Networks and Assemblages: Reading Karin Zitzewitz

Networks and Assemblages: Reading Karin Zitzewitz

Networks and Assemblages: Reading Karin Zitzewitz

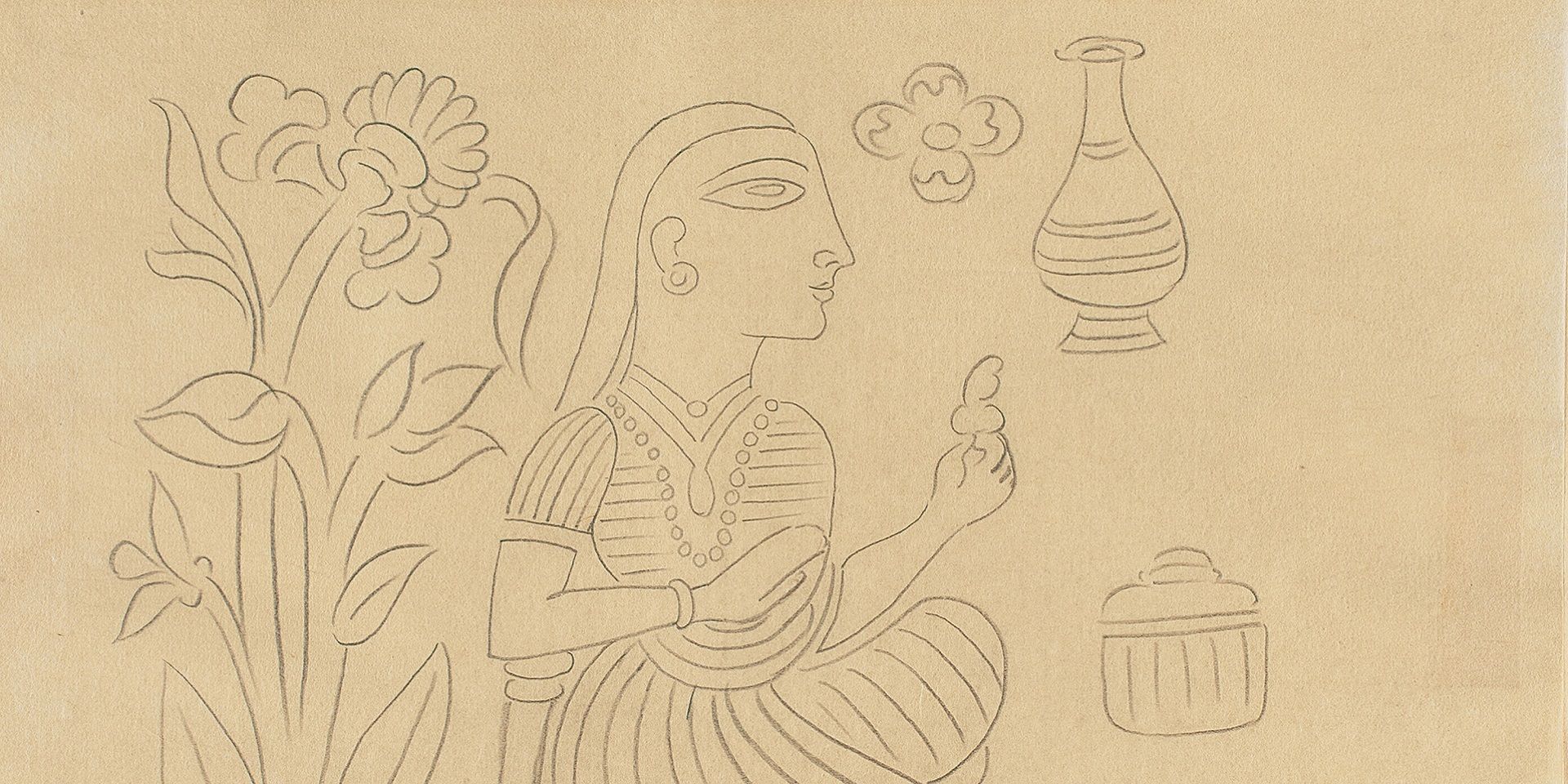

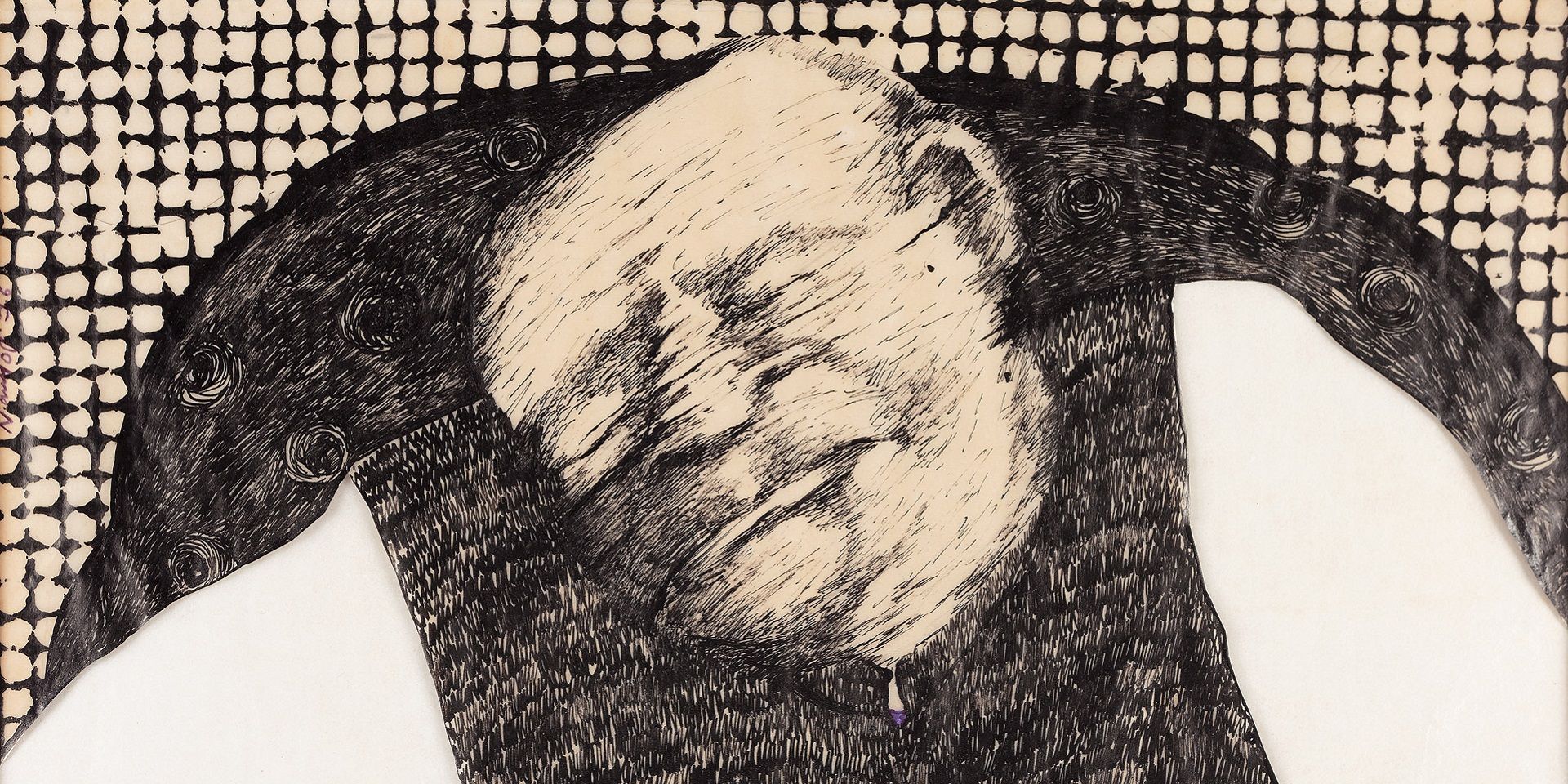

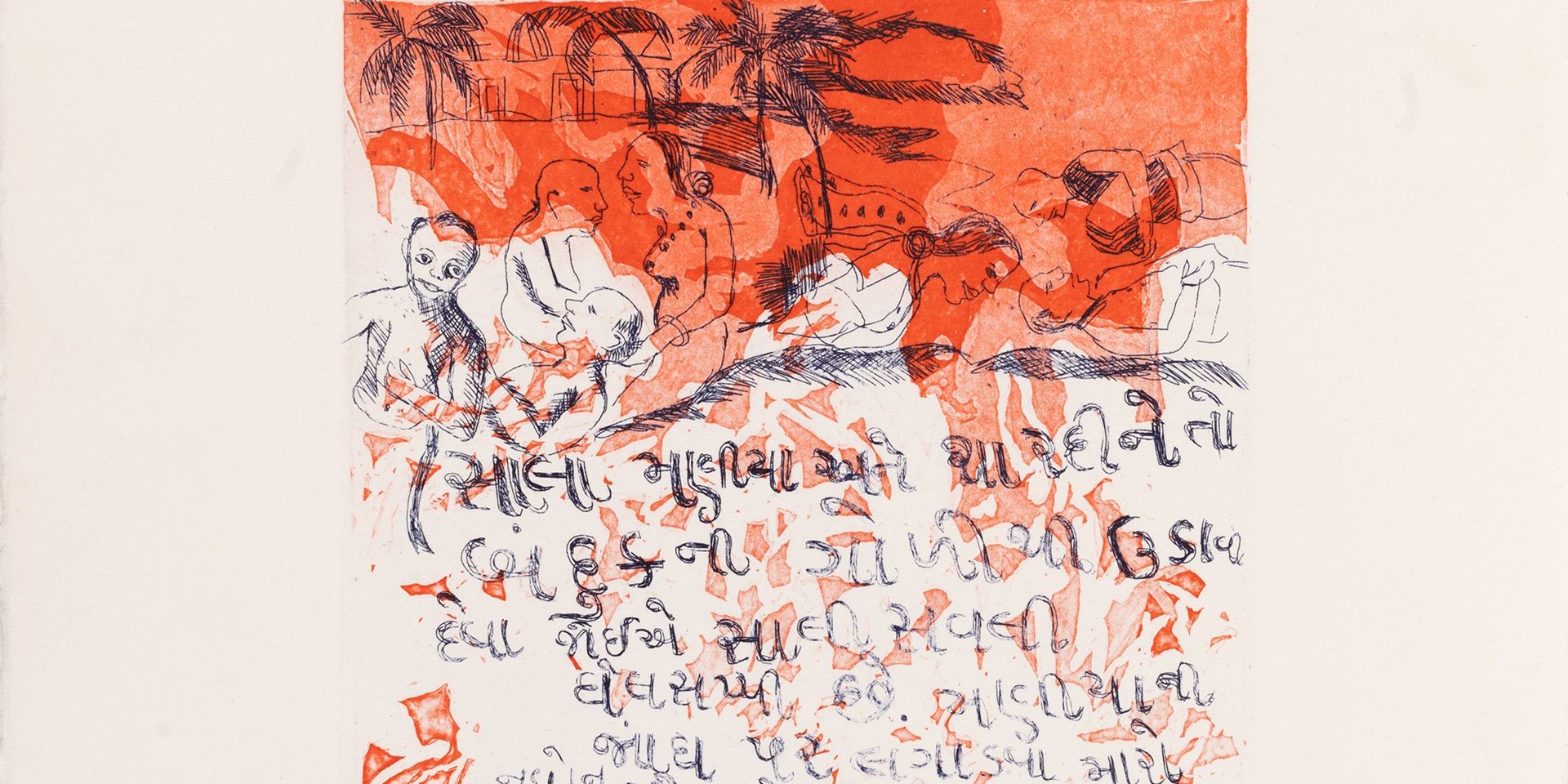

Navjot, Untitled (detail), 1976-77, Ink on paper laid on paper, 20.3 x 31.0 cm. Collection: DAG

Karin Zitzewitz’s book Infrastructure and Form: The Global Networks of Indian Contemporary Art, 1991-2008, takes on the ambitious art historical task of exploring a period characterised by radical shifts in the Indian artworld.

Drawing from various strands of academic thought, especially from anthropologists of network theory [1], the book is written with careful and deliberate attention to method. She claims to be, and even succeeds in, writing an art history that does not flatten the relationship between art and the conditions that make it possible. At the heart of the book is the urge to understand the artistic trends and the nature of the shifts taking place in the Indian artworld between the period of 1991 and 2008 by engaging with ‘infrastructure’—the assemblages and networks that make these shifts possible.

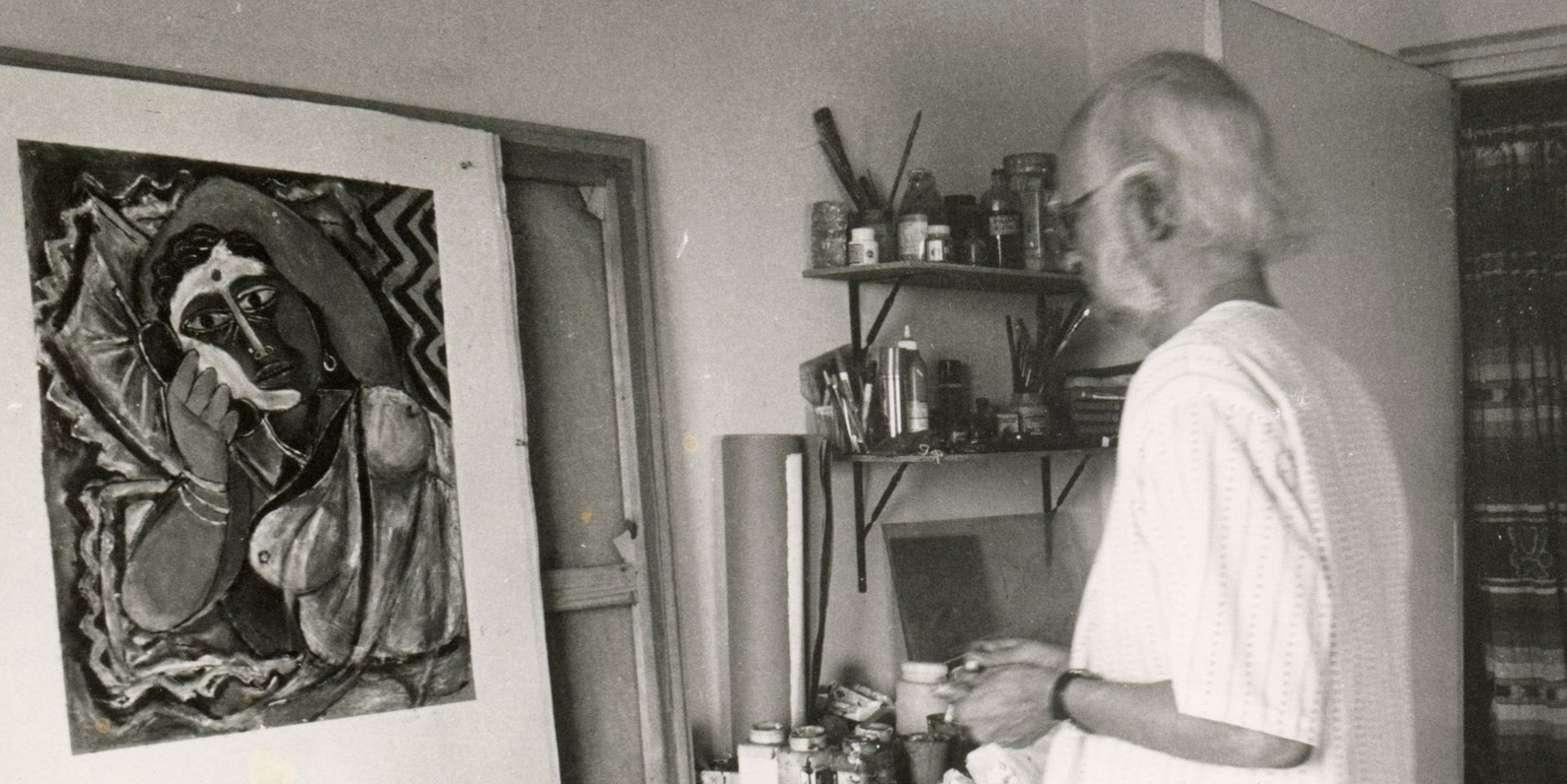

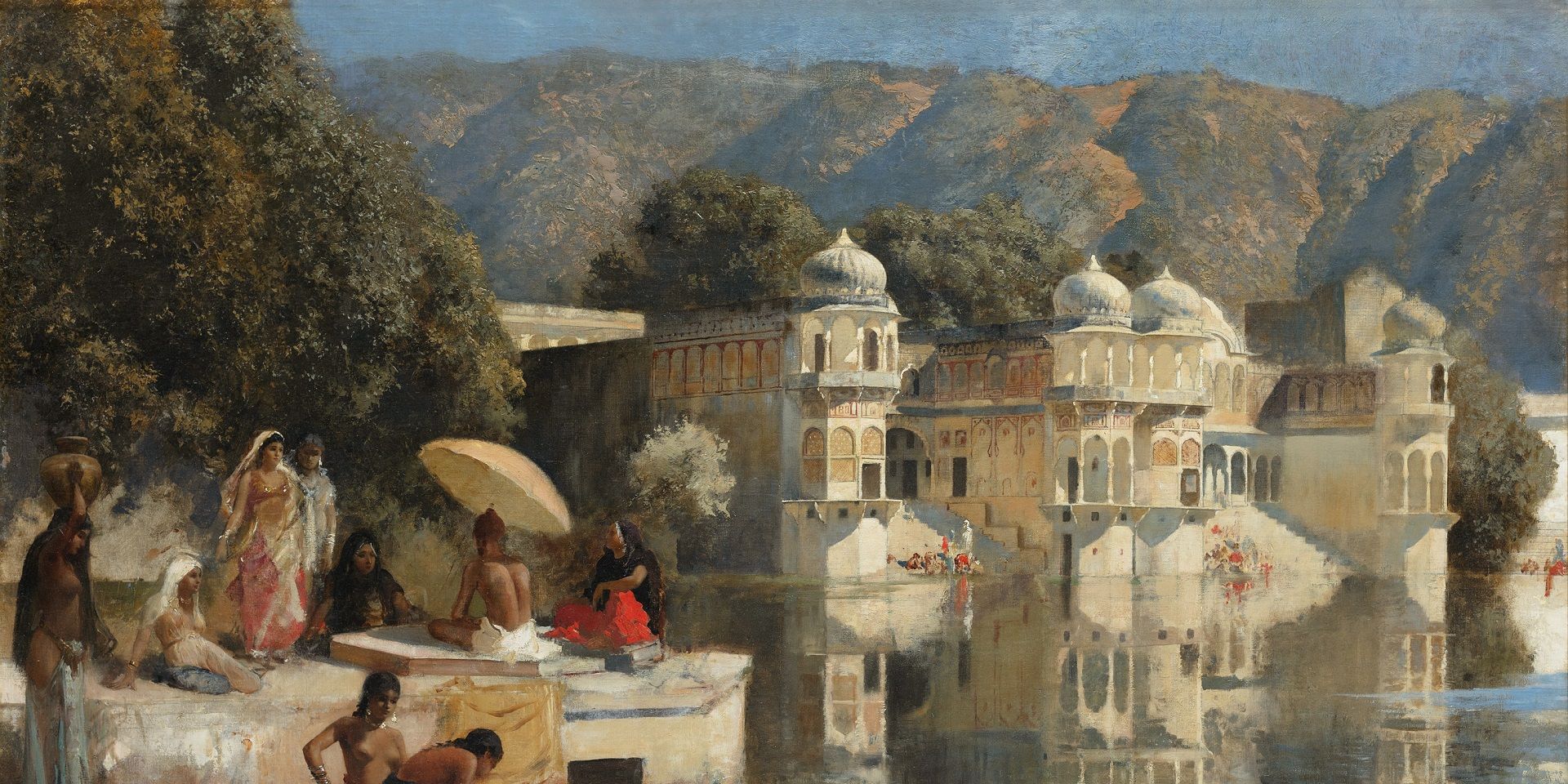

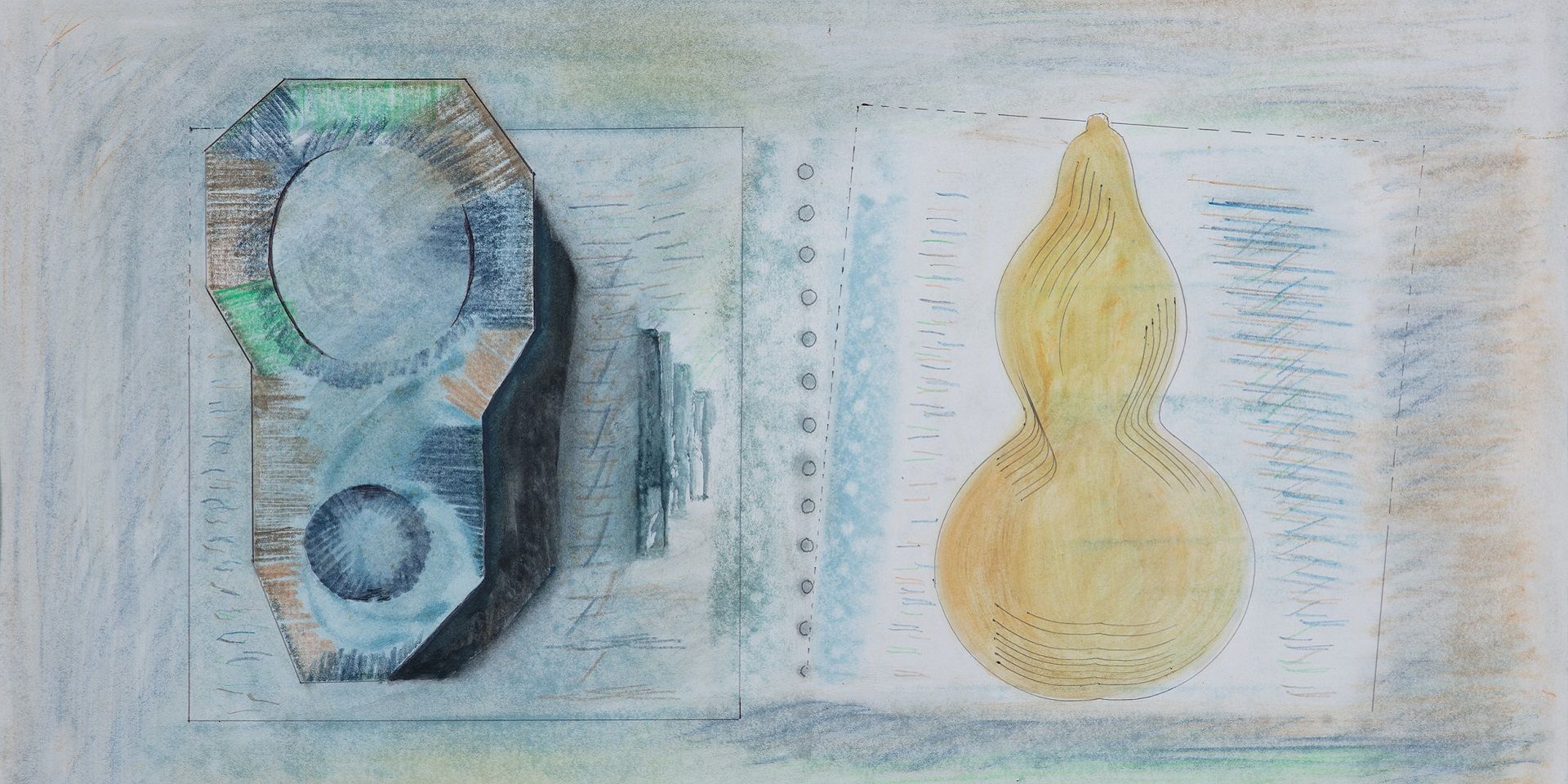

Nalini Malani, Laying a Cable, 1983, Watercolour on paper, 27.9 x 38.1 cm. Collection: DAG

Her book understands ‘infrastructure’ to be fractal in nature—a network, as she says, or more precisely ‘an assemblage through which other assemblages circulate’. This network facilitates the movement of goods, people, or ideas; and her project’s usage of this idea of infrastructure is a rare engagement with the materiality of artistic networks in a discipline which privileges meaning in aesthetic and political senses. Each chapter in the book uses a key assemblage of the material and immaterial elements of art to demonstrate how frameworks of thought, organisational structures, and shifts in either art infrastructures or broader (socio-economic) infrastructures (sometimes both) come together to give rise to new artistic forms. This is achieved through a tight analysis of particular works by key artists in tandem with explorations of discursive and curatorial frameworks, exhibitions, workshops, and political-economic conditions.

|

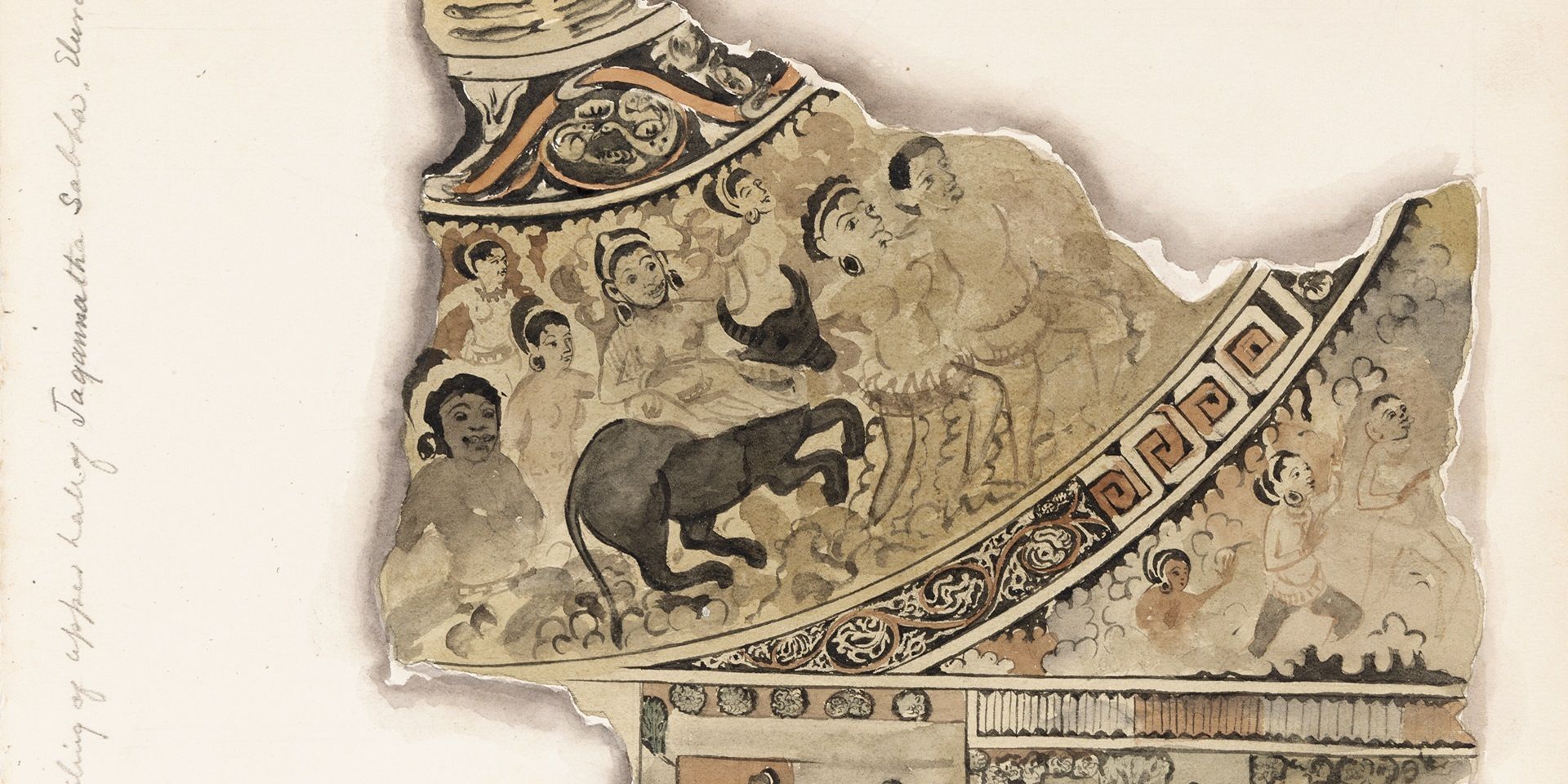

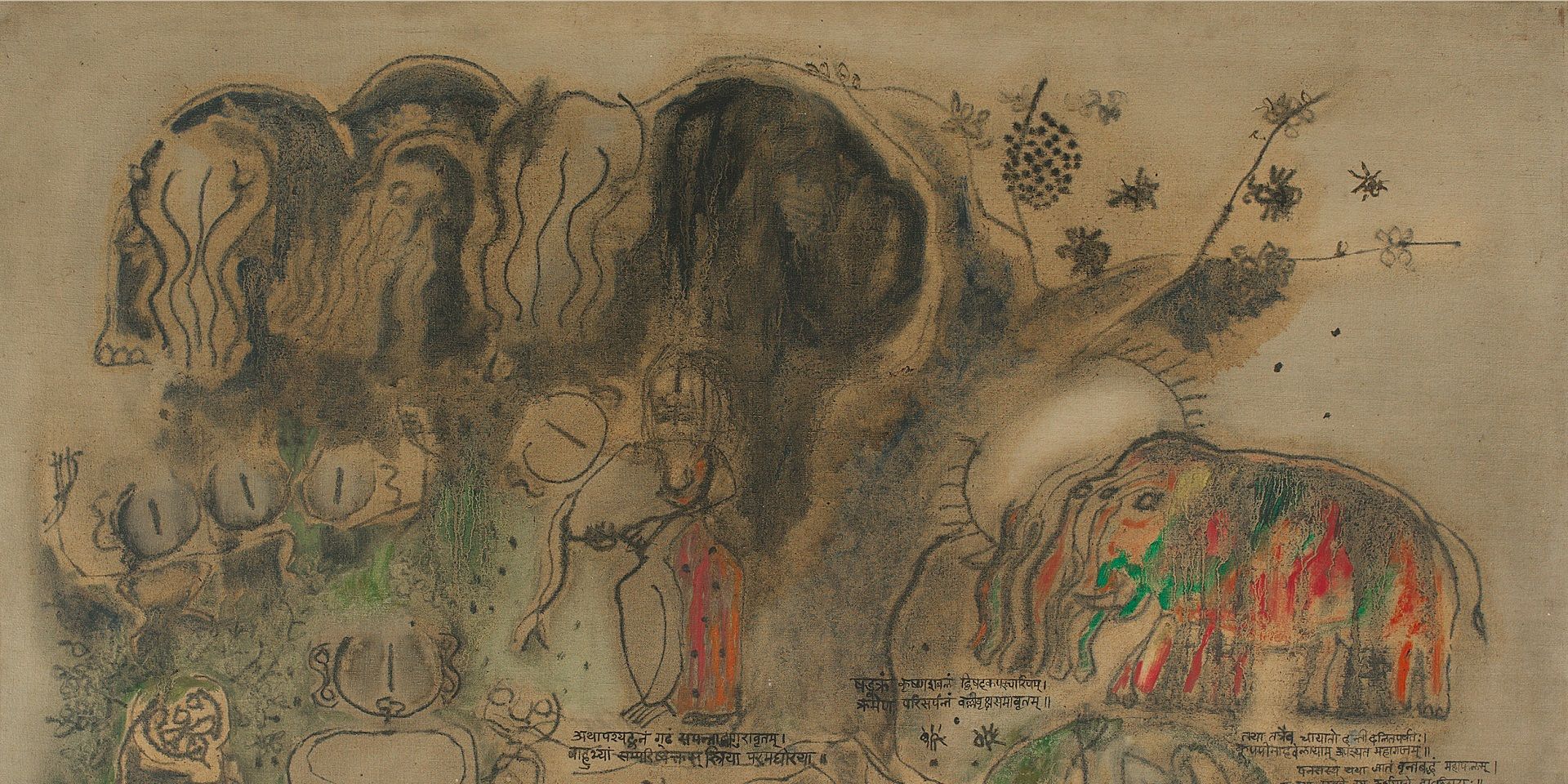

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Devi, 1982. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

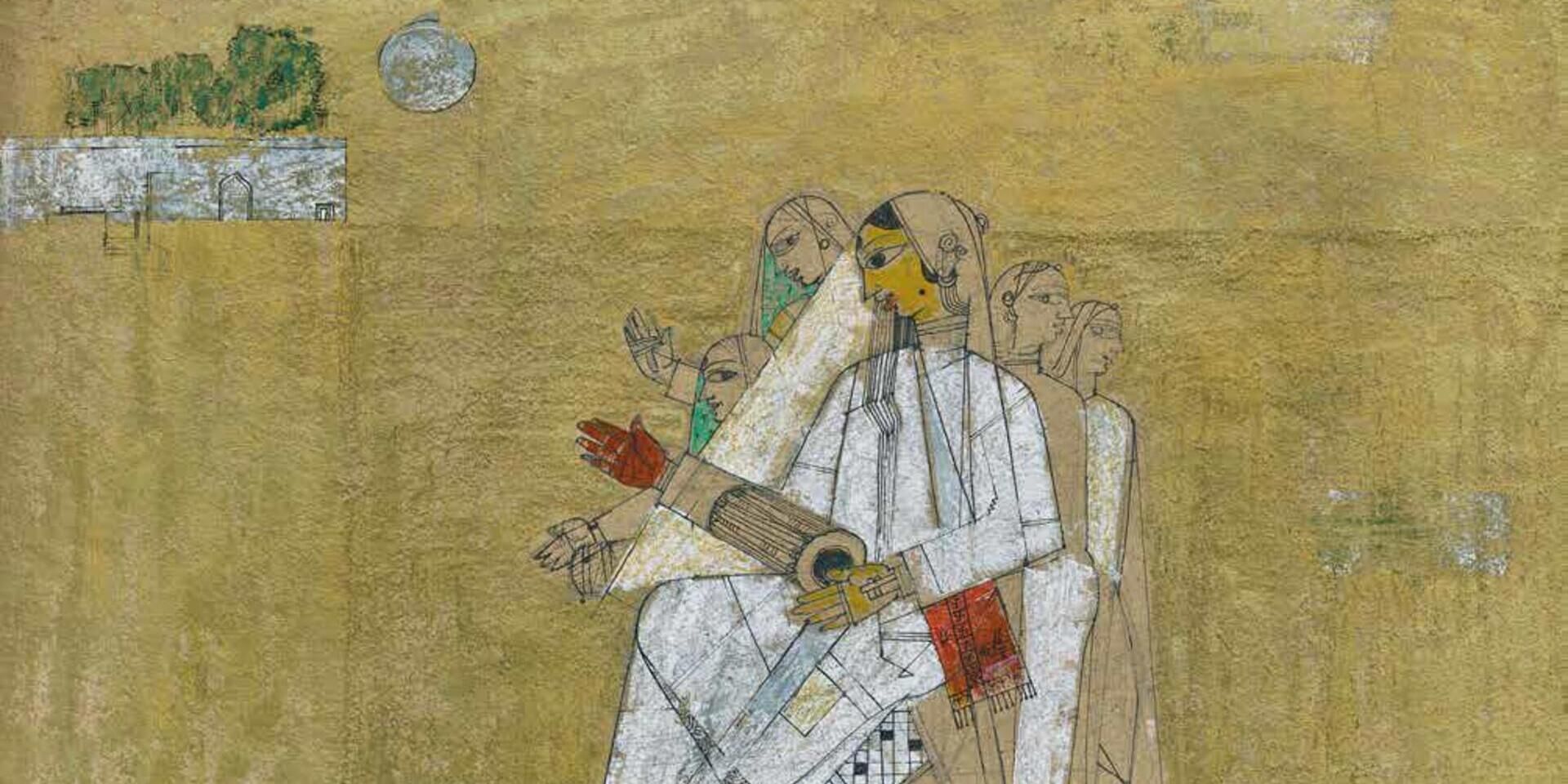

The first chapter in her book leads with two modernist painters—Nilima Sheikh and Nalini Malani, and focuses upon a crucial juncture in their practice. Both Sheikh and Malani’s practice undergo a complex set of changes in this period as they begin to work on a larger scale and in media which was, until then, uncommon in the Indian art scene. Moving beyond painting towards new mediums of installation and performance art in an interdisciplinary fashion, Zitzewitz argues that this shift in their practice is a rejection of the primacy of medium. This move was encouraged and welcomed by an expanded infrastructure for art’s circulation through biennial exhibitions and a proliferation in feminist discourse in writing, theatre and film studies. Zitzewitz also pays careful attention to the emerging curatorial discourse and a network of circulation developed beyond the West through which artistic strategies were being exchanged and connections made.

Sheikh worked extensively with theatre and Malani experimented with performance and installation—both extending the practice of painting to approximate the spatial presence and the aesthetic associated with installation. Their works from this period were displayed at the Asia Pacific Triennial in 1996 alongside Mrinalini Mukherjee’s fibre sculptures. Zitzewitz uses these works as examples to elucidate how Indian artists working with the installation medium departed from the terms in which installation art had been defined so far as an expanded field of sculpture grounded in the works of Richard Serra and Allan Kaprow. For instance, Mukherjee’s towering fibre works are definitely held to be sculptural but their intimate consideration of the capacities of the natural material of jute draws attention to her investment in the materiality of things. Their forms, drawn from the organic world, create an erotic charge that sets up a relationship between the work and the viewer in a way that departs from the modernist aesthetic criteria explored by the American genealogy of installation art. Installations by Malani, Sheikh, and Mukherjee all manifest elements of conceptual material typical of installation art in the 1990s framed by a lively assemblage of feminist scholarship.

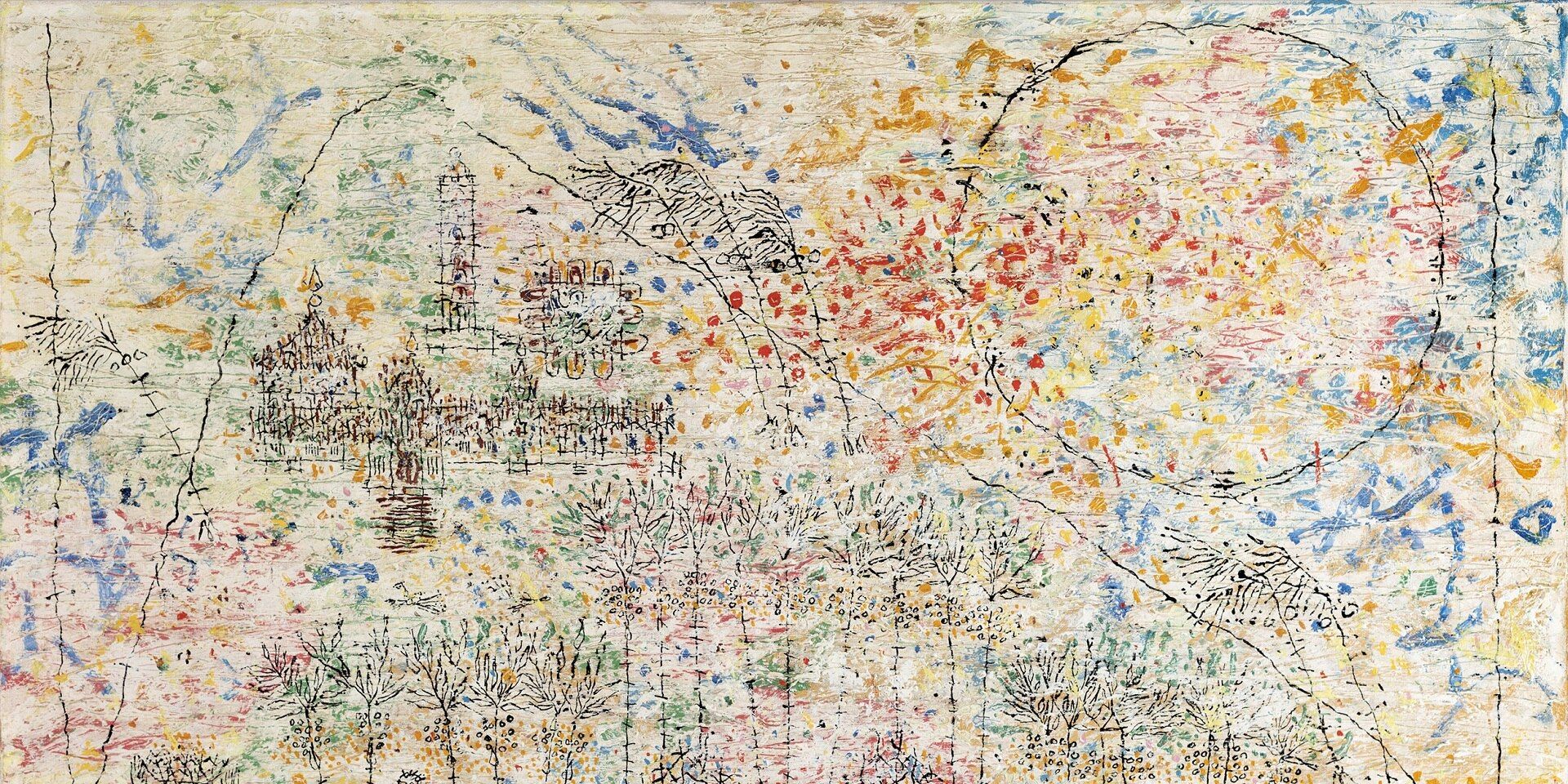

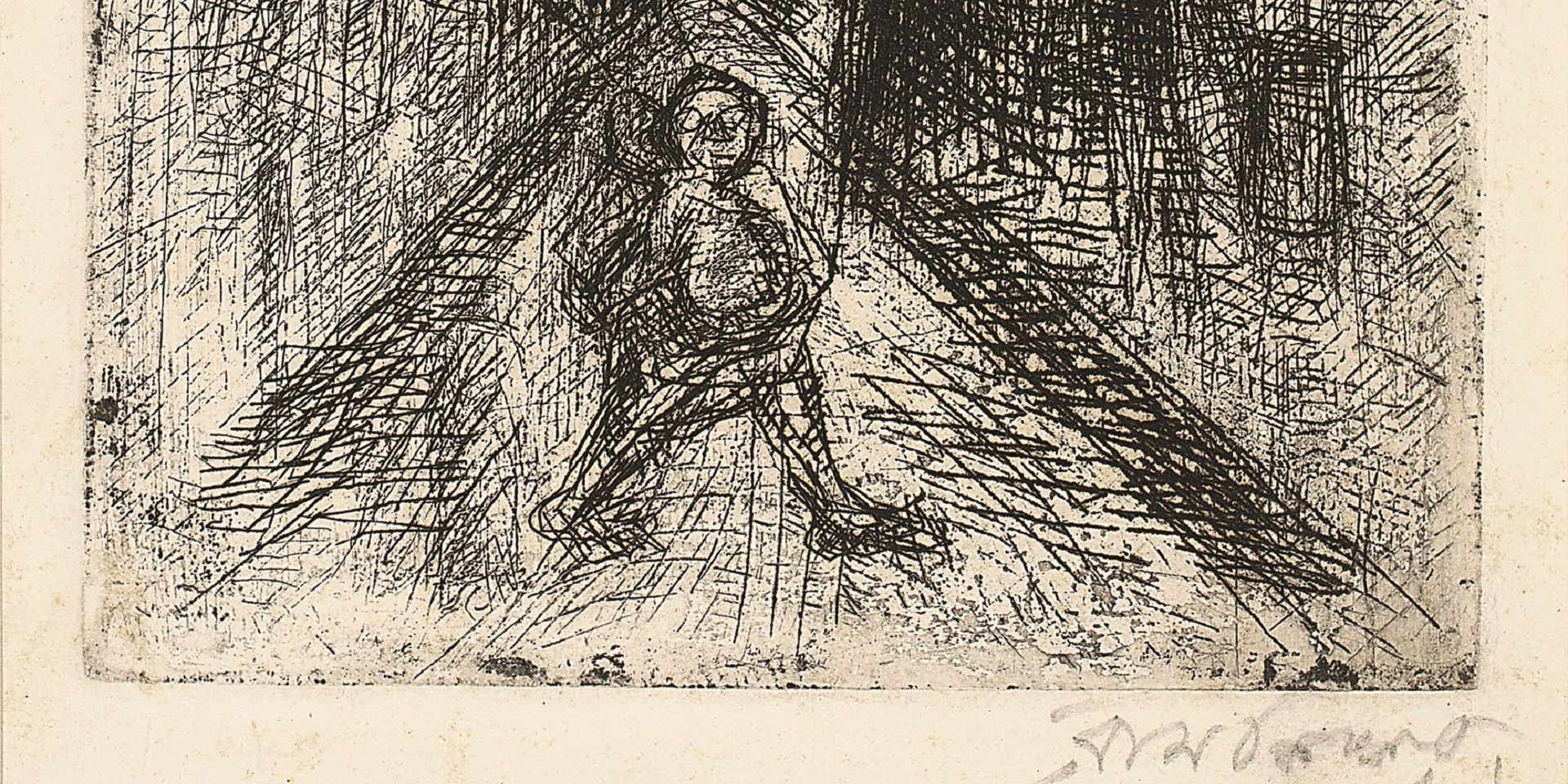

Prabhakar Kolte, Untitled, 2002, Watercolour on handmade paper, 70.4 x 99.6 cm. Collection: DAG

The book pays particular attention to the new landscapes of exhibition that emerged in this period—the APT2 (1996) being one example of an event which was fertile ground for productive friendships between artists—expanding discursive contexts and mutual understandings of contemporary art which led to collaborations both intellectually and in praxis contributing significantly to experimentations in form.

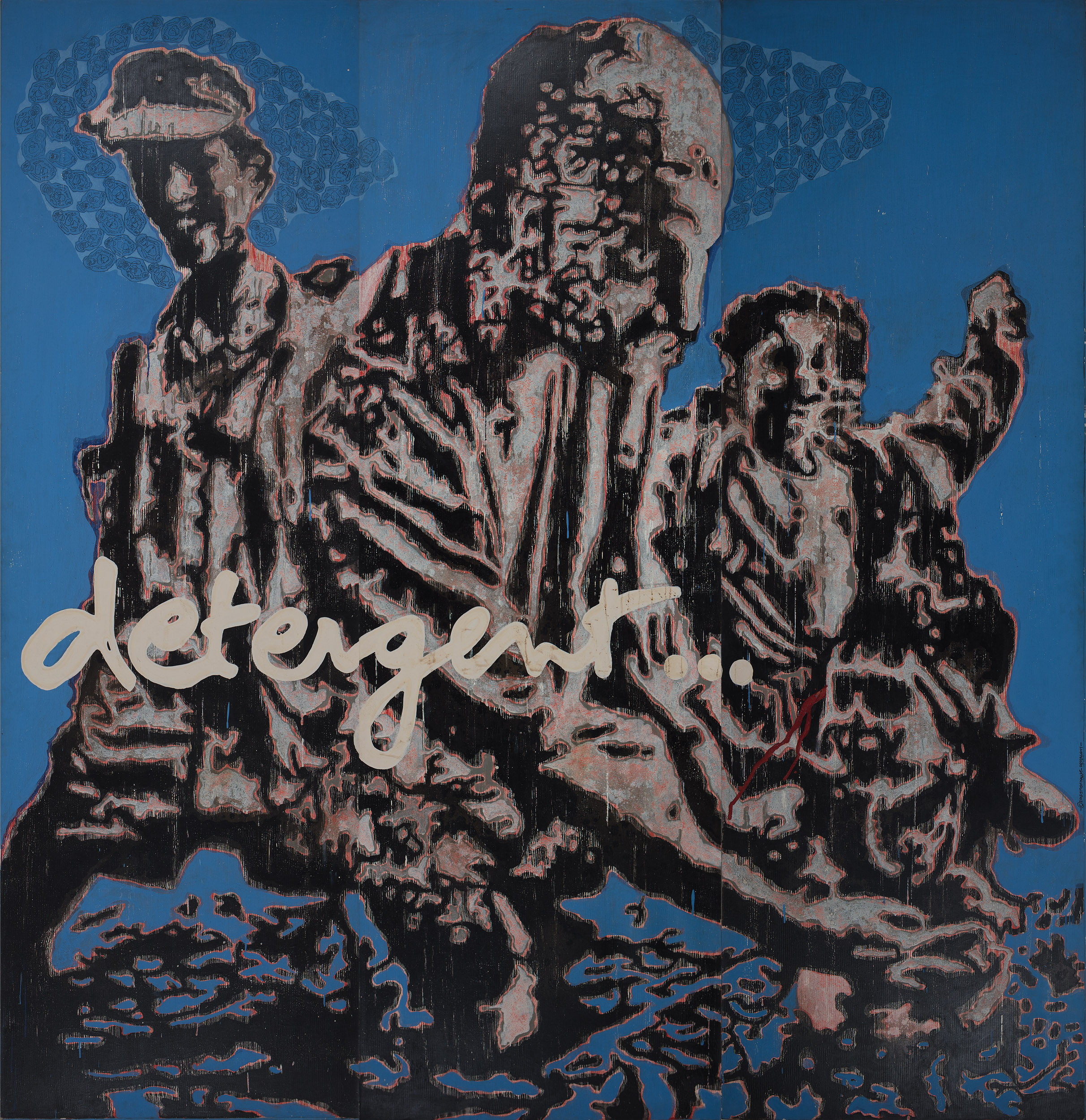

Zitzewitz also considers how material shifts in technology, especially in image (re)production, played a role in the creation of new artistic forms and their circulation. Jitish Kallat’s practice in the 1990s is a rather well-chosen case for such an exploration. Drawing from the J.J. School of Art lineage, Kallat uses his mentor Prabhakar Kolte’s techniques in painting by excavating layers of colour with a palette knife in paintings that play with the reproduced image using xerox machines and photo transfer. His contemporary, Atul Dodiya too, in his own way, explores the effects of technology in image making and circulation through the medium of painting. The post-liberalisation infrastructural media landscape in India—with a proliferation in cable T.V. programming, duplication technologies like photocopying and facsimile-making, and the introduction of personal computing and internet hypertext—does not sound the death knell for painting and rather leads to interesting new formal experimentations as Zitzewitz explores. Kallat and Dodiya incorporate in their paintings, both in medium and in form, these new technological innovations and the visuals and aesthetics produced by them.

Jitish Kallat, Detergent/Triptych, 2003, Acrylic, enamel, marble dust and marker on canvas, 259.1 x 251.5 cm. Collection: DAG

Atul Dodiya, The Wall, 2007, Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 182.9 x 243.8 cm. Collection: DAG

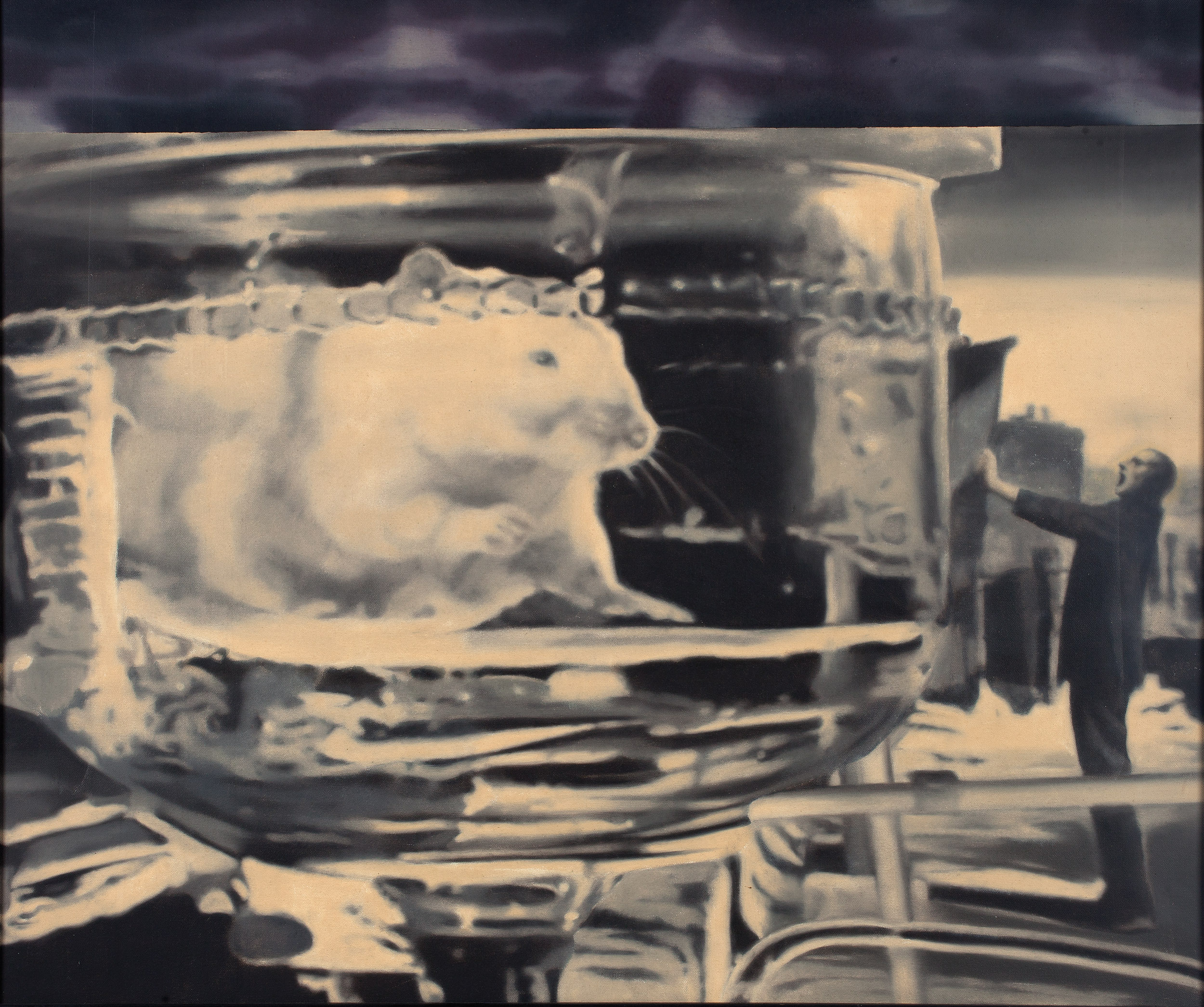

Developing parallelly are practices where images are based on photographs, and often combined with text, which is sometimes termed as ‘photorealism’ or as Nancy Adajania terms it ‘new mediatic realism’, observed in works by Ranbir Kaleka and T.V. Santhosh. Alongside the material shifts in infrastructure which are discernible in these works, there is an emergent infrastructure of thought which focuses on meanings of place, using the concept of ‘locality’ as a critique of globalisation. All the works discussed here are rife with signifiers of urban life rooted in this concept of locality where the city is the spatial-cultural unit of choice.

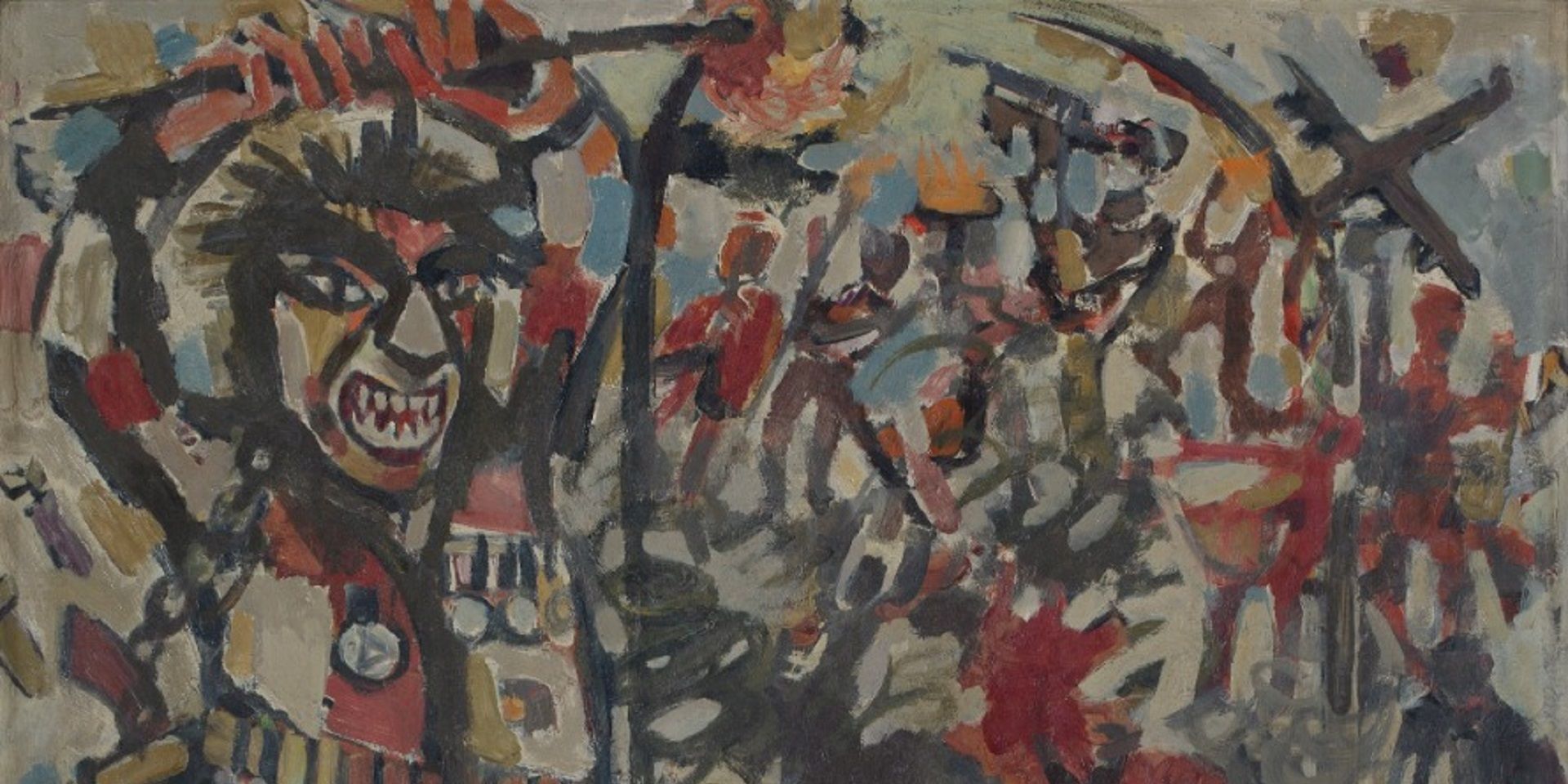

T. V. Santhosh, Untitled, 2003, Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 91.4 cm. Collection: DAG

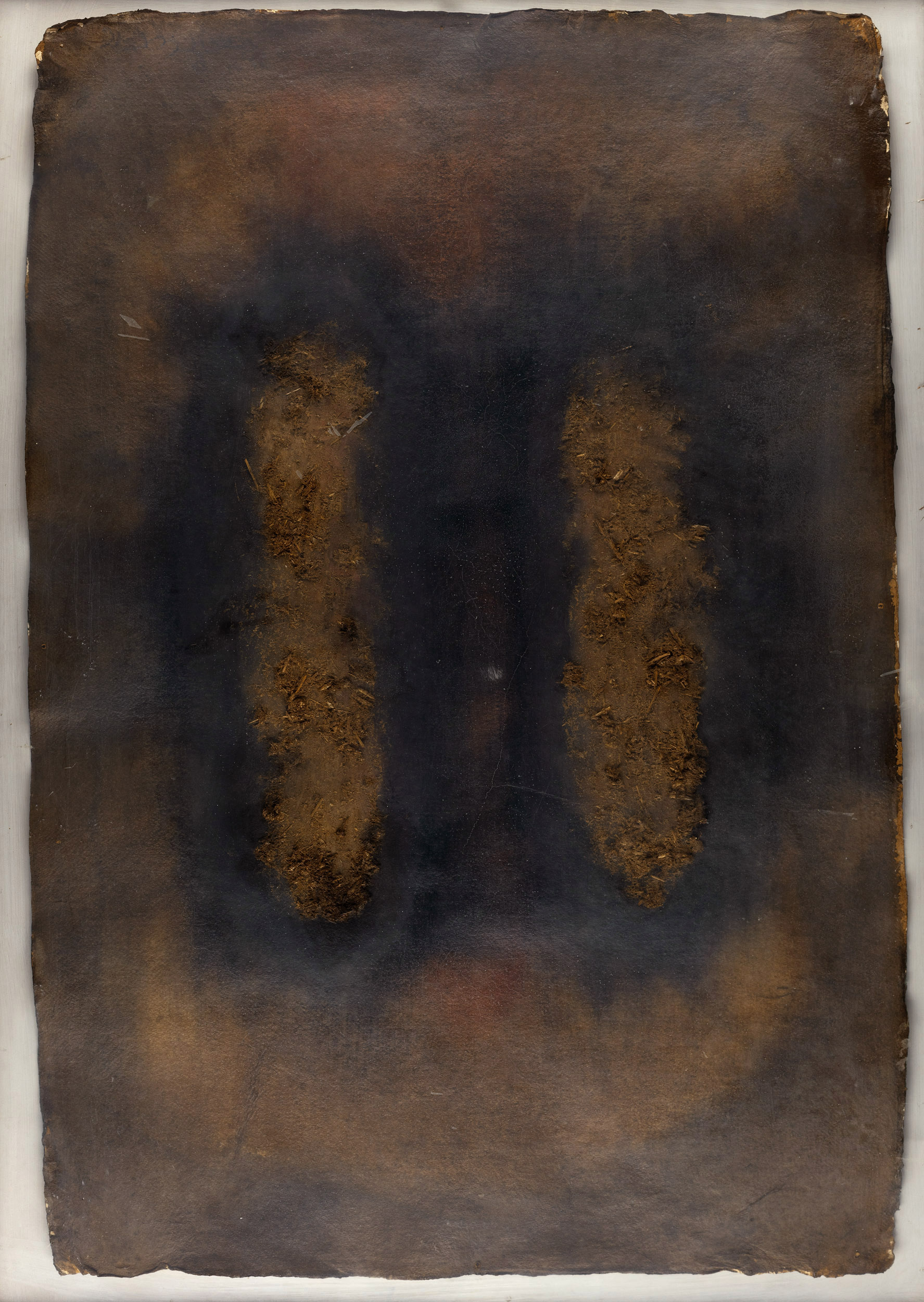

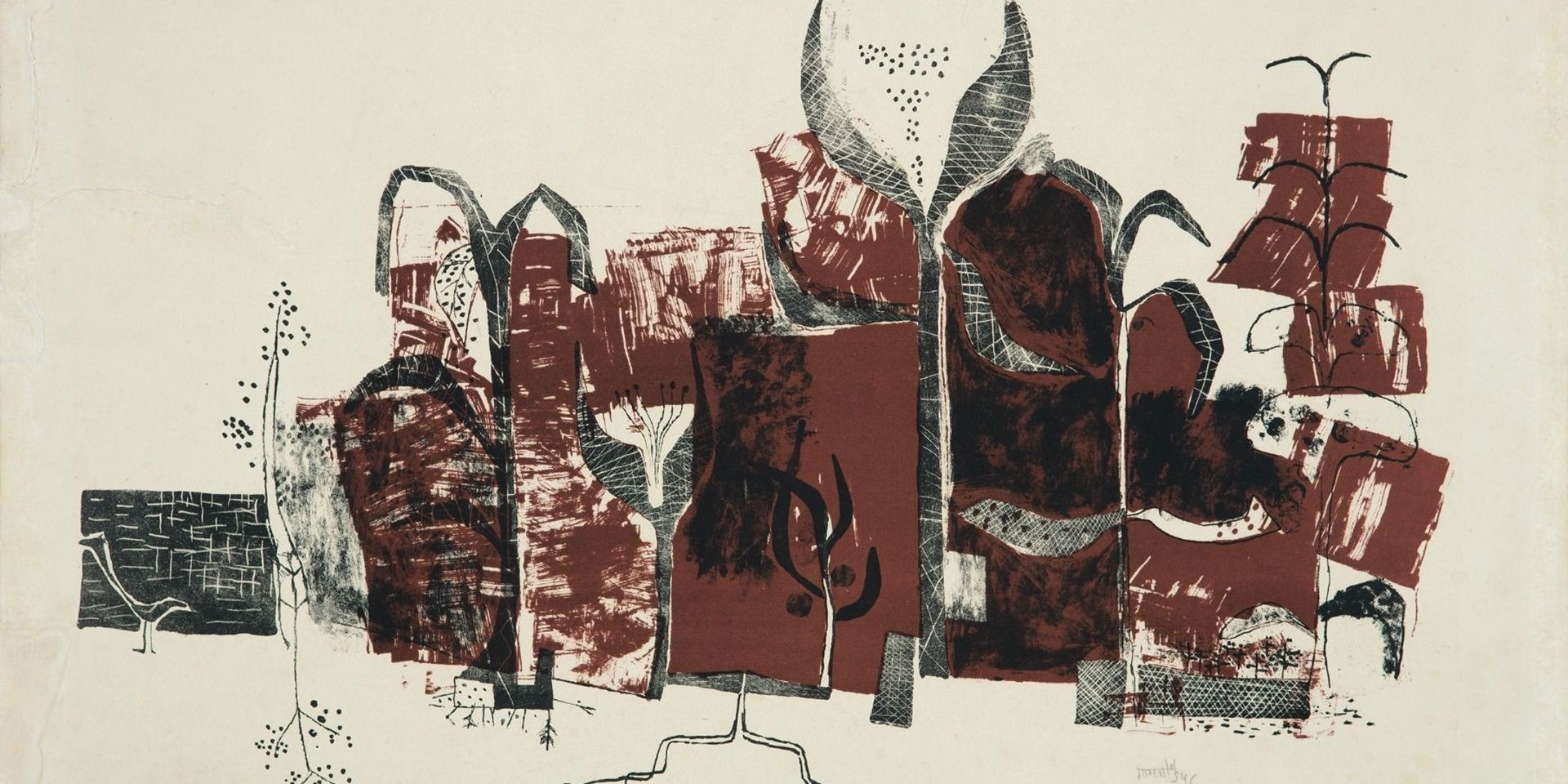

Having spent considerable space concerning herself with questions of medium, Zitzewitz also navigates practices whose principal focus is materiality. Subodh Gupta and Sheela Gowda’s use of cow dung in their practice, whether in installation, painting, or performance, is concerned with the materiality of the substance rather than its capacities as an artistic medium. Both their works with cow dung ground the meaning of the substance in a type of labour that was seemingly being threatened by new economic and social formations, and are therefore rooted in a specific socio-economic infrastructural reality. Although many twentieth-century artists such as K.G. Subramanyam, Ramkinkar Baij and others experimented with materiality, especially with ‘poor materials’ [2], Gupta and Gowda’s works are representative of a material turn in the Indian art scene which is no longer dominated by painting and questions of representation. This is partly facilitated by the newly emerging productive institutional form of the international artist workshop which championed the production of materials-based, site-specific, and often ephemeral works.

|

Subodh Gupta, Untitled, Cow dung and watercolour on handmade paper, 105.4 x 71.1 cm. Collection: DAG |

Interwoven throughout the book, is a close attention to the infrastructures of the art market and patronage, including the setting-up of commercial galleries, auction houses, and other institutions that sustain and indeed encourage these artistic shifts. Zitzewitz quotes Kavita Singh’s discussion of how it is the market that produces art historical discourse in the absence of public institutions to take up that role. Singh avoids being dismissive of the art-historical work done by commercial entities by acknowledging that their efforts go beyond their self-interests. Zitzewitz's approach meaningfully engages the scope and method of how organisations do so taking great care to navigate the nuances and the layers of the complex web of assemblages at play. She productively punctures the hard separation between analysis of artistic practice and concerns of the art world by probing the complicated relationship between the infrastructure that makes possible the creation, understanding, and circulation of art, and its form.

Ranbir Singh Kaleka, Marking the Frame: The Secret History of Shape Shifters, What Belongs in Which Hand?, 2014, Digital collage-painting in archival inks and oils on canvas, 137.7 x 612.1 cm. Collection: DAG

[1] Network theory is a field of study in mathematics, computer science, physics, sociology, and various other disciplines that deals with the analysis of complex networks. A network is a collection of nodes (or vertices) and edges (or links) that connect pairs of nodes. These nodes and edges can represent a wide range of entities and their relationships, such as computers and internet connections, people and social interactions, or neurons and neural connections in the brain.

[2] ‘poor materials’ refer to easily and regionally available materials with little commercial cost or value, and which are often organic in nature

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Essays on Art

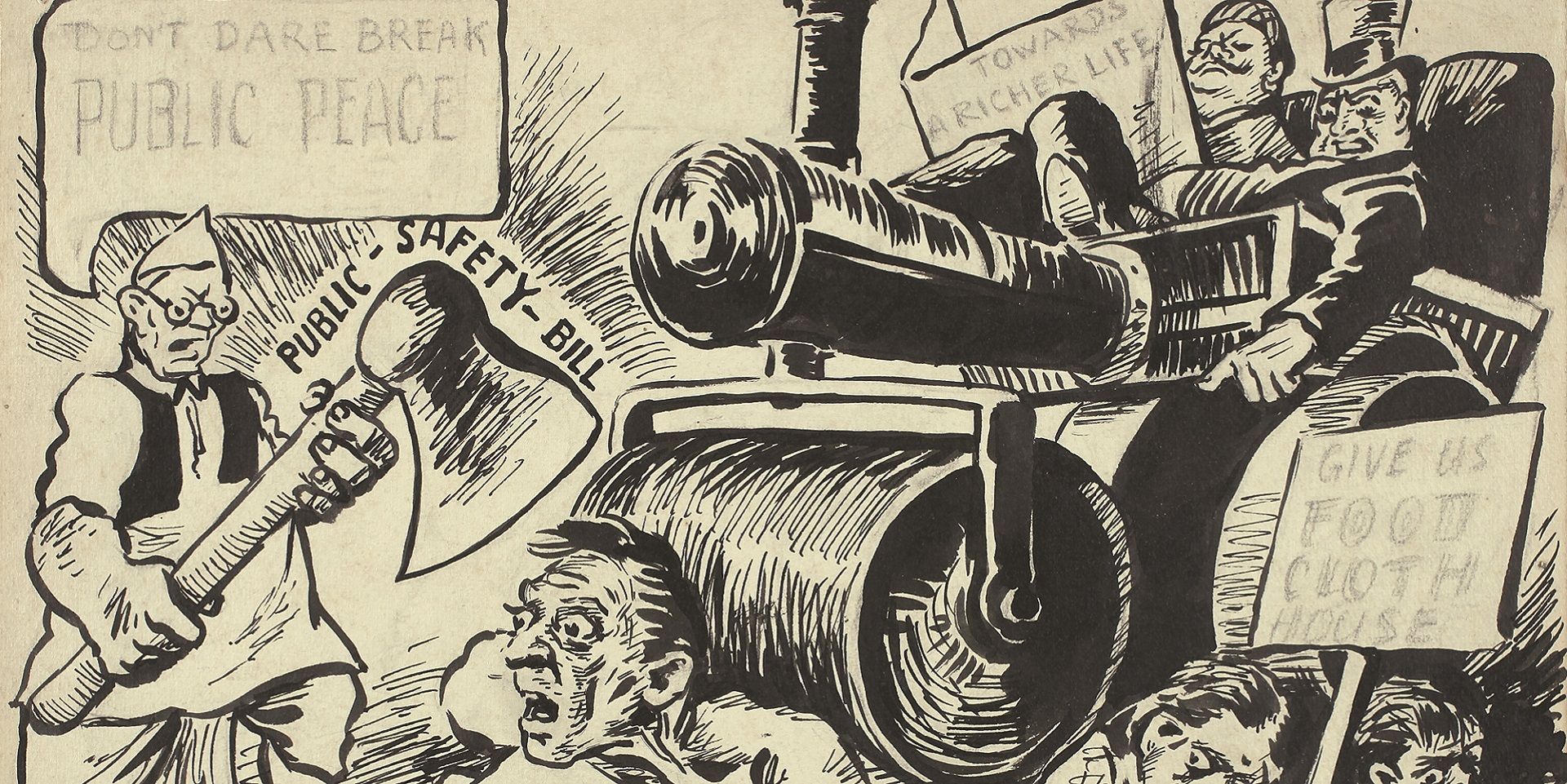

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024