Exchanging Forms: Rathin Mitra on Jamini Roy

Exchanging Forms: Rathin Mitra on Jamini Roy

Exchanging Forms: Rathin Mitra on Jamini Roy

Jamini Roy, House at Jamshedpur (detail), Gouache on cardboard, 13.0 x 16.0 in. Collection: DAG

The radical primacy of form was one of the core tenets that drove the aesthetic sensibilities of the individualistic artists who came together in the wake of the Bengal famine to form the Calcutta Group. In their quest to shape a modernist idiom more closely attuned to the temper of the tumultuous decade of the 1940s, artists like Paritosh Sen, Rathin Mitra and Prodosh Das Gupta encountered in Jamini Roy a true master of form.

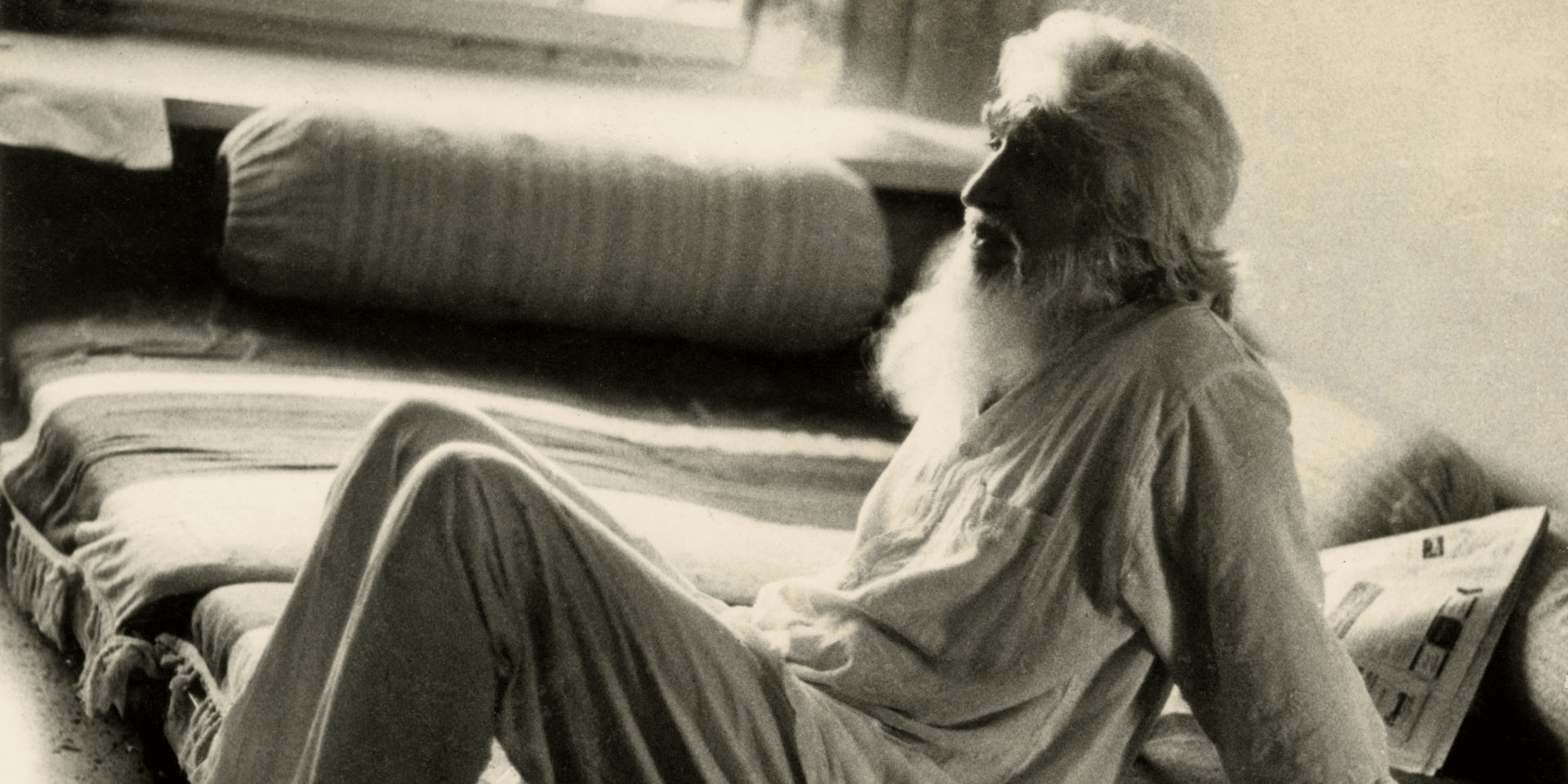

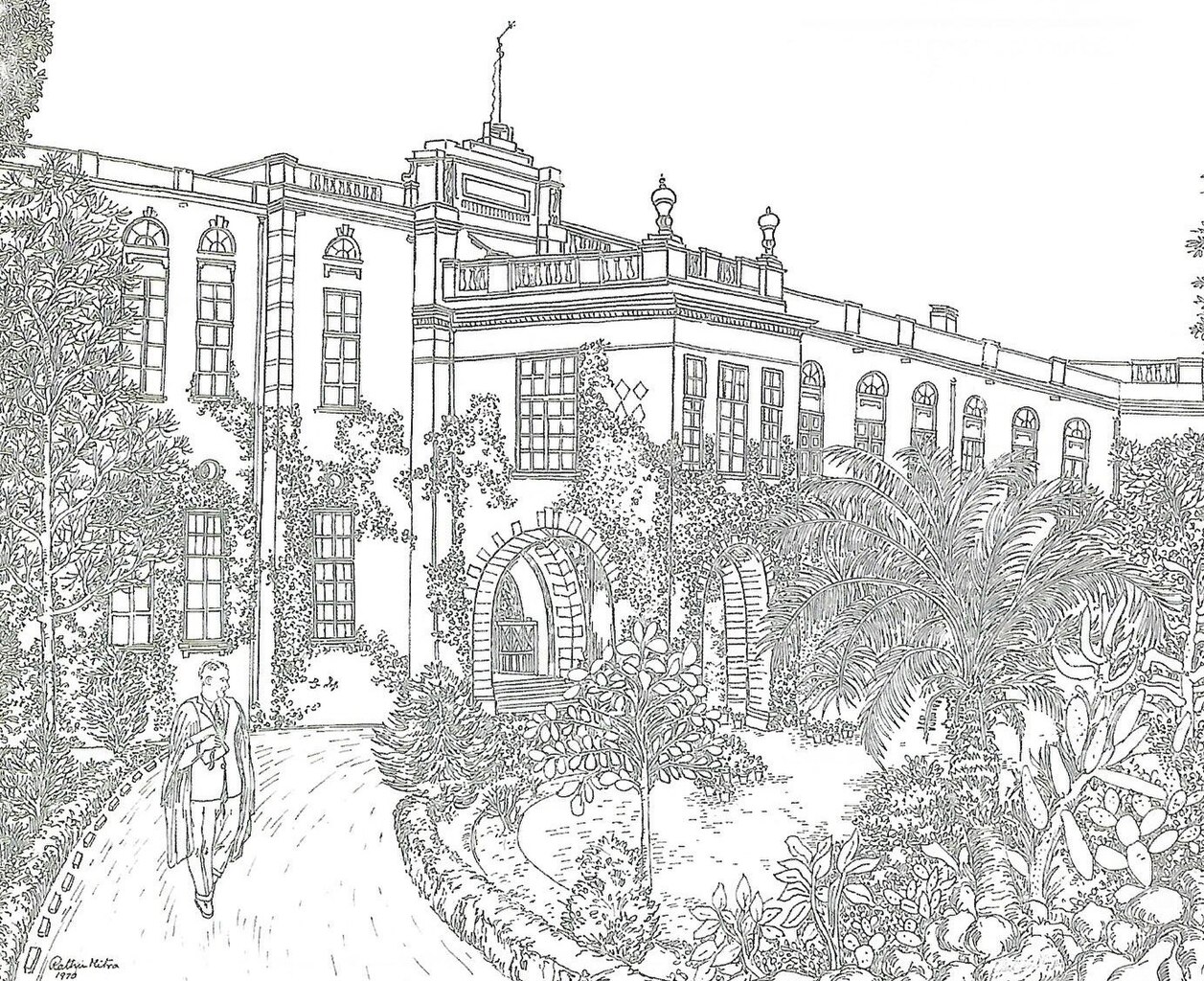

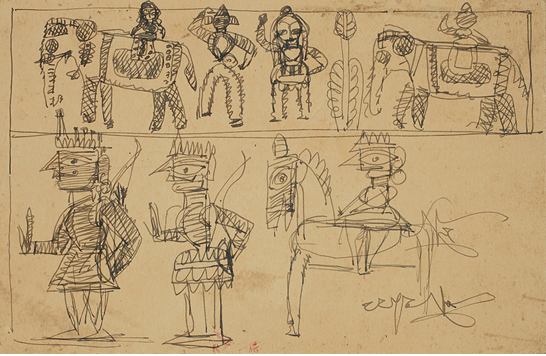

In their writings on the artist who was at the height of his creativity around the time the Calcutta Group emerged, both Sen and Mitra have talked about an oft-overlooked aspect of Jamini Roy’s practice—his sculptures in wood, clay, and stone. For these younger artists, Roy’s minimalist sculptures, carved with a few deft strokes of the chisel, whether from stray pieces of wood or stones found during the construction of the Dihi Sreerampur (sic) house, stood as potent expressions of the artist’s untiring pursuit of form. Mitra, who taught at the Doon School, is perhaps best-known today for his sketches of Kolkata streets and historic landmarks. In the translated excerpt from Mitra’s reflections on his encounters with the master artist that follows, we discern his admiration for a related facet of Jamini Roy’s creative ethos—the unity of form and content. ‘The animating verve of Roy’s lines’, writes Mitra, ‘adds a dimension to his sketches and drawings in a way that never fails to catch the eye. The figures seem poised to escape the unvarying monotony of the paper’s flat surface; and even in the simplest of sketches the compositional elements of a complete artwork is evident. The positioning of the figures within the picture frame is just right, emerging organically to create a perfect balance.’

|

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Terracotta jar, painted and varnished, with a jute base, 22.5 X 15.0 X 15.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Rathin Mitra, Main Building, The Doon School. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

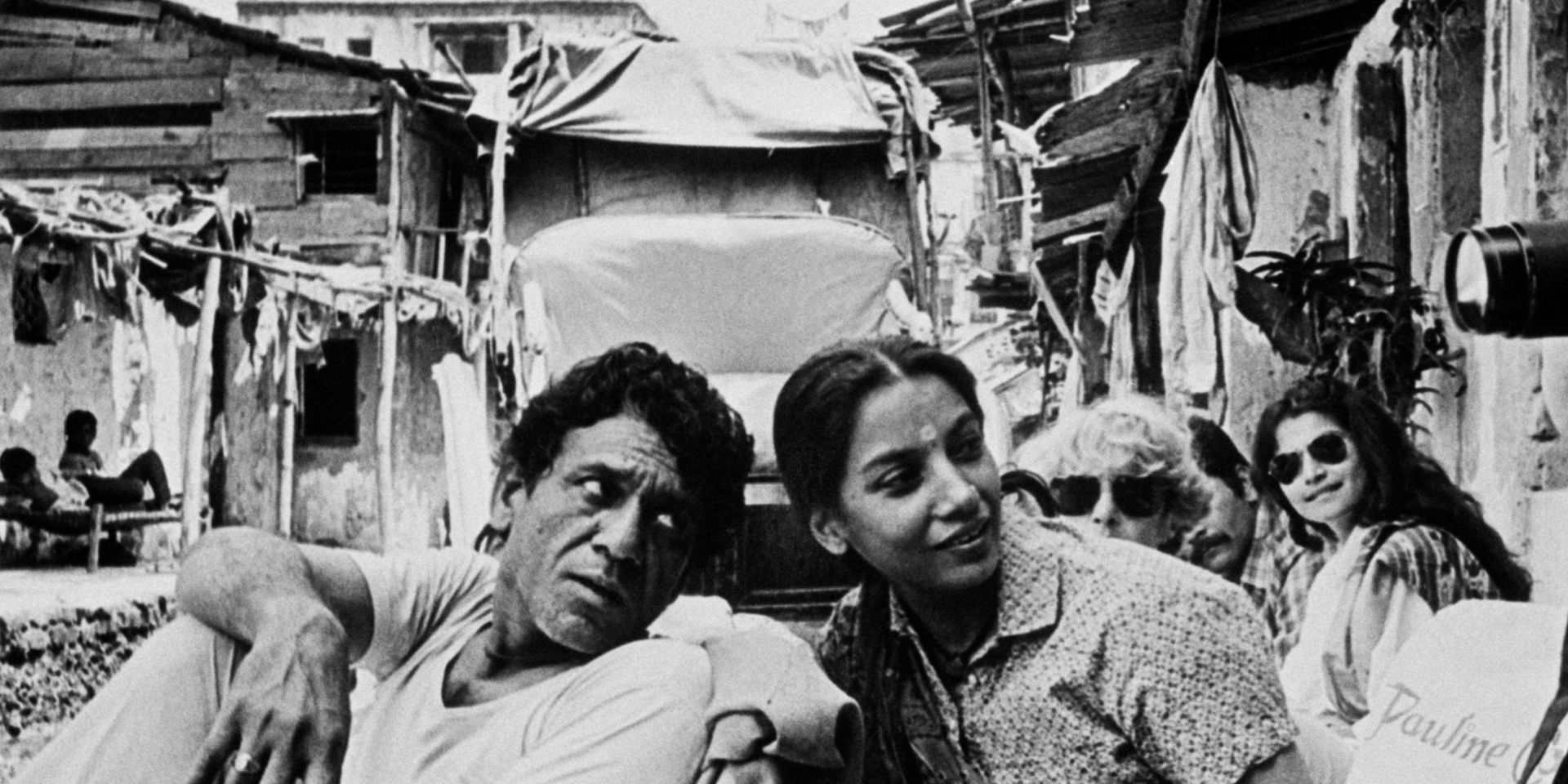

Facilitating an encounter with two visiting Russian artists (from the erstwhile U. S. S. R., which encouraged a social realist style and subject matter), Mitra’s article documents a significant historical moment: when Russian artists sought to exchange aesthetic knowledge with their Indian counterparts, a tradition with its own long lineage—stretching back to the days of travelling artists like Prince Alexei Soltykoff or, Nicholas Roerich, a slightly older contemporary of Roy, who is, like the latter, recognised as a National Treasure artist in India.

|

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Ink on card, 4.7 x 7.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Jamini Roy’s Interpreter

Rathin Mitra

A few Russian artists had come to India in 1958, as part of a cultural and educational exchange programme between our country and the U. S. S. R., and two among them had expressed an interest in visiting Kolkata. They wished to capture the urban fervour of the city streets in their art, and to meet Jamini Roy. The famed studio of this well-known Bengali artist held a different allure for them.

As such, the chief of the Lalit Kala Akademi requested me to plan the daily itinerary of the Russian artists’ stay in Kolkata. I was to put them in contact with Jamini Roy, and to ensure that they have a pleasant trip. I was told that an English-speaking Russian interpreter would be accompanying them.

|

Jamini Roy, Untitled (Two Cats with Prawn) , c. mid-20th century, Tempera on cardboard/ pasted on board, 1.7X 17.2 in. Collection: DAG |

At this time, I was teaching at the Doon school and happened to be in Kolkata for winter holidays, so this opportunity could not have come at a better moment. I readily agreed to play host, and without any further delay met with Jamini Roy to arrange for the impending visit. Jaminibabu requested me to be his interpreter (dovashi), since he, as he characteristically pointed out to me, would be speaking in Bangla. In this context it merits saying that the artist’s lifestyle was ‘authentically’ Bengali, from his poise, his movements, to his manner of dressing, everything bore witness to his rootedness in a graceful time-tested Bangali culture. I was, of course, elated to have been handed such a responsibility, and still remember the visit as if it were yesterday.

|

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Tempera on board, 23.2 X 19.7 in. Collection: DAG |

On the agreed upon time and day, I arrived at Jamini Roy’s house with the artists Punemaro and Trubianka and their interpreters. In the car on our way to the house, the Russian visitors could not contain their excitement and kept asking to know more about how Jamini Roy looked, what sort of a person he was, and so on. They had had some exposure to Roy’s works through displays in galleries abroad, and I soon realised that more than anything it was the artist’s vibrant palette that held a special appeal for them.

To keep alive the intrigue and anticipation I responded to their many curiosities in a somewhat cryptic fashion. I said let us see whether your impressions and images of the artist match up to the person as he really is when you meet him face to face. All I can tell you is that the venerable artist’s personality, and most endearingly his smile, still carries traces of the child-like simplicity that lends such character to his works.

|

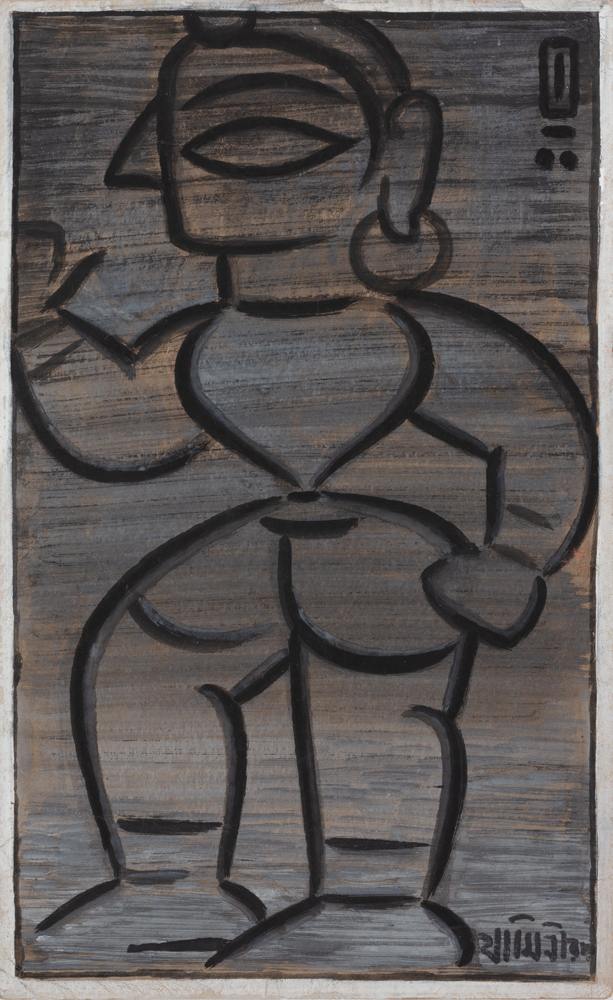

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Gouache on board, 17.7 X 11.0 in. Collection: DAG |

As we were speaking, our car came to a halt a few yards away from the ever-familiar entrance of the Dihi Sreerampur house (or rather the Ballygunj Place house as it is now known). I distinctly remember walking a few steps to reach the gate. We were finally there, right on time, being greeted by none other than the artist himself, who had stepped out into the streets on seeing us. Even before I could introduce them, the two Russian artists put down their briefcases and bowed down to touch Jamini Roy’s feet.

I had not imagined the scene playing out quite this way; it was in keeping with purely Bengali customs that artists from another end of the world had chosen to express their heartfelt reverence for this reclusive Indian artist. I felt moved, and I saw people from some neighbouring houses looking on to witness with us this charming exchange.

Jaminibabu warmly led the Russian guests into his studio-gallery, and we, the two interpreters, followed. While showing Punemaro and Trubianka around the rooms filled with his works, the artist took great care to discuss every last detail. One could see that the dimensions of each artwork had dictated its pride of place and display along the gallery walls. The rest of his works were stored in drawers, which Jaminibabu, with the help of his son and studio assistant Potol [Amiyo Roy, an artist in his own right], brought out for the guests to observe. Surrounded by all this art, the Russians seemed to get deeply immersed in Jamini Roy’s creative universe.

Yet, they seemed surprised at not finding in such a striking body of work any artistic engagement with the urban everyday of a work-weary populace toiling away at factories to hammer out an existence for themselves. Unable to leave their lingering doubt unspoken any longer, the Russian artists expressed the cause for their puzzlement to Jaminibabu.

|

Jamini Roy, Untitled (Boatmen), Tempera on cardboard, 9.7 X 1 9.0 in. Collection: DAG |

In response to their query, the artist began talking about his perception of the core truths of human civilisation, and the quiet significance of such inner realities. He kept citing one instance after another in Bangla to express his ethos, while I tried to cobble together a quick summary of his words in English for the Russian interpreter to render intelligible to the two artists. They in turn were responding with further questions and observations in Russian. Thus, having traversed through an array of translations, the conversation was finding its way back to Jamini Roy in his mother tongue.

I remember him saying that people live in intimate contact with the soil and water that surrounds and nurtures them. While over time, depending on one’s changing surroundings, lives vary in their individual expressions, the deeper concerns of social existence retain a certain unity despite the myriad differences.

Translated by Ayana Bhattacharya

|

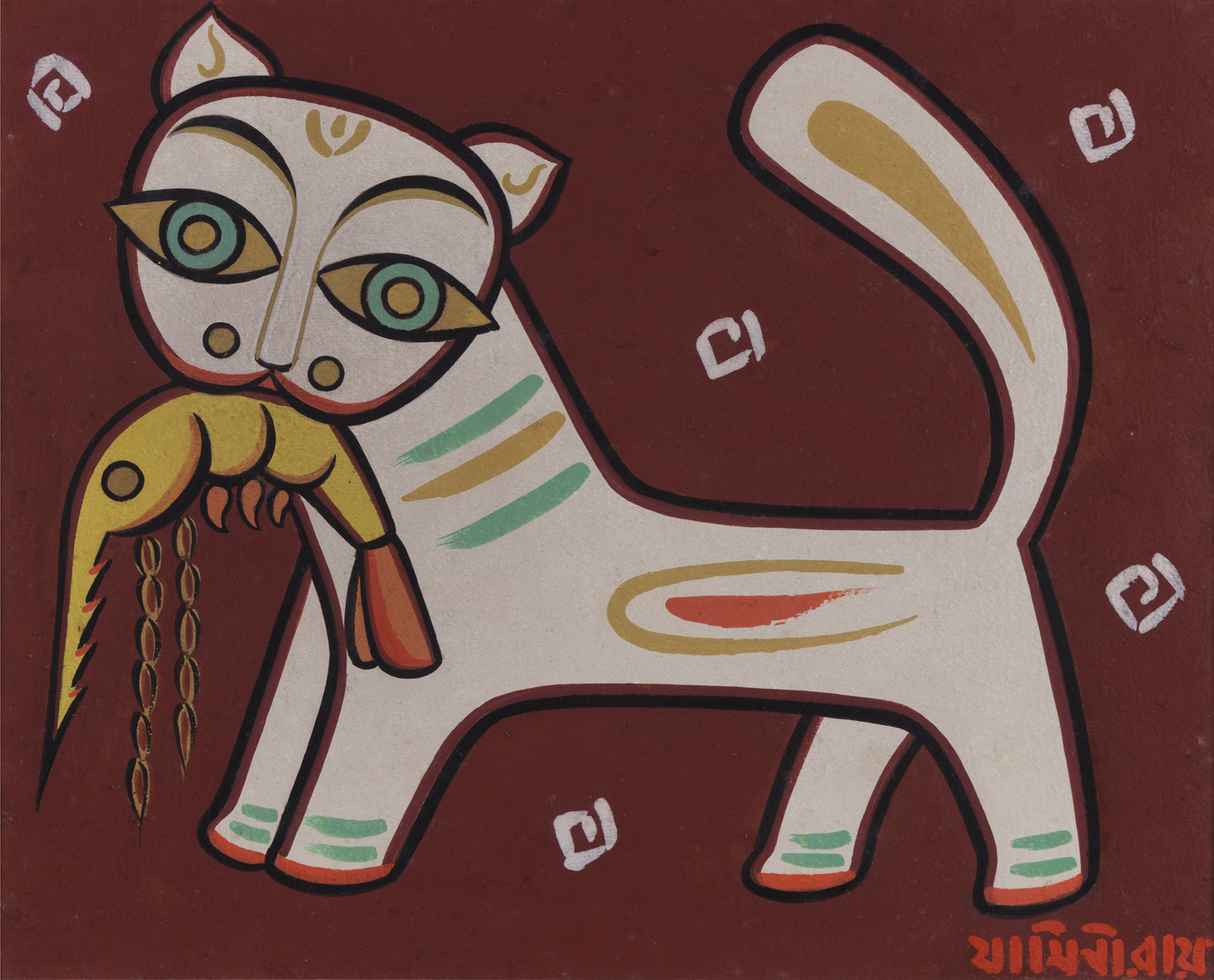

Jamini Roy, Untitled (Cat Holding Prawn), Tempera on cardboard, 14.0 X 17.2 in. Collection: DAG |