The Museum and the Moving Image, Part 1

The Museum and the Moving Image, Part 1

The Museum and the Moving Image, Part 1

From the breathless sprint through the Louvre Museum in Jean-luc Godard’s Bande à part (Band of Outsiders, 1964) to the contemplative meanderings found in Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours (2012), and the blockbuster allure of The Da Vinci Code (2006), or Night at the Museum (2006) cinema has depicted museums in strikingly varied ways. This year, as we joined the international celebration of Museum Week through our event ‘A Weekend in Museums,' we sought to reimagine and interrogate the very idea of the museum and its archival function.

Our aim was to explore the intricate structural affinities that exist between museums and films. As scholars like Eilean Hooper-Greenhill have posited, museums and films are both sites where culture is actively constructed, mediated, and consumed. Our three weekend programs thus did not seek to provide simple answers, but rather served as experimental inquiries, posing fundamental questions about how film might reframe the concept of the museum—materially, metaphorically, and methodologically. Through these explorations, we hoped to illuminate the ways in which cinema allows us to see museums anew, reframing their spaces and stories in ways both unexpected and profound.

|

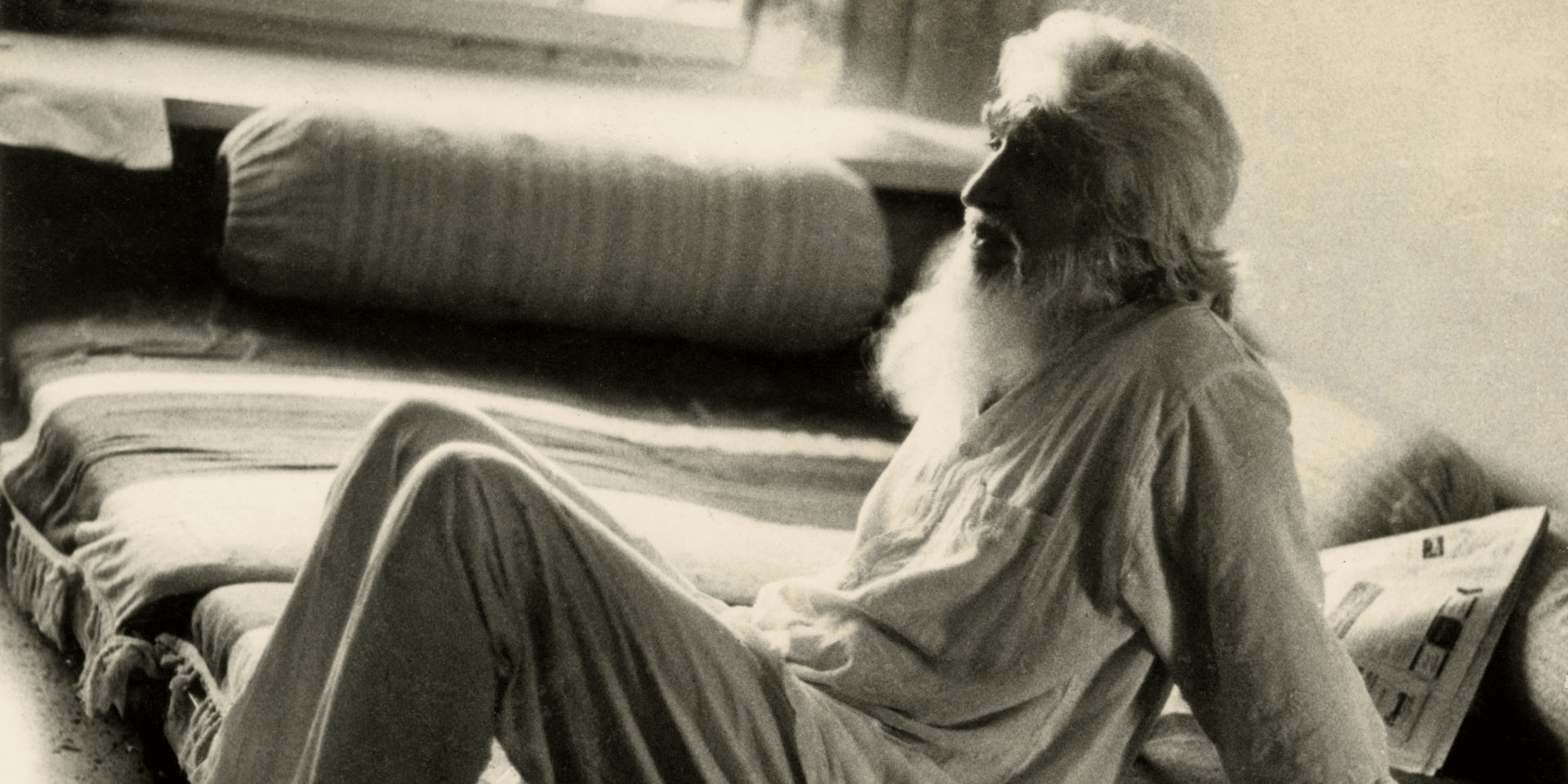

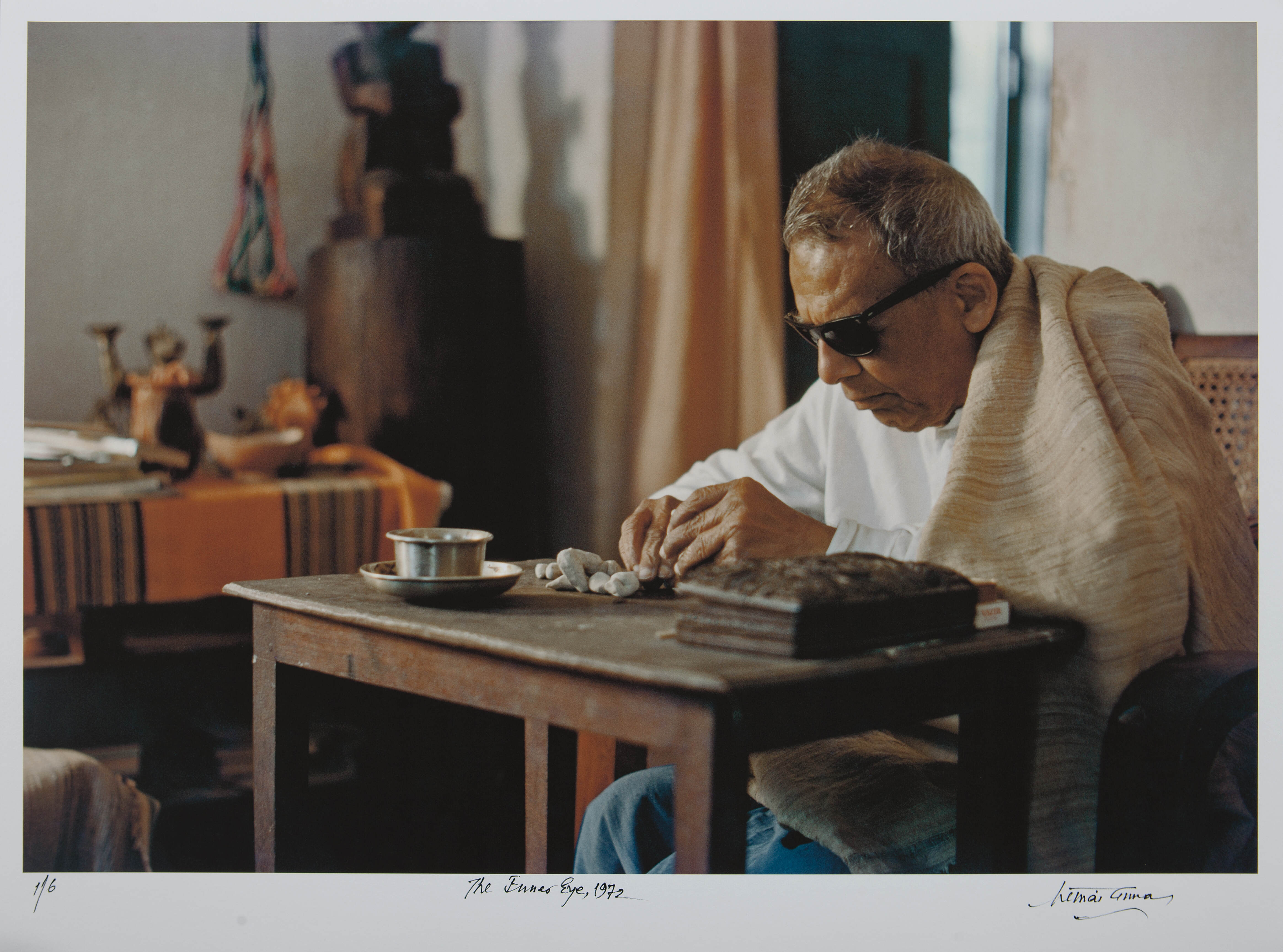

Nemai Ghosh, The Inner Eye, 1972 - 2012, 24.0 X 16.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Since moving out of our former space at Kolkata’s Old Currency Building, where we hosted a comprehensive Bengal art exhibition titled ‘Ghare Baire’, and in the absence of a permanent venue in the city, we have sought to push the boundaries of how and where art can be experienced. Through our programming initiatives, we have worked to move beyond the traditional museum model— in effect, dematerialising it by reducing its dependence on physical objects and reimagining it as a mobile, interpretive, and discursive space. This approach has allowed us to engage with our artworks outside the spatial and chronological limits of conventional display, fostering rich, cross-cultural conversations. Film has been useful tool in our journey, bringing in a system of references, initiating conversations and creating interventions, enabling us to abolish distances across cultures and epochs, and making us question:

What does it mean to expand in space and curate in time?

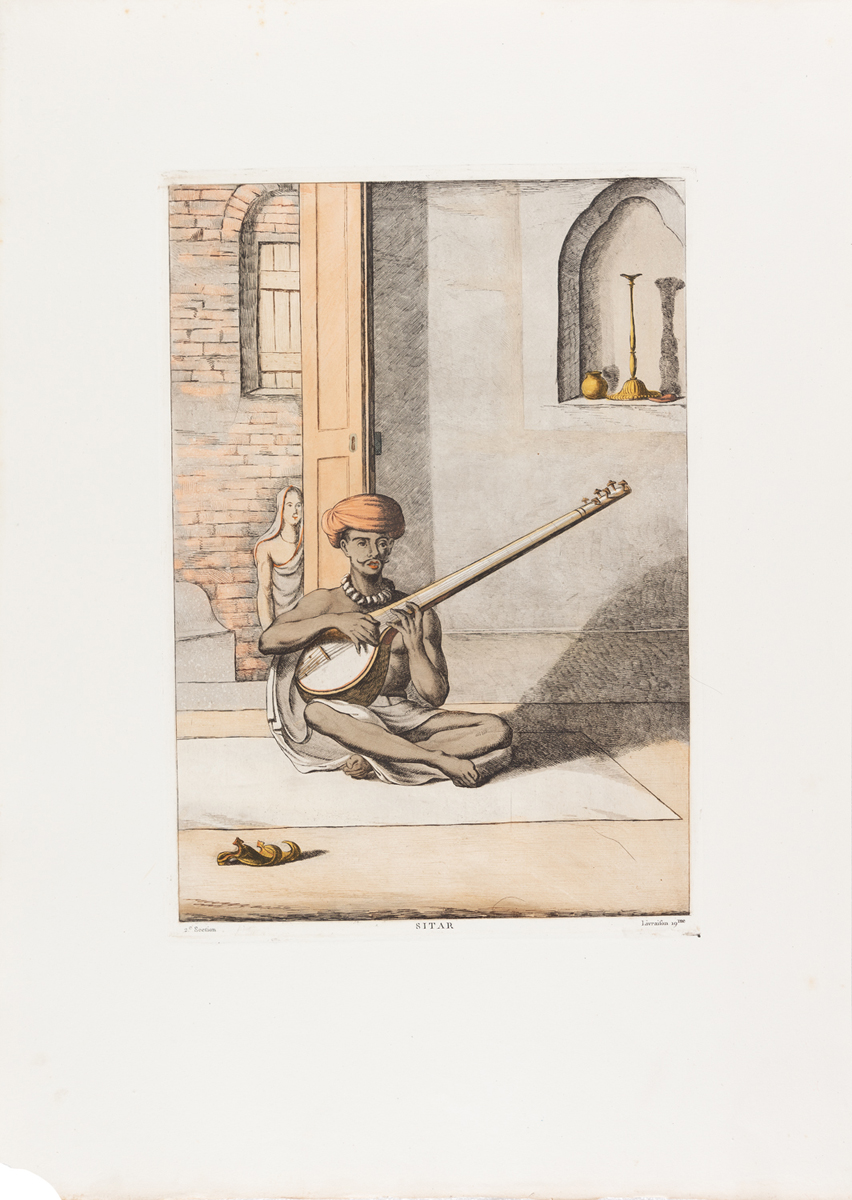

In The Story of the Sitar, which explored the sitar’s evolutionary history through a discussion and concert with sitarist Subhranil Sarkar at the Ramdulal Nibas, we showed a film exploring the intricate process of sitar-making from its origins in the gourd to the final instrument. A key visual reference within this narrative became F.B. Solvyns’ late-nineteenth century etching of a sitar player, which helped situate the instrument within a longer historical continuum of adaptation and change.

The intervention of film, exhibited in the natmandir, expanded the performance space beyond its walls, bringing together its spatial and formal contexts

|

F. B. Solvyns, Sitar [sitar], 1810, Colour etching on paper, 19.0 x 13.7 in. Collection: DAG |

The film served us on two critical levels. First, in a venue renowned as a dedicated space for Indian classical music—such as the Ramdulal Nibas—this intervention disrupted traditional modes of performance by combining two seemingly separate elements: live performance and the craftsmanship behind it. This expanded the performance space to include in-depth conversations about the rich history of sitar-making and its artisans. Second, by engaging both the immediate experience and the formal legacy of performance at the nat-mandir, the film enabled an indirect mode of communication. Through this approach, we were able to situate the complex, layered histories of the sitar’s community of performers and makers within a contemporary framework, creating a dynamic dialogue between past and present.

The visitor’s journey through a museum—moving between floors, navigating rooms, and pausing before different walls—bears an uncanny resemblance to the mental adventures of the film viewer, whose perception stitches together disparate gestures and rhythms, moving through narrative detours and moments of surprise within the cinematic sensorium. As art historian Giuliana Bruno observes, ‘The visitor’s movement through museum space is a form of embodied spectatorship, akin to the filmic experience of montage’. In this way, the spatial logic of the museum finds a parallel in the temporal logic of cinematic montage, with both forms fostering subjective realms of meaning and associative connections.

Nemai Ghosh, The Inner Eye, 1972 - 2018, Inkjet print on archival paper, 16.0 x 23.0 in. Collection: DAG

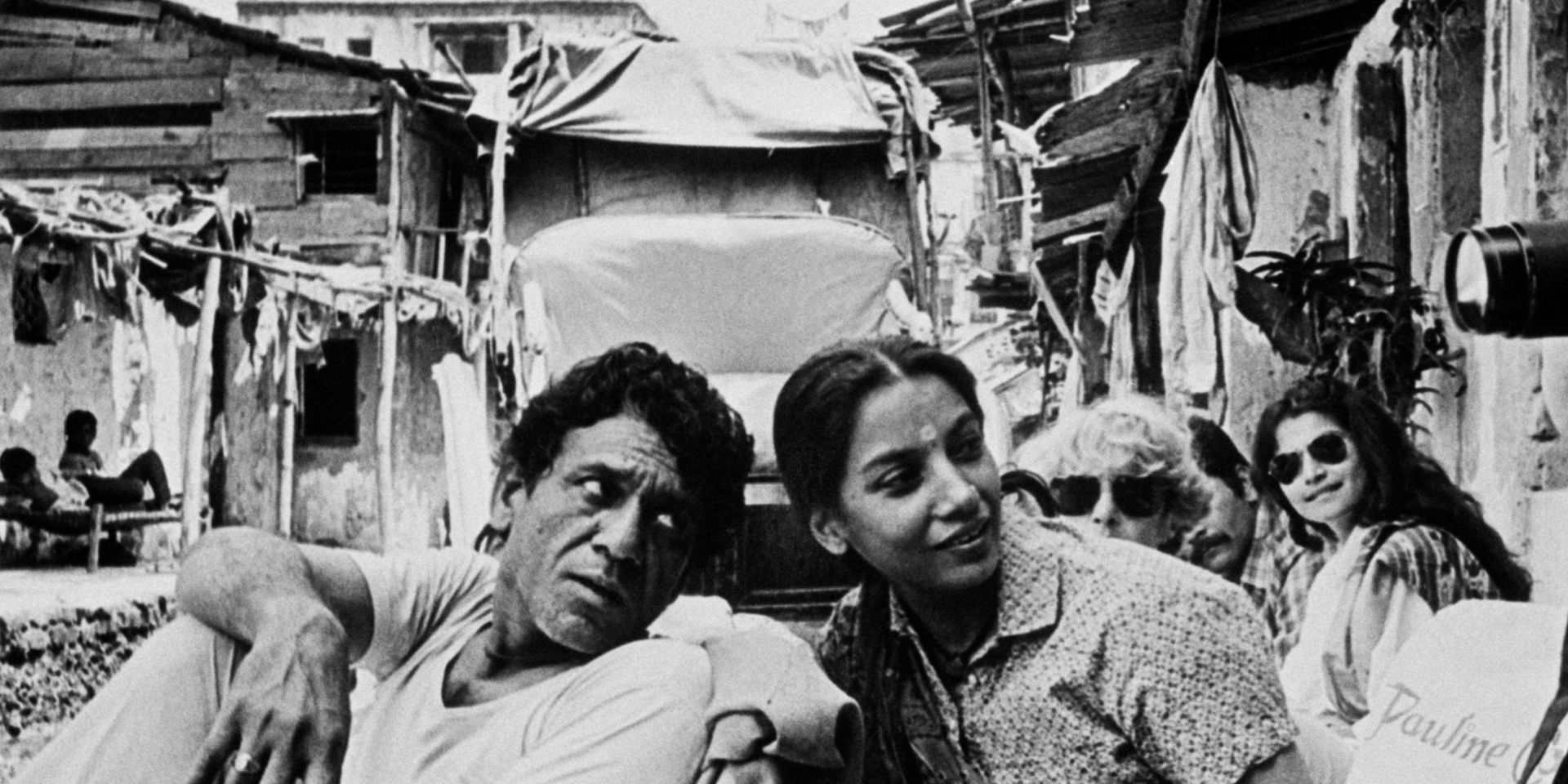

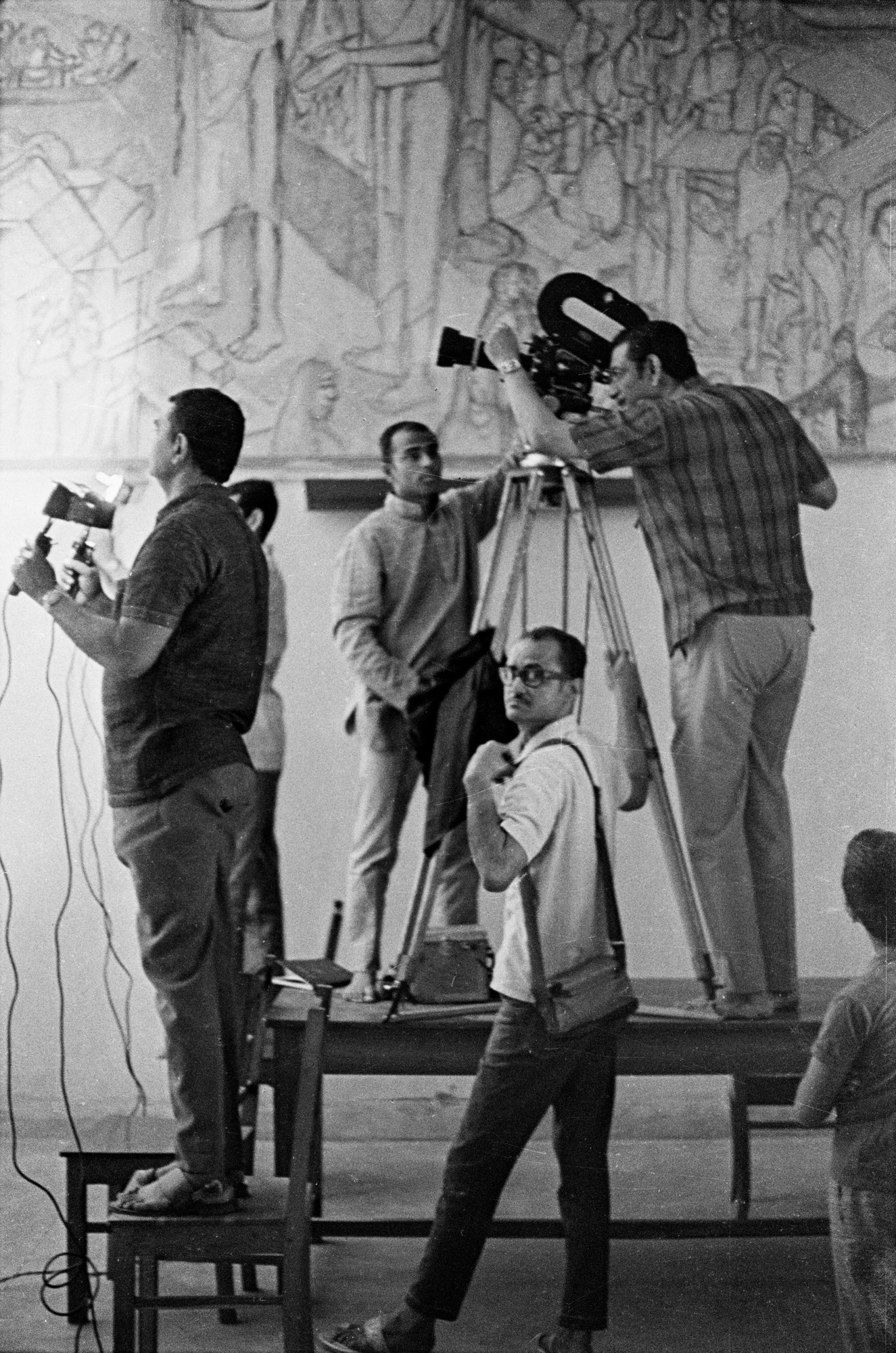

These parallels became evident in some of our other programming as well, where we curated viewing sessions that included film clips from documentaries about artists, like Benode Behari Mukherjee, in Satyajit Ray’s The Inner Eye (1972), and the dancer Birju Maharaj, in Chidananda Dasgupta’s film, also from 1972, named after the dance maestro. The moving images displayed the artists in their element, restoring their creative production to their own sensorial forms of apprehending the world and the spaces within them. In other words, it helped us recognise the process by which these artists corporeally connected their affective modes of being in the world to the works and performances they consciously crafted over time.

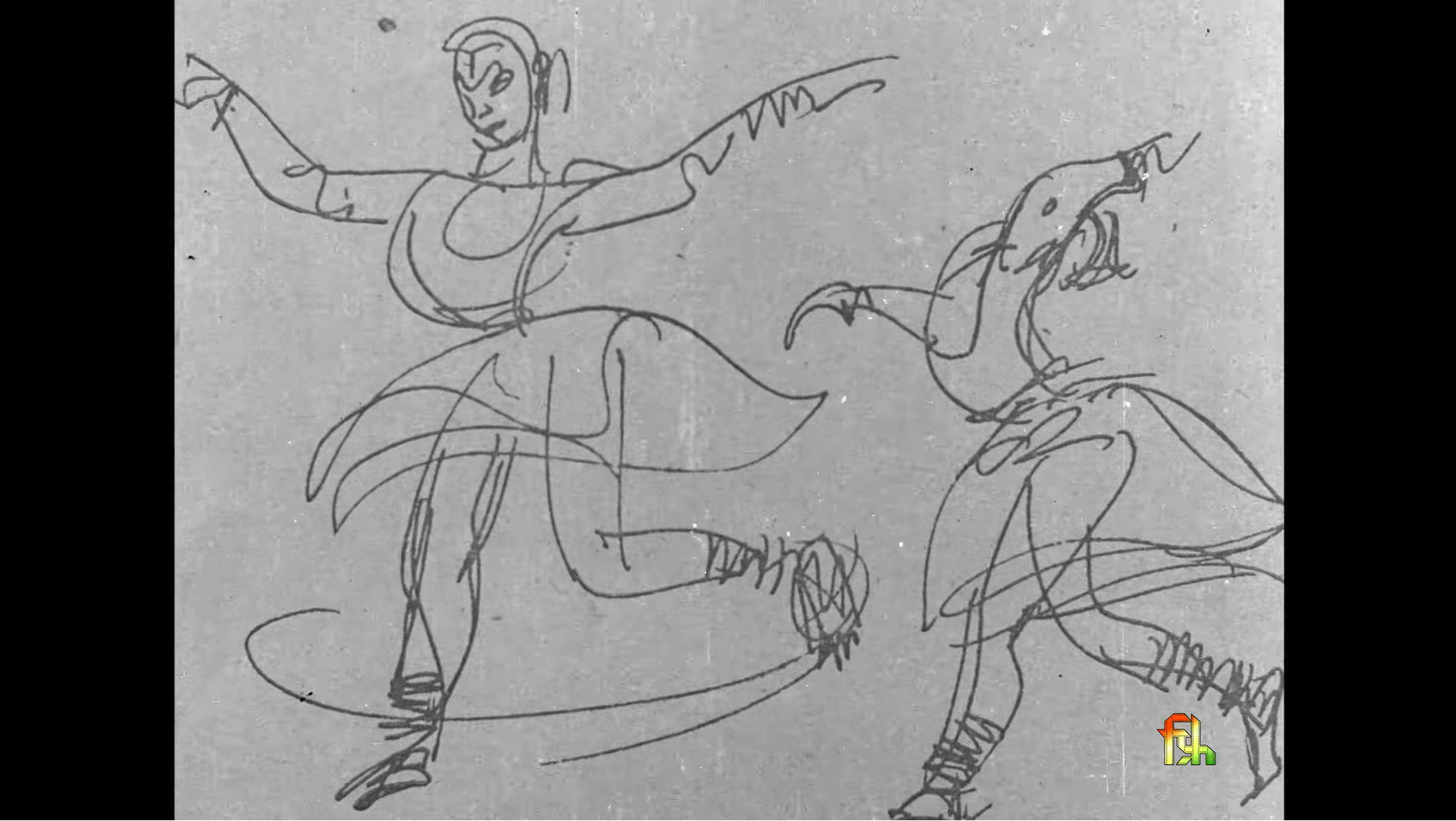

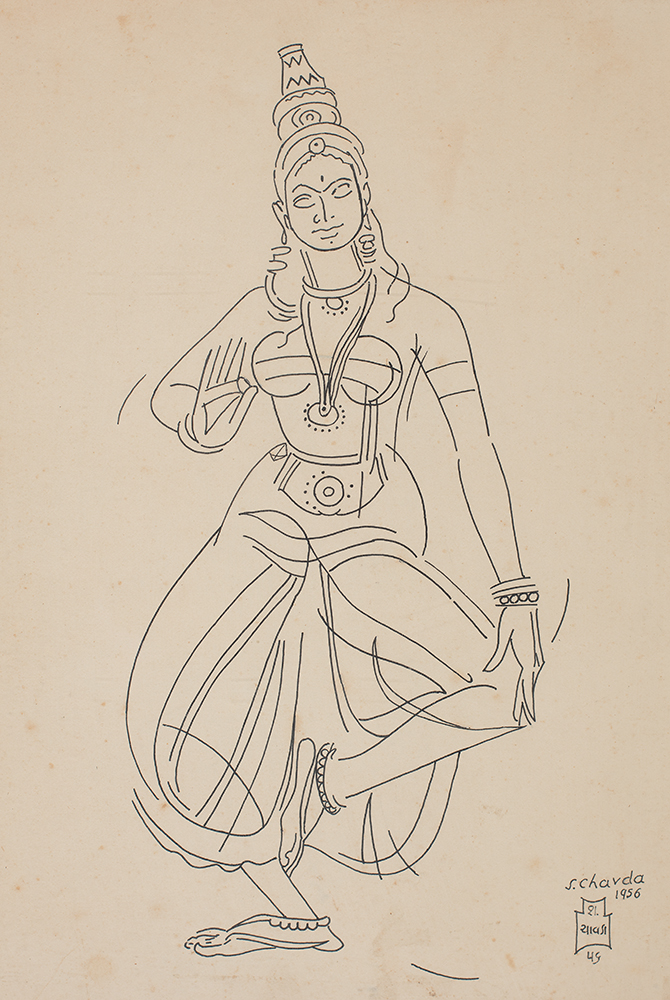

There were other discoveries to be made, as we learned about the sheer complex of connections and networks between various kinds of artists and performers who collaborated with each other to produce works across films, theatre, and painting. Dasgupta’s film on Birju Maharaj, for instance, begins with a set of sketches made by Shiavax Chavda that opens another layer of inquiry into the nature of artistic documentation as an aesthetic project—a premise that applies to Nemai Ghosh’s photographs of Satyajit Ray at work as well.

|

Shiavax Chavda, Untitled, 1956, Watercolour on mount board pasted on paper, 14.5 x 10.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Yet, cinema’s unique ability to capture immediacy, embody paradox, and disrupt linear narratives offers challenges to the material dependencies and fixed classifications of museums. Film can render the ephemeral tactile; it can destabilise the authority of the museum object by privileging sensation and temporality over static display. This dynamic potential invites us to imagine more fluid and participatory modes of engagement, destabilising traditional conceptions of what is deemed ‘museum-worthy.’ It also compels us to ask:

What truly constitutes a museum object and what criteria determine worthiness for preservation and display within these cultural institutions?

Read the second part of our essay to know more about the ways in which we have attempted to respond to these questions.