Encounters with Faces: A conversation with Aban Raza

Encounters with Faces: A conversation with Aban Raza

Encounters with Faces: A conversation with Aban Raza

Encounters with Faces:

A conversation with Aban Raza

Ranjana Steinruecke, Romila Thapar and Aban Raza at Galerie MS. Courtesy of Aaran Patel and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke.

Aban Raza is an award-winning contemporary artist from India, based in New Delhi. Through her work she confronts the diverse ways in which Indian citizens register their presence and their protests in the public sphere. In the wake of an acclaimed series of shows she sat with the editors of the DAG Journal to speak about her process.

Q. You're one of the rare artists who is responding to the politics of the present as it unfolds in this country and beyond. How do you arrive at your subjects and how do you prepare to represent it? Do you make sketches, and documents beforehand, or do you tend to work spontaneously?

Aban Raza: When I visit a site/location and perhaps hopefully feel for the cause and I tend to be engaged with it, even if it's in a very tiny capacity, then I translate it into a work but it's not only limited to that, because I also want to know more, engage more, talk to people more and understand the situation myself and amplify the voice of resistance. I too am growing as things are shaping around me to which I'm just responding.

While I'm not sure if there's a specific method, looking back, there might be the trace of one, because without visiting, I wouldn't be able to create. However, that is not entirely it either; for example, the situation in Palestine unfolds daily, and I feel a connection to the cause. Even if I can't physically visit Palestine, I want to contribute in some way, using whatever means available. I don't believe I'm unique in this; there are many others doing the same, and hopefully, there will be even more in the future. While there may not be an established method yet, I express my intention to be on the side of resistance, perhaps even by physically being present at the site.

Aban Raza, MKSS Yatra, Rajasthan, 2021, Oil on canvas, 182.8 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of Aban Raza and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke.

Q. Can you share with us your experience of visiting Shaheen Bagh, the site of the Citizenship Amendment Act (C. A. A.) protests, and the sites of the Farmers’ protests (that took place in Delhi between late-2020 and December, 2021) and how they eventually percolate into your works?

Aban: I used to visit Shaheen Bagh regularly, and I wasn't alone. It was a pivotal moment when the realization struck—let's stand in solidarity with the Constitution of India and those defending it. I also actively participated in the farmers' protest, going back and forth with some friends. During this period, we engaged in activities like painting, both ourselves and alongside the farmers. These were small actions, but they were our way of staying involved.

Q. Would you call your process primarily documentary in such cases?

Aban: I believe so because these narratives capture the lives of actual individuals—these are portraits. While they serve as documentation, they also carry an aspirational quality. There's a particular joy I aim to convey through the notion of protesting or being part of a collective. The movement transcends the confines of a painting, but it is preserved in this documented form.

Aban Raza, Shaheen Bagh, Delhi, 2022, Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 182.8 cm. Courtesy of Aban Raza and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke.

Q. Did you sketch or paint on-site?

Aban: At the protest site I am usually participating and helping out—which everyone is required to do. But I do come back (to my home/studio) and refer to photographs that I take with my phone camera. I construct a whole within those photographs but it's not an absolute translation. I would like to believe there's a lot of imagination while I'm composing it but I don't think I sit there and sketch which I used to do when I was younger.

Q. How do you see your attempt to make the grand old medium of oil painting, so to speak, into a medium for practicing a very politically sensitive and socially relevant resistance art today? And you also tend to employ figuration, rather than abstraction. Since oil painting in India has its origins in colonial art academies, and were carriers of ‘academic art’, it's interesting that you deliberately use this classical medium to do something so contemporary.

Aban: I think that's an interesting question simply because I wouldn't have termed it as classical or traditional or modern. I just thought that I have the tools, I have the means, I have a canvas, I have paints. I studied painting for four years, then I studied printmaking for two years. I didn't do painting for a very long time. I went back to painting in 2018-19, and during the Covid pandemic subsequently. It's a very wonderful medium. You can mould things, you can change things around; it takes a long time to dry so you know you can contemplate, you can sit with it. It's quite a romantic relationship in a sense.

Aban Raza, Alwar, Rajasthan, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Aban Raza and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke.

And I also think to myself: Who am I to depict them (the subjects in my paintings) beyond the fact that, ‘Hey, I can do this’. So, I place them within my artwork. Although I'm drawn towards abstraction, I must admit there's an absolute struggle within me when I'm staring at the canvas, contemplating whether I should push it further or make adjustments. I've restrained myself at times because I feel I haven't fully grasped what it takes to practice abstract art.

The journey towards abstraction is complex, and I've halted myself at this moment because there's much to understand. It's intriguing that you mention the figurative aspect, and it's worth noting that my prints, which you may not have seen, differ significantly from my paintings. This contrast arises due to the nature of the medium.

I'm also interested in the content of the figurative work. And I aim for a slightly more expressionistic form that gradually transitions towards abstraction. However, I am fully aware that there's much work to be done. Even with the 2022 exhibition, for which I'm receiving this award, I feel like I might have restrained myself prematurely. But it's important to emphasize that I still appreciate and take pride in these works. I believe that the presence of a face and a body in the artwork itself makes a statement—a declaration of those individuals engaged in street protests. So, while I recognize the relevance of oil painting, there's a continuous journey of exploration and improvement ahead.

Q. Looking at your series titled ‘Luggage People and a Little Space’—where you depict the various ways in which public and private spaces are inhabited by people or used by people—what value do you think you place on knowing your subjects personally before painting them? And how did events like the pandemic influence your viewing of shared public places?

Aban: The first exhibition had pieces that emerged organically through the act of expression, driven by a desire to return to painting and viewing it as a form of artistic expression.

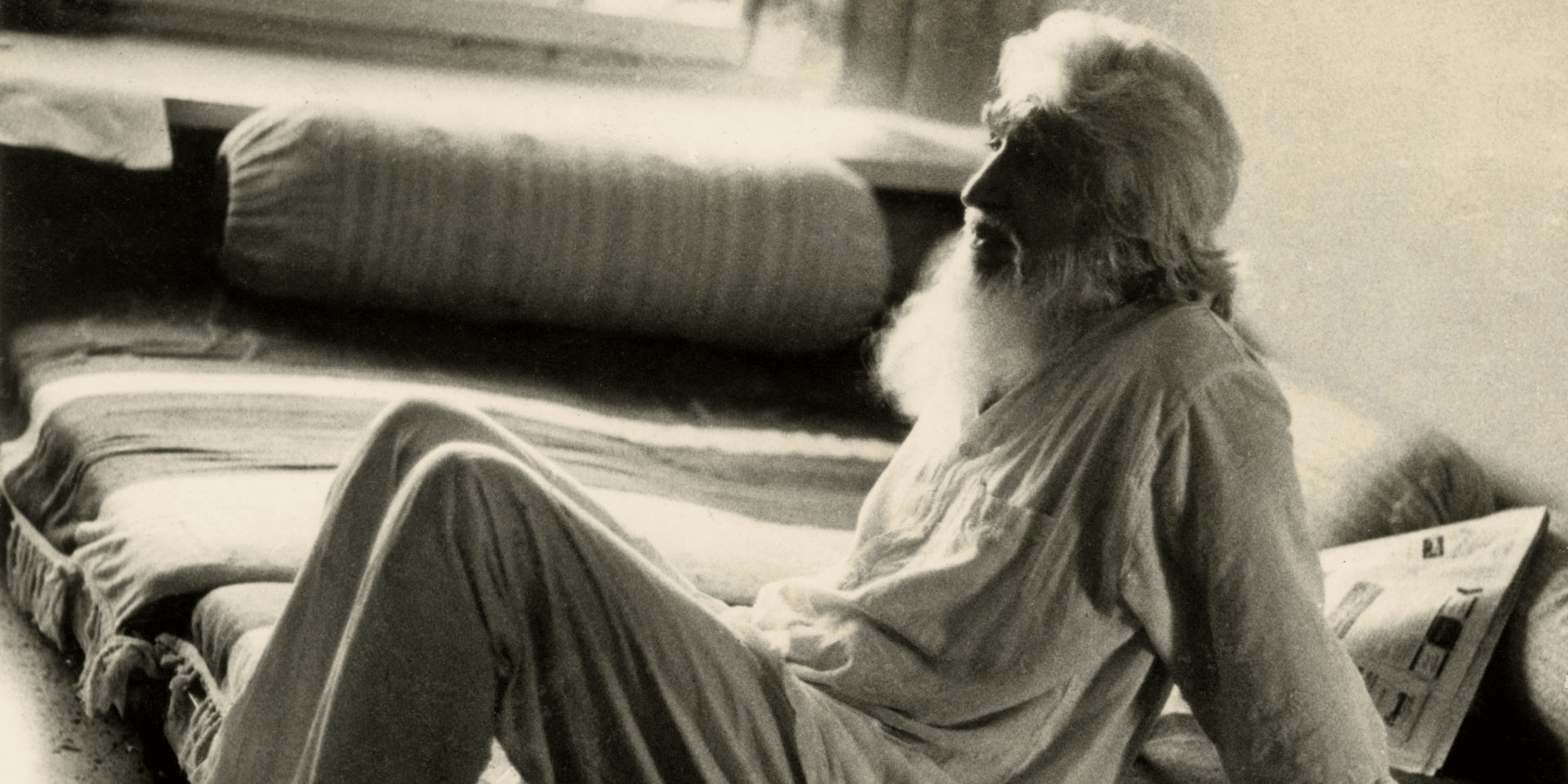

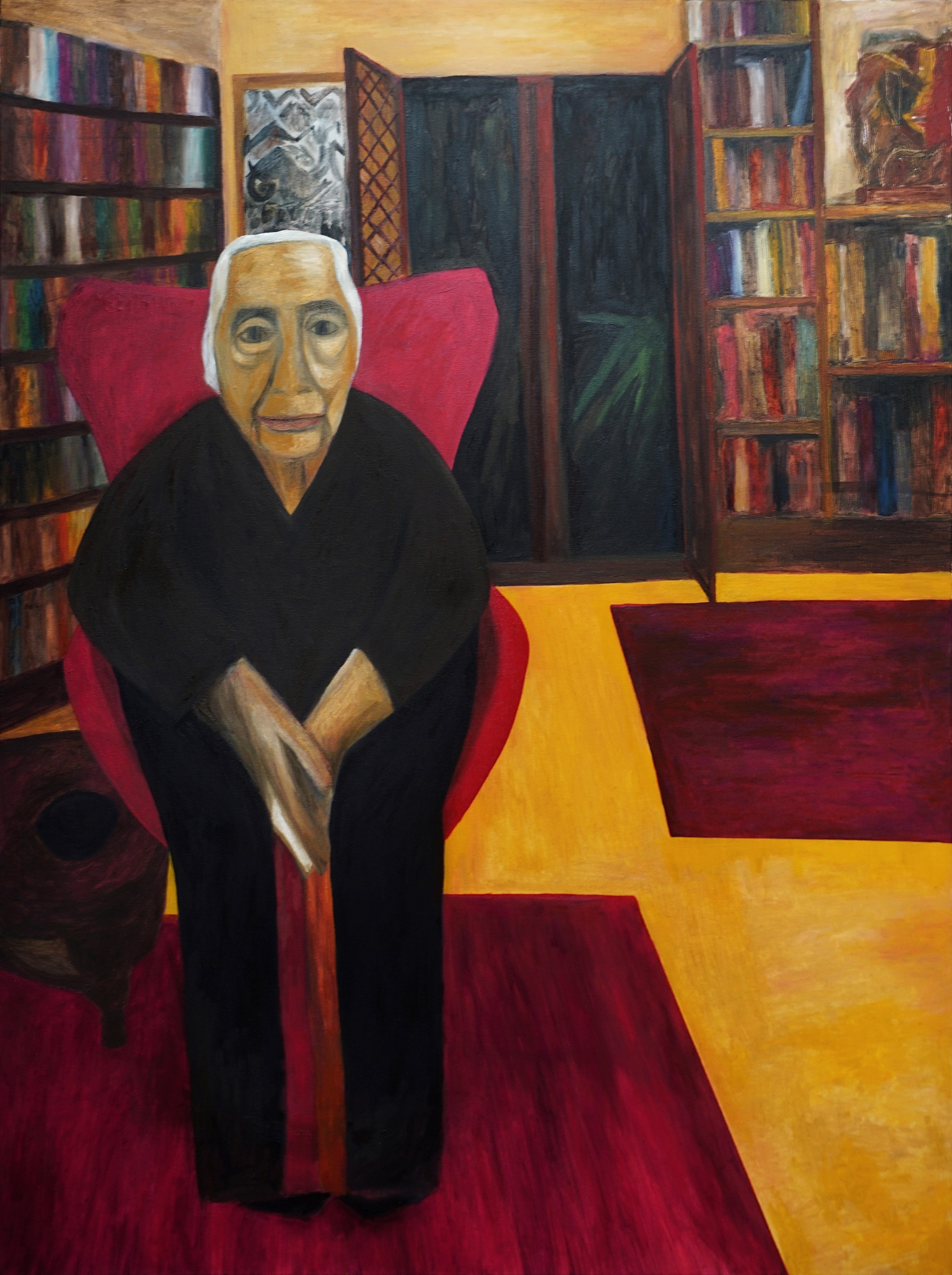

There were occasions when I painted subjects without knowing them personally, such as the portrait of Romila Thapar. While I admired her and was familiar with her work, our connection deepened when she invited a friend and me over for dinner. After an enjoyable evening of conversation, food, and drink, I returned home feeling inspired and promptly started working on that particular painting. On other occasions, I didn't have the luxury of spending extended periods with my subjects, and it was often limited to the duration of a train or bus ride.

Or sometimes, as you sit there, the realization hits you, and you think, ‘I must paint this’. The urge to capture the subtle shifts in the arrangement of bodies, the interplay of negative space, or the presence of a dangling bag—all reflective of the state of public transportation. It's a reflection of the contrast between our pursuit of high-speed rockets and the deteriorating condition of buses and trains. I aspire to do justice to these moments of encounter through my paintings.

|

Aban Raza, Romila Thapar, 2020, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm. Courtesy of Aban Raza and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke. |

Q. There is a recurring use of objects in your painting. How do you decide on using them? Do they have any symbolic value for you, or tell you how to think of the subject of a particular work?

Aban: There are two ways of looking at it. Initially, when exploring printmaking, a still life serves as an ideal subject for experimentation in understanding the technical intricacies of the process. Whether working with a wood board, an etching plate, or a lithography stone, studying a still life provides a platform to translate and apply newfound knowledge. In this context, still life becomes a practical subject, facilitating a comprehensive grasp of the medium.

However, once mastery of the medium is achieved, the meaning attributed to still life evolves. In the case of paintings, everything inherently carries meaning, and rendering is relatively straightforward compared to printmaking. In my printmaking journey, I utilized still life as a tool for learning. Now, when incorporating elements like a wilting flower, it is done with a deliberate intent to convey a specific sentiment or reflect a particular occurrence in the world. I do believe that objects, devoid of human presence or structured compositions, carry significant meaning.

Aban Raza, Singhu Border, Haryana-Delhi, 2021, Oil on canvas, 121.9 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of Aban Raza and Galerie Mirchandani Steinruecke.

Q. You have worked with several art community spaces in Delhi, such as the well-known Garhi Artist Studios and the Delhi College of Art, where you completed your training. How do you think these shared community spaces have influenced your approach to art-making?

Aban: I believe I wouldn't be the person I am today without the enriching experiences of sharing a creative space with numerous individuals. I learned a lot about printmaking from two close friends and peers who are engaged in remarkable work at Garhi. It is a very significant community studio and I think there should be more such spaces. The government, I believe, should establish and subsidize studios like Garhi.

On another note, SAHMAT (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust) has had a profound and lasting impact on me as well. I consider myself fortunate to be associated with them. SAHMAT provides not just me but any artist with a valuable platform to express themselves and pursue their artistic work.