An Elsewhere Homeland: Sayed Haider Raza’s Iconic Masterpiece

An Elsewhere Homeland: Sayed Haider Raza’s Iconic Masterpiece

An Elsewhere Homeland: Sayed Haider Raza’s Iconic Masterpiece

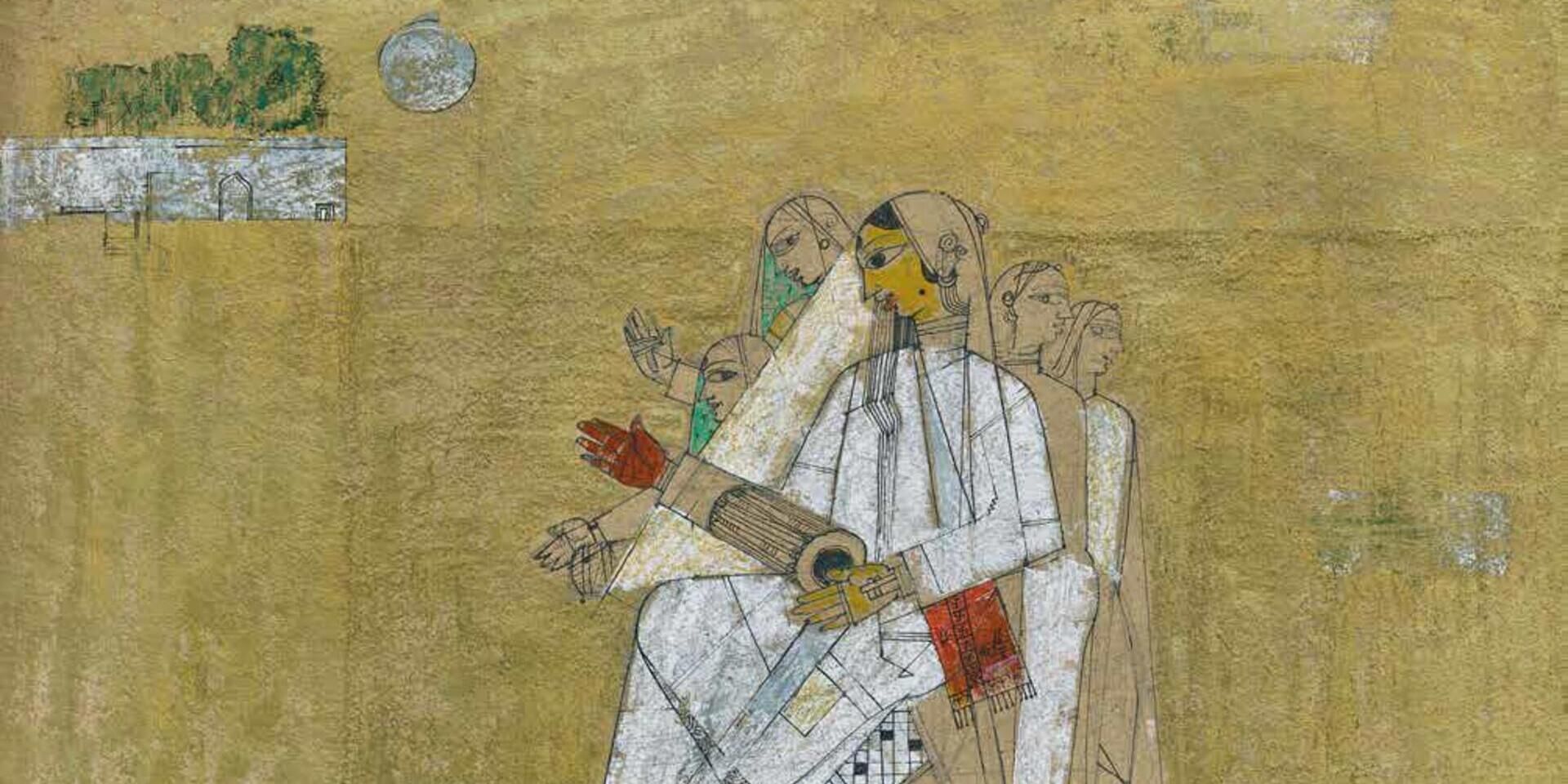

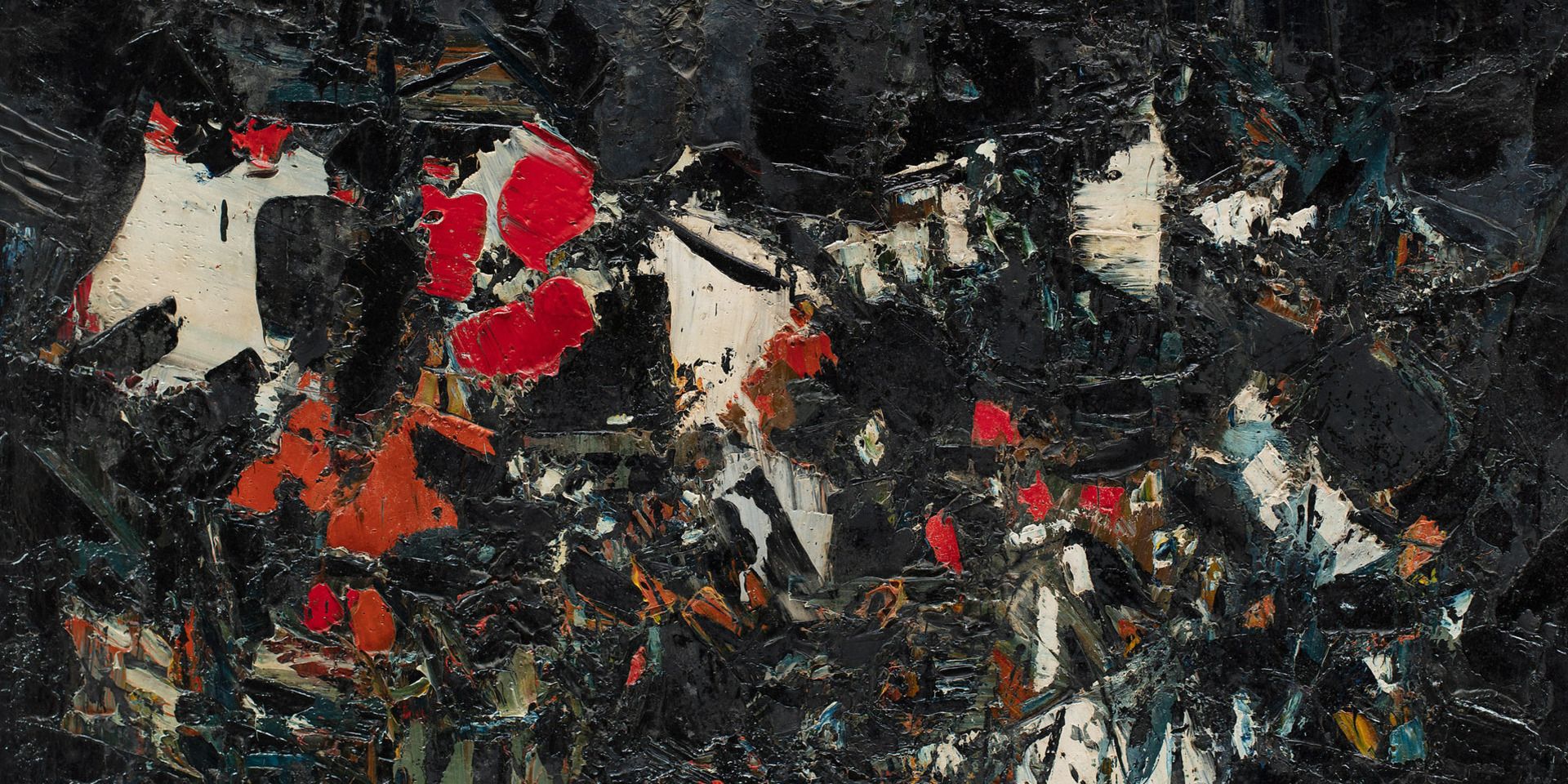

S. H. Raza (1922-2016), Zamine (detail), Oil on canvas, 1960, 38.5 x 31.5 in. / 97.8 x 80.0 cm. Collection: DAG

‘Raza was in some ways an earth painter—someone to whom earth mattered both as a constant presence and an irrepressible memory.’ Ashok Vajpeyi looks at the natural mechanics of Raza’s abstractions, tracing his relationship with landscape and art.

Nature remained, for S. H. Raza, a lifelong preoccupation. For him, it was an inexhaustible source and metaphor for life itself. In many ways, aesthetic and esthetical, nature was life itself in its beauty, grandeur, subtlety, and complexity, its richness and abiding enchantment. He first explored nature as landscape art, including human presence and the visual existence of manmade objects such as buildings, temples, churches, pathways, gatherings et cetera. Later, the exploration moved on to the five elements, which in classical Indian thought constitutes nature—indeed, the whole existence. These elements are: earth, water, fire, sky, and wind.

The first of these, ‘earth’ came to occupy Raza’s attention for long and he painted it in several different ways. For him, earth was a reminder of his homeland, her jungles and riverbeds; an earth which had the sacred river Narmada, and whose dust he always touched and put on his forehead as a mark of respect and gratitude whenever he visited Mandla, the town where he spent his childhood and where he finally rests in a grave. For him, earth remained an eternal source of plenitude and beauty, mystery and complexity, fear and possibility. Raza did paint the five elements, mostly together. But for him earth also contained in its vast richness both water and fire, two other elements. He would have felt close to these lines of his favorite poet Rainer Maria Rilke:

We have been here once, even if only once;

To have been earthly: who can revoke that?

Raza was in some ways an earth painter—someone to whom earth mattered both as a constant presence and an irrepressible memory. In him, again as Rilke asserted, earth rose in its immensity and occupied a large space in his aesthetic and reflection imagination. He was aware that we are all on this earth for a brief period, and as a Muslim he also knew that one day he would find a lasting, and last, place in this earth only. He delighted in being on it, imagining and painting it, living on it.

|

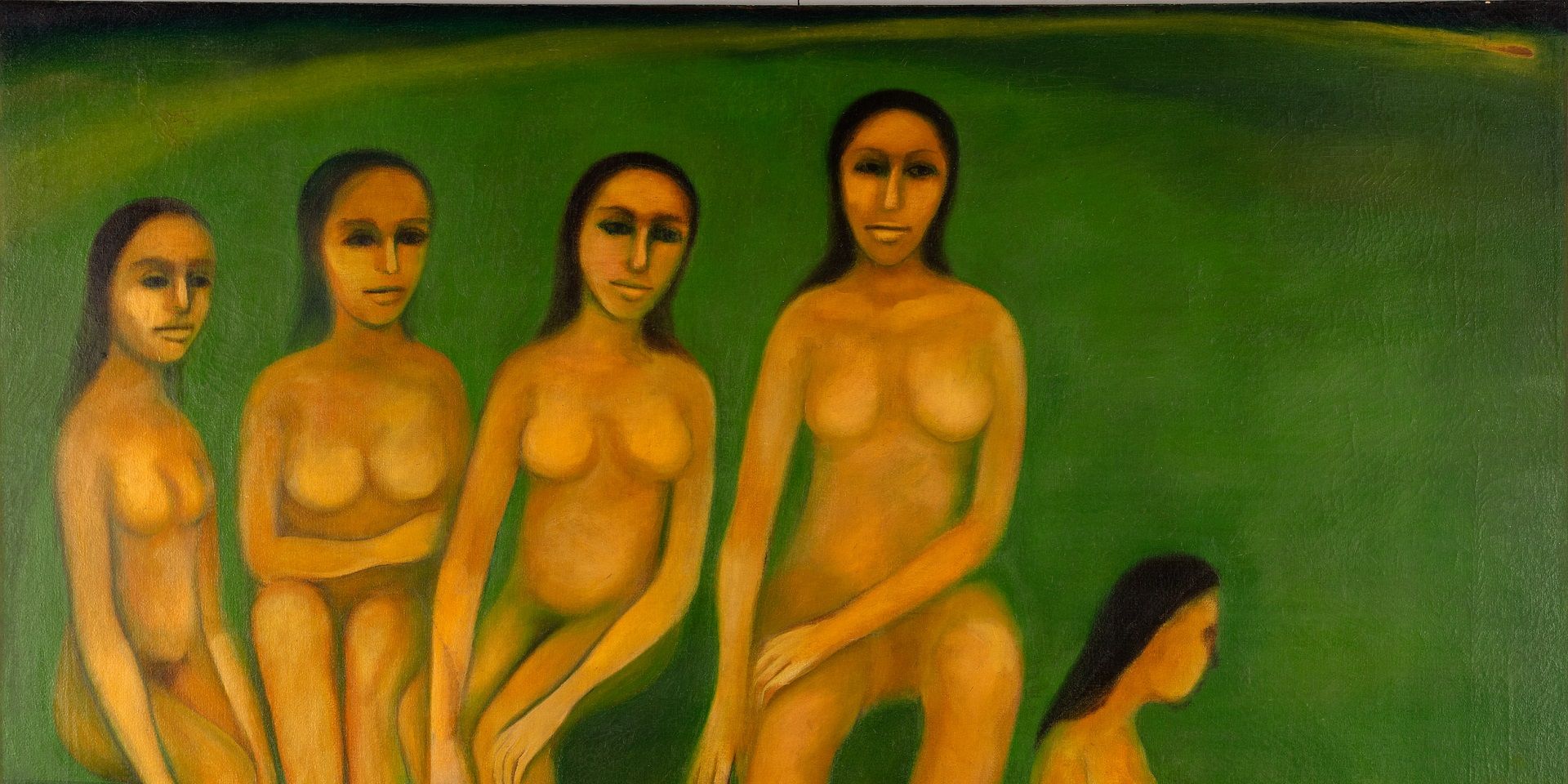

S. H. Raza (1922-2016), La Berge (The Riverbank) , Oil on canvas, 15.7 x 12.7 in./39.9 x 32.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

In 1960, Raza had already spent a decade in Paris, recognised as an award-winning member of the Ecole de’ Paris, still working in oil and carrying on his own convention of landscape painting, pushing it towards more and more abstraction. While he had been painting a number of churches and villages, travelling across France, and many cityscapes, his memories of mother earth had not subsided. In fact, they never did. Zamine marks this moment when earth rose in him again, as Rilke had put it: Earth, isn’t this what you want: to arise in us invisibly? Isn’t it your dream to be invisible someday? Earth? Invisible?

The painting has an intensely dark background—solid and strong. Yet, there are numerous marks on it, most of them barely visible. There is a well-balanced contrast between thin visibility and full visibility suggesting that, in art, as on earth, there is always interplay between the two. Art may make some things, some aspects of reality, emotion and experience, visible, but it also acknowledges that a lot is left necessarily invisible. In a sense art hardly ever, if never, makes full revelations. It does not hide, avoid or conceal the vastness of reality but, in humility, reveals that it just cannot cover the whole. In that sense, vis-à-vis nature, in respect of its exploration of earth, art can never be perfect. Its imperfection, in this context, is not a weakness or infirmity but an inevitable limit to human artifice.

|

S. H. Raza (1922-2016), Zamine , Oil on canvas, 1960, 38.5 x 31.5 in. / 97.8 x 80.0 cm. Collection: DAG |

The invisible or the barely visible in this painting seem to invoke the vast number of things the earth may wear on its body—hills, rocks, trees, houses et cetera. Raza was also a painter of the nocturnal, having painted the night, its darkness, quite often. This painting, too, has a nocturnal ambience. It is like trying to unravel the earth in the night. The night with its own lights, flames, and darkness; also, light patches surrounded by darkness, in darkness. It is as if Raza remembered and recreated an alaav, a rural community setting in India where people sit around a pile of wood: burning, smoking, alight. There are no people in the painting; it is as if the painting silently misses and mourns their absence, Raza had much later painted the words by Mahatma Gandhi: ‘Amidst darkness, light persists.’ This persistence saves, as it were, the work from dark despair. The earth, Raza knew too well, is not caught in the human binary of hope and despair, light and darkness; the earth contains, holds, emanates them all. One can interpret the work in another way, getting rid of the ‘aboutness of art’ syndrome. The painting is iconic and its being so does not depend on its being about something. It is an icon in itself, a work of art fully autonomous, allowing you the full freedom to receive and respond to it the way you like. A visually alert and intelligent viewer would know the stated themes as embodied in titles of artworks are not necessarily binding on its meaning and significance. There are artists, and major ones at that, who like to make art to state a viewpoint, to work out an idea, to represent a certain vision. But Raza, surely, was not one of them. He had his own vision and ideas about life, nature, and art, but he did not make his art the carrier of these burdens. He allowed art its freedom and autonomy; he also believed that art itself generates ideas, and that all ideas that are relevant to art are not born outside the realm of art to be imported from elsewhere.

An iconic work is deeply rooted in the vision and skill of the artist but it is also the intimation of an elsewhere. It creates, in the final analysis, its own earth and ground, its own sky and fire, its own inalienable homeland. It arrives. It is elsewhere.

|

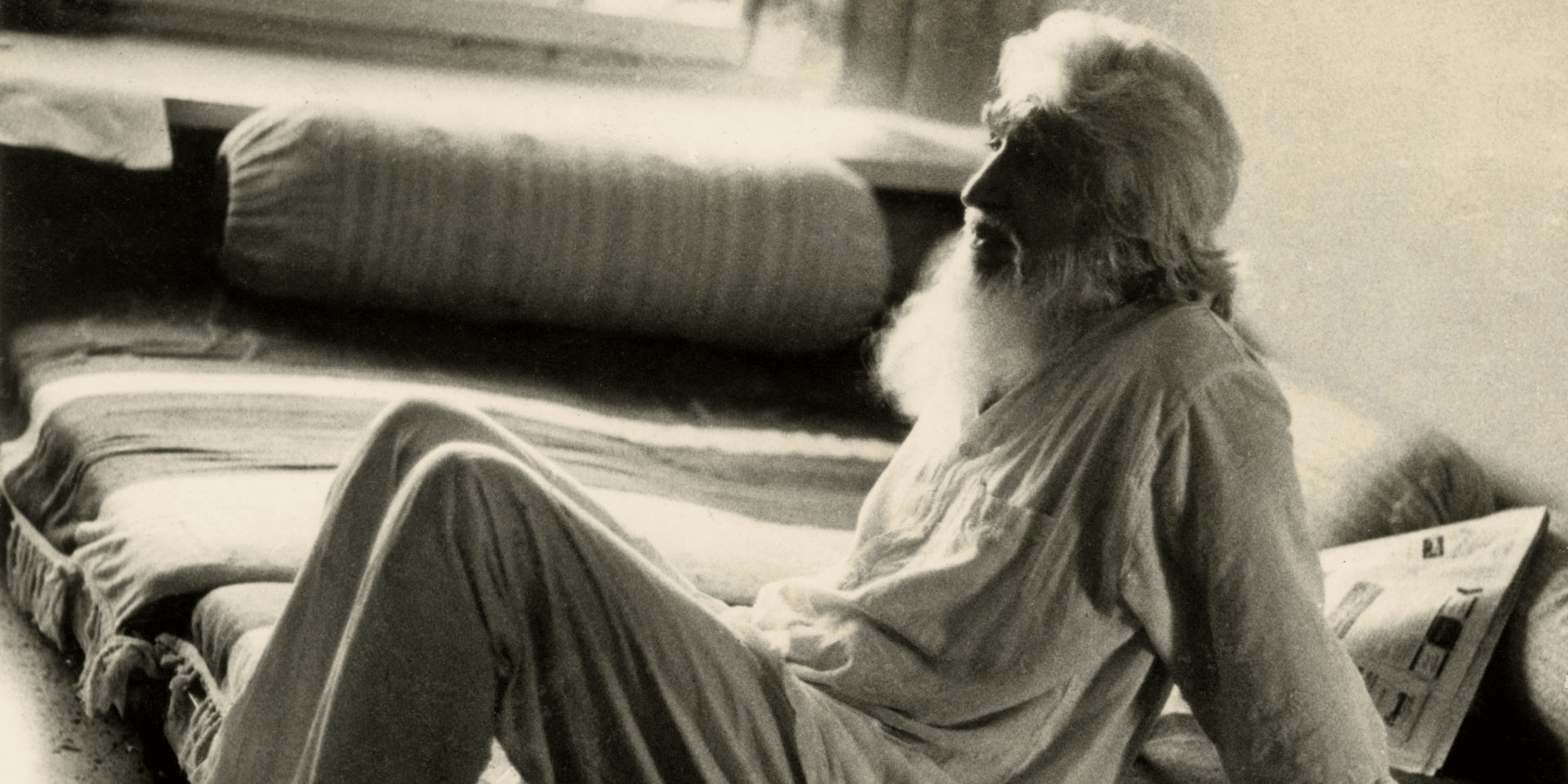

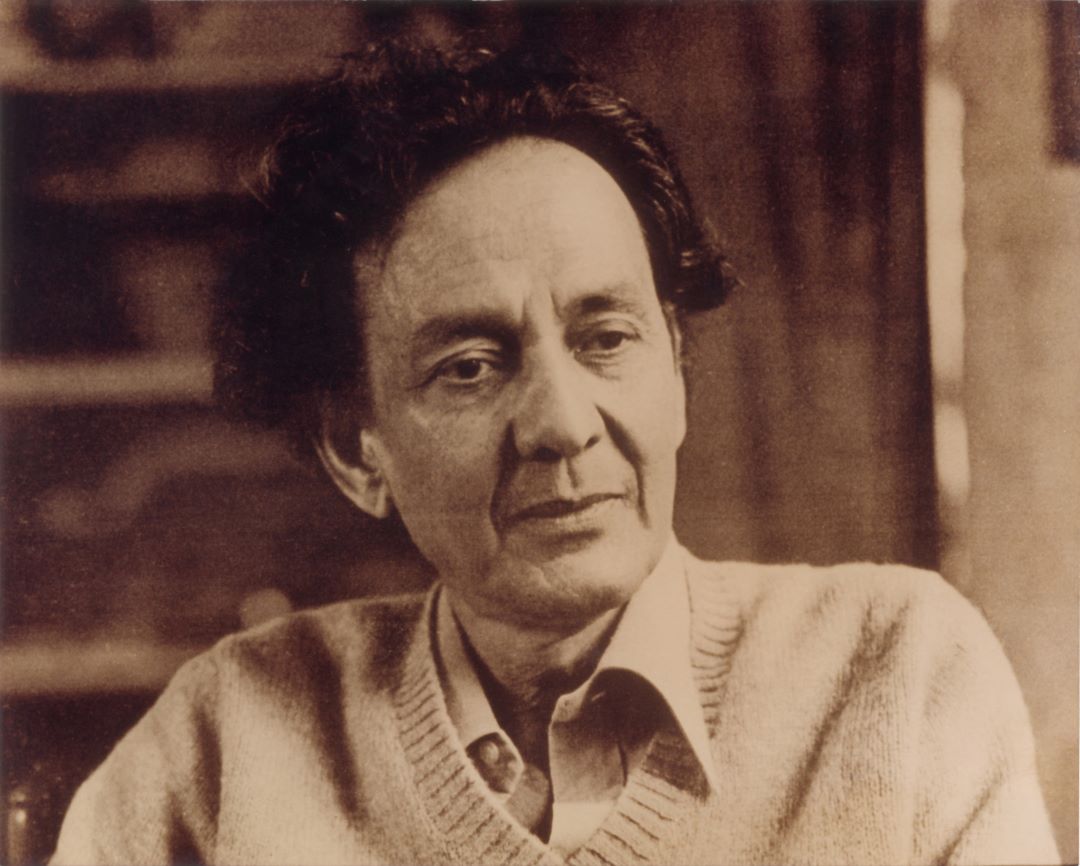

A portrait of S. H. Raza |

This essay is a part of 'Iconic Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art', DAG’s landmark publication that pairs the foremost art historians with artworks made by India's most significant artists, set to be featured in an annual exhibition.

Ashok Vajpeyi (b. 1941) is a Hindi poet, translator, editor, essayist and art critic, with over twenty publications in Hindi and English. He is a former chairman of India’s Lalit Kala Akademi and author and editor of several texts on S. H. Raza, including Raza: A Life in Art (2007), Passion: The Life and Work of Raza and Maitri: Letters Between Sayed Haider Raza & Ashok Vajpeyi(2016).