Sketching a Temple: Nandalal Bose’s Konark album

Sketching a Temple: Nandalal Bose’s Konark album

Sketching a Temple: Nandalal Bose’s Konark album

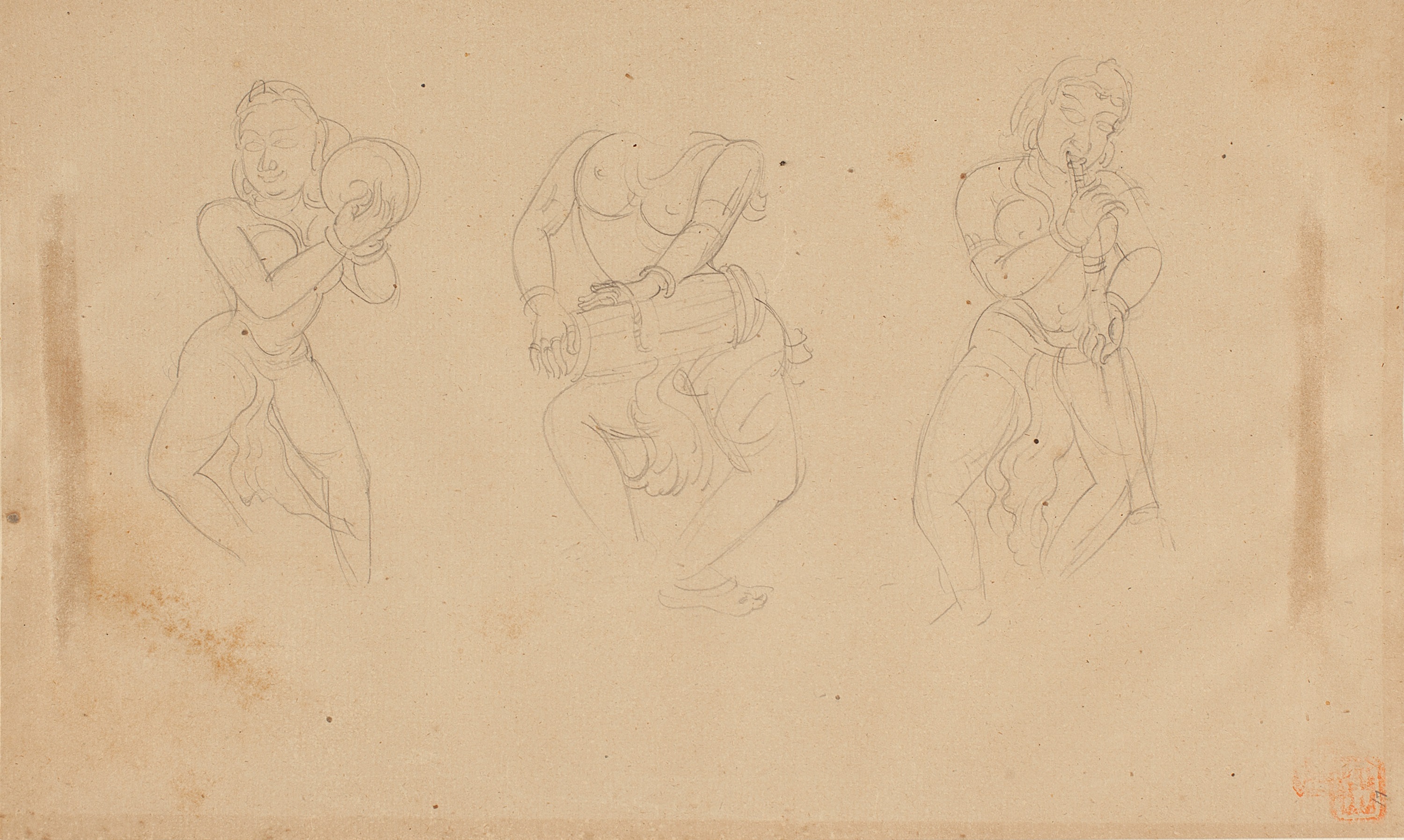

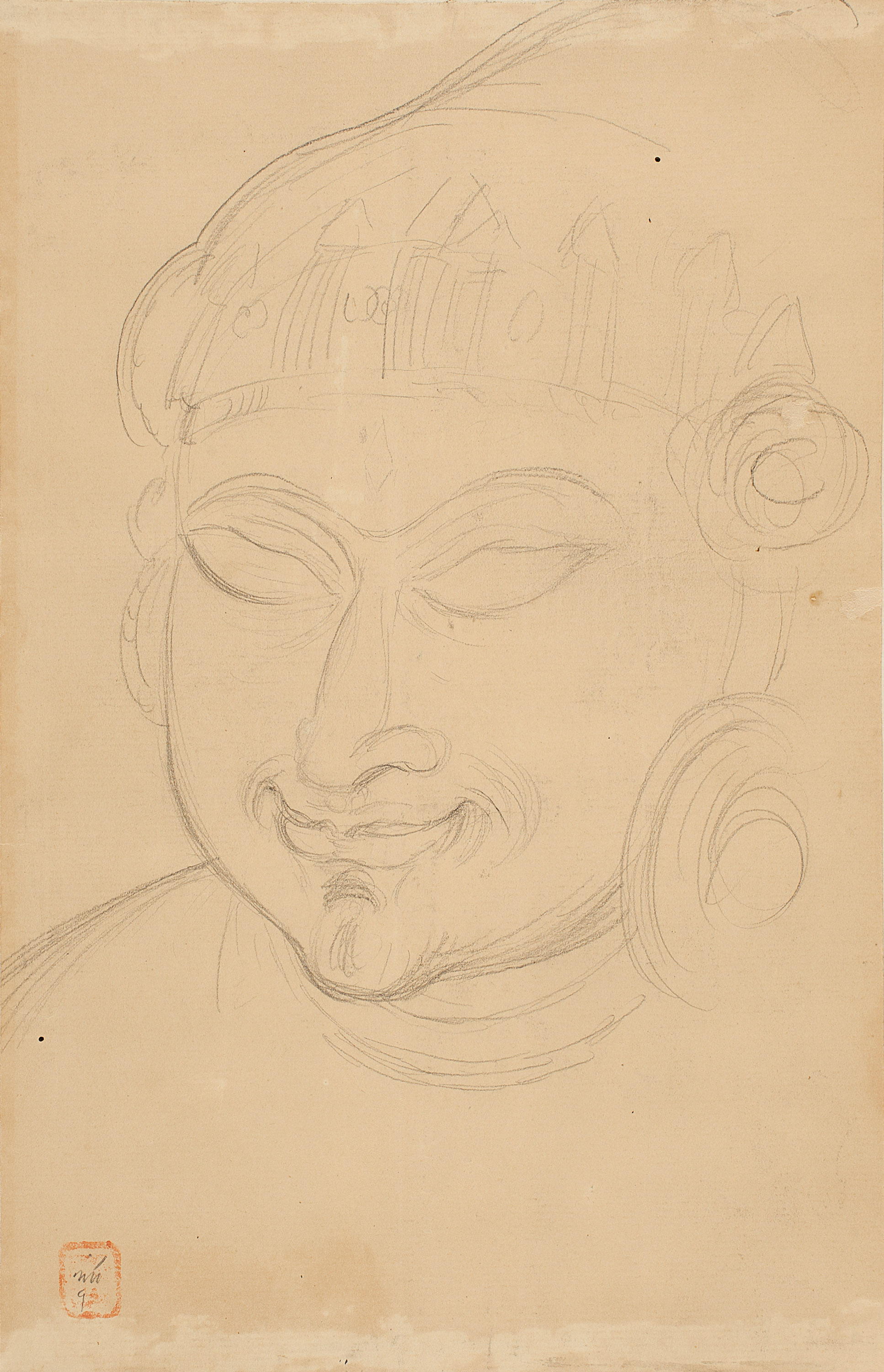

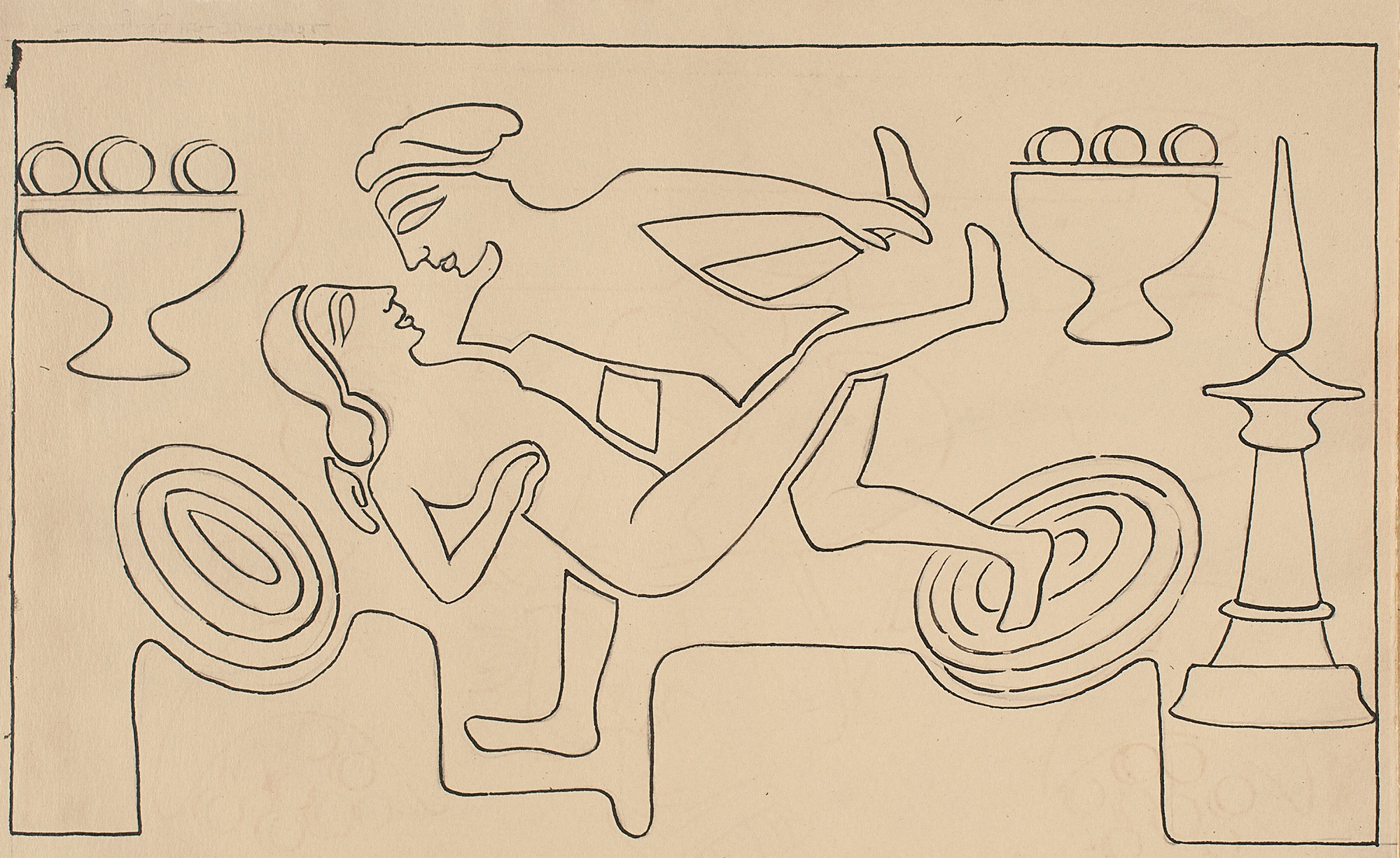

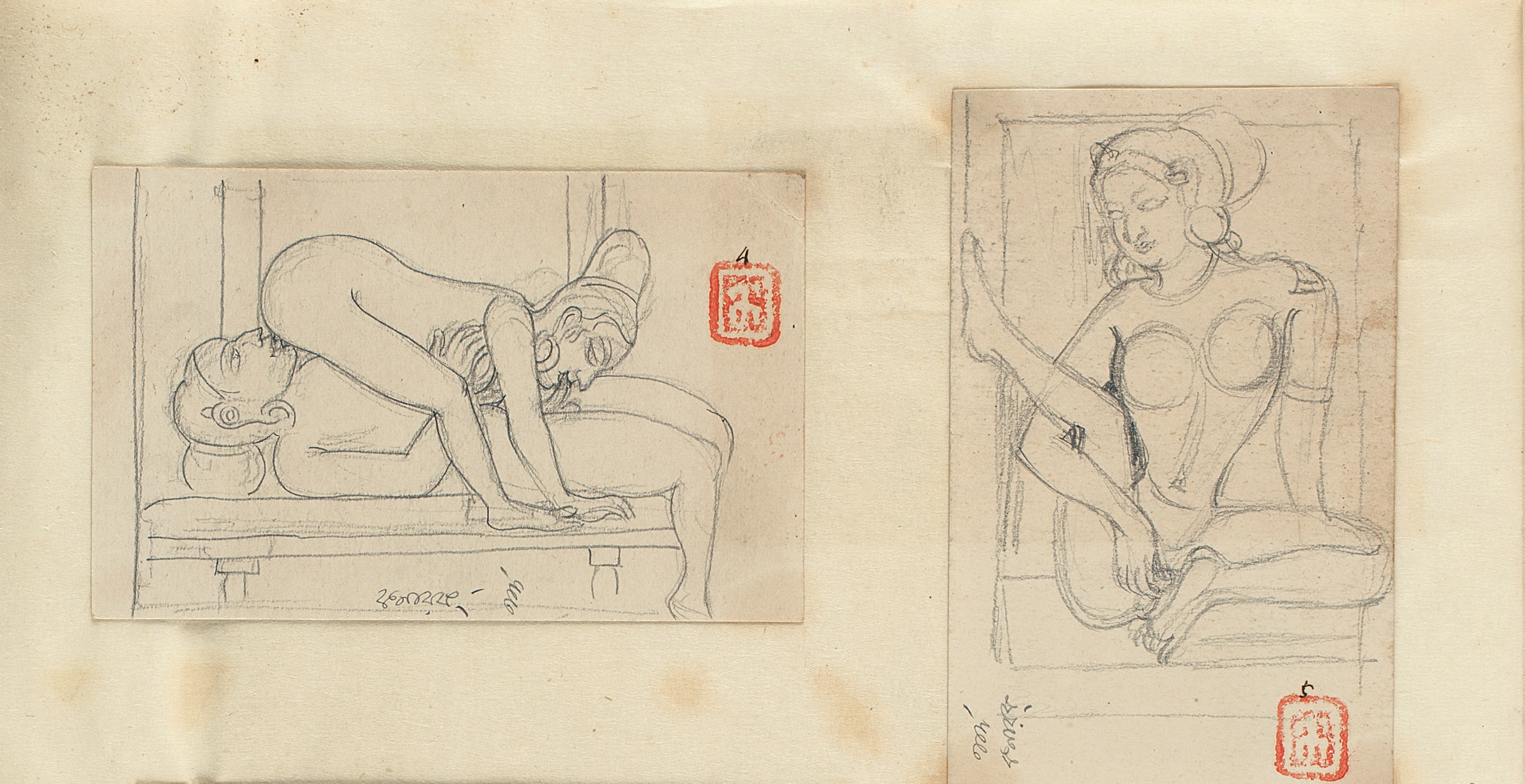

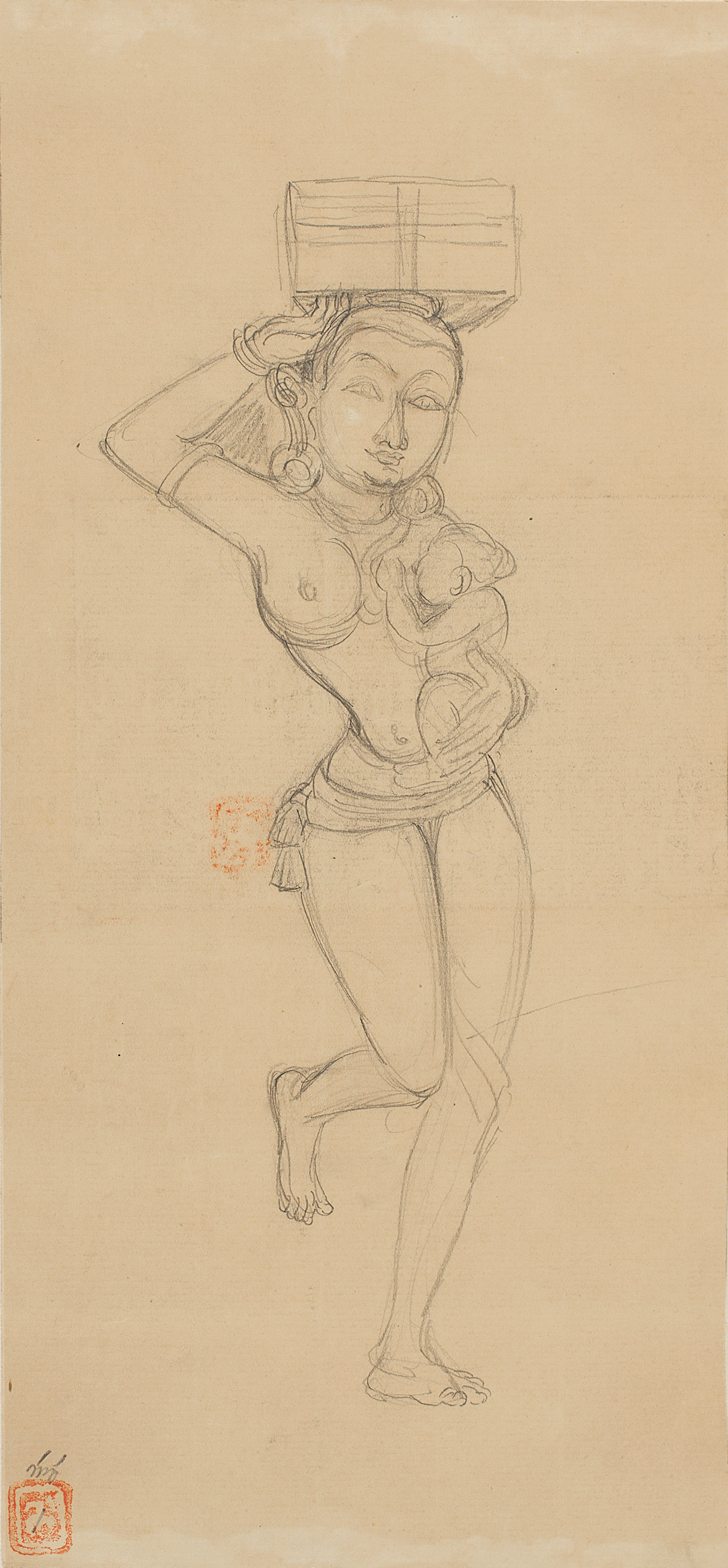

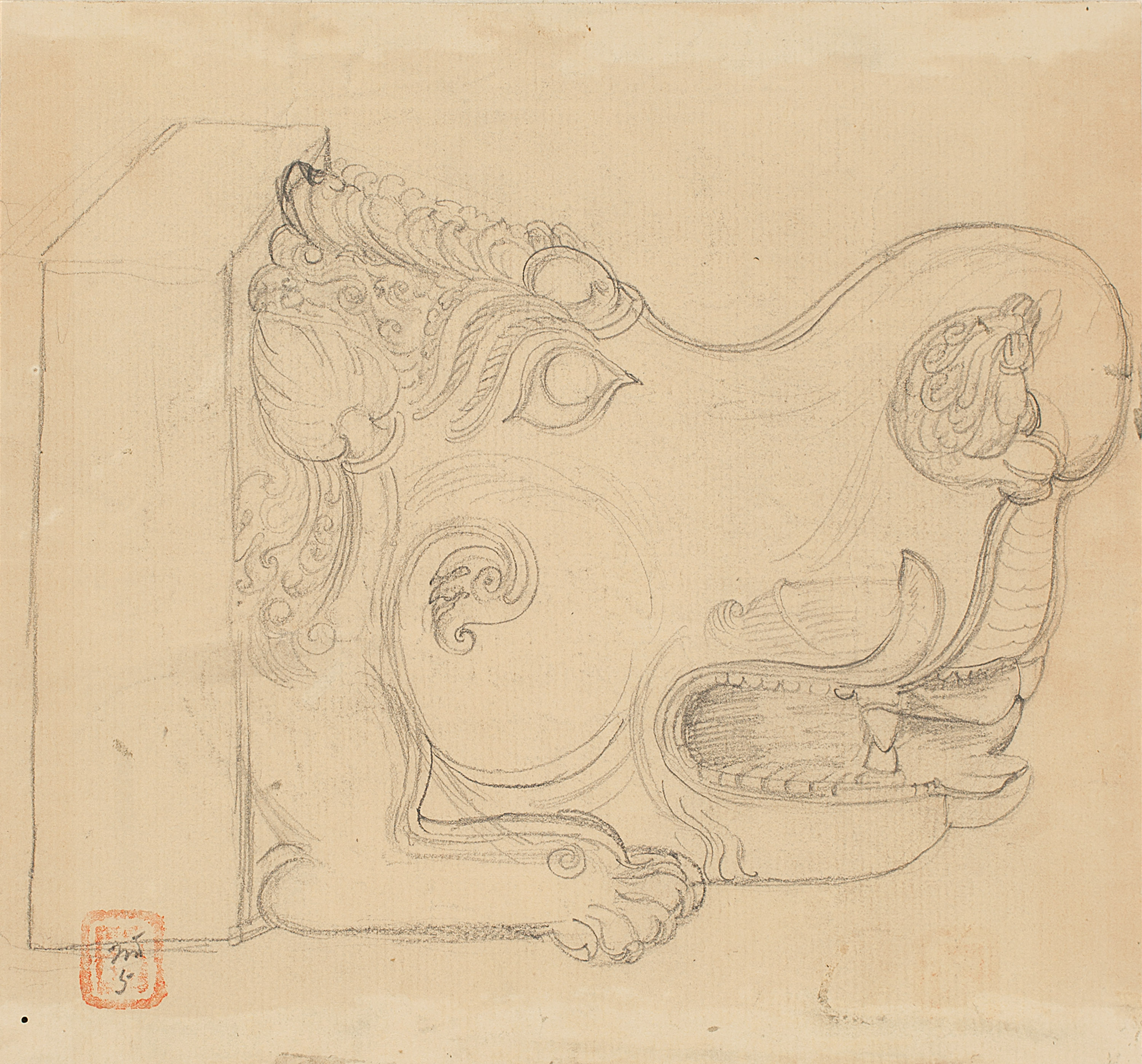

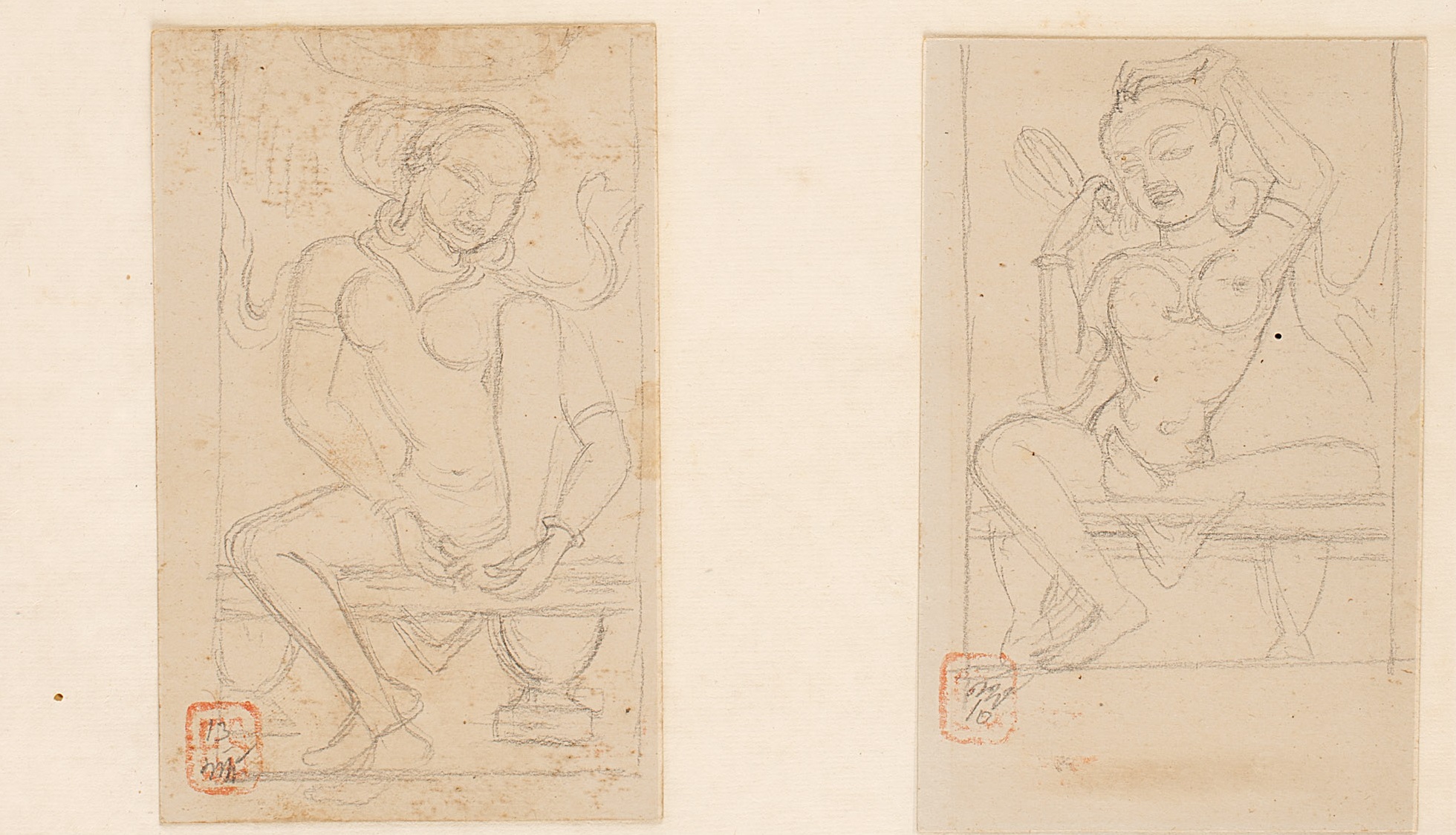

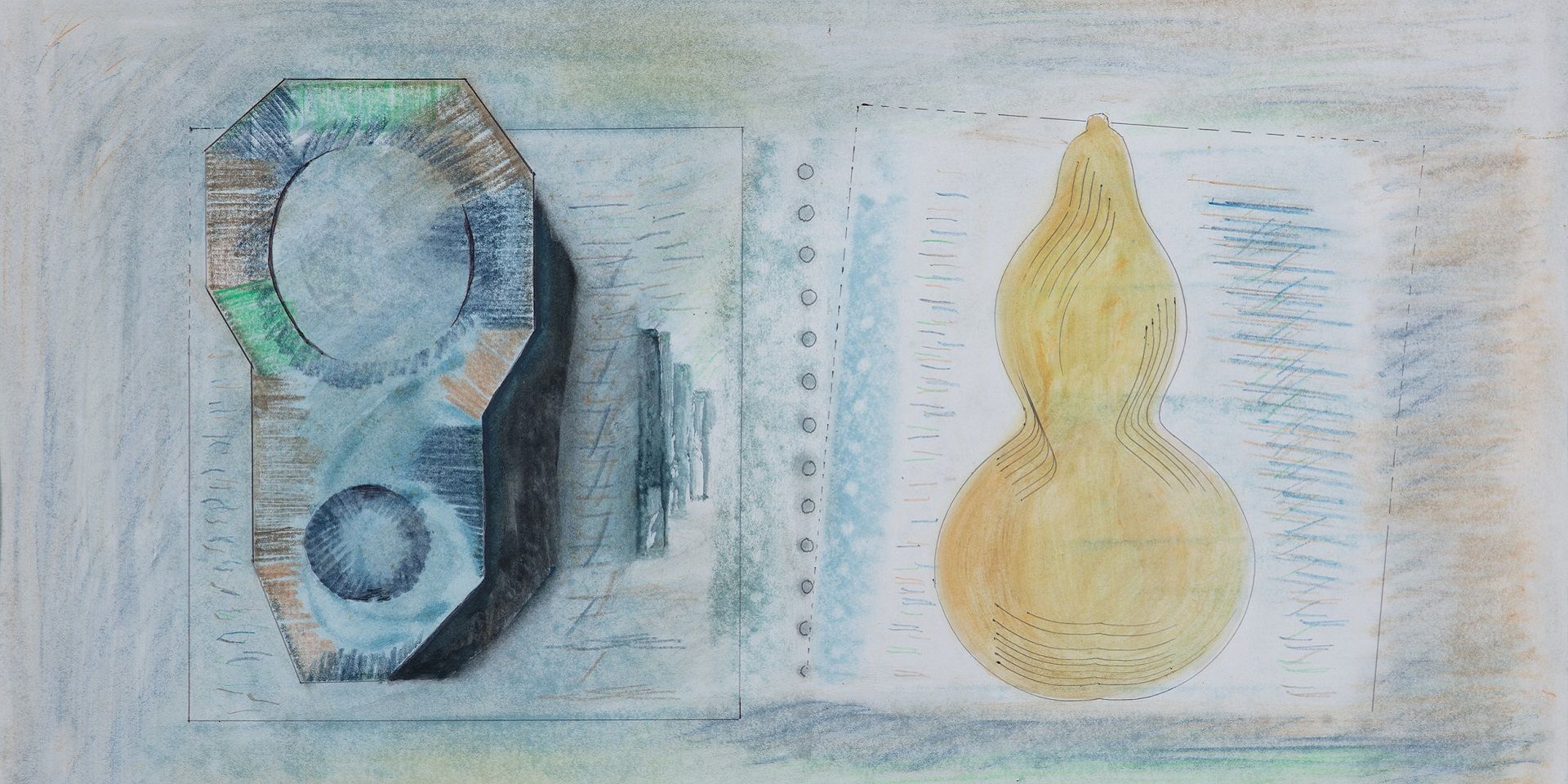

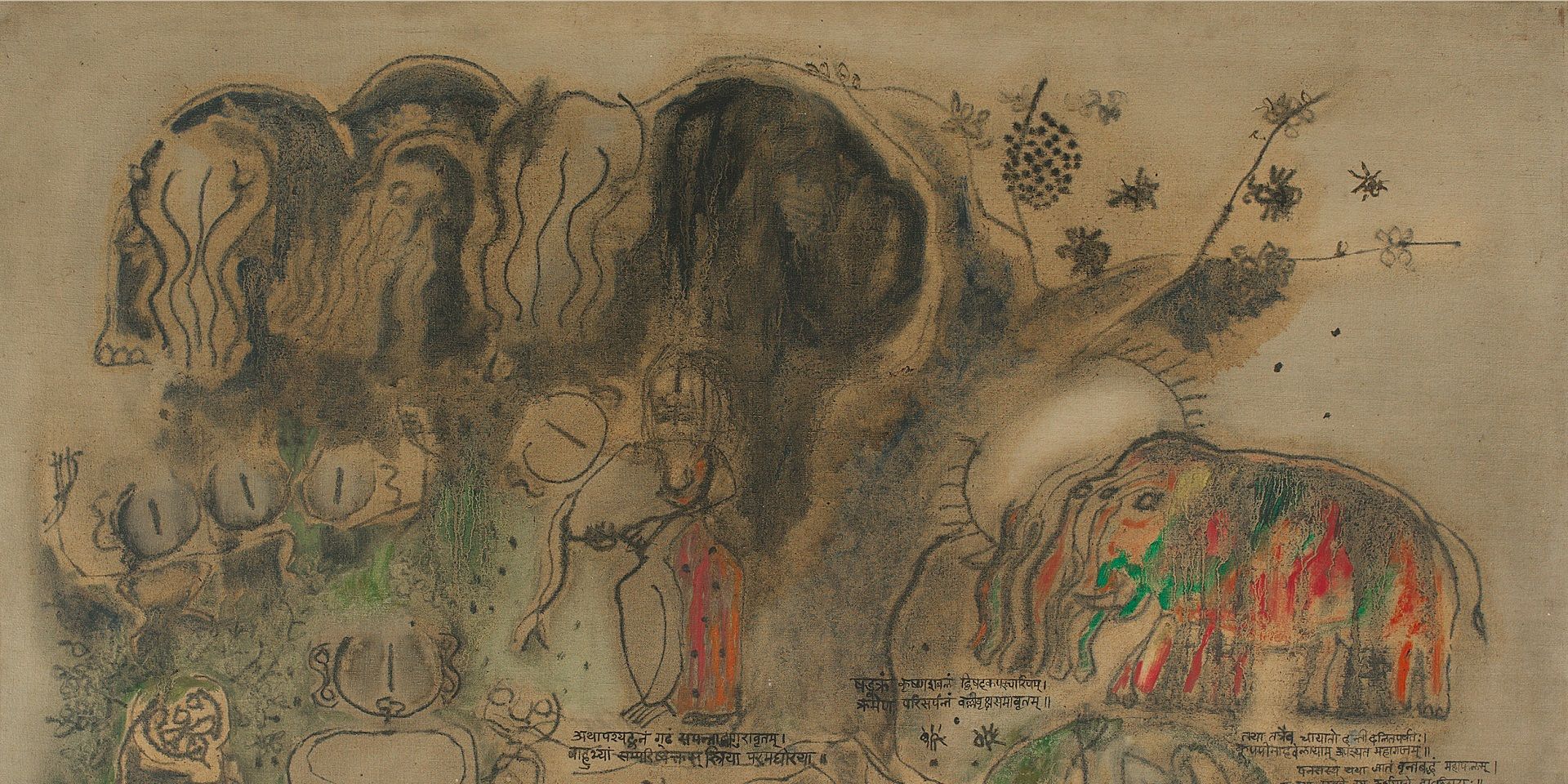

Nandalal Bose, from Konark mandir (Sketch Book), Graphite on paper, 1931. Size per sheet: 13.2 x 8.0 in. A set of 93 (76 obverse) sketches. Collection: DAG

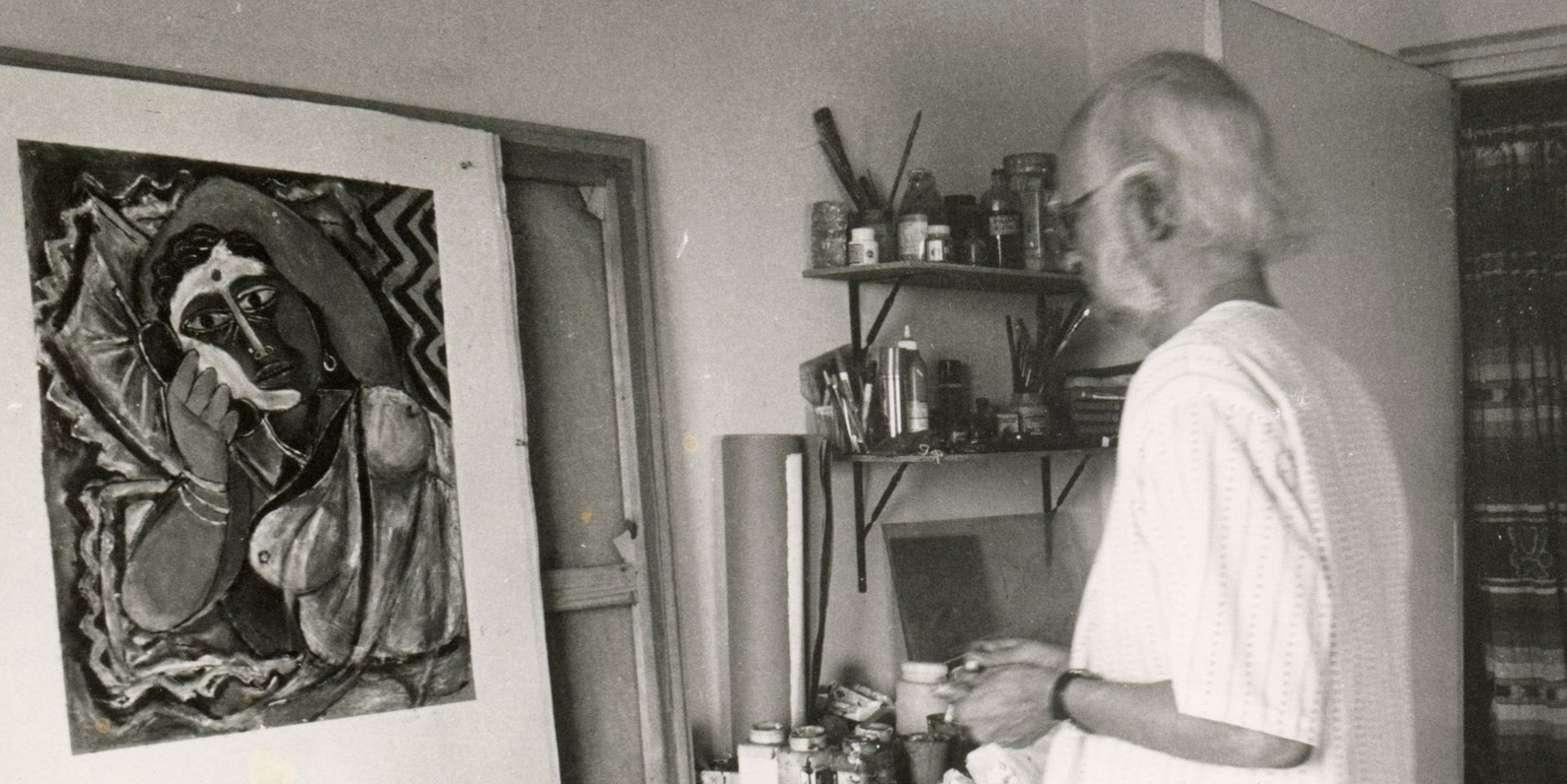

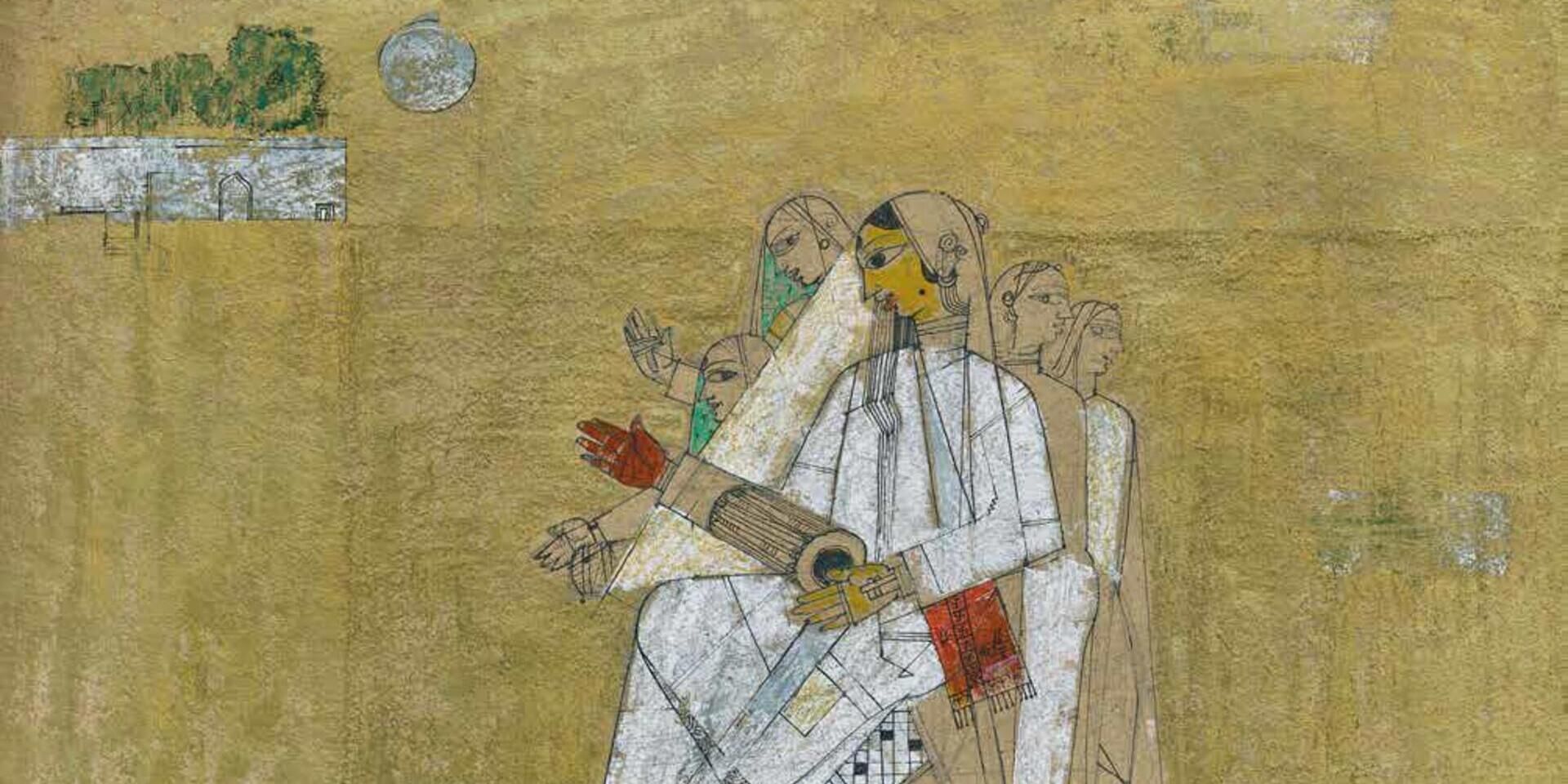

One of India’s nine national treasure artists, Nandalal Bose (1882—1966) forged a long and glittering career as the foremost artist-pedagogue bridging the late-colonial period and the first few decades after Indian independence.

During his tenure as a teacher in Rabindranath Tagore’s newly established university at Santiniketan’s Kala Bhavana, he influenced the work of several generations of modernists and supervised several exchange programmes with artists from East and South-east Asia. He maintained an active drawing practice throughout his life, with many small sketches done on postcards that he carried around with him as a sort of visual notebook. While many of his sketches offer delicate views of landscape, figures and animals, he also made albums of drawings that sought to reflect his documentary style. These were mostly architectural views, including temple sculptures, ornamental motifs and cave art—especially from Ajanta and Bagh. Fondly remembered by his students as ‘Master moshai’ (the revered teacher), he once said that ‘The purpose of all arts is the same. Poetry, sculpture, painting, dance, music and the rest want to capture the rhythm of delight inherent in all creation.’ In the intricate temple architectures of India, it is possible that he found a culmination of his view of an art that advocates this sense of rhythm and harmony between several artistic forms.

Konark is a popular pilgrimage town in the state of Odisha in Eastern India. It is best known for the thirteenth century Sun Temple that was built by Narasinghadeva I in black granite (leading some to refer to it as the ‘Black Pagoda’). It is a World Heritage Site that is now largely in ruins. The Archaeological Survey of India established a Sun Temple Museum that now houses many of the sculptures that were part of the temple complex. Art historian R. Siva Kumar wrote about this invaluable album for DAG’s publication, Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art, Edition II.

Nandalal Bose and his Konark temple album

R. Siva Kumar

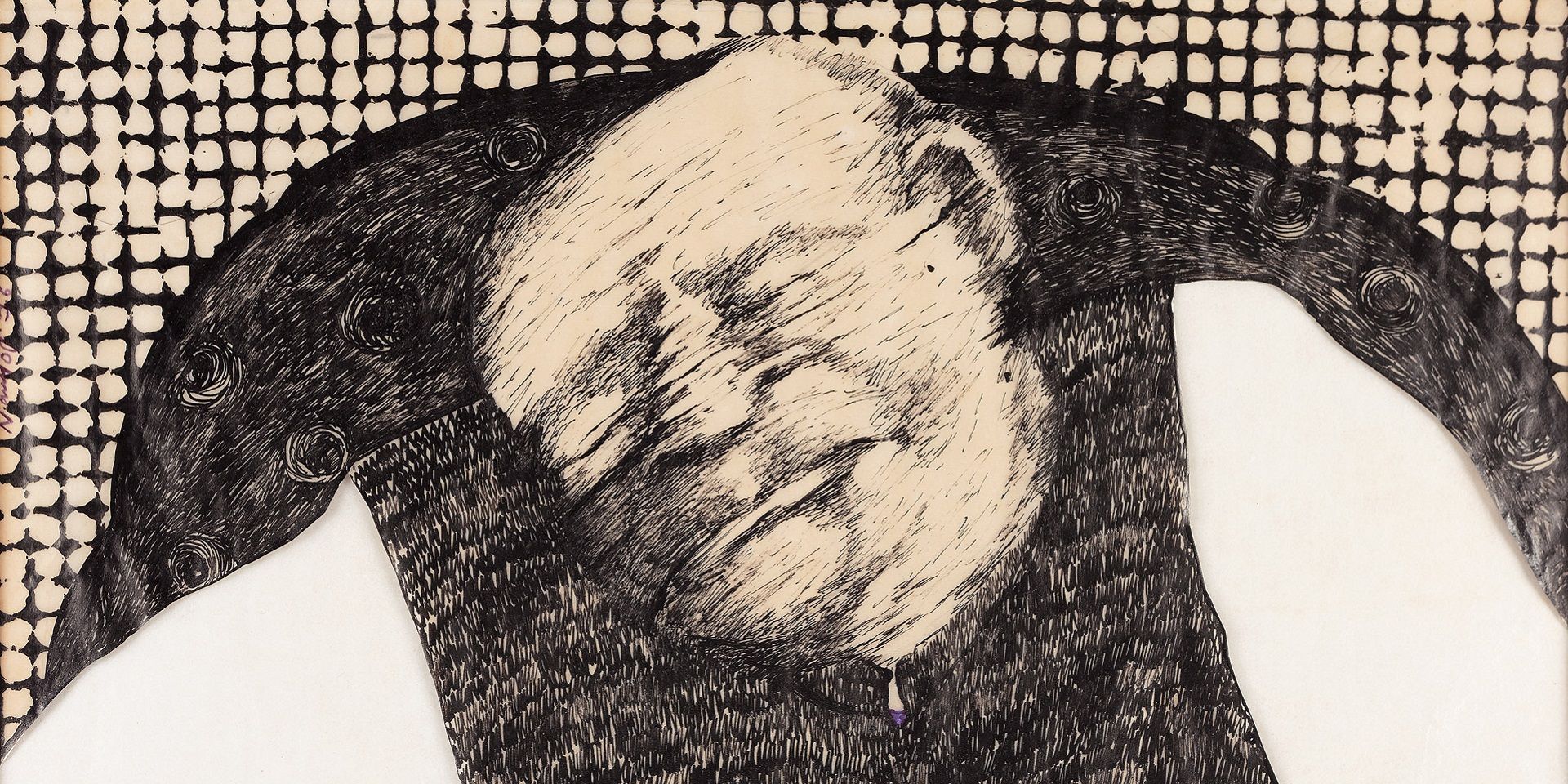

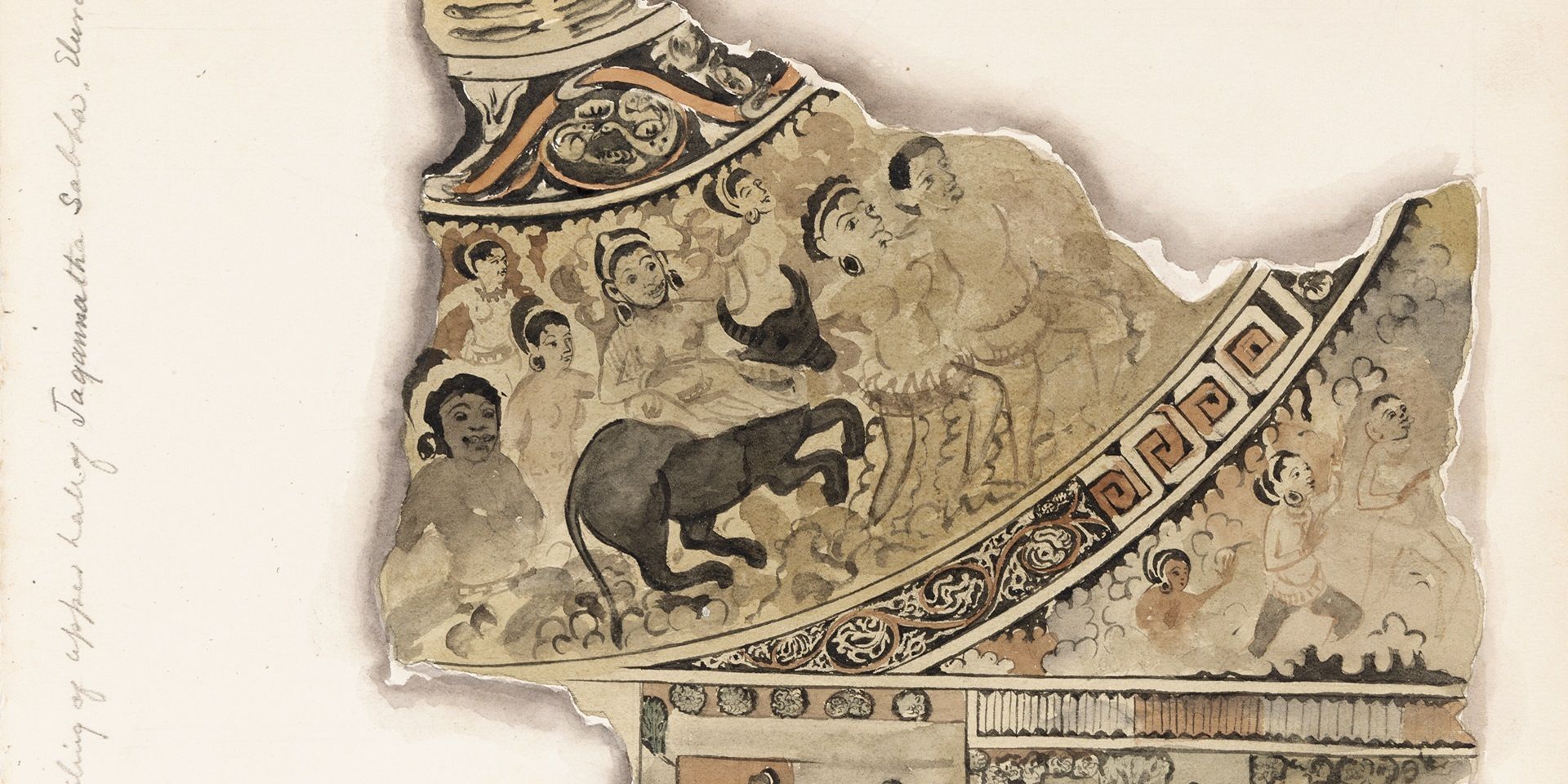

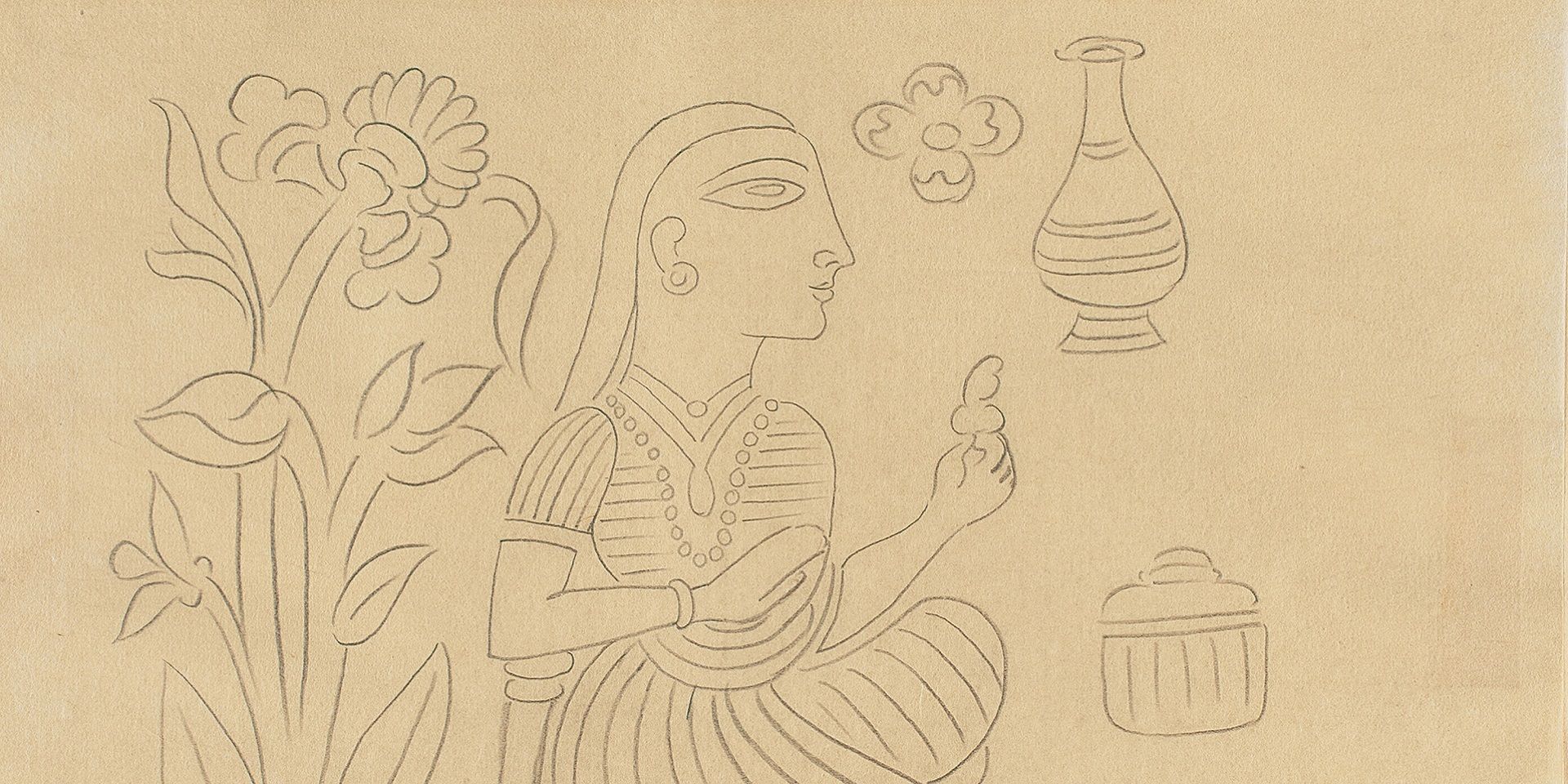

The album of Konark drawings by Nandalal Bose is an interesting document. Eroticism does not figure prominently in Bose’s work. Yet he is credited to have been one of the few who successfully resisted Mahatma Gandhi’s proposal to cover up the erotic sculptures on Indian temples. Here we have seventy-six drawings by him relating to Konark collected in an album. Of them, many are studies of explicitly erotic sculptures, one is a general view of the temple, others demonstrate his interest in design and ornamentation, and two are rubbings of ornamental details from metal objects. Clearly most of them were drawn on site, only a few, especially variations on a motif, could have been done in his studio. This and the stylistic variation of the drawings suggest that they were not done at the same time but collected together into an album later, a practice not uncommon with the artist.

Nandalal Bose visited Konark more than once. According to his biographer, Panchanan Mandal, he visited Konark twice—first with Arai Kempo and Suren Kar in 1917, and later with Benodebehari and Sutan Harahap in 1941. Some of the drawings in this album are dated December 25, 1931. Sutan Harahap, the Indonesian painter, was a student at Santiniketan in the late 1920s, so probably the second visit took place in 1931 and not in 1941. This does not necessarily foreclose the possibility of a third visit, but if it had indeed happened Harahap could not possibly have been a member of his team.

An inscription on the back of page one, in fact, suggests that the drawings belonged to three groups. While the drawings in the third group are numbered in sequence, those of the first and second are not sequentially numbered. Similarly, some in the first group are unnumbered and a few are missing from the second group. This suggests that the drawings were numbered before they were pasted in the album. Further, one drawing from the second group and three from the third group bear the same date (December 25, 1931), therefore, the groupings were also not entirely on the basis of date. Finally, it needs to be noted that the Surasundri sculpture of which there are several drawings in this album also figures in his 1917 painting Rain-swept Konark, and that a drawing of a mother and child was the probable source for a relief on the south side of Black House in Santiniketan done in 1936-37.

This Essay is a part of DAG Modern’s ‘Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art, Edition II’, published in 2017, which pairs famous art historians with iconic artworks from the DAG collection

related articles

Essays on Art

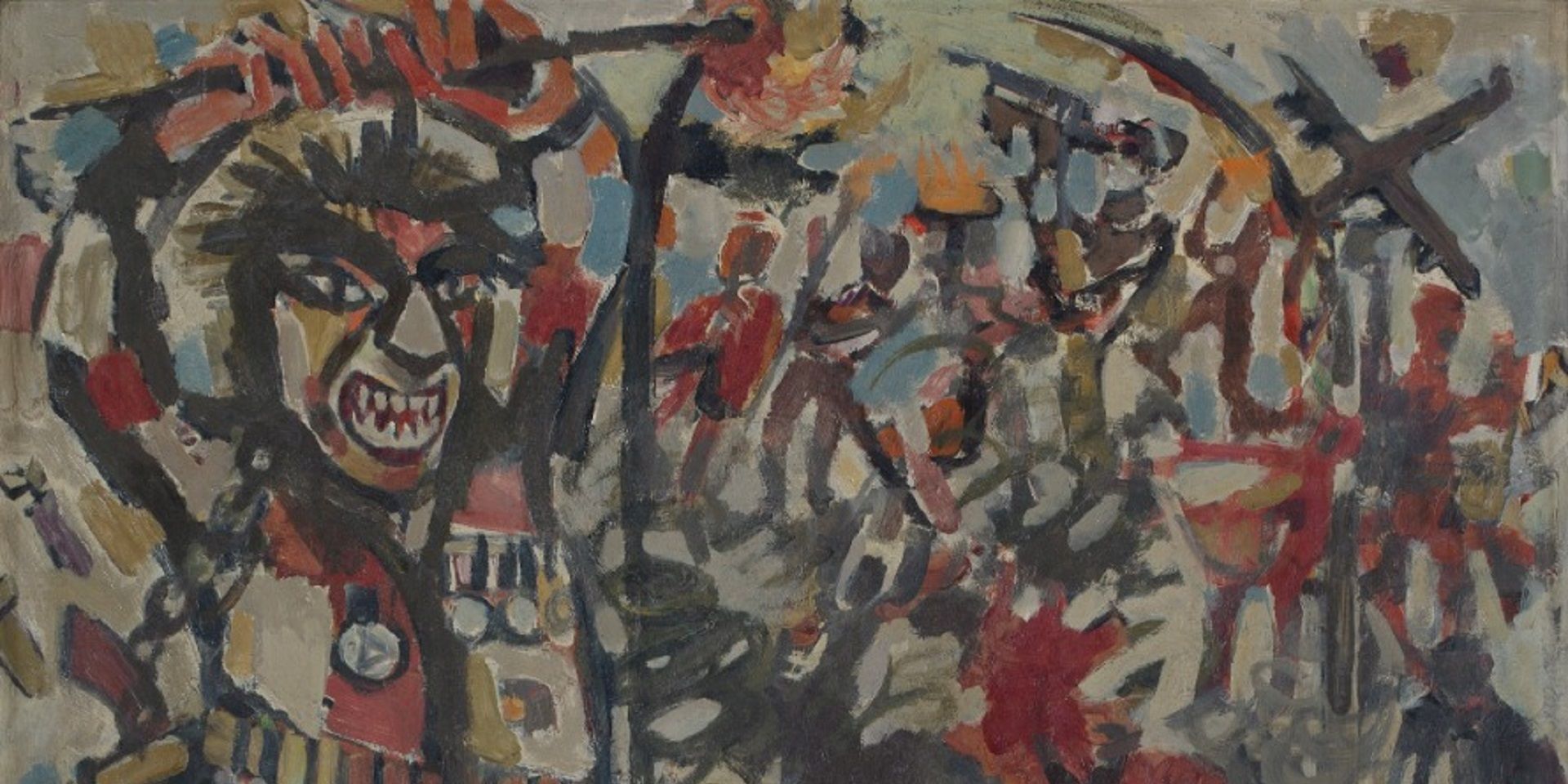

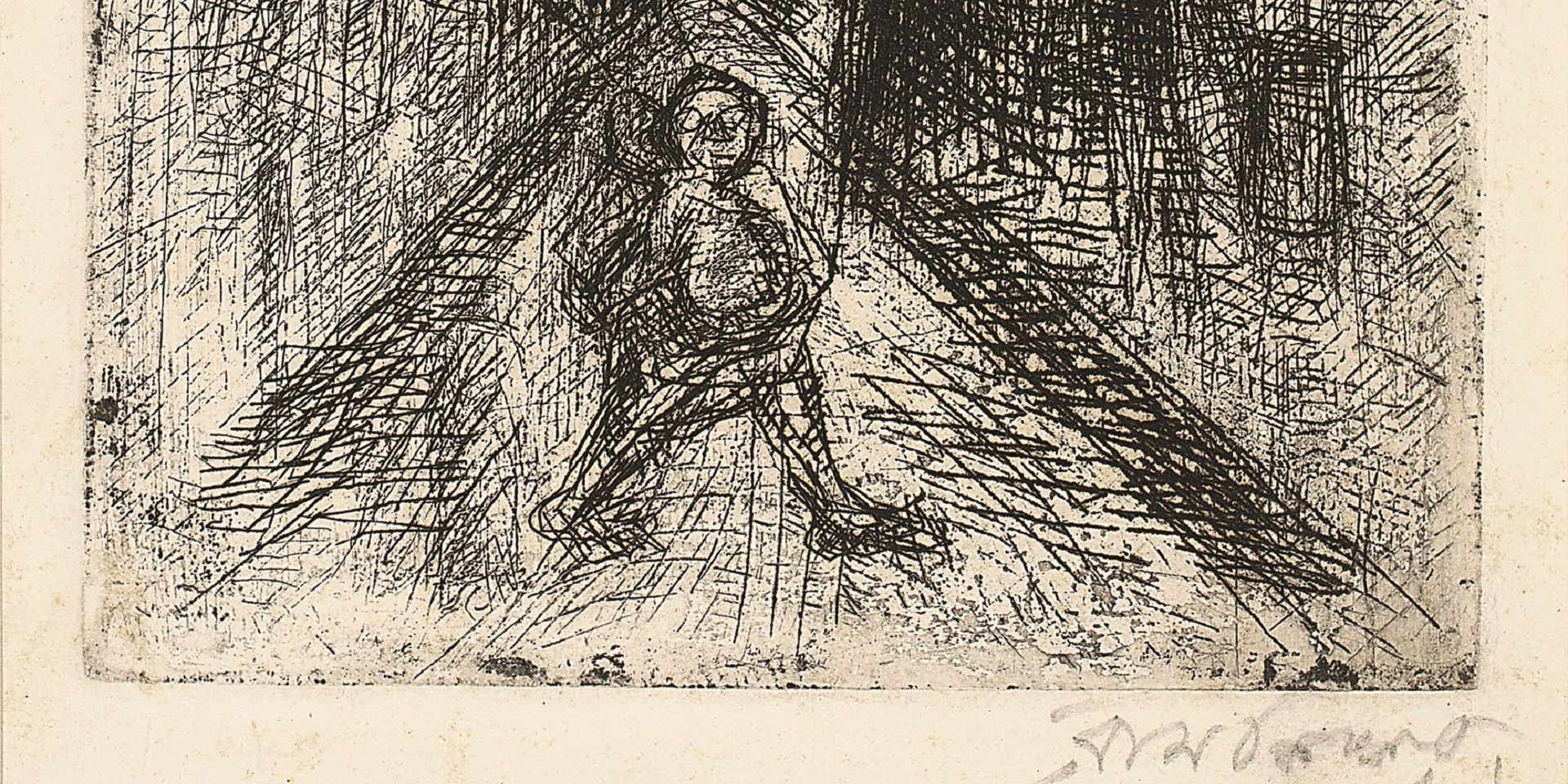

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

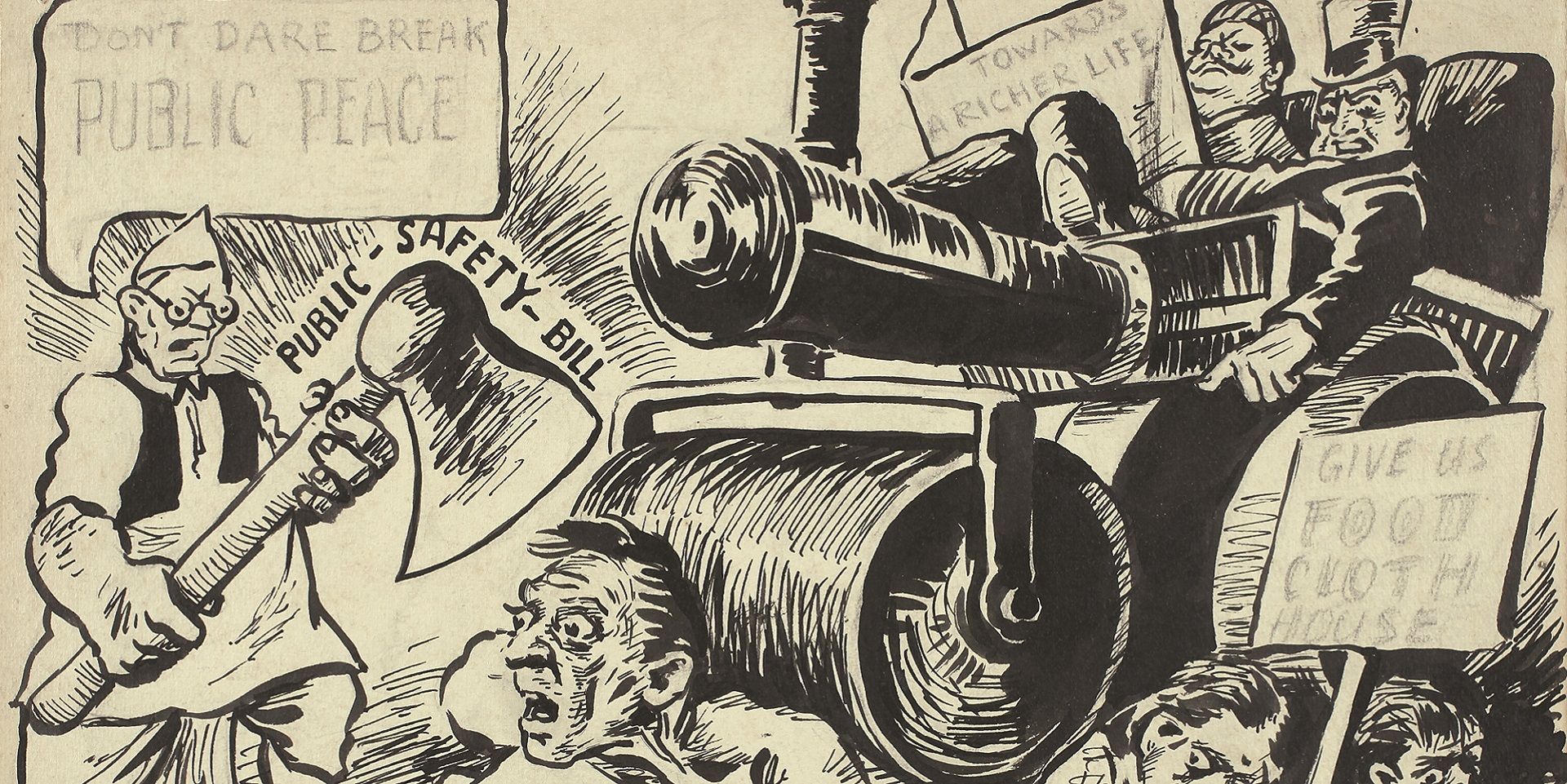

Essays on Art

To Hell with the State: Caricature in early (Post)colony

Sayandeb Chowdhury

June 01, 2023

Essays on Art

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Bhakti S. Hattarki

August 01, 2023

Archival Journeys

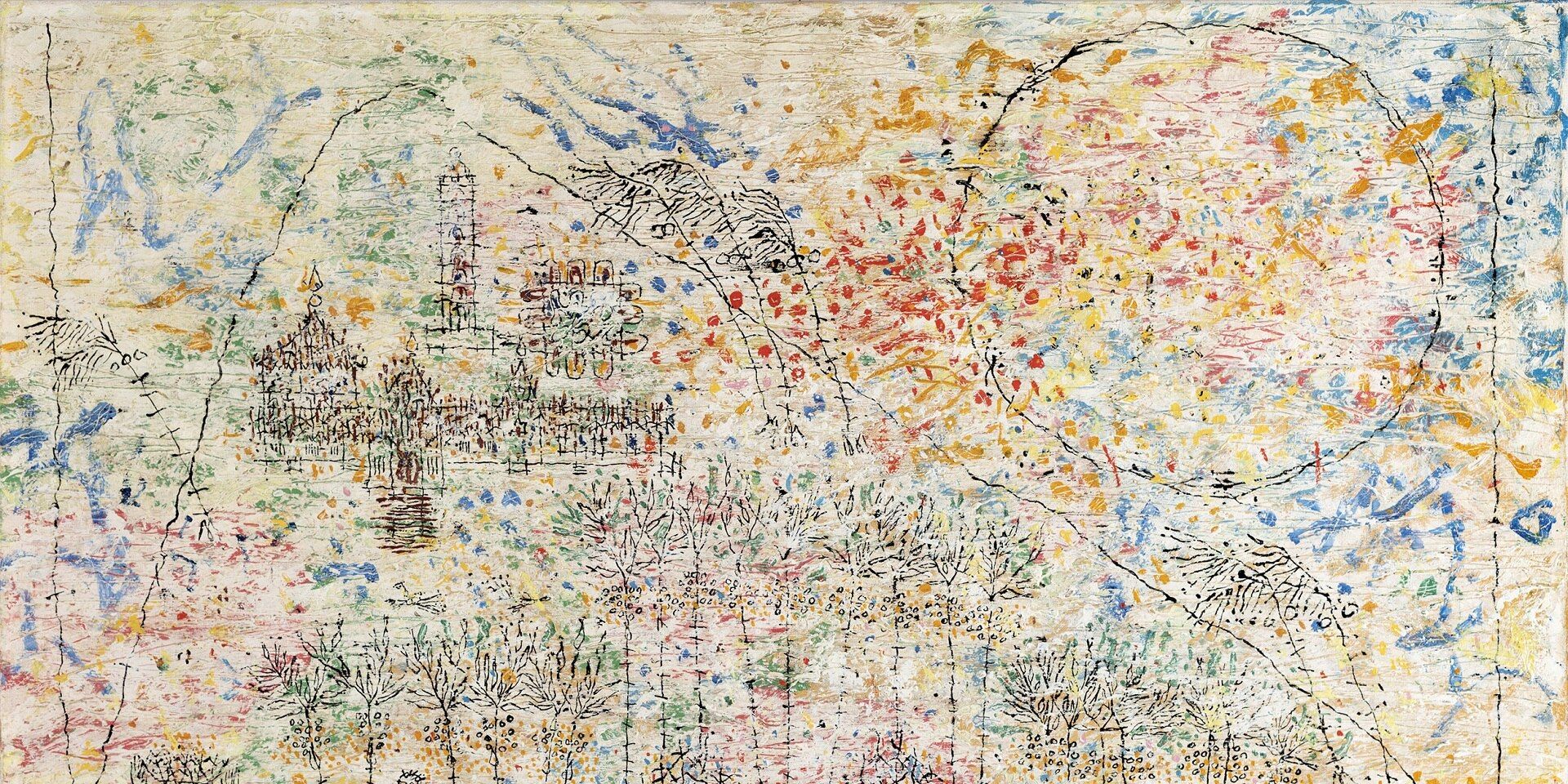

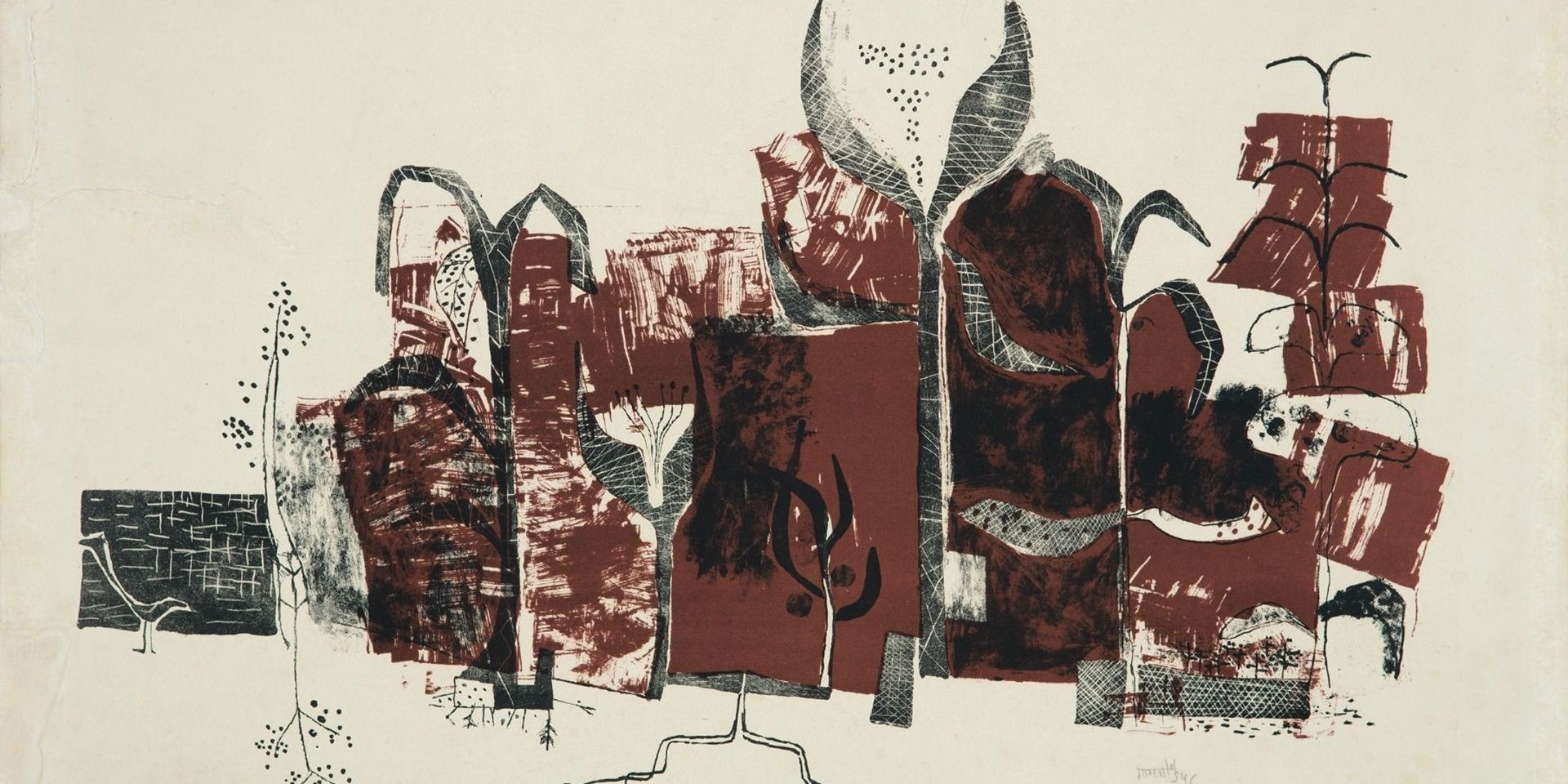

'The “livingness” of the past’: M. Reddeppa Naidu's mythologies

Shaon Basu

July 01, 2024

Travelling with Artists

Europe Before the War: Travelling with Ramendranath Chakravorty

Shreeja Sen

July 01, 2024

Essays on Art

On 'Not Looking Back': Samaresh Basu meets Ramkinkar Baij

Debotri Ghosh

August 01, 2024

Essays on Art

V. S. Gaitonde’s Century: Celebrating a Master Abstractionist

The Editorial Team

August 01, 2024

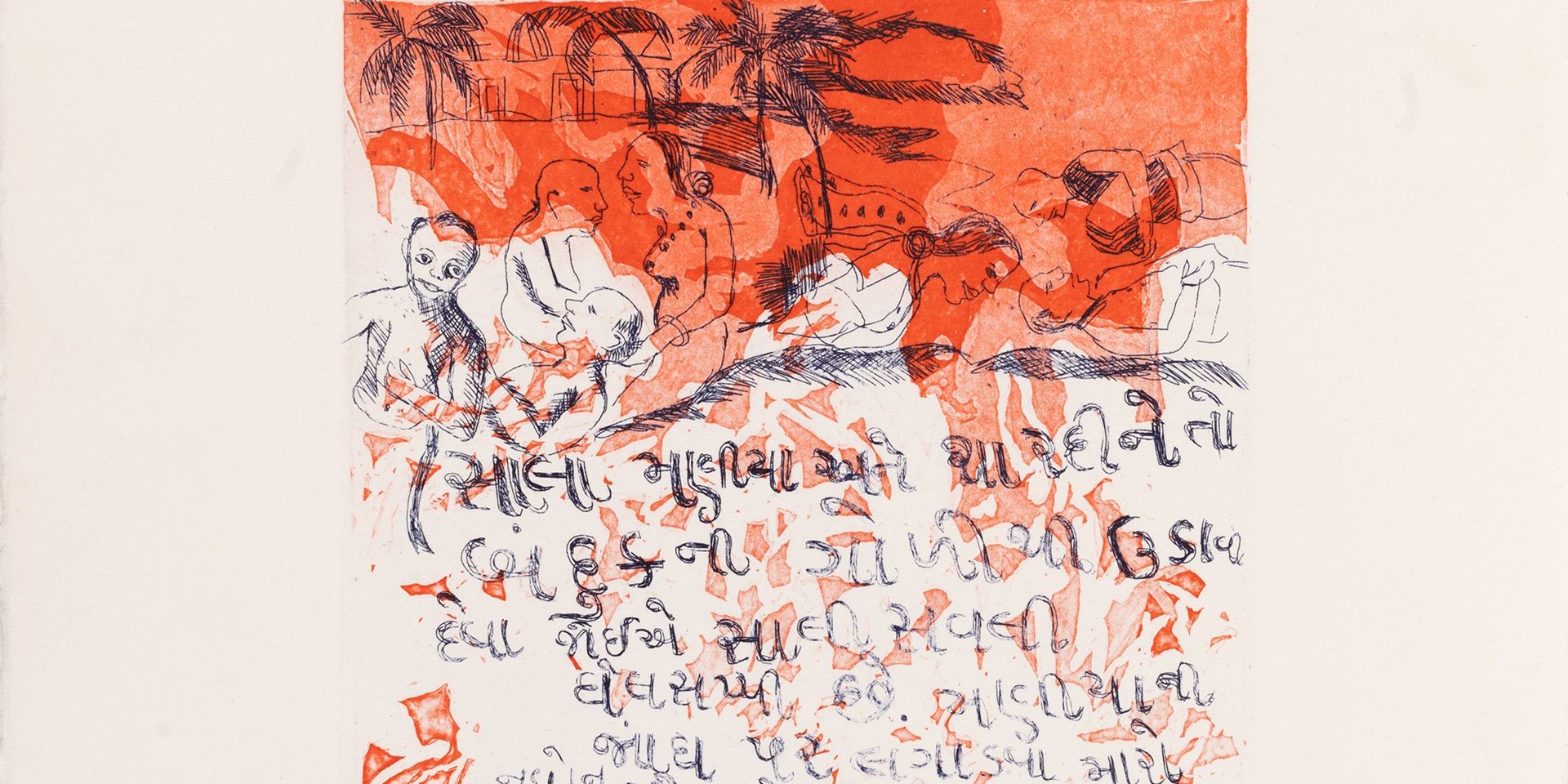

Erotics of the Foreign: On Bhupen Khakhar's 'Phoren Soap'

Bhakti S. Hattarki and Ankan Kazi

September 01, 2024

Essays on Art

Peripheries and the Center: Souza and Avinash Chandra in London

Shreeja Sen

December 01, 2024