Remembering A. Ramachandran

Remembering A. Ramachandran

Remembering A. Ramachandran

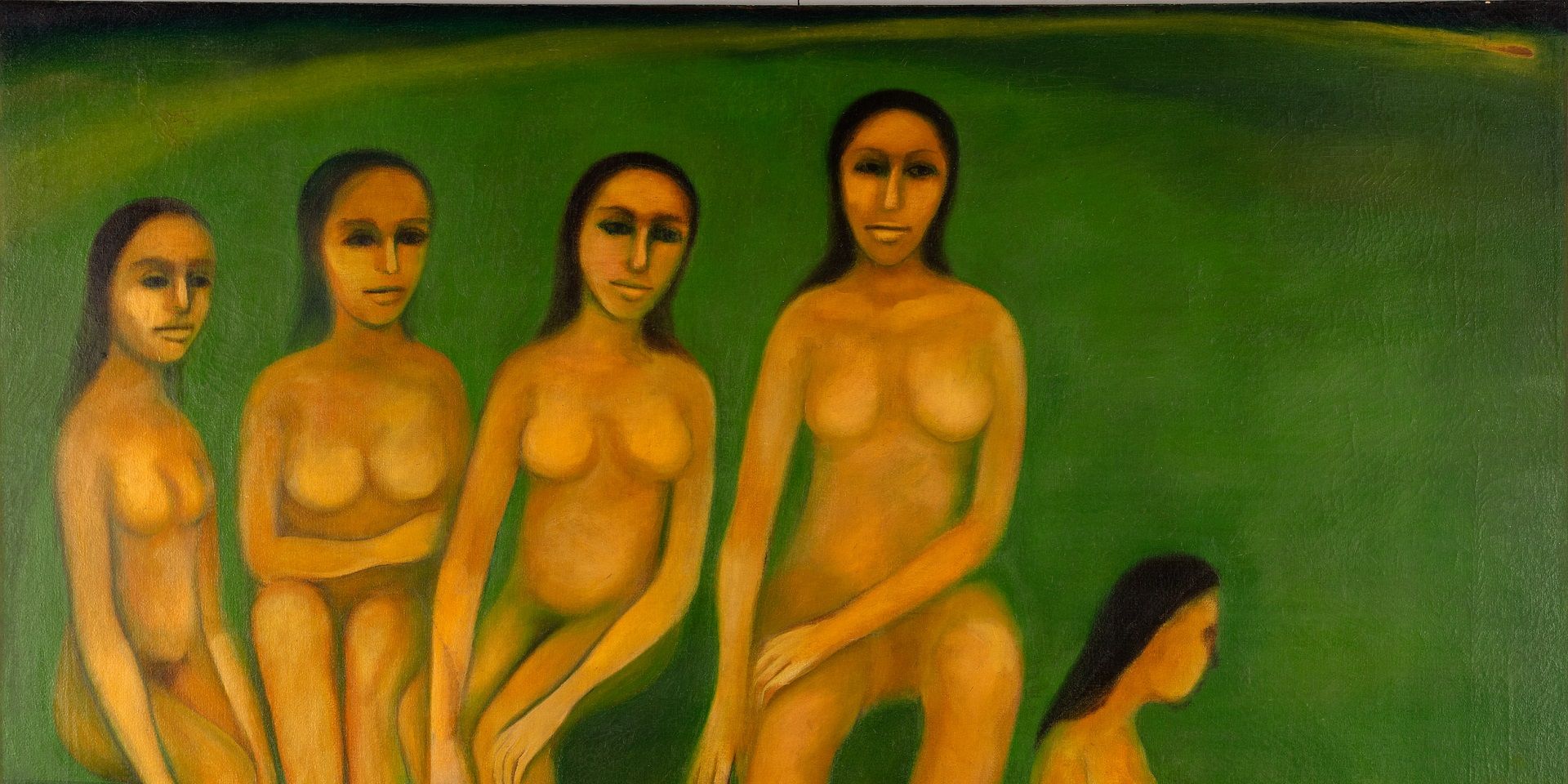

A. Ramachandran, Gestures (Triptych) , 1966, 50.2 x 100.5 in. Collection: DAG

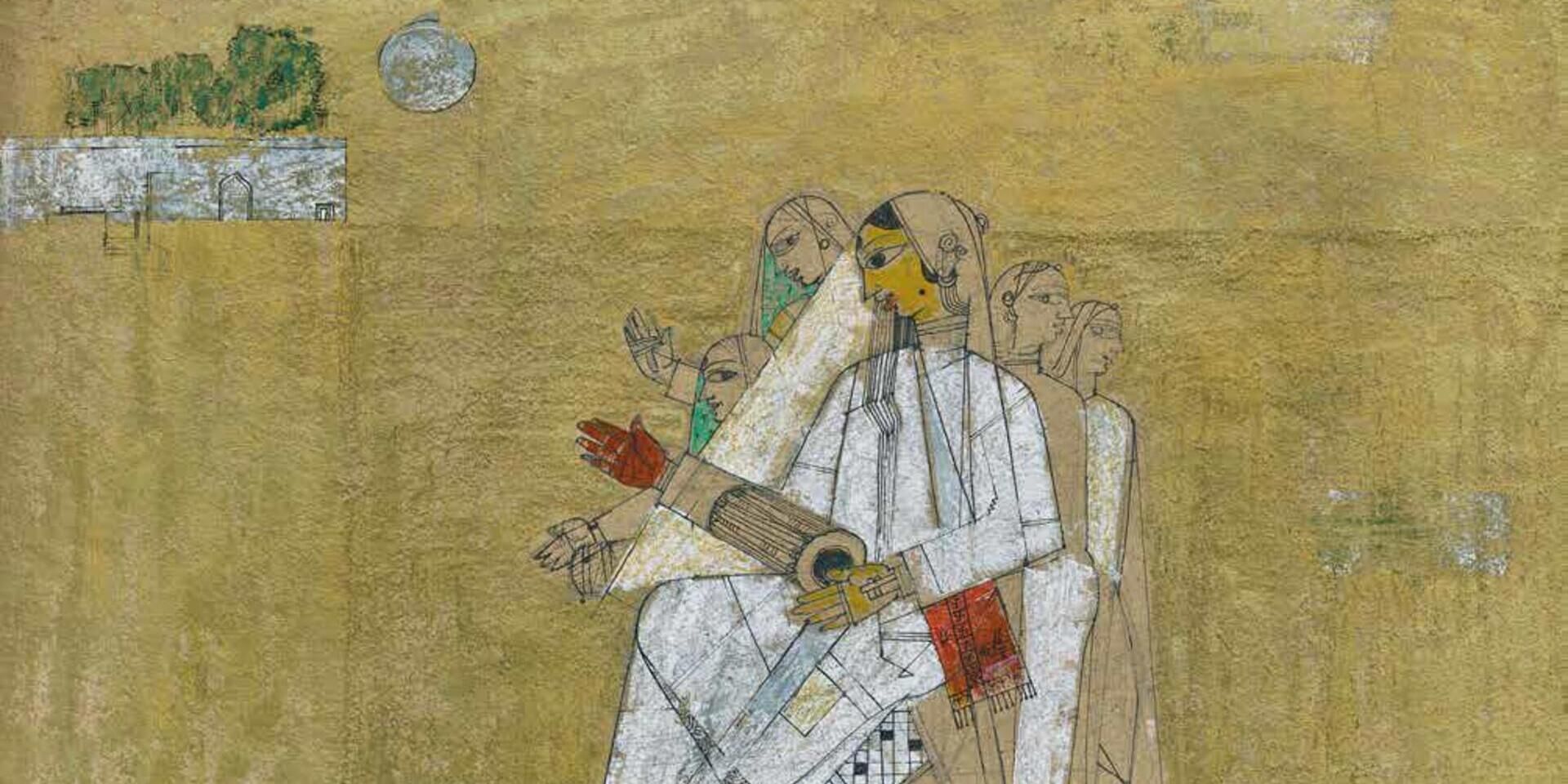

Lotus Eater from Kerala

Catching up with A. Ramachandran (1935—2024) at the opening of his retrospective at Mumbai’s National Gallery of Modern Art in 2019 was a special treat because the artist had stopped leaving his studio in Delhi’s Bharti Nagar some years earlier. His health was indifferent, his knees troubled him, so he avoided stepping out for even the openings of his favourite artists and studios, concentrating, instead, on continuing to paint against the challenges of his gradually failing eyesight. He’d given up reading some years earlier, but he was still stimulated by a good conversation, was still excoriating about critics and their lack of understanding of Indian aesthetics, and he could still overwhelm you with his wit with words as well as paint.

|

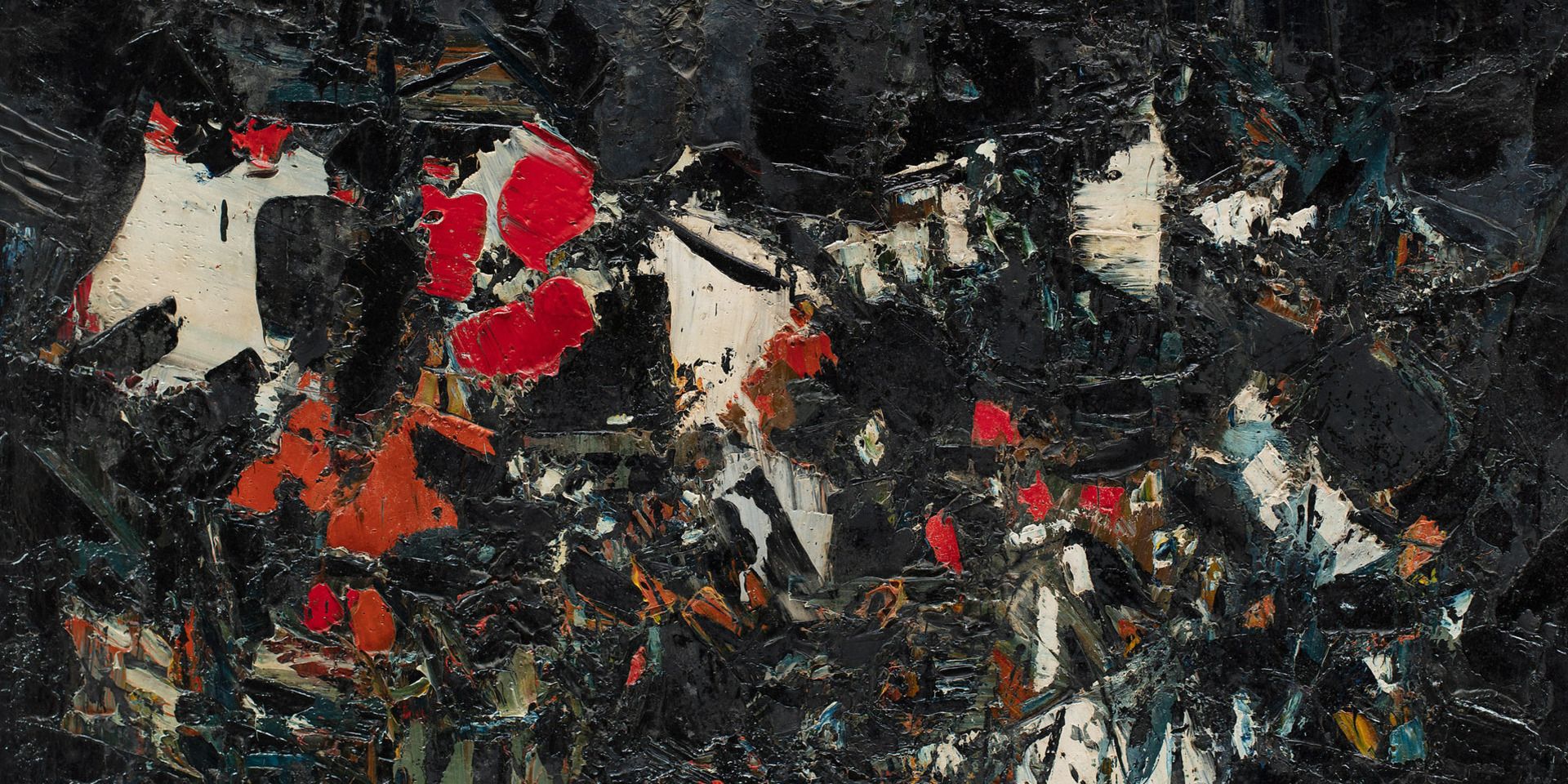

A. Ramachandran, Kaleidoscope, 1966, Oil on canvas, 45.2 x 51.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Ramachandran was no stranger in Delhi—you could arrive at his doorstep simply by calling him on his hand phone—but the retrospective was a treat with his late career monumental paintings as well as the largest body of his sculptures that were being shown on the occasion. The retrospective had been curated by R. Siva Kumar, a great admirer and exponent of his work who understood the epiphany that had caused the artist to change direction mid-career, and whose books had done much for our understanding of the demons that drove Ramachandran to change course as a modernist with an enviable reputation.

|

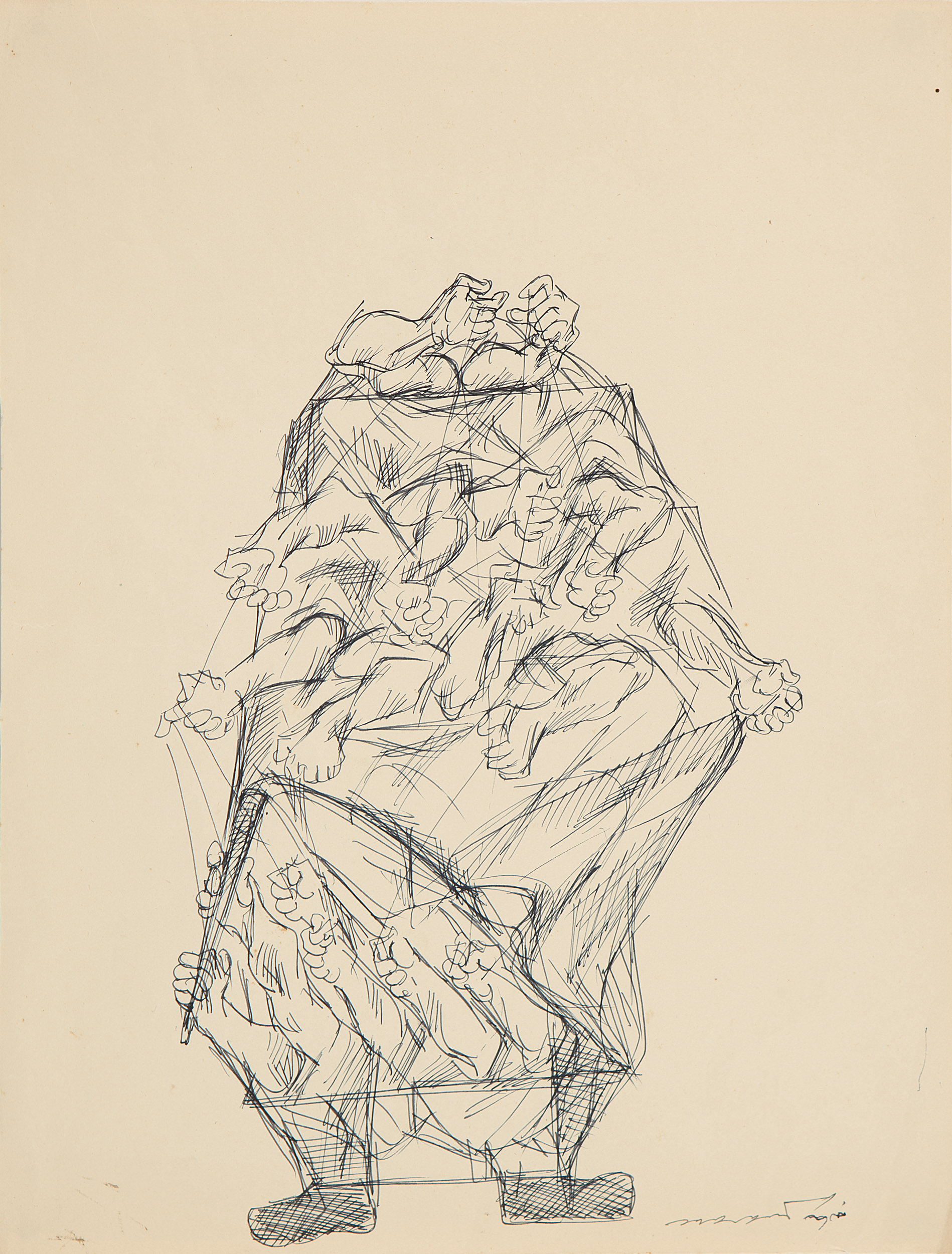

A. Ramachandran, Untitled, Ink on paper, 15.0 x 11.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Ramachandran received his early education in Kerala where he studied music and Malayalam literature. He arrived in Santiniketan with a desire to train under the sculptor, Ramkinkar Baij, and went on to study for his Ph.D in murals, eventually relocating to New Delhi where he joined the Jamia Millia Islamia University as an art teacher and forged a brilliant career with his sensorial paintings on the human condition. All this was to change with the Pokharan nuclear blast of 1974 that got him to question imminent human annihilation and what followed was his Nuclear Ragini series that explored the local aesthetic tradition for the first time. This was followed by his Yayati series on the legend of the king who asked for his son’s youth, so he might continue to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh.

|

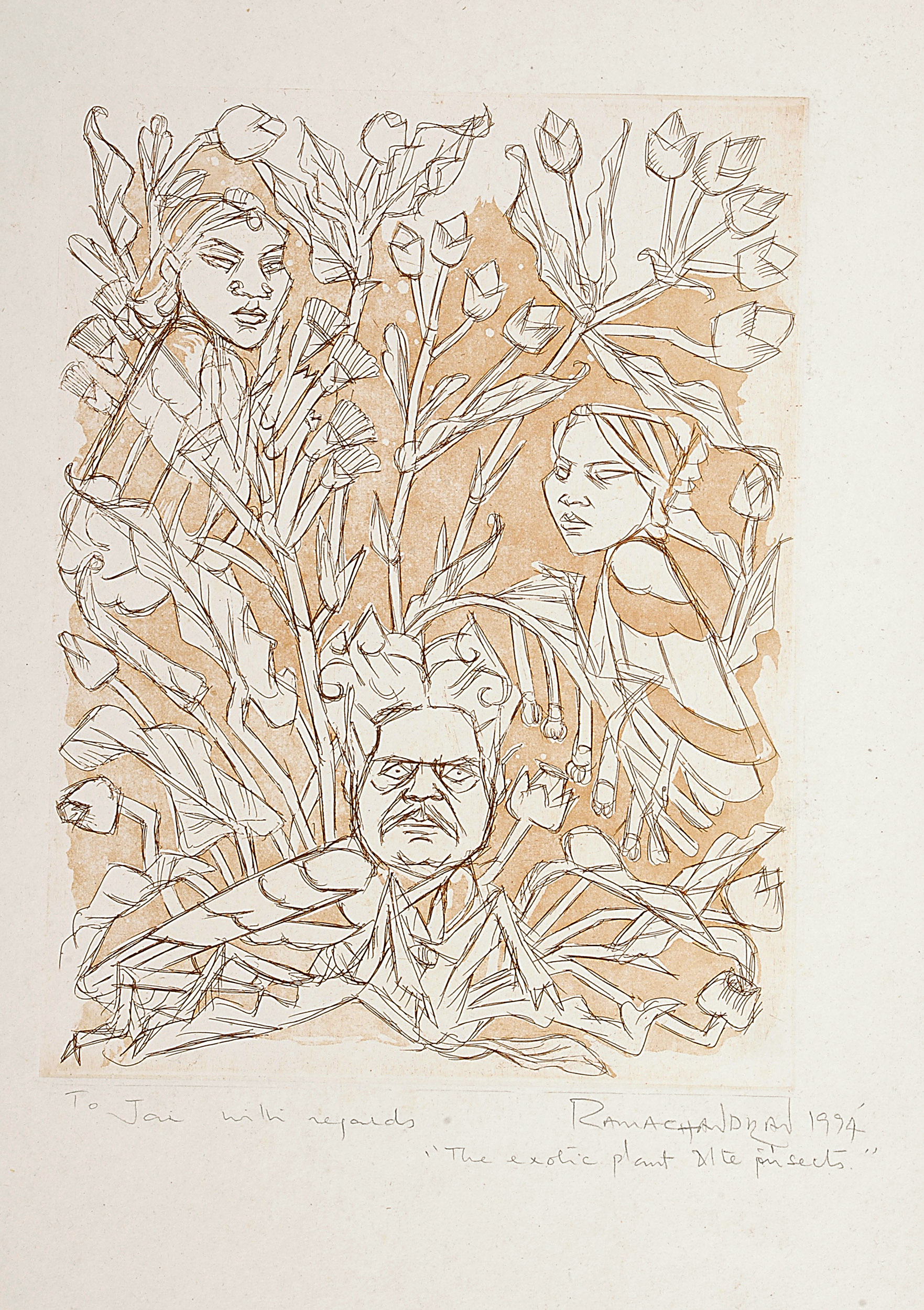

A. Ramachandran, The Exotic Plant & the Insects, 1994, Etching and aquatint on paper, 12.7 X 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

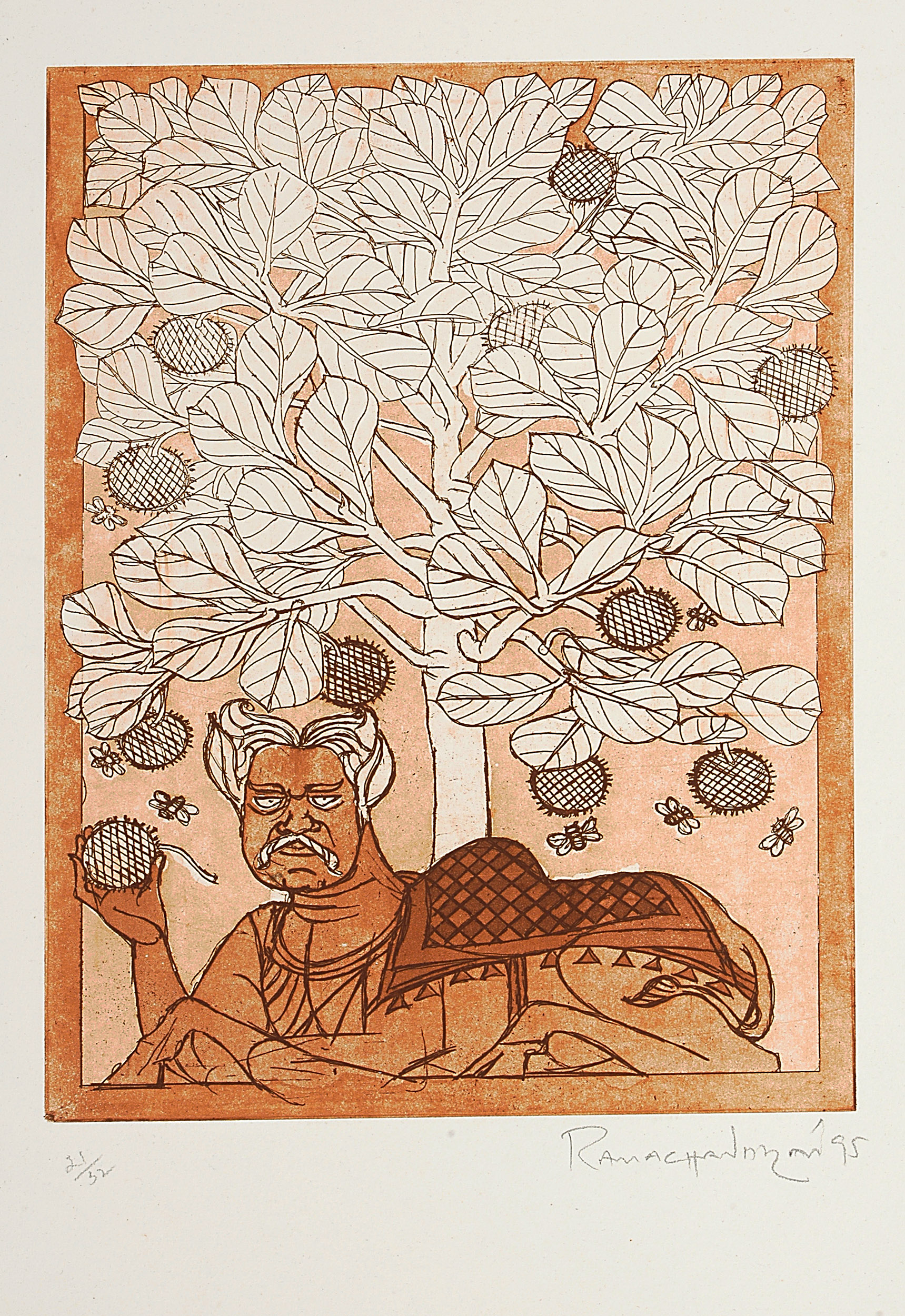

But what Ramachandran is most likely to be remembered for are his panoramas of the lotus pools outside Udaipur that he chanced upon, their imagery holding him captive for the rest of his life. Within the giant leaves of the lotus ponds, amidst kingfishers and dragonflies, he wittily inserted himself as a fish or a turtle, while painting the beauty of the tribal women who lived in their vicinity. The turnaround was panned by critics but loved by collectors and demand for his work soared. Till the end of his life, he remained dismayed that art writers remained ignorant of subcontinental aesthetic traditions and viewed Indian art only through a Western lens.

|

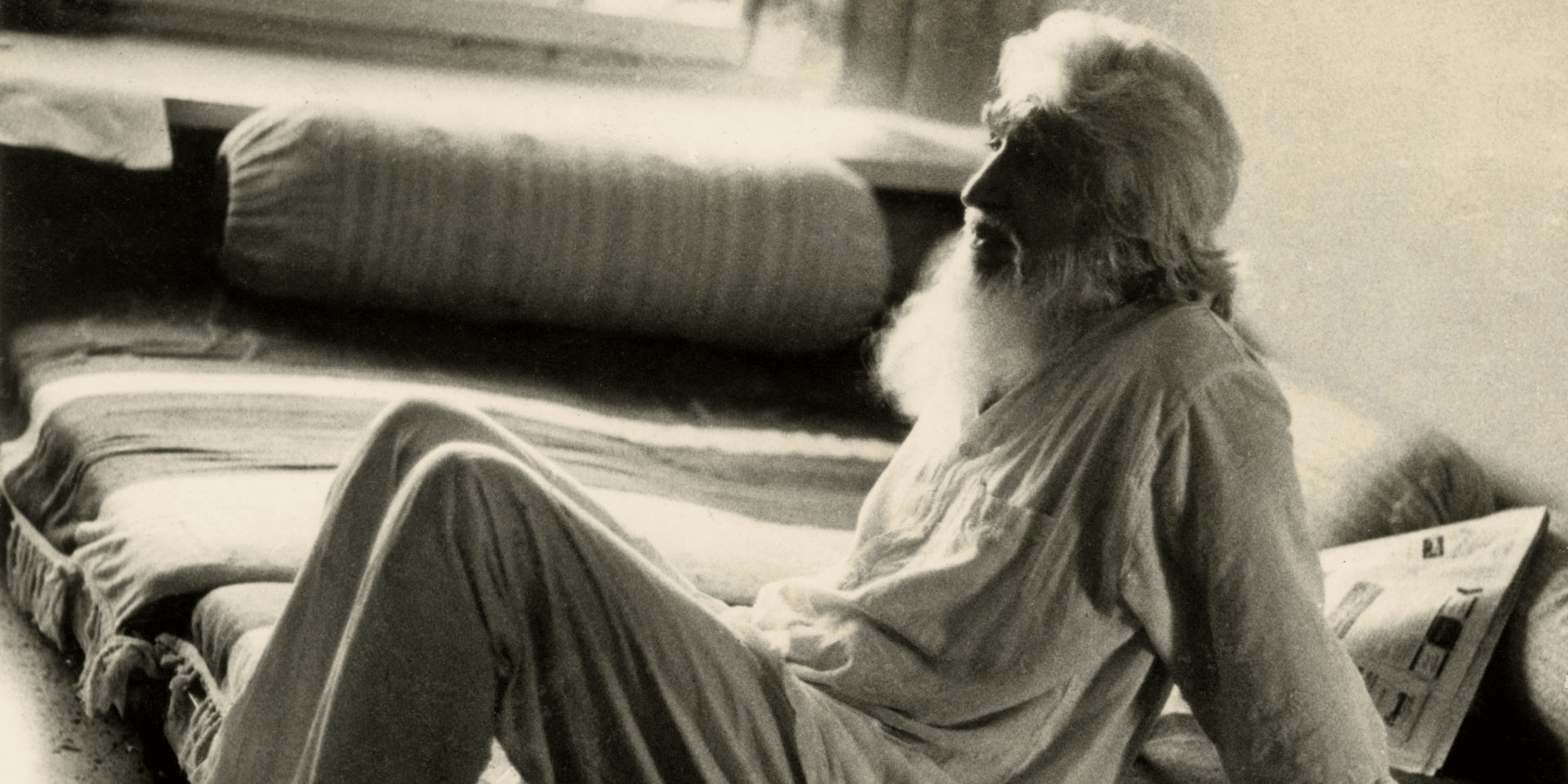

A. Ramachandran |

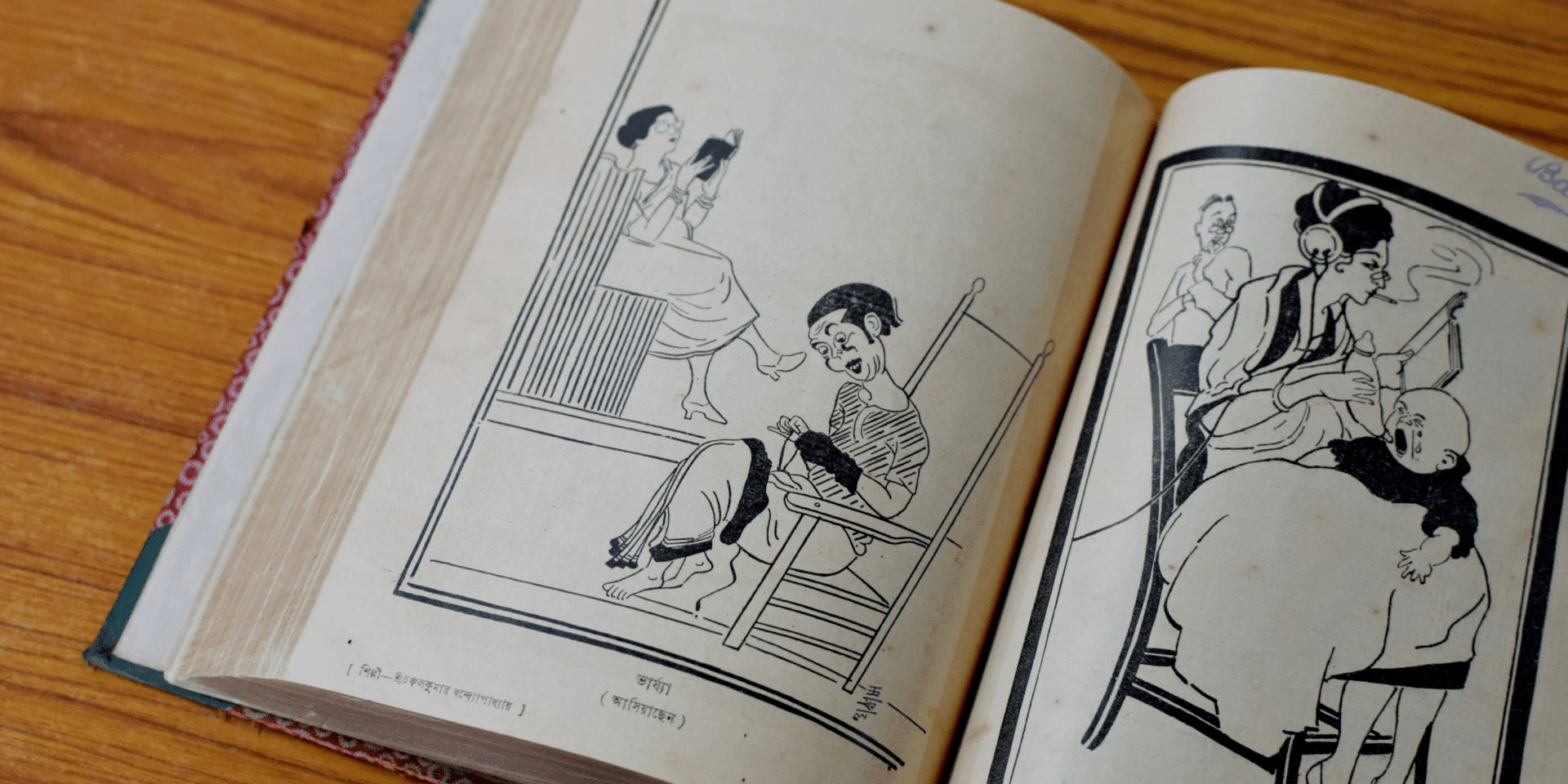

Throughout his career, Ramachandran illustrated hundreds of children’s books, and curated a groundbreaking exhibition on Raja Ravi Varma. His Santiniketan years and his own collecting had made him an authority on Santiniketan as well as some Bengal artists and he was happy to share his knowledge with scholars and writers, keeping the ‘teacher’ in him alive long after he had given up teaching art. His students he often advised not to take art too ‘seriously’, perhaps as a nod to his own disparaging humour, writing self-deprecatingly about himself in a book that included autobiographical as well as pieces of fiction.

|

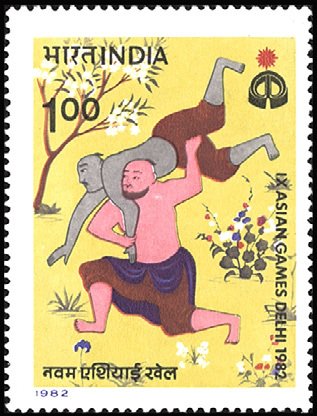

Indian postal stamp designed by A. Ramachandran on the occasion of the 9th Asian Games, held at New Delhi in 1982. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Some months ago, his doctor had told him that he was a short step away from blindness, something that caused him immense sadness. It is what we spoke about when we last met at his studio. Even then, his sense of humour did not abandon him. As a departing present, he pulled out a pen to draw me a self-portrait of an artist surrounded by gigantic lotus leaves that he proceeded to title Lotus Eater from Kerala. Far from being a lotus eater, Ramachandran was a lotus lover who taught us all to fall in love with his lotuses and the lotus people of Eklinji.

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Intersections

The Painters’ Camera: Husain and Mehta's Moving Images

Avijit Mukul Kishore

February 01, 2023