Term of the Month: En Plein Air

Term of the Month: En Plein Air

Term of the Month: En Plein Air

Gopal Ghose, Untitled (detail), pastel on paper. Collection: DAG

One of the methods adapted for landscape studies by artists, en plein air became a site of experimentation for painters across the world. We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art.

En Plein Air painting refers to painting landscapes out in the open, in an attempt to capture environmental transformations with close observations rather than painting from memory within the studios.

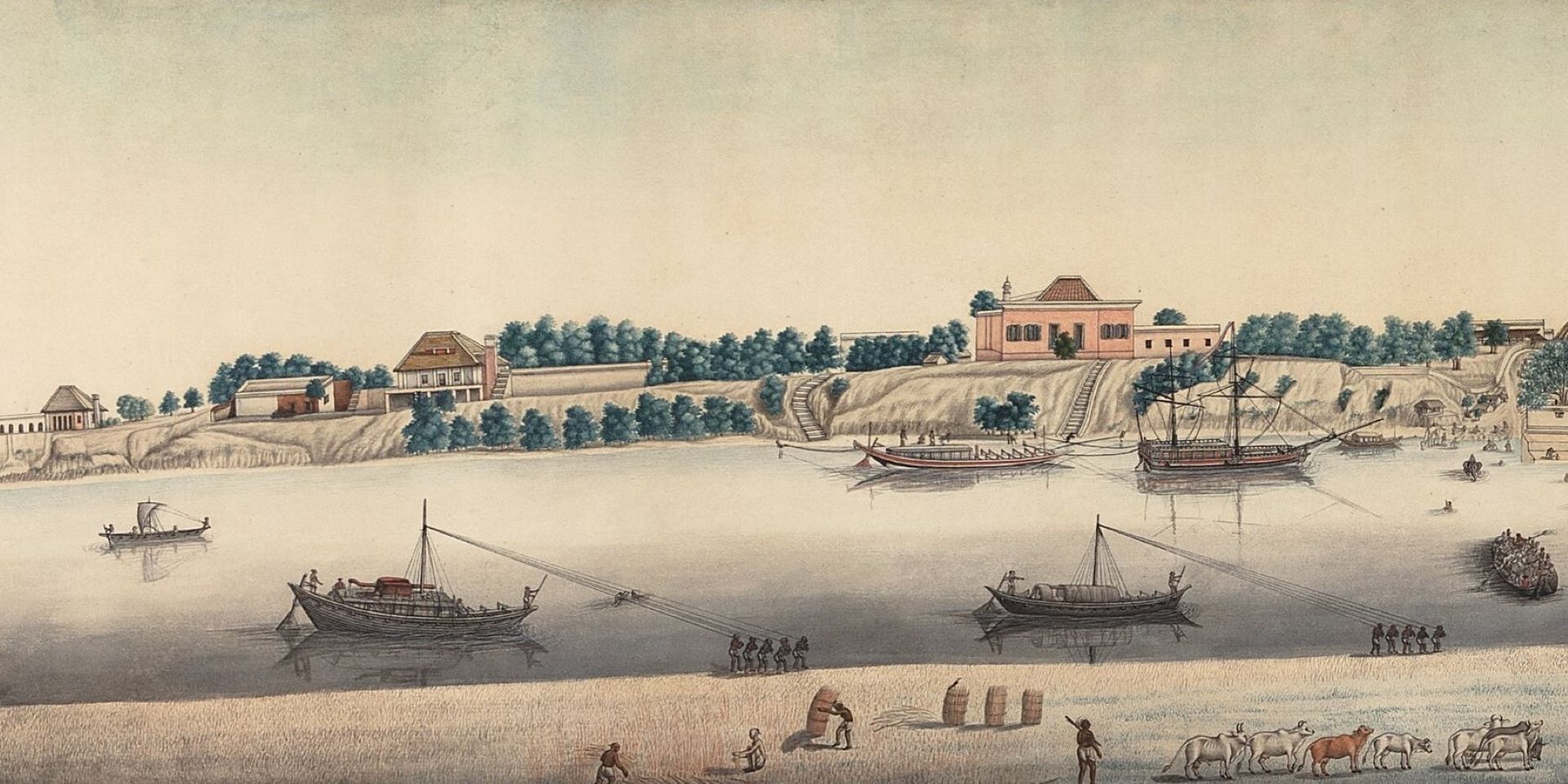

Thomas Daniell and William Daniell, View on the Chitpore Road, Calcutta, Handtinted engraving on paper. Collection: DAG

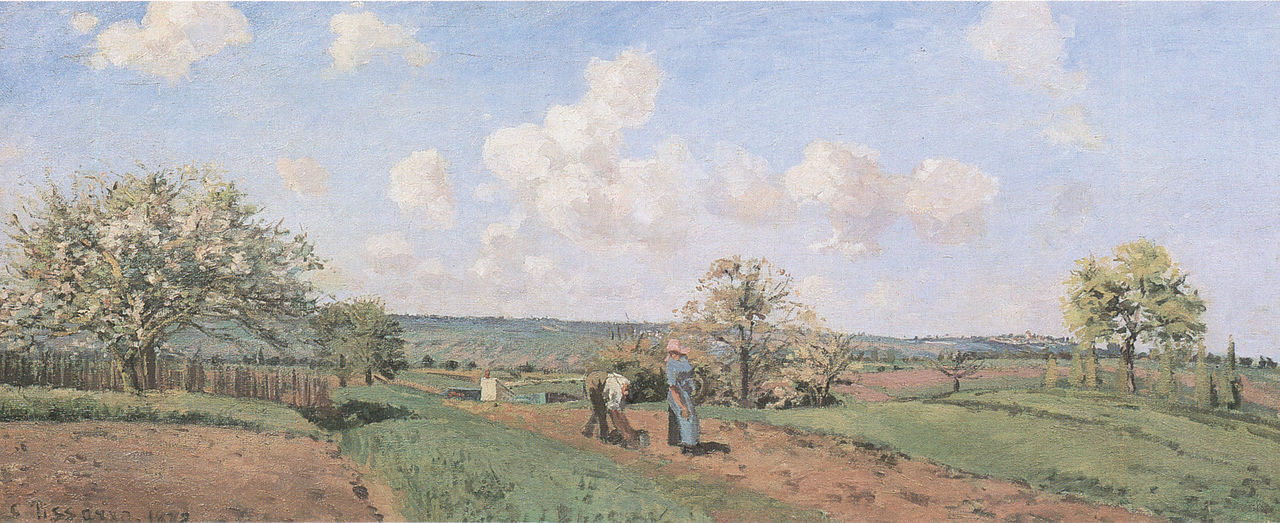

From sixteenth century onwards, Western Art had characterised different genres into a hierarchical order, with History Painting taking the highest position in the hierarchy, followed by portraiture, landscape painting, still life and, lastly, the painting of mundane everyday activities. By the early seventeenth century plein-air painting was being extensively practiced by several artists and by 1850 landscape painting became the most popular genre in the Paris Salon and within communities of collectors. Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes was one of the most important landscapists who as a professor of perspective at the Académie Royale in Paris facilitated a pedagogical assimilation of the plein air method for painting landscapes. According to his theory it was beneficial for younger artists to train with oil paint outdoors to be able to understand the transience of natural patterns, their movements, and the ever-changing light, to train the hand and eye in order to truly emulate nature. Later, this method became a working reality for nineteenth century artists like the Impressionist painter Camille Pissaro, who was influenced by Valenciennes’ treatise on landscape painting, and the Post–Impressionist painter Paul Cezanne.

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, À la villa Farnèse: les deux peupliers (At the Villa Farnese: the two poplars), 25.3 x 37.8 cm. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Camille Pisarro, Le Printemps (Spring), oil on canvas, 55 x 130 cm., 1872. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

It became necessary for one to be able to access difficult terrains and navigate different weather conditions which made the art of landscape painting in general a male dominated phenomenon. Anthea Callen writes about the masculine and, adventurous Realist painter Gustave Courbet: ‘.. from 1855 the swaggering masculinity that Courbet affected and the technical ‘virility’ of his painting stamped this persona onto landscape (qua ‘feminine’ nature to be mastered) in ways that only colour, with its feminine associations, could hope to modify with the rise of Impressionism.’

Berthe Morissot, In the wheat, oil on canvas, 47 x 69 cm., 1875. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Berthe Morisot is supposedly the only known female artist who practiced plein- air painting in the early nineteenth century. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, landscape painting was becoming a dependable vocation and the status of an artist as a craftsman was eventually transformed into that of an individual ‘genius’.

|

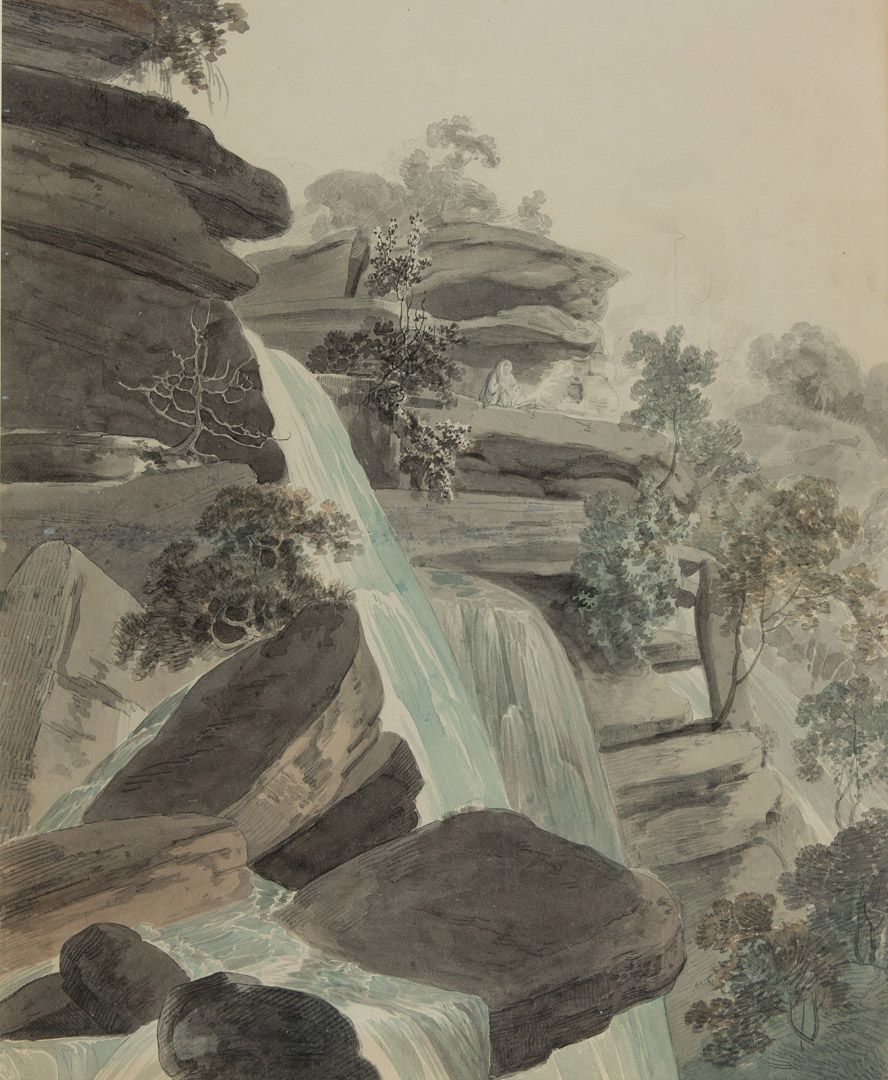

Thomas Daniell, Untitled, Watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper pasted on paper, 63.5 x 52.1 cm. Collection: DAG |

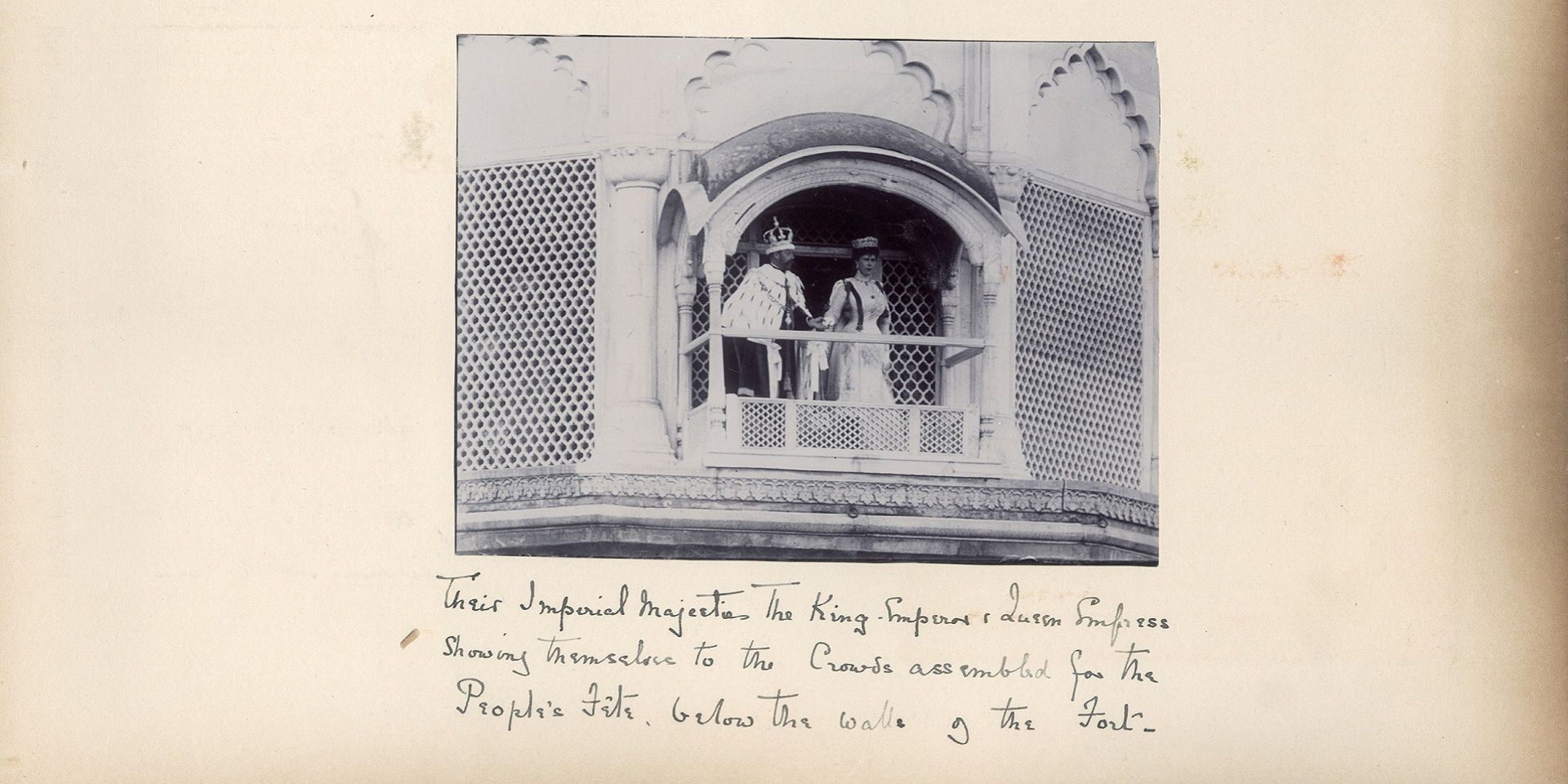

With the advent of the imperial age, landscape painting took on the additional role of documenting colonised lands and their people. It became paramount to record and publish images of colonial settlements and the exotic ‘Oriental’ landscape to legitimize the British expansionist rule through the eighteenth and nineteenth century. During the second half of eighteenth century, the function of landscape painting shifted, as the Battle of Plassey, fought in 1757, led to a series of wars and annexations giving the British East India Company considerable power over large territories throughout South Asia. A number of British officials and Indian artisans were trained as draughtsmen and were commissioned with the task of surveying these new territories.

William Hodges, A View of a Hill Village in the District of Baugelepoor, Soft-ground etching and aquatint on paper, 34.3 x 48.3 cm., 1787. Collection: DAG

Apart from the official commissions, the British East India Company also enabled and encouraged European artists to freely travel their territory. Among them were Thomas and William Daniell, the adventurous travelers who navigated treacherous routes to document British architecture and dilapidated ruins of Indian monuments devoid of human presence. William Hodges, another noteworthy British landscapist, was criticized for his highly romanticized and idealized depictions, especially by the Daniells who preferred a more observational approach.

S. L. Haldankar, Untitled, Watercolour on handmade paper, 20.8 x 28.4 cm., 1930-32. Collection: DAG

|

N. R. Sardesai, Entrance to Chaitya Hall, Karle, Watercolour on paper, 50.8 x 34.3 cm., c. 1930. Collection: DAG |

Meanwhile, art schools became important institutions for public instruction as it became important to transform and counsel ‘native’ taste. Landscape painting was not taught as a subject but was practiced by students during tours of archeological sites. Similar teaching methods were employed at Calcutta’s Mechanics Institution, established in 1839, which came to be known as the Government College of Art and Craft. Renowned artists from J. J. School of Art like M. K. Parandekar, M. V. Dhurandhar, M. R. Achrekar and S. L. Haldankar were among the earliest Indian artists to make plein air paintings of archeological monuments and vistas, which were popular in Bombay and its surrounding areas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Abalal Rahiman was appointed as the court painter of the Kolhapur Royal family and he travelled extensively with his patron to paint landscapes on spot; he experimented with the changing light through the day and preferred watercolour over other mediums. Later on, Gopal Ghose, who taught at the other academic art institution, the Government College of Art and Craft in Calcutta (now Kolkata), and known for his expressionistic renderings of landscape, would also travel rural India (especially Bengal) on his bicycle which acted as his studio on wheels. He painted and sketched a number of plein-air landscapes along with other subjects like wildflowers and birds.

Abalal Rahiman, The Rankala , Oil on oil paper, 25.9 x 37.3 cm., 1923. Collection: DAG

Artists like Kisory Roy and Jamini Prakash Gangooly, on the other hand, continued painting plein- air landscapes in the academic style. Shukla Sawant writes, ‘Studiously apolitical, Gangooly painted landscapes like an aristocrat with emphasis on furrowed productive land or recuperative scenes of nature’s bountifulness. Revealing no anxieties of the tumultuous happenings of the age, he immersed himself in painting…’. Artists like Raja Varma, Abalal Rahiman, J. P. Gangooly and Lucy Sultan Ahmed were known for their landscape paintings. Most of them regularly exhibited at Bombay Art Society where the audience started noticing a developing interest in nature and architecture due to which The Times of India tagged them as the ‘Open Air School’ of painters. They are believed to have painted en plein air as a part of their attempt to reclaim India’s glorious past.

H. A. Gade, Untitled, Oil on canvas, 61.0 x 81.3 cm., 1973. Collection: DAG

The intuitive act of painting what one can see, or an effort to render mimesis through quick observations enabled some modernist artists to eventually move away from the strictly academic style towards developing more personalized idioms for rendering open air studies.

Gopal Ghose, Untitled , pastel on paper. Collection: DAG