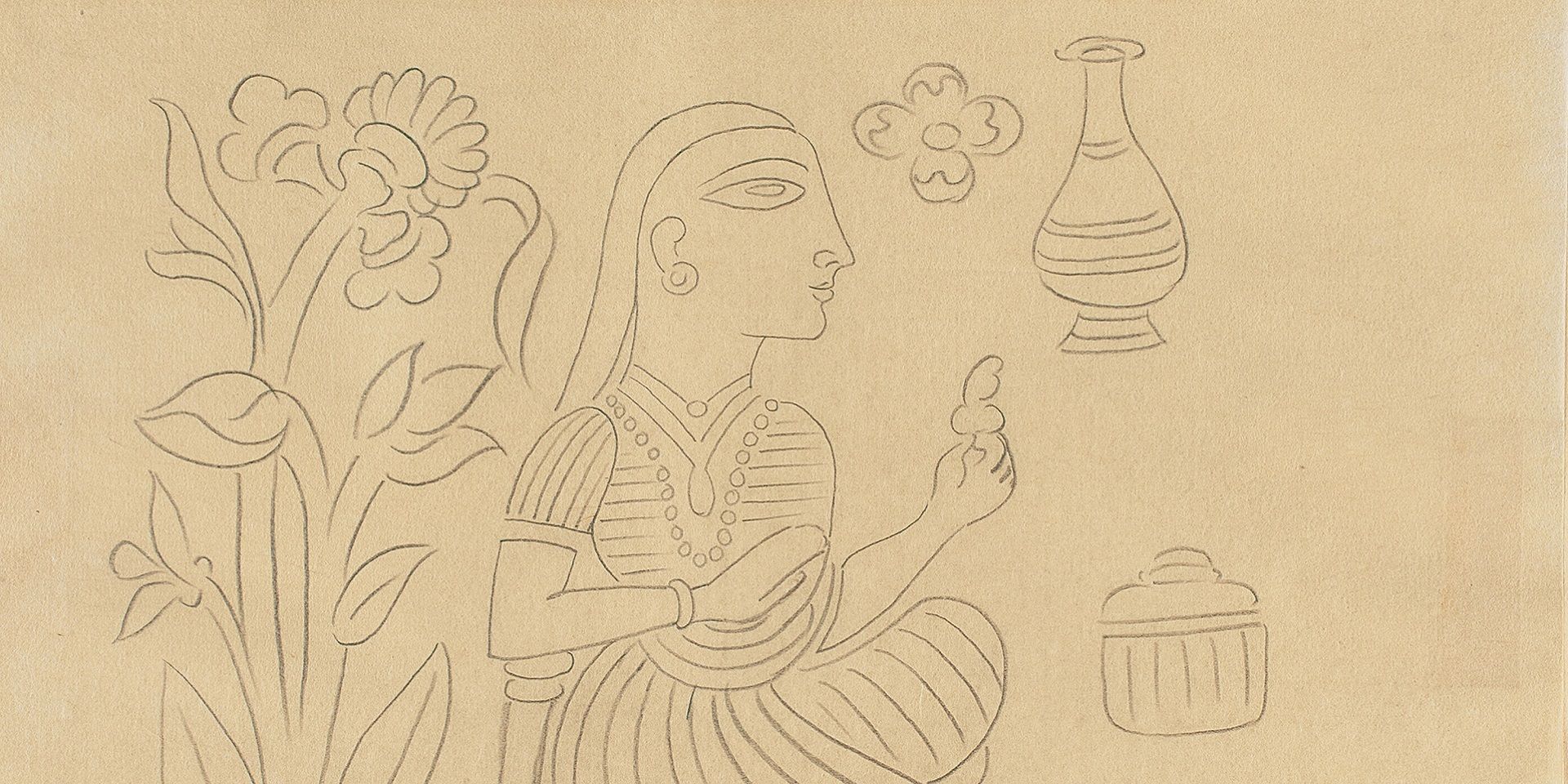

Much like the colonial representational regimes that reduced flora and fauna into specimens for study, the sacred structures of the subcontinent were similarly presented as flattened objects often in unmarked space, providing a source of information about its structural makeup, or simply as ruins that needed to be documented. For the open air artists of Bombay, this provided an opportunity to rescue the landscape from the rigid calculations of colonial typology, as they sought inspiration from poetry and the nationalist movement that sought to construct pride in the precolonial pasts of India.

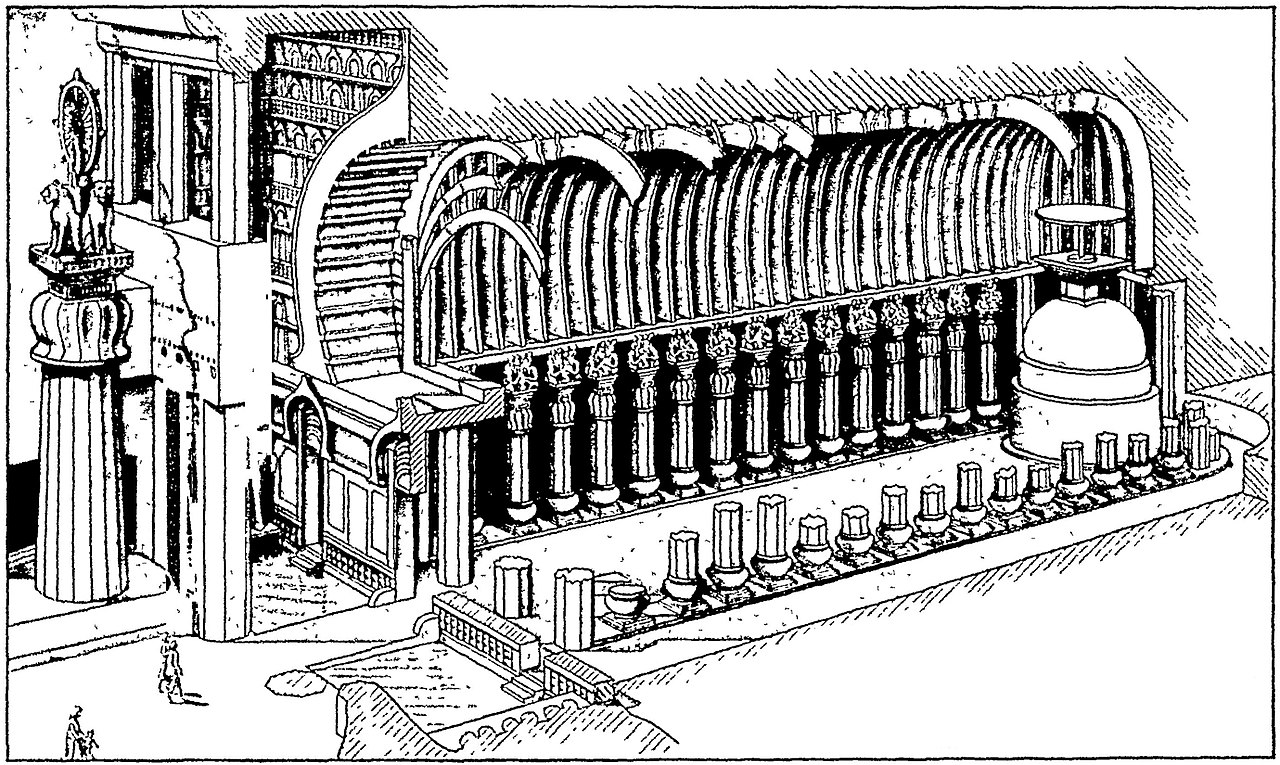

Percy Brown, Karla Chaitya section in perspective. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Karla Caves, located near Lonavala in Maharashtra, are among the oldest and most significant Buddhist rock-cut cave complexes in India, with their origins tracing back to the second century B. C. E. during the Mauryan Empire. These caves were primarily established as a monastery and center for Buddhist learning, meditation, and religious activity, serving as a vibrant hub for monks and traveling traders along ancient trade routes; and they received patronage from powerful rulers whose donations are recorded in inscriptions within the caves. The presence of the Ekvira Devi temple at the entrance, revered by the Koli community, is highlighted as an example of the site's continued religious significance and the blending of Buddhist and Hindu traditions over time. The caves are renowned for their grand chaitya (prayer hall), which is one of the largest and best-preserved of its kind in India, while the complex also includes viharas (monastic dwellings) and intricately carved facades, showcasing the development of rock-cut architecture in India.

|

N. R. Sardesai, Karla Caves, c. 1930s, Watercolour on paper, 13.7 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

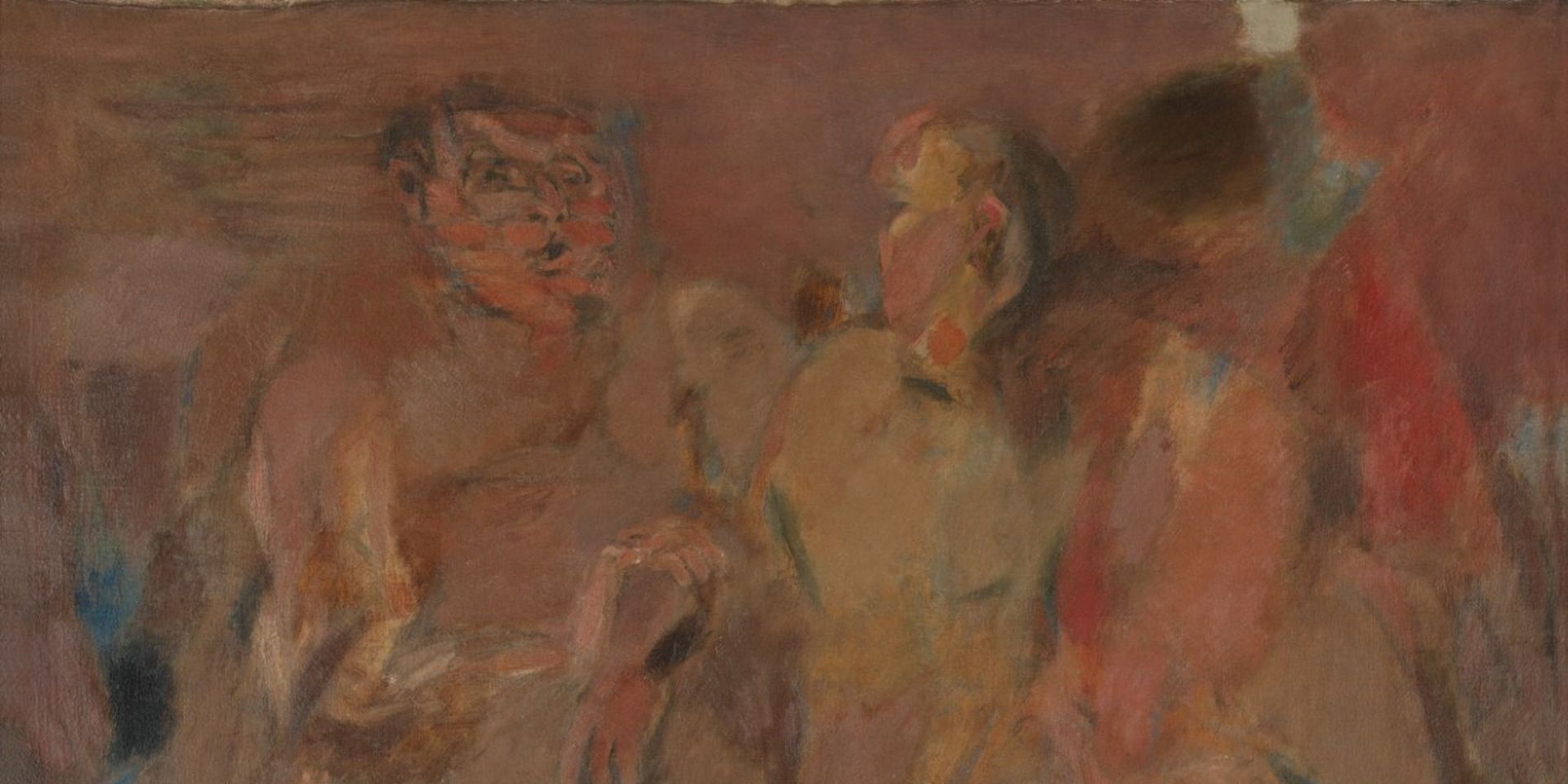

At the time, it was not just artists setting out on this complex quest for their new identity; so were potential historians. As historians of western India, such as Prachi Deshpande, have noted, the colonial archives were often inaccessible to Indian researchers, forcing scholars like V. K. Rajwade to travel the length and breadth of the Bombay Presidency and beyond, exploring personal archives, princely states’ collections and other non-official sources to write Maratha nationalist histories of the region—often to ‘correct’ the denigrating accounts contained in British colonial historiography regarding the significance of that history. A romantic imagination enters the terms of this enterprise as Deshpande writes: ‘Stories of Rajwade’s indefatigable search for these documents have now become legendary, and tales abound of how he snatched papers from a reluctant chieftain here and lost his famous Durvasa rishi-like temper at a recalcitrant and suspicious chief there.’ And out of these efforts, alternative spaces for history were created, such as the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal in Pune in 1910 by Rajwade, which made history accessible to the ordinary Indian scholar. Similarly, the western Indian artists, whose identities were being shaped into a modern Indian-Maharashtrian one at the same time, and who committed themselves to similar intellectual projects being promoted by local patrons and scholars, tended to approach these mythical landscapes through the lens of accessibility and reappropriation. As Partha Mitter also suggests, there was a turn away from earlier modes of approaching a mythic past and towards depicting the everyday present, which was also shaped by historical forces around them: ‘This generation forsook the earlier historicist treatment of ancient mythology that had been the hallmark of a Herman Muller or a M. V. Dhurandhar, turning to the ‘here and now’ and the quotidian… To these artists the quality of the light and the outdoors became more important than the niceties of period details.’

N. R. Sardesai, Jogeshwari Caves, 1940, Watercolour on paper, 9.2 x 13.2 in. Collection: DAG

In spite of the problems that such nationalist paradigms of historical imaging frequently entailed, it remained an important step towards democratising the landscape of history itself. And as Deshpande has argued, historians associated with the ‘Poona School’ often held diverse views, including more secular ones than is usually supposed. Let us take a look at some of the other places that were typically painted by Bombay School painters.

The Jogeshwari Caves, seen here as painted by Sardesai and D. C. Joglekar, is located in the suburb of Jogeshwari in Mumbai, which is now a densely inhabited neighbourhood, and constitutes some of the earliest and largest rock-cut Hindu cave temples in India, dating to the sixth century C. E. These caves hold immense historical and mythological significance, especially in the context of early Hindu religious architecture and the cult of the goddess. The caves are primarily associated with Jogeshwari Devi, a form of Shakti or Yogini, considered a powerful manifestation of the Divine Feminine. Its situation in a contemporary urban center emphasises its ongoing relationship with a devoted public.

|

D. C. Joglekar, Untitled, Watercolour on paper, 16.0 x 23.7 in. Collection: DAG |

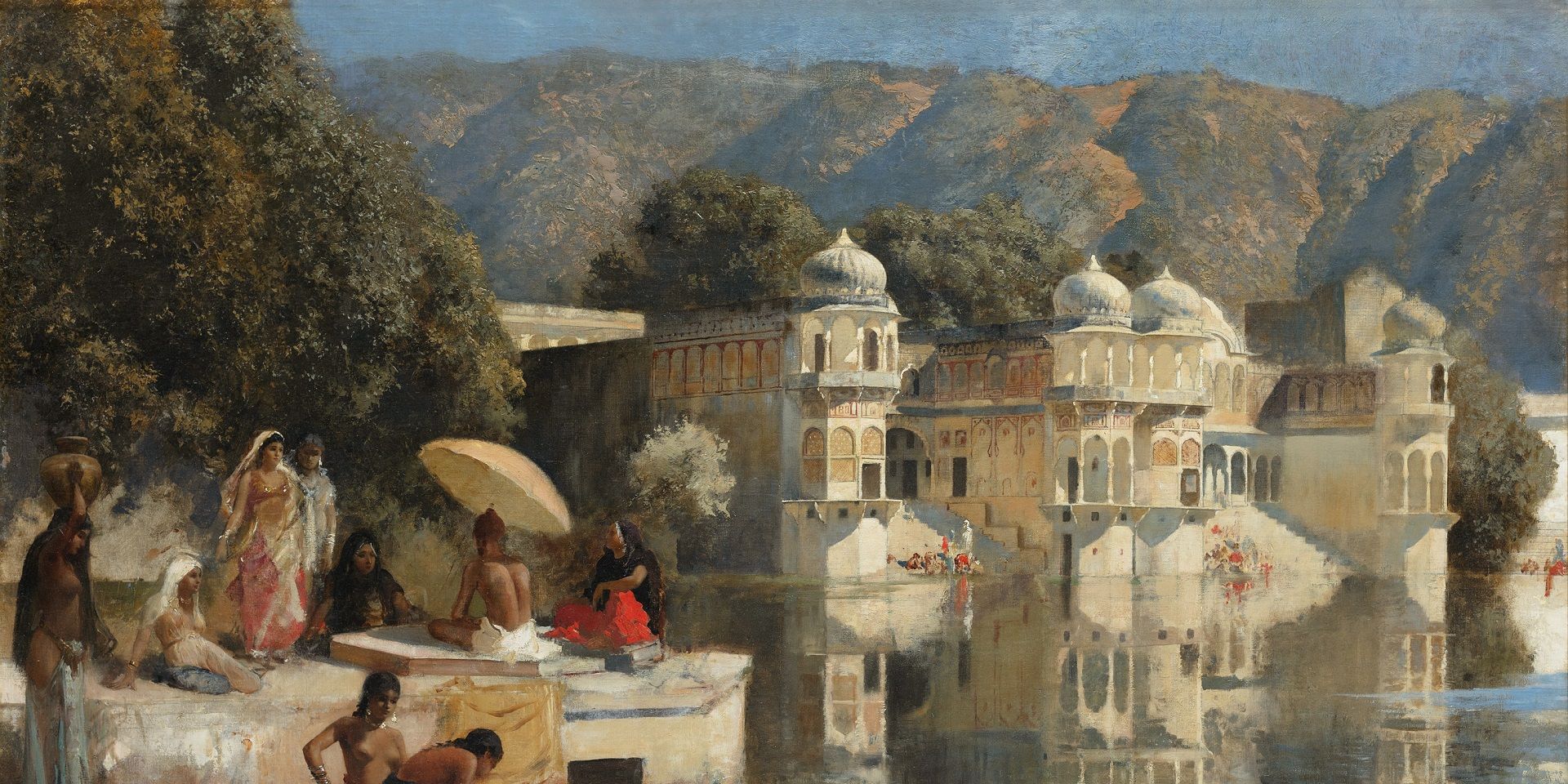

Vasai Fort, also known as Bassein Fort, stands as a major symbol of Maharashtra’s layered history, reflecting centuries of power struggles, maritime trade, and cultural exchange. Probably founded as early as the twelfth century, by the fifteenth century it became an important maritime hub under the Gujarat Sultanate, which added Islamic architectural features to the fort. The Portuguese seized control in 1534 through the Treaty of Vasai and transformed the fort into Fortaleza de São Sebastião de Baçaim, their principal naval base north of Goa, and the fort became a self-contained city with amenities such as colleges, markets, a mint, and even an orphanage. The fort complex contains remnants of several churches built by the Portuguese, as well as temples and Islamic carvings from earlier periods. After the Maratha conquest, church bells were taken as war trophies and installed in temples across Maharashtra, symbolising the transfer of power and the blending of religious traditions.

|

N. R. Sardesai, Bassein Fort, 1922, Watercolour on paper, 10.0 x 6.7 in. Collection: DAG |

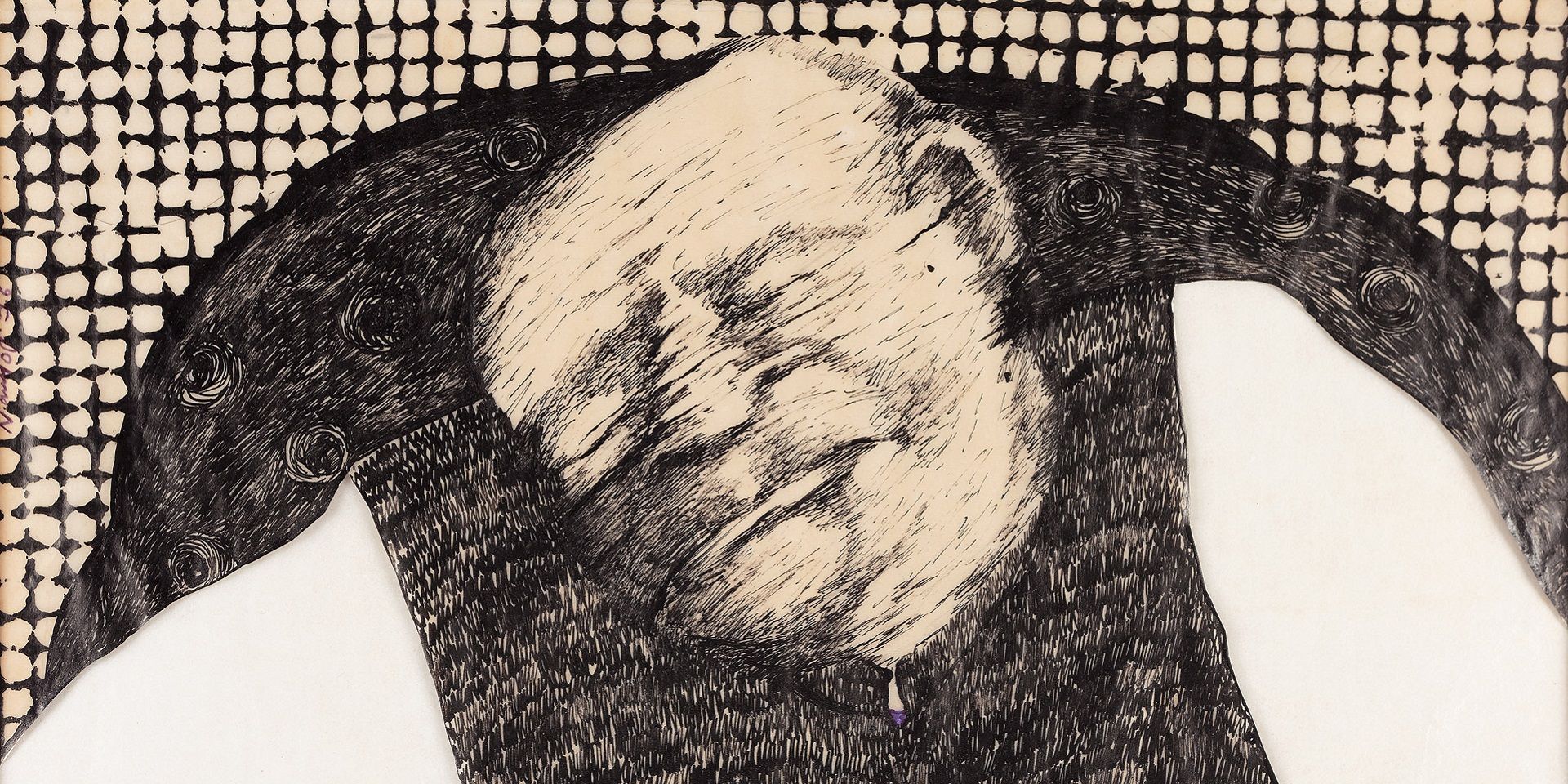

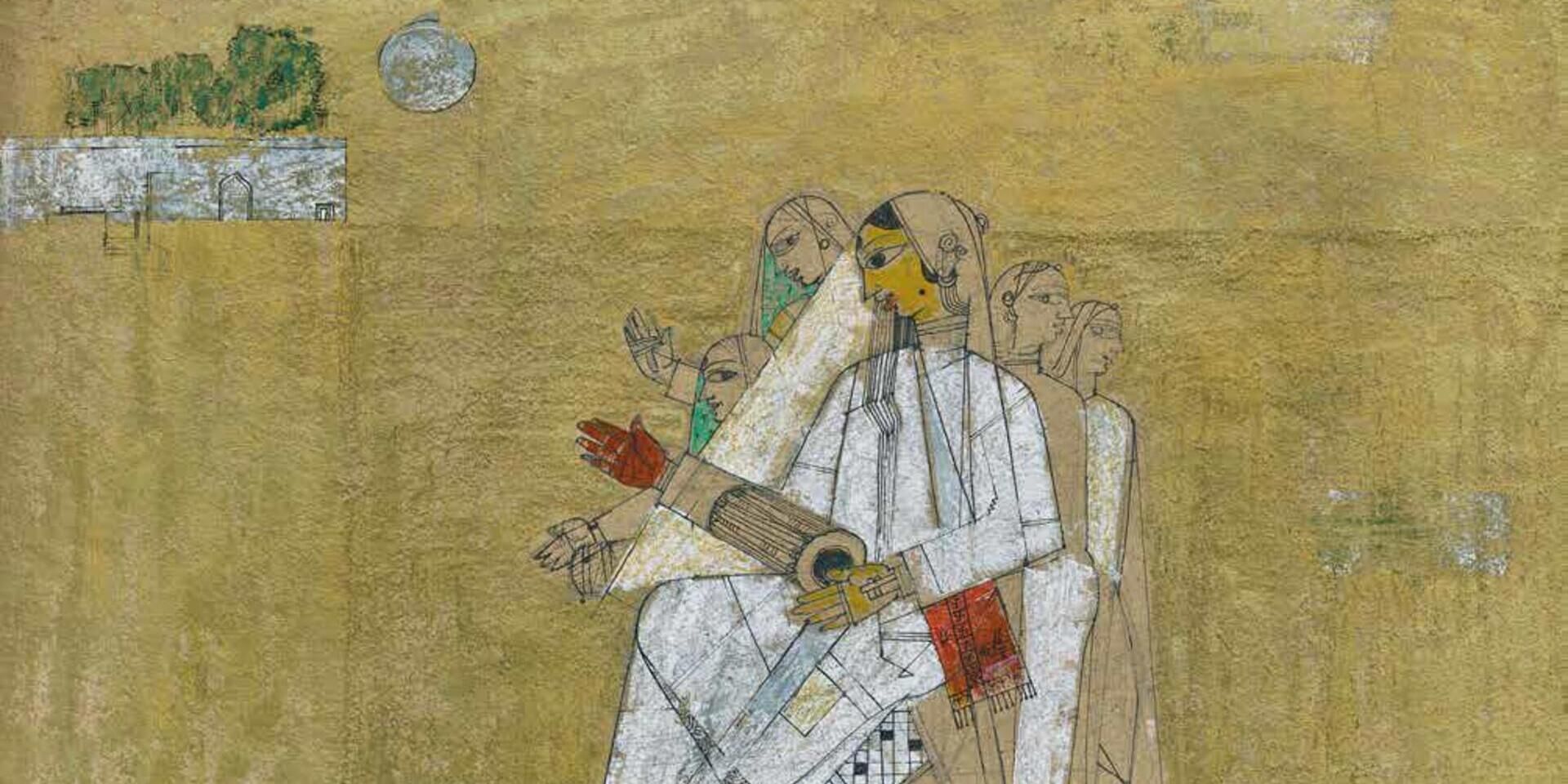

The fort’s strategic importance led to its capture by the Marathas in 1739. This victory marked the end of Portuguese dominance in northern India and showcased Maratha military prowess. They made their own additions to the fort, further blending Portuguese and Indian architectural styles. Eventually, the Marathas ceded control to the British in the early nineteenth century, and the fort’s military significance waned. These creative acts of appropriation rested on the artists’ ability to invest, or ‘graft’ them—to use Holly Shaffer’s term for the process of complex inter-mingling of artistic styles under Maratha patronage—with new significance and populate them with novel configurations of human relationality.

|

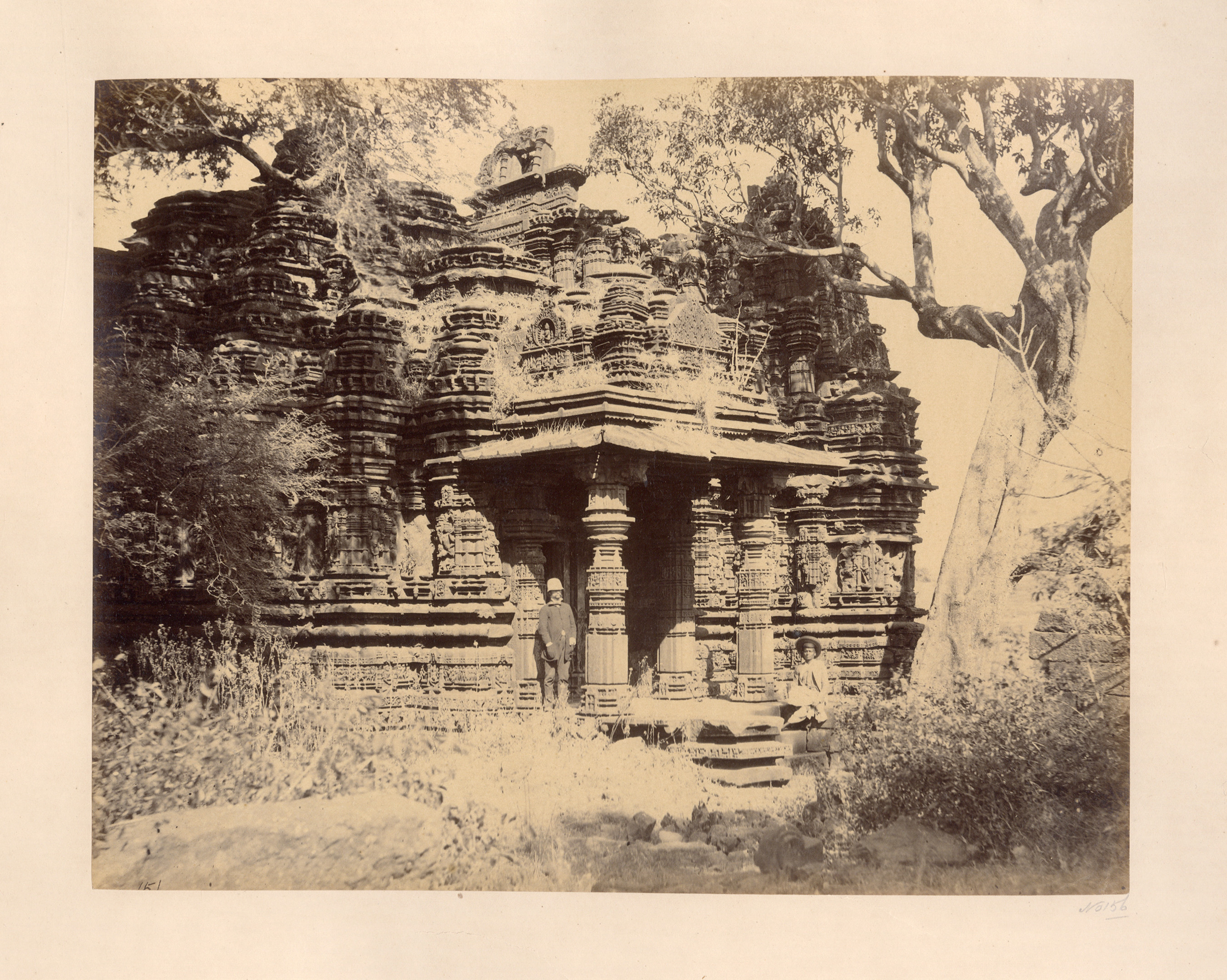

D. C. Joglekar, Ambarnath Temple, Watercolour on paper, 20.5 x 13.5 in. Collection: DAG |

On the other hand, D. C. Joglekar’s painting of a temple at Ambarnath, near Kalyan, has a further metahistorical turn to it, by hearkening back to the earliest outdoors project undertaken by students at the J. J. School of Art in 1868—when they were taken to the same place to document a temple, probably as part of a commission by the Archaeological Survey of India, which was established earlier that decade and served as an important patron for documentary photographers and artists. These landscapes, with their monuments, temples and mosques, stripped of their mythic trimmings and peopled with pilgrims and devotees often out on casual visits and picnics, constituted a potent archive for a decolonial history.

|

William Johnson and William Henderson, Ruined Temple of Ambernath, near Callian – Eastern Portico (Shiva Temple, Ambernath, Kalyan), Silver albumen print from wet collodian negative mounted on card, 1855–62, Print size: 7.5 x 9.4 in. Collection: DAG |

From the romantic position of approaching these landscapes as a large, open air historical archive, postcolonial artists and poets would move further and excavate even deeper relationships between their spiritual lives, the secular life of the nation and the enchanted imagination of new sacred values. Consider the dry irony of a poet like Arun Kolatkar, whose poem Jejuri (1976), set in a temple town in Maharashtra, grapples with these new realities. The temple is no longer a source for rejuvenating national pride and spiritual growth, which must be recovered from the thickets of colonial inscription and objectification, but a space for shelter and a potential site for everyday activity—becoming mainstreamed into the lives of its inhabitants as well as the journeying tourist from the decadent city. From restoring these structures to a people’s gaze, as the Bombay School artists did at the turn of the twentieth century, Kolatkar’s poem moves it to consider the gaze of God or the pariah puppies that live there: ‘perhaps He likes a temple better this way’.

related articles

Essays on Art

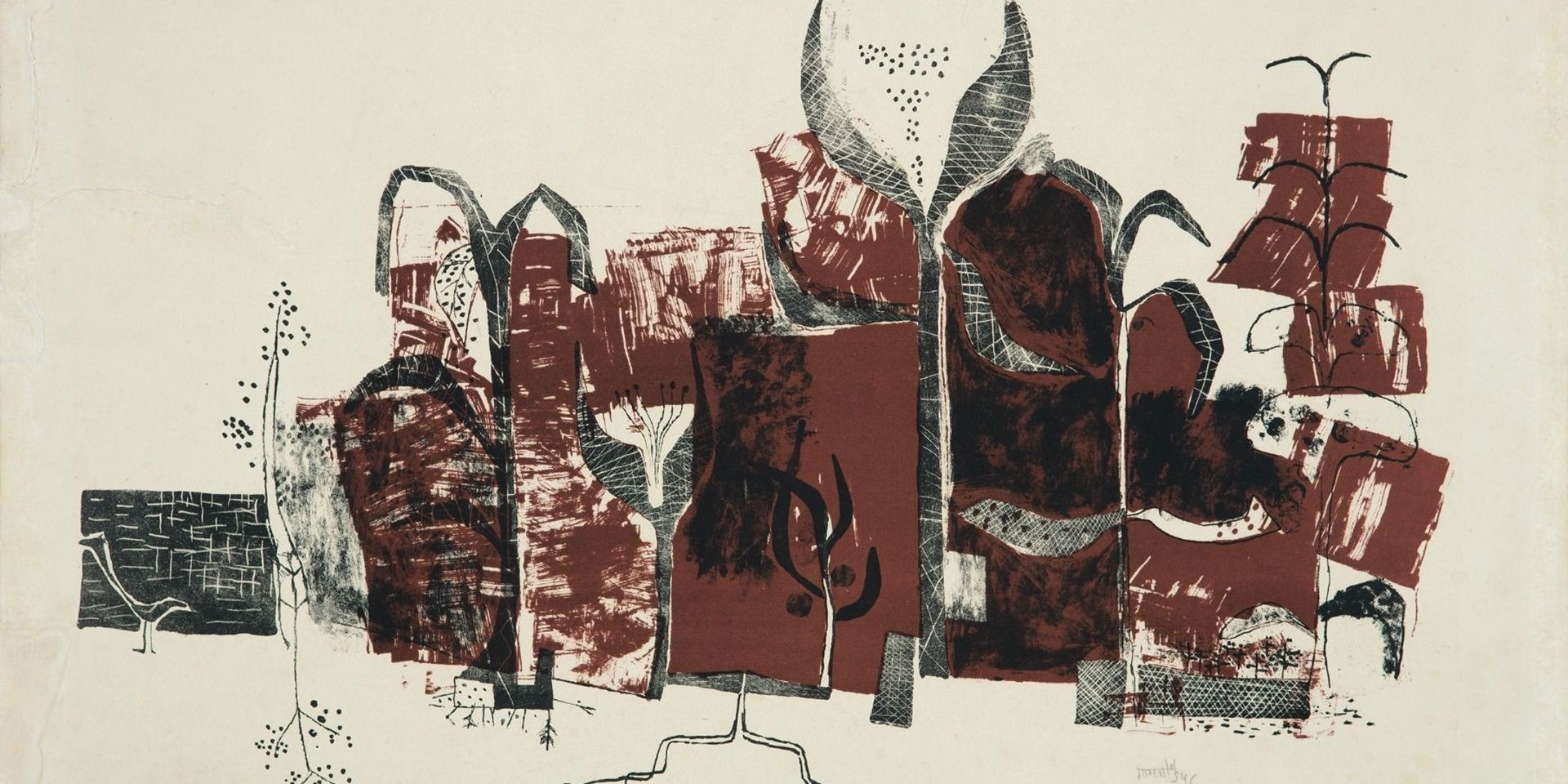

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

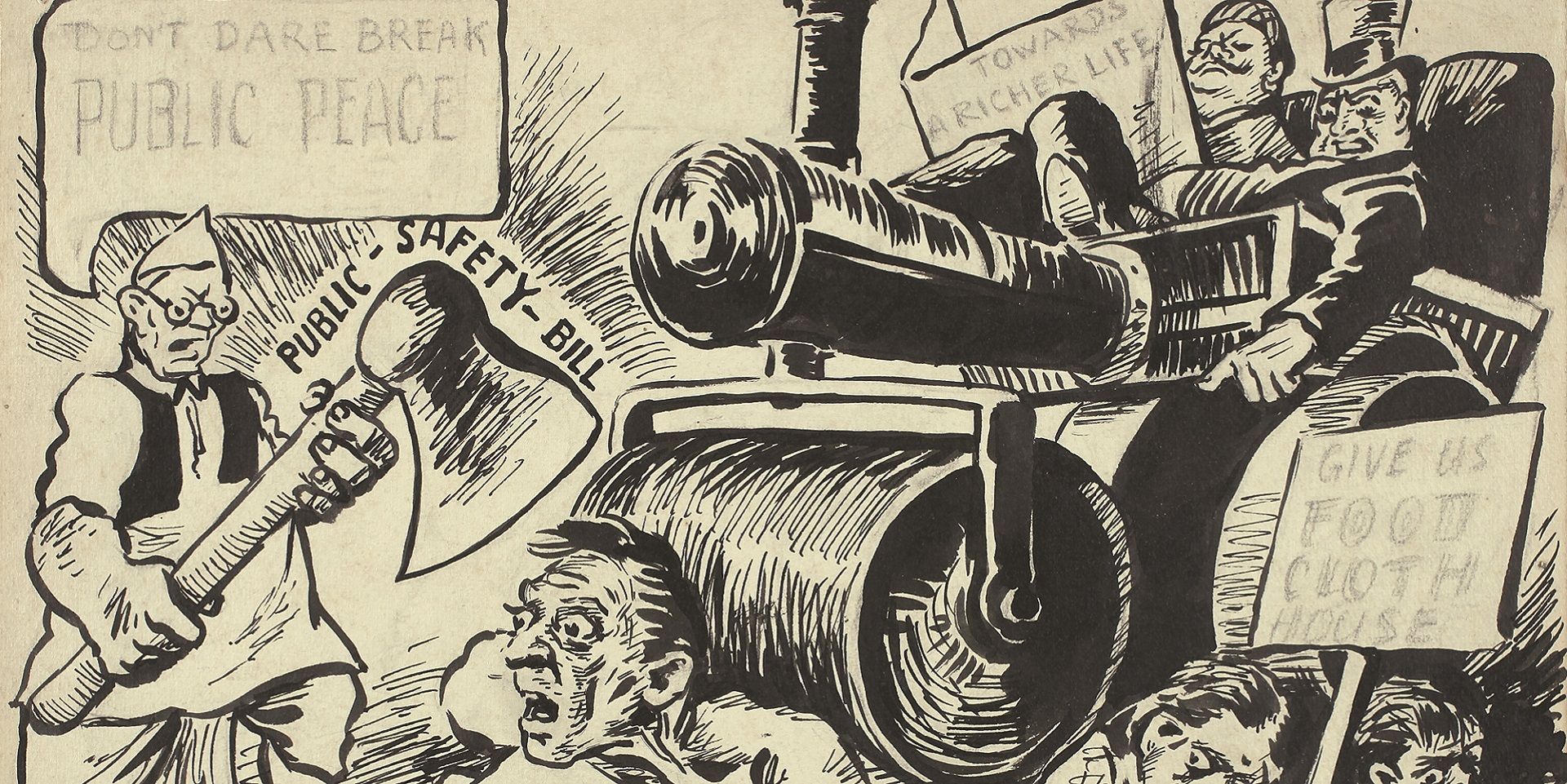

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

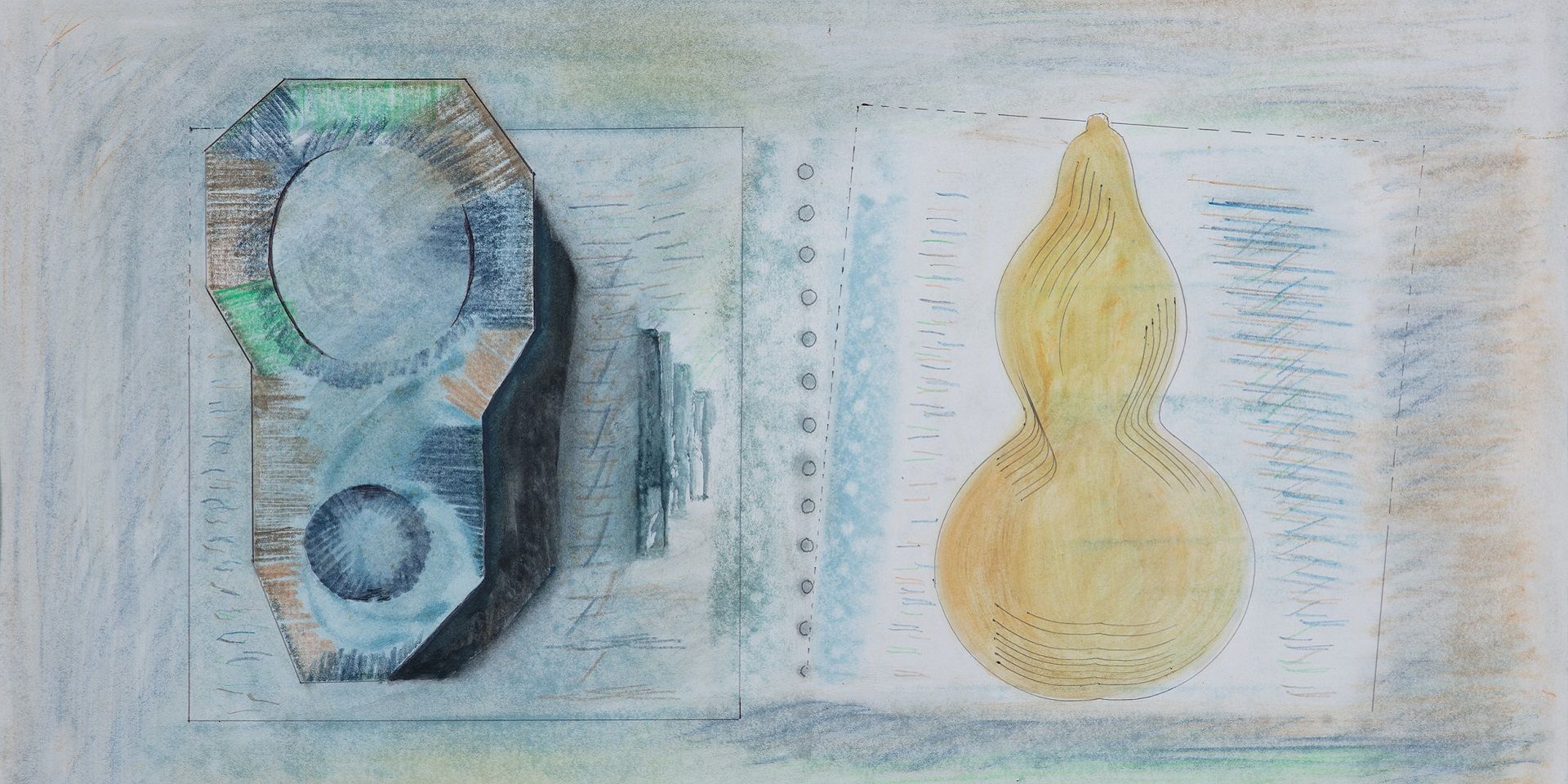

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

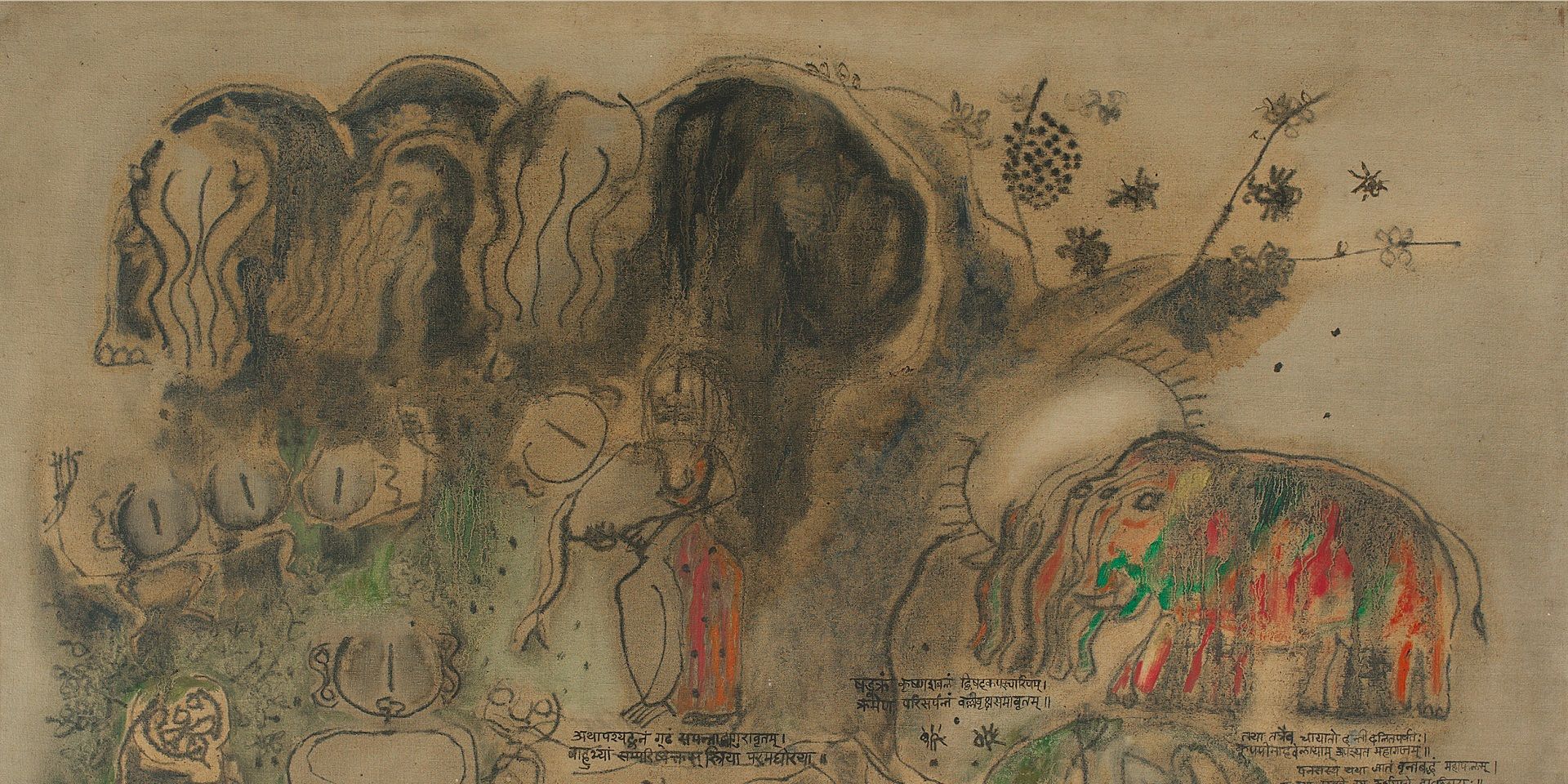

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

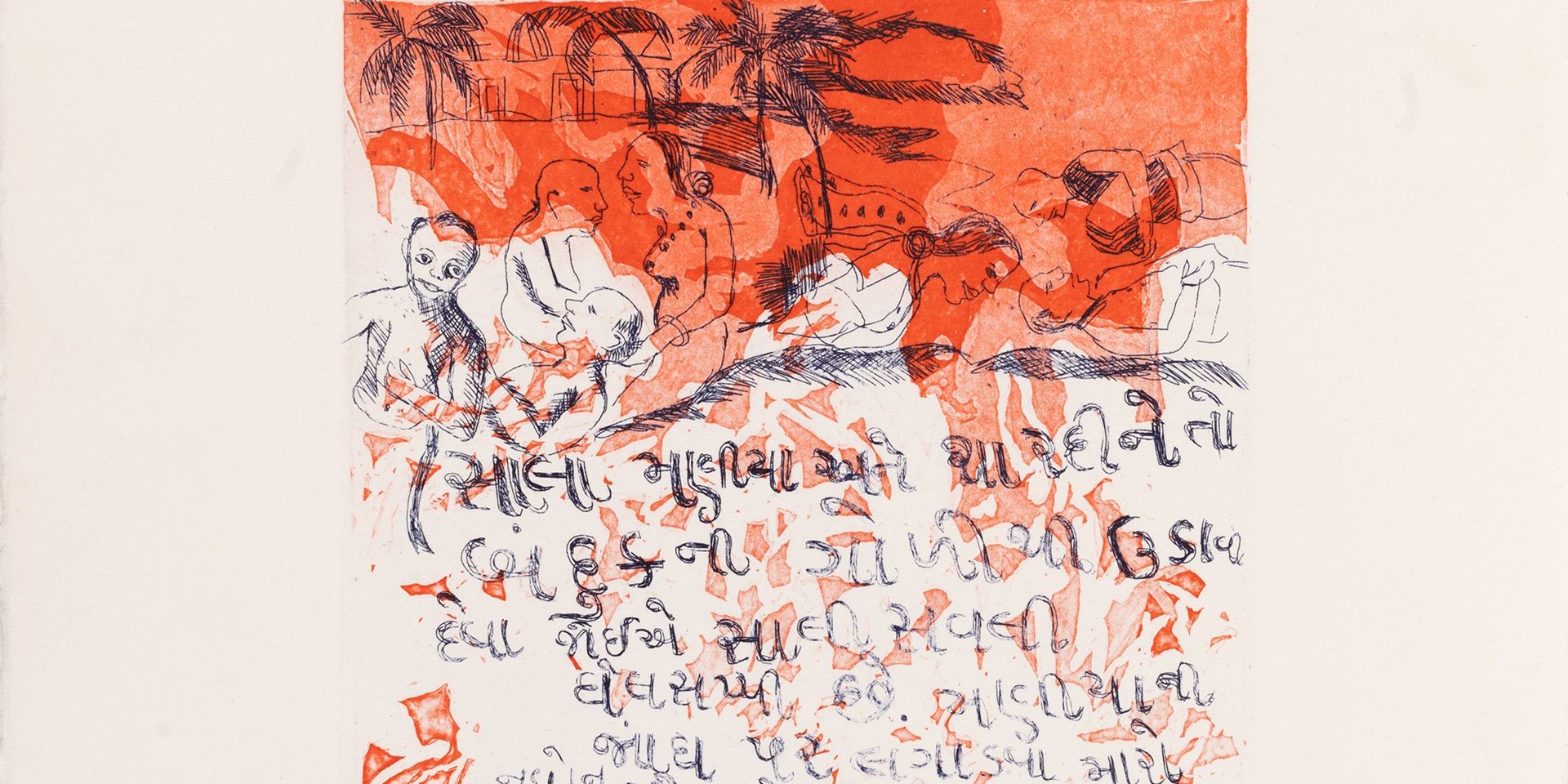

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024