TERM OF THE MONTH: CARICATURE

Further Reading

related articles

Gaganendranath Tagore, Confusion of Ideas, Lithograph on paper. Collection: DAG

How did the art of caricature originate? And what was its significance in the world of colonial and modern India and South Asia? We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art.

The word ‘caricature’ has its roots in the Italian language, meaning ‘to load’ or ‘to exaggerate’—with an emphasis on facial distortion. Caricature originally referred to a method of drawing or painting that highlighted and exaggerated the prominent features or characteristics of a person, animal or object to create a humorous or satirical effect. The term gained popularity in the eighteenth century and spread throughout Europe as a form of satirical art.

|

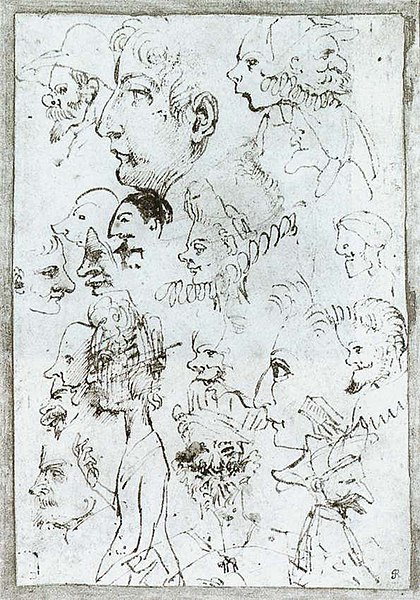

Annibale Carracci, Sheet of caricatures, c. 1595, Pen and ink, 7.91 x 5.47 in. Image courtesy: The British Museum and Wikimedia Commons |

Francisco Goya (1746—1828), one of the most renowned Spanish artists, created a series of remarkable tapestries known as ‘The Cartoon Tapestries’ between 1775 and 1791 for Charles III of Spain and then later for Charles IV of Spain; and these tapestries were intended to adorn the walls of the Spanish royal residences. However, upon closer examination, it becomes evident that these tapestries were not mere decorative pieces but rather powerful vehicles for Goya's socio-political commentary against a fast-transforming (and imperial) Spain that was grappling with issues such as class disparity, corruption, and the abuses of power. Goya used caricature in his tapestries to emphasize social flaws and the absurdity of human behaviour. His characters are grotesquely exaggerated, their facial expressions and physical features highlighting their moral decadence and corrupt nature. Caricature, in the hands of artists like Goya or Honore Daumier, became a tool of socio-political critique. While writing a critical history of the caricature, however, it is worth noting that a wide range of such caricatures made in the past as well as the present are powerful vehicles of racism, misogyny and exclusive nationalism in the world.

|

Francisco de Goya, The Straw Manikin, 1791-92, Oil on canvas, 105.1 x 62.9 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

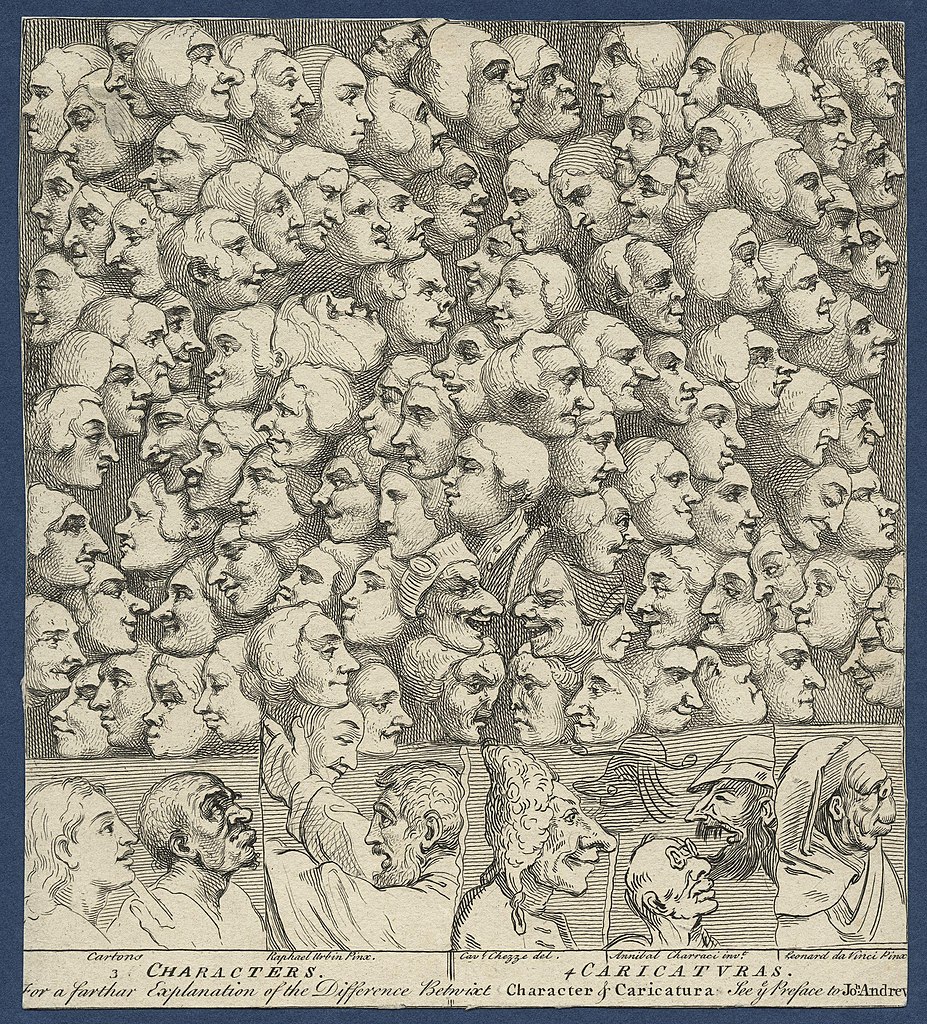

Major artists now associated with cartoons or satirical art have also resisted the label of a caricaturist, such as William Hogarth (1697—1764), who made a print titled Characters and Caricaturas (originally as a subscription ticket for another set of prints) in defence against claims that his art was more about caricatures than characters.

|

William Hogarth, from Characters and Caricaturas, 1743. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

How did caricature evolve in South Asia in the colonial context?

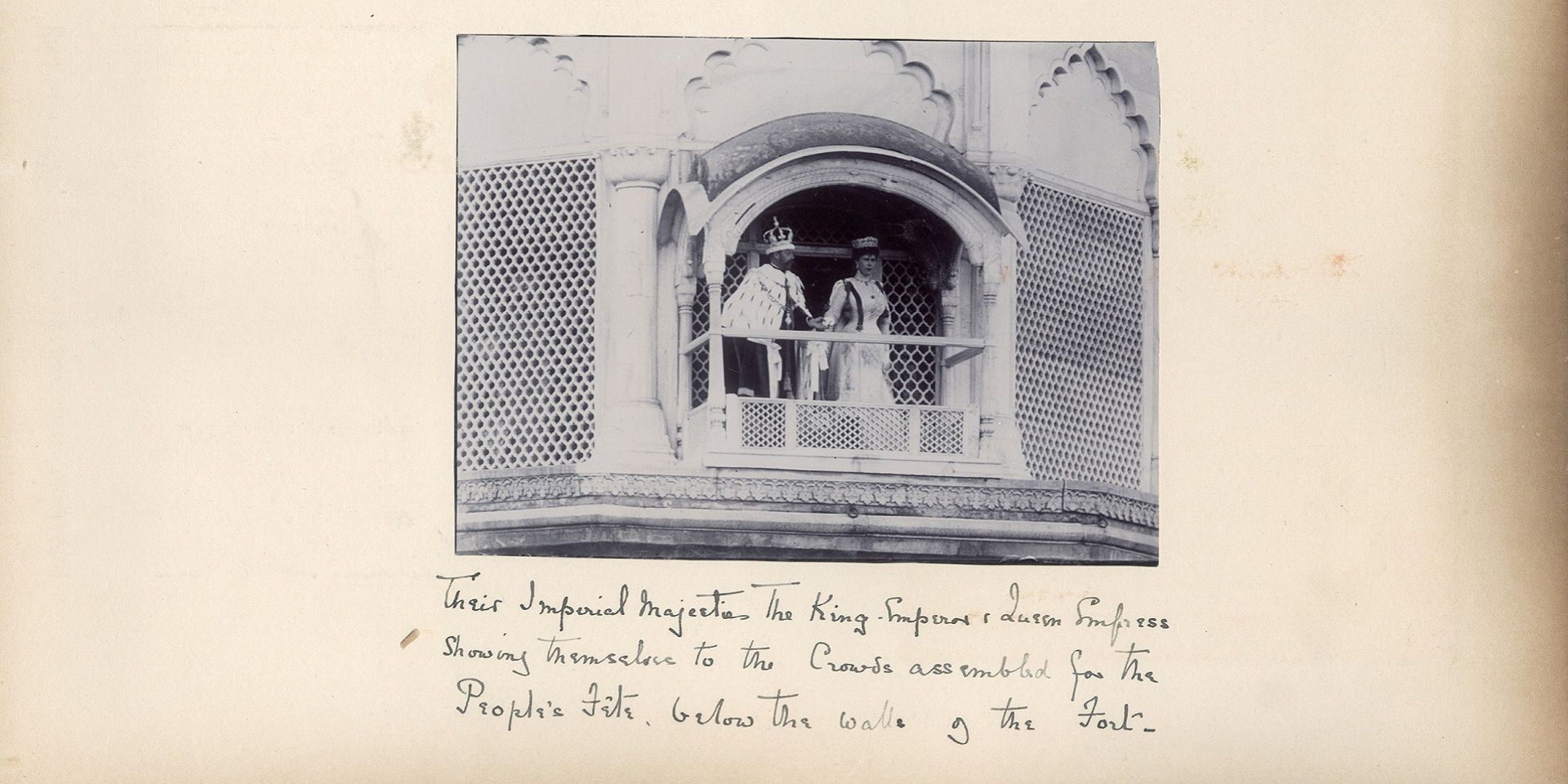

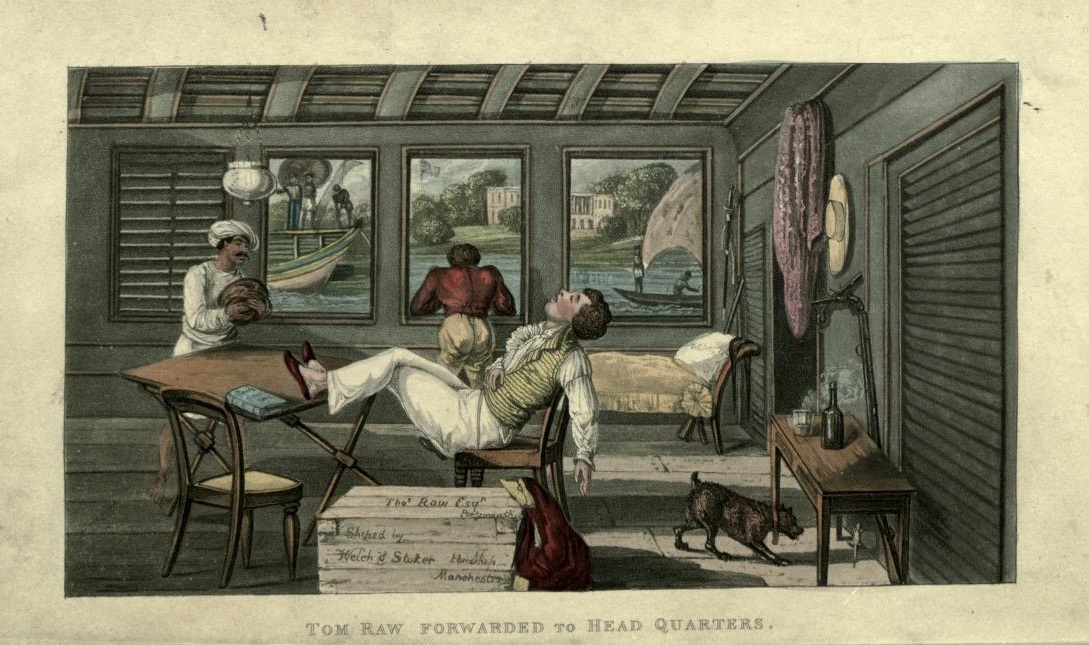

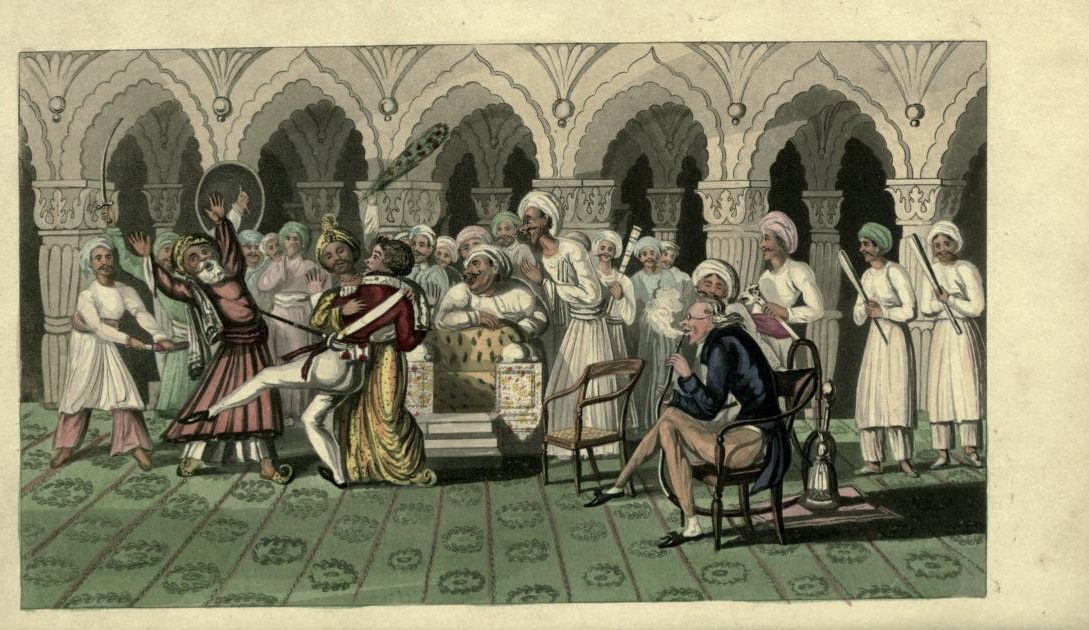

It is broadly agreed by scholars that caricature as understood by this European formulation was introduced to the Indian subcontinent during the British rule, taking root through the long nineteenth century and accommodating indigenous forms of satire and grotesquerie. Two instances, one from the ranks of the colonial British population, and another from the Indian perspective, may highlight the lay of the caricatural land as it unfolded over the century. Charles D’Oyly (1781—1845), who was born in Murshidabad and joined the Bengal Civil Service later, wrote a satirical poem (also described as a ‘burlesque’) titled Tom Raw, the Griffin (1828), that painted a vivid picture of the misadventures of its eponymous protagonist, giving us a glimpse into the world of colonial India at the time. Raw, a naive and gullible young man, embarks on a journey to India, filled with misguided notions of glory and riches, desirous of becoming a newly minted ‘nabob’. However, he quickly becomes the target of various swindlers and cheats who exploit his innocence for their personal gain. The poem was accompanied by twenty-five engravings, featuring the satirical episodes described in the poem. It represented a flowering of many such caricatural works that sought to mock the colonial discourses of progress and civility, which were shown to be fig-leaves for covering up profiteering, corruption and the violent oppression of local populations.

Engraved page from Charles D'Oyly's Tom Raw, the griffin, 1828. Image credit: archive.org

Engraved page from Charles D'Oyly's Tom Raw, the griffin, 1828. Image credit: archive.org

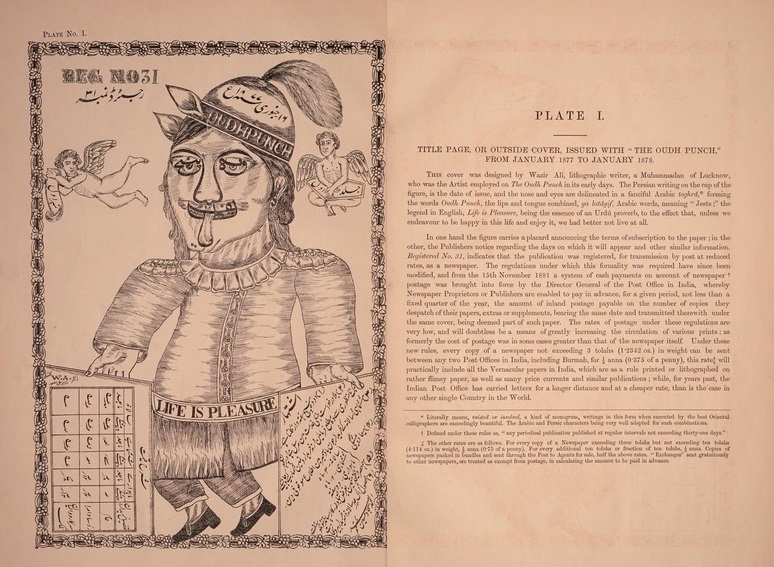

The Awadh Punch was an Urdu satirical weekly published from Lucknow, India from 1877 to 1937. It was founded and edited by Munshi Sajjad Husain and was modeled on Punch, the famous London-based weekly magazine from which it also derived its name (as did various other such Punches across India). The magazine was a staunch critic of British rule and frequently rooted for Hindu-Muslim unity and a joint fight against the imperial regime, even though it inhabited a milieu where such satire occasionally slipped into uncritical celebrations of conservative and oppressive indigenous traditions. Drawing from a vast repertoire of satire and humour in Urdu prose and verse centred around the nawabi court of Awadh, it built upon those traditions with richly comic illustrations that ranged across issues from the middle east and Turkey to Tibet, which were hot sites of colonial misadventures, aside from observing political shifts in the United Provinces. As Mushirul Hasan put it, ‘The laughter was long and loud, the jokes full-blooded and vulgar and the criticism personalized and offensive. Few could escape the influence of Avadh Punch.’ In 1881, a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, Archibald Constable, first introduced The Avadh (Oudh) Punch to English-speaking readers by publishing a set of illustrations from the magazine with his own introductions to each plate. His express aim was to counter the notion that Indians have no sense of humour. Hasan writes, ‘Refuting this view, he pointed out that ‘a great number of the old, witty or grotesque, stories and songs, that have long been current in the West, owe their origin to the East’.’

One of the plates from Archibald Constable's collection of 'Oudh Punch' from 1881, featuring a cover designed by Wazir Ali. Image courtesy: archive.org

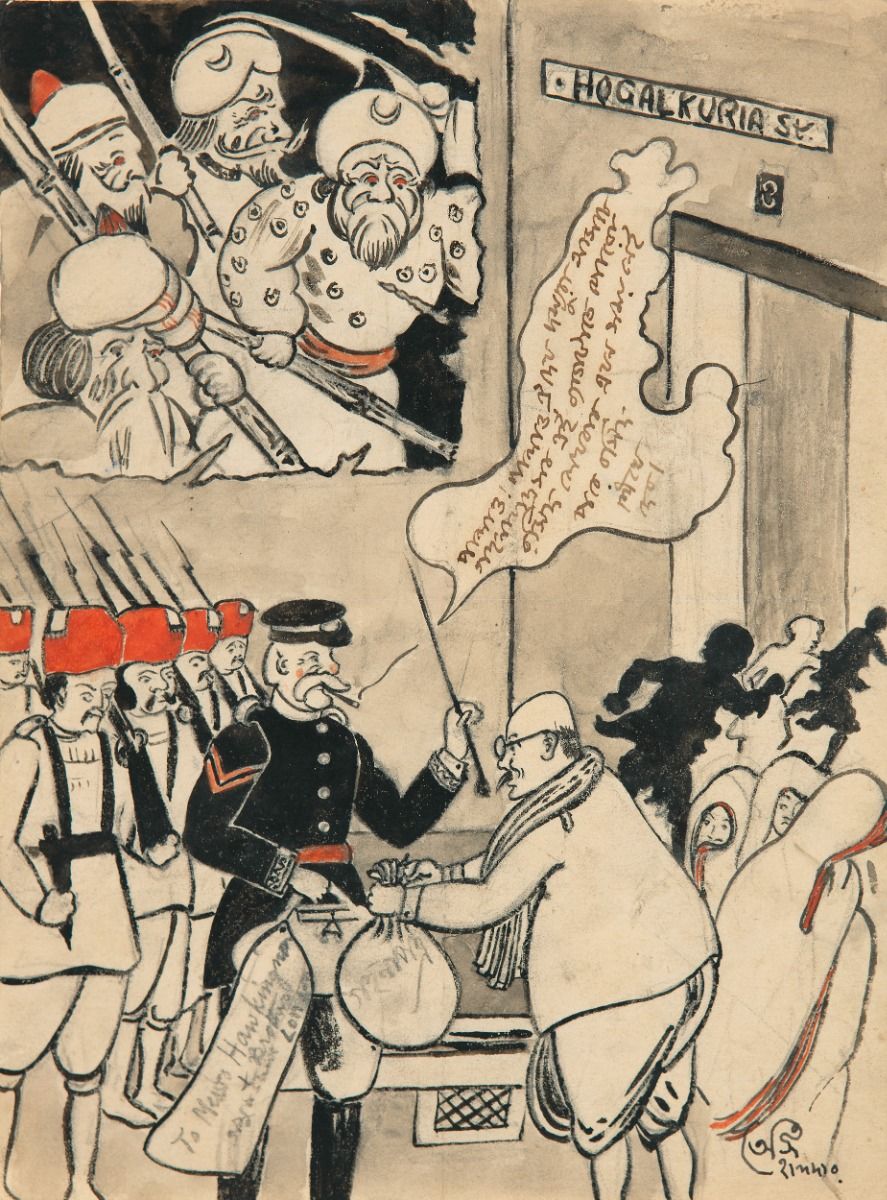

The Awadh Punch also supported the Swadeshi Movement and published a cartoon representing foreign goods as a serpent trapped in the talons of a colossal bird labelled ‘Swadeshi’. Aside from Kalighat pats, which also brought a strain of conservatism to its art of satire and caricature, progressive and critical anti-colonial caricature was pioneered by artists like Gaganendranath Tagore in Bengal, who used it as a tool to express dissent and provoke laughter at oppressive authority. He used caricatures to articulate strong discontent towards bourgeois nationalists, colonial apologists, and the caste system. His work steered clear from tendencies that lamented the loss of conservative morals in Indian women due to the arrival of Western values, for instance, so that his politics stood at the limits of such popular sentiments. Artists like Abanindranath Tagore and Asit Kumar Haldar also used caricature to highlight the moral decadence of British colonial forces and their Indian bourgeois collaborators, or rather, partners-in-crime. In Haldar’s comic illustration we can see a colonial police force being bribed by a native businessman (or, babu) to look the other way while dacoits—perhaps imagined ones—are shown escaping at the back.

|

Asit Kumar Haldar, Untitled, Gouache and graphite on paper, 9.0 x 6.7 in. Collection: DAG |

|

Gaganendranath Tagore, Confusion of Ideas, Lithograph on paper. Collection: DAG |

Since independence, caricatural art has spread rapidly in India to include modern painting (such as the works of Paritosh Sen and Dharmanarayan Dasgupta, among others), folkloric forms (like Odisha’s ‘Rabana Chhaya’) and many other media, especially the newspaper comic, suggesting its longevity and popularity with the masses as an easy but essential manner for accommodating critique in their everyday relationships with power that may not always be changeable, but can certainly be made laughable.

|

Dharmanarayan Dasgupta, Untitled, Tempera on canvas |

Further Reading

Mushirul Hasan. Wit and Humour in Colonial North India. Niyogi Books: New Delhi, 2008

Partha Mitter, ‘Cartoons of the Raj’, History Today, 47:9, 1997, pp 16-21, p 19

Britannica. ‘caricature and cartoon’. Accessed 25 May, 2023

Anna Ingram. ‘Francisco Goya’s Tapestry Cartoons’. Daily Art Magazine, April 2023

Sanjukta Sunderason. ‘Arts of Contradiction: Gaganendranath Tagore and the Caricatural Aesthetic of Colonial India’. South Asian Studies, Volume 32 Issue 2, pg. 129-143, 2016.