Gogi Saroj Pal: The Interpreter of Unsettling Questions

Gogi Saroj Pal: The Interpreter of Unsettling Questions

Gogi Saroj Pal: The Interpreter of Unsettling Questions

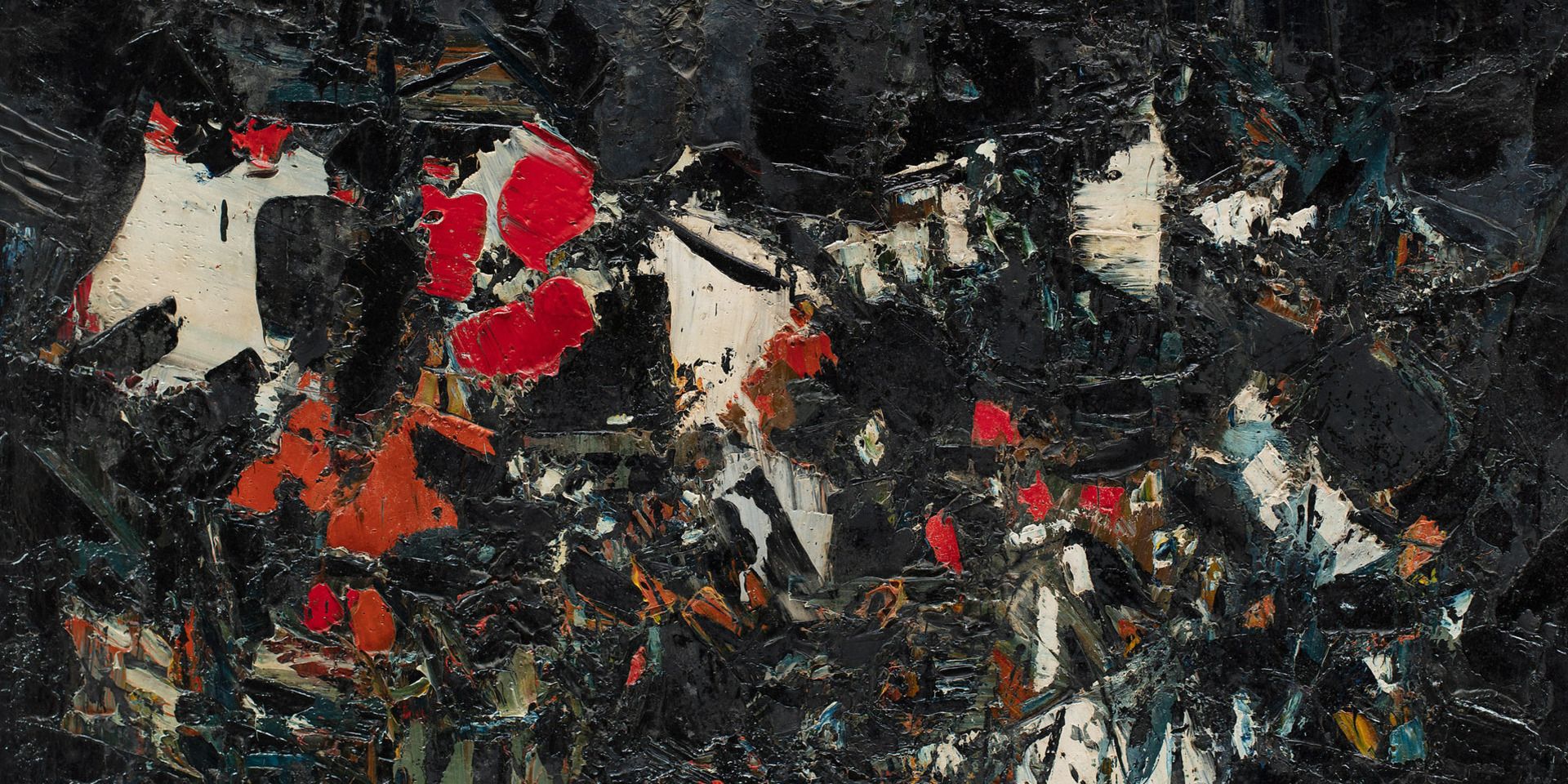

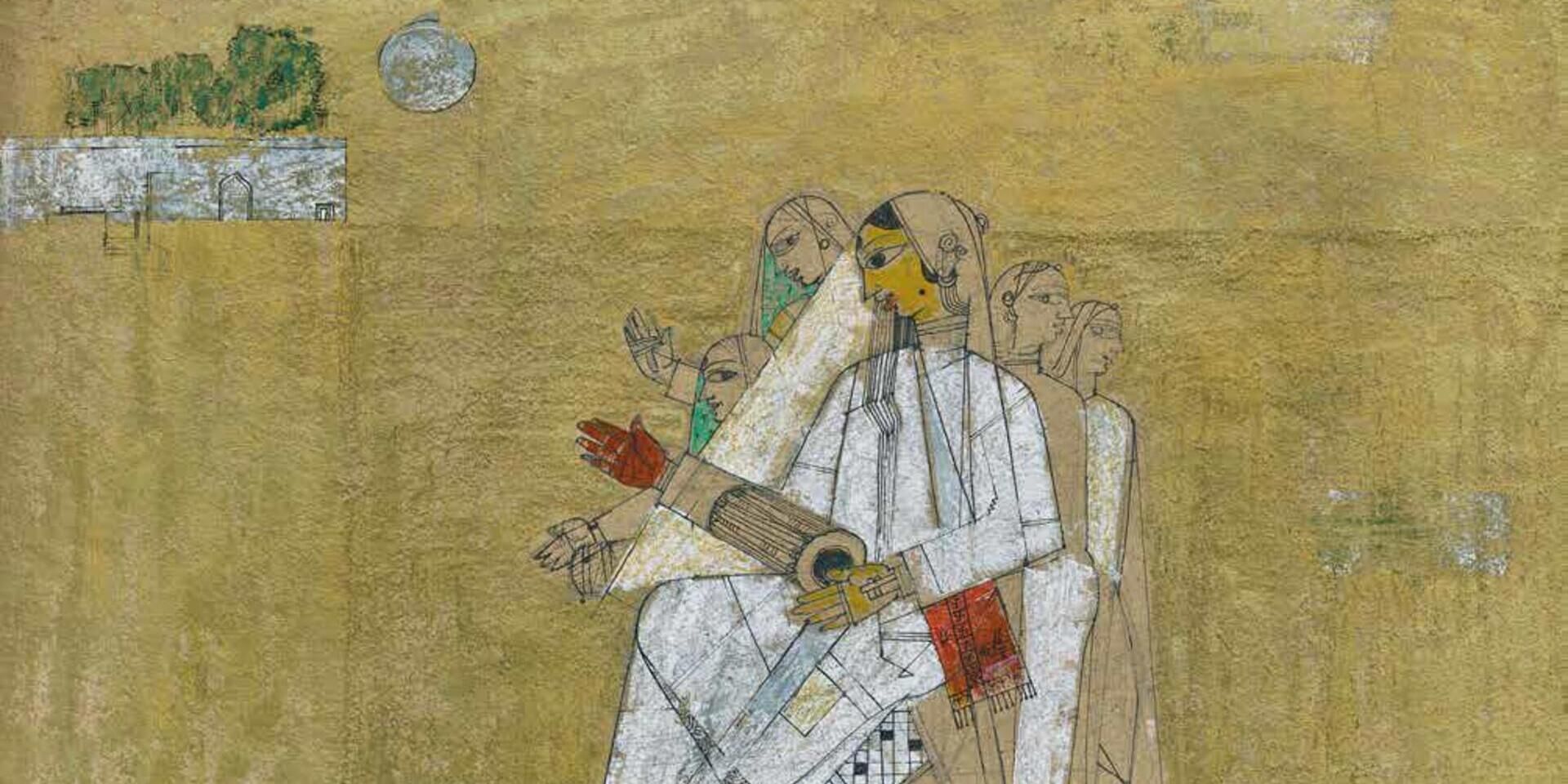

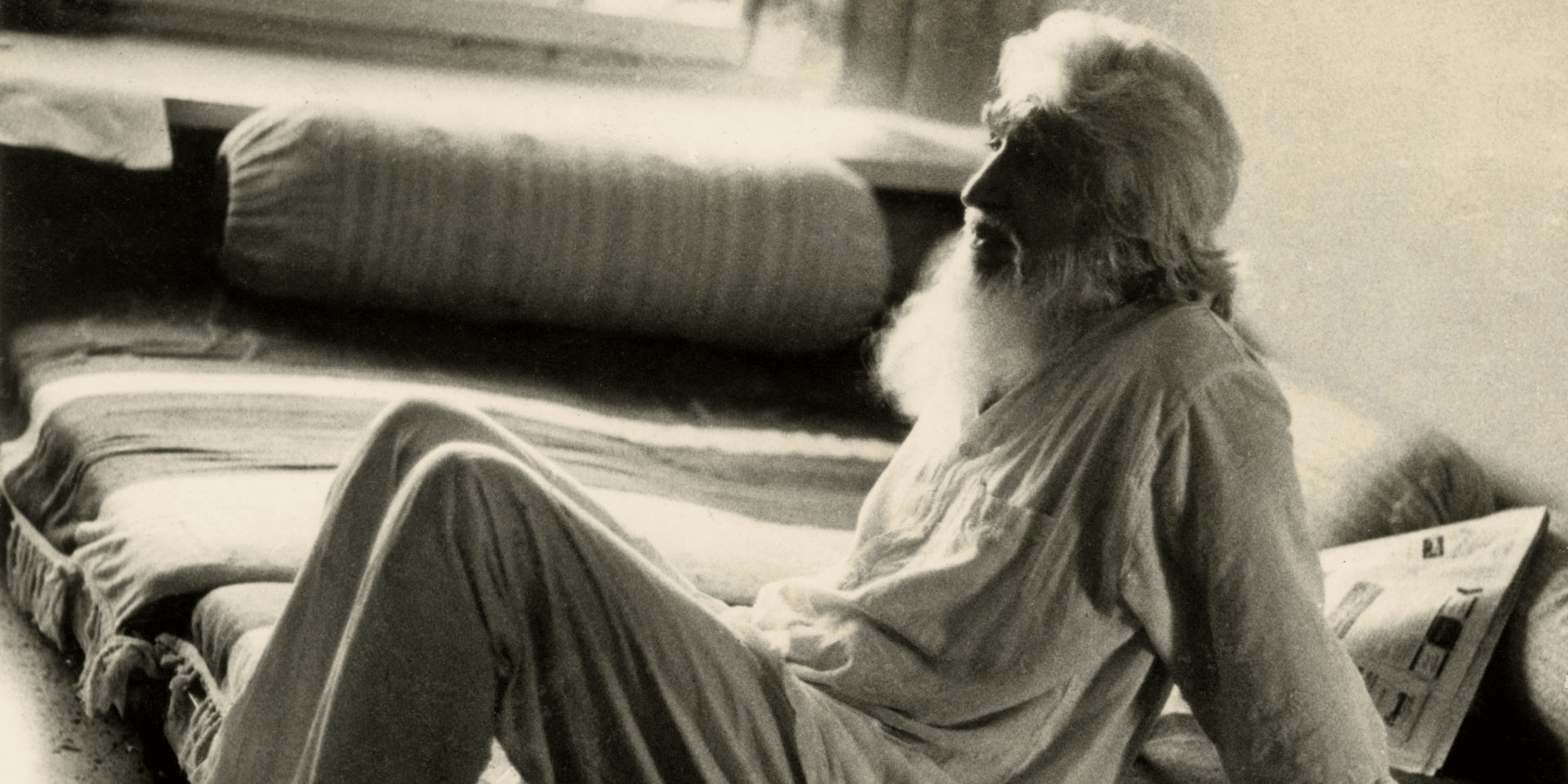

Gogi Saroj Pal, Untitled (detail), 1986, 38.7 x 50.0 in. Collection: DAG

Gogi was like the quintessential Cheshire cat, never entirely here, never quite there either, as chimerical as her quicksilver personality, oftener a voice on the phone than physically present.

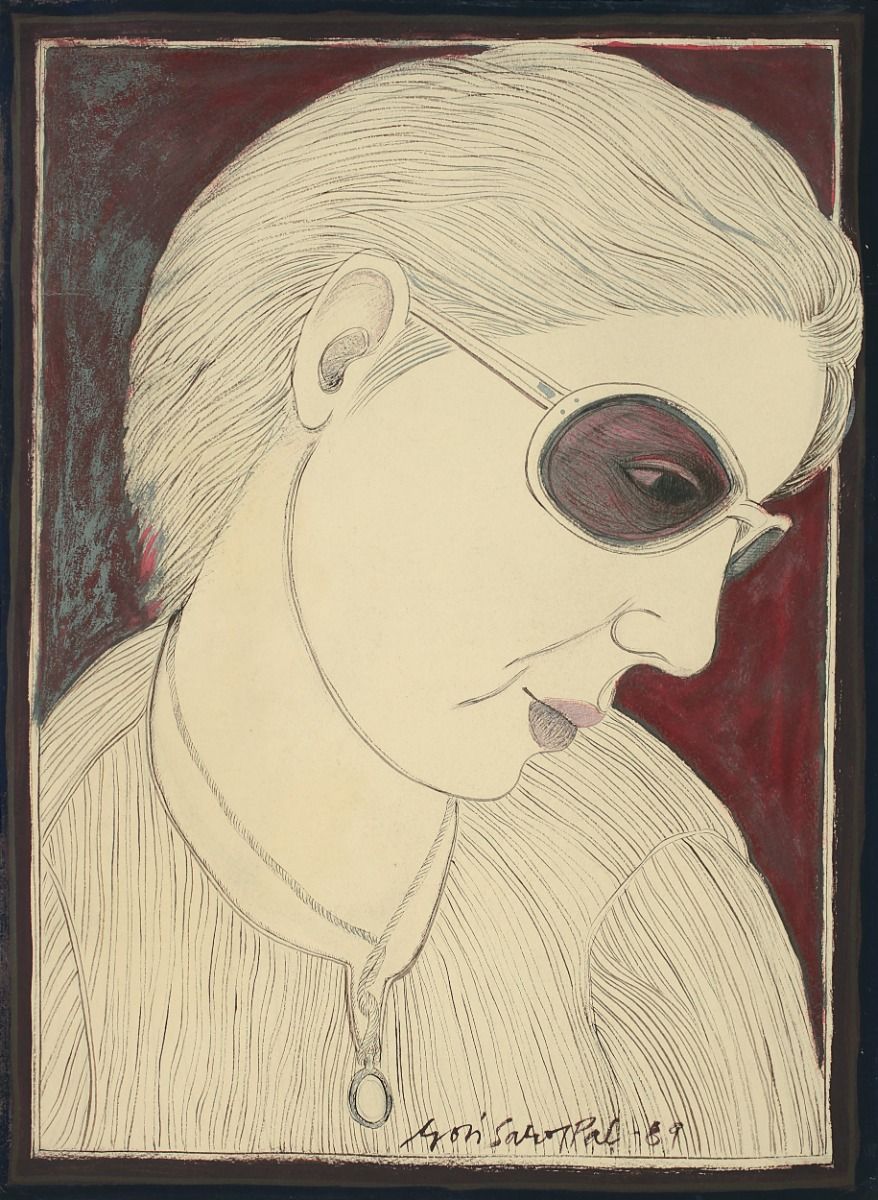

She wanted her art to be larger than her, but though diminutively small, she overpowered it through her scathing wit and her gleeful joy at causing offence with a tongue she trained to power with words intended to hurt. Yet, she was never irrational, nor spiteful or mean; she merely spoke her mind, hoping the reaction would be as volcanic as it usually was. Everyone who met her had a favourite Gogi story or two or three; anyone who visited her came out gasping for breath from her cigarette-smoke filled studio; eventually, everyone was seduced by her disarming charm.

|

Gogi Saroj Pal, Self-Portrait, 1989, Gouache on paper, 13.0 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG |

You would have expected her art to be full of fire and brimstone—and certainly when she passed away on 27 January this year, she left a yawning hole in the world of feminist Indian art—yet, her work was questioning rather than excoriating. Her paintings were not provocative, they simply told the truth as she saw it, which was without rancor. She did not promise social change, but she did question every status quo. If she was a feminist, she was a humanitarian first.

|

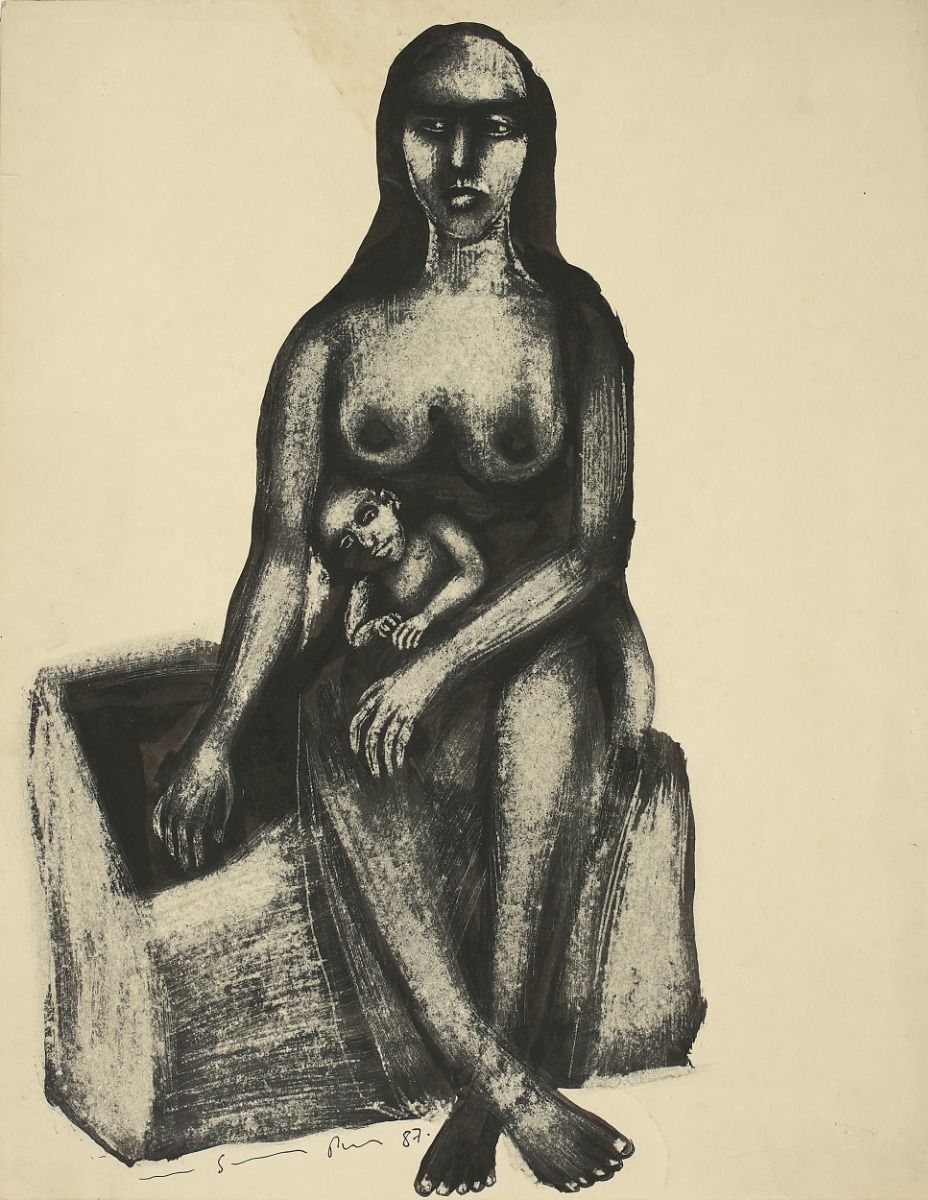

Gogi Saroj Pal, Mother and Child, 1987, Ink on paper, 23.0 x 18.0 in. Collection: DAG |

A student of Banasthali Vidyapeeth in Rajasthan and the College of Art, Delhi, Gogi’s earliest paintings looked at relationships through the prism of human selfishness. There were no mythological or historical references, though she could—and did—tell you stories from these sources over glasses of dark, sweetened tea that she persuaded you to share with her. Instead, she opted for a poignant note, her characters almost disappearing into the sepulchral tones of her canvas through the neglect of others—exactly the cancel culture she hoped viewers would notice in her work.

|

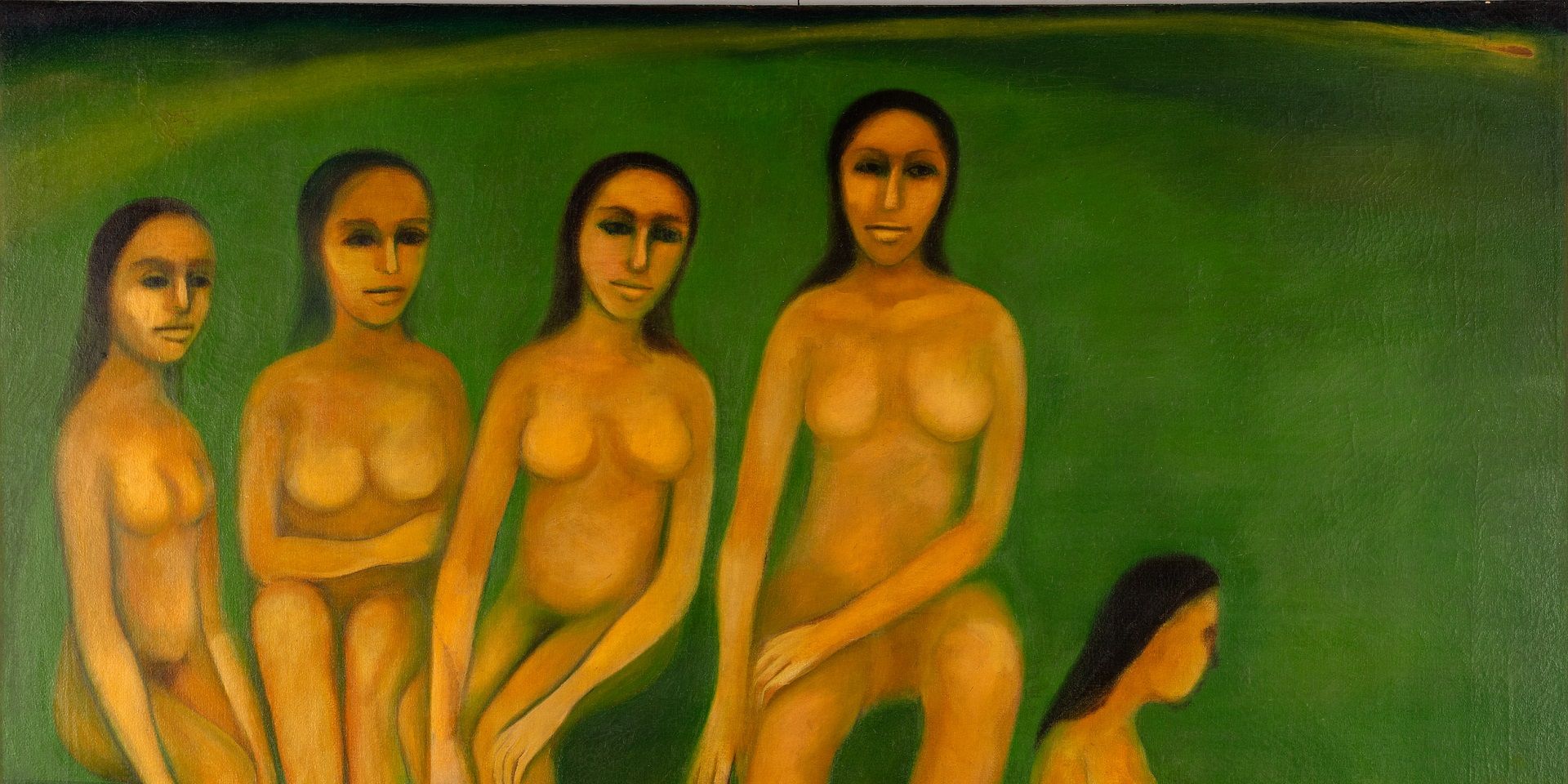

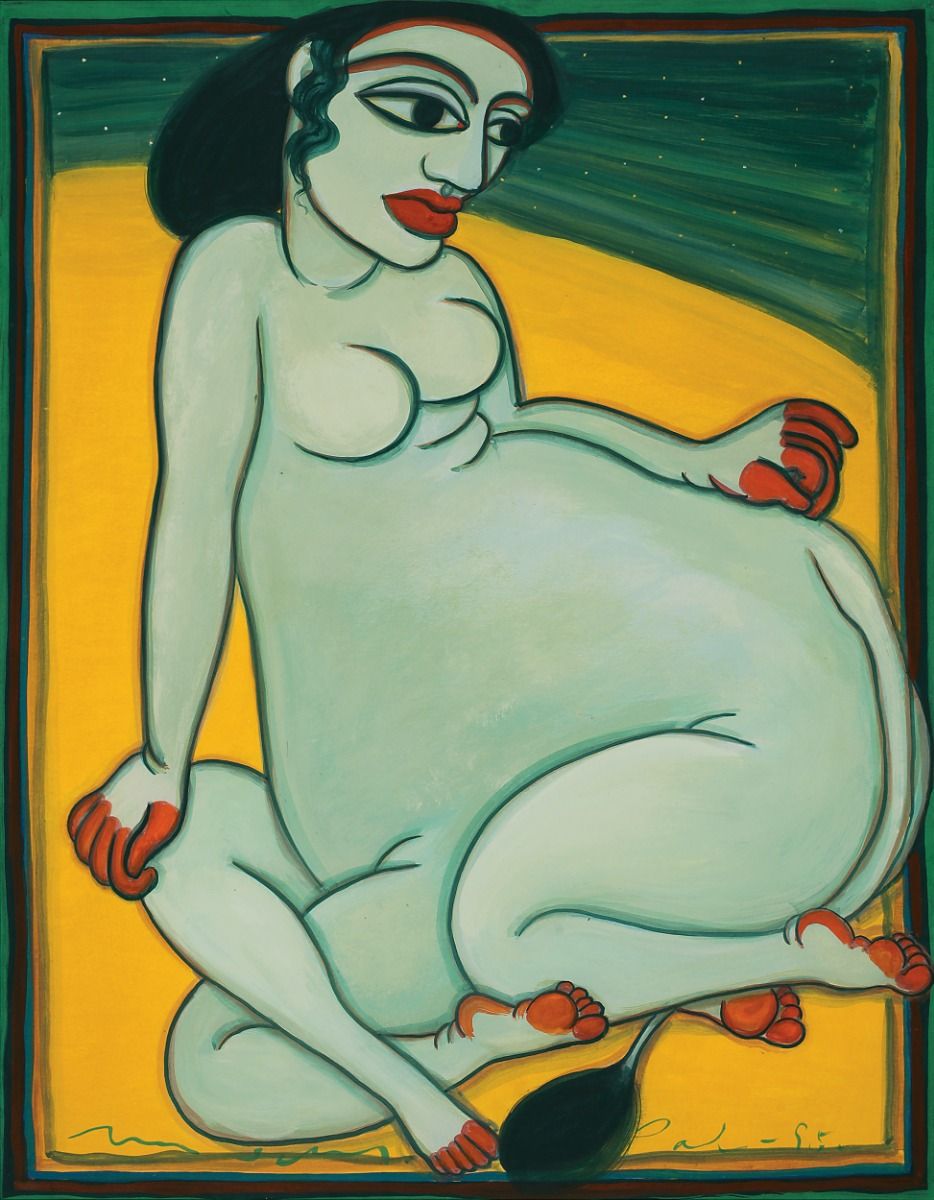

Gogi Saroj Pal, Untitled, Late 1990s, Watercolour and gouache on paper, 37.2 x 29.0 in. Collection: DAG |

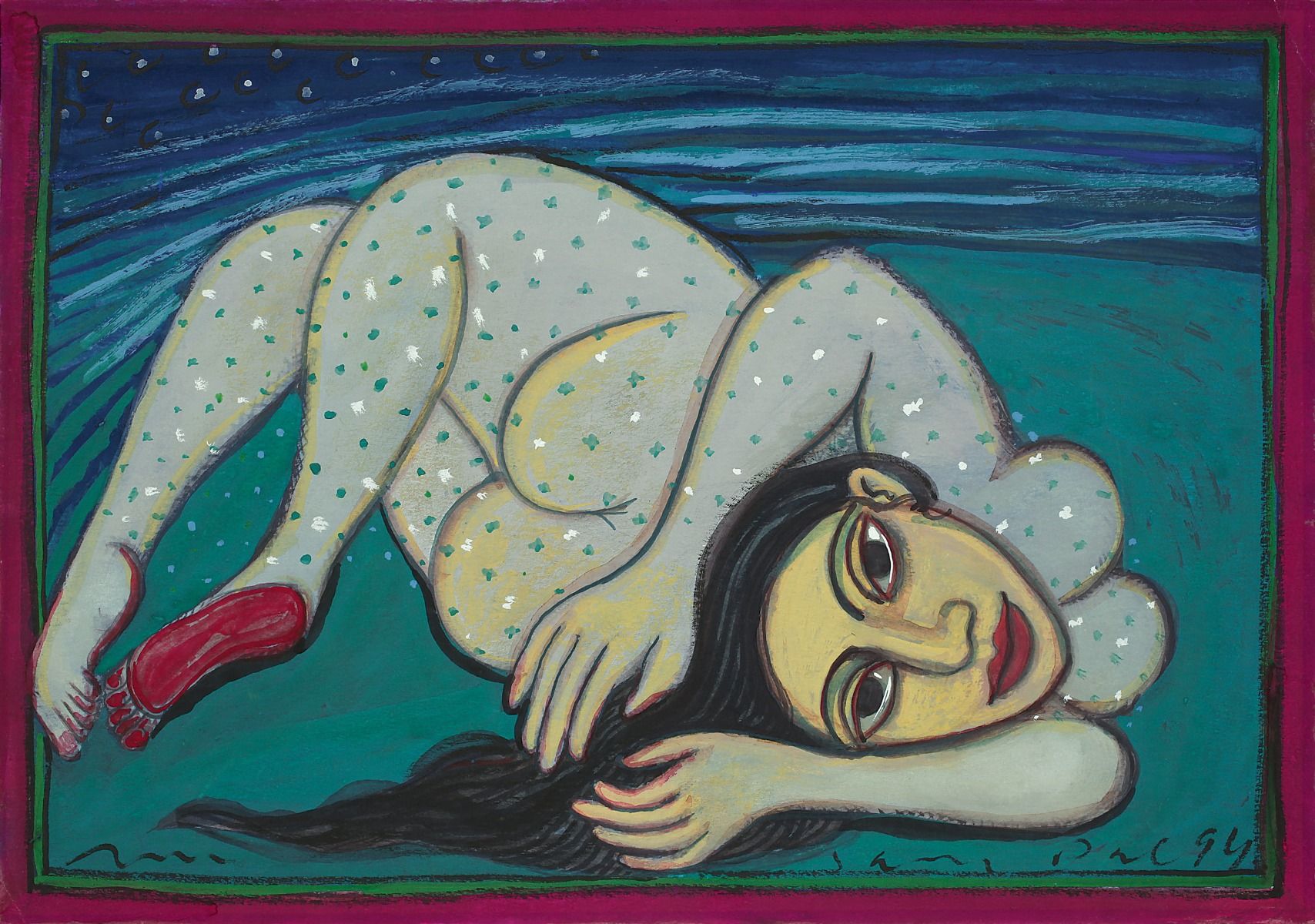

But her natural ebullience surfaced soon after as Gogi’s paintings became vibrant with colour. Borrowing from tradition, she painted her popular Nayika series of beloveds entirely for her—and their own—self-satisfaction. Her Nayikas waited on no one and for no one. Completely self-absorbed, they were their own gaze, thus robbing the male viewer of any authority or agency over them. Preening at their toilette, lipsticked and nail-polished, they afforded their own pleasure, a clarion call for rebellion that burnt no bras and shouted no slogans, a quiet revolution that nevertheless challenged patriarchal foundations without appearing threatening. This was Gogi’s greatest triumph as a modernist.

|

Gogi Saroj Pal, Kamdhenu, Gouache on paper, 1995, 22.7 x 17.7 in. Collection: DAG |

She went on to create other versions of women and her own self, as the mythical, hybrid creatures the Kamdhenu (or wish-fulfilling cow), the Kinnari (bird-woman), and the Dancing Horse. In her Homecoming series, she was the kinnari returning home, only to find it closed to her, so she could look in but not be let in. In these gentle ways she drove home the loneliness and alienation of women from discourse as well as history. Her women protagonists walked through streams of fire and forded streams with raging currents to attest their purity in a society ruled by men, so she absented those men from her paintings. If she placed sex workers within her compositions as question marks for society, she did not shy away from representing the Roop Kanwar sati that shook India in 1987 or the Nirbhaya rape case that brought about sweeping reforms in 2012. She even made the humble onion the subject of her paintings when a rise in the prices of the staple in middle class homes and their budgets led to unhappiness and despair.

|

Gogi Saroj Pal, Nayika, 1994, Gouache on paper, 10.0 x 14.2 in. Collection: DAG |

At first glance, Gogi’s work is merely an aesthetic diversion in the warp and weft of Indian modern art, but what appears at first glance innocent is riven with the many anomalies she noticed around herself and thought to share with her viewers and collectors. Their pleasing colours beguile, but ultimately Gogi’s paintings (and few sculptures) never stop asking us whether we understand what women have to put up with so that the world as we know it goes on. In her ultimately unsettling paintings, Gogi held up a mirror to every one of us. She may have gone, but that mirror is still here in front of us.

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Intersections

The Painters’ Camera: Husain and Mehta's Moving Images

Avijit Mukul Kishore

February 01, 2023