Term of the Month: Aquatint

Term of the Month: Aquatint

Term of the Month: Aquatint

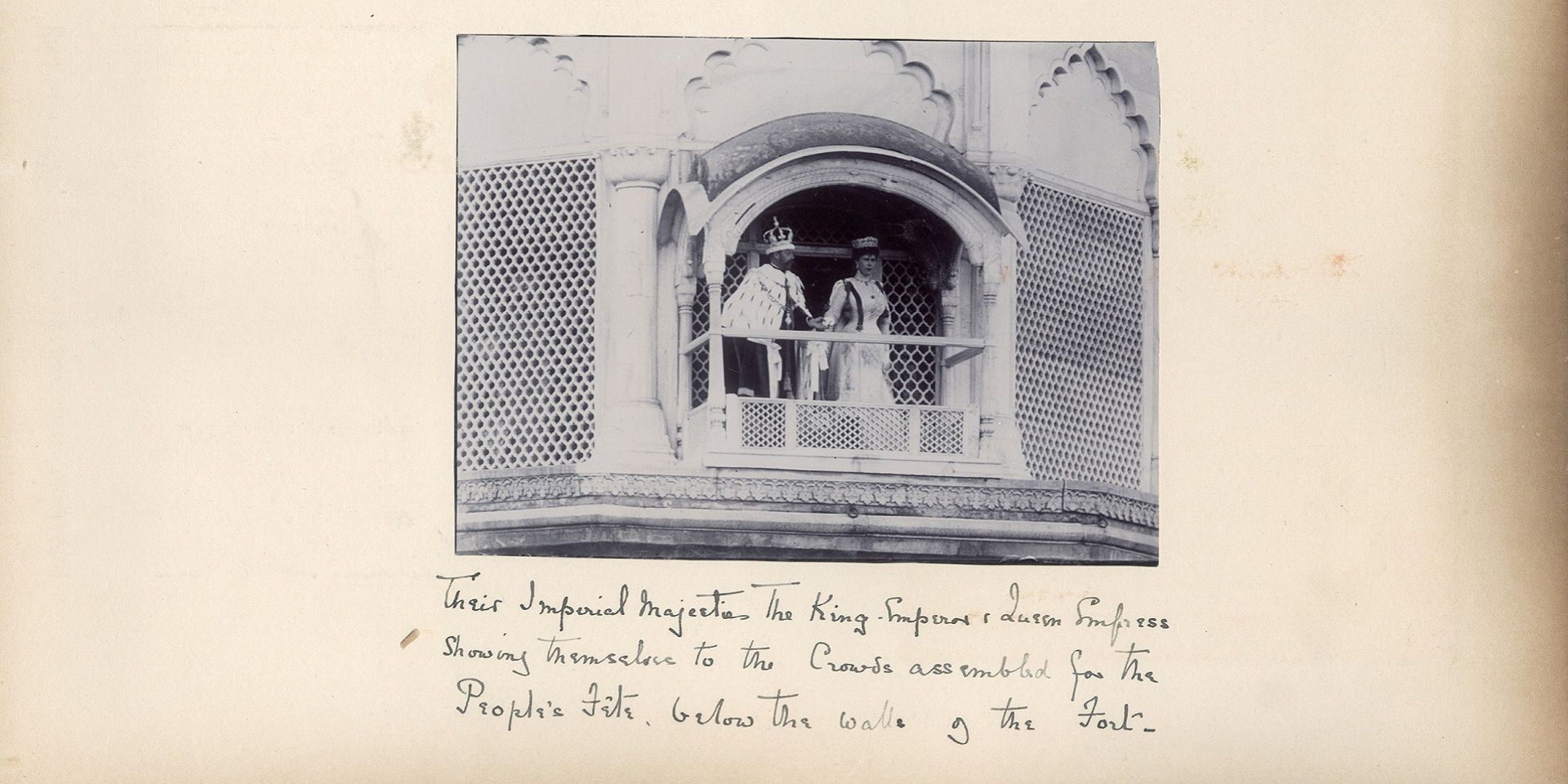

William Hodges, A View of a Hill Village in the District of Baugelepoor, 1787, Soft-ground etching and aquatint on paper, 34.3 x 48.3 cm. Collection: DAG

How does the aquatint process work and why was it adopted by so many travelling artists during the colonial period? Did modern artists attempt to grapple with this legacy? We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art.

Intaglio refers to family of printmaking techniques in which an image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area is made to hold the ink—with the impression eventually being transferred onto a paper surface to make a print. This technique is the opposite of relief printing, where the ink is applied to the raised areas of the printing plate. Intaglio printing methods include engraving, etching, drypoint, aquatint, and mezzotint.

Aquatint allows artists to create tonal effects similar to watercolour or wash drawings. It is especially useful for capturing subtle gradations of tone and texture, making it a popular choice among travelling artists like William Hodges (1744-1797) and the Daniells—Thomas (1749-1840) and his nephew William (1769-1837)—who were known for their intricate landscape and marine artworks. In the case of the latter pair of artists, their techniques improved over the course of their career, achieving the status of masterpieces with the publication of Oriental Scenery (1795-1808).

Thomas Daniell, Hindoo Temples at Agouree, on the River Soane, Bahar, 1796, Hand-tinted aquatint on paper, 18.0 x 23.7 in. Collection: DAG

The aquatint process goes through the following stages:

Preparing the Plate:

Artists start with a metal plate, traditionally copper, which is coated with a fine powder of resin. The plate is then heated to adhere the resin grains securely.

Creating Tonal Values: :

The artist uses a variety of tools, such as brushes, scrapers, or burnishers, to selectively remove parts of the resin from the plate. The areas where the resin is removed will later hold the ink and appear darker in the final print. Artists manipulate the grain density to achieve different tonal values.

Etching the Plate:

The prepared plate is immersed in an acid bath. The acid bites into the exposed areas of the plate (where resin was removed), creating recessed grooves. The longer the plate is left in the acid, the deeper the grooves, resulting in darker tones upon printing.

Inking the Plate:

Ink is applied to the entire plate, covering both the surface and the etched grooves. The surface ink is wiped away, leaving ink only in the etched areas, thanks to the aquatint's granulated surface which holds ink particles effectively.

Printing the Image:

Dampened paper is placed on the inked plate, and the two are run through a printing press under high pressure. The press forces the paper into the etched lines, picking up the ink and creating the final print.

Variations and Additional Techniques:

Artists can use multiple aquatint plates with different tonal values to create a range of colours and effects in a single print. They can also combine aquatint with other intaglio techniques like etching and engraving for intricate and detailed artworks.

Zinc plate with powder resin. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Hodges utilized the aquatint process to reproduce his intricate and detailed watercolour sketches of the landscapes and cultures he encountered during his travels. One of his most notable journeys was with Captain James Cook on his second voyage to the Pacific (1772-1775). During this expedition, Hodges created numerous sketches and drawings of the landscapes, flora, fauna, and indigenous peoples of places such as Tahiti, New Zealand, and Australia.

By employing aquatint, Hodges was able to translate the softness and luminosity of his watercolour originals into printed reproductions. This technique allowed him to capture the subtleties of light and shade, as well as the vibrant colours of the exotic landscapes he encountered. His aquatint prints became widely popular and contributed to the growing interest in exploration and exotic cultures during the eighteenth century.

William Hodges, A View of a Mosque at Mounheer, 1786, Soft-ground etching and aquatint on paper, 33.0 x 47.5 cm. Collection: DAG

Writing about the Daniells, and the difference between their work and Hodges’, Paula Sengupta recounts that ‘Thomas Daniell is responsible for raising the quality of the aquatinting process. If one were to compare William Hodges’s Select Views in India published in England in 1786 or even the Daniells’ Twelve Views of Calcutta published in Calcutta in 1788 with their later series, Oriental Scenery, published in 1795-1808, one can see the difference in quality. While in the early works the coarse basic tone of engraving is swamped by heavily applied colour, in Oriental Scenery the colour is held under great control.’

The Daniells’ process was described at length by Thomas Sutton, beginning with ‘a highly polished copper plate (that) is coated with wax’, although they worked with iron and steel plates too. Thereafter, the process is similar to those employed today, as Sengupta suggests, ‘progressively ‘stopping out’ the light areas with an acid-resisting substance and then placing the plate in a box containing thousands of particles of resin that are allowed to settle evenly on the plate and, thereafter, are ‘fixed’ to the surface by heating. The plate is then etched in an acid bath to varying degrees of darkness. ‘The resultant print consists not of lines of varying depths or thickness as in etching or copper-plate engraving, but of tones.’ The emphasis on tonal gradation allows for greater detailing of architectural forms and features of the landscape in the Daniells’ prints – especially when compared with Hodges’ more ‘impressionistic’ or ‘exaggerated’ drawings, according to some commentators, which often provided inaccurate information. For instance, in the work he titled A View of a Mosque, at Mounheer from 1786, the principal building shown there (and in the next plate) is not a mosque, in fact, but a tomb—of the Sufi saint Makhdum Shah Daulat—though there is a small mosque in the same compound, which is visible to the left of this plate. The dargah was built in Maner in 1616 by one of the saint’s disciples, Ibrahim Khan Fath Jung, who was then serving Jahangir as governor of Bihar.

Thomas Daniell, The Mountain of Ellora, 1803, Aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 18.0 x 72.0 in. Collection: DAG

No easy differentiation can be emphasised between the techniques of colonial printmakers and their postcolonial counterparts, although some artists have self-consciously employed the process towards achieving different ends from earlier artists. In the work of Anupam Sud (b. 1944), for instance, or Somnath Hore (1921-2006), the purpose was seldom underwritten by a desire for maximum ‘detailing’ or delineation of built structures, but were adopted for interior, psychological explorations of self, identity and shades of violence or struggle with the world as material—often highlighted or exacerbated by the strong physical demands made by the process upon the printmaker’s body. Ramendranath Chakravorty’s (1902-1955) untitled, penumbral view of a European city at dusk, possibly of London where he learnt printmaking from Eric Gill, suggests an early attempt to ‘reverse the gaze’ onto the colonial metropolis, rendering it as a space of enchantment and mystery. The aquatint helps him achieve the tonal grades necessary to create the effect.

Ramendranath Chakravorty, Untitled, Aquatint and etching on paper, 14.5 x 34.8 cm. Collection: DAG

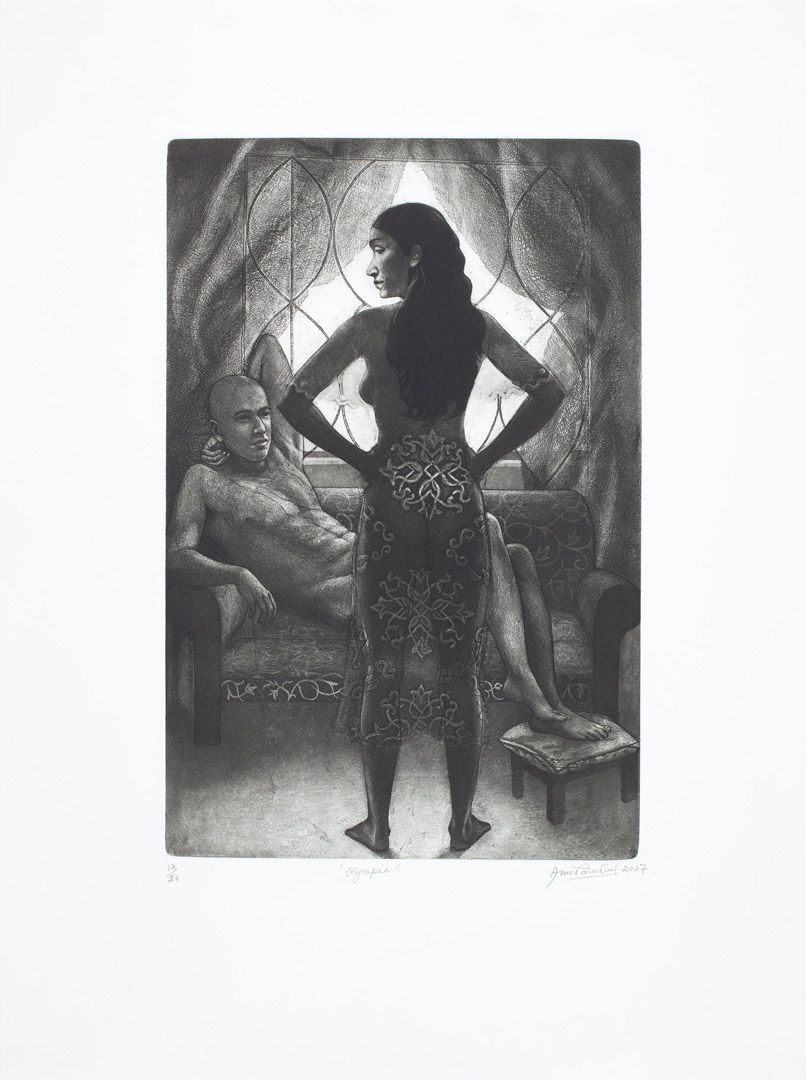

In the case of an artist like Sud, aquatinting helps spell out the shades of subtle psychological differences on display between typical heterosexual couples, such as in the work titled, Dining with Ego. Elsewhere she uses it in works attempting to counter the patriarchal gaze commonly found in art history—a sexualised form of looking that is rooted in colonial forms of subjugation or control of the other.

Anupam Sud, Dining with Ego, 1999, Etching and aquatint on paper, 50.8 x 98.3 cm. Collection: DAG

|

Anupam Sud, Olympia, 2007, Etching and aquatint on paper, 49.5 x 32.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

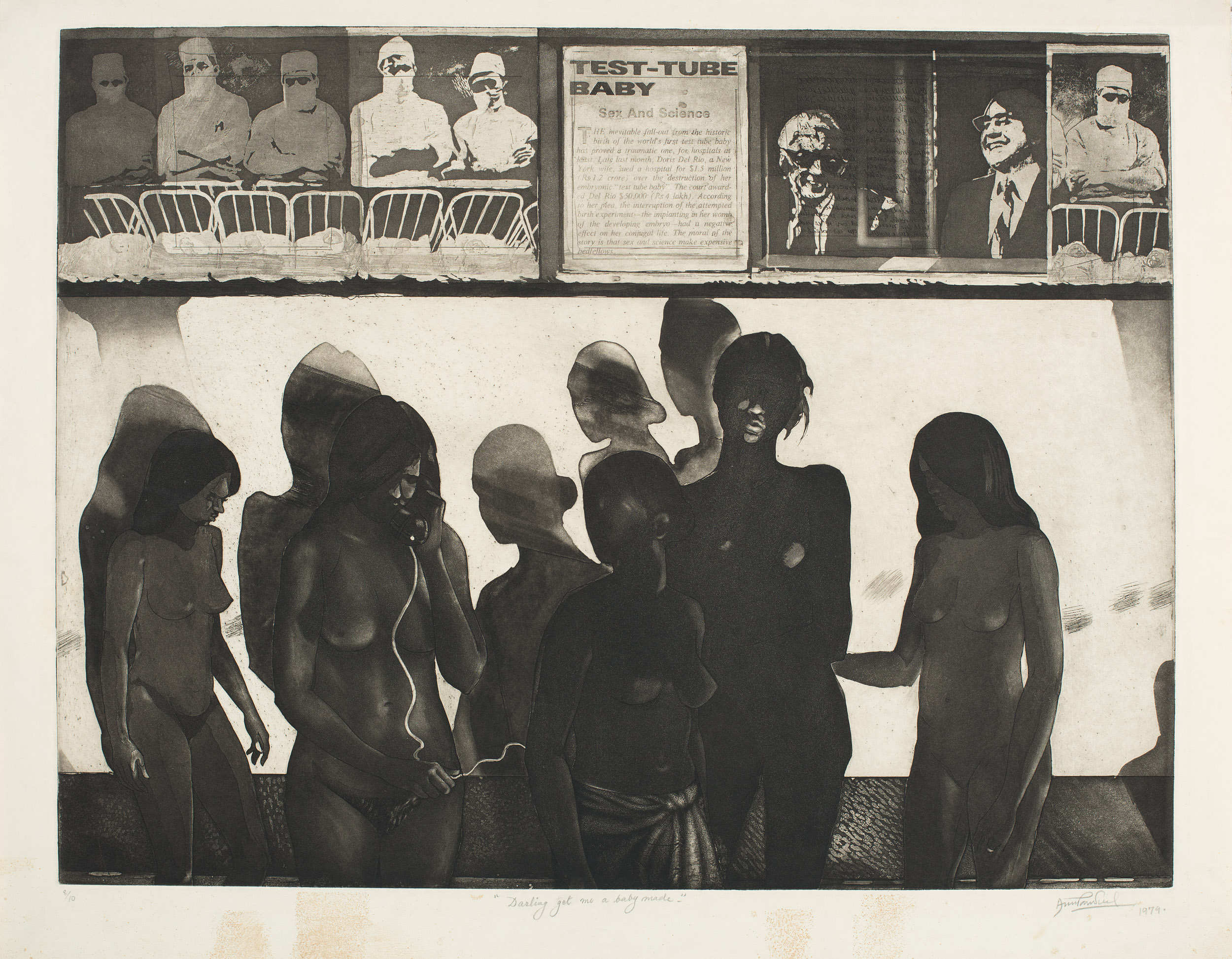

Modern and contemporary artists often use photographic methods in combination with aquatint. Light-sensitive materials can be exposed to light through a negative, creating intricate patterns on the plate. This process, called photogravure, allows for detailed photographic images to be incorporated into aquatint prints. Anupam Sud has responded creatively to aquatint processes across her career, including using photoprocessing in some of her works. They add to her themes of gender critique as well by emphasising the implications of reproduction as a mechanical technique that, nonetheless, requires elaborate human intervention, drawing attention to the cultural force of ‘reproductive heteronormativity’. As Gayatri Spivak puts it: ‘Reproductive heteronormativity is a simple notion: the normal thing for not just human beings but animal beings is for the male and female to copulate, to reproduce, and thus to continue life on Earth. Therefore, this is normal.’

Due to the experiments of modern artists like Sud and Hore, the aquatint found new ways of intervening into art-making as a conceptual and thematic force as well.

Anupam Sud, Darling Get Me a Baby Made, 1979, Etching, aquatint and photoprocess on paper, 48.8 x 64.0 cm. Collection: DAG