Term of the Month: The verandah

Term of the Month: The verandah

Term of the Month: The verandah

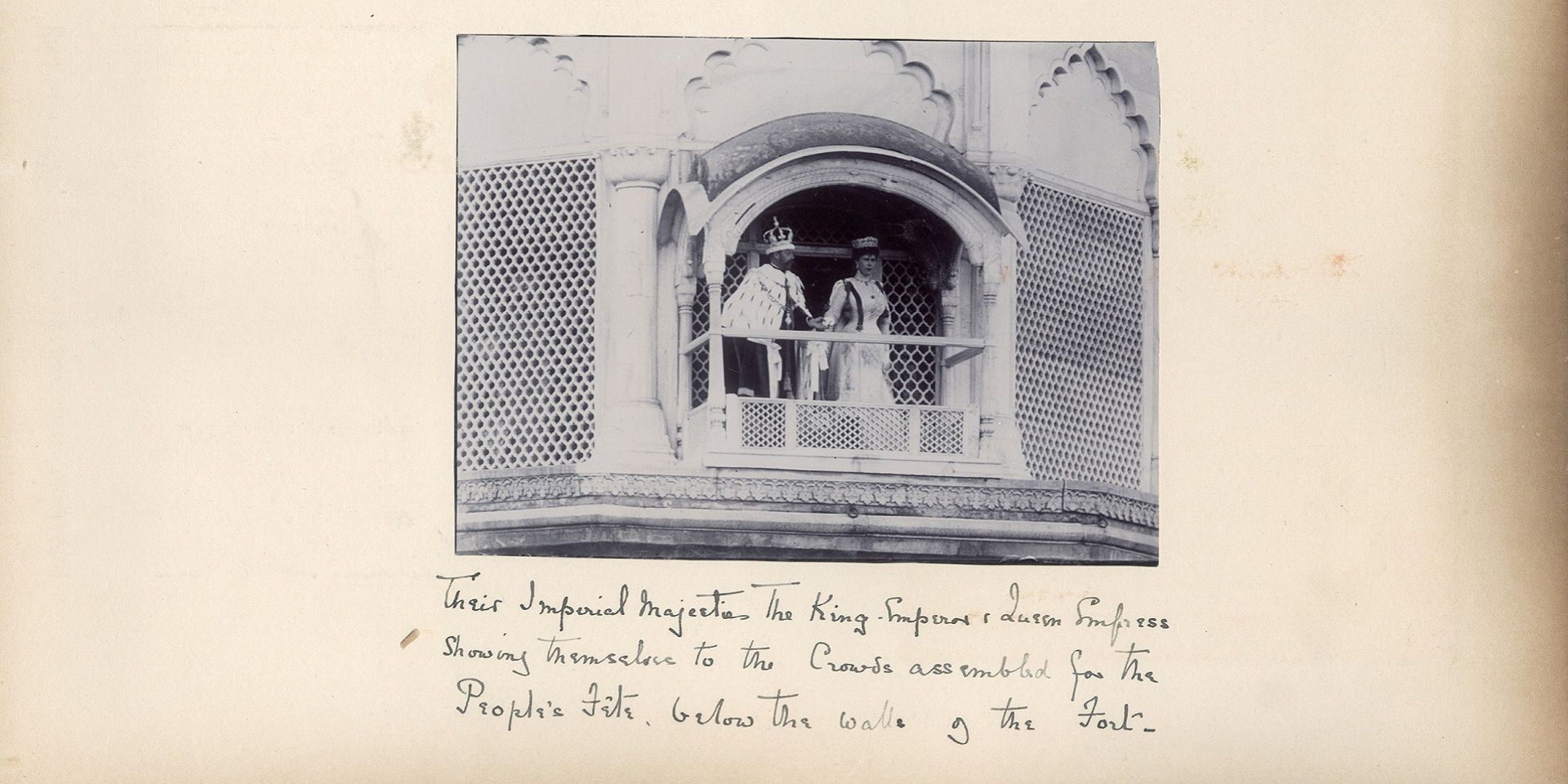

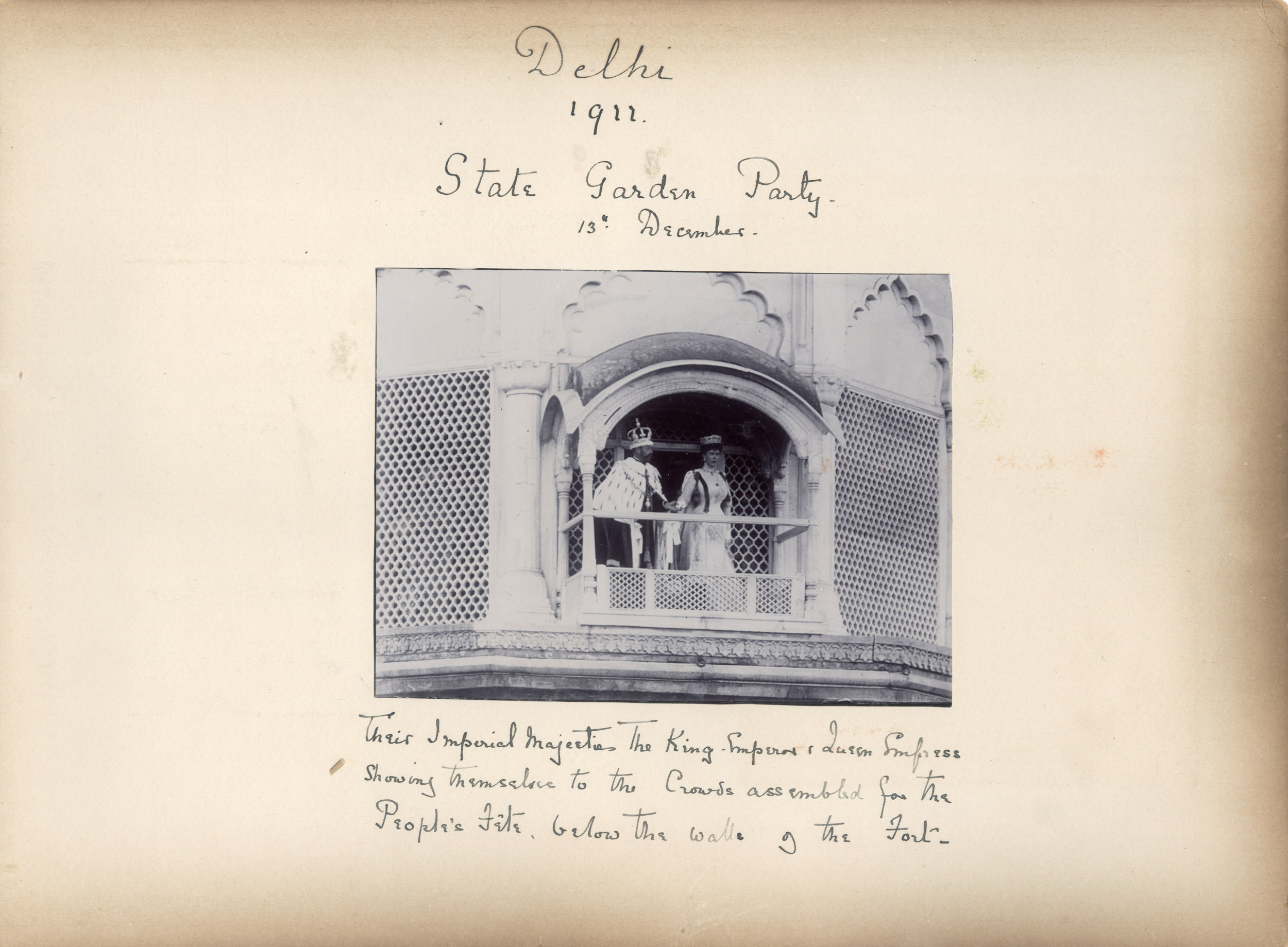

Unidentified photographer, Delhi 1911. State Garden Party. 13th December 1911, 1911, Silver gelatin print on paper mounted on card, 11.9 x 16.0 cm. Collection: DAG

How did the verandah become one of the most prominent architectural features in the global, especially tropical, south? And how did the colonial encounter transform it? We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art.

The verandah, an architectural feature with roots deeply embedded in diverse cultures and historical periods, has undergone a critical evolution over the centuries. From its humble beginnings in the East to its colonization-driven spread across the globe, the verandah has not merely provided shelter; it has shaped the way we inhabit and interact with our built environment.

Its early history is rooted in its functional necessity. In ancient civilizations, particularly in the Indian subcontinent, the oppressive heat prompted the creation of open, shaded spaces adjacent to homes. The earliest instances of verandahs in residential architecture can be traced back to ancient Vastu Shastra texts. These texts outline architectural plans and provide instructions for constructing houses, highlighting the prevalence of ‘Alinda’ (verandahs) as a common feature in domestic buildings. The verandah might possibly be derived from a similar Portuguese word, denoting a ‘railing, or balustrade’. These early verandahs, supported by columns or pillars, were practical responses to the climate, providing relief from the sun while allowing for natural ventilation. Their utility in tropical regions laid the groundwork for the verandah's enduring presence in architecture.

|

A colonial-style house, with a verandah. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

With the expansion of European colonial powers into tropical territories, the verandah underwent a significant transformation as well. Colonialists, seeking respite from unfamiliar climates, adopted and adapted the verandah into their architectural repertoire. The British in India, for instance, integrated verandahs into their residences, fusing practicality with a colonial aesthetic. This appropriation marked the beginning of the verandah's association with colonial architecture, an enduring legacy that persists in many post-colonial regions.

|

A balcony in Alcobaça, Bahia, Brazil. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

The verandah's evolution was not solely driven by climatic considerations; it also became a transitional space between the interior and the exterior. Beyond its functional role, it acted as a buffer against the elements, creating a threshold that mediated between the private and public spheres. This liminal quality endowed the verandah with cultural significance, influencing social dynamics and patterns of interaction. Most visibly, the British administration in India would seek to appropriate the Mughal tradition of the ‘Jharokha darkshan’ (The Ceremony of Sight), where the emperor would offer a view of himself on special occasions to gathered crowds through a balcony. King George V and Queen Mary, visiting India for the Delhi Durbar of 1911, revived this historic ceremony. As they entered through the Jharokha, accompanied by their Indian pages, they gracefully made their way to a modest balcony on the terrace adjacent to the Rang Mahal, where their thrones were positioned. Subsequently, the pages took their seats around the thrones, ensuring that the assembled crowd of onlookers and palace guests had an unhindered view of the Emperor and Empress.

Unidentified photographer, Delhi 1911. State Garden Party. 13th December 1911, 1911, Silver gelatin print on paper mounted on card, 11.9 x 16.0 cm. Collection: DAG

|

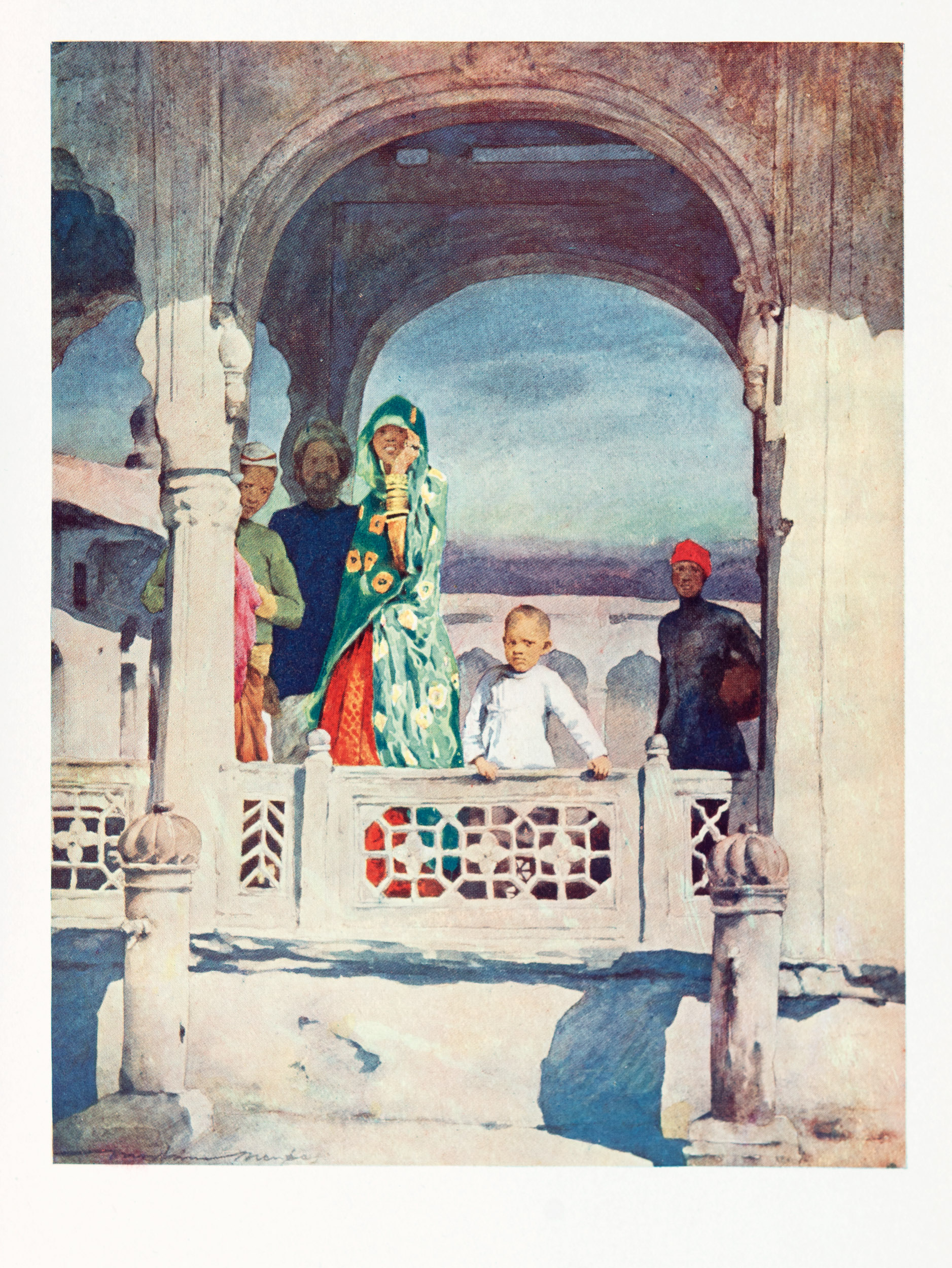

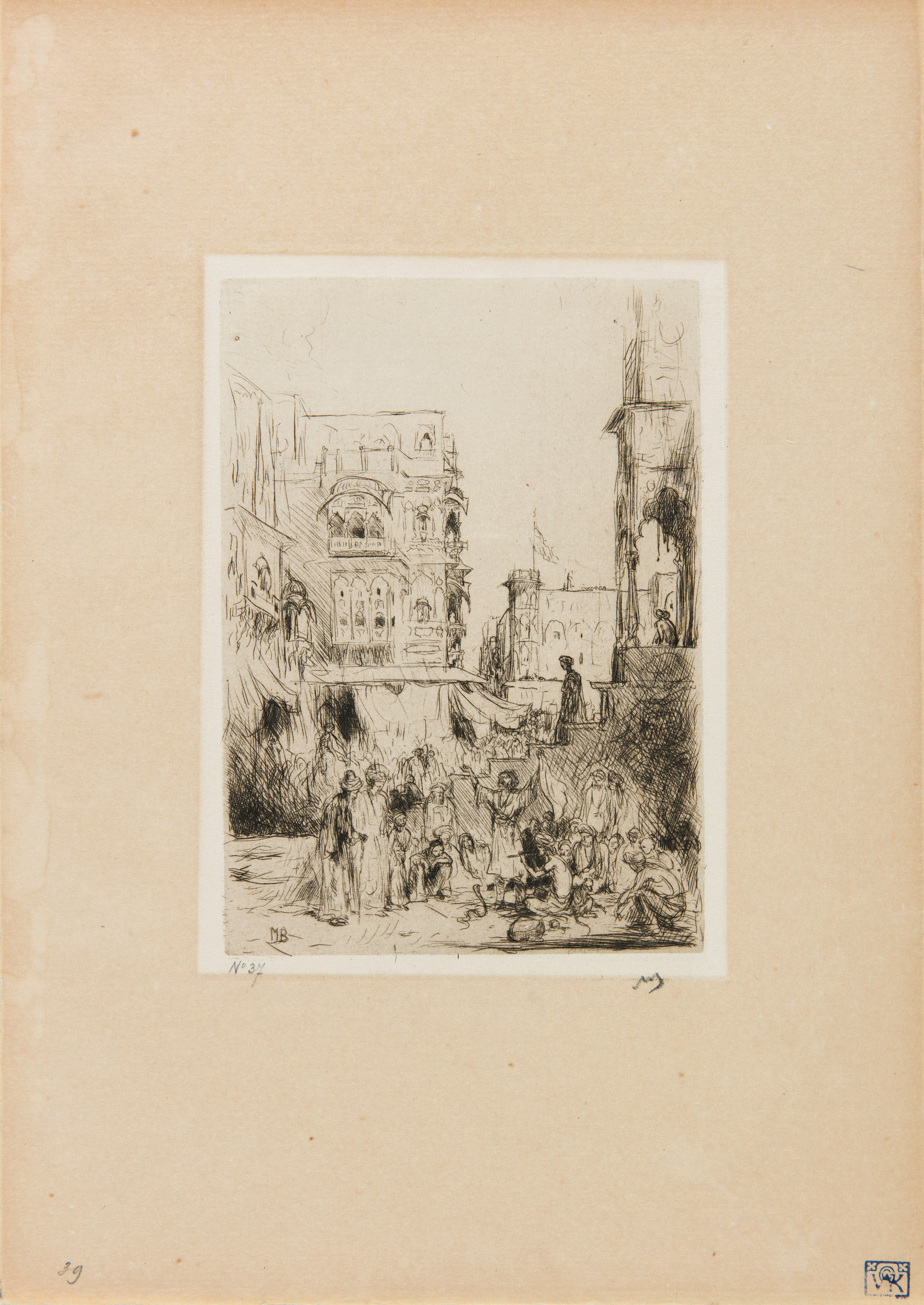

Mortimer Menpes (illustrator), Durbar, 1903, Printed book with 100 coloured illustrations. Collection: DAG |

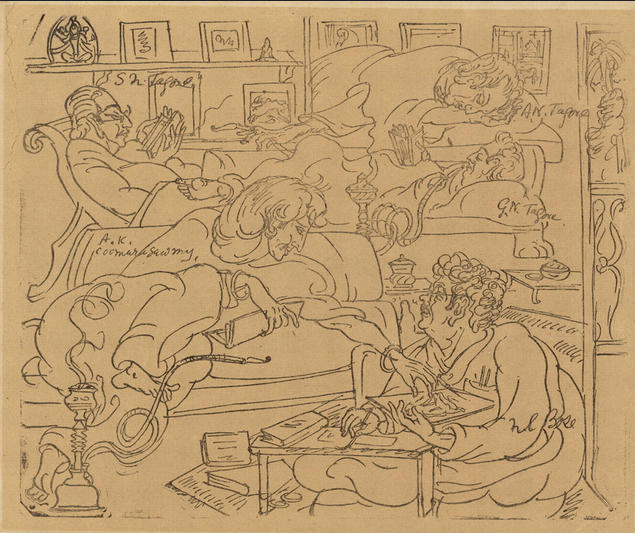

Arguably, the verandah became a significant laboratory for Indian modern art as well, as artists like Abanindranath Tagore and his elder brother, Gaganendranath Tagore, frequently painted in the verandah of their house in north Calcutta’s Jorasanko. Fondly remembered as ‘Dakshiner Barandah’ (The Southern Verandah), the space was open to scores of students who came to learn from Abanindranath, and even included his own grandson, Mohanlal Gangopadhyay, who later wrote an eponymous memoir set in that famous verandah-studio. While discussing Nandalal Bose’s famous sketch of the artists’ studio at Jorasanko, Tapati Guha-Thakurta writes, ‘In this sketch by Nandalal Bose, the distinction between the two locations of art activities at Jorasanko—the Dakshiner Barandah and Bichitra Club—gets blurred and the two sites merge into each other, as would have happened at that time. In its more informal gatherings, as in the one depicted in this sketch, the club, we are told, would often convene in the southern verandah, while the regular painting classes and the evening plays, with theatre sets created by Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, would be held in the larger hall in the Number 6 premises (of Jorasanko).’

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (The Artists’ Studio, Jorasanko), Ink on paper, c. 1914-16, 20.3 x 22.9 cm. Collection: DAG

Thus, as the verandah gained prominence, it acquired symbolic value. It became a space for hospitality, where families received guests and engaged in social rituals. The verandah, with its openness and connection to nature, became a site for relaxation and contemplation. In many cultures, it became an integral part of daily life, influencing social hierarchies and reinforcing community bonds.

Sushil Chandra Sen, At the Balcony, 1947, Oil on canvas, 47.0 x 45.7 cm. Collection: DAG

While the colonial era significantly shaped the verandah's identity, it also set the stage for its adaptation across different cultures. The architectural form spread globally, with variations emerging in response to local climates and traditions. In the United States, for instance, the Southern porch shares similarities with the verandah, adapting to the regional climate while maintaining its social functions.

In the modern era, as architectural styles have evolved, the verandah has not faded into obsolescence. While technological advancements like air conditioning have reduced its functional necessity, architects continue to reinterpret and integrate the verandah into contemporary designs. The verandah has become a design element that bridges tradition with modern aesthetics, offering a nod to history while responding to the changing needs of the present.

The artistic history of the verandah reveals its multifaceted evolution, from a pragmatic response to climate to a symbol of cultural identity and social interaction. As an architectural feature, the verandah has traversed continents and centuries, leaving an indelible mark on the built environment. Its history invites us to reflect not only on its aesthetic appeal but also on the complex interplay between function, culture, and the ever-changing dynamics of human habitation.

|

Marius Bauer, Untitled. Collection: DAG |