Term of the Month: Provenance

Term of the Month: Provenance

Term of the Month: Provenance

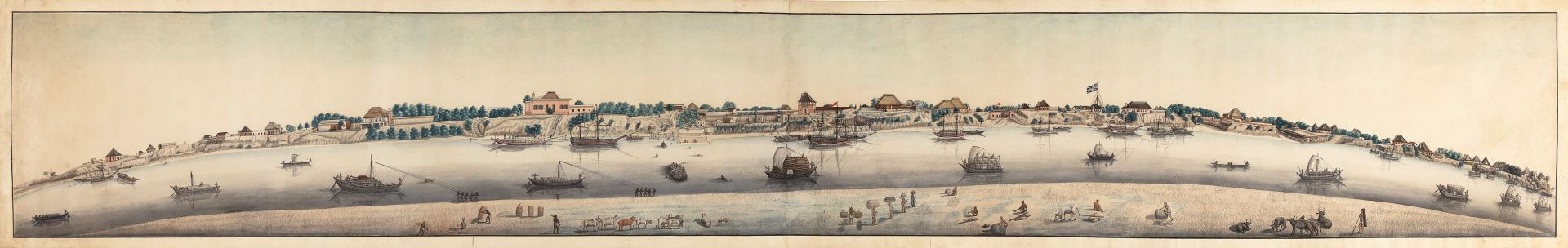

Unknown Artist, Company Painting, Panorama of a Small British Station on the Ganges (detail), Watercolour on paper, c. 1800, 11.0 x 76.5 in.

One of the most important ways in which a work of art is authenticated is by checking its provenance. What does provenance mean and how does it affect the identity of an artwork itself? The concept has evolved historically over the years; below, we try to highlight some of the important aspects of this debate in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art.

The word ‘provenance’ is derived from the French word ‘provenir’, meaning ‘to originate’. It can be simply defined as the historical record pertaining to the ownership of an artwork or object. Generally used to trace shifting ownership for individual works of art, provenance research now occupies a complex territory of work that can address moral obligations around owning or (mis)appropriating artwork under conditions of war or coercion, legal challenges to determine attribution and social histories of collecting art, or indeed determining what counts as collectible works of art in the first place.

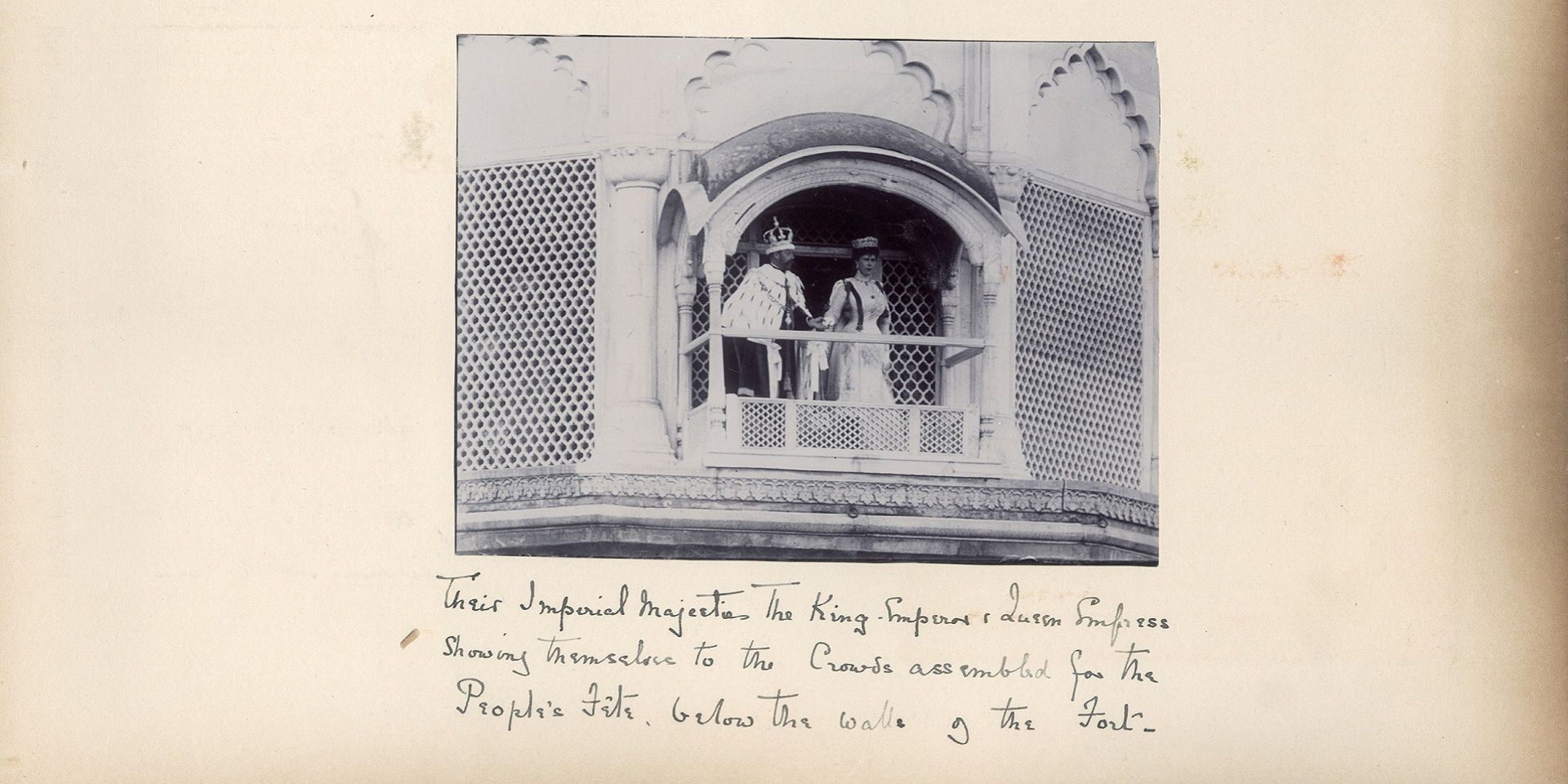

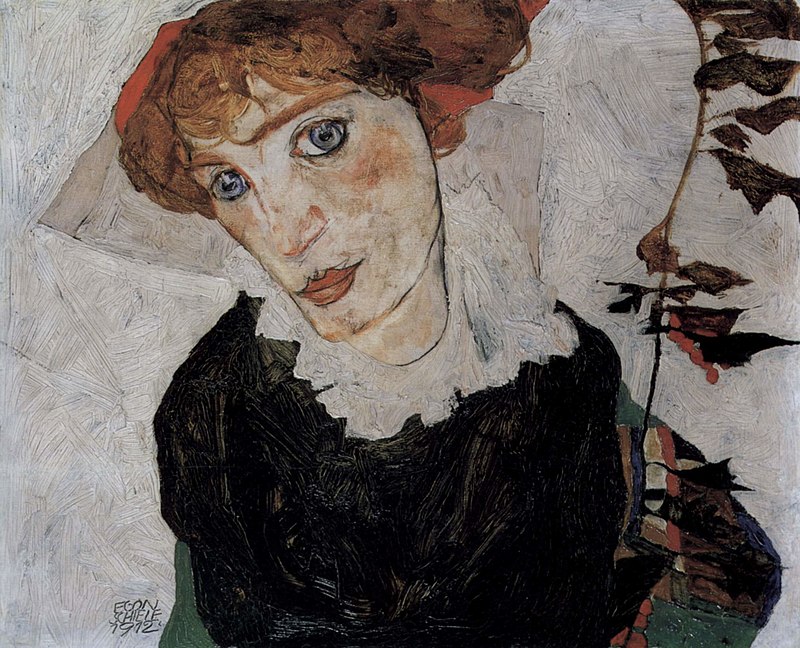

Egon Schiele’s Portrait of Wally, an oil painting made in 1912, was collected by Rudolf Leopold in 1954 and eventually found its way into the collection of the Leopold Museum in Austria. During a display in the United States of America, it was claimed as Nazi plunder by the Jewish family that had owned the painting earlier. The claim was eventually settled by the Museum. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.

Some of the major historical events of the twentieth century have complicated our understanding of provenance beyond its simple brief of record-keeping: such as the two world wars and the Nazi-era in Germany, when many Jewish collectors had their collections taken away by government officials under coercion; and decolonisation, which brought to the fore questions about the difference between common colonial products of trade and artworks of religious or cultural significance, especially those that were part of a holistic site before being expropriated to museums and private collections in the colonial capitals of Europe. More than determining the authenticity of a work of art from the past, therefore, provenance research also attempts to show if works were collected under fair conditions of sale or donation. Many museums and galleries across the world have dedicated provenance research teams working to unravel these complicated layers that determine an artwork’s history of ownership. Provenance research has been dramatised for popular audiences in shows like BBC’s long-running series Fake or Fortune?

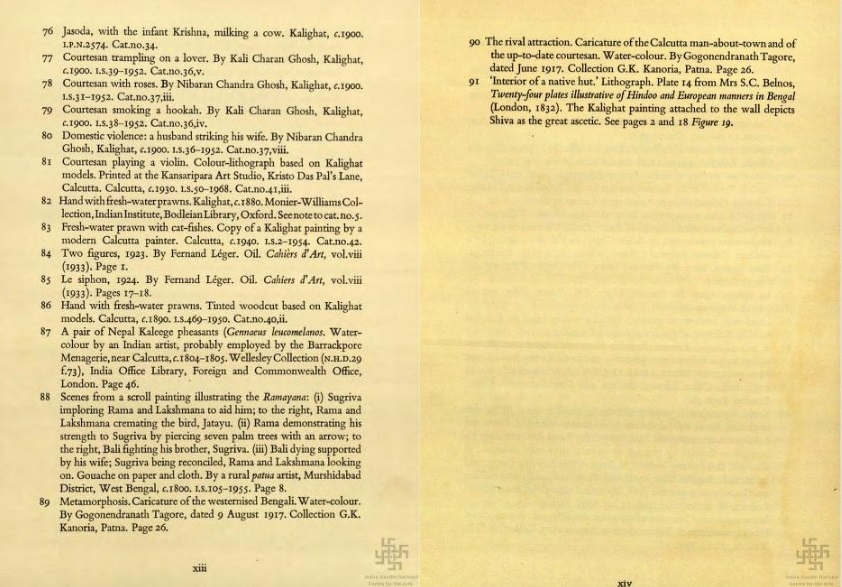

Catalogues prepared by art historians and collection curators usually carry a trail of ownership records for artworks, such as can be seen in this extract from W. G. Archer’s Kalighat Paintings (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1971). Image courtesy: archive.org

As scholars have shown, however, some contexts of provenance tend to work the other way around. Instead of a recorded history of ownership granting authenticity upon a work of art, a work could also be invented as a commodified, and collectable, work of art by granting it a documented history of past ownership, especially if the owners are influential art collectors, connoisseurs or dealers. In the case of African and Oceanic sculptures in early twentieth century Europe, this became increasingly prevalent as dealers found ways to attribute histories of ownership to anonymous (or sometimes communally made) sculptures that came to stand in for the prestige of an artist or maker’s name.

|

A photograph from the Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931, featuring a street scene from West Africa. Photographer: Leo Wehrli. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons. |

Following the Exposition Coloniale Internationale, or the Paris Colonial Exhibition in 1931 that was organised to display the diverse cultural possessions that had come under the French colonial state’s purview, several auctions were held of African sculptures that bore explicit past ownership details. These owners were well-known (European) names in the art world or members of the Parisian avant-garde, such as Paul Eluard, the poet, or André Breton, the surrealist—granting legitimacy upon these works as collectible items. As art historian John Warne Monroe puts it, ‘The goal here was not for aspiring collectors to prove themselves by unearthing their own finds in the smoking-rooms of unsuspecting retired colonial administrators, but instead to obtain objects already imbued with the auras of exalted predecessors. Each of these auctions played on a different art-historical narrative, transforming the objects on offer into works with a clearly defined place in the world of ‘high art.’’

|

Masks and objects from Africa and the Pacific Ocean islands, such as the one shown here, were widely available in European capitals from the early decades of the twentieth century. Artist or maker’s names were almost invariably missing from these. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons. |

DAG’s provenance research team, one of the first of its kind in the Indian art world, conducts painstaking work ascertaining the record-trail for all historical works that it acquires. In its ongoing ICONIC Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art exhibition, a work has been included that depicts a panoramic view of the Ganges. It is a Company painting by an unknown artist, titled Panorama of a Small British Station on the Ganges. Its provenance note makes clear that the work was first in the possession of James Nathaniel Rind (1756-1814), who was primarily a collector of natural history drawings by Indian artists. He was stationed in India from 1778 to 1804 and served in the 18th (and later 14th) Native Infantry and was made a Brigade-Major in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1801. Having been passed down to his family members in the subsequent generations, it was eventually acquired from the collection of Niall Hobhouse, a contemporary collector of architectural drawings. Its provenance record bestows a legitimacy on it as a work of art that was produced in a specific time, allowing scholars to treat it as an authentic historical document as well. Thus, even if works were produced by artists whose names are lost or unknown, a thorough documentation of its historical passage through different collections can bestow a value upon it that is comparable to any other work of art today.

Unknown Artist, Company Painting, Panorama of a Small British Station on the Ganges, Watercolour on paper, c. 1800, 11.0 x 76.5 in. The verso label on this work includes a label for ‘Hobhouse Limited’, and the Provenance note reads ‘James Nathaniel Rind (1756-1814), and by descent’

Further Reading

John Warne Monroe. ‘The Market as ‘Artist’: The French Origins of the Obsession with Provenance in Historical African Art’. Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture, Volume 12 (2018), Issue 1, pages 52-70

International Foundation for Art Research. ‘Provenance Guide’. IFAR Homepage, accessed 22 February, 2023

Philadelphia Museum of Art. ‘Provenance Research’. Philamuseum, accessed 22 February, 2023

Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa. ‘Niall Hobhouse’. The Form of form, accessed 22 February, 2023